Abstract

AIM: To assess linear endoscopic ultrasound (L-EUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in biliary tract dilation and suspect small ampullary tumor.

METHODS: L-EUS and MRI data were compared in 24 patients with small ampullary tumors; all with subsequent histological confirmation. Data were collected prospectively and the accuracy of detection, histological characterization and N staging were assessed retrospectively using the results of surgical or endoscopic treatment as a benchmark.

RESULTS: A suspicion of ampullary tumor was present in 75% of MRI and all L-EUS examinations, with 80% agreement between EUS and histological findings at endoscopy. However, L-EUS and histological TN staging at surgery showed moderate agreement (κ = 0.54).

CONCLUSION: L-EUS could be a useful adjunct as a diagnostic tool in the evaluation of patients with suspected ampullary tumors.

Keywords: Ampullary tumors, Endoscopic ultrasound, Magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Ampullary tumors are infrequent entities that represent about 0.2% of gastrointestinal malignancies[1]. However, these neoplasms are considered as diagnostic challenges, because they display a wide array of pathological features, from mild dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma[2]. Clinical presentation includes vague abdominal pain, liver enzyme elevation, jaundice, recurrent pancreatitis, or uncommon symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding or duodenal obstruction[3,4].

Although endoscopic papillectomy represents a possible treatment[5], most ampullary tumors still undergo a surgical approach[6,7]. Thus, the diagnostic evaluation must be as careful as possible[8], because ampullary carcinoma is difficult to diagnose at an early stage and multiple imaging techniques should be carried out appropriately to establish a diagnosis and improve prognosis[9]. In fact, neither definitive methods for early diagnosis nor specific markers are available for this disease[10].

In recent years, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been shown to be superior to computed tomography (CT)[11] and conventional ultrasound scans[12], and equivalent to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for tumor detection and T and N staging of ampullary tumors[13].

Echoendoscopes are classified into radial and linear instruments[14]: to date, almost all information available on detection and staging of ampullary tumors has been obtained with radial echoendoscopes, and there are no studies with linear EUS (L-EUS) for this purpose.

The aim of the present study was to compare L-EUS and MRI in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected ampullary neoplasms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a consecutive series of 1205 L-EUS biliopancreatic examinations carried out in the period July 2007 to August 2009, there were 44 symptomatic patients (referred for increasing liver enzymes, jaundice, abdominal pain or dilation of the biliary tract) who were evaluated for suspicion of ampullary tumors. In 20 of these, the ampullary tumor was excluded by L-EUS that revealed other causes for their symptoms (four stones, four medio-choledocal stenoses, and 12 pancreatic cephalic small cancer). In the remaining 24 patients, data were collected prospectively and the accuracy of detection, histological characterization, and N staging were assessed retrospectively using the surgical or endoscopic results as a benchmark.

The following inclusion criteria were adopted: (1) cholestatic syndrome with previous negative or uncertain conventional US and CT imaging; (2) absence of previously known biliary and/or pancreatic diseases; (3) absence of advanced ampullary tumors; (4) histological diagnosis of the resected specimen; (5) MRI (axial, coronal and radial sequences, T2 single-shot, performed by a radiologist with experience of the biliary tree); and (6) L-EUS. Exclusion criteria included previously known biliary or pancreatic disease, and the presence of evident, large ampullary tumors at endoscopy.

L-EUS was carried out by means of a linear array echoendoscope (Pentax EG 33830UT or Pentax EG 3870UTK; Hamburg, Germany) that was inserted into the second part of the duodenum after intravenous midazolam and meperidine titrated to obtain conscious sedation. Keeping the tip of the echoendoscope in touch with the duodenal mucosa, the echoendoscope was torqued counterclockwise and slowly withdrawn into the duodenal bulb[14], and after visualization of the papilla of Vater, its endoscopic aspect was considered and recorded.

Ampullary carcinoma visualized by EUS was staged according to the TN classification[15]: T1 if the tumor echo was limited to the main duodenal papilla; T2 if the tumor echo invaded the duodenal muscularis propria layer; T3 if the tumor echo invaded the pancreas; and T4 if the tumor echo invaded peripancreatic soft tissues or other adjacent organs or vascular structures. EUS criteria for lymph node metastasis, classified as N1, were circularity, at least 10 mm in size, and hypoechogenicity.

Ethical considerations

This was a retrospective study and no study-driven clinical intervention was performed. Simplified Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective studies was obtained.

Statistical analysis

Differences in percentage of detection of ampullary tumors between MRI and L-EUS and between L-EUS and histology were assessed by the χ2 test. Values of P < 0.05 were chosen for rejection of the null hypothesis. Moreover, a κ value for agreement between endoscopic and surgical histology and L-EUS and histological TN staging was calculated. The value was scored according to standard criteria[16].

RESULTS

Data from 24 patients (17 men and seven women, aged 60 ± 12 years, range: 42-88 years) fulfilled the entry criteria and were evaluated. Demographic data, referral reasons, clinical, radiological and histological features are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Abdominal pain was the common symptom in all patients; jaundice was present in 13 (54%) and liver enzyme elevation was detected in 12 (50%). One patient was evaluated due to dilation of both extrahepatic and main pancreatic ducts. Multiple endoscopic forceps biopsies were taken from all cases during L-EUS evaluation. In one case, it was impossible to analyze the sample due to material not being available in the test-tube. Agreement between endoscopic and histological results was very good (κ = 0.81).

Table 1.

Demographic data and reasons for referral of patients with ampullary tumors

| Patient No. | Sex/age (yr) | Referral reason |

| 1 | M/53 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 2 | F/47 | Abdominal pain |

| 3 | M/71 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 4 | M/62 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 5 | F/53 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 6 | F/67 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 7 | M/45 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 8 | M/73 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 9 | M/80 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 10 | F/44 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 11 | F/50 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 12 | M/48 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 13 | M/66 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 14 | M/67 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 15 | M/59 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 16 | M/67 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 17 | F/60 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 18 | M/63 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 19 | F/54 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 20 | M/65 | Liver enzymes elevation |

| 21 | M/64 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 22 | M/42 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 23 | M/47 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

| 24 | F/88 | Liver enzymes elevation + jaundice |

Table 2.

Clinical-radiological variables and histological features of ampullary tumors

| Patients | US | CT-scan | MRI | L-EUS | Endoscopic imaging + biopsies | Surgery | Definitive staging and histology |

| 1 | Not done | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 1.6 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 2 | Uncertain | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N1, ADK |

| 3 | Not done | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 1.8 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 4 | Not done | Not done | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm -HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 5 | Not done | Not done | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 1.5 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 6 | Neg | Neg | Neg | T1N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-LGD | EMR | PT1N0, LGD |

| 7 | Not done | Neg | Neg | T1N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-LGD | EMR | PT1N0, LGD |

| 8 | Neg | Not done | Neg | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm -HGD | SA | PT1N0, HGD |

| 9 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 10 | Neg | Neg | Neg | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 11 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 12 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.6 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N1, ADK |

| 13 | Not done | Neg | Neg | T1N0 | Visible lesion 1.5 cm-LGD | SA | PT1N0, LGD |

| 14 | Neg | Not done | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.5 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 15 | Neg | Not done | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 16 | Neg | Uncertain | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 17 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 18 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 1.5 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N1, ADK |

| 19 | Not done | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N1, ADK |

| 20 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T1N0 | Visible lesion 1.5 cm-HGD | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 21 | Not done | Neg | Neg | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N0, ADK |

| 22 | Not done | Not done | Suspicion:dilation CBD | T2N0 | Visible lesion 2.5 cm-not available | DCP | PT1N0, HGD |

| 23 | Uncertain | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.5 cm-ADK | DCP | PT2N1, ADK |

| 24 | Neg | Neg | Suspicion:dilation CBD + WD | T2N1 | Visible lesion 2.0 cm-ADK | SA due to age | PT2N0, ADK |

ADK: Adenocarcinoma; CBD: Common bile duct; DCP: Duodeno-cephalo-pancreasectomy; HGD: High grade dysplasia; LGD: Low grade dysplasia; Neg: Negative for ampullary tumor; SA: Surgical ampullectomy; WD: Wirsung duct; US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; L-EUS: Linear endoscopic ultrasound; EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection.

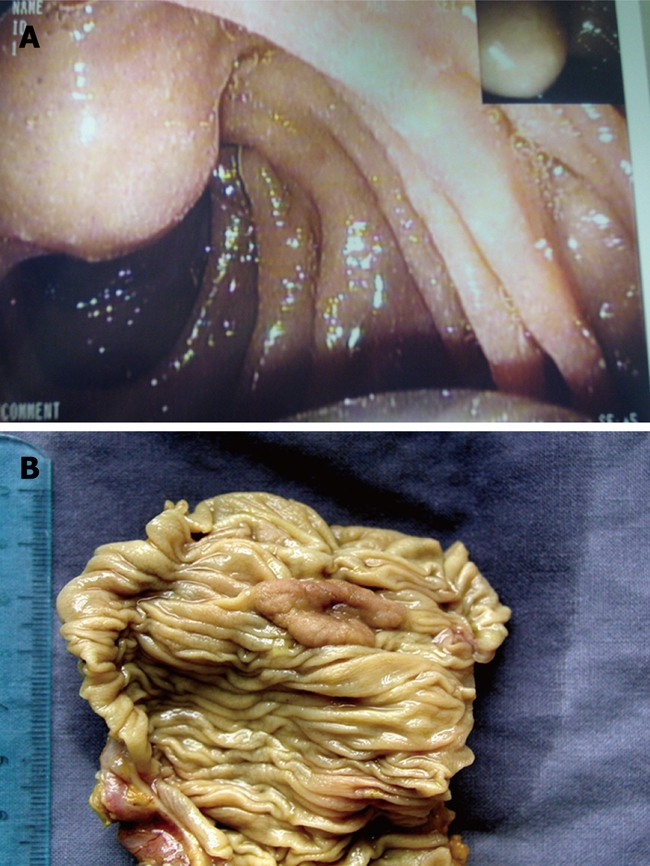

All patients underwent surgery except for two (stage T1N0) who were treated by endoscopic ampullectomy, and histological results were available for the entire group (Figure 1). Average diameter of the ampulla was 2 ± 0.8 cm (range: 1.5-2.6 cm).

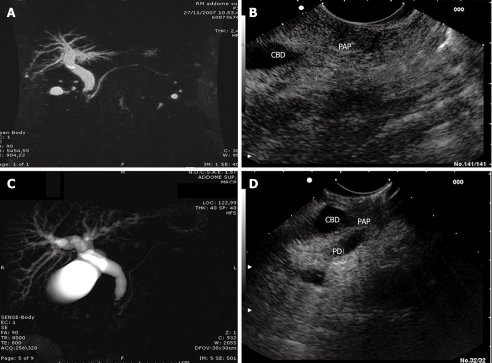

Figure 1.

Endoscopic aspect (A) and resected surgical specimen (B) of a small ampullary tumor.

MRI examination was negative in 6 (25%) cases, showed indirect signs (dilatation of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts) of space occupying lesions of the ampulla in 17 (71%) cases, and an actual space occupying lesion of the ampulla in 1 (8%) case (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ampullary tumor, stage 1. A: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed dilation of the common bile duct and Wirsung’s duct, without space-occupying lesions of the ampulla; B: Linear endoscopic ultrasound (L-EUS) of the same patient. Ampullary tumor, stage 2; C: MRI showed dilation of the common bile duct and normal appearance of Wirsung’s duct; D: L-EUS scan of the same patient, which showed duodenal wall disruption without pancreas invasion. CBD: Common bile duct; PAP: Papilla (Vater's papilla); PD: Pancreatic duct.

L-EUS detected ampullary tumors in all 24 (100%) patients (P < 0.03 vs MRI) (Figure 2).

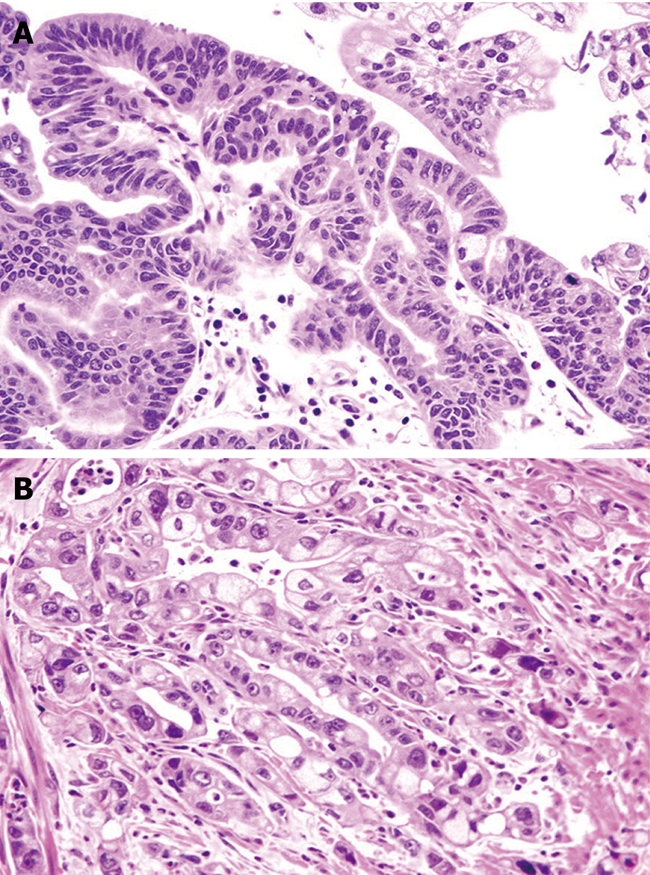

In 19 (80%) cases, Histological analysis revealed intestinal-type adenocarcinoma in 19 (80%) cases (stage T2N0 in 14 and T2N1 in five) CDX2 positive, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia in 2 (8%), and adenoma with low-grade dysplasia in the remaining 3 (12%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ampullary tumor, low-grade dysplasia (A) and ampullary adenocarcinoma (B). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE), original magnification 40 ×.

No biliary/pancreatic-type tumors were found. Thus, L-EUS was able to detect malignant lesions in 87% of ampullary lesions (P = 0.21 vs histological results), with sensitivity of 87.5% and specificity of 100% and a moderate agreement (κ = 0.54) between L-EUS and TN histological staging.

DISCUSSION

Although MRI is regarded as the most reliable noninvasive diagnostic imaging modality for the evaluation of pancreatobiliary lesions[17,18], and is considered as a substitute for diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[19], it cannot provide biopsy samples and rarely identifies whether the obstruction is benign or malignant, especially when lesions are small. The ampulla of Vater is a possible blind spot for MRI because of its small size and the tapering of the intramural ducts that contain little fluid[9,18,20]. Thus, other investigative modalities have been added to the diagnostic armamentarium; among these, EUS has proved to be useful and reliable. Generally, radial EUS is considered the gold standard[17,18] whereas L-EUS performance has never been studied.

This is believed to be the first study to report L-EUS as a useful diagnostic tool for detection and staging of small ampullary tumors. In our experience, also supported by histological findings, this technique was able to raise a suspicion of ampullary neoplasm when other imaging techniques, including MRI, were not. Indeed, a suspicion of ampullary neoplasms was observed in 75% of MRI investigations compared with 100% of L-EUS scanning; the latter proved to be accurate, identifying > 80% of these lesions as malignant. The accuracy of EUS in the TNM staging of ampullary tumors remains controversial[17,21]. Histological grade is the gold standard, with the possibility to differentiate between ampullary tumor of intestinal type and those originating from the biliary or pancreatic ducts; however, it is worthy of note that a discrete correlation was found between L-EUS and histological TN staging in the present study. The discrepancies were due more to overstaging in 6 (25%) patients than to understaging in 3 (12%) patients. Overstaging can occur in the presence of peritumoral inflammation, whereas understaging can occur in the presence of minimal malignant infiltration of the pancreas[9,22]. Other recent experience also suggests that EUS is an accurate diagnostic test and exhibits a high level of agreement with surgical pathology[23].

However, L-EUS provided several advantages compared to MRI, such as the possibility of obtaining direct endoscopic visualization of the major duodenal papilla, and to depict the layered structures of the periampullary area. Thus, it is often possible to give a judgment on a possible endoscopic approach, because it also demonstrates intracholedochal growth. Limitations of this technique include inability to differentiate early malignant from benign tumors and to demonstrate distant metastases, in addition to being an invasive method.

The present study had some limitations. It was retrospective, the patient cohort was relatively small, and it was carried out in a setting with particular expertise in EUS. It remains to be established whether these results can be translated to a more general setting.

In conclusion, L-EUS appears to be a valid diagnostic tool to identify and stage small ampullary tumors, and might yield results that are superior to those of other diagnostic techniques. Further prospective studies are clearly needed to confirm these observations.

COMMENTS

Background

Ampullary tumors are rare and difficult to diagnose. The correct diagnosis is often reached after serological, radiological and/or endoscopic tests. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been demonstrated as being as useful as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for detection of these neoplasms.

Innovations and breakthroughs

No previous study has been previously conducted with L-EUS in this setting, and this study by Manta et al showed that this appears to be a valid diagnostic tool to identify and stage small ampullary tumors, and might yield results that are superior to those with other diagnostic techniques.

Terminology

EUS and L-EUS: techniques that combine endoscopic and echographic approaches for detecting lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. MRI: a technique that employs nuclear resonance imaging to visualize abdominal sections without exposing the subject to radiation.

Peer review

This is a retrospective study with a small sample size. Despite this, it is a novel and well-designed study that is likely to influence clinical practice.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Rupert Leong, Associate Professor, Director of Endoscopy, Concord Hospital, ACE Unit, Level 1 West, Hospital Rd, Concord NSW 2139, Australia

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Kim RD, Kundhal PS, McGilvray ID, Cattral MS, Taylor B, Langer B, Grant DR, Zogopoulos G, Shah SA, Greig PD, et al. Predictors of failure after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tran TC, Vitale GC. Ampullary tumors: endoscopic versus operative management. Surg Innov. 2004;11:255–263. doi: 10.1177/155335060401100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross WA, Bismar MM. Evaluation and management of periampullary tumors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:362–370. doi: 10.1007/s11894-004-0051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida H, Shibata K, Iwaki K, Kai S, Ohta M, Kitano S. Ampullary cancer and preoperative jaundice: possible indication of the minimal surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1194–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon SM, Kim MH, Kim MJ, Jang SJ, Lee TY, Kwon S, Oh HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Focal early stage cancer in ampullary adenoma: surgery or endoscopic papillectomy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown KM, Tompkins AJ, Yong S, Aranha GV, Shoup M. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is curative in the majority of patients with node-negative ampullary cancer. Arch Surg. 2005;140:529–532; discussion 532-533. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JH, Kim JH, Han JH, Yoo BM, Kim MW, Kim WH. Is endoscopic papillectomy safe for ampullary adenomas with high-grade dysplasia? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2547–2554. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tien YW, Yeh CC, Wang SP, Hu RH, Lee PH. Is blind pancreaticoduodenectomy justified for patients with ampullary neoplasms? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1666–1673. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0943-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen WX, Xie QG, Zhang WF, Zhang X, Hu TT, Xu P, Gu ZY. Multiple imaging techniques in the diagnosis of ampullary carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:649–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukada K, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Miyakawa S, Nagino M, Kondo S, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T, Kimura F, et al. Diagnosis of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:31–40. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1278-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Obana T. Preoperative evaluation of ampullary neoplasm with EUS and transpapillary intraductal US: a prospective and histopathologically controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skordilis P, Mouzas IA, Dimoulios PD, Alexandrakis G, Moschandrea J, Kouroumalis E. Is endosonography an effective method for detection and local staging of the ampullary carcinoma? A prospective study. BMC Surg. 2002;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CH, Yang CC, Yeh YH, Chou DA, Nien CK. Reappraisal of endosonography of ampullary tumors: correlation with transabdominal sonography, CT, and MRI. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009;37:18–25. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seewald S, Ang TL, Soehendra N. Basic technique of handling the linear echoendoscope and how it differs from the radial echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S78–S80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors . Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. WHO classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon ME, Carpenter SL, Elta GH, Nostrant TT, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG, Stotland B, Rosato EF, Morris JB, Eckhauser F, et al. EUS compared with CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography and the influence of biliary stenting on staging accuracy of ampullary neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Materne R, Van Beers BE, Gigot JF, Jamart J, Geubel A, Pringot J, Deprez P. Extrahepatic biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance imaging compared with endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2000;32:3–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irie H, Honda H, Shinozaki K, Yoshimitsu K, Aibe H, Nishie A, Nakayama T, Masuda K. MR imaging of ampullary carcinomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:711–717. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geier A, Nguyen HN, Gartung C, Matern S. MRCP and ERCP to detect small ampullary carcinoma. Lancet. 2000;356:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)74455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tio TL, Sie LH, Kallimanis G, Luiken GJ, Kimmings AN, Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Staging of ampullary and pancreatic carcinoma: comparison between endosonography and surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:706–713. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubo H, Chijiiwa Y, Akahoshi K, Hamada S, Matsui N, Nawata H. Pre-operative staging of ampullary tumours by endoscopic ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:443–447. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.857.10505006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Artifon EL, Couto D Jr, Sakai P, da Silveira EB. Prospective evaluation of EUS versus CT scan for staging of ampullary cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]