Abstract

AIM: To explore the association between mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4) gene polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk.

METHODS: Five tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) in the SMAD4 gene were selected and genotyped in 322 gastric cancer cases and 351 cancer-free controls in a Chinese population by using the polymerase chain reactionrestriction fragment length polymorphism method. Immunohistochemistry was used to examine SMAD4 protein expression in 10 normal gastric tissues adjacent to tumors.

RESULTS: In the single-locus analysis, two significantly decreased risk polymorphisms for gastric cancer were observed: the SNP3 rs17663887 TC genotype (adjusted odds ratio = 0.38, 95% confidence interval: 0.21-0.71), compared with the wild-type TT genotype and the SNP5 rs12456284 GG genotype (0.31, 0.16-0.60), and with the wild-type AA genotype. In the combined analyses of these two tSNPs, the combined genotypes with 2-3 protective alleles (SNP3 C and SNP5 G allele) had a significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer (0.28, 0.16-0.49) than those with 0-1 protective allele. Furthermore, individuals with 0-1 protective allele had significantly decreased SMAD4 protein expression levels in the normal tissues adjacent to tumors than those with 2-3 protective alleles (P = 0.025).

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that genetic variants in the SMAD4 gene play a protective role in gastric cancer in a Chinese population.

Keywords: Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4, Genetic variation, Gastric tumor, Molecular epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide; about 934 000 new cases were diagnosed and approximately 700 000 people died of the disease in 2002[1]. The incidence of gastric cancer varies within countries. In China, it was predicted that, in 2005, 300 000 deaths and 400 000 new cases from gastric cancer, which ranks it as the third most common cancer[2]. Epidemiological studies have identified many risk factors for gastric cancer, such as Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, low fiber intake, and tobacco smoking[3,4]. However, only a fraction of individuals exposed to these factors develop gastric cancer during their lifetime, which suggests that genetic susceptibility plays an important role in gastric carcinogenesis.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling is one of the most important tumor suppressor pathways. Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD) proteins serve as crucial components of TGF-β signaling, which negatively regulates cell growth and promotes apoptosis of epithelial cells. According to the specific functions, Smads can be classified into the receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads: Smad 1, 2, 3, 5 and 8), inhibitory Smads (anti-Smads: Smad 6 and 7), and the common mediator Smads (Co-Smads: Smad 4), which is apparently common to all of the ligand-specific Smad pathways and plays a central role in TGF-β signaling[5]. In 1996, SMAD4 was identified as a candidate tumor suppressor gene[6].

The loss of SMAD4 expression is a common feature of most human malignancies, including gastric cancer[7-11]. In 1997, Powell et al[10] firstly reported inactivation of SMAD4 in gastric carcinoma. Then, Xiangming et al[12] further demonstrated that the reduced expression of SMAD4 was 75.1% in advanced gastric cancer. Wang et al[13] has found that the loss of SMAD4, especially loss of nuclear SMAD4 expression, is involved in gastric cancer progression. A more recent study by Leng et al[14] has shown that SMAD4 expression in gastric cancer tissue is dramatically lower than that in peri-tumoral tissue. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that mutations in SMAD4 play a significant role in SMAD4 inactivation. For example, mutation-related loss of SMAD4 is most prevalent in pancreatic and colorectal cancer[8,15]. SMAD4 mutations have also been observed in seminoma[16] and head and neck cancer[17], which give rise to the complete loss of SMAD4. Notably, germline mutations in SMAD4 are found in > 50% of patients with familial juvenile polyposis syndrome[18,19], which predisposes individuals to develop gastrointestinal cancer. Although mutations in SMAD4 are not seen frequently in gastric cancer (2.9%)[10], the gene is highly polymorphic in the dbSNP database.

Given the role of SMAD4 in tumor suppression, we hypothesized that genetic variants in the SMAD4 gene are associated with the risk of gastric cancer. In the present study, five tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tSNPs) were selected to evaluate the association between these common genetic variants in SMAD4 gene and risk of gastric cancer in our ongoing, hospital-based, case-control study in a Chinese population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

The study included 322 gastric cancer patients and 351 cancer-free controls. All subjects were recruited from an ongoing study that started in March 2006. The detailed inclusion criteria have been described previously[20]. The participation rate of cases was about 95%. The cancer-free controls were genetically unrelated to the cases, had no individual history of cancer, and were recruited from the hospital where they were seeking health care or undergoing routine health examination. All the 351 control subjects were matched with the cases by age (± 5 years) and sex. Informed consent was obtained from each of the eligible subjects before recruitment. A questionnaire was used to obtain demographic and risk factor information about the study subjects. For gastric cancer patients, the clinicopathological variables, including tumor site, tumor histotype, invasion, and lymph node status, were obtained from the medical records of patients. The classification criteria of the clinicopathological variables were previously reported[20]. The response rate of the eligible controls was about 85%. Those subjects who smoked daily for > 1 year were defined as regular smokers. Individuals who consumed one or more alcoholic drinks per week for at least 1 year were considered regular drinkers. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Nanjing Medical University.

SNP selection and genotyping

The SMAD4 gene, which is 49.5-kb long and is located on chromosome 18q21.1, contains 13 exons and 12 introns. There have been at least 197 SNPs reported in the dbSNP database. Based on the HapMap database (http://www.hapmap.org/) (from chr1846807425 to 46868845), tSNPs were selected from common variants (minor allele frequency > 0.10) in the Han Chinese in Beijing (CHB) population sample. As a result, six tSNPs were selected using a pairwise Tagger method[21] with an r2 cutoff value of 0.8 to capture all the common SNPs in SMAD4 and the mean r2 was 0.980. The genotype frequencies of the SNPs can be influenced by population differences and sample sizes[22,23], therefore, we genotyped these six tSNPs in 100 Chinese control subjects. Of these, one was not in agreement with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) (P < 0.01). Thus, this tSNP was not included in further analyses. The rs number and relative position of selected five tSNPs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Information on five genotyped tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms in the SMAD4 gene

| SNP No. | SNP ID | Location |

MAF |

P2 | P for HWE3 | Genotyping rate (%) | ||

| Database1 | Cases | Controls | ||||||

| 1 | rs12958604 | Intron 2 | 0.446 | 0.452 | 0.450 | 0.956 | 0.893 | 99.1 |

| 2 | rs10502913 | Intron 2 | 0.363 | 0.280 | 0.305 | 0.308 | 0.117 | 99.4 |

| 3 | rs17663887 | Intron 9 | 0.056 | 0.023 | 0.057 | < 0.001 | 0.258 | 100.0 |

| 4 | rs9304407 | Intron 11 | 0.411 | 0.458 | 0.423 | 0.206 | 0.291 | 100.0 |

| 5 | rs12456284 | 3’-UTR | 0.405 | 0.289 | 0.350 | 0.017 | 0.231 | 100.0 |

Minor allele frequency (MAF) for Han Chinese in Beijing (CHB) population in the HapMap database (http://www.hapmap.org);

P value for the allele distribution difference between the cases and controls;

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P value in the control group. SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; 3’-UTR: 3’-untranslated region.

The selected tSNPs were genotyped in all 673 subjects by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-restriction fragment length polymorphism method. The tSNPs information, primers, and restriction enzymes are all listed in Supplementary Table 1. The genotype analysis was done by two persons independently in a blind fashion. About 1% of PCR products were randomly selected and confirmed by sequencing (data not shown), and > 10% of the samples were randomly selected for repeated genotyping. The results were 100% concordant.

Immunohistochemical staining and evaluation

Immunohistochemical study was performed on the 10 normal gastric tissues adjacent to tumors. Immunohistochemical staining was performed by using the Boster SABC (rabbit IgG)-POD Kit (Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After deparaffinization and rehydration, the sections were microwaved for 10 min for antigen retrieval and then washed in PBS. Sections were incubated with normal goat serum for 30 min to block nonspecific antibody binding. The primary antibody anti-Smad4 (1:100; ab40759; Abcam Ltd., Hong Kong, China) was used to incubate sections overnight at 4°C, followed by three successive rinses with PBS, and incubation with secondary antibody for an additional 20 min. After rinsing, tissue sections were incubated with streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase (SABC) (Boster) for 20 min at room temperature. Slides were washed and visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with balsam for examination.

A positive reaction was indicated by a reddish brown precipitate in the cytoplasm. Specifically, the percentage of positive cells was divided into five grades (percentage cores): (0) ≤ 5%; (1) 6%-25%; (2) 26%-50%; (3) 51%-75%; and (4) > 75%. Intensity of staining was divided into four grades (intensity scores): (0) no staining; (1) light brown; (2) brown; and (3) dark brown. SMAD4 staining positivity was determined by the formula: overall scores = percentage score × intensity score. Overall score of ≤ 3 was defined as negative, > 3 but ≤ 6 as weakly positive, and > 6 as strongly positive[24].

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used to compare the differences in frequency distributions of selected demographic variables, smoking status, alcohol use, as well as each allele and genotype of the SMAD4 polymorphisms between the cases and controls. The difference between SMAD4 genotypes and clinicopathological characteristics was assessed by χ2 test. The crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained to assess the association between the SMAD4 polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk using, unconditional univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. The multivariate adjustment included the age, sex, tobacco smoking, and alcohol use. HWE of the genotype distribution among control groups was tested by a goodness-of-fit χ2 test. The combined genotypes data were further stratified by subgroups of the age, sex, smoking status, and alcohol use. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the SMAD4 expression levels between individuals with 0-1 protective allele and 2-3 protective alleles. All tests were performed with SAS software (version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) with two sides, unless indicated otherwise. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the distribution of age (P = 0.354), sex (P = 0.516), or alcohol use (P = 0.846) between the case and control subjects. However, there were more regular smokers among the cases (43.8%) than among the controls (35.0%) (P = 0.020). Furthermore, there were 149 (48.1%) and 161 (51.9%) patients with cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer, respectively. The histological types were 162 (52.3%) intestinal and 148 (47.7%) diffuse type gastric cancer; positive lymph nodes were identified in 148 (47.1%) cases. For depth of tumor infiltration, 80 (25.8%), 68 (22.0%), 112 (36.1%) and 50 (16.1%) cases were T1, T2, T3 and T4, respectively.

Table 2.

Frequency distributions of selected variables between gastric cancer cases and cancer-free controls n (%)

| Variables | Cases (n = 322) | Controls (n = 351) | P1 |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 60 | 129 (40.1) | 153 (43.6) | 0.354 |

| ≥ 60 | 193 (59.9) | 198 (56.4) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 215 (66.8) | 226 (64.4) | 0.516 |

| Female | 107 (33.2) | 125 (35.6) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 181 (56.2) | 228 (65.0) | 0.020 |

| Regular | 141 (43.8) | 123 (35.0) | |

| Drinking status | |||

| Never | 217 (67.4) | 239 (68.1) | 0.846 |

| Regular | 105 (32.6) | 112 (31.9) | |

| Tumor site2 | |||

| Cardia | 149 (48.1) | ||

| Non-cardia | 161 (51.9) | ||

| Histological types2 | |||

| Intestinal | 162 (52.3) | ||

| Diffuse | 148 (47.7) | ||

| Depth of tumor infiltration2 | |||

| T1 | 80 (25.8) | ||

| T2 | 68 (22.0) | ||

| T3 | 112 (36.1) | ||

| T4 | 50 (16.1) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis2 | |||

| Negative | 166 (52.9) | ||

| Positive | 148 (47.1) | ||

Two-sided χ2 test for the frequency distribution of selected variables between gastric cancer cases and cancer-free controls;

No. of subjects in cases (n = 310 for tumor site, n = 310 for histological types, n = 310 for depth of tumor infiltration, and n = 314 for lymph node metastasis) were less than the total number (n = 322) because some information was not obtained.

The primary information of the five tSNPs in CHB patients is shown in Table 1. The observed genotype frequencies of the five tSNPs among the control subjects were all in agreement with HWE (all P > 0.05). The allele frequencies of the genotyped tSNPs in the controls were consistent with those of the International HapMap Project database for CHB. The single SNP allele analysis indicated that the allele frequencies of two tSNPs, SNP3 rs17663887 and SNP5 rs12456284, were significantly different between the cases and controls (P < 0.001 for SNP3 rs17663887, and P = 0.017 for SNP5 rs12456284).

The genotype frequencies of these five tSNPs and their associations with gastric cancer risk are summarized in Table 3. The single locus analysis revealed that the genotype frequencies of two tSNPs, SNP3 rs17663887 and SNP5 rs12456284, were significantly different between the cases and controls (P < 0.001 for SNP3 and P = 0.003 for SNP5, respectively). Multivariate logistic regression analyses indicated that the variant TC genotype of SNP3 was associated with a significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer compared with the wild-type TT genotype (adjusted OR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.21-0.71). For the SNP5, compared with the wild-type AA genotype, the variant GG genotype was associated with a statistically significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer (adjusted OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.16-0.60) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genotype distributions of the SMAD4 tSNPs in gastric cancer cases and controls and risk estimates n (%)

| SNP No. | SNP ID | Genotypes | Cases (n = 322) | Controls (n = 351)1 | P value (2df)2 | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)3 |

| 1 | rs12958604 | AA | 99 (30.8) | 106 (30.5) | 0.961 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| AG | 155 (48.1) | 171 (49.1) | 0.97 (0.68-1.38) | 0.98 (0.69-1.39) | |||

| GG | 68 (21.1) | 71 (20.4) | 1.03 (0.67-1.59) | 1.01 (0.66-1.56) | |||

| 2 | rs10502913 | GG | 164 (51.0) | 162 (46.4) | 0.505 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GA | 136 (42.2) | 161 (46.1) | 0.83 (0.61-1.14) | 0.86 (0.63-1.18) | |||

| AA | 22 (6.8) | 26 (7.5) | 0.84 (0.46-1.54) | 0.81 (0.44-1.49) | |||

| 3 | rs17663887 | TT | 307 (95.3) | 311 (88.6) | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| TC | 15 (4.7) | 40 (11.4) | 0.38 (0.21-0.70) | 0.38 (0.21-0.71) | |||

| 4 | rs9304407 | GG | 85 (26.4) | 112 (31.9) | 0.291 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GC | 179 (55.6) | 181 (51.6) | 1.30 (0.92-1.85) | 1.32 (0.93-1.87) | |||

| CC | 58 (18.0) | 58 (16.5) | 1.32 (0.83-2.09) | 1.29 (0.81-2.05) | |||

| 5 | rs12456284 | AA | 149 (46.3) | 143 (40.7) | 0.003 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| AG | 160 (49.7) | 170 (48.4) | 0.90 (0.66-1.24) | 0.90 (0.66-1.24) | |||

| GG | 13 (4.0) | 38 (10.8) | 0.33 (0.17-0.64) | 0.31 (0.16-0.60) |

No. of subjects in controls (n = 348 for SNP1, n = 349 for SNP2) were less than the total number (n = 351) because some DNA could not be genotyped;

Two-sided χ2 test for the frequency distribution;

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, and alcohol use. SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Considering the potential interactions of the tSNPs on risk of gastric cancer, we combined these two tSNPs based on the numbers of the protective alleles (i.e. SNP3 C and SNP5 G alleles). As shown in Table 4, the combined genotypes with zero and one protective allele were more common (0.429 and 0.518, respectively) and that with two and three protective alleles was less common (0.053 and 0.000, respectively) among the cases than the controls (0.362, 0.423, 0.154 and 0.011, respectively), and these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001). When these combined genotypes were dichotomized into two groups (i.e. 0-1 vs 2-3 protective alleles), their distributions differed significantly between the cases and controls (P < 0.001). In the association analyses, we found that the individuals with 2-3 protective alleles had a significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer (adjusted OR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.16-0.49) than those with 0-1 protective allele (Table 4). Further stratification analysis showed the same results as the main protective effect among subgroups of age, sex, smoking status, and drinking status (data not shown). However, no statistical evidence was observed for interactions between the combined genotypes and the variables (i.e. age, sex, tobacco smoking, and alcohol use) (data not shown).

Table 4.

Frequency distributions of the combined genotypes of SMAD4 SNP3 and SNP5 between gastric cancers and controls n (%)

| No. variant (protective) alleles of the combined genotypes1 | Cases (n = 322) | Controls (n = 351) | P2 | Adjusted OR (95% CI)3 |

| 0 | 138 (42.9) | 127 (36.2) | < 0.001 | |

| 1 | 167 (51.8) | 166 (42.3) | ||

| 2 | 17 (5.3) | 54 (15.4) | ||

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.1) | ||

| Dichotomized groups | ||||

| 0-1 | 305 (94.7) | 293 (83.5) | < 0.001 | 1.00 |

| 2-3 | 17 (5.3) | 58 (16.5) | 0.28 (0.16–0.49) |

0-3 represent the number of variants within the combined genotypes (0 = no variant and 1-3 = 1-3 variants); the variant (protective) alleles used for the calculation were the SNP3 C and SNP5 G alleles;

Two-sided χ2 test for the frequency distribution;

Odds ratios (ORs) were obtained from a logistic regression model with adjustment for age, sex, smoking status, and alcohol use. SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; CI: Confidence interval.

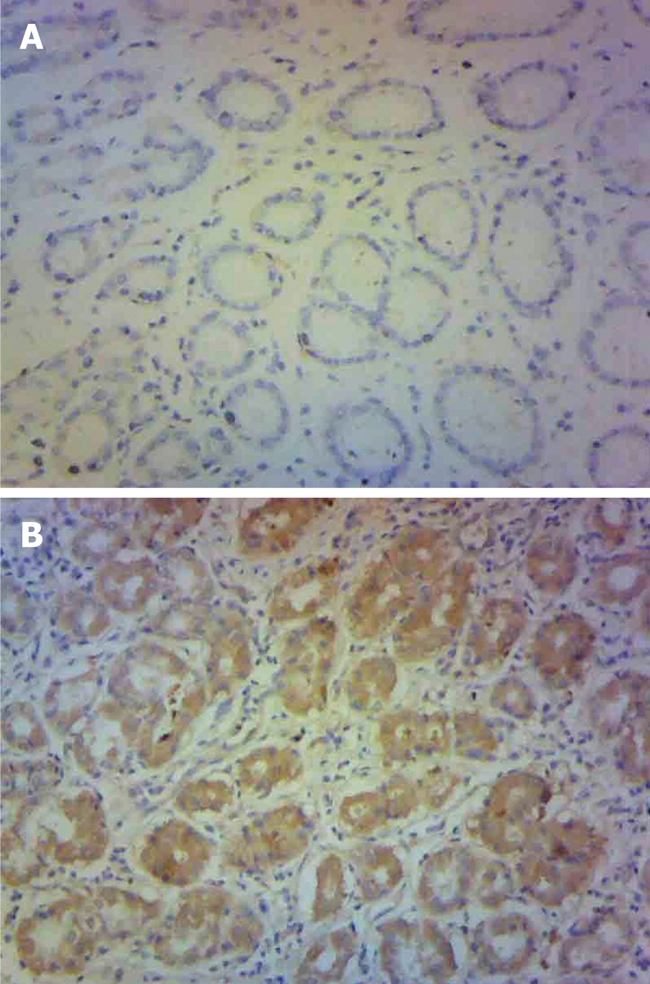

Based on the results of the genetic association studies of the SMAD4 combined genotype (0-1 vs 2-3 protective alleles) and gastric cancer, the SMAD4 protein expression of gastric cancer patients with 0-1 or 2-3 protective alleles was analyzed using immunohistochemistry. Four of the 10 patients had 2-3 protective alleles and six had 0-1 protective allele. SMAD4 was mainly expressed in the cytoplasm. Individuals with 0-1 protective allele had significantly decreased SMAD4 expression compared with those with 2-3 protective alleles (P = 0.025) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for SMAD4 in gastric tissues adjacent to tumor. HE, original magnification, 100 ×. A: Individuals with SMAD4 0 or 1 protective allele; B: Individuals with SMAD4 2 or 3 protective alleles.

To explore whether genetic variation in SMAD4 is associated with clinicopathological characteristics and disease progression, we performed additional stratified analysis of association between SMAD4 combined variant genotypes and risk of gastric cancer by the tumor sites (cardia and non-cardia), histological types (intestinal and diffuse), tumor infiltration (T1-T4), and lymph node metastasis (negative and positive). However, no significant association was observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this case-control study of gastric cancer, we investigated the associations of five tSNPs located in the intron (SNP1-4) and 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) (SNP5) of the tumor suppressor gene SMAD4 with risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Among these five tSNPs, we found that two variant genotypes (SNP3 TC and SNP5 GG) were associated with a significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer. When the protective alleles (SNP3 C and SNP5 G alleles) were evaluated together, we found that individuals with 2-3 alleles had a significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer compared with those with 0-1 protective allele. Furthermore, individuals with 0-1 protective allele had a significantly decreased SMAD4 protein expression level in normal tissues adjacent to tumors compared with those with 2-3 protective alleles. To the best of our knowledge, no published studies have investigated the role of SMAD4 polymorphisms in gastric cancer.

It has been shown that the loss of SMAD4 is a common feature of most human malignancies, and is associated with cancer progression[13]. Smad4 complete knockout mice can generate tumors throughout the gastrointestinal tract[25,26]. Experimental data also suggest that SMAD4 participates in immunosuppression. Absence of SMAD4 expression in thymic epithelial cells leads to functional change, and the number of early T-lineage progenitors is markedly reduced[27]. Selective loss of SMAD4 in T cells also leads to epithelial cancers throughout the gastrointestinal tract in mice[28]. SMAD4 appears to be a key regulatory protein of the SMAD4-dependent signaling in tumor carcinogenesis.

In the present study, we found an association of SMAD4 tSNPs with risk of gastric cancer. Moreover, SMAD4 protein expression levels were significantly different between individuals with 0-1 and 2-3 protective alleles. Although the underlying mechanism by which the mutated intron allele or 3’-UTR allele in the gene is associated with cancer risk remains elusive, there are two possible explanations. First, the mutant C allele of SNP3 rs17663887 that is located in intron 9 might produce/alter cis elements that allow/alter binding of transcription factors and thereby change SMAD4 expression. Using the Alibaba program (http://www.gene-regulation.com/cgi-bin/pub/programs/alibaba2), we found the transcription factors are altered when the SNP3 T allele mutates to C allele [i.e. T allele: C/EBPα (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α), HNF-3 (fork-head homolog 3), and AP-1 (activator protein 1); C allele: C/EBPβ (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β) and HSF (heat shock factor)]. Second, the mutant G allele of SNP5 rs12456284 that is located in the 3’-UTR might influence the potential miRNA binding and ultimately influence SMAD4 expression. Our immunohistochemistry assay partly supported these assumptions in vivo. However, the experiment needs to be done in normal gastric tissues and with larger sample sizes.

In this study, we found that SMAD4 polymorphisms might jointly provide protection against gastric cancer risk; individuals with 2-3 protective alleles had a significantly decreased risk of gastric cancer compared with those with 0-1 protective allele. This putatively supports the notion that a single polymorphism only contributes a modest effect and the combined variants of a gene might provide a more comprehensive evaluation of genetic susceptibility in candidate genes with low penetration. To date, few published epidemiological studies have investigated the associations between SMAD4 polymorphisms and human cancer. Only one case-control study has reported an association between the SMAD4 tSNPs and testicular germ cell tumor susceptibility in the US Servicemen’s Testicular Tumor Environmental and Endocrine Determinants Study[29]. Although they also selected the two tSNPs in the SMAD4 gene (i.e. rs9304407 and rs12456284) in their study, no association was found.

Kim et al[30] have reported that loss of SMAD4 protein expression is significantly associated with intestinal type gastric cancer. Later, they further reported that expression of SMAD4 was significantly lower in diffuse than intestinal-type gastric cancer[31]. Nevertheless, our analysis failed to find an association of SMAD4 polymorphisms with tumor histological types. Besides, Xiangming et al[12] and Kim et al[30] have reported that reduced expression of SMAD4 is related to the depth of tumor invasion. Our results did not find any correlation between the polymorphisms and tumor infiltration of gastric cancer. This could be attributable to different ethnicity and our relatively small sample size. Larger studies with different ethnic populations are needed.

Several limitations in our study need to be addressed. (1) The study design was hospital-based, which could have had inherent limitations that introduced selection bias, compared with population-based or cohort studies. However, the allele frequency in control subjects is close to that reported in the HapMap database for the CHB population; (2) We did not obtain enough information on H. pylori infection, and future studies with such information are needed; and (3) The relatively small sample size of 322 cases and 351 controls in the present study might not be large enough to identify significant gene-environment interactions, although we had > 85% power to detect an OR of ≥ 1.6 and ≤ 0.6, with an exposure frequency of 30% under the current sample size.

In conclusion, we found two tSNPs within the SMAD4 gene that were associated with a decreased risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. This is believed to be the first report of SMAD4 polymorphisms and gastric cancer, therefore, additional larger investigations and functional studies with more detailed environmental exposure data are warranted to validate these findings.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Epidemiological studies have identified many risk factors for gastric cancer that are involved in genetic susceptibility.

Research frontiers

Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4) is a central mediator of the transforming growth factor β signaling pathway, which acts as a tumor suppressor in numerous cancers. The relationship between SMAD4 gene polymorphism and gastric cancer needs to be addressed.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is believed to be the first study to examine the potential role of SMAD4 genetic variants in the occurrence of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Two tSNPs within the SMAD4 gene were found to be associated with a decreased risk of gastric cancer. Protein expression assays also support the association study results.

Applications

These findings might be of value in the explanation of gastric carcinogenesis. The observations also could be used as for further investigation of SMAD4 and gastric cancer.

Peer review

This paper is generally well prepared.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jian-Wei Zhou (Nanjing Medical University) for the help in part of the sample collection.

Footnotes

Supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 30800926, No. 30872084, No. 81001274, and No. 30972444; and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, No. BK2010080

Peer reviewer: Yeun-Jun Chung, MD, PhD, Professor, Director, Department of Microbiology, Integrated Research Center for Genome Polymorphism, The Catholic University Medical College, 505 Banpo-dong, Socho-gu, Seoul 137-701, South Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L. Incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:17–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epplein M, Nomura AM, Hankin JH, Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez G, Stemmermann GN, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection and diet on the risk of gastric cancer: a case-control study in Hawaii. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:869–877. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A, Pinheiro-Torres T, Pinto I, Santos-Pereira R, Lunet N. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:689–701. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Derynck R, Zhang Y, Feng XH. Smads: transcriptional activators of TGF-beta responses. Cell. 1998;95:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, Moskaluk CA, da Costa LT, Rozenblum E, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, et al. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science. 1996;271:350–353. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozenblum E, Schutte M, Goggins M, Hahn SA, Panzer S, Zahurak M, Goodman SN, Sohn TA, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ, et al. Tumor-suppressive pathways in pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1731–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyaki M, Iijima T, Konishi M, Sakai K, Ishii A, Yasuno M, Hishima T, Koike M, Shitara N, Iwama T, et al. Higher frequency of Smad4 gene mutation in human colorectal cancer with distant metastasis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3098–3103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schutte M, Hruban RH, Hedrick L, Cho KR, Nadasdy GM, Weinstein CL, Bova GS, Isaacs WB, Cairns P, Nawroz H, et al. DPC4 gene in various tumor types. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2527–2530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powell SM, Harper JC, Hamilton SR, Robinson CR, Cummings OW. Inactivation of Smad4 in gastric carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4221–4224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiangming C, Natsugoe S, Takao S, Hokita S, Ishigami S, Tanabe G, Baba M, Kuroshima K, Aikou T. Preserved Smad4 expression in the transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway is a favorable prognostic factor in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang LH, Kim SH, Lee JH, Choi YL, Kim YC, Park TS, Hong YC, Wu CF, Shin YK. Inactivation of SMAD4 tumor suppressor gene during gastric carcinoma progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:102–110. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leng A, Liu T, He Y, Li Q, Zhang G. Smad4/Smad7 balance: a role of tumorigenesis in gastric cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;87:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartsch D, Hahn SA, Danichevski KD, Ramaswamy A, Bastian D, Galehdari H, Barth P, Schmiegel W, Simon B, Rothmund M. Mutations of the DPC4/Smad4 gene in neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. Oncogene. 1999;18:2367–2371. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouras M, Tabone E, Bertholon J, Sommer P, Bouvier R, Droz JP, Benahmed M. A novel SMAD4 gene mutation in seminoma germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:922–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu W, Schönleben F, Li X, Su GH. Disruption of transforming growth factor beta-Smad signaling pathway in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as evidenced by mutations of SMAD2 and SMAD4. Cancer Lett. 2007;245:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pyatt RE, Pilarski R, Prior TW. Mutation screening in juvenile polyposis syndrome. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:84–88. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calva-Cerqueira D, Chinnathambi S, Pechman B, Bair J, Larsen-Haidle J, Howe JR. The rate of germline mutations and large deletions of SMAD4 and BMPR1A in juvenile polyposis. Clin Genet. 2009;75:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu D, Tian Y, Gong W, Zhu H, Zhang Z, Wang M, Wang S, Tan M, Wu H, Zhang Z. Genetic variants in the Runt-related transcription factor 3 gene contribute to gastric cancer risk in a Chinese population. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1688–1694. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goddard KA, Hopkins PJ, Hall JM, Witte JS. Linkage disequilibrium and allele-frequency distributions for 114 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in five populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:216–234. doi: 10.1086/302727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun X, Stephens JC, Zhao H. The impact of sample size and marker selection on the study of haplotype structures. Hum Genomics. 2004;1:179–193. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-1-3-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Wei D, Huang S, Peng Z, Le X, Wu TT, Yao J, Ajani J, Xie K. Transcription factor Sp1 expression is a significant predictor of survival in human gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6371–6380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takaku K, Miyoshi H, Matsunaga A, Oshima M, Sasaki N, Taketo MM. Gastric and duodenal polyps in Smad4 (Dpc4) knockout mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:6113–6117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu X, Brodie SG, Yang X, Im YH, Parks WT, Chen L, Zhou YX, Weinstein M, Kim SJ, Deng CX. Haploid loss of the tumor suppressor Smad4/Dpc4 initiates gastric polyposis and cancer in mice. Oncogene. 2000;19:1868–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeker LT, Barthlott T, Keller MP, Zuklys S, Hauri-Hohl M, Deng CX, Holländer GA. Maintenance of a normal thymic microenvironment and T-cell homeostasis require Smad4-mediated signaling in thymic epithelial cells. Blood. 2008;112:3688–3695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim BG, Li C, Qiao W, Mamura M, Kasprzak B, Anver M, Wolfraim L, Hong S, Mushinski E, Potter M, et al. Smad4 signalling in T cells is required for suppression of gastrointestinal cancer. Nature. 2006;441:1015–1019. doi: 10.1038/nature04846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purdue MP, Graubard BI, Chanock SJ, Rubertone MV, Erickson RL, McGlynn KA. Genetic variation in the inhibin pathway and risk of testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3043–3048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YH, Lee HS, Lee HJ, Hur K, Kim WH, Bang YJ, Kim SJ, Lee KU, Choe KJ, Yang HK. Prognostic significance of the expression of Smad4 and Smad7 in human gastric carcinomas. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:574–580. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JY, Park DY, Kim GH, Choi KU, Lee CH, Huh GY, Sol MY, Song GA, Jeon TY, Kim DH, et al. Smad4 expression in gastric adenoma and adenocarcinoma: frequent loss of expression in diffuse type of gastric adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:543–549. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]