Abstract

Objectives

Altered choline (Cho) metabolism in cancerous cells can be used as a basis for molecular imaging with PET using radiolabeled Cho. In this study, the metabolism of tracer Cho was investigated in a woodchuck hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell line (WCH17) and in freshly-derived rat hepatocytes. The transporter responsible for [11C]-Cho uptake in HCC was also characterized in WCH17 cells. The study helped to define the specific mechanisms responsible for radio-Cho uptake seen on the PET images of primary liver cancer such as HCC.

Methods

Cells were pulsed with [14C]-Cho for 5 min and chased for varying durations in cold media to simulate the rapid circulation and clearance of [11C]-Cho. Radioactive metabolites were extracted and analyzed by radio-HPLC and radio-TLC. The Cho transporter (ChoT) was characterized in WCH17 cells.

Results

WCH17 cells showed higher 14C uptake than rat primary hepatocytes. [14C]-Phosphocholine (PC) was the major metabolite in WCH17. In contrast, the intracellular Cho in primary hepatocytes was found to be oxidized to betaine (partially released into media) and to a less degree, phosphorylated to PC. [14C]-Cho uptake by WCH17 cells was found to have both facilitative transport and non-facilitative diffusion components. The facilitative transport was characterized by Na+ dependence and low affinity (Km = 28.59 ± 6.75 μM) with partial energy dependence. In contrast, ChoT in primary hepatocytes is Na+ independent and low affinity.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that transport and phosphorylation of Cho are responsible for the tracer accumulation during [11C]-Cho PET imaging of HCC. WCH17 cells incorporate [14C]-Cho preferentially into PC. Conversion of [14C]-PC into phosphatidylcholine occurred slowly in vitro. Basal oxidation and phosphorylation activities in surrounding hepatic tissue contribute to the background seen in [11C]-Cho PET images.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, radiolabeled choline, positron emission tomography, choline transporter, choline metabolism, choline kinase, lipid synthesis, phosphocholine, betaine

Introduction

As the predominant type of primary liver cancer, hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC) has seen a rapid increase in its incidence over the last 10 years in U.S.A 1. This increase is thought to be caused, in part, by an increased rate of hepatitis viral infections. The strategies to improve the early detection of HCC, by way of positron emission tomography (PET), are of clinical importance.

The most commonly used PET imaging tracer 2-[18F]-fluoro-deoxyglucose (FDG) is effective in detecting many tumors. However, FDG has been shown to be ineffective for imaging HCC since up to 50% HCC do not uptake and retain FDG compared to the surrounding hepatic tissues 2. FDG uptake has consistently been observed in poorly-differentiated HCCs (the late stage of HCC) and associated with poor prognosis 2–3.

Up-regulated choline (Cho) uptake, relative to benign lesions and normal tissue, has been used as a diagnostic marker for cancer 4–5. It has been suggested that carcinogenesis is associated with the up-regulation of choline kinase (ChoK) activity, resulting in increased levels of phosphocholine (PC) 4, 6–10. Furthermore, it is also known that rapidly proliferating tumors contain large amounts of phospholipids, particularly phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) 4–5. In our previous tracers comparison study 2, well-differentiated HCC lesions (the early stage of HCC) were distinguished visually and by standardized uptake value (SUV) on PET/CT imaging with radiolabeled Cho as tracer despite observable Cho uptake at the surrounding hepatic tissue. Longer half life 18F labeled Cho derivative [18F]fluorocholine (FCH) has also been applied to HCC in a proof of concept study 11. FCH PET/CT showed a detection rate of 100% for both poorly and well-differentiated HCC, both newly diagnosed and recurrent HCC in this study. A higher FCH SUVmax was also observed in well-differentiated HCC as compared to poorly-differentiated HCC. This makes radiolabeled Cho potentially useful for early detection and/or staging of HCC. However, the interpretation of Cho PET images of HCC becomes complicated due to the different imaging contrasts observed in well- and poorly-differentiated HCC. In order to fully exploit the diagnostic potential of PET imaging on well-differentiated HCC with radiolabeled Cho, it is necessary to confirm the underlying biochemical mechanisms of [methyl-11C]-Cho leading to contrast uptake in HCC.

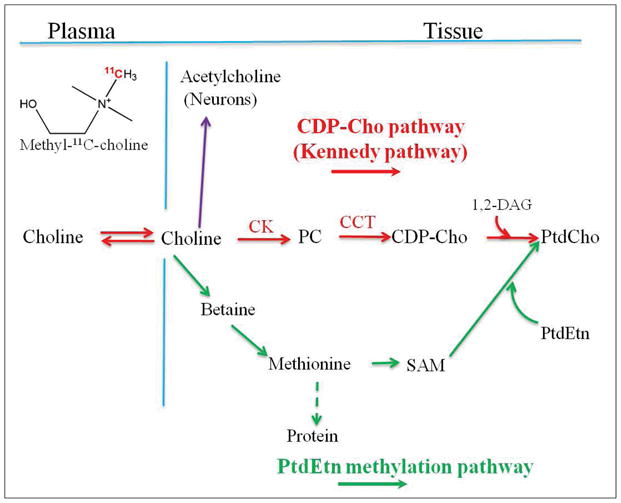

Cho is a quaternary ammonium base and crucial for mammalian cells. All cells utilize Cho as a precursor for the biosynthesis of phospholipids (e.g. PtdCho) which are essential components of all membranes 10, 12. Cho metabolism is cell and tissue specific. After intravenous injection, [methyl-11C]-Cho is rapidly cleared from the blood circulation. Blood sampling has shown that the predominant metabolite of radiolabeled Cho in blood is betaine 10. Cho is transported into the cell by both facilitative transport mechanisms and passive diffusion. A diagram of possible intracellular metabolic fates of Cho is shown in Figure 1. In the cytoplasm, Cho is phosphorylated by ChoK to PC. PC is the first intermediate in the stepwise incorporation of Cho into phospholipids by the cytidinediphosphocholine (CDP-Cho) pathway (also called Kennedy pathway). In the next step, PC is converted to CDP-Cho by catalysis of cytidine triphosphate (CTP):phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT). CDP-Cho can further react with 1,2-diacylglycerol (1,2-DAG) to produce PtdCho. In neurons, Cho can also convert to acetylcholine, an important neurotransmitter.

Figure 1.

Metabolic fate of radiolabeled choline. 1, 2-DAG: 1,2-diacylglycerol; CCT: CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase; CDP-Cho: CDP-choline; ChoK; choline kinase; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; PC: phosphocholine; PtdCho: phosphatidylcholine; PtdEtn: phosphatidylethanolamine; P.I.: post injection; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine.

In hepatocytes and renal cells, Cho can also be oxidized to betaine aldehyde, which is then converted to betaine by the enzyme system of Cho oxidase (Cho dehydrogenase and betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase) 10. Betaine serves as an organic osmolyte in cells (i.e. compound which is accumulated or released by cells in order to maintain cell volume homeostasis) 8. Betaine, cannot be reduced to form Cho, but it can also donate one of its methyl groups and be converted to methionine (Met) 10, 12. Met can also become incorporated into PtdCho via phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) methylation pathway (Figure 1).

1H and 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) have been proved useful in evaluating the Cho containing metabolites change during hepatocarcinogenesis. Significant increases in total Cho-containing compounds (tCho) and PC were observed in tumor cells as compared to normal cells, and PC contributes up to 80% of the tCho spectral profiles in quantitative 1H MRS analyses 13. 1H MRS showed tCho/lipid ratio was significantly higher in the HCC region of an experimental rat model than the liver region of normal rats 14. 31P MRS further confirmed that an increase in phosphoethanolamine (PE) and PC signals and a decrease in glycerophosphorylethanolamine (GPE) and glycerophosphorylcholine (GPC) signals in patients with hepatic malignancies 15. Meanwhile, although transport and phosphorylation of Cho were faster in cancer cells, the turnover of PtdCho appeared to proceed at about same rate in both the cancer and normal cells due to the similar control of the rate-limiting CDP-Cho synthesis 16. It is believed that both biosynthetic and catabolic PC-cycle pathways may contribute to the increased MRS-detected PC levels in cancer cells 13. However, Cho metabolites concentrations measured by MRS failed to correlate with FCH or [11C]-Cho uptake imaged by PET in prostate cancer, glioma, sarcoma etc, alluding to the possibility that increased Cho spectral peaks on MRS may not specifically reflect the accumulation of injected tracer amount of radiolabeled Cho on PET 17–20. Thus, the finding of Cho metabolites changes in cancer cells measured by MRS might not be able to use to explain the uptake mechanism of radiolabeled Cho seen on PET images.

Rommel et al. proposed several biological hypotheses to explain the failed correlation between FCH uptake and Cho metabolite concentration 17, 19–20. One possibility is the presence of a negative feedback mechanism of elevated levels of intracellular Cho compounds on FCH uptake. Another possibility is rapid transport and incorporation of Cho into membrane PtdCho which is not detectable by 1H-MRS. Fujibayshi et al 21 and DeGrado et al 22–23 have investigated the metabolism of radiolabel Cho in cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. These studies all found that radiolabeled PC was the major metabolite in cancers responsible for the Cho uptake in PET imaging and radiolabeled PC converting to PtdCho occurred very slowly during 40–60 min dynamic scan. Nevertheless, we have investigated the in vivo metabolism of radiolabeled Cho in woodchuck model of HCC (reported separately). The metabolism pattern of radiolabeled Cho was more complicated than the previous reports of radiolabeled Cho metabolism in other cancers. Interestingly, at early time point (12 min post-injection), increased radiolabeled Cho uptake in HCCs is associated with the transport and phosphorylation of Cho; at late time point (30 min post-injection), increased radiolabeled Cho uptake reflects increased PtdCho synthesis derived from radiolabeled CDP-Cho in HCCs. The exact mechanism(s) of radiolabeled Cho uptake in HCC are still not well understood yet. Uncertainties still exist and further studies are necessary.

A better elucidation of the transport and metabolism of radiolabeled Cho in HCC will pave the way to further developments of PET imaging with radiolabeled Cho for early detection of HCC, staging and therapy response follow-up. It may also help to identify the metabolic targets for potential HCC therapy methods. Thus, we start with this cell culture study to map out a clear figure about the mechanism regarding PET imaging with radiolabeled Cho in HCC. In addition, the use of cultured WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes allows us to control potentially confounding variables, such as blood flow and necrosis, which are present when studying these biochemical parameters in animal tumor models or in human tumors.

In this study, the metabolism of radiolabeled Cho was characterized in a well-differentiated woodchuck HCC cell line (WCH17) and in freshly-derived rat hepatocytes. WCH17 is a well-differentiated cell line derived from an adult woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV)-induced woodchuck hepatoma by Bruce Fernie (Georgetown University). WHV belongs to the family hepadnaviridae, of which human hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the prototype. This cell line has not been extensively characterized, but is similar to human cell lines such as PLC/PRF/5 and Hep3B, in which HBV incorporation into the genome can be detected. We also defined the mechanisms responsible for Cho transport in WCH17 cells.

Due to the very short physical half life of 11C (20 minutes), 14C labeled Cho was used at the imaging tracer dose for this study. The metabolites were analyzed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). In order to confirm the metabolite analysis results from HPLC, the metabolites were also analyzed by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC). Detailed radiotracer metabolites analysis and Cho transporter assay enable us to unravel the mechanism underlying the imaging contrast seen in PET imaging of HCC with radiolabeled Cho.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

All chemical reagents used were obtained from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. [methyl-14C]-Cho chloride (specific activity 1.85–2.22 GBq/mmol), was obtained from American radiochemical Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Liver Perfusion Medium, Liver Digest Medium, L-15 Medium, Hepatocyte Wash Medium, Percoll (from GE), William’s Medium E, HepatoZYME SFM, hexobarbital, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and penicillin-streptomycin were obtained from Invitrogen Co. (Carlsbad, CA). WCH17 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). Organic solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Cell cultures

Primary rat hepatocytes were freshly prepared as a negative control according to the collagenase-dispase method described previously 24–26. Approximately 5 × 106 rat hepatocytes in 25 ml of William’s medium E, supplemented with 5ml penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 unit/ml penicillin, 10μg/ml streptomycin) and 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), were plated in 100-mm tissue culture dishes precoated with a Collagen I matrix (12.5 μg/cm2) and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 10% CO2 in air at 37°C. Unattached cells were poured off 2–3 hours after plating and the medium was replaced with 25 ml HepatocyteZYME-SFM.

WCH17 cells in the exponential phase were trypsinized and 1 × 107 cells were plated in 75 cm2 corning cell culture flasks with 10 ml DMEM (Contains 28.5μM Cho choride, 4,500 mg/L D-glucose, L-glutamine, and 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate; GIBCO/Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin solution (10,000 unit/ml penicillin, 10μg/ml streptomycin) under a 10% CO2-humidified atmosphere at 37°C. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, 24 hours after plating.

[Methyl-14C]-Choline uptake and metabolism

Cells were incubated in 10 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 74 KBq of [14C]-Cho chloride (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc., St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. After incubation, the medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS), trypsinised with 3 ml of trypsin for 5 min and neutralized with 3 ml of ice-cold DMEM. The cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1500 ×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold 1.2 ml water containing 100 mg/l of the antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and homogenized on ice for 3 min.

Pulse-chase study and excretion

Cells were incubated in 10 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 370 KBq of [14C]-Cho (specific activity: 2.035 MBq/μmol) for 5 min at 37°C (pulse). After incubation, the media were removed and the cells were washed three times with PBS. The cells were then incubated in 10 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS containing 18 μM of non-radioactive Cho for 10, 25, 40 and 55 min (chase). Either 1% bovine BSA with 1 mM sodium oleic acid (treated) or without oleic acid (untreated) was added to the chase media. After the chase, the media were collected and separated into water-, lipid-soluble and insoluble phase as described below to characterize the excretion of radioactive metabolites. The cells were rinsed with PBS twice, trypsinised with 3 ml trypsin and neutralized with 3 ml of ice-cold DMEM. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1600 ×g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1.2 ml water containing 100 mg/l BHT and homogenized on ice for 3 min.

Extraction of radiolabeled metabolites using Bligh and Dyer method

From each 1.2 ml homogenate, 0.1 ml was used to measure the total radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting. Another 0.1 ml of homogenate of cell pellets was used for protein measurement using Bradford method (Bio-Rad labortaries, Inc., Hercules, CA) 27. Radioactive insoluble (including RNA, DNA and proteins), water- and lipid-soluble metabolites from [14C]-Cho in the remaining 1 ml of cell homogenate were separated using the Bligh and Dyer method 28. After gentle evaporation under the nitrogen gas, the lipid-soluble fraction was redissolved in 0.7 ml of chloroform/methanol (2/1, v/v) and the water-soluble fraction, in 0.7 ml of methanol/water (1/1, v/v). From each re-dissolved fraction, 0.1 ml was used for measuring the total radioactivity content with scintillation counting. The radioactivity from each fraction was normalized by the protein content. The Bligh and Dyer method was also used to separate the insoluble, water- and lipid-soluble metabolites in the chase media. The radioactivity in each fraction was normalized by the media volume.

Analysis of radiolabeled metabolites

(1) HPLC and TLC

The HPLC system consisted of a Hewlett-Packard HP1050 (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA), a 1050 pump (isocratic and quaternary), a 1050 Diode Array and Multiple UV Wavelength detector, a temperature controller (Waters Co., Milford, MA), connected to a Radiomatic 150TR Flow Scintillation Analyzer (PerkinElmer; Waltham, Massachusetts). The water-soluble metabolites were separated on an Adsorbosphere Silica normal-phase HPLC column (250×4.6mm, Prevail Silica 5μ; Grace Davidson Discovery Sciences Inc., Deerfield, IL) with a guard column (Guard 7.5×4.6mm, Prevail Silica 5μ; Grace Davidson Discovery Sciences Inc., Deerfield, IL). Silica gel G plate with concentration zone (Merck KGaA, Gibbstown, NJ) was used for TLC analysis.

(2) Water-soluble metabolites analysis

For HPLC, the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile/water/ethyl alcohol/aceticacid/0.83M Sodium acetate 800:127:68:2:3 (v:v:v:v; pH 3.6; Buffer A) and 400:400:68:53:79 (v:v:v:v; pH 3.6; Buffer B) 29. A linear gradient from 0 to 100% buffer B, with a slope of 5%/min, was started 15 min after initiation of the elution. The flow rate was 2.7 ml/min and the column temperature was maintained at 45°C. The 14C-labeled metabolites: betaine, betaine aldehyde, Cho, CDP-Cho and PC were identified by comparing their retention times to those of 14C-labeled standard compounds (American radiochemical Inc.; St. Louis, MO) (Supplemental Figure 3).

In order to confirm the metabolite results from HPLC, water-soluble metabolites were also applied to TLC analysis. For TLC, the mobile phase consisted of methanol/0.5% NaCl/aqueous ammonium (100:100:2, v:v:v) 30. The water-soluble metabolites were separated and identified via comparing the retention factor (Rf) with the 14C-labeled standards (Supplemental Figures 5a). The plates were exposed on an imaging storage phosphor screen (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and the exposed screens were scanned with a bio-imaging analyzer (Typhoon Variable Mode Imager, GE, Piscataway, NJ) to quantify the incorporation of radioactivity in each metabolite.

(3) Lipid-soluble metabolites analysis

Different mobile phases were used to separate phospholipids and neutral lipids with HPLC. For phospholipids, the mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile/hexane/methanol/phosphoric acid (918:30:30:7.5,v:v:v:v) 31. The flow rate was 1.5 ml/min. For neutral lipids ([14C]-Cho does not incorporate into neutral lipids), the mobile phase consisted of hexane/isopropanol/acetic acid (100:2:0.02, v:v:v) 32. The flow rate was 2 ml/min. Non-radioactive lipid metabolites were detected by the UV detector at 206 nm. All metabolites were identified by comparing their retention times with [14C]-labeled lipid standards (American radiochemical Inc.; St. Louis, MO) (Supplemental Figure 4).

In order to confirm the metabolite results from HPLC, phospholipids and neutral lipids were also separated into individual metabolites with TLC. An aliquot of the fraction was spotted on a silica gel G plate (Merck KGaA, Gibbstown, NJ) and eluted in chloroform/methanol/water (60:30:5, v:v:v) up to 7cm The plate was dried and eluted again in hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (80:20:1.5, v:v:v) for 17 cm (from the origin of spotting) 33. The lipid-soluble metabolites were separated and identified via comparing the retention factor (Rf) with the 14C-labeled standards. (Supplemental Figure 5b)

[Methyl-14C]-betaine uptake in WCH17 cells

[14C]-betaine was prepared from [14C]-Cho by Cho oxidase based on the method previously published 29 (Supplemental Figure 3b). [14C]-betaine uptake in WCH17 cells was measured as previously described 21.

Kinetics of choline transport in WCH17 cells in vitro

(1) Kinetics of choline transport in WCH17 cells and effects of lithium-for-sodium replacement

The choline transporter (ChoT) assay followed a procedure described previously 23, 34. Briefly, WCH17 cells (3×105 cells) were cultured in 24-well plates with 1 ml DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution in a 10% CO2-humidified atmosphere at 37°C. The assay was performed when replacing the medium with the uptake medium (20 mM HEPES/Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 141 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM glucose), by incubating the cells with 5 to 500 μM choline (containing 1.54KBq 14C-Cho for each well) at 37°C for 5 minutes. The uptake medium was removed and the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS three times and scraped for scintillation counting. The sodium dependence of the transporter was examined by repeating the experiments using DMEM containing 141 mM LiCl instead of 141 mM NaCl.

(2) Inhibition of choline transporter in WCH17 cells

ChoT inhibition with 20–200 mM hemicholinium-3 (HC-3) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.2 and 2.0 mM ouabain (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or 0.2 and 2.0 mM dinitrophenol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was carried out during the 15 min prei-ncubation and incubation periods of the ChoT assay. HC-3 is a potent inhibitor of. Ouabain and dinitrophenol are metabolic inhibitors. Ouabain was used to determine the sensitivity of choline transport rates to inhibition of Na/K-dependent adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase). The oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler dinitrophenol was used to inhibit of cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

(3) Parameter Estimation for choline transporter in WCH17 cells

The uptake rate from transporter assay was then fit by the nonlinear least-squares curve fitting algorithm 23 to the following equation including a passive diffusion term:

| (Eq. 1) |

where [S] (μM) is the Cho concentration, [I] (μM) is the inhibitor concentration, Vmax (nmol/mg protein/min) and KM (μM) are the Michaelis-Menten constants for maximal transport velocity and concentration at half-maximal velocity, respectively, KI (μM) is the inhibition constant of WCH17 cells, and D (mL/mg protein/min) is the diffusion coefficient. The model assumes Michealis-Menten kinetics, competitive inhibition of the ChoT by different inhibitors, and first-order diffusion kinetics.

Assay of ChoK in WCH17 cells

WCH17 cells were trpsinzed and homogenized in chilled extraction buffer pH 7.5 (30 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 3% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 2% adult bovine serum, 10 μM TPCK, 10 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor, 1μM leupeptin, 0.75 mg/ml DTT, 0.4 mg/ml PMSF). The cell homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for the assay as described by Ishidate and Nakazawa 35 with modification. Briefly, The assay mixture (300 μl ) contained 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM ATP, 12 mM MgCl2, 10 μM Cho, [14C]-Cho (0.7 MBq per assay mixture). After a 30 min incubation at 37°C, The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 ml chloroform/methanol (2/1, v/v). The reaction mixture was separated into two phases by centrifugation. To decrease the methanol concentration, 0.65 ml of 12 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) was added to the upper (aqueous) phase. The ion-pairing reagent sodium tetraphenylboron (TPB) in heptan-4-one (1 ml of a 5 mg/ml solution of TPB) was added into the mixture. After vigorous mixing for 5 min and phase separation by brief centrifugation, the radioactivity content in the lower phase, which contained the synthesized [14C]-PC, was measured with liquid scintillation. Chok activity was normalized to total protein content.

HC-3 effect on phosphocholine production in WCH17 cells

In order to investigate the PC production with the HC-3 effects on both choline transporter and choline kinase in WCH17 cells, WCH17 cells were incubated with culture media containing HC-3 and analyzed the PC production36. Following HC-3 incubation for 30 min, cells with HC-3 containing medium were added 74 KBq [14C]-Cho chloride per 7 cm3 flask and incubated for 1 hour. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS, and then detached by cell lysis buffer. Cells were then resuspended in 0.5 ml chloroform/methanol (2/1, v/v) solution. The mix was then separated into two phases by centrifugation. The lower (aqueous) phase from this step was added with 0.65 ml of 12 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) to decrease the methanol concentration. The ion-pairing reagent sodium tetraphenylboron (TPB) in heptan-4-one (1 ml of a 5 mg/ml solution of TPB) was then added into the resultant mixture. After being vigorously mixed for 5 min and phase separation by brief centrifugation, the lower phase containing produced [14C]-PC from [14C]-Cho during the enzyme reaction was use to determine the radioactivity using a liquid scintillation counter. The activity of whole cell Chok was normalized to total protein content. WCH17 cells with non HC-3 incubation were used as a control.

Liquid scintillation counting

Radioactivity of 14C was determined with a Beckman LS-6500 Liquid Scintillation Counter (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA) with Bio-safe II (Fisher Scientific Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) as the scintillation fluid. Disintegrations per minute (dpm) were obtained by correcting for background activity and efficiency based on calibrated standards.

Statistical analysis

All data, unless otherwise stated, are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data were compared using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or ANOVA on ranks, when appropriate. All pairwise multiple comparison procedures used Tukey test. Differences were regarded as statistically significant for p < 0.05.

The r2 statistic was used as a test of goodness of fit of parameter estimation for kinetics of ChoT in WCH17 cells 23:

| (Eq. 2) |

where yi is the measured uptake rate, ȳ is the mean uptake rate; and ŷi is the model-predicted uptake rate at the ith measurement.

Results

[Methyl-14C]-Choline uptake patterns and metabolism in WCH17 cells and primary rat hepatocytes

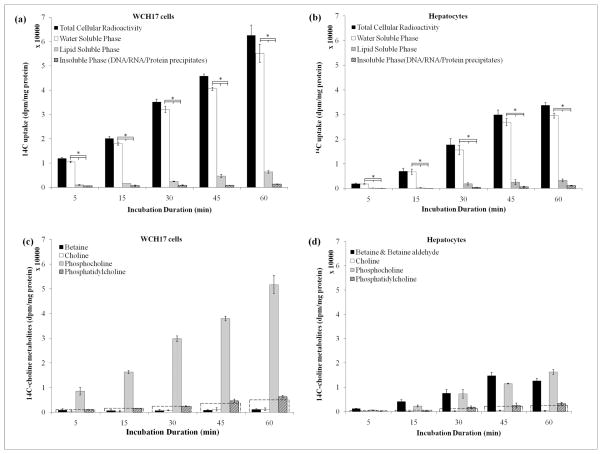

The radioactivity retained in different fractions in WCH17 cells and primary rat hepatocytes after incubation with [14C]-Cho is showed in Figure 2. In both cells, the total 14C content increased with longer incubation durations. WCH17 cells contained significantly more radioactivity than rat hepatocytes for any incubation durations (p < 0.05). Approximately 90% of the radioactivity in WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes was found in the water-soluble fraction. Only 10% of the total radioactivity retained was in lipid-soluble fraction and insoluble fraction of both cells. On the other hand, we measured [14C]-betaine uptake in WCH17 cells. WCH17 took up significantly less [14C]-betaine, a major metabolite of choline found in blood, as compared to the uptake of [14C]-Cho. This suggests that a metabolite correct input function has to be done in order to get a true input function of 11C-Cho PET imaging.

Figure 2.

Time course of incorporation of [14C]-Cho into lipid-, water-soluble and insoluble phases (a) WCH17 cells; (b) Primary rat hepatocyes, *: p < 0.05.; Metabolites derived from [14C]-Cho for different incubation durations in (c) WCH17 cells and (d) rat hepatocytes. To put the result into perspective, a dotted line corresponding to 10% of the total retained radioactivity was graphed at each time point.

HPLC analysis showed differences in the metabolism of [14C]-Cho between WCH17 cells and rat hepatocyes (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 6). In WCH17 cells, the radioactivity was mainly found in the water-soluble fraction (87.0–91.8% of total accumulation in cells) (Figure 2a) and [14C]-PC was the main metabolite (Figure 2c) and Supplemental Figure 6a). The levels of [14C]-PC increased with longer incubation durations in WCH17 cells and accounted for over 94% of radioactivity in the water-soluble fraction, indicating transported high rate of [14C]-Cho phosphorylation. Only 7% of total uptake radioactivity was found in [14C]-PtdCho, which the only metabolite in the lipid-soluble fraction. The levels of the [14C]-Cho/betaine pool were significantly lower than [14C]-PC. There was no [14C]-CDP-Cho detected.

In contrast, although over 90% of radioactivity in rat hepatocytes was also found in the water-soluble fraction, the major radioactive metabolites were [14C]-PC and [14C]-betaine (Figure 2d). For incubation durations, [14C]-betaine accounted for approximately 55% of the radioactivity in the water-soluble fraction. The remaining 45% was found in [14C]-PC. Only relatively small levels of radioactivity were detected in [14C]-PtdChp. Similar to WCH17 cells, there was no [14C]-CDP-Cho detected.

The levels of [14C]-PC and [14C]-PtdCho were significantly higher in WCH17 than in rat hepatocytes (p < 0.05). However, the levels of [14C]-betaine were significantly lower in WCH17 than in rat hepatocytes (p < 0.05).

Metabolites derived from 14C-Choline are retained in WCH17 cells whereas they are excreted as 14C-betaine in hepatocytes

Radiolabel Cho has a rapid circulation and clearance during PET imaging. In order to mimic this in vivo condition, we used pulse-chase experiments to investigate the transient change of the intracellular metabolites of [14C]-Cho and the radiolabeled metabolites excreted from cells.

To simulate the rapid blood circulation and clearance of [methyl-14C]-Cho, WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes were pulsed with [14C]-Cho for 5 min followed by incubation in non-radioactive medium containing cold Cho for 0, 10, 25, 40 and 55 min to simulate the time period of a dynamic PET scan. Supplemental Figure 7 showed the representative HPLC radiochromatograms of metabolites derived from [methyl-14C]-Cho in WCH17 cells and primary rat hepatocytes at pulse-chase experiments.

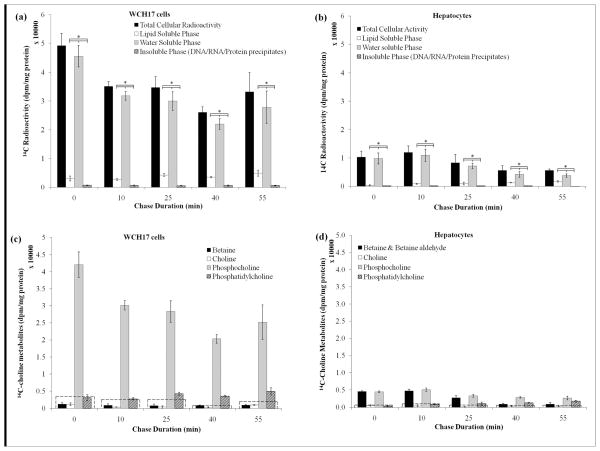

[14C]-Cho was metabolized differently in WCH17 cells and in rat hepatocytes (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 5) at pulse-chase experiments. The total radioactivity retained in WCH17 cells decreased rapidly after the pulse. However it remained stable for any chase duration (Figure 3a). Over 80%–90% of total radioactivity was found in the water-soluble fraction. In contrast, the total radioactivity retained by hepatocytes decreased with increasing chase durations, suggesting increased excretion of radioactive metabolites synthesized from [14C]-Cho (Figure 3d). Nevertheless, most of the radioactivity was still found in the water-soluble fraction. Only 5%–10% of the total retained radioactivity was in the lipid - soluble and insoluble fractions in WCH17 cells, while 20–35 % of the total radioactivity was found in the lipid–soluble fraction in rat hepatocyte over 40 min chase duration rat hepatocytes. Significantly more radioactivity was found in WCH17 cells than in rat hepatocytes for any chase duration (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Pulse-chase study on the metabolism of [14C]-Cho in WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes. The chase time at 0 represent the radioactivity after the initial 5-min pulse (no chase). (a) Incorporation of [14C]-Cho into different fractions in WCH17 cells. (b) Incorporation of 14C-Cho into different fractions in rat hepatocytes. *: p < 0.05. Metabolites derived from [14C]-Cho for different incubation durations in (c) WCH17 cells and (d) rat hepatocytes. To put the result into perspective, a dotted line corresponding to 10% of the total retained radioactivity was graphed at each time point.

In WCH17 cells, most of the radioactivity in the water-soluble fraction was found in [14C]-PC (Figure 3c). The conversion of [14C]-PC to [14C]-PtdCho occurred slowly within the 55-min chase duration (Figure 3c, Supplemental Figure 7). [14C]-Cho and [14C]-betaine represented less than 10% of the total retained radioactivity in WCH17 cells. In rat hepatocytes, [14C]-Cho was rapidly oxidized to [14C]-betaine or phosphorylated to [14C]-PC (Figure 3d and Supplemental Figure 7). Less than 2% of the total retained radioactivity was associated with [14C]-Cho for any chase durations. Betaine aldehyde was also found immediately after the pulse in some cases (Supplemental Figure 7c). The levels of radioactivity measured in [14C]-PC and [14C]-PtdCho were significantly higher in WCH17 cells than in rat hepatocytes (p < 0.05). However, the measured levels of [14C]-betaine were significantly lower in WCH17 cells than in rat hepatocytes (p < 0.05).

Supplemental Figure 1 show the radioactivity in the media during the chase period. In the chase media of WCH17 (Supplemental Figure 1a), the total activity remained stable for any chase duration. Over 99 % of the radioactivity was in the water-soluble fraction. TLC analysis showed that the main radioactive metabolite in the chase media from WCH17 cells was [14C]-Cho, representing at least 98% of the total radioactivity in the media. [14C]-betaine was also detected but represented at most 2% of the radioactivity in the media. In the chase media from the experiments with rat hepatocytes, the main metabolites identified were [14C]-Cho and [14C]-betaine.

Unsaturated fatty acids increase the amount of radioactivity derived from 14C-Cho incorporated into 14C-PtdCho

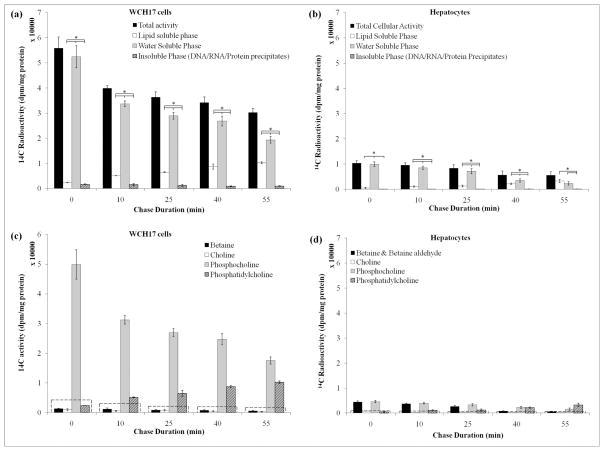

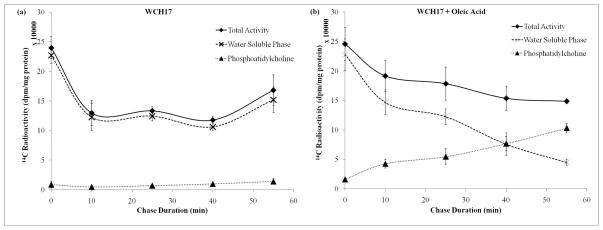

The addition of 1 mM oleic acid into the chase media increased the incorporation of [14C]-Cho into lipid-soluble metabolites in both cells and PtdCho was the main metabolite identified (Figure 4). Concomitantly, a decrease in the radioactivity found in PC in both WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes was observed (Figure. 4c, 4d). The total radioactivity retained in both cells did not change as compared to untreated cells. When we changed the pulse and chase media from culture media DMEM to PBS, the effect was much obvious (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of oleic acid on the phosphatidylcholine synthesis in culture media. Cells were incubated with [14C]-Cho for 5 min (pulse) then the radioactivie media was removed and replaced with DMEM with 10% FBS containing 1% BSA/1 mM sodium oleate (oleic acid-treated). The cells were then incubated further (chase). The chase time at 0 represent the radioactivity after the initial 5-min pulse. (a) Incorporation of [14C]-Cho into different fractions in WCH17 cells. (b) Incorporation of [14C]-Cho into different fractions in rat hepatocytes. *: p < 0.05. Metabolites derived from [14C]-Cho for different incubation durations in (c) WCH17 cells and (d) rat hepatocytes. To put the result into perspective, a dotted line corresponding to 10% of the total retained radioactivity was graphed at each time point.

Figure 5.

Effect of oleic acid on the phosphatidylcholine synthesis in PBS. Cells were incubated with [14C]-Cho for 5 min (pulse) then the radioactive media was removed and replaced with PBS containing 1% BSA/1 mM sodium oleate (oleic acid-treated). The cells were then incubated further (chase). The chase time at 0 represent the radioactivity after the initial 5-min pulse. (a) Incorporation of [14C]-Cho into water soluble phase and phosphatidylcholine in WCH17 cells. (b) Incorporation of [14C]-Cho into water soluble phase and phosphatidylcholine in WCH17 cells with addition of oleic acid.

Transport of Cho in WCH17 cells is carrier-mediated and sodiumdependent

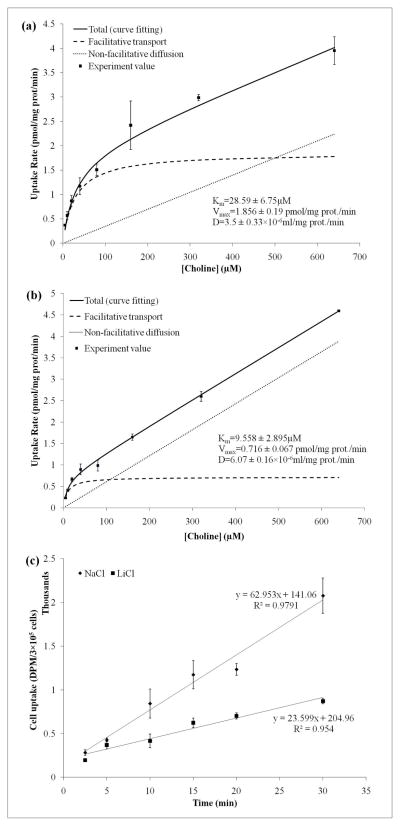

We followed the previously reported procedure to investigate the kinetics of Cho uptake in WCH17 cells and determine whether ChoT mediates the increased transport of Cho in WCH17 cells 23. Uptake rates were measured over substrate concentrations ranging between 5 and 640 μM (Figure 6a). The experimental data were fitted into a Michaelis-Menten model that included both facilitative transport and passive diffusion terms (Eq. 1). The facilitative component had a low estimated affinity (KM = 28.59 ± 6.75 μM) (Table 1). Passive diffusion became dominant at Cho concentrations greater than 500 μM when sodium was present, but at concentrations greater than 120 μM in the absence of sodium (Figure 6b). In the absence of sodium, the Vmax value decreased to 0.716 ± 0.067 pmol/mg protein/min and the KM value decreased to 9.558 ± 2.895 uM, indicating that the uptake mechanism was sodium-dependent in WCH17 cells. This was supported by the time-course of [14C]-Cho uptake and metabolism by WCH17 cells (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Characterization of [14C]-Cho transport in WCH17 cells and investigation of sodium dependence of the transporter. (a) Standard medium containing 141 mM sodium. (b) Medium in which sodium was replaced with 141 mM lithium. Lines show the fit of the experimental data to the modified Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq. 1). (c) Time-course of 14C-Cho uptake using NaCl-containing or LiCl-containing media

Table 1.

Parameter of 14C-Cho transport in WCH17 cells estimation by nonlinear least-squares.

| Conditions | Facilitative transport parameters | HC-3 inhibition KI | Non-facilitative diffusion parameter | Goodness of fit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax (pmol/mg prot/min) | Km (μM) | KI(μM) | D × 10−6 (ml/mg prot./min) | r2 | |

| Control | 1.856 ± 0.19 | 28.59 ± 6.75 | — | 3.5 ± 0.33 | 0.9843 |

| Li+ for Na+ Replacement | 0.716 ± 0.067* | 9.558 ± 2.895* | — | 6.07 ± 0.16* | 0.9954 |

| 0–200 μM HC-3 | 1.339 ± 0.079 | 15.03 ± 2.877* | 23.8 ± 5.472 | 5.9 ± 0.17* | 0.9951 |

HC-3: hemicholinium-3; KI: enzyme inhibition constant; KM: Michaelis constant; Vmax: maximum velocity.

p <0.05 versus control.

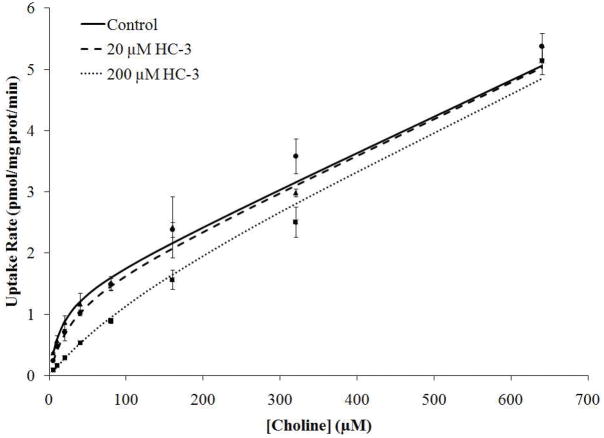

Choline transporter is inhibited by HC-3, ouabain, dinitrophenol and is sodium-dependent

The effect of HC-3 on the Cho uptake and metabolism by WCH17 cells was also examined. HC-3 inhibited facilitative choline transport and the extent of inhibition was concentration-dependent (KI = 23.8 ± 5.472 μM). Passive diffusion of [14C]-Cho was not affected by HC-3 (Table 1 and Figure 7). This value suggests that the potency of HC-3 as an inhibitor of ChoT in WCH17 cells is intermediate between that of hCHT1 (<1 μM) and the markedly lower potency of hOCT1 or hOCT2 (<250 μM) 22, 37–38. These results are similar to those previously obtained in the prostate cancer cells PC-3 23.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of [14C]-Cho transport in WCH17 cells by HC-3. Lines show the fit of the data to the modified Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq 1).

We also investigated the effects of ouabain (0.2–2 mM) and of the oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler dinitrophenol (0.2–2mM) on ChoT into WCH17 cells (Table 2). Ouabain was the most potent inhibitor of ChoT but did not affect passive diffusion (p < 0.05). The result suggested that the inhibition was dependent on ouabain concentration and was somewhat greater in magnitude at the low concentration of Cho (5 μM vs. 640 μM Cho). The sensitivity of ChoT to low concentrations of ouabain is consistent with the inhibition of transport of positively charged Cho molecules as the membrane potential is diminished 23. In addition, metabolic inhibition with the oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler dinitrophenol resulted in a concentration dependent decrease in Cho uptake and metabolism, but the inhibition was not as strong as with ouabain.

Table 2.

Effect of other inhibitors on the accumulation of radioactivity derived from 14C-Cho in WCH17 Cells

| Incubation medium | Choline Uptake (pmol/mg protein/min) |

|

|---|---|---|

| At 5 μM Choline | At 640 μM Choline | |

| Control medium | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 3.95 ± 0.29 |

| Na+ replaced by K+ | 0.15 ± 0.01*,a | 4.64 ± 0.31 |

| Na+ replaced by K+ after preincubation for 60 min | 0.19 ± 0.0015*,b | 4.09 ± 0.25 |

| Na+ replaced by 0.25 M surcose | 0.44 ± 0.04*,a,b | 4.59 ± 0.26 |

| + 0.2 mM Ouabain | 0.24 ± 0.01*,c | 4.10 ± 0.52 |

| + 2 mM Ouabain | 0.03 ± 0.0018*,c | 4.28 ± 0.26 |

| + 0.2 mM 2,4- dinitrophenol | 0.09 ± 0.0025*,d | 4.21 ± 0.12 |

| + 2 mM 2,4-dinitrophenol | 0.03 ± 0.001*,d | 4.36 ± 1.10 |

Control medium: 10mM HEPES/Tris buffer (pH 7.4), 141mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose.

p < 0.05 versus control.

the pairwise multiple comparison (tukey test), p < 0.05

These data confirmed the importance of a facilitative transport process for radiolabeled Cho uptake into tumor cells that was most sensitively inhibited with a reduction in Na/K-dependent ATPase activity by ouabain.

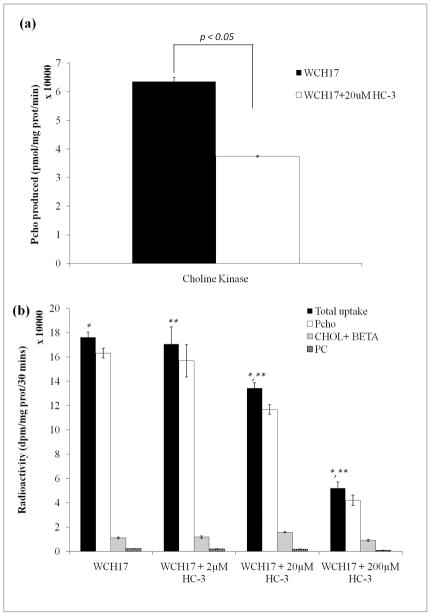

HC-3 inhibition on choline kinase activity in WCH17 cells

In order to investigate the association between ChoK activity and HC-3 inhibition, ChoK activity was assayed with or without HC-3 being added into assay buffer. The cytosolic ChoK activity was decreased by 3 folds in WCH17 cells when 20 μM HC-3 was added to the assay buffer (Figure 8a). Whole cell ChoK activity was also evaluated by incubating WCH17 cells with [14C]-Cho with or without HC-3 and measuring intracellular PC levels by HPLC. Treatment of WCH17 cells with HC-3 produced a concentration-dependent decrease in PC production (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

HC-3 inhibition on choline kinase activity in WCH17 cells. (a) In vitro cytosolic Cho kinase activity in WCH17 cells. (b) Whole cell choline kinase activity in WCH17 cells. *, **: p < 0.05

Discussion

It has been demonstrated that malignant transformation of cancer cells is associated with the elevated levels of Cho metabolites 39–40. This has been the basis for differentiating between malignant and benign lesions using PET imaging with [11C]-Cho for HCC 41–45. However, the metabolic alterations responsible for the increased accumulation of [11C]-Cho in liver tumors have never been characterized, which limits our understanding of the usefulness of this radiotracer for PET imaging of HCC. In this study, the metabolism of radiolabeled Cho was characterized in a liver cancer cell line and in freshly-derived hepatocytes. The transport mechanism in HCCs was also investigated.

In this study, the level of [14C]-PC were significantly higher in WCH17 cells than in rat hepatocytes in both incubation and pulse-chase experiments, suggesting that radiolabeled Cho is predominantly metabolized through the CDP-Cho pathway in WCH17 cells. This was also supported by the low levels of [14C]-betaine retained or secreted in WCH17 cells. Low levels of [14C]-PtdCho were measured, supporting the findings of others that CCT is a rate-limiting for PtdCho synthesis in HCC in vitro. These results suggest that radioactive PC is the main metabolite responsible for the increased [11C]-Cho accumulation in HCC compared to the normal hepatocytes in vitro. On the other hand, rapid synthesis of betaine and phosphorylation to PC by basal ChoK activity were the main pathways of [14C]-Cho metabolism in rat hepatocytes. Roivainen et al. suggest the major metabolite in the blood was [14C]-betaine undergoing [14C]-Cho PET scans 10. However, we only found a little amount of [14C]-betaine in WCH17 cells as compared to primary rat hepatocytes. It indicates that the synthesis of betaine might be impaired in HCC cells. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Cho phosphorylation is augmented in the course of malignant transformation in HCC.

High levels of intracellular PC in cancer cells were previously shown to correlate with up-regulation of ChoK 46. Tracer kinetic studies also showed that enhanced ChoT may play a role in the elevation of PC levels in malignant cells 23. To the best of our knowledge, the transport processes of Cho have not been fully investigated in HCC. Previous studies showed Km values for ChoT in various cancer cells ranging between 1 and 60 μM, which is in the same range as the physiologic concentrations of Cho in plasma (5–50 μM) 23. These estimated Km values in cancer cells were between the neuronal high-affinity process (hCHT1) and the lower-affinity human ChoT-like protein (hCTL) 1 and human organic cation transporter (hOCT) family of transporters present in peripheral tissues 23. hCHT1 in the central nervous system has a high affinity (Km < 10 μM, HC KI ~100 μM) and is sodium-dependent while hOCT in the liver and kidneys has a low affinity (Km > 10 μM, , HC KI ~0.001-0.1 μM) and is sodium-independent 47. Different ChoTs may determine different metabolism pathways, hCHT provides Cho for acetylcholine synthesis while hOCT routes Cho to phospholipid synthesis 47. In addition, a specific ChoT is located in the inner membrane of normal liver mitochondria, where Cho is oxidized to betaine 48–50. This ChoT showed saturated kinetics at high membrane potential with a Km of 220 μM and a Vmax of 0.4 nmol/mg protein/min. HC-3 inhibited this ChoT with KI value of 17 μM. The presence of a ChoT in the mitochondrial inner membrane provides a site for control of choline oxidation and hence supply of endogenous betaine.

In this study, the ChoT in WCH17 cells was not strictly fallen into any of hCHT, hOCT or ChoT for betaine categories. Our study showed that at low concentrations Cho is taken up by WCH17 cells mainly by a facilitative transport process. At Cho concentrations higher than 500 μM, passive diffusion becomes the predominant transport pattern. The facilitative transport of Cho in WCH17 cells has a low affinity for Cho (Km >10 μM) but is sodium-dependent. And HC-3 inhibited ChoT in WCH17 cells with a KI of 23.8 ± 5.472 μM. Moreover, ChoT in WCH17 cells can be inhibited by two Na+/K+-dependent ATPase related inhibitors ouabain and dinitrophenol. This suggested that ChoT in WCH17 cells might be partial energy dependent. Contrary to these features of ChoT in WCH17 cells, ChoT in rat hepatocytes belongs to hOCT (low affinity) with a Km of 12 μM and sodium independent 51–52. Another study showed ChoT has a Km of 170 μM in perfused rat livers, which might include two ChoT components, one involving hOCT, the other involving ChoT for betaine systhesis in mitochondria membrane 53.

The transport system for Cho in some non-cholinergic mammalian tissues (cells) including WCH17 cells and primary rat hepatocytes were summarized in Table 3. The rate of PC biosynthesis does not appear to be influenced significantly by the rate of Cho transport in most nonproliferating cells such as rat liver and rat kidney cortex 54–55. In addition, for these nonproliferating cells, Cho is metabolized through both the CDP-Cho pathway and the betaine oxidation pathway. However, in Novikoff hepatoma cells 56, Cho is rapidly converted to PC without detectable accumulation of other Cho metabolites, supporting the importance of the CDP-Cho pathway in cancer cells observed in our studies.

Table 3.

Characteristics of carrier-mediated choline transport in mammalian cells

| Cells | Km (μM) | Specific features and notes | Intracellular fate of choline [choline concentration with which cells were incubated] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Woodchuck hepatoma WCH17 | 28.59 ± 6.75 | Na+ dependent; Competitive inhibition by HC-3, ouabain, dinitrophenol at low concentration of Cho; Simple diffusion : [Cho]> 500 μM. | PC (90%) → CDP- Cho→PC. [18.8μM] |

| Rat liver 53 | 170 | Simple diffusion: [Cho]>300 μM in the perfusate | Betaine (60%); PC (30%); Cho (10%). [5- 125 μM] |

| Rat hepatocytes 51–52 | 12 | Nonsaturable uptake: [Cho]>40μM in the culture media; Depression by a cAMP analogue or aminophylline | Betaine (57%); PC (33%); Cho (10%). [40 μM] |

| Rat Kidney cortex 61 | ATP and Na+ dependent; inhibition by HC-3 and other structural analogues of Cho | Betaine (80%); PC (10%). [200 μM] | |

| Novikoff hepatoma cells 56, 62 | 4–7 | Simple diffusion: [Cho]>20μM in the culture media; competitive inhibition by phenethylalcohol; uptake process is rate limiting for PC synthesis with extracellular Cho concentration below 20μM | PC → CDP-Cho→PC. [20μM] PC (95%). [100 μM] |

| Hep G2 23, 63–64 | 11 (Low concentration of Cho) 347 (high concentration of Cho) |

PC (95%) → CDP- Cho→PC. | |

| Prostate cancer cells PC-3 22–23 | 9.7 ± 0.8 | Partial Na+ dependent; Competitive inhibition by HC-3, ouabain, dinitrophenol at low concentration of Cho; Simple diffusion : [Cho]> 200 μM. | PC (90%) → CDP- Cho→PC. [5μM] |

It has been suggested that cellular uptake of radiolabeled Cho is dependent on ChoT and ChoK activities. Kwee et al. also reported that abnormal expression of one or both proteins was observed in most malignancies 18. ChoT was believed as the rate-limiting step for Cho uptake during PET imaging in HCC 23, 56. In this study, pre-treatment of WCH17 cells with HC-3, an inhibitor of ChoT and ChoK-mediated phosphorylation 57, resulted in a decrease of [14C]-Cho accumulation intracellularly. This further suggested the specific pathway of radiolabeled Cho, which is the CDP-Cho pathway in HCC during PET imaging. Although HC-3 acts as an inhibitor of ChoT and ChoK-mediated phosphorylation, the increased activity of ChoK in WCH17 cells to phosphorylate Cho and then trap it intracellularly was observed in ChoT assay and kinetics study of HC-3 inhibition. This indicated that ChoT was a rate-limiting step for radiolabeled Cho uptake in HCC. Thus, intracellular phosphorylation by ChoK is unlikely to be rate-limiting, but it plays an important role in trapping the Cho tracer in the HCC cells to provide higher tumor to liver contrast for useful imaging purposes. Furthermore, our previous in vivo PET imaging with radiolabeled Cho in HCC was agreed well with the rate-limiting role of ChoT for Cho uptake. In our previous tracer comparison study, woodchuck HCCs showed a higher ChoK activity than surrounding hepatic tissue 2. Despite the normal physiology uptake of [11C]-Cho in surrounding hepatic tissue, a higher uptake of Cho was quantitatively observed in HCC regions after a rapid blood clearance of Cho tracer (<3 min) 2. The enhanced uptake of Cho to allow visualization in PET images of HCC even in the presence of rapid blood clearance of tracer suggested a high dependence of tumor uptake on efficient transport from blood circulation into HCC cells.

As mentioned above, although ChoT was a rate-limiting step for radiolabeled Cho uptake in HCC, the radiolabeled Cho accumulation inside the HCC cells may reflect intracellular metabolic event. Fujibayashi et al. investigated the metabolism of [14C]-Cho in ten tumor cell lines and found that the PC produced from [14C]-Cho by phosplorylation mainly contributed to the tracer accumulation in tumor cells 21. Higher [14C]-Cho uptake was correlated with proliferative activity 21. Degrado et al. also investigated the metabolism of FCH in glioma in vitro and in vivo and found that FCH has similar metabolic pattern with [11C]-Cho 22. PC derivated from radiolabeled Cho is the main metabolite in glioma cells 22. Both studies showed the conversion to PtdCho from radiolabeled PC occurred very slowly within 60 min post-injection. This suggested that it is a rate-limiting step for PtdCho synthesis from PC catalyzed by CCT. These findings are in agreement with the results obtained in this study. However, radiolabeled PC incorporated into PtdCho very rapidly in our in vivo [14C]-Cho metabolism study in woodchuck HCCs at 30 min post-injection (reported separately). The rapid incorporation of FCH relative to [14C]choline into lipids in HCCs was a surprising result that requires further investigation.

Abel et al. has suggested that there are altered lipid profiles in premalignant lesions in rat liver 58. During hepatocarcinogenesis, the molecular species of PtdCho and PtdEtn may change as compared to surrounding hepatic tissues. In the endogenous lipid components of HCC nodule tissues, C18:1ω9 (oleic acid) and C18:2ω6 (linoleic acid) increased in PtdCho and PtdEtn, while C20:4ω6 (arachidonic acid) decreased in PtdCho and increased in PtdEtn; C22:5ω6 (docosapentaenoic acid) and C22:6ω3 (decosahexaenoic acid) decreased in PtdCho and PtdEtn 58. This changed fatty acid profiles in HCCs may cause distinct microenvironments between HCCs and the surrounding hepatic tissues, which may induce different metabolism pattern between in vivo and in vitro. This motivated us to add oleic acid into the pulse media during the pulse-chase experiment in order to investigate the cause of discrepancy of radiolabeled Cho metabolism between in vivo and in vitro. In the present study, an increased PtdCho synthesis from [14C]-PC during chase period was observed in WCH-17 cells or rat hepatocytes when oleic acid was added to the pulse media. When we changed the pulse and chase media to PBS and repeated this experiment again with an addition of oleic acid, the acceleration of radiolabeled PtdCho synthesis was much obvious. It is believed that short-chain unsaturated fatty acid like oleic acid activates CCT and/or translocates CCT from cytosol to ER membrane to facilitate the PtdCho synthesis 54. It suggested that the changed endogenous lipid profiles in HCC may stimulate radiolabeled PtdCho synthesis which we observed in vivo. Further investigations comparing the relationship between radiolabeled Cho uptake and related enzymatic activity, lipid profiles within specimens from HCC tumors are needed.

PET imaging for HCC is still evolving. The sensitivity of PET in diagnosis of HCC using FDG was 55% although FDG can detect distant metastases from HCC. This is because FDG cannot be taken up by well-differentiated HCCs due to the higher glucose-6-phosphatase activity in well-differentiated HCCs 2. Our previous study has demonstrated that [11C]-acetate (Act) may be a complementary tracer to FDG for PET imaging of HCC, which can be used for detected well-differentiated HCC 2. The detection rate was 16/17 HCCs with a tumor to liver ratio (T/L) of 2.02 ± 0.7. The one which was not detected by [11C]-Act was a moderate differentiated HCC. However, [11C]-Act has shown increased uptake in the benign tumors, such as adenoma, hemangioma and focal nodular hyperplasia etc 59. We have also demonstrated Cho is an appropriate PET tracer for imaging well-differentiated HCC 2. [11C]-Cho detected all the HCCs with a T/L of 1.63 ± 0.34 in our previous tracers comparison study 2. The advantage of radiolabeled Cho is that it can be useful for detecting not only well-differentiated but also poorly-differentiated HCCs 18. It has also shown uptake in distant metastatic HCCs 18. In a proof of concept study, FCH detected all 9 patients (100%) in contrast to 5 with FDG (56%) 18. FCH can detect as small as 9 mm HCC lesions visually and by SUV 18. Most interestingly, the uptake of FCH in well-differentiated HCCs is higher than that in poorly-differentiated HCCs, whose mechanism is still unclear. DeGrado et al. also reported the usefulness of FCH on the detection of recurrent hepatoma 60. These features make radiolabeled Cho a potential one-stop approach for early detection, diagnosis, staging and treatment assessment for HCCs.

For quantitative PET studies of HCCs with radiolabeled Cho, it is important to understand the transport and metabolism of administered radiolabeled Cho in order to study tracer kinetics via compartment modeling analysis. In the present study, we investigated the transport and metabolism of radiolabeled Cho responsible for Cho uptake in HCCs during PET imaging. In the time activity curve of [11C]-Cho in human plasma during PET imaging, [11C]-Cho is rapidly metabolized to [11C]-Betaine after bolus injection and released in the blood where it represents an increasing proportion of the total radioactivity until 20 min (after which the [11C]-betaine levels stabilize)10. In this study, WCH17 cells had low uptake of [14C]-betaine. This suggests that the levels of radioactive betaine in the blood must be measured and subtracted from the total blood radioactivity when deriving the input function when performing pharmacokinetic analysis of [11C]-Cho metabolism in HCC. Meanwhile, facilitative transport should be assumed for the parameter of influx rate between blood compartment and liver or HCCs compartment based on the ChoT assay in this study.

Moreover, for the intracellular metabolism of radiolabeled Cho, the major metabolite in WCH17 cells during the chase period was [14C]-PC, which is significantly higher than that in normal hepatocytes. It indicated that a higher rate of Cho phosphorylation should be expected in HCCs in parameter estimation of modeling analysis as compared to the same parameter from surrounding hepatic tissue. On the other hand, Cho transported into the primary hepatocytes was rapidly oxidized to betaine or phosphorylated to Pcho. Thus, the parameter of influx rate between free Cho compartment and metabolized Cho compartment in normal liver should represent a combination of Cho oxidation and phosphorylation.

In addition, radiolabeled PC rapidly converted to radiolabeled PtdCho in HCC at 30 min of PET imaging in vivo, whose accumulation pattern is different with in vitro data and the data from using the xenograft model. This metabolic pattern should be considered for interpretation of dynamic PET images of HCC with radiolabeled Cho. Taken together, the study reported herein will be useful for the development and validation of a compartment model for Cho tracer kinetic analysis. The model would enable the estimation of the higher rate of Cho transport into HCC and the higher rate of its phosphorylation as compared to surrounding hepatic tissue. Such parameters could be quantitatively useful, for example, for early detection of HCC and/or following the efficacy of a HCC patient’s therapy.

Our in vitro mechanistic study was appropriate in obtaining basic information on transport and metabolism of radiolabeled Cho in HCC cells without the confounding impacts, such as microenviroments, non-neoplastic cells, precancerous cells and competing plasma substrates etc. Validation of the applicability of these in vitro observations to in vivo situation requires in vivo evaluation of patterns of Cho metabolism in experimental and human HCC tumors.

Conclusion

Facilitative transport of radiolabeled Cho dominates over passive diffusion in WCH17 cells. Enhanced Cho transport and augmented synthesis of PC are the dominant mechanisms responsible for the increased accumulation of radioactivity derived from radiolabeled Cho in WCH17 cells compared with hepatocytes. Radiolabeled Cho is metabolized to PC and oxidized to betaine in rat hepatocytes. Conversion of PC to PtdCho was slow in both lines in vitro.

Supplementary Material

Excretion of trapped 14C radioactivity into chasing media during pulse-chase experiment. (a) Excretion of radioactive fraction by WCH17 cells at different times after the 5-min [14C]-Cho pulse. (E) Excretion of radioactive fraction by by rat hepatocytes at different times after the 5-min [14C]-Cho pulse.

Excretion of trapped 14C radioactivity into chasing media during pulse-chase experiment with the addition of oleic acid. (a) Excretion of radioactive fraction by WCH17 cells at different times after the 5-min [14C]-Cho pulse. (E) Excretion of radioactive fraction by by rat hepatocytes at different times after the 5-min [14C]-Cho pulse.

Representative HPLC radiochromatograms of water soluble metabolites derived from 14C-choline. (a) 14C-labeled standards: 14C-betaine, 14C-choline, 14C-CDP-Cho, 14C-PC; (b) Preparation of betaine from [methyl-14C]-choline. Incubation of [methyl-14C]-Cho with Cho oxidase to form of betaine aldehyde and betaine. Upper panel: 1-min incubation; lower-left panel: 3-min incubation. Lower-right panel: 10-min incubation. Abbreviation: SF: solvent front; Bet: Betaine; Cho: Choline; CDP-Cho: CDP-choline; PC: phosphocholine; Bet Ad.: Betaine aldehyde.

Representative HPLC radiochromatograms of lipid soluble metabolites derived from 14C-choline. (a) [14C]-labeled standards of phoshpholipids: 14C-PtdIns, 14C-PtdSer, 14C-PtdEtn, 14C-PtdCho, 14C-LysoPtdCho, 14C-SM. Two small inserts are the chromatograms of LPC and SM under UV light (206 nm). There is a time delay between UV detector and radiodetector. (b) [14C]-labeled standards of neutral lipids: 14C-fatty acid, 14C-1,3-DAG (2 peaks), 14C-1,2-DAG, 14C-Cholesterol. Abbreviation: SF: solvent front; PtdIns: phosphatidylinositol; PtdSer: phosphatidylserine; PtdEtn: phosphoethanolamine; PtdCho: phosphatidylcholine; LysoPtdCho: lysophosphatidylcholine; SM: sphingomyeline; 1,2-DAG: 1,2-diacylglycerol; 1,3-DAG:1,3-diacylglycerol.

Separation of water- and lipid-soluble metabolites with TLC. (a) TLC of 14C-labeled standards of water-soluble metabolites. Lane 1, [14C]-betaine; Lane 2, [14C]-Cho; Lane 3, [14C]-PC; Lane 4, [14C]-CDP-Cho; Lane 5, mix of 14C-betaine, [14C]-choline, [14C]-PC and [14C]-CDP-Cho; incubation of [14C]-Cho with Cho oxidase to form betaine aldehyde and betaine (Lane 6, 1-min incubation; Lane 7, 3-min incubation and Lane 8, 10-min incubation). (B) TLC of 14C-labeled standards of lipid-soluble metabolites. a. LysoPtdCho; b. SM; C: PtdCho; d: PtdIns + PtdSer; e: PtdEtn; f: MAG; g: 1,3-DAG; h: 1,2-DAG + Cholesterol; i: free fatty acid; j: TAG. Abbreviation: SF: solvent front; PtdIns: phosphatidylinositol; PtdSer: phosphatidylserine; PtdEtn: phosphoethanolamine; PtdCho: phosphatidylcholine; LysoPtdCho: lysophosphatidylcholine; SM: sphingomyeline; MAG: monoacylglycerol; 1,2-DAG: 1,2-diacylglycerol; 1,3-DAG:1,3-diacylglycerol.

Representative HPLC radiochromatograms of radioactive metabolites in WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes incubated for different durations with [14C]-Cho. (a) Water-soluble metabolites in WCH17 cells. (b) Phospholipid metabolites in WCH17 cells. (c) Water-soluble metabolites in rat hepatocytes. (d) Phospholipid metabolites in rat hepatocytes

Representative HPLC radiochromatograms of radioactive metabolites in WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes pulsed for 5 min with [14C]-Cho and chased for different durations. (a) Water-soluble metabolites in WCH17 cells. (b) Phospholipid metabolites in WCH17 cells. (c) Water-soluble metabolites in rat hepatocytes. (d) Phospholipid metabolites in rat hepatocytes

Representative HPLC radiochromatograms of radioactive metabolites metabolites in WCH17 cells and rat hepatocytes pulsed for 5 min with [14C]-Cho and chased for different durations in media with oleic acid. (a) Water-soluble metabolites in WCH17 cells when oleic acid was added in the chase media. (b) Phospholipid metabolites in WCH17 cells when oleic acid was added in the chase media. (c) Water-soluble metabolites in rat hepatocytes when oleic acid was added in the chase media. (d) Phospholipid metabolites in rat hepatocytes when oleic acid was added in the chase media.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Visvanathan Chandramouli, Dr. Bill Schumann, Dr. Ann-Marie Broome and Ms. Irene Panagopoulos. They have provided very useful discussions and laboratory techniques. We would also like to thank Dr. Jim Basilion for sharing lab resources. This work was supported by an NIH/NCI R01 grant CA095307 (PI: Zhenghong Lee). Relevant supporting materials for this paper can be found online. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

List of Abbreviation

- 1H-MRS

proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- Act

Acetate

- BHT

Butylated Hydroxytolune

- CCT

CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase

- CDP-Cho

CDP-choline

- ChoK

choline kinase

- Cho

choline

- ChoT

choline transporter

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FCH

[18F]-fluorocholine

- FDG

2-[18F]-2-deoxy-fluoro-D-glucose

- GPC

glycerophosphocholine

- GPE

glycerophosphoethanolamine

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HC

hemicholinium

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- hCHT1

neuronal high-affinity process

- hCTL

the lower-affinity human ChoT-like protein

- hOCT

human organic cation transporter

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- lysoPtdCho

lysophosphatidylcholine

- Met

methionine

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- P.I

post injection

- PtdCho

phosphatidylcholine

- PtdEtn

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PC

phosphocholine

- PE

phosphoethanolamine

- PEMT

phosphatidylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase

- PET

positron emission tomography

- Rf

retention factor

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SUV

standardized uptake value

- tCho

total choline containing compounds

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- T/L

tumor to liver ratio

- WHV

woodchuck hepatitis virus

References

- 1.Gharib AM, Thomasson D, Li KC. Molecular imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004 Nov;127(5 Suppl 1):S153–158. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salem N, Kuang Y, Wang F, Maclennan GT, Lee Z. PET imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma with 2-deoxy-2[(18)F]fluoro-D-glucose, 6-deoxy-6[(18)F] fluoro-D-glucose, [(1–11)C]-acetate and [N-methyl-(11)C]-choline. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009 Jun;53(2):144–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salem N, MacLennan GT, Kuang Y, et al. Quantitative evaluation of 2-deoxy-2[F- 18]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography imaging on the woodchuck model of hepatocellular carcinoma with histological correlation. Mol Imaging Biol. 2007 May-Jun;9(3):135–143. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz-Brull R, Degani H. Kinetics of choline transport and phosphorylation in human breast cancer cells; NMR application of the zero trans method. Anticancer Res. 1996 May-Jun;16(3B):1375–1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeisel SH. Choline phospholipids: signal transduction and carcinogenesis. FASEB J. 1993 Apr 1;7(6):551–557. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.6.8472893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishidate K. Choline/ethanolamine kinase from mammalian tissues. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1997 Sep 4;1348(1–2):70–78. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright PS, Morand JN, Kent C. Regulation of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in Chinese hamster ovary cells by reversible membrane association of CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1985 Jul 5;260(13):7919–7926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wettstein M, Weik C, Holneicher C, Haussinger D. Betaine as an osmolyte in rat liver: metabolism and cell-to-cell interactions. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md. 1998 Mar;27(3):787–793. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wajda IJ, Manigault I, Hudick JP, Lajtha A. Regional and subcellular distribution of choline acetyltransferase in the brain of rats. J Neurochem. 1973 Dec;21(6):1385–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb06024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roivainen A, Forsback S, Gronroos T, et al. Blood metabolism of [methyl-11C]choline; implications for in vivo imaging with positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000 Jan;27(1):25–32. doi: 10.1007/pl00006658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talbot JN, Gutman F, Fartoux L, et al. PET/CT in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using [(18)F]fluorocholine: preliminary comparison with [(18)F]FDG PET/CT. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2006 Nov;33(11):1285–1289. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeisel SH. Dietary choline: biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacology. Annu Rev Nutr. 1981;1:95–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.01.070181.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podo F. Tumour phospholipid metabolism. NMR Biomed. 1999 Nov;12(7):413–439. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199911)12:7<413::aid-nbm587>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Li X, Yang ZH, Xie JX. In vivo 1H MR spectroscopy in the evaluation of the serial development of hepatocarcinogenesis in an experimental rat model. Academic radiology. 2006 Dec;13(12):1532–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox IJ, Bell JD, Peden CJ, et al. In vivo and in vitro 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of focal hepatic malignancies. NMR Biomed. 1992 May-Jun;5(3):114–120. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940050303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz-Brull R, Seger D, Rivenson-Segal D, Rushkin E, Degani H. Metabolic markers of breast cancer: enhanced choline metabolism and reduced choline-ether-phospholipid synthesis. Cancer Res. 2002 Apr 1;62(7):1966–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwee S, Ernst T. Total Choline at 1H-MRS and [18F]-Fluoromethylcholine Uptake at PET. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010 May 11; doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwee SA, DeGrado TR, Talbot JN, Gutman F, Coel MN. Cancer imaging with fluorine-18- labeled choline derivatives. Semin Nucl Med. 2007 Nov;37(6):420–428. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rommel D, Bol A, Abarca-Quinones J, et al. Rodent Rhabdomyosarcoma: Comparison Between Total Choline Concentration at H-MRS and [(18)F]-fluoromethylcholine Uptake at PET Using Accurate Methods for Collecting Data. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009 Nov 25; doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0283-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rommel D, Duprez TP. Usefulness of Multimodal Investigations of the Choline Pathway. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010 May 11; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshimoto M, Waki A, Obata A, Furukawa T, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. Radiolabeled choline as a proliferation marker: comparison with radiolabeled acetate. Nuclear medicine and biology. 2004 Oct;31(7):859–865. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal A, Shuyan W, Hara T, Harris RA, Degrado TR. Biodisposition and metabolism of [(18)F]fluorocholine in 9L glioma cells and 9L glioma-bearing fisher rats. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2008 Feb 9; doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0736-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara T, Bansal A, DeGrado TR. Choline transporter as a novel target for molecular imaging of cancer. Mol Imaging. 2006 Oct-Dec;5(4):498–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guengerich FP. Isolation and purification of cytochrome P-450, and the existence of multiple forms. Pharmacol Ther. 1979;6(1):99–121. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(79)90057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry MN, Friend DS. High-yield preparation of isolated rat liver parenchymal cells: a biochemical and fine structural study. J Cell Biol. 1969 Dec;43(3):506–520. doi: 10.1083/jcb.43.3.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsson A, Sundler R, Akesson B. Biosynthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol in isolated rat-liver parenchymal cells. Effect of albumin-bound fatty acids. Eur J Biochem. 1973 Nov 15;39(2):613–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959 Aug;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liscovitch M, Freese A, Blusztajn JK, Wurtman RJ. High-performance liquid chromatography of water-soluble choline metabolites. Anal Biochem. 1985 Nov 15;151(1):182–187. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yavin E. Regulation of phospholipid metabolism in differentiating cells from rat brain cerebral hemispheres in culture. Patterns of acetylcholine phosphocholine, and choline phosphoglycerides labeling from (methyl-14C)choline. J Biol Chem. 1976 Mar 10;251(5):1392–1397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arduini A, Peschechera A, Dottori S, Sciarroni AF, Serafini F, Calvani M. High performance liquid chromatography of long-chain acylcarnitine and phospholipids in fatty acid turnover studies. J Lipid Res. 1996 Mar;37(3):684–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton JG, Comai K. Separation of neutral lipids and free fatty acids by highperformance liquid chromatography using low wavelength ultraviolet detection. J Lipid Res. 1984 Oct;25(10):1142–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kupke IR, Zeugner S. Quantitative high-performance thin-layer chromatography of lipids in plasma and liver homogenates after direct application of 0.5-microliter samples to the silica-gel layer. J Chromatogr. 1978 Sep 1;146(2):261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81892-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bansal A, Shuyan W, Hara T, Harris RA, Degrado TR. Biodisposition and metabolism of [(18)F]fluorocholine in 9L glioma cells and 9L glioma-bearing fisher rats. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008 Jun;35(6):1192–1203. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0736-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishidate K, Nakazawa Y. Choline/ethanolamine kinase from rat kidney. Methods Enzymol. 1992;209:121–134. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)09016-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu D, Hutchinson OC, Osman S, Price P, Workman P, Aboagye EO. Use of radiolabelled choline as a pharmacodynamic marker for the signal transduction inhibitor geldanamycin. British journal of cancer. 2002 Sep 23;87(7):783–789. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Dresser MJ, Gray AT, Yost SC, Terashita S, Giacomini KM. Cloning and functional expression of a human liver organic cation transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1997 Jun;51(6):913–921. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorboulev V, Ulzheimer JC, Akhoundova A, et al. Cloning and characterization of two human polyspecific organic cation transporters. DNA Cell Biol. 1997 Jul;16(7):871–881. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negendank W. Studies of human tumors by MRS: a review. NMR Biomed. 1992 Sep-Oct;5(5):303–324. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preul MC, Caramanos Z, Collins DL, et al. Accurate, noninvasive diagnosis of human brain tumors by using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Nat Med. 1996 Mar;2(3):323– 325. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cecil KM, Schnall MD, Siegelman ES, Lenkinski RE. The evaluation of human breast lesions with magnetic resonance imaging and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001 Jul;68(1):45–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1017911211090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeung DK, Cheung HS, Tse GM. Human breast lesions: characterization with contrastenhanced in vivo proton MR spectroscopy--initial results. Radiology. 2001 Jul;220(1):40– 46. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jl0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roebuck JR, Cecil KM, Schnall MD, Lenkinski RE. Human breast lesions: characterization with proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 1998 Oct;209(1):269–275. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kvistad KA, Bakken IJ, Gribbestad IS, et al. Characterization of neoplastic and normal human breast tissues with in vivo (1)H MR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999 Aug;10(2):159–164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199908)10:2<159::aid-jmri8>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jagannathan NR, Kumar M, Seenu V, et al. Evaluation of total choline from in-vivo volume localized proton MR spectroscopy and its response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001 Apr 20;84(8):1016– 1022. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernandez-Alcoceba R, Fernandez F, Lacal JC. In vivo antitumor activity of choline kinase inhibitors: a novel target for anticancer drug discovery. Cancer Res. 1999 Jul 1;59(13):3112–3118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lockman PR, Allen DD. The transport of choline. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2002 Aug;28(7):749–771. doi: 10.1081/ddc-120005622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porter RK, Scott JM, Brand MD. Choline transport into rat liver mitochondria. Characterization and kinetics of a specific transporter. J Biol Chem. 1992 Jul 25;267(21):14637–14646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Ridder JJ. The uptake of choline by rat liver mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976 Nov 9;449(2):236–244. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(76)90136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyler DD. Transport and oxidation of choline by liver mitochondria. Biochem J. 1977 Sep 15;166(3):571–581. doi: 10.1042/bj1660571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pelech SL, Pritchard PH, Vance DE. Prolonged effects of cyclic AMP analogues of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982 Nov 12;713(2):260–269. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(82)90243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pritchard PH, Vance DE. Choline metabolism and phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in cultured rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1981 Apr 15;196(1):261–267. doi: 10.1042/bj1960261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeisel SH, Story DL, Wurtman RJ, Brunengraber H. Uptake of free choline by isolated perfused rat liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Aug;77(8):4417–4419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nuwayhid SJ, Vega M, Walden PD, Monaco ME. Regulation of de novo phosphatidylinositol synthesis. Journal of lipid research. 2006 Jul;47(7):1449–1456. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600077-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelech SL, Vance DE. Regulation of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984 Jun 25;779(2):217–251. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(84)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plagemann PG. Choline metabolism and membrane formation in rat hepatoma cells grown in suspension culture. 3. Choline transport and uptake by simple diffusion and lack of direct exchange with phosphatidylcholine. Journal of lipid research. 1971 Nov;12(6):715–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeGrado TR, Coleman RE, Wang S, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 18F-labeled choline as an oncologic tracer for positron emission tomography: initial findings in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001 Jan 1;61(1):110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abel S, Smuts CM, de Villiers C, Gelderblom WC. Changes in essential fatty acid patterns associated with normal liver regeneration and the progression of hepatocyte nodules in rat hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2001 May;22(5):795–804. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ho CL, Yu SC, Yeung DW. 11C-acetate PET imaging in hepatocellular carcinoma and other liver masses. J Nucl Med. 2003 Feb;44(2):213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]