Abstract

The maturation of neocortical regions mediating social cognition during adolescence and young adulthood in relatives of schizophrenia patients may be vulnerable to heritable alterations of neurodevelopment. Prodromal psychotic symptoms, commonly emerging during this period in relatives, have been hypothesized to result from alterations in brain regions mediating social cognition. We hypothesized these regions to show longitudinal alterations and these alterations to predict prodromal symptoms in adolescent and young adult relatives of schizophrenia patients. 27 Healthy controls and 23 relatives were assessed at baseline and one year follow-up using scale of prodromal symptoms and gray matter volumes of hypothesized regions from T1-MRI images. Regional volumes showing deficits on ANCOVA and repeated-measures-ANCOVAs (controlling intra cranial volume, age and gender) were correlated with prodromal symptoms. At baseline, bilateral amygdalae, bilateral pars triangulares, left lateral orbitofrontal, right frontal pole, angular and supramarginal gyrii were smaller in relatives compared to controls. Relatives declined but controls increased or remained stable on bilateral lateral orbitofrontal, left rostral anterior cingulate, left medial prefrontal, right inferior frontal gyrus and left temporal pole volumes at follow-up relative to baseline. Smaller volumes predicted greater severity of prodromal symptoms at both cross-sectional assessments. Longitudinally, smaller baseline volumes predicted greater prodromal symptoms at follow-up; greater longitudinal decreases in volumes predicted worsening (increase) of prodromal symptoms over time. These preliminary findings suggest that abnormal longitudinal gray matter loss may occur in regions mediating social cognition and may convey risk for prodromal symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood in individuals with a familial diathesis for schizophrenia.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia patients may share social cognitive deficits with their relatives at familial familial risk (Eack et al., 2009). Social cognition involves complex cognitive processes including affect perception, emotion regulation, social co-operation, empathy, social cue recognition and theory-of-mind processes (Abe et al., 2007; Adolphs, 2001; Dunbar, 2009; Hall et al., 2004; Meltzoff and Decety, 2003; Platek et al., 2009; Rilling et al., 2002; Schilbach et al., 2008). These highly evolved faculties may depend on the evolutionarily recent neocortices (Adolphs, 2001; Dunbar, 2009) including the superior temporal sulcus, temporo parietal junction (supramarginal and angular gyrii of the inferior parietal lobule), rostral anterior cingulate cortex, temporal pole, frontal pole, inferior frontal gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex, medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex as well as on subcortical regions such as the amygdalae. The amygdalae together with the medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex and rostral anterior cingulate may be involved in affect perception, emotion regulation and social co-operation (Adolphs, 2001; Hall et al., 2004; Meltzoff and Decety, 2003; Rilling et al., 2002). The inferior frontal gyrus, temporo parietal junction, frontal and temporal poles and the medial prefrontal cortices may predominantly mediate theory-of-mind processes, empathy, processing of social gestures and cues and self reflection (Adolphs, 2001; Brune et al., 2008; Calarge et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2009; D’Argembeau et al., 2007; Farrow et al., 2001; Hall et al., 2004; Meltzoff and Decety, 2003; Montgomery and Haxby, 2008; Ortigue et al., 2009; Platek et al., 2006; Rilling et al., 2002; Saxe, 2006; Uddin et al., 2005; Van Overwalle, 2009; Yamada et al., 2009). There may however be considerable functional overlap between these regions (Abe et al., 2007; Platek et al., 2009; Schilbach et al., 2008).

Neocortical maturation, although beginning in childhood, continues during adolescence and young adulthood (Choudhury et al., 2006; Paus, 2005; Rubia et al., 2006; Yurgelun-Todd, 2007). Increasing neocortical regulation of the subcortical regions may allow social cognitive faculties to emerge during adolescence and young adulthood (Blakemore, 2008a; Blakemore, 2008b; Casey et al., 2008; Choudhury et al., 2006; Paus, 2005; Rubia et al., 2006; Sebastian et al., 2008; Sebastian et al., 2009; Yurgelun-Todd, 2007). Neurodevelopmental alterations during late adolescence and early adulthood including aberrant neuronal and/or synaptic neocortical pruning implicated in schizophrenia (Keshavan et al., 1994; Pantelis et al., 2003a), may interfere with the development of brain regions mediating social cognition, occurring in the same temporal ‘window’. Social cognitive deficits in adolescent and young adult relatives at-risk for schizophrenia (Cannon et al., 2008; Chung et al., 2008; Eack et al., 2009; Pantelis et al., 2003a) may be ‘trait-related’ core features (Hawkins et al., 2008) and hence reflect altered neurodevelopmental maturation of brain regions related to social cognition.

The prodromal phase, which frequently precedes the onset of psychosis in those with familial diathesis for the illness, has recently acquired importance as a potential ‘window’ for strategies to prevent psychosis(McGorry et al., 2003). Sub-threshold psychotic (prodromal) symptoms may emerge during adolescence and young adulthood in relatives of schizophrenia patients (Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003). Our previous data suggest that impaired social cognition is correlated with prodromal symptomatology in adolescent relatives of patients(Eack et al., 2009). Studies show compromised social functioning (Niendam et al., 2007), affect perception deficits (Addington et al., 2008), theory-of-mind deficits (Chung et al., 2008), social impairment, social anhedonia, social withdrawal (Cannon et al., 2008; Chung et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2006; Moller and Husby, 2000) an altered sense of self (Nelson et al., 2009) and social maladjustment (Hoffman, 2007; Hoffman, 2008) in young relatives showing prodromal symptoms(Miller et al., 1999). Studies have also shown progressive alterations in some brain regions related to social cognition during the prodromal phase(Pantelis et al., 2007; Pantelis et al., 2005; Pantelis et al., 2003b). These findings imply a possible relation between alterations of brain regions mediating social cognition and prodromal symptoms in young high-risk (HR) relatives.

We longitudinally assessed gray matter volumes of regions implicated in social cognition by previous studies (Brune et al., 2008; Calarge et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2009; Farrow et al., 2001; Fujiwara et al., 2007; Margulies et al., 2007; Moll et al., 2001; Montgomery and Haxby, 2008; Platek et al., 2006; Vollm et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2008; Yamada et al., 2009), and prodromal symptoms in non-psychotic adolescent and young adult relatives of schizophrenia patients. We hypothesized that HR relatives would show exaggerated gray matter loss in brain regions mediating social cognition during follow-up. We also hypothesized that cross-sectional and longitudinal structural alterations would predict a greater severity of, and worsening of prodromal symptoms over time.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The longitudinal study was conducted at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh and was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Participants were 23 adolescent and young non-psychotic adult HR relatives [19 offspring (first-degree relatives) and 4 second-degree relatives] of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder patients and 27 healthy controls (HC). HR subjects were recruited by approaching patients and through advertisements. HC were recruited from the same community through advertisements. Clinical assessments of HR and HC subjects at baseline and follow-up and the diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in the index relatives (e.g. parents or sibling) used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnoses (SCID) (First et al., 1995) and all available clinical data; the diagnoses were confirmed by consensus meetings led by senior diagnosticians (MK and DM).HR and HC participants with IQ below 80, lifetime evidence of a psychotic disorder, exposure to antipsychotic medication, neurological or medical condition were excluded. HC subjects were included after confirming that they had no first or second-degree relative with a psychotic disorder and were excluded if they were diagnosed with an Axis-I disorder on the SCID at either assessment time-point. At baseline, HR subjects were diagnosed with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (five subjects), Major Depressive Disorder [single episode, mild] (one subject), Major Depressive Disorder in full remission (one subject), Panic Disorder without agoraphobia (one subject) and cannabis dependence (one subject) on the SCID. At follow-up, HR subjects were diagnosed with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (five subjects), Major Depressive Disorder (one subject), Major Depressive Disorder in full remission (two subjects), Panic Disorder without agoraphobia (two subjects) and cannabis dependence (one subject) on the SCID. No HR or HC subjects were diagnosed with Axis-II (personality) disorders or learning disorders on the SCID. All participants signed informed consent after the study was fully explained to them. For participants <18 years of age, the consent was provided by the parent or guardian, and the subjects provided informed assent.

2.2 Clinical assessments

Relatives (HR) were assessed at baseline and one year follow-up time-points using the SIPS (Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes) by an experienced and reliable rater(Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003). Scores obtained on the positive (PS), negative (NS), disorganization (DS) and general (GS) symptom sub-scales of the well validated scale of prodromal symptoms (SOPS), administered as a part of the SIPS, were used for analyses. The reader is referred to (Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003) for a detailed description of the questions included in each of the subscales included in the SOPS. The score for social anhedonia item (abbreviated as SA), which is obtained as a subscore (N1) of the total negative symptom score (NS) (Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003) was also used for analyses as an index of social cognition. Both HC and HR subjects were examined using the Global assessment of functioning scale (GAF) at both time-points (Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003) and were assessed for IQ at baseline. Classification of HR subjects into prodromal syndromes based on the COPS (Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes) was performed (Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003).

2.3 Imaging

MRI scans were obtained on controls and relatives using a GE 1.5T whole body scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) at baseline and after a one year follow-up. The scans were three-dimension spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR), acquired in a steady-state pulse sequence (124 coronal slices, 1.5 mm slice-thickness, TE=5 msec, TR=25 msec, acquisition matrix=256×192, FOV=24 cm, flip angle 40°) (see our earlier publication for details(Gilbert et al., 2001)). Images with significant motion artifacts were not included in the study. T1-images were processed using FreeSurfer, a validated(Tae et al., 2008), automated method, previously used to study the brain morphology of schizophrenia patients (Kuperberg et al., 2003)and their relatives (Bhojraj et al., 2010; Bhojraj et al., 2009; Goghari et al., 2007). FreeSurfer has three automated stages(Fischl et al., 2002), each followed by manual image editing by an experienced brain morphometrician (AF), blind to subject identity, clinical information and timepoint of the scans. The first stage performs skull stripping and motion correction, while the second performs gray white segmentation (Fischl et al., 2002). The third automatically parcellates (Desikan et al., 2006) the brain into 32 neuroanatomical regions based on gyral and sulcal anatomical landmarks and measures their gray-matter volume. Of the 32 regions parcellated by FreeSurfer, we selectively assessed those mediating social cognition and hence a priori hypothesized to be affected in HR subjects [the supramarginal and angular gyrii of the inferior parietal lobule, rostral anterior cingulate cortex, temporal pole, frontal pole, inferior frontal gyrus, medial prefrontal cortex, medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortices]. The superior temporal sulcus, albeit hypothesized to be altered in HR, could not be assessed as it is not separately parcellated by FreeSurfer (Desikan et al., 2006). The same scan acquisition method, image analyses methods and morphometrician were used for all subjects at both baseline and follow-up assessments. The clinical raters were blind to imaging data and image processing were conducted blind to clinical data and time of assessment.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Gray matter-volumes for the a priori hypothesized regions were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk’s test W statistic, p>.05). Volumes for all hypothesized regions at baseline were compared between study groups (controls and relatives) using ANCOVA controlling for gender, intra cranial volume (ICV) and age. The longitudinal trajectories of volumes for all hypothesized regions were compared using repeated-measures-ANCOVA with group as between-subject factor, time (baseline/follow-up) as the within-subject factor and gender, ICV and age as covariates. As, IQ deficits in HR subjects(Eack et al., 2009), are related to structural deficits (Antonova et al., 2005; Toulopoulou et al., 2004; Zipursky et al., 1998) and may hence confound volumetric deficits in HR. Those baseline ANCOVA and repeated-measures-ANCOVA analyses showing statistically significant volumetric changes were hence repeated with IQ, gender, intra cranial volume (ICV) and age as covariates.

CS-GM, change in regional volume, as a fraction of baseline-volume [CS-GM = (Volume at follow-up – Volume at baseline)/ Volume at baseline] was computed for each study-group for all regions showing statistically significant group X time interaction effects on the repeated-measures ANCOVAs. Significant group X time interactions for regional volumes were clarified by comparing regional CS-GM of controls and relatives with the normative zero using two-tailed one-sample t-tests. Significantly negative and positive CS-GM values on the t-tests respectively suggested a volumetric decrease and increase over the follow-up period.

GAF scores at both baseline and one-year follow-up were compared across HC and HR subjects using t-tests. Change scores were computed for positive, negative, disorganization and general prodromal symptom scores (PS, NS, DS and GS) (CS-Sym), for the social anhedonia score (N1 component of the NS score) (CS-SA) and also for GAF scores (CS-GAF) by subtracting baseline scores from follow-up scores (CS-Sym = symptom-score at follow-up – symptom-score at baseline, CS-SA= SA subscore at follow-up – SA subscore at baseline and CS-GAF= GAF score at follow-up – GAF score at baseline). Positive and negative CS-Sym and CS-SA values respectively suggested increase (worsening) and decrease (improvement) of prodromal symptoms and social anhedonia over the follow-up period. CS-Sym for PS,NS, SA, DS and GS were compared to zero using one-sample t-tests. Positive and negative CS-GAF scores respectively suggested an increase (improved functioning over time) and decrease (deterioration of functioning over time) of the GAF scores over the follow-up period. CS-GAF scores were compared across HC and HR subjects. CS-Sym, CS-SA and CS-GAF were non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk’s test W statistic, p<.05) and hence were rank transformed before these tests. Absolute, instead of fractional change scores were computed for prodromal symptoms as some subjects had baseline symptom scores of zero.

The following analyses used spearman’s correlations as GAF, PS, NS, SA, DS and GS scores at baseline and follow-up and CS-Sym were non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk’s test W statistic, p<.05). Volumes of regions showing deficits on the baseline ANCOVA were correlated with GAF, PS, NS, SA, DS and GS scores at baseline and follow-up. Volumes at follow-up for regions showing longitudinal alterations on the repeated-measures ANCOVAs and/or baseline deficits on the ANCOVA were correlated with PS, NS, SA, DS and GS scores at follow-up. CS-GMs for regions showing longitudinal alterations on the repeated-measures ANCOVAs were correlated with CS-Sym (PS, NS, SA, DS and GS).

3. Results

HC did not differ from HR subjects on age [(Mean ± SD in years; HC 16.6±4.5, and HR15.4 ± 3.6), t=1.79, p= 0.1], handedness (Chi-square=0.1, p=0.7), race (Chi-square=0.33, p=0.57) and gender (controls: 42% males, offspring: 53% males, Chi-square=1.6, p=0.20) and had higher IQ than HR [(Mean ± SD for IQ scores; HC 113±9.1, and HR103 ± 12), t=3.18, p= 0.00] at baseline.

3.1 Structural deficits

At baseline, bilateral amygdalae, bilateral inferior frontal gyrii, right supramarginal gyrus, right angular gyrus and right frontal pole were smaller in HR compared to HC subjects after controlling for age, gender and ICV. Only the deficits for bilateral amygdalae and the left inferior frontal gyrus survived controlling for IQ, age, gender and ICV (see table 1, column 3). The longitudinal trajectories of the left rostral anterior cingulate, bilateral lateral orbitofrontal cortices, left medial prefrontal cortex, bilateral pars triangulares and left temporal pole volumes significantly differed across groups as seen in the group X time interaction effects after controlling for age, gender and ICV. All the above group X time interaction effects survived controlling for IQ, age, gender and ICV (see table 1, column 4). Over the follow-up, these regional volumes declined in HR subjects as suggested by the negative CS-GM t-values and increased or remained stable in controls as suggested by the positive or zero CS-GM t-values (table 1 and figure 1). Left inferior frontal gyrus volume however declined in HC subjects and remained stable in HR subjects (table 1). Group X time interaction effects for all regions except the left inferior frontal gyrus were hence driven by gray-matter loss in relatives in the context of increasing or stable gray-matter volume in controls. No alterations were noted for medial orbitofrontal, right temporo polar, right rostral anterior cingulate, right medial prefrontal, left angular gyrus, left supramarginal gyrus and left fronto polar regions.

TABLE 1.

Means and standard deviations for assessed brain regions at baseline and follow-up are provided in columns 1 and 2 for both study groups. Structural deficits at baseline (column 3) and significantly different longitudinal change (column 4) of regional volumes in relatives compared to controls are noted. The F (1,44) and p in non-italicized text are those obtained when controlling for gender, age and ICV. The F (1,43) and p values in italics represent those obtained when repeating the ANCOVA analyses controlling for gender, age, ICV and IQ. The negative CS-GM t-values in relatives (column 5) for all regions except the left inferior frontal gyrus, suggest a gray-matter loss over time. Controls increased or remained stable for all regions except the left inferior frontal gyrus on which they declined over the course of the follow-up, as suggested by the positive or zero CS-GM t-values (column 6).

| Region | Gray-matter volume at baseline | Gray-matter volume at follow- up | Effect of group at Baseline ANCOVA | Group X time effect on the Repeated- measures ANCOVA | Two-tailed t-test on regional CS-GM, HR | Two-tailed t-test on regional CS-GM, HC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Standard deviation), in cubic mm | Mean (Standard deviation), in cubic mm | F(1,44),p F(1,43),p |

F(1,44),p F(1,43),p |

t, p | t, p | |

| HR HC |

HR HC |

|||||

| R Amygdala | 1547.8 (165.2) | 1554.2 (159.0) | 5.79, 0.02 | 0.80, 0.54 | Not performed | Not performed |

| 1613.8(194.4) | 1620.1 (201.9) | 2.68, 0.10 | ||||

| L Amygdala | 1511.9 (141.1) | 1528.8 (150.9) | 6.94, 0.01 | 0.45, 0.86 | Not performed | Not performed |

| 1588.8(182.9) | 1601.4 (190.1) | 3.29, 0.07 | ||||

| R Lateral Orbitofrontal Cortex | 11423.6(1685.3) | 10901.0(1662) | 1.99, 0.20 | 3.54, 0.06 | −2.9, 0.00 | 0.93, 0.40 |

| 11460.2(1326.1) | 11451.8(1468.3) | 4.16, 0.04 | ||||

| L Lateral Orbitofrontal Cortex | 10865.9(1612.3) | 10405.6(1663.6) | 2.19, 0.14 | 3.96, 0.05, | −3, 0.00 | 1.2, 0.23 |

| 11254.3(1518.9) | 11228.7(1593.1) | 3.02, 0.08 | ||||

| R Frontal pole | 1093.5(207.7) | 1054.9(299.3) | 3.32, 0.07 | 1.21, 0.39 | Not performed | Not performed |

| 1151.5(231.8) | 1090.0(286.7) | 1.51, 0.21 | ||||

| L Medial Prefrontal Cortex | 26001.6(3265.1) | 23916.6(2761.9) | 1.83, 0.24 | 5.84, 0.02, | −4, 0.00 | −1.5, 0.16 |

| 26472.2(3230.16) | 25185.3 (3077.8) | 3.79, 0.05 | ||||

| R Inferior frontal gyus | 4689.3(1182.9) | 4473.9(1122.5) | 4.23, 0.04 | 6.02, 0.01 | −1.4, .16 | 2.3, 0.02 |

| 5195.6(1208.4) | 5516.8(1193.1) | 1.16, 0.29 | 6.65, 0.01 | |||

| L Inferior frontal gyrus | 4497.8(1084.7) | 4466.5(1046.5) | 5.52, 0.02, 7.04, 0.01 | 5.89, 0.01, 4.59, 0.05 | 0.5, 0.73 | −3, 0.00 |

| 5526.5(1351.4) | 4958.6(804.8) | |||||

| L Temporal Pole | 2788.0(432.3) | 2584.0(480.7) | 1.78,0.30 | 6.63, 0.01 | −2, 0.05 | 1.8, 0.07 |

| 2654.4(558.2) | 2855.4(435.9) | 5.79, 0.02 | ||||

| L Rostral Anterior Cingulate | 2480.5(520.6) | 2333.4(547.9) | 0.98, 0.65 | 4.48, 0.04, | −2, 0.04 | 1.4, 0.19 |

| 2486.9(504.4) | 2519.5 (464.8) | 2.83, 0.09 | ||||

| R Supramarginal | 10409.8(1827.8) | 10087.7(1694.0) | 5.38, 0.02, 1.19, 0.17 | 0.87, 0.55 | Not performed | Not performed |

| 10858.9(1600.8) | 10584.5(1802.1) | |||||

| R Angular | 17324.3(2788.3) | 16846.1(2739.9) | 5.49, 0.02, 1.34, 0.16 | 1.02, 0.33 | Not performed | Not performed |

| 18110.4(2639.1) | 17877.0(2494.3) |

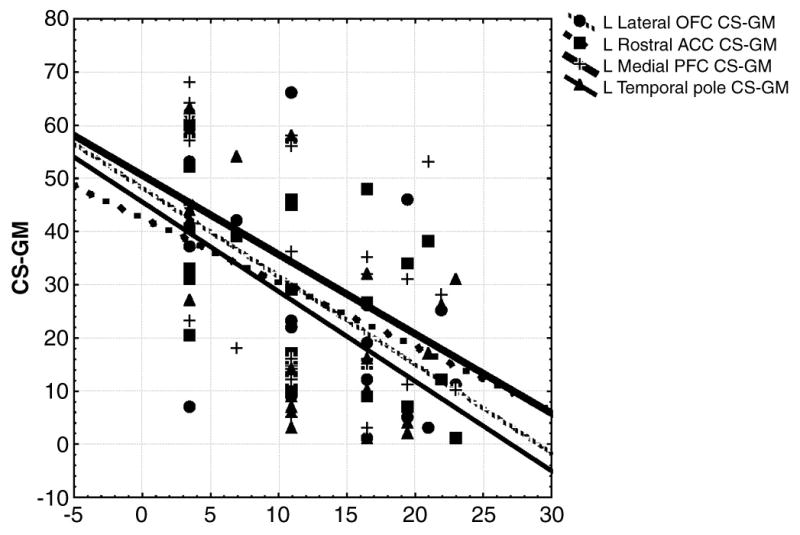

FIGURE 1.

CS-GM (in mm3) are represented on the Y-axis while CS-Sym (in Positive Symptom score on the SOPS) are plotted. Data were rank transformed as they were non-normally distributed

3.2 Prodromal symptoms and Global assessment of functioning scores

Two HR subjects met criteria for prodromal syndromes defined in COPS (Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes) (Miller et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2003) at baseline and four subjects met criteria at follow-up. At baseline, one HR subject was diagnosed with the Brief Intermittent Psychotic Symptom syndrome (BIPS) and another met criteria for the Attenuated Positive Symptom syndrome (APS). At follow-up, in addition to these subjects, two more subjects were diagnosed with APS. HR subjects had significantly lower GAF scores at both baseline and follow-up assessments compared to HC as seen in the across group comparisons (see table 2). Both HC and HR subjects improved on GAF scores equally over the course of the study as reflected in the CS-GAF being non-significantly different than zero on the one sample t-tests (see table 2). Positive, negative, disorganization and general prodromal symptoms and social anhedonia (SA) worsened in HR subjects over time as reflected in the CS-Sym and CS-SA scores being significantly more than zero on the one sample t-tests (see table 3).

TABLE 2.

Mean and standard deviation for GAF and CS-GAF scores (before rank transformation) and t and p (two-tailed) values for across group comparisons of GAF scores and CS-GAF scores, computed after rank transformation.

| GAF SCORES | CS-GAF= FOLLOW-UP – BASELINE GAF SCORE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | FOLLOW-UP | ||

| HC SUBJECTS (MEAN, S.D) | 87.93, 4.7 | 88.72, 4.6 | 2.04, 3.9 |

| HR SUBJECTS (MEAN, S.D) | 73.95, 14.2 | 74.71, 14.7 | 0.85, 8.3 |

| t, p (two-tailed) FOR ACROSS GROUP COMPARISONS | 5.8, 0.000 | 4.9, 0.000 | 0.11, 0.91 |

TABLE 3.

Means and standard deviations for PS, NS, SA, DS, GS scores (before rank transformation) obtained from the SOPS are mentioned. Change scores [CS-Sym and CS-SA scores (before rank transformation)] and t and p (two-tailed) values for the one-sample t-tests performed on CS-Sym scores and CS-SA are also noted. The t-tests indicate that CS-Sym and CS-SA significantly differ from zero, reflecting a worsening of prodromal symptoms and social anhedonia over time.

| PRODROMAL SYMPTOM SCORES (MEAN, S.D) | ONE SAMPLE T TESTS ON CHANGE SCORES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | FOLLOW-UP | CHANGE SCORES (CS-Sym and CS-SA) | t, p (two-tailed) | |

| Positive symptoms (PS) | 1.23, 3.44 | 2.72, 6.11 | 2.50, 4.61 | 2.15, 0.04 |

| Negative symptoms (NS) | 1.43, 2.10 | 3.90, 4.09 | 2.31, 4.33 | 2.13, 0.04 |

| Social anhedonia subscore (SA) of the NS score | 0.21, 0.67 | 0.86, 1.14 | 0.65, 0.93 | 3.34, 0.00 |

| Disorganization symptoms (DS) | 0.94, 1.34 | 1.68, 2.45 | 1.31, 2.62 | 1.99, 0.06 |

| General symptoms (GS) | 1.11, 2.02 | 2.36, 3.24 | 1.87, 3.42 | 2.19, 0.04 |

3.3 Correlation of baseline volumes with baseline and follow-up GAF, SAand prodromal symptom scores

Only regions showing deficits in HR subjects on the baseline ANCOVA tests were selected for these analyses. The amygdalae, inferior frontal gyrii, right supramarginal gyrus, right angular gyrus and right frontal pole showed deficits at baseline and were hence selected. Smaller volumes of the right angular gyrus, right supramarginal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrii correlated with higher general symptoms at baseline. Smaller left amygdalar, left inferior frontal gyrus and right angular gyrus volumes at baseline predicted greater negative symptoms at follow-up (see table 4). Smaller right angular gyrus (R=−0.42, p=0.05) and left amygdala (R=−0.41, p=0.05) volume at baseline predicted a higher social anhedonia subscore (SA) at follow-up. Smaller left inferior frontal gyrus volumes at baseline predicted higher general symptoms at follow-up (R=−0.46, p=.06). No correlations were noted for baseline or follow-up GAF scores with baseline volumes for the selected regions.

TABLE 4. Correlation matrix.

Spearman correlations were performed between baseline volumes for regions showing baseline deficits on the preceding ANCOVAs and SOPS symptom sub-scale, GAF and SA scores. Although scores on all 4 sub-scales were correlated, only significant correlations are tabulated.

| Region showing baseline deficits | Spearman Correlations between regional volumes and symptoms, two-tailed p | |

|---|---|---|

| Volumes at baseline | General symptoms at baseline | Negative symptoms at follow-up |

| Right Angular | −0.43, 0.08 | −0.44, 0.05 |

| Right supramarginal | −0.47, 0.07 | −0.09, 0.32 |

| Right inferior frontal | −0.55, 0.03 | −0.12, 0.20 |

| Left inferior frontal | −0.62, 0.00 | −0.46, 0.08 |

| Left amygdala | −0.11, 0.19 | −0.51, 0.03 |

3.4 Correlation of follow-up volumes with GAF, SAand prodromal symptom scores at follow-up

Volumes at follow-up for regions showing longitudinal alterations and/or baseline deficits were correlated with PS, NS, SA, DS and GS scores at follow-up. Regions showing deficits in HR on baseline ANCOVAs and/or on the repeated measures ANCOVAs were hence selected for this analysis. At follow-up, smaller left temporal pole volumes predicted higher positive symptoms (R=−0.5, p=.02). Smaller right inferior frontal gyrus (R=−0.5, p=.04) and right lateral orbitofrontal (R=−0.4, p=.05) volumes predicted higher negative symptoms. Smaller right inferior frontal gyrus volume predicted a higher SA subscore (R=−0.4, p=.05). Smaller left rostral anterior cingulate (R=−0.3, p=.09) and right inferior frontal gyrus (R=−0.4, p=0.04) volumes predicted higher general symptoms. A bigger left medial prefrontal cortex predicted higher GAF scores (R=0.4, p=0.05).

3.5 Correlation of change in volumes and change in GAF, SAand prodromal symptom scores over time

Only regions showing gray-matter decline on the preceding CS-GM t-tests were included in the following analyses. Greater longitudinal decreases in regional volumes (more negative CS-GM) predicted greater longitudinal increases (more positive CS-Sym) (worsening) in prodromal symptoms (see figure 1 and table 3). More negative left temporal pole, left medial prefrontal, left lateral orbitofrontal and left rostral anterior cingulate CS-GMs predicted more positive CS-Sym for positive symptoms. More negative left rostral anterior cingulate and left medial prefrontal CS-GM predicted a more positive disorganization CS-Sym. More negative left rostral anterior cingulate (R=− .30, p=.09) CS-GM predicted more positive general symptom CS-Sym. No significant correlations were noted between CS-SA scores and CS-GAF scores and regional volume change (CS-GM) over time.

Although we restricted volumetric analyses to specific a priori hypothesized regions, and correlation analyses to only structurally altered regions, none of the volumetric deficits or volume-symptom correlations noted above survived correction for multiple comparisons using an alpha of 0.05.

4. Discussion

HR Relatives showed baseline deficits mainly for the amygdalae and parietal regions and abnormal longitudinal gray matter loss in the anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal, prefrontal, fronto polar and temporo polar regions. While the evolutionarily recent orbitofrontal, prefrontal, fronto polar, temporo polar and anterior cingulate regions may develop during adolescence and young adulthood, parietal cortical and subcortical structures possibly mature earlier, during childhood (Gogtay et al., 2004; Luna et al., 2001; Paus, 2005; Rubia et al., 2006; Sowell et al., 1999a; Sowell et al., 1999b). Abnormal longitudinal gray matter volume loss of left rostral anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral lateral orbitofrontal, left medial prefrontal, right inferior frontal gyrus and left temporal pole gray matter in relatives but not in controls may reflect a disruption of normal neurodevelopmental maturation during adolescence and young adulthood, perhaps by exaggerated peri-adolescent pruning, implicated in schizophrenia (Cannon, 2008; DeLisi, 1997; Gogtay, 2008; Keshavan et al., 1994; Rapoport et al., 2005). A premature onset of pruning during childhood and/or early defcits in brain development during gestation and childhood, also posited to occur in schizophrenia (Gogtay, 2008; Keshavan et al., 1994; Rapoport et al., 2005), may presumptively explain baseline parietal cortical and amygdalar deficits.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of longitudinal structural alterations in relation to prodromal symptoms in young non-psychotic relatives of schizophrenia patients. Previous studies in HR relatives have shown gray-matter decline in orbitofrontal, medial temporal and anterior cingulate cortices during the transition to schizophrenia (Fornito et al., 2008; Pantelis et al., 2007; Pantelis et al., 2005; Pantelis et al., 2003b; Sun et al., 2009) and a neocortical gray matter loss in the early phases of schizophrenia (Farrow et al., 2005; Nakamura et al., 2007; Whitford et al., 2005; Whitford et al., 2009; Whitford et al., 2006). Our findings in non-psychotic relatives tentatively support the view that these declining trajectories during the emergent and early phases of schizophrenia may predate the transition to psychosis (Farrow et al., 2005). Further follow-up of our sample may reveal if this decline predicts the later emergence of schizophrenia or related psychoses. Genetically predisposed relatives without prodromal or psychotic symptoms may show subtle amygdalar, cingulate, frontal and temporal cortical volume (Job et al., 2005; Job et al., 2003; Keshavan et al., 2002; Lawrie et al., 2008) and cortical thickness (Goldman et al., 2009) deficits possibly suggesting that progressive structural changes of some regions involved in social cognition may precede the emergence of prodromal symptoms in at-risk relatives.

Although the correlations between gray matter deficits and prodromal symptoms, did not survive correction for multiple comparisons, the alpha error-rate was contained by restricting the correlation analyses to those a priori assessed regions showing structural alterations. Our observations must therefore be considered preliminary. HR subjects had lower GAF scores compared to HC subjects at baseline and follow-up assessments, improving equally to HC subjects on GAF scores over time. Prodromal symptoms and social anhedonia in HR subjects worsened over the course of the study. Smaller volumes predicted greater severity of prodromal symptoms at both cross-sectional assessments. Longitudinally, smaller baseline volumes predicted greater prodromal symptoms at follow-up and greater longitudinal volumetric decreases predicted worsening (increase) of prodromal symptoms over time. A ‘social deafferentation hypothesis’ has proposed that aberrant neuroplasticity within brain regions mediating social cognition may result from social maladjustment and withdrawal (Hoffman, 2007; Hoffman, 2008). These plastic changes have been thought to contribute to sub-threshold psychotic symptoms during the prodrome (Hoffman, 2007; Hoffman, 2008). Conversely, a primary genetic diathesis manifesting as exaggerated pruning (DeLisi, 1997; Keshavan et al., 1994; Rapoport et al., 2005) (gray matter-loss(Gogtay, 2008)) of the brain regions mediating social cognition may cause social-cognitive deficits in relatives(Chung et al., 2008) which may contribute to prodromal symptoms (Cannon et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2006; Moller and Husby, 2000; Niendam et al., 2007).

Although we found abnormal gray matter loss may occur in regions mediating social cognition in adolescent and young adult non-psychotic relatives with a familial diathesis for schizophrenia, our study is limited by assessment of both first and second degree relatives, by relatively low sample size and by lack of follow-up beyond one-year in an adequate number of subjects. As none of the relatives transitioned to psychosis, it is unclear if the reported longitudinal alterations predict schizophrenia. Although the gray matter decline may explain the emergence of prodromal psychotic symptoms during late adolescence and early adulthood in relatives, it is unclear if it heralds schizophrenia, given that prodromal symptoms are relatively poor predictors of psychosis (McGorry et al., 2000; McGorry et al., 1995). Our findings support previous evidence of progressive gray matter loss in young, at-risk relatives showing prodromal symptoms (Fornito et al., 2008; Pantelis et al., 2007; Pantelis et al., 2005; Pantelis et al., 2003b; Sun et al., 2009) and suggest a relation between these structural changes, prodromal psychopathology and progressive worsening of prodromal symptoms over time. These are however limited by a relatively low sample size, do not survive controlling for multiple comparisons and hence must be considered as preliminary.

TABLE 5. Correlation matrix.

Spearman correlations were performed between CS-GM for regions showing altered longitudinal trajectories on the preceding ANCOVAs and CS-Sym for SOPS symptom sub-scale, GAF and SA scores. Although CS-Sym for scores on all 4 sub-scales were correlated, only significant correlations are tabulated.

| Regions showing an altered longitudinal trajectory | Spearman Correlations between CS-GM and CS-Sym, two-tailed p | |

|---|---|---|

| CS-GM of selected regions | CS-Sym for positive symptoms | CS-Sym for disorganization symptoms |

| Left temporal pole | −0.63, 0.00 | −0.03, 0.41 |

| Left medial prefrontal | −0.56, 0.01 | −0.57, 0.02 |

| Left lateral orbitofrontal | −0.51, 0.01 | −0.12, 0.19 |

| Left rostral anterior cingulate | −0.50, 0.01 | −0.47, 0.05 |

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

National Institute of Mental Health (MH 64023 and 01180 to MK); National Alliance for Research on Schizophreniaand Depression (Independent Investigator award to MK); NationalAlliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and GeneralClinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01 RR00056 to MK).

We thank Vaibhav Diwadkar and Diana Mermon, for their helpwith various aspects of this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest Statement

This research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abe N, Suzuki M, Mori E, Itoh M, Fujii T. Deceiving others: distinct neural responses of the prefrontal cortex and amygdala in simple fabrication and deception with social interactions. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:287–95. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Penn D, Woods SW, Addington D, Perkins DO. Social functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;99:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.001. S0920-9964(07)00454-9 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. The neurobiology of social cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:231–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00202-6. S0959-4388(00)00202-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova E, Kumari V, Morris R, Halari R, Anilkumar A, Mehrotra R, Sharma T. The relationship of structural alterations to cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a voxel-based morphometry study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:457–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.036. S0006-3223(05)00497-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhojraj TS, Prasad KM, Eack SM, Francis AN, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS. Do inter-regional gray-matter volumetric correlations reflect altered functional connectivity in high-risk offspring of schizophrenia patients? Schizophr Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.019. S0920-9964(10)00057-5 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhojraj TS, Francis AN, Rajarethinam R, Eack S, Kulkarni S, Prasad KM, Montrose DM, Dworakowski D, Diwadkar V, Keshavan MS. Verbal fluency deficits and altered lateralization of language brain areas in individuals genetically predisposed to schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.033. S0920-9964(09)00477-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ. Development of the social brain during adolescence. Q J Exp Psychol (Colchester) 2008a;61:40–9. doi: 10.1080/17470210701508715. 787077281 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ. The social brain in adolescence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008b;9:267–77. doi: 10.1038/nrn2353. nrn2353 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune M, Lissek S, Fuchs N, Witthaus H, Peters S, Nicolas V, Juckel G, Tegenthoff M. An fMRI study of theory of mind in schizophrenic patients with “passivity” symptoms. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1992–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.023. S0028-3932(08)00054-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarge C, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS. Visualizing how one brain understands another: a PET study of theory of mind. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1954–64. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD. Neurodevelopment and the transition from schizophrenia prodrome to schizophrenia: research imperatives. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:737–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.027. S0006-3223(08)00960-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, Seidman LJ, Perkins D, Tsuang M, McGlashan T, Heinssen R. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. 65/1/28 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010. 1124/1/111 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Chou KH, Decety J, Chen IY, Hung D, Tzeng OJ, Lin CP. Sex differences in the neuroanatomy of human mirror-neuron system: a voxel-based morphometric investigation. Neuroscience. 2009;158:713–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.026. S0306-4522(08)01548-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury S, Blakemore SJ, Charman T. Social cognitive development during adolescence. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2006;1:165–174. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YS, Kang DH, Shin NY, Yoo SY, Kwon JS. Deficit of theory of mind in individuals at ultra-high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;99:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.012. S0920-9964(07)00527-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Leung WW, Saperstein AM, Blanchard JJ. Neuropsychological functioning and social anhedonia: results from a community high-risk study. Schizophr Res. 2006;85:132–41. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.044. S0920-9964(06)00168-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau A, Ruby P, Collette F, Degueldre C, Balteau E, Luxen A, Maquet P, Salmon E. Distinct regions of the medial prefrontal cortex are associated with self-referential processing and perspective taking. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:935–44. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE. Is schizophrenia a lifetime disorder of brain plasticity, growth and aging? Schizophr Res. 1997;23:119–29. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(96)00079-5. S0920-9964(96)00079-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. S1053-8119(06)00043-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar RI. The social brain hypothesis and its implications for social evolution. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:562–72. doi: 10.1080/03014460902960289. 912879712 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Mermon DE, Montrose DM, Miewald J, Gur RE, Gur RC, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS. Social Cognition Deficits Among Individuals at Familial High Risk for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp026. sbp026 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow TF, Whitford TJ, Williams LM, Gomes L, Harris AW. Diagnosis-related regional gray matter loss over two years in first episode schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:713–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.033. S0006-3223(05)00494-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow TF, Zheng Y, Wilkinson ID, Spence SA, Deakin JF, Tarrier N, Griffiths PD, Woodruff PW. Investigating the functional anatomy of empathy and forgiveness. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2433–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, van der Kouwe A, Killiany R, Kennedy D, Klaveness S, Montillo A, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. S089662730200569X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito A, Yung AR, Wood SJ, Phillips LJ, Nelson B, Cotton S, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Pantelis C, Yucel M. Anatomic abnormalities of the anterior cingulate cortex before psychosis onset: an MRI study of ultra-high-risk individuals. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:758–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.032. S0006-3223(08)00698-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag CM, Luders E, Hulst HE, Narr KL, Thompson PM, Toga AW, Krick C, Konrad C. Total brain volume and corpus callosum size in medication-naive adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:316–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.011. S0006-3223(09)00360-6 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Hirao K, Namiki C, Yamada M, Shimizu M, Fukuyama H, Hayashi T, Murai T. Anterior cingulate pathology and social cognition in schizophrenia: a study of gray matter, white matter and sulcal morphometry. Neuroimage. 2007;36:1236–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.068. S1053-8119(07)00276-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert AR, Rosenberg DR, Harenski K, Spencer S, Sweeney JA, Keshavan MS. Thalamic volumes in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:618–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goghari VM, Rehm K, Carter CS, MacDonald AW., 3rd Regionally specific cortical thinning and gray matter abnormalities in the healthy relatives of schizophrenia patients. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:415–24. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj158. bhj158 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N. Cortical brain development in schizophrenia: insights from neuroimaging studies in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:30–6. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm103. sbm103 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, 3rd, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8174–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. 0402680101 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AL, Pezawas L, Mattay VS, Fischl B, Verchinski BA, Chen Q, Weinberger DR, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Widespread reductions of cortical thickness in schizophrenia and spectrum disorders and evidence of heritability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:467–77. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.24. 66/5/467 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Harris JM, Sprengelmeyer R, Sprengelmeyer A, Young AW, Santos IM, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. Social cognition and face processing in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:169–70. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.169. 185/2/169 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, Keefe RS, Christensen BK, Addington J, Woods SW, Callahan J, Zipursky RB, Perkins DO, Tohen M, Breier A, McGlashan TH. Neuropsychological course in the prodrome and first episode of psychosis: findings from the PRIME North America Double Blind Treatment Study. Schizophr Res. 2008;105:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.008. S0920-9964(08)00329-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RE. A social deafferentation hypothesis for induction of active schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1066–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm079. sbm079 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RE. Auditory/Verbal hallucinations, speech perception neurocircuitry, and the social deafferentation hypothesis. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2008;39:87–90. doi: 10.1177/155005940803900213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job DE, Whalley HC, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. Grey matter changes over time in high risk subjects developing schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1023–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.006. S1053-8119(05)00018-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Job DE, Whalley HC, McConnell S, Glabus M, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. Voxel-based morphometry of grey matter densities in subjects at high risk of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;64:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00158-0. S0920996403001580 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Anderson S, Pettegrew JW. Is schizophrenia due to excessive synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex? The Feinberg hypothesis revisited. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:239–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Dick E, Mankowski I, Harenski K, Montrose DM, Diwadkar V, DeBellis M. Decreased left amygdala and hippocampal volumes in young offspring at risk for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:173–83. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00404-2. S0920996401004042 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Broome MR, McGuire PK, David AS, Eddy M, Ozawa F, Goff D, West WC, Williams SC, van der Kouwe AJ, Salat DH, Dale AM, Fischl B. Regionally localized thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:878–88. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.878. 60/9/878 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie SM, McIntosh AM, Hall J, Owens DG, Johnstone EC. Brain structure and function changes during the development of schizophrenia: the evidence from studies of subjects at increased genetic risk. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:330–40. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm158. sbm158 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Thulborn KR, Munoz DP, Merriam EP, Garver KE, Minshew NJ, Keshavan MS, Genovese CR, Eddy WF, Sweeney JA. Maturation of widely distributed brain function subserves cognitive development. Neuroimage. 2001;13:786–93. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0743. S1053-8119(00)90743-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannerkoski MK, Heiskala HJ, Van Leemput K, Aberg LE, Raininko R, Hamalainen J, Autti TH. Subjects with intellectual disability and familial need for full-time special education show regional brain alterations: a voxel-based morphometry study. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:306–11. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181b1bd6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies DS, Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Biswal BB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Mapping the functional connectivity of anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage. 2007;37:579–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.019. S1053-8119(07)00409-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ. The “close-in” or ultra high-risk model: a safe and effective strategy for research and clinical intervention in prepsychotic mental disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:771–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, McKenzie D, Jackson HJ, Waddell F, Curry C. Can we improve the diagnostic efficiency and predictive power of prodromal symptoms for schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 2000;42:91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00125-5. S0920-9964(99)00125-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, McFarlane C, Patton GC, Bell R, Hibbert ME, Jackson HJ, Bowes G. The prevalence of prodromal features of schizophrenia in adolescence: a preliminary survey. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;92:241–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff AN, Decety J. What imitation tells us about social cognition: a rapprochement between developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:491–500. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, Hoffman R, Davidson L. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70:273–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1022034115078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, McFarlane W, Perkins DO, Pearlson GD, Woods SW. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, Eslinger PJ, Oliveira-Souza R. Frontopolar and anterior temporal cortex activation in a moral judgment task: preliminary functional MRI results in normal subjects. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59:657–64. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2001000500001. S0004-282X2001000500001 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller P, Husby R. The initial prodrome in schizophrenia: searching for naturalistic core dimensions of experience and behavior. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:217–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery KJ, Haxby JV. Mirror neuron system differentially activated by facial expressions and social hand gestures: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:1866–77. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Salisbury DF, Hirayasu Y, Bouix S, Pohl KM, Yoshida T, Koo MS, Shenton ME, McCarley RW. Neocortical gray matter volume in first-episode schizophrenia and first-episode affective psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:773–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.030. S0006-3223(07)00330-7 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B, Fornito A, Harrison BJ, Yucel M, Sass LA, Yung AR, Thompson A, Wood SJ, Pantelis C, McGorry PD. A disturbed sense of self in the psychosis prodrome: linking phenomenology and neurobiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:807–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.002. S0149-7634(09)00004-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Zinberg J, Johnson JK, O’Brien M, Cannon TD. The course of neurocognition and social functioning in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:772–81. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm020. sbm020 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortigue S, Thompson JC, Parasuraman R, Grafton ST. Spatio-temporal dynamics of human intention understanding in temporo-parietal cortex: a combined EEG/fMRI repetition suppression paradigm. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Yucel M, Wood SJ, McGorry PD, Velakoulis D. Early and late neurodevelopmental disturbances in schizophrenia and their functional consequences. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003a;37:399–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01193.x. 1193 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, Yucel M, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Sun DQ, McGorry PD. Neuroimaging and emerging psychotic disorders: the Melbourne ultra-high risk studies. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:371–81. doi: 10.1080/09540260701512079. 781049941 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Yucel M, Wood SJ, Velakoulis D, Sun D, Berger G, Stuart GW, Yung A, Phillips L, McGorry PD. Structural brain imaging evidence for multiple pathological processes at different stages of brain development in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:672–96. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi034. sbi034 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, Bullmore ET, Brewer W, Soulsby B, Desmond P, McGuire PK. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003b;361:281–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12323-9. S0140-6736(03)12323-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T. Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:60–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.008. S1364-6613(04)00320-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platek SM, Krill AL, Wilson B. Implicit trustworthiness ratings of self-resembling faces activate brain centers involved in reward. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:289–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.018. S0028-3932(08)00301-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platek SM, Loughead JW, Gur RC, Busch S, Ruparel K, Phend N, Panyavin IS, Langleben DD. Neural substrates for functionally discriminating self-face from personally familiar faces. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:91–8. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MR. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:434–49. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642. 4001642 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rilling J, Gutman D, Zeh T, Pagnoni G, Berns G, Kilts C. A neural basis for social cooperation. Neuron. 2002;35:395–405. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00755-9. S0896627302007559 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Smith AB, Woolley J, Nosarti C, Heyman I, Taylor E, Brammer M. Progressive increase of frontostriatal brain activation from childhood to adulthood during event-related tasks of cognitive control. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:973–93. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R. Uniquely human social cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:235–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.001. S0959-4388(06)00026-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilbach L, Eickhoff SB, Rotarska-Jagiela A, Fink GR, Vogeley K. Minds at rest? Social cognition as the default mode of cognizing and its putative relationship to the “default system” of the brain. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17:457–67. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.013. S1053-8100(08)00037-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Burnett S, Blakemore SJ. Development of the self-concept during adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:441–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.008. S1364-6613(08)00216-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Viding E, Williams KD, Blakemore SJ. Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.008. S0278-2626(09)00105-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in frontal and striatal regions. Nat Neurosci. 1999a;2:859–61. doi: 10.1038/13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Batth R, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. Localizing age-related changes in brain structure between childhood and adolescence using statistical parametric mapping. Neuroimage. 1999b;9:587–97. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0436. S1053-8119(99)90436-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Phillips L, Velakoulis D, Yung A, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, van Erp TG, Thompson PM, Toga AW, Cannon TD, Pantelis C. Progressive brain structural changes mapped as psychosis develops in ‘at risk’ individuals. Schizophr Res. 2010;108:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.11.026. S0920-9964(08)00529-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tae WS, Kim SS, Lee KU, Nam EC, Kim KW. Validation of hippocampal volumes measured using a manual method and two automated methods (FreeSurfer and IBASPM) in chronic major depressive disorder. Neuroradiology. 2008;50:569–81. doi: 10.1007/s00234-008-0383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulopoulou T, Grech A, Morris RG, Schulze K, McDonald C, Chapple B, Rabe-Hesketh S, Murray RM. The relationship between volumetric brain changes and cognitive function: a family study on schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.026. S0006-3223(04)00704-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin LQ, Kaplan JT, Molnar-Szakacs I, Zaidel E, Iacoboni M. Self-face recognition activates a frontoparietal “mirror” network in the right hemisphere: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2005;25:926–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.018. S1053-8119(04)00766-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overwalle F. Social cognition and the brain: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:829–58. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollm BA, Taylor AN, Richardson P, Corcoran R, Stirling J, McKie S, Deakin JF, Elliott R. Neuronal correlates of theory of mind and empathy: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study in a nonverbal task. Neuroimage. 2006;29:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.022. S1053-8119(05)00511-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Farrow TF, Gomes L, Brennan J, Harris AW, Williams LM. Grey matter deficits and symptom profile in first episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:229–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.05.010. S0925-4927(05)00072-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Farrow TF, Williams LM, Gomes L, Brennan J, Harris AW. Delusions and dorso-medial frontal cortex volume in first-episode schizophrenia: a voxel-based morphometry study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172:175–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.07.011. S0925-4927(08)00098-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Grieve SM, Farrow TF, Gomes L, Brennan J, Harris AW, Gordon E, Williams LM. Progressive grey matter atrophy over the first 2–3 years of illness in first-episode schizophrenia: a tensor-based morphometry study. Neuroimage. 2006;32:511–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.041. S1053-8119(06)00223-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JL, Heitmiller D, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P. Morphology of the ventral frontal cortex: relationship to femininity and social cognition. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:534–40. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm079. bhm079 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Ueda K, Namiki C, Hirao K, Hayashi T, Ohigashi Y, Murai T. Social cognition in schizophrenia: similarities and differences of emotional perception from patients with focal frontal lesions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;259:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0860-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd D. Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.03.009. S0959-4388(07)00041-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky RB, Lambe EK, Kapur S, Mikulis DJ. Cerebral gray matter volume deficits in first episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:540–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]