Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is currently one of the most treatment-resistant malignancies and affects approximately three in 10,000 people. The impact of this disease produces about 31,000 new cases in the United States per year; and 12,000 people in the United States alone die from RCC annually. Although several treatment strategies have been investigated for RCC, this cancer continues to be a therapeutic challenge. For this reason, the aim of our study is to develop a more effective combinational therapy to treat advanced RCC. We examined the effect of vinorelbine on the signalling pathways of two human renal cancer cell lines (A498 and 786-O) and also examined the in vivo effect of vinorelbine treatment alone and vinorelbine in combination with the anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 on A498 and 786-O tumour growth in nude mice. Tumour angiogenesis was measured by vWF staining, and apoptosis was determined by the TUNEL assay. We observed a significant tumour growth inhibition when using a combinational therapy of anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 and vinorelbine in both A498 and 786-O tumour-bearing mice. The results suggest a breakthrough treatment for advanced RCC.

Keywords: mice model, renal cell carcinoma, vinorelbine and 2C3

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer arising from the renal tubule as well as the most common type of kidney cancer in adults. One-third of patients diagnosed with RCC present with or will develop metastatic lesions during the course of the disease [1]. Because RCC is notoriously resistant to radiation therapy and chemotherapy as only some cases respond to immunotherapy with interferon-alpha (IFN-α) or interleukin-2 (IL-2), the initial treatment of choice is surgery. Recent reports state the objective response rates with IFN-α range from 10 to 15%; and in phase III studies, improvements in median survival are only 3–7 months compared with a placebo using equivalent therapy [2]. The outlook from cases using IL-2 cytokine treatment is not much better with a median survival period of approximately 10 months [3] and a 5-year survival rate of <10%[4]. In addition, many studies have suggested that the use of a high dose of IL-2 results in toxicity and thus, limits the applicability of the cytokine to RCC patients [5, 6].

Vascular permeability factor (VPF/VEGF) is a tumour-secreted cytokine of critical importance in both normal and tumour-associated angiogenesis. It is the most potent proangiogenic protein described to date with biological effects relevant to tumour angiogenesis. VEGF expression is regulated by a number of factors, including cytokines [7, 8], growth factors [9–11], hormones [12], hypoxia [13, 14] and tumour suppressor genes [15]. As found in the majority of RCC patients, VEGF expression is caused from the inactivation of a VHL tumour suppressor gene, and this distinguishing factor makes VEGF a relevant and critical therapeutic target with clinical potential. A number of targeted agents have been evaluated to treat RCC, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib and sorafenib [16], and rapamycin is often used as it inhibits mTOR proteins that promote tumour growth [17].

Compounds interfering with microtubule function form an important class of anticancer agents and are widely used in combination with chemotherapy regimens for treating many solid tumours as well as leukaemia [18]. One of the best-known classes of these agents is the dimeric vinca alkaloids. The vinca alkaloids are known to inhibit cell growth by their effects on the mitotic spindle microtubules. Cells accumulate in metaphase at a low concentration of vinca alkaloids and, during exposure to higher levels of drugs, mitotic spindles deteriorate as a result of altered tubulin dynamics [19]. Among different vinca alkaloid derivatives, vinorelbine was a third generation drug selected for development; this molecule has shown markedly improved clinical efficacy and is the least toxic [20]. The actions of vinorelbine on the mitotic spindle may constitute only one aspect of its cytotoxic action, as it has also been shown to modulate receptor binding of epidermal growth factor to breast cancer cells with potential consequences for cell viability [21].

In our study, a novel drug combination consisting of a cytotoxic agent (vinorelbine) with a recombinant mouse monoclonal antibody against human VEGF (2C3) has been evaluated for the treatment of metastatic RCC. We have chosen two cell lines: the highly malignant A498 cells and the lesser malignant 786-O cells for in vitro and in vivo study. Both of these cell lines are VHL-negative. As a control, the VHL-positive Caki1 cell line was used to check the effect of vinorelbine on in vitro cell viability. The results obtained justify pre-clinical studies to evaluate the effectiveness of a combined therapy using vinorelbine and 2C3 as a potential treatment for RCC.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Drugs: Vinorelbine is available from Gensia Sicor Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA); and the anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 is a mouse monoclonal antibody developed to target human VEGF, as described previously [22]. Control antibody (IgG) was purchased from Peregrine Pharmaceuticals (TX, USA). Anti-caspase-3 (#9662), caspase-8 (#9746), caspase-9 (#9502), anti-Cyclin A (#4656), p-mTOR (#2971), mTOR (#2972) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA), anti-mouse β-Actin and Cdk1 antibodies were purchased from BD-Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA), anti-p-Akt 1/2/3 (Ser473) (sc-7985), anti-Akt1 (sc-1618) anti-Cyclin B1 (sc-245), PCNA (sc-25280) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-pH3 antibody was from Upstate, NY. The TUNEL assay kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA), the vWF staining kit from Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA), and the PCNA staining kit from Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA, USA).

Cell culture

The human renal carcinoma cell lines (A498; ATCC HTB-44, 786-O; CRL-1932 and Caki1; HTB46; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in MEM, DMEM and McCoy’s 5A (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) medium, respectively, containing 10% FBS (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

In vitro cell growth inhibition assay

Cell viability was measured by MTT colorimetric assay system, which measures the reduction of a tetrazolium salt (MTS) to an insoluble formazan product by the mitochondria of viable cells. The RCC cell lines A498, 786-O and Caki1 cells were plated in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) overnight in a CO2 chamber. On the following day, cells were treated with different concentrations of vinorelbine and A498, 786-O and Caki1 cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 hrs, 48 hrs and 24 hrs, respectively, in a 5% CO2 chamber. Twenty μl of MTS/PMS solution from the MTT assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was then added into each well containing 100 μl of complete medium, and the plate was incubated for 30 min. at 37°C in a 5% CO2 chamber. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using an ELISA plate reader. The average of three separate experiments has been documented.

Cell cycle assay

A cell cycle assay was carried out following the standard protocol; DNA content was measured following the staining of cells with propidium iodide. After A498 and 786-O cells were treated with different concentrations of vinorelbine for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively, they were harvested by trypsinization and washed three times in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (1X) and fixed in 95% ethanol for 1 hr. Cells were then rehydrated and washed in PBS and treated with ribonuclease A (RNaseA; 1 mg/ml), followed by staining with PI (100 μg/ml). Flow cytometric quantification of DNA was carried out with the use of a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and data analysis was performed using Modfit software (Verity Software House, Topshaw, ME, USA). An average of three separate experiments has been shown.

Invasion assay

One hundred μl of 3 mg/ml Matrigel solution (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) was overlaid on the upper surface of transwell chambers with a diameter of 6.5 mm and a pore size of 8 μm (Corning CoStar Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA). The Matrigel was allowed to solidify by incubating the plates for ∼1 hr at 37°C. Respective medium (Hyclone) (0.6 ml) containing 10% FBS were then added to the bottom chamber of the transwells. A498 and 786-O RCC cells (treated with different concentrations of vinorelbine for 24 hrs) were trypsinized and then resuspended in corresponding medium containing no FBS. Subsequently, 2 × 105 cells/ml in a volume of 200 μl of medium were added to the upper chamber of each well. Cells were then incubated for 6 hrs at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Cells that remained in the upper chamber were removed by gently scraping with a cotton swab. Cells that had invaded through the filter were fixed in 100% methanol and then stained with 0.2% crystal violet dissolved in 2% ethanol. Invasion was quantitated by counting the number of cells on the filter using bright-field optics with a Nikon Diaphot microscope equipped with a 16-square reticule (1 mm2). Four separate fields were counted for each filter. The average of three separate experiments has been documented.

In vitro apoptosis assay using Annexin V-FITC kit

A498 and 786-O cells were cultured in MEM and DMEM medium, respectively (10% FBS), overnight; and thereafter, the cells were treated with different concentrations of vinorelbine as well as with different concentrations of 2C3 for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively. Surface exposure of phosphatidylserine from apoptosis was measured by adding Annexin-V-FITC (Biovision, Mountain View, CA, USA) before analysis using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). Additional exposure to propidium iodide (PI) made it possible to differentiate early apoptotic cells (Annexin-positive and PI-negative) from late apoptotic cells (Annexin- and PI-positive). Again, an average of three separate experiments has been documented.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to detect the levels of Cyclin A, Cyclin B1, Cdk1, p-histone and PCNA expression, Akt and mTOR phosphorylation, and caspase activation in vinorelbine-treated A498 and 786-O cells. A498 and 786-O cells were washed with PBS and lysed with RIPA buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail after 72 hrs and 48 hrs of treatment, respectively. Mitotic shake-off cells were also incorporated into the study to check cell-cycle protein expression. Supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes and immunoblotted. Antibody-reactive bands were detected by enzyme-linked chemiluminescence (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and quantified by laser densitometry. These experiments were repeated at least three times.

Tumour model

Six-week-old female nude mice were obtained from NIH and were housed in the institutional animal facilities. All animal work was performed under protocols approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To establish tumour growth in mice, 5 × 106 A498 and 786-O cells, resuspended in 100 μl of PBS, were injected subcutaneously into the right flank.

In vivo anti-tumour activity

Tumours were allowed to grow for 7 days without treatment. On day 8 post-tumour cell injection, mice were randomized into four groups (five animals per group), and treatment was initiated. Group 1 was treated with control antibody alone, while Group 2 was treated with vinorelbine at doses of 5 mg/kg/week intraperitoneally. Group 3 was treated with anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 alone, administered at 50 μg per injection intraperitoneally three times per week during the first week and twice during the following weeks. Group 4 was treated with anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 combined with vinorelbine. Tumours were measured weekly, and primary tumour volumes were calculated with the formula V = 1/2a × b2, where ‘a’ is the longest tumour axis, and ‘b’ is the shortest tumour axis. After 8 weeks of treatment, all A498 tumour-bearing mice were killed by asphyxiation with CO2; tumours were removed, measured, and prepared for immunochemistry and the TUNEL assay. In 786-O tumour-bearing mice, treatments continued for 4 weeks.

Histological study

A498 tumours were removed and fixed in neutral buffered 10% formalin at room temperature for 24 hrs prior to embedding in paraffin and sectioning. Sections were deparaffinized and then subjected to vWF and PCNA immunochemistry staining and TUNEL staining for apoptosis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stable diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen substrate, and the sections were counterstained with a haematoxylin solution. The PCNA- or TUNEL-positive nuclei were counted in the entire section. Thereafter, 10 fields of vision were photographed, the total number of nuclei was counted, and the average number of nuclei/unit area was calculated. Photographs of the entire cross-section were digitized using an Olympus camera (DP70). The proliferation index and apoptosis index were calculated as the number of positive nuclei divided by the total number of nuclei. To access heterogeneity with regards to proliferation within an individual tumour, sections were taken from three different areas of the tumour and the proliferative index was determined as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the statistical SPSS software (version #11.5; Chicago, IL, USA). The independent-samples t-test was used to test the probability of significant differences between groups. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05(*); statistical high significance was defined as P < 0.01(**). Error bars were given on the basis of calculated standard deviation values.

Results

Inhibition of cell growth

The anti-proliferative effect of vinorelbine against different human cell lines has already been established [23–25]. To verify its effect on renal cancer cell growth, A498 and 786-O cells were treated with increasing concentrations of vinorelbine (10 nM, 100 nM, and 1μM) and cell survival was assessed with the MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 1, survival was inversely correlated with drug concentration. Significant loss of A498 and 786-O viability was detected at 100 and 10 nM of vinorelbine, respectively, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1, P < 0.01 compared to untreated cells). In Caki1 RCC cells, 10 nM of vinorelbine treatment caused significant growth inhibition after only 24 hrs of treatment (Fig. S1).

Fig 1.

Effect of vinorelbine on A498 and 786-O renal cancer cell growth in vitro. A498 and 786-O cells were treated with three different doses of vinorelbine for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively, and cell viability was measured by the MT T colorimetric method (see Materials and Methods). A dose-dependent inhibition was observed for A498 and 786-O cell growth with vinorelbine. A dose of 100 nM was sufficient to inhibit A498 cell gowth. 786-O cells growth was significantly inhibited with a 10 nM dose. **, P < 0.01 (heated group versus control group).

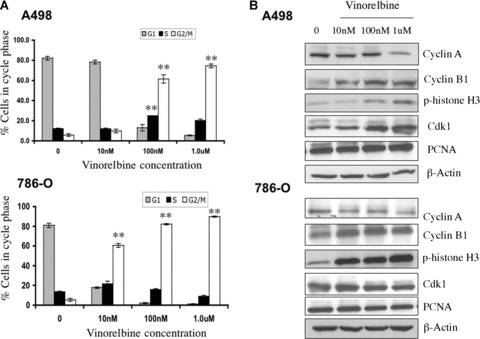

Effect on cell cycle

Regulators of cell cycle phase transitions could be important targets for cancer treatment using cytostatic chemotherapy. There are several reports describing the effect of vinca alkaloids on cell cycle phase perturbations and on vinorelbine treatment causing general G2/M phase arrest [24, 26]. Cell cycle analysis with different concentrations of vinorelbine treatments in A498 cells is shown in Fig. 2A. A 100 nM concentration of vinorelbine led to increases in both the G2/M (P < 0.01) as well as S-phase (P < 0.01) fractions, whereas only a 10 nM dose caused significant G2/M arrest in 786-O cells (P < 0.01). There was also a moderate increase in the S-phase fraction of 786-O cells after a 10 nM vinorelbine treatment (Fig. 2A).

Fig 2.

In vitro effect of vinorelbine on A498 and 786-O cell cycle regulation and cell cycle protein expression. (A) Three different doses of vinorelbine were used to assess the effect of vinorelbine on cell cycle regulation in A498 and 786-O cells. At a 100 nM dose, a significant G2/M phase arrest (P < 0.01 compared to untreated cells) was observed in A498, whereas 786-O cells arrested at the G2/M phase with a 10 nM dose of vinorelbine. **, P < 0.01(treated group versus control group). (B) When A498 and 786-O cells were treated with vinorelbine for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively, increased Cyclin B1, phospho-histone H3, and Cdk1 were detected with doses of 100 nM and 10 nM of vinorelbine in A498 and 786-O tumours cells, respectively. In both cell lines, Cyclin A was decreased with a 1 μM dose. PCNA expression did not change with any treatments. In each case, β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Effect of vinorelbine on Cyclin A, Cyclin B1, Cdk1, p-histone H3 and PCNA expression

Cell cycle is the orchestrated series of molecular events. Progression through successive stages of cell cycle is accompanied by the altered expression and lack of expression of specific regulatory proteins. Cyclin B1, expressed in the G2/early M phase of the cell cycle [27], and Cyclin A seem to be required for both the S and M phases [28]. A498 and 786-O cells were treated with three different doses of vinorelbine for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively. In both cell lines, we observed a significant decrease in Cyclin A expression with a 1.0 μM dose (Fig. 2B). In both A498 and 786-O cells, a steady increase of Cyclin B1 was detected with 10 nM to 1.0 μM dose treatments. Furthermore, phosphorylated histone H3 was expressed during mitosis [27]. In both cell lines, the level of histone H3 phosphorylation progressively increased in a dose-dependent manner after treatment with vinorelbine (Fig. 2B). The G2/M transition is triggered by the regulation of the Cyclin B1–Cdk1 complex, which promotes the breakdown of the nuclear membrane, chromatin condensation and microtubule spindle formation [29]. Immunoblotting revealed that vinorelbine drug treatment resulted in a significant induction of Cdk1 protein levels but not in PCNA expression.

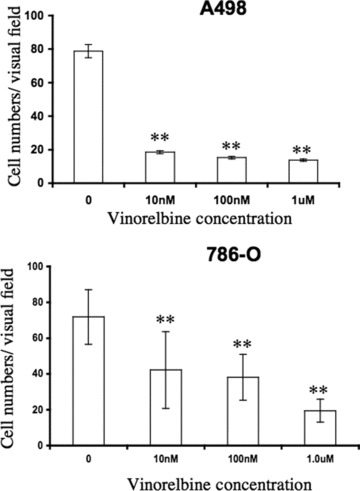

Effect of vinorelbine on cell invasion

Invasion of tumour cells through the matrix of the microenvironment is an early process of metastasis. It was reported that exposure to vinorelbine inhibits in vitro invasiveness of transitional cell bladder carcinoma [23]. To determine whether vinorelbine plays an inhibitory role in the invasion of renal cancer cells, we performed a Matrigel invasion assay in the presence or absence of the drug. Figure 3 shows a 10 nM dose of vinorelbine was sufficient to inhibit the invasion of both A498 and 786-O cells (P < 0.01).

Fig 3.

Effect of vinorelbine on A498 and 786-O invasion in vitro. The effect of vinorelbine on A498 and 786-O cells invasion was assayed after 24 hrs of treatment. A 10 nM dose of vinorelbine was sufficient to inhibit both A498 and 786-O cells invasion after 6 hrs (P < 0.01 compared to untreated cells). The values represent an average of three separate experiments. **, P < 0.01 (treated group versus control group).

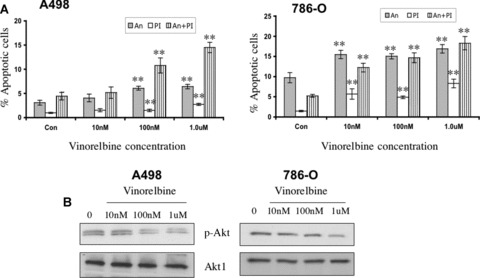

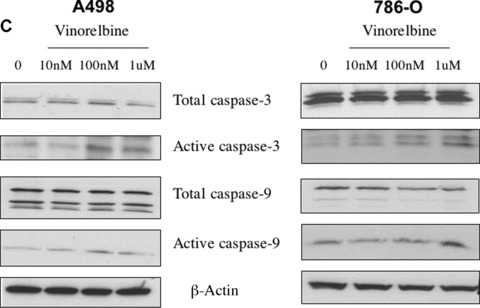

Effect of vinorelbine on cell apoptosis

A therapeutic approach will most likely require a drug-mediated induction of apoptotic activity on the cancer cell. Figure 4A describes apoptosis measurement using Annexin/PI. We observed a dose-dependent induction of apoptosis in A498 and 786-O cells after vinorelbine treatment. A 100 nM dose of the drug induced significant apoptosis in A498 cells, whereas in 786-O cells only a 10 nM dose of vinorelbine was sufficient to induce marked apoptosis. No induction in apoptosis was observed when treating with 2C3 (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Effect of vinorelbine on A498 and 786-O apoptosis, Akt phosphorylation and caspase activity in vitro. (A) A498 and 786-O apoptosis were measured following treatment with different doses of vinorelbine after 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively, by the Annexin/PI method. At a 100 nM concentration, significantly higher levels of Annexin/PI staining were recorded in vinorelbine-treated A498 cells (P < 0.01). In 786-O renal cancer cells, only 10 nM dose of vinorelbine induced significant apoptosis (P < 0.01). **, P < 0.01(treated group versus control group). (B) After A498 cells were treated with vinorelbine for 72 hrs, a down-regulation of Akt phosphorylation was observed in the 100 nM treatment group. In 786-O, a marked down-regulation in Akt phosphorylation was observed at a 1.0 μM dose after 48 hrs of treatment. Total Akt1 was used as a loading control. (C) A498 and 786-O cells were treated with vinorelbine for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively, and increased caspase-3 and -9 activity was detected in the 100 nM and 1.0 μM dose treatment groups of A498 and 786-O, respectively. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Effect of vinorelbine on Akt and mTOR phosphorylation

Akt is involved in the cellular survival pathways by inhibiting apoptotic processes, because it can block apoptosis and thereby promote cell survival. Akt activation may contribute to tumour invasion/ metastasis by stimulating the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases [30]. A498 and 786-O cells were treated with three different doses of vinorelbine for 72 hrs and 48 hrs, respectively. With a 100 nM dose of vinorelbine, a significant inhibition of Akt phosphorylation was observed in A498 cells (Fig. 4B). In 786-O cells, only minor decreases in Akt phosphorylation were observed with 10 nM and 100 nM doses. However, 1.0 μM dose of vinorelbine treatment resulted in a clear decrease in Akt phosphorylation. Vinorelbine has no effect on mTOR phosphorylation (data not shown).

Effect on apoptosis markers: increased caspase activity

The caspase cascade system plays a vital role in the induction, transduction and amplification of intracellular apoptotic signals. Researchers have shown that vinorelbine treatment induces caspase-3 activation in leukaemia and lymphoma cells [31]. We found that a 100 nM dose was sufficient for the induction of activated capase-3 and -9 activity in A498 cells after 72 hrs treatment (Fig. 4C). A 48-hr vinorelbine treatment of 100 nM in 786-O cells caused little increase in both caspase-3 and caspase-9, but a significant increase was detected with a 1.0 μM dose (Fig. 4C). However, no change in the level of activated caspase-8 was detected in A498 and 786-O cells after vinorelbine treatment.

Effect of vinorelbine in combination with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody 2C3 on tumour volume in vivo

To investigate the effect of vinorelbine alone or in combination with anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 on renal tumour growth, we injected A498 and 786-O human RCC cell lines subcutaneously into nude mice. After 7 days, vinorelbine alone (5 mg/kg), 2C3 alone (50 μg/injection) and both in combination were administered intraperitoneally. Treatments were continued for 4 and 8 consecutive weeks for mice bearing 786-O and A498 tumours, respectively. All control mice received an equal volume of the control antibody. We found a significant effect on tumour suppression among the A498 tumour-bearing mice treated with vinorelbine and 2C3 compared to mice treated with vinorelbine alone (P= 0.012) (Fig. 5A). In A498 renal carcinoma, the combination therapy also significantly improved the response compared to the single 2C3 therapy (P= 0.031) (Fig. 5A). The average tumour volume was observed to be 1320.8 ± 186.0 mm3 in the control group, 886.0 ± 196.0 mm3 in the vinorelbine-treated group, 159.2 ± 49.0 mm3 in the 2C3-treated group and 31.2 ± 5.8 mm3 in the group receiving both vinorelbine and 2C3. In the 786-O renal cancer model, the effect of the combination therapy was moderately active compared to the A498 model (P= 0.01, compared to control) (Fig. 5B). However, in 786-O-tumour bearing mice, the effect of the single vinorelbine treatment was significant (P= 0.026 compared to control). Single 2C3 treatment was also effective in this group but not statistically significant (P= 0.065 compared to control). In this group, the average tumour volume was observed to be 381.2 ± 177.0 mm3 in the control group, 161.4 ± 35.4 mm3 in the vinorelbine-treated group, 169.6 ± 132.1 mm3 in the 2C3-treated group and 103.4 ± 87.2 mm3 in the group receiving both vinorelbine and 2C3 (Fig. 5B) at the end of the 4th week of treatment.

Fig 5.

Effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with VEGF antibody 2C3 on renal cancer tumour growth in vivo. Mice received subcutaneous injections of A498 and 786-O cell lines, and tumours were allowed to grow for 7 days before the initiation of single-agent treatment with vinorelbine, single-agent treatment with 2C3, or combination treatment with vinorelbine and 2C3. The control group received only control antibody. (A) Average A498 tumour volumes at week 8 in control and treatment groups. Animals that received vinorelbine alone did have moderate response. By contrast, combination therapy-treated group showed ∼98% tumour growth inhibition. (B) Average 786-O tumour volumes at week 4 in control and treatment groups. The animals receiving the combination treatment showed a significant response in terms of tumour growth regression (P= 0.01). *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01(treated group versus control group).

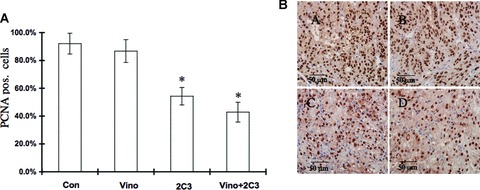

Effect of vinorelbine in combination with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody 2C3 on PCNA expression in vivo

To determine whether the observed tumour growth suppression was caused by inhibition of cell proliferation, we investigated the effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with 2C3 on tumour cell proliferation as measured by proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Fig. 6A and B). The average number of PCNA-positive nuclei in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields is shown in Fig. 6A. No significant effect was observed in the inhibition of renal tumour cell proliferation in the vinorelbine-treated group compared to the control group in relation to PCNA expression. However, there was significant inhibition in PCNA expression in the vinorelbine and 2C3-treated group (P < 0.05, treated group versus control group).

Fig 6.

Effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with VEGF antibody 2C3 on PCNA expression in vivo. (A) Nude mice were treated with vinorelbine, 2C3, or vinorelbine in combination with 2C3 after subcutaneous injection of the renal cancer cell line A498. The control group received control antibody. Treatment of vinorelbine in vivo showed no considerable effect on PCNA expression. 2C3 alone or in combination with vinorelbine demonstrated a significant effect on the inhibition of the PCNA level. *, P < 0.05 (treated group versus control group). (B) PCNA-stained tumour sections. (A) Control group received only control antibody, (B) received vinorelbine only, (C) received 2C3 only and (D) received both vinorelbine and 2C3.

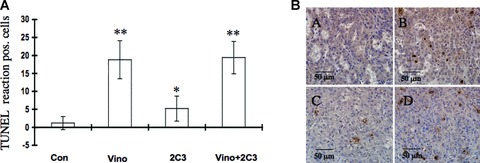

Effect of vinorelbine in combination with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody 2C3 on tumour cell apoptosis in vivo

To further investigate the mechanism of the observed tumour-suppressive activities, we examined the effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with 2C3 on A498 tumour cell apoptosis in vivo with the TUNEL assay (Fig. 7A and B). The average number of TUNEL-positive cells measured in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields in different treatment groups was calculated. A significant increase in the number of apoptotic cells was observed in the group treated with vinorelbine alone (P < 0.01, compared to the control group) and in the combination treatment group (P < 0.01, treated group versus control group) (Fig. 7A).

Fig 7.

Effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with VEGF antibody 2C3 on tumour cell apoptosis in vivo. Nude mice were treated with vinorelbine, 2C3, or vinorelbine in combination with 2C3 after subcutaneous injection of the A498 renal cancer cell line. The control group received control antibody alone. (A) To detect apoptosis, a TUNEL assay was performed. The average number of TUNEL-positive cells was scored in 10 randomly selected microscopic fields. Vinorelbine as a single therapeutic agent and in combination with 2C3 caused significant tumour cell apoptosis. *, P < 0.05 and **, P < 0.01(treated group versus control group). (B) TUNEL-positive nuclei in different treatment groups. (A) Control group received only control antibody (B) received vinorelbine only, (C) received 2C3 only and (D) received both vinorelbine and 2C3.

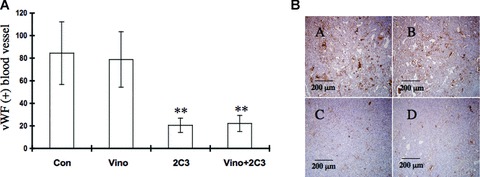

Effect of vinorelbine in combination with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody 2C3 on tumour angiogenesis

In our next step, we were interested to determine the effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with 2C3 on tumour angiogenesis. Therefore, we stained tumour sections from the A498 renal cancer model with anti-vWF antibody (Fig. 8A and B) and measured the average number of vWF-positive vessels. A significant decrease in the number of stained vessels was found in the 2C3-treated group (P < 0.01, compared to control group) and the 2C3- and vinorelbine-treated groups (P < 0.01, treated group versus control group) (Fig. 8A).

Fig 8.

Effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with VEGF antibody 2C3 on tumour angiogenesis in vivo. Nude mice were treated with vinorelbine, 2C3, or vinorelbine in combination with 2C3 after subcutaneous injection of A498 renal cancer cell line. The control group received control antibody alone. (A) To determine the effect of vinorelbine alone and in combination with 2C3 on tumour angiogenesis, tumour sections were stained with anti-vWF antibody using a vWF staining kit (see Materials and Methods). Vinorelbine might have no effect on the inhibition of tumour angiogenesis. **, P < 0.01 (treated group versus control group). (B) vWF-positive cells in different treatment groups. (A) Control group received only control antibody, (B) received vinorelbine only, (C) received 2C3 only and (D) received both vinorelbine and 2C3.

Discussion

The management of RCC has constituted a therapeutic challenge and no standard therapy has been established until now. Conventional clear cell RCC comprises two-thirds of renal masses and has a less favourable outcome compared to papillary RCC and chromophobe RCC [32]. Though several treatment strategies have been investigated for RCC, the best therapeutic option is yet to be discovered.

Vinca alkaloids are a very important class of drugs used for the treatment of different cancers. Of these, vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine and vinflunine have been used either singly or in combination with other drugs in different phases of clinical trials for patients with advanced RCC [33–36].

Vinorelbine, a semi-synthetic vinca alkaloid with a broad spectrum of anti-tumour activity, has been used as a single agent in inoperable or advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and was also found to be effective in slowing metastasis in advanced breast cancer as a first liner or later chemotherapy [37].

Vinorelbine has also emerged as a therapeutic option for breast cancer chemotherapy during pregnancy with a very favourable toxicity profile [38]. It was reported that the combination of vinorelbine and trastuzumab for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer was effective and well tolerated [39]. Despite broad-spectrum use of vinorelbine in the management of different cancers, there are very few reports on the use of vinorelbine for the treatment of metastatic RCC [40]. In this study, our data indicate that vinorelbine in combination with anti-angiogenic therapy strongly inhibits primary RCC tumour growth in vivo. Here, we intend to show the effect of vinorelbine on the various phases of RCC tumour progression. Prior to beginning the in vivo experiment, we investigated the in vitro effect of vinorelbine on cell growth, cell cycle, invasion, and apoptosis in A498 and 786-O metastatic RCC cell lines. We observed that vinorelbine was more active against less aggressive 786-O cells than highly aggressive A498 cells. Vinorelbine caused cell cycle G2/M arrest and induced apoptosis by up-regulating caspases 3 and 9, down-regulating Akt phosphorylation and inhibiting tumour cell invasion. PCNA is a nuclear protein essential for DNA synthesis in eukaryotic cells, and its expression normally indicates the G1/S-phase transition [41]. However, because vinorelbine induces cell arrest by inhibiting the G2/M transition, this may explain why it did not affect PCNA expression either in vitro or in vivo. We also observed that in the case of VHL positive Caki1 cells, vinorelbine was successful in inhibiting cell growth. The results obtained in vitro with the A498 and 786-O cell lines would justify the suitability of vinorelbine for the treatment of RCC.

Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, already has evolved to be one of the primary targeting agents for the treatment of RCC [42, 43]. It is an FDA-approved drug, which has shown efficacy in both the first and second line stages of Phase II clinical trials with metastatic RCC [44]. Bevacizumab has also demonstrated clinical activity in metastatic RCC in other Phase II trials [45, 46]. 2C3, an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, prevents VEGF from binding to the VEGF receptor VEGFR-2/KDR/Flk-1 but not VEGFR-1/Flt-1. 2C3 is specific to human VEGF (both VEGF121 and VEGF165), and its role has already been established in the treatment of different cancer models in mice [47–49].

Researchers have employed varying doses of vinorelbine for the treatment of different cancers (e.g. lung cancer, ovarian cancer) in mice xenograft models [50, 51]. Here, we have used a 5 mg/kg dose of vinorelbine and 50 μg of 2C3 for the treatment of mice with RCC. It is critical to note that in our study we have been able to achieve tumour inhibition while using half of the normal dose of the 2C3 antibody [48]. We found that a single-agent treatment with vinorelbine failed to produce significant A498-tumour growth inhibition in mice compared to the untreated group. However, a desired anti-tumour response was obtained when mice were treated with vinorelbine in combination with anti-VEGF 2C3. This combination therapy was highly active against the A498 solid tumour and we observed ∼98% tumour growth inhibition (P < 0.01). In 786-O-tumour bearing mice, single vinorelbine and combination treatments induced marked inhibition of tumour growth (P= 0.026 and 0.01 compared to control, respectively) after only 4 weeks of treatment. The difference in treatment outcome between A498 and 786-O was not due to the p53 status (both have wild type p53) [52] but could be explained that administration of 2C3 in A498 tumour bearing mice sensitizes the tumour cells to the anti-tumour activity of vinorelbine.

However, from the TUNEL assay and PCNA staining, it was evident that in vivo vinorelbine caused a significant induction of apoptosis but failed to inhibit tumour cell proliferation in terms of PCNA expression. The suppression of tumour growth in the combination therapy-treated group, therefore, was caused by a combinatorial effect of both vinorelbine and 2C3. Vinorelbine plays a major role in regulating cell apoptosis and 2C3 is important for inhibiting tumour angiogenesis. Previous reports have already shown that vinca alkaloid impaired tumour growth by inhibiting HIF-1 levels [53]. Hence, vinorelbine-mediated down-regulation of HIF-1 might also be one of the potential mechanisms for tumour growth inhibition.

Consequently, our work shows that a combination therapy of vinorelbine and anti-VEGF antibody 2C3 could be a new and promising strategy for the treatment of RCC compared to a single-agent therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work is partly supported by NIH grants CA78383, HL072178 and HL70567 to DM.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1 Effect of vinorelbine on Caki1 renal cancer cellgrowth in vitro. Caki1 cells were treated with threedifferent doses of vinorelbine for 24 hrs and cell viability wasmeasured by the MTT colorimetric method. A dose of 10 nM wassufficient to inhibit Caki1 cell growth in vitro. **,P < 0.01 (treated group versus control group).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Flanigan RC, Campbell SC, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:385–90. doi: 10.1007/s11864-003-0039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fossa SD. Interferon in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:187–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:454–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow WH, Devesa SS, Warren JL, et al. Rising incidence of renal cell cancer in the United States. JAMA. 1999;281:1628–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bambust I, Van Aelst F, Joosens E, et al. A Belgian registry of interleukin-2 administration for treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer and confrontation with literature data. Acta Clin Belg. 2007;62:223–9. doi: 10.1179/acb.2007.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam JS, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA. Advances in immune-based therapies of renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2004;4:1081–96. doi: 10.1586/14737140.4.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen T, Nahari D, Cerem LW, et al. Interleukin 6 induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:736–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto K, Ohi H, Kanmatsuse K. Interleukin 10 and interleukin 13 synergize to inhibit vascular permeability factor release by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with lipoid nephrosis. Nephron. 1997;77:212–8. doi: 10.1159/000190275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claffey KP, Abrams K, Shih SC, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 activation of stromal cell vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis. Lab Invest. 2001;81:61–75. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pertovaara L, Kaipainen A, Mustonen T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is induced in response to transforming growth factor-beta in fibroblastic and epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6271–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryuto M, Ono M, Izumi H, et al. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor by tumor necrosis factor alpha in human glioma cells. Possible roles of SP-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28220–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang TH, Horng SG, Chang CL, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin-induced ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is associated with up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3300–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy AP, Levy NS, Wegner S, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the rat vascular endothelial growth factor gene by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13333–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pal S, Datta K, Mukhopadhyay D. Central role of p53 on regulation of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) expression in mammary carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6952–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rini BI. Sunitinib. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2359–69. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.14.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutcher JP. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6382S–7S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowinsky ER, Donehower RC. Antimicrotubule agents. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Reven; 1997. pp. 468–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan MA, Thrower D, Wilson L. Mechanism of inhibition of cell proliferation by Vinca alkaloids. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2212–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson SA, Harper P, Hortobagyi GN, et al. Vinorelbine: an overview. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22:127–42. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(96)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Depenbrock H, Shirvani A, Rastetter J, et al. Effects of vinorelbine on epidermal growth factor-receptor binding of human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Invest New Drugs. 1995;13:187–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00873799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brekken RA, Huang X, King SW, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor as a marker of tumor endothelium. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1952–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonfil RD, Russo DM, Schmilovich AJ. Exposure to vinorelbine inhibits in vitro proliferation and invasiveness of transitional cell bladder carcinoma. J Urol. 1996;156:517–21. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199608000-00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ngan VK, Bellman K, Hill BT, et al. Mechanism of mitotic block and inhibition of cell proliferation by the semisynthetic Vinca alkaloids vinorelbine and its newer derivative vinflunine. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:225–32. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Photiou A, Sheikh MN, Bafaloukos D, et al. Antiproliferative activity of vinorelbine (Navelbine) against six human melanoma cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1992;118:249–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01208613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngan VK, Bellman K, Panda D, et al. Novel actions of the antitumor drugs vinflunine and vinorelbine on microtubules. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5045–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson EJ, Morris LS, Scott IS, et al. Minichromosome maintenance (Mcm) proteins, cyclin B1 and D1, phosphohistone H3 and in situ DNA replication for functional analysis of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:257–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, et al. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–71. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King RW, Jackson PK, Kirschner MW. Mitosis in transition. Cell. 1994;79:563–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thant AA, Nawa A, Kikkawa F, et al. Fibronectin activates matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion via the MEK1-MAPK and the PI3K-Akt pathways in ovarian cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2000;18:423–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1010921730952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toh HC, Sun L, Koh CH, et al. Vinorelbine induces apoptosis and caspase-3 (CPP32) expression in leukemia and lymphoma cells: a comparison with vincristine. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;31:195–208. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck SD, Patel MI, Snyder ME, et al. Effect of papillary and chromophobe cell type on disease-free survival after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:71–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02524349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Galley R, Keane TE, Sun C. Camptothecin analogues and vinblastine in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: an in vivo study using a human orthotopic renal cancer xenograft. Urol Oncol. 2003;21:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(02)00243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein D, Ackland SP, Bell DR, et al. Phase II study of vinflunine in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2006;24:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-6437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motzer RJ, Lyn P, Fischer P, et al. Phase I/II trial of dexverapamil plus vinblastine for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1958–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmeri S, Gebbia V, Russo A, et al. Vinblastine and interferon-alpha-2a regimen in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Tumori. 1990;76:64–5. doi: 10.1177/030089169007600117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goa KL, Faulds D. Vinorelbine. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical use in cancer chemotherapy. Drugs Aging. 1994;5:200–34. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199405030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mir O, Berveiller P, Ropert S, et al. Emerging therapeutic options for breast cancer chemotherapy during pregnancy. Ann Oncol. 2007;19:607–13. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catania C, Medici M, Magni E, et al. Optimizing clinical care of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a new oral vinorelbine plus trastuzumab combination. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1969–75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guida M, Lorusso V, De Lana M. Subcutaneous rIL-2 plus vinorelbine(VNB) and gemcitabin (GEM) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Annu Meet Am Soc Clin Oncol (ASCO) 2002;21:2420. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi T, Caviness VS., Jr PCNA-binding to DNA at the G1/S transition in proliferating cells of the developing cerebral wall. J Neurocytol. 1993;22:1096–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01235751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longo R, D’Andrea MR, Sarmiento R, et al. Integrated therapy of kidney cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:vi141–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rini BI, Small EJ. Biology and clinical development of vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1028–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hainsworth JD, Sosman JA, Spigel DR, et al. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with a combination of bevacizumab and erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7889–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.8234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomsson DS, Greco FA, Spigel DR, et al. Bevacizumab, erlotinib, and imatinib in the treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: update of a multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:240s. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holloway SE, Beck AW, Shivakumar L, et al. Selective blockade of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 with an antibody against tumor-derived vascular endothelial growth factor controls the growth of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma xenografts. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1145–55. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stephan S, Datta K, Wang E, et al. Effect of rapamycin alone and in combination with antiangiogenesis therapy in an orthotopic model of human pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6993–7000. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang W, Ran S, Sambade M, et al. A monoclonal antibody that blocks VEGF binding to VEGFR2 (KDR/Flk-1) inhibits vascular expression of Flk-1 and tumor growth in an orthotopic human breast cancer model. Angiogenesis. 2002;5:35–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1021540120521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Forest V, Peoc’h M, Campos L, et al. Effects of cryotherapy or chemotherapy on apoptosis in a non-small-cell lung cancer xenografted into SCID mice. Cryobiology. 2005;50:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolberg HC, Villena-Heinsen C, Deml MM, et al. Relationship between chemotherapy with paclitaxel, cisplatin, vinorelbine and titanocene dichloride and expression of proliferation markers and tumour suppressor gene p53 in human ovarian cancer xenografts in nude mice. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stickle NH, Cheng LS, Watson IR, et al. Expression of p53 in renal carcinoma cells is independent of pVHL. Mutat Res. 2005;578:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Escuin D, Kline ER, Giannakakou P. Both microtubule-stabilizing and microtubule-destabilizing drugs inhibit hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha accumulation and activity by disrupting microtubule function. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9021–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Effect of vinorelbine on Caki1 renal cancer cellgrowth in vitro. Caki1 cells were treated with threedifferent doses of vinorelbine for 24 hrs and cell viability wasmeasured by the MTT colorimetric method. A dose of 10 nM wassufficient to inhibit Caki1 cell growth in vitro. **,P < 0.01 (treated group versus control group).