Summary

Genetic variation in FOXO3A has previously been associated with human longevity. Studies published so far have been case–control studies and hence vulnerable to bias introduced by cohort effects. In this study we extended the previous findings in the cohorts of oldest old Danes (the Danish 1905 cohort, N = 1089) and middle-aged Danes (N = 736), applying a longitudinal study design as well as the case–control study design. Fifteen SNPs were chosen in order to cover the known common variation in FOXO3A. Comparing SNP frequencies in the oldest old with middle-aged individuals, we found association (after correction for multiple testing) of eight SNPs; 4 (rs13217795, rs2764264, rs479744, and rs9400239) previously reported to be associated with longevity and four novel SNPs (rs12206094, rs13220810, rs7762395, and rs9486902 (corrected P-values 0.001–0.044). Moreover, we found association of the haplotypes TAC and CAC of rs9486902, rs10499051, and rs12206094 (corrected P-values: 0.01–0.03) with longevity. Finally, we here present data applying a longitudinal study design; when using follow-up survival data on the oldest old in a longitudinal analysis, we found no SNPs to remain significant after the correction for multiple testing (Bonferroni correction). Hence, our results support and extent the proposed role of FOXO3A as a candidate longevity gene for survival from younger ages to old age, yet not during old age.

Keywords: human longevity, Forkhead box O3A (FOXO3A), association study, case–control and longitudinal data

Introduction

Genetic factors contribute to the variation in human life span by approximately 25% (Herskind et al. 1996), a contribution believed to be minimal before age 60 years and most profound from age 85 years onwards (Hjelmborg et al. 2006). Candidate longevity genes encode proteins involved in several biological processes including the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway (Christensen et al. 2006), in which the transcription factor fork-head box O3A (Foxo3a) is of key importance.

Variation in the gene encoding Foxo3a (FOXO3A) has previously been reported to be associated with human longevity. Willcox et al. (2008) first reported on the associations of FOXO3A single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with longevity in male Americans of Japanese ancestry (rs2764264 (P-value (P) = 0.0002), rs13217795 (P = 0.0006) and rs2802292 (P < 0.0001)), associations which were subsequently confirmed (with effects pointing in the same direction) in Italian, American (northern and western European ancestry), Chinese and German populations (Anselmi et al. 2009; Flachsbart et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009; Pawlikowska et al. 2009). These studies reported 6 of 16 tagging SNPs (five specific to males and one to females) (Anselmi et al. 2009), 3 of 16 tagging SNPs (both genders) (Flachsbart et al. 2009), 2 of 16 tagging SNPs (specific to females) (Pawlikowska et al. 2009), and 3 of 3 tagging SNPs (both genders) (Li et al. 2009) to be associated with longevity. Furthermore, two studies reported on the associations of FOXO3A haplotypes with longevity (Anselmi et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009).

The studies published so far have been case–control studies (comparing oldest old to younger controls), raising concerns about possible cohort effects introducing bias (Beekman et al. 2006; Christensen et al. 2006). In this study we aimed to add further support and to extend the evidence for a role of FOXO3A in longevity by investigating 15 FOXO3A SNPs covering the known common genetic variation in FOXO3A in two populations of middle-aged and oldest old Danes, applying the case–control study design (middle-aged versus oldest old) as well as a longitudinal study design (oldest old only).

Results

Genotype and allele frequencies

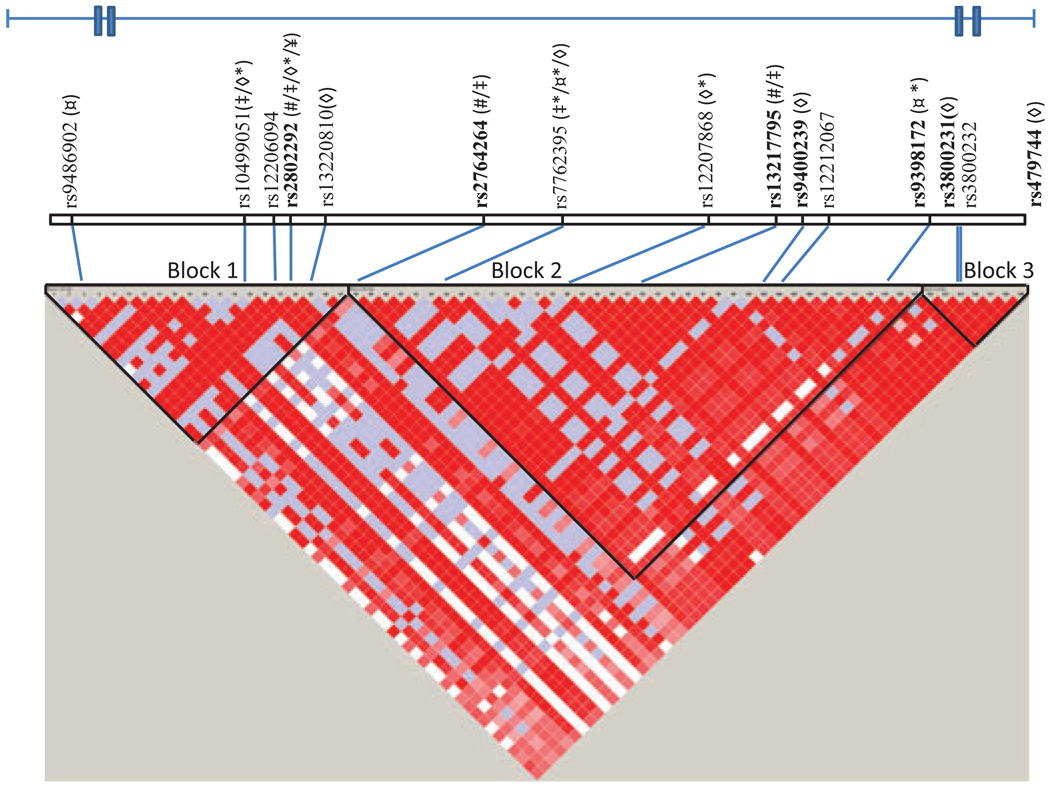

The FOXO3A SNPs investigated in this study and their relative positions and linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks are shown in Fig. 1. All 15 FOXO3A SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the control group (P > 0.05/15 SNPs) (data not shown). The genotype and allele frequencies of the 15 SNPs for middle-aged controls, nonagenarians, centenarians, and the combined group of oldest old (nonagenarians + centenarians) are listed in Supporting information Table S1. The frequencies of the rare alleles and rare genotypes generally tended to be higher in the oldest old when compared to the middle-aged controls. One exception was rs13220810, where the frequency of the most common allele and genotype was higher in the oldest old than in the controls. The frequencies for the nonagenarians were in general in between the frequencies for the middle-aged control group and the centenarians, supporting an increase in allele and genotype frequencies with age. Stratification by sex indicated that these tendencies were most pronounced for males (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

LD pattern in the FOXO3A region analyzed (position 108,982,719–109,113,664 on chromosome 6), displayed using the HaploView software, based on CEPH data downloaded from the HapMap data base (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/index.html.en). The following symbols are used for articles in which associations previously were reported: #: Willcox et al., ‡: Anselmi et al., ◇: Flachsbart et al., ¤: Pawlikowska et al., ¥: Li et al. *Reporting a SNP being in LD with the SNP investigated by us (R2 > 0.8). SNPs previously found to be associated with longevity after correction of multiple testing (in at least one study) are shown in bold.

FOXO3A SNPs and longevity – Case–control analysis

P-values for the allelic frequency case–control comparisons (PCCA) and the genotype frequency case–control comparisons (PCCG) between the middle-aged and oldest old cohort are listed in Supporting information Table S2; results for nominally significant effects (P < 0.05) are listed in Table 1. Nominally significant differences in allele frequencies were found for the males for five SNPs (rs12206094, rs13220810, rs2802292, rs3800231, and rs9486902), while with respect to genotype frequencies, nominally significantly differences were found for rs12206094, rs13220810, rs479744, rs7762395, and rs9486902 (both genders combined) and for rs12206094, rs13217795, rs13220810, rs2764264, rs2802292, rs3800231, rs479744, rs7762395, rs9398172, rs9400239, and rs9486902 (males only). No nominally significant effects (either by PCCA or PCCG) were found for the females.

Table 1.

Case-control association analysis of FOXO3A SNP allele and genotype frequencies with longevity when assuming the genotype (assumption free) model

| Males and females | Males | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N (oldest old) = 1089, N (controls) = 736 |

N (oldest old) = 313, N (controls) = 371 |

|||||

| No. | dbSNP ID | PCCG | PCCG | PCCA | OR | 95%CI |

| 1 | rs9486902 | 0.040† | 0.0083 | 0.0118 | 1.40 | 1.07–1.83 |

| 3 | rs12206094 | 0.032† | 0.0038 | 0.0076 | 1.38 | 1.08–1.75 |

| 4 | rs2802292 | >0.05 | 0.0211 | 0.0078 | 1.34 | 1.08–1.67 |

| 5 | rs13220810 | 0.046‡ | 0.0133 | 0.0223 | 0.75 | 0.58–0.96 |

| 6 | rs2764264 | >0.05 | 0.0078 | >0.05 | ||

| 7 | rs7762395 | 0.012 | 0.0031 | >0.05 | ||

| 9 | rs13217795 | >0.05 | 0.0215 | >0.05 | ||

| 10 | rs9400239 | >0.05 | 0.0098 | >0.05 | ||

| 12 | rs9398172 | >0.05 | 0.0435 | >0.05 | ||

| 13 | rs3800231 | >0.05 | 0.0373 | 0.0495 | 1.26 | 1.00–1.59 |

| 15 | rs479744 | 0.048 | 0.0026 | >0.05 | ||

Only nominally (P < 0.05) significant PCCA (P-values obtained from allele based case-control comparison) and PCCG (P-values obtained from genotype based case-control comparison) are included in the table.

N, number of individuals in group; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not analyzed (since no homozygotes (rare genotype) were found).

When assuming a recessive model.

When assuming a dominant model.

To correct for multiple testing, while taking into account the LD between the individual SNPs, permutation analysis was performed using the Plink software. Data found to be nominally significant, and the corresponding corrected values are listed in Supporting information Table S3, while the results holding for correction for multiple testing are listed in Table 2. Of the nominally significant findings (both genders combined), the PCCG values for rs7762395 did hold for correction for multiple testing, so did the PCCGs for rs12206094, rs13217795, rs13220810, rs2764264, rs479744, rs7762395, rs9400239, and rs9486902 when restricting to males. None of the nominally significant PCCA values remained significant.

Table 2.

Case-control association analysis of FOXO3A SNPs with longevity after correction for multiple testing (via permutation)

| Males and females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N (oldest old) = 1089, N (controls) = 736 |

N (oldest old) = 313, N (controls) = 371 |

||||

| PCCG uncorrected | PCCG corrected | PCCG uncorrected | PCCG corrected | ||

| Genotype model | |||||

| 3 | rs12206094 | >0.05 | 0.0038 | 0.0180 | |

| 6 | rs2764264 | >0.05 | 0.0078 | 0.0309 | |

| 7 | rs7762395 | 0.012 | 0.080 | 0.0031 | 0.0219 |

| 10 | rs9400239 | >0.05 | 0.0098 | 0.0320 | |

| 15 | rs479744 | 0.048 | 0.294 | 0.0026 | 0.0070 |

| Recessive model | |||||

| 1 | rs9486902 | 0.04 | 0.219 | 0.0060 | 0.0269 |

| 3 | rs12206094 | 0.032 | 0.186 | 0.0011 | 0.0029 |

| 6 | rs2764264 | >0.05 | 0.0020 | 0.0059 | |

| 7 | rs7762395 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.0006 | 0.0049 |

| 9 | rs13217795 | >0.05 | 0.0050 | 0.0249 | |

| 10 | rs9400239 | >0.05 | 0.0020 | 0.0069 | |

| 15 | rs479744 | 0.008 | 0.095 | 0.0006 | 0.0019 |

| Dominant model | |||||

| 5 | rs13220810 | 0.046 | 0.985 | 0.004 | 0.026 |

FOXO3A haplotypes and longevity - Case–control analysis

Three haplotype blocks were predicted in the gene region analyzed (see Fig. 1); block 1: rs9486902, rs10499051, rs12206094, rs2802292, and rs13220810, block 2: rs2764264, rs7762395, rs12207868, rs13217795, rs9400239, rs12212067, and rs9398172, and block 3: rs3800232. To test the association with longevity of these haplotype blocks in our sample, we used these haplotype definitions in Plink and found nominally significant differences for block 1 between the oldest old and the controls; haplotype CACTC, P = 0.03 and haplotype TACTT, P = 0.008 (both genders combined). To investigate the haplotype structure in more detail, the ‘sliding window’ feature in the Plink software was applied (using a window of three SNPs). Haplotype frequencies and P-values from the haplotype frequency based case-control comparison (PCCH) between the middle-aged and the oldest old are listed in Supporting information Table S4, whereas data being nominally significant and data passing correction of multiple testing are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Case-control association analysis of FOXO3A haplotypes with longevity. (A) males and females combined and (B) for males separately

| Window | SNPs in window | Haplotype | Uncorrected PCCH | Corrected PCCH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Females and males | Oldest old (N = 1089), N (controls) = 736 | |||

| WIN1 | rs9486902|rs10499051|rs12206094 | TAC | 0.0214 | 0.6068 |

| WIN2 | rs10499051|rs12206094|rs2802292 | ACG | 0.0421 | 0.9540 |

| WIN3 | rs12206094|rs2802292|rs13220810 | CTC | 0.0448 | 0.3646 |

| WIN4 | rs2802292|rs13220810|rs2764264 | TCT | 0.0390 | 0.3756 |

| (B) Males | Oldest old (N = 313), N (controls) = 371 | |||

| WIN1 | rs9486902|rs10499051|rs12206094 | CAT | 0.0478 | 0.4654 |

| TAC | 0.0052 | 0.0369 | ||

| CAC | 0.0008 | 0.0109 | ||

| WIN2 | rs10499051|rs12206094|rs2802292 | ATG | 0.0093 | 0.1918 |

| ACG | 0.0171 | 0.2687 | ||

| ACT | 0.0079 | 0.0629 | ||

| WIN3 | rs12206094|rs2802292|rs13220810 | CTC | 0.0125 | 0.1499 |

| TGT | 0.0056 | 0.1089 | ||

| WIN4 | rs2802292|rs13220810|rs2764264 | GTC | 0.0467 | 0.5644 |

| TCT | 0.0104 | 0.1189 | ||

| WIN5 | rs13220810|rs2764264|rs7762395 | CTG | 0.0226 | 0.2470 |

| WIN13 | rs3800231|rs3800232|rs479744 | GGC | 0.0357 | 0.3546 |

Only PCCHs (P-values obtained from haplotype based case-control comparison) being nominal significant (P < 0.05) are included in the table; data passing nominal significance are listed in columns named Uncorrected PCCH, whereas values corrected for multiple testing are listed in column named Corrected PCCH. Values passing correction by multiple testing are in bold.

N, number of individuals in group.

For both genders combined, haplotypes in the following windows were found to be nominally significant: window 1, 2, 3 and 4 (composed by SNPs rs9486902, rs10499051, rs12006094; rs10499051, rs12006094, rs2802292; rs12006094, rs2802292, rs132202810 and 2802292, rs132202810, rs2764264, respectively). When stratifying by gender, males showed, in addition to window 1–4, also significance for window 5 (rs13220810, rs2764264, and rs7762395) and 13 (rs3800231, rs3800232, and rs479744). As before, no effects were nominally significant for the females.

When correcting for multiple testing, one window (and two haplotypes) did hold for correction: window 1 (rs9486902, rs10499051, and rs12206094) haplotypes TAC and CAC were found to be significant for males only (see Table 3).

Case–control analysis of the centenarian group separately

One hundred and forty three of the 1089 1905 cohort members reached 100 years of age. Because the associations of FOXO3A SNPs with longevity have previously been reported to be most significant for centenarians (Flachsbart et al. 2009), we conducted the association studies for the centenarian group separately.

At the nominal significance level, most of the SNPs and haplotypes found to be nominally significant for the entire group of oldest old were also found to be significant for the centenarians (the PCCAs, PCCGs, and PCCHs for the centenarian group are listed in Supporting information Tables S2 and S4). When correcting for multiple testing (see Supporting information Table S3), only the PCCGs for rs772395 (both genders combined) and rs2764264 (males only) were replicated in the centenarians (P-values (corrected) = 0.016 and 0.036, respectively), whereas rs479744 was found to be significant for both genders combined (P-value (corrected) = 0.024) not in males only, as was found for the entire group of oldest old.

FOXO3A SNPs and longevity – Longitudinal study of an extinct cohort of oldest old

In addition to the case-control setup, we analyzed the follow-up survival data for oldest old (the results are listed in Supporting information Table S5). When conducting Cox regression, rs10499051, rs7762395 and rs9486902 were found to be nominally associated with longevity: rs10499051 (GG) Hazard rate (HR) = 0.496, P = 0.049, 95%CI = (0.247–0.997) for both genders combined; rs10499051 (GG) HR = 0.360, P = 0.023, 95%CI = (0.149–0.869) for females only; rs7762395 (AA) HR = 2.065, P = 0.009, 95%CI = (1.195–3.569) for males only; and rs9486902 (TT) HR = 1.739, P = 0.041; 95% CI = (1.022–2.951) for males only. When correcting for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction (P < 0.05/2*15 SNPs = 0.00166) it was, however, evident that none of the results remained significant.

Discussion

Numerous genes and variations have up until now been investigated for their contribution to human longevity, often demonstrating difficulties in replicating the initial findings, the only exception being the APOE gene (Christensen et al. 2006). However, more and more data points to the FOXO3A gene as the next convincing longevity candidate gene.

In this study, we investigated the possible association of variation in the FOXO3A gene with human longevity by covering the known common genetic variation of FOXO3A using tagging SNPs and analyzing the frequency data both by a case–control and by a longitudinal approach.

First, we conducted case–control analyses and found [as seen in previous studies (Anselmi et al. 2009; Flachsbart et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009; Pawlikowska et al. 2009; Willcox et al. 2008)] that the frequencies of the rare alleles and rare genotypes tended to be increased in the oldest old when compared to the younger controls (see Supporting information Table S1). One exception was the rs13220810 where the most frequent allele and most frequent genotype were increased in the oldest old. This was also observed by Flachsbart et al. (2009). Moreover, as reported by Flachsbart et al., we found that the allele and genotype frequencies for the nonagenarians in our cohort were generally in between the frequencies for the younger controls and for the centenarians, supporting the reported increase in allele and genotype frequencies with age.

When conducting association studies by comparing allele frequencies between the younger controls and oldest old, we found nominally significantly differences between the oldest old males and male controls for five SNPs (rs12206094, rs13220810, rs2802292, rs3800231, and rs9486902) and one SNP (rs479744) was significantly different between centenarians and controls when analyzing both genders combined (see Table 1 and Supporting information Table S2). Of these six SNPs, all except rs12206094, rs13220210 and rs9486902 have been found to be associated with longevity at the allele level (after correction of multiple testing) in at least one previous study (Anselmi et al. 2009; Flachsbart et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009; Pawlikowska et al. 2009; Willcox et al. 2008). rs12206094 and rs948602 have to our knowledge not been reported before, whereas rs13220210 has been found to be nominally associated (Flachsbart et al. 2009). The associations of the SNPs point in the same direction as in previously published studies (the SNPs show an increase in frequency of the rare allele in old age, except rs13220810 where the most frequent allele was increased in the oldest old (see Supporting information Table S1)) supporting the findings. The associations with respect to allele frequencies did in our study, however, not hold after correction for multiple testing (see Supporting information Table S3). The fact that at the allelic level, our data does not hold for the correction of multiple testing might simply be a matter of sample size and hence lack of power to detect an association. However, our sample size is at least as large as the previously published studies. Moreover, as seen below, assuming a recessive model for the genotype frequency data generally gives the lowest PGGC values, indicating that the association effect is most pronounced for the rare homozygote individuals, and hence that the association effect might be ‘masked’ when analyzing the allele frequencies (that is the heterozygotes might ‘dilute’ the effect).

When comparing genotype frequencies, all SNPs except rs10499051, rs12212067, and rs12207868 were found to be nominally significantly associated with longevity (rs3800232 was significant only for the centenarians), see Supporting information Tables S2 and Table 1. Nine of these 12 SNPs (excluding rs12206094, rs13220810, and rs3800232), or SNPs reported to be in pronounced LD at these SNPs, have previously been reported to be associated at the genotype level in at least one study (Anselmi et al. 2009; Flachsbart et al. 2009; Pawlikowska et al. 2009; Willcox et al. 2008).

After correction for multiple testing (see Supporting information Table S3 and Table 2), 8 of the 12 SNPs remained significant; two for both genders combined (rs479744 and rs7762395) and eight when analyzing males separately (rs12206094, rs13220810, rs13217795, rs2764264, rs479744, rs7762395, rs9486902, and rs9400239). Four of them (rs13217795, rs2764264, rs479744, and rs9400239) have previously been reported to be associated (after correction for multiple testing) in at least one study (Flachsbart et al. 2009; Willcox et al. 2008), whereas three SNPs (rs13220810, 7762395, rs9486902) have been shown to be nominally significant (Flachsbart et al. 2009; Pawlikowska et al. 2009). For all these SNPs (except rs13220810), the recessive model shows the lowest PGGC values, indicating that the association effects may be most pronounced for the rare homozygotes, possibly giving these individuals a survival advantage. The rs13220810, on the other hand, shows significance only when applying the dominant model, indicating that the positive effect of this SNP is most pronounced for individuals holding the common allele.

Flachsbart et al. (2009) and Li et al. (2009) reported significant findings in the populations composed of both genders. However, as seen in Table 1, 2, and 3, the differences in allele, genotype and haplotype frequencies in our cohorts were found to be most pronounced for males. The first study published on the association of SNPs in FOXO3A (Willcox et al. 2008) was conducted on an all male population and, moreover, five of six SNPs reported by Anselmi et al. (2009) were specific for males, whereas only one was specific for females, indicating a gender effect. Moreover, adding further support to a male-specific association in the case–control study we observe no associations in females even though the sample size is larger for females than for males (about 2.5-fold).

In addition to investigating differences in allele and genotype frequencies, we also investigated the possible haplotypes in FOXO3A. Again, we find that the effect is almost restricted to males (see Table 3 and Supporting information Table S4), and only for the TAC and CAC haplotypes of window 1 (composed by rs9486902, rs10499051, and rs12206094). The rs9486902 and rs12206094 were (as already described) found to be associated at the genotype frequency level, so the observation that the haplotypes including these two SNPs are found to be associated with longevity does not seem surprising.

Considering previous reporting (Flachsbart et al. 2009) of a most significant effect in centenarians, we analyzed the centenarians separately. We were, however, not able to replicate this finding; that is, we did not find additional SNPs to be associated with longevity or an increased effect of the SNPs in the centenarians (compared to the controls) as when comparing the entire group of oldest old to the controls. The SNP found to be associated in both genders in the entire group of oldest old (rs7762395) was replicated in the centenarians; however, only one (rs2764264) of the eight SNPs found in the males of the entire group of oldest old was replicated in the centenarians. The reason for the latter is probably the low sample size of male centenarians (N = 30) and hence lack of power to detect associations.

Finally, studies published so far on the association of FOXO3A SNPs with longevity have been case–control carried out by comparing the group of oldest old to a younger control group. To further investigate the association of FOXO3A SNPs with extreme survival, we investigated the 15 SNPs using longitudinal survival data for our homogenous cohort of oldest old. If fulfilling the proportional hazard assumptions, the Cox proportional hazard model was applied. Three SNPs were found to be nominally associated with longevity: rs10499051 in females and in both genders combined and rs7762395 and rs9486902 in males.

rs10499051 was not found to be significant in the case-control study. For rs7762395 and rs9486902, an increase in the rare genotype from middle age to old age was observed in the case–control study, which seems contradictory to the survival disadvantage during old age. The latter might, however, be explained by antagonistic pleiotropy, i.e., the two SNPs might have a positive effect on survival from middle age until old age, yet a negative effect during old age. However, none of these three SNPs hold significance after correction for multiple testing (via Bonferroni); hence, it might simply be chance findings and, hence, we cannot conclude of an association based on the longitudinal data.

In this study, we replicated some of the previous findings regarding an association of variation in the FOXO3A gene with human longevity using a case–control approach and, moreover, found novel SNPs to be associated. In addition, we report of a longitudinal analysis, which did, however, not show results holding for the correction of multiple testing. Hence, our findings add further evidence to the role of FOXO3A as a longevity candidate gene from younger ages to old age, yet not during old age.

Experimental procedures

Subjects

The oldest old individuals of our study (N = 1089) were participants in The Danish 1905 Cohort Study, which includes all Danes born in 1905 (Nybo et al. 2001). The cohort members were assessed for the first time in 1998, when they were 92–93 years of age. Survivors were subsequently assessed every second year through 2005, and vital status followed until January 1st 2010 or until death, whichever came first, resulting in a mean follow-up time for the survivors of 11.4 years (range: 11.2–11.6). Information on survival status was retrieved from the Danish Central Population Register, which is continuously updated (Pedersen et al. 2006). The younger control group (N = 736) of this study was randomly selected from the Study of Middle-Aged Danish Twins (Skytthe et al. 2002), which was initiated in 1998, when 2640 intact twin pairs from 22 consecutive birth years (1931–1952) were randomly selected via the Danish Central Person Registry. The participants have been followed longitudinally through different registers (including Statistics Denmark). The control group in the study presented here includes only one twin from each twin pair. Of the 736 individuals, 35 had died since the beginning of the survey in 1998, and only approximately 9% of the 736 individuals are expected to turn 93 years of age (this estimate is based on period life table data for the Danish population (http://www.mortality.org)). One potential confounder in association studies is population stratification, however, because of minimal immigration into both these cohorts, the cohorts must be considered to be genetically homogenous and population stratification to be minimal.

In the case–control part of the study presented here, we investigate the association of FOXO3A SNPs in the controls when compared to the entire group of oldest old (N = 1089), as well as of those individuals from the 1905 cohort who became centenarians (N = 143). The reason for doing so is that the association of FOXO3A SNPs with longevity has previously been reported to be most pronounced for centenarians (Flachsbart et al. 2009).

Both surveys included multidimensional face-to-face interviews, assessment of functional and cognitive abilities and DNA sampling. Permission to collect blood samples and usage of register-based information was granted by The Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics.

Selection of chromosome region and tagging SNPs

The genomic region investigated in this study is position 108,982,719–109,113,664 of chromosome 6, which corresponds to FOXO3A and 5000 base pair (bp) upstream and 1000 bp down stream (NCBI assemble 36). Data about variation in this gene region were obtained through the HapMap consortium database (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/index.html.en) for the CEPH (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe (CEPH) (CEU)) cohort, using the HapMap Data Rel 23a/phase II Mar08, on NCBI B36 assembly, dbSNP b 126 criteria. Genotype SNP data were analyzed using the HaploView software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/haploview, Barrett et al. (2005)) to choose tagging SNPs covering 100% of the known common genetic variation in FOXO3A (‘pair wise tagging only’, R2 = 0.8, LOD = 3 and a minimum distance between SNPs = 60 bp criteria were used). All tagging and candidate SNPs included in this study have a minor allele frequency (MAF) of at least 5%.

Genotyping

DNA was isolated from blood spot samples using the QIAamp DNA Mini and Micro Kits (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany). Genotyping of the 15 FOXO3A SNPs was performed using the Illumina GoldenGate platform (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) and data cleanup was performed according to Illumina Inc’s recommendations (http://www.illumina.com/documents/products/technotes/technote_infinium_genotyping_data_analysis.pdf). Finally, 24 and 48 DNA samples were included twice in the GoldenGate assay to investigate the intra-plate and the inter-plate reproducibility. Data showed an intra-plate reproducibility of 99.4% (using 24 samples) and an inter-plate reproducibility of 96.8% (using 48 samples).

Statistics

The Plink statistical program (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink, (Purcell et al. 2007)) was used for investigating genotype, allele, and haplotype frequencies in the different groups and for association studies using χ2 test statistics. P-values were obtained for allelic case–control comparison (PCCA), for genotypic case–control comparison (PCCG), and for haplotypic case–control comparison (PCCH). Analysis of differences in genotype frequencies was carried out by assuming firstly a genotype (assumption free) model and secondly recessive and dominant models. Haplotypes were investigated using the ‘Sliding window’ application in Plink, by setting the window at three SNPs sliding along the 15 SNPs in the order defined by their positions on chromosome 6.

The longitudinal survival data analysis on the oldest old was conducted by using the STATA 10.0 statistical program (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) for estimating the mortality risk using the Cox proportional hazard model.

A nominal significance level was set at P < 0.05, and the permutation application in Plink was used for correcting for multiple testing of the allele, genotype, and haplotype data (applying max(T) permutation mode set at 1000 permutations), while for the Cox regression analysis, a Bonferroni correction level at P = 0.05/2.15 SNPs = 0.00166 was used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Max-Planck Institute for Demographic Research, (Rostock, Germany), the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG08761), the INTERREG 4 A programme Syddanmark-Schleswig-K.E.R.N (by EU funds from the European Regional Development Fund), the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Foundation, the Augustinus Foundation, the Brødrene Hartmann Foundation, the King Christian the 10th foundation, and the Einer Willumsens Mindelegat Foundation. The Danish Aging Research Center is supported by a grant from the VELUX Foundation. Susanne Knudsen, Steen Gregersen, Ulla Munk and Shuxia Li are thanked for excellent technical work.

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.S., S.D., K.C., M.M., L.C., T.S., V.A.B.: Generating the conception of the study and the study design; M.S.: Acquisition of data, conduction of data analysis, and interpretation of data. Drafting the manuscript; S.D.: Contribution to the acquisition of data; K.C., M.M: Interpretation of data. L.C.: Acquisition of data and interpretation of data. Authors have revised the manuscript and given their final approval.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Genotype and allele frequencies (in %) of the FOXO3A SNPs in the control, nonagenarian, centenarian and the combined oldest old (nonagenarians + centenarians) groups for both genders combined and males and females separately.

Table S2 Case–control association analysis of FOXO3A SNP with longevity assuming the genotype (assumption free) model.

Table S3 Correction for multiple testing via permutation of SNPs found to have nominally significantly (P < 0.05) different frequencies between the middle-aged controls and the oldest old.

Table S4 Case–control association analysis of FOXO3A haplotypes with longevity.

Table S5 Longitudinal association analysis of FOXO3A SNPs with longevity. Mortality risk estimates (Hazard rates, estimated using the Cox proportional hazard model) for both genders combined and males and females separately.

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer-reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

References

- Anselmi CV, Malovini A, Roncarati R, Novelli V, Villa F, Condorelli G, Bellazzi R, Puca AA. Association of the FOXO3A locus with extreme longevity in a southern Italian centenarian study. Rejuvenation. Res. 2009;12:95–104. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman M, Blauw GJ, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Brandt BW, Westendorp RG, Slagboom PE. Chromosome 4q25, microsomal transfer protein gene, and human longevity: novel data and a meta-analysis of association studies. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006;61:355–362. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Johnson TE, Vaupel JW. The quest for genetic determinants of human longevity: challenges and insights. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:436–448. doi: 10.1038/nrg1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flachsbart F, Caliebe A, Kleindorp R, Blanche H, von Eller-Eberstein H, Nikolaus S, Schreiber S, Nebel A. Association of FOXO3A variation with human longevity confirmed in German centenarians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2700–2705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809594106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskind AM, McGue M, Holm NV, Sorensen TI, Harvald B, Vaupel JW. The heritability of human longevity: a population-based study of 2872 Danish twin pairs born 1870–1900. Hum. Genet. 1996;97:319–323. doi: 10.1007/BF02185763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmborg JVb, Iachine I, Skytthe A, Vaupel JW, McGue M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Pedersen NL, Christensen K. Genetic influence on human lifespan and longevity. Hum. Genet. 2006;119:312–321. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0144-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang WJ, Cao H, Lu J, Wu C, Hu FY, Guo J, Zhao L, Yang F, Zhang YX, Li W, Zheng GY, Cui H, Chen X, Zhu Z, He H, Dong B, Mo X, Zeng Y, Tian XL. Genetic association of FOXO1A and FOXO3A with longevity trait in Han Chinese populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:4897–4904. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybo H, Gaist D, Jeune B, Bathum L, McGue M, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. The Danish 1905 cohort: a genetic-epidemiological nationwide survey. J. Aging Health. 2001;13:32–46. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlikowska L, Hu D, Huntsman S, Sung A, Chu C, Chen J, Joyner AH, Schork NJ, Hsueh WC, Reiner AP, Psaty BM, Atzmon G, Barzilai N, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Kwok PY, Ziv E. Association of common genetic variation in the insulin/IGF1 signaling pathway with human longevity. Aging Cell. 2009;8:460–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan. Med. Bull. 2006;53:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:3559–3575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skytthe A, Kyvik K, Holm NV, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. The Danish Twin Registry: 127 birth cohorts of twins. Twin.Res. 2002;5:352–357. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox BJ, Donlon TA, He Q, Chen R, Grove JS, Yano K, Masaki KH, Wilcox DC, Rodriguez B, Curb JD. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:13987–13992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.