Abstract

CLEC16A, a putative immunoreceptor, was recently established as a susceptibility locus for type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Subsequently, associations between CLEC16A and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Addison’s disease and Crohn’s disease have been reported. A large comprehensive and independent investigation of CLEC16A variation in RA was pursued. This study tested 251 CLEC16A single-nucleotide polymorphisms in 2542 RA cases (85% anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) positive) and 2210 controls (N = 4752). All individuals were of European ancestry, as determined by ancestry informative genetic markers. No evidence for significant association between CLEC16A variation and RA was observed. This is the first study to fully characterize common genetic variation in CLEC16A including assessment of haplotypes and gender-specific effects. The previously reported association between RA and rs6498169 was not replicated. Results show that CLEC16A does not have a prominent function in susceptibility to anti-CCP-positive RA.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, anti-CCP antibodies, autoimmunity, CLEC16A, KIAA0350

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common systemic autoimmune disease with a prevalence of 1%.1 This chronic inflammatory disease can cause substantial disability from the erosive and deforming processes in joints, and is associated with increased mortality.2 RA has a strong genetic component, as shown by twin and other family studies; however, the etiology is unknown.3 Major histocompatibility complex genes, particularly HLA class II, are strongly associated with risk of developing RA. However, major histocompatibility complex genes only account for a portion of the genetic risk. Several non-major histocompatibility complex genes have recently been associated with risk for RA, including PTPN22, STAT4 and TNFAIP3.4–6 Results from recent genome-wide association (GWA) studies underscore the overlap of replicated findings across complex diseases, including autoimmune conditions.7,8 Variants within some confirmed genetic risk loci for RA also confer risk for other autoimmune diseases. These include CTLA4 in type I diabetes (T1D), IL-2 in T1D and Celiac disease, PTPN22 in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), T1D and autoimmune thyroid disease, STAT4 in SLE and TNFAIP3 in SLE, T1D, Celiac disease and Crohn’s disease.5,9–19

The C-type lectin domain family 16, member A gene (CLEC16A, previously called KIAA0350) spans 237.7 kb and encodes a sugar-binding receptor that contains a putative immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif.10 C-type lectin receptors can be expressed on dendritic cells to distinguish between self and non-self glycoproteins, and may be involved in immune activation and peripheral tolerance.20,21 These sugar-binding receptors have been shown to be important in multiple animal models for RA.22–25 For example, in rats, C-type lectin-like receptors are encoded by the antigen-presenting lectin-like receptor gene complex (APLEC), which have been shown to influence susceptibility to arthritis (oil-, collagen-, squalene- and pristine-induced), auto-immune phenotypes (autoantibody levels) and clinical phenotypes (day of disease onset, maximal severity, severity over time, body weight loss, arthritis symptoms).24 The effect of APLEC variation on susceptibility to arthritis and clinical phenotypes varied by gender.24

Recently, GWA studies have identified the sugar-binding receptor gene CLEC16A as a novel risk locus for T1D and MS, and this association has since been replicated in independent samples.10,26–31 CLEC16A is located on 16p13, a region that has been implicated in RA linkage studies.32 The purpose of this study was to perform a comprehensive haplotype-based investigation of CLEC16A as a candidate RA gene. This study sample consisted of 682 RA cases and 752 controls collected by the North American RA Consortium (RA1), 1860 RA cases collected by the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC) RA Group in the UK and 1458 controls collected by the WTCCC from the UK Blood Services (RA2) (total N = 4752) (Table 1).

Table 1.

RA study cohorts used for CLEC16A analyses

| RA1 | Controls | RA2 | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 682 | 752 | 1860 | 1458 |

| Site | NA | NA | UK | UK |

| Mean age (years) | 56.2 | 48.5 | — | — |

| Age range (years) | 21–87 | 30–82 | — | <70 |

| Female, N (%) | 503 (73.7) | 525 (69.8) | 1390 (74.7) | 753 (51.6) |

| Mean age-at-onset (years) | 45.7 | — | ||

| Rheumatoid factor positive, N (%) | 580 (85) | 1310 (83.9) | ||

| 0 | 15 (2.3) | 401 (53.3) | 286 (20.7) | |

| 1 | 362 (56.5) | 301 (40) | 680 (49.2) | |

| 2 | 264 (41.2) | 50 (6.6) | 416 (30.1) | |

| Erosions, N (%) | 211 (66.6) | — | ||

| Anti-CCP positive, N (%) | 681 (100) | 884 (79.8) |

RA cases met the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for RA.45 RA2 controls were a subset of the WTCCC T1D GWA study controls.19 RA1 controls were frequency matched by age and gender to the cases. RA2 controls were frequency matched by geographical region and gender to the 1958 Birth cohort (which included all births in England, Wales and Scotland, during one week in 1958) so as to be nationally representative. On the basis of the available genetic ancestry data for all individuals, and to apply the most stringent criteria possible for genetic analysis of CLEC16A, only RA1 subjects with ≥90% Northern European ancestry and RA2 subjects with European ancestry were analyzed. European ancestry was estimated in RA1 using a Bayesian clustering algorithm (Structure v. 2.0, Oxford, UK) and data for 112 European and 246 Northern European ancestry informative markers.46,47 For RA2, European ancestry was estimated by principal components analysis.19

HLA-DRB1*0101, *0102, *0104, *0401, *0404, *0405, *0408, *0413, *0416, *1001 alleles.

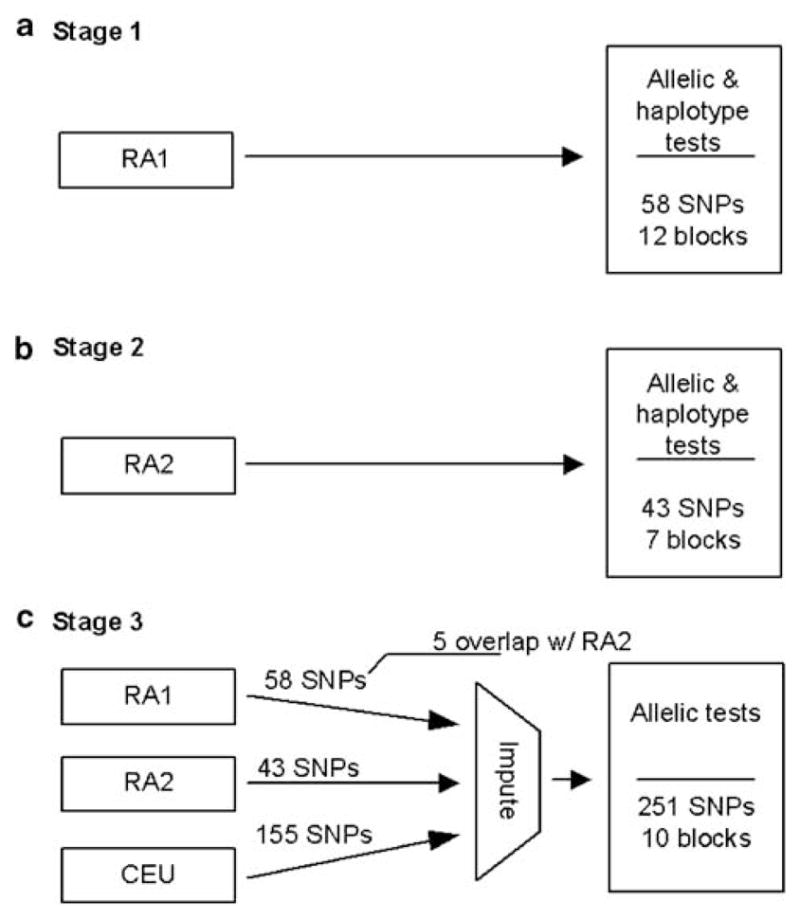

We conducted allelic tests of association for 58 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and global haplotype tests (12 haplotype blocks encompassing 53 SNPs) in 682 anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-positive (anti-CCP-positive) RA cases and 752 controls (N = 1434 (RA1)) (Figure 1). All results were negative after correcting for multiple testing (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). Next, we conducted allelic tests of 43 SNPs and global haplotype tests (7 haplotype blocks encompassing 37 SNPs) in the second RA data set composed of 1860 RA cases and 1458 controls (N = 3318 (RA2)). No evidence for association was present (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, allelic tests of 251 imputed SNPs within CLEC16A derived for the combined RA sample (2542 cases and 2210 controls, total N = 4752 (RA1 + RA2)) revealed no evidence for disease association (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1).

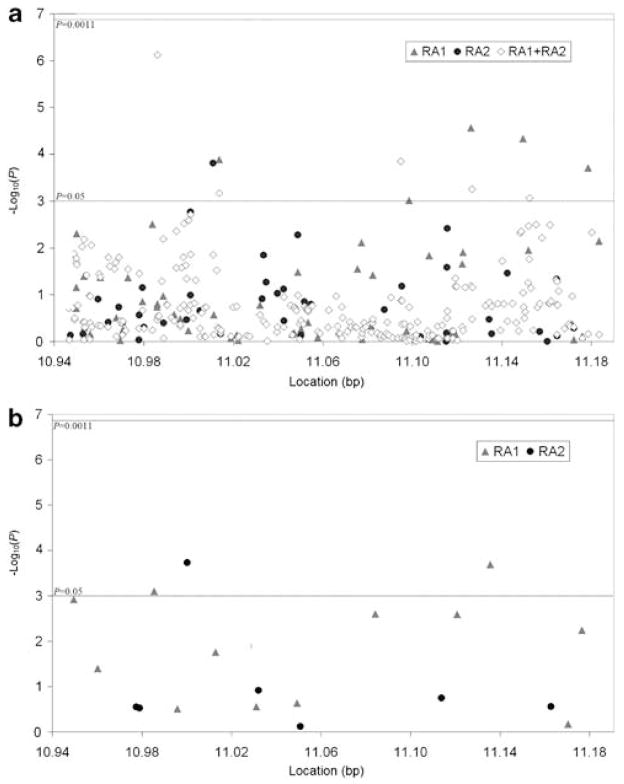

Figure 1.

Schematic of our analysis strategy in stages (a) 1, (b) 2 and (c) 3. Previous GWA studies provided genotyping data for 64 CLEC16A single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in RA1 derived from the Illumina HumanHap550 Genotyping BeadChip (San Diego, CA, USA) at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research and 49 CLEC16A SNPs in RA2 from the Affymetrix GeneChips Mapping 500 K Array Set (Santa Clara, CA, USA) as previously described.19,48,49 Three SNPs in RA1 and six SNPs in RA2 were excluded from analysis due to low minor allele frequency (MAF) (<0.01). Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was examined in controls separately for each cohort using the exact test (PLINK v. 1.05, Boston, MA, USA).50,51 Three SNPs from RA1 with evidence for deviation from HWE in the controls (P<0.001) were omitted from further analyses. Sufficient power for this study was confirmed with PGA v. 2.0 (Bethesda, MD, USA) (two-sided α = 0.05).52 Haplotype blocks were estimated in RA1 and RA2 controls and CEU separately (Haploview v. 4.1, Cambridge, MA, USA).53 Percent of CLEC16A variation captured was based on r2≥0.8 in CEU using two- and three-marker haplotypes (Haploview).

Figure 2.

P-values from (a) allelic and (b) haplotype tests of CLEC16A single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Allelic association was tested by creating 2 × 2 contingency tables and estimating odds ratios (ORs) with Fisher’s exact test (PLINK). Haplotypes were estimated with the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm (Haploview). Maximum likelihood estimates of haplotype probabilities were computed with the EM algorithm and score statistics were used for global haplotype association tests, assuming a dominant genetic model (HaploStats v. 1.4.3, Rochester, MN, USA; R v. 2.6, Vienna, AT).54 Haplotypes with inferred frequencies <5% were excluded. A significance threshold of P = 1.1 × 10−3 was set using a Bonferroni correction for the number of CLEC16A haplotype blocks (10) and SNPs that were not located in haplotype blocks (34), based on CEU. Empirical P-values based on 10 000 simulations were reported for all allelic and haplotype tests. To conduct a combined analysis of RA1 + RA2, we used a hidden Markov Model based algorithm to impute genotypes for 38 SNPs in RA1, 53 SNPs in RA2 and 171 SNPs in RA1 + RA2 (IMPUTE v. 0.5.0, Oxford, UK).55 The imputation was based on two 500 kb regions flanking each side of CLEC16A, using CEU as the reference and an r2 threshold of 0.8. Imputed genotypes with <90% probability were omitted. After omitting, 12 SNPs with evidence for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the controls and 4 SNPs with low minor allele frequency (MAF) from further analyses, 251 SNPs in RA1 + RA2 were tested for allelic association.

The six CLEC16A SNPs shown to be associated with T1D and/or MS are intronic and were either genotyped or tagged (r2>0.95 based on the Caucasian HapMap population (CEU)) in this study. Similar to this study, candidate gene investigations of CLEC16A in Grave’s disease, Celiac disease and ulcerative colitis have been negative, but associations have been reported with Addison’s disease, Crohn’s disease and for RA in other data sets.10,29,33–36 A case–control study by Martinez et al.29 examined three CLEC16A SNPs and reported that rs6498169*G, a variant associated with MS, was over-represented in RA cases (38%) compared to controls (32%) (P = 8 × 10−3, odds ratio (OR) = 1.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.06–1.51). Although our study was well powered to detect such an effect size, with 80% power to detect an OR as low as 1.13, the association between RA and rs6498169 was not replicated. The rs6498169*G allele frequency did not differ between RA cases (33.6%) and healthy controls in this study (32.9%) (P = 0.45, OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.95–1.11).

It is also important to note that recent studies have revealed the presence of different major histocompatibility complex associations in anti-CCP-positive and anti-CCP-negative RA cases when considered separately.37–39 It is possible that this phenotypic difference may also be important for other RA genetic susceptibility loci. The well-established PTPN22 RA locus appears to be associated only with anti-CCP-positive RA, although some studies have reported association with both anti-CCP-positive and anti-CCP-negative RA.40–43 Anti-CCP autoantibodies and shared epitope alleles are also markers for increased RA severity, particularly when both are present.44 In this study, 85% of RA cases were anti-CCP positive, compared to only 50% in the Martinez et al. study. This difference may have contributed to the observed disparity between results. Indeed, Skinningsrud et al.36 have recently examined three CLEC16A SNPs and reported that the rs6498169*G variant was over-represented in anti-CCP-negative RA cases (44%) compared to anti-CCP-positive RA cases (37.7%) (P = 0.016, OR = 1.3, 95% CI = 1.05–1.61) and controls (35.9%) (P = 2 × 10−4, OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.18–1.68). Martinez et al. did not observe differences between cases and controls after stratifying for anti-CCP status or presence/absence of shared epitope alleles, but this may be due to a lack of statistical power. Although all of our RA1 cases were anti-CCP positive, only 80% of RA2 cases were anti-CCP positive and this information was not publicly available for the RA2 cases. Therefore, we were not able to stratify RA2 or RA1 + RA2 by anti-CCP status for analyses of CLEC16A SNPs.

Because animal models suggest that C-type lectin receptor genes may have gender-specific effects on autoimmunity, we conducted gender-stratified allelic tests and gender-adjusted global haplotype tests of CLEC16A within RA1 and RA2.24 The rs3960630 A variant was underrepresented in female RA1 cases (20%) compared to female controls (25%) (OR = 0.71, 95% CI = 0.59–0.86, P = 4 × 10−4). This intronic SNP was not present in or captured by RA2 data and therefore could not be tested in the larger combined data set. Given the number of multiple tests performed, these results should be interpreted with caution. Results did not differ when global haplotype tests were adjusted by gender (data not shown). Animal models of RA also indicate that it may be worthwhile to stratify cases by clinical phenotypes in future genetic studies of C-type lectin receptors and autoimmunity.24

Although rare variants in CLEC16A were not directly investigated here, for the first time all common genetic variation within CLEC16A was interrogated for a function in RA susceptibility. Even without imputed genotypes, the RA1 data set (N = 58 SNPs) captured 93%, RA2 (N = 43 SNPs) captured 80% and both data sets combined (N = 96 SNPs) captured 96% of the common variation based on CEU data from HapMap (see Figure 2 legend). The data used in this study were taken from GWA studies that did not identify CLEC16A as a risk locus for RA based on stringent genome-wide significance. A focused candidate gene study that captures a larger portion of genetic variation compared to initial GWA studies is a useful and complementary strategy.

In conclusion, this is the first candidate gene study of CLEC16A to fully characterize common genetic variation in CLEC16A, including assessment of haplotypes and gender-specific effects. We did not replicate the association between RA and rs6498169 reported by other studies. Results convincingly show that variation within CLEC16A does not have a prominent function in susceptibility to anti-CCP-positive RA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Farren BS Briggs, Benjamin A Goldstein, Alan Hubbard and Ira Tager for helpful discussion, as well as study participants. This work was supported by an Abbott Graduate Student Achievement Award (ACR REF), Grants R01 AI065841, R01 AI059829 and F31 AI075609 (NIH/NIAID), and Grants RO1 AR44422, NO1 AR22263, R01 AR050267 and K24 AR02175 (NIH/NIAMS). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NIAID or NIAMS. This study makes use of data generated by the WTCCC; a full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available at www.wtccc.org.uk, and funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 076113. These studies were performed in part in the General Clinical Research Center, Moffitt Hospital, University of California, San Francisco, with funds provided by the National Center for Research Resources, 5 M01 RR-00079, US Public Health Service.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Genes and Immunity website (http://www.nature.com/gene)

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Doran MF, Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, et al. Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:54–58. doi: 10.1002/art.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacGregor AJ, Snieder H, Rigby AS, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Aho K, et al. Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:30–37. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<30::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begovich AB, Carlton VE, Honigberg LA, Schrodi SJ, Chokkalingam AP, Alexander HC, et al. A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:330–337. doi: 10.1086/422827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW, et al. STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plenge RM, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Price AL, de Bakker PIW, Maller J, et al. Two independent alleles at 6q23 associated with risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1477–1482. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lettre G, Rioux JD. Autoimmune diseases: insights from genome-wide association studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17 (R2):R116–R121. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueda H, Howson JM, Esposito L, Heward J, Snook H, Chamberlain G, et al. Association of the T-cell regulatory gene CTLA4 with susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Nature. 2003;423:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Downes K, Plagnol V, et al. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:857–864. doi: 10.1038/ng2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, Gwilliam R, Zhernakova A, Inouye M, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nat Genet. 2007;39:827–829. doi: 10.1038/ng2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyogoku C, Langefeld CD, Ortmann WA, Lee A, Selby S, Carlton VE, et al. Genetic association of the R620W polymorphism of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 with human SLE. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:504–507. doi: 10.1086/423790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bottini N, Musumeci L, Alonso A, Rahmouni S, Nika K, Rostamkhani M, et al. A functional variant of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase is associated with type I diabetes. Nat Genet. 2004;36:337–338. doi: 10.1038/ng1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Criswell LA, Pfeiffer KA, Lum RF, Gonzales B, Novitzke J, Kern M, et al. Analysis of families in the multiple autoimmune disease genetics consortium (MADGC) collection: the PTPN22 620W allele associates with multiple autoimmune phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:561–571. doi: 10.1086/429096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musone SL, Taylor KE, Lu TT, Nititham J, Ferreira RC, Ortmann W, et al. Multiple polymorphisms in the TNFAIP3 region are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1062–1064. doi: 10.1038/ng.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Hackett R, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fung EY, Smyth DJ, Howson JM, Cooper JD, Walker NM, Stevens H, et al. Analysis of 17 autoimmune disease-associated variants in type 1 diabetes identifies 6q23/TNFAIP3 as a susceptibility locus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:188–191. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trynka G, Zhernakova A, Romanos J, Franke L, Hunt KA, Turner G, et al. Coeliac disease-associated risk variants in TNFAIP3 and REL implicate altered NF-kappaB signalling. Gut. 2009;58:1078–1083. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.169052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14 000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates EE, Fournier N, Garcia E, Valladeau J, Durand I, Pin JJ, et al. APCs express DCIR, a novel C-type lectin surface receptor containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif. J Immunol. 1999;163:1973–1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geijtenbeek TB, van Vliet SJ, Engering A, t Hart BA, van Kooyk Y. Self- and nonself-recognition by C-type lectins on dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:33–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujikado N, Saijo S, Iwakura Y. Identification of arthritis-related gene clusters by microarray analysis of two independent mouse models for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R100. doi: 10.1186/ar1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujikado N, Saijo S, Yonezawa T, Shimamori K, Ishii A, Sugai S, et al. Dcir deficiency causes development of autoimmune diseases in mice due to excess expansion of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nm1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo JP, Backdahl L, Marta M, Mathsson L, Ronnelid J, Lorentzen JC. Profound and paradoxical impact on arthritis and autoimmunity of the rat antigen-presenting lectin-like receptor complex. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1343–1353. doi: 10.1002/art.23434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorentzen JC, Flornes L, Eklow C, Backdahl L, Ribbhammar U, Guo JP, et al. Association of arthritis with a gene complex encoding C-type lectin-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2620–2632. doi: 10.1002/art.22813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakonarson H, Grant SFA, Bradfield JP, Marchand L, Kim CE, Glessner JT, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature. 2007;448:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, et al. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zoledziewska M, Costa G, Pitzalis M, Cocco E, Melis C, Moi L, et al. Variation within the CLEC16A gene shows consistent disease association with both multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes in Sardinia. Genes Immun. 2009;10:15–17. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez A, Perdigones N, Cenit M, Espino L, Varade J, Lamas JR, et al. Chromosomal region 16p13: further evidence of increased predisposition to immune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;69:309–311. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.098376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrett JC, Clayton DG, Concannon P, Akolkar B, Cooper JD, Erlich HA, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:703–707. doi: 10.1038/ng.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubio JP, Stankovich J, Field J, Tubridy N, Marriott M, Chapman C, et al. Replication of KIAA0350, IL2RA, RPL5 and CD58 as multiple sclerosis susceptibility genes in Australians. Genes Immun. 2008;9:624–630. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etzel CJ, Chen WV, Shepard N, Jawaheer D, Cornelis F, Seldin MF, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis for rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Genet. 2006;119:634–641. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dema B, Martinez A, Fernandez-Arquero M, Maluenda C, Polanco I, Angeles Figueredo M, et al. Autoimmune disease association signals in CIITA and KIAA0350 are not involved in celiac disease susceptibility. Tissue Antigens. 2009;73:326–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marquez A, Varade J, Robledo G, Martinez A, Mendoza JL, Taxonera C, et al. Specific association of a CLEC16A/KIAA0350 polymorphism with NOD2/CARD15(−) Crohn’s disease patients. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1304–1308. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skinningsrud B, Husebye ES, Pearce SH, McDonald DO, Brandal K, Wolff AB, et al. Polymorphisms in CLEC16A and CIITA at 16p13 are associated with primary adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3310–3317. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skinningsrud B, Lie BA, Husebye ES, Kvien TK, Forre O, Flato B, et al. A CLEC16A variant confers risk for juvenile idiopathic arthritis and anti-CCP negative rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.114934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding B, Padyukov L, Lundstrom E, Seielstad M, Plenge RM, Oksenberg JR, et al. Different patterns of associations with anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive and anti-citrullinated protein antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis in the extended major histocompatibility complex region. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:30–38. doi: 10.1002/art.24135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irigoyen P, Lee AT, Wener MH, Li W, Kern M, Batliwalla F, et al. Regulation of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: contrasting effects of HLA-DR3 and the shared epitope alleles. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3813–3818. doi: 10.1002/art.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verpoort KN, van Gaalen FA, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Schreuder GM, Breedveld FC, Huizinga TW, et al. Association of HLA-DR3 with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3058–3062. doi: 10.1002/art.21302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wesoly J, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Toes RE, Chokkalingam AP, Carlton VE, Begovich AB, et al. Association of the PTPN22 C1858T single-nucleotide polymorphism with rheumatoid arthritis phenotypes in an inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2948–2950. doi: 10.1002/art.21294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kallberg H, Padyukov L, Plenge RM, Ronnelid J, Gregersen PK, van der Helm-van Mil AH, et al. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions involving HLA-DRB1, PTPN22, and smoking in two subsets of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:867–875. doi: 10.1086/516736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierer M, Kaltenhauser S, Arnold S, Wahle M, Baerwald C, Hantzschel H, et al. Association of PTPN22 1858 single-nucleotide polymorphism with rheumatoid arthritis in a German cohort: higher frequency of the risk allele in male compared to female patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R75. doi: 10.1186/ar1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farago B, Talian GC, Komlosi K, Nagy G, Berki T, Gyetvai A, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase gene C1858T allele confers risk for rheumatoid arthritis in Hungarian subjects. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:793–796. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0771-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Gaalen FA, Van Aken J, Huizinga TW, Schreuder GM, Breedveld FC, Zanelli E, et al. Association between HLA class II genes and autoantibodies to cyclic citrullinated peptides (CCPs) influences the severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2113–2121. doi: 10.1002/art.20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian C, Plenge RM, Ransom M, Lee A, Villoslada P, Selmi C, et al. Analysis and application of European genetic substructure using 300K SNP information. PLoS Genetics. 2008;4:29–39. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B, et al. TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR. A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:887–893. doi: 10.1086/429864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Menashe I, Rosenberg PS, Chen BE. PGA: power calculator for case-control genetic association analyses. BMC Genet. 2008;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:425–434. doi: 10.1086/338688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.