Abstract

There has been significant progress in our knowledge about the relationship between infectious disease and the immune system in relation to asthma, but many unanswered questions still remain. Respiratory tract infections such as those caused by respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus during the first 2 years of life are still clearly associated with later wheezing and asthma, but the mechanism has not been completely worked out. Is there an “infectious march” triggered by infection in infancy that progresses to disease pathology or are infants who contract respiratory infections predisposed to developing asthma? This review focuses on the common themes in the interaction between microbes and the immune system, and presents a critical appraisal of the evidence to date. The various mechanisms whereby microbes alter the immune response and how this might influence asthma are discussed along with new and promising clinical practices for prevention and therapy. Recent advances in using sensitive polymerase chain reaction detection methods have allowed more rigorous testing of the causality hypothesis of virus infection leading to asthma, but the evidence is still equivocal. Various exceptions and inconsistencies in the clinical trials are discussed in light of new guidelines for subject inclusion/exclusion in hopes of providing some standardization. Despite past failures in vaccination and disappointing results of some clinical trials, the new strategies for prophylaxis including RNA interference and targeted delivery of microbicides offer a large dose of hope to a world suffering from an increasing incidence of asthma as well as a huge burden of health care cost and loss of quality of life.

Keywords: Infection, Virus, Bacteria, Asthma, Inflammation, Signaling, Mechanism

Like asthma itself, the association between respiratory infections and the inflammatory immune response is complex and incompletely understood. One can clearly see the effects of infections on wheezing, asthma inception, and exacerbations, but dissecting out the mechanistic details is the challenge confronting research in this decade. As always, it is hoped that a more complete understanding of the cells, cytokines, and signaling pathways involved, along with knowledge of the temporal progression of events and the role of regulatory factors such as microRNAs, will lead to more effective treatments, individualized to the patient.

Asthma afflicts more than 300 million individuals of all ages and ethnic groups, and results in approximately 250,000 deaths worldwide. More than 7 million children younger than 18 years have been diagnosed with asthma in the United States alone.1 In 2003, asthma-related hospitalizations neared 500,000 in the United States and the annual direct medical expenses associated with asthma care were $12.7 to $15.6 billion.2, 3 According to a cross-sectional international study conducted from 2002 to 2003 by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), the prevalence of asthma symptoms reported in the 6- to 7-year-old age group increased significantly among 59% of the centers examined4; furthermore, the national surveillance report in 2007 identified a substantial increase in asthma attacks within the past 2 decades.5

In addition to the direct impact that asthma has on quality of life and health care costs among young populations, there is growing evidence for the existence of an asthmatic phenotype associated with increased susceptibility to respiratory tract infections (RIs) attributed to virus, particularly human rhinovirus (HRV) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).6, 7 Other respiratory viruses and certain atypical bacteria are also suspected of playing a part in airway inflammation and asthma pathogenesis.8, 9 In this article, the authors explore the mechanisms by which viral and bacterial infections trigger asthma exacerbations, look for similarities and differences, and discuss how some new therapeutic strategies are attempting to target these areas.

Correlations between respiratory tract infection and wheezy bronchitis and asthma

Advances in biotechnology in the 1990s have now provided diagnosticians with ultrasensitive methods such as quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for identifying respiratory tract pathogens.10, 11 Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA)12 and high-throughput microarray chips, such as the Virochip,13 have increased data collection by orders of magnitude. Early epidemiologic studies frequently suffered from variable viral isolation rates14 and had to rely on tissue culture and serology for the detection of HRV, RSV, human influenza virus (IF), human parainfluenzavirus (HPIV), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), enterovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae,15 pneumococcal strains, and Haemophilus influenzae.16, 17 Microbial pathogens are usually more abundant in nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) from children and adults with active asthma.17, 18, 19 Due to technological limitations and variable clinical criteria for diagnosing asthma,14 observations from some early studies showed only weak correlations between respiratory infections and wheezy bronchitis and asthma.20 Total viral isolation rates of RSV, HRV, and HPIV in children younger than 15 years were as low as 14.2% (38/267 children)18 to as high as 45% (22/72 children)17 during hospital admissions or reported asthma attacks. Despite the limitations, these early studies identified important factors that influence certain virus isolation rates, including patient readmission status and season of illness,18 sensitivity of detection method,14 environmental exposures such as parental smoking,21 and patient age.22 The controversial question of whether viral infections cause asthma exacerbations or if the asthma phenotype enhances susceptibility to infectious disease was still not answered.

One of the earliest longitudinal surveys, the Roehampton study conducted in the United Kingdom by Horn and colleagues,23 spanned 1967 to 1972 and provided key information regarding potential changes in the types of pathogens isolated at different seasons and ages. Despite the lack of high-tech tools such as PCR and microarrays, the extensive study found that HRV, HPIV, and RSV were the predominant infectious agents in 614 isolates. RSV infection was highest among children younger than 4 years and occurred most often during winter months, whereas HRV illnesses occurred at all seasons and ages. Recent reports that use PCR and more sensitive methods generally confirm the findings of the Roehampton study.7, 24, 25 The frequent detection of respiratory tract pathogens during acute lower respiratory bronchitis26, 27 suggests microbial pathogens trigger airway inflammation and stimulate leukocyte infiltration. More importantly, certain populations of children wheeze after a viral infection but show no symptoms of wheeze between viral infections, suggesting an immediate correlation between asthmatic phenotype and respiratory infections.28 Although a multitude of factors, such as genetics, environment, weather, and atopic sensitization, could trigger asthma attacks, microbial pathogens have a potential for contributing to both persistent and episodic asthma attacks.

Causal direction of respiratory infections in asthma: clinical studies in children

Birth cohort and longitudinal studies conducted in the last 2 decades also support the findings from Horn and colleagues.23 In Perth, Australia, Kusel and colleagues29 followed 236 infants from birth to their first year of life to assess the incidence of acute respiratory illnesses (ARIs) of viral or bacterial origin. Collecting NPA samples and using PCR for viral detection, the Perth study identified HRV, RSV, human coronavirus (HCoV), HPIV, and IF as the predominant respiratory pathogens associated with ARIs. In control children, who were healthy and asymptomatic, 24% of the NPA samples were positive for viral agent whereas viruses were present in 69% of the infected children. HRV was the most frequent virus identified with all 3 forms of ARI, including upper respiratory illness (URI), lower respiratory illness without wheeze (nwLRI), and lower respiratory illness with wheeze (wLRI). The attributable risk associated with wLRI, which is a measure of the degree to which a specific pathogen contributes to the severity of the respiratory illness, was highest for HRV and RSV, at 39% and 12%, respectively.29 In a 5-year follow-up of the original Perth birth cohort, HRV- and RSV-associated wheeze with LRI were correlated with statistical significance to current or persistent wheeze, and current asthma later in life.7 Skin prick tests helped categorize the remaining 198 children into the following groups: never atopic, atopic by age of 2 years, or atopic after 2 years. Combining ARI histories and status of atopic sensitization, children who were atopic by age 2 and had acquired wLRI HRV infections were found to have the greatest likelihood of developing wheeze by age 5 years. Odds ratios associated with this group nearly doubled when more than one wLRI was reported. The cohort studies by Merci and colleagues7 provide evidence that HRV-induced wLRI and early sensitization are risk factors for current and persistent wheeze and asthma by the age of 5 years.

A report in 2008 by Jackson and colleagues30 further supports a correlation between wheezy rhinovirus infections and the development of asthma in children younger than 6 years. Among 259 children examined in the study known as Childhood Origins of ASThma (COAST) in Madison, Wisconsin, 73 children developed childhood asthma by their sixth year. Wheezing illnesses attributed to either HRV or RSV in their third year of life increased their risk of developing asthma by age 6; in particular, 90% of children who had wheezy HRV-induced illness by age 3 subsequently became asthmatic by age 6 years. HRV-induced wheezing observed within the first, second, and third years of life increased the risk for asthma by the age of 6, and led to the conclusion that rhinovirus-associated illnesses during infancy are early predictors of subsequent development of asthma by age 6 years. In agreement with Merci and colleagues7 and Stein and colleagues,31 respiratory illnesses without wheeze were not statistically correlated with the development of asthma at age 6 years. Several longitudinal studies implicated HRV as a prominent viral pathogen in asthma etiology.

The causal direction of RSV-induced illness with asthma appears to be more difficult to define because the severity of RSV-induced disease appears to be affected by age, environment, and atopy. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the study designs, population groups, and types of respiratory tract pathogens isolated in international clinical studies of adults and children from the 1970s to the current time. Four Swedish cohort studies conducted by Sigurs and colleagues27, 32, 33, 34 prospectively followed 46 children from infancy until the age of 18 years. Compared with 92 age-matched control subjects, exposure to RSV was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of asthma (39% in RSV-exposed vs 9% in controls), allergic rhinoconjunctivitis at age 1327 (39% in RSV-exposed vs 15% in controls), and sensitization to allergens by age 1834 (41% in RSV-exposed vs 14% in controls). The occurrence of RSV-induced bronchiolitis within the first year of life was associated with the development of asthma at ages 7 and 13 years. A 2-year prospective study conducted in Finland using PCR detection methods identified RSV, HRV, and other viruses as the major etiologic agents in acute expiratory wheeze in 293 hospitalized children, from 3 months to16 years of age.35 Among the cases of acute expiratory wheezing, 88% involved a single respiratory virus while coinfection with several different viruses comprised 19% of all cases. The study found noticeable age-dependent variations in viral agent prevalence: RSV infects children younger than 11 months more than other age groups, whereas enteroviruses and HRV are most prevalent in children aged 12 months or older.35 Unfortunately, no screening for atypical bacteria was performed to assess the prevalence of C pneumoniae or M pneumoniae.

Table 1.

Clinical studies investigating respiratory tract infections in adults

| Location | Study Period | Population Studied | Method for Detection | Pathogens Identified | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wellington, New Zealand22 | Prospective cohort; Jan 1984–Dec 1984 | 31 atopic asthmatic adults (15–56 y) | NPA for IF, cell culture, serology, electron microscopy | RSV, HRV, IF, HPIV, AdV, Herpes simplex, Enterovirus | 60% of severe asthma exacerbations associated with viruses |

| Nottingham, UK6 | Case-control; Sep 1993–Dec 1993 | 76 asthmatic adults (26–47 y) and cohabitating partners without asthma | NPA for PCR | HRV | Asthmatics with significantly longer and more frequent LRI |

| San Francisco, US13, 43 | Prospective cohort; Fall 2001–Dec 2004 | 53 adults with asthma, 30 without asthma | PCR, viral culture, and Virochip microarray | HRV, HCoV, RSV, HMPV, HPIV, IF | 98% concordance with PCR and microarray; HRV most common with >20 serotypes |

Table 2.

Clinical studies investigating respiratory tract infections in children

| Location | Study Period | Population Studied | Detection Method | Pathogens Identified | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh, UK18 | Prospective cohort; Nov 1971–Oct 1974 | 360 children with acute wheezy bronchitis; >1 y old, first and readmissions | NPA for viral culture | HRV, HCoV, RSV, HPIV, IF, echovirus, Coxsackievirus, mumps | RV (16/38) and RSV (6/38) positive from 267 virus isolations |

| Wiltshire, UK17, 19, 23 | Prospective cohort; Oct 1974–Apr 1976 | 72 episodes of wheezy bronchitis among 22 children (5–15 y) | Throat/sputum swabs for viral culture | HRV, IF, HPIV, RSV, AdV, M pneumoniae, coinfections | 49% of episodes were virus-positive, predominantly RV |

| Turku, Finland21 | Prospective cohort; Sep 1985–Aug 1986; Jan 1987 | 54 asthmatic children (1–6 y) with recurrent wheezy bronchitis | NPA for viral culture, serology | HCoV, HRV, AdV, IF, HPIV, M pneumoniae, coinfections | 45% episodes positive for virus or M pneumoniae; predominantly HCoV outbreak of coronavirus |

| Southampton, UK26 | Prospective cohort; Apr 1989–May 1990 | 108 children (9–11 y) reporting wheeze or cough | NPA for IF, viral culture, serology, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, probes | HRV, HCoV, IF, HPIV, RSV, others | 77% detected viral positive in 292 reported episodes & RV representing 2/3; 81% LRI |

| Nord-Pas de Calais, France37 | Prospective cohort; Oct 1998–June 1999 | 113 children (2–16 y) with acute or active asthma | Nasal swabs for IF and RT-PCR, serology | HRV, RSV, AdV, HPIV, HCoV, enterovirus, C pneumoniae. M pneumoniae | RV (12%) and RSV (7.3%) of total of 38% virus-positive; 10% atypical bacteria-positive |

| Finland35 | Prospective clinical trial | 293 hospitalized children (3 mo to 16 y) for acute wheezing | PCR detection | HRV, RSV, enterovirus | HRV or RSV attributed to 88% cases; 19% cases from coinfections |

| Sweden27, 32, 33, 34 | Prospective cohort; Dec 1989–2009 | 46 children (<1–18 y); 92 age-matched healthy controls | PCR and culture | RSV | RSV-exposed subjects had 39% of asthma compared with unexposed (9%) |

| Atlanta, USA8 | Case-control; Mar 2003–Feb 2004 | 142 enrolled children (2 groups: <6 or 6–17 y); 65 acute asthma cases and 77 well-controlled asthma controls | Nasal and throat swabs for PCR and RT-PCR | HRV, RSV, HMPV, HCoV, bocavirus, AdV, IF, HPIV, enterovirus | 63.1% positive ≥1 viruses in case vs 23.4% in controls; predominantly RV |

| Perth, Australia7, 29 | Prospective cohort; Jul 1996–Jul 1999 | 236 atopic children enrolled, 198 children (<1–5 y) | NPA for PCR | HRV, HPIV, HMPV, RSV, HCoV, AdV, M pneumoniae, C pneumoniae, coinfections | 69% ARI are virus-associated; predominantly RV (48.3%) and RSV (10.9%) |

| Madison, USA30 | Prospective cohort; Sep 1998–current | 259 children enrolled in COAST | NPA for PCR | HRV, RSV | 90% of children with wheezy HRV-induced illness by 3 y subsequently acquired asthma at age 6 y |

In contrast, the 1980–1984 Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study conducted by Stein and colleagues31 and Taussig and colleagues36 found RSV-associated LRI wheezing episodes by age 2 as an independent risk factor for wheezing and asthma at age 11 but not at age 13 years. Differences between the Swedish and Tucson study designs may account for the discrepancy in results at age 13 years. The Tucson questionnaire study enrolled healthy children in the first year of life, whereas the Swedish study investigated primarily infants younger than 6 months, who were hospitalized for RSV-induced bronchiolitis. Consequently, the Swedish study examined incidences of severe RSV-induced respiratory illnesses that resulted in enhanced airway obstruction and limited airway function. Furthermore, the Tucson study used immunofluorescence and viral culturing without PCR, and this may have resulted in missed detection of viral pathogens. For example, children who acquired virus-negative LRI before the age of 3 years were found to have an increased risk of frequent wheeze at age 8 compared with healthy controls31; moreover, LRIs caused by other agents, including rhinovirus, contributed a low proportion (14.4%) of the 472 reported LRIs and were not statistically correlated with frequent wheeze after age 3 years. These findings conflict with studies that identified HRV as the predominant cause of wheezy LRI in children in the age range of 6 to 17 years8, 26, 30, 37 or reports that found relatively low PCR detection of the atypical respiratory bacteria, C pneumoniae and M pneumoniae, in children.15, 38 Despite the design differences, the Sweden, Finland, and Tucson clinical studies all implicate RSV as an important pathogen in the subsequent development of early childhood asthma.

Etiologic agents of respiratory tract infections

HRVs cause common colds and ARIs in both adults and children. HRVs are related to enteroviruses, such as poliovirus, echovirus, and Coxsackievirus. The positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome of HRV is encased within a highly variable protein capsid composed of an icosahedral arrangement of 60 copies of viral proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4. Canyon-like depressions circle the vertices made of 5 triangular repeats of VP1,39 and binding of the virus to cell receptors occurs near the canyons.40 HRV-A and HRV-B diversity exceeds 100 serotypes, most of which were identified before the 1970s and continue to circulate, suggesting that emerging strains may not be new but rather previously unrecognized.41 Highly sensitive genome sequencing and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR has generally replaced serotyping in diagnostics,42, 43, 44 and researchers using this method discovered a third viral subgroup in 2006 called HRV-C that is associated with fall and winter asthma flares in children.45, 46

Infecting mostly adults and children older than 3 years,35 HRV enters through the upper respiratory tract via aerosolized droplets or transmission by hand contact.47 HRV illnesses are usually noticeable within the first 3 days, accompanied by symptoms of the common cold, including nasal congestion, cough, sneezing, headaches, and sore throat.48 Replication in epithelial cells occurs optimally at temperatures from 33° to 35°C, which lead investigators to consider HRV exclusively as an etiologic agent of upper RIs. Recent evidence, however, indicates that HRV is equally as important as a lower respiratory tract pathogen.6, 7 Symptoms of HRV infection often persist in the lower airways of adults49 and the elderly,50 yet evidence supporting the hypothesis that HRV causes chronic infections is limited because early longitudinal studies failed to identify HRV serotypes. Therefore, it is still unclear whether persistent HRV-induced ARIs result from chronic or new infections with different serotypes.51 In support of the argument that HRVs do not cause chronic infections, a follow-up evaluation of the COAST study participants found consecutive, recurrent HRV infections with the same serotype to be uncommon.52 Because a large number of serotypes recirculate in populations, reinfection with the same serotype is unlikely. Similar to other highly diverse viral pathogens, antigenic diversity could serve as a means for evading adaptive immunity.51

Despite differences in nucleotide sequence, antiviral drug susceptibility,53, 54 and capsid protein coding, nearly 90% of the HRV serotypes share a common cellular receptor for viral attachment to human epithelial cells.55, 56 Virus-cell surface attachment and subsequent infection is mediated through binding to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). ICAM-1 usually functions in leukocyte migration and antigen-independent adhesion for lymphocyte interaction.57 ICAM-1 is the predominant receptor used by circulating HRV serotypes, and receptor compatibility appears to limit HRV host range.58 ICAM-1 receptor is becoming recognized more and more as the attachment molecule of other pathogens, including rhinovirus,39 some Coxsackie virus species,59 and more recently, RSV.60 Some evidence suggests that ICAM-1 expression is modulated by HRV after infection, making ICAM-1 a promising target for antiviral therapies.61, 62

RSV is a member of the Paramyxoviridae family and is related to the etiologic agents of mumps, measles, and parainfluenza. As one of the leading causes of pediatric and geriatric respiratory diseases, RSV infections recur throughout life, and long-term immunity through vaccination has thus far been unsuccessful.63, 64 RSV infections result in approximately 10,000 deaths annually in persons older than 65 years and account for an estimated 30% of respiratory-related health care visits.65 RSV mortality and morbidity increase among infants, the immunocompromised, and pulmonary hypertensive populations.66, 67 Seniors in particular remain at high risk for RSV infections because they may be exposed to nosocomial infections in the hospital or long-term care facilities.68, 69 The most notorious RSV vaccine failure used formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) to stimulate immunity, much like the Salk polio vaccine. Unfortunately, FI-RSV failed to elicit neutralizing antibody maturation70 and in its place, CD4+ T-cell–mediated immunopathology was enhanced.71, 72

At present, 2 prophylactic neutralizing antibodies against the RSV glycoprotein G have been reviewed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are available to high-risk infants,64 but no effective vaccine or therapy is available for general populations. RSV disease onset resembles HRV infection with fever and wheezing. Several RSV proteins have been credited with suppression of the antiviral response, including nonstructural proteins 1 and 2 (NS1 and NS2), which disrupt JAK-STAT signaling and interferon (IFN)-β expression.73, 74 As a result, human RSV is a poor inducer of the antiviral type-1 IFN response. Primary and subsequent RSV infections lead to epithelial damage, lymphocyte infiltration, and airway inflammation.75, 76

The single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome of RSV is associated with a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex consisting of the nucleocapsid (N), phosphoprotein (P), and large (L) RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. On virion assembly and filamentous budding from infected epithelial cells, a bilipid envelope layer is derived from the host cell and interacts with the matrix (M) protein to surround the RNP.77 A visual hallmark of RSV infections in monolayer culture cells is the formation of syncytia, which resemble multinucleated cells. Fusion of neighboring cells is initiated by RSV glycoproteins F and G and the small hydrophobic protein (SH), as plasmid transfection of these 3 viral proteins was found sufficient for syncytium formation.78 F and G have numerous roles in disrupting host-cell responses to infection and interfering with antiviral signaling.79 Investigations of individual RSV proteins provide evidence that RSV has the capacity to alter the host immune response and stimulate chronic inflammatory responses.

Viruses are not the only respiratory pathogens that can cause chronic infection and contribute to asthma. Although less prominent than the reports about HRV or RSV, longitudinal studies examining asthma exacerbations consistently recover and detect by PCR15 the atypical bacteria, Chlamydophila pneumoniae 80, 81 and Mycobacterium pneumoniae.82 C pneumoniae, an etiologic agent of atypical pneumonia, is detectable by serology, culture, antigen detection, and complement fixation, and is found in 2% to 11% of cases of acute exacerbation in children.7, 15, 37, 83 Infections with C pneumoniae have been reported as high as 86% in adults when PCR detection was used.9 Similarly, M pneumoniae contributes to 5.7% to 28.4% of pneumonia infections and is the predominant cause of tracheobronchitis.84 As likely agents of chronic respiratory infection, C pneumoniae and M pneumoniae have been found to possess numerous mechanisms for disrupting innate, humoral, and cell-mediated immune responses.

Mechanisms of virus-induced immunopathology and asthma exacerbations

Cellular Responses

Most HRV serotypes and RSV strains cause little cellular injury to bronchial epithelial cells in culture compared with infections with influenza A virus.85, 86 Some epithelial cell necrosis occurs and cellular debris accumulates in severe RSV infections,87 but the majority of HRV- and RSV-induced pathology is attributed to indirect stimulation of host innate and adaptive immune cells. In vitro culture assays and animal model systems have been vital resources for studying disease pathogenesis. Unfortunately, primate cells are selectively permissive to a large number of HRV serotypes. Cells from rodents and other mammals lack the primate ICAM-1 receptor for HRV absorption and thus do not support the replication of the 90% of serotypes defined as the major group.58 This problem has hindered studies of major-group HRV in vivo using animal models. Rodent cells are semipermissive to the remaining 10% (minor-group). Consequently, a minor-type rhinovirus-1B strain was used to develop rhinovirus 1B-induced asthma exacerbations in BALB/c mice.88 Because RSV infections are relatively inefficient in adult rodents, high viral loads of RSV (105–107 pfu) are required to produce pathologic changes through intranasal89, 90, 91 or intratracheal87 inoculation. Despite some limitations, the murine models of virus-induced asthma exacerbation have provided a great deal of information regarding HRV and RSV pathogenesis.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid recovered from minor-group RV1B HRV-infected mice often demonstrates neutrophilia, up-regulation of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted), and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), and have increased production of T-cell chemokines within the first 2 days after infection.86, 88, 92, 93 Other chemokines elevated in murine RSV infection include monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1), MIP-1α, interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10), IFN-γ, IL-5, and keratinocyte cytokine (KC).87, 94, 95 The early flux of chemokines after HRV or RSV infection in mice is thought to contribute to lymphocyte activation and recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and eosinophils.

Translating the mouse studies to human subjects, Gern and colleagues and other groups96, 97, 98, 99 have recruited human patients, inoculated them with major-group rhinovirus-16 (RV16), and observed cellular responses to HRV infections. Surprisingly, cellular profiles after RV16 inoculation do not differ greatly among atopic asthmatics or nonatopic subjects.100 Neutrophils were found to be the predominant cells recovered in BAL fluid,97 but the neutrophilia was present in both groups during acute cold illnesses. No significant group-specific differences were observed in peak nasal viral titers or cold symptom scores. Bronchial biopsies from HRV-infected asthma patients display T-cell infiltration at the site of infection,101 yet similar infiltration was absent in HRV-infected subjects without asthma.99 Gern and colleagues97, 100, 102 also observed elevated secretion of the neutrophil chemotaxin, IL-8, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), IP-10, and MIP-2 in the sputum samples of infected asthma patients. Neutrophil recruitment was correlated with virus-mediated influx of IL-8103 in both asthmatic and nonatopic individuals. Overall, the lack of cellular differences suggests that RV16 replication is not enhanced in atopic or asthmatic individuals.

The levels of eosinophil in sputum were significantly higher in asthmatics at baseline (7 or 14 days before inoculation) and in nasal lavage fluid during acute RV16 infection and following convalescence.100 Although eosinophils are frequently elevated in nonatopic asthma patients as compared with healthy control groups without asthma,104 eosinophils have been observed to persist in the lower airway of asthma subjects during the convalescence stage of RV16 infection101; a similar eosinophil persistence was not apparent in healthy individuals. Asthmatics had significantly increased secretion of MCP-1 in nasal lavage fluid at baseline (47%) compared with healthy controls (12%). Cumulatively, in vitro and in vivo studies identified some specific characteristics of virus-induced asthma exacerbation, including airway T-cell infiltration, virus-induced recruitment of neutrophils, and enhanced eosinophilia in the airway after recovery from rhinovirus infections.

Unlike HRV (particularly RV16), experimental infections with RSV have not been conducted extensively in human subjects. As of June 2010, only 2 reports used good manufacturing practice–quality wild-type RSV A2 in human experimental infections.105, 106 Healthy young adults aged 18 to 45 years were inoculated through nostril instillation with either a high (4.7 log10 tissue culture infective dose [TCID50]) or a low (3.7 log10 TCID50) RSV dose, and observed for 28 days. While neither control nor inoculated subjects demonstrated severe illness symptoms or lower respiratory disease with cough, shortness of breath, or wheezing, the 8 subjects given high doses and the 5 subjects given low doses shed virus for 1 to 8 days after inoculation.105 Inoculated individuals exhibited mild systemic illness, with fever, chills, and fatigue, but respiratory symptoms remained localized to the upper respiratory tract. The study specifically measured viral titers and levels of viral proteins F and G, but did not report infiltrating cell profiles; thus, cellularity associated with experimental RSV A2 inoculation in humans was not directly comparable with that in murine or in vitro studies. Nasal and bronchial lavages from earlier clinical studies provide evidence that the infiltrating cell and chemokine profiles of RSV-infected patients are similar to those in HRV-infected murine models and human subjects.93 Neutrophils are abundant in the nasal lavages of RSV-infected adults and infants107 and in response to RSV infection, early cytokines and chemokines, like IL-12, IL-18, MIP-1α, IL-8, and RANTES, are up-regulated in the upper respiratory tract.87, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112 Lastly, detectable levels of eosinophils and factors associated with eosinophilic airway inflammation, such as eosinophil cationic protein and eotaxin, were observed to be highest among infants with RSV bronchiolitis when compared with control and non-RSV bronchiolitis.113

The significance of eosinophils in virus-induced asthma is widely debated, because eosinophils are often prevalent in areas of epithelial damage104, 114, 115 and likely contribute to eosinophilic inflammation.116, 117 Conversely, observations from murine models demonstrate a protective role for eosinophils118 in viral clearance through secretion of ribonucleases and other antiviral factors.119 Eosinophil degranulation and release of eosinophil peroxidase (EPO) have been shown in vitro to be enhanced by the presence of viruses in coculture experiments with antigen-presenting cells (APCs; macrophage or dendritic cells) and CD4+ T cells.120 Davoine and colleagues120 demonstrated that the addition of HRV, RSV, or HPIV resulted in elevated EPO and/or leukotriene release. In addition, HRV and RSV stimulated production of IFN-γ in the presence of dendritic cells and T cells when eosinophils were absent. Other reports suggest that eosinophilia and secretion of eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) or RANTES are potential predictors of asthma and disease severity121, 122, 123; consequently, virus-induced eosinophilia may play a significant role in asthma exacerbations.

Molecular Mechanisms

RSV has been observed to exacerbate pulmonary stress in immunocompromised individuals by increasing airway resistance and potentiating hypoxemia.124 RSV infections alter cytokine production and can result in chronic inflammation, respiratory failure, and death.68, 125 Cellular immunodeficiencies vary with age, and in persons older than 65 years, an alarming 78% of respiratory and pulmonary deaths are RSV-associated.65, 126 RSV employs multiple defenses against the innate and adaptive antiviral response,110, 127, 128, 129 and has the capacity to alter allergic responses and interfere with lymphocyte activation. RSV-infected infants have suppressed IFN-γ production and elevated IL-4, which are sufficient to stimulate IgE and T-helper 2 (Th2)-humoral responses.130 Disruption of Type-I IFN responses through NS1, NS2, G and F, and other RSV proteins promotes viral replication and survival.79

Preliminary studies showed that IRF1 translocates to the nucleus and that the relative expression of IRF1, IRF3, and IRF7 was enhanced through silencing of NS1 with small-interfering RNA against NS1 in RSV-infected A549 lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cells.75 IRF1 is important in apoptosis and activates T-helper 1 (Th1) responses while suppressing inappropriate Th2 responses.131 IFN-regulatory factors have been shown to regulate T-cell differentiation,132 and type-1 IFNs influence dendritic cell maturation133 and Th1/Th2 cytokine production. Impairment of type-1 IFN or IRF1 expression and subsequent Th1 differentiation could result in a Th2-like inflammatory disease.134, 135 Alternatively, the RSV G protein may disrupt the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance. The secreted form of G (sG) contains a domain that mimics the chemokine CX3C136 and induces production of IL-5 and IL-13, leading to eosinophilia through a mechanism that does not require IL-4.137 Further examination is needed to determine the role of the G protein in inflammatory disease and Th2 responses. Collectively, the antagonistic RSV proteins give RSV the capacity to directly or indirectly impair immune cell activation and skew Th1/Th2 profiles.138

Rhinovirus infections trigger a cascade of events that lead to overproduction of mucus,139 activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, and up-regulation of chemokines and cytokines.86 In particular, a potent proinflammatory cytokine, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), is produced by macrophages on NF-κB activation in RV16-infected macrophages derived from either THP-1 or primary monocytes.140 NF-κB activation has been correlated with another respiratory virus, Sendai parainfluenza virus 1, which was used to model virus-induced asthma exacerbations in brown Norway rats.141 Infection with Sendai virus substantially increased expression of the p50 subunit of NF-κB, implying functional activation of NF-κB.142 On virus infection, respiratory epithelial cells show increased expression of several pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors TLR3143 and TLR4,144 in response to HRV and RSV, respectively. RSV-mediated TLR4 overexpression was associated with sensitization of epithelial cells, resulting in enhanced IL-6 and IL-8 production after stimulation with bacterial lipopolysaccharide.145 Lastly, both HRV and RSV use ICAM-1 as a receptor for viral attachment, and up-regulation of ICAM-1 could enhance viral infection. HRV has been observed to selectively enhance membrane-bound ICAM-1 while suppressing expression of secreted ICAM-1.62 In recognition of this binding requirement for effective viral infection by either HRV or RSV, therapeutic applications have attempted to target ICAM-1 with blocking monoclonal antibodies.146 Application of the ICAM-1 blocking antibody CFY196 showed promise in HRV infections, and reduced RV infection symptoms and length of disease in human subjects.147, 148, 149 Similarly, blockage of ICAM-1 through a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to ICAM-1 attenuated RSV infection of epithelial cells in vitro.60

Similar to RSV infections, HRV infections often result in a reduction in the IFN-γ/IL-5 mRNA ratio, as seen in the experimental RV16 infection of human subjects.98 Relatively weak Th1-like responses were also attributed to more severe respiratory disease and longer viral shedding. In human trials, asthmatic individuals did not have increased risk of HRV infection. Instead, the symptoms of clinical illness extended for longer times and were reported as more severe than in healthy, nonasthmatic cohabiting partners who had acquired HRV infections.6 Whereas healthy controls usually had mild URI for 3 days, asthma patients developed both upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms for up to 5 days. A distortion of Th1/Th2 responses is expected to predispose subjects to more severe allergic reactions.93, 138, 150 HRV infections in vitro stimulate IL-4 up-regulation in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of atopic asthmatics,151 which contrasts with the usually observed decrease in IL-4 in PBMCs of healthy controls. Likewise, after RSV infection, ovalbumin-allergic mice have airway hyperresponsiveness and enhanced Th2 responses, accompanied by an up-regulation of IL-4 and increased eosinophilia in the lungs, on inhalation of ovalbumin.152

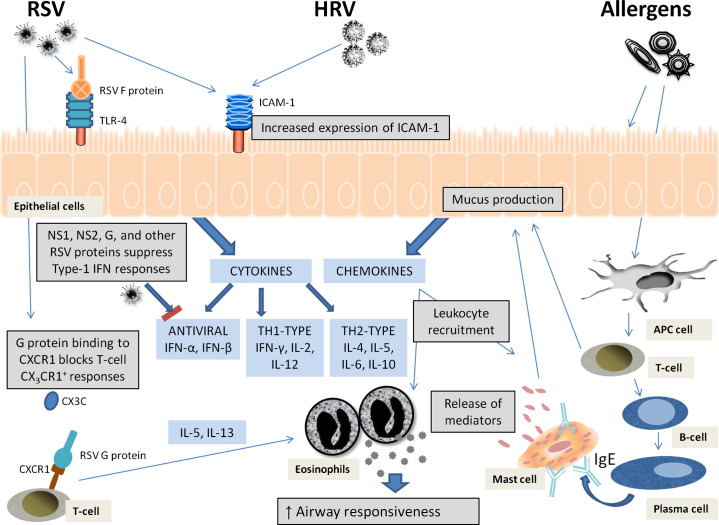

HRV has also been demonstrated to attenuate the type-1 IFN response through disruption of IRF3 activation.153 Although the mechanism may be different, RV14 infection in A549 decreased the nuclear translocation of IRF3 as compared with cells infected with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which is known to induce IFN-β responses. Moreover, immunoblots displayed a loss in the homodimer form of IRF3 in RV14-infected cells compared with VSV-infected cells at both 4 hours and 7 hours after infection. Of note, the expression of PRR-like melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) or mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) protein were unchanged in lysates after infection with RV14 at 4 or 7 hours after infection. Together, this evidence suggests that RV14 disrupts nuclear translocation of IRF3 and suppresses IFN-β production after infection without disrupting either MDA5 or MAVS. Fig. 1 illustrates the mechanisms by which RSV and HRV infections may skew the Th1/Th2 profiles and enhance Th2 responses in allergic or asthmatic individuals.

Fig. 1.

Viral mechanisms that may contribute to asthma exacerbations.

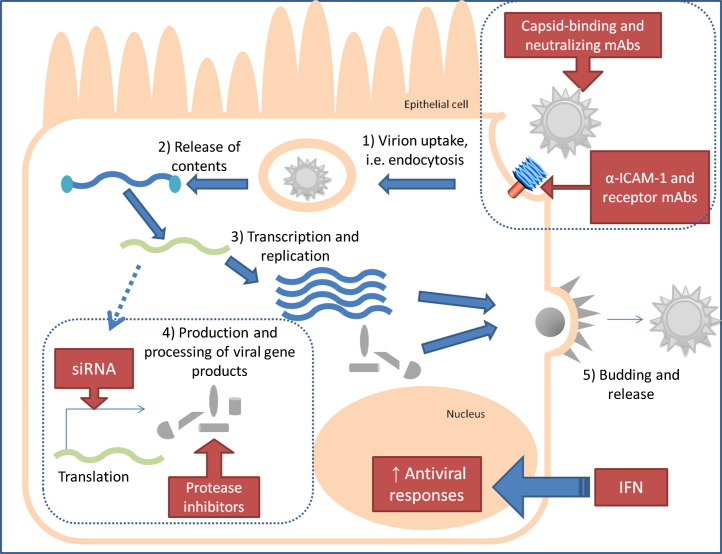

Therapeutic approaches to respiratory viral infections

Developing efficacious and cost-effective antivirals against HRV and RSV has proven to be a continuing challenge for researchers and clinicians (Table 3 ). HRV capsid surface proteins are highly variable among the 100+ serotypes, and passive immunization will likely provide marginal, if any, protection. Because most HRV-induced illnesses in healthy individuals do not lead to hospitalizations, with cold-like symptoms peaking within 2 to 3 days and usually subsiding within a week, therapeutic benefits of any HRV intervention would need to significantly outweigh the risks associated from delivering treatment or immunizing with a vaccine. As with the failed clinical trials of FI-RSV, the associated dangers from vaccine delivery are unpredictable and could result in symptoms that are more serious. Conversely, if respiratory viral agents contribute to the development of asthma, prophylactic use of antivirals has the potential to prevent ARI as well as the chronic illness. Current antiviral drugs target the steps involved in viral propagation to suppress the spread of infection,64, 154 including attachment, replication, protein synthesis, and release of viral progeny, as illustrated in Fig. 2 . Alternatively, supplementation with IFNs promotes antiviral and immunologic effects, thereby decreasing cell susceptibility; intranasal IFN has demonstrated effective prophylactic potential in enterovirus and HRV studies.154 In an RSV-infected murine model, intranasal administration of the plasmid encoding IFN-γ decreased the neutrophilia and pulmonary inflammation that is associated with RSV-induced disease.155

Table 3.

Experimental antiviral pharmacologic agents for HRV and RSV infections

| Compound Class | Virus Infection | Examples | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies to host receptors | RSV and HRV | Monoclonal antibodies to ICAM-1 | HRV infections reduced by >90%148; reduced RSV infections in human epithelial cells60 |

| Small-molecule fusion inhibitors | RSV | BMS-433771, RFI-641 | Prophylactic oral administration reduced lungs viral titers in RSV-infected mice; however, postinfection delivery failed to decrease virus infection.180 Phase 1/2 clinical trials discontinued181 |

| Attachment inhibitor; specific for G glycoprotein | RSV | MBX-300 (NMSO3) | Effective in vitro and in vivo, with EC50 53 value times lower than that of ribavirin.162 Clinical trials expected |

| Peptide-based antisense agents | HRV and enteroviruses | PPMO (peptide-conjugated phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers) | ∼80% higher survival rates in rodent HRV-infected models as compared with untreated controls163 |

| Small-molecule inhibitor of L-protein | RSV | YM-53403 | RSV-specific inhibition of viral RNA replication164 |

| siRNA | RSV | NS1 | Delivery of nanoparticles with siRNA against NS1 significantly attenuated RSV infection in rodent models75, 182 |

Fig. 2.

Targets for antivirals against RSV and HRV.

Several promising antiviral agents physically disrupt the interaction between the virion and host-cell receptor.156, 157, 158 In theory, this will prevent attachment of the virus or reduce its ability to fuse with and infect the cell. The humanized monoclonal antibody against the RSV F protein, palivizumab, is currently the only pharmacologic agent that is FDA-approved for administration to high-risk infants for preventing severe LRI.159, 160 Table 4 summarizes other viral targets and antiviral compounds, such as protease or viral protein inhibitors, which have undergone or are undergoing clinical studies for potential therapeutic applications in humans. Recent clinical trials have eliminated several promising but inadequate and ineffective antiviral candidates. For example, the protease inhibitor rupintrivir demonstrated prophylactic efficacy and reduced viral load in experimental HRV infection158 but failed to protect against natural HRV infection.161 As a result, no future clinical applications are being pursued.

Table 4.

Clinical trials of HRV and RSV antiviral pharmacologic agents

| Compound Class | Virus Infection | Examples | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies to glycoproteins | RSV | Monoclonal antibody to F protein (Palivizumab) | Multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial in 1997; reduced length of RSV hospitalization, disease severity, and admission to intensive care unit160 |

| Antibodies to host receptors | HRV and potentially RSV | Soluble ICAM-1 (Tremacamra) | Four randomized clinical trials in 1996; marginal effectiveness within 12 h of experimental infection with HRV39156 |

| Antibodies to glycoproteins | RSV | Monoclonal antibody to F protein (Motavizumab) | Currently undergoing phase 2 and phase 2 clinical studies; pending FDA review as of Aug 2010157 |

| Capsid-function inhibitor | HRV and enteroviruses | Binds to capsid and disrupts uncoating (Pleconaril) | Phase 2 clinical trial in 2006; results unreleased Two phase 2 clinical trials in 2003 showed reduced cold symptoms and shorter duration of cold158 |

| Protease inhibitors | HRV and enteroviruses | Irreversible inhibitor of HRV 3C protease (Rupintrivir) | Phase 2 clinical studies in 2003; reduced viral load after experimental infection with HRV39177 but not with natural infections161 |

| Protease inhibitors | HRV and enteroviruses | Irreversible inhibitor of HRV 3C protease (Compound I) | Phase 1 clinical studies completed in 2003; reduced viral loads161, 178 but no future trials pending |

| N-protein inhibitor | RSV | RSV-604 | Phase 1 in 2006, phase 2 ongoing179 |

| Antisense to N protein | RSV | ALN-RSV01 | Phase 1 in 2007, phase 2 trial in 2009. First siRNA delivery to respiratory tract106, 165 |

Despite the disappointments with FI-RSV vaccine and rupintrivir, alternative antiviral strategies are being investigated, including the use of large chemical-library screening for identifying specific, small-molecule inhibitors and the delivery of small-interfering RNA to silence viral protein gene expression. As complementary pharmacologic agents or alternatives to passive immunization, small-molecule inhibitors and viral protein antagonists are showing promise in tissue-culture and animal models.75, 162, 163, 164 A few of these alternative, experimental studies are proceeding to clinical application and may be successful. DeVincenzo and colleagues,106 in 2010, were the first group to demonstrate a proof-of-concept application of RNAi (RNA interference) for protection against RSV by delivering siRNA to the respiratory tract in human subjects given experimental RSV infection. RNAi-based therapies have shown promise in vitro and in animal models for various human diseases, predominantly cancer. In rodent models, intranasal delivery of siRNA against the nucleocapsid (N) protein (ALN-RSV01) before or 1 to 2 days after RSV inoculation reduced lung viral titer loads by at least 2 logs.165 Gene silencing of the well-conserved RSV N protein disrupts viral replication through impairment of the RSV RNA polymerase. ALN-RSV01 is the first siRNA delivered to humans via the intranasal route for specifically combating a microbial pathogen.165 In a randomized, phase 2 study conducted by DeVincenzo and colleagues,106 ALN-RSV01 decreased RSV infection in experimentally RSV-inoculated subjects by 38% compared with placebo-treated controls, as diagnosed by 2 culture-based assays. From days 4 to 7 after infection, the mean viral load in pfu/mL decreased approximately 1 log as detected by quantitative RT-PCR. The antiviral effect of ALN-RSV01 was found to be independent of preexisting RSV-neutralizing antibodies or cytokine concentrations. Thus, ALN-RSV01 exhibits potential for therapeutic use in healthy adults. However, low statistical power and insufficient sample numbers hinder the study’s reliability in evaluating the antiviral dose-responsiveness of ALN-RSV01 with respect to viral load and disease symptoms over the entire term of the study. ALN-RSV01 remains an attractive antiviral candidate because few adverse affects were observed in normal adult humans. Further investigations are needed to test the efficacy of RNAi against natural infections, and its applicability to infants and RSV risk groups.

Postinfection therapeutics with anti-inflammatory agents

HRV and RSV are highly infectious and ubiquitous respiratory pathogens, but eradication of either species in the near future is highly unlikely. To cope with virus-induced bronchiolitis, a variety of anti-inflammatory pharmacologic agents, such as bronchodilators and steroids, are recommended for susceptible individuals to reduce airway inflammation. National health organization guidelines often recommend inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as the primary treatment for recurrent asthma, followed by short- or long-acting β2-agonists (SABA and LABA) and cysteinyl-leukotriene (Cys-LT) receptor agonists (LTRA).166, 167 ICS act to reduce asthma symptoms, and help improve forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR).168 Although ICS demonstrate potency against other inflammatory diseases and continue to be the preferred drug for managing asthma symptoms, evidence is lacking to support ICS in preventing virus-induced wheezing in corticosteroid-unresponsive subpopulations.168, 169 In a clinical study of United Kingdom children aged between 10 and 30 months hospitalized for wheezy ARI, oral corticosteroid prednisolone administration over 5 consecutive days failed to reduce disease severity or hospitalization length significantly.169 According to a retrospective United States study, steroid insensitivity was frequent in adolescent populations (∼14 years of age); up to 24% of patients with severe asthma failed to respond to glucocorticosteroid therapy.170 Inconsistent responsiveness to ICS likely results from genetic variability, atopic family history, and airway fibrosis that accumulates after severe epithelial damage.171 At present there is insufficient information to assess the effects of ICS on virus-induced illnesses.

While controversy over the efficacy of ICS on virus-induced ARI continues, recent clinical studies suggest leukotriene receptor antagonists may alleviate virus-induced bronchiolitis. Two clinical trials of the Cys-LT known as montelukast demonstrated efficacy against RSV-induced asthma exacerbations as compared with placebo. Bisgaard and the Study Group on Montelukast and Respiratory Syncytial Virus172 monitored children from 3 to 36 months old for 28 days to compare the effect of chewable tablets of montelukast on RSV-induced bronchiolitis, compared with placebo. In the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, subjects receiving montelukast reported fewer symptoms, and disease severity was significantly less than in the placebo-receiving control population. Post hoc analysis of a similar, but more extensive study by Bisgaard and colleagues173 revealed a comparable therapeutic effect of montelukast on RSV bronchiolitis. Furthermore, Kim and colleagues174 specifically investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of montelukast in infants for a 12-month period by analyzing eosinophil degranulation, as measured by the secretion of an eosinophil biomarker, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN). EDN is more stable than other eosinophil biomarkers and is therefore a better representation of eosinophil inflammatory activity than eosinophil counts alone. For that reason, the group used EDN levels for estimating disease severity and recurrent wheeze. Kim and colleagues observed significantly higher levels of EDN in RSV-infected populations than in uninfected controls; furthermore, patients receiving a 3-month course of montelukast had significantly lower levels of EDN than the placebo-treated group. Based on this evidence, montelukast could be used to treat RSV bronchiolitis; however, further investigation is needed to understand the antiviral mechanism and how different subpopulations respond to the drug.

Challenges and opportunities for asthma therapy

Although infections with other viruses and bacteria may play roles in wheezing, airway inflammation, and hyperactivity, HRV and RSV are the primary etiologic agents associated with acute respiratory illness and asthma exacerbations.8, 26 In 2006, 197 children hospitalized for asthma exacerbations and wheezing episodes were examined in a year-long prospective, cross-sectional study in Buenos Aires.24 The ages ranged from 3 months to 16 years, and PCR was used for detecting virus and bacteria in nasopharyngeal aspirate samples. In agreement with others, Maffey and colleagues24 found virus or bacteria in 78% of the cases (40% RSV, 4.5% HRV, 4.5% M pneumoniae, and 2% C pneumoniae). With increased sensitivity, PCR has enabled detection of pathogens that would otherwise be nondetectable by culture methods. In addition, the methods for recruiting, diagnosing, and examining ARI subjects are becoming standardized, allowing better comparisons with other studies. However, several factors continue to cause variability in community-based studies. Environmental, economic, and social variables will continue to challenge how diagnosticians and health care workers collect data. In some studies, obtaining controls is difficult due to semi-invasive procedures, and comparisons must often be made with asymptomatic individuals.26 Furthermore, the statistical power of these studies is reduced by the relatively small number of eligible and cooperative participants. While most cohort investigations study infants and older children hospitalized for severe ARI symptoms, additional studies on less severe cases should be done to determine how mild RSV infections are associated with wheeze.

Despite the strong evidence for a link between asthma and respiratory infections, the direction of causality between viral infections and asthma is still heatedly debated. Although there is a growing body of evidence supporting a causal relationship for HRV, a similar relationship for RSV is difficult to prove because virtually all children have been infected with RSV by the age of 2 years66, 79; therefore, the development of asthma likely depends on genetic and/or atopic factors.175 Simões and colleagues176 recently reported new evidence that associates RSV infection with the development of recurrent wheeze in nonatopic infants, in a worldwide, multicenter, 24-month investigation. Prophylactic delivery of palivizumab decreased the relative risk of recurrent wheezing in nonatopic infants by 80%. Surprisingly, palivizumab failed to improve wheezing outcomes in infants from families with atopic genetic backgrounds. As one of the first investigations to evaluate the protective effects of palivizumab against recurrent wheeze, the evidence from Simões and colleagues suggests that early-life RSV infection significantly predisposes nonatopic populations to recurrent wheeze. Additional investigations that use prophylaxis, including passive immunization through neutralizing antibodies and other antiviral candidates, are needed to better understand the contribution of viral infections to the development of asthma. Small-interfering RNA, neutralizing antibodies, and RSV fusion inhibitors show promise in vitro and in murine models, but the feasibility of broad-use application remains to be tested.64 As the asthma epidemic persists and wheezing conditions continue to increase the costs of health care, the world awaits the application of more effective prophylactics to prevent microbe-associated respiratory illnesses.

References

- 1.Bloom B., Cohen R.A., Freeman G. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Stat. 2009;10(244):55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinbami L. Office of Information Services; Hyattsville (MD): 2006. NCHS Health E-Stat: asthma prevalence, health care use and mortality: United States, 2003-05. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Health U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda (MD): 2009. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher M.I., Montefort S., Björkstén B. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moorman J.E., Rudd R.A., Johnson R.A. National surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980-2004. MMVR Surveill Summ. 2007;56(SS8 Suppl S):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corne J.M., Marshall C., Smith S. Frequency, severity, and duration of rhinovirus infections in asthmatic and non-asthmatic individuals: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359(9309):831–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merci M.H., Nicholas HdK, Tatiana K. Early-life respiratory viral infections, atopic sensitization, and risk of subsequent development of persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(5):1105–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khetsuriani N., Kazerouni N.N., Erdman D.D. Prevalence of viral respiratory tract infections in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(2):314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosentini R., Tarsia P., Canetta C. Severe asthma exacerbation: role of acute Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Respir Res. 2008;9(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stockton J., Ellis J.S., Saville M. Multiplex PCR for typing and subtyping influenza and respiratory syncytial viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(10):2990–2995. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.2990-2995.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loens K., Goossens H., de Laat C. Detection of rhinoviruses by tissue culture and two independent amplification techniques, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification and reverse transcription-PCR, in children with acute respiratory infections during a winter season. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(1):166–171. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.166-171.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau L.T., Feng X.Y., Lam T.Y. Development of multiplex nucleic acid sequence-based amplification for detection of human respiratory tract viruses. J Virol Methods. 2010;168(1–2):251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kistler A., Avila P.C., Rouskin S. Pan-viral screening of respiratory tract infections in adults with and without asthma reveals unexpected human coronavirus and human rhinovirus diversity. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(6):817–825. doi: 10.1086/520816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambert H.P., Stern H. Infective factors in exacerbations of bronchitis and asthma. Br Med J. 1972;3(5822):323. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5822.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freymuth F., Vabret A., Brouard J. Detection of viral, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in exacerbations of asthma in children. J Clin Virol. 1999;13(3):131–139. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(99)00030-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buscho R.O., Saxtan D., Shultz P.S. Infections with viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae during exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. J Infect Dis. 1978;137(4):377–383. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horn M.E., Reed S.E., Taylor P. Role of viruses and bacteria in acute wheezy bronchitis in childhood—study of sputum. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54(8):587–592. doi: 10.1136/adc.54.8.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell I., Inglis H., Simpson H. Viral-infection in wheezy bronchitis and asthma in children. Arch Dis Child. 1976;51(9):707–711. doi: 10.1136/adc.51.9.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horn M.E., Gregg I. Role of viral infection and host factors in acute episodes of asthma and chronic bronchitis. Chest. 1973;63(Suppl 4):44S–48S. doi: 10.1378/chest.63.4_supplement.44s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders S., Norman A.P. Bacterial flora of upper respiratory tract in children with severe asthma. J Allergy. 1968;41(6):319. doi: 10.1016/0021-8707(68)90074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertsola J., Ziegler T., Ruuskanen O. Recurrent wheezy bronchitis and viral respiratory-infections. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66(1):124–129. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beasley R., Coleman E.D., Hermon Y. Viral respiratory-tract infection and exacerbations of asthma in adult patients. Thorax. 1988;43(9):679–683. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.9.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horn M.E., Brain E., Gregg I. Respiratory viral infection in childhood. A survey in general practice, Roehampton 1967-1972. J Hyg (Lond) 1975;74(2):157–168. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400024220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maffey A.F., Barrero P.R., Venialgo C. Viruses and atypical bacteria associated with asthma exacerbations in hospitalized children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(6):619–625. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf D.G., Greenberg D., Kalkstein D. Comparison of human metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A virus lower respiratory tract infections in hospitalized young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(4):320–324. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000207395.80657.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston S.L., Pattemore P.K., Sanderson G. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9–11 year old children. BMJ. 1995;310(6989):1225–1229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigurs N., Gustafsson P.M., Bjarnason R. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy at age 13. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):137–141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-730OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bush A. Practice imperfect—treatment for wheezing in preschoolers. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):409–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0808951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusel M.M., de Klerk N.H., Holt P.G. Role of respiratory viruses in acute upper and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life—a birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(8):680–686. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000226912.88900.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson D.J., Gangnon R.E., Evans M.D. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(7):667–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein R.T., Sherrill D., Morgan W.J. Respiratory syncytial virus in early life and risk of wheeze and allergy by age 13 years. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):541–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigurs N., Bjarnason R., Sigurbergsson F. Asthma and immunoglobulin e antibodies after respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: a prospective cohort study with matched controls. Pediatrics. 1995;95(4):500–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigurs N., Bjarnason R., Sigurbergsson F. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy is an important risk factor for asthma and allergy at age 7. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1501–1507. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sigurs N., Aljassim F., Kjellman B. Asthma and allergy patterns over 18 years after severe RSV bronchiolitis in the first year of life. Thorax. 2010 doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121582. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jartti T., Lehtinen P., Vuorinen T. Respiratory picornaviruses and respiratory syncytial virus as causative agents of acute expiratory wheezing in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(6):1095–1101. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.030629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taussig L.M., Wright A.L., Morgan W.J. The Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study: I. Design and implementation of a prospective study of acute and chronic respiratory illness in children. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(6):1219–1231. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thumerelle C., Deschildre A., Bouquillon C. Role of viruses and atypical bacteria in exacerbations of asthma in hospitalized children: a prospective study in the Nord-Pas de Calais region (France) Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35(2):75–82. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham A.F., Johnston S.L., Julious S.A. Chronic Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and asthma exacerbations in children. Eur Respir J. 1998;11(2):345–349. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.11020345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bella J., Rossmann M.G. Review: rhinoviruses and their ICAM receptors. J Struct Biol. 1999;128(1):69–74. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colonno R.J., Condra J.H., Mizutani S. Evidence for the direct involvement of the rhinovirus canyon in receptor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(15):5449–5453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monto A.S., Bryan E.R., Ohmit S. Rhinovirus infections in Tecumseh, Michigan—frequency of illness and number of serotypes. J Infect Dis. 1987;156(1):43–49. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ann C.P., Jennifer A.R., Stephen B.L. Analysis of the complete genome sequences of human rhinovirus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1190–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kistler A.L., Webster D.R., Rouskin S. Genome-wide diversity and selective pressure in the human rhinovirus. Virol J. 2007;3(4):40. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tapparel C., Junier T., Gerlach D. New complete genome sequences of human rhinoviruses shed light on their phylogeny and genomic features. BMC Genomics. 2007;10(8):224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee W.M., Kiesner C., Pappas T. A diverse group of previously unrecognized human rhinoviruses are common causes of respiratory illnesses in infants. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(10):e966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wos M., Sanak M., Soja J. The presence of rhinovirus in lower airways of patients with bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(10):1082–1089. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-973OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gwaltney J.M., Jr., Hendley J.O. Rhinovirus transmission: one if by air, two if by hand. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;107(5):357–361. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelly J.T., Busse W.W. Host immune responses to rhinovirus: mechanisms in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(4):671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wos M., Sanak M., Burchell L. Rhinovirus infection in lower airways of asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2 Suppl 1):S314. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Louie J.K., Yagi S., Nelson F.A. Rhinovirus outbreak in a long term care facility for elderly persons associated with unusually high mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(2):262–265. doi: 10.1086/430915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Regamey N., Kaiser L. Rhinovirus infections in infants: is respiratory syncytial virus ready for the challenge? Eur Respir J. 2008;32(2):249–251. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00076508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jartti T., Lee W.M., Pappas T. Serial viral infections in infants with recurrent respiratory illnesses. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(2):314–320. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00161907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ledford R.M., Patel N.R., Demenczuk T.M. VP1 sequencing of all human rhinovirus serotypes: insights into genus phylogeny and susceptibility to antiviral capsid-binding compounds. J Virol. 2004;78(7):3663–3674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3663-3674.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graat J.M., Schouten E.G., Heijnen M.L.A. A prospective, community-based study on virologic assessment among elderly people with and without symptoms of acute respiratory infection. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(12):1218–1223. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abraham G., Colonno R.J. Many rhinovirus serotypes share the same cellular receptor. J Virol. 1984;51(2):340–345. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.2.340-345.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greve J.M., Davis G., Meyer A.M. The major human rhinovirus receptor is ICAM-1. Cell. 1989;56(5):839–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.vandeStolpe A., vanderSaag P.T. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Mol Med. 1996;74(1):13–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00202069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lomax N.B., Yin F.H. Evidence for the role of the p2-protein of human rhinovirus in its host range change. J Virol. 1989;63(5):2396–2399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2396-2399.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiao C., Bator-Kelly C.M., Rieder E. The crystal structure of Coxsackievirus A21 and its interaction with ICAM-1. Structure. 2005;13(7):1019–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Behera A.K., Matsuse H., Kumar M. Blocking intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human epithelial cells decreases respiratory syncytial virus infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280(1):188–195. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grunberg K., Sharon R.F., Hiltermann T.J.N. Experimental rhinovirus 16 infection increases intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in bronchial epithelium of asthmatics regardless of inhaled steroid treatment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30(7):1015–1023. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whiteman S.C., Bianco A., Knight R.A. Human rhinovirus selectively modulates membranous and soluble forms of its intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) receptor to promote epithelial cell infectivity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(14):11954–11961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varga S.M. Fixing a failed vaccine. Nat Med. 2009;15(1):21–22. doi: 10.1038/nm0109-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Empey KM, Peebles RS Jr, Kolls JK. Reviews of anti-infective agents: pharmacologic advances in the treatment and prevention of respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50(9):1258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Falsey A.R., Hennessey P.A., Formica M.A. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1749–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang W., Lockey R.F., Mohapatra S.S. Respiratory syncytial virus: immunopathology and control. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2006;2(1):169–179. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macdonald N.E., Hall C.B., Suffin S.C. Respiratory syncytial viral-infection in infants with congenital heart-disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(7):397–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208123070702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnstone J., Majumdar S.R., Fox J.D. Viral infection in adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: prevalence, pathogens, and presentation. Chest. 2008;134(6):1141–1148. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garcia R., Raad I., Abi-Said D. Nosocomial respiratory syncytial virus infections: prevention and control in bone marrow transplant patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18(6):412–416. doi: 10.1086/647640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delgado M.F., Coviello S., Monsalvo A.C. Lack of antibody affinity maturation due to poor Toll-like receptor stimulation leads to enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. Nat Med. 2009;15(1):34–41. doi: 10.1038/nm.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim H.W., Canchola J.G., Brandt C.D. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Connors M., Giese N.A., Kulkarni A.B. Enhanced pulmonary histopathology induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) challenge of formalin-inactivated RSV-immunized BALB/c mice is abrogated by depletion of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-10. J Virol. 1994;68(8):5321–5325. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5321-5325.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spann K.M., Tran K.C., Collins P.L. Effects of nonstructural proteins ns1 and ns2 of human respiratory syncytial virus on interferon regulatory factor 3, NF-{kappa}B, and pro-inflammatory cytokines. J. Virol. 2005;79(9):5353–5362. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5353-5362.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lo M.S., Brazas R.M., Holtzman M.J. Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural proteins ns1 and ns2 mediate inhibition of stat2 expression and alpha/beta interferon responsiveness. J Virol. 2005;79(14):9315–9319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9315-9319.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang W., Yang H., Kong X. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection with intranasal siRNA nanoparticles targeting the viral NS1 gene. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):56–62. doi: 10.1038/nm1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kong X., Zhang W., Lockey R.F. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in Fischer 344 rats is attenuated by short interfering RNA against the RSV-NS1 gene. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2007;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1479-0556-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takimoto T., Portner A. Molecular mechanism of paramyxovirus budding. Virus Res. 2004;106(2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heminway B.R., Yu Y., Tanaka Y. Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus F-protein, G-protein, and SH-protein in cell-fusion. Virology. 1994;200(2):801–805. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oshansky C.M., Zhang W., Moore E. The host response and molecular pathogenesis associated with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(3):279–297. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hahn D.L., Dodge R.W., Golubjatnikov R. Association of Chlamydia pneumoniae (strain TWAR) infection with wheezing, asthmatic bronchitis, and adult-onset asthma. JAMA. 1991;266(2):225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hahn D., Bukstein D., Luskin A. Evidence for Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in steroid-dependent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;80:45–49. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62938-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kraft M., Cassell G.H., Henson J.E. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the airways of adults with chronic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(3):998–1001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9711092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Allegra L., Blasi F., Centanni S. Acute exacerbations of asthma in adults: role of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:2165–2168. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07122165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Clyde W.A. Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory-disease symposium—summation and significance. Yale J Biol Med. 1983;56(5-6):523–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang L., Peeples M.E., Boucher R.C. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human airway epithelial cells is polarized, specific to ciliated cells, and without obvious cytopathology. J Virol. 2002;76(11):5654–5666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5654-5666.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schroth M.K., Grimm E., Frindt P. Rhinovirus replication causes RANTES production in primary bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20(6):1220–1228. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miller A.L., Terry L.B., Lukacs N.W. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(8):1419–1430. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bartlett N.W., Walton R.P., Edwards M.R. Mouse models of rhinovirus-induced disease and exacerbation of allergic airway inflammation. Nat Med. 2008;14(2):199–204. doi: 10.1038/nm1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peebles R.S., Jr., Graham B.S. Pathogenesis of respiratory syncytial virus infection in the murine model. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(2):110–115. doi: 10.1513/pats.200501-002AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mejias A., Chávez-Bueno S., Gómez A.M. Respiratory syncytial virus persistence: evidence in the mouse model. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(Suppl 10):S60–S62. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181684d52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Graham B., Perkins M., Wright P. Primary respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J Med Virol. 1988;26(2):153–162. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890260207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bonville C., Rosenberg H., Domachowske J. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha and RANTES are present in nasal secretions during ongoing upper respiratory tract infection. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1999;10(1):39–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.1999.101005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jackson D.J., Johnston S.L. The role of viruses in acute exacerbations of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1178–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stack A.M., Malley R., Saladino R.A. Primary respiratory syncytial virus infection: pathology, immune response, and evaluation of vaccine challenge strains in a new mouse model. Vaccine. 2000;18(14):1412–1418. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kong X., Hellermann G., Patton G. An immunocompromised BALB/c mouse model for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Virology Journal. 2005;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.David E.P., William W.B., Kris A.S. Rhinovirus-induced PBMC responses and outcome of experimental infection in allergic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(4):692–698. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.104785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nizar N.J., James E.G., Elizabeth A.B.K. The effect of an experimental rhinovirus 16 infection on bronchial lavage neutrophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(6):1169–1177. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gern J.E., Vrtis R., Grindle K.A. Relationship of upper and lower airway cytokines to outcome of experimental rhinovirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2226–2231. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2003019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]