Abstract

The ribonucleoside building block, N2-isobutyryl-2′-O-propargyl-3′-O-levulinyl guanosine (Scheme 1), was prepared from commercial N2-isobutyryl-5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-O-propargyl guanosine in a yield of 91%. The propargylated guanylyl(3′-5′)guanosine phosphotriester shown in Scheme 2 was synthesized from the reaction of N2-isobutyryl-2′-O-propargyl-3′-O-levulinyl guanosine with N2-isobutyryl-5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-3′-O-[(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N-diisopropylaminophosphinyl] guanosine and isolated in a yield of 88% after P(III) oxidation, 3′-/5′-deprotection and purification. The propargylated guanylyl(3′-5′)guanosine phosphotriester was phosphitylated using 2-cyanoethyl tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite and 1H-tetrazole and was followed by an in situ intramolecular cyclization to give a propargylated c-di-GMP triester (Scheme 3), which was isolated in a yield of 40% after P(III) oxidation and purification. Complete N-deacylation of the guanine bases and removal of the 2-cyanoethyl phosphate protecting groups from the propargylated c-di-GMP triester were performed by treatment with aqueous ammonia at ambient temperature. The final 2′-desilylation reaction was effected by exposure to triethylammonium trihydrofluoride to give the desired propargylated c-di-GMP diester, the purity of which exceeded 95% (Figure 2B). Biotinylation of the propargylated c-di-GMP diester was easily accomplished through its cycloaddition reaction with a biotinylated azide derivative (Scheme 4) under click conditions to produce the biotinylated c-di-GMP conjugate of interest in an isolated yield of 62%.

Introduction

Cyclic (3′-5′)diguanylate (c-di-GMP) was first identified in Acetobacter xylinum as a factor that allosterically regulates membrane cellulose synthesis (1-3). More recently, enzymes controlling the intracellular levels of c-di-GMP, particularly those including the GGDEF (Gly-Gly-Asp-Glu-Phe) and EAL (Glu-Ala-Leu) domains, which possess diguanylate cyclase and phosphodiesterase activities, respectively, have been identified in the majority of bacterial genomes (2). Consistent with these findings, functional studies have determined that c-di-GMP levels regulate important bacterial programs, such as those associated with a switch from planktonic to biofilm growth and those associated with virulence (2). Moreover, c-di-GMP has been identified as a potent adjuvant, owing to its ability to induce the expression of a number of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-1, IFN-β, IP-10 and Rantes) (4, 5). More recent studies have provided evidence for a cytosolic sensor that detects c-di-GMP and initiates this inflammatory response (5). However, the sensor responsible for eliciting this inflammatory response, as well as many components in bacterial c-di-GMP signaling cascades, remain unidentified. The development of a biotinylated c-di-GMP conjugate provides an important tool for the identification and characterization of the proteins binding this ligand and their respective signaling pathways, both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Moreover, these tools may also prove valuable in characterizing the responses associated with c-di-AMP (6).

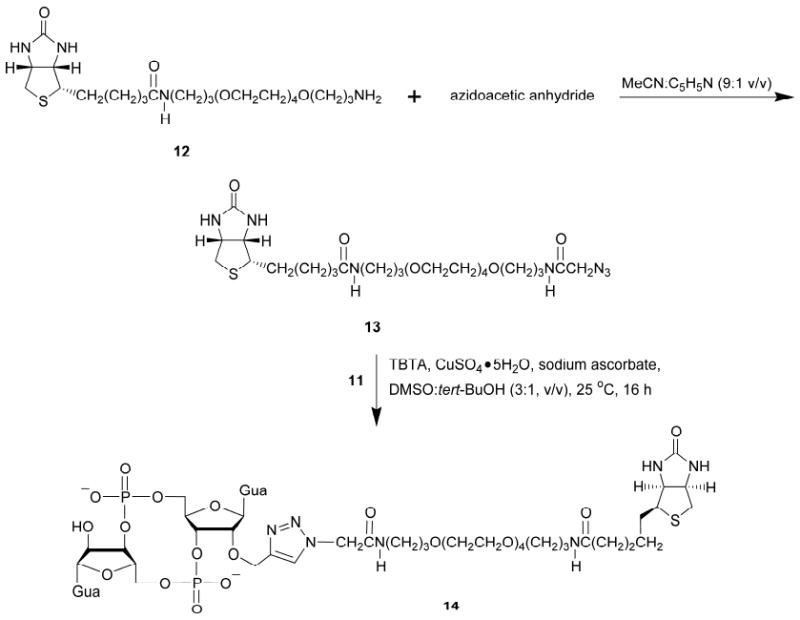

Various synthetic strategies have been implemented for the synthesis of c-di-GMP and its analogues. Indeed, in addition to the hydroxybenzotriazole phosphotriester method (7, 8), combinations of phosphoramidite and phosphotriester, (9-12) phosphoramidite and H-phosphonate (13) or phosphotriester and H-phosphonate (14, 15) methods have also been reported for this purpose. Interestingly, an enzymatic and a solid-phase approach to the synthesis of c-di-GMP have recently been described in the literature (16, 17). We now report a straightforward solution-phase synthesis of the propargylated c-di-GMP 10 using exclusively, for the first time, phosphoramidite chemistry. The synthetic strategy consists of exploiting commercially available starting materials (1 and 4) and clustering synthetic operations in order to minimize the number of purification steps (Schemes 1-3). As outlined in Scheme 4, synthesis of the biotinylated azide 13 from commercial aminoalkylated biotin amide 12 and conversion of 13 to the biotinylated c-di-GMP 14 via a copper(I)-catalyzed [3+2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction (CuAAC or click chemistry) (18, 19) are described in detail in this report.

Scheme 1.

3′-O-Acylation of the ribonucleoside 1 and 5′-O-deprotection of 2.a

a Keys: DMTr, 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl; Gua, guanin-9-yl; iBu, isobutyryl; Lev2O, levulinic anhydride; Lev, levulinyl.

Scheme 3.

Conversion of the diribonucleoside phosphotriester 6 to the propargylated c-di-GMP 11.a

a Conditions: (i) (i-Pr2N)2POCH2CH2CN, 1H-tetrazole (1.0 equiv at the rate of 0.25 equiv/15 min), MeCN, 1 h; (ii) 1H-tetrazole (2 equiv), MeCN, 16 h; (iii) concd aq NH3, 30 h, 25°C; (iv) Et3N•3HF, 20 h, 25°C. Keys: Gua, guanin-9-yl; iBu, isobutyryl; TBDMS, tert-butyldimethylsilyl.

Scheme 4.

Biotinylation of the propargylated c-di-GMP 10.a

a Keys: Gua, guanine-9-yl; TBTA, tris-(benzyltriazolylmethyl)amine.

Experimental Procedures

N2-Isobutyryl-3′-O-levulinyl-2′-O-propargyl guanosine (3)

To a solution of N2-isobutyryl-5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-O-propargyl guanosine (1, 1.73 g, 2.50 mmol) in dry pyridine (10 mL) was added levulinic anhydride (20, 21) (2.50 g, 10.0 mmol); the solution was stirred at ∼25 °C for 16 h and was then evaporated to a gummy material under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in CHCl3 (30 mL) and was vigorously mixed with water (15 mL). The organic layer was collected and evaporated under low pressure. The crude ribonucleoside 2 was dissolved in 80% AcOH (10 mL) in order to remove the 5′-protecting group; progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC, which revealed complete cleavage of the 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl (DMTr) ether after a reaction time of 3 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum to an oil, which was dissolved in CHCl3 (3 mL) and purified by chromatography on silica gel (∼40 g) using a gradient of MeOH (0 → 3%) in CHCl3. Fractions containing the ribonucleoside 3 were collected and evaporated under reduced pressure to give a white solid (1.12 mg, 2.28 mmol) in a yield of 91% based on the molar amount of ribonucleoside 1 that was used as the starting material. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.1 (bs, 1H), 11.7 (bs, 1H), 8.29 (s, 1H), 5.90 (d, 1H, J = 7.7 Hz), 5.38 (m, 2H), 4.83 (dd, 1H, J = 7.7, 7.7 Hz), 4.14 (m, 3H), 3.63 (m, 2H), 3.41 (t, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 2.77 (m, 2H), 2.76 (sept, 1H, J = 6.7 Hz), 2.56 (m, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 1.12 (d, 6H, J = 6.7 Hz). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 206.7, 180.1, 171.7, 154.6, 148.9, 148.4, 137.1, 119.8, 84.1, 83.9, 79.1, 78.7, 77.9, 71.4, 61.0, 57.6, 37.3, 34.7, 29.5, 27.5, 18.7. +ESI-HRMS: Calcd for C22H27N5O8 [M + H]+, 490.1932, found 490.1935.

The propargylated guanylyl(3′-5′)guanosine phosphotriester 6

To a stirred solution of pre-dried ribonucleoside 3 (970 mg, 2.00 mmol) and phosphoramidite 4 (1.94 g, 2.00 mmol) in anhydrous MeCN (20 mL) was added solid 1H-tetrazole (210 mg, 3.00 mmol). 31P NMR analysis of the reaction mixture showed, within 4 h at ∼25 ºC, the appearance of two singlets (δP = 140.7 and 139.5 ppm) corresponding to the expected diastereomeric diribonucleoside phosphite triesters. Addition of 5.5 M tert-butyl hydroperoxide in decane (730 μL) to the reaction mixture resulted in the conversion of the phosphite triesters to their diastereomeric phosphate triester derivatives 5 within 30 min. The solution was evaporated under vacuum to an oily residue, which was treated with a solution (40 mL) of 0.5 M hydrazine hydrate in pyridine:AcOH (3:2 v/v) for 15 min; 2,4-pentanedione (2 mL) was then added to the solution in order to quench unreacted hydrazine hydrate. The volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the reaction product was partitioned between CHCl3 (40 mL) and H2O (20 mL). The organic phase was collected and evaporated to dryness under vacuum; the remaining material was dissolved in CHCl3 (5 mL) and purified by chromatography on silica gel (∼40 g) using a gradient of MeOH (0 → 5%) in CHCl3. Fractions containing the 3′-deprotected dinucleoside phosphate triester were collected and evaporated under low pressure to give a yellowish powder, which was dissolved in of 80% AcOH (15 mL) and left stirring for 3 h at ∼25 °C. Hexanes (25 mL) was added to the vigorously stirred reaction mixture in order to extract the 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl alcohol side product. After phase separation, the lower layer was collected and evaporated to complete dryness under vacuum. The dry material was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (5 mL) and the solution was added dropwise to stirred hexanes (100 mL). The precipitate was filtered to give the diribonucleoside phosphate triester 6 (2.25 g, 1.76 mmol) as a white solid in a yield of 88% relative to the molar amount of ribonucleoside 3 that was used as starting material. 31P NMR (121 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ −1.96, −2.38. +ESI-HRMS: Calcd for C40H56N11O14PSi [M + H]+ 974.3588, found 974.3594.

The propargylated c-di-GMP 11

Vacuum-dried propargylated diribonucleoside phosphotriester 6 (973 mg, 1.00 mmol) and 2-cyanoethyl tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite (301 mg, 1.00 mmol) were dissolved in dry MeCN (20 mL) to which was added solid 1H-tetrazole (70 mg, 1.0 mmol) in four portions over a period of 1 h under an inert gas atmosphere. The solution was stirred for 3 h at ∼25 °C and 1H-tetrazole (140 mg, 2.00 mmol) was then added to the reaction mixture, which was left stirring for 16 h. Without any work-up, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (5.5 M in decane, 550 μL) was added to the stirred solution. After 30 min, the reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum to an oil, which was dissolved in CHCl3 (5 mL) and purified by chromatography on silica gel (∼30 g). The product eluted from the silica gel column when employing a gradient of MeOH (0 → 8%) in CHCl3. Fractions containing the propargylated c-di-GMP triester 10 were checked by TLC [Rf (CHCl3:MeOH 9:1 v/v) = 0.33], collected and evaporated under reduced pressure to give a white solid (435 mg, 400 μmol) in a yield of 40%. The purified c-di-GMP triester 10 (109 mg, 100 μmol) was treated with concentrated aqueous ammonia (3 mL) in a sealed glass vial for 30 h at ∼25 °C; excess aqueous ammonia was then evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The material left was dissolved in neat triethylamine trihydrofluoride (4.00 mL, 24.5 mmol) and the solution was allowed to stir for 20 h at ∼25 °C. The fully deprotected product was purified by RP-HPLC using a 5 μm Supelcosil LC-18S column (25 cm × 10 mm) according to the following conditions: starting from 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate pH 7.0, a linear gradient of 2.5% MeCN/min is pumped at a flow rate of 3 mL/min for 40 min. Fractions containing the product were collected and evaporated using a stream of air to give the propargylated c-di-GMP 11 in a near quantitative yield. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 10.78 (bs, 1H), 9.76 (bs, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.95 (s, 1H), 6.59 (bs, 4H), 5.85 (d, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 5.73 (d, 1H, J = 5.3 Hz), 4.88 (m, 1H), 4.73 (m 1H), 4.58 (t, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 4.53 (t, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.46 (dd, 1H, 2J = 15.2 Hz, 4J = 2.3 Hz), 4.38 (dd, 1H, 2J= 15.2 Hz, 4J = 2.3 Hz), 4.23-4.06 (m, 4H), 3.91 (m, 2H), 3.43 (t, 1H, 4J = 2.3 Hz). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 156.5, 153.9, 151.1, 150.7, 135.0, 134.7, 116.24, 116.16, 86.5, 85.1, 80.4 (d, JC-P = 9.2 Hz), 80.2 (d, JC-P = 5.7 Hz), 79.7, 78.4, 77.6, 72.6 (d, JC-P = 5.7 Hz), 72.0, 71.0, 62.8 (d, JC-P = 5.7 Hz), 62.5 (d, JC-P = 5.7 Hz), 57.7, 45.4, 8.44. 31P NMR (121 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ −0.29, −1.25. +ESI-HRMS: Calcd for C23H26N10O14P2 [M + H]+ 729.1178 found 729.1184.

The biotinylated azide 13

To a solution of commercial N-D-(+)-biotinyl-4,7,10,13,16-pentaoxa-1,19-diaminononadecane (12, 50 mg, 94 μmol) in 1 mL of MeCN:C5H5N (9:1 v/v) was added azidoacetic anhydride (35 mg, 0.19 mmol). The solution was stirred at ∼25 °C for 1 h and was then concentrated to an oil using a stream of argon. The crude product was purified by chromatography on silica gel (2 g) using a gradient of MeOH (0-10%) in CHCl3. Fractions containing the product were collected and evaporated under vacuum to give 13 as a solid (35 mg, 57 μmol, 61%). +ESI-HRMS: Calcd for C26H47N7O8S [M + H]+ 618.3280, found 618.3283.

The biotinylated c-di-GMP 14

To the propargylated c-di-GMP 11 (150 OD260) was added a solution of 10 mM biotinylated azide 13 (800 μL), 100 mM CuSO4 (120 μL) and 100 mM tris-(benzyltriazolylmethyl)amine (TBTA, 240 μL), each in DMSO:tert-BuOH (3:1 v/v). A solution of 400 mM sodium ascorbate in H2O (175 μL) was then added to the reaction mixture, which was left stirring at ∼25 °C for 16 h. The crude reaction product was purified by RP-HPLC under conditions identical to those described for the purification of the propargylated c-di-GMP 11. Fractions containing the product were collected and evaporated under a stream of air to give the biotinylated c-di-GMP 14 (93 OD260) in an isolated yield of 62%. 31P NMR (121 MHz, D2O): δ −1.73, −2.06. +ESI-HRMS: Calcd for C49H73N17O22P2S [M + H]+ 1346.4385, found 1346.4429; [M + 2H]2+ 673.7229, found 673.7229.

Results and Discussion

Our solution-phase approach to the synthesis of the biotinylated c-di-GMP conjugate 14 began with the preparation of the ribonucleoside building block 3 (Scheme 1) from the commercially available propargylated ribonucleoside 1, which was 3′-O-acylated by treatment with levulinic anhydride (20, 21) in dry pyridine. After extractive workup, the fully protected ribonucleoside 2 was treated with 80% AcOH in order to remove the 5′-DMTr group. The 5′-deprotected ribonucleoside was purified by chromatography on silica gel to give pure 3 in a yield of 91%. The ribonucleoside was characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopies and by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS).

The commercial availability of the 2′-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) ribonucleoside phosphoramidite 4 (Scheme 2) and the pervasive use of the click chemistry for labeling nucleosides and oligonucleotides with fluorophores, carbohydrates and other functional groups (22, 23) have been motivational in the development of our synthetic approach to the synthesis of 14. Indeed, the reaction of 4 with the 5′-hydroxyl function of ribonucleoside 3 in the presence of 1.5 molar equiv of 1H-tetrazole in anhydrous MeCN produced, after P(III) oxidation by tert-butyl hydroperoxide, the dinucleoside phosphate triester 5 (Scheme 2). Upon concentration of the reaction mixture to an oil, a solution of hydrazine hydrate in pyridine and acetic acid was added in order to remove the levulinyl group from the terminal 3′-hydroxyl of the diribonucleoside phosphate triester. The hydrazinolysis reaction was stopped by the addition of 2,4-pentanedione and, following an extractive workup, the reaction product was purified by silica gel chromatography. The 5′-DMTr group of the purified material was then cleaved under acidic conditions (80% AcOH) to give, after work-up and precipitation from hexanes, the propargylated diribonucleoside phosphate triester 6 in a yield of 88% relative to the molar amount of ribonucleoside building block 3 that was used as the starting material. This yield is excellent given that out of four synthetic operations only one purification step was performed. The dinucleoside phosphotriester 6 was characterized, as a mixture of two P-diastereomers, by 31P NMR spectroscopy and HRMS (see Experimental section). The purity of 6 was assessed by RP-HPLC (Figure 1) and was determined to be 95%.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of the diribonucleoside phosphotriester 6.a

a Conditions: (i) 3, 1H-tetrazole, MeCN, 2 h, 25°C; (ii) tert-BuOOH/decane, 30 min; (iii) hydrazine hydrate/AcOH/C5H5N, 15 min, then 2,4-pentanedione, 5 min; (iv) chromatography on silica gel; (v) 80% AcOH, 3 h, 25°C. Keys: DMTr, 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl; Gua, guanin-9-yl; iBu, isobutyryl; TBDMS, tert-butyldimethylsilyl; Lev, levulinyl.

Figure 1.

RP-HPLC analysis of the guanylyl(3′-5′)guanosine phosphotriester 6. a

aAnalytical chromatographic conditions are described in the Supporting Information under Materials and Methods. Peak heights were normalized to the highest peak, which was set to 1 arbitrary unit.

The preparation of the propargylated and fully protected c-di-GMP derivative 10 (Scheme 3) was carried out in MeCN by the phosphitylation of 6 with strictly one molar equivalent of 2-cyanoethyl tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite and solid 1H-tetrazole, which was added at the rate of 0.25 molar equivalent per 15 min under rigorously anhydrous conditions. Such a stoichiometry presumably favored the formation of the 5′-phosphoramidite 7 relative to that of the 3′-phosphoramidite 8 and 3′,5′-bis-phosphoramidite 9, the formation of which cannot conclusively be ruled out. The intramolecular cyclization of 7 and 8 was then performed by adding two molar equivalents of solid 1H-tetrazole to the initial phosphitylation reaction mixture. The concentration of the reagents, with the exception of 1H-tetrazole, was sufficiently low (∼50 mM) to favor intramolecular cyclization rather than intermolecular polymerization. The intramolecular cyclization reaction was allowed to proceed overnight (16 h) and was followed by the addition of a solution of tert-butyl hydroperoxide in decane in order to convert the newly formed phosphite triester function to its tetracoordinated phosphate triester state and complete the synthesis of 10. The crude product was purified by chromatography on silica gel to give an amorphous white solid in a yield of 40% based on the starting propargylated dinucleoside phosphate triester 6.

The modest yield of intramolecular cyclization may be attributed to a number of factors. The use of only one molar equivalent of 2-cyanoethyl tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite is necessary to minimize if not prevent the formation of 9, which otherwise would result in a commensurate loss of cyclic product in addition to residual unphosphitylated 6. Perhaps the most important factor contributing to a lower yield of 10 may be related to the presence of adventitious water in a relatively large volume of MeCN, which would lead to hydrolysis of the 1H-tetrazole-activated phosphoramidite functions of 7 and 8 and prevent intramolecular cyclization. However, these limitations, which are inherent to our approach to the synthesis of 10, are clearly outweighed by the simplicity and convenience of the method.

RP-HPLC analysis of 10 revealed the expected presence of four diastereomers, two for each chiral phosphate function (Figure 2A). The asymmetry of 10 in addition to the chirality of its two tetracoordinated phosphate esters contributed to the complexity of its 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectra. Indeed, the proton-decoupled 31P NMR analysis of 10, which revealed six out of theoretically eight signals, underscores the challenging characterization of 10 by spectroscopic techniques. In order to mitigate this difficulty, the strategy of converting 10 to the c-di-GMP 11 was adopted. Complete deprotection of 10 consisted of removing the N2-isobutyryl and 2-cyanoethyl phosphate protecting groups first by treatment with concentrated aqueous ammonia in a sealed glass vial over a period of 30 h at ambient temperature. Lastly, the cleavage of the 2′-O-TBDMS group was effected by reaction with triethylamine trihydrofluoride to give, near quantitatively, the propargylated c-di-GMP 11, as judged by RP-HPLC analysis of the deprotection reaction (Figure 2B). This analysis also revealed the purity of 11, which was determined to be 95%. The propargylated c-di-GMP 11 was adequately characterized by 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectroscopies and HRMS (see Experimental section).

Figure 2.

RP-HPLC analysis of the conversion of the propargylated c-di-GMP triester 10 to the propargylated c-di-GMP 11.

A: Chromatogram of the silica gel-purified propargylated c-di-GMP triester 10. B: Chromatogram of the propargylated c-di-GMP 11 that was obtained from silica gel-purified 10 after complete deprotection, which was effected by treatment with: (i) concentrated aqueous ammonia for 30 h at 25 °C; and (ii) triethylamine trihydrofluoride for 20 h at 25 °C. Analytical chromatographic conditions are described in the Supporting Information under Materials and Methods. Peak heights were normalized to the highest peak, which was set to 1 arbitrary unit.

The preparation of the biotinylated azide 13 was required for the biotinylation of 11 (Scheme 4). Acylation of the commercial aminoalkylated biotin derivative 12 with azidoacetic anhydride in a solution of 10% pyridine in MeCN over a period of 1 h at ambient temperature afforded 13 in moderate yield after purification. Azidoacetic anhydride was generated in situ from azidoacetic acid and N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide in THF under conditions similar to those employed for the preparation of levulinic anhydride (20, 21). Azidoacetic acid was prepared from the reaction of bromoacetic acid and sodium azide, as described in the literature (24). Given the inherent complexity of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of biotinylated azide 13, its characterization by HRMS was found to be the most informative.

The copper(I)-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition of 13 with the propargylated c-di-GMP 11 was performed essentially as reported by Berndl et al. (25). The biotinylated c-di-GMP 14 was purified by RP-HPLC and was isolated in a yield of 62%, which is based on the molar amount of 11 used as the starting material. Figure 3 illustrates the “click” conjugation of the biotinylated azide 13 with the propargylated c-di-GMP 11.

Figure 3.

RP-HPLC analysis of the “click” conjugation of the propargylated c-di-GMP 11 with the biotinylated azide 13.

A: Chromatogram of the propargylated c-di-GMP 11. B: Chromatogram of the purified biotinylated c-di-GMP 14 obtained from “click” conjugation of 11 with 13 under the conditions described in the Experimental section. Analytical chromatographic conditions are described in the Supporting Information under Materials and Methods.

Conclusion

The synthetic strategy for the synthesis of the propargylated c-di-GMP 10 reported herein is based on the use of commercial starting materials including the propargylated ribonucleoside 1 and the 2′-O-TBDMS ribonucleoside phosphoramidite 4. The absence of a vicinal hydroxyl function in 4 precluded the notorious migration of the TBDMS group (26) and formation of any isomeric side product when using this reagent. Phosphitylation of the propargylated diribonucleoside phosphate triester 6 when employing only one molar equivalent of commercial 2-cyanoethyl tetraisopropylphosphordiamidite led to the formation of 10, for the first time through exclusively phosphoramidite chemistry. The yield of 10 is perhaps lower than those reported using other cyclization procedures but the convenience and simplicity of our synthetic strategy prevail over other preparative synthetic approaches in terms of the availability of starting materials, minimization of potential side reactions and number of necessary purification steps. As mentioned above, the biological implications of the biotinylated c-di-GMP 14, in regard to identification and characterization of the proteins recognizing and binding to c-di-GMP, are currently being investigated and may provide valuable insight into their signaling pathways and bioactivity in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The results of these studies are beyond the scope of this report and will be communicated elsewhere. In this context, our straightforward approach to the synthesis of the propargylated c-di-GMP 11 is being exploited in the preparation of structural analogues of 11 having either one or two (2′-5′)phosphodiester linkages instead of the native (3′-5′)phosphodiester functions in order to assess whether their biotinylated conjugates may permit the identification of proteins that may or may not be similar to those associated with the recognition and binding of 11. This work is again based on the commercial availability of both the 3′-O-propargylated and 3′-O-TBDMS isomers of ribonucleoside 1 and ribonucleoside phosphoramidite 4, respectively. The results of these studies will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R21 ES016835 and RO1 AI058211 (C.S).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Materials and methods; 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the propargylated ribonucleoside 3 and c-di-GMP 11; 31P NMR spectra of the propargylated guanylyl(3′-5′)guanosine phosphotriester 6, fully protected c-di-GMP 10, c-di-GMP 11 and biotinylated c-di-GMP 14; mass spectra of 3, 6, 11, 13, and 14; TLC analysis of 10 and detailed preparations of levulinic anhydride and azidoacetic anhydride. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Literature Cited

- 1.Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y, Michaeli D, Weinberger-Ohana P, Mayer R, Braun S, de Vroom E, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Benziman M. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature. 1987;325:279–281. doi: 10.1038/325279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan H, Chen W. 3′,5′-Cyclic diguanylic acid: a small nucleotide that makes big impacts. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:2914–2924. doi: 10.1039/b914942m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karaolis DKR, Means TK, Yang D, Takahashi M, Yoshimura T, Muraille E, Philpott D, Schroeder JT, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Talbot BG, Brouillette E, Malouin F. Bacterial c-di-GMP is an immunostimulatory molecule. J Immunol. 2007;178:2171–2181. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McWhirter SM, Barbalat R, Monroe KM, Fontana MF, Hyodo M, Joncker NT, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Colonna M, Chen ZJ, Fitzgerald KA, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1899–1911. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science. 2010;328:1703–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1189801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross P, Mayer R, Weinhouse H, Amikam D, Huggirat Y, Benziman M, de Vroom E, Fidder A, de Paus P, Sliedregt LAJM, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH. The cyclic diguanylic acid regulatory system of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18933–18943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amiot N, Heintz K, Giese B. New approach for the synthesis of c-di-GMP and its analogues. Synthesis. 2006:4230–4236. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayakawa Y, Nagata R, Hirata A, Hyodo M, Kawai R. A facile synthesis of cyclic bis(3′→5′)diguanylic acid. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:6465–6471. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai R, Nagata R, Hirata A, Hayakawa Y. A new synthetic approach to cyclic bis(3′→5′)diguanilic acid. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003 3:103–104. doi: 10.1093/nass/3.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y. An improved method for synthesizing cyclic bis(3′-5′)diguanylic acid (c-di-GMP) Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2004;77:2089–2093. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyodo M, Sato Y, Hayakawa Y. Synthesis of cyclic bis(3′-5′)diguanylic acid (c-di-GMP) analogs. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:3089–3094. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. c-di-GMP displays a monovalent metal ion-dependent polymorphism. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16700–16701. doi: 10.1021/ja0449832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humes E, Yan H. Convenient synthesis of 3′,5′-cyclic diguanylic acid (cdiGMP) Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 2006;50:5–6. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrl003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan H, López Aguilar A. Synthesis of 3′,5′-cyclic diguanylic acid (cdiGMP) using 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-ethoxypiperidin-4-yl as a protecting group for 2′-hydroxy functions of ribonucleosides. Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2007;26:189–204. doi: 10.1080/15257770601112762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao F, Pasunooti S, Ng Y, Zhuo W, Lim L, Liu AW, Liang ZX. Enzymatic synthesis of c-di-GMP using a thermophilic diguanylate cyclase. Anal Biochem. 2009;389:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiburu I, Shurer A, Yan Lei, Sintim HO. A simple solid-phase synthesis of the ubiquitous bacterial signaling molecule, c-di-GMP and analogues. Mol BioSyst. 2008;4:518–520. doi: 10.1039/b719423d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. A stepwise Huisgen cycloaddition process: Copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective “ligation” of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tornøe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. Peptidotriazoles on solid phase: [1,2,3]-triazoles by regiospecific copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of terminal alkynes to azides. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassner A, Strand G, Rubinstein M, Patchornik A. Levulinic esters.Alcohol protecting group applicable to some nucleosides. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:1614–1615. doi: 10.1021/ja00839a077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo Z, Xue J. Levulinic anhydride. In: Paquette LA, Crich D, Fuchs PL, Molander G, editors. Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. 2nd. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 5961–5963. [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Sagheer AH, Brown T. Click chemistry with DNA. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1388–1405. doi: 10.1039/b901971p. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gramlich PME, Wirges CT, Manetto A, Carell T. Postsynthetic DNA modification through the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8350–8358. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802077. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyke JM, Groves AP, Morris A, Ogden JS, Dias AA, Oliveira AMS, Costa ML, Barros MT, Cabral MH, Moutinho AMC. Study of the thermal decomposition of 2-azidoacetic acid by photoelectron and matrix isolation infrared spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6883–6887. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berndl S, Herzig N, Kele P, Lachmann D, Li X, Wolfbeis OS, Wagenknecht HA. Comparison of a nucleosidic vs non-nucleosidic postsynthetic “Click”modification of DNA with base-labile fluorescent probes. Bioconj Chem. 2009;20:558–564. doi: 10.1021/bc8004864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaucage SL, Reese CB. Recent Advances in the Chemical Synthesis of RNA. In: Beaucage SL, Bergstrom DE, Herdewijn P, Matsuda A, editors. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 2.16.1–2.16.31. Chapter 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.