Abstract

The matrix glycoprotein, fibronectin, stimulates the proliferation of non–small cell lung carcinoma in vitro through α5β1 integrin receptor–mediated signals. However, the true role of fibronectin and its receptor in lung carcinogenesis in vivo remains unclear. To test this, we generated mouse Lewis lung carcinoma cells stably transfected with short hairpin RNA shRNA targeting the α5 integrin subunit. These cells were characterized and tested in proliferation, cell adhesion, migration, and soft agar colony formation assays in vitro. In addition, their growth and metastatic potential was tested in vivo in a murine model of lung cancer. We found that transfected Lewis lung carcinoma cells showed decreased expression of the α5 gene, which was associated with decreased adhesion to fibronectin and reduced cell migration, proliferation, and colony formation when compared with control cells and cells stably transfected with α2 integrin subunit in vitro. C57BL/6 mice injected with α5-silenced cells showed lower burden of implanted tumors, and a dramatic decrease in lung metastases resulting in higher survival as compared with mice injected with wild-type or α2 integrin–silenced cells. These observations reveal that recognition of host- and/or tumor-derived fibronectin via α5β1 is important for tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo, and unveil α5β1 as a potential target for the development of anti–lung cancer therapies.

Keywords: α5β1 integrin, fibronectin, Lewis lung carcinoma, lung cancer, short hairpin RNA shRNA

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

The matrix glycoprotein, fibronectin, stimulates the proliferation of non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) in vitro through α5β1 integrin receptor–mediated signals. However, the true role of fibronectin and its receptor in lung carcinogenesis in vivo remains unclear. These observations reveal that recognition of host and/or tumor-derived fibronectin via α5β1 integrin is important for tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo, and unveil α5β1 as a potential target for the development of anti–lung cancer therapies.

Lung carcinoma is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the United States, and its impact worldwide is enormous (1). Tobacco is considered a culprit in at least 90% of cases and, thus, represents the most important predisposing factor for lung cancer (2, 3). Despite advances in understanding the mechanisms involved in lung carcinogenesis, the development of new surgical procedures, and the use of new radio- and chemotherapeutic protocols, the 5-year survival rate for patients with lung cancer remains less than 15% (4). This underscores the desperate need for novel strategies for early detection, prevention, and treatment of this malignancy, but these await new insights into the pathogenesis of this disorder (4).

Tumor growth and invasion are not only the result of malignant transformation, but are also dependent on environmental influences from the surrounding stroma, local growth factors, and systemic hormones (5). In particular, the composition of the extracellular matrix is believed to affect malignant behavior, which might depend on the differentiation state of tumor cells (6, 7). Fibronectin, a well studied matrix glycoprotein, has been implicated in cancer biology since its discovery in the 1970s (8, 9). Today, it is well known that fibronectin is expressed by many tumor cells, and that, among the early signs of malignant transformation, is the fragmentation of pericellular fibronectin that is concomitant with an increase in fibronectin deposition in the peritumoral stroma (10, 11). Fibronectin is also increased in lung carcinoma, where there is differential expression of fibronectin splicing variants (12). The adhesion of lung carcinoma cells to fibronectin enhances tumorigenicity and confers resistance to apoptosis induced by standard chemotherapeutic agents in other systems (13). Our laboratory has demonstrated that the mitogenic effects of fibronectin in human lung carcinoma cells are dependent on the activation of key intracellular signals, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/Akt, extracellular signal–regulated kinases, and mammalian target of rapamycin pathways, and the induction of cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) expression (14–16). These events culminate in the inhibition of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., p21) and the induction of cyclins (e.g., cyclin D1), resulting in increased proliferation. We have also reported that fibronectin stimulates tumor cell expression of matrix metalloproteinases implicated in metastatic behavior (17). Fibronectin expression is increased in tobacco-related disorders; thus, these observations suggest that host-derived fibronectin might serve to promote lung carcinoma progression. However, tumor-derived fibronectin is also likely to play a role, because suppression of fibronectin expression in tumor cells via siRNA methods results in decreased proliferative capacity (18).

The studies described previously are tantalizing, but are limited to experiments in vitro that require confirmation in vivo. Unfortunately, fibronectin knockout mice are embryonic lethal, and, consequently, work in this area has been limited by the lack of animal models where fibronectin expression is amenable to manipulation (19). Even if the in vivo role of fibronectin in lung cancer biology were to be demonstrated, strategies targeting fibronectin for therapeutic purposes in humans would be limited by the relatively high concentrations of fibronectin found in mammalian organs and in plasma. Consequently, targeting fibronectin recognition by tumor cells represents a better approach.

Many of the cancer-promoting effects of fibronectin in cultured lung carcinoma cells are inhibited by blockade of the fibronectin integrin receptor, α5β1 (15, 16), a member of the superfamily of integrins involved in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, differentiation, wound healing, and altered invasive properties of tumor cells (20, 21). Antibodies and synthetic peptides capable of blocking fibronectin recognition through α5β1 inhibit fibronectin-induced proliferation in lung and other carcinoma cells, whereas reagents against collagen- and fibrin-binding integrins do not (15, 22). The α5β1, integrin, is generally not found in normal lung tissue, but is expressed in a considerable fraction of lung carcinomas (23), and its overexpression is associated with a more malignant phenotype, metastasis, and decreased survival (24). These observations raise the possibility of targeting fibronectin recognition via integrin α5β1 as an anti-cancer strategy. To this end, we turned to short hairpin RNA shRNA technology to establish lung carcinoma cell lines deficient in α5β1 receptor expression with the intention of testing their malignant behavior in vivo with a murine model of experimental lung cancer. Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells were tested since they have been traditionally used in animal models to study lung cancer progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The mouse integrin α5 or α2 subunit or control nontarget shRNA plasmid DNA constructs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Polyclonal antibody against integrin α5 (H-104), integrin β1 (M-106), and integrin α2 (H-293) subunits were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The polyclonal antibody against actin was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The Cell Titer 96 Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (MTT) kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Soft Agar Assay for Colony Formation kit was purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Fibronectin (derived from human fibroblasts) and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma, unless otherwise indicated.

Cell Culture and Generation of Transfected LLC Cells

The LLC cells were purchased from ATCC (CRL-1642; ATCC, Rockville, MD) and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 50 IU/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 μg amphotericin (complete medium) at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. LLC cells were permanently transfected with control, nontarget, α5 or α2 shRNA plasmid DNA. Briefly, LLC cells (2.3 × 107 cells/ml) were harvested, washed, and resuspended in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes, 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, and 6 mM dextrose at pH 7.05. The LLC cells were added to a 0.4-cm-gap cuvette along with 160 μg of control, nontarget, α5 or α2 shRNA plasmid DNA, and transfected with a Gene Pulser II electroporation apparatus with settings of 390 v, 500 μF (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). LLC cells were plated onto 75-mm2 tissue culture flasks, and shRNA-expressing cells were selected by the addition of 3 μg/ml puromycin antibiotic for a minimum of 2 weeks. To obtain individual clones, cells were serially diluted into 96-well tissue culture plates. Single colonies were subsequently tested for α5 mRNA and protein expression.

RT-PCR

LLC cells, wild-type (WT) or permanently transfected with control (consh), α2 (α2sh), or α5 shRNA plasmid (α5sh), were plated onto six-well plates (1 × 106 cells/ml), and incubated for 24 hours. Total RNA was extracted from LLC cells, and RT-PCR was performed as described previously (8, 9). Primers for RT-PCR reactions were as follows: mouse α5 forward primer (TGT CAC CGT CCT TAA TGG), reverse primer (CAT TGT AGC CGT CTT GGT); mouse α2 forward primer (TTA GGT TAC TCT GTG GC), reverse primer (ATC CAT GTT GAT GTC TG); mouse β1 forward primer (AAA TTG TGG GTG GTG C) reverse primer (TCC ATA AGG TAG TAG AG); and mouse 18S forward primer (GTG ACC AGA GCG AAA GCA), reverse primer (ACC CAC GGA ATC GAG AAA).

Western Blot Analysis

The procedure was performed as previously described (25). WT or transfected LLC cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were washed and lysed in homogenization buffer. The protein was added to an equal volume of 2× sample buffer, boiled for 4 minutes, and briefly centrifuged, and Western blot analysis was performed with 5% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, as previously described (8, 9). The blots were then washed, transferred to freshly made enhanced chemiluminescence solution (Amersham, Arlington, IL), and exposed to X-ray film. Protein bands were scanned with a GS-800 Calibrated laser densitometer (Bio-Rad).

Adhesion Assay

Culture plates (96 well) were coated with 100 μl of fibronectin (10 μg/ml), collagen (10 μg/ml), serum (10%), or plastic alone in coating buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 [pH 8.5]) overnight at 4°C. Plates were rinsed with PBS and blocked for 2 hours at 37°C with BSA blocking buffer (10 mg/ml BSA in PBS [pH 7.4]). WT or shRNA-transfected LLC cells (2.5 × 105 cells/ml) were added to 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were washed from the dishes after 2 hours, and adherent cells were quantified by using a colorimetric-type assay that detects the intracellular enzyme, hexosaminidase, by using the substrate p-nitrophenyl N-Acetyl β-D-glucosaminide (7.5 mM in 0.1 M Na Citrate [pH 5.0]) at an optical density of 405 nm.

Wound Healing–Migration Assay

WT control or α5 shRNA–transfected LLC cells were plated and grown to 90% confluency in two-well chambers slides (Falcon Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) in media containing Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium with 10% FBS. Cells were washed with complete medium containing 1% FBS three times to remove any cell debris. A sterile 200-μl pipette tip was used to create a wound by removing cells from the surface of the chamber slide in three separate locations within each well. Cells were allowed to recover for an additional 48 hours. Afterwards, wounds were photographed, and the data presented are representative of three independent experiments.

Soft Agar Assay for Colony Formation

The soft agar assay kit was purchased from Chemicon International (catalog no. ECM570). The 0.8% base agar was prepared, mixed with an equal amount of cell culture media, and added to a six-well culture plate (500 μl/well). The plates were placed at 4°C for 20 minutes to allow the agarose to gel. Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes before the addition of the 0.4% top agar/cell solution prepared by mixing base agar (0.8%, 50 ml) with 50 ml of cell culture media. Top agar was incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes before the addition of LLC control nontarget or α5 shRNA transfected cells (2.5 × 103 cells/well) and plated (500 μl/well) onto culture plates containing base agar. Cells were incubated for 21 days at 37°C with 5% CO2 until colonies formed. Cells were maintained with cell culture media (500 μl/well) at least twice per week. After 21 days, colonies were photographed and quantified with cell stain solution or cell quantification solution and measured at 490 nM.

Cell Viability Assay

The procedure was performed as previously described (25). WT or transfected LLC cells (1 × 104 cells/ml) were added to 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 or 48 hours. Afterwards, the luminescence of viable cells was detected with Cell Titer-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Promega). Quantification was performed with a Labsystems Luminoskan Ascent Plate Luminometer (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

Subcutaneous Injection of LLC/α5sh Cells into C57BL/6 Mice

Experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Emory University, Atlanta, GA and University of Louisville, Louisville, KY WT LLC cells or cells stably transfected with control nontarget (LLC/Consh), α5 shRNA (LLC/α5sh), or α2 shRNA (LLC/α2sh) were injected subcutaneously (1 × 106 cells/100 μl sterile PBS) into the flank area of C57BL/6 mice, and tumor burden was observed for up to 6 weeks. Tumor growth was monitored weekly and measured (length × width × height) with calipers for up to 6 weeks after subcutaneous injection of transfected LLC cells. Investigators were blinded to the intervention during the measurements.

Intravenous Injection of LLC/α5sh Cells into C57BL/6 Mice

C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously via tail vein with WT or LLC cells transfected with control nontarget or α5 shRNA LLC cells (1 × 105 cells/100 μl sterile PBS) and monitored weekly for up to 4 weeks. Afterwards, mice were killed, followed by tracheostomy and en bloc isolation of the lungs. Lung samples were inflated at standard pressure, fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded, and sectioned (5 μm) for histological analysis. Slides were washed in dH2O for 5 minutes and counterstained with hematoxylin. Again, investigators were blinded to the interventions during the measurements.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as averages (+SD). Differences were analyzed by the Student's t test (two-sided), and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier survival curve were used for the overall survival analysis.

RESULTS

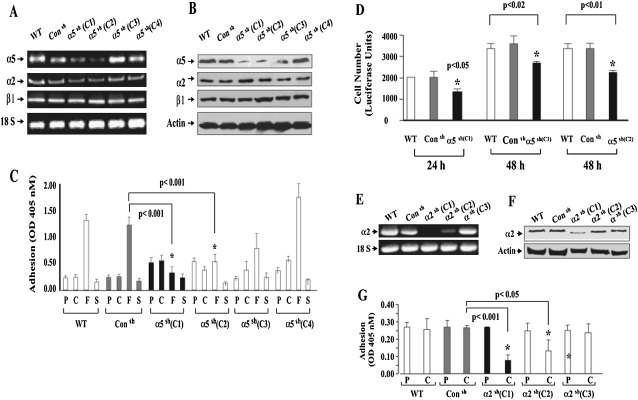

Silencing α5β1 Inhibits LLC Tumor Cell Adhesion to Fibronectin, Diminishes Cell Migration and Growth, and Reduces Colony Formation in Soft Agar

LLC cells transfected with shRNA against the α5 subunit of the α5β1 integrin showed a significant decrease in the expression of the α5 integrin subunit, as determined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis (Figures 1A and 1B, clone 1 and 2), whereas other α5 shRNA–transfected clones or cells transfected with control shRNA remained less affected. Thus, clone 1 and clone 2 LLC cells were used for further studies and are referred to hereafter as LLC/α5sh cells, unless otherwise indicated. Note that other integrin receptor mRNAs and proteins, such as those coding for α2 or β1 integrin subunits, were not affected (Figures 1A and 1B). To test the functional importance of decreased α5 integrin expression, LLC WT cells, LLC/Consh, or LLC/α5sh cells were cultured in vitro onto fibronectin-coated culture plates. As expected, two LLC/α5sh clones, C1 and C2, both demonstrating very low expression levels of α5 integrin, showed an impaired ability to adhere to fibronectin when compared with controls. However, these cells were able to adhere to uncoated or serum- and collagen type I–coated culture plates as effectively as WT cells (Figure 1C). Not surprising, adhesion to fibronectin by other LLC/α5sh clones, C3 and C4, both demonstrating little or no change in α5 integrin expression levels, adhered to fibronectin similarly to WT or control LLC cells. Furthermore, the reduction in the expression of the α5β1 integrin in the LLC/α5sh cells was also related to a reduction in the cell's ability to proliferate (Figure 1D). We also tested the ability of another member of the integrin family, the α2 integrin subunit, which is involved in cell–matrix interactions as it relates to cell binding to the matrix molecule, collagen. LLC cells permanently transfected with α2 shRNA (LLC/α2sh) also showed a significant decrease in integrin mRNA and protein expression, as demonstrated by RT-PCR and Western Blot analysis (Figures 1E and 1F). In vitro adhesion studies showed that the reduction in α2 integrin expression was able to reduce significantly the ability of the LLC cells to bind to collagen-coated culture plates as compared with WT or LLC/Consh cells (Figure 1G, clone 1).

Figure 1.

Silencing α5 with shRNA inhibits Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) tumor cell adhesion to fibronectin and diminishes cell growth. (A and B) Total RNA and proteins were isolated from wild-type (WT) or LLC cells permanently transfected with control (LLC/Consh) or α5 shRNA plasmid (2.3 × 107 cells/ml) (LLC/α5sh; C1, clone 1; C2, clone 2; C3, clone 3; C4, clone 4). Afterward, RT-PCR (A) and Western blot analysis (B) were performed. Note that LLC cells stably transfected with α5 shRNA (LLC/α5sh) showed reduced expression of α5 as determined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, whereas cells transfected with control shRNA remained unaffected. (C) WT or transfected LLC cells (2.5 × 105 cells/ml) were added to 96-well plates coated with plastic alone (P), collagen (C; 10 μg/ml), fibronectin (F; 10 μg/ml), or serum (S; 10%), and incubated at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were washed from the dishes after 1 hour, and adherent cells were quantified by using a colorimetric-type assay that detects the intracellular enzyme, hexosaminidase, at an optical density of 405 nm (OD405). Note that LLC/α5sh cells (C1 and C2) showed impaired ability to adhere to fibronectin when compared with controls (*P < 0.01), but they bound to uncoated (P), serum-coated (S), and collagen type I–coated (C) plates as effectively as WT control shRNA transfected cells. (D) WT or transfected LLC cells (1 × 104 cells/ml) were added to 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 or 48 hours. Afterward, cell proliferation was measured by the Cell Titer-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay. Quantification was performed using a Labsystems Luminoskan Ascent Plate Luminometer. Note that LLC/α5sh cells were able to proliferate, albeit at a reduced rate (30–43%; P < 0.02) at 24 and 48 hours as compared with WT or LLC/Consh cells. (E and F) Total RNA and proteins were isolated from WT or LLC cells permanently transfected with control (LLC/Consh) or α2 shRNA plasmid (2.3 × 107 cells/ml) (LLC/α2sh; C1, clone 1; C2, clone 2; C3, clone 3). Afterward, RT-PCR (E) and Western blot analysis (F) were performed. Note that LLC cells stably transfected with α2 shRNA (LLC/α5sh C1) showed reduced expression of α2, as determined by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis, whereas cells transfected with control shRNA (Consh) remained unaffected. (G) WT or transfected LLC cells (2.5 × 105 cells/ml) were added to 96-well plates coated with plastic alone (P) or collagen (C; 10 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were washed from the dishes after 1 hour, and adherent cells were quantified by using a colorimetric-type assay that detects the intracellular enzyme, hexosaminidase, at OD405. Note that LLC/α2sh cells (C1 and C2) showed impaired ability to adhere to collagen (C) when compared with WT or Consh controls (*P < 0.01), but LLC/α2sh C3 bound to uncoated (P) and collagen type I–coated (C) plates as effectively as WT or Consh-transfected cells.

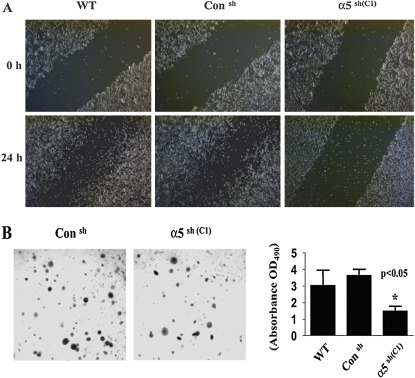

When compared with WT or control shRNA LLC cells, LLC/α5sh cells were also found to have a significantly reduced ability to migrate on fibronectin-coated plates (Figure 2A) and to form colonies in soft agar (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Silencing α5 with shRNA inhibits LLC tumor cell migration and reduces colony formation in soft agar. (A) WT, LLC/Consh, and LLC/α5sh cells were plated and grown to 90% confluence in two-well chamber slides (Falcon Becton Dickinson). Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium with 10% FBS media was removed, and cells were washed three times with fresh complete medium containing 1% FBS to remove cell debris. The plated cells were scraped with a sterile 200-μl pipette tip in three separate locations on each well, and cells were allowed to recover for an additional 24 hours. Afterwards, the wound sites (area cleared of cells in the center of the scraped area) were observed and photographed. The data presented are representative of three independent experiments. (B) LLC/Consh or LLC/α5sh cells (C1, 2.5 × 103 cells/well) were mixed with top agar (0.8%, 50 ml) and added to six-well plates containing base agar according to the manufacturer's instructions (ECM570; Chemicon International). Cells were incubated for 21 days in cell culture media (500 μl/well) at 37°C with 5% CO2 until colonies formed. Colonies were visualized by incubating the cells with staining solution, and stained colonies were observed and counted with a microscope. Note that LLC/α5sh cells (C1) showed the formation of smaller and more dispersed colonies. The right panel bar graph represents the results obtained from cell quantification solution and measured by spectrophotometer reading at OD490. *Significant difference as compared with the control untreated cells (P < 0.05).

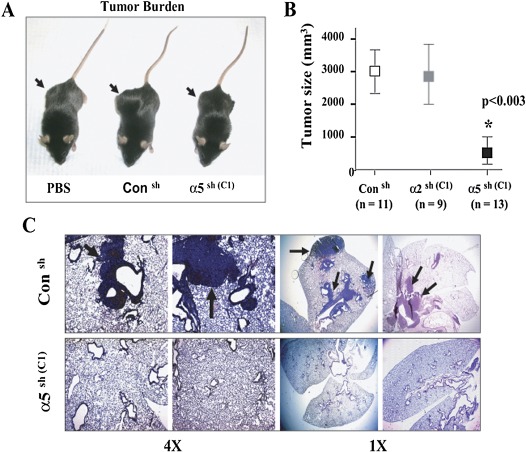

Animals Injected Subcutaneously with LLC/α5sh Cells Produce Smaller Tumors

Having established and characterized the properties of the LLC/α5sh and LLC/α2sh cells in vitro, we then proceeded to evaluate their function in vivo. Here, C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with WT LLC cells, LLC/Consh, LLC/α2sh (clone C1), or with LLC/α5sh cells (clone C1), and tumor formation was followed for up to 6 weeks. All the mice transfected with LLC/α5sh cells failed to develop any noticeable subcutaneous tumors (Figure 3A), as reflected by the significant reduction in tumor size measurements (Figure 3B) when compared with LLC/Consh and LLC/α2sh. In addition, mice transfected with LLC/α5sh cells did not show signs of any significant metastasis of tumor cells to the lung tissue (Figure 3C). In contrast, animals injected with the same number of LLC/α2sh (data not shown) and LLC/Consh cells demonstrated large subcutaneous tumors, as well as a significant amounts of lung metastases (Figures 3A–3C).

Figure 3.

Animals injected with LLC/α5sh cells produce smaller subcutaneous tumors and less lung metastasis. (A) C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with PBS vehicle alone or with LLC/Consh or LLC/α5sh cells (C1, 1 × 106 cells), and tumor burden was monitored weekly with calipers for up to 6 weeks. Animals injected with LLC/α5sh or vehicle alone (PBS) failed to develop subcutaneous tumors. In contrast, animals injected with LLC/Consh or LLC/α2sh cells (C1, data not shown) showed large subcutaneous tumors. (B) Subcutaneous tumors developed in C57BL/6 mice injected with LLC/Consh, LLC/α2sh (C1), or LLC/α5sh cells (C1) (1 × 106 cells) were measured after 6 weeks with a digital caliper. Tumor size is expressed in cubic millimeters. LLC/α5sh-injected mice developed significantly smaller tumors as compared with mice injected with LLC/Consh or LLC/α2sh cells (*P < 0.003). (C) Mice injected subcutaneously with LLC/Consh or LLC/α5sh cells (C1) for 6 weeks were killed, followed by tracheostomy and en bloc isolation of the lungs. Lung samples were inflated at standard pressure, fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded, and sectioned (5 μm) for histological analysis. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. The arrows indicate tumors.

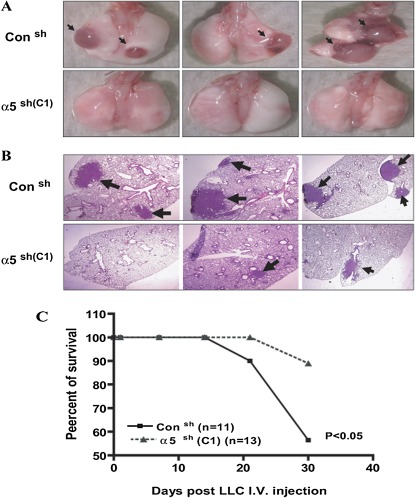

Animals Injected Intravenously with LLC/α5sh Cells Develop Fewer Lung Tumors and Exhibit Higher Survival

The above studies reveal that the down-regulation of α5β1 integrin expression in tumor cells results in inhibition of tumor progression in vivo. However, the near absence of subcutaneous tumors in animals injected with LLC/α5sh cells prevented us from examining the role of this integrin in metastasis and lung invasion. Therefore, we engaged in additional experiments in which LLC/α5sh cells were injected intravenously to further define the role of the α5 integrin in tumor cell invasion. For this, C57BL/6 mice were injected via tail vein with either LLC/Consh or LLC/α5sh cells (1 × 105), and followed for up to 4 weeks. As expected, animals injected with LLC/Consh cells developed numerous tumors that were evident by gross examination of the lungs (Figure 4A). In contrast, the lungs of animals injected with LLC/α5sh cells showed significantly smaller tumors in most cases, or no tumors at all (Figures 4A and 4B). Most importantly, animals injected with LLC/Consh cells showed decreased survival when compared with those injected with LLC/α5sh cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Animals injected intravenously with LLC/α5sh cells develop fewer lung tumors and exhibit higher survival. (A) C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with LLC/Consh or LLC/α5sh cells (C1) (1 × 105 cells) and monitored daily for up to 4 weeks. Afterward, mice were killed, followed by tracheostomy and en bloc isolation of the lungs. Animals injected with LLC/α5sh (C1) failed to develop noticeable lung tumors. In contrast, animals injected with LLC/Consh cells showed large lung tumors, as evident by gross examination of the lungs. (B) Mice injected intravenously with LLC/Consh or LLC/α5sh (C1) cells for 4 weeks were killed, followed by tracheostomy and en bloc isolation of the lungs. Lung samples were inflated at standard pressure, fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded, and sectioned (5 μm) for histological analysis. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. The arrows indicate tumor areas. Note that no tumor or smaller tumors were found in the LLC/α5sh cells (C1) group as compared with the LLC/Consh. (C) C57BL/6 mice injected intravenously with LLC/Consh cells demonstrated a significant decrease in survival when compared with animals injected with LLC/α5sh (C1) cells after 4 weeks, as demonstrated by the Kaplan-Meier survival curve (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that down-regulation of α5β1 expression in LLC cells inhibits tumor growth and prevents lung metastasis in vivo. This work adds to a significant body of literature that implicates the α5β1 integrin in the pathogenesis of lung and other cancers (22, 26–28). For example, one report showed that volociximab, a chimeric human IgG4 version of the α5β1 integrin function–blocking murine antibody IIA1, inhibited vessel formation in animal models, highlighting the potential use of antiangiogenic therapies. For this reason, this compound is being tested in early clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors (26, 29). Similar to volociximab, a blocking anti-mouse α5β1 integrin antibody inhibited angiogenesis and impeded tumor growth in multiple animal models, and this inhibition correlated with a concomitant decrease in vessel density (28). More recently, another study showed that treatment with an anti–α5β1 integrin antibody significantly reduced tumor burden and metastasis, and increased survival when compared with IgG treatment in a model of ovarian cancer (27). However, these studies focused on angiogenesis, and none evaluated the contribution of α5β1 integrin expressed by the tumor cells.

Because the α5β1 integrin recognizes fibronectin, our findings point to fibronectin as an important modulator of tumor progression, and suggest a critical role for fibronectin–α5β1 interactions in tumor cells. Tumor cells silenced for α5 showed mild decreases in proliferation and a significant reduction in colony formation in soft agar and in migration. However, it is important to emphasize that these tumor cells remained viable, that their proliferative capacity was not severely affected, that their adhesion to other matrix components was not compromised, and that they showed no changes in their expression of the apoptosis markers tested. Therefore, despite a decrease in proliferation, it is conceivable that this defect could be overcome in vivo (e.g., by other matrices or growth factors). Consequently, we were compelled to confirm the role of tumor cell α5β1 integrin in an animal model. Our studies, however, do not necessarily define the exact mechanisms by which this intervention affects tumor progression in vivo. Decreased viability and angiogenesis is possible (30–32).

These data might seem contradictory to other reports showing that malignant potential and metastatic ability appear to correlate with a decrease (not an increase) in fibronectin expression (33, 34). For example, in murine mammary adenocarcinomas, down-regulation of fibronectin gene transcription correlated with increased metastatic potential (33). Similarly, others have suggested that tumor cells overexpressing α5β1 integrin are less tumorigenic than their parent cells (34), and that this integrin is not important in the context of spontaneous tumor formation (35). We believe that these seemingly disparate observations are explained by the types of tumors and tissues tested. Furthermore, it is likely that fibronectin and α5β1 integrin play different roles in malignant transformation, invasion, and metastases, processes that are linked mechanistically, but that are distinct from one another. Integrin α5β1 receptors might promote carcinoma progression once established by inducing intracellular signals that stimulate the expression of genes involved in cell cycle progression and inhibit apoptosis, while inhibiting genes involved in tumor suppression. On the other hand, a decrease in the expression of fibronectin and/or α5β1 integrin might be needed to promote detachment of tumor cells from their substrate and for migration to and invasion of other tissues, thereby enhancing metastases. Considering these scenarios, one would predict that increased expression of fibronectin and α5β1 integrin might promote growth, while at the same time altering the metastatic potential of tumors. This might explain some of the results obtained with “super fibronectin,” a polymerized version of fibronectin induced by treating soluble fibronectin with the III1-C fibronectin peptide “anastellin.” The treatment of animals with these agents results in decreased metastases, as well as reduced tumor growth (36). However, the exact mechanisms for these effects remain unclear in view of the fact that anastellin also polymerizes fibrinogen. Finally, this work, and that of others, suggests that this and other β1 matrix–binding integrins other than α2β1 might play roles in the pathobiology of lung carcinoma (30, 31); we are currently testing other candidates by the approach discussed here. However, one must be careful when engaging in studies designed to evaluate the role of the β1 integrin subunit by our approach, as silencing β1 integrin would result in the down-regulation of all β1-related integrins, thereby rendering the interpretation of the results very difficult. Furthermore, in our study, although targeting α5 resulted in a reduction in cell migration and proliferation in vitro, the effect was not sufficient to explain the overwhelming inhibition of tumor progression observed in vivo, thus allowing for adequate evaluation lung invasion in the animal model; this may not be possible in β1-silenced cells. This, together with the results on α5 integrin in migration in LLC cells, highlights the critical role of the functional α5β1 integrin in these processes. Note that there were few metastatic foci in the lungs of animals injected intravenously with LLC/shα5 cells; this suggests that signals other than α5β1-mediated signaling may also play a role in mediating tumor foci formation and metastasis.

Taken together, this work adds to a significant body of literature that implicates α5β1 integrins in the pathogenesis of cancer (22, 27, 37, 38). Furthermore, because this integrin recognizes fibronectin, our findings point to fibronectin as an important modulator of tumor progression. Lung tumor cells have been shown to be surrounded by an extensive stroma of extracellular matrix at both primary and metastatic sites that contains fibronectin, laminin, and collagen IV (39). These and other studies, some from our own laboratory, suggest that excessive deposition of fibronectin (as well as differences in the relative content of fibronectin splicing variants) may promote tumor progression (15, 40). As stated previously, adhesion of lung cancer cells to fibronectin, laminin, and collagen IV through β1 integrins enhanced tumorigenicity and conferred resistance to apoptosis (39). Thus, overexpression of fibronectin in lung could render the host susceptible to accelerated tumor growth and progression in the setting of oncogenic transformation. This is intriguing, considering that the expression of fibronectin is increased in the lungs of patients with tobacco exposure, asbestosis exposure, and other chronic lung disorders, which are characterized by increased incidence of lung cancer (41, 42). In addition, nicotine, a major component of tobacco that stimulates lung carcinoma proliferation, was recently shown to stimulate fibronectin expression in lung (43), as well as in tumor cells (44); in the latter study, nicotine-induced tumor cell proliferation was related to the expression of tumor-derived fibronectin (44). Future studies will explore the molecular mechanisms by which knockdown of α5β1 integrin affects lung cancer cell growth in vivo (14, 16). Nevertheless, strategies targeting integrin receptors are under investigation, and include RGD peptides coupled with polyethylenimine (PEI) PEI, phages displaying Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) RGD-containing peptides, and a polymeric form of fibronectin (super fibronectin), among others (45–47). Unfortunately, much of this work is being performed in models that are unrelated to lung carcinoma. This report emphasizes the need to test these and related agents in this and other lung cancer models.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA123104 (S.W.H.) and CA116812 (J.R.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0375OC on January 15, 2010

Author Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:225–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landi MT, Dracheva T, Rotunno M, Figueroa JD, Liu H, Dasgupta A, Mann FE, Fukuoka J, Hames M, Bergen AW, et al. Gene expression signature of cigarette smoking and its role in lung adenocarcinoma development and survival. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant A, Cerfolio RJ. Differences in epidemiology, histology, and survival between cigarette smokers and never-smokers who develop non–small cell lung cancer. Chest 2007;132:185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilligan D, Nicolson M, Smith I, Groen H, Dalesio O, Goldstraw P, Hatton M, Hopwood P, Manegold C, Schramel F, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable non–small cell lung cancer: results of the MRC LU22/NVALT 2/EORTC 08012 multicentre randomised trial and update of systematic review. Lancet 2007;369:1929–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirtenlehne K, Pec M, Kubista E, Singer CF. Extracellular matrix proteins influence phenotype and cytokine expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Eur Cytokine Netw 2002;13:234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutierrez-Fernandez A, Fueyo A, Folgueras AR, Garabaya C, Pennington CJ, Pilgrim S, Edwards DR, Holliday DL, Jones JL, Span PN, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase–8 functions as a metastasis suppressor through modulation of tumor cell adhesion and invasion. Cancer Res 2008;68:2755–2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zijlstra A, Lewis J, Degryse B, Stuhlmann H, Quigley JP. The inhibition of tumor cell intravasation and subsequent metastasis via regulation of in vivo tumor cell motility by the tetraspanin cd151. Cancer Cell 2008;13:221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hynes RO, Yamada KM. Fibronectins: multifunctional modular glycoproteins. J Cell Biol 1982;95:369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritzenthaler JD, Han S, Roman J. Stimulation of lung carcinoma cell growth by fibronectin–integrin signalling. Mol Biosyst 2008;4:1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labat-Robert J. Fibronectin in malignancy. Semin Cancer Biol 2002;12:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams CM, Engler AJ, Slone RD, Galante LL, Schwarzbauer JE. Fibronectin expression modulates mammary epithelial cell proliferation during acinar differentiation. Cancer Res 2008;68:3185–3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyama F, Hirohashi S, Shimosato Y, Titani K, Sekiguchi K. Oncodevelopmental regulation of the alternative splicing of fibronectin pre-messenger RNA in human lung tissues. Cancer Res 1990;50:1075–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rintoul RC, Sethi T. Extracellular matrix regulation of drug resistance in small–cell lung cancer. Clin Sci 2002;102:417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Wingerd B, Rivera HN, Roman J. Extracellular matrix fibronectin increases prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4 in lung carcinoma cells through multiple signaling pathways: the role of AP-2. J Biol Chem 2007;282:7961–7972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han S, Sidell N, Roser-Page S, Roman J. Fibronectin stimulates human lung carcinoma cell growth by inducing cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression. Int J Cancer 2004;111:322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han S, Khuri FR, Roman J. Fibronectin stimulates non–small cell lung carcinoma cell growth through activation of akt/mammalian target of rapamycin/S6 kinase and inactivation of LKB1/AMP-activated protein kinase signal pathways. Cancer Res 2006;66:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Sitaraman SV, Roman J. Fibronectin increases matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression through activation of c-FOS via extracellular-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways in human lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 2006;281:29614–29624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaggioli C, Robert G, Bertolotto C, Bailet O, Abbe P, Spadafora A, Bahadoran P, Ortonne JP, Baron V, Ballotti R, et al. Tumor-derived fibronectin is involved in melanoma cell invasion and regulated by V600E B-Raf signaling pathway. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:400–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin. Development 1993;119:1079–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akiyama SK. Integrins in cell adhesion and signaling. Hum Cell 1996;9:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuwada SK, Kuang J, Li X. Integrin alpha5/beta1 expression mediates HER-2 down-regulation in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2005;280:19027–19035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murillo CA, Rychahou PG, Evers BM. Inhibition of alpha5 integrin decreases PI3K activation and cell adhesion of human colon cancers. Surgery 2004;136:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adachi M, Taki T, Higashiyama M, Kohno N, Inufusa H, Miyake M. Significance of integrin alpha5 gene expression as a prognostic factor in node-negative non–small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito T, Kimura M, Kawasaki T, Sato S, Tomita Y. Correlation between integrin alpha 5 expression and the malignant phenotype of transitional cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 1996;73:327–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han S, Ritzenthaler JD, Wingerd B, Roman J. Activation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor beta/delta (PPARbeta/delta) increases the expression of prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4: the roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta. J Biol Chem 2005;280:33240–33249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuwada SK. Drug evaluation: volociximab, an angiogenesis-inhibiting chimeric monoclonal antibody. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2007;9:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawada K, Mitra AK, Radjabi AR, Bhaskar V, Kistner EO, Tretiakova M, Jagadeeswaran S, Montag A, Becker A, Kenny HA, et al. Loss of E-cadherin promotes ovarian cancer metastasis via alpha 5-integrin, which is a therapeutic target. Cancer Res 2008;68:2329–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhaskar V, Zhang D, Fox M, Seto P, Wong MH, Wales PE, Powers D, Chao DT, Dubridge RB, Ramakrishnan V. A function blocking anti-mouse integrin alpha5beta1 antibody inhibits angiogenesis and impedes tumor growth in vivo. J Transl Med 2007;5:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramakrishnan V, Bhaskar V, Law DA, Wong MH, DuBridge RB, Breinberg D, O'Hara C, Powers DB, Liu G, Grove J, et al. Preclinical evaluation of an anti-alpha5beta1 integrin antibody as a novel anti-angiogenic agent. J Exp Ther Oncol 2006;5:273–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ordonez C, Zhai AB, Camacho-Leal P, Demarte L, Fan MM, Stanners CP. GPI-anchored CEA family glycoproteins CEA and CEACAM6 mediate their biological effects through enhanced integrin alpha5beta1–fibronectin interaction. J Cell Physiol 2007;210:757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong L, Roybal J, Chaerkady R, Zhang W, Choi K, Alvarez CA, Tran H, Creighton CJ, Yan S, Strieter RM, et al. Identification of secreted proteins that mediate cell–cell interactions in an in vitro model of the lung cancer microenvironment. Cancer Res 2008;68:7237–7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui R, Ohashi R, Takahashi F, Yoshioka M, Tominaga S, Sasaki S, Gu T, Takagi Y, Takahashi K. Signal transduction mediated by endostatin directly modulates cellular function of lung cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Sci 2007;98:830–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urtreger AJ, Werbajh SE, Verrecchia F, Mauviel A, Puricelli LI, Kornblihtt AR, Bal de Kier Joffe ED. Fibronectin is distinctly downregulated in murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells with high metastatic potential. Oncol Rep 2006;16:1403–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou GF, Ye F, Cao LH, Zha XL. Over expression of integrin alpha 5 beta 1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line suppresses cell proliferation in vitro and tumorigenicity in nude mice. Mol Cell Biochem 2000;207:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taverna D, Ullman-Cullere M, Rayburn H, Bronson RT, Hynes RO. A test of the role of alpha5 integrin/fibronectin interactions in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 1998;58:848–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi M, Ruoslahti E. A fibronectin fragment inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:620–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu SL, Cheng CC, Shi YR, Chiang CW. Proteolysis of integrin alpha5 and beta1 subunits involved in retinoic acid–induced apoptosis in human hepatoma HEP3B cells. Cancer Lett 2001;167:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morozevich GE, Kozlova NI, Cheglakov IB, Ushakova NA, Preobrazhenskaya ME, Berman AE. Implication of alpha5beta1 integrin in invasion of drug-resistant MCF-7/ADR breast carcinoma cells: a role for MMP-2 collagenase. Biochemistry 2008;73:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sethi T, Rintoul RC, Moore SM, MacKinnon AC, Salter D, Choo C, Chilvers ER, Dransfield I, Donnelly SC, Strieter R, et al. Extracellular matrix proteins protect small cell lung cancer cells against apoptosis: a mechanism for small cell lung cancer growth and drug resistance in vivo. Nat Med 1999;5:662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Astrof S, Crowley D, George EL, Fukuda T, Sekiguchi K, Hanahan D, Hynes RO. Direct test of potential roles of EIIIA and EIIIB alternatively spliced segments of fibronectin in physiological and tumor angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:8662–8670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohbayashi H. Matrix metalloproteinases in lung diseases. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2002;3:409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakstad B, Boye NP, Lyberg T. Distribution of bronchoalveolar cells and fibronectin levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from patients with lung disorders. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1990;50:587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roman J, Ritzenthaler JD, Gil-Acosta A, Rivera HN, Roser-Page S. Nicotine and fibronectin expression in lung fibroblasts: implications for tobacco-related lung tissue remodeling. FASEB J 2004;18:1436–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y, Ritzenthaler JD, Roman J, Han S. Nicotine stimulates human lung cancer cell growth by inducing fibronectin expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garanger E, Boturyn D, Dumy P. Tumor targeting with RGD peptide ligands—design of new molecular conjugates for imaging and therapy of cancers. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2007;7:552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruoslahti E. Integrins as signaling molecules and targets for tumor therapy. Kidney Int 1997;51:1413–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kunath K, Merdan T, Hegener O, Haberlein H, Kissel T. Integrin targeting using RGD-PEI conjugates for in vitro gene transfer. J Gene Med 2003;5:588–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]