Abstract

Airway infections or irritant exposures during early postnatal periods may contribute to the onset of childhood asthma. The purpose of this study was to examine critical periods of postnatal airway development during which ozone (O3) exposure leads to heightened neural responses. Rats were exposed to O3 (2 ppm) or filtered air for 1 hour on specific postnatal days (PDs) between PD1 and PD29, and killed 24 hours after exposure. In a second experiment, rats were exposed to O3 on PD2–PD6, inside a proposed critical period of development, or on PD19–PD23, outside the critical period. Both groups were re-exposed to O3 on PD28, and killed 24 hours later. Airways were removed, fixed, and prepared for substance P (SP) immunocytochemistry. SP nerve fiber density (NFD) in control extrapulmonary (EXP) epithelium/lamina propria (EPLP) increased threefold, from 1% to 3.3% from PD1–PD3 through PD13–PD15, and maintained through PD29. Upon O3 exposure, SP-NFD in EXP–smooth muscle (SM) and intrapulmonary (INT)-SM increased at least twofold at PD1–PD3 through PD13–PD15 in comparison to air exposure. No change was observed at PD21–PD22 or PD28–PD29. In critical period studies, SP-NFD in the INT-SM and EXP-SM of the PD2–PD6 O3 group re-exposed to O3 on PD28 was significantly higher than that of the group exposed at PD19–PD23 and re-exposed at PD28. These findings suggest that O3-mediated changes in sensory innervation of SM are more responsive during earlier postnatal development. Enhanced responsiveness of airway sensory nerves may be a contributing mechanism of increased susceptibility to environmental exposures observed in human infants and children.

Keywords: ozone, airways, substance P, development

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

There is mounting evidence that infections or irritant exposures occurring during infancy or childhood may contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma in children and adults. Despite the importance of early childhood exposures in asthma, little research characterizing neural responses caused by irritant exposure during the postnatal period has been studied. We examined the possible role of airway innervation and lung function during ozone exposure early in development.

Although human lung development begins during Gestational Week 3, the airways continue to differentiate and grow well into adolescence (1). Normal airways are innervated by both sensory and autonomic nerves (2), and, like the rest of the lung, growth and development of airway innervation continues during postnatal life (3). Airway innervation is established as the lung buds emerge from the foregut and continue development in association with the growing airways (4, 5). The nerves continue to grow in association with the airway during gestation, possibly under the influence of trophic factors, such as glial-derived growth factor produced from airway smooth muscle (5). In human airways, Hislop and colleagues (6) demonstrated that peptide-containing nerves were more abundant during ages 0–3 years as compared with adults, and that the tachykinin neurokinin-1 receptors increase during early postnatal life. Although sensory nerves expressing the tachykinin, substance P (SP), have been extensively characterized in adult rats, mice, and guinea pigs, a thorough quantitative analysis of SP innervation during early postnatal development is not available. However, this period is highly sensitive to the effects of inhaled irritants and allergens and linked to the subsequent development of asthma, both in children and adults.

Sensory innervation in the airways originates predominantly from neurons in the nodose and jugular ganglia (7–9), with minor contributions from the dorsal root ganglia (10, 11). In animal models, neurogenic inflammation in the airway is mediated by the release of tachykinins from the peripheral endings of sensory C fibers (12, 13) distributed throughout the airway walls (14). SP-containing sensory nerve endings are found near mucosal blood vessels, mucous glands, smooth muscle, and within the epithelium. SP released from sensory nerve fibers in the airway wall may contribute to the development of asthma through neurogenic inflammation, resulting in increased vascular permeability, chemotaxis of inflammatory cells, and smooth muscle hyperresponsiveness (15). In adult animal models, SP innervation of the airway wall is transiently increased after a wide range of airway irritants and exposures, including antigen challenge (10), Toluene diisocyanate exposure (16), viral infection (17), ozone (O3) exposure (18), hypoxia (19), cigarette smoke (20), sulfur dioxide (12), and asphalt fume exposure (21). These studies imply that irritant- or allergen-induced increases of SP in airway sensory nerves may contribute to altered airway function.

During early postnatal life, lung growth is particularly sensitive to the effects of inhaled irritants, such as O3 and allergens (22). Exposures during this period may also increase the incidence of airway disease later in life both in human subjects (23) and in animal models (24, 25). Airways responsiveness in children is more sensitive to inhaled irritants than in adults, and there is a high correlation between exposures that occur during prenatal and early postnatal periods and the subsequent development of asthma in children (26). Infants (under 3 yr) of smoking mothers have reduced lung function (27), and rat pups at gestational and postnatal periods exposed to side-stream tobacco smoke demonstrate reductions in lung function as adults (8 wk) even when smoke exposure was terminated at postnatal day (PD) 21 (24). High O3 levels in Mexico City have been positively correlated with infant mortality (28). These studies suggest that early-life exposures affect health later in life.

Thus, postnatal life is a period of unique sensitivity to inhaled pulmonary irritants that are initiated by interactions among immunological, environmental, and genetic factors. Early-life exposure may also have detrimental effects that persist into adulthood and result in permanently compromised lung function. It has been proposed that early life is a critical phase of susceptibility, during which irritant exposures may be a predisposing factor to the pathogenic mechanisms, leading to airway dysfunction in later life (29). In recent studies, infant monkeys exposed for 5 months to O3, house dust mite antigen, or the combination all had reduced lung innervation (30). Interestingly, after a 6-month recovery period, lung innervation was greater than in controls (25). These findings dramatically demonstrate both an effect of chronic injury on airway innervation and an extended effect that persists long after exposures have ceased.

Most currently available information on airway innervation is based on studies in airways from adult models. However, airway innervation during early postnatal life is more extensive than in adults (6), and, because innervation is still undergoing growth, may be uniquely sensitive to effects of inhaled irritants. Initially, the purpose of the current study was to examine responses of airway innervation to acute O3 exposures at specific postnatal ages in rat pups. These findings then led us to hypothesize that exposures during the first 2 postnatal weeks in rats may be more detrimental than exposures that occur after this period. Therefore, experiments were conducted to test for a “critical period of susceptibility.”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design

Part I—age-related changes in airway innervation and responses to O3.

Although the lung provides enough gas exchange at birth to sustain life, the lung continues to grow and mature during postnatal life. The hypothesis for this set of experiments is that airway sensory innervation continues to develop and increases throughout early postnatal life. We propose that O3 exposure during this active phase of neurodevelopment may alter normal patterns of airway innervation. Thus, we designed experiments to examine normal development of airway nerves at selected postnatal ages and test the acute response of innervation patterns to O3 exposures. Control and O3 exposures were divided into age groups comprising PDs 1–3, 4–6, 7–9, 10–12, 13–15, 21–22, and 28–29. Airway sensory innervation, defined as SP-like immunofluorescent nerves, was measured in control animals at each PD to establish developmental changes in normal airway innervation. The O3 groups were exposed to O3 at each PD and then killed 24 hours later to measure sensory innervation after O3 exposure.

Part II—evaluation of critical periods.

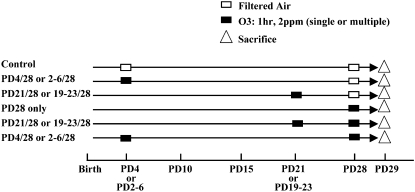

The second series of studies served to test the hypothesis that O3 exposure alters airway innervation and lung function after a subsequent re-exposure. Based on results in the initial studies described previously here, we reasoned that a critical period might exist before PD15, during which time airway innervation was rapidly growing and appeared to have stabilized. These experiments were divided into two approaches. The first protocol included an initial single O3 exposure at PD4 or PD21. The second protocol involved multiple O3 exposures occurring once per day over five consecutive days on PD2–PD6, within the critical period, or on PD19–PD23, beyond the putative critical period. Airway innervation and lung function in each exposure group was compared after a second exposure on PD28. As additional controls, we also included groups that received an initial exposure, but no second exposure on PD28, a group that was exposed only on PD28, and a PD28 group not exposed to O3 at any time point. The experimental protocols with the appropriate control groups for Part II only are shown in the model outline, with boxes indicating exposure time points (Figure 1). Both intrapulmonary and extrapulmonary airway smooth muscle were examined for these experiments, because they demonstrated a significant increase in SP nerve fiber density (NFD) after O3 exposure in comparison to control levels early in postnatal development (PD1–PD15). The extrapulmonary airway epithelium was not included for analysis in this study, due to the lack of response at most ages in the Part I acute exposure study. Lung function was measured by changes in pulmonary resistance and dynamic compliance (Cdyn) by using the first exposure protocol that included the initial single O3 exposure.

Figure 1.

Diagram outlining part II experimental protocol used in the evaluation of the critical period. PD, postnatal day; O3, ozone.

O3 exposure.

Technical details of our O3 exposure apparatus have been published previously (31). Fisher-344 rat pups were exposed for 1 hour to either O3 at a concentration of 2 ppm or filtered air at various postnatal ages in a stainless steel and glass exposure chamber. O3 was produced by passing hospital-grade air through a drying and high-efficiency particle filter, and then through an ultraviolet light source. The O3 concentration in the chamber was measured by chemiluminescence with a calibrated O3 analyzer (Model OA 350-2R; Forney, Carrollton, TX). In the air-exposed animals, procedures were identical to those described previously here, except that O3 was not delivered to the exposure chamber.

Lung fixation, immunocytochemistry, and NFD measurement.

All procedures for tissue preparation, immunocytochemistry, and analysis have been described in our previous publications (32). At 24 hours after the final exposure, the lungs were fixed by intratracheal inflation with picric acid–formaldehyde for 3 hours. Lung margins were trimmed to allow flowthrough and reduce intralumenal pressure, which flattens the epithelium. After 3 hours, the lungs were rinsed twice with a 0.1 M PBS containing 0.15% Triton X-100 (PBS-Tx [pH 7.8]) and remained in PBS-Tx overnight at 4°C. The next day, extraneous lung tissue was removed leaving only the airways, which were further dissected into extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary regions. The airways were placed on corks, covered with Tissue Tek OCT compound (Sakura, Torrance, CA), frozen in isopentane cooled with liquid nitrogen, and stored in airtight plastic bags at −80°C.

Cryostat sections (12-μm thick) of airway tissue were collected on gelatin-coated coverslips and dried briefly at room temperature. The sections were incubated with either rabbit anti-SP (1:200; Peninsula, Belmont, CA) or rabbit anti–protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 (1:50; Millipore, Billerica, MA) primary antiserum diluted in PBS-Tx plus 1% BSA (PBS-Tx-BSA [pH 7.8]) in a humid chamber at 37°C for 30 minutes. The sections were rinsed three times for 5 minutes each with PBS-Tx-BSA, covered with fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA) diluted 1:100 in PBS-Tx-BSA, incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes, rinsed three times for 5 minutes each in PBS-Tx-BSA, and mounted on glass slides in Fluoromount (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). The sections were observed with an Olympus AX70 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a fluorescein filter (excitation 495 nm and emission 520 nm). Controls consisted of testing the specificity of primary antiserum by absorption with 1 μg/ml of the specific antigen. Nonspecific background labeling was determined by omission of primary antiserum.

After immunocytochemical processing for SP or PGP 9.5, sections of airways were observed (40× magnification) on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope equipped with an argon laser (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Serial images of SP- or PGP 9.5–containing nerve fibers located in the epithelium/lamina propria or smooth muscle of the airways were collected from each coverslip. The serial images collected were saved to an internal database and then exported as black and white electronic TIF images. Using Optimus software (Bioscan, Edmonds, WA), the NFD was measured for each TIF image. The entire perimeter of the epithelium/lamina propria or smooth muscle was traced on each image of the airway regions. The threshold for each image was optimized so that only SP- or PGP 9.5–immunoreactive (IR) nerve fibers were visible. The SP- or PGP 9.5–NFD was calculated by dividing the SP- or PGP 9.5–IR nerve fiber area by the total area of epithelium/lamina propria or smooth muscle outlined. This represents the proportional cross-sectional area occupied by SP- or PGP 9.5–IR nerve fibers.

Measurement of lung function.

Lung function was determined by measuring changes of lung resistance (RL) and Cdyn after aerosolized methacholine (MCh) challenge with a modification of our previously described technique (33, 34). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with ketamine (25 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg). The trachea was cannulated just below the larynx via tracheotomy, and a four-way connector was attached to the tracheotomy tube. Two ports were connected to the inspiratory and expiratory tubes of a respirator (Harvard Model 683; Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA). The rats were ventilated at a constant rate of 200 breaths/min and a tidal volume of approximately 0.3 ml. Aerosolized MCh was administered for 30 seconds in increasing concentrations (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/ml). For 5 minutes before and after each MCh challenge, a computer analyzed the total RL and Cdyn on a breath-by-breath basis.

Data Analysis

NFD.

The results are expressed as means (±SE). The NFD was expressed as a percentage of the area of SP- or PGP 9.5–IR nerve fibers in the total area of either epithelium/lamina propria or smooth muscle. Statistical analysis was evaluated by using a one- or two-way (age and O3/air) ANOVA. When an effect was considered significant, a pair-wise comparison was made with a post hoc analysis. A value of P less than 0.05 was considered significant for each endpoint, and n represents the number of animals studied per experimental group.

Lung function.

The results are expressed as means (±SE). The RL and Cdyn elicited by MCh were expressed as a percentage of the baseline. Statistical analysis of RL and Cdyn was performed using a two-way, repeated-measures ANOVA. One factor was O3 exposure, and another factor was age treatment. When the main effect was considered significant at P less than or equal to 0.05, pair-wise comparisons were made with a post hoc analysis. A P value less than or equal 0.05 was considered significant, and n represents the number of animals studied.

RESULTS

Part I—Age-Related Changes in Airway Innervation and Responses to O3

Percentage of SP-NFD in control airway regions from PD1–PD29.

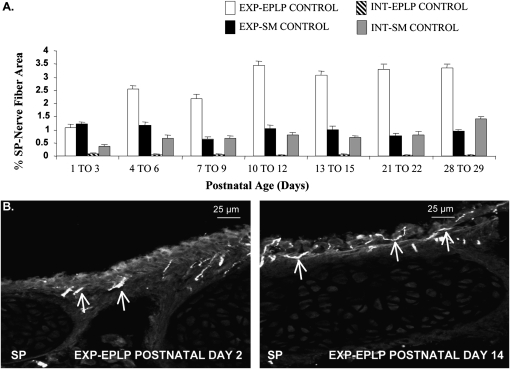

The percentage of SP-IR nerve fibers in the extrapulmonary epithelium/lamina propria increased threefold from approximately 1 to 3.3% from PD1–PD3 through PD13–PD15, and was then maintained through PD29 (Figures 2A and 2B). SP-NFD in the extrapulmonary smooth muscle, intrapulmonary epithelium/lamina propria, and intrapulmonary smooth muscle was mostly constant throughout the postnatal ages, and did not change between any postnatal groups. In the remaining studies, the intrapulmonary epithelium/lamina propria SP-NFD was no longer measured, due to the small epithelial area resulting in minimal numbers of nerve fibers.

Figure 2.

Substance P (SP) nerve fiber density (NFD) in control rat airway regions from PD1 to PD29. SP nerve fibers were measured to provide evidence that airway sensory innervation continues to develop and increase throughout early postnatal life. (A) The percent area of SP-immunoreactive (IR) nerve fibers were measured in extrapulmonary (EXP) epithelium/lamina propria (EPLP), EXP smooth muscle (SM), intrapulmonary (INT)-EPLP, and INT-SM. (B) Photomicrographs of EXP-EPLP showing increased localization of SP-IR nerve fibers on PD14 in comparison to PD2 (arrows demonstrate SP-IR nerve fibers). Values are means (±SE) (n = 6 for all groups).

Percentage of SP-NFD in airway regions after O3 exposure from PD1 to PD29.

SP-NFD responses 24 hours after O3 exposure (2 ppm, 1 h) were examined throughout the first month of postnatal life to identify a possible critical period of susceptibility to O3 exposure. In the extrapulmonary epithelium/lamina propria, O3 exposure caused a significant increase in SP-NFD at PD13–PD15 in comparison to control, from 3.07 (±0.15)% to 4.72 (±0.17)%, respectively (Figure 3A). The SP-NFD in animals exposed at all other postnatal ages did not differ from control levels, suggesting that the postnatal period between PD13 and PD15 may represent a “critical window” of susceptibility.

Figure 3.

The effect of O3 on SP-NFD in rat airway regions during PD1–PD29. SP-NFD responses to O3 exposure were examined throughout the first month of postnatal life to identify a possible critical period of susceptibility to O3 exposure. The percent area of SP-IR nerve fibers were measured in (A) EXP-EPLP, (B) INT-SM, and (C) EXP-SM in control and O3-exposed rat pups at PD1–PD29 (n = 6 for all groups; *P < 0.05). (D) Photomicrographs of EXP-SM demonstrate the significant increase in SP-IR nerve fibers (arrows) observed in O3-exposed rats compared with control animals at PD4.

In the intrapulmonary and extrapulmonary smooth muscle, O3 exposure caused a significant increase in SP-NFD at PD1–PD3, PD4–PD6, and PD13–PD15 in comparison with control values. In the intrapulmonary smooth muscle (Figure 3B), the SP-NFD values increased from 0.37 (±0.07)% in controls to 1.38 (±0.09)% after O3 exposure at PD1–PD3, from 0.69 (±0.10)% to 1.37 (±0.10)% at PD4–PD6, and from 0.70 (±0.08)% to 1.32 (±0.08)% at PD13–PD15. The SP-NFD in the intrapulmonary smooth muscle did not significantly increase at PD21–PD22 or PD28–PD29 after O3 exposure in comparison to control values. In the smooth muscle of the extrapulmonary airways, the SP-NFD followed a pattern similar to the intrapulmonary smooth muscle after O3 exposure (Figures 3C and 3D). O3 exposure caused significant increases in SP-NFD at PD1–PD3, PD4–PD6, and PD13–PD15 compared with respective controls. The SP-NFD values increased from 1.22 (±0.08)% to 2.23 (±0.10)% at PD1–PD3, 1.16 (±0.14)% to 2.11 (±0.08)% at PD4–PD6, and 1.03 (±0.11)% to 1.75 (±0.14)% at PD13–PD15. No change in SP-NFD was observed in the extrapulmonary smooth muscle at PD21–PD22 or PD28–PD29 between control animals and O3-exposed animals.

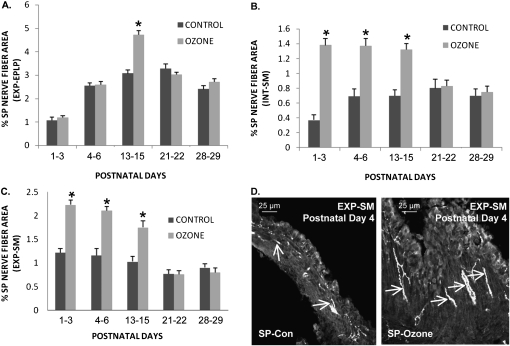

The effect of O3 on SP- and PGP-NFD in extrapulmonary airway smooth muscle at age PD-3.

SP- and PGP-NFD responses to O3 exposure (2 ppm, 1 h) were examined in the extrapulmonary smooth muscle to determine if the increases in SP-NFD were due to an increase in the SP production of existing but unlabeled fibers or to new or branching nerve fibers (Figures 4A and 4B). The age of PD3 was selected because this time point demonstrated the highest increase in SP-NFD in the smooth muscles of the extrapulmonary airways after O3 exposure (see previous experiments). The density of PGP 9.5 nerve fibers in the extrapulmonary smooth muscle did not significantly change 24 hours after O3 exposure (2.40 ± 0.10%) in comparison to control levels (2.45 ± 0.13%). However, a significant increase was observed in the density of SP nerve fibers in the extrapulmonary smooth muscle after O3 exposure from 1.20 (±0.08)% in controls to 2.20 (±0.10)% in exposed animals, which brought the level of SP-NFD to the same level as PGP. These findings suggest that O3 increases SP content in existing nerves that are either not producing SP or are producing SP below a detectable level in controls. However, due to inherent limitations in discriminating between individual axons within bundles of nerve fibers, the possibility of axon branching or outgrowth cannot be entirely eliminated (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

The effect of O3 on SP and protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 nerve fiber area in rat EXP-SM on PD3. SP- and PGP-NFD responses were examined in the EXP-SM to determine if previous increases in SP-NFD density were due to an increase in the SP production or in axonal branching of nerve fibers (shown by PGP 9.5 staining). (A) The percentage of SP and PGP 9.5 immunoreactivity was measured in the EXP-SM comparing O3-exposed to control animals at PD3 (values are means [±SE]; n = 6 for all groups; *P < 0.05). (B) The top two photomicrographs of the EXP-SMs show no change in PGP 9.5–IR nerve fibers between control and O3-exposed animals on PD3. The bottom two micrographs of the EXP-SMs demonstrate an increased localization of SP-IR nerve fibers in O3-treated animals in comparison with control at the PD3.

Part II—Evaluation of Critical Periods

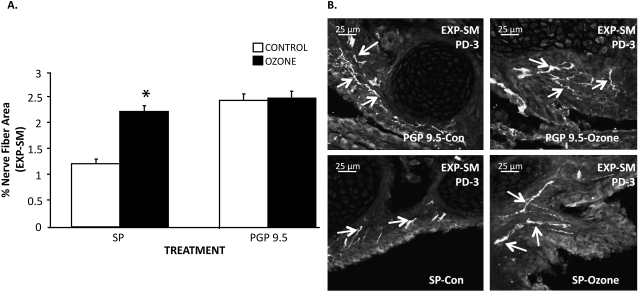

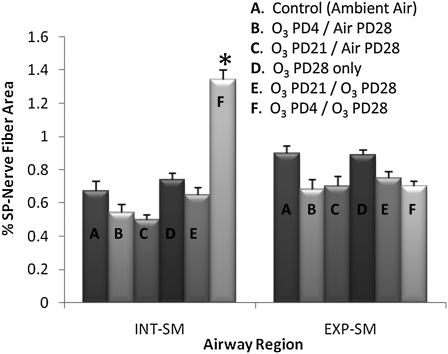

The effect of single O3 exposures on SP-NFD in airway smooth muscle during a critical period.

In the single O3 exposure studies, changes in SP-NFD were observed only in the smooth muscle of the intrapulmonary airways (Figure 5). As predicted by the model, there was a twofold, significant increase only in the group exposed on both PD4 and PD28 (1.34 ± 0.03%) in comparison with the control ambient air group (0.67 ± 0.08%) and the PD28 only O3 exposure group (0.74 ± 0.05%). In addition, the O3 exposure on PD21 did not cause a significant increase in the percentage of SP-NFD after re-exposure on PD28 (0.65 ± 0.08%) in comparison to the control ambient air group (0.67 ± 0.08%) and the PD21-O3/PD28 air exposure group (0.48 ± 0.05%). No changes were demonstrated in SP innervation among any groups in the extrapulmonary smooth muscle.

Figure 5.

The effect of single O3 exposures on SP-NFD in airway smooth muscle during a critical period. The percent area of SP-IR nerve fibers was measured in both INT- and EXP-SM. SP nerve fibers were measured to determine if O3 exposure (2 ppm, 1 h) during early PD4 would result in prolonged changes of airway innervation upon a second O3 exposure (PD28) in comparison to controls and exposures outside the critical period (PD21). Values are means (±SE) (n = 6 for each group; *P < 0.05).

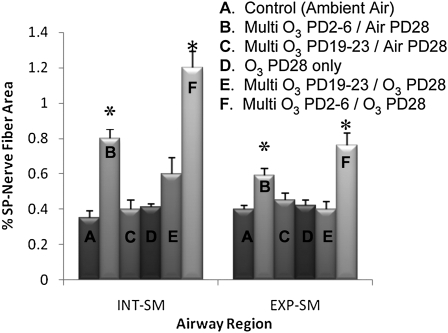

The effect of multiple O3 exposures on SP-NFD in airway smooth muscle during a critical period.

In the initial multiple O3 exposure studies, significant differences in SP innervation were observed in both the extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary smooth muscle (Figure 6). In both extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary smooth muscle, SP-NFD in the two groups exposed to O3 on PD2–PD6 and PD28 was significantly elevated over all the other groups. The SP-NFD in the PD2–PD6 O3 group that was re-exposed to O3 on PD28 (1.13 ± 0.07% for intrapulmonary and 0.71 ± 0.09% for extrapulmonary) was significantly higher than groups that were not re-exposed (0.81 ± 0.09% for intrapulmonary and 0.59 ± 0.06% for extrapulmonary). The SP-NFD of those O3 exposed on PD19–PD21 and re-exposed on PD28 (0.52 ± 0.7% for intrapulmonary and 0.37 ± 0.03% for extrapulmonary) were not significantly different from the PD19–PD21 O3-exposed animals without O3 re-exposure (0.39 ± 0.06% for intrapulmonary and 0.48 ± 0.05% for extrapulmonary) and from the unexposed controls (0.32 ± 0.03% and 0.39 ± 0.01%). The important comparison is between the O3-exposed PD2–PD6/PD28 group and the O3-exposed PD19–PD23/PD28 group, which showed that SP-NFD in the early exposure group was significantly greater than in the animals in the later exposure group in both extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary smooth muscle.

Figure 6.

The effect of multiple O3 exposures on SP-NFD in airway smooth muscle during a critical period of development. The percent area of SP-IR nerve fibers was measured in the INT- and EXP-SM. The multiple O3 exposure (2 ppm, 1 h) consisted of 5 consecutive days of exposure. SP nerve fibers were measured to determine if multiple O3 exposure during early postnatal life (PD2–6) would increase sensory airway innervation upon a second O3 exposure (PD28) in comparison with controls and exposures outside the critical period (PD19–PD23). Values are means (±SE) (n = 6 for all groups; *P < 0.05).

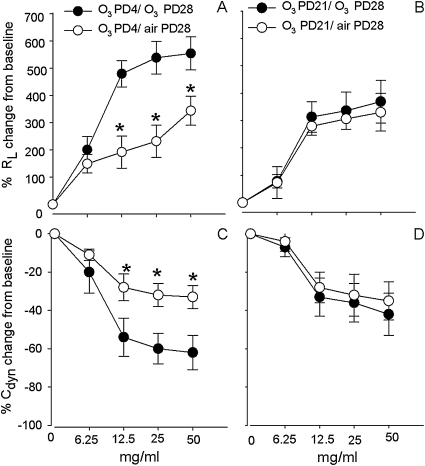

The effect of single O3 exposures on changes in lung function during a critical period.

The MCh dose–response curves for RL were significantly elevated, and, for Cdyn, significantly decreased in the group exposed to O3 both on PD4 and PD28 in comparison with the group exposed to O3 on PD4 and then air on PD28 (Figures 7A and 7C). For example, MCh at the dose of 25 mg/ml increased RL by 266% in the group exposed to O3 on PD4 and air on PD28, and by 556% in the group exposed to O3 on both PD4 and PD28 (Figure 7A). However, there was no significant difference in the in RL or Cdyn to MCh between the group exposed to O3 on both PD21 and PD28 and the group exposed to O3 on PD21 and then air on PD28 (Figures 7B and 7D). The same MCh dose of 25 mg/ml produced a 284% increase in the group exposed to O3 on PD21 and air on PD28, and only a 325% increase in RL in the group exposed to O3 on both PD21 and PD28 (Figure 7B). There was no significant difference in the RL and Cdyn to MCh challenge between air exposure on PD28 and O3 exposure on PD28 (data not shown). The MCh dose of 25 mg/ml increased the RL by 299% (n = 5) in the air exposure PD28 group, and by 329% (n = 5) in the O3 exposure PD28 group. As predicted by the model, there was a significant increase in RL to MCh at 25 mg/ml in the group exposed on both PD4 and PD28 in comparison with the group exposed to O3 on both PD21 and PD28 and the group exposed to O3 only on PD28. There were no significant differences in the baseline RL and Cdyn values among the different experimental groups before MCh challenge.

Figure 7.

The effect of single O3 exposures on lung function during a critical period. The lung function was measured by methacholine dose responses of lung resistance (RL) and dynamic compliance (Cdyn). Lung function was measured to determine if O3 exposure (2 ppm, 1 h) during early PD4 would result in prolonged changes of RL and Cdyn upon a second O3 exposure (PD28) in comparison with controls and exposures outside the critical period (PD21). Values are means (±SE) (n = 3–5 for each group; *P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Although the lung provides enough gas exchange at birth to sustain life, growth and maturation continues during postnatal life and into early adulthood (1). During the prenatal period, growth of epithelial and connective tissues, blood vessels, and nerves is highly coordinated to maintain the normal structure and functional relationships of the respiratory system. However, critical and key changes also occur during the postnatal and adolescent periods of lung development. For example, in the human lung, the adult compliment of alveoli is not reached until about the age of 18 years, and the number of airway generations nearly doubles from birth. Many studies demonstrate continued changes in airway sensitivity and responsiveness throughout childhood (35–37). However, the contributions of airway innervation to altered airway responses in early life are not well defined. The goal of the current investigation was to characterize neural responses to O3 exposures in early life. Therefore, our initial studies examined the normal developmental changes that occur in SP airway innervation throughout the first month of postnatal life. Changes in SP-containing nerves were measured because of their well established role in regulating airway responses to irritants such as O3 (38, 39). The results show that SP-containing nerve fibers in the extrapulmonary epithelium and lamina propria increased threefold from PD1 through PD15, and were maintained through PD29 (Figure 2A). Sensory innervation in the extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary smooth muscle was generally constant throughout all postnatal ages, and did not change between postnatal groups. Previous studies examining age-related changes in sensory innervation and neurotransmitter expression in young animals and children are very limited. One study shows an increase innervation of SP-IR axons in the epithelium in comparison to the smooth muscle in the rat extrapulmonary airway, which parallels our results after PD3; however, this study lacked a timeline, and only examined 3-month-old rats (40). Another study on airways of children demonstrated a lack of change in the density of peptidergic nerves in young children aged 0–3.5 years (correlates to PD1–PD20 in rat age), which seems to follow trends observed in the extrapulmonary and intrapulmonary smooth muscle of our studies (6).

Acute O3 exposure caused increased SP-NFD in the intrapulmonary and extrapulmonary smooth muscle through PD15 (Figures 3B and 3C). These responses did not occur in rats exposed at the later postnatal ages, PD21–22 and PD28–29. These findings indicate that the early postnatal period (i.e., PD1–PD15) is a critical phase of neural development sensitive to the effects of O3. Irritant exposure during this developmental phase may be a predisposing factor to the pathogenic mechanisms leading to neurogenic inflammation (41). In ferret, we have shown that increased SP innervation after O3 exposure is associated with increased airway smooth muscle responsiveness (31, 42, 43). In rat, SP contracts airway smooth muscle and increases vascular permeability (13, 40). Therefore, the increase in airway SP innervation found in the current investigation is consistent with the role of SP in mediating airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation

An important comparison in our study was the relative change in SP and PGP nerves after O3 exposure (i.e., although O3 induced an increase in SP nerves, the total nerve density, measured by PGP, did not change) (Figure 4A). It is likely that some nerves in unexposed animals do not contain sufficient SP to reach detectability, and that O3 induces enhanced SP synthesis, increasing content to detectable levels. This could occur if O3 exposure induced the release of growth or neurotrophic factors within the airway wall. Early studies on developmental neurobiology demonstrate that target derived factors are critical to the normal development of such diverse structures as the limb buds (44) and sweat glands (45). In particular, the neurotrophin, nerve growth factor (NGF), is critical for normal sensory and sympathetic innervation of peripheral targets. NGF promotes survival and axonal branching, stimulates SP synthesis in sensory neurons, and mediates inflammatory responses in the airways (46). This is relevant to the current study, because SP innervation in the rat airway originates predominantly from the sensory (nodose and jugular) ganglia of the vagus nerve (7, 9). Thus, a possible explanation for the enhanced airway innervation after early O3 exposure is that neurotrophic factors, possibly NGF, released during O3 exposure promote SP synthesis, increasing SP content in nerve fibers and terminals in the airways. Neurotrophic factors may also stimulate increased axonal branching, leading to increased innervation density. It is well established that sensory neurons are sensitive to neurotrophins during prenatal and early postnatal life in rats and mice (47–49). The findings in the current study are suggestive of a response in which SP levels are increased in nerve fibers that were previously undetectable, and do not support the possibility of new nerve fiber growth. However, due to the limitations of fluorescence microscopy to discriminate between individual fibers, especially in small bundles of axons, the possibility of axon sprouting or new nerve fiber ingrowth should not be excluded at this time, especially because a known action of neurotrophins includes the induction of axonal outgrowth.

Interestingly, a previous study demonstrated that 4% of the PGP-IR axons in the airway smooth muscle of 3-month-old adult rats were SP positive (38) compared with nearly 50% in the smooth muscle of airways from the control, PD3 rats in our study (Figure 4A). Although recognizing that differences in laboratory procedures may create some inherent variation, this comparison suggests that a substantial loss of SP from airway nerve fibers occurs during maturation between the early postnatal and the adult in rats. Whether this attenuation is due to a reduction in nerve fibers or to reduced SP production in airway neurons of the adult remains an open question. The observation that all nerve fibers, judged by PGP 9.5 labeling, are SP positive after O3 exposure also requires additional comment. Many axons in smooth muscle are autonomic nerves, and probably cholinergic in nature. The observation in our current investigation, that SP expression is present in virtually all axons after O3 exposure, is consistent with our previous report in ferret trachea showing that O3 exposure induced SP expression not only in sensory nerve, but also in the putative cholinergic neurons of airway ganglia (31). It was shown in a subsequent study that the enhanced SP expression in the airway neurons of ferret trachea is mediated through the actions of NGF (50).

The second set of experiments in the current study was conducted to test the hypothesis that, compared with acute exposures occurring after the critical period, O3 exposure during the proposed critical period of susceptibility (PD1–PD15) enhances airway innervation after a second exposure occurring later. The findings showed that a single O3 exposure on PD4 or multiple daily exposures during PD2–PD6 both caused increased SP innervation in the intrapulmonary airway smooth muscle on PD29, 24 hours after a second O3 exposure on PD28 (Figures 5 and 6). The multiday exposure also increased smooth muscle innervation in the extrapulmonary airways after re-exposure. Conversely, initial exposures on PD21 (single) or PD19–PD23 (multiple) had no effect on airway innervation after re-exposure. Our findings, that early exposures enhance airway innervation after re-exposure, suggest that the PD2–PD6 rat pups are more sensitive to the effects of O3 than the older pups. The fact that the enhanced innervation only occurred with the early exposure (PD4, PD2–PD6) suggests a unique susceptibility to O3 during this period. An interesting finding of our study is that the increased innervation was observed only after re-exposure on PD28 and only after initial exposure on PD4 or PD2–PD6. Additional findings in this study demonstrated that changes in RL and Cdyn paralleled the altered SP airway innervation found in the intrapulmonary smooth muscle. These physiological changes after O3 exposure during a critical period suggest a link between altered airway innervation and the changes observed in pulmonary function. Other studies have demonstrated that children exposed to environmental tobacco smoke in utero or early in life are more sensitive to allergens and irritants later in life (23, 51). These reports and our findings support the idea that exposure during early postnatal life may permanently alter airway functional characteristics that are only revealed when challenged by airway irritants, such as smoke, O3 or other pollutants, or by allergens.

The finding that only early exposures (PD2–PD6) produced this outcome, and that this was not produced when similar exposures occurred later (PD19–23), strongly supports a conclusion that exposures during early life have greater potential for producing permanent or long-term decrements in lung function. It is tempting to speculate that, because the lung is still rapidly growing during this early period, the exposures influence the developmental trajectory of smooth muscle responsiveness, inflammatory mechanisms, and, as seen in our present study, the extent and plasticity of airway innervation.

The results in our current study suggest that SP-containing airway neurons have the capacity to increase rapidly the levels of SP present in nerve terminals innervating airway smooth muscle. It is likely that increased levels of SP in nerve terminals lead to increased SP release when the nerve is activated. SP production in airway neurons is increased after O3 or allergen exposure (10, 52). These finding show that SP release is subject to modulation and results in increased airway responsiveness. Our findings suggest that early life exposures to O3 may predispose to enhanced SP production and release. Based on approximation models comparing rat and human pre- and postnatal periods (29), the period of PD2–PD6 corresponds most closely to the period of infancy through preschool age, implicating this age group as a susceptible population for environmental tobacco smoke, air pollution, and extreme weather conditions. Although our findings did not reveal susceptibility when exposures occurred at older ages, these data should not be interpreted to indicate that O3 exposures in older rats (or children) would be without detrimental effects.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1HL80566.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0191OC on January 29, 2010

Author Disclosure: D.D.H. received a sponsored grant from National Institutes of Health (NIH) for more than $100,001; R.D.D. received a sponsored grant from NIH for more than $100,001; Z.W. received a sponsored grant from NIH for more than $100,001, and has a spouse/life partner who received a sponsored grant from NIH for $10,001–$50,000.

References

- 1.Harding R, Pinkerton KE, Plopper CG, editors. The lung: development, aging, and the environment. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004.

- 2.Kaliner MA, Barnes PJ. The airways: neural control in health and disease. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1988.

- 3.Weichselbaum M, Sparrow MP. A confocal microscopic study of the formation of ganglia in the airways of fetal pig lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999;21:607–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sparrow MP, Weichselbaum M, Tollet J, McFawn PK, Fisher JT. Development of the airway innervation. In: Harding R, Pinkerton KE, Plopper CG, editors. The lung: development, aging and the environment. London: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 33–53.

- 5.Tollet J, Everett AW, Sparrow MP. Development of neural tissue and airway smooth muscle in fetal mouse lung explants: a role for glial-derived neurotrophic factor in lung innervation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hislop AA, Wharton J, Allen KM, Polak JM, Haworth SG. Immunohistochemical localization of peptide-containing nerves in human airways: age-related changes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1990;3:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter DD, Undem BJ. Identification and substance P content of vagal afferent neurons innervating the epithelium of the guinea pig trachea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1943–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalia M, Mesulam M-M. Brain stem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus complex in the cat: II. laryngeal, tracheobronchial, pulmonary, cardiac, and gastrointestinal branches. J Comp Neurol 1980;193:467–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey RD, Altemus JB, Zervos I, Hoffpauir J. Origin and colocalization of CGRP- and SP-reactive nerves in cat airway epithelium. J Appl Physiol 1990;68:770–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer A, McGregor GP, Saria A, Philippin B, Kummer W. Induction of tachykinin gene and peptide expression in guinea pig nodose primary afferent neurons by allergic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest 1996;98:2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kummer K, Fischer A, Mundel P, Mayer B, Hoba B, Philippin B, Preissler U. Nitric oxide synthase in VIP-containing vasodilator nerve fibers in the guinea pig. Neuroreport 1992;3:653–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundberg JM, Saria A. Capsaicin-induced desensitization of airway mucosa to cigarette smoke, mechanical and chemical irritants. Nature 1983;302:251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundberg JM, Saria A, Brodin E, Rosell S, Folkers KA, Substance P. Antagonist inhibits vagally induced increase in vascular permeability and bronchial smooth muscle contraction in the guinea pig. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1983;80:1120–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundberg JM, Hokfelt T, Martling C-R, Saria A, Cuello C. Substance P–immunoreactive sensory nerves in the lower respiratory tract of various mammals including man. Cell Tissue Res 1984;235:251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maggi CA, Giachetti A, Dey RD, Said SI. Neuropeptides as regulators of airway function: vasoactive intestinal peptide and the tachykinins. Physiol Rev 1995;75:277–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter DD, Satterfield BE, Huang J, Fedan JS, Dey RD. Toluene diisocyanate enhances substance P in sensory neurons innervating the nasal mucosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr MJ, Hunter DD, Jacoby DB, Undem BJ. Expression of tachykinins in nonnociceptive vagal afferent neurons during respiratory viral infection in guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:1071–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham RM, Friedman M, Hoyle GW. Sensory nerves promote ozone-induced lung inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida T, Matsuda H, Hayashida Y, Gono Y, Nagahara T, Kawakami T, Takenaka T, Tsukuda M, Kusakabe T. Changes in the distribution of the substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactive nerve fibers in the laryngeal mucosa of chronically hypoxic rats. Histol Histopathol 1999;14:735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundberg JM, Martling C-R, Saria A, Folkers K, Rosell S. Cigarette smoke–induced airway oedema due to activation of capsaicin-sensitive vagal afferents and substance P release. Neuroscience 1983;10:1361–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sikora ER, Stone S, Tomblyn S, Castranova V, Dey RD. Asphalt exposure enhances neuropeptides levels in sensory neurons projecting to the nasal epithelium. J Toxicol Environ Health 2003;66:1015–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinkerton KE, Joad JP. Influence of air pollution on respiratory health during perinatal development. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2006;33:269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skorge TD, Eagan TM, Eide GE, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS. The adult incidence of asthma and respiratory symptoms by passive smoking in uterus or in childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joad JP, Bric JM, Peake JL, Pinkerton KE. Perinatal exposure to aged and diluted sidestream cigarette smoke produces airway hyperresponsiveness in older rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1999;155:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kajekar R, Pieczarka EM, Smiley-Jewell SM, Schelegle ES, Fanucchi MV, Plopper CG. Early postnatal exposure to allergen and ozone leads to hyperinnervation of the pulmonary epithelium. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2007;155:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arshad SH, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, Matthews S. Early life risk factors for current wheeze, asthma, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness at 10 years of age. Chest 2005;127:502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones M, Castile R, Davis S, Kisling J, Filbrun D, Flucke R, Goldstein A, Emsley C, Ambrosius W, Tepper RS. Forced expiratory flows and volumes in infants: normative data and lung growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loomis D, Castillejor M, Gold DR, McDonnell W, Borja-Aburto VH. Air pollution and infant mortality in mexico city. Epidemiology 1999;10:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinkerton KE, Joad JP. The mammalian respirtory system and critical window of exposure for children's health. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:457–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson SD, Schelegle ES, Walby WF, Gershwin LJ, Fanuccihi MV, Evans MJ, Joad JP, Tarkington BK, Hyde DM, Plopper CG. Postnatal remodeling of the neural components of the epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit in the proximal airways of infant rhesus monkeys exposed to ozone and allergen. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2004;194:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z-X, Satterfield BE, Dey RD. Substance P release from intrinsic airway neurons contributes to ozone-enhanced airway hyperresponsiveness in ferret trachea. J Appl Physiol 2003;95:742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter DD, Satterfield BE, Dey RD. Effects of toluene diisocyanate exposure on substance P (SP) immunoreactivity in trigeminal sensory neurons innervating the nasal epithelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:A484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Z-X, Zhou DH, Chen G, Lee LY. Airway hyperresponsiveness to cigarette smoke in ovalbumin-sensitized guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Z-X, Hunter DD, Kish VL, Benders KM, Batchelor TP, Dey RD. Prenatal and early, but not late, postnatal exposure of mice to sidestream tobacco smoke increases airway hyperresponsiveness later in life. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:1434–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aberg G, Alder G. The effect of age on adrenoceptor activity in tracheal smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 1973;47:181–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clerici C, Harf A, Gaultier C, Roudot F. Cholinergic component of histamine-induced bronchoconstriction in newborn guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol 1989;66:2145–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duncan PG, Douglas JS. Influences of gender and maturation on responses of guinea-pig airway tissues to LTD4. Eur J Pharmacol 1985;112:423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jimba M, Skornik WA, Killingsworth CR, Long NC, Brain JD, Shore SA. Role of C fibers in physiological responses to ozone in rats. J Appl Physiol 1995;78:1757–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu ZX, Maize DF Jr, Satterfield BE, Frazer DG, Fedan JS, Dey RD. Role of intrinsic airway neurons in ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in ferret trachea. J Appl Physiol 2001;91:371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baluk P, Nadel JA, McDonald DM. Substance P–immunoreactive sensory axons in the rat respiratory tract: a quantitative study of their distribution and role in neurogenic inflammation. J Comp Neurol 1992;319:586–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pino MV, Levin JR, Stovall MY, Hyde DM. Pulmonary inflammation and epithelial injury in response to acute ozone exposure in the rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1992;112:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Z-X, Satterfield BE, Fedan JS, Dey RD. Interleukin-1beta–induced airway hyperresponsiveness enhances substance P in intrinsic neurons of ferret airway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;283:L909–L917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu ZX, Barker JS, Batchelor TP, Dey RD. Interleukin (IL)-1 regulates ozone-enhanced tracheal smooth muscle responsiveness by increasing substance P (SP) production in intrinsic airway neurons of ferret. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2008;164:300–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamburger V, Levi-Montalcini R. Proliferation, differentiation and degeneration in the spinal ganglia of the chick embryo under normal and experimental conditions. J Exp Zool 1949;111:457–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landis SC. Target regulation of neurotransmitter phenotype. Trends Neurosci 1990;13:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freund-Michel V, Frossard N. The nerve growth factor and its receptors in airway inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2008;117:52–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buj-Bello A, Pinon LG, Davies AM. The survival of NGF-dependent but not BDNF-dependent cranial sensory neurons is promoted by several different neurotrophins early in their development. Development 1994;120:1573–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davies AM. Regulation of neuronal survival and death by extracellular signals during development. EMBO J 2003;22:2537–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forgie A, Kuehnel F, Wyatt S, Davies AM. In vivo survival requirement of a subset of nodose ganglion neurons for nerve growth factor. Eur J Neurosci 2000;12:670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu ZX, Dey RD. Nerve growth factor-enhanced airway responsiveness involves substance P in ferret intrinsic airway neurons. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L111–L118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez FD, Stern DA, Wright AL, Taussig LM, Halonen M. Differential immune responses to acute lower respiratory illness in early life and subsequent development of persistent wheezing and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;102:915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho CY, Lee LY. Ozone enhances excitabilities of pulmonary c fibers to chemical and mechanical stimuli in anesthetized rats. J Appl Physiol 1998;85:1509–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]