Abstract

Small heat shock proteins HSP27 and HSP20 have been implicated in regulation of contraction and relaxation in smooth muscle. Activation of PKC-α promotes contraction by phosphorylation of HSP27 whereas activation of PKA promotes relaxation by phosphorylation of HSP20 in colonic smooth muscle cells (CSMC). We propose that the balance between the phosphorylation states of HSP27 and HSP20 represents a molecular signaling switch for contraction and relaxation. This molecular signaling switch acts downstream on a molecular mechanical switch [tropomyosin (TM)] regulating thin-filament dynamics. We have examined the role of phosphorylation state(s) of HSP20 on HSP27-mediated thin-filament regulation in CSMC. CSMC were transfected with different HSP20 phosphomutants. These transfections had no effect on the integrity of actin cytoskeleton. Cells transfected with 16D-HSP20 (phosphomimic) exhibited inhibition of acetylcholine (ACh)-induced contraction whereas cells transfected with 16A-HSP20 (nonphosphorylatable) had no effect on ACh-induced contraction. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 cDNA showed significant decreases in 1) phosphorylation of HSP27 (ser78); 2) phosphorylation of PKC-α (ser657); 3) phosphorylation of TM and CaD (ser789); 4) ACh-induced phosphorylation of myosin light chain; 5) ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27; and 6) ACh-induced dissociation of TM from caldesmon (CaD). We thus propose the crucial physiological relevance of molecular signaling switch (phosphorylation state of HSP27 and HSP20), which dictates 1) the phosphorylation states of TM and CaD and 2) their dissociations from each other.

Keywords: relaxation, heat shock protein, molecular signaling switch, molecular mechanical switch, smooth muscle contraction

agonist-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations have been implicated in the initiation of smooth muscle contraction (42, 46, 54, 61). Although phosphorylation of regulatory myosin light chains (MLC20) by activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) is the key mechanism for initiation of smooth muscle contraction, inactivation of myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) is the key mechanism for maintenance of smooth muscle contraction (25). However, maintenance of force upon decrease in intracellular calcium concomitant with decrease in phosphorylation of MLC20 is associated with thin-filament regulation (18, 36, 38, 64). Thin-filament regulation explains the maintenance of tone at low MLC20 phosphorylation. Thin-filament regulation modulates the interaction of actin molecules of the thin filament with myosin heads of the thick filament for contraction to occur (10, 20, 53, 65).

Relaxation of smooth muscle occurs either as a result of removal of the contractile stimulus or by the direct action of a substance that stimulates inhibition of the contractile mechanism (11, 19, 30, 43). Regardless, the process of relaxation requires a decreased intracellular Ca2+ concentration and increased MLCP activity. Most previous investigations have suggested that cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation occurs through inhibition or reversal of the Ca2+/MLCK/MLC20 pathway (60). The modulations at thin-filament level during colonic smooth muscle relaxation have not been studied. Here we address the thin-filament-mediated regulation of relaxation. A fundamental paradox in smooth muscle physiology is that increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations and MLC20 phosphorylation are transient in the continued presence of a contractile agonist even though force is maintained. Dissociation between the state of MLC20 phosphorylation and force production suggests that mechanisms other than thick-filament (myosin and MLC20; MLCK and MLCP) regulation are operative in contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle.

Another regulatory mechanism postulated in smooth muscle contraction is thin-filament regulation of actomyosin interaction. Phosphorylation of small heat shock protein HSP27 modulates the interactions of thin-filament binding proteins tropomyosin (TM) and caldesmon (CaD) with HSP27, actin, and each other (5). Thus phosphorylation of HSP27 plays a fundamental role in thin-filament-mediated regulation of smooth muscle contraction. A recently identified regulator of relaxation is small heat shock protein HSP20, a substrate protein of both PKG and PKA (4, 21, 33, 49, 66). HSP20 is highly and constitutively expressed in muscle tissues. HSP20 has been shown to play a role in modulating actin filament dynamics. Increases in the phosphorylation of HSP20 are associated with cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and inhibition of agonist-induced contraction of smooth muscle (34). HSP20 has been suggested to mediate relaxation via a thin-filament (actin) regulatory mechanism (66). Phosphorylation of HSP20 is inhibited by phosphorylation of HSP27 in vitro (16). Earlier studies from our laboratory have shown that relaxant peptide VIP induced modulation in thin-filament regulation by inhibiting the activation of PKC-α (58) concomitant with phosphorylation of HSP20 (21). Here studies were focused on the potential role of HSP20 phosphorylation in thin-filament regulation of relaxation. Investigations were done to examine the effect of phosphorylated HSP20 on the interaction of HSP27 with thin-filament regulatory proteins. Colonic smooth muscle cells (CSMC) were transfected with 16D-HSP20 (phosphomimic HSP20) cDNA or 16A-HSP20 (nonphosphorylatable HSP20) cDNA. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 cDNA exhibited decreased ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27, decreased dissociation of TM from CaD and inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 (ser78), TM, CaD (ser789), and PKC-α (ser657). CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 cDNA appeared similar to the nontransfected CSMC exhibiting increased ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27 and increased dissociation of TM from CaD concomitant with a significant and sustained increase in ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 (ser78), TM, CaD (ser789), and PKC-α (ser657). Thus we propose that phosphorylation of HSP20 inhibits PKC-α-mediated HSP27 phosphorylation, leading to alterations in phosphorylation and association of thin-filament regulatory proteins, resulting in relaxation (inhibition of contraction). In addition, ACh-induced phosphorylation of MLC20 was inhibited in CSMC transfected with phosphomutant 16D-HSP20 cDNA, suggesting a role of phosphorylated HSP20 in phosphorylation of MLC20. Woodrum et al. (66) have suggested that phosphorylation of HSP20 represents a point in which the cyclic nucleotide signaling pathways converge to prevent contraction or cause relaxation. PKC-mediated phosphorylation of HSP27 and PKA-mediated phosphorylation of HSP20 play a crucial role in directing the cell either to contract or to relax. Thus the molecular signaling switch (PKC and PKA) acts by modulating thin-filament dynamics through alterations in phosphorylation or molecular associations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The following reagents were purchased: monoclonal mouse anti-TM antibody, monoclonal mouse FITC-α-smooth muscle actin antibody, and monoclonal mouse anti-CaD from Sigma, St. Louis, MO; rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-HSP27 (ser78) antibody and rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-CaD (ser789) antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; rabbit anti-phospho-PKC-α (ser657) antibody from Millipore, Billerica, MA; mouse monoclonal anti-HSP27 antibody from Stressgen. Secondary antibodies were anti-phospho-MLC20 (ser20) antibody from Abcam, Cambridge, MA; anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase from Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA; and goat anti-mouse IgG (Fc specific) horseradish peroxidase conjugate from Millipore Billerica, MA. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was from Sigma; polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes were from Bio-Rad Laboratories; protein G Sepharose and enhanced chemiluminescence (32) detection reagents were from Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ; autoradiography film (HyBlot CL) was from Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ; G-418, penicillin/streptomycin, FBS, collagen IV, and DMEM were from GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, NY; and collagenase type II was from Worthington, Lakewood, NJ. The mounting reagent was Prolong antifade from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma.

Methods

Preparation of smooth muscle cells from the rabbit rectosigmoid.

The animals were handled as per the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals established by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals at the University of Michigan. The study protocol was approved by University Committee (protocol no. 08337).

Rabbit sigmoid colon was stripped of serosa, longitudinal muscle layer, and mucosa before being washed multiple times in HBSS containing 2× antibiotic/antimycotic. The tissue was finely minced and subjected to three additional washings. The tissue was digested with 0.1% collagenase type II and 20 μg/ml DNase I in HBSS for 1 h at 37°C. The digestion mixture was subjected to filtration with a 410-μm Nytex filter to remove cellular debris. The tissue was washed three times with HBSS before being digested a second time as described above. The cells were recovered by centrifugation at 600 g for 5 min and then washed three times before plating in culture medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2× penicillin-streptomycin, 1× antimycotic, 0.5% l-glutamine). Cells were grown to confluence to be used for experiments.

Construction of HSP20 phosphomutants.

HSP20 phosphomutants (16A-HSP20: nonphosphorylatable; 16D-HSP20: phosphomimic) cDNAs were generated by using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. In 16D-HSP20 mutant cDNA, serine-16 phosphorylation site was mutated to aspartate to mimic phosphorylated HSP20 and in 16A-HSP20 mutant; serine-16 phosphorylation site was mutated to glycine to mimic nonphosphorylatable HSP20. Specificity of the mutant cDNAs was verified by sequence analysis. Predicted translation products were determined by use of the ExPASy translation tool. The mutant cDNAs were cloned into pcDNA 3.1 with myc-His-COOH-terminal tag.

Immunoprecipitation.

Antibody (1–2 μg) was added to 500 μg of sample protein in 500 μl of lysis buffer [in mM: 1 Na3VO4, 1 NaF, 2 PMSF, 5 EDTA, 1 Na4MoO4, 1 DTT, 20 NaH2PO4, 20 Na2HPO4, and 20 Na4P2O7·10 H2O, with 50 μl/ml DNase-RNase, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml antipain-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.08 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 60 μg/ml phosphoramidon, and 5 mg/ml Pefbloc] and rocked overnight at 4°C. Then 50 μl of 50% protein G-Sepharose bead slurry was added and the mixture was rocked at 4°C for 2 h. The beads bound with proteins were then collected by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 3 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the bead pellet was washed three times at room temperature with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) bead wash buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6). The beads were then resuspended in 25 μl of 2× sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Proteins from the immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. The membrane was immunoblotted with the desired antibodies as described previously (57). Replicates of experiments were performed with completely separate sets of cells.

Immunoblotting.

The proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membrane as described previously (57). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h and incubated in an appropriate dilution of primary antibody in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. The membrane was washed thrice with TBST to remove unbound primary antibody for 15 min each wash at room temperature. The membrane was then incubated in an appropriate dilution of secondary antibody in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed three times with TBST for 15 min each wash at room temperature to remove unbound secondary antibody. The membrane was then incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent for 1 min. The proteins were detected on the membrane by immediately exposing the membrane to the film for 30 s and 1 min.

Transfection of smooth muscle cells with HSP20 phosphomutants.

CSMC were transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA cloned in vectors pcDNA3.1 using QIAGEN Effectene transfection kit as described previously (48). Stable ectopic expression of exogenous HSP20 phospho-mutants in CSMC were confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-HSP20 antibody and 6-His antibody (22).

Subcellular fractionation of cultured circular smooth muscle cells.

Soluble and particulate fractions from cultured CSMC were fractionated as described for freshly isolated smooth muscle cells (47). Briefly, stably transfected cultures of smooth muscle cells were grown to confluence before being incubated with or without 0.1 μM ACh for 30 s or 4 min, washed 3× with ice-cold PBS, placed on an ice bath and scrapped into ice-cold PBS. After recovery by centrifugation, cells were resuspended in a TBS solution supplemented with (in mM) 20 NaH2PO4, 20 Na2HPO4, and 20 Na4P2O7·10 H2O, pH 7.4, containing 1 Na3VO4, 1 NaF, 2 PMSF, 5 EDTA, 1 DTT, and a complete protease inhibitor cocktail. The cells were then sonicated four times for 30 s each, intact cells removed by low-speed centrifugation, and the lysed cells were centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h. The supernatant fraction was collected as soluble fraction and the pellet was resuspended in RIPA buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and sonicated twice for 30 s. Insoluble debris were removed by centrifugation and the particulate fraction was collected. The protein content of the soluble and particulate fraction was determined by using a protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad). Protein from the soluble fraction was concentrated by ethanol precipitation before immunoblot analysis.

Analysis of HSP20 recombinants by isoelectric focusing.

Briefly, stably transfected cultured CSMC were grown to confluence and serum starved for 24 h prior to being harvested in a lysis buffer containing 9 M urea, 0.5% DTT, 3% CHAPS, and 4% ampholytes, pH 3–10. Following centrifugation to remove any insoluble cellular components, lysates were subjected to electrophoresis on slab isoelectric focusing (IEF) gels (pH gradient 1 part 3–10: 4 part 4–7). Gels were transferred to PVDF membranes and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described above. A 1:300 dilution of antibody was used to detect the 6-His epitope of the recombinant HSP20 proteins.

Single cell contraction assay.

Contraction experiments were performed essentially as previously described (47). Briefly, transfected cells were cultured to confluence. Fresh medium lacking serum was added to each culture flask. Cells were then scraped and pipetted vigorously to break up cell clumps. Cells were transferred to round-bottom polypropylene tissue culture tubes and allowed to float freely for 48 h with occasional shaking. Aliquots of cultured cell suspensions were left untreated or stimulated with ACh (10−7 M) for 30 s or 4 min. The reactions were stopped by the addition of acrolein to a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol). Individual cell length was measured by computerized image micrometry. The average length of cells in the control state or following the addition of ACh was obtained from >40 cells encountered randomly in successive microscopic fields.

Immunostaining.

HSP20-transfected stable CSMC were grown on coverslips till 70% confluency in selection media containing G418. Cells were rinsed with PBS (pH 7.4), fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 30 min, washed twice with 7.5% glycine buffer (pH 7.5) for 5 min each to remove the fixative, and washed twice with PBS. Fixed cells were then permeabilized with 1 ml of permeabilization buffer (0.15% Triton-X and 5% goat serum in PBS) for 10 min at room temperature, incubated with monoclonal FITC-α-smooth muscle actin (1:200) diluted in the antibody dilution buffer (1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) overnight at 4°C. After overnight incubation, the cells were washed thrice with PBS for 5 min each, and 200 μl of DAPI (0.5 μg/ml) was added and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, in the dark. The cells were again washed thrice with PBS with each wash-incubate for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. Coverslips were mounted on slides by use of ProLong Gold antifade mounting reagent.

Data analysis.

The experimental protocol calls for cells isolated from circular muscle of the colon of each animal to be divided into three groups: 1) control (unstimulated; stimulated with ACh for 30 s; stimulated with ACh for 4 min); 2) 16D-HSP20-transfected CSMC (unstimulated; stimulated with ACh for 30 s; stimulated with ACh for 4 min); and 3) 16A-HSP20-transfected CSMC (unstimulated; stimulated with ACh for 30 s; stimulated with ACh for 4 min). In each set of experiments, the response obtained was compared with control unstimulated cells using ANOVA. The response was considered significant (P value) at equal to or less than 0.05. The mean values are means of the response obtained from different sets of cells isolated from different animals, represented by n.

Data analysis was done as described previously (57). Briefly, Western blot bands were quantitated by use of a densitometer (model GS-700, Bio-Rad Laboratories), and band volumes (absorbance units × mm2) were calculated and expressed as percentage of the total volume. Band data are within the linear range of detection for each antibody used. The control band intensity was standardized to 100%. The band intensities of samples from treated cells were compared with the control and expressed as percent change from the control.

RESULTS

Contraction of CSMC is associated with contractile agonist-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 whereas relaxation is associated with relaxant-induced phosphorylation of HSP20. In colonic circular smooth muscle, agonist-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 is a crucial event in modulating the thin-filament-mediated regulation of contraction. Studies on thin-filament modulations during relaxation are scanty. Investigations were done to examine the effect of relaxant-induced HSP20 phosphorylation on HSP27 phosphorylation-mediated alterations in subsequent phosphorylations, associations, and regulation of contraction at thin-filament level.

Characterization of Rabbit CSMC Transfected with HSP20 Phosphomutant

Molecular cloning and development of HSP20 mutants.

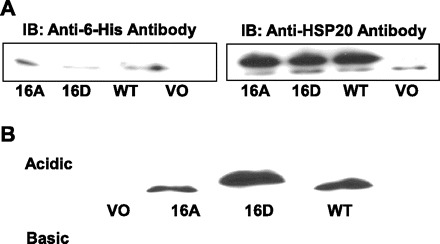

A full-coding-length cDNA of HSP20 was amplified from RNA isolated from rat heart by RT-PCR with primers specific for rat HSP20. Sequence analysis of amplified cDNA differed from known rat sequence with only three nucleotide substitutions. The cDNA was cloned into an expression vector pcDNA 3.1/myc-His. Using site-directed mutagenesis kit, ser16 residue was mutated to either alanine (to generate nonphosphomimic HSP20 mutant, 16A-HSP20) or aspartic acid (to generate phosphomimic HSP20 mutant, 16D-HSP20). Expression of recombinant HSP20 mutant was analyzed on SDS-PAGE. Recombinant mutant HSP20 migrated thru SDS-PAGE at an apparent higher molecular mass than endogenous protein owing to the myc-His carboxy extension and was detected by use of 6-His antibody and HSP20 antibody (Fig. 1A). Recombinant mutants HSP20 were characterized by IEF. 16D-HSP20 mutant recombinant protein exhibited a slightly more acidic isoelectric point than 16A-HSP20 mutant or wild-type forms when subjected to IEF (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Molecular cloning of HSP20. Full-length cDNA of HSP20 in-frame was cloned into the expression vector pcDNA 3.1/myc-His. Sequence analysis revealed that this variant cDNA for HSP20 differed at only 3 nucleotide positions compared with the GenBank (NM_138887.1) rat HSP20 sequence. Phosphomimic-HSP20 (16D-HSP20) or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 (16A-HSP20) mutants were generated by using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. Specific point mutations were verified by sequence analysis of 16D-HSP20 and 16A-HSP20. Predicted translation products were determined by using the ExPASy translation tool. A: whole cell lysates from stable transfected colonic smooth muscle cell (CSMC) expressing recombinant HSP20 (16A, lane 1), phosphorylated HSP20 (16D, lane 2), wild-type HSP20 (WT, lane 3), or vector with no insert (VO, lane 4) were probed with anti-His antibody (left) or anti-HSP20 antibody (right). Increased molecular weight of the recombinant protein due to the myc-His COOH-terminal extension was observed. IB, immunoblot. B: duplicate samples from whole cell lysates from stable-transfected CSMC with vector containing no insert (lane 1) or expressing recombinant HSP20 (lanes 2-4) were separated on an isoelectric focus gel and probed with anti-His antibody. 16D-HSP20 showed an increased acidic pI.

Effect of HSP20 phosphorylation state on resting cell length.

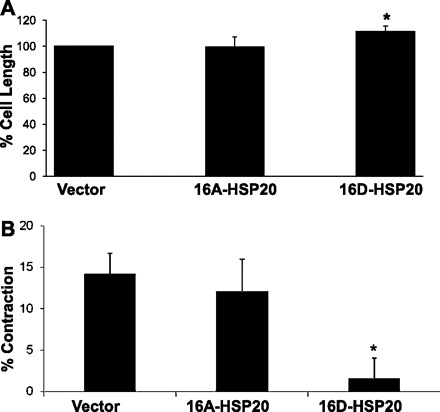

To determine the effect of HSP20 on cell length in the absence of contractile agonist, we compared the resting lengths of CSMC transfected with recombinant HSP20 mutant. Primary cultures of rabbit CSMC cells were stably transfected with the phosphomimic form of HSP20 (16D), with the form unable to be phosphorylated (16A), or with the pcDNA 3.1/myc-His expression vector containing no insert (vector only). Resting cell lengths of CSMC expressing the 16A-HSP20 were 99.7 ± 7.4% compared with the cell lengths of CSMC transfected with vector only. Thus no difference was observed between CSMC expressing 16A-HSP20 compared with cells transfected with vector only (P > 0.05). However, the resting cell length of CSMC expressing 16D-HSP20 were 111.3 ± 4.4% compared with the cell lengths of CSMC transfected with vector only (Fig. 2A). 16D-HSP20 expressing CSMC were significantly longer than CSMC transfected with vector (P ≤ 0.05). Longer cells are able to contract at a greater percentage of cell length than shorter cells (8), so examination was done on the ability of CSMC expressing HSP20 mutant to contract in response to ACh.

Fig. 2.

A: effect of mutant HSP20 on cell length of CSMC at rest. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 or vector alone were fixed and the cell lengths were measured at rest. There was no difference in the resting cell length between CSMC transfected with the vector only and CSMC expressing 16A-HSP20 (99.7 ± 7.4%), whereas CSMC expressing 16D-HSP20 were significantly longer (111.3 ± 4.4%). B: effect of mutant HSP20 on cell length of CSMC cell length upon ACh stimulation. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 or were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. After stimulation the cells were fixed and the cell lengths were measured. CSMC transfected with vector only contracted an average of 14.25 ± 2.42% whereas CSMC expressing the 16A-HSP20 contracted 12.2 ± 3.75%. Cells expressing the 16D-HSP20 failed to contract (1.6 ± 2.4%). Values are means ± SE of 3 experiments, *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 (Student's t-test).

Effect of HSP20 phosphorylation state on CSMC contraction.

Expression and ser16 phosphorylation of HSP20 have been strongly associated with relaxation in smooth muscle (3, 5, 9) and treatment of CSMC with the relaxant neuropeptide, VIP, caused significant and substantial phosphorylation of HSP20 by 30 s posttreatment (21). These observations led us to perform studies to determine the effect of expression of recombinant HSP20 mutant on early contraction in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either of the recombinant HSP20 mutants were treated with ACh for 30 s to induce contraction and the cell lengths were measured. Changes in cell length are expressed as mean contraction ± SE. CSMC transfected with vector only contracted an average of 14.25 ± 2.42% whereas CSMC expressing the 16A-HSP20 mutation contracted 12.2 ± 3.75%. There was no significant difference in contraction between these cells. However, CSMC expressing the 16D-HSP20 mutation failed to contract (1.6 ± 2.4%), which was substantially and significantly (P ≤ 0.05; N = 3) less than CSMC transfected with either 16A-HSP20 mutant or with vector alone (Fig. 2B).

Effect of HSP20 Phosphorylation on ACh-Induced Association of Contractile Proteins in Rabbit CSMC

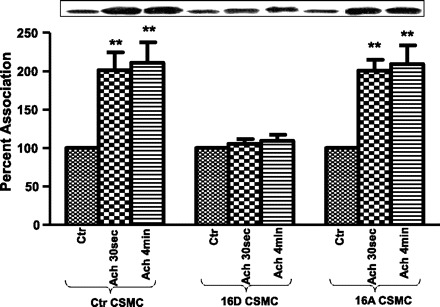

Interaction of TM with HSP27.

TM interacts with phosphorylated HSP27, which aids in maintenance of displaced TM on actin to expose myosin-binding sites for actomyosin interaction leading to contraction (59). CSMC exhibited reduced ACh-mediated interaction of TM with HSP27 upon preincubation with VIP (58). Here we study the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were immunoprecipitated with anti-TM antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-HSP27 antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed inhibition of ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27 (114.46 ± 7.1% after ACh 30 s; 117.11 ± 4% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≈ 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed ACh-induced increase in association of TM with HSP27 (195.99 ± 17.91% after ACh 30 s; 207.26 ± 13.9% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05), similar to nontransfected control CSMC (195.35 ± 15.85% after ACh 30 s; 205.39 ± 14.2% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). The association of TM with HSP27 was diminished in the presence of phosphomimic HSP20 (Fig. 3). The diminished association of TM with HSP27 was not due to changes in amount of TM immunoprecipitated (Fig. 4B). Since CaD acts as a counterpart with TM in exposing myosin-binding sites on actin and preventing the inhibition of actomyosin ATPase activity, we investigated the effect of phosphorylated HSP20 on the interaction of TM with CaD.

Fig. 3.

ACh-induced interaction of tropomyosin (TM) with HSP27 in CSMC. CSMC transfected with phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were either stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoprecipitated with anti-TM antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-HSP27 antibody. Inset: Western blot representing the data. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27 whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in association of TM with HSP27 similar to nontransfected control (Ctr) CSMC, **P ≤ 0.05 (Student's t-test).

Fig. 4.

A: ACh-induced interaction of TM with caldesmon (CaD) in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoprecipitated with anti-TM antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-CaD antibody. Inset: Western blot representing the data. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced dissociation of TM from CaD whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in dissociation of TM from CaD similar to nontransfected control CSMC. **P ≤ 0.02 (Student's t-test). B: amount of TM in immunoprecipitates of TM in HSP20 phosphomutant-transfected CSMC. Representative blots indicating equal amount of TM in TM immunoprecipitates from control and HSP20 phosphomutant-transfected CSMC. Immunoprecipitates of TM from whole cell lysates from control and HSP20 phosphomutant transfected HSP20 were used to analyze the association of TM with HSP27 and with CaD. These TM immunoprecipitates were stripped and probed with TM antibody to determine the amount of TM in TM immunoprecipitates. The data show that the changes observed in the amount of HSP27 and CD in TM immunoprecipitates were not due to changes in amount of TM in immunoprecipitates. *P ≤ 0.05.

Interaction of TM with CaD.

CaD binds to actin-TM and inhibits actomyosin ATPase activity. Upon contractile stimulation, CaD is phosphorylated whereby CaD dissociates from TM, which displaces on actin to expose myosin-binding sites for actomyosin interaction, leading to contraction (37). Previous studies have shown that VIP inhibits the dissociation of TM from CaD. Investigations were carried out to study the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation of ACh-induced dissociation of TM from CaD (58). For these studies, CSMC transfected with HSP20 phosphomutants were used. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were immunoprecipitated with anti-TM antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-CaD antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed no ACh-induced dissociation of TM from CaD (98.39 ± 2.45% after ACh 30 s; 100.22 ± 4.41% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P > 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP27 showed significant ACh-induced dissociation of TM from CaD (75.61 ± 7.77% after ACh 30 s; 70.21 ± 15.26% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). These values were similar to nontransfected control CSMC (72.13 ± 4.53% after ACh 30 s; 70.70 ± 5.19% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). These findings suggest that the contraction-related dissociation of TM from CaD, which is inhibited by phosphorylation of HSP20, inhibits smooth muscle contraction (Fig. 4A). The inhibition of dissociation TM from CaD was not due to changes in the amount of TM immunoprecipitated (Fig. 4B). Since the interactions of contractile proteins are associated with the phosphorylation status of contractile proteins, investigations were carried out to examine whether the alterations in contraction-associated interactions were due to alteration in contraction-associated phosphorylations.

HSP20 Phosphorylation Affects ACh-Induced Phosphorylation of Contractile Proteins in Rabbit CSMC

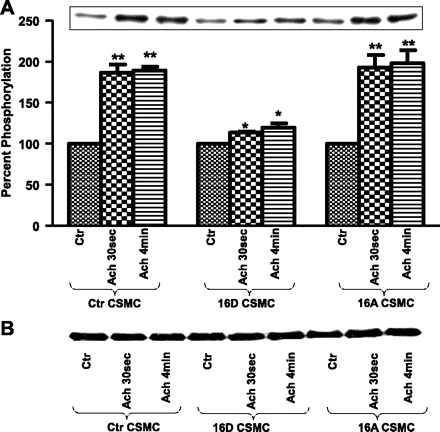

Phosphorylation of HSP27.

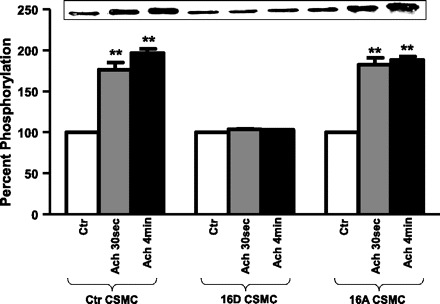

Previous studies have shown that preincubation of CSMC with VIP resulted in inhibition of ACh-induced sustained increase in phosphorylation of HSP27 concomitant with increase in HSP20 phosphorylation (58). HSP20 phosphorylation is indicative of relaxation of smooth muscle. Thus investigations were carried out to study whether the VIP-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated sustained increase in phosphorylation of HSP27 was due to VIP-induced phosphorylation of HSP20. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-specific HSP27 (ser78) antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed a significant reduction of ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 (113.36 ± 0.8% after ACh 30 s; 119.74 ± 2.09% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≈ 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed increase in ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 (192.85 ± 8.8% after ACh 30 s; 198.10 ± 9.1% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05) similar to nontransfected control CSMC (186.53 ± 5.7% after ACh 30 s; 189.06 ± 2.6% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). Results indicate that presence of phosphorylated HSP20 inhibits phosphorylation of HSP27 (Fig. 5A). Equal amounts of protein samples were loaded on the gel (Fig. 5B). Since phosphorylation of HSP27 is crucial for modulation of thin-filament-mediated regulation of contraction, further investigations were carried out to study the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation on subsequent phosphorylation thin-filament regulatory proteins.

Fig. 5.

A: ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-HSP27 (ser78) antibody. Inset: Western blot representing the data. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of HSP27 similar to nontransfected control CSMC. *P ≈ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.05 (Student's t-test). B: ACh-induced change in total HSP27. Whole cell lysate from control and HSP20 phosphomutant-transfected cells analyzed for phosphorylation of HSP27 were stripped and probed with anti-HSP27 antibody to demonstrate that the changes observed in the phosphorylation of HSP27 were not due to changes in total HSP27.

Phosphorylation of TM.

TM is a significant thin-filament binding protein that regulates contraction of smooth muscle cells by modulating actin-myosin interactions. TM averts the activation of myosin Mg2+-ATPase owing to its inhibitory position on actin by covering myosin-binding sites (57). ACh induces phosphorylation of TM in CSMC (57). Preincubation of CSMC with VIP significantly inhibits TM phosphorylation (58). Investigations were done to study the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation on ACh-induced phosphorylation of TM. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphoserine antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-TM antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed complete inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of TM (103.55 ± 0.9% after ACh 30 s; 103.39 ± 0.1% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P > 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed increase in ACh-induced phosphorylation of TM (176.54 ± 8.6% after ACh 30 s; 196.71 ± 5.3% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). These values were similar to nontransfected control CSMC (182.42 ± 8.6% after ACh 30 s; 188.36 ± 4.2% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). The results suggest that phosphorylation of HSP20 interferes with phosphorylation of TM altering the thin-filament regulation of contraction (Fig. 6). Since phosphorylation of CaD reduces its affinity to TM whereby TM displaces on actin to expose myosin-binding sites, further investigations were done to study the effect of phosphorylation of HSP20 on CaD phosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

ACh-induced phosphorylation of TM in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for 30 either s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphoserine antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-TM antibody. Inset: Western blot representing the data. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of TM whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of TM similar to nontransfected control CSMC. **P ≤ 0.05 (Student's t-test).

Phosphorylation of CaD.

CaD is associated with actin-TM in smooth muscle (36) and is known to inhibit the actin-activated Mg2+-ATPase of smooth muscle myosin, suggesting a possible physiological role for CaD in regulating the contractile state of smooth-muscle. CaD phosphorylation prevents its inhibitory action on the actomyosin Mg2+-ATPase and also weakens the association of TM with CaD. Preincubation of CSMC with VIP resulted in inhibition of ACh-induced sustained increase in phosphorylation of CaD (58). Inhibition of CaD phosphorylation suggests that contraction is affected and thus further studies were done to investigate whether VIP-induced inhibition of CaD phosphorylation was due to HSP20 phosphorylation. The effect of HSP20 phosphorylation on ACh-induced phosphorylation of CaD was studied by use of CSMC transfected with HSP20 phosphomutants. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-CaD (ser789) antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed absolute inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of CaD (104.48 ± 1.16% after ACh 30 s; 107.05 ± 0.7% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P > 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed increase in ACh-induced phosphorylation of CaD (157.46 ± 3.02% after ACh 30 s; 172.52 ± 5.4% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). These values were similar to nontransfected control CSMC (157.01 ± 13.4% after ACh 30 s; 166.79 ± 15.04% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). Data showed that HSP20 phosphorylation has a role in inhibition of CaD phosphorylation (Fig. 7A). Data further showed that the inhibition of dissociation TM from CaD is not due to changes in amount of TM immunoprecipitated (Fig. 7B). Since phosphorylation of TM and CaD are both PKC mediated (17), inhibition of their phosphorylation could be due to reduction in activation of PKC-α. Thus further investigations were carried out to study the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation status on PKC-α activation.

Fig. 7.

A: ACh-induced phosphorylation of CaD in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-CaD (ser789) antibody. Inset: Western blot representing the data. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of CaD whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of CaD similar to nontransfected control CSMC. **P ≤ 0.05 (Student's t-test). B: ACh-induced change in total CaD. Whole cell lysate from control and HSP20 phosphomutant-transfected cells analyzed for phosphorylation of CaD were stripped and probed with anti-CaD antibody to demonstrate that the changes observed in the phosphorylation of CaD were not due to changes in total CaD.

Phosphorylation of PKC-α.

In CSMC, PKC-α is translocated to membrane and autophosphorylated at ser657, leading to its activation in response to ACh stimulation. A significant decrease in ACh-induced phosphorylation of PKC-α was observed in the CSMC preincubated with VIP (58). Thus it was of interest to examine whether the VIP-induced inhibition in phosphorylation of PKC-α was due to phosphorylation of HSP20. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-phospho-PKC-α (ser657) antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed significant reduction in ACh-induced phosphorylation of PKC-α (124.90 ± 3.71% after ACh 30 s; 122.09 ± 7.21% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P = 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of PKC-α (173.71 ± 34.10% after ACh 30 s; 179.08 ± 26.51% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). These values were similar to nontransfected control CSMC (179.48 ± 2.31% after ACh 30 s; 172.17 ± 7.11% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P ≤ 0.05). Thus the data suggest that HSP20 phosphorylation significantly altered phosphorylation of PKC-α, resulting in alteration in activation of PKC-α (Fig. 8A). Data further showed that the inhibition of dissociation TM from CaD is not due to changes in amount of TM immunoprecipitated (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

A: ACh-induced phosphorylation of PKC-α in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PKC-α (ser657) antibody. Inset: Western blot representing the data. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of PKC-α whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of PKC-α similar to nontransfected control CSMC. *P ≈ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.05 (Student's t-test). B: ACh-induced change in total PKC-α. Whole cell lysate from control and HSP20 phosphomutant-transfected cells analyzed for phosphorylation of PKC-α were stripped and probed with anti-PKC-α antibody to demonstrate that the changes observed in the phosphorylation of PKC-α were not due to changes in total PKC-α.

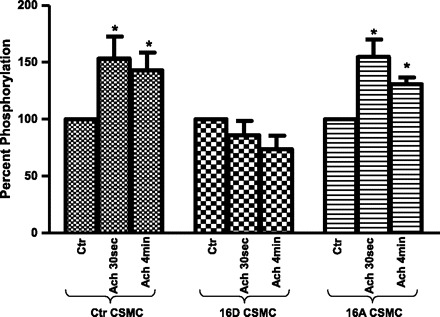

Phosphorylation of MLC20.

Phosphorylation of MLC20 is an early event during the contraction of CSMC. A significant and sustained increase in phosphorylation of MLC20 is seen in CSMC in response to ACh stimulation. Investigations were done to examine the effect of HSP20 phosphomutant on ACh-induced phosphorylation of MLC20. Proteins from whole cell lysates of CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 or 16A-HSP20 cDNA were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-phospho-MLC20 antibody. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of MLC20 (86.01 ± 12.62% after ACh 30 s; 73.93 ± 11.76% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P < 0.05), whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of MLC20 (154.74 ± 7.78% after ACh 30 s; 131.93 ± 8.31% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P < 0.05), similar to control CSMC transfected with vector only (153.20 ± 19.38% after ACh 30 s; 143.06 ± 15.70% after ACh 4 min; n = 3, P < 0.05) (Fig. 9). Thus the data suggest that HSP20 phosphorylation significantly altered agonist-induced phosphorylation of MLC20 resulting in inhibition of contraction.

Fig. 9.

ACh-induced phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC20) in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were stimulated with 0.1 μM ACh for either 30 s or 4 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-MLC20 (ser20) antibody. Graph: ectopic expression of phosphomimic-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of MLC20 whereas ectopic expression of nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 in CSMC exhibited ACh-induced increase in phosphorylation of PKC-α similar to control CSMC. *P ≤ 0.05 (Student's t-test).

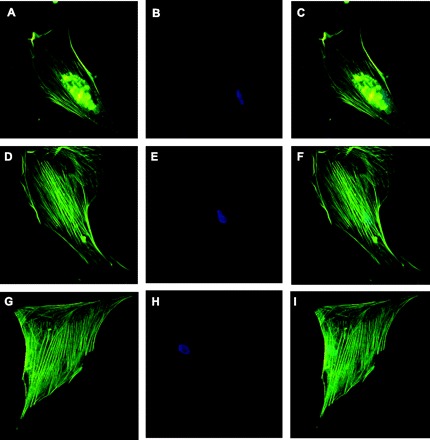

Effects of HSP20 on Contractile Action Microfilament in Rabbit CSMC

To determine whether the observed contractile inhibitory effect of phosphorylated HSP20 was due to microfilament disruption, CSMC were immunostained with an antibody directed against α-smooth muscle actin. Immunofluorescence analysis of stably transfected CSMC expressing either 16A-HSP20 or 16D-HSP20 demonstrated no disruption of F-actin compared with CSMC transfected with vector only (Fig. 10). The results suggest that inhibition of contractile response mediated by 16D-HSP20 is not due to disruption of actin cytoskeleton.

Fig. 10.

Effect of HSP20 phosphomutants on actin cytoskeleton in CSMC. CSMC transfected with either phosphomimic-HSP20 or nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 were grown on coverslips and immunostained with FITC-tagged anti-F-actin antibody. CSMC were also stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain the nucleus. CSMC transfected with vector only: stained with FITC-tagged anti-actin antibody (A), stained with DAPI (B), merge (C). CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20: stained with FITC-tagged anti-actin antibody (D), stained with DAPI (E), merge (F). CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20: stained with FITC-tagged anti-actin antibody (G), stained with DAPI (H), merge (I). Neither 16A-HSP20-transfected CSMC nor 16D-HSP20-transfected CSMC showed any disruption of actin cytoskeleton and both were similar to vector only-transfected CSMC.

DISCUSSION

Smooth muscle contraction occurs when cross bridges are formed by the interaction of myosin S1 heads with actin molecules (63). The formation of cross bridges is regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of MLC20 (13). MLC20 phosphorylation is only transient in the continued presence of a contractile agonist, while force is maintained (41). The dissociation between the state of MLC20 phosphorylation and force generation suggests that mechanisms other than thick-filament (myosin and MLC20) regulation are operative in contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle. Research suggests a role for the thin filament binding proteins: calponin, CaD, and TM in maintaining contraction at reduced levels of MLC20 phosphorylation. Balance between the phosphorylation states of HSP27 and HSP20 represents a molecular signaling switch for contraction and relaxation (50). Phosphorylation of HSP27 and HSP20 plays a fundamental role in thin-filament-mediated regulation of smooth muscle contraction by modulating the downstream molecular mechanical switch (TM) by regulating the interactions of thin-filament binding proteins (6, 24, 29, 62).

Actin-myosin interaction is regulated by actin-binding proteins, TM and CaD. TM binds to itself end to end and wraps around the actin molecule to stabilize the thin-filament assembly (57) while blocking the myosin-binding sites on actin. CaD, on the other hand, is an actin-TM binding protein that regulates smooth muscle contraction by inhibiting activation of myosin Mg2+-ATPase and positioning TM on actin (27, 37). TM also averts the activation of myosin Mg2+-ATPase because of its inhibitory position on actin by covering myosin-binding sites. Thus CaD and TM complement each other in preventing the activation of myosin Mg2+-ATPase, a prime driver of actin-myosin interaction (52). Phosphorylation of CaD reverses the inhibition of myosin Mg2+-ATPase activation and amends the affinity of CaD to actin-TM, thus leading to contraction (35, 39).

Relaxation, an inhibition or termination of contraction, has been known to involve increase in myosin phosphatase activity with decrease in the intracellular calcium levels (14, 23, 31, 43, 48) leading to dephosphorylation of MLC20. Myosin phosphatase activity is regulated by two pathways: PKC-mediated phosphorylation of CPI-17 (Thr-38) that is a potent inhibitor of phosphatase activity and Rho-mediated phosphorylation of myosin targeting subunit that lowers the affinity of phosphatase to MLC2o. Dephosphorylation of MLC20 is the prime indicator of relaxation; however, very little is known about the regulation of actin-myosin dynamics at thin-filament level during relaxation. Here we provide an insight into the role of HSP20 phosphorylation in the modulation of thin-filament regulatory proteins in relaxation milieu. Earlier investigations have shown that preincubation with VIP resulted in inhibition of contractile-associated phosphorylation of HSP27, CaD, and TM (58). Concurrently, ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27 with synchronized dissociation of CaD from TM was inhibited upon preincubation with VIP (58). Phosphorylation of HSP27 is associated with contractile related events and plays a crucial role in actomyosin interaction (7, 28, 62). Inhibition of phosphorylation of HSP27 may affect its function in actomyosin dynamics and terminate contraction leading to relaxation. Similarly, phosphorylation of CaD and TM are known to be associated with cross bridging of actin with myosin (1, 26, 56). Inhibition of phosphorylation of CaD and TM may also lead to prevention of interaction of actin with myosin, which further terminates contraction, leading to relaxation. Phosphorylation of CaD leads to its dissociation from TM while associating it to HSP27 during contraction (56). CSMC exposed to VIP had reduced association of TM with HSP27 whereas there was no significant dissociation of TM from CaD (58). Inhibition of these interactions prevents the displacement of TM from actin and thus maintains its position on actin to block the myosin-binding sites. This prevents association of actin with myosin and thus prevents contraction.

Two HSP20 phosphomutants cDNAs constructed in our laboratory (22) were used for investigations: 16A-HSP20, which mimics nonphosphorylatable HSP20 in which amino acid serine at 16 was mutated to alanine, and 16D-HSP20, which mimics phosphorylated HSP20 in which amino acid serine at 16 was mutated to aspartate. CSMC were transfected with these phosphomutants separately. CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 showed inhibition of ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27 and of dissociation of TM from CaD whereas CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 exhibited an increase in ACh-induced association of TM with HSP27 and dissociation of TM from CaD. Furthermore, ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27, TM, and CaD was inhibited in CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20. CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20 showed an increase in ACh-induced phosphorylation of HSP27, TM, and CaD similar to nontransfected control CSMC. It is important to note that the phosphorylation of PKC and HSP27 is not completely inhibited, there is only a partial inhibition whereas phosphorylation of TM and CaD is completely inhibited. These studies thus suggest that relaxation at the thin-filament level, i.e., prevention of actomyosin interaction, is achieved by HSP20 phosphorylation-mediated alterations in both the phosphorylation and association of thin-filament proteins. Phosphorylation of both TM and CaD is mediated by PKC-α, so investigations were carried out to examine the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation on PKC-α activation. CSMC overexpressing 16D-HSP20 showed significant decrease in ACh-induced phosphorylation of PKC-α, which is essential for activation of PKC-α. From the data, we interpret that ACh-induced phosphorylation of PKC-α was significantly reduced in CSMC transfected with 16D-HSP20 compared with untransfected or CSMC transfected with 16A-HSP20. Earlier studies from our laboratory have shown that CSMC overexpressing nonphosphomimic HSP27 exhibited inhibition in translocations of PKC-α in response to ACh (47). It is thus possible that HSP20 phosphorylation inhibits HSP27 phosphorylation, which subsequently reduces the translocation of PKC-α, leading to reduction in PKC-α activation. This results in inhibition in phosphorylation of TM and CaD, thus leading to inhibition of subsequent downstream association resulting in termination of contraction.

Relaxation in other smooth muscle cells has been shown to be associated with PKA/PKG-mediated phosphorylation of HSP20 at ser16 (2, 4, 9, 15, 33, 45). It has been reported that cGMP-mediated phosphorylation of HSP20 may cause relaxation in arterial smooth muscle without proportional decrease in myosin light chain phosphorylation (49). Here we show that ACh-induced MLC20 phosphorylation is inhibited in CSMC overexpressing phospho-HSP20 whereas there was increased ACh-induced MLC20 phosphorylation in CSMC overexpressing nonphosphorylatable-HSP20 (Fig. 9). Comparing the basal level of MLC20 phosphorylation in CSMC transfected with HSP20 phosphomutant showed no significant difference in the levels of MLC20 phosphorylation. Earlier studies from our laboratory have shown significant and rapid PKA-mediated phosphorylation of HSP20 (within 30 s) in CSMC treated with VIP (21). Inhibition of ACh-induced phosphorylation of MLC20 in CSMC stably transfected with 16D-HSP20 suggests that phosphorylation of HSP20 plays a dominant role in preventing ACh-mediated phosphorylation of MLC20, leading to relaxation. The mechanism of inhibition of phosphorylation of MLC20 in CSMC expressing phospho-HSP20 could be attributed to either due to decrease in myosin kinase activity or increase in myosin phosphatase activity. The data reinforce the importance of two parallel pathways converging at MLC20 phosphorylation to initiate contraction in CSMC. The results suggest that changes at the thin-filament level directly or indirectly influence MLC20 phosphorylation levels. Previous studies have reported that PKA 1) phosphorylates RhoA, which inhibits the phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase target subunit and activates myosin phosphatase, leading to dephosphorylation of MLC20 (44), and 2) phosphorylates MLCK, thereby inhibiting MLC20 phosphorylation (51). Relaxation-induced inhibition of MLC20 phosphorylation could be a complementary event to phosphorylation of HSP20 to terminate contraction. Further studies need to be performed to investigate the mechanism involved in the role of HSP20 phosphorylation in MLC20 phosphorylation in CSMC. It has been suggested that force suppression during relaxation could be mediated by inhibition of myosin binding at thin- or thick-filament levels (40). In gastrointestinal smooth muscle, data suggest that HSP20 phosphorylation mediates relaxation by inhibiting the exposure of myosin-binding sites on actin needed for actomyosin interaction. This is achieved by preventing the dissociation of TM from CaD that is required for exposure of myosin-binding sites on actin.

It is thus possible that phosphorylation of HSP20 inhibits contraction by its effect on the regulation of contractions at the thin-filament level by altering the phosphorylations and associations of thin-filament regulatory proteins, which may lead to termination of contraction resulting in relaxation. Phosphorylation of HSP27 has been known to inhibit phosphorylation of HSP20. Investigations were carried out to study whether relaxation-related phosphorylation of HSP20 altered the phosphorylation of HSP27, which further affected its downstream function related to phosphorylation and the association of different contractile proteins. Studies were done to investigate the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation on phosphorylation and association of TM, CaD, and HSP27.

It is interesting to note that CSMC overexpressing 16D-HSP20 exhibit significantly longer cell length at rest (relaxed state) while exhibiting significantly decreased percent shortening in response to contraction by ACh (Fig. 2). Because cell length positively correlates with the ability of a cell to contract, the increase in cell length associated with expression of 16D-HSP20 should have allowed these cells to contract at least to the same extent as the cells transfected with the vector only or 16A-HSP20-expressing cells. The increased length of cells expressing 16D-HSP20 may represent a hyperrelaxed state that would facilitate the distension required at the leading edge of peristaltic motility. HSP20 may utilize multiple modes of action in regulating colonic smooth muscle relaxation. Peristalsis could require a myogenic disruption in cyclic contractile signaling to allow leading edge relaxation to occur.

Immunofluorescence studies showed no disruption of actin cytoskeleton in CSMC overexpressing either 16A-HSP20 or 16D-HSP20, suggesting no effect of HSP20 on cytoskeleton reorganization and actin microfilament integrity. Phosphorylated HSP20 has been suggested to be a dominant inhibitor of smooth muscle contraction with its dual action: 1) by disrupting F-actin structure and 2) by inhibiting actin binding to myosin by its troponin I-like motif at amino acids 110–123. Studies investigating the effect of HSP20 phosphorylation on microfilament structure showed that TAT-HSP20-S16D mutant reduced F-actin filaments in cultured hASM cells (2) owing to profound and consistent disruption of F-actin similar to the effect of 10 μM cytochalasin D (2). Similarly, cultured 3T3 cells treated with FITC-labeled pHSP20 peptides and stained with phalloidin displayed disrupted stress fibers and a stellate morphology (12). Loss of stress fibers associated with loss of F-actin was confirmed by DNase I inhibition assay. 3T3 cells treated with 25 μM pHSP20 peptides showed a significant increase in G-actin content, similar to treatment with 10 μM forskolin (12). However, immunofluorescence analysis of recombinant HSP20 phosphomutant-transfected CSMC did not show any difference in actin cytoskeleton, indicating that HSP20 has no effect on the integrity of actin cytoskeleton in gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells. 16D-HSP20 overexpressing CSMC showed no disruption of F-actin and maintained intact cytoskeleton, indicating that the inhibition of contractile response exhibited by these CSMC is primarily due to effect of phospho-HSP20 on thin-filament-mediated regulation of contraction. Further investigation as to how phosphorylation of HSP20 alters phosphorylation of HSP27 will provide us a better insight into the transition between contractile and relaxant states of smooth muscle.

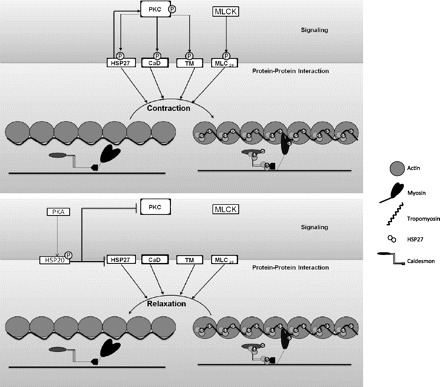

In summary, relaxation associated with phosphorylation of HSP20 proceeds through modulation of thin-filament-mediated regulation of contraction. Specifically, contractile functionality of TM, CaD and HSP27 is disrupted, which inhibits the interaction of actin with myosin. TM and CaD, both actin-binding proteins, are crucial for actin-myosin interaction and myosin ATPase activity. Contraction is associated with the phosphorylation of TM and CaD, which reduced the affinity of CaD for TM. The dissociation of CaD from TM is followed by displacement of TM on actin whereby myosin-binding sites are exposed for actomyosin interaction resulting in contraction. In a relaxation scenario, inhibition of phosphorylation of TM and CaD maintains their association, and conformational position thereby continues to block myosin-binding sites on actin. Therefore, in a relaxation milieu, there is an inhibition of actomyosin interaction and thus the termination of contraction. Whether the dephosphorylation of CaD and/or TM and/or HSP27 marks the end of the contraction cycle or the initiation of the relaxation cycle is not clear. We propose a model of thin-filament regulation of CSMC relaxation whereby dephosphorylation of HSP27 modulates the dissociation of CaD from TM, leading to inhibition of actomyosin interaction resulting in relaxation of colonic smooth muscle (Fig. 11). During the relaxed state, CaD is bound to TM, which is bound to actin, blocking the myosin-binding sites on actin. The net result is prevention of the interaction of actin with myosin, leading to relaxation of colonic smooth muscle. These data thus indicate that a balance between the kinase activities of PKC and PKA represents a molecular signaling switch for contraction and relaxation by modulating the phosphorylation state of HSP27 and HSP20. Furthermore, data suggest that phosphorylated HSP27/HSP20 regulates thin-filament dynamics by modulating the downstream molecular mechanical switch (TM).

Fig. 11.

Modulation of actomyosin interaction by molecular signaling switch. The model depicts the modulation of molecular signaling switch represented by balance between the kinase activities of PKC and PKA directing the contraction or relaxation of the CSMC. This molecular signaling switch (PKC and PKA) modulates the phosphorylation of HSP27 and HSP20. Furthermore, phosphorylated HSP27/HSP20 acts downstream on a molecular mechanical switch (TM) by regulating thin-filament dynamics. Top: contraction. Shifting of molecular signaling switch balance to PKC-α-mediated phosphorylation of HSP27 with subsequent PKC-α-mediated phosphorylation of CaD and TM results in contraction by exposure of myosin-binding sites on actin, leading to actomyosin interaction. Bottom: relaxation. Shifting of molecular signaling switch balance to PKA-mediated HSP20 phosphorylation results in relaxation by inhibiting PKC-α activation and inhibiting the subsequent HSP27 phosphorylation. This results in attenuation of subsequent downstream phosphorylation of CaD and TM such that myosin-binding sites on actin are unexposed, preventing actomyosin interaction. circled P, phosphorylation.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant NIDDK R01 DK57020.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Adam LP, Hathaway DR. Identification of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation sequences in mammalian h-Caldesmon. FEBS Lett 322: 56–60, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ba M, Singer CA, Tyagi M, Brophy C, Baker JE, Cremo C, Halayko A, Gerthoffer WT. HSP20 phosphorylation and airway smooth muscle relaxation. Cell Health Cytoskel 1: 27–42, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Batts TW, Walker JS, Murphy RA, Rembold CM. Absence of force suppression in rabbit bladder correlates with low expression of heat shock protein 20. BMC Physiol 5: 1–4, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beall A, Bagwell D, Woodrum D, Stoming TA, Kato K, Suzuki A, Rasmussen H, Brophy CM. The small heat shock-related protein, HSP20, is phosphorylated on serine 16 during cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation. J Biol Chem 274: 11344–11351, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beall AC, Kato K, Goldenring JR, Rasmussen H, Brophy CM. Cyclic nucleotide-dependent vasorelaxation is associated with the phosphorylation of a small heat shock-related protein. J Biol Chem 272: 11283–11287, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biancani P, Walsh J, Behar J. Vasoactive intestinal peptide: a neurotransmitter for relaxation of the rabbit internal anal sphincter. Gastroenterology 89: 867–874, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bitar KN. HSP27 phosphorylation and interaction with actin-myosin in smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G894–G903, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bitar KN, Zfass AM, Makhlouf GM. Interaction of acetylcholine and cholecystokinin with dispersed smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab Gastrointest Physiol 237: E172–E176, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brophy CM, Dickinson M, Woodrum D. Phosphorylation of the small heat shock-related protein, HSP20, in vascular smooth muscles is associated with changes in the macromolecular associations of HSP20. J Biol Chem 274: 6324–6329, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brozovich FV, Yamakawa M. Agonist activation modulates cross-bridge states in single vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C103–C108, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carvajal JA, Germain AM, Huidobro-Toro JP, Weiner CP. Molecular mechanism of cGMP-mediated smooth muscle relaxation. J Cell Physiol 184: 409–420, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dreiza CM, Brophy CM, Komalavilas P, Furnish EJ, Joshi L, Pallero MA, Murphy-Ullrich JE, von Rechenberg M, Ho YS, Richardson B, Xu N, Zhen Y, Peltier JM, Panitch A. Transducible heat shock protein 20 (HSP20) phosphopeptide alters cytoskeletal dynamics. FASEB J 19: 261–263, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eaton BL. Tropomyosin binding to F-actin induced by myosin heads. Science 192: 1337–1339, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Etter EF, Eto M, Wardle RL, Brautigan DL, Murphy RA. Activation of myosin light chain phosphatase in intact arterial smooth muscle during nitric oxide-induced relaxation. J Biol Chem 276: 34681–34685, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frobert O, Buus CL, Rembold CM. HSP20 phosphorylation and interstitial metabolites in hypoxia-induced dilation of swine coronary arteries. Acta Physiol Scand 184: 37–44, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuchs LC, Giulumian AD, Knoepp L, Pipkin W, Dickinson M, Hayles C, Brophy C. Stress causes decrease in vascular relaxation linked with altered phosphorylation of heat shock proteins. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R492–R498, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geeves MA, Holmes KC. Structural mechanism of muscle contraction. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 687–728, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerthoffer WT. Regulation of the contractile element of airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 261: L15–L28, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerthoffer WT, Murphy RA. Ca2+, myosin phosphorylation, and relaxation of arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 245: C271–C277, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gerthoffer WT, Pohl J. Caldesmon and calponin phosphorylation in regulation of smooth muscle contraction. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 1410–1414, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gilmont RR, Somara S, Bitar KN. VIP induces PKA-mediated rapid and sustained phosphorylation of HSP20. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 375: 552–556, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilmont RR, Somara S, Dhiraaj A, Bitar KN. Failure of myogenic relaxation in peristalsis: phosphorylation status of HSP20 modulates smooth muscle contraction/relaxation by regulating the cytoskeleton and RhoA. Gastroenterology (Abstact) 134: A542, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gong MC, Cohen P, Kitazawa T, Ikebe M, Masuo M, Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Myosin light chain phosphatase activities and the effects of phosphatase inhibitors in tonic and phasic smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 267: 14662–14668, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goyal RK, Rattan S, Said SI. VIP as a possible neurotransmitter of non-cholinergic, non-adrenergic inhibitory neurones. Nature 288: 378–380, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harnett KM, Biancani P. Calcium-dependent and calcium-independent contractions in smooth muscles. Am J Med 115, Suppl 3A: 24S–30S, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hedges JC, Oxhorn BC, Carty M, Adam LP, Yamboliev IA, Gerthoffer WT. Phosphorylation of caldesmon by ERK MAP kinases in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C718–C726, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang R, Li L, Guo H, Wang CL. Caldesmon binding to actin is regulated by calmodulin and phosphorylation via different mechanisms. Biochemistry 42: 2513–2523, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ibitayo AI, Groblewski G, Bitar KN. Ceramide induced phosphorylation of Hsp27 and modulation of its distribution within smooth muscle cells (Abstract). Gastroenterology 114: A769, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ibitayo AI, Sladick J, Tuteja S, Louis-Jacques O, Yamada H, Groblewski G, Welsh M, Bitar KN. HSP27 in signal transduction and association with contractile proteins in smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G445–G454, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jin JG, Murthy KS, Grider JR, Makhlouf GM. Activation of distinct cAMP- and cGMP-dependent pathways by relaxant agents in isolated gastric muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 264: G470–G477, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khatri JJ, Joyce KM, Brozovich FV, Fisher SA. Role of myosin phosphatase isoforms in cGMP-mediated smooth muscle relaxation. J Biol Chem 276: 37250–37257, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kilic H, Atalar E, Necla O, Ovunc K, Aksoyek S, Ozmen F. QT interval dispersion changes according to the vessel involved during percutaneous coronary angioplasty. J Natl Med Assoc 99: 914–916, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Komalavilas P, Penn RB, Flynn CR, Thresher J, Lopes LB, Furnish EJ, Guo M, Pallero MA, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Brophy CM. The small heat shock-related protein, HSP20, is a cAMP-dependent protein kinase substrate that is involved in airway smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L69–L78, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Landry J, Huot J. Modulation of actin dynamics during stress and physiological stimulation by a signaling pathway involving p38 MAP kinase and heat-shock protein 27. Biochem Cell Biol 73: 703–707, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marston S. How does genotype define phenotype? Microphysiology of a tropomyosin mutation in situ shows the limitations of reductionism. J Physiol 586: 2821, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marston S, El-Mezgueldi M. Role of tropomyosin in the regulation of contraction in smooth muscle. Adv Exp Med Biol 644: 110–123, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marston SB, Huber PAJ. Caldesmon. In: Biochemistry of Smooth Muscle Contraction, edited by Barany M, Barany K. San Diego, CA: Academic, 1996, p. 77–90 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marston SB, Redwood CS. The essential role of tropomyosin in cooperative regulation of smooth muscle thin filament activity by caldesmon. J Biol Chem 268: 12317–12320, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marston SB, Redwood CS. Inhibition of actin-tropomyosin activation of myosin MgATPase activity by the smooth muscle regulatory protein caldesmon. J Biol Chem 267: 16796–16800, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Meeks MK, Ripley ML, Jin Z, Rembold CM. Heat shock protein 20-mediated force suppression in forskolin-relaxed swine carotid artery. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C633–C639, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moreland S, Nishimura J, van Breemen C, Ahn HY, Moreland RS. Transient myosin phosphorylation at constant Ca2+ during agonist activation of permeabilized arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 263: C540–C544, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Murphy RA, Gerthoffer WT, Trevethick MA, Singer HA. Ca2+-dependent regulatory mechanisms in smooth muscle. Bibl Cardiol 38: 99–107, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murthy KS. Signaling for contraction and relaxation in smooth muscle of the gut. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 345–374, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murthy KS, Zhou H, Grider JR, Makhlouf GM. Inhibition of sustained smooth muscle contraction by PKA and PKG preferentially mediated by phosphorylation of RhoA. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284: G1006–G1016, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Connor MJ, Rembold CM. Heat-induced force suppression and HSP20 phosphorylation in swine carotid media. J Appl Physiol 93: 484–488, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ozaki H, Gerthoffer WT, Hori M, Karaki H, Sanders KM, Publicover NG. Ca2+ regulation of the contractile apparatus in canine gastric smooth muscle. J Physiol 460: 33–50, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patil SB, Pawar MD, Bitar KN. Phosphorylated HSP27 essential for acetylcholine-induced association of RhoA with PKCα. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 286: G635–G644, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pato MD, Tulloch AG, Walsh MP, Kerc E. Smooth muscle phosphatases: structure, regulation, and function. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 1427–1433, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rembold CM, Foster DB, Strauss JD, Wingard CJ, Eyk JE. cGMP-mediated phosphorylation of heat shock protein 20 may cause smooth muscle relaxation without myosin light chain dephosphorylation in swine carotid artery. J Physiol 524: 865–878, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salinthone S, Tyagi M, Gerthoffer WT. Small heat shock proteins in smooth muscle. Pharmacol Ther 119: 44–54, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Samizo K, Okagaki T, Kohama K. Inhibitory effect of phosphorylated myosin light chain kinase on the ATP-dependent actin-myosin interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 261: 95–99, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sen A, Chalovich JM. Caldesmon-actin-tropomyosin contains two types of binding sites for myosin S1. Biochemistry 37: 7526–7531, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Skorzewski R, Sliwinska M, Borys D, Sobieszek A, Moraczewska J. Effect of actin C-terminal modification on tropomyosin isoforms binding and thin filament regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794: 237–243, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sohn UD, Kim DK, Bonventre JV, Behar J, Biancani P. Role of 100-kDa cytosolic PLA2 in ACh-induced contraction of cat esophageal circular muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 267: G433–G441, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Somara S, Bitar KN. Phosphorylated HSP27 modulates the association of phosphorylated caldesmon with tropomyosin in colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G630–G639, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Somara S, Bitar KN. Tropomyosin interacts with phosphorylated HSP27 in agonist-induced contraction of smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1290–C1301, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Somara S, Gilmont RR, Bitar KN. Role of thin-filament regulatory proteins in relaxation of colonic smooth muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G958–G966, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Signal transduction and regulation in smooth muscle. Nature 372: 231–236, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Somlyo AP, Wu X, Walker LA, Somlyo AV. Pharmacomechanical coupling: the role of calcium, G-proteins, kinases and phosphatases. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 134: 201–234, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stull JT, Kamm KE, Krueger JK, Lin P, Luby-Phelps K, Zhi G. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent myosin light-chain kinases. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res 31: 141–150, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang P, Su X, Ibitayo AI, Bitar KN. Hsp27 phosphorylation regulates smooth muscle contraction through its interaction with tropomyosin (Abstract). Gastroenterology 116: A959, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Weigt C, Wegner A, Koch MH. Rate and mechanism of the assembly of tropomyosin with actin filaments. Biochemistry 30: 10700–10707, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Winder SJ, Allen BG, Fraser ED, Kang HM, Kargacin GJ, Walsh MP. Calponin phosphorylation in vitro and in intact muscle. Biochem J 296: 827–836, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Winder SJ, Walsh MP. Calponin: thin filament-linked regulation of smooth muscle contraction. Cell Signal 5: 677–686, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Woodrum D, Pipkin W, Tessier D, Komalavilas P, Brophy CM. Phosphorylation of the heat shock-related protein, HSP20, mediates cyclic nucleotide-dependent relaxation. J Vasc Surg 37: 874–881, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]