Abstract

Myocardial infarction (MI) results in significant metabolic derangement, causing accumulation of metabolic by product, such as homocysteine (Hcy). Hcy is a nonprotein amino acid generated during nucleic acid methylation and demethylation of methionine. Folic acid (FA) decreases Hcy levels by remethylating the Hcy to methionine, by 5-methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (5-MTHFR). Although clinical trials were inconclusive regarding the role of Hcy in MI, in animal models, the levels of 5-MTHFR were decreased, and FA mitigated the MI injury. We hypothesized that FA mitigated MI-induced injury, in part, by mitigating cardiac remodeling during chronic heart failure. Thus, MI was induced in 12-wk-old male C57BL/J mice by ligating the left anterior descending artery, and FA (0.03 g/l in drinking water) was administered for 4 wk after the surgery. Cardiac function was assessed by echocardiography and by a Millar pressure-volume catheter. The levels of Hcy-metabolizing enzymes, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 5-MTHFR, were estimated by Western blot analyses. The results suggest that FA administered post-MI significantly improved cardiac ejection fraction and induced tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, CBS, CSE, and 5-MTHFR. We showed that FA supplementation resulted in significant improvement of myocardial function after MI. The study eluted the importance of homocysteine (Hcy) metabolism and FA supplementation in cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: myocyte contractility, fractional shortening, ejection fraction

it has been found that plasma Hcy levels are elevated in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) (9). Furthermore, blood Hcy levels have been associated with the severity of the disease (27) and may represent a new risk factor or marker for CHF. Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy), an increase in blood Hcy level, appears to be associated not only with CHF but also with acute myocardial infarction (MI) (3). Previous studies have demonstrated that experimental moderate HHcy (total plasma Hcy concentration of 10–30 μM) causes endothelial dysfunction, including impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation (28).

Folic acid (FA) is a naturally occurring nutritional element that reduces Hcy levels by increasing the rate of recycling of Hcy to methionine (20). It decreases Hcy levels by remethylating Hcy to methionine by 5-methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (5-MTHFR). Although Hcy is converted to methionine by methionine synthase, 5-MTHFR is an important player in this process that catalyzes the conversion of Hcy to methionine by increasing remethylation of Hcy. The metabolism of folate and Hcy is interrelated, and increasing folate intake augments remethylation of Hcy, leading to a reduction of up to 25% in its plasma concentration, suggesting that treatment with FA may reduce cardiovascular risk by reducing Hcy (5, 7).

Recent studies indicated that FA, through its circulating form 5-MTHF, may have antioxidant properties and exert biological effects in vascular cells not directly related to changes in plasma Hcy level (1). A study (34) reports that, in rats, FA pretreatment blunts myocardial dysfunction during ischemia and ameliorates postreperfusion injury, in part, by high-energy phosphates. Interestingly, the metabolism of methionine to Hcy generates high-energy ATP through the S-adenosine homocysteine pathway. This suggests that FA mitigates HHcy and improves high-energy phosphates in acute ischemia-reperfusion injury. However, the protective role of FA in MI-induced CHF was unclear. We sought to test the hypothesis that FA treatment post-MI also exerts beneficial effects on cardiac function during CHF. We predicted that an ability of FA to improve arteriogenesis (47) may affect blood circulation by collateralization in the heart and thus improve myocyte function, leading to a general improvement in cardiac function.

METHODS

Animals.

The animals were fed standard chow and water ad libitum. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by an independent Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Louisville School of Medicine, in accord with animal care and use guidelines of the National Institutes of Health. Ten- to 14-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (65 mg kg ip). Animals were intubated and ventilated with room air using a positive-pressure respirator. A left thoracotomy was performed via the fourth intercostal space, and the lungs were retracted to expose the heart. After opening the pericardium, to create MI, the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was ligated with an 8–0 silk suture near its origin between the pulmonary outflow tract and the edge of the atrium. Ligation was deemed successful when the anterior wall of the left ventricle (LV) turned pale. The lungs were inflated by increasing positive end-expiratory pressure, and the thoracotomy side was closed in layers. Another group of mice underwent a sham surgery. They had a similar surgical procedure without tightening the suture around the coronary. The lungs were reexpanded, and the chest was closed. The animals were removed from the ventilator and allowed to recover on a heating pad. FA (0.03 g/l in drinking water) was administered for 4 wk after the surgery. The following experimental groups were used: 1) sham (animals underwent a mock surgery); 2) sham + FA (sham animals treated with FA); 3) MI (animals developed MI); and 4) MI + FA (animals with MI treated with FA). It is known that a dose of 2.5 mg/day leads to ingestion of 8.33 × 10−4 mg of FA (17, 44); therefore, we estimated that administration of 0.03 g/l FA in drinking water led to ingestion of 7.5 × 10−4 mg of FA.

Echocardiography analysis.

Two-dimensional (2-D) echocardiography was performed on mice before and after the surgery using a Hewlett-Packard Sono 5500 ultrasonograph with a 15-MHz transducer. The mice were sedated with 2,2,2-tribromethanol (TBE, T48 402; 240 mg/kg body wt; Sigma), and the chest was shaved. Mice were placed in a custom-made cradle on a heated platform in the supine or the left lateral decubitus position to facilitate echocardiography. For quantification of left ventricular (LV) dimensions and wall thickness, LV short- and long-axis loops and LV 2-D echocardiography image-guided M-mode traces at the level that yielded the largest diastolic dimension were digitally recorded. LV dimensions at diastole and systole (LVDd and LVDs, respectively) were measured from five cycles and averaged. Fractional shortening (FS) was calculated as [(LVDd − LVDs)/LVDd] × 100%. Fractional area change was derived from end-diastolic and end-systolic areas of short-axis loops. According to the single-plane Simpson's method, LV volumes at end-diastole and end-systole were derived from long-axis loops (38). Ejection fraction (EF) was calculated using values for end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV) as [(EDV − ESV)/EDV] × 100%.

Pressure-volume loop and Hcy measurements.

Using a standard Millar (Millar Instrument, Houston, TX) protocol, after performing a two-point calibration, steady-state pressure-volume loops were recorded followed by saline bolus and cuvette calibration for conversion of relative volume units to microliters. LV blood pressure and hemodynamic parameters were measured by a Millar catheter and analyzed by PVAN software (38). Plasma levels of Hcy were measured by HPLC.

Angiography.

Barium sulfate has been used as a good contrast for visualizing the gastrointestinal tract in the pediatric population. Barium sulfate is toxic if it enters the systemic circulation and is the reason why mostly iodinated contrasts are used for intravascular imaging. We used barium sulfate for postmortem imaging of mice vasculature (13). The size of barium particles range from 1 to 100 μm, whereas most of the mice microvasculature is <30 μm. Moreover, barium sulfate is insoluble in water. To overcome this problem, we dissolved barium sulfate in acidic pH buffer, and the mixture was used for intravascular infusion. All images were taken with the Kodak 4000 MM image station. Dissected animals were placed in the X-ray chamber, and angiogram images were captured with a high penetrative phosphorous screen by 31 KVP X-ray exposure for 3 min using a high-resolution phosphorous screen and aperture settings of ∼4.0, f-stop-12, and zoom of 40 mm.

Histology.

Hearts were collected from experimental animals and frozen for further analyses. Frozen heart were sectioned at 5 μm thickness with a cryostat (Leica Cryocut 1800; Leica Microsystems) and mounted on slides. Each slide was stained using a Masson's trichrome kit (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The heart muscle and vascular smooth muscle were stained a pink while the collagen was blue. The level of subcellular matrix collagen was assessed by measuring the optical density of blue color.

Isolation of mouse cardiac myocytes.

Mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated according to the method published earlier (35).

A mouse was first injected with heparin (1,000 U/kg body wt ip) and then anesthetized with TBE (240 mg/kg of body wt ip). The chest was wiped with 70% ethanol. A skin incision was made revealing the xiphoid process. The rib cage was completely cut starting at the xiphoid process running up the chest cavity. To avoid heart damage, the diaphragm was also cut. The heart was secured with forceps, and all vessels were cut. The aorta was cut so as to leave the maximal length for rapid cannulation. The dissected heart was immediately placed in a petri dish containing ice-cold calcium-free perfusion buffer (pH 7.4). To expose the aorta, all of the remnant excess tissue was removed and discarded. Holding the aorta with two fine forceps, it was slid on the vertically mounted cannula until the tip of the needle reached the aortic valve. The heart was secured on the needle with a small brass clip and was immediately perfused with perfusion buffer at a flow rate of 4.0 ml/min. The time from the heart dissection until the start of perfusion did not exceed 1 min.

The heart was perfused with perfusion buffer for 2 min or until the outflow from apex was cleared from blood. Next, the perfusion with digestion buffer consisting of 29 ml perfusion buffer and 1.0 ml 10 mg/ml Liberase Blendzyme 4 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was continued for 7–12 min. At the end of the perfusion, the tissue become soft, swollen, and light pink. After the perfusion, the heart was cut from the needle just below the atria using sterile fine scissors and was placed in a petri dish with 10 ml of incubation buffer [(in mM): 135 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 10 BDM, pH 7.4] at room temperature. The heart was cut in half, and the tissue was gently teased into small pieces with fine forceps. The obtained suspension of cardiomyocytes was gently pipetted up and down with a plastic pipette (2-mm tip) several times. Next, the cells were transferred to a 15-ml sterile polypropylene conical tube, and 10, 20, 30, 30, and 30 μl of a 100 mM CaCl2 solution were added at 5-min intervals. The final content of calcium was 1.2 mM. Isolated myocytes were maintained at room temperature in this incubation buffer.

Myocyte contractility analysis.

Cardiomyocyte contractility was controlled by electrical stimulation. Contractile properties of isolated ventricular myocytes were assessed by a video-based edge detection method as described (35). Steady-state twitches (8–10) were analyzed for cell length changes using the Soft-Edge software and averaged for each myocyte. Cell shortening and relengthening were assessed as a percent of peak shortening (PS), time to 90% of PS, time to 90% relengthening, and maximal velocities of shortening and relengthening (dL/dt).

Western Blot analysis.

Changes in protein content of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), 5-MTHFR, MMP-2 and -9, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, -2, -3, and -4 in MI were assessed by Western blot analysis (46). Briefly, frozen heart tissue was washed two times with ice-cold PBS and lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer (containing 5 mM of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), which was supplemented with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM) and protease inhibitor cocktail (1 ml/ml of lysis buffer). Protein content of the lysate was determined using the Bicinchronic Acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein (30 mg) were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane as described (29, 42). The blots were incubated with monoclonal anti-mouse respective antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the proteins on blots were detected as described (42). Membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. The blots were analyzed with Gel-Pro Analyzer software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) as described earlier (29). The protein expression intensity was assessed by integrated optical density (IOD) of the area of the band in the lane profile. To account for possible differences in the protein load, measurements presented are the IOD of each band under study (protein of interest) divided by the IOD of the respective β-actin band.

Confocal microscopy.

Isolated cardiomyocytes were washed two times with the incubation buffer. The cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. After fixation, cells were washed and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. After being washed, the myocytes were incubated with anti-TIMP-1, -2, -3, or -4, MMP-2, or MMP-9 antibodies (1:500 dilution, in 0.02% Tween 20/PBS) overnight at 4°C (Abcam). Cells were washed and goat anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:600 dilutions in PBS) was applied for 3 h at room temperature (Sigma). After additional washes with PBS, the cells were mounted on the glass slides. The images were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (×60 objective, FluoView 1000; Olympus). To enable the comparison of changes in fluorescence intensity, the images were acquired under the identical set of conditions. FITC fluorescence was imaged using excitation at 488 nm and emission 510–540 nm band pass filters. Myocyte images from four animals in each group were analyzed to determine expression of TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4, MMP-2, and MMP-9. Total fluorescence (green or red) intensity in five random fields (for each experiment) was measured with image analysis software (Image-Pro Plus; Media Cybernetics). Fluorescence intensity unit values for each experimental group were averaged.

Statistical analysis.

Values are reported as means ± SE. Differences between groups were tested by two-way ANOVA. If ANOVA indicated a significant difference (P < 0.05), Tukey's multiple-comparison test was used to compare group means and were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Gravimetric parameters.

LV catheterization and echocardiography were performed to evaluate in vivo cardiac function. Heart rate of animals did not change in any of experimental groups (Table 1). LV systolic blood pressure (LV-SBP) was less in MI mice after 4 wk of surgery compared with sham mice (Table 1). Treatment with FA increased SBP compared with that in MI mice, but it was still less than in the sham group. There was no difference in SBP in sham + FA and sham groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of end-systolic and end-diastolic blood pressure, EF, HR, and PV loop data in sham, MI, and sham and MI mice treated with FA

| HR | Maximum Volume, μl | Minimum Volume, μl | End-Systolic Volume, μl | End-Diastolic Volume, μl | Stroke Volume, μl | Cardiac Output, μl/min | End-Systolic Pressure, mmHg | End-Diastolic Pressure, mmHg | EF, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 603 ± 10 | 13 ± 2 | 6 ± 3 | 5.84 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 7.3 ± 4 | 4,432 ± 45 | 104 ± 0.67 | 11.3 ± 0.56 | 56 ± 4 |

| Sham + FA | 605 ± 12 | 12 ± 3 | 6 ± 2 | 5.82 ± 1 | 12 ± 4 | 6.5 ± 3 | 3,986 ± 29 | 105 ± 0.81 | 12.3 ± 1.23 | 58 ± 2 |

| MI | 610 ± 7* | 83 ± 9* | 65 ± 8* | 67.23 ± 12* | 83 ± 9* | 22.2 ± 2* | 13,572 ± 56* | 73 ± 1.07* | 20.7 ± 2* | 21 ± 3* |

| MI + FA | 605 ± 9*† | 51 ± 5*† | 28 ± 3*† | 32.94 ± 8*† | 50 ± 7*† | 18.1 ± 3*† | 10,992 ± 35*† | 85 ± 1.39*† | 18.6 ± 1.8*† | 42 ± 2*† |

Values are means ± SE; n = 3 mice for all groups. EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate; PV, pressure-volume; MI, myocardial infarction; FA, folic acid. P < 0.05 vs. sham group (*) and vs. MI (†).

The results of echocardiography measurements obtained immediately before and 4 wk after the surgery are shown in Table 2. All variables were similar in animals of all groups immediately before the surgery and remained unaltered in the sham group throughout the study period (Table 2). Supplementation with FA did not alter FS in sham mice (Table 2). Induction of MI resulted in a decrease of FS starting from 2 wk after surgery (Table 2). FS was minimal after 4 wk of surgery and was less than baseline after 2 wk of surgery or baseline in the MI group (Table 2). Similarly, FS was less after 2 wk of surgery than the baseline value in the MI + FA group and was greater than that after 4 wk of surgery (Table 2). However, FA supplementation improves FS in the MI + FA group compared with that in the MI group at each respective time point (2, 3, and 4 wk) after surgery (Table 2). The plasma concentration of Hcy in LAD-ligated animals was increased compared with the sham group. Interestingly, the treatment with FA mitigated the increase in Hcy levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of %FS and plasma Hcy levels in sham, MI, and sham and MI mice treated with FA

| Experimental Groups | Baseline, %FS | 2 Weeks, %FS | 3 Weeks, %FS | 4 Weeks, %FS | Hcy, μmol/l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | 59 | 60 | 62 | 58 | 9 ± 2.3 |

| MI | 61 | 35*† | 30*† | 24‡† | 56 ± 3.8* |

| Sham + FA | 58 | 60 | 61 | 57 | 7 ± 1.6 |

| MI + FA | 63 | 45*†§ | 43*†§ | 39‡§ | 25 ± 2.7§ |

Values for homocysteine (Hcy) are means ± SE; n = 9 for all groups. Presented results are calculated from the following equation [(LVDd − LVDs)/LVDd] × 100% where LVDs and LVDd are left ventricular dimensions at systole and diastole, respectively. P < 0.05 vs. sham and sham + FA (*), vs. respective baseline (before the surgery) (†), vs. respective after 2 wk of the surgery (‡), and vs. MI (§).

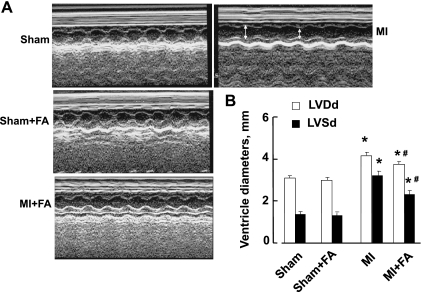

LV function.

LV dimensions (LVDd, LVDs) were increased in mice with MI compared with the sham group (Fig. 1). Supplementation with FA decreased LV dimensions in the MI + FA group compared with the MI group, although they were still lower than in sham animals (Fig. 1). Treatment with FA for 4 wk did not change LV dimensions in sham + FA compared with the sham group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Changes in left ventricle (LV), diastolic and systolic diameters (LVDd and LVDs, respectively) in sham-operated (sham), myocardial infarction-induced (MI), sham-operated and treated with folic acid (sham + FA), and myocardial infarction-induced and treated with folic acid (MI + FA) mice. The red arrow represents diameter in diastole; the white arrow represents diameter in systole. A: examples of M-mode echocardiograms obtained with 2-dimensional echocardiography from a short-axis midventrical view of hearts of the experimental animals. B: bar graphs of changes of LV diameters during diastole (LVDd) and systole (LVDs). Notice increased left ventricular cavity dimensions (LVDd and LVDs) in mice with MI. P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. MI (#); n = 9 animals for all groups.

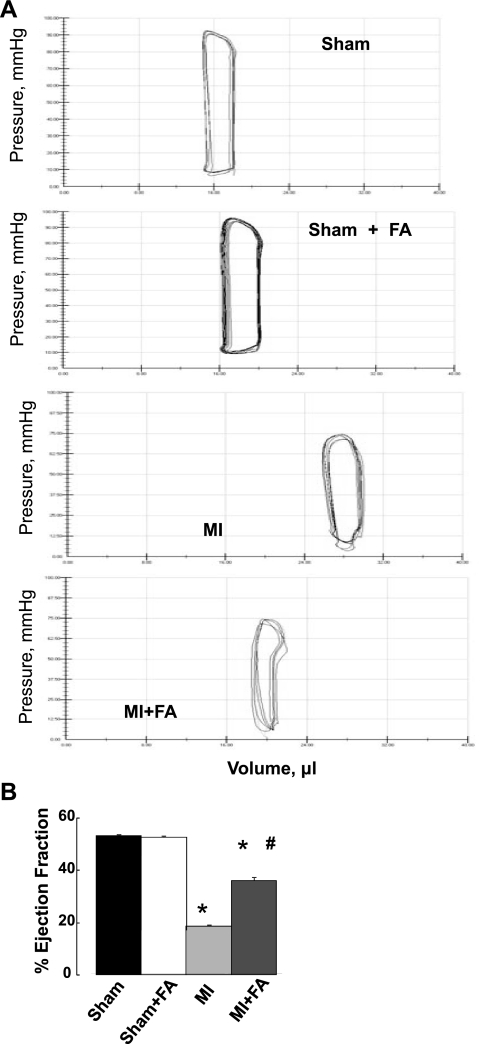

As shown in Fig. 2, invasive hemodynamic measurements showed a reduction in EF in MI vs. the sham group (Fig. 2). FA did not change EF in sham (sham + FA) animals (Fig. 2). However, supplementation with FA increased MI-induced lowering of EF in the MI + FA group, although it was still less than in sham animals (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Percent changes in ejection fraction (EF) in sham, MI, sham + FA, and MI + FA animals. A: examples of pressure-volume loops in experimental animals recorded after 4 wk of surgery. B: bar graphs of changes in EF, calculated from ventricles' volume {[(EDV − ESV)/EDV] × 100%, where EDV is end-diastolic volume and ESV is end-systolic volume}. P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. MI (#); n = 3 for all groups.

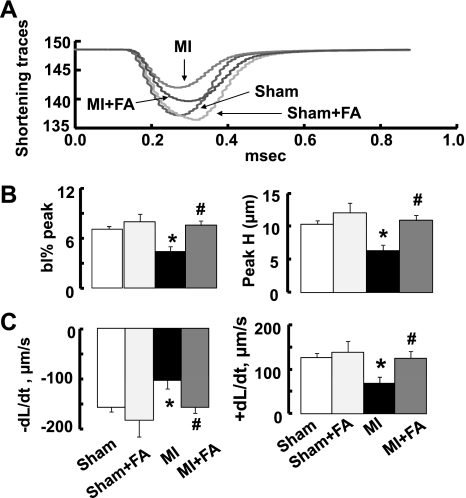

Myocyte function.

MI significantly impaired contractility of isolated cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3). FA supplementation produced at least a 30% increase in the percent shortening of myocyte contractility rate and the rate of myocyte relengthening ( ± dL/dt) (Fig. 3). These increases were enough to completely prevent MI-induced impaired contractility of myocytes and make it similar to that in the sham group (Fig. 3). Treatment with FA did not change myocyte contractility in sham + FA mice compared with the sham group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Myocyte contractility in sham, MI, sham + FA, and MI + FA animals. A: examples of cell shortening traces. B: changes in percent peak shortening presented as changes in baseline percent peak (bl% peak) and in peak height (Peak H). C: rates of contraction (+dL/dt) and relaxation (−dL/dt) of cardiomyocytes. The values are the means of measurements of at least five myocytes from each animal in each experimental group. The mean value of contractility was calculated from at least five contractions of each cardiomyocyte analyzed. P < 0.05 vs. the sham group (*) and vs. MI (#); n = 5 for all groups.

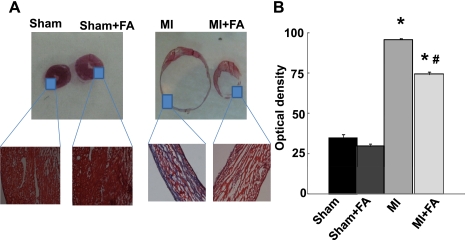

Histological analysis of collagen level in heart.

The intensity of trichrome blue stain demonstrated development of significant fibrotic formations in MI hearts compared with sham (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the treatment with FA mitigated the formation of fibrosis in the MI + FA group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Heart wall anatomical changes in sham, MI, sham + FA, and MI + FA animals. A: examples of cross-sectional view of the whole hearts at the ventricle level. Note: right and left ventricles are distinctly visible. Magnified areas are the left ventricular walls of sham and sham + FA hearts (left) and MI and MI + FA hearts (right). Note: No visible necroses were found in the left ventricular wall of hearts from sham and sham + FA. B: collagen-associated (blue) intensity changes in hearts from experimental animals. P < 0.05 vs. the sham group (*) and vs. MI (#); n = 4 for all groups.

Expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, and TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4.

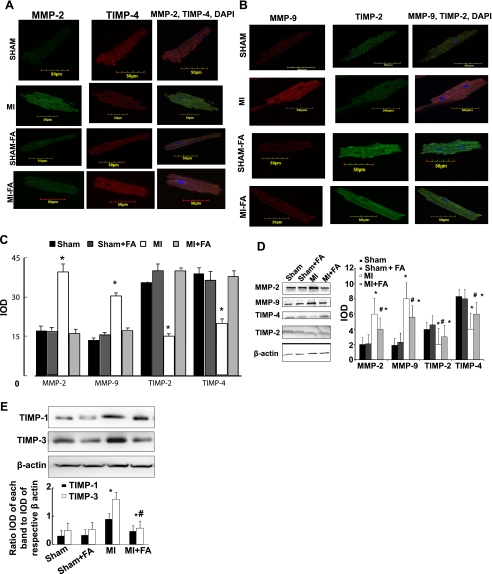

The confocal image analyses indicated induction of intracellular TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 expression in myocytes in MI hearts compared with sham (Fig. 5). Supplementation with FA completely abolished this effect in the MI + FA group (Fig. 5). Treatment of sham mice with FA (sham + FA) did not change the expression. MMP-2 and MMP-9 were increased in MI mice compared with the sham group (Fig. 5). Supplementation with FA normalized MMP-2 and MMP-9 production in mice with MI compared with that in mice with MI (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the levels of TIMP-1 and -3 were induced in MI, and treatment with FA mitigated this induction (Fig. 5E). Because the levels of MMP and TIMP were estimated by immunohistochemical staining, the method that is known as semiquantitative at best, we performed Western blot analysis on these samples. We found that the results obtained by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5D) were similar to those obtained by immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9, tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP)-2, and TIMP-4 in myocytes from sham, MI, sham + FA, and MI + FA mice. A: examples of images indicating expression of MMP-2 (green) and TIMP-4 (red). The last column indicates colocalization of MMP-2 and TIMP-4. B: examples of images indicating expression of MMP-9 (red) and TIMP-2 (green). The last column indicates colocalization of MMP-9 and TIMP-2. Cellular nuclei in all experiments were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The micrographs were taken under the identical set of conditions for all groups. C: bar graph of changes in integrated optical density (IOD) in expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-2, and TIMP-4 in myocytes. The micrographs were taken under the identical set of conditions for all groups. *P < 0.05 vs. sham, sham + FA, and MI + FA. D: Western blots and bar graphs of IOD changes in the levels of MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-2, and TIMP-4. P < 0.05 vs. sham, sham + FA, and MI + FA (*) vs. MI (#). Although we observed variations in the expression of various enzymes, i.e., MMPs and TIMPs, n = 6 in each group. E: Western blots and bar graphs of IOD changes in the levels of TIMP-1 and TIMP-3. P < 0.05 vs. sham, sham + FA, and MI + FA (*) and vs. MI (#); n = 6 for all groups.

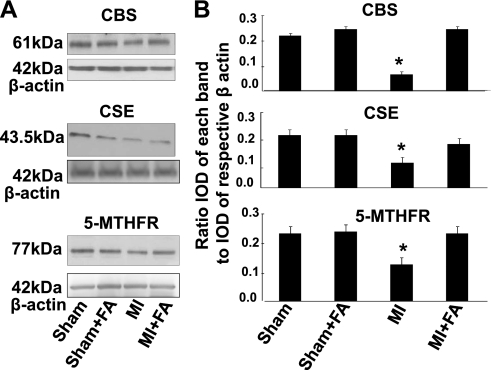

Hcy metabolism.

Because FA increases the level of 5-MTHFR and thus causes an increase in Hcy metabolism, we measured 5-MTHFR, CBS, and CSE (Hcy-metabolizing enzymes). Induction of MI significantly impaired expression of CBS, CSE, and 5-MTHFR in mice heart tissues (Fig. 6). Supplementation with FA restored expression of CBS, CSE, and 5-MTHFR in hearts from mice with MI (Fig. 6). Treatment with FA did not change the expression of CBS, CSE, and 5-MTHFR in sham + FA mice compared with that in the sham group (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Changes in expression of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) protein contents, by Western blot analysis, in hearts from sham, MI, sham + FA, and MI + FA mice. A: examples of Western blot images of the proteins studied and contents of β-actin in the respective samples. B: results of the Western blot analysis. Relative protein expression is reported as a ratio of IOD of each band to the IOD of the respective β-actin band. *P < 0.05 vs. sham, sham + FA, and MI + FA; n = 5 for all groups.

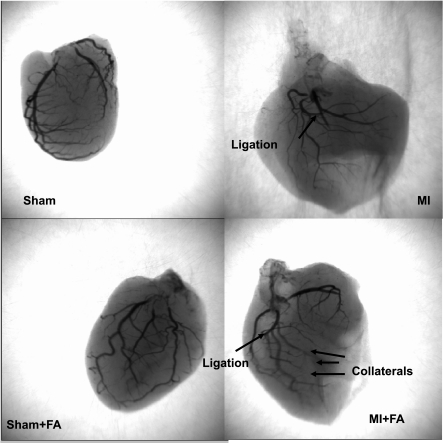

Collateralization.

The angiography data suggested an apparent increase in collateral vessels in the MI hearts after FA treatment (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Barium-contrast X-ray images of the hearts from sham, MI, sham + FA, and MI + FA. Note: there is an increase in collateral vessels in the MI heart after folic acid (FA) treatment compared with MI.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we showed that supplementation with FA at the time of MI limited the extent of MI development in mice. Our study indicated that the decrease in infarct size translated into reduced LV dilatation and improved LV function as measured by echocardiography and LV catheterization. Myocardial injury lowered LV pressure in MI mice, which was improved by FA supplementation. Several studies have indicated that FA and/or its active metabolite 5-MTHF improves endothelial function (10, 36, 49). Effects of FA have been studied in clinical trials (36), particularly to test its potential to lower cardiovascular risk in patients with myocardial vascular disease (3). Such effects may be mediated by the antioxidant properties of FA (10, 49) and are likely to mediate a rapid reduction in arterial stiffness through a reduction in the catabolism of nitric oxide and an enhancement of endothelial-dependent vasodilatation (52).

Postinfarct LV remodeling is a progressive process involving LV chamber dilatation, thinning of the infarcted wall, and compensatory thickening of the noninfarcted heart region (43). The time course of postinfarct LV dilatation can occur in acute, subacute, and later phases (50). Serial echocardiographic studies have shown that LV dilatation can be observed from as early as 2 wk and lasted 30 mo after MI, and the LV dilatation involved both infarcted and noninfarcted heart regions (16, 37). In the early phase of MI, infarct expansion and regional dilatation contribute to the ventricular enlargement (19, 26). Histological studies have revealed that infarct expansion is due to slippage between muscle bundles, most frequently occurs in transmural infarction (51), and is associated with rupture of the infarcted wall (40, 41). Cardiac rupture could be considered as an extreme form of infarct expansion in which the expanded zone is insufficient to maintain the integrity of the ventricular wall before the deposition of collagen and scar formation (23, 41). In the present study, 20% of infracted mice died of LV rupture, indicating development of a severe form of infarct. However, we found that, in the mice surviving rupture and acute heart failure, LV dimensions increased only modestly at wk 2 after induction of MI. Progressive ventricular dilatation was noted between 2 and 4 wk of observation. This enlargement of LV chamber was associated with lowering of LV-SBP during MI. Based on these results, we choose to observe changes in LV dimensions and cardiac functions after 2 and 4 wk of MI.

We have shown that FA decreases collagen accumulation in hypertensive hearts (32). Others have indicated that FA supplementation lowers collagen and scar formation (14). In this study, we showed that supplementation with FA lowered infarct size and increased FS and, in addition, lowered collagen and scar formation in MI. It is known that FA affects endothelial function and rapidly modulates arterial stiffness (4). This may explain the effect of FA causing an improvement in LV-SBP. A positive net effect of FA in improving the LV volume in our study can be explained by its effect of preventing changes in arteriolar stiffness (4, 24), leading to an improved arterial compliance and diminishing collagen formation in the heart (14, 29, 42).

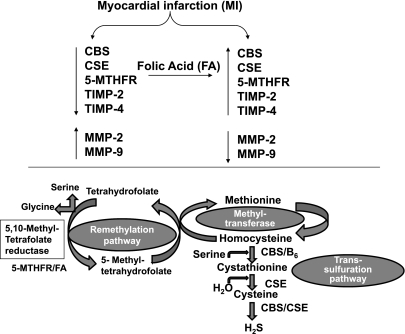

Hcy is either methylated to form methionine or undergoes transulfuration in its degradation (6). It occupies a branch point in methionine and cysteine metabolism (11). About one-half of the Hcy formed is conserved by remethylation to methionine in the “methionine cycle” (11). The other one-half is irreversibly converted by CBS and CSE to cysteine (11). Thus CBS is directly involved in the removal of Hcy from the methionine cycle and in the biosynthesis of cysteine (11). The most frequent cause of homocysteinuria is a homozygous deficiency of CBS, the first enzyme in the transulfuration pathway (22). 5-MTHFR reduces 5,10-methylenetetra-hydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, thus generating the active folate derivative required for methylation of Hcy to methionine (18). Mild HHcy can be caused by decreased intake of vitamins involved in the Hcy metabolism, such as FA. It is known that FA deranges transulfuration and remethylation pathways and lowers Hcy concentration in heart (Fig. 8). The present study indicated that MI-induced decreased expression of CBS, CSE, and 5-MTHFR was restored to their normal levels as a result of FA treatment. These results suggest that FA disrupts transulfuration and remethylation pathways and prevents or at least increases transformation of Hcy to methionine, thus inducing a decrease in total Hcy levels.

Fig. 8.

Schematic presentation of possible mechanism involved in FA-induced cardiac function protection during MI. MI caused decrease in CBS, CSE, MTHFR, TIMP-2, and TIMP-4, but it increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Treatment with FA, which induced expression of CBS, 5-MTHFR, and CSE, mitigated the abnormal extracellular matrix remodeling in MI hearts. The activation of CBS and CSE generated hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a most potent anti-oxidant and vasorelaxing agent that may counterbalance deteriorating effects caused by development of MI.

Previously, we and others have shown that FA mitigated the cardiac systolic and diastolic dysfunction (13, 25, 32). Here we demonstrated that FA mitigated myocyte dysfunction in MI. Because FA decreases Hcy levels, this mitigation may, in part, be due to the decrease in Hcy levels by FA. Interestingly, it is also known that FA increases the nitric oxide production (1) and may also contribute to improve myocyte function in MI. One of the functions of FA is that it behaves as a cofactor for MTHFR and therefore increases the activity of MTHFR to remethyl the Hcy to methionine. In addition, our data suggest that MI decreases the MTHFR level; the treatment with FA increases the expression of MTFHR (Fig. 6).

A differential role of MMP-2 vs. MMP-9 has been suggested (13, 15). Targeted detection of MMP-2 amplifies the cardiac failure (21, 31). On the other hand, MMP-9 deletion attenuates LV dilatation after experimental MI (8). Because of this effect on LV remodeling, it was not surprising to find an increased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 expression in the 4-wk MI mice hearts compared with that in sham and MI + FA mice. Thus an increase in MMP-9 may result in increased LV size. The data indicate that the level of MMPs was returned to its normal level in MI groups given FA supplementation.

TIMPs are a family of specific protein inhibitors of MMPs, four of which have been demonstrated (12). The data showed that end-stage heart failure, secondary to ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, is associated with the imbalance in MMP and TIMP expression at both the gene and protein syntheses levels. Myocardial MMP and TIMP are both localized in the interstitium and endocardium (48). It is known that TIMP-1 induces formation of fibrosis (48); TIMP-2 causes cell proliferation (30). TIMP-3 results in apoptosis (2). TIMP-4 acts specifically on cardiac tissue and induces apoptosis in transformed cells without affecting normal cells (45). We found an increase in TIMP-1 and -3 and a decrease in TIMP-2 and -4 in MI cardiomyocytes. Interestingly, the levels of TIMP-1, -2, -3, and -4 were restored in MI animals given FA supplementation, suggesting a direct effect of FA on expression of TIMPs.

In conclusion, we have found novel evidence for FA-induced improvement of myocardial function and reduced infarction during formation of MI. Our study showed that myocardial injury lowered LV-SBP in mice with MI, which was improved by FA supplementation. FA improved infarct size and LV dimensions (FS and LV volume). Treatment with FA restored cardiac myocyte contractility in mice with MI, indicating a direct functional impact of FA on heart. Thus our data suggest that FA supplementation restores expression of TIMPs and MMPs, normalizing the collagen production and preventing the heart wall thinning during development of MI.

Limitations.

It is tedious to measure epicardial blood flow in a beating heart by laser Doppler flow probe. To determine whether the in vivo effects of FA were mediated through effects on the cardiac myocytes rather than through the effects of FA on vascular function and collateral flow, we measured apparent vascular density by barium-contrast angiography (Fig. 7). The results suggested that, in vivo, effects of FA were also mediated, in part, through its effect on the collateral vessel density. We found an increase in collateral vessels in the MI + FA hearts compared with MI hearts (Fig. 7). This may equate to the improvement of blood flow in the epimyocardium post-FA treatment in MI hearts. However, the interpretation of improvement of collateral flow in the heart using barium-contrast angiography could be subjective because simple visualization of increased lighted small vessels in one heart does not necessarily mean that there is increased collateralization. We observed an apparent increase in vessel numbers in FA-treated hearts.

However, Figs. 1 and 2 showed the improvement of cardiac function in the MI + FA group, but still worse than in sham controls. However, in Fig. 3, the single cardiomyocyte contractility from MI + FA mice was completely restored compared with those from sham controls. This may suggest that, during endothelial myocyte coupling, myocyte interaction with endothelial cells is partially restored by FA treatment. However, we cannot prove directly that the changes in CBS, CSE, and 5-MTHFR levels are not consequences but the cause for the observed changes. It is known that FA increases the activity of MTHFR and therefore decreases, in part, the levels of Hcy and is responsible for the observed mitigation of cardiac dysfunction post-MI. Although treatment with folate had several effects, it is unclear which (if any) of these account for the differences in cardiac performance. It is known that FA decreases the Hcy level; therefore, our data may in part support the idea that these changes are in part functionally important. FA or its metabolite 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate has been shown to reduce superoxide production (36). In addition, 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate improves nitric oxide production and prevents superoxide generation via uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase by stabilizing tetrahydrobiopterin, a critical cofactor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, or by regenerating tetrahydrobiopterin from its inactive form dihydrobiopterin (1, 33). Previously, we demonstrated that FA ameliorates Hcy-induced oxidative stress (32). Here we demonstrate that FA mitigates the cardiac fibrosis and cardiomyocyte dysfunction in MI.

It has been previously reported that CBS is only present in the neurons and has a role in the brain. Although we did not perform confocal microscopy to trace the localization of this enzyme in cardiac myocytes, we show that it is present in the heart and may play a role in hydrogen sulfide (H2S) generation in the heart. The beneficial effect of FA supplementation could be because of H2S generation in the myocardium, since there is expression of both CSE and CBS enzymes restored in response to FA treatment. Therefore, the measurements on the levels of H2S would be very interesting. These experiments are in progress.

GRANTS

This study was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-71010, HL-74185, HL-88012 (to S. C. Tyagi), and HL-80394 (to D. Lominadze).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Warrick N, Cai S, de Bono J, Lee J, Leeson P, Neubauer S, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Refsum H, Channon KM. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate rapidly improves endothelial function and decreases superoxide production in human vessels: effects on vascular tetrahydrobiopterin availability and endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling. Circulation 114: 1193– 1201, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker AH, Zaltsman AB, George SJ, Newby AC. Divergent effects of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1, -2, or -3 overexpression on rat vascular smooth muscle cell invasion, proliferation, and death in vitro. TIMP-3 promotes apoptosis. J Clin Invest 101: 1478– 1487, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boushey A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid intakes. J Am Med Assoc 274: 1049–1057, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler GS, Apte SS, Willenbrock F, Murphy G. Human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 3 interacts with both the N- and C-terminal domains of gelatinases A and B. J Biol Chem 274: 10846– 10851, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carnicer RA, Navarro M, Arbonés-Mainar JM, Acín S, Guzmán MA, Surra JC, Arnal C, de las Heras M, Blanco-Vaca F, Osada J. Folic acid supplementation delays atherosclerotic lesion development in apoE-deficient mice. Life Sci 80: 638– 643, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao WH, Reynolds RD. Taurine-deficient diet up-regulated cystathionine β-synthase monoallele in hemizygous cystathionine β-synthase knockout mice. Nutr Res 29: 794– 801, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doshi SN, McDowell IFW, Moat SJ, Lang D, Newcombe RG, Kredan MB, Lewis MJ, Goodfellow J. Folate improves endothelial function in coronary artery disease: an effect mediated by reduction of intracellular superoxide? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 1196– 1202, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducharme A, Frantz S, Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Lindsey M, Rohde LE, Schoen FJ, Kelly RA, Werb Z, Libby P, Lee RT. Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 attenuates left ventricular enlargement and collagen accumulation after experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 106: 55– 62, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eikelboom JWM, Lonn EC, Genest J, Hankey G, Yusuf S. Homocyst(e)ine and cardiovascular disease: a critical review of the epidemiologic evidence. Ann Intern Med 131: 363– 375, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emi Nakano JAH, Hilary Powers J. Folate protects against oxidative modification of human LDL. Br J Nutr 86: 637– 633, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein JDMJ. Inactivation of betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase by adenosylmethionine and adenosylethionine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 118: 14– 19, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galis ZS, Sukhova GK, Lark MW, Libby P. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest 94: 2493– 2503, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Givvimani S, Tyagi N, Sen U, Mishra PK, Qipshidze N, Munjal C, Vacek JC, Abe OA, Tyagi SC. MMP-2/TIMP-2/TIMP-4 versus MMP-9/TIMP-3 in transition from compensatory hypertrophy and angiogenesis to decompensatory heart failure. Arch Physiol Biochem 116: 63– 72, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hautvast JGBM. Collagen metabolism in folic acid deficiency. Br J Nutr 32: 457– 469, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashidani STH, Ikeuchi M, Shiomi T, Matsusaka H, Kubota T, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Itoh T, Takeshita A. Targeted deletion of MMP-2 attenuates early LV rupture and late remodeling after experimental myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1229– H1235, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirayama A, Adachi T, Asada S, Mishima M, Nanto S, Kusuoka H, Yamamoto K, Matsumura Y, Hori M, Inoue M. Late reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction limits the dilatation of left ventricle without the reduction of infarct size. Circulation 88: 2565– 2574, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.House AA, Eliasziw M, Cattran DC, Churchill DN, Oliver MJ, Fine A, Dresser GK, Spence JD. Effect of B-vitamin therapy on progression of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Med Assoc 303: 1603– 1609, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L, Song XM, Zhu WL, Li Y. Plasma homocysteine and gene polymorphisms associated with the risk of hyperlipidemia in Northern Chinese subjects. Biomed Environ Sci 21: 514– 520, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Infarct expansion versus extension: two different complications of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 41: 1127– 1132, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kam S, Woo MDF, Chook P, Lolin YI, Sanderson JE, Metreweli C, Celermajer DS. Folic acid improves arterial endothelial function in adults with hyperhomocystinemia J Am Coll Cardiology 34: 2002– 2006, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kandalam V, Basu R, Abraham T, Wang X, Soloway PD, Jaworski DM, Oudit GY, Kassiri Z. TIMP2 deficiency accelerates adverse post-myocardial infarction remodeling because of enhanced MT1-MMP activity despite lack of MMP2 activation. Circ Res Mar 106: 796– 808, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluijtmans LAJ, Boers GHJ, Verbruggen B, Trijbels FJM, Novakova IRO, Blom HJ. Homozygous cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency, combined with factor V leiden or thermolabile methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in the risk of venous thrombosis. Blood 91: 2015– 2018, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar D, Jugdutt BI. Apoptosis and oxidants in the heart. J Lab Clin Med 142: 288– 297, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar M, Tyagi N, Moshal KS, Sen U, Kundu S, Mishra PK, Givvimani S, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine decreases blood flow to the brain due to vascular resistance in carotid artery. Neurochem Int 53: 214– 219, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar M, Tyagi N, Moshal KS, Sen U, Pushpakumar SB, Vacek T, Lominadze D, Tyagi SC. GABAA receptor agonist mitigates Hcy-induced cerebrovascular remodeling in knockout mice. Brain Res 1221: 147– 153, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamberts RR, Caldenhoven E, Lansink M, Witte G, Vaessen RJ, St Cyr JA, Stienen GJM. Preservation of diastolic function in monocrotaline-induced right ventricular hypertrophy in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1869– H1876, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lentz SR. Homocysteine and vascular dysfunction. Life Sci 61: 1205– 1215, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lentz SR, Erger RA, Dayal S, Maeda N, Malinow MR, Heistad DD, Faraci FM. Folate dependence of hyperhomocysteinemia and vascular dysfunction in cystathionine β-synthase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H970– H975, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lominadze D, Schuschke DA, Joshua IG, Dean WL. Increased ability of erythrocytes to aggregate in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens 24: 397– 406, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovelock JD, Baker AH, Gao F, Dong JF, Bergeron AL, McPheat W, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. Heterogeneous effects of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases on cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H461– H468, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsusaka H, Ikeuchi M, Matsushima S, Ide T, Kubota T, Feldman AM, Takeshita A, Sunagawa K, Tsutsui H. Selective disruption of MMP-2 gene exacerbates myocardial inflammation and dysfunction in mice with cytokine-induced cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1858– H1864, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller A, Mujumdar V, Palmer L, Bower JD, Tyagi SC. Reversal of endocardial endothelial dysfunction by folic acid in homocysteinemic hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 15: 157– 163, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moat SJ, Lang D, McDowell IF, Clarke ZL, Madhavan AK, Lewis MJ, Goodfellow J. Folate, homocysteine, endothelial function and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr Biochem 15: 64– 79, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moens AL, Champion HC, Claeys MJ, Tavazzi B, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Borgonjon DJ, Van Nassauw L, Haile A, Zviman M, Bedja D, Wuyts FL, Elsaesser RS, Cos P, Gabrielson KL, Lazzarino G, Paolocci N, Timmermans JP, Vrints CJ, Kass DA. High-dose folic acid pretreatment blunts cardiac dysfunction during ischemia coupled to maintenance of high-energy phosphates and reduces postreperfusion injury. Circulation 117: 1810– 1819, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moshal KS, Tipparaju S, Kumar M, Tyagi N, Metreveli N, Frank I, Tseng M, Tyagi SC. Mitochondrial matrix metalloproteinase activation decreases myocyte contractility in hyperhomocysteinemia, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H890– H897, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakano E, Higgins JA, Powers HJ. Folate protects against oxidative modification of human LDL. Br J Nutr 86: 637– 639, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norton GR, Veliotes DGA, Osadchii O, Woodiwiss AJ, Thomas DP. Susceptibility to systolic dysfunction in the myocardium from chronically infarcted spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H372– H378, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protocols 3: 1422– 1434, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 221– 233, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeffer M, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation 81: 1161– 1172, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuster E, Bulkley B. Expansion of transmural myocardial infarction: a pathophysiologic factor in cardiac rupture. Circulation 60: 1532– 1538, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sen U, Tyagi N, Patibandla PK, Dean WL, Tyagi SC, Roberts AM, Lominadze D. Fibrinogen-induced endothelin-1 production from endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C840– C847, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharpe CJ. Ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 70: 20C– 26C, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song Y, Cook NR, Albert CM, Denburgh MV, Manson JE. Effect of Hcy-lowering treatment with folic acid and B vitamins on risk of type 2 diabetes in women, a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes 58: 1921– 1928, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tummalapalli CM, Heath BJ, Tyagi SC. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-4 instigates apoptosis in transformed cardiac fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem 80: 512– 521, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tyagi N, Ovechkin AV, Lominadze D, Moshal KS, Tyagi SC. Mitochondrial mechanism of microvascular endothelial cells apoptosis in hyperhomocysteinemia. J Cell Biochem 98: 1150– 1162, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tyagi SC. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis: extracellular matrix remodeling in coronary collateral arteries and the ischemic heart. J Cell Biochem 65: 388– 394, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyagi SC, Meyer L, Schmaltz RA, Reddy HK, Voelker DJ. Proteinases and restenosis in the human coronary artery: extracellular matrix production exceeds the expression of proteolytic activity. Atherosclerosis 116: 43– 57, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verhaar MC, Wever RMF, Kastelein JJP, van Dam T, Koomans HA, Rabelink TJ. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate, the active form of folic acid, restores endothelial function in familial hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 97: 237– 241, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warren SERH, Markis JE, Grossman W, McKay RG. Time course of left ventricular dilation after myocardial infarction: influence of infarct-related artery and success of coronary thrombolysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 11: 12– 19, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weisman H, Bush D, Mannisi J, Weisfeldt M, Healy B. Cellular mechanisms of myocardial infarct expansion. Circulation 78: 186– 201, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkinson IB, MacCallum H, Cockcroft JR, Webb DJ. Inhibition of basal nitric oxide synthesis increases aortic augmentation index and pulse wave velocity in vivo. Br J Clin Pharmacol 53: 189– 192, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]