Abstract

Adenylyl cyclase (AC) is the principal effector molecule in the β-adrenergic receptor pathway. ACV and ACVI are the two predominant isoforms in mammalian cardiac myocytes. The disparate roles among AC isoforms in cardiac hypertrophy and progression to heart failure have been under intense investigation. Specifically, the salutary effects resulting from the disruption of ACV have been established in multiple models of cardiomyopathy. It has been proposed that a continual activation of ACV through elevated levels of protein kinase C could play an integral role in mediating a hypertrophic response leading to progressive heart failure. Elevated protein kinase C is a common finding in heart failure and was demonstrated in murine cardiomyopathy from cardiac-specific overexpression of Gαq protein. Here we assessed whether the disruption of ACV expression can improve cardiac function, limit electrophysiological remodeling, or improve survival in the Gαq mouse model of heart failure. We directly tested the effects of gene-targeted disruption of ACV in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of Gαq protein using multiple techniques to assess the survival, cardiac function, as well as structural and electrical remodeling. Surprisingly, in contrast to other models of cardiomyopathy, ACV disruption did not improve survival or cardiac function, limit cardiac chamber dilation, halt hypertrophy, or prevent electrical remodeling in Gαq transgenic mice. In conclusion, unlike other established models of cardiomyopathy, disrupting ACV expression in the Gαq mouse model is insufficient to overcome several parallel pathophysiological processes leading to progressive heart failure.

Keywords: protein kinase C, mouse cardiac myocyte, hypertrophy, action potential

the disparate roles among adenylyl cyclase (AC) isoforms in cardiac hypertrophy and progression to heart failure have been in focus for more than two decades. AC is the principal effector molecule along the β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) pathway, and six (ACII, ACIII, ACIV, ACV, ACVI, and ACVII) of nine known isoforms are endogenous to the mammalian heart (33). Among these six isoforms, ACV and ACVI are the two predominant proteins in cardiac myocytes. A number of shared characteristics exist between ACV and ACVI. They exhibit 65% amino acid homology (32) and are the only two AC isoforms that are inhibited by physiological Ca2+ concentrations (4, 16). Similar to other isoforms, ACV and ACVI are sensitive to negative feedback by protein kinase A (PKA) (2, 20). ACV and ACVI (as well as ACIII) have been found localized primarily in caveolin-rich domains in cardiac fibroblasts (33). Despite similarities, the evidence indicates distinct physiological roles for ACV and ACVI, as demonstrated in null-mutant mouse models of ACV vs. ACVI (25, 43, 44).

In a well-described transgenic mouse with cardiac-specific overexpression of the heterotrimeric G protein αq-subunit (Gαq), an overexpression of ACVI attenuates hypertrophy, prevents heart failure, and reduces mortality (40), whereas an overexpression of ACV does not (45). Moreover, the disruption of ACV activity in murine models of age-related (48), isoproterenol-induced (29, 48), or pressure-overload cardiomyopathy (30, 31, 48) has been associated with salubrious effects to the heart. Indeed, the proposed development of novel pharmaceuticals specifically inhibiting ACV as a potential therapy for chronic heart failure underscores the relevance of this isoform (14).

Heart failure is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality. Once cardiac failure develops, the condition is generally irreversible and is associated with a high mortality rate. Therefore, the molecular mechanisms that initiate or precipitate the transition to heart failure have undergone intense investigation, and there is evidence to suggest that an elevation in protein kinase C (PKC) activity (15, 17, 36, 42) may play an important role in the transition to heart failure. Specifically, increased PKC activity has been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy and progression to heart failure (6, 35).

Motivated by recent reports suggesting ACV inhibition as a possible therapeutic target in the treatment of heart failure, we directly tested whether the deletion of ACV would have beneficial effects in Gαq-associated cardiomyopathy using comprehensive in vivo and in vitro studies. Transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of Gαq provide a clinically relevant model of heart failure with chamber dilation, decreased cardiac contractility, electrical remodeling, depressed β-AR function, and a high mortality rate. Moreover, Gαq transgenic mice exhibit an elevation of PKC level, approximately threefold compared with transgene-negative siblings (8). Furthermore, PKC is directly activated along the Gαq signaling pathway. Hence, we reasoned that transgenic mice with a cardiac-specific overexpression of Gαq would provide an ideal means to specifically test the roles of ACV in the progression toward cardiac failure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal care and procedures were approved by the University of California, Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animal use was in accordance with National Institutes of Health and institutional guidelines.

Generation of ACV gene-targeted mice.

ACV knockout mice (ACV−/−) were generated as previously described (25, 44). The knockout mice were backcrossed with C57Bl/6J mice for greater than 10 generations. Two PCRs with primers specific for the mutated and wild-type alleles were used for genotype analysis. A previous study documented the absence of ACV mRNA expression in ACV−/− mouse hearts, which was associated with a significant decrease in cAMP production in left ventricular (LV) homogenates after isoproterenol stimulation (44).

Transgenic mice.

ACV−/− mice (C57Bl/6J) were crossbred with mice with cardiac-directed expression of Gαq protein (Gαq-40 mice; FVB/N, provided by G. W. Dorn II, University of Cincinnati) (5, 47). Of note, the Gαq transgenic mice were backcrossed onto C57Bl/6J mice for greater than 10 generations before they were used for the crossbreeding to allow for the direct comparison of these lines without the confounding effects from differences in the background. Four lines emanating from this cross were studied: Gαq/ACV−/− (double positive), Gαq alone, ACV−/− alone, and control (double negative). Transgene incorporation into mouse DNA was confirmed using the PCR of tail tissue.

Analysis of cardiac function by echocardiography.

M-mode measurements were used to assess systolic function as previously described (26). Measurements represent the average of twelve selected cardiac cycles from at least two separate scans performed in a random-blind manner with papillary muscles used as a point of reference to establish the consistency in level of the scan. End diastole was defined as the maximal LV diastolic dimension, and end systole was defined as the peak of posterior wall motion. Fractional shortening (FS), a measurement of systolic function, was calculated from LV dimensions as follows: FS = [(EDD − ESD)/EDD] × 100%, where EDD and ESD are LV end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions, respectively.

Western blot analysis.

Immunoblots were performed as previously described (49). Anti-β-myosin heavy chain antibody (NOQ7.5.4D, Sigma) was used at 1:10,000 dilution. This antibody was found to be specific for β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) through a screening of different commercially available antibodies. Anti-GAPDH antibody (Sigma) was used as an internal loading control.

Electrocardiograph recordings.

ECG recordings were obtained using Bioamplifier (BMA 831, CWE, Ardmore, PA). Mice were placed on a temperature-controlled warming blanket at 37°C. Four consecutive 2-min time frames of ECG data were obtained from each mouse. Signals were low-pass filtered at 0.2 kHz and digitized using Digidata 1200 (Axon Instruments). A total of 100 beats were analyzed from each animal in a blinded manner.

Electrophysiology recordings from transgenic animals.

Single ventricular myocytes were isolated from transgenic and double-negative (control) sibling mice from the same littermates at 8 to 9 mo of age. All experiments were performed using the conventional whole cell patch-clamp technique at room temperature.

For action potential recordings, patch pipettes were backfilled with amphotericin (200 μg/ml). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 120 K+ glutamate, 25 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, and 10 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.4 with KOH). The external solution contained (in mM) 138 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH).

For K+ current recording, the external solution contained 130 mM N-methylglucamine, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 μM nimodipine, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with HCl). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 140 KCl, 4 Mg-ATP, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 with KOH).

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. All experiments were performed using 3 M KCl agar bridges. Cell capacitance was calculated as the ratio of net charge (the integrated area under the current transient) to the magnitude of the pulse (20 mV). Currents were normalized to cell capacitance to obtain the current density. The series resistance was compensated electronically. In all experiments, a series resistance compensation of ≥90% was obtained. Currents were recorded using Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instrument), filtered at 2 kHz using a four-pole Bessel filter, and digitized at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz. Data analysis was carried out using custom-written software and commercially available PC-based spreadsheet and graphics software (MicroCal Origin, version 7.0).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from LV free wall of mice with five different genotypes: wild-type, Gαq, Gαq/ACV−/−, ACV−/−, and cardiac-directed ACVI overexpression (ACVI transgenic), using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Isolated RNA was subjected to DNase I (Invitrogen) treatment and subsequently to reverse transcription using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), dNTPs, and oligo dT primers. Parallel reactions without the reverse transcription enzyme were also performed and used as controls to rule out the possibility of genomic DNA contamination.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using Applied Biosystems Fast 7900HT real-time PCR system and RT2 Fast SYBR Green/ROX qPCR master mix reagent (SA Biosciences). qPCR-specific primers were custom made from SA Biosciences corresponding to mouse accession numbers: NM_001012765 for ACV, NM_007405 for ACVI, and NM_008084 for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The results were analyzed using Sequence Detection software (version 2.2.1). The quantity of ACV and ACVI transcripts were normalized to internal control GAPDH transcripts. qPCR was performed in triplicate to ensure quantitative accuracy.

Assessment of cAMP levels.

cAMP levels in cardiac tissues from Gαq, Gαq/ACV−/−, ACV−/−, and control mice were measured using cAMP XP Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The hearts were rapidly excised and retrogradely perfused through the cannulation of aorta using phosphate-buffered saline to remove blood from the cardiac tissue. The tissue was then snap frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Survival.

To compare the rates of survival between Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− groups, a Kaplan-Meier cumulative curve was used. A log-rank test calculated the statistical significance of differences between the two groups. The longevity of ACV−/− and double-negative control mice exceeded the duration of the experiment and were excluded from survival analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE where appropriate. An analysis of statistical significance was calculated using SigmaStat software. For multiple comparisons, one-way analysis of variance combined with Dunnett's test was used. The null hypothesis was rejected when P < 0.05 (two tailed).

RESULTS

ACV disruption does not prevent cardiac hypertrophy or chamber dilation in Gαq transgenic mice.

Figure 1A shows photomicrographs of examples of whole hearts from ACV−/−, Gαq, Gαq/ACV−/−, and control mice at 6 mo of age. As expected, Gαq transgenic mice exhibit evidence of cardiomyopathy with chamber dilatation. On the other hand, ACV−/− animals show normal chamber size compared with control mice. More importantly, in contrast to other models of heart failure, the deletion of ACV does not rescue the cardiomyopathic phenotype in Gαq transgenic animals. Figure 1B shows a significant increase in cell capacitance of LV myocytes isolated from both Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− animals compared with ACV−/− and control groups at 6 mo of age. Figure 1C displays summary data for the heart, liver, and lung weight, normalized to body weight, illustrating a significant increase in the heart weight-to-body weight ratio in both Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− animals compared with controls. Figure 1D illustrates the histologic sections with hematoxylin and eosin stain, comparing the four groups of animals. Both Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− hearts show dilatation of all four cardiac chambers.

Fig. 1.

Adenylyl cyclase type V (ACV) disruption does not prevent cardiomyopathy in Gαq transgenic mice. A: photomicrographs showing examples of hearts from 4 groups of animals. B: Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− transgenic mice show a significant increase in the cell capacity in single myocytes isolated from left ventricular free wall (*P < 0.05 compared with control; n = 9–17). C: heart, liver, and lung mass-to-body mass ratios in the 4 groups of animals. Disruption of ACV did not prevent the increase in heart mass-to-body mass ratio in the Gαq/ACV−/− transgenic mice (*P < 0.05 compared with control; n = 6–9 animals). D: histologic sections with hematoxylin-eosin staining from the same hearts as in A, providing direct evidence for dilated chambers in Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice. E: examples of M-mode ECG obtained from the 4 groups showing chamber dilatation and a decrease in cardiac contractility in Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice. F: Western blot analysis from 4 groups of animals showing expression of β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) in Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Same data were obtained from 3 different sets of animals. WT, wild-type. G: both Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice showed evidence of sinus bradycardia. Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice showed evidence of sinus bradycardia with significant prolongation of the R-R intervals compared with control mice. Summary data for R-R, P-R, and Q-T intervals (n = 6–8 animals for each group). Gαq/ACV−/− mice show a significant prolongation in the R-R interval (*P < 0.05 comparing Gαq/ACV−/− and control mice. R-R interval was not statistical different comparing Gαq/ACV−/− mice to Gαq mice).

Echocardiography was used to directly assess cardiac function in the four groups of animals. Figure 1E shows examples of M-mode echocardiogram displaying chamber dilatation and reduced FS in Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− transgenic mice. Summary data for the FS, ESD, and EDD are shown in Table 1. The disruption of ACV does not improve cardiac function in Gαq/ACV−/− transgenic mice.

Table 1.

Summary of echocardographic data in control, ACV−/−, Gαq, and Gαq/ACV−/− transgenic mice

| Control | Gαq | ACV−/− | Gαq/ACV−/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Systolic posterior wall thickness, mm | 1.5 ± 00.04 | 1.6 ± 00.09 | 1.5 ± 00.04 | 1.6 ± 00.08 |

| End-diastolic posterior wall thickness, mm | 1.1 ± 00.07 | 1.3 ± 00.08 | 1.1 ± 00.03 | 1.4 ± 00.1 |

| ESD, mm | 1.3 ± 00.01 | 1.9 ± 00.12* | 1.4 ± 00.07 | 1.8 ± 10.1* |

| EDD, mm | 2.6 ± 00.02 | 3.0 ± 00.11 | 2.8 ± 00.08 | 2.9 ± 00.12 |

| FS, % | 52.6 | 36.4* | 53.6 | 37.2* |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice. ACV, adenylyl cyclase type V; ESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; EDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; FS, fractional shortening, calculated from left ventricle dimensions as follows: FS = [(EDD − ESD)/EDD] × 100%.

P < 0.05 compared with control.

To further confirm the lack of the beneficial effects of ACV deletion in Gαq mice, we tested for the induction of a fetal gene, β-MHC isoform, a well-documented hypertrophic marker (3) using Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control. As expected, β-MHC is expressed only in Gαq transgenic mice but not in control or ACV−/− animals. Consistent with the functional analysis, Gαq/ACV−/− mice show a persistent expression of the β-MHC protein (Fig. 1F).

ACV disruption does not prevent sinus bradycardia in Gαq transgenic mice.

We have previously documented that cardiac-directed expression of Gαq protein resulted in sinus bradycardia (47). Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice show sinus bradycardia with a significant prolongation of the R-R intervals (*P < 0.05 compared with control animals, Fig. 1H). In contrast, ACV−/− mice demonstrate an increase in basal heart rates compared with control animals (*P < 0.05, Fig. 1G). There was no difference between Gαq and Gαq /ACV−/− animals.

Assessment of ACV and ACVI expression level in ACV and Gαq/ACV−/− mice.

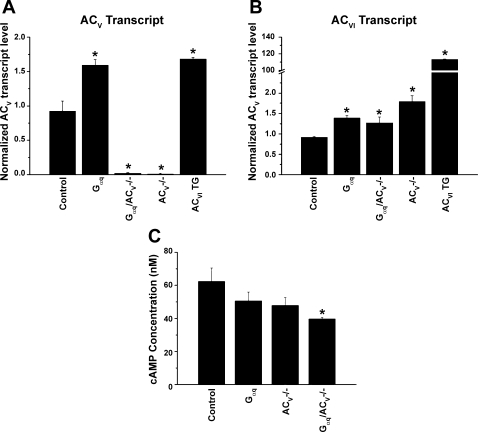

The absence of the beneficial effects from the deletion of ACV in Gαq-mediated cardiomyopathy compared with other previous published data in murine models of age-related (48), isoproterenol-induced (29, 48), or pressure-overload cardiomyopathy (30, 31, 48) has prompted us to examine the expression level of ACV in Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice (Fig. 2A). Moreover, to further ensure that ACV knockout animals are specific for ACV isoform, we directly assessed the transcript level of ACVI in ACV−/− and Gαq/ACV−/− mice (Fig. 2B). Previously described cardiac-directed overexpression of ACVI transgenic animals was used as a control for the assessment of the ACVI transcript. Figure 2A demonstrates that the ACV transcript is completely absent in ACV−/− and Gαq/ACV−/− animals as expected. Moreover, ACV and ACVI transcript levels are only slightly elevated (∼1.5-fold) in Gαq transgenic animals compared with controls (Fig. 2, A and B). The ACVI transcript level is also slightly elevated (∼1.8-fold) in ACV−/− animals, supporting the previous finding that the ACV knockout mouse is specific for the ACV isoform. The increase in the ACVI transcript level in ACV−/− animals may be secondary to compensatory responses in the knockout animals. Finally, as expected, the ACVI transcript level is significantly elevated (>110-fold) in ACVI transgenic animals compared with controls.

Fig. 2.

A and B: ACV and ACVI transcript levels normalized to GAPDH from control, Gαq, Gαq/ACV−/−, ACV−/−, and cardiac-directed expression of ACVI transgenic animals. *P < 0.05 compared with control animals. C: cAMP concentrations (in nM) in cardiac tissues from Gαq, Gαq/ACV−/−, and ACV−/− compared with control. *P ≤ 0.05 compared with control; n = 4 for each group.

Assessment of cAMP level in ACV and Gαq/ACV−/− mice.

We next examined the cAMP level in the cardiac tissues from four groups of animals (Fig. 2C). cAMP levels in Gαq or ACV−/− animals show a trend toward a decrease compared with control, but the differences are not statistically significant. On the other hand, Gαq/ACV−/− exhibits a significant decrease in cAMP level compared with control. The data support the notion that the disruption of ACV in Gαq transgenic animals results in a decrease in cAMP level without rescuing the cardiomyopathic phenotypes.

ACV disruption does not prevent electrical remodeling in Gαq transgenic mice.

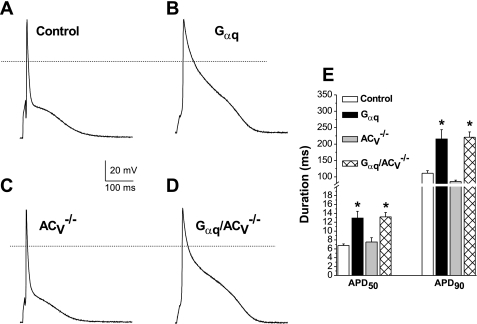

Previous studies have documented that Gαq-induced cardiomyopathy is associated with electrical remodeling with a prolongation of cardiac action potential (47). Here we tested whether the deletion of ACV may prevent electrical remodeling in Gαq transgenic animals. Figure 3, A–D, shows recordings of action potentials from cardiomyocytes isolated from LV free wall in each of the four groups. Action potentials at 50 and 90% of repolarization (APD50 and APD90, respectively) recorded from both the Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− groups demonstrate significant prolongation compared with those of control animals. However, there was no significant difference between the Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− groups.

Fig. 3.

ACV disruption does not prevent action potential (AP) prolongation in Gαq transgenic mice. A–D: examples of AP recordings from transgenic mice compared with control littermates. AP recordings from Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− transgenic mice were significantly prolonged compared with control littermates. There were no statistical differences in the length of APs between Gαq/ACV−/− and Gαq transgenic mice. E: summary data showing AP duration at 50 and 90% repolarization (APD50 and APD90, in ms). *P < 0.05 compared with control animals; n = 30 to 50 cells for each group.

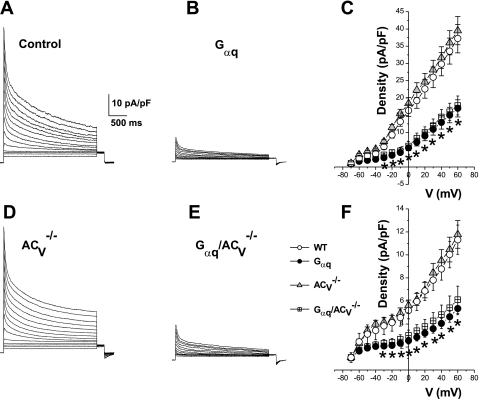

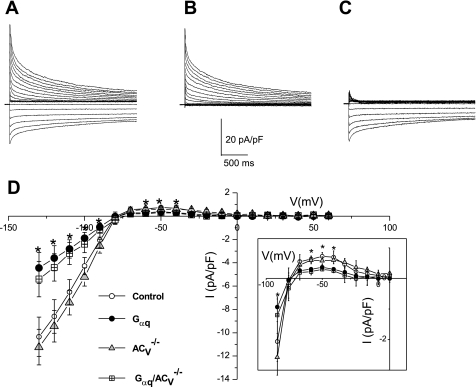

We have previously shown that cardiac action potential prolongation in Gαq transgenic animals results, at least in part, from a decrease in the outward K+ current and the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) and that the salubrious effects of ACVI overexpression in Gαq proteins transgenic mice are associated with the upregulation of both the outward K+ current and IK1 (47). Here we directly examined the effects of ACV disruption on the K+ current in the Gαq cardiomyopathy model. Figure 4, A–D, demonstrates examples of outward K+ current recorded from each of the four groups. The Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− groups show a significant decrease in the both the transient outward K+ current (Ito) and the sustained K+ current densities (Fig. 4, B and D). Summary data for Ito and the sustained K+ current densities are presented in Fig. 4, C and F, respectively. There was no difference between the recorded densities of Ito and the sustained outward K+ current from the Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− groups. Similarly, IK1 within the Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− groups were very similar and significantly smaller than the current densities in ACV−/− and control animals (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

ACV disruption does not prevent K+ current downregulation in Gαq transgenic mice. Ca2+-independent outward K+ current density from 4 different groups of animals (A, B, D, and E). Examples of current traces elicited from a holding potential of −80 mV using test potentials in duration of 2.5 s from −70 to +60 mV along 10-mV increments. C: summary data for the density of the peak outward components (*P < 0.05 comparing Gαq/ACV−/− and control mice; and *P < 0.05 comparing Gαq and control mice). F: summary data for the density of the sustained components (measured at the end of the pulse, *P < 0.05 comparing Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− with control mice; n = 12–16 cells for each group). V, voltage.

Fig. 5.

ACV disruption does not prevent the downregulation of the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) in Gαq transgenic mice. A: examples of current traces recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV using test potentials in duration of 2.5 s from −130 to +60 mV in 10-mV increments in control. B: after applying BaCl2. C: after applying the BaCl2-sensitive current. D: summary data for the BaCl2-sensitive current density (IK1 density) in single free wall LV myocytes isolated from the 4 groups. Inset: outward IK1 component from each group for further clarity (*P < 0.05; n = 8–15 for each group).

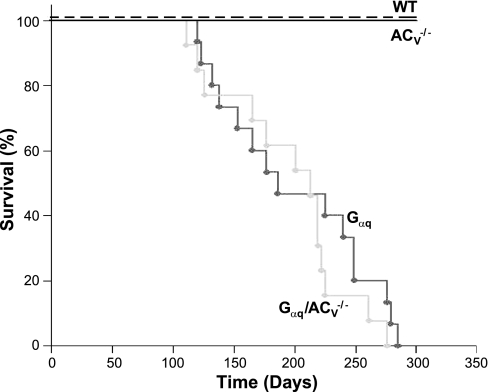

ACV disruption did not improve survival in Gαq transgenic mice.

Finally, Kaplan-Meier mortality analyses were performed comparing the Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− animals (Fig. 6). There were no significant differences in the survival between the two groups of animals, consistent with our data showing a lack of improvement in cardiomyopathy and electrical remodeling in Gαq transgenic animals by the disruption of ACV (P = 0.349).

Fig. 6.

Kaplan-Meier mortality curve in Gαq (n = 15) and Gαq/ACV−/− (n = 13) transgenic mice compared with WT and ACV−/− animals. Log-rank statistic calculated a P value for significant differences between the survival curves.

DISCUSSION

The present study directly tested the possible beneficial effects of gene-targeted disruption of ACV in transgenic mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of Gαq protein using multiple techniques to assess the survival, cardiac function, as well as structural and electrical remodeling. Our study provides new evidence that, in contrast to other models of cardiomyopathy, ACV disruption did not improve survival or cardiac function, limit cardiac chamber dilation, or prevent electrical remodeling in Gαq transgenic mice. Indeed, the findings are relevant and important in view of the proposed development of novel pharmaceuticals specifically inhibiting ACV as a potential therapy for chronic heart failure.

AC expression and its implications in cardiomyopathy.

The initially attractive idea of restoring cardiac contractility in heart failure by stimulating β-AR pathways has not been shown to reduce mortality. Indeed, the administration of dobutamine (23), a β1-AR agonist, or milrinone (34), a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, in clinical trials of patients with severe heart failure resulted in increases in mortality. Similarly, cardiac-directed expression of Gαs, β1-AR, or β2-AR proteins in murine models all demonstrate sustained increases in heart rate, decreased contractility, cardiomyopathy, and increased mortality (7, 9, 11, 21, 27, 39).

Remarkably, unlike the overexpression or stimulation of β-ARs, the overexpression of AC does not progress toward cardiac hypertrophy. The overexpression of ACVI prevents heart failure in the Gαq transgenic model (40) and, additionally, does not affect the basal heart rate or heart function compared with control animals (47). This rescue is associated with a restoration of heart function, the prevention of electrical remodeling, and a marked reduction in the mortality. The mechanisms underlying the observed beneficial effects remain unclear, but several proposals exist (37).

The increased expression of ACV, in contrast to ACVI, does not prevent cardiac hypertrophy in the Gαq-model of cardiomyopathy (45). ACV overexpression either slightly increases heart rate (46) in basal conditions or has no effects (10). On the other hand, the disruption of ACV has demonstrated benefits in several animals of cardiomyopathy. In the age-related model, older control mice have a greater disposition toward cardiomyocyte apoptosis, fibrosis, and decreased longevity compared with ACV knockout mice (48). Data taken from the pressure-overload model show that the LV ejection fraction (29, 30) improves in ACV knockout compared with control mice. Furthermore, this improvement is associated with reduced cardiac apoptosis in the ACV knockout compared with control mice (48). An ablation of ACV with a subsequent isoproterenol infusion results in an increased expression of Bcl-2, a suppressor of apoptosis in the Akt signaling pathway (31). Indeed, ACV has been viewed as a potential therapeutic target for chronic heart failure (14).

Our data indicate that the role of the ACV isoform may be diminished in Gαq-mediated cardiomyopathy compared with other animal models of heart failure. The beneficial effects associated with ACVI overexpression in the Gαq model cannot be explained by suppression of ACV because an absence of ACV did not rescue the phenotype. The reported beneficial effects from disrupting ACV expression were not present in our experiments, and this absence distinguishes Gαq overexpression from a set of cardiomyopathy models.

The absence of benefits from the deletion of ACV in Gαq-mediated cardiomyopathy prompted a closer examination of cardiomyopathy models. The models of cardiomyopathy can be arranged from pronounced to subtle salutary effects from ACV ablation as follows: isoproterenol induced, age related, pressure overload, and Gαq mediated. The disruption of ACV in isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy results in improved FS, decreased cardiac mass, and reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis compared with those in control mice (44). In age-related decline in LV diastolic function, disrupting ACV decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and transgenic mice lived 30% longer than sibling controls (50). Pressure-overloaded ACV−/− mice show less cardiomyocyte apoptosis than control animals (30), though the disruption of ACV in aortic banding does not prevent the progression to hypertrophy (48).

Administering isoproterenol to control mice produced a slight elevation of PKC expression; however, this effect was diminutive compared with PKA activation (36). Disrupting the PKA regulatory subunit-RIIβ in mice increases longevity and reduces body size, mirroring the beneficial effects of disrupting ACV in age-related cardiomyopathy (38). PKA attenuation has been suggested as part of a mechanism for the observed benefits of ACV disruption in age-related cardiomyopathy (50). Constitutively active PKCε parallels the progression to cardiomyopathy with age (13), but the intrinsic elevation of PKC has only been hypothesized in age-related cardiomyopathy. Elevated PKC activity in pressure overload has been reported (15, 17, 42), in particular, PKCα and PKCδ but not PKCε (1). Although the rising levels of catecholamine in the blood plasma (12, 41) are suggestive of downstream AC activation, PKA activation precedes hypertrophy in aortic banding and is not clearly linked with the development of hypertrophy (24). Overexpressing Gαq leads to a prominent elevation in PKC levels (particularly PKCα) (7). PKCα can stimulate ACV [isoforms ζ (22), α (18), and γ (18) interact with ACV], but our results show that cardiac hypertrophy manifests despite any possible interaction between PKC and ACV.

Outcomes of disrupting ACV in the Gαq transgenic model of cardiomyopathy.

Electrical remodeling is well documented in several models of heart failure including human heart failure. The downregulation of K+ channel expression is common to cardiac hypertrophy and failure and is associated with a prolonged action potential. A prolonged action potential, in turn, may be involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy through increasing intracellular Ca2+ entering mostly through L-type Ca2+ channels during the plateau phase. Our previous data demonstrate that the beneficial effects of ACVI overexpression in the Gαq transgenic model are associated with the prevention of electrical modeling of outward K+ current and IK1 (47). ACV deletion, however, does not reproduce these beneficial effects in the Gαq transgenic model; outward K+ current and IK1 remain unchanged between Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice. The two groups of animals, Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/−, displayed a similar prolongation of the action potentials and sinus bradycardia. The mechanisms of increase mortality in Gαq and Gαq/ACV−/− mice may be related to the documented prolongation in APD and possibly brady- or tachyarrhythmias. However, other mechanisms may be involved including progressive heart failure.

Interestingly, the ACV−/− group shows a slight, but statistically significant, decrease in R-R interval compared with the control animals. A minor deviation in heart rates in ACV−/− mice compared with the control animals has previously been reported (28, 29, 43). A decreasing effect of acetylcholine receptors in ACV−/− mice compared with control mice was proposed to explain this deviation (28). The activation of the parasympathetic system as an explanation for heart rate deviations between ACV−/− and control mice appears reasonable since acetylcholine receptors have been found to be colocalized with AC in macromolecular complexes in cardiomyocytes (19).

Conclusion.

Our results demonstrate that unlike in age-related, isoproterenol-induced, and pressure-overload models, a disruption of ACV in the Gαq transgenic model provides no benefits in preventing the development of cardiomyopathy. The disruption of the constant activation of ACV by PKC in Gαq transgenic mouse model may be insufficient to overcome several parallel pathophysiological processes leading to progressive heart failure.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grants HL-85727 and HL-85844 and a Veterans Affairs merit review grant (to N. Chiamvimonvat); NHLBI Grants P01-HL-66941, HL-81741, and HL-88426 and a Veterans Affairs merit review grant (to H. K. Hammond); American Heart Association Western Affiliates beginning grant-in-aid (to T. Tang); and American Heart Association Western Affiliates postdoctoral fellowship award (to H. Qiu).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. E. N. Yamoah for helpful suggestions and comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braun MU, LaRosee P, Schon S, Borst MM, Strasser RH. Differential regulation of cardiac protein kinase C isozyme expression after aortic banding in rat. Cardiovasc Res 56: 52– 63, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Harry A, Li J, Smit MJ, Bai X, Magnusson R, Pieroni JP, Weng G, Iyengar R. Adenylyl cyclase 6 is selectively regulated by protein kinase A phosphorylation in a region involved in Galphas stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14100– 14104, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien KR, Knowlton KU, Zhu H, Chien S. Regulation of cardiac gene expression during myocardial growth and hypertrophy: molecular studies of an adaptive physiologic response. FASEB J 5: 3037– 3046, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper DM. Molecular and cellular requirements for the regulation of adenylate cyclases by calcium. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 912– 915, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Angelo DD, Sakata Y, Lorenz JN, Boivin GP, Walsh RA, Liggett SB, Dorn GW., 2nd Transgenic Gαq overexpression induces cardiac contractile failure in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 8121– 8126, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorn GW, 2nd, Force T. Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 115: 527– 537, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn GW, 2nd, Tepe NM, Lorenz JN, Koch WJ, Liggett SB. Low- and high-level transgenic expression of beta2-adrenergic receptors differentially affect cardiac hypertrophy and function in Gαq-overexpressing mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6400– 6405, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn GW, 2nd, Tepe NM, Wu G, Yatani A, Liggett SB. Mechanisms of impaired beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in Gαq-mediated cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular dysfunction. Mol Pharmacol 57: 278– 287, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelhardt S, Hein L, Wiesmann F, Lohse MJ. Progressive hypertrophy and heart failure in beta1-adrenergic receptor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7059– 7064, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito G, Perrino C, Ozaki T, Takaoka H, Defer N, Petretta MP, De Angelis MC, Mao L, Hanoune J, Rockman HA, Chiariello M. Increased myocardial contractility and enhanced exercise function in transgenic mice overexpressing either adenylyl cyclase 5 or 8. Basic Res Cardiol 103: 22– 30, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman K, Lerman I, Kranias EG, Bohlmeyer T, Bristow MR, Lefkowitz RJ, Iaccarino G, Koch WJ, Leinwand LA. Alterations in cardiac adrenergic signaling and calcium cycling differentially affect the progression of cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 107: 967– 974, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganguly PK, Lee SL, Beamish RE, Dhalla NS. Altered sympathetic system and adrenoceptors during the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Am Heart J 118: 520– 525, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldspink PH, Montgomery DE, Walker LA, Urboniene D, McKinney RD, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM. Protein kinase Cepsilon overexpression alters myofilament properties and composition during the progression of heart failure. Circ Res 95: 424– 432, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottle M, Geduhn J, Konig B, Gille A, Hocherl K, Seifert R. Characterization of mouse heart adenylyl cyclase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329: 1156– 1165, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu X, Bishop SP. Increased protein kinase C and isozyme redistribution in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res 75: 926– 931, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillou JL, Nakata H, Cooper DM. Inhibition by calcium of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. J Biol Chem 274: 35539– 35545, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamplová B, Novák F, Kolár F, Nováková O. Transient upregulation of protein kinase C in pressure-overloaded neonatal rat myocardium. Physiol Res 59: 25– 33, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanoune J, Defer N. Regulation and role of adenylyl cyclase isoforms. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41: 145– 174, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Head BP, Patel HH, Roth DM, Lai NC, Niesman IR, Farquhar MG, Insel PA. G-protein-coupled receptor signaling components localize in both sarcolemmal and intracellular caveolin-3-associated microdomains in adult cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 280: 31036– 31044, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwami G, Kawabe J, Ebina T, Cannon PJ, Homcy CJ, Ishikawa Y. Regulation of adenylyl cyclase by protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 270: 12481– 12484, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwase M, Uechi M, Vatner DE, Asai K, Shannon RP, Kudej RK, Wagner TE, Wight DC, Patrick TA, Ishikawa Y, Homcy CJ, Vatner SF. Cardiomyopathy induced by cardiac Gsα overexpression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H585– H589, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawabe J, Iwami G, Ebina T, Ohno S, Katada T, Ueda Y, Homcy CJ, Ishikawa Y. Differential activation of adenylyl cyclase by protein kinase C isoenzymes. J Biol Chem 269: 16554– 16558, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krell MJ, Kline EM, Bates ER, Hodgson JM, Dilworth LR, Laufer N, Vogel RA, Pitt B. Intermittent, ambulatory dobutamine infusions in patients with severe congestive heart failure. Am Heart J 112: 787– 791, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavandero S, Cartagena G, Guarda E, Corbalan R, Godoy I, Sapag-Hagar M, Jalil JE. Changes in cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase and active stiffness in the rat volume overload model of heart hypertrophy. Cardiovasc Res 27: 1634– 1638, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee KW, Hong JH, Choi IY, Che Y, Lee JK, Yang SD, Song CW, Kang HS, Lee JH, Noh JS, Shin HS, Han PL. Impaired D2 dopamine receptor function in mice lacking type 5 adenylyl cyclase. J Neurosci 22: 7931– 7940, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li N, Timofeyev V, Tuteja D, Xu D, Lu L, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Singapuri A, Albert TR, Rajagopal AV, Bond CT, Periasamy M, Adelman J, Chiamvimonvat N. Ablation of a Ca2+-activated K+ channel (SK2 channel) results in action potential prolongation in atrial myocytes and atrial fibrillation. J Physiol 587: 1087– 1100, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liggett SB, Tepe NM, Lorenz JN, Canning AM, Jantz TD, Mitarai S, Yatani A, Dorn GW., 2nd Early and delayed consequences of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor overexpression in mouse hearts: critical role for expression level. Circulation 101: 1707– 1714, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okumura S, Kawabe J, Yatani A, Takagi G, Lee MC, Hong C, Liu J, Takagi I, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Ishikawa Y. Type 5 adenylyl cyclase disruption alters not only sympathetic but also parasympathetic and calcium-mediated cardiac regulation. Circ Res 93: 364– 371, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okumura S, Suzuki S, Ishikawa Y. New aspects for the treatment of cardiac diseases based on the diversity of functional controls on cardiac muscles: effects of targeted disruption of the type 5 adenylyl cyclase gene. J Pharm Sci 109: 354– 359, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura S, Takagi G, Kawabe J, Yang G, Lee MC, Hong C, Liu J, Vatner DE, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF, Ishikawa Y. Disruption of type 5 adenylyl cyclase gene preserves cardiac function against pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 9986– 9990, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okumura S, Vatner DE, Kurotani R, Bai Y, Gao S, Yuan Z, Iwatsubo K, Ulucan C, Kawabe J, Ghosh K, Vatner SF, Ishikawa Y. Disruption of type 5 adenylyl cyclase enhances desensitization of cyclic adenosine monophosphate signal and increases Akt signal with chronic catecholamine stress. Circulation 116: 1776– 1783, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostrom RS, Liu X, Head BP, Gregorian C, Seasholtz TM, Insel PA. Localization of adenylyl cyclase isoforms and G protein-coupled receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells: expression in caveolin-rich and noncaveolin domains. Mol Pharmacol 62: 983– 992, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostrom RS, Naugle JE, Hase M, Gregorian C, Swaney JS, Insel PA, Brunton LL, Meszaros JG. Angiotensin II enhances adenylyl cyclase signaling via Ca2+/calmodulin. Gq-Gs cross-talk regulates collagen production in cardiac fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 278: 24461– 24468, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Packer M, Carver JR, Rodeheffer RJ, Ivanhoe RJ, DiBianco R, Zeldis SM, Hendrix GH, Bommer WJ, Elkayam U, Kukin ML, Mallis GI, Sollano JA, Shannon J, Tandon PK, DeMets DL, the PROMISE Study Research Group Effect of oral milrinone on mortality in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 325: 1468– 1475, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palaniyandi SS, Sun L, Ferreira JC, Mochly-Rosen D. Protein kinase C in heart failure: a therapeutic target? Cardiovasc Res 82: 229– 239, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palfi A, Bartha E, Copf L, Mark L, Gallyas F, Jr, Veres B, Kalman E, Pajor L, Toth K, Ohmacht R, Sumegi B. Alcohol-free red wine inhibits isoproterenol-induced cardiac remodeling in rats by the regulation of Akt1 and protein kinase C alpha/beta II. J Nutr Biochem 20: 418– 425, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phan HM, Gao MH, Lai NC, Tang T, Hammond HK. New signaling pathways associated with increased cardiac adenylyl cyclase 6 expression: implications for possible congestive heart failure therapy. Trends Cardiovasc Med 17: 215– 221, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piddo AM, Sanchez MI, Sapag-Hagar M, Corbalan R, Foncea R, Ebensperger R, Godoy I, Melendez J, Jalil JE, Lavandero S. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and mechanical heart function in ventricular hypertrophy induced by pressure overload or secondary to myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 28: 1073– 1083, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rockman HA, Chien KR, Choi DJ, Iaccarino G, Hunter JJ, Ross J, Jr, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Expression of a beta-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 inhibitor prevents the development of myocardial failure in gene-targeted mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7000– 7005, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roth DM, Bayat H, Drumm JD, Gao MH, Swaney JS, Ander A, Hammond HK. Adenylyl cyclase increases survival in cardiomyopathy. Circulation 105: 1989– 1994, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siri FM. Sympathetic changes during development of cardiac hypertrophy in aortic-constricted rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 255: H452– H457, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi T, Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, Maekawa Y, Mahara K, Iwata M, Hammond HK, Ogawa S. Angiotensin receptor blockade improves myocardial beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in postinfarction left ventricular remodeling: a possible link between beta-adrenergic receptor kinase-1 and protein kinase C epsilon isoform. J Am Coll Cardiol 43: 125– 132, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang T, Gao MH, Lai NC, Firth AL, Takahashi T, Guo T, Yuan JX, Roth DM, Hammond HK. Adenylyl cyclase type 6 deletion decreases left ventricular function via impaired calcium handling. Circulation 117: 61– 69, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang T, Lai NC, Roth DM, Drumm J, Guo T, Lee KW, Han PL, Dalton N, Gao MH. Adenylyl cyclase type V deletion increases basal left ventricular function and reduces left ventricular contractile responsiveness to beta-adrenergic stimulation. Basic Res Cardiol 101: 117– 126, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tepe NM, Liggett SB. Transgenic replacement of type V adenylyl cyclase identifies a critical mechanism of beta-adrenergic receptor dysfunction in the G alpha q overexpressing mouse. FEBS Lett 458: 236– 240, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tepe NM, Lorenz JN, Yatani A, Dash R, Kranias EG, Dorn GW, 2nd, Liggett SB. Altering the receptor-effector ratio by transgenic overexpression of type V adenylyl cyclase: enhanced basal catalytic activity and function without increased cardiomyocyte beta-adrenergic signalling. Biochemistry 38: 16706– 16713, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Timofeyev V, He Y, Tuteja D, Zhang Q, Roth DM, Hammond HK, Chiamvimonvat N. Cardiac-directed expression of adenylyl cyclase reverses electrical remodeling in cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 170– 181, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vatner SF, Yan L, Ishikawa Y, Vatner DE, Sadoshima J. Adenylyl cyclase type 5 disruption prolongs longevity and protects the heart against stress. CIRC J 73: 195– 200, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Y, Zhang Z, Timofeyev V, Sharma D, Xu D, Tuteja D, Dong PH, Ahmmed GU, Ji Y, Shull GE, Periasamy M, Chiamvimonvat N. The effects of intracellular Ca2+ on cardiac K+ channel expression and activity: novel insights from genetically altered mice. J Physiol 562: 745– 758, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan L, Vatner DE, O'Connor JP, Ivessa A, Ge H, Chen W, Hirotani S, Ishikawa Y, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. Type 5 adenylyl cyclase disruption increases longevity and protects against stress. Cell 130: 247– 258, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]