Abstract

The systemic vasculature exhibits attenuated vasoconstriction following hypobaric chronic hypoxia (CH) that is associated with endothelium-dependent vascular smooth muscle (VSM) cell hyperpolarization. We hypothesized that increased activity of endothelial cell (EC) large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels contributes to this response. Gracilis resistance arteries from hypobaric CH (barometric pressure = 380 mmHg for 48 h) rats demonstrated reduced myogenic reactivity and hyperpolarized VSM membrane potential (Em) compared with controls under normoxic ex vivo conditions. These differences were eliminated by endothelial disruption. In the presence of cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase inhibition, combined intraluminal administration of the intermediate and small-conductance, calcium-activated K+ channel blockers TRAM-34 and apamin was without effect on myogenic responsiveness and VSM Em in both groups; however, these variables were normalized in CH arteries by intraluminal administration of the BKCa inhibitor iberiotoxin (IBTX). Basal EC Em was hyperpolarized in arteries from CH rats compared with controls and was restored by IBTX, but not by TRAM-34/apamin. K+ channel blockers were without effect on EC basal Em in controls. Similarly, IBTX blocked acetylcholine-induced dilation in arteries from CH rats, but was without effect in controls, whereas TRAM-34/apamin eliminated dilation in controls. Acetylcholine-induced EC hyperpolarization and calcium responses were inhibited by IBTX in CH arteries and by TRAM-34/apamin in controls. Patch-clamp experiments on freshly isolated ECs demonstrated greater K+ current in cells from CH rats that was normalized by IBTX. IBTX was without effect on K+ current in controls. We conclude that hypobaric CH induces increased endothelial BKCa channel activity that contributes to reduced myogenic responsiveness and EC and VSM cell hyperpolarization.

Keywords: large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel; myogenic response; endothelium-dependent vasodilation; membrane potential; patch clamp

chronic hypoxia (ch) results from pathological conditions that impair oxygenation, as well as from prolonged residence at high altitude. Previous studies have demonstrated that vasoconstrictor responsiveness of the systemic circulation is attenuated following prolonged exposure to hypoxia (1, 7, 22, 42). Diminished vasoconstrictor reactivity following CH is observed both systemically as a reduced total peripheral resistance response to vasoconstrictor agonists (7) and in several individual vascular beds (1, 4, 25, 34), suggesting that it is a generalized response to this stimulus. Furthermore, since diminished vasoconstrictor activity is maintained following acute return to normoxia (1, 7) and is largely unaffected by Po2 (7), this response to CH appears to be an adaptation, distinct from acute responses to hypoxia.

Blunting of both agonist-induced and myogenic vasoconstriction following CH appear to be endothelium dependent. For example, reduced agonist-induced vasorelaxation is reversed following endothelial disruption in both aorta (4, 7) and resistance arteries (8) from CH rats. A similar endothelium dependence is observed in attenuated myogenic reactivity following CH in mesenteric arterioles (7). Furthermore, CH-induced blunted vasoconstriction in the mesenteric vascular bed is associated with an endothelium-dependent reduction in vascular smooth muscle (VSM) calcium, as well as VSM hyperpolarization (8, 10, 11). Thus the endothelium appears to play a central role in altered vasoreactivity following CH.

Although the mechanisms responsible for altered responsiveness in the vasculature during CH are not fully defined, previous experiments suggest that endothelial nitric oxide (NO) (11), carbon monoxide (CO) (4, 18, 25, 31, 34), and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (9) may be involved. In addition, VSM membrane potential (Em) and vasoreactivity are restored in mesenteric resistance arteries from CH rats following inhibition of large-conductance, calcium-activated K+ (BKCa) channels (9, 32). Since NO, CO, and EETs are all endogenous activators of these channels, a primary role of BKCa in altered vasoreactivity following CH is likely.

Calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channels are widely distributed in vascular tissue. They are classified into BKCa, and intermediate- (IKCa) and small-conductance (SKCa) channels. KCa channels exert a powerful effect on Em of both VSM and endothelial cells (ECs) in resistance arteries, and the level of KCa channel expression and activity is a fundamental determinant of vascular tone and blood pressure in both health and disease (40). Activity of VSM BKCa channels is regulated by calcium sparks from ryanodine-sensitive stores and acts to promote VSM hyperpolarization and reduced calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (24). Endothelial SKCa and IKCa channels appear to play a prominent role in agonist-induced endothelial hyperpolarization and consequent vasodilation (6, 13, 17, 19, 20). However, the physiological significance of endothelial BKCa channels has been questioned. Whereas several studies have demonstrated that BKCa channels are present in both freshly isolated and cultured ECs (2, 44), a role for these channels in control of vascular tone is controversial (2, 15, 23, 44).

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that enhanced activity of endothelial BKCa channels is responsible for blunted myogenic vasoconstrictor reactivity following CH. This hypothesis was based on several key observations, notably: 1) CH-induced attenuated vasoconstrictor reactivity is endothelium dependent and can be reversed by blockade of endogenous activators of BKCa channels (NO, CO, EETs); 2) the response to CH is BKCa dependent, however, dilation in response to endogenously produced CO in CH arteries is not affected by ryanodine (32), which inhibits VSM calcium sparks; and 3) EC intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) is elevated following CH (11), suggestive of EC hyperpolarization. Together, these data suggest that endothelial BKCa channels may be involved in diminished vasoreactivity following CH. Although much of our previous work was performed in mesenteric arteries, we chose to examine gracilis resistance arteries in the present study to not only extend our observations to another vascular bed, but also due to the reported lack of myoendothelial electrical coupling in the hindlimb circulation (37). This characteristic enables unambiguous assessment of the effects of CH on endothelial vs. VSM Em.

METHODS

Animals

Experiments were performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

Hypoxic Exposure

CH rats were exposed to hypobaric hypoxia at a barometric pressure of 380 mmHg for 48 h. Normoxic control rats were housed in identical cages at ambient pressure (∼630 mmHg).

Study of Isolated Resistance Arteries

Following exposure, rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg ip). Hindlimbs were removed and placed in ice-cold physiological saline solution [PSS; 119 mmol/l NaCl, 4.7 mmol/l KCl, 25 mmol/l NaHCO3, 1.18 mmol/l KH2PO4, 1.17 mmol/l MgSO4, 0.026 mmol/l K2-EDTA, 5.5 mmol/l glucose, and 2.5 mmol/l CaCl2]. Caudal femoral artery branches (third-order branches from the femoral artery; passive inner diameter at 100 mmHg, 150–200 μm) were dissected free, cannulated on glass pipettes, and mounted in an arteriograph. Arteries were slowly pressurized to 100 mmHg with PSS using a servo-controlled peristaltic pump (Living Systems) and superfused (10 ml/min) with warmed (37°C) PSS aerated with a normoxic gas mixture (21% O2/6% CO2/73% N2). All experiments were performed under normoxic conditions to examine sustained alterations in vascular control rather than acute vasodilatory responses to hypoxia (4, 32). Previous experiments have demonstrated that long-term adaptations following CH exposure appear by 48 h and are indistinguishable from effects of 4-wk exposure (25, 34). The effects may be partially or fully reversed following 96 h of normoxic exposure (25). Arteriole exposure to normoxic conditions for 2.5–3 h throughout the course of the experiment do not reverse sustained alterations elicited by CH exposure. For experiments involving endothelium-disrupted arteries, a 1-ml air bubble was passed through the vessel lumen after cannulation. Endothelium disruption was confirmed by the absence of a vasodilatory response to 10 μM acetylcholine (ACh). Vessels were prepared for measurement of inner diameter (8–11), intracellular calcium (11), or VSM or EC Em (8, 35), depending on the protocol.

Measurement of VSM and EC Em

VSM and EC Em was recorded from gracilis resistance arteries using sharp electrodes, as detailed previously (8, 33). VSM Em recordings were performed on pressurized arteries prepared as above, whereas endothelial Em was measured in artery strips with the luminal surface exposed. Arteries were superfused (2 ml/min) with a HEPES-buffered saline solution (HBSS) warmed to 37°C. Sharp electrodes (30–60 MΩ) were initially backfilled with Lucifer yellow (16.6 mg/ml in 1 M LiCl), followed by 1 M KCl, permitting post hoc epifluorescence dye identification of endothelial vs. VSM cells by the distinct cellular morphological and dye transfer characteristics of each cell type, as previously described (14).

Measurement of EC [Ca2+]i

EC [Ca2+]i was measured as described previously (11, 28). Briefly, fura solution (0.05 μM fura 2-AM and 0.05% pluronic in PSS) was administered to the lumen of pressurized caudal femoral arteries using a servo-controlled peristaltic pump (Living Systems) in the dark. Administration of fura 2-AM to the luminal surface for a short time has been previously shown to preferentially load ECs (11). After a 1-min loading period, the lumen was perfused with PSS for 15 min to wash out excess fura solution and allow hydrolysis of AM groups by intracellular esterases. The vessel preparation was constantly superfused with warmed, aerated PSS. Fura-loaded vessels were alternatively excited at 340 and 380 nm at a frequency of 10 Hz, and the respective 510-nm emissions were quantified using a photomultiplier tube and recorded with the use of Ionwizard software (Ionoptix, version 4.4). Photometric data were collected from the entire arterial segment under study. EC [Ca2+] was expressed as the mean 340- to 380-nm fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) from the background-subtracted 510-nm signal. Ratiometric images of unstimulated vessels were collected for ∼10 min, and then phenylephrine (PE; 1 μM) was administered, followed by 10 μM ACh. Lack of a change in EC calcium levels in response to PE demonstrated selective endothelial loading. ACh consistently induced an increase in EC [Ca2+], when administered to endothelium-intact vessels, as shown by elevated F340/F380. To further demonstrate selective endothelial loading, arteries were denuded with an air bubble at the end of the protocol, allowed 10-min recovery time, and PE and ACh tests were repeated. The lack of a change in F340/F380 in response to ACh after denudation was further evidence of selective endothelial loading.

Patch-clamp Studies of Isolated ECs

ECs were freshly dispersed from the aorta for electrophysiological study. The aorta was chosen as the source of cells based on our laboratory's earlier results showing parallel endothelium-dependent attenuation of vasoconstrictor reactivity following CH in aortic rings and resistance vessels that is similarly reversed by heme-oxygenase (HO) inhibition, but not affected by NO synthase (NOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX) blockade (4, 18). Aortas were removed and placed in ice-cold HBSS: 150 mmol/l NaCl, 6 mmol/l KCl, 1 mmol/l MgCl2, 1.5 mmol/l CaCl2, 10 mmol/l HEPES, and 10 mmol/l glucose and adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Thoracic aortas were cut longitudinally and subsequently incubated for 2 h in basal endothelial growth medium with 4% bovine serum albumin and 10 μg/ml of the endothelial specific probe, 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine percholorate (Ac-LDL-Dil) at 37°C. Immediately following the endothelial labeling procedure previously described (21, 35) aortas were cut into 2-mm strips and exposed to mild digestion solution containing 0.2 mg/ml dithiothreitol and 0.2 mg/ml papain in HBSS for 45 min at 37°C. Vessel strips were removed from the digestion solution and placed in 1 ml of HBSS containing 2 mg/ml BSA. Single ECs were released by gentle trituration with a small-bore Pasteur pipette and were stored at 4°C between experiments for up 5 h. One to two drops of the cell suspension were seeded on a glass coverslip mounted on an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71) for 30 min before superfusion. Single ECs were identified by the selective uptake of the fluorescently labeled acylated low-density lipoprotein Ac-LDL-Dil with a rhodamine filter before each electrophysiological experiment. Freshly dispersed ECs were superfused under constant flow (2 ml/min) at room temperature (22–23°C) in an extracellular solution (141 mmol/l NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 1 mmol/l MgCl2, 1 mmol/l CaCl2, 10 mmol/l HEPES, 10 mmol/l glucose, and buffered to pH 7.4 with NaOH). Whole cell current data were generated with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) following a 5-min dialysis period with 4–6 MΩ patch electrodes filled with an intracellular solution (140 mmol/l KCl, 0.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 5 mmol/l Mg2ATP, 10 mmol/l HEPES, 1 mmol/l EGTA, and adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH). CaCl2 was added to yield a free [Ca2+] of 1 μM, as calculated using WinMAXC chelator software. On attainment of whole cell patch-clamp configuration, only ECs with series resistances <15 MΩ that maintained 1 GΩ or greater seal resistances throughout the course of the experiment were kept for analysis. Whole cell currents were measured in response to voltage steps applied from −60 to +150 mV in 10-mV increments from a holding potential of −60 mV. Cell capacitance was monitored, and transmembrane currents were expressed in terms of current density (pA/pF). There were no differences in cell capacitance between groups.

Immunofluorescence in Sectioned Arteries

Arteries from control and CH rats were collected following transcardial perfusion with PSS containing 10 mg papaverin. The gracilis muscle was removed and frozen in OCT compound in liquid N2 and isopentane. Ten-micrometer sections were adhered to superfrost slides (Fisher) and fixed in 4% formaldehyde PBS at room temperature for 10 min. After fixation, cells were permeabilized in 0.01% Triton-X PBS for 10 min and blocked in 4% donkey serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cross sections were incubated with primary antibodies for BKCa α-subunit (BK-α) and β1-subunit (BK-β1) (Alamone). Some sections were additionally treated with the endothelial marker, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-1 (Santa Cruz) and BK-α for endothelial-specific localization. Primary antibodies for BK-α or BK-β1 were detected with Cy5-conjugated donkey, anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. PECAM-1 was detected with a Cy3-conjugated donkey, anti-mouse secondary antibody (all secondaries 1:500 dilution; Jackson Laboratories). The nuclear stain, Sytox (1:10,000 dilution; Molecular Probes) was then applied. Sections were visualized with a confocal laser microscope (LSM 510 Zeiss; ×63 oil immersion lens).

Immunofluorescence of Isolated ECs

ECs were freshly dispersed from the aorta (see detailed methods above) and used for immunofluorescent detection of BK-α and BK-β1. One to two drops of the cell suspension were seeded on a glass coverslip for 30 min before fixation in 4% formaldehyde PBS at room temperature for 15 min. After fixation, cells were permeabilized in 0.01% Triton-X PBS for 10 min and blocked in 4% donkey serum in PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for BK-α/β1 (Alamone) and detected with Cy5-conjugated donkey, anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. Isolated cells were visualized with a confocal laser microscopy (LSM 510 Zeiss; ×63 oil immersion lens).

Experimental Protocols

Myogenic responses.

Experiments in this and subsequent protocols were performed under normoxic conditions to examine sustained alterations in vascular control rather than acute vasodilatory responses to hypoxia. Active and passive (Ca2+-free) pressure-diameter relationships were determined, as described previously (10) over intraluminal pressure steps between 40 and 140 mmHg. Vessel inner diameter was monitored using video microscopy and edge-detection software (IonOptix Sarclen). Initial diameters assessed in Ca2+-replete superfusate at a pressure below the autoregulatory range (20 mmHg) did not differ between groups and ranged from 105 ± 3 to 115 ± 3 μm. Endothelial integrity was assessed by constriction with 1 μM PE and dilation with 10 μM ACh before Ca2+-free superfusion. Pressure-induced vasoconstrictor responses were determined for endothelium-intact and endothelium-disrupted arteries, as well as endothelium-intact arteries in the presence of combined NOS inhibition [NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA); 100 μM] and COX inhibition (indomethacin: 10 μM). In addition, VSM Em was measured by sharp electrode at 40, 100, and 140 mmHg. Myogenic responsiveness was also determined during exposure to the following combinations of K+ channel inhibitors: 1) charybdotoxin (CBTX; combined IKCa and BKCa blocker; 100 nM) plus apamin (SKCa blocker; 100 nM); 2) TRAM-34 (selective IKCa blocker; 1 μM) plus apamin (100 nM); and 3) iberiotoxin (IBTX; specific BKCa blocker; 100 nM) alone. All K+ channel inhibitors were administered intraluminally in an effort to specifically target endothelial K+ channels. VSM Em was examined in separate experiments at 120 mmHg in the presence of all of the combinations of inhibitors except CBTX + apamin.

Effect of K+ channel blockers on endothelium-dependent vasodilatory responses to ACh.

Cumulative concentration-response curves to ACh (0.001–100 μM) were obtained in arteries pressurized at 100 mmHg. Vessels were preconstricted to 30% of equilibrated lumen diameter with PE before ACh administration. Vasodilatory responses were determined in arteries treated with the various inhibitors outlined above. Parallel experiments were performed in fura 2-loaded vessels to examine the endothelial calcium response to ACh. Finally, endothelial Em responses to 10 μM ACh were measured with sharp electrodes.

Effect of K+ channel blockers on basal endothelial Em.

EC Em was measured using sharp electrodes in arteries treated with the various inhibitors or respective vehicles.

Effect of K+ channel blockers on isolated EC transmembrane currents.

Transmembrane currents were measured in aortic ECs freshly dispersed from control and CH rats. After 5-min dialysis, whole cell currents were measured in response to voltage steps outlined above. After the initial recording, cells were superfused with the K+ channel inhibitors tetraethylammonium (TEA; 10 mmol) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 10 mM) to confirm measurement of K+ currents. Voltage steps were applied and recorded after 5 min of superfusion with these inhibitors.

Effect of BKCa channel inhibition and activation on isolated EC transmembrane currents.

After cell dialysis, recordings were taken before and 5 min after superfusion with the BKCa-specific inhibitor IBTX (100 nM), or the BKCa activator NS1619 {1,3 dihydro-1-[2-hydroxy-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-(trifluoromethyl)-2H-benzimidazol-2-one} (10 μM).

Effect of cholesterol depletion on isolated EC transmembrane currents.

Since BKCa channels in cultured ECs are inhibited by association with caveolin-1 (44), we examined the effect of cholesterol chelation on transmembrane currents in freshly dispersed cells from each group to confirm that channels were expressed in controls as well as CH cells. After cell dialysis, the cholesterol depletion drug, methyl-β-cylcodextrin (MBCD) (100 μM) was superfused for 15 min before washout. Voltage step recordings were taken before superfusion with MBCD. Following MBCD treatments, cells were superfused with IBTX (100 nM) to test for the presence of EC BKCa currents. Electron microscopy of MBCD-treated arteries demonstrated that this low concentration of the agent did not deplete the endothelia of caveolae (see Supplemental Fig. S4; the online version of this article contains supplemental data). Furthermore, caveolar number did not differ between arteries from control and CH rats (Supplemental Fig. S4).

BKCa subunit immunofluorescence in intact arteries and isolated ECs.

Endothelial expression of BK-α and BK-β1 was confirmed in sectioned resistance arteries and in freshly isolated aortic ECs using confocal immunoflourescence microscopy.

Calculations and Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SE. Values of n refer to the number of animals in each group, except for patch-clamp studies, where n represents the number of cells. Myogenic tone was calculated as the percent difference in inner diameter at each pressure when arteries were superfused with Ca2+-containing vs. Ca2+-replete PSS. Vasodilation was expressed as percent reversal of PE-induced preconstriction. Data were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance and by a Bonferroni modified unpaired Student's t-test for multiple comparisons when differences were indicated. Unpaired t-tests were used for single comparisons between groups. P ≤ 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Myogenic Responsiveness and VSM Cell Em in Pressurized Arteries

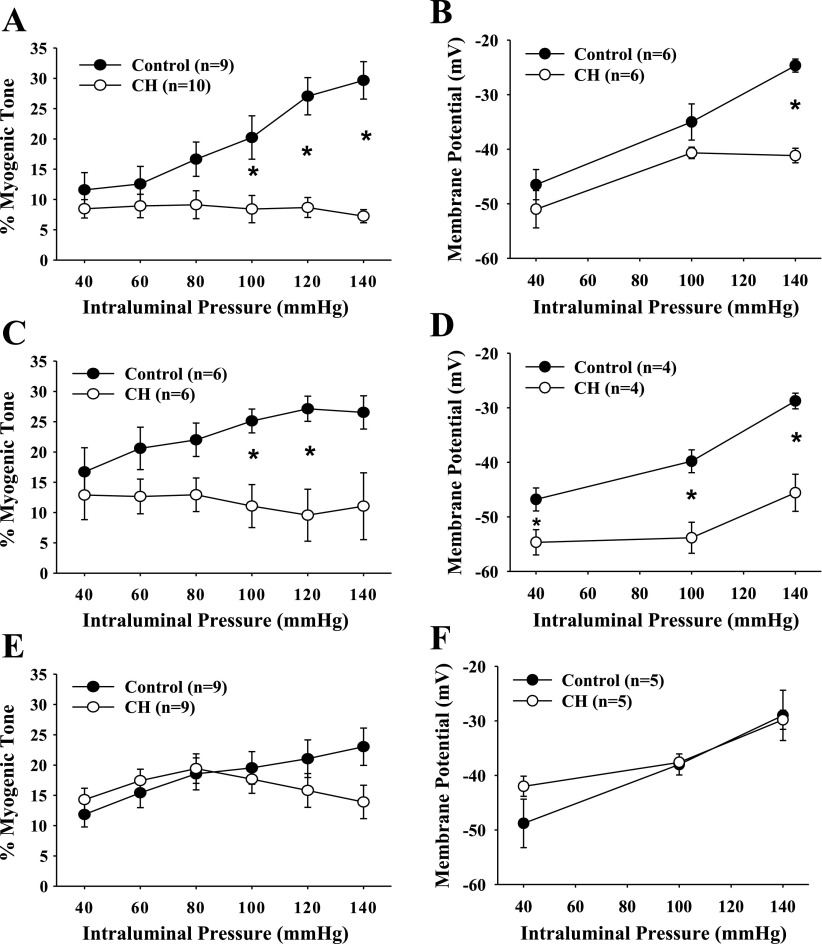

Myogenic vasoconstriction of gracilis resistance arteries from control and CH rats was assessed in normoxic conditions to study persistent vascular adaptations following CH exposure and not acute mechanism involved in responses to hypoxia. Myogenic vasoconstriction from CH rats was attenuated compared with normoxic controls (Fig. 1A), confirming findings from the mesenteric vascular bed (10, 33). Consistent with this finding, VSM cells in arteries from CH rats were hyperpolarized compared with controls at higher pressures (Fig. 1B), again confirming earlier results (8–10). Blunted myogenic responsiveness and VSM cell hyperpolarization of CH arteries compared with controls persisted in the presence of l-NNA and indomethacin (Fig. 1, C and D). Myogenic responses and VSM Em in the presence of vehicles for l-NNA and indomethacin were not different from those of untreated arteries (data not shown). Endothelial disruption restored myogenic reactivity and Em of CH arteries to control levels (Fig. 1, E and F) (8, 10). Effectiveness of endothelial disruption was verified by elimination of ACh-induced dilation. Lucifer yellow loading allowed visual identification of the cell type from which Em recordings were obtained.

Fig. 1.

Myogenic tone (A, C, and E) and vascular smooth muscle (VSM) membrane potential (Em; B, D, and F) as a function of intraluminal pressure for endothelium-intact (A and B), NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA) and indomethacin (Indo)-treated (C and D), and endothelium-disrupted (E and F) gracilis arteries isolated from normoxic control and chronic hypoxia (CH) rats. Values are means ± SE; n, no. of rats. *P < 0.05, normoxic control vs. CH.

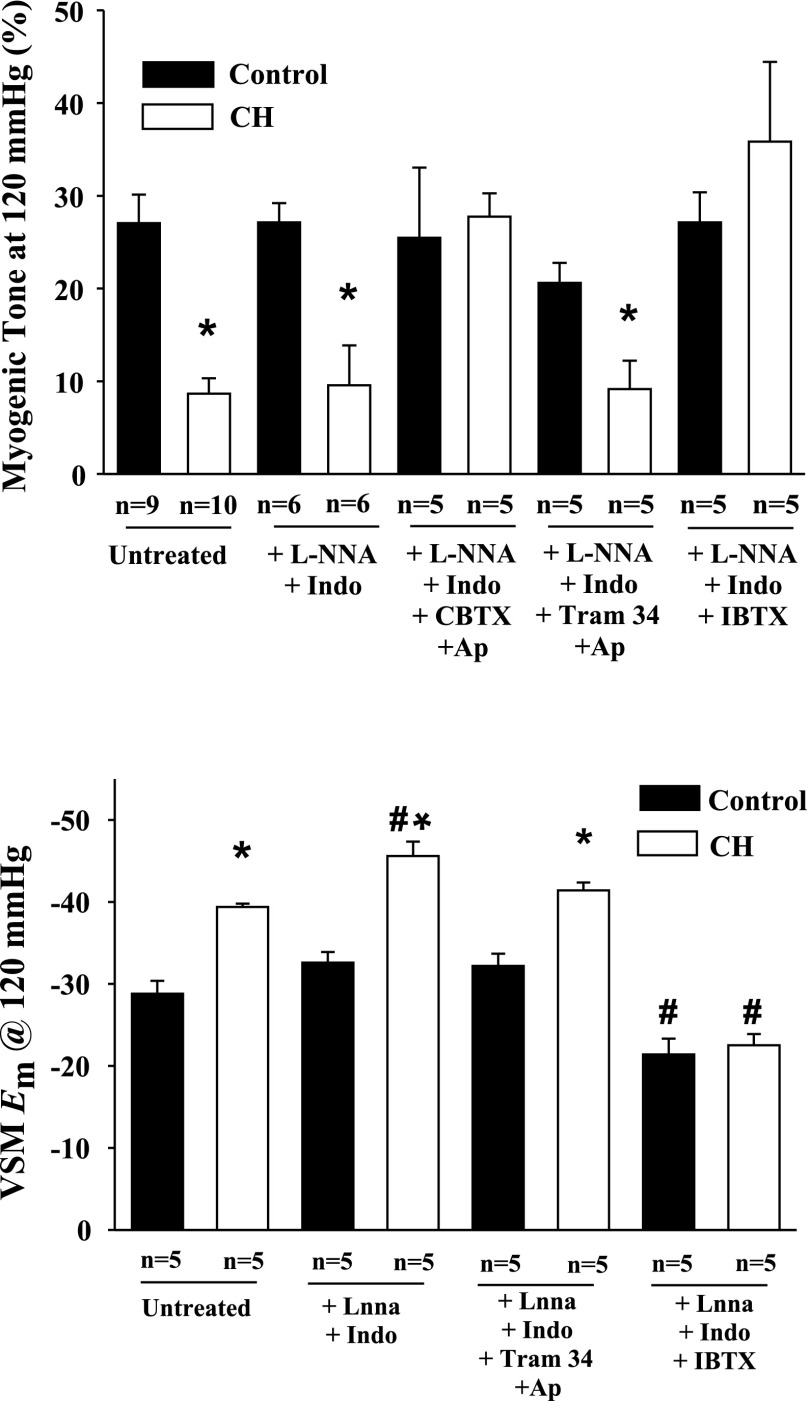

Effect of K+ Channel Inhibitors on Myogenic Responsiveness and VSM Em

The effects of K+ channel inhibitors were assessed at a transmural pressure of 120 mmHg. CH arteries demonstrated reduced myogenic responsiveness at this pressure compared with arteries from controls, which persisted in the presence of l-NNA and indomethacin (Fig. 2, top). Luminal exposure to CBTX and apamin restored myogenic responsiveness of CH arteries at 120 mmHg to control levels. However, specific inhibition of endothelial IKCa and SKCa channels did not affect myogenic responsiveness in either group. In contrast, IBTX alone also restored myogenic responsiveness in CH arteries to control levels without affecting reactivity in the controls. This latter observation is supportive of an endothelial-specific effect of intraluminal IBTX. A similar pattern of K+ channel inhibitor effects was seen on VSM Em. As discussed previously, VSM cells from CH arteries were hyperpolarized compared with controls at 120 mmHg, and this hyperpolarization persisted in the presence of NOS and COX inhibitors, as well as in the presence of endothelial SKCa and IKCa inhibition (Fig. 2, bottom). However, IBTX restored VSM Em to control levels when administered luminally (Fig. 2, bottom). VSM cells in control vessels treated with IBTX were slightly depolarized compared with untreated control arteries, although myogenic tone was unaffected. Myogenic responses and VSM Em at 120 mmHg in the presence of vehicles were not different from those of untreated arteries (data not shown). To contrast luminal application of IBTX, a separate set of experiments employed IBTX applied to the superfusate to specifically target VSM. In contrast to luminal application, superfusate administration of IBTX resulted in a significant increase in spontaneous tone at 100 mmHg in control arteries (data not shown). These results suggest that luminal administration of IBTX selectively targets endothelial BKCa channels with minimal direct effect on the VSM.

Fig. 2.

Myogenic tone (top) and VSM Em (bottom) in endothelium-intact gracilis arteries isolated from normoxic control and CH rats at 120 mmHg from untreated, l-NNA and Indo-treated arteries, and arteries exposed to different combinations of intraluminal K+ channel inhibitors. CBTX, charybdotoxin; Ap, apamin; IBTX, iberiotoxin. Values are means ± SE; n, no. of rats. *P < 0.05, normoxic control vs. CH. #P < 0.05 for untreated vs. treated arteries within groups.

Effect of K+ Channel Blockers on Basal Endothelial Em

Resting Em in dye-identified ECs were hyperpolarized in arteries from CH rats compared with controls (Fig. 3). This hyperpolarization persisted in the presence of l-NNA and indomethacin and after inhibition of IKCa and SKCa channels (Fig. 3). In contrast, IBTX restored CH EC Em values to control levels, but did not affect controls (Fig. 3). Em in the presence of vehicles was not different from those of untreated arteries (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Endothelial cell (EC) Em in gracilis artery strips isolated from normoxic control and CH rats. EC Em was assessed in untreated, l-NNA and Indo-treated arterial strips, and arterial strips exposed to different combinations of K+ channel inhibitors. Values are means ± SE; n, no. of rats. *P < 0.05, normoxic control vs. CH. #P < 0.05 for CH untreated vs. CH IBTX-treated strips.

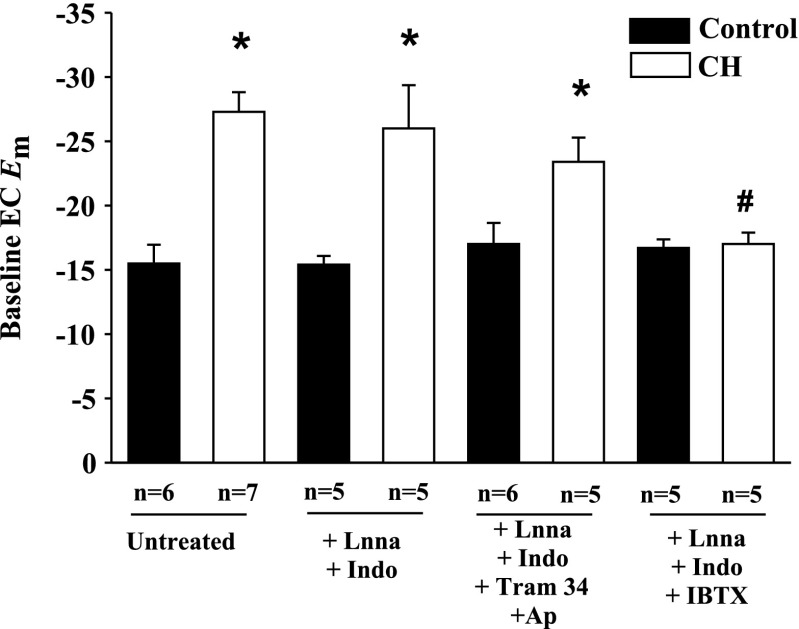

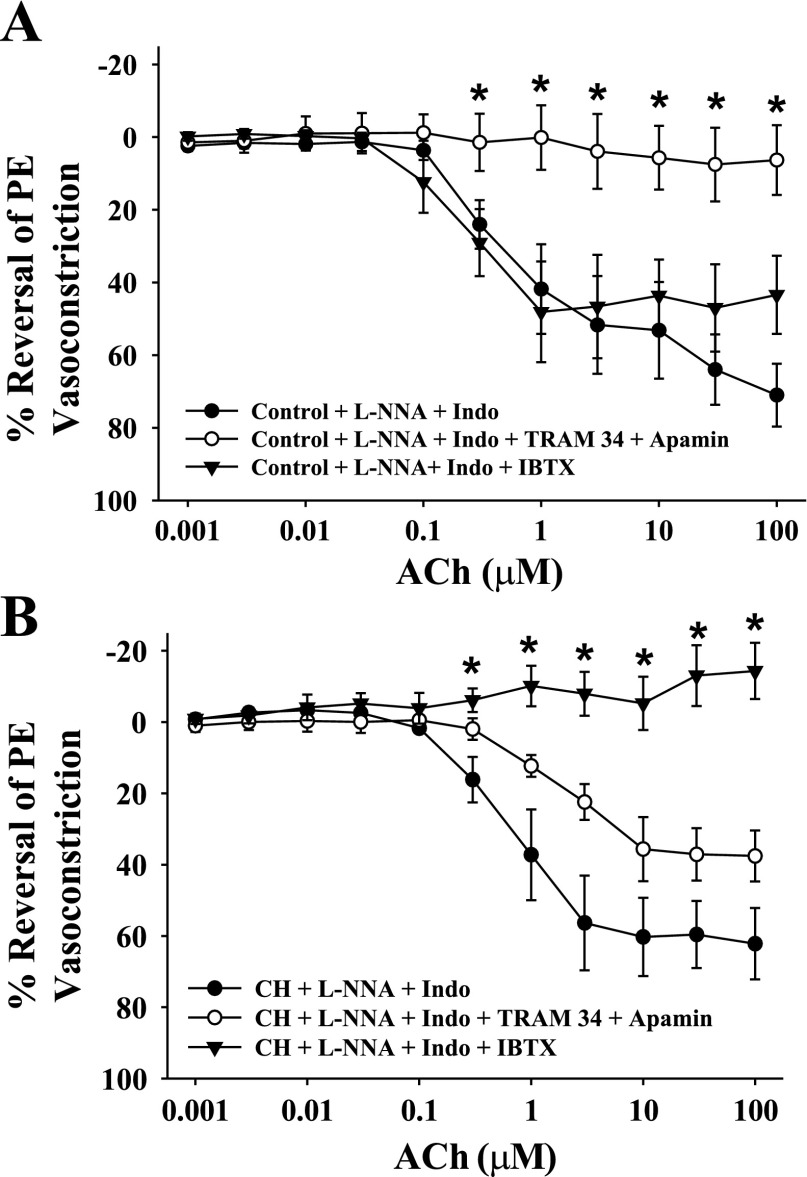

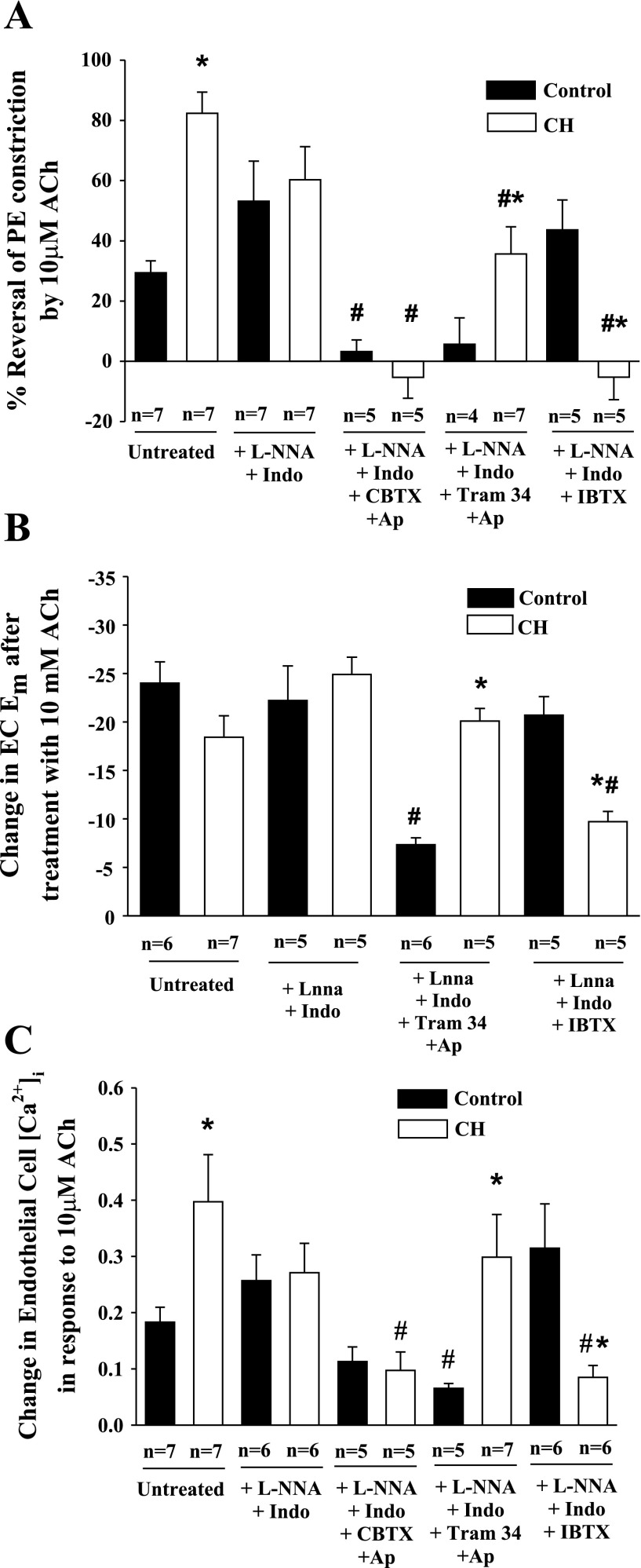

Effect of K+ Channel Blockers on Endothelium-dependent Vasodilatory Responses to ACh

ACh-induced vasodilation was observed following l-NNA and indomethacin treatment in arteries from both groups demonstrating an EDHF-type response. This response was abolished by combined intraluminal administration of SKCa and IKCa blockers in control arteries, but unaffected by BKCa inhibition (Fig. 4A). In contrast, ACh dilation was eliminated by BKCa blockade with IBTX in arteries from CH rats (Fig. 4B). Figure 5 compares the effect of the various inhibitors on vasodilation, Em, and EC [Ca2+]i responses to 10 μM ACh. Vasodilatory responses were greater in untreated arteries from CH rats compared with controls (Fig. 5A). As shown in the previous figure, arteries from both groups still demonstrated vasodilatory responses after NOS and COX inhibition (Fig. 5A), although there was no longer a difference between groups. The normalization of vasodilatory responses between groups by combined l-NNA and indomethacin was the result of opposing tendencies between the two groups. ACh responsiveness tended to be slightly reduced in arteries from CH rats by this treatment, although this trend did not reach statistical significance. Similarly, vasodilation to ACh tended to increase with treatment. These data suggest that control vessels may possess a COX-dependent vasoconstrictor pathway that elicits VSM depolarization that is not present in arteries from CH rats. Following COX and NOS blockade, dilation to ACh was abolished in arteries of both groups exposed luminally to CBTX and apamin to inhibit endothelial SKCa, IKCa, and BKCa (Fig. 5A). In contrast, specific inhibition of endothelial SKCa and IKCa with TRAM-34 and apamin eliminated ACh-induced vasodilation only in arteries from control rats. Additionally, although treatment with the BKCa inhibitor IBTX alone had no effect on vasodilatory responses in controls, this agent abolished vasodilation in arteries from CH rats. In all cases, the effects of the blockers were similar at all concentrations of ACh studied. Endothelial disruption abolished ACh-induced vasodilation in both groups. Changes in EC Em (Fig. 5B) and EC [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5C) in response to ACh were also examined, and the K+ channel inhibitors elicited a profile similar to the vasodilatory responses. Although the change in Em in response to ACh in CH untreated arterial strips was not different from that of controls, basal Em was hyperpolarized relative to controls (Fig. 3), and thus the degree of hyperpolarization following ACh was greater in the CH group. ACh-induced hyperpolarization was not affected by combined l-NNA and indomethacin in either group. Similar to the vasodilatory responses, combined treatment with TRAM-34 and apamin impaired hyperpolarization in response to ACh only in the controls, whereas IBTX blunted ACh-induced EC hyperpolarization only in arteries from CH rats (Fig. 5B). EC [Ca2+]i responses to ACh closely mirrored the vasodilatory responses in each treatment group (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 4.

Concentration-response curves [%reversal of phenylephrine (PE) vasoconstriction] to acetylcholine (ACh) for control (A) and CH (B) gracilis arteries after treatment with l-NNA + Indo (n = 7 both groups), l-NNA + Indo + TRAM-34 + Ap (n = 4 control, n = 7 CH), or l-NNA + Indo + IBTX (n = 6 control, n = 5 CH). Values are means ± SE; n, no. of rats. *Differs from l-NNA + Indo for each group, P < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

ACh-induced responses in gracilis arteries isolated from normoxic control and CH rats. Vasodilation responses (A), changes in Em (B), and EC intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i; C) are shown in response to 10 μM ACh from untreated, l-NNA and Indo-treated arteries, and arteries exposed to different combinations of K+ channel inhibitors. Values are means ± SE; n, no. of rats. *P < 0.05, normoxic control vs. CH. #P < 0.05, untreated vs. treated strips within groups.

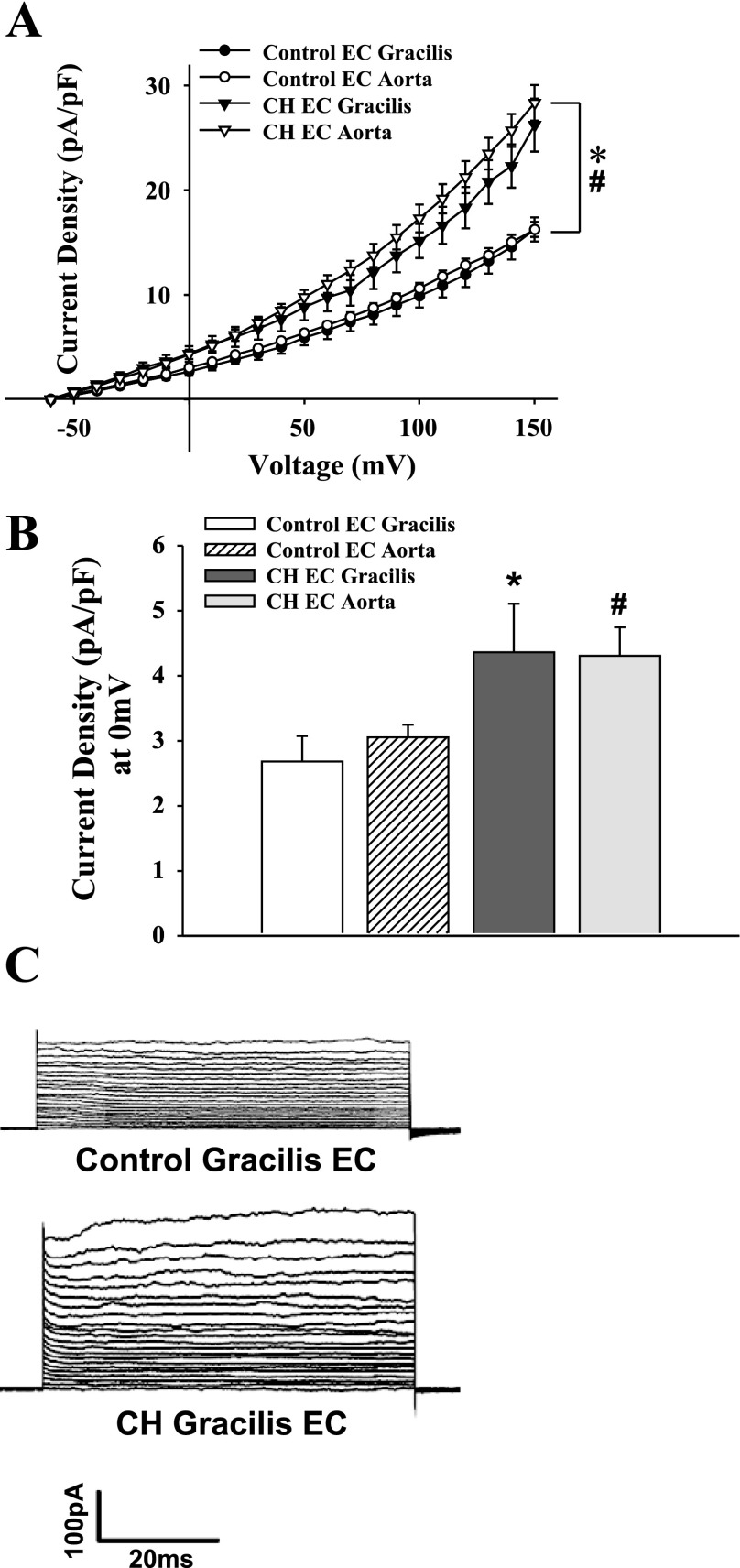

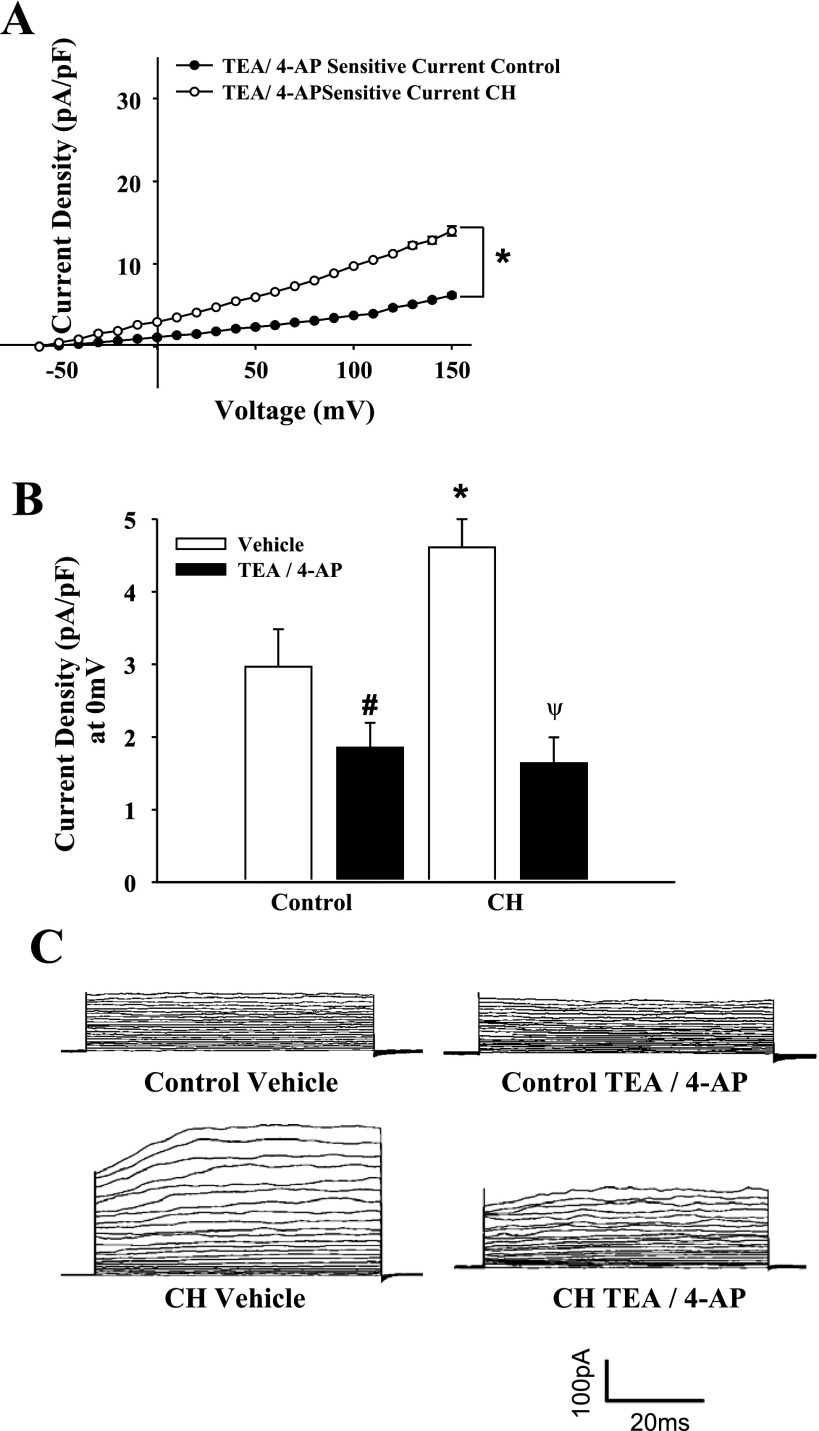

Effect of K+ Channel Blockers on Isolated EC Transmembrane Currents

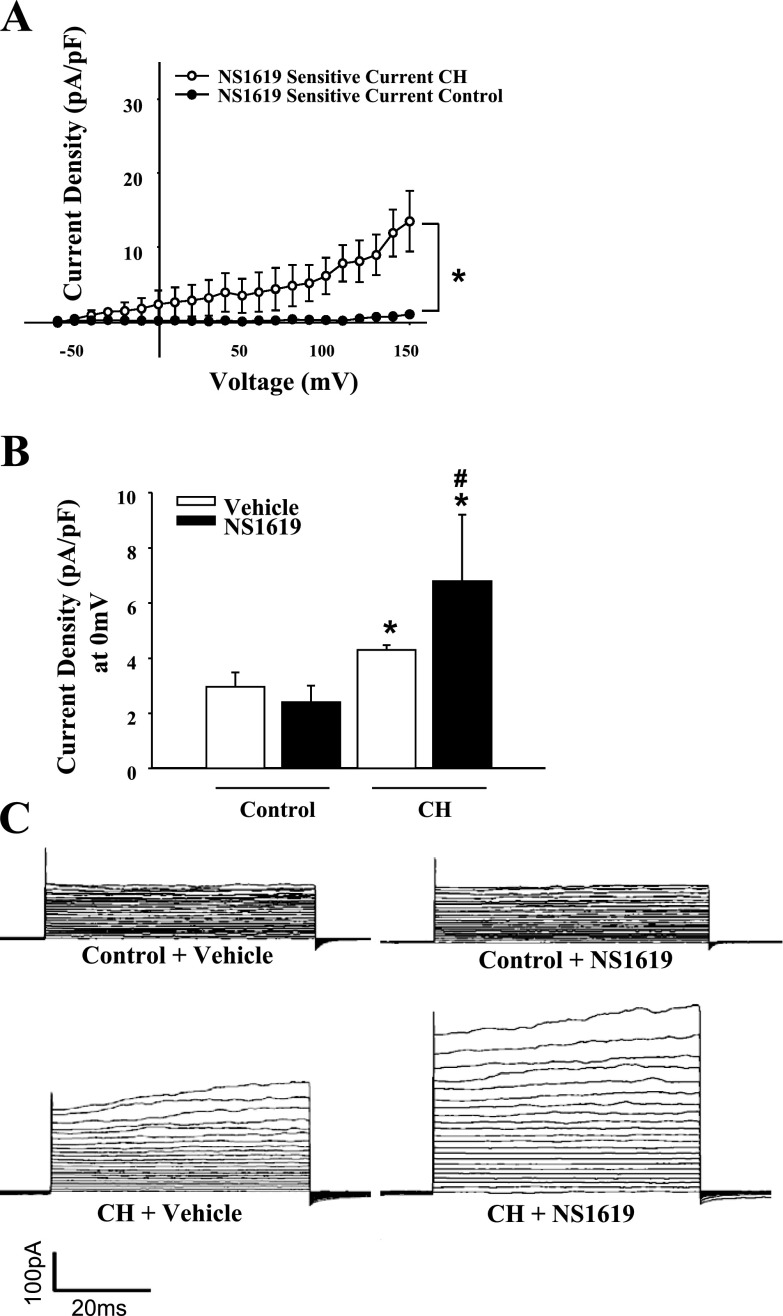

Whole cell currents from freshly isolated ECs from CH and control animals were studied under normoxic conditions to assess long-term adaptations to hypoxia and not acute hypoxic exposure effects. Whole cell currents in isolated ECs were greater over a wide range of voltages in cells from CH rats compared with controls (Fig. 6). Treatment with the K+ channel inhibitors TEA and 4-AP nearly abolished currents in both groups, indicative of K+ conductance. Outward K+ currents from the CH group and controls were significantly reduced following TEA and 4-AP blockade (Fig. 7). Residual current after TEA and 4-AP treatment was not different between the groups (Fig. 7, B and C). To selectively block EC BKCa channels, current sensitivity to IBTX was tested. The difference in current between control and CH groups was eliminated by IBTX, whereas IBTX was without effect in control cells (Fig. 8). In addition, the BKCa activator NS1619 elicited a further increase in outward current in cells from CH rats, but was without effect in controls (Fig. 9). Administration of a NO donor increased EC BKCa currents at depolarized potentials (Supplemental Fig. S5), but had no significant effect in controls.

Fig. 6.

Whole cell K+ currents from gracilis and aortic ECs from normoxic control (aortic: n = 10, gracilis: n = 9 cells) and CH rats (aortic: n = 9, gracilis: n = 5 cells). A: whole cell K+ currents in both gracilis (*) and aortic (#) ECs from control rats were significantly less than CH at all voltage steps. B: currents at a physiologically relevant potential of 0 mV (*different from gracilis control; #different from aortic control). Currents were not different between aortic or gracilis ECs within groups (A and B). Values are means ± SE. C: gracilis EC voltage step traces from control and CH treatments.

Fig. 7.

Administration of K+ channel inhibitors tetraethylammonium (TEA; 10 mM) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 10 mM) reduced total whole cell K+ currents (n = 5 cells, controls and CH). A: current subtraction data showing that TEA/4-AP-sensitive transmembrane currents were greater in the CH group compared with control at all voltage steps. B: data at the test potential of 0 mV, where currents were normalized by TEA/4-AP between groups. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, CH vs. normoxic control. #P < 0.05, control TEA/4-AP vs. control untreated. ψP < 0.05, CH TEA/4-AP vs. CH untreated. C: voltage step traces from control and CH groups with vehicle or TEA/4-AP.

Fig. 8.

Effects of large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channel inhibition in aortic ECs. IBTX (100 nM) diminished whole cell K+ current in CH (n = 9) cells to control levels, but had no effect on control (n = 8) cells. A: IBTX-sensitive current over the entire range of voltage steps derived by current subtraction. B: data at the test potential of 0 mV. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, CH vs. normoxic control. C: traces from voltage steps with vehicle and IBTX treatments.

Fig. 9.

A: the BKCa activator NS1619 was without effect in control cells (n = 3), but increased outward current in cells from CH rats (n = 4). B: comparisons between groups were conducted at the testing potential of 0 mV. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, CH vs. normoxic control. #P < 0.05, different from untreated CH. C: traces in the presence of vehicle or NS1619.

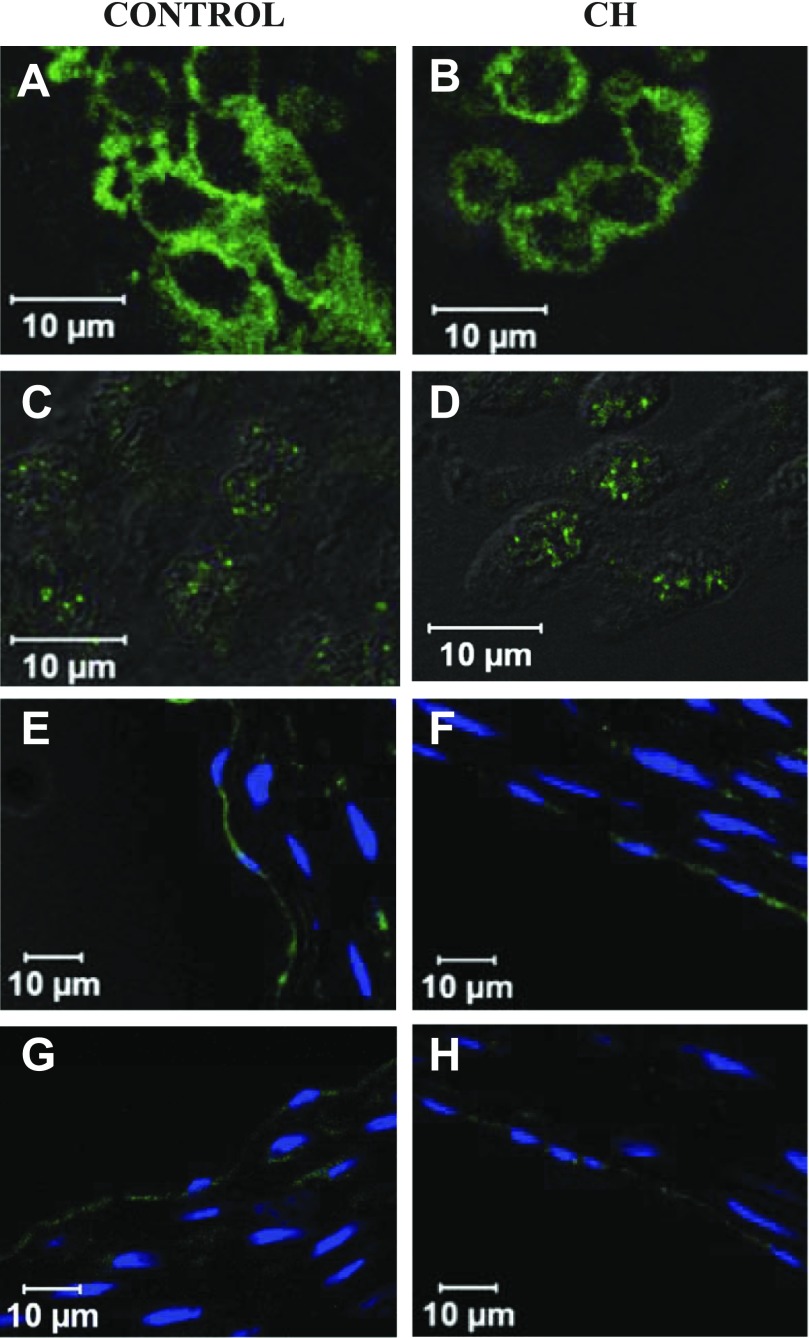

Immunofluorescent localization of BKCa.

Although these data suggest differential expression of BKCa channels between groups, we observed similar BKCa α-immunofluorescence in isolated aortic ECs from control and CH rats (Fig. 10, A and B) and in intact sections of gracilis resistance arteries (Fig. 10, E and F). The β1 regulatory subunit for the BKCa channel was also observed in ECs from both groups (Fig. 10, C and D, G and H). Endothelial localization was confirmed by with the endothelial specific marker PECAM-1 (Supplemental Data Fig. S2). No staining for either subunit was observed when only secondary antibody was applied (Supplemental Data Fig. S1). In addition, no staining was observed in rat T-cells that do not express BKCa channels (Supplemental Data Fig. S3).

Fig. 10.

Positive immunofluorescence for BKCa α-subunit (BK-α) and β1-subunit (BK-β1) in freshly dispersed ECs and gracilis cross sections from control (left) and CH (right) rats. A–D: positive staining for BK-α (A and B) and BK-β1 (C and D) in aortic ECs from control and CH rats, respectively. E–H: positive staining for BK-α (E and F) and BK-β1 (G and H) in gracilis cross sections from control and CH rats, respectively.

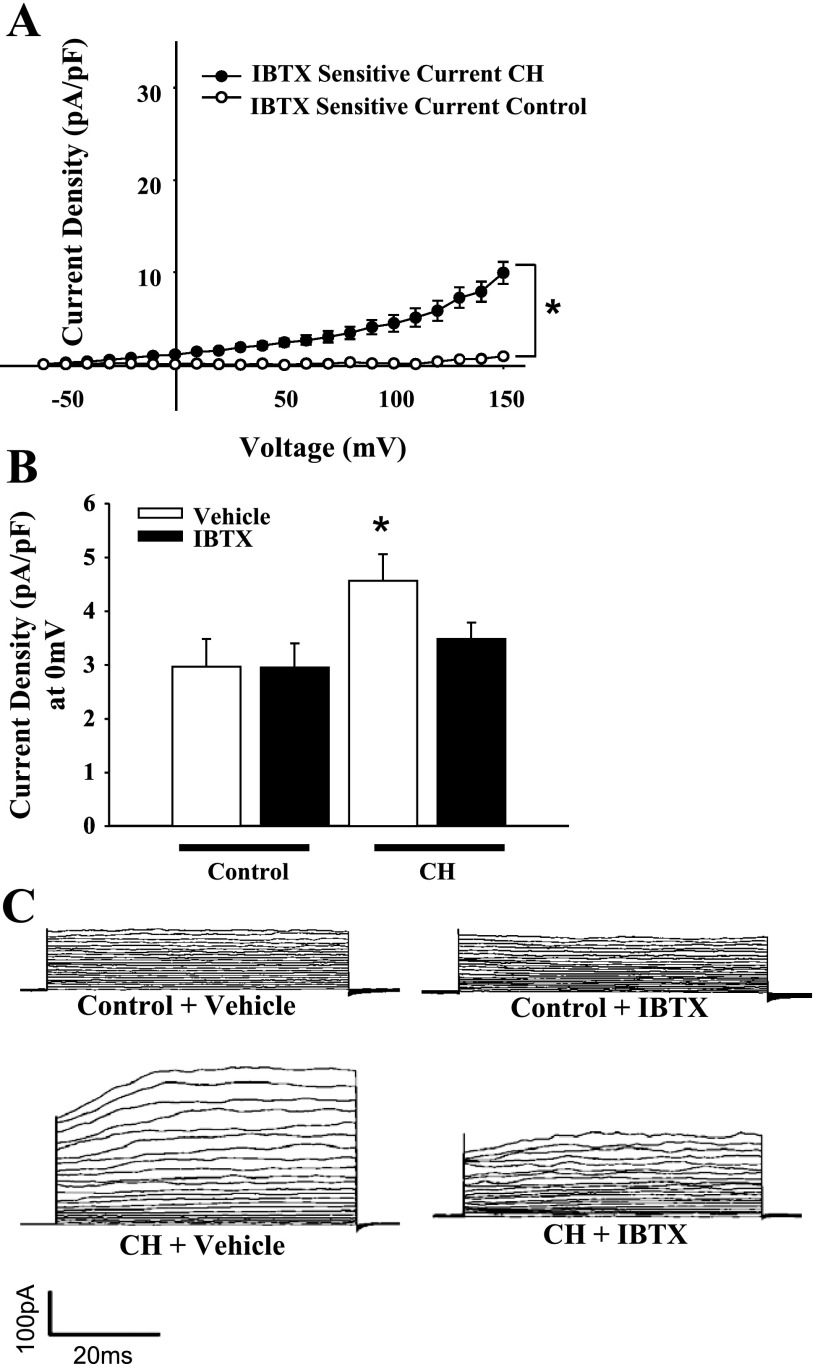

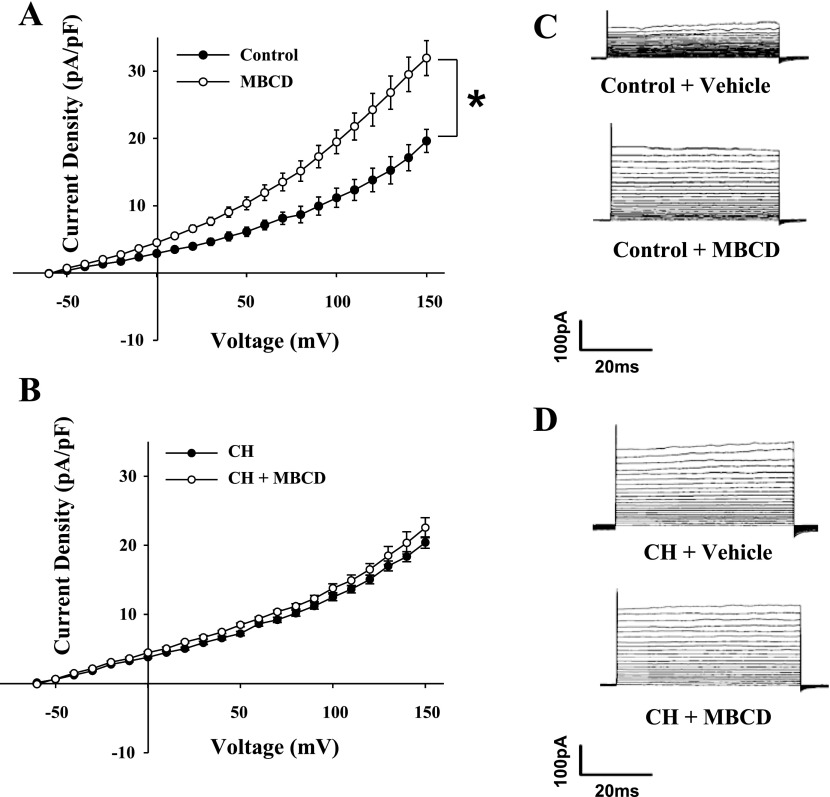

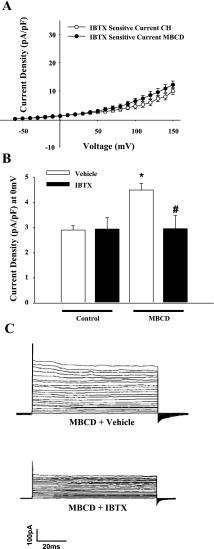

Effect of Cholesterol Depletion on Isolated EC Transmembrane Currents

Endothelial whole cell currents from control animals were significantly increased following cholesterol depletion with MBCD (Fig. 11, A and C), whereas currents from CH animals were unaffected (Fig. 11, B and D). The enhanced currents from controls were found to be sensitive to IBTX treatment (Fig. 12), supporting the immunofluorescence results that BKCa exist in both controls and CH ECs and are not differentially expressed. This effect of MBCD is likely due to mild cholesterol depletion, since the effects on outward currents can be reversed by cholesterol supplementation (unpublished data).

Fig. 11.

Cholesterol depletion with methyl β-cyclodextrin (MBCD) increased K+ currents in ECs from control animals (A) with no effect on cells from CH rats (B). Values are means ± SE. C: traces from control cells before and after treatment with MBCD. D: traces from CH animal ECs before and after treatment with MBCD. *P < 0.05, MBCD vs. control.

Fig. 12.

A: the increased current in MBCD-treated control ECs was sensitive to IBTX (100 nM) and demonstrated similar magnitude to IBTX-sensitive current observed in CH ECs. B: normalization of outward current by IBTX in MBCD-treated control cells at a physiologically relevant potential of 0 mV. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, MBCD vs. control. #P < 0.05, MBCD IBTX vs. MBCD. C: traces from MBCD-treated cells in vehicle or IBTX.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the contribution of endothelial BKCa channels to altered vasoreactivity following hypobaric CH. The major findings of this study are as follows: 1) CH is associated with endothelium-dependent VSM hyperpolarization and associated blunted myogenic constriction and persistent VSM hyperpolarization; 2) EC Em is also hyperpolarized after CH exposure and restored by BKCa channel inhibition; 3) similarly, selective EC BKCa blockade restores myogenic reactivity and VSM Em to control and blocks endothelium-dependent vasodilatory responses to ACh; 4) ECs isolated from CH rats demonstrate an IBTX-sensitive outward current not present in cells from control animals; and 5) the IBTX-sensitive outward current is revealed in cells from control animals following cholesterol depletion. These results suggest that endothelial BKCa activity is increased by CH and is responsible for altered vasoreactivity.

The blunted myogenic reactivity and VSM hyperpolarization observed in gracilis resistance arteries from CH rats are consistent with previous observations of diminished vasoconstrictor reactivity in mesenteric arterioles (8–11, 18, 33), diaphragmatic arteries (42), and aortic rings (1) after 48-h CH. Although the present study used a hypobaric model of CH, similar attenuation of vasoconstrictor reactivity is observed with normobaric CH of similar duration and inspired Po2 (1). Unlike the mesenteric circulation where myogenic tone developed at lower pressures (10), gracilis arteries from control rats did not develop significant myogenic tone until pressures of 80 mmHg were reached. Consequently, differences between control and CH arterial myogenic tone were not observed, except at the higher end of the pressure-diameter relationship in gracilis arteries, whereas, in the mesenteric arteries, this difference is apparent over most of the pressure-diameter relationship (10). In further agreement with earlier studies (10, 33), blunted myogenic reactivity and VSM hyperpolarization of CH arteries persisted in the presence of NOS and COX inhibition, but was reversed by endothelial disruption. Endothelial disruption could potentially have unintended direct effects on smooth muscle reactivity; however, there was no significant difference in myogenic tone between control vessels with an intact or disrupted endothelium. These results convincingly demonstrate a role of the endothelium in attenuated myogenic responsiveness of small gracilis arteries after CH that is not dependent on release of NO or a COX product.

In addition to diminished myogenic reactivity, we observed that EC Em in isolated gracilis arteries was relatively hyperpolarized following CH. We chose to study gracilis resistance arteries based on recent observations that this bed does not demonstrate myoendothelial gap junction communication (37, 46, 48). This characteristic allowed examination of EC Em in a setting not influenced by responses conducted from the VSM. Consistent with Sandow et al. (37), we observed EC Em that was much more depolarized than the VSM in this vascular bed, suggesting that myoendothelial coupling is not present. The potentials measured were considerably more depolarized than we have observed in endothelia from intact pulmonary arteries (35) and mesenteric arteries (−47 ± 3 mV; unpublished observation) using identical techniques. These observations, coupled with the effectiveness of ACh to hyperpolarize the endothelium (Fig. 5B), suggest that the relatively depolarized Em observed under unstimulated conditions in this bed is not an artifact. EC hyperpolarization in CH arteries persisted following NOS and COX inhibition and in the presence of SKCa and IKCa inhibitors. In contrast, although IBTX did not alter EC Em values in arteries from control rats, it significantly depolarized CH EC Em to normoxic control levels. These results suggest that there is tonic activity of endothelial BKCa channels following CH exposure not seen in controls that results in EC hyperpolarization.

To further investigate the role of endothelial BKCa channels in vascular control following CH, we compared the effects of intraluminal administration of the various K+ channel inhibitors on vasodilatory, Em, and EC calcium responses to the endothelium-dependent dilator ACh between arteries from both groups. A hallmark of an agonist-induced EDHF-type response is its abolition by the combination of apamin and the nonselective K+-channel blocker CBTX (6, 19, 20). In the absence of myoendothelial gap junctions, VSM hyperpolarization can still occur due to either release of a diffusible EDHF, such as EETs (3), or by elevations in intercellular K+ levels (12). In the present study, combined apamin and CBTX completely inhibited vasodilation in response to ACh in both groups. However, since CBTX may block both IKCa and BKCa channels, we repeated these experiments with combined apamin plus the IKCa-selective inhibitor TRAM-34 (47). Consistent with other reports (6, 13, 17, 19, 20, 30), this treatment abolished ACh-induced dilation in arteries from control rats, suggesting a role of SKCa and IKCa channels in the EDHF-type response. In contrast, this treatment did not significantly inhibit dilation in the CH group, whereas BKCa channel inhibition with IBTX eliminated the response in this group. IBTX was without effect in control arteries, as previously shown by others (6, 20, 36). These data again support the hypothesis that BKCa channels play an important role in EC physiology following CH not observed under control conditions.

In agreement with other studies (30, 37), ACh stimulation elicited hyperpolarization in ECs of both groups. Although the change in Em in response to ACh did not differ between groups, peak ACh-stimulated Em was more hyperpolarized in CH ECs due to the shift in basal Em in that group. Although ACh induced hyperpolarization in both groups, the response was SKCa/IKCa dependent in normoxic controls, but BKCa dependent in arteries from CH rats. These findings in control arteries are in agreement with others who demonstrated that hyperpolarization in response to vasodilatory agonists is sensitive to SKCa (30, 39, 45) and IKCa (29, 45) inhibitors, but not BKCa blockers (39). Thus the reliance of ACh-induced EC hyperpolarization on BKCa channels following CH represents a switch from the normal involvement of IK/SK signaling in this response. This shift to a reliance on BKCa channels following CH was also observed when we examined the EC [Ca2+]i response to ACh. Elevation of EC [Ca2+]i following treatment with ACh occurs through multiple pathways. Em may be a contributing influence on Ca2+ influx by affecting the electrochemical driving force through nonselective entry pathways (26). However, other studies suggest that intracellular Ca2+ may be independent of changes in Em, as EC hyperpolarization in situ does not increase EC Ca2+ (16, 29, 41, 43). Additionally, increased calcium influx following muscarinic stimulation has been found to occur independent of changes in Em in freshly isolated ECs (5).

Earlier studies showing that blunted myogenic responsiveness following CH is reversed by either endothelial removal or administration of IBTX (10) made no attempt to differentiate between the roles of endothelial vs. VSM BKCa channels. In the present study, intraluminal administration of IBTX restored myogenic vasoconstriction and VSM Em in arteries from CH rats to levels similar to those of controls. This treatment was without effect on myogenic reactivity in control arteries, although VSM Em was slightly depolarized at 120 mmHg by IBTX in this group. Nevertheless, these experiments again suggest that endothelial hyperpolarization through BKCa channels is functionally important in regulating vascular tone following CH.

In support of studies in whole arteries, patch-clamp experiments demonstrated greater outward current in cells freshly isolated from CH rats that was normalized by IBTX. These results closely correlate with in situ assessment of EC Em in intact arteries and suggest that the difference in basal Em following CH is due to enhanced tonic activity of BKCa channels. Interestingly, the BKCa channel activator NS1619 caused increased current only in cells from CH animals. This latter result could be evidence for differential expression of BKCa channels between groups; however, we observed similar BKCa subunit immunofluorescence in ECs from control and CH rats.

It has recently been documented that BKCa activity is negatively regulated by caveolin-1 in cultured ECs (44). Cholesterol depletion with MBCD to disrupt caveolin function resulted in greater IBTX-sensitive outward currents in cultured human umbilical vein ECs (44). We hypothesized that CH exposure results in diminished caveolin-1 function, thereby activating BKCa. Thus we treated ECs from control animals with the cholesterol depletion agent MBCD to possibly release EC BKCa channels from caveolin inhibition and mimic CH. We chose the concentration of 100 μM MBCD to affect caveolin function, but not to eliminate caveolar structure. Previous studies using higher concentrations of MBCD in uterine myocytes ablated caveolar structure and, additionally, significantly decreased BKCa function (38). Electron microscopy analysis of 100 μM MBCD-treated cells revealed no significant changes in caveolar structure compared with untreated controls (Supplemental Fig. S4) and CH (not shown). Interestingly, treatment with MBCD revealed an IBTX-sensitive outward current in ECs from control animals, thus supporting earlier evidence in cultured cells of negative regulation of endothelial BKCa by caveolin. This treatment did not further enhance currents in cells from CH rats. These data also support our observation of similar channel immunofluorescence in cells from control and CH rats. Thus CH exposure may elicit channel activity through dissociation from caveolin-1. This is an interesting possibility, since endothelial HO-1 activity is similarly regulated by caveolin-1 (27), and our laboratory has previously shown that HO inhibition restores reactivity in an IBTX-sensitive fashion in CH arteries (32, 33). Thus HO-derived CO may play a role in tonic activation of endothelial BKCa channels following CH.

In summary, we have demonstrated a novel role of endothelial BKCa channels in vascular regulation following CH. Whereas these channels do not appear to be important in vasoreactivity in control arteries, CH exposure results in enhanced activity of endothelial BKCa channels that may account for earlier observations of diminished constrictor reactivity in this clinically relevant setting.

GRANTS

This publication was made possible by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grants HL95640 and HL63207.

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Auer G, Ward ME. Impaired reactivity of rat aorta to phenylephrine and KCl after prolonged hypoxia: role of the endothelium. J Appl Physiol 85: 411–417, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brakemeier S, Eichler I, Knorr A, Fassheber T, Kohler R, Hoyer J. Modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channel in renal artery endothelium in situ by nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Kidney Int 64: 199–207, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res 78: 415–423, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Caudill TK, Resta TC, Kanagy NL, Walker BR. Role of endothelial carbon monoxide in attenuated vasoreactivity following chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R1025–R1030, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen KD, Jackson WF. Membrane hyperpolarization is not required for sustained muscarinic agonist-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ in arteriolar endothelial cells. Microcirculation 12: 169–182, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crane GJ, Gallagher N, Dora KA, Garland CJ. Small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated K+ channels provide different facets of endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in rat mesenteric artery. J Physiol 553: 183–189, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doyle MP, Walker BR. Attentuation of systemic vasoreactivity in chronically hypoxic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 260: R1114–R1122, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Earley S, Naik JS, Walker BR. 48-h Hypoxic exposure results in endothelium-dependent systemic vascular smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R79–R85, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Earley S, Pastuszyn A, Walker BR. Cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase products contribute to attenuated vasoconstriction after chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H127–H136, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Earley S, Walker BR. Endothelium-dependent blunting of myogenic responsiveness after chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H2202–H2209, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Earley S, Walker BR. Increased nitric oxide production following chronic hypoxia contributes to attenuated systemic vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1655–H1661, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Edwards G, Dora KA, Gardener MJ, Garland CJ, Weston AH. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature 396: 269–272, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eichler I, Wibawa J, Grgic I, Knorr A, Brakemeier S, Pries AR, Hoyer J, Kohler R. Selective blockade of endothelial Ca2+-activated small- and intermediate-conductance K+-channels suppresses EDHF-mediated vasodilation. Br J Pharmacol 138: 594–601, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emerson GG, Segal SS. Electrical coupling between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in hamster feed arteries: role in vasomotor control. Circ Res 87: 474–479, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gauthier KM, Liu C, Popovic A, Albarwani S, Rusch NJ. Freshly isolated bovine coronary endothelial cells do not express the BK Ca channel gene. J Physiol 545: 829–836, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghisdal P, Morel N. Cellular target of voltage and calcium-dependent K(+) channel blockers involved in EDHF-mediated responses in rat superior mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol 134: 1021–1028, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gluais P, Edwards G, Weston AH, Falck JR, Vanhoutte PM, Feletou M. Role of SK(Ca) and IK(Ca) in endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations of the guinea-pig isolated carotid artery. Br J Pharmacol 144: 477–485, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gonzales RJ, Walker BR. Role of CO in attenuated vasoconstrictor reactivity of mesenteric resistance arteries after chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H30–H37, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hilgers RH, Todd J, Jr, Webb RC. Regional heterogeneity in acetylcholine-induced relaxation in rat vascular bed: role of calcium-activated K+ channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H216–H222, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hinton JM, Langton PD. Inhibition of EDHF by two new combinations of K+-channel inhibitors in rat isolated mesenteric arteries. Br J Pharmacol 138: 1031–1035, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hogg DS, McMurray G, Kozlowski RZ. Endothelial cells freshly isolated from small pulmonary arteries of the rat possess multiple distinct K+ current profiles. Lung 180: 203–214, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu XQ, Longo LD, Gilbert RD, Zhang L. Effects of long-term high-altitude hypoxemia on alpha 1-adrenergic receptors in the ovine uterine artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H1001–H1007, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jackson WF. Potassium channels in the peripheral microcirculation. Microcirculation 12: 113–127, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaggar JH, Porter VA, Lederer WJ, Nelson MT. Calcium sparks in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 278: C235–C256, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jernigan NL, O′Donaughy TL, Walker BR. Correlation of HO-1 expression with onset and reversal of hypoxia-induced vasoconstrictor hyporeactivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H298–H307, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kamouchi M, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Membrane potential as a modulator of the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration in agonist-activated endothelial cells. Gen Physiol Biophys 18: 199–208, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim HP, Wang X, Galbiati F, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Caveolae compartmentalization of heme oxygenase-1 in endothelial cells. FASEB J 18: 1080–1089, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Knot HJ, Lounsbury KM, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Gender differences in coronary artery diameter reflect changes in both endothelial Ca2+ and ecNOS activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H961–H969, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marrelli SP, Eckmann MS, Hunte MS. Role of endothelial intermediate conductance KCa channels in cerebral EDHF-mediated dilations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1590–H1599, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McSherry IN, Spitaler MM, Takano H, Dora KA. Endothelial cell Ca2+ increases are independent of membrane potential in pressurized rat mesenteric arteries. Cell Calcium 38: 23–33, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naik JS, O'Donaughy TL, Walker BR. Endogenous carbon monoxide is an endothelial-derived vasodilator factor in the mesenteric circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H838–H845, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naik JS, Walker BR. Heme oxygenase-mediated vasodilation involves vascular smooth muscle cell hyperpolarization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H220–H228, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Naik JS, Walker BR. Role of vascular heme oxygenase in reduced myogenic reactivity following chronic hypoxia. Microcirculation 13: 81–88, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Donaughy TL, Walker BR. Renal vasodilatory influence of endogenous carbon monoxide in chronically hypoxic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2908–H2915, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paffett ML, Naik JS, Resta TC, Walker BR. Reduced store-operated Ca2+ entry in pulmonary endothelial cells from chronically hypoxic rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1135–L1142, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parkington HC, Chow JA, Evans RG, Coleman HA, Tare M. Role for endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in vascular tone in rat mesenteric and hindlimb circulations in vivo. J Physiol 542: 929–937, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sandow SL, Tare M, Coleman HA, Hill CE, Parkington HC. Involvement of myoendothelial gap junctions in the actions of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circ Res 90: 1108–1113, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shmygol A, Noble K, Wray S. Depletion of membrane cholesterol eliminates the Ca2+-activated component of outward potassium current and decreases membrane capacitance in rat uterine myocytes. J Physiol 581: 445–456, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siegl D, Koeppen M, Wolfle SE, Pohl U, de Wit C. Myoendothelial coupling is not prominent in arterioles within the mouse cremaster microcirculation in vivo. Circ Res 97: 781–788, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sobey CG. Potassium channel function in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 28–38, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Takano H, Dora KA, Spitaler MM, Garland CJ. Spreading dilatation in rat mesenteric arteries associated with calcium-independent endothelial cell hyperpolarization. J Physiol 556: 887–903, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Toporsian M, Ward ME. Hyporeactivity of rat diaphragmatic arterioles after exposure to hypoxia in vivo. Role of the endothelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 1572–1578, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Koller A. Increases in endothelial Ca2+ activate KCa channels and elicit EDHF-type arteriolar dilation via gap junctions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1760–H1767, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang XL, Ye D, Peterson TE, Cao S, Shah VH, Katusic ZS, Sieck GC, Lee HC. Caveolae targeting and regulation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 11656–11664, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weston AH, Feletou M, Vanhoutte PM, Falck JR, Campbell WB, Edwards G. Bradykinin-induced, endothelium-dependent responses in porcine coronary arteries: involvement of potassium channel activation and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Br J Pharmacol 145: 775–784, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wigg SJ, Tare M, Tonta MA, O'Brien RC, Meredith IT, Parkington HC. Comparison of effects of diabetes mellitus on an EDHF-dependent and an EDHF-independent artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H232–H240, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wulff H, Miller MJ, Hansel W, Grissmer S, Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. Design of a potent and selective inhibitor of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, IKCa1: a potential immunosuppressant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 8151–8156, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zygmunt PM, Ryman T, Hogestatt ED. Regional differences in endothelium-dependent relaxation in the rat: contribution of nitric oxide and nitric oxide-independent mechanisms. Acta Physiol Scand 155: 257–266, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.