Abstract

Heterosis is a biological phenomenon whereby the offspring from two parents show improved and superior performance than either inbred parental lines. Hybrid rice is one of the most successful apotheoses in crops utilizing heterosis. Transcriptional profiling of F1 super-hybrid rice Liangyou-2186 and its parents by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) revealed 1183 differentially expressed genes (DGs), among which DGs were found significantly enriched in pathways such as photosynthesis and carbon-fixation, and most of the key genes involved in the carbon-fixation pathway exhibited up-regulated expression in F1 hybrid rice. Moreover, increased catabolic activity of corresponding enzymes and photosynthetic efficiency were also detected, which combined to indicate that carbon fixation is enhanced in F1 hybrid, and might probably be associated with the yield vigor and heterosis in super-hybrid rice. By correlating DGs with yield-related quantitative trait loci (QTL), a potential relationship between differential gene expression and phenotypic changes was also found. In addition, a regulatory network involving circadian-rhythms and light signaling pathways was also found, as previously reported in Arabidopsis, which suggest that such a network might also be related with heterosis in hybrid rice. Altogether, the present study provides another view for understanding the molecular mechanism underlying heterosis in rice.

Keywords: Heterosis, super-hybrid rice, transcriptional profiling, photosynthesis, carbon fixation, regulatory network

INTRODUCTION

Heterosis, or hybrid vigor, refers to the phenomenon that the hybrid of two inbred lines shows superior performance than either parents and is a widely documented phenomenon in diploid organisms that undergo sexual reproduction. The tremendous impact of heterosis in rice breeding in China has resulted in a significant increase in productivity in the last three decades (Cheng et al., 2007). Now, the acreage of hybrid rice takes more than half of the total rice area in China and superior hybrid rice has been showing a increasing contribution to the grain yield (Normile, 2008). Given its importance in breeding programs to world food security, considerable interest has been focused on how heterosis contributes to increased yield trait in hybrid crops.

Two hypotheses, the dominance (Bruce, 1910) and over-dominance hypotheses (East, 1936), have been proposed to explain the phenomenon of heterosis. However, they were coined before the molecular concepts of genetics were well understood and were not connected with molecular genetic principles (Birchler et al., 2003). Since the late 1980s, investigations of heterosis using molecular markers and quantitative trait loci (QTL) have yielded evidence for both the dominance (Xiao et al., 1995) and the over-dominance (Stuber et al., 1992) hypotheses. Since most phenotypic variations are regulated by many loci and changes in each responsible gene may influence traits by interacting with other genes, epistasis was also considered one of the genetic bases of heterosis (Yu et al., 1997). Heretofore, the consensus on the mechanism of heterosis was that no one hypothesis holds true for every phenomenon or every organism (Hochholdinger and Hoecker, 2007).

Recently, with the development of functional genomics, comparative gene expression profiling between hybrid triads has been studied in Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2006), maize (Swanson-Wagner et al., 2006), rice (Song et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2009), and Medicago sativa (Li et al., 2009) by high-throughput gene expression profiling. These studies indicated that in hybrids, the expression of many genes does not exhibit the expected mid-parent value, and some potential association between differential gene expression and heterosis was suggested; for example, differential expression in genes involved in CO2 assimilation (Bao et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2002) and energy metabolism (Wei et al., 2009) could be related to improved production in hybrid rice.

There were also other reports studying heterosis from different aspects. It was reported that allelic variation in gene expression may have an impact on hybrid vigor in maize (Guo et al., 2004; Springer and Stupar, 2007). In rice, the combined interplay between expression of transcription factors and polymorphic promoter cis-regulatory elements in hybrids was indicated as a plausible molecular mechanism underlying heterotic gene expression and heterosis (Zhang et al., 2008). Gene expression profiling in Arabidopsis had suggested that genes involved in the circadian rhythm, such as LHY and CCA1, both MYB-like transcription factors, are associated with heterosis (Ni et al., 2009). Epigenetic modification and small-RNA-directed gene regulation were also shown to be related to heterosis (Ha et al., 2009; He et al., 2010).

To date, despite the development of next-generation high-throughput sequencing technology, such as 454 and Solexa (von Bubnoff, 2008), serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and microarray are still effective tools in transcriptional profiling (Aya et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009). Previously, we investigated the transcriptome profiles of super-hybrid rice LYP9 and its parents by whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray (Wei et al., 2009). Here, we report our further research into transcriptional and physiological metabolism changes in another super-hybrid rice combination, Liangyou-2186 (SE21s × Minghui86). Furthermore, we also found that differentially expressed genes (DGs) between hybrid and parents can be involved in certain regulatory networks, which suggested that complicated gene networks might be underlying heterosis. Results of the present study might help promote further understanding of mechanisms underlying heterosis.

RESULTS

SAGE Library Construction and Differential Expression Analysis

Leaves from the super-hybrid rice LY2186 and its parental lines at grain-filling stage were used as raw materials for the construction of SAGE library. Three SAGE libraries of 207 266 tags were obtained, comprising 69 102, 69 110, and 69 064 tags from the male-sterile line SE21s, the restorer line Minghui86 (MH86), and the F1 hybrid Liangyou-2186 (LY2186), respectively, which corresponded to 20 434, 19 122, and 21 751 unique tags in SE21s, MH86, and LY2186; they combined to form the total 41 776 unique tags (Figure 1A and Table 1). According to the SAGE principle, the 41 776 unique tags were used for alignment with the 10-base virtual tags extracted from the 3'-downstream sequences following the last NlaIII site (CATG) of full-length cDNAs (FL-cDNA) in the Knowledge-based Oryza Molecular biological Encyclopedia (KOME) (Kikuchi et al., 2003). Altogether, 10 907 tags perfectly matched the FL-cDNA sequence and were defined as being annotated (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE) Libraries and Differentially Expressed Tags.

(A) Venn diagram of tags shared among three SAGE libraries.

(B) Venn diagram of tags with significant differential expression (P < 0.05) between LY2186 and its parental lines.

(C) Expression patterns of tags with significant differential expression (P < 0.05) between F1 hybrid and parents.

AHP, above high-parent; HPL, high-parent level; MPL, mid-parent level; LPL, low-parent level; BLP, below low-parent.

Table 1.

Number of Unique Tags in SAGE Libraries of LY2186 Super-Hybrid Rice Combination.

| Copy numbera |

SE21s |

LY2186 |

MH86 |

Combination |

||||

| Numberc | %d | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| >100 | 52 | 0.25 | 49 | 0.23 | 57 | 0.30 | 207 | 0.50 |

| Matchedb | 46 | 0.66 | 42 | 0.57 | 51 | 0.76 | 164 | 1.50 |

| 11–100 | 771 | 3.77 | 784 | 3.60 | 835 | 4.37 | 2539 | 6.08 |

| Matched | 562 | 8.01 | 563 | 7.64 | 578 | 8.64 | 1662 | 15.24 |

| 2–10 | 6242 | 30.55 | 6587 | 30.28 | 5942 | 31.07 | 13 371 | 32.01 |

| Matched | 3301 | 47.04 | 3551 | 48.18 | 3054 | 45.65 | 5551 | 50.89 |

| Once | 13 369 | 65.43 | 14 331 | 65.89 | 12 288 | 64.26 | 25 659 | 61.42 |

| Matched | 3108 | 44.29 | 3214 | 43.61 | 3007 | 44.95 | 3530 | 32.36 |

| Total | 20 434 | 100.00 | 21 751 | 100.00 | 19 122 | 100.00 | 41 776 | 100.00 |

| Matched | 7017 | 100.00 | 7370 | 100.00 | 6690 | 100.00 | 10 907 | 100.00 |

Category based on the copy number of tags.

Matched refers to the number of unique tags that match full-length cDNAs (Kikuchi et al., 2003).

Number refers to the number of unique tags in each category.

% refers to the proportion of unique tags in each category in total unique tags.

Based on the significance identification of a total of 41 776 unique SAGE tags, 1872 significant differentially expressed tags (P < 0.05) were found between LY2186 and MH86, and 1788 between LY2186 and SE21s; they were combined to yield 2617 differentially expressed tags (Figure 1B). Comparison of gene expression levels between the F1 hybrid and its parents allowed classifying the differentially expressed tags into five expression patterns: above high-parent (AHP), high-parent level (HPL), mid-parent level (MPL), low-parent level (LPL), and below low-parent (BLP). What is interesting is that the dominant expression pattern (HPL and LPL) accounted for the majority (61%) of the total differentially expressed tags (Figure 1C).

FL-cDNA-matched differentially expressed tags were used to map genes from Rice Genome Annotation release 6.1 (Ouyang et al., 2007) and a total of 1294 (49.45%) tags were located. Among these tags, 1142 (88.25%) tags were assigned to single gene (1 versus 1), and 82 (6.34%) tags were those multiple tags that can be assigned to a single gene (n versus 1); altogether, 1183 differentially expressed genes (DGs) were acquired for further analysis. It should be noted that we also found that 70 tags (5.41%) showed ambiguous assignment to multiple genes (1 versus n), which were filtered out in the present study (Supplemental Table 2).

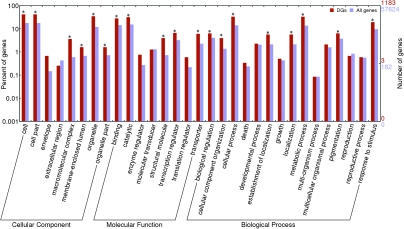

Gene Ontology (GO) slims from the Rice Genome Annotation release 6.1 were used for functional classification of the 1183 DGs by the Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot (WEGO) (Ye et al., 2006) and the results were plotted in Figure 2. Using all genes in the rice genome as background for significance testing, we found that DGs were significantly enriched in six cellular component categories, five molecular function categories, and eight biological process categories (denoted by stars). We further classified DGs at detailed levels based on Gene Ontology (GO) by the Micro Array Data Interface for Biological Annotation (MADIBA) web tool (Law et al., 2008) (Supplemental Tables 3–6). Interestingly, among the 26 significant DG-involved GO terms of cellular component (FDR corrected P-values < 0.05), over 50% were photosynthesis-related, such as photosystem I, chloroplast stroma, chloroplast, thylakoid membrane, and PSII-associated light-harvesting complex II, etc. (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of Gene Ontology (GO) Classification between Differentially Expressed Genes (DGs) and All Genes from the Rice Genome.

The gene ontology slims are from the Rice Genome Annotation (Ouyang et al., 2007). GO terms at level 2 are plotted. Star (*) indicates remarkable relationship, if the P-value is below the significant level of 0.05.

Table 2.

Significant GO Terms of DGs in the GO Annotation Analysis of Cellular Component (FDR-Corrected P-Values < 0.05).

| GO term | Definition | FDR corrected P-valuea |

| GO:0009522 | Photosystem I | 0 |

| GO:0009923 | Fatty acid elongase complex | 0 |

| GO:0030076 | Light-harvesting complex | 8.35E-07 |

| GO:0009570 | Chloroplast stroma | 3.36E-06 |

| GO:0030093 | Chloroplast photosystem I | 1.17E-04 |

| GO:0009507 | Chloroplast | 1.89E-04 |

| GO:0009782 | Photosystem I antenna complex | 5.00E-04 |

| GO:0042651 | Thylakoid membrane | 1.03E-03 |

| GO:0005840 | Ribosome | 1.07E-03 |

| GO:0009579 | Thylakoid | 1.26E-03 |

| GO:0009783 | Photosystem II antenna complex | 3.70E-03 |

| GO:0009538 | Photosystem I reaction center | 3.78E-03 |

| GO:0009517 | PSII associated light-harvesting complex II | 5.42E-03 |

| GO:0009543 | Chloroplast thylakoid lumen | 7.73E-03 |

| GO:0005843 | Cytosolic small ribosomal subunit (sensu Eukaryota) | 1.17E-02 |

| GO:0009328 | Phenylalanine-tRNA ligase complex | 1.83E-02 |

| GO:0005829 | Cytosol | 1.90E-02 |

| GO:0005739 | Mitochondrion | 3.87E-02 |

| GO:0005677 | Chromatin silencing complex | 3.87E-02 |

| GO:0005749 | Mitochondrial respiratory chain complex II | 3.87E-02 |

| GO:0005830 | Cytosolic ribosome (sensu Eukaryota) | 3.87E-02 |

| GO:0005838 | Proteasome regulatory particle (sensu Eukaryota) | 3.87E-02 |

| GO:0009533 | Chloroplast stromal thylakoid | 4.25E-02 |

| GO:0015934 | Large ribosomal subunit | 4.36E-02 |

| GO:0015935 | Small ribosomal subunit | 4.84E-02 |

| GO:0009941 | Chloroplast envelope | 4.91E-02 |

P-values calculated using a hypergeometric test, which determines whether the number of times that a GO term appears in the cluster is significant, relative to its occurrence in the genome (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

The Expression Patterns of Photosynthesis-Related Genes in Hybrid Rice LY2186

To investigate the metabolic pathways in which DGs were involved and enriched, metabolic pathway analysis was performed using the MADIBA web tool (Law et al., 2008), results of which showed that 207 out of 1183 DGs were involved in 12 functional categories (Supplemental Table 7). Among them, the majority were present in carbohydrate metabolism (72 DGs) and energy metabolism (64 DGs). Further analysis demonstrated that these 207 DGs were distributed in 91 out of a total of 141 metabolic pathways. Fisher's exact testing revealed only two metabolic pathways showing extreme significance (P < 0.01): the carbon fixation (P = 5.01E-10) and photosynthesis pathways (P = 6.53E-03) (Table 3 and Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). It should be noted that the starch and sucrose metabolism pathway was the second largest DG-involved pathway, following the carbon fixation pathway, although it does not reach the significant level (Supplemental Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 8).

Table 3.

Top Ten Differentially Expressed Genes (DGs) Enriched in Metabolic Pathways.

| Metabolic pathwaya | No. of enzymesb | No. of genesc | P-valued |

| Carbon fixation* | 18 | 31 | 5.01E-10 |

| Photosynthesis* | 3 | 10 | 6.53E-03 |

| Reductive carboxylate cycle (CO2 fixation) | 5 | 8 | 7.75E-02 |

| Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis | 6 | 7 | 1.02E-01 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 5 | 8 | 1.32E-01 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 6 | 8 | 2.49E-01 |

| Inositol metabolism | 2 | 5 | 3.15E-01 |

| Biosynthesis of ansamycins | 1 | 1 | 3.41E-01 |

| Selenoamino acid metabolism | 5 | 5 | 3.97E-01 |

| Gamma-Hexachlorocyclohexane degradation | 5 | 6 | 4.37E-01 |

Pathway analysis based on MADIBA (Law et al., 2008).

Number of enzymes encoded by DGs in the pathway.

Number of DGs clustered in the pathway.

P-value by Fisher's exact test; the top 10 pathways with P-value are listed; * pathway with P-value < 0.05 is considered as significant.

In the two significant pathways, 27 DGs (encoding 18 unique enzymes) were detected in the carbon-fixation pathway (dark reactions) and 10 DGs (encoding three unique enzymes) in the photosynthesis pathway (light reactions). Interestingly, 20 of the 27 DGs in the carbon-fixation pathway were up-regulated (with expression pattern of AHP or HPL) in F1 hybrid LY2186. As compared with the mid-value of parental lines, in the F1 hybrid, the transcriptional levels of two DGs (Os01g11054 and Os02g14770) encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) were up-regulated by 20- and 4.5-fold, respectively. The gene encoding pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK) and NADP-malate dehydrogenase (NADP-MDH) showed 1.5-fold and 3.5-fold higher expression in F1 hybrid than the mean of the parental lines, respectively. Besides, DGs involved in the Calvin cycle were also found up-regulated expression in hybrid, including genes encoding fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA), sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBP), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP), triosephosphate isomerase (TPI), phosphoribulokinase (PRK), and ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (Rubisco), etc. (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 8).

Table 4.

Transcription Levels of DGs Involved in Carbon Fixation Pathways.

| Gene definition | Locus IDa | Tag | Copy number |

Ratiob | Patternc | ||

| SE21s | LY2186 | MH86 | |||||

| PEPC | Os01g11054 | GCCTTGCCGG | 4 | 9 | 0 | 4.5 | AHP |

| Os02g14770 | ATGAGATGGT | 1 | 10 | 0 | 20.0 | AHP | |

| NADP-MDH | Os08g44810 | CTTCCAGGAG | 2 | 14 | 6 | 3.5 | AHP |

| NADP-ME | Os01g09320 | TGTACCACCA | 42 | 44 | 35 | 1.1 | AHP |

| PPDK | Os05g33570 | GTAATGTACC | 19 | 48 | 44 | 1.5 | AHP |

| PEPCK | Os03g15050 | CGTGTCTGTT | 9 | 11 | 1 | 2.2 | HPL |

| PK | Os10g42100 | GTTCCAATTG | 5 | 7 | 2 | 2.0 | HPL |

| NAD-MDH | Os03g56280 | TAAAATCACT | 19 | 24 | 39 | 0.8 | MPL |

| Os08g33720 | AGGGCGATAA | 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.4 | LPL | |

| Os10g33800 | CCTCAACTAA | 2 | 7 | 0 | 7.0 | AHP | |

| Rubisco | Os12g17600 | TTCGGGTGCA | 6 | 0 | 13 | 0.0 | BLP |

| Os12g19381 | TTCGGCTGCA | 231 | 177 | 142 | 0.9 | MPL | |

| Os12g19470d | CTCTACAACC | 1 | 7 | 0 | 14.0 | AHP | |

| Os12g19470d | TAATATGATG | 328 | 263 | 407 | 0.7 | BLP | |

| PGK | Os05g41640 | TACCATTCTA | 25 | 74 | 34 | 2.5 | AHP |

| GAPDH | Os03g03720 | ACTGTCGAAG | 111 | 211 | 104 | 2.0 | AHP |

| Os04g38600d | TGTAATACCG | 68 | 69 | 100 | 0.8 | MPL | |

| Os04g38600d | TTGCTTGGGA | 349 | 214 | 348 | 0.6 | BLP | |

| TPI | Os01g05490 | TGAGTTTCAG | 43 | 54 | 45 | 1.2 | AHP |

| Os09g36450 | CTGCTGTTCG | 9 | 15 | 6 | 2.0 | AHP | |

| FBA | Os01g67860 | CTATCTTTTT | 3 | 5 | 13 | 0.6 | LPL |

| Os06g14740 | ACTTCAGGAC | 5 | 9 | 3 | 2.3 | AHP | |

| Os11g07020d | AATCTTTTCT | 270 | 581 | 469 | 1.6 | AHP | |

| Os11g07020d | CTTGTGATTC | 339 | 383 | 581 | 0.8 | MPL | |

| FBP | Os03g16050 | CCTACGGAGA | 20 | 20 | 13 | 1.2 | HPL |

| SBP | Os04g16680d | TCAAGGACAC | 21 | 36 | 26 | 1.5 | AHP |

| Os04g16680d | TTGTGCTTCC | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2.6 | HPL | |

| TKL | Os06g04270 | AAGGTCTTGT | 23 | 18 | 9 | 1.1 | MPL |

| RPE | Os03g07300 | TGATACTACC | 98 | 104 | 100 | 1.1 | AHP |

| RPI | Os07g08030 | GCGACTTCGG | 26 | 25 | 11 | 1.4 | HPL |

| PRK | Os02g47020 | AGGGTGCTCC | 81 | 98 | 1 | 2.4 | AHP |

IDs of DGs based on the Rice Genome Annotation (Ouyang et al., 2007).

Ratio = LY2186/[(SE21s+MH86)/2].

Expression pattern: AHP, above high-parent; HPL, high-parent level; MPL, mid-parent level; LPL, low-parent level; BLP, below low-parent.

One locus has more than one tag matched.

Confirmation of Differential Gene Expression

To validate the DG expression involved in carbon fixation and examine whether this result can be extended to other hybrid rice, the expression levels of 14 DGs in the carbon-fixation pathway (Supplemental Table 9) were examined by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in three hybrid rice combinations: Liangyou-2186 (MH86 × SE21s), Liangyou-pei9 (PA64S × 93–11), and Shanyou-63 (ZS97A × MH63). Twelve out of the 14 genes except NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) and Rubisco were confirmed in LY2186 hybrid triads, and all 14 genes were up-regulated in SY63 hybrid triads (Figure 3A and 3C); 11 DGs, with three exceptions (NAD-MDH, TPI, and GAPDH), were confirmed up-regulated expressions in LYP9 hybrid triads (Figure 3B). Altogether, more than 80% of DGs in the carbon-fixation pathway were verified, which demonstrated the satisfactory quality of the SAGE library and the data analysis.

Figure 3.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR of DGs in the Carbon-Fixation Pathway.

(A) Hybrid rice combination LY2186, (B) LYP9, and (C) SY63. Data are means ± SE of three replicates.

Activities Measurement of Enzymes Involved in Carbon Fixation in Hybrid Rice

Although some DGs involved in the carbon-fixation pathway exhibited higher transcription levels in the F1 hybrid than in its parents, the corresponding enzyme activities might not always display a similar trend. To examine whether corresponding photosynthesis enzymes also exhibited higher catalytic activities, activities of PEPC, NADP-MDH, NADP-ME, PPDK, Rubisco, PGK, TPI, FBA, FBP, and RPI in the carbon-fixation pathway were examined in LY2186 hybrid triads. The enzymes including PEPC, NADP-MDH, NADP-ME, PPDK, PGK, and TPI showed significantly increased activity in the F1 hybrid (by 39.79–80.03%, P < 0.01; for PEPC, P < 0.05) (Table 5). These results demonstrated that enzymatic activities were consistent with the corresponding gene expression pattern in the SAGE library.

Table 5.

Activity of Enzymes Involved in Carbon Fixation Pathways.

| Enzymes | Activity (nmol mg−1 min−1)1 |

Activity (nmol min−1 cm−2)2 |

||||

| SE21s | LY2186 | MH86 | SE21s | LY2186 | MH86 | |

| PEPC | 74.19 ± 3.89ab | 95.87 ± 8.06a | 60.60 ± 4.85b | 0.75 ± 0.04ab | 1.04 ± 0.07a | 0.52 ± 0.04b |

| NADP-MDH | 34.55 ± 0.95b | 49.52 ± 0.66a | 20.46 ± 0.72c | 0.35 ± 0.009b | 0.45 ± 0.006a | 0.18 ± 0.006c |

| NADP-ME | 10.95 ± 0.35b | 16.43 ± 0.42a | 10.12 ± 0.89b | 0.11 ± 0.03b | 0.15 ± 0.04a | 0.09 ± 0.01b |

| PPDK | 16.95 ± 0.33b | 30.46 ± 1.21a | 18.98 ± 1.08b | 0.17 ± 0.03b | 0.28 ± 0.01a | 0.16 ± 0.01b |

| Rubisco | 119.05 ± 1.05a | 101.20 ± 2.55b | 97.42 ± 2.49b | 1.20 ± 0.01a | 0.93 ± 0.02b | 0.84 ± 0.02b |

| PGK | 60.88 ± 7.78b | 112.10 ± 9.98a | 99.49 ± 4.47a | 0.61 ± 0.08b | 1.03 ± 0.11a | 0.86 ± 0.04a |

| TPI | 111.33 ± 2.89b | 236.00 ± 11.29a | 197.57 ± 8.40a | 1.12 ± 0.03b | 2.16 ± 0.10a | 1.71 ± 0.08a |

| FBA | 257.15 ± 6.03b | 271.14 ± 5.53ab | 288.54 ± 3.04a | 2.59 ± 0.06b | 2.49 ± 0.05ab | 2.50 ± 0.02a |

| Stromal FBP | 16.78 ± 1.40b | 16.73 ± 2.03b | 37.03 ± 4.35a | 0.17 ± 0.01b | 0.15 ± 0.02b | 0.32 ± 0.01a |

| Cytosolic FBP | 9.92 ± 0.66b | 10.59 ± 1.39b | 17.85 ± 0.57a | 0.10 ± 0.01b | 0.10 ± 0.01b | 0.15 ± 0.01a |

| RPI | 2.09 ± 0.13a | 2.57 ± 0.40a | 1.98 ± 0.30a | 0.02 ± 0.001a | 0.02 ± 0.004a | 0.02 ± 0.001a |

Enzyme activity calculated by 1 unit per mg protein.

Enzyme activity calculated by 1 unit per cm2 leaf.

The data are means ± SE of three replicates. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed by using GraphPad Prism4 software. Different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) in Bonferroni's post tests following an ANOVA.

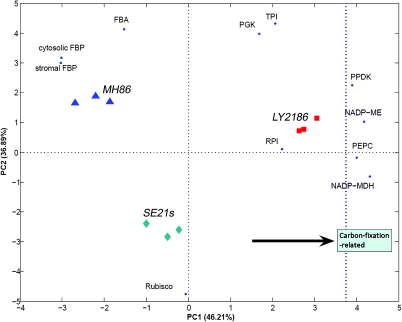

To visualize enzyme activity in the carbon-fixation pathway, principal component analysis (PCA) (Jolliffe, 2002) was performed with a BIPLOT analysis (Figure 4), by plotting the objects (rice lines) and variables (enzymes) in the same plot to enable direct interpretation of the observed effects. The result showed that the similarity between parents was higher than that between the F1 hybrid and either parent during the grain-filling stage. The direction in the plot from the parents towards the F1 hybrid line directly reflects an increase in activity of four enzymes—PEPC, NADP-MDH, NADP-ME, and PPDK—which confirms transcript-level observations and might strengthen our deduction that these enzymes play an important differentiating role in the F1 hybrid.

Figure 4.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Enzyme Activity Patterns in LY2186 Combination.

BIPLOT visualization of PCA of enzyme activity patterns of the carbon-fixation pathway. The rice lines are indicated in red (LY2186), green (SE21s), or blue (MH86), and the contribution of the enzymes to positioning in the plot is provided. The two parent lines (MH86 and SE21s) are more similar to each other than either to the hybrid line (LY2186). The positioning of the hybrid line towards the right side of the plot (indicated by an arrow) underpins the increase in the carbon-fixation-related enzyme activity as compared with its parents.

Examination of Photosynthetic Rate in Hybrid Rice

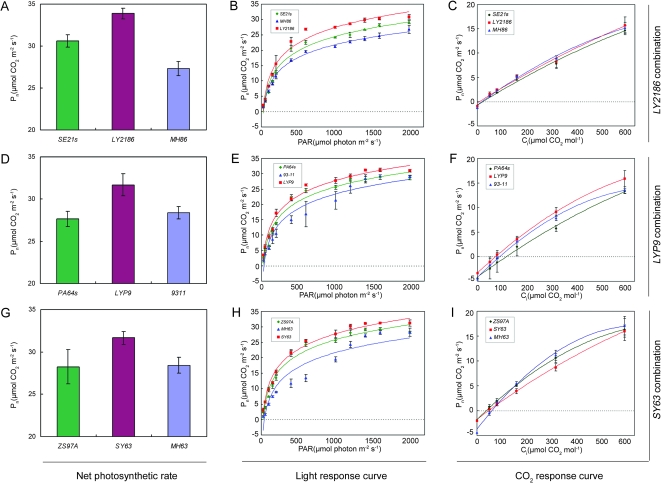

Furthermore, to check whether the up-regulated gene expression and increased enzymatic activity can lead to physiological changes in hybrid rice or not, we examined photosynthetic characteristics of the flag leaf at the grain-filling stage in three hybrid rice combinations: LY2186 (MH86 × SE21s), LYP9 (PA64s × 93–11), and SY63 (ZS97A × MH63). As compared with the average photosynthetic level of the parental lines, all three F1 hybrids showed higher net photosynthetic rates (Pn) in flag leaves, by 10.4, 11.3, and 11.7%, respectively (Figure 5A, 5D, and 5G). More detailed measurements of Apparent Quantum Yields (AQY)—the slope of linear low light part (<200 μmol m−2 s−1) of the light response curves—showed a significant improvement in apparent quantum yield (by 30.9, 32.1, and 20.7%) in the three F1 hybrids than in the parental lines (Figure 5B, 5E, and 5H). We can also see that all three F1 hybrid rice lines showed a lower CO2 compensation point than that of their parents (LY2186 and LYP9, Figure 5C and 5F) or the mid-parent value (SY63, Figure 5I).

Figure 5.

Comparisons of Photosynthesis Characters in Three Hybrid Rice Combinations.

(A–C) Photosynthesis characters of hybrid rice combination Liangyou-2186, (D–F) Liangyou-pei9, and (G–I) Shanyou-63. (A, D, G) Net photosynthetic rate (Pn); (B, E, H) light response curve; (C, F, I) CO2 response curve. PAR, photosynthetic activity rate; Ci, CO2 concentration. Data are means ± SE of three replicates.

Mapping DGs to Yield-Related QTL of Small Intervals

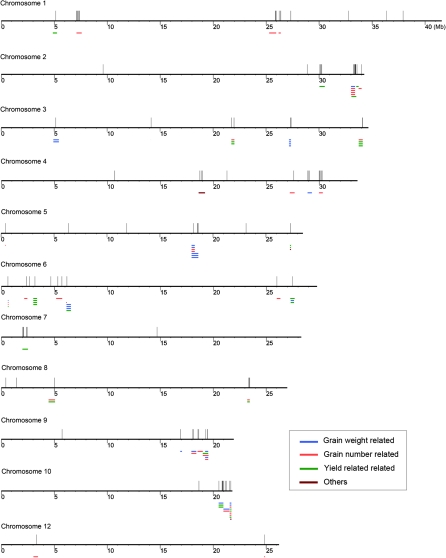

QTL are intervals across a chromosome identifying a particular region of the genome as containing one or more genes associated with the trait being measured. To survey the association between gene expression variation and phenotypic changes in hybrid triads, we mapped DGs to rice QTL collected by Gramene (www.gramene.org). We were able to map 1158 of 1183 (97.9%) DGs to 3017 QTL, which could be classified into nine categories, including Yield, Vigor, Quality, etc. Hybrid rice is superior to its parents mainly in yield, so we further investigated the QTL of the yield category and found 1101 DGs (93.1%) could be mapped to 785 yield-related QTL, many of which are well characterized, such as seed weight, seed number, and filled grain number, etc. (Supplemental Table 10). More interestingly, we found that DGs could be mapped to QTL of small intervals (spanning no more than 100 genes) and 110 DGs (9.3%) were found located in 173 yield-related QTL of small intervals (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Distribution of DGs Located in Yield-Category QTL of Small Intervals.

Yield-category QTL of small intervals (number of genes ≤ 100) that harbor DGs were aligned with the gene coordinates in Rice Genome Annotation release 6.1. The long horizontal lines represent the rice chromosomes, the short horizontal lines in different colors QTL intervals, and the short vertical lines DGs.

We further examined the relationship of DGs involved in photosynthesis, carbon fixation, and starch and sucrose metabolism with yield-related QTL and found that quite a few DGs could be mapped to yield-related QTL, including all 10 DGs involved in photosynthesis, 25 out of the 27 DGs involved in carbon fixation, and 13 out of the 15 DGs involved in starch and sucrose metabolism. In yield-related QTL of small intervals, we found six DGs, including three involved in photosynthesis (Os01g46980, vacuolar ATP synthase subunit E; Os02g51470, ATP synthase delta chain; and Os07g05400, ferredoxin-NADP reductase), two in carbon fixation (Os01g67860, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase cytoplasmic isozyme; and Os10g42100, pyruvate kinase isozyme G), and one in starch and sucrose metabolism (Os04g53310, soluble starch synthase 3); all these DGs seemed have good relationships with the QTL they were located in.

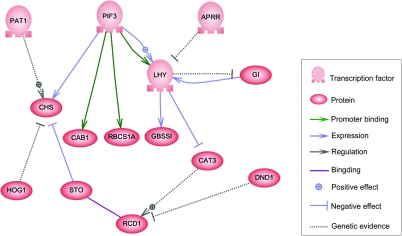

Construction of Regulatory Network in DGs

Genes often interact with other genes to accomplish the whole functions in a cell and these complex gene interactions could contribute to many biological characteristics (Barabasi and Oltvai, 2004). To examine whether some interconnection exists in DGs, we investigated the relationship among DGs using Pathway Studio software (Nikitin et al., 2003) and found a gene regulatory network (Figure 7). This network consisted of circadian rhythm-related genes such as LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY) and GIGANTEA (GI); phytochrome-mediated light signaling-related genes such as phytochrome interacting factor 3 (PIF3), which is involved in the phoytochrome-mediated light signaling pathway, receiving the light signal from photo-activated phytochrome molecules at the first step (Castillon et al., 2007); and stress-tolerance-related genes such as salt tolerance (STO) and radical-induced cell death 1 (RCD1) (Supplemental Table 11). We also found downstream targets of these regulators, such as photosynthesis-related genes ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase small chain 1A (RBCS1A) and chlorophyll a/b binding protein 1 (CAB1), regulated by PIF3; and starch synthesis-related gene, granule-bound starch Synthase I (GBSS1), regulated by LHY. Of note, PIF3 and LHY played a central role in the regulations, facilitating integration in the network.

Figure 7.

Gene Network of DGs in Hybrid Rice by Pathway Studio Analysis.

DGs were used for direct interaction analysis by Pathway Studio 6.2. Interaction searching includes promoter binding, expression, regulation, and binding. APRR, PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR; CAB1, CHLOROPHYLL A/B BINDING PROTEIN 1; CAT3, CATALASE 3; CHS, CHALCONE SYNTHASE; DND1, DEFENSE NO DEATH 1; GBSSI, GRANULE-BOUND STARCH SYNTHASE I; GI, GIGANTEA; HOG1, HOMOLOGY-DEPENDENT GENE SILENCING 1; LHY, LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL; PAT1, PHYTOCHROME A SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION 1; PIF3, PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3; RBCS1A, RUBISCO SMALL SUBUNIT 1A; RCD1, RADICAL-INDUCED CELL DEATH1; STO, SALT TOLERANCE.

DISCUSSION

Despite its critical importance to agriculture, a mechanistic understanding of heterosis has not been achieved. Differential gene expression between the hybrid and its parental cultivars has been hypothesized to contribute to heterosis (Swanson-Wagner et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Song et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2009). In the present study, we attempted to survey the relationship between the transcriptional profiles of gene expression and heterosis in super-hybrid rice LY2186 combination. Comparison of transcriptional profiles of LY2186 showed that of 41 776 detected tags, only 1183 DGs were detected (2.8%), which implied that only a small number of genes were responsible for the changes in phenotypic performance in the F1 hybrid.

Increased Photosynthesis Efficiency in Hybrid Rice

Metabolic pathway analysis demonstrated that DGs were involved in 91 pathways, but were significantly enriched in the carbon-fixation and photosynthesis pathways (P = 5.01E-10 and 6.53E-03, respectively). Photosynthesis, including two phases—light reactions (photosynthesis pathway) and dark reactions (carbon fixation pathway)—is a key process converting CO2 into organic compounds using solar energy (Rascher and Nedbal, 2006). We found 10 DGs involved in the photosynthesis pathway, including six genes encoding F-type ATPase, three encoding ferredoxin-NADP reductase, and one cytochrome b6-f complex-encoding gene, which have important roles in photosynthesis and are responsible for photosynthetic electron transfer in thylakoids (Merchant and Sawaya, 2005). Furthermore, GO annotation analysis of cellular component indicated the DGs significantly enriched in photosynthesis-related organelles. Significant changes in expression patterns of these key genes implied alterations in photosynthetic efficiency.

In the carbon-fixation pathway, our results showed that 20 out of 27 DGs involved in this pathway exhibited higher expression in the F1 hybrid than in its parent (Table 4), which was further validated by qPCR (Figure 3A). These results suggested higher carbon-fixation efficiency in the F1 hybrid than in the parents, which was further supported by significantly increased activity of enzymes in the carbon-fixation pathway (39.79–80.03%) (Table 5). The PCA of enzymatic activities of key enzymes involved in the carbon-fixation pathway provided more evidence that the F1 hybrid had more enhanced carbon fixation efficiency characteristics than its parents (Figure 4). Photosynthetic efficiency testing of flag leaves at the grain-filling stage revealed increases in the net photosynthetic rate (Pn) of 24.1 and 10.6% in the F1 hybrid (LY2186) compared to the maternal (SE21s) and paternal lines (MH86), respectively (Figure 5A). In addition, two other hybrid rice combinations, LYP9 and SY63, also exhibit similar trends based on qPCR (Figure 3B and 3C) and photosynthetic rate testing (Figure 5D and 5G). Of photosynthetic characteristics, the F1 hybrids had higher CO2 assimilation, apparent quantum yield, and lower CO2 compensation points than the parents in all of three hybrid combinations (Figure 5). Increased photosynthetic efficiency has been mentioned in F1 hybrids of rice (Bao et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2007a) and wheat (Yang et al., 2007), and our results explained that increased photosynthetic capability in the F1 hybrid caused by enhanced efficiency in the carbon fixation and the photosynthesis pathway due to the up-regulated genes in the carbon-fixation pathway at both transcriptional level and translational level, which probably play some roles in the formation of hybrid vigor.

It should be noted that genes annotated as PEPC, NADP-MDH, NADP-ME, PPDK, etc., known involved in C4 carbon fixation pathways, were found significantly up-regulated in F1 hybrid than its parental lines. However, rice is known as a C3 plant; even with this result, we are still not sure whether C4 circulation occurred in hybrid rice. Whatsoever, in the tested hybrid rice, the annotated C4 genes’ overall higher expression is a very interesting phenomenon, which may be another way, though not definite at all for now, to help in understanding the mystery of heterosis in rice.

The Roles of Carbohydrate Metabolism and Other Pathways in Heterosis

Besides photosynthesis, other metabolic pathways, such as sucrose and starch pathways, oxidative phosphorylation, citrate cycle (TCA cycle), and stress-resistant pathway, etc., may also contribute to heterosis (Yao et al., 2005). It should be noted that 72 DGs were enriched in carbohydrate metabolism (Supplemental Table 7). In the sucrose and starch pathway, although the P-value was not significant (9.12E-01), it was one of the pathways containing the most DGs (15 DGs) (Supplemental Table 7). Interestingly, we found that the transcriptional expression level of Granule-bound starch synthase I (GBSSI, Os07g22930) was up-regulated, which exhibits circadian oscillation and is controlled by the transcription factors CCA1 and LHY in Arabidopsis (Tenorio et al., 2003). In addition, DGs were also found in the inositol phosphate metabolism pathway, which is considered to play an important role in plant growth, development, and cellular signal transduction (Zhang et al., 2007b). The observation of performance trait also showed that hybrid rice surpassed its parents both in biomass and in harvest index (Table 6). Moreover, LY2186 and LYP9 are both super-hybrid rice cultivars, and exhibited increased harvest indices compared with that of SY63, which is a traditional hybrid rice cultivar, suggesting yield vigor of super-hybrid rice might be related to not only high photosynthesis efficiency, but also other aspects such as distribution efficiency of photosynthetic products.

Table 6.

Comparison of Harvest Index for the Three Hybrid Rice Combinations.

| Rice breed | Biomass. plant−1 (g) | Production increased (%)a | Grain yield. plant−1 (g) | Harvest index | Harvest index increased (%)b |

| SE21s | 40.27 ± 0.77 | 5.57 ± 0.53 | – | ||

| LY2186 | 72.60 ± 1.06 | 19.80% | 23.10 ± 0.57 | 0.32 | 18.52% |

| MH86 | 60.60 ± 1.84 | 16.53 ± 0.55 | 0.27 | ||

| PA64s | 44.08 ± 1.90 | 6.50 ± 0.78 | – | ||

| LYP9 | 48.47 ± 1.30 | 12.40% | 17.13 ± 1.61 | 0.35 | 20.69% |

| 93–11 | 43.12 ± 0.66 | 12.32 ± 1.05 | 0.29 | ||

| ZS97A | 38.97 ± 1.79 | 5.17 ± 0.87 | – | ||

| SY63 | 58.07 ± 1.06 | 32.97% | 17.10 ± 1.03 | 0.29 | 7.41% |

| MH63 | 43.67 ± 1.27 | 11.97 ± 0.61 | 0.27 |

Production increased (%) = (Dry weight of hybrid rice/Dry weight of restorer line – 1) × 100%.

Harvest index (HI) increased (%) = (HI of hybrid rice/HI of restorer line – 1) × 100%.

The data are means ± SE.

DGs Are Associated with Yield-Related QTL

QTL provide links between genotype and phenotype for complex traits, and QTL analysis had been widely used in heterosis study (Garcia et al., 2008; Lippman and Zamir, 2007; Meyer et al., 2010). DGs between F1 hybrid and parents are derived from the heterozygosis of the combined hybrid genomes and may be associated with phenotypic changes in the F1 hybrid. In the present study, we tried to investigate links between DGs, QTL, and heterosis.

Mapping DGs to known QTL revealed about 1158 DGs (97.9%) located in QTL and 1101 (93.1%) in yield-related QTL. Similar results were also obtained in transcriptomic analysis of LYP9 hybrid triads by microarray technology (Wei et al., 2009). More interestingly, in the two significant DG-enriched pathways, carbon fixation and photosynthesis pathways, three DGs encoding vacuolar ATP synthase subunit E, ATP synthase delta chain, and ferredoxin-NADP reductase were involved in the photosynthesis pathway, and two DGs encoding pyruvate kinase (PK) and FBA in the carbon-fixation pathway were located at yield-related QTL.

The potential association among DGs, QTL, and heterosis was also suggested within many QTL regions: examples are soluble starch synthase 3 (Os04g53310) to AQCY010 for filled grain number, photosystem I reaction center subunit psaK (Os07g05480) to AQF079 for grain yield, and fructose-bisphosphate aldolase cytoplasmic isozyme (Os01g67860) to AQFF020 for harvest index. LATE ENLONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY, Os08g06110) (Murakami et al., 2007) can be mapped to yield-related QTL, and a recent report indicated its counterpart was closely associated with heterosis in Arabidopsis (Ni et al., 2009). Interestingly, Os08g06110 can be located to yield-related QTL of small intervals, involved in biomass yield, seed weight, and spikelet number, etc. QTL of small intervals are rather fine-mapped and of increased biological significance. Recently, using a fine-mapping approach, the altered expression of tb1 was characterized as the cause of quantitative phenotypic changes in maize (Clark et al., 2006). Ghd7 was isolated by map-base cloning and considered a crucial factor for increasing productivity of an elite hybrid rice cultivar, Shanyou 63 (Xue et al., 2008).

Implications to Mechanism of Heterosis

In this research, we detected multiple expression patterns of DGs, including dominance (HPL and LPL) and over-dominance (AHP and BLP) (Figure 1C). This suggested that heterosis is a complex issue. It is difficult to decipher its molecular basis using only one hypothesis; related hypotheses such as the dominance (Bruce, 1910), over-dominance (East, 1936), or epistatic hypotheses (Yu et al., 1997) may all contribute to heterosis in rice.

Recently, Ni et al. (2009) reported a model related to circadian rhythms to explain heterosis, in which F1 hybrid and allopolyploid of Arabidopsis gained advantages from the control of circadian-mediated physiological and metabolic pathways. In this model, two key factors, CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) and LATE ENLONGATED HYPOCOTYL(LHY) (Alabadi et al., 2001), were epigenetically modified and repressed in the F1 hybrid and allopolyploid during the day and further induced the expression of downstream genes involved in photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolic pathways. The regulatory network of metabolic pathways involved in circadian rhythms was also reported to increase fitness in animals and plants (Michael et al., 2003; Wijnen and Young, 2006).

By Pathway Studio analysis, we investigated the regulatory network of DGs and finally focused on LHY, a transcription factor of the MYB family, also called OsCCA1 in the case of rice (Murakami et al., 2007). Moreover, another two factors in circadian rhythms, PSEUDO RESPONSE REGULATOR (APRR) (Kaczorowski and Quail, 2003) and GIGANTEA (GI) (Gould et al., 2006), were also included in the network. Meanwhile, LHY is regulated by a transcription factor encoded by a DG (Os01g18290), PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 3 (PIF3), which is involved in the phytochrome-mediated light signaling pathway, receiving the light signal from photo-activated phytochrome molecules at the first step. PIF3 plays an important role in response to light (Castillon et al., 2007). Some DGs involved in photosynthesis, carbon-fixation, starch, and sucrose metabolism pathways could be regulated by the above factors (Dodd et al., 2005), and might result in yield traits vigor and heterosis. As mentioned above, all detected DGs involved in the circadian-rhythm network, including LHY or OsCCA1 (Murakami et al., 2007), could be mapped to yield-related QTL. The similarity of the regulatory network between rice and Arabidopsis may imply that the circadian rhythms regulatory network in hybrid might be one of the molecular mechanisms underlying heterosis in hybrid plants. However, it can not be excluded that the accumulation of small advantages of dominance and over-dominance at a large number of loci in the heterozygotic genome can also contribute to heterosis. Altogether, though the hybrid vigor or heterosis is undoubtedly one of the most complex issues, our findings might provide another view to the understanding the mystery of heterosis.

METHODS

Plant Materials

Three hybrid rice combinations, Liangyou-2186 (super-hybrid rice LY2186 and its parental lines, sterile line SE21s and restorer line MH86), Liangyou-pei9 (super-hybrid rice LYP9 and its parental lines, sterile line PA64s and restorer line 93–11), and Shanyou-63 (traditional hybrid rice SY63 and its parental lines, sterile line ZS97A and restorer line MH63) were planted in the same field. Samples were collected and photosynthesis characters were measured at the same time and under the same environmental conditions.

SAGE Library Construction

Total RNA was extracted from the flag leaves at the grain-filling stage of hybrid rice Liangyou-2186 and its parental lines, SE21s and Minghui86 (MH86), and mRNA was isolated for SAGE library construction using the I-SAGE kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cloned concatemers were sequenced with an ABI3730 auto-sequencer (Perkin–Elmer), and SAGE tags were extracted by the SAGE2000 software. Differentially expressed tags were defined by use of IDEG6 (Romualdi et al., 2003), with the significance threshold set at P < 0.05, on the basis of Audic–Claverie statistics (Audic and Claverie, 1997).

Annotation of SAGE Tags

According to the SAGE principle, 10-bp tags were extracted from the 3'-downstream sequence after the last NlaIII site (CATG) of the FL-cDNAs in KOME (Kikuchi et al., 2003) to generate virtual tags as a reference. Tags in each library of the hybrid rice Liangyou-2186 combination were aligned with the reference for annotation. On the basis of the Rice Genome Annotation release 6.1, tags that matched FL-cDNA clones were mapped to the exact genome locus and annotated gene models (Ouyang et al., 2007). Gene ontology (GO) annotation analysis of DGs was performed by the WEGO (Ye et al., 2006) and MADIBA (Law et al., 2008) web tools.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis of DGs

Analysis of the metabolic pathways of DGs involved was performed using MADIBA (Law et al., 2008). The locus ID of DGs by the Rice Genome Annotation was used for clustering and mapping gene products (enzymes) onto metabolic pathways by use of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) representation (Kanehisa et al., 2004); a P-value was calculated for each pathway by Fisher's exact test.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

The flag leaves at the grain-filling stage of all three hybrid rice combinations were used for total RNA extraction with TRIzol (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis System for RT–PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCR was performed on an MJ Chromo 4 detection system in 96-well reaction plates with parameters recommended by the manufacturer (95°C for 5 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; 72°C for 5 min). Each PCR reaction was performed in triplicate and ACTIN1 as internal control was included (for primers, see Supplemental Table 9). Specificity of the amplification was verified according to the melting curve by Opticon monitor™ analysis software. Statistical analyses involved the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Measurement of Enzyme Activity

Total protein from collected leaf samples was extracted for enzyme activity measurements. Three gram leaf samples were ground to powder in liquid nitrogen and extracted with buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) PVP, 1 mM PMSF, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 15 mM mercaptoethanol), then centrifuged at 15 000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for protein quantification and enzyme activity analysis. Activities of PEPC (Meyer et al., 1988), NADP-MDH (Holaday et al., 1992), NADP-ME (Leegood, 1990), PPDK (Salahas et al., 1990), Rubisco (Ueno and Sentoku, 2006), PGK (Kuntz and Krietsch, 1982), TPI (Gracy, 1975), FBA (Haake et al., 1998), RPI (Domagk and Alexander, 1975), stromal FBP, and cytosolic FBP (Leegood, 1990) were measured according to indicated references. Statistical analyses were performed by GraphPad Prism4 software, using the one-way ANOVA method. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were analyzed by Bonferroni's post tests following an ANOVA. PCA was used for reduction of the dimensionality of the enzyme activity data. Visualization was based on the BIPLOT method after auto-scaling of the data (Jolliffe, 2002). All calculations involved use of Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, USA) and the PLS toolbox (Eigenvector Research, Wenatchee, USA).

Measurement of Photosynthetic Characters

The flag leaves at the grain-filling stages for all three field-grown hybrid rice combinations were measured. Photosynthetic characters from leaf samples of hybrid rice combinations in the grain-filling stage were measured under sunny conditions by a portable photosynthesis analyzer (CIRAS-1 system). The photosynthetic rate, light response curves, and CO2 response curve were calculated and analyzed according to previous methods (Nogues and Baker, 2000). The apparent quantum yield (AQY) for flag leaves was measured under low-light conditions: 0, 25, 50, 100, and 150 μmol photon m−2 s−1.

Mapping DGs to QTL

Rice QTL data with physical positions on the rice genome were acquired from Gramene (www.gramene.org), gene loci, and their coordinates were obtained from Rice Genome Annotation release 6.1. Based on the physical positions of both gene loci and QTL, DGs were mapped to QTL. QTL of small intervals spanning no more than 100 genes were extracted and mapped with DGs in the rice chromosomes.

Regulatory Network Analysis

The gene network of DGs was analyzed by Pathway Studio software (version 6.2) (Nikitin et al., 2003), with the Unigene ID of DGs from NCBI (www.ncbi.nih.gov/) as input for the direct interaction analysis. The regulatory network was constructed by searching the ResNet Plant Database, employing four interaction types, namely promoter binding, expression, regulation, and binding. False interactions and signal genes without interactions with others were removed according to the original references recorded by the software.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at Molecular Plant Online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the grants from the Major Project of China on New varieties of GMO Cultivation (2008ZX08001-001, 2008ZX08012-002), the Research Project on Rice Functional Genes related to the Yield Performance of the High Technology Research and Development Program (863) of China (2006AA10A101), the National Program on Key Basic Research Projects (973) of China (2004CB720406, 2007CB109000), the Innovation Foundation of Chinese Academy of Science (KSCX2-SW-306 and KSCX1-SW-03), the Program for Strategic Scientific Alliances between China and the Netherlands (KNAW-PSA04-PSA-BD-04 for P.B.F.O. and M.W., KNAW-CEP project 04CDP022 for Y.X., and the CAS-KNAW Joint PhD Training Programme (05-PhD-02) for Y.Z. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Major Project of China on New varieties of GMO Cultivation (2008ZX08001-001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Longping Yuan and Huaan Xie for kindly providing the seeds of hybrid rice, Prof. G.E. Edwards for helpful advice, Prof. C.R. Buell and Dr J. Hamilton from the Rice Genome Annotation Project Team for providing helpful information about FL-cDNA related to the gene models from the Rice Genome Annotation, and Prof. Xiujie Wang for support in regulatory network analysis. No conflict of interest declared.

References

- Alabadi D, Oyama T, Yanovsky MJ, Harmon FG, Mas P, Kay SA. Reciprocal regulation between TOC1 and LHY/CCA1 within the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science. 2001;293:880–883. doi: 10.1126/science.1061320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aya K, et al. Gibberellin modulates anther development in rice via the transcriptional regulation of GAMYB. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1453–1472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, et al. Serial analysis of gene expression study of a hybrid rice strain (LYP9) and its parental cultivars. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1216–1231. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Auger DL, Riddle NC. In search of the molecular basis of heterosis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2236–2239. doi: 10.1105/tpc.151030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce AB. The Mendelian Theory of Heredity and the Augmentation of Vigor. Science. 1910;32:627–628. doi: 10.1126/science.32.827.627-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillon A, Shen H, Huq E. Phytochrome interacting factors: central players in phytochrome-mediated light signaling networks. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SH, Zhuang JY, Fan YY, Du JH, Cao LY. Progress in research and development on hybrid rice: a super-domesticate in China. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:959–966. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RM, Wagler TN, Quijada P, Doebley J. A distant upstream enhancer at the maize domestication gene tb1 has pleiotropic effects on plant and inflorescent architecture. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:594–597. doi: 10.1038/ng1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd AN, et al. Plant circadian clocks increase photosynthesis, growth, survival, and competitive advantage. Science. 2005;309:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1115581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagk GF, Alexander WR. D-ribose-5-phosphate isomerase from skeletal muscle. Methods Enzymol. 1975;41:424–426. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)41091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East EM. Heterosis. Genetics. 1936;21:375–397. doi: 10.1093/genetics/21.4.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AA, Wang S, Melchinger AE, Zeng ZB. Quantitative trait loci mapping and the genetic basis of heterosis in maize and rice. Genetics. 2008;180:1707–1724. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould PD, et al. The molecular basis of temperature compensation in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1177–1187. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracy RW. Triosephosphate isomerase from human erythrocytes. Methods Enzymol. 1975;41:442–447. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)41096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Rupe MA, Zinselmeier C, Habben J, Bowen BA, Smith OS. Allelic variation of gene expression in maize hybrids. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1707–1716. doi: 10.1105/tpc.022087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha M, et al. Small RNAs serve as a genetic buffer against genomic shock in Arabidopsis interspecific hybrids and allopolyploids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:17835–17840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907003106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake V, Zrenner R, Sonnewald U, Stitt M. A moderate decrease of plastid aldolase activity inhibits photosynthesis, alters the levels of sugars and starch, and inhibits growth of potato plants. Plant J. 1998;14:147–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, et al. Global epigenetic and transcriptional trends among two rice subspecies and their reciprocal hybrids. Plant Cell. 2010;22:17–33. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholdinger F, Hoecker N. Towards the molecular basis of heterosis. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaday AS, Martindale W, Alred R, Brooks AL, Leegood RC. Changes in activities of enzymes of carbon metabolism in leaves during exposure of plants to low temperature. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:1105–1114. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.3.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe IT. Principal Component Analysis. 2nd edn. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski KA, Quail PH. Arabidopsis PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR7 is a signaling intermediate in phytochrome-regulated seedling deetiolation and phasing of the circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2654–2665. doi: 10.1105/tpc.015065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, et al. Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science. 2003;301:376–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1081288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, et al. The transcriptome of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:8278–8283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz GW, Krietsch WK. Phosphoglycerate kinase from animal tissue. Methods Enzymol. 1982;90 Pt E:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law PJ, Claudel-Renard C, Joubert F, Louw AI, Berger DK. MADIBA: a web server toolkit for biological interpretation of Plasmodium and plant gene clusters. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leegood RC. Enzymes of the Calvin cycle. Methods in Plant Biochemistry. 1990;3:15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wei Y, Nettleton D, Brummer EC. Comparative gene expression profiles between heterotic and non-heterotic hybrids of tetraploid Medicago sativa. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman ZB, Zamir D. Heterosis: revisiting the magic. Trends Genet. 2007;23:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant S, Sawaya MR. The light reactions: a guide to recent acquisitions for the picture gallery. Plant Cell. 2005;17:648–663. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer CR, Rustin P, Wedding RT. A simple and accurate spectrophotometric assay for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase activity. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:325–328. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RC, et al. QTL analysis of early stage heterosis for biomass in Arabidopsis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010;120:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael TP, et al. Enhanced fitness conferred by naturally occurring variation in the circadian clock. Science. 2003;302:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.1082971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Tago Y, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. Comparative overviews of clock-associated genes of Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:110–121. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z, et al. Altered circadian rhythms regulate growth vigour in hybrids and allopolyploids. Nature. 2009;457:327–331. doi: 10.1038/nature07523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin A, Egorov S, Daraselia N, Mazo I. Pathway Studio: the analysis and navigation of molecular networks. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2155–2157. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogues S, Baker NR. Effects of drought on photosynthesis in Mediterranean plants grown under enhanced UV-B radiation. J. Exp. Bot. 2000;51:1309–1317. doi: 10.1093/jxb/51.348.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normile D. Agricultural research: reinventing rice to feed the world. Science. 2008;321:330–333. doi: 10.1126/science.321.5887.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang S, et al. The TIGR Rice Genome Annotation Resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D883–D887. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascher U, Nedbal L. Dynamics of photosynthesis in fluctuating light. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006;9:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi C, Bortoluzzi S, D'Alessi F, Danieli GA. IDEG6: a web tool for detection of differentially expressed genes in multiple tag sampling experiments. Physiol. Genomics. 2003;12:159–162. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00096.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahas G, Manetas Y, Gavalas NA. Assaying for pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase activity: necessary precautions with phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase as coupling enzyme. Photosynthesis Research. 1990;24:183–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00032598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Qu H, Chen C, Hu S, Yu J. Differential gene expression in an elite hybrid rice cultivar (Oryza sativa, L) and its parental lines based on SAGE data. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer NM, Stupar RM. Allelic variation and heterosis in maize: how do two halves make more than a whole? Genome Res. 2007;17:264–275. doi: 10.1101/gr.5347007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber CW, Lincoln SE, Wolff DW, Helentjaris T, Lander ES. Identification of genetic factors contributing to heterosis in a hybrid from two elite maize inbred lines using molecular markers. Genetics. 1992;132:823–839. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.3.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson-Wagner RA, Jia Y, DeCook R, Borsuk LA, Nettleton D, Schnable PS. All possible modes of gene action are observed in a global comparison of gene expression in a maize F1 hybrid and its inbred parents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:6805–6810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510430103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenorio G, Orea A, Romero JM, Merida A. Oscillation of mRNA level and activity of granule-bound starch synthase I in Arabidopsis leaves during the day/night cycle. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003;51:949–958. doi: 10.1023/a:1023053420632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno O, Sentoku N. Comparison of leaf structure and photosynthetic characteristics of C3 and C4 Alloteropsis semialata subspecies. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bubnoff A. Next-generation sequencing: the race is on. Cell. 2008;132:721–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, et al. Genomewide nonadditive gene regulation in Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Genetics. 2006;172:507–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, et al. A dynamic gene expression atlas covering the entire life cycle of rice. Plant J. 2010;61:752–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, et al. Characterization of photosynthesis, photoinhibition and the activities of C(4) pathway enzymes in a superhigh-yield rice, Liangyoupeijiu. Sci. China C. Life Sci. 2002;45:468–476. doi: 10.1360/02yc9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G, et al. A transcriptomic analysis of superhybrid rice LYP9 and its parents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:7695–7701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902340106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnen H, Young MW. Interplay of circadian clocks and metabolic rhythms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006;40:409–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Li J, Yuan L, Tanksley SD. Dominance is the major genetic basis of heterosis in rice as revealed by QTL analysis using molecular markers. Genetics. 1995;140:745–754. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.2.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, et al. Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:761–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, et al. Characterization of photosynthesis of flag leaves in a wheat hybrid and its parents grown under field conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2007;164:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes in leaf and root between wheat hybrid and its parental inbreds using PCR-based cDNA subtraction. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;58:367–384. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-5102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W293–W297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SB, et al. Importance of epistasis as the genetic basis of heterosis in an elite rice hybrid. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CJ, et al. Photosynthetic and biochemical activities in flag leaves of a newly developed superhigh-yield hybrid rice (Oryza sativa) and its parents during the reproductive stage. J. Plant Res. 2007a;120:209–217. doi: 10.1007/s10265-006-0038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H-Y, et al. A genome-wide transcription analysis reveals a close correlation of promoter INDEL polymorphism and heterotic gene expression in rice hybrids. Mol. Plant. 2008;1:720–731. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZB, Yang G, Arana F, Chen Z, Li Y, Xia HJ. Arabidopsis inositol polyphosphate 6-/3-kinase (AtIpk2beta) is involved in axillary shoot branching via auxin signaling. Plant Physiol. 2007b;144:942–951. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.