Abstract

Preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) are pregnancy-specific disorders that share a common pathophysiology. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a transcription factor that plays an important role in placental development. HIF-1α is elevated in preeclamptic placentas and induces soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sFLT-1), a central factor in preeclampsia and IUGR pathogenesis. Our objective was to investigate the effects of HIF-1α overexpression on pregnancy in mice. C57BL/6J pregnant mice were systemically administered either adenovirus expressing stabilized HIF-1α (cytomegalovirus [CMV]-HIF), luciferase control (CMV-Luc), or saline on gestational day 8. Pregnant mice overexpressing HIF-1α had significantly elevated blood pressure and proteinuria compared with pregnant controls. HIF-1α mice showed fetal IUGR, decreased placental weights, and histopathological placental abnormalities compared with control mice. Glomerular endotheliosis, the hallmark lesion of preeclampsia, was demonstrated in the kidneys of these mice relative to the normal histology in control mice. Moreover, liver enzyme levels were significantly elevated, whereas complete blood counts revealed significant anemia and thrombocytopenia in CMV-HIF mice compared with controls. Blood smears confirmed microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in CMV-HIF mice, consistent with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets)-like syndrome. CMV-HIF mice showed elevation in serum sFLT-1 and soluble endoglin, providing a mechanistic explanation for the observations. Collectively, our results suggest a possible role for HIF-1α in the pathogenesis of both preeclampsia and IUGR.

Preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) are major obstetric problems, each affecting 5 to 7% of pregnancies, causing substantial fetal morbidity and mortality. Preeclampsia is characterized by the onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation.1 Advanced-stage clinical symptoms include seizures, renal failure, IUGR, and/or HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome. An effective treatment for preeclampsia is unavailable because of the poor understanding of its pathogenesis; thus, current therapy is restricted to symptomatic treatment, with rapid delivery of the placenta being the only known cure. IUGR, defined as failure of the fetus to achieve its genetically determined growth potential, coexists in approximately 25% of occurrences of preeclampsia.1

Preeclampsia and IUGR are believed to share a common pathophysiology. Both have a component of endothelial dysfunction2 and have abnormal placental implantation in common.2,3 Perhaps the foremost hypothesis regarding the initiating event in preeclampsia and IUGR is that insufficient trophoblast invasion and abnormal spiral artery remodeling lead to placental ischemia.4,5 Recent clinical studies showed elevation of the two circulating antiangiogenic proteins soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFLT-1) and soluble endoglin (sENG) in both preeclampsia6,7 and IUGR.8,9,10 sFLT-1 is a soluble receptor of vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor, whereas sENG is a circulating receptor of transforming growth factor (TGF) β1. Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of either sFLT-1 or sENG under the regulation of the ubiquitous cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter has been shown to result in preeclampsia-like syndrome in pregnant rats, whereas combined overexpression of these two factors produced severe preeclampsia including HELLP syndrome and marked IUGR.11,12 Thus, there is compelling experimental evidence that complements clinical observations that sFLT-1 and sENG play a central role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia/IUGR. Several recent studies have shown that reduced uteroplacental perfusion in animals results in increased sFLT-1 and sENG,13,14,15 thus firmly establishing a causal relationship between placental ischemia and antiangiogenic factor up-regulation. However, the mechanisms underlying the ischemia-induced increase in these factors remain unknown. A candidate molecule that may provide the missing link is hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1).

HIF-1 is a key regulator of the response to low oxygen levels, initiating transcription of numerous genes during hypoxia. It is a heterodimeric transcription factor consisting of subunit α, which is oxygen-sensitive and rapidly degraded and inactivated during normoxia, and subunit β, which is constitutively active. HIF-1α is highly expressed in the low oxygen environment of the placenta in early gestation, playing an important role in placental development and function.16,17 HIF-1α has been shown to be overexpressed in placentas from preeclamptic women,18,19 along with sFLT-1 and sENG.20,21 The soluble receptors sFLT-1 and sENG were also demonstrated to be increased in placentas of IUGR babies.22,23 Moreover, sFLT-1 and endoglin, the membranous counterpart of sENG, have both been shown to be up-regulated by HIF-1α.24,25 Of interest, it was observed that women living at hypoxic high altitude are more likely to develop preeclampsia and/or IUGR than women living at sea level and that their placentas overexpress HIF-1α.26

Although these reports are intriguing, the role of HIF-1α in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia or IUGR is unknown. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of HIF-1α overexpression on pregnancy in mice and determine whether it could induce pregnancy complications resembling preeclampsia and/or IUGR. To this end, we used our previously described adenovirus expressing a constitutively active and stabilized form of HIF-1α under the regulation of CMV promoter27 and studied its effects on pregnant C57BL/6J mice.

Materials and Methods

Adenoviruses

The adenovirus Ad-CMV-HIF, expressing a stabilized and constitutively active HIF-1α form under the regulation of CMV promoter, has been described previously by us.27 It contains a HIF-1α construct bearing the three point mutations P402A, P564G, and N803A, previously termed triple mutant.28 Ad-CMV-Luc (control), expressing the luciferase reporter gene under the regulation of CMV promoter, was purchased from Qbiogene Inc. (Irvine, CA). The adenoviruses underwent large-scale amplification in HEK293 cells, followed by CsCl purification.

Animals

Ten-week-old pregnant or nonpregnant C57BL/6J mice (Harlan Laboratories Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel) were used. Animals were maintained in a temperature-controlled room (22°C) and kept on a 14-hour/10-hour light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Sheba Medical Center. Pregnant mice at day 8 of gestation were randomly divided into three groups and injected systemically via tail vein with either 100 μl of Ad-CMV-HIF (8 × 1010 viral particles) (n = 12), Ad-CMV-Luc (8 × 1010 viral particles) (n = 8), or saline solution (n = 8). Nonpregnant mice were similarly randomized and injected systemically with either Ad-CMV-HIF (n = 7), Ad-CMV-Luc (n = 8), or saline solution (n = 5). Mice were monitored for well-being daily. Urine was collected on day 16 of gestation for albumin and creatinine measurements. Systolic blood pressure was measured on day 17 of gestation. In nonpregnant mice, urine was collected and blood pressure was measured on days 8 and 9 after adenovirus injection, respectively. Mice were sacrificed on day 18 of gestation by CO2 inhalation according to the Animal Care and Use Committee and the American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines. On sacrifice, a median ventral incision was performed followed by blood collection from the vena cava for complete blood count, blood smears, and chemistry analysis. Placentas and fetuses were counted and weighed. Then livers, placentas, lungs, and kidneys were extracted and fixed in PBS-buffered 4% formaldehyde solution for histopathological analysis.

In a second set of similarly treated pregnant mice, blood samples were drawn on days 7, 12, 15, and 18 of gestation from the retro-orbital sinus under light anesthesia with isoflurane inhalation for a few seconds, and circulating levels of sFLT-1 and sENG were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). In nonpregnant mice blood samples were drawn a day before systemic administration and on days 4, 7, and 10 postinjection.

Blood Pressure Measurement

Systolic blood pressure was measured in conscious mice on day 17 of gestation or nonpregnant mice using the tail cuff technique (Narco Biosystems, Houston, TX) as described previously.29 Mice were prewarmed at 37°C for 30 minutes before measurements were taken. The mean of five consecutive readings was recorded as systolic blood pressure.

Urinary Albumin and Creatinine Measurement

Urinary albumin was quantified by ELISA and urinary creatinine was measured by a picric acid colorimetric assay kit (both from Excocell, Philadelphia, PA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The ratio of urinary albumin to urinary creatinine was used as an index of urinary protein.11

Complete Blood Count, Blood Smears, and Chemistry Analysis

Hematocrit, white blood cell count, and platelet count were measured on an LH750 series hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Serum lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase were assayed with an automated analyzer of an enzymatic colorimetric reaction (AU 270, Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) as described previously.27 Peripheral blood smears were prepared and stained with Wright’s stain for detection of schistocytes and reticulocytosis.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

After sacrifice of the mice, placentas, livers, kidneys, and lungs were extracted and fixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight at 23°C. Tissues were infiltrated and embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4-μm thickness), and stained with H&E, Masson’s trichrome or PAS for histopathological analysis. For cytokeratin immunohistochemical staining, tissues were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated, and enzymatic antigen retrieval was performed with trypsin for 10 minutes at 37°C. After blocking, sections were incubated with anti-Pan Cytokeratin Plus antibody (dilution 1:50, Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Detection was performed with the Histomouse SP kit (Zymed Laboratories, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody followed by streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate. After Tris-buffered saline rinses, the antibody binding was visualized with the AEC substrate-chromogen mixture, and the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Kidney samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde buffered in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate at 4°C, followed by treatment with osmium tetroxide for 1 hour and then were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol and embedded in Epon resin at 60°C for 2 days. Ultrathin sections were cut on an ultramicrotome, stained for contrast with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a JEOL-1200 EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Peabody, MA).

Placental Morphometric Analysis

Morphometric analyses of placentas were performed essentially as described previously.30 The new Computer Assisted Stereological Toolbox (newCAST) system (Visiopharm, New York, NY) was used to perform all measurements. All measurements were made on multiple sections taken from a plane in the center of the placenta and perpendicular to its flat side. Morphometric analysis for the estimation of the volume fraction of the decidua, junctional zone, and labyrinth or that of three labyrinthine parameters (fetal vessels, maternal vessels, or trophoblast) was carried out by point counting, and results are expressed as percentages of the total number of points. For this, 64 randomly chosen fields from three different levels of sectioning were used for each of the indicated placental areas assessed. For each treatment group, measurements were performed on three to five placentas.

ELISA for Mouse Serum sFLT-1 and sENG

Mice sera were obtained and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes. ELISAs for mouse sFLT-1 and mouse sENG proteins were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed as described previously.27 In brief, total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated total RNA was subsequently treated with a TURBO DNase kit (Ambion, TX). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 5 μg of total RNA in 20-μl reactions using a SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen) with random hexamers. Real-time PCR amplification was performed for each sample in triplicate in a LightCycler (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using primers and probe sequences designed to distinguish between mouse and human HIF-1α and recognize only human HIF-1α. The forward primer was 5′-CAGTTACAGTATTCCAGCAGACTCAAA-3′, the reverse primer was 5′-CAGTGGTGGCAGTGGTAGTGG-3′, and the TaqMan probe was fam-AAGAACCTACTGCTAATGC. The expression (R) of human HIF-1α (hHIF-1α) mRNA relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was calculated on the basis of the formula, r = 2−ΔCT, where ΔCT = CT, hHIF-1α − CT, GAPDH. Results are expressed as hHIF-1α expression/GAPDH expression. In addition, PCR products were loaded on a denaturing agarose gel.

Statistical Methods

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed with an unpaired Student’s t-test or analysis of variance coupled with a post hoc Tukey’s test for multiple pairwise comparisons. SigmaStat (SPSS Science, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

HIF-1α Transgene Biodistribution Reveals Predominant Expression in the Liver

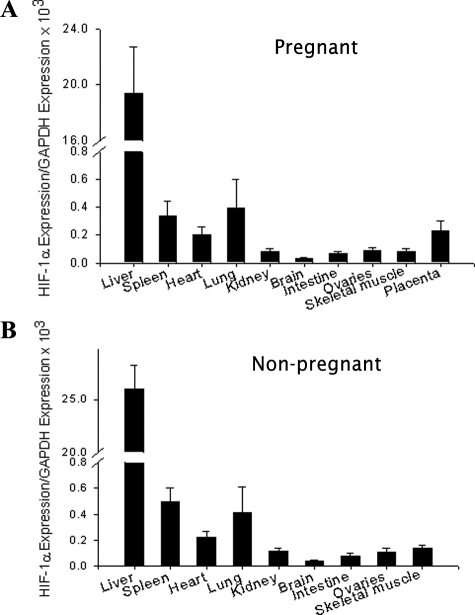

To evaluate the in vivo consequences of HIF-1α overexpression in pregnancy, we injected Ad-CMV-HIF to pregnant mice via the tail vein on day 8 of gestation and to nonpregnant controls. Ad-CMV-Luc and saline were also injected systemically, serving as controls. We initially confirmed adenoviral expression of the human HIF-1α transgene and characterized its biodistribution. For this purpose, various organs were extracted at sacrifice on day 18 of pregnancy, 10 days after injection, followed by quantitative real-time PCR using human HIF-1α-specific probe and primers, thus distinguishing the transgene from endogenous mouse HIF-1α. In both pregnant and nonpregnant mice, HIF-1α transgene mRNA expression was demonstrated predominantly in the animals’ livers (Figure 1, A and B), in agreement with previous findings.27,31 Some expression was also noted in the placentas of pregnant mice. As expected, no transgene expression was detected in any of the control animals injected with either Ad-CMV-Luc or saline.

Figure 1.

HIF-1α transgene biodistribution after systemic administration. A and B: Real-time quantitative PCR of human HIF-1α mRNA expression relative to GAPDH 10 days after systemic administration of adenoviruses in pregnant (A) or nonpregnant mice (B). Expression was evaluated in the liver, lung, spleen, heart, kidney, brain, small intestine, ovaries, skeletal muscle, and placenta. Data for real-time quantitative PCR are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 3 to 4 per group.

HIF-1α Overexpression Leads to Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Placental Abnormalities

To evaluate pregnancy status and fetal development after HIF-1α overexpression, we counted and weighed fetuses and placentas on day 18 of pregnancy. Fetuses of mice injected with Ad-CMV-HIF showed significant growth restriction compared with that of Ad-CMV-Luc- or saline-injected controls, whereas no significant differences were observed in litter size among groups (Table 1). In addition, placentas were significantly smaller in Ad-CMV-HIF-injected mice compared with Ad-CMV-Luc- or saline-injected controls (Table 1). Remarkably, unique pregnancy complications were observed in 25% of Ad-CMV-HIF-treated mice, whereas none were observed in control mice (Table 1). Two mice experienced preterm delivery (on days 12 and 16, respectively), and one had suspected placental abruption (vaginal bleeding on day 16 followed by maternal death 1 day later).

Table 1.

Litter Size and Placental and Fetal Weights at Gestational Day 18 and Obstetric Complications

| Groups | n | No. pups in litter | Placental weight (mg) | Fetal weight (g)* | Obstetric complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | 8 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | 85.8 ± 1.7 | 1.07 ± 0.02 | None |

| CMV-Luc | 8 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 89.6 ± 3.2 | 1.05 ± 0.03 | None |

| CMV-HIF | 12 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 73.2 ± 2.3† | 0.91 ± 0.06† | 25%‡ |

Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Fetal weight is the average weight of the litter for each group.

P < 0.05 compared to the other groups.

Three mice in the CMV-HIF group, which were subsequently excluded from placental and fetal weight calculations, developed obstetric complications. Two mice had premature birth of nonviable fetuses on days 12 and 16; and one had a suspected placental abruption on day 16 and died the following day.

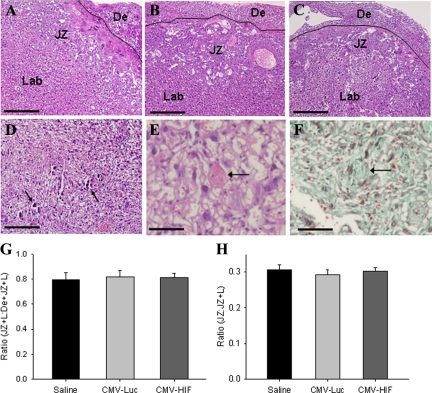

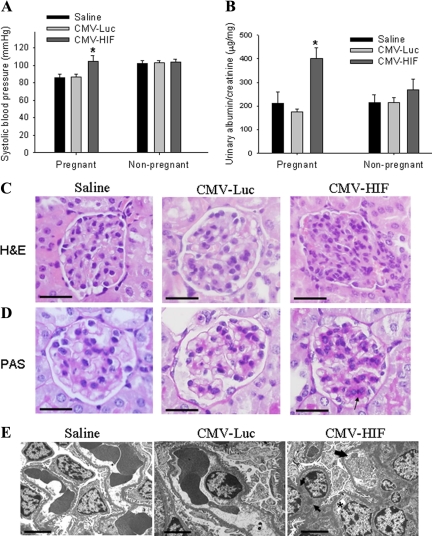

To evaluate further the effects of HIF-1α on the placenta, a combination of histological, immunohistochemical, and morphometric analyses were performed. The major zones of the murine placenta are the fetal labyrinth, junctional zone (containing spongiotrophoblasts, giant cell trophoblasts, and glycogen cells), and maternal decidua. Placental histology demonstrated numerous calcifications within the labyrinth of mice treated with CMV-HIF but not in control mice treated with either CMV-Luc or saline (Figure 2, A–D). Extensive vascular damage, including fibrin thrombi in blood vessel lumens and infarction, was noted in placentas of mice administered CMV-HIF, but not in placentas of control mice (Figure 2, E and F). Morphometric analysis revealed no differences in the relative proportions of decidua, junctional zone, and labyrinth between CMV-HIF and control mice (Figure 2, G and H), indicating that the reduced size of CMV-HIF placentas was not attributable to a change in any particular placental zone. Further analysis of the placental labyrinth of CMV-HIF mice demonstrated a honeycomb appearance, with abnormally dilated fetal and maternal blood vessels (Figure 3, A–F), whereas no cellular or vascular abnormalities were seen in the control mice. In accordance with these findings, morphometric analysis of the labyrinth from CMV-HIF mice revealed an increase in the volume fraction of both fetal and maternal blood vessels compared with controls (Figure 3M).

Figure 2.

Histological and morphometric evaluation of the major placental zones. A–C: Placental histology at gestational day 18 in H&E-stained sections from pregnant mice injected with saline (A), CMV-Luc (B), or CMV-HIF (C). The three placental zones (decidua [De], junctional zone [JZ], and labyrinth [Lab]) are indicated. The solid line shows the border between the decidua and junctional zone. D: Placental section (H&E stain) from CMV-HIF-treated mice showing diffuse calcifications within the labyrinth (arrows). E and F: Placental sections of CMV-HIF-treated mice stained with H&E (E) or Masson’s trichrome (F) showing a thrombus obstructing the lumen of a blood vessel (arrow). G: Morphometric analysis of the fractional volume of the placental disk (JZ + L) expressed as the ratio of the junctional zone plus labyrinth and decidua (De + JZ + L). H: Morphometric analysis of the fractional volume of the junctional zone expressed as the ratio of the junctional zone plus labyrinth (JZ + L). Neither parameter was different among mice groups. n = 3 to 5 placentas for each group. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Scale bars: 100 μm (A–D); 33 μm (E and F).

Figure 3.

Analysis of labyrinth morphology and trophoblast invasion. A–F: Representative images of H&E-stained (A–C) and cytokeratin-stained (D–F) sections of labyrinth at gestational day 18. In contrast with normal labyrinthine architecture in mice injected with saline (A and D) and CMV-Luc (B and E), abnormally dilated fetal and maternal blood vessels were noted in CMV-HIF mice, resulting in a honeycomb appearance (C and F). Arrows point to cytokeratin-positive giant cell trophoblasts, and asterisks indicate blood vessels. G–L: Representative images of cytokeratin-stained placental sections at gestational day 18 showing no apparent differences in invasion of cytokeratin-positive trophoblasts (arrows) into the decidua (G–I) or in their integration into maternal blood vessels (J–L, arrows) among mice injected with saline (G and J), CMV-Luc (H and K), and CMV-HIF (I and L). No differences were noted among groups at gestational day 13 either well (data not shown). The dashed line indicates the border between the decidua (De) and the junctional zone (JZ). n = 3 to 5 placentas for each group. M: Morphometric analysis of the labyrinth demonstrated a significant increase in the volume fraction of maternal and fetal blood vessels with a concomitant decrease in that occupied by trophoblast in CMV-HIF mice compared with that in saline and CMV-Luc mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the other groups. Scale bars: 33 μm (A–C); 20 μm (D–F); 50 μm (G–L).

Reduced trophoblast invasion into the maternal decidua is common to both preeclampsia and IUGR.3 To determine whether CMV-HIF treatment had an effect on the invasive properties of trophoblasts, immunostaining with cytokeratin, a trophoblast-specific cell marker, was used. Two types of invasion by trophoblast cells into the maternal decidua have been described.32 Interstitial invasion refers to glycogen-positive trophoblast cells that show diffuse invasion into the decidua, whereas central invasion refers to invasion of trophoblasts beyond the giant cell layer in the center of the implantation site and usually found in a perivascular location. We assessed the localization of cytokeratin staining within the placenta at gestational days 13 and 18. Diffuse interstitial invasion of cytokeratin-positive trophoblast cells into the decidua was found in all mice groups with no apparent differences (Figure 3, G–I). Likewise trophoblast cell integration into central decidual vessels exhibited no differences among groups (Figure 3, J–L).

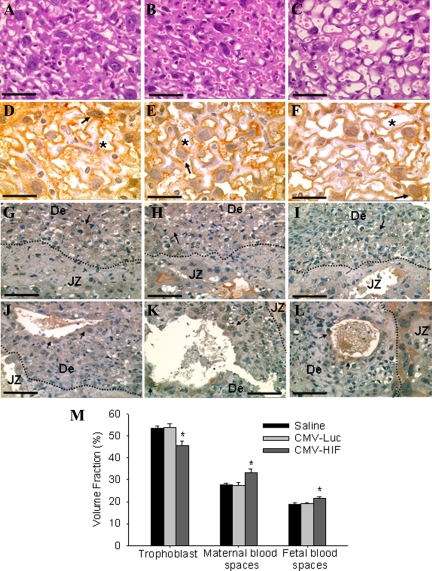

HIF-1α Overexpression in Pregnant Mice Leads to Elevated Blood Pressure, Proteinuria, and Glomerular Endotheliosis

Hypertension is a defining feature of preeclampsia. To determine the effects of HIF-1α overexpression on blood pressure in pregnant mice, systolic blood pressure was measured on day 17 of pregnancy. Systolic blood pressure was significantly elevated in pregnant mice treated with CMV-HIF compared with those treated with CMV-Luc and saline controls (Figure 4A). In contrast, no significant differences were observed between blood pressure of nonpregnant mice treated with CMV-HIF and that of those treated with CMV-Luc and saline (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

HIF-1α overexpression induces blood pressure elevation and renal damage in pregnant mice. Pregnant mice were injected via the tail vein on gestational day 8 with saline (n = 8), CMV-Luc (n = 8), or CMV-HIF (n = 12). Nonpregnant mice were similarly injected with saline (n = 5), CMV-Luc (n = 8), or CMV-HIF (n = 7). A: Systolic blood pressure was measured in pregnant and nonpregnant mice on gestational day 17 and 9 days postinjection, respectively. B: Urinary albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured in pregnant and nonpregnant mice on gestational day 16 and day 8 postinjection, respectively. Urine protein excretion was estimated as the quotient of urinary albumin and urinary creatinine. C and D: Kidney histological sections stained with H&E (C) or PAS (D) showing mesangial cell proliferation and increased mesangial matrix (arrow) in pregnant mice treated with CMV-HIF. These histological changes were not found in mice injected with saline or CMV-Luc. E: Electron microscopic examination of kidney sections demonstrating glomerular endothelial cell swelling and detachment (thick arrow), vacuolization (asterisk), and focal subendothelial deposits (thin arrows) in pregnant mice treated with CMV-HIF in contrast with the normal renal ultrastructure in controls. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the other groups. Scale bars: 50 μm (C and D); 5 μm (E).

HIF-1α-injected pregnant mice were also examined for the presence of proteinuria, another defining feature of preeclampsia, by measuring the ratio of urinary albumin to creatinine on day 16 of pregnancy. Pregnant mice injected with CMV-HIF had a significant twofold increase in urinary albumin compared with saline or CMV-Luc pregnant controls (Figure 4B). However, no significant differences were observed in urinary albumin between CMV-HIF-treated nonpregnant mice and nonpregnant controls (Figure 4B).

Preeclampsia is also associated with characteristic changes in renal histology. The classic lesion of preeclampsia consists of glomerular endothelial swelling with resultant lumen narrowing and obstruction, termed glomerular endotheliosis. To evaluate the potential effects of HIF-1α overexpression on renal pathophysiology, pregnant mice were sacrificed on day 18 of pregnancy, and kidneys were fixed, sectioned, stained, and analyzed by light microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. Light microscopy of kidneys from mice injected with CMV-HIF revealed moderate diffuse mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition within glomeruli (Figure 4, C and D), alterations described in preeclampsia.33 These histological changes were not evident in saline- and Ad-CMV-Luc-treated mice. Electron microscopic analysis of kidneys from CMV-HIF-treated pregnant mice showed glomerular endothelial cell detachment, swelling, and vacuolization (endotheliosis) (Figure 4E). In addition, electron-dense deposits were observed in the subendothelial and mesangial areas. These ultrastructural glomerular lesions were not observed in pregnant saline and CMV-Luc controls (Figure 4E). In contrast to the overt kidney pathology in CMV-HIF-treated pregnant mice, nonpregnant mice treated with CMV-HIF demonstrated no renal histopathological changes, consistent with an absence of blood pressure changes and proteinuria (data not shown).

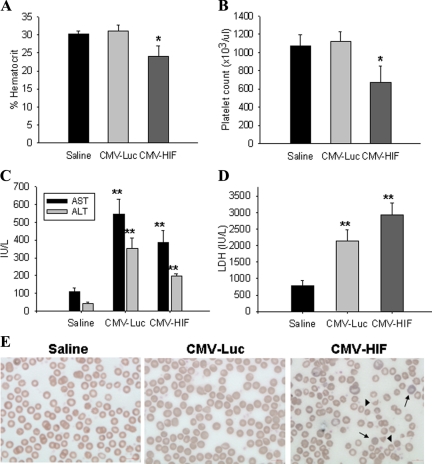

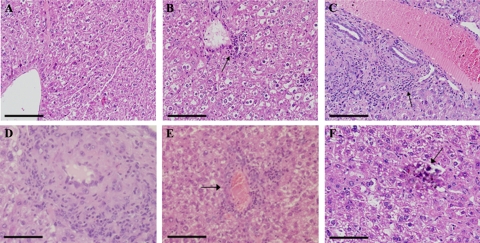

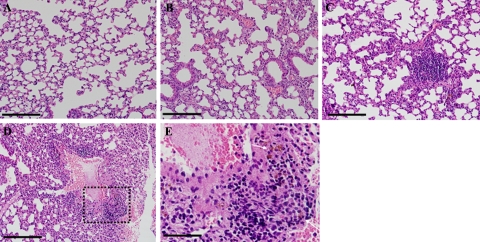

HIF-1α Overexpression Leads to HELLP-Like Syndrome

HELLP syndrome is a subtype of severe preeclampsia.34 HIF-1α-overexpressing pregnant mice were examined for biochemical changes consistent with HELLP syndrome. To this end, results of a complete blood count, a blood smear, and liver function tests were analyzed on day 18 of pregnancy. The complete blood count of pregnant mice injected with Ad-CMV-HIF demonstrated significantly decreased hematocrit levels and platelet counts compared with those of control mice treated with Ad-CMV-Luc or saline, suggesting microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (Figure 5, A and B). Blood smears of pregnant HIF-1α-overexpressing mice revealed numerous schistocytes and marked reticulocytosis, confirming the diagnosis of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, whereas blood smears of control mice showed normal findings (Figure 5E). Serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and lactate dehydrogenase were significantly elevated in both the Ad-CMV-HIF and Ad-CMV-Luc groups compared with saline controls (Figure 5, C and D), suggesting that the liver damage observed in Ad-CMV-HIF may not be due to HIF-1α expression but rather to nonspecific viral hepatitis. However, examination of the liver histology of pregnant mice treated with Ad-CMV-HIF revealed signs of ischemia and extensive vascular damage, including fibrin thrombi (Figure 6, D–F), characteristic findings in HELLP syndrome in humans.35 These histological alterations were not observed after Ad-CMV-Luc treatment (Figure 6B). In contrast, liver histology of Ad-CMV-Luc mice revealed only inflammatory infiltrates, also evident in the Ad-CMV-HIF group, consistent with mild viral hepatitis (Figure 6, A–C). Taken together, these data are consistent with the diagnosis of HELLP-like syndrome in pregnant HIF-1α-overexpressing mice. Furthermore, lung histology of Ad-CMV-HIF-treated pregnant mice revealed diffuse inflammation, vascular damage, and hemorrhage (Figure 7, C–E). These histological changes were not observed in the control Ad-CMV-Luc or saline group (Figure 7, A and B). Nonpregnant mice treated with Ad-CMV-HIF also showed biochemical evidence of HELLP-like syndrome (Figure 8, A–D) and blood smear, liver, and lung histopathological findings similar to those of pregnant mice treated with Ad-CMV-HIF (data not shown). These findings suggest that HIF-1α overexpression is sufficient for the development of HELLP-like syndrome independent of the presence of a placenta.

Figure 5.

Biochemical data and blood smears of pregnant mice. Pregnant mice were injected via the tail vein on gestational day 8 with saline (n = 8), CMV-Luc (n = 8), or CMV-HIF (n = 12). Blood was drawn for complete blood counts, chemistry analysis, and peripheral blood smears on day 18 of pregnancy. A: Percent hematocrit. B: Platelet count. C: Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. D: Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. E: Representative peripheral blood smears (Wright’s stain) of saline-, CMV-Luc-, and CMV-HIF-treated groups, showing reticulocytosis (arrows) and schistocytes (arrowheads) in CMV-HIF-treated mice, which indicates microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. No hemolysis was observed in the other groups. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the other groups; **P < 0.05 compared with the saline control group.

Figure 6.

Histological evaluation of the liver. A–C: Liver histology at gestational day 18 in H&E-stained sections from pregnant mice injected with saline (A), CMV-Luc (B), or CMV-HIF (C). CMV-Luc (B) and CMV-HIF (C) injection resulted in lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates (arrows), whereas no inflammation was observed in the saline-treated control group (A). D–F: Liver sections (H&E) of CMV-HIF-treated mice showing vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis within a blood vessel wall (D) and thrombus with luminal obstruction of a blood vessel (E, arrow), indicating severe vascular damage. Calcifications were also noted (F). Scale bars: 100 μm (A–C); 33 μm (D–F).

Figure 7.

Histological evaluation of the lungs. A–C: Lung histology at gestational day 18 in H&E-stained sections from pregnant mice showing marked inflammatory infiltrates within lung parenchyma of CMV-HIF-treated mice (C), which was not observed in saline-treated (A) and CMV-Luc-treated mice (B). D and E: Lung sections (H&E) of CMV-HIF-treated mice. E: Magnification of the area surrounded by the dashed line in D, showing hemosiderin-laden macrophages (arrows) surrounding a blood vessel, which indicates pulmonary hemorrhage. Scale bars: 100 μm (A–D); 33 μm (E).

Figure 8.

Biochemical data of nonpregnant mice. Nonpregnant mice were injected with saline (n = 5), CMV-Luc (n = 8), or CMV-HIF (n = 7). Blood was drawn for complete blood count and chemistry analysis 10 days postinjection. A: Percent hematocrit. B: Platelet count. C: Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. D: Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the other groups; **P < 0.05 compared with the saline control group.

HIF-1α Overexpression Increases Serum sFLT-1 and sENG

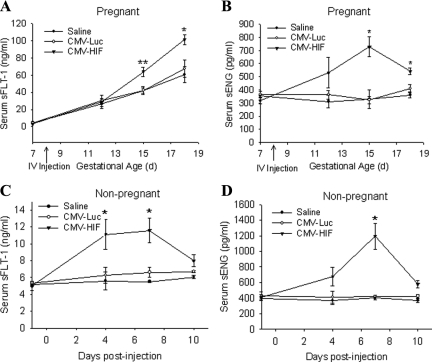

Two factors that are widely implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and IUGR are sFLT-1 and sENG. Hypoxia is known to induce sFLT-1 in trophoblasts, and this effect is mediated by HIF-1α.24 To gain more mechanistic insight into the potential contribution of HIF-1α overexpression to the observed pregnancy complications, we systemically administered mice on day 8 of pregnancy with Ad-CMV-HIF, Ad-CMV-Luc, or saline and measured the serum concentrations of sFLT-1 and sENG a day before injection and periodically thereafter. After injection, the serum sFLT-1 level in pregnant HIF-1α-overexpressing mice increased and was significantly higher on days 15 and 18 of pregnancy relative to that of Ad-CMV-Luc- and saline-treated controls (Figure 9A). Serum sENG in pregnant mice injected with HIF-1α was also elevated over that in Ad-CMV-Luc- and saline-treated mice, reaching a peak twofold difference on day 15 of pregnancy (Figure 9B). Serum sFLT-1 and sENG concentrations were also found to be significantly elevated in nonpregnant mice after injection with Ad-CMV-HIF compared with concentrations in controls (Figure 9, C and D).

Figure 9.

HIF-1α overexpression elevates serum sFLT-1 and sENG levels. A and B: Serum sFLT-1 concentration (ng/ml) (A) and sENG concentration (pg/ml) (B) in pregnant mice injected via the tail vein on gestational day 8 with saline (n = 10), CMV-Luc (n = 11), or CMV-HIF (n = 10), as determined by ELISA. C and D: Serum sFLT-1 concentration (ng/ml) (C) and sENG concentration (pg/ml) (D) in nonpregnant mice injected via the tail vein with saline (n = 4), CMV-Luc (n = 6), or CMV-HIF (n = 9). All data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with the other groups; **P < 0.01 compared with other groups.

Discussion

The present study reveals several novel findings. First, we report that HIF-1α overexpression in pregnant mice induces IUGR, as well as several of the characteristic clinical and pathological findings of preeclampsia, including proteinuria and glomerular endotheliosis. Second, we show that HIF-1α overexpression is sufficient for the development of HELLP-like syndrome and that this effect does not require the presence of pregnancy or the placenta, because it occurred in both pregnant and nonpregnant mice. Third, we demonstrate that HIF-1α up-regulates in vivo expression of the circulating antiangiogenic factors sENG and sFLT-1, two molecules shown to be central in preeclampsia and IUGR pathogenesis.

HIF-1α was previously demonstrated to be overexpressed in preeclamptic human placentas18,19 along with sFLT-1 and sENG.20,21 Soluble FLT-1 and sENG were also shown to be increased in placentas of IUGR babies.22,23 In addition, the sFLT-1 gene possesses a hypoxia-responsive element, to which HIF-1α can bind, and was shown to be up-regulated by hypoxia via HIF-1α in vitro.24 However, the role of HIF-1α in these pregnancy complications remained unknown. Our results show that adenoviral-mediated HIF-1α overexpression in pregnancy leads to IUGR and characteristic preeclampsia manifestations, including proteinuria and glomerular endotheliosis, as well as a HELLP-like syndrome, suggesting a potential role for HIF-1α overexpression in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and IUGR. Indeed, several studies are in strong agreement with an important role for HIF-1α in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and/or IUGR. Gilbert et al14 recently demonstrated increased placental HIF-1α expression in a well characterized animal model of reduced uterine perfusion pressure, in which ischemia leads to preeclamptic manifestations and IUGR. In another recent study, catechol-O-methyltransferase deficiency resulted in a preeclampsia-like phenotype in pregnant mice and was associated with increased placental HIF-1α expression. Notably, administration of 2-methoxyestradiol, the product of catechol-O-methyltransferase activity, in this study ameliorated the preeclamptic manifestations and was associated with a reduction in HIF-1α expression.36

The two circulating antiangiogenic factors, sFLT-1 and sENG, have been shown to be elevated in preeclampsia and IUGR6,7,8,9,10 and are widely believed to play a major role in the pathogenesis of both diseases, yet the precise mechanism leading to their up-regulation is unknown. Various investigators have suggested that oxidative stress, altered natural killer cell signaling, decreased hemoxygenase expression, and angiotensin-1 autoantibodies may be responsible for their up-regulation.37,38,39 Recently, studies showed that ischemia in experimental animals, caused by reduced uteroplacental perfusion, results in increased serum sFLT-1 and sENG,13,14,15 thus firmly linking placental ischemia to up-regulation of these antiangiogenic factors. However, these studies did not elucidate the mechanism underlying the ischemia-induced up-regulation of these antiangiogenic factors. Our results demonstrate that HIF-1α, which is well known to be up-regulated in ischemia and hypoxia, increases both sFLT-1 and sENG concentrations in vivo, providing a potential mechanistic link between placental ischemia and antiangiogenic factor up-regulation.

Although it was previously reported that hypoxia leads to up-regulation of sFLT-1 via the HIF-1α-mediated pathway in vitro,24 the present study is the first to provide evidence for up-regulation of sENG by HIF-1α. In accordance with our results, it was shown that hypoxia induces production of sENG by trophoblast cells from preeclamptic placentas.20 Likewise, Yinon et al,23 recently demonstrated that hypoxia up-regulates placental expression of sENG in villous explants in vitro,23 showing that this hypoxic up-regulation is mediated via TGF-β3. Previously, HIF-1α was shown to be upstream of TGF-β3 in mediating oxygen effects on trophoblast differentiation.17 Taken together, these data suggest that the sENG increase in preeclampsia is likely to be mediated, at least in part, by HIF-1α, probably via a TGF-β3-mediated pathway.

HIF-1α has been reported to have an inhibitory effect on the differentiation of trophoblasts along the invasive pathway via induction of TGF-β3.17 Recently, down-regulation of HIF-1α in cytotrophoblasts by 2-methoxyestadiol was associated with a switch to an invasive phenotype.40 In our analysis, no effect on trophoblast invasion was observed after HIF-1α adenovirus administration in pregnant mice despite expression of our vector in the placenta. This finding could be due to the timing of administration of the HIF-1α-overexpressing vector, in the early second trimester, after trophoblast invasion is already underway. Further studies in which HIF-1α is administered early in the first trimester should clarify this issue, and the effects of HIF-1α on trophoblast differentiation and invasion in vivo could be explored further.

In this study, abnormal vasculature was demonstrated in the placental labyrinth after HIF-1α overexpression, including dilation of fetal and maternal blood vessels with increased blood vessel volume. HIF-1α is a master regulator of angiogenesis, shown previously to induce vascularization in a transgenic mouse model.41 In our model, CMV-HIF-1α was administered on day 8 of gestation, before development of the labyrinth, and thus it is not surprising that it had such an effect on the labyrinth vasculature. Similar blood vessel dilation in the labyrinth was previously described after placental administration of an adenovirus expressing angiopoietin-2,42 a gene well known to be up-regulated by HIF-1α.43 Moreover, placental vascular damage, including thrombosis, was noted in HIF-1α-overexpressing mice. This, however, may not be specific to the placenta and may reflect general maternal vascular damage in HIF-1α mice, because thrombotic microangiopathy, glomerular endotheliosis, and thrombosis in liver blood vessels were also noted in these mice.

In our model, although some HIF-1α transgene expression was noted in the placenta after systemic injection via the tail vein of Ad-CMV-HIF-1α, expression was predominantly in the animal’s liver (100-fold greater), in accordance with well known adenovirus tropism.31,44 Hence, the probable source of increased circulating sFLT-1 and sENG in our model is the liver, which is probably the same source as in previously described preeclampsia models using systemic tail vein injection of adenoviruses expressing sFLT-1 or sENG.11,12 Moreover, the observation that pregnant mice overexpressing HIF-1α had elevated blood pressure and proteinuria accompanied by characteristic preeclamptic renal lesions, whereas nonpregnant mice exhibited no such signs, suggests that blood pressure effects and renal damage in our model required placenta-derived factors in addition to HIF-1α-mediated liver factors. Likewise, Lu et al45 reported hypertension only in pregnant mice after injection of an adenovirus expressing sFLT-1, whereas nonpregnant mice did not develop hypertension. In contrast, Maynard et al,11 showed hypertension, proteinuria, and renal lesions in both pregnant and nonpregnant rats injected with an adenovirus expressing sFLT-1.11 This difference may be attributable to a certain sFLT-1 threshold that has to be reached, shifting the angiogenic:antiangiogenic balance sufficiently for induction of hypertension and kidney pathology. During pregnancy there is a gradual physiological increase in the serum sFLT-1 concentration, which reaches maximal levels at term. Thus, whereas HIF-1α overexpression in our study resulted in sFLT-1 elevation in both pregnant and nonpregnant mice, the maximal sFLT-1 concentration reached in pregnant mice overexpressing HIF-1α was still much higher than the maximal concentration in HIF-1α-overexpressing nonpregnant mice (101 versus 11.5 ng/ml, respectively). The sFLT-1 concentration in our HIF-1α pregnant mice was comparable to that of pregnant mice injected with sFLT-1 in the study by Lu et al (approximately 140 ng/ml). Of note, in the study by Maynard et al, the sFLT-1 concentrations in both pregnant and nonpregnant rats injected with sFLT-1 were higher than 100 ng/ml (388 versus 101 ng/ml, respectively), providing an explanation for the development of kidney damage, hypertension, and proteinuria also in their nonpregnant group and the lack thereof in our study.

In the present study HIF-1α overexpression resulted in signs and symptoms resembling those of HELLP syndrome, a particularly severe subtype of preeclampsia, including hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets, and characteristic liver damage. In contrast to proteinuria and renal damage, which were observed only in pregnant mice, HELLP-like syndrome was observed in both pregnant and nonpregnant mice, suggesting that the HIF-1α-mediated HELLP syndrome was independent of the placenta. A possible explanation for such differences in the placental requirement between HELLP syndrome and proteinuria and renal damage development may lie in different pathogenetic mechanisms. Indeed, Vinnars et al46 recently described differences in placental pathology between mothers with preeclampsia without HELLP syndrome and those with preeclampsia with HELLP syndrome and suggested that different underlying pathogenetic mechanisms may be in play in patients with preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. In a previous study, a HELLP-like syndrome was reported after combined systemic administration of adenoviruses expressing sFLT-1 and sENG in pregnant rats, whereas neither sFLT-1 nor sENG alone was sufficient for its induction.12 Both sFLT-1 and sENG serum levels were elevated after HIF-1α overexpression in our study, probably contributing to the HELLP-like syndrome in the mice. In another study, endothelin infusion was shown to result in a HELLP-like syndrome in nonpregnant rabbits.47 Interestingly, endothelin is also a factor that is up-regulated by HIF-1α.48,49,50 An important area of further research is to identify other HIF-1α-inducible molecules playing a role in our model and determine their relative contributions to the various pregnancy complications.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that HIF-1α overexpression in pregnant mice results in elevation of sFLT-1 and sENG and leads to a wide range of pregnancy complications, including IUGR, preeclampsia-like manifestations, and HELLP-like syndrome, suggesting a potential role for this molecule in the pathogenesis of human preeclampsia and/or IUGR.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yonatan Sharabi for his expertise and assistance with blood pressure measurements. We thank Zahava Shabtai for technical help with blood pressure and urinary albumin and creatinine measurements. We thank Alex Visotsky for advice and assistance with complete blood counts. We thank Livnat Bangio, Hannah Zer-Aviv, and Sharon Mesika for help with adenovirus production.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dror Harats, M.D., Vascular Biogenics Ltd., 6 Jonathan Netanyahu St., Or-Yehuda 60376, Israel. E-mail: dror@vbl.co.il.

R.T., B.F., and D.H. are employees of and A.S. and I.B. are consultants for Vascular Biogenics Ltd., a biotechnology company developing pro- and antiangiogenic gene therapy products.

References

- Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness RB, Sibai BM. Shared and disparate components of the pathophysiologies of fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308:1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1997;37:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, Sibai BM, Epstein FH, Romero R, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner W, Sengenberger R, Strick R, Strissel PL, Meurer B, Beckmann MW, Schlembach D. Angiogenic growth factors in maternal and fetal serum in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:51–57. doi: 10.1042/CS20060161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepan H, Geipel A, Schwarz F, Kramer T, Wessel N, Faber R. Circulatory soluble endoglin and its predictive value for preeclampsia in second-trimester pregnancies with abnormal uterine perfusion, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:175 e171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Nien JK, Espinoza J, Todem D, Fu W, Chung H, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gomez R, Edwin S, Chaiworapongsa T, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. A longitudinal study of angiogenic (placental growth factor) and anti-angiogenic (soluble endoglin and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1) factors in normal pregnancy and patients destined to develop preeclampsia and deliver a small for gestational age neonate. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:9–23. doi: 10.1080/14767050701830480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, Stillman IE, Roberts D, D'Amore PA, Epstein FH, Sellke FW, Romero R, Sukhatme VP, Letarte M, Karumanchi SA. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris A, Thornton C, Thompson J, Thomson S, Martin R, Ogle R, Waugh R, McKenzie P, Kirwan P, Hennessy A. Uteroplacental ischemia results in proteinuric hypertension and elevated sFLT-1. Kidney Int. 2007;71:977–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JS, Gilbert SA, Arany M, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by placental ischemia in pregnant rats is associated with increased soluble endoglin expression. Hypertension. 2009;53:399–403. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JS, Babcock SA, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reduced uterine perfusion in pregnant rats is associated with increased soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 expression. Hypertension. 2007;50:1142–1147. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar A, Conrad KP. Expression, ontogeny, and regulation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors in the human placenta. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:559–569. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia I, Mostachfi H, Winter J, Gassmann M, Lye SJ, Kuliszewski M, Post M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates the biological effects of oxygen on human trophoblast differentiation through TGFβ3. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:577–587. doi: 10.1172/JCI8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar A, Brandon HM, Daftary A, Ness R, Conrad KP. Evidence for the functional activity of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors overexpressed in preeclamptic placentae. Placenta. 2004;25:763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia I, Winter JL. Adriana and Luisa Castellucci Award Lecture 2001. Hypoxia inducible factor-1: oxygen regulation of trophoblast differentiation in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies—a review. Placenta. 2002;23(Suppl A):S47–S57. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Lewis DF, Wang Y. Placental productions and expressions of soluble endoglin, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1, and placental growth factor in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:260–266. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyabalan A, McGonigal S, Gilmour C, Hubel CA, Rajakumar A. Circulating and placental endoglin concentrations in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth restriction and preeclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo O, Many A, Xu J, Kingdom J, Piccoli E, Zamudio S, Post M, Bocking A, Todros T, Caniggia I. Placental expression of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 is increased in singletons and twin pregnancies with intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:285–292. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yinon Y, Nevo O, Xu J, Many A, Rolfo A, Todros T, Post M, Caniggia I. Severe intrauterine growth restriction pregnancies have increased placental endoglin levels: hypoxic regulation via transforming growth factor-β 3. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:77–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevo O, Soleymanlou N, Wu Y, Xu J, Kingdom J, Many A, Zamudio S, Caniggia I. Increased expression of sFlt-1 in in vivo and in vitro models of human placental hypoxia is mediated by HIF-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1085–R1093. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00794.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Elsner T, Botella LM, Velasco B, Langa C, Bernabeu C. Endoglin expression is regulated by transcriptional cooperation between the hypoxia and transforming growth factor-beta pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43799–43808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio S, Wu Y, Ietta F, Rolfo A, Cross A, Wheeler T, Post M, Illsley NP, Caniggia I. Human placental hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression correlates with clinical outcomes in chronic hypoxia in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2171–2179. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R, Shaish A, Rofe K, Feige E, Varda-Bloom N, Afek A, Barshack I, Bangio L, Hodish I, Greenberger S, Peled M, Breitbart E, Harats D. Endothelial-targeted gene transfer of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α augments ischemic neovascularization following systemic administration. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1927–1936. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R, Shaish A, Bangio L, Peled M, Breitbart E, Harats D. Activation of C-transactivation domain is essential for optimal HIF-1α-mediated transcriptional and angiogenic effects. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oron-Herman M, Kamari Y, Grossman E, Yeger G, Peleg E, Shabtay Z, Shamiss A, Sharabi Y. Metabolic syndrome: comparison of the two commonly used animal models. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:1018–1022. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades P, Watkins M, Burton GJ, Ferguson-Smith AC. Roles for genomic imprinting and the zygotic genome in placental development, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4522–4527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081540898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard J, Lochmuller H, Acsadi G, Jani A, Massie B, Karpati G. The route of administration is a major determinant of the transduction efficiency of rat tissues by adenoviral recombinants. Gene Ther. 1995;2:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson SL, Lu Y, Whiteley KJ, Holmyard D, Hemberger M, Pfarrer C, Cross JC. Interactions between trophoblast cells and the maternal and fetal circulation in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2002;250:358–373. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)90773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber LW, Spargo BH, Lindheimer MD. Renal pathology in pre-eclampsia. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;8:443–468. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein L. Syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count: a severe consequence of hypertension in pregnancy. 1982. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.113. discussion 860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton JR, Riely CA, Adamec TA, Shanklin DR, Khoury AD, Sibai BM. Hepatic histopathologic condition does not correlate with laboratory abnormalities in HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:1538–1543. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91735-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanasaki K, Palmsten K, Sugimoto H, Ahmad S, Hamano Y, Xie L, Parry S, Augustin HG, Gattone VH, Folkman J, Strauss JF, Kalluri R. Deficiency in catechol-O-methyltransferase and 2-methoxyoestradiol is associated with pre-eclampsia. Nature. 2008;453:1117–1121. doi: 10.1038/nature06951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore M, Ahmad S, Al-Ani B, Fujisawa T, Coxall H, Chudasama K, Devey LR, Wigmore SJ, Abbas A, Hewett PW, Ahmed A. Negative regulation of soluble Flt-1 and soluble endoglin release by heme oxygenase-1. Circulation. 2007;115:1789–1797. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh SM, Karumanchi SA. Putting pressure on pre-eclampsia. Nat Med. 2008;14:810–812. doi: 10.1038/nm0808-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, Zhang H, Mi T, Popek EJ, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Nat Med. 2008;14:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nm.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, Wong AP, Kanasaki K, Xu Y, Shenoy VK, McElrath TF, Whitesides GM, Kalluri R. Preeclampsia: 2-methoxyestradiol induces cytotrophoblast invasion and vascular development specifically under hypoxic conditions, Am J Pathol. 176:710–720. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson DA, Thurston G, Huang LE, Ginzinger DG, McDonald DM, Johnson RS, Arbeit JM. Induction of hypervascularity without leakage or inflammation in transgenic mice overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2520–2532. doi: 10.1101/gad.914801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva E, Ginzinger DG, Moore DH, Ursell PC, 2nd, Jaffe RB. In utero angiopoietin-2 gene delivery remodels placental blood vessel phenotype: a murine model for studying placental angiogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:253–260. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa M, Liu LX, Date T, Belanger AJ, Vincent KA, Akita GY, Kuriyama T, Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Jiang C. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates activation of cultured vascular endothelial cells by inducing multiple angiogenic factors. Circ Res. 2003;93:664–673. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000093984.48643.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing A, Boileau P, Cauzac M, Challier JC, Girard J, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Comparative in vivo approaches for selective adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to the placenta. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:167–177. doi: 10.1089/10430340050016247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Longo M, Tamayo E, Maner W, Al-Hendy A, Anderson GD, Hankins GD, Saade GR. The effect of over-expression of sFlt-1 on blood pressure and the occurrence of other manifestations of preeclampsia in unrestrained conscious pregnant mice, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:396.e1–396.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.024. discussion 396.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinnars MT, Wijnaendts LC, Westgren M, Bolte AC, Papadogiannakis N, Nasiell J. Severe preeclampsia with and without HELLP differ with regard to placental pathology. Hypertension. 2008;51:1295–1299. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.104844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim A, Kanayama N, Maehara K, Takahashi M, Terao T. HELLP syndrome-like biochemical parameters obtained with endothelin-1 injections in rabbits. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1993;35:193–198. doi: 10.1159/000292699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Discher DJ, Hu J, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Molecular regulation of the endothelin-1 gene by hypoxia. Contributions of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, activator protein-1, GATA-2, and p300/CBP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12645–12653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Discher DJ, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Hypoxia regulates expression of the endothelin-1 gene through a proximal hypoxia-inducible factor-1 binding site on the antisense strand. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:894–899. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchenko A, Caro J. Regulation of endothelin-1 gene expression in human microvascular endothelial cells by hypoxia and cobalt: role of hypoxia responsive element. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;208:53–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1007042729486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]