Abstract

The pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease and diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD) is the aggregation of α-synuclein (α-syn) in the form of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. Patients with both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cortical Lewy pathology represent the Lewy body variant of AD (LBV) and constitute 25% of AD cases. C-terminally truncated forms of α-syn enhance the aggregation of α-syn in vitro. To investigate the presence of C-terminally truncated α-syn in DLBD, AD, and LBV, we generated and validated polyclonal antibodies to truncated α-syn ending at residues 110 (α-syn110) and 119 (α-syn119), two products of 20S proteosome-mediated endoproteolytic cleavage. Double immunofluorescence staining of the cingulate cortex showed that α-syn110 and α-syn140 (full-length) aggregates were not colocalized in LBV. All aggregates containing α-syn140 also contained α-syn119; however, some aggregates contained α-syn119 without α-syn140, suggesting that α-syn119 may stimulate aggregate formation. Immunohistochemistry and image analysis of tissue microarrays of the cingulate cortex from patients with DLBD (n = 27), LBV (n = 27), and AD (n = 19) and age-matched controls (n = 15) revealed that AD is also characterized by frequent abnormal neurites containing α-syn119. Notably, these neurites did not contain α-syn ending at residues 110 or 122-140. The presence of abnormal neurites containing α-syn119 in AD without conventional Lewy pathology suggests that AD and Lewy body disease may be more closely related than previously thought.

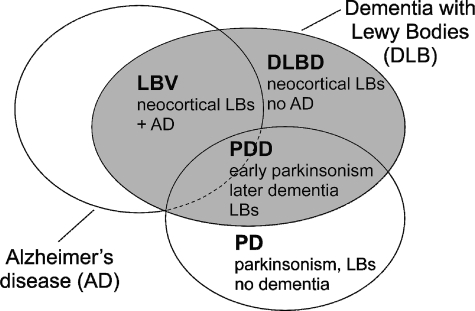

The deposition of aggregated α-synuclein (α-syn) is the pathological hallmark of Lewy body disease, which includes Parkinson’s disease (PD), diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD), and Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease (LBV) (Figure 1). By immunohistochemistry, the aggregated α-syn in Lewy body disease is localized to round cytoplasmic inclusions known as Lewy bodies and to abnormal neurites known as Lewy neurites. Some of the aggregated α-syn in human brain tissue is C-terminally truncated, a modification that has been shown to accelerate oligomer and amyloid formation in vitro.1,2,3 Furthermore, substochiometric amounts of truncated forms can seed the aggregation of the full-length protein,2 which leads to the attractive hypothesis that truncated α-syn contributes to early stages of pathogenesis. Consistent with this hypothesis, production of truncated forms of α-syn correlate with disease and cause PD-like phenotypes in transgenic animals. Truncations of α-syn are present in the insoluble, fibrillary aggregates found in the brains of Lewy body disease patients, but not in aggregate fractions of control brains.2,4 Appearance of truncated α-syn also correlates with pathogenesis in transgenic mouse models of PD.2,3,5 Finally, transgenic mice that express C-terminally truncated forms of human α-syn develop PD-like symptoms and exhibit PD-like neuronal pathology.6,7

Figure 1.

Relationships among Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the three subtypes of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and Parkinson’s disease (PD).26 Parkinsonism refers to the clinical symptoms of PD (hypokinesia, tremor, and muscular rigidity). LBV, Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease; DLBD, diffuse Lewy body disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; LBs, Lewy bodies.

The mechanism that produces truncated α-syn in vivo has not been conclusively identified. Multiple proteases have been shown to cleave α-syn, including the 20S proteasome,2,8 calpain I,9,10 and cathepsin D.11 Previous work in one of our laboratories (P.J.T.) showed that abnormally aggregated α-syn contains at least three truncated α-syn forms in addition to full-length α-syn.2 Although the exact peptide sequence of the three truncated α-syn forms was unclear, epitope mapping indicated that two of these proteins were C-terminally truncated, ending at approximately amino acid residues 102-125 and 83-110, respectively. These two C-terminally truncated proteins had intact N-termini and were consistent with the 1-119, 1-122, and the 1-110 truncations produced by the 20S proteasome in vitro.2 The third truncated α-syn form was both C- and N-terminally truncated and appeared to consist mainly of the central, highly amyloidogenic NAC (non-Aβ component) fragment of α-syn,2 which corresponds to amino acid residues 61-95. The NAC fragment is not associated with the Aβ peptide in AD plaques as originally thought, but it has been suggested that NAC may be present within dystrophic, phospho-τ-immunoreactive neurites surrounding neuritic AD plaques.12 Another study, based on mass spectrometry after trypsin digestion, indicated the presence of C-terminally truncated α-syn ending at amino acids 119, 122, and possibly 123 in the human brain.3 In addition, shorter fragments are present but could not be analyzed due to their low abundance. The C-terminally truncated forms of α-syn were seen in the particulate fractions from Lewy body disease brains but also in the soluble fractions of age-similar control brains and cultured cells.2,3 The 20S core particle of the proteasome is capable of endoproteolytically cleaving α-syn in vitro in a ubiquitin-independent manner,13 producing fragments that are similar to those observed in patient samples and that promote the formation of putative cytotoxic oligomer species.2,3,14

In addition to its central role in the Lewy body diseases, α-syn pathology, excluding amygdala-only pathology, has been observed in 34% of patients with significant concomitant Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology.15 The coexistence of α-syn and AD pathology is known as Lewy body variant of AD (LBV) (Figure 1). In cases with concurrent AD pathology, consisting of aggregated Aβ peptide and abnormally phosphorylated tau (phospho-tau), α-syn pathology is generally much more severe than in cases without AD pathology.16 Interactions that stimulate cross-fibrillization have been identified in vitro between α-syn and Aβ peptide as well as between α-syn and phospho-tau.17,18 Interactions are also suggested at the genetic level, as a specific haplotype of the tau gene increases the risk for Parkinson’s disease.19 In addition to the increased full-length α-syn pathology in LBV, truncated forms of α-syn also appear to be more abundant in cases with concurrent AD pathology.16 Because truncations of α-syn are known to increase amyloidogenicity and a strong possibility for cross-seeding of amyloidogenic proteins exists, the identification of specific truncated α-syn forms may contribute to the understanding of the pathogenesis of not only Lewy body disease but also LBV and AD. Furthermore, the presence of specific truncations may also contribute to the understanding of the complex boundaries between these diseases. Ultimately, accurate clinical distinction between Lewy body disease and AD has direct consequences for treatment, as some medications are contra-indicated for Lewy body disease that are acceptable for use by AD patients.20

Antibodies that specifically recognize truncated forms of α-syn would be useful for high-throughput analyses of both cultured cells and tissues. An approach for the development of antibodies that incorporate the C-terminal carboxylic acid group into the recognition epitope has been previously described.21 In this study, polyclonal antibodies were raised using a similar approach against two forms of truncated α-syn: α-syn ending at amino acids 110 (α-syn110) and 119 (α-syn119). The antibodies, named syn110 and syn119, specifically recognized the corresponding truncated forms of α-syn as evaluated by Western blotting. Both new antibodies detected α-syn pathological aggregates in Lewy body disease, but only α-syn119 aggregates were found to be predominantly colocalized with full-length α-syn. Abnormal neurites containing α-syn119 were detected in AD in the absence of other forms of pathological α-syn.

Materials and Methods

Development of Antibodies to C-Terminally Truncated α-Syn

The peptide antigens corresponded to the last seven amino acids of α-syn110 and α-syn119, respectively (Table 1). Protein BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, last accessed October 16, 2010.) searches showed no significant homology between the peptides and human proteins other than α-syn. To ensure that the C terminus would be available for incorporation into the recognition epitope, an N-terminal cysteine residue was added to the peptide sequence (Table 1). The peptides were then conjugated to the commonly used carrier protein keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) via maleimide chemistry. Immunization of rabbits was contracted to Proteintech Group (Chicago, IL). For each antigen, two rabbits were immunized and preimmune and final bleed sera were collected from each animal. The antisera were affinity purified using columns with immobilized antigenic peptides. The purified antibodies, named syn110 and syn119, were aliquoted and stored at −20°C in 0.02% NaN3.

Table 1.

Synuclein Antibodies

| Antibody designation | Antigen (peptide sequence)/epitope | Type | Clone (catalog number) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syn110 | α-syn aa. 104-110 (N′-CEEGAPQE*) | Rabbit polyclonal | N/A | This study |

| Syn119 | α-syn aa. 113-119 (N′-CLEDMPVD*) | Rabbit polyclonal | N/A | This study |

| Syn122-140 | α-syn aa. 115-122† | Mouse monoclonal | LB509 | Invitrogen |

| Syn140 | C-terminus of α-syn (aa. 130-140) and β-syn | Mouse monoclonal | Syn 202 | Abcam |

| N-ter syn | N-terminus of α-syn and β-syn | Rabbit polyclonal | GTX15534 | GeneTex |

| Pan-synuclein | α-syn aa. 83-100‡ | Mouse monoclonal | 42/α-Synuclein (610786) | BD Transduction Laboratories |

Immunoblotting of Recombinant Truncated and Full-Length α-Syn

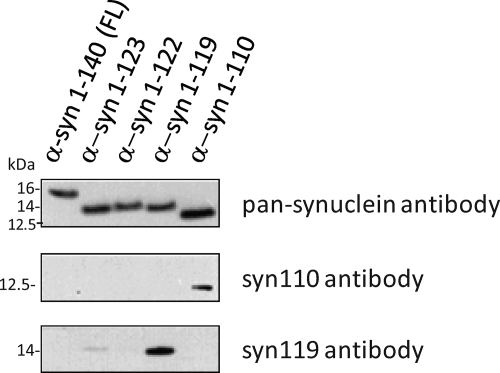

The generated polyclonal antibodies were validated against the intended targets using recombinantly expressed and purified truncations of α-syn in an immunoblot assay (Figure 2). Recombinant α-syn proteins were expressed and purified as described.2 Because these truncated proteins have a tendency to aggregate during storage, solutions of the recombinant proteins were filtered to reduce the amount of protein aggregates immediately before loading the gel. A 30-μL aliquot of each recombinant protein was applied on a Microcon YM-100 filter column (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Of the flow-through, 10 μl was dissolved in 30 μl of 8M guanidine hydrochloride (final concentration, 6M) and used for determination of protein concentration with the Micro BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), while the remaining flow-through was used for immunoblotting. Each recombinant protein, 200 ng/lane, was suspended in NuPage LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 50 mmol/L dithiothreitol, heated at 70°C for 10 minutes, and loaded on NuPage 10% Bis-Tris gel. After electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose, the membranes were exposed to the syn110 or syn119 antibody diluted 1:2000 in Tris-buffered saline with 1% milk and 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 hour at RT and then to peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (H+L) (#32460, Thermo) diluted 1:3000. The signal was detected using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo) and CL-XPosure film (Thermo). The membrane was then stripped using Restore Western blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo) and reprobed with the pan-synuclein antibody (Table 1) diluted 1:2000.

Figure 2.

Specificity of the syn110 and syn119 antibodies to C-terminally truncated α-syn ending at amino acids 110 (α-syn110) and 119 (α-syn119), respectively (immunoblot of recombinant α-syn proteins).

Autopsy Brain Samples and Neuropathologic Examination

Samples of human brain tissue were obtained from the Neuropathology Core of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern). At autopsy, one of the cerebral hemispheres was sectioned coronally at 1-cm intervals. The slabs were placed in plastic bags and stored at −80°C. The other hemisphere was fixed in formalin and sampled for paraffin sections. Approximately 0.5 grams of frozen cortical tissue was dissected from the anterior cingulate gyrus and used for biochemical studies. A signed consent for brain autopsy had been obtained from the next of kin or legal representative in each case. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UT Southwestern, based on federal regulations (45CFR 46), has determined that studies using autopsy tissue are not considered “human research” and therefore no IRB approval is required. Brain autopsy cases of AD, DLBD, LBV, and controls were selected for this study based on availability. The diagnosis of AD was based on densities of neuritic plaques, detected using a modified thioflavin S stain,23 meeting the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) criteria for “definite AD”.24 Seventeen of the 19 AD cases selected in this manner had a Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage25 of at least V, and the remaining two cases had a Braak stage of IV. The diagnosis of DLBD (n = 27) was based on meeting the criteria for “neocortical stage” of Lewy body disease according to the Third Report of the Dementia with Lewy bodies Consortium (Third Consortium),26 not meeting the CERAD neuritic plaque criteria for “definite AD,”24 and not having a Braak tangle stage higher than IV.25 The diagnosis of LBV (n = 27) was based on meeting the Third Consortium “neocortical stage” criteria of Lewy body disease and also meeting the CERAD “definite” criteria for AD. The widely-used CERAD criteria were chosen because they emphasize neuritic plaques, a type of senile plaques, and previous evidence suggests that Aβ deposition in the form of senile plaques is associated with enhanced cortical α-syn lesions in Lewy body disease.16 Age-similar controls (n = 15) had no clinical history of dementia or cognitive impairment, met the CERAD criteria for a normal control, had a CERAD age-related neuritic plaque score of at most “A,” and had a Braak stage of at most II. The mean ages for the AD, DLBD, LBV, and control groups were 73, 78, 77, and 78 years, respectively; the differences were not statistically significant by analysis of variance. Six cases of Parkinson’s disease (PD), defined as clinical parkinsonism without dementia and with α-syn pathology at autopsy,27 were identified based on availability and included in the study. The PD cases were obtained through the Dallas County Medical Examiner’s Office. Because the average age in the PD group (62 years) was lower than that in the other groups and also because of the relatively low number of cases in this group, the PD group was analyzed only qualitatively and separately from the other groups.

Fractionation and Immunoblotting of Human Brain Tissue

Visible white matter and leptomeninges were dissected from the cortical brain sample. The sample was weighed and suspended in 2% (for subsequent immunoblotting using the syn110 antibody) or 4% (for syn119 antibody) SDS (3 ml of buffer for 1 g of tissue) with 20 mmol/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.6), and Complete Mini EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (one tablet/10 ml; Roche). The sample was dissolved by sonicating six times for 15 seconds while the tube was immersed in an ice bath, pausing for 15 seconds between the periods of sonication, using a Microson Ultrasonic Cell Disruptor (Misonic, Farmingdale, NY) at 50% duty cycle and power output level 2. The samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g (78,000 rpm, 15–20 psi) for 30 minutes at RT using an A-100/18 rotor in an Airfuge ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). The supernatant was retained as the SDS fraction. The pellet was washed once with SDS buffer and centrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 30 minutes. The pellet was dissolved in 8 mol/L urea buffer (1.5 ml/g of original sample weight) with 4% SDS, 4% CHAPS, 20 mmol/L NaCl, and 20 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.6). The sample was sonicated once for 15 seconds at the same settings as stated above and centrifuged at 15,000 × g (13000 rpm) for 15 minutes using an Eppendorf 5415C centrifuge (Beckman Coulter). No visible pellet was observed. The supernatant was retained as the urea fraction. For immunoblotting, 6 μl of the SDS fraction and 12 μl of the urea fraction were suspended in NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) with 50 mmol/L dithiothreitol. The final volume was brought to 20 μl with distilled water. The SDS fraction sample was heated to 70°C for 10 minutes, whereas the urea fraction sample was held at RT for 10 minutes before loading on NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gel. The protein size standard was Novex Sharp Unstained Protein Standard (Invitrogen). NuPAGE antioxidant (0.5 ml) was added in the inner chamber of the electrophoresis apparatus. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membrane, which was then stained reversibly for total protein with Ponceau S (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to ensure equal loading. The membrane was blocked for 1 hour in 10% milk and 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS at 4°C before exposure to the primary antibody diluted in 1% milk and 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS for 1 hour at RT with gentle shaking. The dilutions of the primary antibodies syn110, syn119, syn140, and pan-synuclein (Table 1) were 1:200, 1:200, 1:1000, and 1:500, respectively. Depending on the primary antibody, the secondary antibody was either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (H+L) (#32460, Thermo) or anti-mouse (H+L) (#32430, Thermo), both diluted 1:3000. The signal was detected using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo) and CL-XPosure film (Thermo). To provide an additional loading control, the lanes with SDS fractions were stripped and reprobed with an antibody to neuron-specific enolase (#18-0196, Invitrogen), diluted 1:200. For negative control experiments with preabsorbed primary antibody, an aliquot of the primary antibody was incubated with a 100-fold molar excess of the antigenic peptide resuspended in distilled water with 2 mmol/L DTT for 30 minutes with gentle shaking at RT. A positive control experiment was performed in parallel and in the same way except that the antigenic peptide was omitted.

Tissue Microarrays

Cores for tissue microarrays (TMAs) were punched using a tissue microarrayer (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI). The donor blocks were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from the anterior cingulate cortex of 88 autopsy brains: 19 AD, 27 DLBD, 27 LBV, and 15 age-similar controls. The tissue cores (1.5 mm) were taken from approximately the middle of the cortical thickness, which measured 3 mm on average. Thus, the cores included cortical layers III-V. Lewy neurites containing full-length or truncated α-syn were distributed approximately equally among the cortical layers, whereas Lewy bodies were most frequent in layers III and V.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections from tissue arrays of human anterior cingulate cortex were cut at 4 μm thickness, deparaffinized, and placed in a Pascal programmable pressure cooker (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) containing Reveal solution (Biocare Medical, Walnut Creek, CA), with the target temperature and time set to 125°C and 30 seconds, respectively. Diagnostic immunohistochemistry for phospho-tau included an additional antigen retrieval step consisting of incubation in 98% formic acid for 5 minutes, which was followed by exposure to a 1:200 dilution of the AT8 antibody (Thermo). For immunohistochemistry with the syn110, syn119, syn122-140 (LB509), and N-ter syn antibodies (Table 1), unless specified otherwise, the sections were pretreated with proteinase K (#53020; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 15 minutes before incubation in a 1:200, 1:200, 1:80, or 1:100 dilution of the primary antibody, respectively, for 30 minutes. at room temperature (RT). For the negative control experiment with a preabsorbed primary antibody, an aliquot of the primary antibody was incubated with a 100-fold molar excess of the antigenic peptide resuspended in distilled water with 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol for 30 minutes with gentle shaking at RT. A positive control section for the pre-absorption experiment was treated similarly except that the antigenic peptide was omitted. The signal was detected with the alkaline phosphatase-based ultraView universal detection system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), and the chromogen was either the Fast Red/Naphthol (syn110, syn119, syn122-140, N-ter syn; Ventana) or the UltraView DAB (AT8; Ventana). The entire immunostaining procedure was performed using the Benchmark XT automated stainer (Ventana). We have previously found this immunohistochemistry method to be highly sensitive.31 Omission of the primary antibody was performed routinely for each detection system as a negative reagent control, and resulted in no detectable staining. Preimmune sera corresponding to syn110 and syn119 also produced no detectable staining.

Computer-Assisted Image Analysis

The immunostained tissue microarray slides were digitized using a Coolscope slide scanner (Nikon, Melville, NY). The total area labeled by the red chromogen corresponding to α-syn119, α-syn122-140, and α-syn140 in each tissue core was measured using NIS-Elements AR 2.30 software (Nikon). Digital color filters in the software were set to exclude areas labeled by the hematoxylin (blue) nuclear counterstain. Because slides immunostained for α-syn110 showed diffuse cytoplasmic staining that was prominent relative to staining of neurites in all diagnostic groups including controls, the labeled areas corresponding to Lewy neurites and diffuse cytoplasmic positivity were analyzed separately. This was accomplished by first setting a maximum size limit for continuously labeled structures so that nearly all labeling associated with neurites was included but diffuse cytoplasmic labeling was not. A minimum size limit for continuously labeled areas was then set so that diffuse cytoplasmic labeling was included but Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites were not. The same settings were used for all cores. Numbers of Lewy bodies in each core were counted manually and the density was expressed as Lewy bodies/mm2.

Double Immunofluorescence

Antigen retrieval procedures and proteinase K treatment were the same as for immunohistochemistry (see above). The primary antibody dilutions for syn110, syn119, syn140, and phospho-tau were 1:100, 1:100, 1:50, and 1:200, respectively. For double immunofluorescence with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (syn110 or syn119) and a mouse monoclonal antibody (syn140 or phospho-tau) (Table 1), the sections were incubated with a mixture of the two primary antibodies for 2 hours at RT, followed by a mixture of anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) DyLight 488 (green fluorescence) secondary antibody, diluted 1:50, and anti-mouse IgG (H+L) DyLight 549 (red fluorescence) secondary antibody (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD), diluted 1:1000, for 1 hour at 37°C. Double immunofluorescence with the two rabbit polyclonal antibodies (syn110 and syn119) was performed sequentially as follows. The sections were first exposed to syn110, followed by anti-rabbit DyLight 488. The sections were then rinsed several times and exposed to syn119, followed by anti-rabbit DyLight 549 (KPL). The slides were viewed and photographed with an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope equipped with SpectrumGreen and SpectrumOrange filters (Abbott Laboratories, Des Plaines, IL) and an Olympus DP72 digital camera.

Statistics

The areas covered by immunostaining were compared among the diagnostic groups by Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by pair-wise post hoc comparisons using the Tukey test (Dunn Method) on GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). To test whether frequencies of cases with Lewy pathology composed of particular α-syn species differed significantly from the expected equal frequencies of all studied α-syn species in the Lewy pathology, a χ2 goodness-of-fit test was performed using the StatXact V8.0.0 software (Cytel, Cambridge, MA).

Results

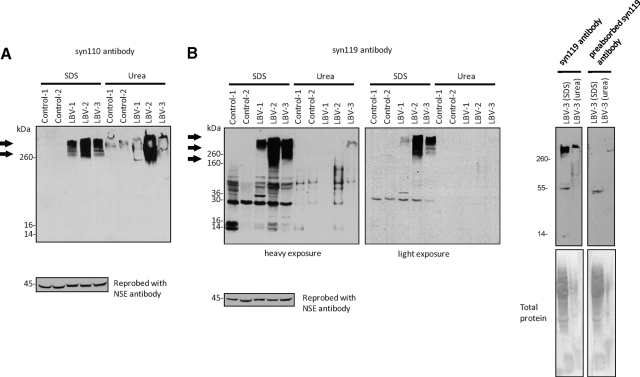

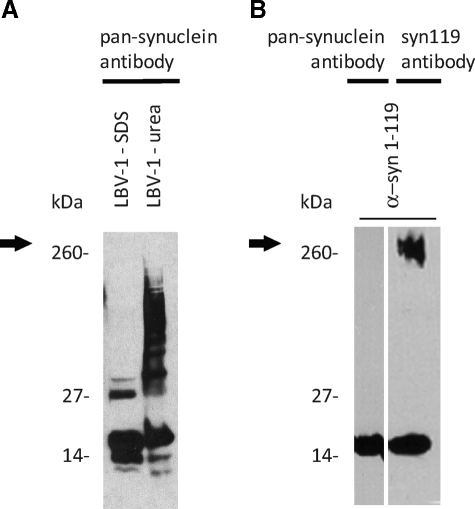

In immunoblots, the newly generated polyclonal antibodies syn110 and syn119 specifically labeled the intended targets, recombinant α-syn ending at amino acids 110 (α-syn110) and 119 (α-syn119), respectively (Figure 2). The syn110 and syn119 antibodies also detected high-molecular-weight aggregates in LBV brains, but not in control brains (Figure 3, A and B). Due to the unexpected immunohistochemistry results obtained with the syn119 antibody (described below), additional specificity control experiments were performed with the syn119 antibody. Preabsorption of the syn119 antibody with the antigenic peptide abolished the signal (Figure 3B), consistent with the specificity of the antibody. High-molecular-weight aggregates of recombinant α-syn119 formed spontaneously after a one-hour incubation of filtration-purified, monomeric α-syn119 in vitro, and these aggregates were detectable with the syn119 antibody in the same molecular weight range as the high-molecular-weight aggregates detected in the LBV brain with the syn119 antibody (Figure 4), providing strong additional evidence that the high-molecular-weight aggregates detected with the syn119 antibody in human brains with Lewy body disease represent aggregated α-syn119. However, the commercial pan-synuclein antibody detected only the recombinant α-syn119 monomer and failed to detect the spontaneously formed high-molecular-weight aggregates of recombinant α-syn119 (Figure 4A-B), consistent with the absence of high-molecular-weight aggregates detectable with the pan-synuclein antibody in the LBV brain (Figure 4A).

Figure 3.

Abnormal high-molecular-weight protein aggregates (arrows) are detected in LBV brains, but not in controls, with the syn110 (A) and syn119 (B) antibodies for C-terminally truncated α-syn. Preabsorption of the syn119 antibody with the antigenic peptide abolishes the signal, which supports the specificity of the antibody. The nonpreabsorbed and preabsorbed syn119 antibodies were exposed to strips from the same membrane; the lanes were separated by several empty lanes in protein electrophoresis to avoid cross-contamination when the samples were loaded on the gel. Total protein was evaluated by Ponceau S staining (NSE, neuron-specific enolase; serial fractionation of brain homogenates followed by immunoblotting).

Figure 4.

High-molecular-weight aggregates of α-syn119 are undetectable with the pan-synuclein antibody. A: The pan-synuclein antibody fails to detect high-molecular-weight aggregates (arrow) in SDS and urea fractions of LBV brain tissue. B: High-molecular-weight aggregates are also not detected with the pan-synuclein antibody in an in vitro preparation of recombinant C-terminally truncated α-syn (α-syn 1-119) after a 1-hour incubation at room temperature, although the monomer is detected. However, high-molecular-weight aggregates composed of recombinant C-terminally truncated α-syn are detected with the syn119 antibody.

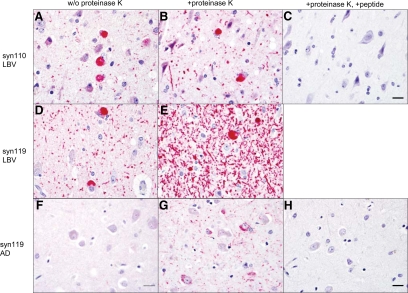

Immunohistochemistry on tissue sections from the cingulate cortex revealed Lewy neurites (abnormal neurites containing aggregated α-syn) and Lewy bodies (round cytoplasmic inclusions composed of aggregated α-syn) containing α-syn110 and α-syn119 in Lewy body disease (Figure 5, A, B, D, and E), and Lewy-like neurites containing α-syn119 in AD (Figure 5G). The immunohistochemical signal in these neurites was markedly enhanced by pretreatment of the tissue sections with proteinase K (Figure 5, B and E), as expected if the truncated α-syn is in an aggregated form. Preabsorption of the antibody with the respective antigenic peptide abolished the signal (Figure 5, C and H).

Figure 5.

Truncated α-syn is detected by immunohistochemistry. Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies containing C-terminally truncated α-syn forms α-syn110 and α-syn119 are present in LBV (A, B, D, and E), and Lewy neurites containing α-syn119 are present in AD (G). Proteinase K pretreatment enhances the immunohistochemical signal for α-syn110 and α-syn119 in Lewy neurites (B, E, G) compared with sections not pretreated with proteinase K (A, D, F), which suggests that the detected truncated α-syn is in an aggregated form. Proteinase K pretreatment was necessary for the detection of any α-syn119-positive neurites in AD (F, G). Preabsorption of the antibody with the respective antigenic peptide abolishes the signal (C, H), which supports the specificity of the signal. (Immunohistochemistry, cingulate cortex; red chromogen; Scale bar = 20 μm).

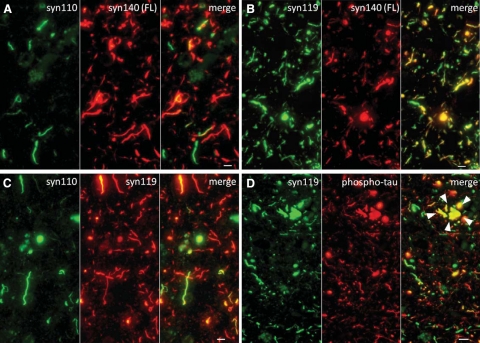

Double immunofluorescence in Lewy body disease demonstrated that α-syn110 pathology was less extensive than α-syn140 pathology (Figure 6A). In addition, typically α-syn110 and α-syn140 did not colocalize in the same neurites and Lewy bodies. All Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies that contained α-syn140 also contained α-syn119, but some neurites contained α-syn119 without α-syn140 (Figure 6B). Double immunofluorescence for α-syn119 and α-syn110 demonstrated that α-syn119 pathology is more extensive than α-syn110 pathology (Figure 6C). Approximately 50% of α-syn110–positive Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies contained predominantly or exclusively α-syn110 and 50% contained both α-syn110 and α-syn119. Therefore, some neurites and Lewy bodies contained α-syn110 only. In AD, phospho-tau did not colocalize with α-syn119 outside neuritic plaques (Figure 6D). Thus, α-syn119–positive neurites and phospho-τ-positive neuropil threads reflect two distinct populations of abnormal neurites in AD. Some colocalization of α-syn119 and phospho-tau was seen in the abnormal, swollen neurites associated with neuritic plaques (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Microscopic localization of C-terminally truncated α-syn (α-syn110 and α-syn119), full-length α-syn (α-syn140), and phospho-tau in the cingulate cortex of an LBV patient (A–C) and an AD patient (D). A: α-syn110 pathology is less extensive than α-syn140 pathology. α-syn110 and α-syn140 are predominantly not colocalized in the same Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies. B: All Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies containing α-syn140 also contain α-syn119, but some Lewy neurites contain α-syn119 without α-syn140. C: α-syn119 pathology is more extensive than α-syn110 pathology. Approximately 50% of α-syn110–positive Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies contain predominantly or exclusively α-syn110 and 50% contain both α-syn110 and α-syn119. D: In AD, most α-syn119–positive Lewy neurites and phospho-τ-positive neuropil threads represent two distinct populations of abnormal neurites. Colocalization of α-syn119 and phospho-tau is mainly limited to dystrophic neurites surrounding neuritic plaques (arrowheads). (Cingulate cortex, double-immunofluorescence; bar = 5 μm in A–C; Scale bar = 10 μm in D).

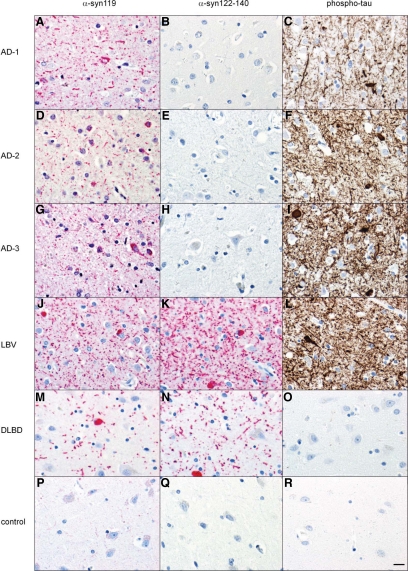

Immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays (TMAs) with tissue cores from the cingulate cortex of 19 AD, 27 DLBD, 27 LBV, and 15 age-similar controls unexpectedly revealed that AD is characterized by Lewy neurites containing α-syn119 but not α-syn ending at amino acids 122-140 (Figure 7). In contrast, Lewy body disease (LBV and DLBD) cases showed both α-syn119–positive and α-syn122-140–positive Lewy pathology. As expected, AD and LBV cases showed frequent phospho-τ–positive neuropil threads and tangles (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

C-terminally truncated α-syn ending at amino acid 119 (α-syn119; red chromogen), α-syn ending at amino acids 122 through 140 (α-syn122-140; red chromogen), and phospho-tau (AT8 antibody; brown chromogen) pathology in the cingulate cortex of three representative AD patients, one LBV patient, one DLBD patient, and one elderly control. The AD patients show α-syn119-positive Lewy neurites (A, D, G) but no α-syn122-140–positive neurites (B, E, H). In contrast, the LBV and DLBD patients show both α-syn119-positive and α-syn122-140–positive Lewy pathology (J–O). As expected, the AD cases and the LBV case show frequent phospho-τ-positive neuropil threads and tangles (C, F, I, L), and no phospho-tau pathology is observed in the DLBD or control case (O, R). (Immunohistochemistry; Scale bar = 20 μm).

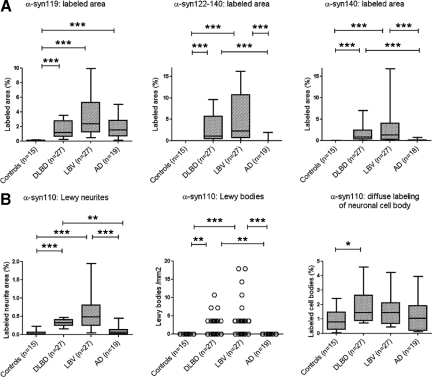

Quantification of the immunohistochemical signals, based on the area fraction covered by the stain, as determined by image analysis, confirmed that AD is characterized by α-syn119 pathology in the absence of significant pathology consisting of longer (α-syn122-140) or shorter (α-syn110) α-syn species (Figure 8A). A large proportion of α-syn110 immunoreactivity was diffuse labeling of neuronal cell bodies rather than Lewy neurites or Lewy bodies. This neuronal cell body labeling was seen in both controls and the disease groups, although a small, statistically significant elevation was seen in DLBD compared with age-similar controls (Figure 8B). The small amount of α-syn110 labeling assigned to neurites by image analysis in AD and control cases (Figure 8B) was found to represent predominantly diffuse cytoplasmic rather than neuritic labeling by manual inspection of the slides.

Figure 8.

A: AD is characterized by α-syn119 pathology in the absence of significant pathology consisting of longer α-syn species (α-syn122-140, α-syn140) detectable by commercial, routinely used diagnostic antibodies. B: In contrast, pathology consisting of a shorter α-syn species (α-syn110) is not elevated in AD compared with controls. A relatively large proportion of α-syn110 immunoreactivity represents diffuse labeling of neuronal cell bodies rather than Lewy neurites or Lewy bodies. Neuronal cell body labeling was observed in both controls and the disease groups. The significance of the cell body labeling for α-syn110 is not clear, but an elevation in DLBD compared with elderly controls is suggestive of a pathological role in some cases (Cingulate cortex, immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays followed by image analysis; median as well as 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percentiles shown in box-and-whisker plots; P values based on Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

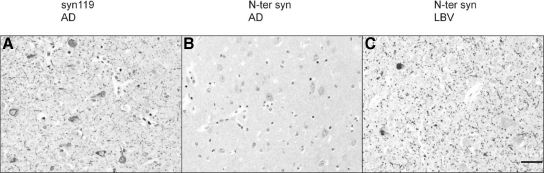

Manual examination of the immunostained TMA slides was also performed microscopically, and the number or cases in each disease group (AD, DLBD, and LBV) and controls showing any pathology of a specific type (Lewy neurites, Lewy bodies, or diffuse cytoplasmic positivity) detectable with antibodies to α-syn110, α-syn119, α-syn122-140, or α-syn140 was recorded (Table 2). The results supported the findings obtained by image analysis and showed that while Lewy pathology in Lewy body disease (DLBD and LBV) was composed of a mixture of both full-length and C-terminally truncated α-syn species, the Lewy-like neurites in AD were almost exclusively composed of α-syn119 (Table 2). Notably, an antibody directed to the N-terminus of α-syn failed to detect any neurites in AD, although frequent Lewy neurites labeled with this antibody in Lewy body disease (Figure 9, A–C), suggesting either truncation of α-syn also at the N-terminus or inaccessibility of the N-terminus to the antibody in AD.

Table 2.

Number of Cases (%) with any C-Terminally Truncated or Full-Length α-Synuclein in the Form of Lewy Neurites, Lewy Bodies, and Diffuse Cytoplasmic Staining*

| Controls (n = 15) | AD (n = 19) | DLBD (n = 27) | LBV (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewy neurites containing | ||||

| α-syn110 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 22 (81) | 22 (81) |

| α-syn119 | 2 (13) | 17 (89) | 27 (100) | 27 (100) |

| α-syn122-140 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 26 (96) | 26 (96) |

| α-syn140 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (89) | 25 (93) |

| P value | <0.0001 | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Lewy bodies containing | ||||

| α-syn110 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (70) | 17 (63) |

| α-syn119 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 19 (70) | 23 (85) |

| α-syn122-140 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 21 (78) | 24 (89) |

| α-syn140 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (81) | 20 (74) |

| P value | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| Diffuse cytoplasmic positivity for | ||||

| α-syn110 | 4 (27) | 9 (47) | 6 (22) | 3 (11) |

| α-syn119 | 3 (20) | 18 (95) | 0 (0) | 10 (37) |

| α-syn122-140 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| α-syn140 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| P value | 0.0772 (n.s.) | <0.0001 | 0.0009 | 0.0001 |

Frequency distributions were significantly different from the expected equal distribution of α-synuclein species for Lewy neurites in the AD group and for diffuse cytoplasmic positivity in the AD, DLBD, and LBV groups. P values based on χ2 goodness-of-fit test (StatXact V8.0.0).

Data based on immunohistochemistry. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DLBD, diffuse Lewy body disease; LBV, Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease; n.s., not significant.

Figure 9.

C-terminally truncated pathological α-syn in AD may also be N-terminally truncated. A: Frequent α-syn119-immunopositive neurites in an AD case. Note also granular cytoplasmic positivity in the cell bodies of some neurons. B: In the same AD case, an antibody directed to the N terminus of α-syn fails to detect any neurites. Weak cytoplasmic immunopositivity is present. C: As expected, a patient with LBV shows frequent neurites and Lewy bodies positive for the N terminus of α-syn (cingulate cortex, immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays; Scale bar = 50 μm).

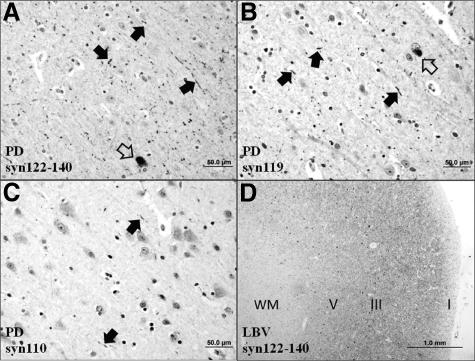

Qualitative examination of immunostained full sections from the cingulate cortex of PD cases (n = 6) revealed a markedly lower density of Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies compared with the LBV and DLBD groups (Figure 10), which is consistent with previous data (eg, Ref. 28). All six PD cases showed at least some abnormal neurites positive for α-syn122-140 (Figure 10A), α-syn119 (Figure 10B), and α-syn110 (Figure 10C). As in the DLBD and LBV groups (Figure 10D), neurites positive for α-syn122-140 and α-syn119 were more abundant than neurites positive for α-syn110. This suggests that the relative content of truncated α-syn species in PD pathology is similar to that in DLBD and LBV.

Figure 10.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by sparse, short Lewy neurites (filled arrows) and rare Lewy bodies (open arrows) in the cingulate cortex. Abnormal neurites positive for α-syn122-140 (A) and α-syn119 (B) are more numerous compared with neurites positive for α-syn110 (C), which suggests that the composition of Lewy neurites in PD is similar to that in DLBD and LBV. As a positive control, a section from the cingulate cortex of an LBV patient was stained for α-syn122-140 (D). As expected, the LBV case shows frequent Lewy neurites, which in this low-power photomicrograph show as diffuse staining in all cortical layers (cortical layers I, III, and V marked). Lewy bodies (small dot-like structures) are most frequent in layers III and V. (Immunohistochemistry; WM, white matter; Scale bar: 50 μm in A–C; 1.0 mm in D).

Discussion

Several lines of evidence indicate that C-terminally truncated forms of α-syn are pathogenic in Lewy body disease. First, C-terminally truncated forms of α-syn aggregate more readily than full-length α-syn and, in vitro, seed incorporation of much larger molar quantities of full-length α-syn into insoluble protofibrils and amyloid-like fibrils.2,14 Second, protofibrils are neurotoxic in cell culture.2 Third, exogenous, recombinant α-syn fibrils seed recruitment of endogenous α-syn into Lewy body-like inclusions in cultured cells.29 Fourth, the A53T α-syn mutation found in some cases of familial Parkinson’s disease exacerbates the effect of C-terminally truncated α-syn on the aggregation of full-length α-syn, further enhancing aggregation of α-syn in vitro.3,30

In the present study, polyclonal antibodies specific for C-terminally truncated α-syn ending at amino acids 110 (α-syn110) and 119 (α-syn119) were generated and characterized. Using these antibodies, α-syn110 and α-syn119 were determined to be components of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in human brains with Lewy body disease. The finding that α-syn119 colocalizes with full-length α-syn in all Lewy neurites containing full-length α-syn while some neurites contain only α-syn119 (Figure 6B) is consistent with the hypothesis that aggregation of C-terminally truncated α-syn such as α-syn119 is an early step in the pathogenesis of Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies. As has been shown to occur with recombinant α-syn110, α-syn120, and α-syn123 in vitro,2,3 it appears likely that oligomers of α-syn119 facilitate incorporation of full-length α-syn into pathological fibril polymers in Lewy body disease. Surprisingly, we found that aggregated α-syn110 did not colocalize with full-length and α-syn (Figure 6A), suggesting that and α-syn110 may play a distinct role in the pathogenesis.

The present study demonstrates α-syn119 and α-syn110 in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites of Lewy body disease and also demonstrates Lewy-like neurites containing α-syn119 in AD without conventional Lewy pathology. In addition we found that 95% of all AD cases examined showed some neurons with diffuse, finely granular cytoplasmic immunopositivity for α-syn119 in the neuronal cell body (Table 2; Figures 5G, 7A, 7D, 7G, and 9A). A smaller proportion (11 to 22%) of Lewy body disease (LBV and DLBD) and controls showed similar diffuse cytoplasmic immunopositivity for α-syn110 (Table 2; Figure 8B). Such diffuse labeling is morphologically distinct from the dense and sharply demarcated Lewy bodies, which were never seen in controls. Mildly increased diffuse cytoplasmic labeling for α-syn110 in DLBD compared with age-similar controls (Figure 8B) is consistent with a pathogenic role for cytoplasmic C-terminally truncated α-syn as a precursor for some Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies. This model is supported by the presence of at least some diffuse cytoplasmic labeling for α-syn119 in 95% of AD cases. By contrast, the proportion of cases with diffuse cytoplasmic labeling was only 20% in controls, 0% in DLBD cases, and 37% in LBV cases (Table 2). Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that cytoplasmic α-syn119 in AD may be the precursor for Lewy neurites, which are almost exclusively composed of α-syn119 in AD. As α-syn110 and α-syn119 are known to be produced by the 20S proteasome in vitro and the proteasome is present throughout the cytosol, it is possible that diffuse cytoplasmic labeling for α-syn110 and α-syn119, when present, is due to the production of these fragments by the proteasome.

A polyclonal antibody against human α-syn119, named EL101, was previously created by Elan Pharmaceuticals by an approach similar to that used by us in the present study.4 In that study, the α-syn119 antibody detected Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in Lewy body disease. However, unlike our syn119 antibody (Figure 3B), the previous antibody did not detect increased amounts of α-syn119 in particulate fractions of Lewy body disease brains compared with soluble fractions of Lewy body disease brains or particulate fractions of control brains by western blotting. The reason for this difference is unclear. The specificity of the previous antibody to α-syn119 was assessed by 2D-gel electrophoresis of Lewy body disease brain tissue but not using defined, recombinant truncated α-syn. Moreover, analysis of AD brain tissue was not reported in this previous study.

A particularly interesting and unexpected finding in the current study was the identification of α-syn119-positive Lewy-like neurites in 17 of 19 AD cases (Table 2, Figure 7). These AD cases had been classified as pure AD cases without α-syn pathology following accepted neuropathologic criteria and using a commercial, widely used31 α-syn antibody (LB509; designated as syn122-140 in this paper for clarity; Table 1). The sensitivity of the routine diagnostic immunohistochemistry (IHC) protocol used in this work is very high for the detection of conventional α-syn pathology. In this regard, the IHC protocol used here for α-syn pathology was recently found to be superior among eight diagnostic IHC protocols tested.31 Therefore, it is unlikely that any significant conventional α-syn pathology was overlooked in the diagnostic workup of these AD cases. Further, α-syn119–positive neurites were frequent in nearly all AD cases (Figures 7A, 7D, 7G, and 9A). On average, α-syn119–positive pathology in AD was comparable to that in Lewy body disease (Figure 8A). However, there was a difference in the microscopic appearance of the α-syn119 pathology in that the pathology in AD consisted of Lewy-like neurites and some diffuse cytoplasmic labeling in the absence of Lewy bodies (Figures 7A, 7D, 7G, and 9A), whereas both Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies, but little diffuse cytoplasmic staining, were seen in Lewy body disease (Figure 7, J and M). The cause for these morphological differences is unknown, but a possible explanation is that α-syn119–positive neurites in AD represent an early stage of α-syn pathology where Lewy bodies and conventional α-syn pathology with aggregated full-length α-syn have not yet developed. This hypothesis is supported by the finding that two of 15 age-similar controls also had rare α-syn119–positive neurites without Lewy bodies or conventional α-syn pathology (Table 2). These control patients may thus be in a very early subclinical stage of Lewy body disease.

It is interesting to note that Lewy-like neurites in AD are positive for only α-syn119 and not for α-syn110 or α-syn ending at amino acid residues 122 through 140 (full-length; Figures 7 and 8A), suggesting that abnormal neurites containing specifically α-syn119, but not other α-syn metabolites, may be a unique feature of AD. The finding that α-syn119–positive neurites are present in the cingulate cortex of 89% of AD cases (Table 2) raises the possibility that α-syn119–positive neurites are a consistent feature of AD. In the future, as additional brain areas are studied, it will be interesting to examine the relationship of this α-syn pathology to the Aβ in plaques and phospho-tau in tangles, first described in AD by Alois Alzheimer more than a hundred years ago.32

An intriguing possibility is that AD pathology, which consists of aggregated phospho-tau in tangles and neuropil threads as well as aggregated Aβ in plaques, predisposes to formation of α-syn119–positive neurites, which may subsequently lead to full-blown α-syn pathology in the form of conventional Lewy neurites and Lewy bodies containing both full-length and truncated α-syn forms. Such conventional α-syn pathology in combination with AD pathology is classified as LBV. This hypothesis would explain why LBV is much more common than expected based on the theoretical probability of a patient developing both AD and Lewy body disease independently. The finding that, except in dystrophic neurites surrounding Aβ plaques, phospho-tau is not colocalized with α-syn119 in AD (Figure 6D), argues against a direct role for phospho-tau in inducing aggregation of α-syn119. Interestingly, Aβ binds to the proteasome and inhibits ubiquitin-dependent degradation activity of the 20S proteasome via inhibition of chymotrypsin-like activity.33,34 By contrast, the C-terminally truncated fragments α-syn110 and α-syn119 are generated from full-length α-syn in a ubiquitin-independent manner by the 20S proteasome via endoproteolytic cleavage by the caspase-like activity in vitro2 The relative contributions of ubiquitin-dependent and ubiquitin-independent proteasome pathways to α-syn degradation may be altered in specific situations.14 Interestingly, selective inhibition of the proteasomal trypsin-like activity in vitro actually increases production of α-syn110 and α-syn119.2 One possibility is that excess Aβ in AD overloads proteasome capacity, leading to incomplete ubiquitin-dependent degradation of α-syn, and accumulation of α-syn119, which then can give rise to conventional α-syn pathology in some cases. This hypothesis is also supported by the observations that Aβ pathology tends to be relatively more severe than phospho-tau pathology in LBV compared with pure AD35 and that truncated forms of α-syn are proportionally more abundant in LBV compared with DLBD.16

We have not definitively proven that α-syn119 is in an aggregated form in AD, but our findings suggest that this is the case. Pretreatment with proteinase K enhanced the immunohistochemical signal for α-syn119 in AD (Figure 5, F and G), as it did in cases of conventional LBD (Figure 5, D and E). It is known that proteinase K pretreatment enhances the immunohistochemical signal for aggregated full-length α-syn but suppresses the signal for monomeric full-length α-syn (reviewed in Ref. 28). The same is true for aggregated and monomeric prion protein, respectively.28 Therefore, it is likely that α-syn119 is aggregated rather than monomeric in AD. In any case, because α-syn119–positive neurites were generally absent in controls (Table 2), α-syn119–positive neurites in AD represent a pathological abnormality.

Although our current results do not directly address the significance of α-syn119 in the pathogenesis of AD, it is possible that α-syn119 contributes to neurodegeneration and dementia in AD. This hypothesis is not inconsistent with the finding that combined conventional Lewy pathology and AD pathology in LBV is not associated with shortened patient survival compared with pure AD.35 Evidence from cell culture studies suggests that aggregation intermediates (oligomers and protofibrils) of α-syn and other proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases are neurotoxic whereas α-syn monomers are not and mature, fully polymerized fibrils may even have neuroprotective qualities.2,36,37,38,39 Hence, it is possible that by the time conventional α-syn pathology becomes evident and AD turns to LBV, the bulk of damage has already been inflicted by α-syn119 oligomers and protofibrils. The evidence suggesting that excess α-syn119 is generated when full-length α-syn is endoproteolytically cleaved by a partially incapacitated proteasome2 raises the possibility of specifically targeting the proteasome for the treatment of AD and Lewy body disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinical faculty and staff of the UT Southwestern Medical Center Alzheimer’s Disease Center for clinical evaluations, Dallas County Medical Examiner’s Office for some of the tissue samples, Ping Shang and the UT Southwestern Pathology Immunohistochemistry Laboratory for expert technical assistance with the immunohistochemical stains and preparation of the tissue microarrays, and Niccole Duckworth and Agatha Villegas for outstanding administrative professional services. We are grateful to the patients and their families for their participation.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Kimmo J. Hatanpaa, M.D., Ph.D., Division of Neuropathology, Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX 75390. E-mail: kimmo.hatanpaa@utsouthwestern.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) DK49835, Welch Foundation, NIH GM07062, NIA/NIH 5P30AG012300, NCRR/NIH UL1RR024982 (North and Central Texas Clinical and Translational Science Initiative, Milton Packer, M.D., PI, Pilot Award), Winspear Family Center for Research on the Neuropathology of Alzheimer Disease, Friends of the UT Southwestern Alzheimer’s Disease Center, and McCune Foundation.

Current address of K.A.L.: Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Colorado at Boulder, Boulder, CO.

References

- Hoyer W, Cherny D, Subramaniam V, Jovin TM. Impact of the acidic C-terminal region comprising amino acids 109-140 on alpha-synuclein aggregation in vitro. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16233–16242. doi: 10.1021/bi048453u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CW, Giasson BI, Lewis KA, Lee VM, Demartino GN, Thomas PJ. A precipitating role for truncated alpha-synuclein and the proteasome in alpha-synuclein aggregation: implications for pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22670–22678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, West N, Colla E, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Marsh L, Dawson TM, Jakala P, Hartmann T, Price DL, Lee MK. Aggregation promoting C-terminal truncation of alpha-synuclein is a normal cellular process and is enhanced by the familial Parkinson’s disease-linked mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2162–2167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406976102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JP, Walker DE, Goldstein JM, de Laat R, Banducci K, Caccavello RJ, Barbour R, Huang J, Kling K, Lee M, Diep L, Keim PS, Shen X, Chataway T, Schlossmacher MG, Seubert P, Schenk D, Sinha S, Gai WP, Chilcote TJ. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29739–29752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher JP, Ying M, Banerjee R, McDonald RS, Hahn MD, Yang L, Flint Beal M, Thomas B, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Moore DJ. Conditional transgenic mice expressing C-terminally truncated human alpha-synuclein (alphaSyn119) exhibit reduced striatal dopamine without loss of nigrostriatal pathway dopaminergic neurons. Mol Neurodegener. 2009;4:34. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamatsu M, Ishii A, Iwata S, Sakagami J, Ukai Y, Ono M, Kanbe D, Muramatsu SI, Kobayashi K, Iwatsubo T, Yoshimoto M. Selective loss of nigral dopamine neurons induced by overexpression of truncated human alpha-synuclein in mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:574–585. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofaris GK, Garcia Reitbock P, Humby T, Lambourne SL, O'Connell M, Ghetti B, Gossage H, Emson PC, Wilkinson LS, Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Pathological changes in dopaminergic nerve cells of the substantia nigra and olfactory bulb in mice transgenic for truncated human alpha-synuclein(1-120): implications for Lewy body disorders. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3942–3950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4965-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MC, Bishop JF, Leng Y, Chock PB, Chase TN, Mouradian MM. Degradation of alpha-synuclein by proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33855–33858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Guttmann RP, Giasson BI, Day GA, 3rd, Hodara R, Ischiropoulos H, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Lynch DR. Distinct cleavage patterns of normal and pathologic forms of alpha-synuclein by calpain I in vitro. J Neurochem. 2003;86:836–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Norris EH, Giasson BI, Hodara R, Ischiropoulos H, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Lynch DR. Cleavage of alpha-synuclein by calpain: potential role in degradation of fibrillized and nitrated species of alpha-synuclein. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7818–7829. doi: 10.1021/bi047846q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevlever D, Jiang P, Yen SH. Cathepsin D is the main lysosomal enzyme involved in the degradation of alpha-synuclein and generation of its carboxy-terminally truncated species. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9678–9687. doi: 10.1021/bi800699v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culvenor JG, McLean CA, Cutt S, Campbell BC, Maher F, Jakala P, Hartmann T, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Li QX. Non-Abeta component of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid (NAC) revisited. NAC and alpha-synuclein are not associated with Abeta amyloid. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CW, Corboy MJ, DeMartino GN, Thomas PJ. Endoproteolytic activity of the proteasome. Science. 2003;299:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1079293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KA, Yaeger A, DeMartino GN, Thomas PJ. Accelerated formation of alpha-synuclein oligomers by concerted action of the 20S proteasome and familial Parkinson mutations. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2010;42:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9258-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchikado H, Lin WL, DeLucia MW, Dickson DW. Alzheimer disease with amygdala Lewy bodies: a distinct form of alpha-synucleinopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:685–697. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000225908.90052.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnikova O, West N, Lee MK, Rudow GL, Skolasky RL, Dawson TM, Marsh L, Troncoso JC. Abeta deposition is associated with enhanced cortical alpha-synuclein lesions in Lewy body diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1183–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, Golbe LI, Graves CL, Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;300:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1082324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes JW. alpha-Synuclein: a potent inducer of tau pathology. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamah CE, Lesnick TG, Lincoln SJ, Strain KJ, de Andrade M, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA, Farrer MJ, Maraganore DM. Interaction of alpha-synuclein and tau genotypes in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:439–443. doi: 10.1002/ana.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith I, Fairbairn A, Perry R, Thompson P, Perry E. Neuroleptic sensitivity in patients with senile dementia of Lewy body type. Bmj. 1992;305:673–678. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6855.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang TC, Luo W, Hsieh JT, Lin SH. Antibody binding to a peptide but not the whole protein by recognition of the C-terminal carboxy group. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;329:208–214. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakes R, Crowther RA, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Iwatsubo T, Goedert M. Epitope mapping of LB509, a monoclonal antibody directed against human alpha-synuclein. Neurosci Lett. 1999;269:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntern R, Bouras C, Hof PR, Vallet PG. An improved thioflavine S method for staining neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Experientia. 1992;48:8–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01923594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirra SS, Hart MN, Terry RD. Making the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. A primer for practicing pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:132–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:389–404. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda JE, Lippa C, Perry EK, Aarsland D, Arai H, Ballard CG, Boeve B, Burn DJ, Costa D, Del Ser T, Dubois B, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Goetz CG, Gomez-Tortosa E, Halliday G, Hansen LA, Hardy J, Iwatsubo T, Kalaria RN, Kaufer D, Kenny RA, Korczyn A, Kosaka K, Lee VM, Lees A, Litvan I, Londos E, Lopez OL, Minoshima S, Mizuno Y, Molina JA, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Pasquier F, Perry RH, Schulz JB, Trojanowski JQ, Yamada M. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman D, McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:42–47. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach TG, Adler CH, Lue L, Sue LI, Bachalakuri J, Henry-Watson J, Sasse J, Boyer S, Shirohi S, Brooks R, Eschbacher J, White CL, 3rd, Akiyama H, Caviness J, Shill HA, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Walker DG. Unified staging system for Lewy body disorders: correlation with nigrostriatal degeneration, cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:613–634. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk KC, Song C, O'Brien P, Stieber A, Branch JR, Brunden KR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils seed the formation of Lewy body-like intracellular inclusions in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20051–20056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KA, Harper JD, Lansbury PT. Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant alpha-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat Med. 1998;4:1318–1320. doi: 10.1038/3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach TG, White CL, Hamilton RL, Duda JE, Iwatsubo T, Dickson DW, Leverenz JB, Roncaroli F, Buttini M, Hladik CL, Sue LI, Noorigian JV, Adler CH. Evaluation of alpha-synuclein immunohistochemical methods used by invited experts. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:277–288. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer A, Stelzmann RA, Schnitzlein HN, Murtagh FR. An English translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde.”. Clin Anat. 1995;8:429–431. doi: 10.1002/ca.980080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregori L, Fuchs C, Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Van Nostrand WE, Goldgaber D. Amyloid beta-protein inhibits ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19702–19708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregori L, Hainfeld JF, Simon MN, Goldgaber D. Binding of amyloid beta protein to the 20 S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:58–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman A, Fillenbaum GG, Gearing M, Mirra SS, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Peterson B, Pieper C. Comparison of Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease with pure Alzheimer’s disease: consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Part XIX Neurology. 1999;52:1839–1844. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM, Stefani M. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinar DP, Balija MB, Kugler S, Opazo F, Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Wender N, Kim HY, Taschenberger G, Falkenburger BH, Heise H, Kumar A, Riedel D, Fichtner L, Voigt A, Braus GH, Giller K, Becker S, Herzig A, Baldus M, Jackle H, Eimer S, Schulz JB, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M. Pre-fibrillar alpha-synuclein variants with impaired beta-structure increase neurotoxicity in Parkinson’s disease models. EMBO J. 2009;28:3256–3268. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]