Abstract

Obesity represents a risk factor for certain types of cancer. Leptin, a hormone predominantly produced by adipocytes, is elevated in the obese state. In the context of breast cancer, leptin derived from local adipocytes is present at high concentrations within the mammary gland. A direct physiological role of peripheral leptin action in the tumor microenvironment in vivo has not yet been examined. Here, we report that mice deficient in the peripheral leptin receptor, while harboring an intact central leptin signaling pathway, develop a fully mature ductal epithelium, a phenomenon not observed in db/db mice to date. In the context of the MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor model, the lack of peripheral leptin receptors attenuated tumor progression and metastasis through a reduction of the ERK1/2 and Jak2/STAT3 pathways. These are tumor cell-autonomous properties, independent of the metabolic state of the host. In the absence of leptin receptor signaling, the metabolic phenotype is less reliant on aerobic glycolysis and displays an enhanced capacity for β-oxidation, in contrast to nontransformed cells. Leptin receptor-free tumor cells display reduced STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation on residue Y705 but have increased serine phosphorylation on residue S727, consistent with preserved mitochondrial function in the absence of the leptin receptor. Therefore, local leptin action within the mammary gland is a critical mediator, linking obesity and dysfunctional adipose tissue with aggressive tumor growth.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the United States and the second leading cause of cancer death in women according to the annual report of American Cancer Society. Large-scale epidemiological studies have demonstrated that obesity increases the risk of developing cancers in several different tissues, including endometrium, colon, kidney, and postmenopausal breast cancer. Furthermore, obesity has shown to be associated with a high rate of recurrence and a poor survival rate.1,2 Hyperinsulinemia, an increase in insulin-like growth factors, or dysregulation of steroid hormones observed in obese individuals have all been suggested as possible mechanisms that link obesity and cancer risk.1,2,3 More specifically, adipose tissue derived signaling molecules, including adipokines and matrix proteins, are emerging as key candidate molecules linking obesity to cancer.4,5,6 We have previously demonstrated that adipocytes are highly active endocrine cells that secrete numerous factors, which can ultimately influence stromal-epithelial cell interactions within the mammary tumor microenvironment.7 Since the ductal epithelium in the mammary gland is embedded in adipose tissue, adipocytes represent a prominent cell-type in this stromal environment, affecting the growth and survival of transformed mammary epithelial cells in multiple ways. This stromal microenvironment in the mammary gland is altered in obese individuals, with a general increase in the inflammatory state; this may offer a more amenable overall environment for tumor growth. However, specific target molecules and defined molecular mechanisms that delineate the link between dysregulated adipose tissue metabolism, and the risk of cancer development, remain largely unknown.

Leptin is a multifunctional hormone produced by adipose tissue that is predominantly involved in the regulation of food-intake and energy homeostasis through its central actions.8 Although leptin receptors are most abundantly expressed in the brain, they are also present in several peripheral tissues, including the liver, skeletal muscle, pancreatic β-cells, and adipose tissues. Therefore, in addition to central functions, leptin is postulated to exert peripheral actions, with several studies documenting associations with the immune response, angiogenesis, reproduction, signaling pathways of growth hormones, and lipid metabolism pathways.9,10 Furthermore, a number of reports indicate that leptin receptor levels are increased in mammary carcinoma tissues relative to benign or normal tissues.11,12 Elevated leptin levels in obese individuals have been implicated as a risk factor for breast cancer. However, there is still no clear-cut picture emerging from epidemiological studies with respect to circulating leptin levels and the risk of breast cancer incidence at present.13 Despite several observations obtained from in vitro cell-line experiments, human biopsy studies, and epidemiological correlations that suggest an involvement of leptin in mammary tumorigenesis, the use of genetic animal models to ascertain the direct physiological function of leptin in cancer biology remains to be evaluated. Functional leptin or leptin receptor deficient mouse models, such as ob/ob or db/db, are not suitable models to address the functional role that leptin plays in obesity-associated cancers in general, or specifically in mammary tumorigenesis; these mice suffer from defective development of the ductal epithelium, and as a consequence, lack such structures. In light of this, a recent report by Chua and colleagues14 indicated that reconstitution of leptin receptor signaling in neurons of db/db mice, through transgenic overexpression of the leptin receptor, completely rescues the metabolic phenotype commonly displayed in db/db mice. To further corroborate this, we demonstrate that these mice fully restore their development of the ductal epithelium. The observations reported here are the first in vivo experiments to highlight the role of peripheral leptin signaling in breast cancer progression. To achieve this conclusion, we crossed the brain-specific long form of leptin receptor (NseLEPR-B) transgenic mouse into the background of a mammary tumor mouse model (MMTV-PyMT: mouse mammary tumor virus-polyoma virus middle T antigen). Consequently, we provide strong in vivo evidence for a novel local paracrine function of peripheral leptin within the mammary gland; such observations ultimately implicate leptin as a major player in mammary tumor development.

Leptin receptor-mediated pathways effectively support Ras- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent pathways of tumorigenesis, which result in an enhanced level of tumor progression and metastasis; the latter includes a higher rate of proliferation, anti-apoptosis, and increase in an aerobic glycolytic capacity. In light of this, our results demonstrate that obese, dysfunctional adipose tissue, in the stroma of a mammary gland, has the capability to bestow tumor cells with severe progressive and metastatic properties. We therefore propose that such detrimental characteristics develop through a paracrine leptin receptor-mediated pathway. Leptin is therefore a key candidate that may link obesity to more aggressive tumor phenotype. Collectively, our data suggest that local leptin levels may play a major role in tumor progression within the mammary gland, and as such, leptin receptor-based pathways may serve as valuable therapeutic targets for tumors in obese patients with breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Animal Experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment with 12-hour light/dark cycles and fed standard rodent chow. Animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. Tissue samples and serum for leptin, insulin, and glucose determinations were collected when mice were sacrificed. In live animals, serum was collected by nicked tail vein bleeding. For fasted serum glucose measurements, mice were fasted for overnight and measured serum glucose level by tail vein bleeding. Serum leptin and insulin were determined by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (LINCO Research, St. Charles, MO).

db/db NseLEPR-B mice were kindly provided by Dr. Streamson Chua (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York) and genotyped as previously described.14 MMTV-PyMT mice originally developed by Dr. William Muller were used as a breast cancer mouse model,15 which is a pure FVB background. Homozygous db/db NseLEPR-B (db/dbNse/Nse) mice in a pure FVB background (10 backcross generations) were used in this study. To establish female homozygous db/dbNse/Nse in the background of MMTV-PyMT mice, the following breeding strategy was used. PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice were generated by mating with db/dbNse/Nse in the background of MMTV-PyMT male and db/dbNse/Nse female mice. Male breeding partner PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse was generated by mating with heterozygous db/+Nse/− in the background of MMTV-PyMT male and db/dbNse/Nse female. Male breeding partner the db/+Nse/− in the background of MMTV-PyMT was generated by mating with MMTV-PyMT male and db/dbNse/Nse female. Homozygous db/dbNse/Nse mice were generated by mating with heterozygous db/dbNse/− male and female mice. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine genotype of heterozygous and homozygous of NseLEPR-B transgene. All mice used in this study are in a FVB pure background.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated following tissue homogenization in Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a TissueLyser (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in the Roche Lightcycler 480 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). For all quantitative real-time PCR experiments, the results were calculated by using the ΔΔCt method using β-actin to normalize. Primer sequences used in this study are listed: LEPR-B, sense-5′-GGTTGGATGAGCTTTTGGAA-3′, antisense-5′-TCCTGGAGGATCCTGATGTC-3′; β-Actin, sense-5′-CCACACCCGCCACCAGTTCG-3′, antisense-5′-TACAGCCCGGGGAGCATCGT-3′.

Whole Mount Staining

Inguinal mammary glands were excised, spread onto glass slides, and fixed in 70% methanol and 25% acetic acid for 3 hours at room temperature. Specimens were hydrated with descending grades of ethanol (100%, 80%, and 70%, two times for 5 minutes each) and rinsed with distilled water. Whole mount staining was performed with carmine alum (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in the dark overnight. After washing with 70%, 80%, and 100% EtOH two times for 5 minutes each, slides were incubated with xylene overnight to dissolve the fat pad. Images were acquired by using the Nikon Cool Scope and analyzed for ductal epithelium growth and tumor area by using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Analysis of Tumor Progression and Lung Metastasis

Tumor onset was monitored twice weekly by palpation. Tumor sizes were measured with a digital caliper twice a week, and the volume was calculated as (length × width2)/2. Inguinal tumors were weighted to determine tumor burden. Animals were sacrificed when the tumor burden visibly affected the host or when the tumors reached the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) set limit of 20 mm along one axis. Metastasis was determined by histological analysis with H&E stained lung tissues.

Immunochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections were used for immunostaining. Deparaffinized tissue slides were stained with the following primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal against pSTAT3 (Y705; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), pSTAT3 (S727; Cell Signaling), pAkt (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), CyclinD1 (Santa Cruz), mouse monoclonal COXIV (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and rat monoclonal Ki-67 (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). For immunofluorescence, fluorescence labeled secondary antibodies were used and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images were acquired by using the Leica confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and analyzed with Image J software. For immunohistochemistry, the reaction was visualized by the DAB Chromogen-A system (Dako Cytomation) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were acquired by using the Nikon Cool Scope. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was followed by the manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Primary Culture of Mammary Tumor Cells

To isolate primary tumor cells, tumor tissues were excised from female mice and minced by using a razor blade in PBS. Tumors were incubated with collagenase type III (1.25 mg/ml) and hyaluronidase (1 mg/ml) for 2 hours at 37°C. Cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 minutes, and pellets were incubated with 0.25% trypsin for 10 minutes at 37°C. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 minutes, and pellets were incubated with DNaseI (20 U/ml) for 10 minutes at 37°C; cell pellets were washed with PBS containing 5% serum. Cells were seeded into culture dishes in growth medium, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, Bio-Product, West Sacramento, CA) after passing through a 40-μm nylon filter (Fisher, PA). Freshly isolated cells were used in this study.

Transplantation of Tumors

For tumor tissue transplantation, mammary tumor tissues were excised from donor mice and minced into small fragments (1 to 2 mm in diameter) in ice-cold PBS with a razor blade. Recipient animals were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and a small abdominal skin incision was made to explore the inguinal mammary fat pad where a tumor piece was transplanted. Mammary epithelial tumor (MET) cells were transplanted at donor mice by intraductal injection. Tumor growth was monitored once a week starting 2 weeks after transplantation.

Immunoblotting

Total cell extracts were extracted in NETN buffer (150 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.6, and 0.1% NP40 contains protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor [Roche]). Proteins were separated on a 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). STAT3, pSTAT3, Akt1, pAkt, ERK, pERK, CyclinD1, Bcl-xl, and β-actin were used as primary antibodies. The primary antibodies were detected with secondary IgG-labeled with infrared dyes emitting at 700 and 800 nm (Licor Bioscience, Lincoln, NE) and visualized on the Licor Odessey Infrared Scanner (Licor Bioscience). The scanned results were analyzed by using the Odessey v2.1 software (Licor Bioscience).

Analysis of Mitochondrial Function

Mitochondria oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and glycolysis was measured by using the XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Primary cultured mammary epithelial tumor cells (60,000 cells/well) were used as described in the experiments.

Statistical Analyses

Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences between mean values were evaluated by using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-test when two groups were analyzed or two-way analysis of variance for three or more groups as appropriate with GraphPad Prism v.5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Interactions between factors were tested for two-way analysis of variance.

Functional Blood Vessel and Hypoxyprobe Stain

To assess functional blood vessels formation and the hypoxic regions in tumor tissues, mice were injected with biotinylated tomato-lectin (100 μg, i.v.; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and pimonidazole (60 mg/kg, i.p.; Hypoxyprobe-1 plus, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) as described in a previous report.16 The lectin was visualized by a Cy3-labeled streptoavidin and the hypoxyprobe was visualized by following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Gene Expression Profiling

Total RNA was extracted from tumor tissue at 12-week-old PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse (n = 12 per group). Microarray experiments were performed by University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center microarray core facility. Mouse Illumina Bead Array platform (47K array; Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA) were used in this study. Gene lists and cluster analyses of the data sets were performed by using Ingenuity pathway software (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA) and David Bioinformatics Resource (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/, last accessed January 29, 2010).

Results

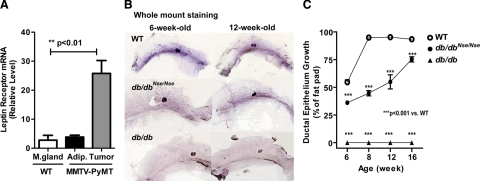

LEPR-B Levels Are Significantly Increased in Mammary Tumor Tissues in MMTV-PyMT Mice

We examined leptin and long form of leptin receptor (LEPR-B) expression levels, in addition to circulating leptin levels in a murine MMTV-PyMT mammary cancer model (PyMT), a transgenic mouse model that expresses the polyoma virus middle-T antigen under the control of a mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Consistent with previous data obtained by using cell-lines and human biopsies, we show that LEPR-B mRNA levels are massively up-regulated (by 10-fold) in mammary tumor tissues, when compared with adipose tissue of PyMT mice within the same glands, or with mammary glands of wild-type littermates at 12 weeks of age (Figure 1A). In contrast, hypothalamic LEPR-B levels were comparable between wild-type and PyMT mice, therefore suggesting that mammary tumorigenesis is primarily affected by peripheral leptin signaling within the transformed ductal epithelial cells (see supplemental Figure 1A at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). During tumor progression, both circulating levels of leptin and expression levels of leptin in epididymal adipose tissues were shown to be unaffected by the presence of a tumor. In the later stages of tumor development, however, a moderate decrease in leptin levels was evident in PyMT mice, due to a reduction in their body fat mass (see supplemental Figure 1, B and D, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). However, in mammary adipose tissue, a significant decrease in leptin mRNA levels were observed between PyMT mice, in comparison to their wild-type littermates; this is consistent with a reduction in local adipose tissue mass during tumor progression (see supplemental Figure 1C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Although it is established that leptin is largely produced in adipocytes, in light of this, we noted that leptin mRNA levels within mammary tumors were significantly lower than in corresponding mammary adipose tissues (see supplemental Figure 1C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Such observations are consistent with the existence of a very active paracrine loop in the mammary tumor microenvironment involving leptin signaling.

Figure 1.

Mouse model system for peripheral leptin receptor deficiency (db/dbNse/Nse) in MMTV-PyMT mice. A: LEPR-B is highly expressed in tumor tissues. mRNA levels of LEPR-B are predominantly increased in tumor tissues (Tumor) compared with mammary adipose tissues (Adipo) of MMTV-PyMT mice or mammary gland (M. gland) of FVB wild-type (WT) mice. mRNA levels were analyzed with quantitative real-time PCR after normalization with β-actin and represented by mean ± SEM (n = 4 to 7 per group). **P < 0.01 versus wild type, by t-test. B: Mammary ductal epithelium growth is recovered by reconstitution of LEPR-B in neurons in db/db mice. Morphological analysis of ductal epithelium growth was performed with whole mount preparations of inguinal mammary gland from 6-week-old and 12-week-old WT, and db/dbNse/Nse and db/db females. C: Quantitative measurement of ductal epithelium growth during mammary gland development. The length from the nipple to the three far reaching ductal epithelium and to the edge of the fat pad was measured from whole mount preparations of WT (n = 4 to 6 per group), db/dbNse/Nse (n = 10 to 17 per group), and db/db (n = 3 per group). Ductal epithelium growth is corresponded to the ductal epithelium length as percentage of the fat pad. Measurements were quantified by using Image J. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001 versus WT, by two-way analysis of variance (no-matching).

LEPR-B Reconstitution in Neurons Is Sufficient to Restore Mammary Gland Development in db/db Mice

Most primary breast tumors originate from mammary ductal or intraductal epithelial cells. Genetically, leptin or leptin receptor deficient mouse models, such as ob/ob or db/db, are hypogonadal and have structural and functional defects of mammary gland development. Such defects include impairments in ductal epithelial growth, alveolar formation, milk production, the onset of involution, and fertility.17 Therefore, ob/ob and db/db mice exhibit only remnant ductal epithelial growth and do not develop tumors when bred into mammary cancer mouse models.18,19 Despite several attempts using various mouse models to examine the impact that leptin has on mammary tumor progression, to date, there is very limited evidence to support the physiological role of leptin in mammary tumorigenesis. However, brain-specific LEPR-B transgenic mice in a db/db background (that we refer to as “db/db NseLEPR-B” mice) manifest a normalized metabolic phenotype when compared with db/db mice; more specifically, the former are lean, nondiabetic, and fertile.14,20 Such metabolic improvements are more pronounced in homozygous transgenic mice (db/dbNse/Nse) in comparison with hemizygous transgenic animals (db/dbNse/−).14,21

To evaluate whether db/dbNse/Nse mice have the capacity to fully develop mammary gland, we determined the length of ductal epithelium growth and subsequent branching structure. Mammary gland development was slightly delayed in db/dbNse/Nse mice (Figure 1B); however, it achieved approximately 90% of the values observed for wild-type mice at 16 weeks of age, whereas db/db mice showed a complete deficiency of ductal epithelial development at all ages (Figure 1C). These results highlight that the db/dbNse/Nse mouse is an excellent model to study the physiological roles of peripheral leptin signaling on mammary tumorigenesis within the local tumor microenvironment.

Peripheral LEPR-B Deficiency Attenuates Tumor Growth and Metastasis in MMTV-PyMT Mice

To investigate the contribution that leptin receptor-mediated signaling has on mammary tumorigenesis, we introduced homozygous db/dbNse/Nse transgenic mice into the PyMT, thus generating peripheral LEPR-B mutants (PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse), along with control littermates (PyMT) in the background of MMTV-PyMT. Initially, although PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice exhibited a moderate increase in whole-body weight gain in comparison with PyMT mice, body weights eventually became comparable in the later stages of tumorigenesis due to the tumor burden in PyMT mice (see supplemental Figure 1E at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Both PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice displayed the expected changes in circulating leptin levels and insulin levels within a narrow range, and further managed to maintain glucose at euglycemic levels comparable with that of wild-type FVB mice. The latter observation suggests that the metabolic differences between PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice do not necessarily result in an obese or diabetic phenotype (see supplemental Figure 1, F–H, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

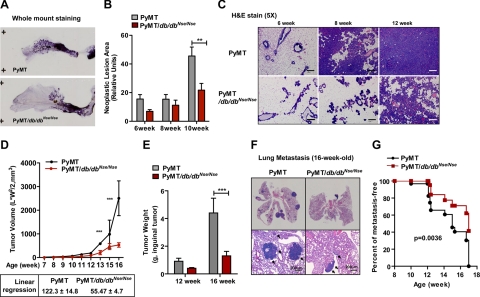

To explore the effects that leptin receptor-mediated signaling has on early tumorigenic events, using whole mount preparations, we assessed PyMT-induced neoplastic lesion areas in inguinal mammary glands obtained from 6- to 10-week-old aged-matched PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice (Figure 2, A and B). At 10 weeks of age, a 2.4-fold reduction in neoplastic lesion area in the PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice, when compared with PyMT controls, was clearly evident (Figure 2B). Such a decrease in neoplastic lesion size in the early stages of tumor progression is further reflected in the H&E stains of primary tumor growth in the PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice compared with PyMT mice (Figure 2C). As shown in Figure 2D, tumor volume of inguinal mammary tumor (as determined by caliper measurements) started to differ dramatically between PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse in 12- to 13-week-old mice. The rate of tumor growth in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse was markedly reduced by approximately twofold, in comparison with PyMT mice (as determined by linear regression analysis; 122.3 ± 14.8 for PyMT versus 55.47 ± 4.7 for PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse, P < 0.001; Figure 2D). Consistently, the weight (in grams) of these inguinal tumors was shown to be dramatically lower in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice when compared with PyMT mice at 16 weeks of age (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Primary tumor growth and pulmonary lung metastasis are significantly attenuated in MMTV-PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice compared with MMTV-PyMT mice. A: Representative whole mount preparations of inguinal mammary gland from 12-week-old PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. B: The neoplastic lesion area was quantified in 6, 8, and 10 weeks of age PyMT (n = 6 per each group) and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice (n = 4 to 6 per each group) by using Image J. Results are represented by mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01 versus PyMT by two-way analysis of variance (no-matching). C: Histological analysis of whole mammary tumor tissues from PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice during tumor progression. Represented images were H&E-stained mammary tumor tissues. Scale bar represents 200 μm. D: Tumor volume was determined by weekly caliper measurements from PyMT (n = 12) and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse (n = 15) females. Four PyMT mice were terminated before end of the experiment due to extensive tumor burden at 14 weeks of age. Total tumor volumes are represented by mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001 versus PyMT by two-way analysis of variance (no matching). Linear regression analysis was performed with PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice from 12 weeks to 16 weeks of age. Results are represented in the graph. E: The weights of inguinal tumors were determined from PyMT (n = 8 and n = 4 per group, respectively) and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice (n = 12 and n = 4 per group, respectively) from 12 to 16 weeks of age. ***P < 0.001 versus PyMT by two-way analysis of variance (no matching). F: Pulmonary metastasis was assessed by H&E stain of lung tissues from PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice at 16 weeks of age. Whole lung tissue images are presented in the upper panel, and those in higher magnification are shown in the bottom panel. Scale bar represents 200 μm, and arrows indicate metastatic area. G: The ratio of pulmonary metastasis was determined from 8- to 17-week-old PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice (n = 30 to 32 per groups). Graph is represented by percentage of mice that have free metastasis. Survival curve was analyzed with a Log-rank test, P = 0.0036 versus PyMT.

We determined metastatic growth by histological analysis of H&E-stained pulmonary tissues by counting the incidence of pulmonary metastasis in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse compared with PyMT during tumor progression (Figure 2, F and G). The number of metastatic lesions was observed to be significantly lower in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice compared with PyMT mice at 16 weeks of age (Figure 2F). PyMT mice presented the median survival (50% of mice are free of metastasis) at around 15 weeks of age, whereas those in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice were at 17 weeks suggesting that LEPR-B deficiency causes significant delay of pulmonary metastasis (Figure 2G). We further observed no significant differences in the degree of hypoxia, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis, as determined by immunostaining with a hypoxia probe, a blood vessel marker (CD31), blood vessel density (lectin), a lymphatic vessel marker (podoplanin), or by measuring mRNA levels for angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis (see supplemental Figure 2, A–E, respectively, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Therefore, angiogenesis was shown to occur normally, and a similar degree of hypoxic conditions was evident in both PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse and PyMT mouse models. It is also important to note that angiogenesis can occur normally despite a decrease of leptin receptor-mediated signaling, which is well established as a pro-angiogenic pathway.22,23 One reason for this occurrence may be that in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice, the PI3K pathway remains highly activated; this may be a crucial determinant in tumor angiogenesis, cooperating with PTEN through regulation of HIF1α and vascular endothelial growth factor expression.24 Taken together, we conclude that LEPR-B mediated-signaling is a requirement for efficient tumor progression and pulmonary metastasis in our model of PyMT-driven Ras- and PI3K-dependent tumorigenesis in vivo.

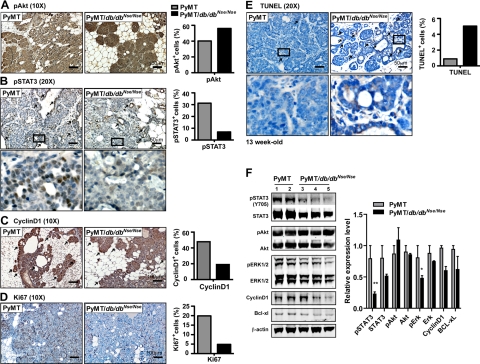

LEPR-B-Mediated Activation of the ERK1/2 and STAT3 Pathways Is Attenuated in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse Mice

Leptin induces cell proliferation in a number of breast cancer cell lines, along with improvements in survival, enhanced invasion, and angiogenesis. These effects are primarily achieved through activation of that LEPR-B that consequently stimulates Jak2/STAT3, ERK1/2, and PI3K pathways.25,26,27 The MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor mouse model undergoes distinct stages of tumor progression and metastasis under the control of Ras- and PI3K-dependent tumorigenesis, activated by PyMT (polyoma virus middle T antigen).28,29 To explore the molecular mechanisms of LEPR-B-mediated mammary tumor progression, we analyzed the downstream pathways of the LEPR-B, such as PI3K, ERK1/2, and Jak2/STAT3, and by immunohistochemistry and immunoblottings we compared tumor tissues from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice with tissues from PyMT mice at 13 weeks of age. The PI3K pathway, as judged by the phosphorylation state of Akt, was no significantly different between the two groups (Figure 3, A and F), whereas the degree of ERK1/2 activation was moderately decreased (Figure 3F). Furthermore, both the total levels of STAT3 and its activated form, pSTAT3 (Y705), were significantly decreased in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice when compared with PyMT mice (Figure 3, B and F); this may occur as a consequence of a lowered positive feedback mechanism regulated by STAT3 itself.30 These results therefore indicate that PyMT initiated tumorigenesis can activate PI3K but fails to fully activate the STAT3 and ERK1/2 pathways in the absence of a LEPR-B signaling system.

Figure 3.

LEPR-B mediated downstream signals, including ERK1/2 and STAT3 activities, are attenuated in tumor tissues of PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse, resulting in decrease of cell proliferation and anti-apoptosis. The activation of LEPR-B downstream signal, (A) PI3K-Akt, and (B) Jak2/STAT3 was evaluated by immunostaining with pAkt and pSTAT3 (Y705) antibodies with tumor tissues from 13-week-old PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice, respectively. Proliferating cells in mammary tumor tissues were determined by immunostaining with (C) cyclin D1 and (D) Ki-67 antibodies. E: Apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay. Arrows indicate staining positive cells. Results were quantified with Image J software and represented by percentage of total number of cells. The scale bar is represented in the images. The bottom panels of (B) pSTAT3 and (E) TUNEL represent higher magnification images for the squared boxes in the upper panels. F: Phosphorylation states of STAT3, Akt, and ERK1/2 as well as cyclinD1 and Bcl-xl were determined by immunoblotting. Results were normalized with β-actin and quantification values are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 per each group). **P < 0.01 versus PyMT; *P < 0.05 versus PyMT by t-test.

It is well established that constitutive activation of the STAT3 pathway is required for tumor cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, and metastasis, as well as tumor immune suppression in various types of cancers.31,32,33 Therefore, a decrease in STAT3, and the well-established mitogenic ERK1/2 pathway, could account for significant attenuation of tumor growth and pulmonary metastasis in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice when compared with PyMT mice. Accordingly, we observed that the degree of cell proliferation was significantly lower in tumor tissues from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice in comparison with PyMT mice, as judged by the intensity of cyclinD1 and Ki-67 immunostaining (Figure 3, C and D, respectively). In contrast, the level of cellular apoptosis was dramatically increased (Figure 3E, “TUNEL”). Alternatively, several pSTAT3 target-genes that are responsible for cellular proliferation and the anti-apoptotic properties of cancer cells,34 such as cyclinD1, c-myc, and Bcl-xl, were not significantly altered in tumor tissues from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice (see supplemental Figure 3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Collectively, these data suggest that the canonical Jak2/STAT3 pathway for primary tumor growth can be completely compensated for by a Ras- and PI3K-dependent tumorigenic pathway in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. This result further reminds us that Ras-dependent tumorigenesis is less dependent on the canonical pSTAT3 pathway in vitro.35 Similarly, a STAT3-deficient MMTV-ErbB2 driven mammary tumor model develops primary tumors at a rate similar to wild type mice but displays dramatically attenuated pulmonary metastasis in vivo.36 Therefore, we conclude that ERK1/2 and/or noncanonical STAT3 pathways are responsible for a decrease in tumor growth in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice rather than the canonical pSTAT3 pathway involving STAT3 as a transcription factor. Nevertheless, the decrease in canonical pSTAT3 pathway signaling in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice may explain the significant differences in pulmonary metastasis shown here (Figure 2, F and G); this is consistent with previous in vivo observations.36

To further address the molecular mechanisms underlying the physiological role of LEPR-B-mediated pathways on mammary tumor progression, we subjected tumor tissues to microarray analysis. Surprisingly, gene sets related to mitochondrial function and extracellular matrix components were differentially affected between two groups. Most other pathways were quite comparable between the two groups, including pSTAT3 target genes (see supplemental Figure 3, A and B, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These observations were independently confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis (see supplemental Figure 3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

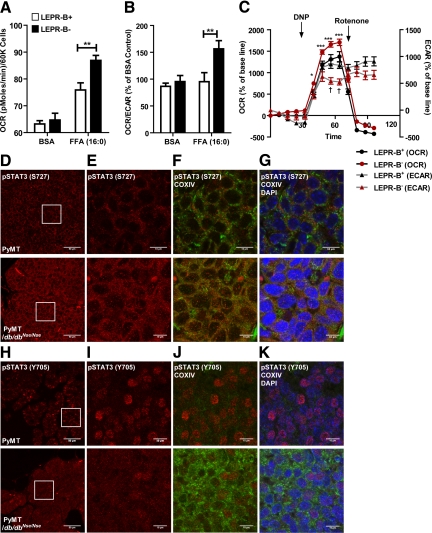

LEPR-B Deficient Tumor Cells Have a Higher Capacity for Mitochondrial Respiration

The results above prompted us to examine the mitochondrial function of tumor cells in the PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice more closely with respect to cancer cell metabolism. Generally, tumor cells display a high metabolic rate of glucose uptake and lipid synthesis compared with nontransformed cells, which enables them to generate new cellular building blocks effectively to support their massive rate of proliferation.37,38 From a metabolic perspective, leptin is a catabolic factor driving lipid consumption and repressing de novo triglyceride synthesis through the action of its receptor in both central and peripheral tissues.10 However, the impact of leptin signaling on tumor cell metabolism is poorly understood. We therefore ask, what are the consequences in a lack of leptin receptor-mediated signaling on tumor cell metabolism in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice? To address this question, we first compared mRNA levels of genes responsible for glucose metabolism, lipogenesis and β-oxidation, in addition to mitochondria encoded genes, such as ATP synthase (ATP6, ATP synthase F0 subunit 6) and Complex IV (COX1 and COXIII, cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 and 3) comprising components of both mitochondrial electron transport chain and nuclear encoded mitochondrial genes, such as NRF1 (nuclear respiratory factor-1), in tumor tissues from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse and PyMT at 13 weeks. However, these genes were not significantly altered by an absence of the LEPR-B (see supplemental Figure 3C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

To further investigate any potential differences at the functional level, we directly analyzed mitochondrial function within mammary tumor epithelial cells (“METs”) derived from PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. We used tumor tissues with a comparable degree of progression in 13-week-old PyMT and 16-week-old PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice to rule out metabolic differences due to the different tumor stages at comparable ages between the two genotypes. We determined the capacity of β-oxidation of lipids in tumor cells with or without LEPR-B to assess whether LEPR-B-mediated signaling was required for tumor cell metabolism in the context of an obese lipid-rich metabolic environment. Interestingly, the level of free fatty acid-stimulated mitochondrial respiration, as judged by OCR (pmoles/min), was significantly increased in LEPR-B− cells relative to LEPR-B+ cells (Figure 4A). A comparison of the ratio of OCR versus extracellular acidification rate (ECAR; mpH/min; ECAR reflecting glycolysis) revealed that LEPR-B− MET cells efficiently used mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to metabolize free fatty acids, a phenomenon clearly absent in LEPR-B+ MET cells (Figure 4B). We also determined the response of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis on exposure to a mitochondrial membrane potential uncoupling agent (2,4-DNP, 100 μmol/L), which generally increases overall cellular metabolism, to trigger a rise in both OCR and ECAR. In the LEPR-B+ MET cells, the glycolytic rate was efficiently increased in response to the uncoupling agent when compared with the LEPR-B− cells. In contrast, mitochondrial respiration was higher in LEPR-B− cells (Figure 4C). This data suggest that LEPR-B− cells preferentially increase mitochondrial respiration rather than increase glycolysis to balance their energy production. Subsequent addition of a mitochondrial complex-I inhibitor (rotenone, 100 nmol/L) elicited a rapid decrease of OCR in both cells due to an inhibition of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. In contrast, ECAR remained higher in LEPR-B+ cells when compared with LEPR-B− cells, reflecting the reduced capacity of LEPR-B− cells to use glycolysis to generate ATP in the context of reduced mitochondrial respiration (Figure 4C). These results strongly suggest that LEPR-B mediated signaling is required to support cancer cell metabolism in mammary tumor cells to enable the cells to use aerobic glycolysis (“Warburg effect”), while suppressing the cells’ capacity to perform lipid β-oxidation. Interestingly, these observations in tumor cells are in stark contrast to the metabolic effects of leptin in nontransformed cells. In nontransformed cells, leptin enhances β-oxidation. Therefore, to examine whether LEPR-B-mediated metabolic effects on tumor cells are leptin-dependent or leptin-independent, both MET cell-types were pre-incubated for 24 hours with leptin (1 nmol/L), and OCR was subsequently measured. A leptin-mediated increase of OCR was quite limited in both MET cells (data not shown), suggesting that the efficacy of leptin-mediated mitochondrial respiration in tumor cells plays a very minor role. Taken together, we conclude that metabolic perturbations caused by LEPR-B deficiency lead to an unfavorable metabolic status in tumor cells.

Figure 4.

LEPR-B-deficient mammary epithelial tumor cells (MET) that originated from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse have higher capacity of mitochondrial respiration, which is correlated with increase of mitochondrial pSTAT3 (S727). A–C: Primary MET were isolated from 13-week-old PyMT and 16-week-old PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. Cells (0.6 × 105) were seeded into each well 1 day before analysis. Contributions of mitochondria respiration and glycolysis in response to free fatty acid (palmitate, 200 μmol/L) challenge, uncoupler (2,4-DNP, 100 μmol/L), and complex I inhibitor (rotenone, 100 nmol/L) were analyzed by using XF-24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). A: Mitochondria respiration (OCR) after treatment with either BSA or FFA is represented as the mean ± SEM (five replicates per each group). **P < 0.01 versus LEPR-B+ by two-way analysis of variance (no matching). B: The ratio of mitochondria respiration versus glycolysis after treatment with either BSA or FFA were represented by percentage of BSA treated LEPR-B+ control. **P < 0.01 versus LEPR-B+ by two-way analysis of variance (no matching). Each experiment was performed duplicate with independent cohorts. C: Metabolic changes of OCR and ECAR in response to uncoupler and inhibitor of mitochondria electron transport chain, complex I were analyzed simultaneously. Results were represented by percentage of base line, mean ± SEM (five replicates per each group). *P < 0.05 versus LEPR-B+ OCR; ***P < 0.001 versus LEPR-B+ OCR; †P < 0.05 versus LEPR-B+ ECAR, by two-way analysis of variance with repeated measures in each time point (matching by each groups). LEPR-B+ and LEPR-B− stands for MET cells with or without LEPR-B, respectively. D–K: Analysis of the states of STAT3 phosphorylation and its cellular localization in tumor tissues from PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. pSTAT3 (S727) and pSTAT3 (Y705) were imaged by red fluorescence (Cy3) (D and H) and higher magnification images of squared box in Figure 4, D and H, are shown in E and I, respectively, which was co-stained with COXIV (mitochondria, green; F and J) and merged with DAPI (nucleus, blue; G–K). Images were analyzed with Image J software. The scale bar is represented in the images.

Mitochondrial pSTAT3 (S727) Signaling Is Associated with a Higher Capacity of Mitochondrial Respiration in LEPR-B Deficient Tumor Tissues

To identify the molecular links between LEPR-B signaling and tumor cell metabolism, we firstly focused on the LEPR-B-mediated STAT3 pathway that we had previously shown to be significantly lower in tumor tissues from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse (Figure 3F). The cellular localization and phosphorylation status of STAT3 is crucial for its diverse cellular functions.39 A recent study documented that a noncanonical STAT3 pathway was mediated through mitochondrial pSTAT3 (S727).35,40 The authors of this study proposed a tight correlation between the level of pSTAT3 (S727) and mitochondrial oxidative respiration. In light of this, the precise functional role of mitochondrial pSTAT3 signaling in mammary tumorigenesis remains to be elucidated. We therefore investigated the subcellular localization and phosphorylation status of STAT3 in tumor tissues derived from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse and PyMT mice by immunostaining with antibodies for pSTAT3 (S727), pSTAT3 (Y705), and cytochrome c oxidase (ComplexIV, COXIV, used here as a mitochondria marker). Overall, the amount of pSTAT3 (S727) was considerably higher in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse tissues when compared with PyMT tissues (Figure 4, D and E). The staining was shown to overlap the signal of COXIV (Figure 4, F and G), thus reflecting an increase in the level of mitochondrial pSTAT3 (S727) in LEPR-B deficient tumor tissues. This is consistent with the postulated positive role that pSTAT3 (S727) exerts on mitochondrial oxidative respiration35,40 as shown in Figure 4, A and B. On the other hand, pSTAT3 (Y705) was significantly decreased in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse tissues when compared with PyMT tissues (Figure 4, H and I). pSTAT3 (Y705) is predominantly localized within the nucleus, rather than the cytosol or mitochondria (Figure 4, J and K). This suggests that the action of pSTAT3 (Y705) as a transcription factor is attenuated in the absence of LEPR-B. We therefore report an inverse correlation between pSTAT3 (Y705) and pSTAT3 (S727) in mammary tumor tissues in response to LEPR-B deficiency. The increased mitochondrial pSTAT3 (S727) in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse is triggered by a LEPR-B independent pathway. Consistent with that, we fail to see leptin-mediated increases of pSTAT3 (S727) in wild-type tumor cells; however, we easily observe pSTAT3 (Y705) under these conditions (data not shown). The defined molecular mechanism and the kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of pSTAT3 (S727) remain to be identified.

Tumor Growth Is Faster in a High Leptin Environment whereas LEPR-B Deficient Tumor Displays Delayed Progression

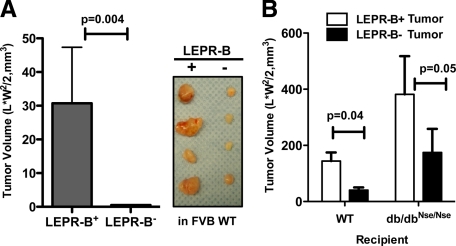

We finally wanted to establish whether LEPR-B-mediated signaling accelerates mammary tumor progression in a cell autonomous fashion, independent of the metabolic state of the mouse, which may slightly differ in between the two genotypes. MET cells or intact tumor tissues with or without leptin receptor were therefore transplanted into recipient mice (either db/dbNse/Nse or their control littermates). After transplantation of the equivalent number of LEPR-B+ and LEPR-B− MET cells into wild-type mice, tumor progression was monitored (Figure 5A). The growth rate of LEPR-B− cells was significantly attenuated, relative to LEPR-B+ MET cells (Figure 5A). For tissue transplantation, LEPR-B− or LEPR-B+ tumors obtained from PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse and PyMT mice, respectively, at 14 weeks of age, were used as a donor tissue. We have shown that the db/dbNse/Nse mice exhibit higher circulating leptin levels in comparison with wild-type mice due to the lack of peripheral leptin receptor signaling. Following on from this, we therefore examined the effects of higher circulating leptin on the growth of either LEPR-B+ or LEPR-B− tumors in vivo. Comparable pieces of each donor tumor genotypes were transplanted into wild-type and db/dbNse/Nse mice and their subsequent growth was monitored and quantified over 6 weeks after transplantation (Figure 5B). The growths of LEPR-B-tumors were dramatically attenuated under both normal and high leptin conditions compared with LEPR-B+ tumors (Figure 5B). Furthermore, LEPR-B+ tumor growth was significantly enhanced under an elevated level of leptin environment (Figure 5B); this suggests that the LEPR-B+ tumors are highly responsive to leptin and experience a potent growth stimulus under these conditions of constitutive elevation of leptin levels.

Figure 5.

LEPR-B deficiency attenuates tumor growth in both wild-type and db/dbNse/Nse mice, whereas tumors with LEPR-B grow faster in db/dbNse/Nse mice than wild-type mice. A: MET cells (0.15 × 106) isolated from 13-week-old PyMT and 16-week-old PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice were transplanted into inguinal mammary fat pad of FVB wild-type mice. Tumor growth was analyzed 6 weeks after transplantation. Results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 10). P = 0.004 versus LEPR-B+ by t-test. B: Tumor transplantation analysis to assess microenvironment effects on tumor growth. Donor tumor tissues were obtained from tumor size controlled 14-week-old PyMT and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. A piece of PyMT tumor (LEPR-B+) and PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse tumor (LEPR-B−) was implanted into the right and left side of inguinal mammary fat pad of either wild-type or db/dbNse/Nse mice, respectively. Tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed to analyze tumor progression after 6 weeks of transplantation. Tumor volume was determined by caliper measurements, and results are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). P = 0.04 in WT and P = 0.05 in db/dbNse/Nse mice versus LEPR-B+ by t-test.

Discussion

In the context of an obese host, mammary adipose tissue supplies higher levels of leptin to the tumor microenvironment as a consequence of central leptin resistance. However, the direct relationship that obesity has on enhanced tumor progression through leptin will require further investigation. A key weakness in the epidemiological studies to date is the notion that circulating leptin levels may not necessarily act as a suitable indicator of the local leptin concentrations within the mammary gland. Our studies emphasize an intense paracrine cross talk along the leptin-axis between adipocytes and tumor cells; this implies that the local leptin levels within the mammary gland are much more relevant, albeit they are equally more difficult to assess.

Based on previous in vitro observations, leptin antagonists bear a high degree of promise as therapeutic targets in the treatment of breast cancers; however, there have been no in vivo studies that have examined their use in tumorgenesis before our report. In the PyMT mammary tumor model, leptin receptor levels are highly induced in tumor tissues with only minimal changes in circulating leptin levels during tumor progression. Leptin has been shown to activate PI3K, ERK1/2, and STAT3 pathways through the LEPR-B, pathways that are coordinately activated in tumor tissues to support growth and survival. Here, we identified that a functional LEPR-B deficiency in PyMT mice is sufficient to cause a defect in its downstream signaling events. In particular, components such as Jak2/STAT3 and ERK1/2 are affected in a model that spontaneously develops tumors through a Ras- and PI3K-dependent pathway mediated by the PyMT transgene. Constitutive activation of STAT3 and ERK1/2 are well-established key oncogenic stimuli, which sustain various cell-types for tumor progression and metastasis and further, mediate poor prognosis after cancer therapy.41,42 We determined that mammary tumor progression from hyperplasia to late carcinoma is significantly delayed in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice when compared with PyMT mice, through a decrease in tumor cell proliferation accompanied with a dramatic increase in tumor cell apoptosis; the latter results from a decrease in signaling in the ERK1/2 and STAT3 pathways. The significant decrease of the STAT3 signaling pathway in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice can be accounted for by the dramatic attenuation of pulmonary metastasis, a phenomenon previously reported for STAT3-deficient MMTV-ErbB2 mice.36 Here, we further demonstrated comparable levels of hypoxia, angiogenesis, and lymph angiogenesis in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice. This could be a result of the PI3K pathway being actively involved in tumor angiogenesis in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice, thus compensating for the attenuated STAT3 and ERK activity.

Since leptin is a key regulator of energy homeostasis in peripheral tissues, we evaluated leptin effects on tumor metabolism. Surprisingly, we found that LEPR-B deficient tumor cells can use mitochondrial β-oxidation to a greater extent than cells with intact LEPR-B. Why would tumor cells retain the mitochondrial β-oxidation pathway in PyMT/db/dbNse/Nse mice? One possible explanation is that tumor cells under hyperleptinemic (ie, “leptin resistant”) conditions (observed frequently in obese subjects) attempt to use fatty acids as an energy source.43,44 However, a more plausible explanation for our observations may be that LEPR-B− tumor cells exhibit an enhanced propensity for β-oxidation in comparison to LEPR-B+ cells; this suggests that LEPR-B− tumor cells have not yet lost their ability to take advantage of β-oxidation, whereas their LEPR-B+ counterparts rely much more on the aerobic glycolytic characteristics of later stage aggressive tumors. The LEPR-B− tumor cells therefore retain a more “conventional” approach to energy generation through the β-oxidation characteristics of terminally differentiated, nontransformed cells. More specifically, the LEPR-B− cells retain a metabolic function for ATP generation, thus resembling the metabolic status of an “earlier stage” tumor cell.

Taken together, we have established that LEPR-B-mediated downstream signaling is required for cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis, in addition to tumor cell metabolism involving an enhancement in the classically described Warburg effect. Under obese conditions, tumor cells face a microenvironment that exhibits high local leptin, which parallels an increase in stimulation of LEPR-B-mediated pathways; these include enhanced PI3K, ERK1/2, and STAT3 activation, which eventually accelerate tumor progression. Thus, leptin receptors have unique properties and orchestrate mammary tumor progression in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jie Song, Steven Connell, and Xinyu Wu for technical assistance. We would like to thank the Metabolic Phenotyping Core and the Molecular Pathology Core, the DNA Microarray Core, and the Live Cell Imaging Core (UT Southwestern) for their help at various stages of this work, as well as the rest of the Scherer, Unger, and Clegg laboratories for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests Philipp E. Scherer, Ph.D., Touchstone Diabetes Center, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX 75390-8549. E-mail: Philipp.Scherer@utsouthwestern.edu.

Supported by NIH grants R01-DK55758, R01-CA112023, P01DK088761 (P.E.S.), and DK081182 (Jay Horton) and post-doctoral fellowship from the Department of Defense (USAMRMC BC085909 to J.P.) and from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation (JDRF 3-2008-130 to C.M.K.) as well as the New York Nutrition Obesity Research Center, P01 DK2667.

A guest editor acted as editor-in-chief for this article. No person at Thomas Jefferson University or Albert Einstein College of Medicine was involved in the peer review process or final disposition for this article.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle EE, Thun MJ. Obesity and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:6365–6378. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F, Michels KB. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer: a review of the current evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:S823–S835. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.823S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose DP, Komninou D, Stephenson GD. Obesity, adipocytokines, and insulin resistance in breast cancer. Obes Rev. 2004;5:153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housa D, Housova J, Vernerova Z, Haluzik M. Adipocytokines and cancer. Physiol Res. 2006;55:233–244. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landskroner-Eiger S, Qian B, Muise ES, Nawrocki AR, Berger JP, Fine EJ, Koba W, Deng Y, Pollard JW, Scherer PE. Proangiogenic contribution of adiponectin toward mammary tumor growth in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3265–3276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar P, Combs TP, Shah SJ, Gouon-Evans V, Pollard JW, Albanese C, Flanagan L, Tenniswood MP, Guha C, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG, Scherer PE. Adipocyte-secreted factors synergistically promote mammary tumorigenesis through induction of anti-apoptotic transcriptional programs and proto-oncogene stabilization. Oncogene. 2003;22:6408–6423. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margetic S, Gazzola C, Pegg GG, Hill RA. Leptin: a review of its peripheral actions and interactions. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1407–1433. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muoio DM, Lynis Dohm G. Peripheral metabolic actions of leptin. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;16:653–666. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo C, Koda M, Cascio S, Sulkowska M, Kanczuga-Koda L, Golaszewska J, Russo A, Sulkowski S, Surmacz E. Increased expression of leptin and the leptin receptor as a marker of breast cancer progression: possible role of obesity-related stimuli. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1447–1453. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Kitayama J, Nagawa H. Enhanced expression of leptin and leptin receptor (OB-R) in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4325–4331. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vona-Davis L, Rose DP. Adipokines as endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine factors in breast cancer risk and progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:189–206. doi: 10.1677/ERC-06-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Luca C, Kowalski TJ, Zhang Y, Elmquist JK, Lee C, Kilimann MW, Ludwig T, Liu SM, Chua SC., Jr Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron-specific LEPR-B transgenes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3484–3493. doi: 10.1172/JCI24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberg N, Khan T, Trujillo ME, Wernstedt-Asterholm I, Attie AD, Sherwani S, Wang ZV, Landskroner-Eiger S, Dineen S, Magalang UJ, Brekken RA, Scherer PE. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha induces fibrosis and insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4467–4483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00192-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Juneja SC, Maihle NJ, Cleary MP. Leptin: a growth factor in normal and malignant breast cells and for normal mammary gland development. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1704–1711. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.22.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary MP, Phillips FC, Getzin SC, Jacobson TL, Jacobson MK, Christensen TA, Juneja SC, Grande JP, Maihle NJ. Genetically obese MMTV-TGF-alpha/Lep(ob)Lep(ob) female mice do not develop mammary tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77:205–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891825399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary MP, Juneja SC, Phillips FC, Hu X, Grande JP, Maihle NJ. Leptin receptor-deficient MMTV-TGF-alpha/Lepr(db)Lepr(db) female mice do not develop oncogene-induced mammary tumors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:182–193. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski TJ, Liu SM, Leibel RL, Chua SC., Jr Transgenic complementation of leptin-receptor deficiency. I. Rescue of the obesity/diabetes phenotype of LEPR-null mice expressing a LEPR-B transgene. Diabetes. 2001;50:425–435. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua SC, Jr, Liu SM, Li Q, Sun A, DeNino WF, Heymsfield SB, Guo XE. Transgenic complementation of leptin receptor deficiency. II Increased leptin receptor transgene dose effects on obesity/diabetes and fertility/lactation in lepr-db/db mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E384–E392. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00349.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouloumie A, Drexler HC, Lafontan M, Busse R. Leptin, the product of Ob gene, promotes angiogenesis. Circ Res. 1998;83:1059–1066. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Honigmann MR, Nath AK, Murakami C, Garcia-Cardena G, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC, Madge LA, Schechner JS, Schwabb MB, Polverini PJ, Flores-Riveros JR. Biological action of leptin as an angiogenic factor. Science. 1998;281:1683–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang BH, Liu LZ. PI3K/PTEN signaling in angiogenesis and tumorigenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2009;102:19–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)02002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez RR, Cherfils S, Escobar M, Yoo JH, Carino C, Styer AK, Sullivan BT, Sakamoto H, Olawaiye A, Serikawa T, Lynch MP, Rueda BR. Leptin signaling promotes the growth of mammary tumors and increases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor type two (VEGF-R2). J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26320–26328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601991200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S, Mauro L, Marsico S, Giordano C, Rizza P, Rago V, Montanaro D, Maggiolini M, Panno ML, Ando S. Leptin induces, via ERK1/ERK2 signal, functional activation of estrogen receptor alpha in MCF-7 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19908–19915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo D, Rachiglio AM, la Montagna R, Giordano A, Normanno N. Leptin signaling in breast cancer: an overview. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:956–964. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglione JE, Moghanaki D, Young LJ, Manner CK, Ellies LG, Joseph SO, Nicholson B, Cardiff RD, MacLeod CL. Transgenic Polyoma middle-T mice model premalignant mammary disease. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8298–8305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Jones JG, Li P, Zhu L, Whitney KD, Muller WJ, Pollard JW. Progression to malignancy in the polyoma middle T oncoprotein mouse breast cancer model provides a reliable model for human diseases. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2113–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63568-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiba M, Nakajima K, Yamanaka Y, Kiuchi N, Hirano T. Autoregulation of the Stat3 gene through cooperation with a cAMP-responsive element-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6132–6138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Jove R. The STATs of cancer–new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:97–105. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Niu G, Kortylewski M, Burdelya L, Shain K, Zhang S, Bhattacharya R, Gabrilovich D, Heller R, Coppola D, Dalton W, Jove R, Pardoll D, Yu H. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:48–54. doi: 10.1038/nm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortylewski M, Yu H. Role of Stat3 in suppressing anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, Darnell JE., Jr Stat3 as an oncogene. Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough DJ, Corlett A, Schlessinger K, Wegrzyn J, Larner AC, Levy DE. Mitochondrial STAT3 supports Ras-dependent oncogenic transformation. Science. 2009;324:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1171721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri I, Quaglino E, Maritano D, Pannellini T, Riera L, Cavallo F, Forni G, Musiani P, Chiarle R, Poli V. Stat3 is required for anchorage-independent growth and metastasis but not for mammary tumor development downstream of the ErbB-2 oncogene. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:114–120. doi: 10.1002/mc.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich NC. STAT3 revs up the powerhouse. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe61. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.290pe61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegrzyn J, Potla R, Chwae YJ, Sepuri NB, Zhang Q, Koeck T, Derecka M, Szczepanek K, Szelag M, Gornicka A, Moh A, Moghaddas S, Chen Q, Bobbili S, Cichy J, Dulak J, Baker DP, Wolfman A, Stuehr D, Hassan MO, Fu XY, Avadhani N, Drake JI, Fawcett P, Lesnefsky EJ, Larner AC. Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science. 2009;323:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg J, Darnell JE., Jr The role of STATs in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene. 2000;19:2468–2473. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YT, Shimabukuro M, Koyama K, Lee Y, Wang MY, Trieu F, Newgard CB, Unger RH. Induction by leptin of uncoupling protein-2 and enzymes of fatty acid oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6386–6390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L, Cook WS, Ravazzola M, Wang MY, Park BH, Montesano R, Unger RH. Rapid transformation of white adipocytes into fat-oxidizing machines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2058–2063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308258100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]