Abstract

Primary vasculitis is the result of idiopathic inflammation in blood vessel walls. T cells are believed to play a critical role, but the nature of the pathological T-cell response remains obscure. In this study, we provide evidence that CD4+ T lymphocytes, activated in the presence of syngeneic vascular smooth muscle cells, were sufficient to induce vasculitic lesions after adoptive transfer to recipient mice. Additionally, the disease is triggered in the absence of antibodies in experiments in which both the donors of stimulated lymphocytes and the transfer recipients were mice that were deficient in B cells. Tracking and proliferation of the transferred cells and their cytokine profiles were assessed by fluorescence tagging and flow cytometry. Proliferating CD4+ T cells were evident 3 days after transfer, corresponding to the occurrence of vasculitic lesions in mouse lungs. The transferred T lymphocytes exhibited Th1 and Th17 cytokine profiles and minimal Th2. However, 1 week after vasculitis induction, effector functions could be successfully recalled in Th1 cells, but not in Th17 cells. Additionally, in the absence of constitutive interferon-γ expression, T cells sensitized by vascular smooth muscle cells failed to induce vasculitis. In conclusion, our results show that Th1 cells play a key role in eliciting vasculitis in this murine model and that induction of the disease is possible in the absence of pathogenic antibodies.

Systemic vasculitis syndromes are immune vascular disorders that run a progressive course and are frequently fatal due to vital organ failure following vessel inflammation and obliteration.

A role for antigen-specific T cell-mediated pathogenic mechanisms became evident when associations of vasculitis with HLA alleles were established.1 Studies on biopsies from patients with large-vessel vasculitides suggested that T cells infiltrating the vessel wall might become activated after presentation of a local antigen by adventitial dendritic cells.2,3 Evidence that antigen-specific T cell populations clonally expand came from spectratype analysis of T cell receptor (TCR) J segments and flow cytometry detection of TCR V segments usage, both in our animal model4 and, most interestingly, in several human vasculitides including giant cell arteritis and Behcet’s disease.5,6 Importantly, T cell depletion in vasculitis patients using anti-thymocyte globulin or anti-T cell monoclonal antibodies, although triggering severe immunodeficiency, has led to remissions in small open-label studies, highlighting the critical role of T cells in the pathogenesis of vasculitis.7,8

Nevertheless, the exact nature of the pathological T-cell response in vasculitis remains obscure. T helper (Th) 2 cells are credited for the main contribution to pathology in autoantibody-associated vasculitides through antigen-driven T cell help provided to B cell isotype switching.9 Th1 cells are suspected immune players in large vessel vasculitis, where interferon gamma (IFNγ) production was evidenced locally in tissue-infiltrated CD4+ T cells or systemically, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.10,11 The possible role of Th17 in vasculitis has attracted recent attention with reports of increased interleukin (IL)−17 serum levels and higher frequency of IL-17-producing T cells in peripheral blood of vasculitis patients.12,13 Failure of regulatory T cells to control persistent T cell activation may also play a role in vasculitis pathology,14 possibly a result of mechanisms such as reduced IL-10 production15 or surface CD134/OX40 over-expression.16,17

To gain an insight on the role of T cells in vasculitis, we used an inducible murine model of vasculitis that permits the tracking and control of T cell subpopulations and assessment of their kinetics in vivo. In this model, transfer of lymphocytes to syngeneic mice, after in vitro sensitization by co-culture with syngeneic vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), results in systemic autoimmune lymphocytic vasculitis in the recipients, which bears resemblance to human Wegener granulomatosis.18 Previous research indicated that autoantibodies developed in the vasculitic mice and were pathogenic after passive transfer into healthy recipients.19 Additionally, autoreactive CD4+ T cells were specifically activated in co-culture with vascular SMC, and this process depended on major histocompatibility complex class II–T cell receptor interactions4 suggesting that CD4+ T cells might play a pathogenic role in vasculitis. In the current study we aimed to exclude the participation of autoantibody-mediated pathogenic mechanisms in order to identify T cell-mediated immune mechanisms in order responsible for vasculitis induction in the absence of B cells. We found that CD4+ T cells sensitized by vascular SMCs can induce vasculitis and that IFNγ is essential to the induction of vascular pathology in this murine model of vasculitis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice of the BALB/c, B cell-deficient (C.129(B6)Jhd) and RAG2-deficient (C.129(B6)-Rag2) strains were from Taconic (Germantown, NY). C57BL/6, green-fluorescent protein (GFP) (B6.129S7-GFP) and IFN-γ-deficient (B6.129S7-Ifng) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Experiments were in agreement with guidelines of the National Institutes of Health, and approved by the Animal Research Committee of the W. S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital and the University of Wisconsin Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue Culture

Smooth muscle cells/pericytes (labeled henceforth SMCs) from microvasculature were isolated from brain as previously described20 and were 94 to 99% pure as confirmed by immunofluorescence using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-smooth muscle α-actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Previous experiments indicated that large vessel (aorta) SMCs have not been effective in inducing an autoimmune reaction in mice. Primary cultures were maintained for a maximum of eight passages in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Bio Whittaker, Walkersville MD), 4 mmol/L l-Glu, 10 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 50 μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol.

Vasculitis Induction

Vasculitis was induced as previously described.19 Briefly, freshly isolated splenocytes from naïve mice were co-cultured for 6 days with irradiated syngeneic SMC monolayers. Lymphocytes were harvested and transferred intravenously into syngeneic 6-to 12-week-old mice (6 × 106 lymphocytes/mouse), sex-matched to avoid immune reactivity to gender-related antigens. Control animals were either noninjected littermates or mice injected with naïve mouse splenocytes, or with SMCs alone, as stated. Mice were weighed and euthanized at 1, 3, 7, or 10 days postadoptive transfer and peripheral blood, lung, kidney, liver, spleen, or lymph nodes were collected and processed for flow cytometry or for tissue evaluation. Serum l-lactate hypoxia marker was evaluated by a colorimetric assay (BioVision, Mountain View, CA). Vasculitis incidence was scored by two blinded separate investigators on 4 μm H&E-stained lung sections by reporting the number of vessels bearing vasculitis lesions in a total of 300 small blood vessels counted over a surface of 30 to 50 mm2 (cross-sections of three separate lung lobes).

Flow Cytometry

Mononuclear cell suspensions were prepared from organs collected from perfused mice. Lymphoid organs were homogenized to single-cell suspensions with frosted glass slides and erythrocytes lysed. Lungs were minced in dissociation buffer (1 mg/ml Collagenase II, 0.1 mg/ml DNase I, 1% bovine serum albumin in Ca Mg -free saline) for 30 minutes; cells were forced through 70-μm cell strainers (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and lymphocytes were isolated on 30% to 50% Percoll step gradients. T cell surface activation and differentiation markers were tested with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies to CD45RB, CD11a, CD25, Tim3 (T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain molecule), CD4, and CD8a, from BD. Immunofluorescence was measured by dual-laser FACSCalibur (BD) or four-laser LSR II (BD) and analyzed with FlowJo 6.4.7 software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Absolute cell numbers were based on the percentage of target cell populations determined by flow cytometry, out of the total number of cells recovered.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Single-cell suspensions of lymphocytes isolated from tissues were cultured for 18 hours at 37°C in supplemented Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium in the presence or absence of 2 μg/ml anti-CD3 (145-2C11) antibody. GolgiStop (BD) was added 5 hours before sample collection. After surface staining with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies, cell suspensions were fixed and permeabilized by Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD) and stained with anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), anti-IL-4 (11B11), anti-IL-10 (JES5-16E3), or anti-IL-17 (TC11-18H10) antibodies (BD). Fluorescence was read on a BD FACSCalibur.

Magnetic Sorting

CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated from preparations of SMC-stimulated lymphocytes by positive selection with iMag anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5) (BD) at 20 μl particles per 107 cells in degassed buffered saline with 2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% bovine serum albumin.

Cell Proliferation

Cells were labeled with 2.5 μmol/L Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), from Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR for 5 minutes at 37°C and then isolated on Lympholyte M (Cedarlane, Hornby, ON, Canada).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Four-micron deparaffinized tissue sections and 6-μm frozen sections of collected organs have been permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and stained with antibodies to CD106, ICAM-2, H-2Dd, H-2IA, CD4, CD8, T-bet, IL-17, CD68 (all from BD), and F4/80 (purified in the laboratory), and counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescence images were acquired with an Optronics camera using QuantiFire 2.1 software.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann-Whitney test and R console were used for nonpaired data distribution analysis. All P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Vasculitis Is Induced in the Absence of Antibodies and B Cells

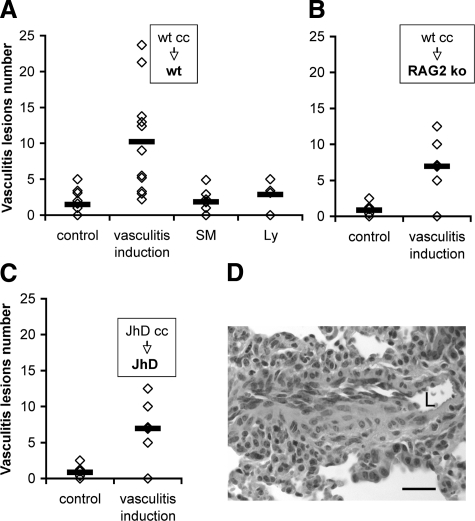

Following adoptive transfer of the sensitized lymphocytes into syngeneic recipients, vasculitis was evidenced in lung, liver, and muscle as previously described,18 and was scored in the lung (Figure 1). We defined vasculitic lesions by inflammation and disruption of blood vessel wall, accompanied by transmural cuffing with more than three layers of infiltrated leukocytes, and presence of leukocytes adherent to, or passing through the endothelium. Mice injected with syngeneic SMCs alone or naïve spleen lymphocytes (Figure 1A) did not develop vasculitis, indicating that primary cultures of SMCs and isolated lymphocytes are not immunogenic. The pathology was directly induced by the adoptively transferred cells without the contribution of host adaptive immune responses, since transfer of sensitized wild-type (wt) lymphocytes to RAG-2 gene-deficient mice induced vasculitis (Figure 1B). Previous studies indicated that autoantibodies directed against leukocyte or blood vessel wall antigens (including anti-SMC antibodies in this model)19 are pathogenic for vasculitis. To determine whether autoantibody-mediated pathology is the sole pathogenic mechanism in this vasculitis model, B cell-deficient mice [C.129(B6)Jhd] have been used both as splenocyte donors for culture with vascular SMCs and as adoptive transfer recipients in vasculitis induction. In this system, only CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were adoptively transferred to recipient mice. Remarkably, vasculitis developed in the absence of B cells and antibodies (Figure 1C) indicating that T cell-mediated pathogenic mechanisms could induce vasculitis independently from B cells in this animal model. In approximately 10% of the B-cell deficient vasculitic mice the vessel wall inflammation presented a granulomatous-like appearance (Figure 1D), a feature associated with cell-mediated pathology. Occasionally, we observed macrophages containing hemosiderin in the vessel wall, indicating a recent hemorrhage, or infiltrated eosinophils, indicating ongoing inflammation (not shown).

Figure 1.

Vasculitis incidence after transfer of SMC-sensitized lymphocytes is similar in wt and in B cell-deficient (JhD) mice. A–C. Vasculitis incidence scored on H&E sections of lung (each diamond depicts a mouse; horizontal bar is average). Control indicates noninjected mice. A: Adoptive transfer of wt BALB/c lymphocytes previously sensitized by co-culture (wt cc) with syngeneic SMC to wt BALB/c recipient mice; n = 11, P = 0.003 (four experiments). SM are mice injected with primary smooth muscle cultures (106 cells/mouse). Ly are mice injected with isolated naïve spleen lymphocytes (5 × 106 cells/mouse). B: Transfer of sensitized wt BALB/c lymphocytes to RAG-2-deficient mice; n = 7, P = 0.006 (3 experiments). C: Transfer of sensitized JhD lymphocytes to JhD mice; n = 12 mice, P = 0.00002 (seven experiments). D: H&E staining of 4-μm paraffin section of lung 7 days after vasculitis induction in JhD mouse, showing blood vessels with granulomatous-like inflammation and infiltration of leukocytes with destruction of vessel wall. L, vessel lumen. Scale bar = 20 μm. Original magnification, ×400.).

CD4+ T Cells Are Pathogenic for Vasculitis

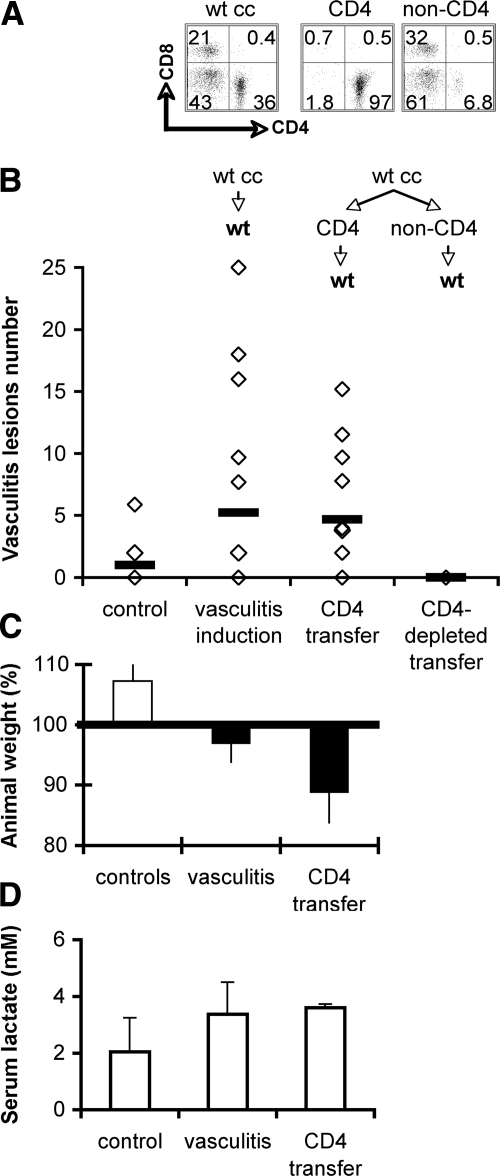

To directly determine whether CD4+ T cells can be autoreactive effectors in vasculitis, we tested CD4+ T cells purified after sensitization by vascular SMCs for their ability to induce disease following adoptive transfer. Highly purified CD4+ T cell populations (>95%) were prepared by positive magnetic sorting from lymphocytes sensitized by culture with SMCs (Figure 2A) and were transferred to syngeneic recipients. Comparison between the outcome of transfers of sensitized whole lymphocyte populations versus purified CD4+ T lymphocytes showed that CD4+ T cells were sufficient to induce vasculitic lesions after adoptive transfer to recipient mice (Figure 2B). Vasculitis was evidenced in 66% of the CD4+ T cell adoptive transfer recipients, while lymphocyte cuffing of blood vessels was observed in all recipient mice. On the other hand, the transfer in a limited number of mice of cell populations depleted of CD4+ T cells did not result in vasculitis in the recipients (Figure 2B). The inflammatory process induced weight loss indicative of distress in some adoptive transfer recipients (Figure 2C) and a modest increase, statistically nonsignificant, in the serum l-lactate (Figure 2D), indicative of mild hypoxia characteristic to inflammatory reactions not accompanied by necrosis. An increase in vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (Figure 3, A and B), major histocompatibility complex class II (Figure 3, C and D), and a decrease in intercellular adhesion molecule-2 (Figure 3, E and F) expression in the vessel wall areas adjacent to heavy cellular infiltrates, all indicated activated endothelium as a hallmark of local inflammation. Taken together, these results indicate that CD4+ T cell-mediated mechanisms could induce vasculitis in this murine model.

Figure 2.

Purified CD4+ T cells sensitized by vascular SMC induce vasculitis after adoptive transfer. A: Flow cytometry of wt BALB/c lymphocytes previously sensitized by co-culture with syngeneic SMCs (wt cc) and subsequently sorted CD4+ cells (CD4) and CD4+ cell-depleted (non-CD4) cell suspensions used for adoptive transfer. B: Vasculitis incidence scored on H&E sections of lungs of recipient mice (each diamond represents a mouse). Control group are non-injected mice. Results from four experiments; n = 12, P = 0.05 for wt cc transfers; n = 12, P = 0.04 for sorted CD4+ T cell transfers; n = 2 for CD4+ cell-depleted transfers. C: Average ± SD of mouse weight at vasculitis day 7. Horizontal line marks starting weight; n = 4. D: Average of serum lactate concentration in experimental animals; n = 2.

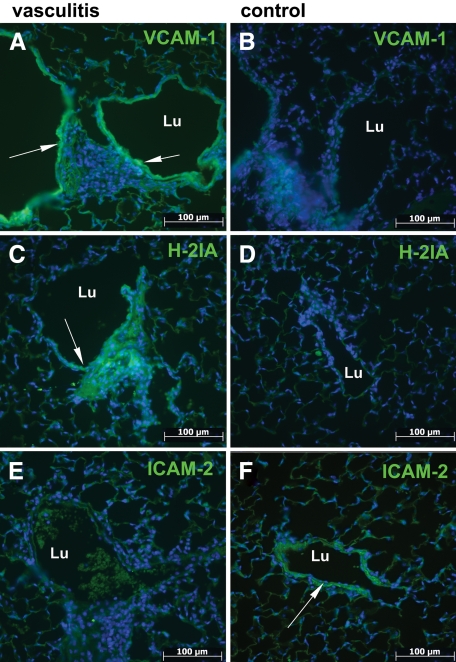

Figure 3.

Vasculitis induction by CD4+ cell transfer results in endothelial activation. Immunofluorescence microscopy on deparaffinized sections of lung shows increased expression of activation markers in vessel wall (A and C) and decrease in resting state markers (E) compared with control non-injected mice (B, D, and F). Lu, vessel lumen. Arrows indicate vessel area of interest. Scale bar =100 μm. Original magnification, ×200.

CD4+ T Cells Infiltrate and Accumulate in Peripheral Organs Affected by Vasculitis

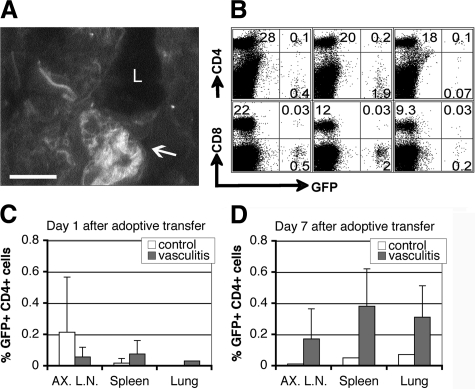

We then determined whether SMC-stimulated CD4+ T cells accumulate in target organs of mice during vasculitis induction when compared with control non-stimulated CD4+ T cells. To directly address this question, splenocytes from donor mice with constitutive GFP expression were used for co-culture with SMCs, and GFP-tagged CD4+ and CD8+ cells were tracked after adoptive transfer into wt recipients with identical haplotype background. At day 7 post-vasculitis induction more mononuclear cells were recovered from the lungs and peripheral lymphoid organs of mice with vasculitis than from those of control mice (data not shown), indicating the existence of an ongoing inflammatory response. Fluorescence microscopy showed clusters of GFP+ cell infiltrates in the vicinity of blood vessels in vasculitic mice (Figure 4A), and flow cytometry analysis indicated a higher frequency of GFP+ CD4+ T cells compared to GFP+ CD8+ T cells infiltrating lymphoid organs and lungs in vasculitic animals (Figure 4, B–D).

Figure 4.

CD4+ T cells infiltrate and accumulate in organs affected by vasculitis. GFP+ lymphocytes sensitized by co-culture with syngeneic SMCs were transferred to wt mice and GFP+ cells were tracked in target organs. A: Fluorescence microscopy on a 5-μm frozen section of lung; arrow indicates GFP+ cell infiltrate in blood vessel wall. L, vessel lumen. Scale bar = 20 μm. Original magnification, ×400. B: Flow cytometry of cell suspensions from axillary lymph nodes (AX.LN), spleen, and lung shows GFP+ T cell infiltrates. C and D depict average ± SD of frequency of CD4+ lymphocyte infiltrates at 1 and 7 days postadoptive transfer to recipient mice, respectively. Results from two experiments (n = 3).

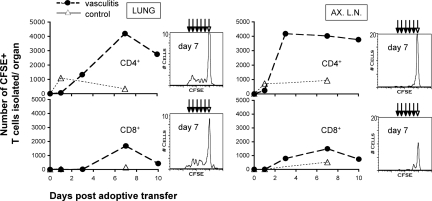

CD4+ T Cells Expand and Persist in Peripheral Organs Affected by Vasculitis

We then investigated whether the transferred CD4+ cells proliferate in the recipient mice. To this end, lymphocytes isolated from splenocytes/SMC co-cultures were labeled with CFSE before adoptive transfer. Flow cytometry analysis showed that CD4+ T cells infiltrated into the lung 1-day postadoptive transfer and were maintained in high numbers in the lung and lymph nodes (Figure 5, upper panels). CD8+ T cells infiltrated the lung several days later after first accumulating in peripheral lymphoid organs, and decreased in numbers faster (Figure 5, lower panels). An analysis of decreasing mean fluorescence intensity of CFSE-labeled infiltrated cells indicated that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells proliferate in lung during the vasculitis induction period, and less so in non-draining lymph nodes (Figure 5, histograms) and spleen (not shown). These results suggest that, after in vitro sensitization with SMCs, CD4+ T cells were activated and differentiated into effector cells. After adoptive transfer to recipients, these cells infiltrated into the periphery, expanded and were likely to have been responsible for the development of vasculitis lesions.

Figure 5.

CD4+ T cells proliferate and persist in peripheral organs of mice with vasculitis. BALB/c SMC-sensitized T lymphocytes labeled with CFSE before adoptive transfer were tracked by four-color flow cytometry at 1, 3, 7, and 10 days in vasculitic mice (vasculitis), and were compared to naïve lymphocyte cell transfers (control). Depicted are the absolute numbers of CFSE+, CD4+, or CD8+ lymphocytes recovered per mouse organ (left panels, lung; right panels, AX.LN, two axillary lymph nodes). Corresponding histograms reflect the decline in CFSE fluorescence intensity in daughter cells (arrows) after division, measured at 7 days postadoptive transfer. Presented are results from one experiment (n = 4 mice per group) of three performed with similar results.

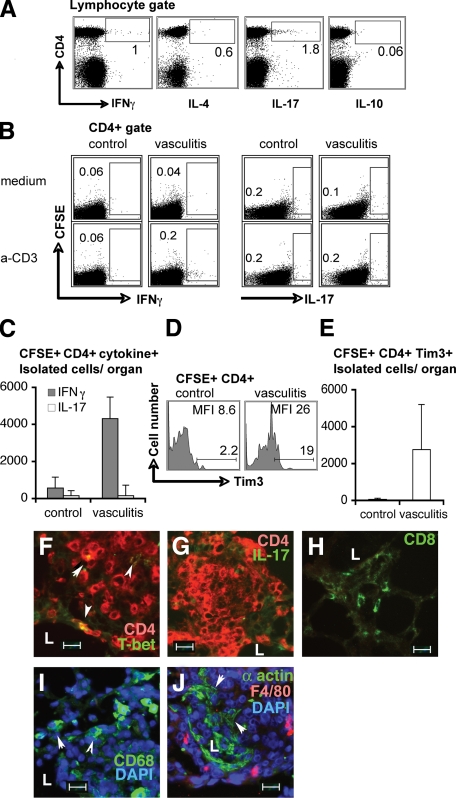

Vasculitis Induction Results in the Preferential Accumulation of Th1 Effector Memory Lymphocytes in the Lung

We then investigated whether a preferential cytokine expression profile exists that might expose the nature of the pathological CD4+ T cell response. Intracellular cytokine staining indicated that small subsets of the CD4+ T cells injected for vasculitis induction expressed either IFNγ or IL-17 (Figure 6A) and no cells expressed both cytokines simultaneously (not shown); very few cells expressed IL-4, and virtually no cells expressed IL-10. However, at 7 days post-vasculitis induction lung-infiltrated CFSE+low CD4+ T cells, restimulated ex vivo with anti-CD3, produced IFNγ, but no stimulation of IL-17 production was detected (Figure 6, B and C), indicating that effector functions can be triggered in memory effector Th1 cells, but not Th17 cells, in vasculitic animals. In control mice, lung-infiltrated CFSE+ (transferred) or CFSE− (host) cells did not enhance IFNγ or IL-17 expression after ex vivo restimulation (Figure 6B, C controls). IL-4–expressing cells (committed to a Th2 lineage) were not detected ex vivo (not shown). An increase in the number of CD25 high–expressing CD4+ cells, suggestive of T regulatory cells, was detected in approximately 50% of the vasculitic mice tested but their frequency did not correlate with the severity of the disease (not shown). In vasculitic mice at 7 days post-vasculitis induction an increased number of CD4+ T cells expressed Tim-3 (Figure 6, D and E), a marker of terminally differentiated Th1 cells but not Th2 or Th17 cells,21 suggesting that Th1 cells persisted in diseased mice when compared with control mice. Lastly, immunofluorescence microscopy of lung lesions showed that the overwhelming majority of cells in perivascular infiltrates of affected vessels are CD4+ cells (Figure 6, F and G) while very few are CD8+ (Figure 6H). Frequent CD4+ cells expressing T-bet (T-box transcription factor regulating lineage commitment of CD4+ cells to Th1), were observed in lesions (Figure 6F) while very few, if any, CD4+ cells expressed IL-17 (Figure 6G), suggesting a preponderance of Th1 cells over Th17 in lesions. Macrophage recruitment in the lesions, as a measure of Th1-mediated cellular responses (Figure 6, I and J) and frequent alteration of vessel wall architecture, reflected by scattering of smooth muscle layer (Figure 6J) were indicative of an inflammatory process. Taken together, these data suggest that Th1 responses are active during vasculitis induction and that they might play a role in the induction of vascular pathology.

Figure 6.

CD4+ T cells sensitized by vascular SMC express both IFNγ and IL-17, but only IFNγ expression was recalled ex vivo in CD4+ cells from vasculitic mice. A: Intracellular cytokine by flow cytometry in permeabilized cells before adoptive transfer. B: Ex vivo recall response to anti-CD3 antibody of IFNγ (left panels) and IL-17 (right panels) in lymphocytes from organs of vasculitic mice (vasculitis) compared to naïve cell transfers (control) at day 7 postadoptive transfer. Numbers in dot plots are percent IFNγ+ or IL-17+ cells out of total lung CD4+ cells. C depicts absolute numbers of CD4+ CFSE+low IFNγ+ and of CD4+ CFSE+low IL-17+ isolated per mouse lung, normalized to medium controls (two mice per group). D and E: Tim3 expression on CD4+ CFSE+ lymphocytes from lung of control and vasculitic mice. D: Numbers in histograms show frequency of CD4+ CFSE+ Tim3+ lymphocytes and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Tim3 expression on adoptively transferred cells. E: Absolute numbers recovered per mouse organ of CFSE+ CD4+ lymphocytes that express Tim3. Shown are results from one experiment (four mice per group). F–J: Immunofluorescence on frozen lung sections of vasculitic mice. Arrowheads point to co-expression of T-bet and CD4 (F), IL-17 and CD4 (G), tissue macrophages (I), and disrupted arteriole wall media layer. L, vessel lumen. Scale bar = 20 μm. Original magnification, ×400.

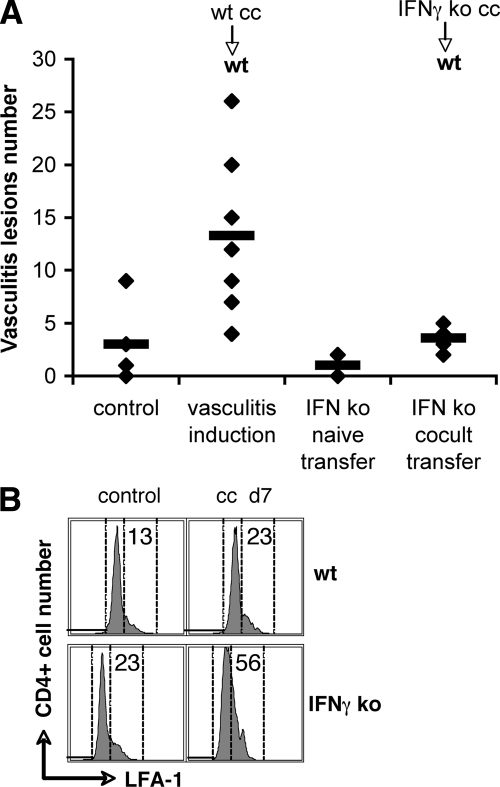

IFNγ Is Essential for Cell-Mediated Pathogenic Mechanisms in Vasculitis

To distinguish between the Th1 and Th17 contribution to vascular inflammation, we adapted the animal model of vasculitis induction to a Th1-impaired background. To this end, we used IFNγ-deficient mice on the C57BL/6J background (strain B6.129S7-Ifng/J) as lymphocyte donors for culture with syngeneic SMCs and subsequent adoptive transfer to mice on the same haplotype background. Vasculitis was efficiently induced in wt C57BL/6 mice by transfer of syngeneic lymphocytes after sensitization by culture with syngeneic vascular SMCs (Figure 7A). However, adoptive transfer of IFNγ-deficient T cells sensitized by syngeneic vascular SMCs failed to induce vasculitis in wt recipient mice (Figure 6). Failure to induce pathology was not due to lack of activation during co-culture of naïve lymphocytes with vascular SMCs, since flow cytometry showed activation of IFNγ−/− CD4+ T cells after sensitization with SMCs similarly to wt CD4+ T cells, as assessed by the expression of late activation marker CD11a/LFA-1 (Figure 7B). These results indicate that IFNγ is critically required for initiation of pathogenic mechanisms and vascular inflammation after adoptive transfer, and that IL-17 expression alone is not sufficient to trigger disease.

Figure 7.

Vasculitis efficiently induced in wt C57BL/6 mice by transfer of SMC-sensitized wt T cells, but not by transfer of sensitized IFNγ-deficient T cells. A: Vasculitis incidence scored on H&E sections of lungs of recipient mice (each diamond represents a mouse; horizontal bar is average); n = 7, P = 0.005 for wt T cell transfers; n = 7, P = 0.19 for IFNγ-deficient T cell transfers (three experiments). B: Flow cytometry of LFA-1 expression on CD4+ T cells after sensitization by 7 days co-culture with SMCs (ml d7) compared to freshly isolated spleen CD4+ cells (control).

Discussion

This study brings forward three original observations: (i) vasculitis can be induced in the absence of B cells and autoantibodies; (ii) CD4+ T cells sensitized by culture with vascular SMC are sufficient to induce vasculitis after adoptive transfer to syngeneic recipients; and (iii) IFNγ is indispensable for induction of vasculitis pathology in this model.

The first observation, that vasculitis can be induced in the absence of B cells, is noteworthy because autoantibody-mediated inflammatory reactions are thought to be the primary pathogenic mechanisms of vessel damage and local inflammation in vasculitis, through type II22,23 or type III hypersensitivity.24 Covert cell-mediated mechanisms are assumed to be active, leading to a recent profusion of reports on Th1, Th17, or regulatory T cell imbalances in vasculitis syndromes (reviewed in 25). However, direct evidence that autoreactive T cells elicit vascular pathology on their own is still elusive. In this study we showed that vasculitis could be induced in the absence of autoantibodies in B-cell deficient mice, by adoptive transfer of T cells. These results are comparable to a newly described model of experimental autoimmune anti-myeloperoxidase-associated glomerulonephritis, in which B cell-deficient mice developed severe crescentic glomerulonephritis similarly to wt mice.26 This suggests that in these two models cell-mediated autoimmunity is a major effector pathway of vascular injury. The prospect that vascular pathology can occur in the absence of B cells provides a basis for studying the development of granulomatous lesions in a number of systemic autoimmune vasculitides in which autoantibodies do not play a major pathogenic role.

Our second finding, that highly purified CD4+ T cells previously sensitized by co-culture with SMCs can induce vasculitis, suggests a role of Th cell autoreactivity in vascular pathology. Primary vasculitides are considered to be autoimmune27 based on direct evidence of maternal-fetal transfer of pathogenic autoantibodies28,29 and autoantigen identification,30 and on other indirect and circumstantial evidence.31 Vascular cells are established targets of autoimmune reactivity in vasculitis, because anti-endothelial cell antibodies and anti-vascular SMCs antibodies are common findings in a number of vasculitides. We previously reported that in this animal model, vasculitis was accompanied by the generation of anti-vascular SMC antibodies and anti-myeloperoxidase IgG2a and IgG1 autoantibodies.19 Isotype switching to IgG classes attested to a T cell-dependent (Th2) antigen-specific autoimmune response targeted against SMCs and myeloid cell autoantigens. However, in the present study, vasculitis could be induced by transfer of purified CD4+ T cells in the absence of SMC-sensitized B cells, suggesting that in addition to autoreactive Th2, other autoreactive Th cells such as Th1 and Th17 were activated during the co-culture with SMCs and mediated the pathology after adoptive transfer. Additionally, the in vivo tolerance of syngeneic vascular SMCs (injections in mice of either live SMCs- Figure 1, or of lysed SMCs, do not induce vasculitis, even in the presence of complete Freund adjuvant [CFA]—data not shown), corroborated by the limited activation of CD8+ T cells in this model, do not support the idea that vasculitis in this model might be the result of reactivity against a viral antigen expressed by the SMCs.32 While mice are tolerant of syngeneic vascular SMC self-antigens, the splenocyte–SMC co-culture likely evokes a breakdown in peripheral T cell tolerance. This may be attributed to biochemical modifications of autoantigens during cell stress or death processes33 that are replicated during the splenocyte–SMC co-culture, and that could trigger activation of autoreactive T cells which escaped negative selection and circulate in the periphery. Additional support to Th cell autoreactivity with vascular antigens in this model is brought by previously published evidence that T cell activation and proliferation are dependent on TCR–major histocompatibility complex class II interactions, are not due to superantigen stimulation (given that flow cytometry detection of TCR gene segment usage did not show the expansion nor deletion of T cells expressing a sole TCR V segment); and by oligoclonal expansion of T cells in vasculitic mice and in culture with SMCs (indicated by spectratype analysis of TCR J segments).4 Demonstrating the capacity of CD4+ T cells specific for vascular antigens to accumulate, become activated, clonally expand, and induce vasculitis, is an advancement in our understanding of early cell-mediated pathogenesis events of this disorder.

Finally, the current study brings evidence that IFNγ is critical for induction of vasculitis pathology, and IL-17 alone may not be sufficient to induce vasculitis. A disease-promoting effect of IFN-γ in autoimmunity was evidenced in other disease models, such as lupus-like nephritis,34 autoimmune disease of peripheral nervous system35 and autoimmune diabetes.36 In models of autoimmunity that use CFA for disease induction, such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis37 or collagen-induced arthritis,38,39 IFNγ or IFNγR deficiencies were associated with more severe disease when CFA was used; but then again, IFNγ reverted to a disease-promoting role in the absence of CFA,40 indicating that CFA can alter the disease-promoting effect of IFN-γ in models of autoimmunity. However, in this model of autoimmune vasculitis both IFNγ and IL-17 were produced in vitro after culture with SMCs, suggesting that both autoreactive Th1 and Th17 cells differentiated or were activated. Th1 and more recently recognized Th17 cells are important effectors in inducing the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and promoting tissue injury in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.12,13 Their presence in biopsies or the blood of some vasculitis patients suggests they both might play an important role in vasculitis pathology. Since IFNγ deficiency was shown to break self-tolerance in an arthritis model by facilitating the differentiation and expansion of pathogenic Th17 cells,41 we believed that transposing the vasculitis model on an IFNγ-deficient background would allow to study Th17-dependent pathogenic mechanisms in vasculitis. Surprisingly though, no vasculitis developed when IFNγ-deficient donors were used, suggesting that no pathogenic cells were activated during co-culture with SMC in the presence of IL-17 and absence of IFNγ. Moreover, the data imply that the sole expression of IL-17 in vasculitis is not directly indicative of a pathogenic role for Th17 cells. Recently published data support this observation. Eid et al42 have shown that, in the absence of IFNγ, IL-17 only marginally induced human vascular SMC to express pro-inflammatory mediators in cytokine arrays. Nevertheless the expressions of C5a, IL-1R antagonist, IL-6, CXCL8, CCL-5, CXCL1, and CXCL10 by SMC were dramatically amplified in the presence of both IL-17 and IFNγ.42 Similar observations on the modest role of IL-17 alone in inducing pro-inflammatory CXCL1 expression, while markedly increasing its expression when used in combination with TNFα, lead to the finding that IL-17 does not induce but stabilizes ephemeral mRNA induced by other cytokines as a way to promote pro-inflammatory gene expression.43,44 Taken together, these observations suggest that the expression of IL-17 might contribute to vascular SMC induction of a pro-inflammatory milieu in the presence of a Th1 response, but not in its absence, possibly through stabilizing the expression of mediators such as IL-6, CXCL8, and CXCL10.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates the pathogenic role that CD4+ T cell-mediated (namely Th1) mechanisms play in the induction of vascular inflammation in a murine model of vasculitis. By characterizing Th1 cells specific for vascular autoantigens as pathogenic factors in vasculitis, we validate new efforts on the depletion of selected T cell populations, such as Tim-3-expressing Th1 cells, as a possible therapeutic intervention to stop disease progression in patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Khen Macvilay for operating the LSR II system, Satoshi Kinoshita for paraffin blocks processing, and Jeffrey Harding for assistance with manuscript editing.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Michael Hart, M.D., Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Wisconsin, 3158 Medical Foundation Centennial Building, 1685 Highland Ave., Madison, WI 53705. E-mail: mnhart@wisc.edu.

Supported by National Institute of Health grant R01HL48658.

References

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:11–16. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma-Krupa W, Jeon MS, Spoerl S, Tedder TF, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Activation of arterial wall dendritic cells and breakdown of self-tolerance in giant cell arteritis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:173–183. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JW, Shimada K, Ma-Krupa W, Johnson TL, Nerem RM, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Vessel wall-embedded dendritic cells induce T-cell autoreactivity and initiate vascular inflammation. Circ Res. 2008;102:546–553. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson BJ, Baiu DC, Sandor M, Fabry Z, Hart MN. A small population of vasculitogenic T cells expands and has skewed T cell receptor usage after culture with syngeneic smooth muscle cells. J Autoimmun. 2003;20:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(02)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyand CM, Schonberger J, Oppitz U, Hunder NN, Hicok KC, Goronzy JJ. Distinct vascular lesions in giant cell arteritis share identical T cell clonotypes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:951–960. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seko Y, Takahashi N, Tada Y, Yagita H, Okumura K, Nagai R. Restricted usage of T-cell receptor Vgamma-Vdelta genes and expression of costimulatory molecules in Takayasu’s arteritis. Int J Cardiol. 2000;75 Suppl 1:S77–S83. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00194-7. discussion S85–S77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayne D. Evidence-based treatment of systemic vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:585–595. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt WH, Hagen EC, Neumann I, Nowack R, Flores-Suarez LF, van der Woude FJ. Treatment of refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis with antithymocyte globulin (ATG): an open study in 15 patients. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1440–1448. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer E, Tervaert JW, Horst G, Huitema MG, van der Giessen M, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Predominance of IgG1 and IgG4 subclasses of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA) in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis and clinically related disorders. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;83:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy NK, Chauhan SK, Nityanand S. Cytokine mRNA repertoire of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:369–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Bjornsson J, Bartley GB, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Interferon-gamma-producing T cells in giant cell vasculitis represent a minority of tissue-infiltrating cells and are located distant from the site of pathology. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1925–1933. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn MH, Noh SY, Chang W, Shin KM, Kim DS. Circulating interleukin 17 is increased in the acute stage of Kawasaki disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:364–366. doi: 10.1080/03009740410005034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Tsurikisawa N, Tsuburai T, Oshikata C, Akiyama K. Cytokine production profile of CD4+ T cells from patients with active Churg-Strauss syndrome tends toward Th17. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149 Suppl 1:61–65. doi: 10.1159/000210656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulahad WH, Stegeman CA, van der Geld YM, Doornbos-van der Meer B, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Functional defect of circulating regulatory CD4+ T cells in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis in remission. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2080–2091. doi: 10.1002/art.22692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruskova Z, Rihova Z, Mareckova H, Jancova E, Rysava R, Zavada J, Merta M, Loster T, Tesar V. Intracellular cytokine production in ANCA-associated vasculitis: low levels of interleukin-10 in remission are associated with a higher relapse rate in the long-term follow-up. Arch Med Res. 2009;40:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde B, Dolff S, Cai X, Specker C, Becker J, Totsch M, Costabel U, Durig J, Kribben A, Tervaert JW, Schmid KW, Witzke O. CD4+CD25+ T-cell populations expressing CD134 and GITR are associated with disease activity in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:161–171. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valzasina B, Guiducci C, Dislich H, Killeen N, Weinberg AD, Colombo MP. Triggering of OX40 (CD134) on CD4(+)CD25+ T cells blocks their inhibitory activity: a novel regulatory role for OX40 and its comparison with GITR. Blood. 2005;105:2845–2851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MN, Tassell SK, Sadewasser KL, Schelper RL, Moore SA. Autoimmune vasculitis resulting from in vitro immunization of lymphocytes to smooth muscle. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:448–455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiu DC, Barger B, Sandor M, Fabry Z, Hart MN. Autoantibodies to vascular smooth muscle are pathogenic for vasculitis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1851–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62494-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Strauch AR, Yoder EJ, Rubenstein PA, Hart MN. Cerebral microvascular smooth muscle in tissue culture. In Vitro. 1984;20:512–520. doi: 10.1007/BF02619625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Fueyo A, Tian J, Picarella D, Domenig C, Zheng XX, Sabatos CA, Manlongat N, Bender O, Kamradt T, Kuchroo VK, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Coyle AJ, Strom TB. Tim-3 inhibits T helper type 1-mediated auto- and alloimmune responses and promotes immunological tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister H, Ollert M, Frohlich LF, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Colby TV, Specks U, Jenne DE. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies against the murine homolog of proteinase 3 (Wegener autoantigen) are pathogenic in vivo. Blood. 2004;104:1411–1418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Heeringa P, Liu Z, Huugen D, Hu P, Maeda N, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. The role of neutrophils in the induction of glomerulonephritis by anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:39–45. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62951-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz P. Vasculitis. Austen KF, Frank MM, Atkinson JP, Cantor H, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins,; 2001:pp 560–571. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulahad WH, Stegeman CA, Kallenberg CG. Review article: the role of CD4(+) T cells in ANCA-associated systemic vasculitis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2009;14:26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth AJ, Kitching AR, Kwan RY, Odobasic D, Ooi JD, Timoshanko JR, Hickey MJ, Holdsworth SR. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and effector CD4+ cells play nonredundant roles in anti-myeloperoxidase crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1940–1949. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewins P, Tervaert JW, Savage CO, Kallenberg CG. Is Wegener’s granulomatosis an autoimmune disease? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:3–10. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal PJ, Tobin MC. Neonatal microscopic polyangiitis secondary to transfer of maternal myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody resulting in neonatal pulmonary hemorrhage and renal involvement. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93:398–401. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlieben DJ, Korbet SM, Kimura RE, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Pulmonary-renal syndrome in a newborn with placental transmission of ANCAs. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:758–761. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajema IM, Bruijn JA. What stuff is this! A historical perspective on fibrinoid necrosis. J Pathol. 2000;191:235–238. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(0000)9999:9999<N/A::AID-PATH610>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specks U. Are animal models of vasculitis suitable tools? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:11–19. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Canto AJ, Virgin HW., 4th Animal models of infection-mediated vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:17–23. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamachi M, Le TM, Kim SJ, Geiger ME, Anderson P, Utz PJ. Human autoimmune sera as molecular probes for the identification of an autoantigen kinase signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1213–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob CO, van der Meide PH, McDevitt HO. In vivo treatment of (NZB X NZW)F1 lupus-like nephritis with monoclonal antibody to gamma interferon. J Exp Med. 1987;166:798–803. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.3.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung HP, Schafer B, van der Meide PH, Fierz W, Heininger K, Toyka KV. The role of interferon-gamma in the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune disease of the peripheral nervous system. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:247–257. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debray-Sachs M, Carnaud C, Boitard C, Cohen H, Gresser I, Bedossa P, Bach JF. Prevention of diabetes in NOD mice treated with antibody to murine IFN gamma. J Autoimmun. 1991;4:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(91)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willenborg DO, Fordham S, Bernard CC, Cowden WB, Ramshaw IA. IFN-gamma plays a critical down-regulatory role in the induction and effector phase of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 1996;157:3223–3227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire K, Heremans H, Vandeputte M, Huang S, Billiau A, Matthys P. Accelerated collagen-induced arthritis in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5507–5513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury-Schwartz B, Chiocchia G, Bessis N, Abehsira-Amar O, Batteux F, Muller S, Huang S, Boissier MC, Fournier C. High susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis in mice lacking IFN-gamma receptors. J Immunol. 1997;158:5501–5506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthys P, Vermeire K, Mitera T, Heremans H, Huang S, Schols D, De Wolf-Peeters C, Billiau A. Enhanced autoimmune arthritis in IFN-gamma receptor-deficient mice is conditioned by mycobacteria in Freund’s adjuvant and by increased expansion of Mac-1+ myeloid cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:3503–3510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K, Hashimoto M, Yoshitomi H, Tanaka S, Nomura T, Yamaguchi T, Iwakura Y, Sakaguchi N, Sakaguchi S. T cell self-reactivity forms a cytokine milieu for spontaneous development of IL-17+ Th cells that cause autoimmune arthritis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:41–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J, Lo SF, Ranjbaran H, Gallo A, Sokol SI, Pfau S, Pober JS, Tellides G. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma are produced concomitantly by human coronary artery-infiltrating T cells and act synergistically on vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2009;119:1424–1432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartupee J, Liu C, Novotny M, Li X, Hamilton T. IL-17 enhances chemokine gene expression through mRNA stabilization. J Immunol. 2007;179:4135–4141. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lotvall J, Sjostrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Linden A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol. 1999;162:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]