Abstract

The Cancer Nutrition Rehabilitation (cnr) program at the McGill University Health Centre is an interdisciplinary 8-week treatment program offering patients information, education, treatment, and support in areas such as diet, exercise, and rehabilitation, plus resources to address their psychosocial needs. The program social worker helps the patient and the patient’s family to cope with the illness, to problem-solve, and to obtain needed resources. Here, we present a description of these patients—demographics, medical diagnoses, and psychosocial needs as assessed by the Person-in-Environment standardized instrument—derived from the social-work files of the 75 patients referred to social work in the period February 2007–December 2008. The reason most frequently reported for referral to social work was assistance with psychosocial problems. For 41.3% of the sample, these problems were assessed as high severity, and almost half the patients in the sample (47.8%) were assessed as having inadequate coping ability. Patient age was the most important demographic variable. Although seniors (63–94 years of age) were the least likely to have high-severity psychosocial problems, they were the most likely to have inadequate coping ability. That finding suggests that the cnr social worker, in addition to dealing with the instrumental, practical needs of cancer patients, is in a unique position to respond to their emotional difficulties in coping with their illness, and that health care professionals need to pay particular attention to the coping ability of elderly patients.

Keywords: Cancer patients, psychosocial needs, social worker, cancer rehabilitation

1. INTRODUCTION

Canadian Cancer Society statistics estimated that approximately 171,000 new cases of cancer would be diagnosed in 2009 1. Psychosocial issues such as anxiety, family relationships, changes in lifestyle, and fear about recurrence and death can be experienced by many cancer patients 2.

Numerous studies have examined the psychosocial changes and difficulties that can occur with a cancer diagnosis. In their cross-sectional study of adult patients in a tertiary hospital setting, Carlson et al. 3 noted that 37% of patients surveyed were assessed as being in serious psychological distress, particularly in the areas of depression and anxiety. Such distress was more evident among younger patients. That finding contrasts with a retrospective data analysis of the degree of psychological distress among cancer patients conducted by Sellick and Edwardson 4, who found that, compared with middle-aged and younger patients, older patients (older than 70 years) described more symptoms of depression, but fewer symptoms of anxiety.

In a cross-sectional survey of cancer patients, Soothill et al. 5 found that some patients identified significant unmet needs in the areas of emotional difficulties, social identity, and managing their daily activities. The ability of patients to express their feelings about cancer openly with a caregiver or health professional was also cited as a significant unmet need.

For many patients, important areas of need include financial stress; information on their illness, medications, and available services and resources; and adequate supports from family, friends, and health care professionals 5. Recent studies examining the financial burden associated with a cancer diagnosis found that patients have significant illness-related expenses and work loss despite government programs designed to help in those situations 6. The financial stress experienced by some patients has been found to relate to depression, especially among low-income patients, but also among those in the middle-income bracket. Financial stress, coupled with emotional distress factors such as anxiety and depression related to a cancer diagnosis, can seriously hamper a patient’s quality of life 7.

1.1. The Role of Social Work

Social workers are trained to assess the psychosocial needs of cancer patients and their families by examining the patient’s social, familial, cultural, and economic environment. They help to identify factors that affect the patient’s wellbeing.

Studies that focus specifically on the efficacy of social work interventions with cancer patients are relatively sparse. Literature on how evidence-based psychosocial interventions can better the health and overall wellbeing of cancer patients is also minimal 8. Furthermore, few methodologically thorough studies have been conducted on how psychosocial interventions in general affect patient survival 9.

One study, however, found that access to social work services can improve quality of life for cancer patients. In their study of the social work element within an interdisciplinary interventions, and of the influence of social work on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer, Miller et al. 10 showed that social work intervention in the areas of support and information about community, financial, and legal resources resulted in notable improvements in the patients’ quality of life. Sufficient attention paid to quality of life is especially important for people who have few psychosocial resources.

1.2. Cancer Nutrition Rehabilitation Program

The Cancer Nutrition Rehabilitation (cnr) program based at the McGill University Health Centre (muhc) is a comprehensive 8-week treatment program offering patients information, education, treatment, and support in areas such as diet, exercise, and rehabilitation, plus resources to address their psychosocial needs.

Patients are referred to the program by their primary physician or oncologist when they exhibit any one or combination of challenging symptoms, weight changes, de-conditioning, or psychosocial distress related to their illness. The program pivot nurse makes the first contact with patients and conducts an initial screening. If a patient shows interest and is motivated to participate in the program, an evaluation interview is arranged. At that interview, the patient can meet members of the team and learn more about the program. Several evaluation forms are then completed by the patient, who answers questions about symptoms, distress level, nutrition, and physical ability to carry out activities of daily living (adls). The decision to accept a patient into the program is made by the program team.

An interdisciplinary team approach is used with all patients accepted, and weekly team meetings are held to discuss a treatment plan tailored to the specific needs of the individual patient. Many patients participating in the program may be followed by more than one allied health professional. All patients are followed by the pivot nurse and a medical oncologist. The program social worker is an integral member of the interdisciplinary team, which also includes a physiotherapist, a nutritionist, a psychologist, an occupational therapist, a nurse, and a physician.

Based on the patient’s goals and needs, referrals are made to the program social worker for assessment and follow-up. Social work interventions include supportive counselling, caregiver support, information on financial and transportation resources, referrals for community home support services, and co-facilitation of patient and caregiver support groups.

The social worker position in the cnr program was created 1 year after the program’s inception, and the incumbent initially worked 1 day each week. In September 2008, the time was increased to 3 days weekly. Early intervention on the part of the social worker can alleviate some of the psychosocial burdens faced by cancer patients. Further understanding is needed about the psychosocial factors that affect the ability of patients to cope with their illness.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patient Users of Social Services: Data Review

We conducted a retrospective data review of the social service files of all 75 patients referred to the cnr program social worker from February 21, 2007, to December 31, 2008. Those 75 patients represent 58.6% of the 128 patients accepted into the cnr program during that period. Demographic and medical information (diagnosis, reason for referral, age, sex, marital status, living arrangement, source of income) and information on psychosocial needs (nature and severity of identified problems, level of coping ability) were extracted from the files. The hope was that this information could provide a foundation for designing the most effective possible program for patients.

The assessment of patient psychosocial needs was based on the Person-in-Environment (pie) system, a classification system developed for social workers to describe and code social functioning problems according to social role, environment, and mental and physical health problems 11. This information provides a comprehensive, holistic view of the patient’s problems. The pie system was tested by social workers across the United States from the various regions of the National Association of Social Workers (nasw), and nasw eventually formally adopted the system. The pie system is the standard intake assessment measure used by Social Service, Adult Sites, at the muhc.

All the variables used were categorical. Data analysis involved a description of the sample (frequency distributions) and examination of possible relationships between psychosocial needs and demographic and medical variables (cross-tabulations, plus chi-square tests for nominal variables and Mann–Whitney analysis for ordinal variables).

Following the procedure suggested by Siegel and Castellan 12, low-frequency pie categories were combined. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package (version 15: SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

3. RESULTS

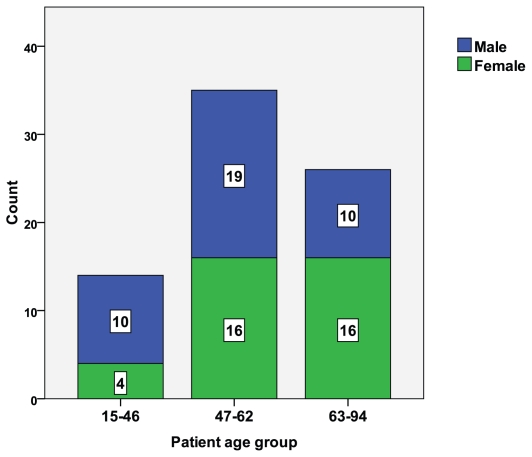

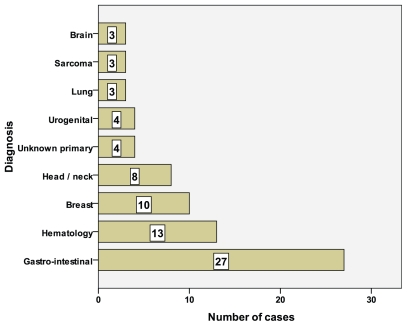

Table I summarizes the demographic characteristics of the patients in the study (n = 75). Just over half were men, and just over one third were in the 65–94 age group; the men tended to be younger (Figure 1), a relationship that was statistically significant (Mann–Whitney U = 528, p < 0.05). Very few of the patients were in the workforce. Almost two thirds (62.7%) were either married or in common-law relationships, and almost 70% were living with either a spouse or their family. The most frequently reported reason for referral was a need for assistance with psychosocial problems. Figure 2 shows the medical diagnoses for the patient cohort; gastrointestinal cancers were the most frequently diagnosed conditions.

TABLE I.

Description of the patient sample

| Variable | Value |

|

|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 39 | 52.0 |

| Female | 36 | 48.0 |

| Age | ||

| 15–46 Years | 14 | 18.7 |

| 47–62 Years | 35 | 46.7 |

| 63–94 Years | 26 | 34.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 9 | 12.0 |

| Married/common-law | 47 | 62.7 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 19 | 25.3 |

| Living arrangements | ||

| Alone | 20 | 26.7 |

| Couple | 29 | 38.7 |

| Family | 23 | 30.7 |

| Other | 3 | 4.0 |

| Source of incomea | ||

| Employment | 3 | 4.0 |

| ei benefits | 15 | 20.0 |

| Old age security | 20 | 26/7 |

| Welfare/other benefits | 12 | 16.0 |

| Other income | 44 | 58.7 |

| Identified problemsa | ||

| Psychosocial | 47 | 62.7 |

| Financial | 21 | 28.0 |

| Transport | 32 | 42.7 |

| Family or work issues | 25 | 33.3 |

| TOTAL | 75 | 100 |

Multiple responses possible.

ei = employment insurance.

FIGURE 1.

The patient sample: proportion of men and women by age group.

FIGURE 2.

The patient sample: cancer types diagnosed.

3.1. Severity of Psychosocial Problems

The only pie severity categories reported by social workers for these patients were “low” (n = 1), “moderate” (n = 43), and “high” (n = 31). No patient in the sample was rated “no problem,” “very high,” or “catastrophic.” For analysis, the “low severity” case was combined with the moderate cases.

Table II shows cross-tabulations of severity category by patient characteristics; none of the relationships were statistically significant. The variable that came closest to significance was patient age: only 34.6% of the oldest age group (63–94 years), as compared with 57.1% of the youngest group (15–46 years), were in the “high severity” category. The income source variable also provided some additional evidence of the effect of age. The category with the lowest percentage of “high severity” cases was “old age pension” (oap).

TABLE II.

Psychosocial severity by patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Severity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate |

High |

|||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 24 | 61.5 | 15 | 38.5 |

| Female | 20 | 55.6 | 16 | 44.4 |

| Age | ||||

| 15–46 Years | 6 | 42.9 | 8 | 57.1 |

| 47–62 Years | 21 | 60.0 | 14 | 40.0 |

| 63–94 Years | 17 | 65.4 | 9 | 34.6 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 6 | 66.7 | 3 | 33.3 |

| Married/common-law | 25 | 53.2 | 22 | 46.8 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 13 | 68.4 | 6 | 31.6 |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Alone | 12 | 60.0 | 8 | 40.0 |

| Couple | 16 | 55.2 | 13 | 44.8 |

| Family | 13 | 56.5 | 10 | 43.5 |

| Other | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Source of incomea | ||||

| Employment | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 33.3 |

| ei benefits | 9 | 60.0 | 6 | 40.0 |

| Old age security | 14 | 70.0 | 6 | 30.0 |

| Welfare/other benefits | 7 | 58.3 | 5 | 41.7 |

| Other income | 24 | 54.5 | 20 | 45.5 |

| Identified problemsa | ||||

| Psychosocial | 31 | 66.0 | 16 | 34.0 |

| Financial | 10 | 47.6 | 11 | 52.4 |

| Transport | 17 | 53.1 | 15 | 46.9 |

| Family or work issues | 15 | 60.0 | 10 | 40.0 |

| TOTAL | 44 | 58.7 | 31 | 41.3 |

Multiple responses possible.

ei = employment insurance.

3.2. Patients’ Coping Ability

The only coping categories reported for the sample were “adequate” (n = 36), “somewhat inadequate” (n = 30), and “inadequate” (n = 3); values for 6 patients were missing. No patients in the sample received a rating of “no coping skills,” “above average,” or “outstanding.” For analysis, the “inadequate” and “somewhat inadequate” categories were combined.

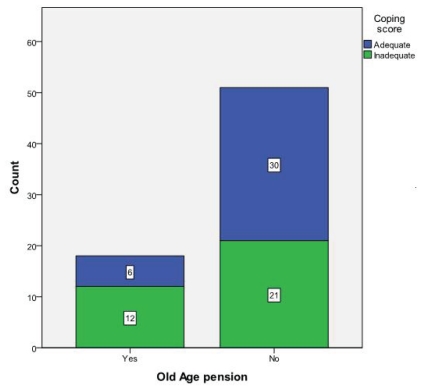

Table III shows cross-tabulations of coping ability by patient characteristics. Again, the strongest relationship was with patient age: 65.2% of seniors, as compared with only 42.9% and 37.5% of the two younger groups, were in the “inadequate coping” category (Mann–Whitney U = 468, p = 0.10, not quite statistically significant). Again, the income source variable provided additional evidence of the effect of age. The highest percentage of patients with inadequate coping ability was found in the oap category. A cross-tabulation of coping category by oap (yes/no) was just short of significance (Fisher exact test, p = 0.056). That relationship is shown graphically in Figure 3.

TABLE III.

Coping ability by patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Severity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate |

Inadequate |

|||

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 19 | 54.3 | 16 | 45.7 |

| Female | 17 | 50.0 | 17 | 50.0 |

| Age | ||||

| 15–46 Years | 8 | 57.1 | 6 | 42.9 |

| 47–62 Years | 20 | 62.5 | 12 | 37.5 |

| 63–94 Years | 8 | 34.8 | 15 | 65.2 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 4 | 44.4 | 5 | 55.6 |

| Married/common-law | 24 | 58.5 | 17 | 41.5 |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 8 | 42.1 | 11 | 57.9 |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Alone | 9 | 45.0 | 11 | 55.0 |

| Couple | 13 | 54.2 | 11 | 45.8 |

| Family | 13 | 59.1 | 9 | 40.9 |

| Other | 1 | 33.3 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Source of incomea | ||||

| Employment | 2 | 67.7 | 1 | 33.3 |

| ei benefits | 8 | 57.1 | 6 | 42.9 |

| Old age security | 6 | 33.3 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Welfare/other benefits | 9 | 81.8 | 2 | 18.2 |

| Other income | 17 | 42.5 | 23 | 57.5 |

| Identified problemsa | ||||

| Psychosocial | 22 | 50.0 | 22 | 50.0 |

| Financial | 9 | 47.4 | 10 | 52.6 |

| Transport | 14 | 48.3 | 15 | 51.7 |

| Family or work issues | 13 | 56.5 | 10 | 43.5 |

| TOTAL | 36 | 52.2 | 33 | 47.8 |

Multiple responses possible.

Data unavailable for 6 patients.

ei = employment insurance.

FIGURE 3.

The patient sample: proportion coping adequately or inadequately by income source (receiving or not receiving old age pension income).

It is interesting to note that the effect of patient age on coping ability (worse for older people) was a mirror image of the effect on psychological severity (better for older people).

Some additional noteworthy findings from the social work files are that most patients (85.3%) were identified as being independent with their adls. On the other hand, 55% of patients needed some assistance with their instrumental needs, such as transportation to medical appointments, finances, buying groceries, and housecleaning, among others. All patients with financial and transportation problems indicated that these issues were of moderate to high severity.

3.3. Case Example

Mrs. G, age 70 years, diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, has a poor prognosis, a situation of which she is aware. Mrs. G is not undergoing any active treatment at this time. She is widowed, has two adult children with whom she maintains close contact, and receives only the basic government oap. She has financial constraints, and she struggles to meet not only her living expenses, but also the costs of some medications not covered by public health insurance. With the progression of her disease, her ability to carry out her adls has declined and her mobility has become significantly reduced. She was once an active member of her community, taking part in church activities and in a weekly bowling league, but she now uses a cane for walking, and she requires assistance with bathing, cooking, cleaning, and meal preparation. Although Mrs. G has a loving family who are trying to be supportive, she expresses significant sadness and disillusionment over the implications of her illness and its impact on her daily life. She expresses a willingness to work on improving her situation so that she can participate once again in her activities.

Mrs. G’s experience is one faced by many cancer patients who had looked forward to the future and now find themselves dealing with an unexpected life-threatening illness. These patients are good candidates for the cnr program, because they are motivated to learn how to improve their quality of life through better nutrition and exercise, thus increasing their energy level and building up overall physical strength.

Practical assistance with transportation to medical appointments and community activities would be of benefit for Mrs. G, as would supportive counselling from the social worker, who can help her cope with the many challenges she faces in living with cancer.

4. DISCUSSION

Many of the patients in this sample face challenges in daily living, as described in the case example. They require some assistance with instrumental needs, such as paying bills, buying groceries, housekeeping, and travelling to and from medical appointments. However, the most striking finding in this study is the prominent role played by psychosocial problems. The most frequently reported reason for referral to the social worker was assistance with psychosocial problems. For 41.3% of the sample, these problems were assessed as high severity, and almost half the sample (47.8%) was assessed as having inadequate coping ability.

In this context, patient age was the most important demographic variable. It is interesting to note that the age category that showed the lowest percentage of high severity psychosocial problems was the oldest (63–94 years), and that the income source category with the lowest percentage of high severity psychosocial problems was oap (received by those 65 years and older). This finding accords with previous research suggesting that elderly cancer patients often show fewer symptoms of anxiety than do middle-aged or younger patients 4.

On the other hand, older patients were the most likely to have inadequate coping ability. The 63–94 age category and the oap income source category showed the most difficulty in coping with the effects of their illness while carrying out everyday activities. The decreased physical ability and personal autonomy that often accompany advanced age may be expected to have a negative effect on how well a patient is able to cope with illness. Our findings on coping and severity of psychosocial problems among the oldest age group (63–94 years) are new to the relatively sparse body of literature, and merit further study.

4.1. Study Limitations

Our findings are based on a relatively small patient sample in a specific hospital setting; the generalizability to a larger population is limited. The most interesting finding—the high incidence of psychosocial problems—was based on the program social worker’s assessments using the pie system. Every effort is made to train workers in the use of this system, but guaranteeing that assessments of this kind are consistently reliable and valid is always difficult.

These data are purely descriptive. A useful next step would be to undertake an evaluation to assess the effectiveness of social work interventions for patients in the cnr program. Such a study could be conducted using before and after measures of patient attitudes and functioning. Randomizing patients to social work and to control groups would present both practical and ethical problems, but a waiting-list comparison group might be an option.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This overview of the psychosocial needs of patient participants in the cnr program may help to increase awareness among health care professionals of the needs of cancer patients, and may help to identify psychosocial factors that affect the ability of these patients to cope with their illness.

The social worker in the cnr program is in a unique position both to respond to the practical, instrumental needs of patients and to address issues related to the emotional impact of the illness. The social worker can bring clinical knowledge of the patient’s social, emotional, behavioural, and environmental context to the interdisciplinary health care team.

Given the finding in this study that elderly patients appear to have the most difficulty coping with their illness, advanced age is a factor that should be given particular attention by the social worker and by all health care professionals within the cnr team.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the cnr program, muhc, for funding this study. Thanks also go to Vanessa Sakadakis, msw, Clinical Coordinator, Social Service, Adult Sites, muhc, for her helpful comments and support.

7. REFERENCES

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2009. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaza C, Sellick SM, Hillier LM. Coping with cancer: what do patients do? J Psychosoc Oncol. 2005;23:55–73. doi: 10.1300/J077v23n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High level of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellick SM, Edwardson AD. Screening new cancer patients for psychological distress using the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychooncology. 2007;16:534–42. doi: 10.1002/pon.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soothill K, Morris SM, Harman J, Francis B, Thomas C, McIllmurray MB. The significant unmet needs of cancer patients: probing psychosocial concerns. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:597–605. doi: 10.1007/s005200100278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo CJ, Fitch M, Deber RB, Williams AP. Financial and family burden associated with cancer treatment in Ontario, Canada. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1077–85. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wampler S. The high cost of cancer and stress. USC News. 2008 Oct;24 [Available online at: uscnews.usc.edu/health/the_high_cost_of_cancer_and_stress.html; cited October 2, 2010] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maramaldi P, Dungan S, Poorvu N. Cancer treatments. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2008;50:45–77. doi: 10.1080/01634370802137793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilliquist P, Abramson J. Separating the apples and oranges in the fruit cocktail: the mixed results of psychosocial interventions on cancer survival. Soc Work Health Care. 2002;36:65–79. doi: 10.1300/J010v36n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller JJ, Frost MH, Rummans TA, et al. Role of the medical social worker in improving quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:105–19. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karls JM, Wandrei KE. Person-in-Environment System: The PIE Classification System for Social Functioning Problems. Washington, DC: nasw Press; 1994. pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel S, Castellan NJ. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioural sciences. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1988. [Google Scholar]