Abstract

The pregnane X receptor (PXR) and the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) are two closely related and liver-enriched nuclear hormone receptors originally defined as xenobiotic receptors. PXR and CAR regulate the transcription of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters, which are essential in protecting our bodies from the accumulation of harmful chemicals. An increasing body of evidence suggests that PXR and CAR also have an endobiotic function that impacts energy homeostasis through the regulation of glucose and lipids metabolism. Of note and in contrast, disruptions of energy homeostasis, such as those observed in obesity and diabetes, also have a major impact on drug metabolism. This review will focus on recent progress in our understanding of the integral role of PXR and CAR in drug metabolism and energy homeostasis.

Pregnane X Receptor and Constitutive Androstane Receptor As Master Regulators of Drug Metabolism and Drug Transporter

Over the long period of evolution, every organism has developed a complex defense system to prevent the accumulation of toxic xenobiotics and endogenous metabolites. Although many of the water-soluble chemicals are readily eliminated by transporter proteins, lipophilic compounds often require biotransformation to become more water-soluble before being excreted. The enzymes responsible for biotransformation include Phase I and Phase II enzymes. The cytochrome P450 (P450) enzymes belong to a superfamily of heme-containing Phase I enzymes that catalyze monooxygenase reactions of lipophilic compounds facilitated by the reducing power of the NADPH P450 oxidoreductase. Phase II enzymes catalyze the conjugation of water-soluble groups to xeno- and endobiotics. Conjugation reactions include glucuronidation, sulfation, methylation, and N-acetylation. In many cases, biotransformation leads to metabolic inactivation of chemicals. However, biotransformation may also activate the so-called prodrugs to pharmacologically active products or even to toxic metabolites (Handschin and Meyer, 2003; Pascussi et al., 2008).

Most drug-metabolizing enzymes are inducible in response to xenobiotics, which represent an adaptive response of our bodies to chemical insults. The molecular basis for this inducible defense system remained largely unknown until 1998, when pregnane X receptor [(PXR) alternatively termed steroid and xenobiotic receptor, or SXR, in humans] was discovered (Blumberg et al., 1998; Kliewer et al., 1998). PXR is expressed predominantly in the liver and intestine, and it is activated by a wide variety of natural and synthetic compounds. Upon activation, PXR forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor and activates the transcription of drug-metabolizing enzyme and transporter genes. Examples of PXR target genes include Phase I CYP3As and CYP2Cs, Phase II UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), and sulfotransferases (SULTs), and drug transporters MDR1 and MRP2. PXR has since been established as a xenosensor and master regulator of xenobiotic responses. The essential role of PXR in xenobiotic regulation and in dictating the species specificity of xenobiotic responses was confirmed through the creation and characterization of PXR null mice (Xie et al., 2000; Staudinger et al., 2001) as well as humanized PXR transgenic mice (Xie et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2007).

The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) is a sister xenobiotic receptor of PXR. Purified first from hepatocytes as a protein bound to the phenobarbital responsive element in the CYP2B gene promoter, CAR was subsequently shown to bind to the CYP2B gene promoter as a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor. In general, it is believed that endogenous CAR resides in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Upon exposure to its agonist phenobarbital (PB) or 1,4-Bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene (TCPOBOP), CAR translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and triggers the transcription of its target genes. Transfected CAR exhibited a high basal activity and was once termed a “constitutively active receptor.” The name of constitutive androstane receptor was conceived due to the binding and inhibition of CAR activity by androstanes (Forman et al., 1998). CAR null mice showed a lack of induction of Cyp2b10 and many other Phase I and Phase II enzymes and drug transporters by TCPOBOP and PB in the liver and small intestine (Wei et al., 2000).

Drug Metabolism Can Be Affected by Energy Metabolism

Drug metabolism can be affected by various pathophysiological factors, including diabetes and liver diseases that may affect the expression or activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Nuclear receptors, including the xenobiotic receptors PXR and CAR and sterol sensor liver X receptor (LXR), may function as the links between drug metabolism and energy metabolism.

P450 enzyme down-regulation has been well documented in animal models of obesity, steatosis, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (Leclercq et al., 1998; Su et al., 1999). Down-regulation of constitutive P450 expression in rat liver was proportional to the extent of hepatic lipid accumulation. Moreover, the capacity of drug metabolism was reported to be impaired in human patients with obesity, hepatic steatosis, and NASH (Fiatarone et al., 1991; Blouin and Warren, 1999; Cheymol, 2000). Liver lipid accumulation, especially in the early stage of steatosis, can significantly down-regulate several important P450s (Zhang et al., 2007), which is consistent with the decreased P450 expression in liver microsomes derived from patients with steatosis and NASH (Donato et al., 2006, 2007; Fisher et al., 2009). A recent report showed that the polyunsaturated fatty acids can down-regulate PB-induced CYP2B expression in a CAR-dependent manner in rat primary hepatocytes (Finn et al., 2009), which was consistent with an earlier report that polyunsaturated fatty acids can attenuate PB-induced nuclear accumulation of CAR (Li et al., 2007). Because hepatic steatosis often leads to increased free fatty acid levels, the inhibitory effect of free fatty acids on CAR provides a plausible explanation for the negative effect of steatosis on drug metabolism. Hepatic steatosis is often associated with increased lipogenesis, in which the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) is a key lipogenic transcription factor. It has been reported that SREBP-1 inhibited the transcriptional activities of PXR and CAR by functioning as a non-DNA binding inhibitor and blocking the interaction of PXR and CAR with nuclear receptor cofactors (Roth et al., 2008a).

The effect of hepatic steatosis on drug metabolism can also be mediated by the lipogenic nuclear receptor LXR through the cross-talk between LXR and CAR. LXRs, both the α and β isoforms, were defined as sterol sensors. In rodents, LXR activation increases hepatic cholesterol catabolism and formation of bile acids by inducing cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (Cyp7a1) (Peet et al., 1998). LXRs were later found to be an important regulator of SREBP-1c and lipogenesis (Repa et al., 2000). It has been reported that LXR-deficient mice fed with a high-cholesterol diet showed significantly higher induction of Cyp2b10 mRNA level upon PB treatment compared with wild-type mice, suggesting that LXR may repress PB-mediated CAR activation and Cyp2b10 induction in vivo (Gnerre et al., 2005). Our laboratory recently showed that LXRα and CAR are mutually suppressive and functionally related in vivo. In particular, loss of CAR increased the expression of lipogenic LXR target genes, leading to increased hepatic triglyceride accumulation; whereas activation of CAR inhibited the expression of LXR target genes and LXR ligand-induced lipogenesis. In contrast, a combined loss of LXR α and β increased the basal expression of xenobiotic CAR target genes; whereas activation of LXR inhibited the expression of CAR target genes and sensitized mice to xenobiotic toxicants. The mutual suppression between LXRα and CAR was also observed in cell culture and reporter gene assays (Zhai et al., 2010).

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) can also mediate the effect of energy metabolism on drug metabolism. As an important energy sensor, AMPK is activated in response to stresses, such as starvation, exercise, and hypoxia, which deplete cellular ATP supplies. Upon activation, AMPK increases energy production such as lipid oxidation, whereas it decreases energy-consuming processes such as gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis, to restore energy balance (Long and Zierath, 2006). Recent reports suggest that activation of AMPK is essential for PB induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes in mouse and human livers (Rencurel et al., 2005, 2006; Shindo et al., 2007). The induction of Cyp2b10 by PB in primary mouse hepatocytes was associated with an increased AMPK activity, and the treatment of AMPK agonist 5-amino-1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1H-imidazole-4-carboxamide (AICAR) triggered the nuclear accumulation of CAR in mouse livers (Shindo et al., 2007). In primary human hepatocytes, treatment with AICAR or metformin, another AMPK agonist, alone can induce CYP2B6 and/or CYP3A4 expression as efficient as PB, whereas overexpression of the dominant-negative mutant AMPKα1 or use of AMPK inhibitor completely blocked the PB induction of CYP2B6 and CYP3A4 (Rencurel et al., 2006). The essential role of AMPK in the induction of Cyp2b10 was further demonstrated in AMPKα1/α2 liver-specific knockout mice, in which the PB and AICAR induction of Cyp2b10 was blunted (Rencurel et al., 2006). Note that liver tissue from AMPKα1/α2 liver-specific knockout mice had markedly increased basal mRNA expression of Cyp210/3a11, which were not observed in isolated primary mouse hepatocytes. In an independent report, AICAR was shown to prevent the nuclear translocation of CAR in isolated primary rat hepatocytes (Kanno et al., 2010). It is unclear whether the discrepencies between the Shindo et al. (2007) and Kanno et al. (2010) studies were due to the differences in animal species or experimental conditions. The link between PB treatment and AMPK activation remains to be firmly established. It was proposed that PB may alter mitochondrial function and trigger the generation of reactive oxygen species, which subsequently activate LKB1 kinase and AMPK phosphorylation (Blättler et al., 2007). The expression of CAR and its target genes has been reported to be regulated by the circadian clock-controlled PAR-domain basic leucine zipper (PAR bZip) family of transcription factors. Mice deficient of three PAR bZip proteins were hypersensitive to xenobiotic compounds, and the deficiency in detoxification may contribute to their early aging (Gachon et al., 2006). AMPK can also regulate the circadian clock by phosphorylating and destabilizing the clock component cryptochrome 1 (Lamia et al., 2009). Together, these reports suggest the connections between molecular clocks, energy metabolism, and nuclear receptor signaling pathways.

Diabetes, a major manifestation of the metabolic syndrome, also has an impact on drug metabolism. Drug clearance was significantly increased in untreated patients of type 1 diabetes, which can be reversed by insulin treatment (Zysset and Wietholtz, 1988; Goldstein et al., 1990). This result was consistent with the observation in a streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic mouse model, in which the mice exhibited an increased Cyp2b10 basal expression that can be corrected by insulin treatment (Sakuma et al., 2001). The increased Cyp2b expression in type 1 diabetic mice seemed to be CAR-dependent and was associated with increased activities of peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor-γ-coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) and AMPK (Dong et al., 2009a). The increased expression of Cyp2b in type 1 diabetes is reminiscent of starvation conditions during which the insulin level is decreased, and the expression of both Cyp2b10 and CAR is induced (Maglich et al., 2004). Consistent with the observations in type 1 diabetes, insulin deprivation enhanced both dexamethasone- and β-naphthoflavone-induced expression of Cyp3a and Cyp1a in rat primary hepatocytes (Sidhu and Omiecinski, 1999). In contrast, the expression of Cyp2b and 2e was suppressed by insulin in rat hepatoma cells (De Waziers et al., 1995). The molecular mechanism for the interaction between the insulin pathway and PXR/CAR activity was suggested by a recent study showing that Forkhead box O1 protein (FOXO1), a member of the insulin-sensitive transcription factor family, can interact with and function as a coactivator to CAR- and PXR-mediated transcription (Kodama et al., 2004). It was believed that in conditions of insulin deficiency, such as starvation and type 1 diabetes, FOXO1 translocates into the nucleus, becomes activated, and increases the transcriptional activity of CAR and PXR.

Energy Metabolism Can Be Affected by Drug Metabolism and Xenobiotic Receptors PXR and CAR

Effects of P450s and PXR/CAR on Hepatic Lipid Metabolism.

P450 enzymes are known to be involved in the biotransformation of both xenobiotics, such as drugs, as well as endobiotics, such as cholesterol, steroid hormone, bile acids, and prostanoids. Although the role of P450s in drug metabolism has been well recognized and extensively studied, the endobiotic functions of P450s and to what extent they will affect systemic or tissue-specific homeostasis are less understood. Because all P450s receive electrons from a single donor, cytochrome P450 reductase [(CPR) NADPH:ferrihemoprotein reductase) (Smith et al., 1994], deletion of CPR will in principle inactivate all P450s. Mouse models with liver-specific deletion of CPR were generated by two independent groups (Gu et al., 2003; Henderson et al., 2003). Liver CRP null mice, in which the Cre expression was under the control of the albumin promoter, showed dramatically decreased liver microsomal P450 and heme oxygenase activities as expected (Pass et al., 2005). We were surprised to find that the liver of CPR null mice exhibited hepatomegaly and massive hepatic steatosis by two months of age, accompanied by severely reduced circulating cholesterol and triglyceride levels. These results have clearly implicated P450 activity in hepatic lipid homeostasis. Given the fact that the liver CPR null mice have their CPR gene deletion occur neonatally, as controlled by the albumin promoter, a subsequent study was designed to investigate the effect of P450 inactivation in adult mice by using a conditional knockout strategy. The conditional knockout of CRP was achieved by crossing the CRP floxed mice with the CYP1A1-Cre transgenic mice, in which the expression of Cre recombinase is controlled by the rat CYP1A1 gene promoter. The CYP1A1-Cre transgene has a low basal expression, but its expression can be markedly induced by a pharmacological administration of 3-methlycholanthrene, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, leading to a time-dependent and hepatic-specific deletion of CRP (Finn et al., 2007). Associated with the time-dependent reduction of CPR expression in the liver after the treatment of 3-methlycholanthrene in adult mice, these animals developed fatty liver and had reduced nonfasting plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels. The hepatic steatosis is mainly accounted by the accumulation of triglycerides. The source of accumulated triglycerides was believed to be dietary fatty acids, because a fat-deficient diet can reverse the steatotic phenotype (Finn et al., 2009).

The xenobiotic receptor CAR also plays an important role in hepatic lipid homeostasis. Activation of CAR by its agonist TCPOBOP has been reported to inhibit the expression of hepatic lipogenic genes and alleviate hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet fed mice and ob/ob mice (Dong et al., 2009b; Gao et al., 2009). Several possible but not mutually exclusive molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain the inhibitory effect of CAR on lipogenesis. In one study, it was suggested that activation of CAR or PXR reduced the level of SREBP-1 by inducing Insig-1, a protein blocking the proteolytic activation of SREBPs (Roth et al., 2008b). Our own study suggested that CAR may inhibit lipogenesis by inhibiting the LXR agonist responsive recruitment of LXRα to the Srebp-1c gene promoter (Zhai et al., 2010).

In contrast to the inhibitory effect of CAR on lipogenesis, activation of PXR seemed to promote lipogenesis. Transgenic mice expressing a constitutively activated PXR showed hepatomegaly and marked hepatic steatosis, and treatment of mice with a PXR agonist elicited a similar effect. PXR-induced lipogenesis was independent of the activation of SREBP-1c and was associated with the induction of fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2 (PPARγ2), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (Zhou et al., 2006). Further promoter analyses showed that both CD36 and PPARγ2 are direct transcriptional targets of PXR (Zhou et al., 2006, 2008). A recent report showed that the thyroid hormone (TH)-responsive spot 14 protein, the expression of which correlates with lipogenesis, was a PXR target gene (Breuker et al., 2010). Therefore, the induction of spot 14 may have also contributed to the lipogenic effect of PXR. Treatment of mice with the PXR agonist pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile (PCN) is known to alleviate the lithocholic acid-induced hepatotoxicity (Staudinger et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2001). It was recently reported that the PCN-mediated stimulation of lipogenesis contributes to the protection from lithocholic acid-induced hepatotoxicity (Miyata et al., 2010).

The steatotic effect of PXR was also associated with suppression of several genes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation. Activation of PXR by its agonist PCN can inhibit lipid oxidation by down-regulating the mRNA expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1α (CPT1α) and mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate-CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2), two key enzymes involved in β-oxidation and ketogenesis, in a PXR-dependent manner. Mechanistically, it has been shown that PXR can directly interact with Forkhead box A2 (FoxA2) and prevent FoxA2 binding to the Cpt1a and Hmgcs2 gene promoters (Nakamura et al., 2007). Finally, unlike CAR, activation of PXR had little effect on the lipogenic effect of LXR (Zhai et al., 2010).

Effects of PXR and CAR on Hepatic Glucose Metabolism.

Chronic treatment with PB has been reported to decrease plasma glucose levels and improve insulin sensitivity in diabetic patients (Lahtela et al., 1985). Treatment with PB suppressed the expression of gluconeogenic enzymes PEPCK1 and G6Pase in mouse liver (Ueda et al., 2002) and in primary rat hepatocytes (Argaud et al., 1991). The regulation of the gluconeogenic pathway by PXR was initially suggested by the suppression of PEPCK and G6Pase in VP-hPXR transgenic mice (Zhou et al., 2006). Treatment of wild-type mice with the PXR agonist PCN also suppressed cAMP-dependent induction of G6Pase in a PXR-dependent manner (Kodama et al., 2004). Several possible but not mutually exclusive molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain the inhibitory effect of PXR and CAR on gluconeogenesis. It was reported that PXR can form a complex with phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in a ligand-dependent manner to prevent CREB binding to the cAMP response element and inhibit CREB-mediated transcription of G6Pase (Kodama et al., 2007). PXR and CAR can also physically bind to FoxO1 and suppress its transcriptional activity by preventing its binding to the insulin response sequence in the gluconeogenic enzyme gene promoters (Kodama et al., 2004). PXR and CAR may also inhibit hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α activity by competing for the DR1 (direct repeat spaced by one nucleotide) binding motif in the gluconeogenic enzyme gene promoters (Miao et al., 2006). The in vivo significance of CAR-mediated suppression of gluconeogenesis was supported by two recent reports that activation of CAR ameliorated hyperglycemia and improved insulin sensitivity in ob/ob mice and high-fat diet fed wild-type mice (Dong et al., 2009b; Gao et al., 2009).

CAR May Impact Energy Metabolism and Fasting Response by Affecting Thyroid Hormone Metabolism.

It has been reported that the expression of CAR was inducted during long-term fasting, possibly due to the up-regulation of PGC-1α (Ding et al., 2006). Moreover, CAR-deficient mice were defective in fasting adaptation and lost more weight during calorie restriction (Maglich et al., 2004). One possible mechanism by which CAR affects fasting response is through the effect of CAR on TH metabolism. Treatment of wild-type mice with a CAR agonist decreased serum T4 level (Qatanani et al., 2005). The decrease in T4 level was associated with a concomitant increase in the serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level in wild-type but not in CAR(−/−) mice. The effect of CAR on TH homeostasis was believed to be achieved through the regulation of TH-metabolizing Phase II enzymes. Activation of CAR induced the expression of glucuronosyltransferases UGT1A1 and 2B1 and sulfotransferases SULT2A1, 1C1, and 1E1 in wild-type mice but not in CAR(−/−) mice. UGT1A1 and UGT2B1 are responsible for T4 and T3 glucuronidation, respectively (Visser et al., 1993a,b). SULTs are important for the inactivation of THs by blocking outer ring deiodination and causing irreversible inactivation of THs (Visser, 1994). However, the net effect of CAR on TH homeostasis remains controversial. It was reported that activation of CAR decreased the serum reverse T3 level, resulting in the desuppression of thyroid hormone target genes during partial hepatectomy (Tien et al., 2007).

Conclusions and Perspectives

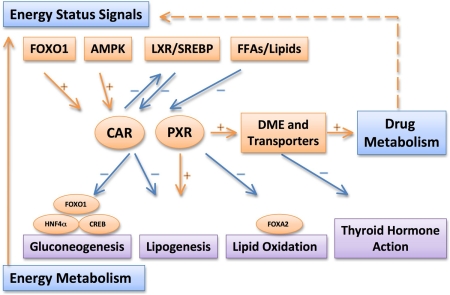

Figure 1 summarizes the major interactions between drug metabolism and energy metabolism and the central roles of PXR and CAR in these cross-talks. Induction or suppression of P450s and other drug-metabolizing enzymes can alter drug metabolism and clearance. Our understanding of the regulation of drug metabolism and activities of PXR and CAR by liver energy status may offer possible explanations for the variation of drug responses associated with metabolic diseases and provide rationale for appropriate dose adjustment. On the other hand, activation of PXR and CAR could have a significant impact on energy homeostasis by affecting lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and fatty acid oxidation. It is tempting to speculate that pharmacological modulation of PXR and CAR may be beneficial in managing metabolic diseases.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the major interactions between drug metabolism and energy metabolism and the central roles of PXR and CAR in these cross-talks. Note that the drug metabolism and energy status can be affected by pathophysiological conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver. DME, drug-metabolizing enzymes; FFA, free fatty acids; HNF4α, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α.

Among the remaining challenges, although PXR has been shown to affect lipid and glucose metabolism, the in vivo role of PXR in obesity and type II diabetes remains to be demonstrated. The endogenous ligands for PXR and CAR that elicit the metabolic functions of these two receptors also remain to be identified.

Biographies

Jie Gao is a senior graduate student from the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy. He received his B.S. and M.S. degrees from China Pharmaceutical University before entering the Graduate Program of Pharmaceutical Sciences in 2006. He has authored five peer-reviewed articles with his thesis advisor Dr. Wen Xie. Among his achievements, Mr. Gao received the Norman R. and Priscilla A. Farnsworth Student Award and Molecular Pharmacology Fellowship from University of Pittsburgh.

Wen Xie is Associate Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pharmacology from the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Xie obtained his MD degree from Peking University Health Science Center and PhD in Cell Biology from University of Alabama at Birmingham. He completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the Salk Institute before joining the faculty of Center for Pharmacogenetics and Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh in 2002. Dr. Xie's research focus is nuclear hormone receptor-mediated transcriptional regulation of genes that encode drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters. He has authored over 90 journal articles and book chapters. He currently serves as ad hoc reviewer for the National Institutes of Health and Department of Defense Study Sections and nearly 40 scientific journals. Among his achievements, Dr. Xie is the recipient of the 2008 University of Pittsburgh Chancellor's Distinguished Research Award, 2008 James R. Gillette ISSX North American New Investigator Award, and 2009 ASPET Division for Drug Metabolism Early Career Achievement Award.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Grant ES014626]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [Grant DK076962]; and a Molecular Pharmacology Fellowship funded by the University of Pittsburgh Department of Pharmacology and Chemical Biology.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/dmd.110.035568.

- P450

- cytochrome P450

- PXR

- pregnane X receptor

- SULTs

- sulfotransferases

- CAR

- constitutive androstane receptor

- PB

- phenobarbital

- TCPOBOP

- 1,4-Bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- NASH

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- SREBP-1

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- PAR bZip

- PAR-domain basic leucine zipper

- PGC-1α

- peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor-γ-coactivator-1α

- FOXO1

- Forkhead box O1 protein

- CPR

- cytochrome P450 reductase

- PPARγ2

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2

- TH

- thyroid hormone

- PCN

- pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile

- CPT1α

- carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1α

- HMGCS2

- 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate-CoA synthase 2

- FoxA2

- Forkhead box A2

- CREB

- cAMP response element-binding protein

- PEPCK

- phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- AICAR

- 5-amino-1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1H-imidazole-4-carboxamide.

References

- Argaud D, Halimi S, Catelloni F, Leverve XM. (1991) Inhibition of gluconeogenesis in isolated rat hepatocytes after chronic treatment with phenobarbital. Biochem J 280 (Pt 3):663–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blättler SM, Rencurel F, Kaufmann MR, Meyer UA. (2007) In the regulation of cytochrome P450 genes, phenobarbital targets LKB1 for necessary activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:1045–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin RA, Warren GW. (1999) Pharmacokinetic considerations in obesity. J Pharm Sci 88:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg B, Sabbagh W, Jr, Juguilon H, Bolado J, Jr, van Meter CM, Ong ES, Evans RM. (1998) SXR, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev 12:3195–3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuker C, Moreau A, Lakhal L, Tamasi V, Parmentier Y, Meyer U, Maurel P, Lumbroso S, Vilarem MJ, Pascussi JM. (2010) Hepatic expression of thyroid hormone-responsive spot 14 protein is regulated by constitutive androstane receptor (NR1I3). Endocrinology 151:1653–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheymol G. (2000) Effects of obesity on pharmacokinetics implications for drug therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 39:215–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waziers I, Garlatti M, Bouguet J, Beaune PH, Barouki R. (1995) Insulin down-regulates cytochrome P450 2B and 2E expression at the post-transcriptional level in the rat hepatoma cell line. Mol Pharmacol 47:474–479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Lichti K, Kim I, Gonzalez FJ, Staudinger JL. (2006) Regulation of constitutive androstane receptor and its target genes by fasting, cAMP, hepatocyte nuclear factor alpha, and the coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha. J Biol Chem 281:26540–26551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato MT, Jiménez N, Serralta A, Mir J, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ. (2007) Effects of steatosis on drug-metabolizing capability of primary human hepatocytes. Toxicol In Vitro 21:271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato MT, Lahoz A, Jiménez N, Pérez G, Serralta A, Mir J, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ. (2006) Potential impact of steatosis on cytochrome P450 enzymes of human hepatocytes isolated from fatty liver grafts. Drug Metab Dispos 34:1556–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Qatanani M, Moore DD. (2009a) Constitutive androstane receptor mediates the induction of drug metabolism in mouse models of type 1 diabetes. Hepatology 50:622–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Saha PK, Huang W, Chen W, Abu-Elheiga LA, Wakil SJ, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva O, Newgard CB, Chan L, et al. (2009b) Activation of nuclear receptor CAR ameliorates diabetes and fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:18831–18836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiatarone JR, Coverdale SA, Batey RG, Farrell GC. (1991) Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: impaired antipyrine metabolism and hypertriglyceridaemia may be clues to its pathogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 6:585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Henderson CJ, Scott CL, Wolf CR. (2009) Unsaturated fatty acid regulation of cytochrome P450 expression via a CAR-dependent pathway. Biochem J 417:43–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, McLaren AW, Carrie D, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. (2007) Conditional deletion of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase in the liver and gastrointestinal tract: a new model for studying the functions of the P450 system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322:40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CD, Lickteig AJ, Augustine LM, Ranger-Moore J, Jackson JP, Ferguson SS, Cherrington NJ. (2009) Hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme alterations in humans with progressive stages of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 37:2087–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman BM, Tzameli I, Choi HS, Chen J, Simha D, Seol W, Evans RM, Moore DD. (1998) Androstane metabolites bind to and deactivate the nuclear receptor CAR-beta. Nature 395:612–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachon F, Olela FF, Schaad O, Descombes P, Schibler U. (2006) The circadian PAR-domain basic leucine zipper transcription factors DBP, TEF, and HLF modulate basal and inducible xenobiotic detoxification. Cell Metab 4:25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, He J, Zhai Y, Wada T, Xie W. (2009) The constitutive androstane receptor is an anti-obesity nuclear receptor that improves insulin sensitivity. J Biol Chem 284:25984–25992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnerre C, Schuster GU, Roth A, Handschin C, Johansson L, Looser R, Parini P, Podvinec M, Robertsson K, Gustafsson JA, et al. (2005) LXR deficiency and cholesterol feeding affect the expression and phenobarbital-mediated induction of cytochromes P450 in mouse liver. J Lipid Res 46:1633–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Simpson A, Saenger P. (1990) Hepatic drug metabolism is increased in poorly controlled insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 123:550–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Weng Y, Zhang QY, Cui H, Behr M, Wu L, Yang W, Zhang L, Ding X. (2003) Liver-specific deletion of the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene: impact on plasma cholesterol homeostasis and the function and regulation of microsomal cytochrome P450 and heme oxygenase. J Biol Chem 278:25895–25901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handschin C, Meyer UA. (2003) Induction of drug metabolism: the role of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Rev 55:649–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson CJ, Otto DM, Carrie D, Magnuson MA, McLaren AW, Rosewell I, Wolf CR. (2003) Inactivation of the hepatic cytochrome P450 system by conditional deletion of hepatic cytochrome P450 reductase. J Biol Chem 278:13480–13486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno Y, Inoue Y, Inoue Y. (2010) 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-ribofuranoside (AICAR) prevents nuclear translocation of constitutive androstane receptor by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) independent manner. J Toxicol Sci 35:571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterström RH, et al. (1998) An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell 92:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S, Koike C, Negishi M, Yamamoto Y. (2004) Nuclear receptors CAR and PXR cross talk with FOXO1 to regulate genes that encode drug-metabolizing and gluconeogenic enzymes. Mol Cell Biol 24:7931–7940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S, Moore R, Yamamoto Y, Negishi M. (2007) Human nuclear pregnane X receptor cross-talk with CREB to repress cAMP activation of the glucose-6-phosphatase gene. Biochem J 407:373–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahtela JT, Arranto AJ, Sotaniemi EA. (1985) Enzyme inducers improve insulin sensitivity in non-insulin-dependent diabetic subjects. Diabetes 34:911–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamia KA, Sachdeva UM, DiTacchio L, Williams EC, Alvarez JG, Egan DF, Vasquez DS, Juguilon H, Panda S, Shaw RJ, et al. (2009) AMPK regulates the circadian clock by cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science 326:437–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq I, Horsmans Y, Desager JP, Delzenne N, Geubel AP. (1998) Reduction in hepatic cytochrome P-450 is correlated to the degree of liver fat content in animal models of steatosis in the absence of inflammation. J Hepatol 28:410–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CC, Lii CK, Liu KL, Yang JJ, Chen HW. (2007) DHA down-regulates phenobarbital-induced cytochrome P450 2B1 gene expression in rat primary hepatocytes by attenuating CAR translocation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 225:329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long YC, Zierath JR. (2006) AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in metabolic regulation. J Clin Invest 116:1776–1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Shah Y, Cheung C, Guo GL, Feigenbaum L, Krausz KW, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. (2007) The PREgnane X receptor gene-humanized mouse: a model for investigating drug-drug interactions mediated by cytochromes P450 3A. Drug Metab Dispos 35:194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglich JM, Watson J, McMillen PJ, Goodwin B, Willson TM, Moore JT. (2004) The nuclear receptor CAR is a regulator of thyroid hormone metabolism during caloric restriction. J Biol Chem 279:19832–19838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J, Fang S, Bae Y, Kemper JK. (2006) Functional inhibitory cross-talk between constitutive androstane receptor and hepatic nuclear factor-4 in hepatic lipid/glucose metabolism is mediated by competition for binding to the DR1 motif and to the common coactivators, GRIP-1 and PGC-1alpha. J Biol Chem 281:14537–14546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata M, Nomoto M, Sotodate F, Mizuki T, Hori W, Nagayasu M, Yokokawa S, Ninomiya S, Yamazoe Y. (2010) Possible protective role of pregnenolone-16 alpha-carbonitrile in lithocholic acid-induced hepatotoxicity through enhanced hepatic lipogenesis. Eur J Pharmacol 636:145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Moore R, Negishi M, Sueyoshi T. (2007) Nuclear pregnane X receptor cross-talk with FoxA2 to mediate drug-induced regulation of lipid metabolism in fasting mouse liver. J Biol Chem 282:9768–9776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascussi JM, Gerbal-Chaloin S, Duret C, Daujat-Chavanieu M, Vilarem MJ, Maurel P. (2008) The tangle of nuclear receptors that controls xenobiotic metabolism and transport: crosstalk and consequences. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 48:1–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pass GJ, Carrie D, Boylan M, Lorimore S, Wright E, Houston B, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. (2005) Role of hepatic cytochrome p450s in the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of cyclophosphamide: studies with the hepatic cytochrome p450 reductase null mouse. Cancer Res 65:4211–4217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ. (1998) Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell 93:693–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qatanani M, Zhang J, Moore DD. (2005) Role of the constitutive androstane receptor in xenobiotic-induced thyroid hormone metabolism. Endocrinology 146:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rencurel F, Foretz M, Kaufmann MR, Stroka D, Looser R, Leclerc I, da Silva Xavier G, Rutter GA, Viollet B, Meyer UA. (2006) Stimulation of AMP-activated protein kinase is essential for the induction of drug metabolizing enzymes by phenobarbital in human and mouse liver. Mol Pharmacol 70:1925–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rencurel F, Stenhouse A, Hawley SA, Friedberg T, Hardie DG, Sutherland C, Wolf CR. (2005) AMP-activated protein kinase mediates phenobarbital induction of CYP2B gene expression in hepatocytes and a newly derived human hepatoma cell line. J Biol Chem 280:4367–4373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa JJ, Liang G, Ou J, Bashmakov Y, Lobaccaro JM, Shimomura I, Shan B, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Mangelsdorf DJ. (2000) Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev 14:2819–2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Looser R, Kaufmann M, Meyer UA. (2008a) Sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 interacts with pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor and represses their target genes. Pharmacogenet Genomics 18:325–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Looser R, Kaufmann M, Blättler SM, Rencurel F, Huang W, Moore DD, Meyer UA. (2008b) Regulatory cross-talk between drug metabolism and lipid homeostasis: constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor increase Insig-1 expression. Mol Pharmacol 73:1282–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma T, Honma R, Maguchi S, Tamaki H, Nemoto N. (2001) Different expression of hepatic and renal cytochrome P450s between the streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse and rat. Xenobiotica 31:223–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo S, Numazawa S, Yoshida T. (2007) A physiological role of AMP-activated protein kinase in phenobarbital-mediated constitutive androstane receptor activation and CYP2B induction. Biochem J 401:735–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu JS, Omiecinski CJ. (1999) Insulin-mediated modulation of cytochrome P450 gene induction profiles in primary rat hepatocyte cultures. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 13:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC, Tew DG, Wolf CR. (1994) Dissection of NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase into distinct functional domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:8710–8714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger JL, Goodwin B, Jones SA, Hawkins-Brown D, MacKenzie KI, LaTour A, Liu Y, Klaassen CD, Brown KK, Reinhard J, et al. (2001) The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:3369–3374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su GM, Sefton RM, Murray M. (1999) Down-regulation of rat hepatic microsomal cytochromes P-450 in microvesicular steatosis induced by orotic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291:953–959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien ES, Matsui K, Moore R, Negishi M. (2007) The nuclear receptor constitutively active/androstane receptor regulates type 1 deiodinase and thyroid hormone activity in the regenerating mouse liver. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 320:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda A, Hamadeh HK, Webb HK, Yamamoto Y, Sueyoshi T, Afshari CA, Lehmann JM, Negishi M. (2002) Diverse roles of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR in regulating hepatic genes in response to phenobarbital. Mol Pharmacol 61:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ. (1994) Role of sulfation in thyroid hormone metabolism. Chem Biol Interact 92:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ, Kaptein E, van Raaij JA, Joe CT, Ebner T, Burchell B. (1993a) Multiple UDP-glucuronyltransferases for the glucuronidation of thyroid hormone with preference for 3,3′,5′-triiodothyronine (reverse T3). FEBS Lett 315:65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser TJ, Kaptein E, van Toor H, van Raaij JA, van den Berg KJ, Joe CT, van Engelen JG, Brouwer A. (1993b) Glucuronidation of thyroid hormone in rat liver: effects of in vivo treatment with microsomal enzyme inducers and in vitro assay conditions. Endocrinology 133:2177–2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Zhang J, Egan-Hafley M, Liang S, Moore DD. (2000) The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature 407:920–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Barwick JL, Downes M, Blumberg B, Simon CM, Nelson MC, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. (2000) Humanized xenobiotic response in mice expressing nuclear receptor SXR. Nature 406:435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Radominska-Pandya A, Shi Y, Simon CM, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Waxman DJ, Evans RM. (2001) An essential role for nuclear receptors SXR/PXR in detoxification of cholestatic bile acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:3375–3380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y, Wada T, Zhang B, Khadem S, Ren S, Kuruba R, Li S, Xie W. (2010) A functional crosstalk between LXR{alpha} and CAR links lipogenesis and xenobiotic responses. Mol Pharmacol 78:666–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WV, Ramzan I, Murray M. (2007) Impaired microsomal oxidation of the atypical antipsychotic agent clozapine in hepatic steatosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322:770–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Zhai Y, Mu Y, Gong H, Uppal H, Toma D, Ren S, Evans RM, Xie W. (2006) A novel pregnane X receptor-mediated and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-independent lipogenic pathway. J Biol Chem 281:15013–15020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Febbraio M, Wada T, Zhai Y, Kuruba R, He J, Lee JH, Khadem S, Ren S, Li S, et al. (2008) Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARγ in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology 134:556–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zysset T, Wietholtz H. (1988) Differential effect of type I and type II diabetes on antipyrine disposition in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 34:369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]