Abstract

Vitex agnus-castus (VAC) has been used since ancient Greek times and has been shown clinically to be effective for the treatment of pre-menstrual syndrome. However, its mechanism of action has only been partially determined. Compounds, fractions, and extracts isolated from VAC were used in this study to thoroughly investigate possible opioidergic activity. First, an extract of VAC was found to bind and activate μ- and δ-, but not κ- opioid receptor subtypes (MOR, DOR, and KOR respectively). The extract was then resuspended in 10% methanol and partitioned sequentially with petroleum ether, CHCl3, and EtOAc to form four fractions including a water fraction. The highest affinity for MOR was concentrated in the CHCl3 fraction, whereas the highest affinity for DOR was found in the CHCl3 and EtOAc fractions. However, the petroleum ether fraction had the highest agonist activity at MOR and DOR. Several flavonoids from VAC were found to bind to both MOR and DOR in a dose-dependent manner; however only casticin, a marker compound for genus Vitex, was found to have agonist activity selective for DOR at high concentrations. These results suggest VAC may exert its therapeutic effects through the activation of MOR, DOR, but not KOR.

Keywords: Pain, botanical, plant, premenstrual syndrome, menopause

1. Introduction

The dried ripe fruit of Vitex agnus-castus L. (VAC) (Lamiaceae; formerly Verbenaceae), commonly known as chasteberry, is one of the most popular and effective herbs used for the prevention and treatment of pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) in Western culture [1-4]. PMS refers to a variety of emotional, behavioral, and physical symptoms that occur in the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, up to two weeks before the onset of menses [5]. Vitex agnuscastus has been shown clinically to be effective against PMS symptoms such as depression, irritability, anxiety, mastalgia, fatigue, and headache [2, 4, 6]. The exact mechanism of action of this herb is not known, although it has been shown that VAC inhibits prolactin release [7, 8] by activating the dopamine D2 receptors in the anterior pituitary [9, 10].

Extracts of VAC have also been reported to have affinity to the opioid μ, δ, or κ receptors (MOR, DOR, and KOR, respectively). One study found VAC had high affinity to MOR and KOR, and weak affinity for DOR [9]. More recently, it was reported that two VAC methanol extracts activated MOR in addition to having receptor affinity [11]. However, it is still unknown whether VAC acts as an agonist at DOR or KOR. In this study, a 90% methanol extract (characterized by HPLC-PDA), several fractions, as well as several flavonoids isolated from VAC were examined for their affinity and activity at all three opioid receptor subtypes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Drugs and reagents

Reference compounds (agnuside (87.0% w/w), casticin (97.5%w.w), and vitexilactone (98.0% w/w)) were obtained from Chromadex (Santa Ana, CA). [D-Ala2,N-MePhe4-Glyol5]enkephalin (DAMGO), SNC-80, [3H]DAMGO, and [3H]deltorphin (Tyr-D-Ala-Phe-Glu-Val-Val-Gly) were purchased from Multiple Peptide Systems (San Diego, CA). ICI 174,864 (N,N-diallyl-Tyr-Aib-Aib-Phe-Leu-OH: Aib = alpha-aminoisobutyric acid) was purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO). [3H]Diprenorphine was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA). [35S]GTPγS (Guanosine-5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) lithium salt was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Luteolin and apigenin were also obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) with a purity of >98% and >95% respectively. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise noted.

2.2 Preparation of plant material

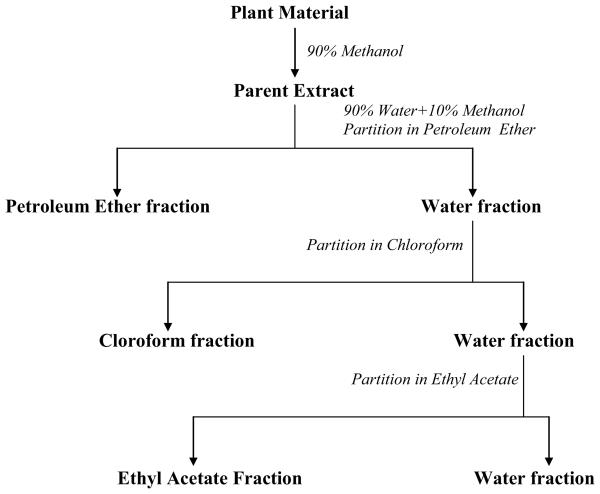

The fruits of VAC were provided by Pure World Botanicals (now Naturex), Inc (South Hackensack, NJ) from cultivated material grown in New Mexico, USA and verified by comparison with authenticated material. Voucher specimens have been deposited at the UIC/NIH Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The extraction scheme that was used to prepare the primary extract and four fractions is described in Figure 1. Five kilograms of VAC fruits were extracted by maceration with 90% methanol (3.125% w/w). This extract was then dried in vacuo and resuspended in 10% methanol, and then partitioned with petroleum ether (PE) (0.304% w/w), CHCl3 (0.344% w/w), EtOAc (0.441% w/w) to form four fractions, including a final water (2.036% w/w) fraction. Samples were again evaporated in vacuo to obtain dry fractions. Samples to be characterized by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) were dissolved in 80% methanol (V/V) at a concentration of 30mg(dried extract)/mL and sonicated for 10 min. The resulting solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter into an HPLC vial. All reference standards were dissolved in 80% methanol. In addition, plant extracts were spiked with agnuside, casticin, or vitexilactone to ensure proper identification of marker compounds. For pharmacological assays, samples were initially dissolved in DMSO and diluted with distilled deionized water to appropriate concentrations immediately prior to each assay. The final DMSO concentration in all assays was below 0.5%, which was not found to interfere with either receptor binding or GTPγS binding assay.

Figure 1.

Extraction and fractionation of VAC. VAC was first extracted by maceration with 90% methanol, suspended in 10% methanol, and then partitioned with PE, CHCl3, EtOAc, and water.

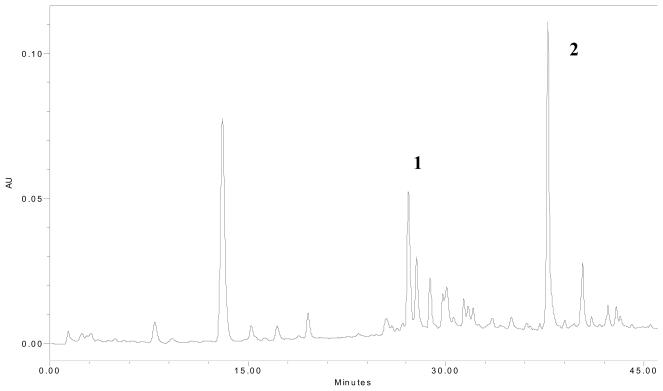

2.3 Characterization of plant material

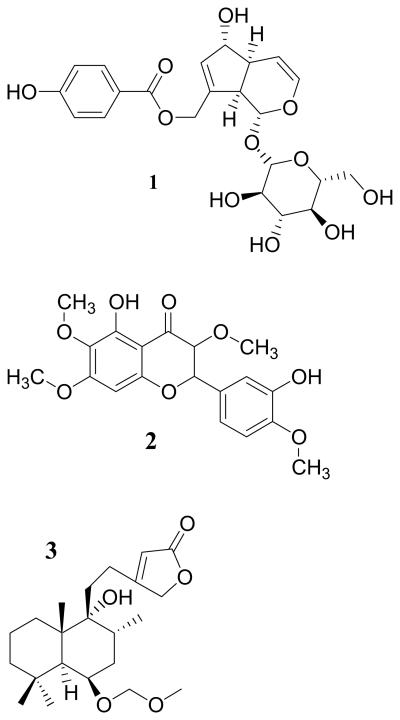

Plant materials were morphologically compared with authenticated specimens and characterized by HPLC (Waters Delta 600, equipped with a 996 photodiode array detector, online degasser, and autosampler) using a fingerprinting method previously described for the identification of agnuside, casticin, and vitexilactone [9]. These compounds are commercially available and are commonly used as marker compounds for the Vitex genus (Figure 2) [12, 13]. The methanol extract was analyzed using a reversed phase 125 × 4.0 mm 5 μm Hypersil ODS C18 column (Agilent). Chromatographic elution was accomplished by a gradient solvent system consisting of methanol (A) and 0.5% phosphoric acid in water (B). The gradient conditions were: 0 min, 5:95 (v:v); 15 min, 27:73; 20 min, 35:65; 26 min 52:48; 33 min 80:20; 37 min 100:0. Total run time was 46 min. The flow rate was 1.3ml/min, and the injection volume was 10 μl. Agnuside and casticin were detected at 258 nm and vitexilactone was detected at 210 nm. The eluted constituents were identified based on the retention time and PDA chromatograms of both single standards and spiked extracts.

Figure 2.

Structures of reference compounds used for the identification of VAC. (1) Agnuside is an iridoid glycoside, (2) casticin is a flavonoid, and (3) vitexilactone is a diterpene.

2.4 Cell Culture

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing the human MOR (CHO-MOR) [11], the human DOR (CHO-DOR) [14], and the KOR (CHO-KOR, a generous gift from Dr. L. Liu-Chen of Temple University) [15] were used. Cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. To maintain stable selection, G418 (200 μg/ml) was added to MOR and KOR cell media and hygromycin (200 μg/ml) was added to DOR cell media. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in humidified air.

2.5 Receptor binding assay

The receptor binding assay was performed as previously described [11, 16]. Briefly, receptor membranes were prepared from each cell line by glass homogenizer (30 strokes) on ice, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 45 min at 4°C. Protein content was determined by a modified Bradford protein assay method (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Receptor displacement assays were conducted in triplicate in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 nM [3H]DAMGO (MOR), 1 nM [3H]Deltorphin (DOR), or 2 nM [3H]Diprenorphine (KOR) at 30°C for 1 h (MOR and KOR) or 3h (DOR). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 20 μM naloxone (MOR), 20 μM SNC-80 (DOR), or 20 μM norBNI (KOR). Naloxone and the MOR-selective antagonist CTOP did not differ in non-specific binding values, so naloxone was used in the study since it is more stable. Reactions were terminated by the rapid vacuum filtration through GF/B filters presoaked with 0.2% polyethylenimine. Filter-bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Data were analyzed with the aid of the GraphPad Prism program (San Diego, CA) using the non-linear regression sigmoidal curve fit (variable slope) equation to obtain Bmax and IC50. The dissociation constant Ki values were determined by the method of Cheng and Prusoff [17].

2.6 Mechanism of interaction between opioid receptors and VAC extract

The mode of receptor binding by VAC methanol extract was further characterized in order to determine competitive/uncompetitive versus noncompetitive binding to the opioid receptors. To obtain Kd and Ki values at MOR, [3H]DAMGO ranging from 0.1 to 4 nM and VAC methanol extract at 0, 100 μg/ml, or 200 μg/ml were used in the receptor binding assay as described above. To obtain Kd and Ki values at DOR, [3H]deltorphin ranging from 0.1 to 4 nM and VAC methanol extract at 0, 50 μg/ml, 100 μg/ml for DOR were used in the receptor binding assay. Radioactivity was determined as described above and data were converted to fmol/mg protein. Data were further transformed into a double-reciprocal plot to determine the mechanism of receptor-ligand interaction [18]. The Kd was derived from 1/(x-intercept) and Bmax was derived from 1/(y-intercept) as determine by linear regression using the GraphPad Prism program (San Diego, CA).

2.7 GTPγS binding assay

In order to determine whether VAC acts as an agonist, [35S]GTPγS binding assay was performed as previously described [18]. Briefly, cell membranes were prepared as above. Membranes (20 μg protein) were incubated with 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS (1,000 Ci/mmol) in reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 5 mM magnesium chloride, 3 μM guanosine-5′-diphosphate (GDP), 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.1% BSA) in the presence or absence of VAC extracts or positive control (DAMGO for MOR or SNC-80 for DOR), at 30°C for 1 hr (MOR) or 3 hr (DOR). Because the extract did not show affinity to this receptor, samples were not tested for activity at KOR. The basal level was defined as the amount [35S]GTPγS bound in the absence of any agonist. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM unlabeled GTPγS and subtracted from all data. Reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filters, followed by 3 washes with ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4). The membrane-bound [35S]GTPγS was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Data were analyzed with the aid of program GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) using non-linear regression sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope) to obtain Emax and EC50.

2.8 Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error. For comparisons among multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's t test was used. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student's t test. Statistical significance is established at 95% confidence level.

3. Results

3.1 Receptor binding assay

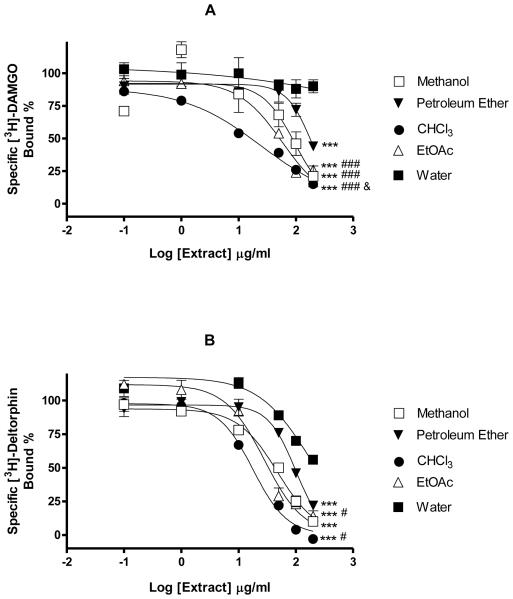

A VAC 90% methanol extract and several fractions (PE, CHCl3, EtOAc, and water) were examined for their affinity at the three human opioid receptors. The VAC methanol extract and PE, CHCl3, and EtOAc fractions were able to displace the binding of [3H]DAMGO to MOR in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating their affinity to MOR (Fig. 4A). The parent extract had an IC50 of 88.4±8.47 μg/mL (Ki=33.2±3.23 μg/mL). Of the four fractions, the CHCl3 fraction had the highest affinity for the MOR receptor, with an IC50 of 23.8±2.81 μg/mL (Ki=8.85±1.12 μg/mL), followed by the EtOAc fraction (IC50=62.2±18.5 μg/mL, Ki=23.3±6.79 μg/mL), and the PE fraction (IC50=188±11.5 μg/mL, Ki=70.4±4.33 μg/mL). The water fraction had no affinity for the MOR receptor. The MOR agonist DAMGO was used as a positive control in these experiments.

Figure 4.

Displacement of [3H]DAMGO (1 nM) binding by VAC extracts and fractions to MOR cells (A) and DOR (B). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. IC50: *** P<0.001 Water vs other groups, # P<0.05, ### P<0.001 Petroleum Ether vs other groups, & P<0.05 Methanol vs CHCl3.

Similar to the DOR selective ligand SNC-80, all fractions demonstrated an affinity to DOR by displacing the binding of [3H]deltorphin in CHO-DOR cells (Fig. 4B). The methanol extract had an IC50 of 43.0±7.78 μg/mL (Ki=22.1±3.95 μg/mL). The CHCl3 (IC50=21.4±3.84 μg/mL, Ki=11.0 ± 2.02 μg/mL) and EtOAc (IC50=20.7 ± 16.9 μg/mL, Ki=10.7 ± 8.68 μg/mL) fractions showed the highest affinity to the DOR receptor, followed by the PE fraction (IC50=107±26.6 μg/mL, Ki=55.1±13.7 μg/mL). The water fraction had no affinity for the DOR receptor. (IC50 > 500 μg/mL ). The DOR selective agonist SNC-80 was used as a positive control and completely displaced [3H]deltorphin with an IC50 of 2.48×10−2 nM (1.12×10−2 ng/mL) and a Ki of 4.53×10−2 nM.

Unlike the positive control NorBNI, the 90% methanol extract did not displace the binding of [3H]diprenorphine at a concentration as high as 500 μg/ml, suggesting that this extract had no affinity (IC50 >500 μg/mL) to KOR. Similarly, none of the other four fractions showed affinity to KOR when tested at concentrations up to 500 μg/mL.

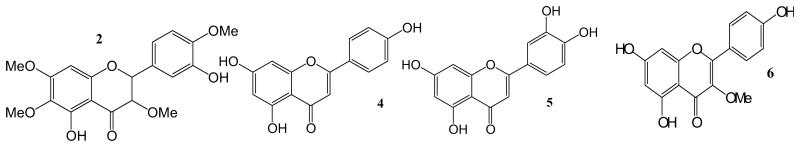

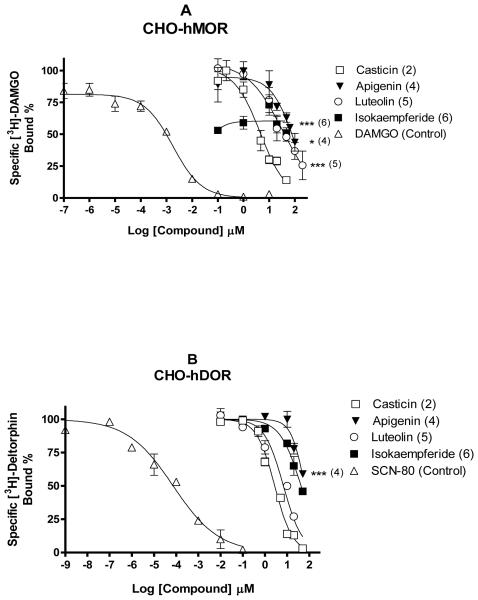

A number of compounds, including the marker compounds agnuside (1), casticin (2), and vitexilactone (3), have been isolated from VAC and structurally identified by the UIC/NIH Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research. These compounds were screened at 10 μM for their affinity to MOR and DOR. Of these compounds, several flavonoids demonstrated some affinity to MOR and/or DOR, including casticin (2), apigenin (4), luteolin (5), and isokaempferide (6) (Fig. 5). Because of the limited availability, further testing of these compounds was performed using commercially available materials. Of the four flavonoids tested (Fig. 6), casticin was found to have the highest affinity to MOR with an IC50 of 2.84±0.707 μM (Ki=1.14±0.167 μM) (Fig. 6). Luteolin and apigenin had much weaker affinity with an IC50 of 43.3 ± 13.2 μM (Ki=13.4 ± 4.06 μM) and 35.8 ± 7.81 μM (Ki=16.2±3.16 μM) respectively. Isokaempferide had no significant affinity to MOR. Casticin also had the highest affinity to DOR with an IC50 of 2.05±0.631 μM (Ki=1.29±0.440 μM). This was followed by luteolin and isokaempferide with IC50 of 16.8±4.87 μM (Ki=9.53±2.73 μM) and 22.8±14.0 μM (Ki=12.9±7.92 μM), respectively. Apigenin had a very weak affinity to DOR with an IC50>50 μM.

Figure 5.

Structures of flavonoids isolated from VAC that were found to dose-dependently displace the binding of [3H]DAMGO and/or [3H]deltorphin to the MOR and DOR: casticin (2), apigenin (4), luteolin (5), isokaempferide (6).

Figure 6.

Displacement of [3H]DAMGO (1 nM) binding by VAC flavonoids to MOR (A) and DOR (B). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of three experiments. IC50: * P<0.05, *** P<0.001 vs control.

3.2 Mechanism of receptor binding

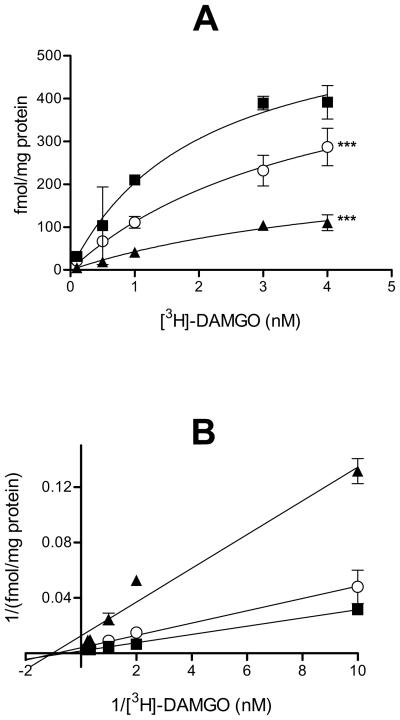

To investigate whether VAC acts as a competitive, noncompetitive, uncompetitive, or mixed inhibitor of binding to MOR, radioligand receptor saturation binding assays were carried out using several concentrations of [3H]DAMGO (0.1-4 nM) in the absence or presence of 100 or 200 μg/ml of VAC methanol extract. VAC significantly inhibited the saturation binding of [3H]DAMGO to MOR and as a result, the maximum binding (Bmax) was decreased by 62.2% and 88.3% with 100 and 200 μg/ml VAC respectively (Fig. 7A), however the apparent Kd of DAMGO for MOR remained approximately the same (Table 1). Further analysis using a double-reciprocal plot (Fig. 7B) indicated that the data were best explained by a noncompetitive mode where MOR-bound constituent(s) in VAC were still able to bind in the presence of DAMGO.

Figure 7.

Mechanism of [3H]DAMGO binding to MOR by VAC. (A) Saturation binding of [3H]DAMGO to MOR in absence or presence of 100 μM or 200 μM VAC (B) Reciprocal plots of the binding data of [3H]DAMGO to MOR: (■) no VAC, (○) 100 μg/ml VAC, and (▲) 200 μg/ml. Each point represents mean ± SEM (n=3). Bmax: *** P<0.001 vs “no VAC”.

Table 1.

Saturation binding of [3H]DAMGO and [3H]deltorphin to their receptors in the absence or presence of V. agnus-castus.

| VAC methanol extract (μg/ml) | Bmax (fmol/mg protein) | Kd (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 686±68.7 | 2.05±0.513 | |

| MOR | 100 | 259±69.9a | 1.02±0.221 |

| 200 | 80.5±10.0a | 1.23±0.615 | |

|

| |||

| 0 | 969±136 | 1.34±0.413 | |

| DOR | 50 | 526±103a | 2.17±0.841 |

| 100 | 370±75.2a | 1.89±0.972 | |

Radiolabeled ligand binding to MOR (by [3H]DAMGO) or DOR (by [3H]deltorphin) in the absence or presence of V. agnus-castus 90% methanol extract.

Values represent mean ± SEM. Bmax decreased as the concentration increased and Kd remained the same for both MOR and DOR indicating noncompetitive binding.

P<0.001 vs “0” group.

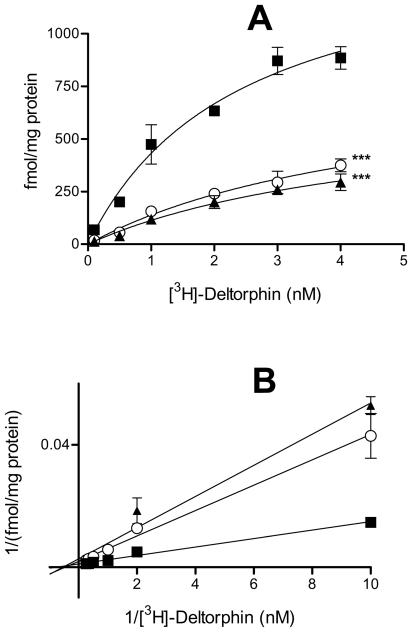

Similarly, saturation binding assays were performed using different concentrations of [3H]deltorphin (0.1-4 nM) in the absence or presence of 50 and 100 μg/ml of VAC methanol extract. VAC significantly inhibited the saturation binding of [3H]deltorphin to DOR and Bmax was decreased by 45.7 and 61.8% with 50 and 100 μg/ml VAC respectively (Fig. 8A); however the apparent Kd of [3H]deltorphin remained approximately the same (Table 1). Further analysis using a double-reciprocal plot (Fig. 8B) indicated that the data can be best described by a noncompetitive mode where the DOR-bound constituent(s) in VAC were still able to bind in the presence of deltorphin.

Figure 8.

Mechanism of [3H]deltorphin binding to DOR. (A) Saturation binding of [3H]deltorphin to DOR in absence or presence of 50 or 100 μM VAC (B) Reciprocal plots of the binding data of [3H]deltorphin to DOR: (■) no VAC, (○) 50 μg/ml VAC, and (▲) 100 μg/ml. Each point represents mean ± SEM (n=3). Bmax: *** P<0.001 vs “no VAC”.

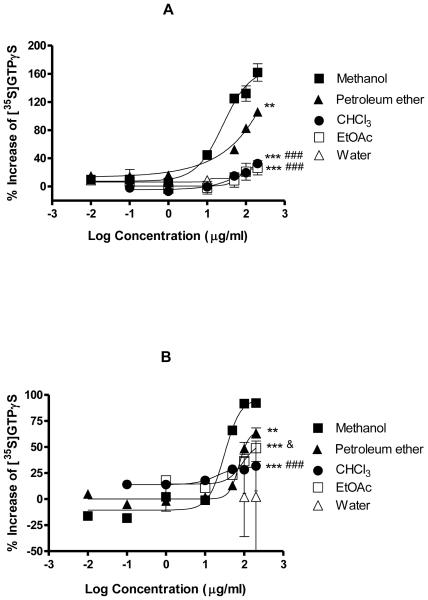

3.3 [35S]GTPγS binding assay

Opioid receptors belong to the superfamily of G-protein coupled receptors. Therefore, it is possible to measure receptor activation using the [35S]GTPγS binding assay where a radiolabeled, non-hydrolysable analogue of GTP accumulates in the cell membrane upon activation (Table 2). The VAC methanol extract stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding by 160% at 200 μg/ml (Emax), with an EC50 of 69.1 μg/mL. Naïve CHO cells (not transfected with MOR or DOR) were not stimulated by VAC or the positive control DAMGO (data not shown). At 200 μg/mL, the PE fraction (Emax=100%, EC50=45.2 μg/mL) produced the highest maximum stimulation of all four fractions, followed by the CHCl3 fraction (Emax=40.9%, EC50=14.5 μg/mL) and the EtOAc fraction (Emax=32.6%, EC50=67.7 μg/mL ). The water fraction did not activate MOR, which was in agreement with its lack of affinity to the receptor.

Table 2.

Activation of opioid receptors by VAC fractions using the GTPγS binding assay.

| MOR | DOR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emax (%) | EC50 (μg/ml) | Emax (%) | EC50 (μg/ml) | |

| Methanol | 160±3.94 | 69.1±27.5 | 96.7±2.26 | 42.8±5.88 |

| PE | 100±17.4a | 45.2±7.22 | 51.7±6.57a | 47.8±20.0 |

| CHCl3 | 40.9±8.42b,c | 14.5±4.08 | 34.7±5.81b,c | 9.56±5.71 |

| EtOAc | 32.6±6.13b,c | 67.7±0.871 | 43.6±5.43b,d | 86.8±3.32d |

| Water | -- | >500 | -- | >500 |

--: no activity;

Values represent mean ± SEM of percent stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding above baseline activity. DAMGO and SNC-80 served as positive controls for MOR and DOR, respectively.

P<0.01

P<0.001 vs Methanol

P<0.001 vs PE

P<0.05 vs CHCl3.

The maximum effect produced at DOR by the methanol extract was 97% above the baseline, with an EC50 of 42.8 μg/mL. Naïve CHO cells were not stimulated by the selective DOR agonist SNC-80 or VAC (data not shown). Of the fractions, the PE fraction produced the highest receptor activation (Emax=51.7%, EC50=47.8 μg/mL) followed by the EtOAc (Emax=43.6%, EC50=86.8 μg/mL) and CHCl3 fractions (Emax=34.7%, EC50=9.56 μg/ml). The water fraction produced no DOR activation.

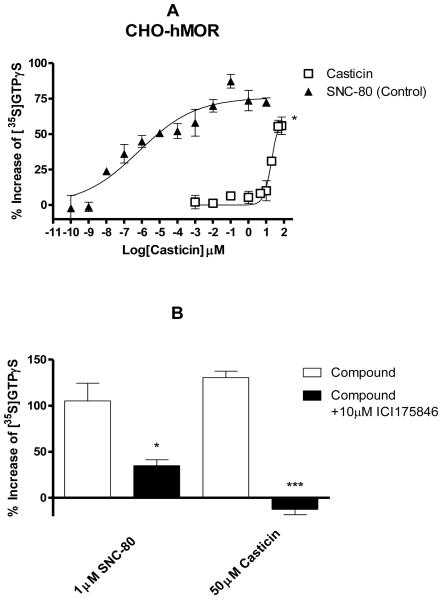

None of the four flavonoids tested were found to activate MOR. However, casticin activated DOR with an EC50 of 15.3±6.32 μM and an Emax of 74.6±18.2%. (Fig. 10A). Casticin stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (10 and 50 μM) was inhibited by the DOR selective antagonist ICI 174,864 (10 μM) (Fig. 10B).

Figure 10.

(A). Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by casticin in CHO-DOR cells. The EC50 was 15.3±6.32 μM with an Emax of 74.6±18.2% for casticin. SNC-80 was used as a positive control. EC50: * P<0.05 casticin vs SNC-80. (B). Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by casticin was blocked by the DOR selective antagonist ICI 174,864. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM and is representative of three experiments. * P<0.05, *** P<0.001 compared with compound alone.

4. Discussion

The botanical dietary supplement, VAC, has been shown to be effective for treating PMS, including premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a more severe form of PMS [2-4]. These symptoms include the cyclical occurrence of depressive moods, irritability, anxiety, confusion, mastalgia, fatigue, and headache [19], which are mediated or controlled by the central nervous system (CNS). In fact, the inverse correlation between the level of endogenous opiate peptides and severity of PMS has been proposed [20-25]. Although the endogenous and exogenous opioid agonists are primarily known for their ability to alter pain perception, the opiate system also plays an essential role in regulating mood, appetite, and hypothalamic-pituitary-axis (HPA) activity. The endogenous opiate peptide β-endorphin can regulate the menstrual cycle through the inhibition of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) in the hypothalamus, which is followed by the inhibition of the release of leutinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary, ultimately regulating estrogen and progesterone production in the ovaries [26]. Therefore, it was not surprising that opioid activity exhibited by VAC, mimicking endogenous opiate peptides, can be beneficial in attenuating PMS [9, 11]. In addition, an in vivo study reported a 105% increase in blood levels of β-endorphin after rats were fed with VAC for 4 days, although the exact relationship of brain and blood levels of β-endorphin has yet to be established [27].

Three opioid receptor subtypes (MOR, DOR, and KOR) have been identified. Of these, most studies have examined the involvement of MOR in the regulation of the menstrual cycle and female sex hormones. However, there is evidence that all three subtypes may be involved. First, most studies have focused on β-endorphin, which is only relatively selective for MOR, and can act on DOR and KOR. Second, met-enkephalin (a DOR preferring agonist) [28] or dynorphin (a KOR preferring agonist) [29] has been shown to inhibit the release of LH after systematic administration. Activation of KOR may have the dieresis action [30], which would provide relief from water retention seen in PMS. Activation of all opioid subtypes results in analgesia and reduces pain symptoms.

The purpose of this study was to investigate selectivity of VAC for opioid receptor subtypes by testing MOR, DOR, and KOR receptor pathways as a potential mechanism for VAC and to determine what compounds may be responsible for this activity. Although it has already been reported that VAC activates MOR, it is important to determine whether any other opioid receptor subtypes are also activated by this herb and what compounds are responsible for this activity.

A previous report found that VAC extracts had affinity to MOR and KOR, but little affinity for DOR. The latter activity was mostly found in the aqueous fraction [9]. However, the current study found that VAC had affinity to MOR and DOR, but not KOR. One explanation may be that receptor-binding assays are subject to interference by the presence of certain classes of phytochemicals such as fatty acids and tannins [31, 32]. For this reason, it is important to confirm binding data with functional assays. The present study, for the first time, showed that VAC extracts exhibit DOR agonistic activities and confirmed our previous report of agonistic activity at MOR.

Whereas there is a general agreement between receptor binding and activation data, the exact correlation was not consistent all the times. For example, the CHCl3 fractions had the highest affinity for MOR and DOR. The petroleum ether fraction, however, showed the strongest activation at both these receptors. This discrepancy may be due to several reasons. As discussed above, non-specific binding of inactive phytoconstituents may interfere with radioligand binding assays. Another explanation is that some fractions may contain a mixture of both opioid agonists and antagonists (see below). In addition, functional synergy would not be explained by receptor binding; therefore, receptor activation can exceed the effect that simple receptor binding can predict. For both MOR and DOR, the maximum receptor activation produced by each of the four fractions was less than that of the parent methanol extract. It is possible that extract works best in its entirety and loses (synergistic) activity when separated. This phenomenon has also been reported in a study on the dopaminergic activity of VAC and is commonly seen when isolating phytochemicals [10].

Four isolated compounds were found to have dose-dependent affinity for MOR and DOR. These compounds were all flavonoids. Of these flavonoids, only casticin, which has been reported to be present at up to 0.212% (w/w) in VAC [33], acted as a DOR agonist. Casticin is a methylated lipophilic flavonoid and is considered a marker compound of the Vitex genus. In this study, casticin was concentrated in the CHCl3 fraction. Because it is relatively lipophilic, there is a potential it can cross the blood brain barrier, although this has not been studied. Recently, several flavonoids, including apigenin, have been reported to act as opioid antagonists [34]. The present study did not study opioid antagonist activity from VAC; however, this would be consistent with the finding that several flavonoids had dose-dependent binding to a specific opioid receptor without agonistic activity. The presence of antagonistic activity may explain why a fraction, such as CHCl3, had higher affinity, but weaker receptor activation when compared with the PE fraction.

This study supports a potential mechanism of VAC through the activation of MOR and DOR, but not KOR. Comparison of four fractions (PE, CHCl3, and EtOAc, and water) revealed that, although most of the affinity was concentrated in the CHCl3 and EtOAc fractions, most of the agonist activity was found in the PE fraction, which may be indicative of a very potent non-polar opioid agonist. It remains unknown what (other) compound(s), and to what extent, contribute to the total activity demonstrated by VAC extract. Organic solvents used in the study (including methanol) are very volatile. All extracts were carefully dried. It is extremely unlikely that the receptor binding and activation were due to residual organic solvents. Moreover, if it was a solvent-mediated effect, the same affect should be observed with other herbal extracts. This is not the case, as many extracts from other plants failed to produce any effect in these assays (data not shown). These same extracts did not bind or activate KOR, which is very similar in sequence and signaling to MOR and DOR, further arguing against residual solvent interference.

None of the compounds tested were found to be MOR agonists, however casticin, a marker compound of the Vitex genus found in the CHCl3 fraction, was found to activate DOR at high concentrations. Casticin did not activate MOR, which is expected to be more important in alleviating PMS. Therefore, the active chemical constituents in VAC remain to be identified in future studies. Further studies are currently underway to examine opioid activity of VAC and casticin in vivo and to isolate additional compounds that may be active at the MOR.

In summary, opioid activity from VAC can be beneficial in attenuating PMS which may contribute to its clinical actions. Although opioid activity from VAC would be relatively weak when compared that from Papaver somniferum, Vitex agnus-castus has been used for hundreds of years without addiction problems. Further study of the mechanism of this herb may even provide insight into the mechanism and method of blocking opioid addiction.

Figure 3.

An HPLC chromatogram of a VAC 90% methanol extract at wavelength 254 nm. Compounds (1) agnuside, and (2) casticin are identified in this chromatogram. Vitexilactone was detected by UV at λ=210 nm but not at λ=254 nm; therefore, it was not present in this chromatograph.

Figure 9.

Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by VAC extracts and fractions in CHO-MOR (A) and CHO-DOR (B) cells. The activation of G proteins, indicative of receptor activation by agonist activities, was determined by the stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of three replicates and is representative of three experiments. Emax: ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001 Methanol vs other groups; ## P<0.01, ### P<0.001 Petroleum Ether vs other groups; & P<0.05 EtOAc vs CHCl3.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by NIH grants AT002406, AT003647, AT003476, and AT000155. Donna Webster was supported by an NIH predoctoral fellowship (F31AT002669). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM, ODS, or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hobbs C. Vitex: The Women's Herb. Healthy Living Publications; Summertown, TN: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective, randomised, placebo controlled study. Bmj. 2001;322(7279):134–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7279.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halaska M, Raus K, Beles P, Martan A, Paithner KG. Treatment of cyclical mastodynia using an extract of Vitex agnus castus: results of a double-blind comparison with a placebo. Ceska Gynekol. 1998;63(5):388–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauritzen C, Reuter HD, Repges R, Bohnert K-J, Schmidt U. Treatment of premenstrual tension syndrome with Vitex agnus casus: controlled, double-blind study versus pyridoxine. Phytomedicine. 1997;4(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(97)80066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapkin A. A review of treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(Suppl 3):39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atmaca M, Kumru S, Tezcan E. Fluoxetine versus Vitex agnus castus extract in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(3):191–5. doi: 10.1002/hup.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sliutz G, Speiser P, Schultz AM, Spona J, Zeillinger R. Agnus castus extracts inhibit prolactin secretion of rat pituitary cells. Horm Metab Res. 1993;25(5):253–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarry H, Leonhardt S, Gorkow C, Wuttke W. In vitro prolactin but not LH and FSH release is inhibited by compounds in extracts of Agnus castus: direct evidence for a dopaminergic principle by the dopamine receptor assay. Exp Clin Endocrinol. 1994;102(6):448–54. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier B, Berger D, Hoberg E, Sticher O, Schaffner W. Pharmacological activities of Vitex agnus-castus extracts in vitro. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(5):373–81. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wuttke W, Jarry H, Christoffel V, Spengler B, Seidlova-Wuttke D. Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus)--pharmacology and clinical indications. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(4):348–57. doi: 10.1078/094471103322004866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webster DE, Lu J, Chen SN, Farnsworth NR, Wang ZJ. Activation of the mu-opiate receptor by Vitex agnus-castus methanol extracts: implication for its use in PMS. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;106(2):216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upton R. Chaste Tree Fruit, Vitex agnus-castus: Standards of Analysis, Quality Control, and Therapeutics. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia; Santa Cruz, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaksch F, Wang M, Roman M. Handbook of Analytical Methods for Dietary Supplements. American Pharmacists Association; Washington, D.C.: 2005. Chaste Tree; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malatynska E, Wang Y, Knapp RJ, Santoro G, Li X, Waite S, et al. Human delta opioid receptor: a stable cell line for functional studies of opioids. Neuroreport. 1995;6(4):613–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Li JG, Chen C, Zhang F, Liu-Chen LY. Molecular basis of differences in (−)(trans)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-(1-pyrrolidiny)-cyclohexyl]benzeneac etamide-induced desensitization and phosphorylation between human and rat kappa-opioid receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61(1):73–84. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Gardell LR, Ossipov MH, Vanderah TW, Brennan MB, Hochgeschwender U, et al. Pronociceptive actions of dynorphin maintain chronic neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2001;21(5):1779–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01779.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22(23):3099–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhyu MR, Lu J, Webster DE, Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR, Wang ZJ. Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa, Cimicifuga racemosa) behaves as a mixed competitive ligand and partial agonist at the human mu opiate receptor. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(26):9852–7. doi: 10.1021/jf062808u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mortola JF. Premenstrual syndrome--pathophysiologic considerations. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(4):256–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuong CJ, Coulam CB, Kao PC, Bergstralh EJ, Go VL. Neuropeptide levels in premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1985;44(6):760–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)49034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chuong CJ, Hsi BP. Effect of naloxone on luteinizing hormone secretion in premenstrual syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1994;61(6):1039–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tulenheimo A, Laatikainen T, Salminen K. Plasma beta-endorphin immunoreactivity in premenstrual tension. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;94(1):26–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannini AJ, Martin DM, Turner CE. Beta-endorphin decline in late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20(3):279–84. doi: 10.2190/JRQJ-XTX9-CQPF-HD70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giannini AJ, Sullivan B, Sarachene J, Loiselle RH. Clonidine in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a subgroup study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49(2):62–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster DE, Dentali S, Farnsworth NF, Wang ZJ. Chaste tree and premenstrual syndrome. In: Mischoulon D, Rosenbaum JE, editors. Natural Medications for Psychiatric Disorders: Considering the Alternatives. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milewicz A, Jedrzejak J. Premenstrual syndrome: From etiology to treatment. Maturitas. 2006;55S:S47–S54. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samochowiec L, Glaesmer R, Samochowiec J. Einfluss von Monchspfeffer auf die Konzentration von beta-Endorphine im Serum weiblicher Ratten. Aerztezeitschrift fur Naturheilverfahren. 1998;39:213–215. Summarized in Schmid, D, Zulli, F. Role of Bets-Endorphin in the Skin. SOFW-Journal 2005;131:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruni JF, Van Vugt D, Marshall S, Meites J. Effects of naloxone, morphine and methionine enkephalin on serum prolactin, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone and growth hormone. Life Sci. 1977;21(3):461–6. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinoshita F, Nakai Y, Katakami H, Imura H. Suppressive effect of dynorphin-(1-13) on luteinizing hormone release in conscious castrated rats. Life Sci. 1982;30(22):1915–9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slizgi GR, Ludens JH. Studies on the nature and mechanism of the diuretic activity of the opioid analgesic ethylketocyclazocine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;220(3):585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingkaninan K, von Frijtag Drabbe Kunzel JK, AP IJ, Verpoorte R. Interference of linoleic acid fraction in some receptor binding assays. J Nat Prod. 1999;62(6):912–4. doi: 10.1021/np9805490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balunas MJ, Su B, Landini S, Brueggemeier RW, Kinghorn AD. Interference by naturally occurring fatty acids in a noncellular enzyme-based aromatase bioassay. J Nat Prod. 2006;69(4):700–3. doi: 10.1021/np050513p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoberg E, Meier B, Sticher O. Quantitative high performance liquid chromatographic analysis of diterpenoids in agni-casti fructus. Planta Med. 2000;66(4):352–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katavic PL, Lamb K, Navarro H, Prisinzano TE. Flavonoids as opioid receptor ligands: identification and preliminary structure-activity relationships. J Nat Prod. 2007;70(8):1278–82. doi: 10.1021/np070194x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]