Abstract

A computer-administered interview is described that may be useful for identifying and tracking symptoms and assessing treatment outcome. The Symptoms of Schizophrenia (SOS) Inventory is a 30-item self-report instrument designed to be used with patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. It is administered and scored on a personal computer and typically is completed in 3 to 5 minutes. The objective of this study was to examine the validity and reliability of the Symptoms of Schizophrenia (SOS) Inventory. The design of the study was a retrospective chart review. The setting of the study was the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center inpatient wards and outpatient psychiatric clinics. Participants included 138 veterans with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Measurements were based on scores from the SOS Inventory and Colorado Symptom Index (CSI). There were reliable differences between inpatients and outpatients (t=3.56, p<0.001), and it was found to correlate (r=0.84, n=44, p<0.05) with the CSI. The conclusion is that the SOS Inventory is an efficient, low-cost method of tracking symptom distress in patients with schizophrenia.

Introduction

One of the most difficult but important components of the treatment of psychosis is the monitoring of symptoms in order to measure treatment efficacy and track the course of the illness. Patients with psychotic disorders require frequent monitoring of symptoms if serious relapse is to be prevented. Even with medication adherence, the relapse rate is considerable, which indicates that environmental variables have a great contribution to symptom exacerbation and eventual relapse. Weiden and Olfson1 found the monthly relapse rate to be 3.5 percent per month for patients on optimal medication dose and 11 percent per month for patients who are not adherent with medication. In a study of 12,440 Medicare enrollees with schizophrenia, it was found that the average (±SD) number of clinic visits per year was 7.9 (±21). Individual therapy visits averaged only five (±14) per year.2 That is, on average, contact with a clinician occurred approximately every seven weeks and individual therapy occurred once every 10.4 weeks but with great variation. It is common for such follow-up appointments to be 20 minutes or less in a busy mental health clinic. This is not conducive to good care because monitoring the symptom status of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder usually requires considerable time and well-trained personnel. Many mental health practitioners are being confronted with demands to see more patients, less often, for less time. There are no clear guidelines regarding the standard of care that specifies the frequency for visits for this population of seriously mentally ill patients.

The best accepted outcome measures of schizophrenia treatment are the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), which was derived from the BPRS.3,4 However, unlike in many areas of medicine, the measures found in the research literature in psychiatry, and especially in schizophrenia, are ill-suited for routine clinical practice.5 These are labor-intensive, requiring much more time than can be devoted to routine visits in busy clinical practices (30 to 40 minutes). Although research rating scales may have significant clinical value if it they are routinely employed, they are impractical for most treatment settings because they require trained raters.5

In real-world clinical practice, self-report and professional observation, albeit for a very brief time during the office visit, are the primary sources of data in routine assessment. Many persons with severe mental illness live alone and do not benefit from symptom monitoring by family members. It is clear that early warning signs may arise rapidly before remedial treatment can be initiated and relapse may result. Evidence suggests that a relapse of schizophrenia is preceded by psychotic and non-psychotic behavioral and phenomenological changes.6–8 Herz and Melville examined 29 symptoms as early indications of relapse in 80 stable outpatients and found that the most frequently reported symptoms by patients were “feeling tense and nervous” (71%), “depression” (64%), and “trouble concentrating” (62%).9

Birchwood, et al.,10 developed an Early Signs Scale (ESS) that was administered every two weeks and predicted relapse/nonrelapse with an overall accuracy of 79 percent. Elevated scores on measures from the interview, above the criterion score for relapse, all appeared within four weeks prior to relapse. Behavioral changes were apparent between one and two weeks before relapse. These observations support the idea that measurement of symptoms should be done more frequently than is done in most outpatient settings. Birchwood, et al., also administered an objective rating scale, the Psychiatric Assessment Scale (PAS), at monthly intervals.10,11 They found PAS ratings changes were not observed prior to clinical relapse. However, the sample was small (19 patients), and an unspecified clinical interview was used. Jorgensen, using Birchwood's scale along with the General Psychopathology Scale of the PANSS, found Birchwood's symptom report measure predicted relapse.12 In a study of 60 subjects assessed every two weeks over six months, he detected 81 percent of the relapses (sensitivity=0.74; specificity=0.79). The PANSS added only marginally to the predictive validity, suggesting that the patient's subjective report is far more important. The temporal relationship found was that 63 percent of relapses were predicted four weeks prior to relapse, and 74 percent within two weeks of relapse. This finding further supports the need for frequent symptom monitoring.

This paper describes the integration of computer technology with a self-report assessment of symptoms for persons with schizophrenia. The resulting instrument, The Symptoms of Schizophrenia (SOS) Inventory, is not intended as a diagnostic test, but as a tool to monitor important symptoms in persons diagnosed with schizophrenic illnesses. It differs from the available psychiatric rating scales used in psychopharmacology research (BPRS, PANSS), general psychiatric populations (Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-32), or instruments to identify the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms (Colorado Symptom Index, [CSI]).13–17 The SOS requires patients to indicate the level of distress the symptom causes. The instrument provides a structure for the patients to report subjective distress over the course of treatment.

No self-report instrument can replace a thorough person-to-person clinical interview conducted by a highly trained professional. The SOS Inventory is a 30-item computer administered instrument on which patients report their symptoms distress in the past week. It is a rapid assessment of a broad range of symptoms commonly reported by patients with psychotic disorders. It provides quantification of symptom distress that may be useful for comparing results over the course of treatment and as a signal to clinicians for more intensive evaluation. The software generates a report for the clinician. It may be used as a guide for further evaluation, treatment monitoring, a therapeutic agenda, or modifications in pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions. The SOS requires less than five minutes to complete.

Self-report instruments are common in psychiatry, although not in schizophrenia. The CSI is a self-report measure of symptoms used primarily in populations of homeless persons to detect and measure psychiatric disturbance.18–20 This 15-item inventory inquires about frequency of a number of commonly experienced psychiatric symptoms during the previous month. It was chosen as an appropriate instrument to compare to the SOS in this study. Conrad, et al., compared a modified CSI (MCSI) with two other measures of psychological symptomatology or distress, the BSI, and the BPRS.17 In a study of 1,381 persons, they found that the CSI performed similarly to the other measures. However, the CSI has not been studied for routine monitoring of clinical state for individuals. The SOS differs from many other measures and rating scales insofar as it assesses symptom distress rather than presence or frequency of symptoms. It requires a simpler response than the CSI, which requires the patient to rate how often something happened in the past month. The SOS requires a rating of symptom distress within the briefer, one-week time frame. The range of symptoms assessed by the SOS is broader than the CSI, including items of low motivation, somatic concerns, sleeping problems, attitudes about taking medication, and difficulty with verbal expression.

There has been an interest in using computers as an aide in interviewing patients for nearly 40 years. Slack, et al.,21 published a report of a computerized medical history. Greist22 described a computer interview for suicide risk. Carr, et al.,23 described the use of microcomputer to take a psychiatric history of patients admitted to an inpatient ward. Patient reactions to computer interviews have been quite favorable.24 Furthermore, computer versions of existing instruments, such as structured diagnostic interviews and paper-and-pencil psychological tests, have shown they yield essentially the same result.25,26

Description of the Instrument

The 30 items on the SOS Inventory are presented in the Appendix. Items were developed from those typically found in clinical symptom interviews, but were phrased so that they reflected the patient's personal experience of distress. Most of the items would be routinely addressed in a patient visit of 30 minutes or longer. Responses are made on a 5-point Likert scale. Each item appears on the screen as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample of appearance of questions on computer screen

The italicized first line and the 5-point scale remain the same across all items. The second line changes and appears in yellow on the computer screen. The patient enters his/her answer on the computer keyboard and the next item immediately appears on the computer screen. All the items are phrased in the first person. The answers are scored on a 0 to 4 scale.

One item leads to a branch in the program. If the patient response is other than “not at all” to the item assessing suicidal ideation (e.g., #19, “I feel like killing myself”), the next question will be, “You have indicated you feel like killing yourself. If this is correct, press Y. If this is NOT correct, press N.” If the answer is not confirmed, the next inventory item is presented. If the answer is confirmed, the next items are: “Do you have a plan to kill yourself?” “Do you think you will kill yourself?” and “When do you intend to kill yourself? (Within one week? Between one week and one month? More than a month from now?).” The program then continues with the next item.

The responses are stored in a computer data file. A report is also stored in a separate file that can be copied and pasted into a computer-generated progress note. The summary report contains the total score (range 0–120), calculates and displays the mean score of the 30 items, number of items endorsed as distressing, and the average score of endorsed items. A line alerts the clinician whenever the suicidal item is endorsed, along with the answers to the branching items of intent, plan, and time frame. Items that are endorsed “moderately,” “a great deal,” and “extremely” are printed on the report and divided by response level. This serves as a potentially useful therapeutic agenda when the SOS inventory precedes a clinical visit.

Method

A clinical chart review was conducted of patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had taken the inventory, which identified 138 veterans from the mental health inpatient and outpatient clinics of the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center. The symptom inventories were given as part of routine clinical care. The patients were an average age of 45.6 (±9.7) years and predominantly white (70.2%) with 28.3 percent being African-American, and 1.5 percent Hispanic. Two patients were female (1.5%). Forty-four outpatients from this group also were administered a modified version of the CSI. The mean age of the CSI group was 45.4 (±9.8), 42 were male, 38 white, five African-American, and one Hispanic. The CSI data were gathered from a chart review of patients who were given these assessments as part of their routine clinical care. The patients were given the SOS and CSI within a few minutes of each other. The CSI was modified for computer administration to be more similar to administration of the SOS.

Results

The scale has high internal consistency. Cronbach's alpha for the entire sample was 0.95.27 The average score was 37.65 (±25.31), with a range of 0 to 106. Not surprisingly, this distribution is skewed with more patients reporting high than low levels of distress.

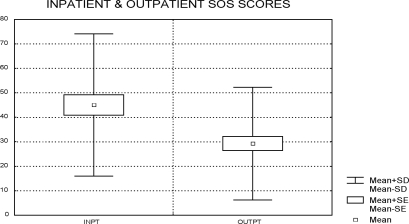

Validity of the SOS was evaluated in two ways. First, the scores of inpatients (n=55) and outpatients (n=77) were compared. It was hypothesized that inpatients would have more symptom distress than outpatients. Mean ages of the two groups were not significantly different (inpatient 45.1 [±8.2], outpatient 46.1 [±10.7], t=0.59, df=130, p=0.56). The inpatient group was 100-percent male, and the outpatient group was 97-percent male. These total scores were significantly different (inpatient mean=46.3 (±27.3); outpatient mean=30.5 (±23.4), t=3.56, df=129, p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Inpatient and outpatient SOS scores

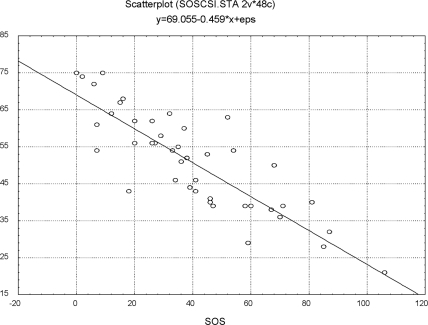

The second validity measure was the comparison of the SOS with the CSI. The Pearson Product-Moment Correlation of the CSI with the SOS was r=-0.84 (p<0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

SOS and CSI scores of 44 outpatients

Examination of the 30 items in the total sample revealed great variation in the frequency with which they were endorsed. While only 21.6 percent of the subjects responded “not at all” to “I feel weak and tired”, 74.1 percent responded “not at all” to “The medicine I take is harming me more than it is helping me.” Item mean scores on the 0 to 4 scale for the 138 patients ranged from 0.55 to 1.80. The item with the highest mean score was “I think it is dangerous to be among strangers or in crowds” (1.8±1.4). Some patients endorse many items with fairly low symptom distress, while others endorse only a few, but with very high distress scores. This variation supports reporting results to the clinician as both an overall mean score of all 30 items and as item scores for those endorsed above 0. Suicidal ideation was reported by 40 percent of the sample. Sixteen percent indicated it bothered them “a little bit,” 11 percent “moderately,” nine percent “a great deal,” and five percent “extremely.”

In order to give clinicians a way of seeing the syptoms more simply, the mean scores of scores of four clusters of symptoms—persecutory ideation, mood disturbance, cognitive problems, and somatic concerns—are also calculated. These symptom groups were rationally determined and are meant to be useful summaries but not independent factors. In fact, cluster scores were highly correlated and ranged from 0.62 to 0.78.

Discussion

The SOS is a low-cost method of accomplishing a number of important objectives. It provides clinicians with an efficient method for monitoring early warning signs of relapse, of measuring outcome of treatment interventions, and of establishing a record of the patient's progress. It gives patients who often have difficulty with expressive language a structured way to report their symptom distress. Repeated assessment provides quantification of symptom distress over the course of treatment. It has been demonstrated in this study to be easy to use by patients and helps provide a therapeutic agenda at appointments. It is useful with shorter visits because it helps cover information efficiently and serves as a catalyst for relevant discussion. This tool may be especially valuable in a psychiatric population that is often inarticulate, especially when appointments with clinicians are brief and/or infrequent. Some patients who have been asked to take this inventory have reported feeling more involved in their treatment and that their clinicians aare paying more attention to their concerns.

The SOS is not a diagnostic assessment tool, nor it is a measure of severity of symptoms. The SOS may best be seen as a repeatable tool for monitoring a patient's subjective state that may herald relapse, identify targets for intervention, or monitor outcomes over time. The 30 items in the SOS Inventory reflect many of the common complaints of persons with psychotic symptoms. Because the patient finds them distressing, elimination of the symptoms they identify may become a goal shared by the patient and clinician. For patients with common symptoms, such as persecutory ideation, auditory hallucinations, depressed mood, or cognitive problems, it provides a simple method to rate symptom distress over the course of treatment. It allows the clinician to document how the patient rates symptom-related distress. The SOS also asks about suicidal ideation and serves to document the responses. Suicidal ideation is often overlooked in patients with blunted affect, since they may not appear to be obviously depressed. This study found 39.8 percent endorsed suicidal ideation was bothersome, which compares well with a review that indicated 40 percent of persons with schizophrenia report suicidal thoughts, 20 to 40 percent make unsuccessful suicide attempts, and 9 to 13 percent end their lives by suicide.28

There are several reports of symptom inventories for use with the severely mentally ill. The Computerized Self-Assessment of Psychosis Severity Questionnaire (COSAPSQ) was an attempt to develop and validate a similar computerized self-report questionnaire.5 However, because it contained 61 multiple-choice questions, it required a mean time of 21.6 minutes to complete. This was considered too long to be practical in a clinical setting. However, it serves to demonstrate the utility of a computerized assessment tool.

Other tools similar to the SOS Inventory were not designed as self-report measures, but rather as brief interviews to be administered by clinicians. The Subjective Well-Being Under Neuroleptics (SWN) investigates differences between older and newer generation antipsychotic medications.29 The Subjective Deficit Syndrome Scale (SDSS) assesses symptoms of the pure defect syndrome.30 Hogan, Awad, and Eastwood developed a 30-item scale to determine adherence to medication.31 The Personal Evaluation of Transition in Treatment (PETiT) measures changes in response to medications, treatment adherence, and subtle changes in quality of life.32 Other inventories were designed as outcome measures, such as the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90) or (BASIS-32), or as a screening device, such as the CSI. There is considerable content overlap among all these instruments and the SOS. We chose to compare the SOS with the CSI because it was designed specifically to measure symptoms for persons with severe and persistent mental illness.

The SOS has the advantage of being quickly and easily administered and may be scored on a desktop or portable computer. It could be taken by patients routinely just prior to an appointment on site or between clinic visits to monitor symptom status and provide a record of the variation in symptom distress. Computer administration of mental health instruments is rapidly growing and has been found to have high acceptability by patients. Patients with schizophrenia have been able to use personal computers successfully.33,34 Kobak, et al.,35 note that computer-administered rating scales have been found to be reliable and valid, and that patient reaction has been positive. In numerous published studies of computer interviews compared with face-to-face interviews and paper-and-pencil tests, it has been found that there is either a preference for the computer version or no difference between the two.24 Computers offer a reliable, inexpensive, accessible, and time-efficient means of assessing psychiatric symptoms. We are in the process of evaluating the utility of a secure internet website that patients can access to take the SOS at any time they so desire. The patient's clinician receives email notification that results of a newly completed SOS Inventory are available to be viewed on the website.

There are no natural or physical units of measurement for the symptoms of psychopathology. The SOS, like many other psychological assessment and measurement tools, is not a precise tool. It is intended as an adjunct for clinicians who need to monitor and document patient outcome. It is not meant to be a substitute for a clinical interview or to be used as a stand-alone assessment tool. Physical medicine has long used measures such as heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and body weight as potential signals of disease. For example, when an abrupt change in weight occurs, it may signal a problem. However, except at extreme values, weight in itself may not be very informative. Similarly, it may be a change in SOS score is more informative than the absolute score. Variation in score is important to note. Just as blood pressure and heart rate may vary in response to transient events, so may the responses to symptom distress items. But change in vital signs may be a precursor to a more general and important change in a patient's condition. Similarly, changes in a SOS score may serve as an early warning signal of psychiatric change. Few, if any, clinically feasible methods exist to provide continuous monitoring of symptoms in the seriously mentally ill. Additionally, the SOS is both patient-friendly and inexpensive. Since it can be completed in less than five minutes, it imposes little time burden on patients, even with repeated administrations. Once the website is established, cost is negligible. Close symptom distress monitoring is desirable whenever medication changes are made with the intent of aborting or preventing relapse. The SOS Inventory could be completed as often as every few days or weekly in order to monitor and document treatment response.

Among the limitations of this study is that few female subjects were included because the sample was drawn from a veteran population. It would be useful to have a more representative sample, perhaps drawn from a community mental health center. A larger age range, especially a group of adolescents, would also be useful to examine. This may be particularly important since a study of the BASIS-32 indicated its utility might not be as high in that population.36 Another limitation is that the SOS was not compared to more than one scale. It would be useful to compare the SOS with the BASIS-32, PETiT, and BSI. In addition, it would be of great interest to compare this scale with scales that are completed by the providers of mental health services and the widely accepted PANSS rating scale. However, lack of agreement would not necessarily invalidate the self-report scale. The question of validating a subjective distress measure is inherently different from the validation of measures of other concepts. When the instrument asks how much a particular symptom bothers a patient, unless one believes he or she is purposely attempting to mislead, one must accept the report as a valid report of his or her distress. This instrument simply makes the collection of such data potentially more orderly and systematic.

APPENDIX. Symptoms of Schizophrenia (SOS) Inventory items

During the past week, how much have you been bothered by the thought or problem that:

|

References

- 1.Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1995;21(3):419–29. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon L, Lyles A, Smith C, Hoch JS, et al. Use and costs of ambulatory care services among Medicare enrollees with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(6):786–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern RG, Fudge R, Sison CE, et al. Computerized self-assessment of psychosis severity questionnaire [COSAPSQ] in schizophrenia: Preliminary results. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998;34(1):9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serper MR, Davidson M, Harvey PD. Attentional predictors of clinical change during neuroleptic treatment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1994;13(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestor PG, Faux SF, McCarley RW, et al. Neuroleptics improve sustained attention in schizophrenia. A study using signal detection theory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991;4(2):145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Effects of neuroleptic medications on the cognition of patients with schizophrenia: A review of recent studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 9):62–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herz MI, Melville C. Relapse in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(7):801–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birchwood M, Smith J, Macmillan F, et al. Predicting relapse in schizophrenia: The development and implementation of an early signs monitoring system using patients and families as observers, a preliminary investigation. Psychol Med. 1989;19(3):649–56. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700024247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krawiecka M, Goldberg D, Vaughan M. A standardized psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1977;55(4):299–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorgensen P. Early signs of psychotic relapse in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:327–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derogatis LR. BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisen SV, Dill DL, Grob MC. Reliability and validity of a brief patient-report instrument for psychiatric outcome evaluation. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(3):242–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shern DL, Wilson NZ, Coen AS, et al. Client outcomes II: Longitudinal client data from the Colorado treatment outcome study. Milbank Q. 1994;72(1):123–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciarlo JA, Edwards DW, Kiresuk TJ, Brown TR. The Assessment of Client/Patient Outcome: Techniques for Use in Mental Health Programs. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1981. (Contract No. 278-80-0005) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad KJ, Yagelka JR, Matters MD, Rich AR, Williams V, Buchanan M. Reliability and validity of a modified Colorado Symptom Index in a national homeless sample. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3(3):141–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1011571531303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, DeForge BR, Postrado LT. A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(11):1038–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230076011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shern DL, Tsemberis S, Anthony W, et al. Serving street-dwelling individuals with psychiatric disabilities: Outcomes of a psychiatric rehabilitation clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1873–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slack HV, Hicks GP, Reed CP, VanCura LJ. A computer-based medical history system. N Engl J Med. 1966:194–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196601272740406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greist JH, Gustafson DH, Stauss FF, et al. A computer interview for suicide-risk prediction. Am J Psychiatry. 1973;130(12):1327–32. doi: 10.1176/ajp.130.12.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr AC, Ghosh A, Ancill RJ. Can a computer take a psychiatric history? Psychol Med. 1983;13(1):151–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobak KA. Patient Reactions to Computer Interviews. Madison, WI: Healthcare Technology Systems; 2001. (white paper) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erdman HP, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. A comparison of two computer-administered versions of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule. J Psychiatr Res. 1992;26(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90019-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozensky RH, Honor LF, Rasinski K, et al. Paper-and-pencil versus computer-administered MMPIs: A comparison of patients' attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior. 1986;2:111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meltzer HY. Suicide in schizophrenia: Risk factors and clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 3):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naber D, Moritz S, Lambert M, et al. Improvement of schizophrenic patients' subjective well-being under atypical antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Res. 2001;50(1-2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaeger J, Bitter I, Czobor P, Volavka J. The measurement of subjective experience in schizophrenia: The Subjective Deficit Syndrome Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31(3):216–26. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(90)90005-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics: Reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13(1):177–83. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voruganti LN, Awad AG. Personal evaluation of transitions in treatment (PETiT): A scale to measure subjective aspects of antipsychotic drug therapy in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;56(1-2):37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brieff R. Personal computers in psychiatric rehabilitation: A new approach to skills training. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45(3):257–60. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hermanutz M, Gestrich J. Computer-assisted attention training in schizophrenics. A comparative study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;240(45):282–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02189541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobak KA, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Katzelnick DJ. Computer-administered clinical rating scales. A review. Psychopharmacology. (Berl) 1996;127(4):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s002130050089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann FL, Capelli K, Mastrianni X. Measuring treatment outcome for adults and adolescents: reliability and validity of BASIS-32. J Ment Health Adm. 1997;24(3):316–31. doi: 10.1007/BF02832665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]