Abstract

Rationale

A critical event in the development of cardiac fibrosis is the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. The electrophysiological consequences of this phenotypic switch remain largely unknown.

Objective

Determine whether fibroblast activation following cardiac injury results in a distinct electrophysiological phenotype that enhances fibroblast-myocyte interactions.

Methods and Results

Neonatal rat myocyte monolayers were treated with media (CM) conditioned by fibroblasts isolated from normal (Fb) and infarcted (MI-Fb) hearts. Fb and MI-Fb were also plated on top of myocyte monolayers at three densities. Cultures were optically mapped after CM treatment or fibroblast plating to obtain conduction velocity (CV) and action potential duration (APD70). Intercellular communication and C×43 expression levels were assessed. Membrane properties of Fb and MI-Fb were evaluated using patch clamp techniques. MI-Fb CM treatment decreased CV (11.1%) compared to untreated myocyte (Myo) cultures. APD70 was reduced by MI-Fb CM treatment compared to Myo (9.4%) and Fb CM treatment (6.4%). In heterocellular cultures, MI-Fb CVs were different from Fb at all densities (+29.8%, −23.0%, and −16.7% at 200, 400 and 600 cells/mm2, respectively). APD70 was reduced (9.6%) in MI-Fb compared to Fb cultures at 200 cells/mm2. MI-Fb had more hyperpolarized resting membrane potentials and increased outward current densities. C×43 was elevated (134%) in MI-Fb compared to Fb. Intercellular coupling evaluated with gap-FRAP was higher between myocytes and MI-Fb compared to Fb.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate cardiac injury results in significant electrophysiological changes that enhance fibroblast-myocyte interactions and could contribute to the greater incidence of arrhythmias observed in fibrotic hearts.

Keywords: arrhythmia, Connexin43, electrophysiology, fibroblasts, optical mapping

INTRODUCTION

Many cardiovascular disorders including ischemic heart disease and heart failure are associated with extensive fibrosis. A critical event in the development of cardiac fibrosis is the transformation of fibroblasts into an active fibroblast phenotype or myofibroblast.1 Myofibroblasts, which are not present in healthy cardiac tissue with the exception of the valve leaflets, express vimentin, α–smooth muscle actin (α–SMA), collagen types I, III, IV and VIII, and have morphological and biochemical characteristics in between those of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells.2–4

The exact functional changes that occur as a consequence of cardiac fibroblast activation are beginning to be understood, however no information is available on the cellular electrophysiological effects of this process. The available in vitro electrophysiological studies investigating fibroblast membrane currents and intercellular coupling with myocytes have been performed using cells isolated from normal hearts and cultured to express myofibroblast markers. Fibroblasts grown under standard tissue culture conditions i.e., on a hard substrate and in the presence of serum begin expressing the myofibroblast marker α–SMA 24–48 hours after isolation.5–7 However, there is significant evidence in the literature indicating in vitro phenotypic changes due to culture conditions do not fully replicate the in vivo activation process. In this regard, cultured fibroblasts obtained from normal and fibrotic hearts exhibit differences in proliferation, migration, adhesion, collagen synthesis, response to cytokine treatment, and expression of α-SMA, collagen I and natriuretic peptide receptors.8–10 Given that the behavior of cardiac fibroblasts differs depending on whether they originate from normal or pathological tissue, it is important to examine how fibroblast activation manifests into potential arrhythmogenic consequences in the diseased heart.

Fibroblasts have been traditionally considered to affect cardiac electrophysiology indirectly, by creating collagenous septa that electrically isolates myocytes, producing slow meandering wavefronts.11 However, available in vitro and in vivo evidence suggests gap junctional coupling between fibroblasts and myocytes in the heart is a distinct possibility.7, 12–21 Fibroblasts act as current sinks and impose an electrical load when electrically coupled to myocytes. In addition, the resting membrane potential of fibroblasts has been shown to be more positive relative to myocytes18 and may become more hyperpolarized with activation.22 When coupled to myocytes, differences in fibroblast membrane conductance could influence myocyte resting membrane potential (RMP) and sodium current availability. Modeling and experimental studies have suggested increased fibroblast-myocyte coupling leads to changes in action potential duration (APD), electrotonic depression of myocytes, arrhythmogenic excitability gradients, altered conduction and unidirectional block.7, 21, 23–29

The purpose of this study was to investigate functional changes in fibroblast-myocyte interactions in response to cardiac injury. Our findings demonstrate myocardial infarction triggers important changes in the electrical phenotype of fibroblasts that enhance fibroblast-myocyte interactions and could contribute to the greater incidence of arrhythmias observed in fibrotic hearts. These findings may lead to the development of new anti-arrhythmic therapeutic approaches targeting the fibroblast activation process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A detailed description of materials and methods used in this study is included in the online Supplemental Material. All procedures complied with the standards for the care and use of animal subjects as stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996), and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the New York University School of Medicine.

Myocyte isolation and culture

Ventricular myocytes from neonatal (0–2 day old) Wistar Hannover rats were isolated and cultured as described previously.30 Myocytes were plated at a density of 1.8×103 cells/mm2 on collagen treated Petri dishes for optical mapping experiments. Myocytes were plated at lower densities for immunocytochemistry and gap fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (gap-FRAP) experiments. Confluent myocyte monolayers were treated with fibroblast conditioned media (CM) or coated with fibroblasts 16–20 hours before optical mapping experiments as described below. Cells were optically mapped 4 days after isolation.

Myocardial infarction model

Myocardial infarctions (MI) were produced in male Wistar Hannover rats (Charles River Laboratories) weighing 150–300 g by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) as described previously.31 Cells were isolated from the infarcted hearts 7–8 days after the surgical procedure. This time point was selected based on previous studies that showed cellular phenotypic changes associated with fibroblast activation are elevated 7 days after infarction.32–35 Only hearts with visible transmural infarcts were included in the study.

Fibroblast isolation

Cardiac fibroblasts were isolated from the whole ventricles of operated (MI-Fb) and age-matched normal (Fb) rats using a previously described protocol.36 The cells used in all experiments were restricted to passages 1–3 or a month after the isolation date and had already undergone the characteristic in vitro phenotypic changes due to culture conditions. In addition to cultured fibroblasts, freshly isolated Fb and MI-Fb were also used for immunoblots. The purity of fibroblast cultures was confirmed by microscopic inspection of cellular morphology and immunostaining using anti-vimentin, anti-α-SMA, anti-desmin and anti-von Willebrand factor antibodies.

Conditioned media and fibroblast coating

Fb and MI-Fb were trypsinized and plated in 60 mm Petri dishes at a density of 200 cells/mm2 using 4 mL of 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) medium with 0.1 mmol/L bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). After 16–20 hours, the media were collected and used undiluted as conditioned media (Fb CM and MI-Fb CM, respectively). Confluent myocyte monolayers were coated with fibroblasts 3 days after isolation. Fibroblasts were trypsinized and resuspended in 5% FBS medium with BrdU. Live (trypan blue negative) cells were counted and plated on top of confluent myocyte monolayers at densities of 200, 400 and 600 cells/mm2 16–20 hours before the optical mapping experiments. The number of cells used to generate the CM was the same as the number of fibroblasts plated on top of myocyte monolayers at the 200 cells/mm2 density. Untreated homocellular myocyte monolayers (Myo) were used as control.

Optical mapping

Conduction velocity (CV) and action potential duration at 70% repolarization (APD70) of the cultures were assessed using high resolution optical mapping. Mapping was performed on an upright microscope (Olympus B×51WI) equipped with a reflected light fluorescence attachment, a 100W mercury arc lamp and a CMOS camera (MiCAM ULTIMA, SciMedia). Recordings were made at 250 frames/s with 14 bit resolution from a 100×100 pixel array, providing a spatial resolution of 81.6 μm at 2.5× magnification. Cells were stained with the photosensitive dye di-8-ANEPPS (135 μmol/L; Invitrogen) and maintained in recording solution (1% FBS HBSS at 37 °C, pH 7.4) throughout the mapping procedure. Experiments were performed in the absence of motion reduction techniques. Cells were stimulated at a basic cycle length of 400 ms using bipolar electrodes (250 μm diameter, 800 μm separation; FHC Inc.). CV and APD calculations for individual pixels were performed as described previously.37, 38

Whole cell voltage clamp

Membrane currents and reversal potentials were recorded from cultured Fb and MI-Fb using whole cell voltage clamp. Ionic currents were recorded via a patch clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B, Axon Instruments) interfaced to a Digidata acquisition system controlled by Clampex version 8 software (Axon Instruments). Patch electrodes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mmol/L): 12 NaCl, 20 KCl, 110 K-aspartate, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 2 K2ATP, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.2. The extracellular solution was a modified Tyrode’s solution containing (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH 7.4. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Cell capacitance was measured by integrating the area under the capacitive transient elicited by 5 mV depolarizing steps from a holding potential of 0 mV. Series resistance and whole cell capacitance were electronically compensated. Whole cell I–V relationships were determined from a holding potential of −50 mV with a protocol consisting of 1.5 s voltage steps applied from −130 to 30 mV in 10 mV increments. The amplitudes of whole cell membrane currents at the end of the voltage steps were normalized to cell capacitance and reported as pA/pF. Data were analyzed using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments) and Origin 7 (OriginLab).

Immunoblotting and immunocytochemistry

Western blotting was used to determine differences in Cx43 expression between freshly isolated and cultured Fb and MI-Fb. Differences in α–SMA expression between cultured Fb and MI-Fb were also assessed. Freshly isolated samples were obtained less than 24 hours after the initial plating. Cells were lyzed in Laemmli sample buffer supplemented with 50 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1 mmol/L PMSF and 1× complete protease inhibitors (Roche).39 Protein concentration was determined using the Lowry assay run in triplicate. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Blots were blocked followed by incubation with primary antibodies directed against Cx43 (Sigma), α–SMA (Sigma) and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Primary antibodies were visualized using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and chemiluminiscent processing. Densitometry measurements of protein levels were performed using the Photoshop software package. Cx43 and α–SMA band intensities were normalized to the relative intensity of the corresponding GAPDH band for each cultured sample. For freshly isolated samples, the absolute intensity of Cx43 bands was quantified for equal amounts of total protein loaded (20 μg).

Immunocytochemistry was used to assess the purity of the fibroblast cultures and to determine the expression and distribution of Cx43 in heterocellular cultures. Cells were fixed in 3% formalin and blocked with a solution of 2% normal goat serum and 1% TritonX100 at room temperature. The cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody, rinsed with 1% TritonX100 and incubated with the secondary antibody at room temperature. The primary antibodies used include anti-α–SMA (Sigma), anti-vimentin (Sigma), anti-desmin (Sigma), anti-von Willebrand factor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-Cx43 (Invitrogen).

Gap-FRAP

Functional intercellular coupling between myocytes and Fb or MI-Fb was evaluated using the gap-FRAP technique. Freshly isolated myocytes were stained with DiI (Invitrogen) and plated at a low density on top of confluent Fb and MI-Fb monolayers in 5% FBS medium supplemented with BrdU. A plating fibroblast/myocyte ratio of approximately 30:1 was used for all gap-FRAP experiments. Cells were incubated for 24–48 hours after myocyte plating, stained with calcein AM (5 μmol/L, 37 °C, 15 min; Invitrogen), washed and incubated in recording solution for 15 min. The gap junction channel blocker carbenoxolone (200 μmol/L; Sigma) was used in some cultures to block gap junction communication. Single myocytes that were not in direct contact with other myocytes were bleached in a confocal microscope (Leica SP5) using an argon laser source at 488 nm. The recovery of the 500–550 nm fluorescence signal was measured with a 63x objective at varying time intervals for up to 30 min. The signal was fitted to a single exponential function using the Levenberg–Marquardt non-linear least squares algorithm. The permeability constant (k) of the fluorescence recovery was calculated as the inverse of the time constant (τ).

Statistical analysis

Values are reported and plotted as mean±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one or two-way ANOVA with replication as appropriate when comparing several groups followed by two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used for comparisons of two groups. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05. The Bonferroni correction was used when multiple statistical tests were performed using the same data set.

RESULTS

Fb and MI-Fb isolation

Fibroblasts were isolated from the whole ventricles of normal and infarcted hearts 7–8 days after LAD ligation surgery. All of the LAD ligated hearts that were used for fibroblast isolation showed transmural lesions and left ventricular wall thinning. The purity of the fibroblast cultures was assessed by immunocytochemistry. See the online Supplemental Material for details.

Conditioned media treatment

Confluent neonatal rat myocyte monolayers were treated with Fb CM or MI-Fb CM for 16–20 hours prior to performing the high resolution optical mapping studies. Figure 1 shows the CV changes induced by the CM. Treatment with Fb CM (16.6±0.4 cm/s) did not significantly change CV compared to Myo (17.8±0.4 cm/s) cultures. On the other hand, MI-Fb CM treatment decreased CV by 11.1% compared to Myo cultures (15.8±0.4 cm/s; p=0.0003). There were no significant differences in CV values between the myocyte cultures treated with Fb CM and MI-Fb CM. Figure 2 shows the APD changes induced by CM treatment. Fb CM (153.4±2.7 ms) did not significantly change APD70 values compared to Myo cultures (158.6±2.5 ms). APD70 was reduced by 9.4% with MI-Fb CM treatment (143.6±1.7 ms; p=3.16E-6) compared to Myo. Treatment with MI-Fb CM also reduced APD70 by 6.4% compared to Fb CM treatment (p=0.004). These data suggest that CM from MI-Fb have the potential to significantly reduce CV and abbreviate APD compared to Myo cultures. In addition, MI-Fb CM significantly shortens APD compared to Fb CM treatment.

Figure 1. Conduction properties of myocyte monolayers treated with media conditioned by fibroblasts from normal (Fb CM) and infarcted (MI-Fb CM) hearts.

A, Representative activation map from an untreated myocyte monolayer (Myo). Scale bar is 1 mm, lines are 10 ms isochrones. B–C, Representative activation maps from myocyte monolayers treated with Fb CM and MI-Fb CM, respectively. D, Average conduction velocity (CV) for Myo (n=66), Fb CM (n=75) and MI-Fb CM (n=63) treated monolayers.

Figure 2. Action potential duration (APD) of myocyte monolayers treated with media conditioned by fibroblasts from normal (Fb CM) and infarcted (MI-Fb CM) hearts.

A, Superimposed representative optical action potentials recorded from an untreated myocyte monolayer (Myo) and myocyte monolayers treated with Fb CM and MI-Fb CM. B, Average APD70 for Myo (n=66), Fb CM (n=75) and MI-Fb CM (n=63) treated monolayers.

Heterocellular cultures

Fb or MI-Fb were plated on top of confluent myocyte monolayers at three different densities, 200, 400 and 600 cell/mm2, and the cultures were optically mapped 16–20 hours later. The plating densities correspond to fibroblast to myocyte ratios of 1:9, 1:4.5 and 1:3 respectively, and were determined from counts of myocytes/mm2 in confluent myocyte cultures and fibroblast plating densities. Figure 3 shows representative activation maps and average CV of heterocellular cultures with Fb and MI-Fb. At the lowest fibroblast plating density, Fb did not affect CV values (17.0±0.5 cm/s) compared to Myo cultures (see Myo, Figure 1D). MI-Fb (22.0±0.6 cm/s) increased CV by 23.7% compared to Myo cultures (p=4.49E-9). In addition, CV values from Fb heterocellular cultures were not significantly different from homocellular myocyte cultures treated with Fb CM. On the other hand, CV values from MI-Fb heterocellular cultures were significantly different from the values obtained from MI-Fb CM treatment (p=9.52E-15). At higher fibroblast densities, average CV values were decreased with Fb and MI-Fb compared to Myo (Fb: 13.8±0.4 and 11.4±0.3 cm/s; MI-Fb: 10.6±0.3 and 9.5±0.3 cm/s, at 400 and 600 cells/mm2, respectively). MI-Fb CVs were different from Fb at all densities (+29.8%, p=1.95E-8; −23.0%, p=2.42E-9 and −16.7%, p=0.0002 for 200, 400 and 600 cells/mm2, respectively). In addition, there was a density dependent change of CV for Fb (p=9.07E-17) and MI-Fb (p=2.55E-42).

Figure 3. Conduction properties of heterocellular cultures of myocytes and fibroblasts from normal (Fb) and infarcted (MI-Fb) hearts.

A–C, Representative activation maps from heterocellular cultures of myocytes and Fb plated on top. Fb were plated at 200, 400 and 600 cells/mm2, respectively. Scale bar is 1 mm, lines are 10 ms isochrones. D–F, Representative activation maps from heterocellular cultures of myocytes and MI-Fb plated on top. MI-Fb were plated at 200, 400 and 600 cells/mm2, respectively. G, Average conduction velocity (CV) of the heterocellular cultures for different fibroblast plating densities. Dotted line corresponds to average CV of homocellular myocyte monolayers (Myo). p values correspond to significant differences between Fb and MI-Fb at the same density. n = 35, 68, 65 for Fb; 36, 46, 28 for MI-Fb.

Figure 4 shows representative optical action potentials and average APD70 values of heterocellular cultures with Fb and MI-Fb. At the lowest plating density, APD70 values were shorter by 8.6% in heterocellular Fb (145.0±3.9 ms; p=0.003) and 17.3% in MI-Fb cultures (131.1±3.7 ms; p=7.58E-9) compared to Myo. In addition, average APD70 values in heterocellular MI-Fb cultures were decreased by 9.6% compared to heterocellular Fb cultures (p=0.01). Heterocellular MI-Fb APD70 values were shorter compared to MI-Fb CM treatment (p=0.0008) while heterocellular Fb cultures were not significantly different from Fb CM treated cultures. Since the number of fibroblasts used to generate the fibroblast conditioned media was the same as the number of fibroblasts plated on top of myocytes at this density, the consistent differences between CV and APD70 values in heterocellular MI-Fb cultures and those obtained from treatment with MI-Fb CM suggest MI-Fb modulate myocyte electrophysiology through a combination of paracrine factors and direct mechanisms which could include increases in intercellular coupling and changes in membrane electrophysiology. At higher densities, APD70 was longer for Fb compared to Myo (171.0±2.1, p=0.0002 and 165.7±1.8 ms, p=0.02 at 400 and 600 cells/mm2, respectively). MI-Fb values were prolonged at 400 cells/mm2 (175.8±2.7 ms, p=1.27E-5) compared to Myo. Average APD70 values were not significantly different between heterocellular Fb and MI-Fb cultures at 400 or 600 cells/mm2. These data demonstrate cardiac injury enhances the ability of fibroblasts to abbreviate APD at when present at low cell numbers and modulate conduction properties over a wide range of densities.

Figure 4. Action potential duration (APD) of heterocellular cultures of myocytes and fibroblasts from normal (Fb) and infarcted (MI-Fb) hearts.

A, Superimposed representative optical action potentials recorded from heterocellular cultures with Fb and MIFb plated on top at 200, 400 and 600 cells/mm2. Scale bar is 100 ms. B, Average APD70 of the heterocellular cultures for different fibroblast plating densities. Dotted line corresponds to average APD70 of homocellular myocyte monolayers (Myo). p value corresponds to significant difference between Fb and MI-Fb at the same density. n = 35, 68, 65 for Fb; 36, 46, 28 for MI-Fb.

Previous studies have shown differences in fibroblast proliferation rates depending on whether the cells were obtained from the infarct or remote regions of LAD ligated hearts.9 Proliferation rates of Fb and MI-Fb cultured in standard medium supplemented with 5% FBS and BrdU were not significantly different after a 16–20 hour culture period (Fb 1.0±0.11 and MI-Fb 1.01±0.08 A.U.; n=12). Therefore differences between heterocellular cultures with Fb and MI-Fb can not be attributed to increased fibroblast densities.

Whole cell voltage clamp

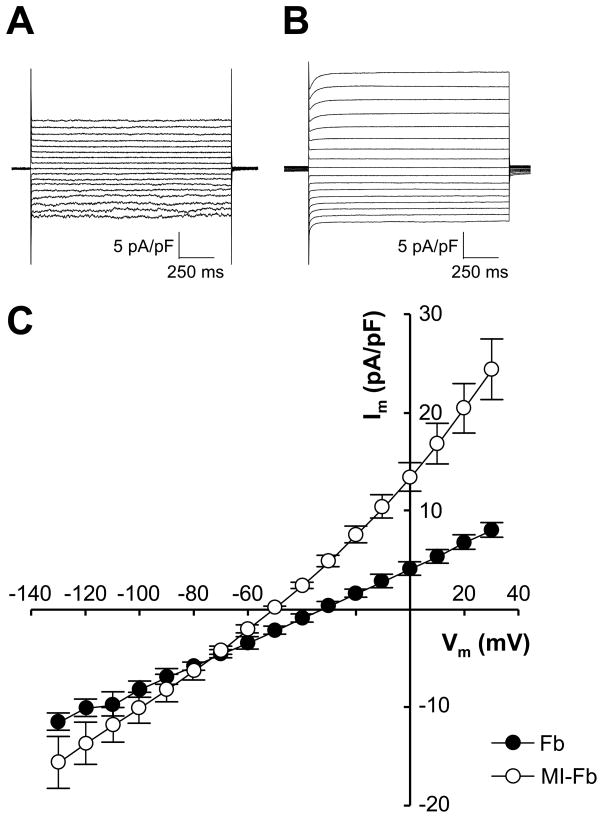

Whole cell patch clamp experiments were performed to determine cell capacitance, reversal potential and membrane current density of cultured Fb and MI-Fb. The average cell capacitance was not significantly different between Fb (77.6±19.4 pF, n=5) and MI-Fb (77.4±19.4 pF, n=7). The average reversal potential of MI-Fb (−51.0±1.5 mV, n=7) was more hyperpolarized compared to Fb (−32.0±3.5 mV, n=5; p=0.0002). A representative family of currents from individual fibroblasts and average current densities are shown in Figure 5. Measurement of membrane current densities yielded relatively linear I–V relationships for voltages ranging from −130 to 30 mV. Outward current densities were greater (p<0.05) in MI-Fb compared to Fb for voltages greater than −70 mV. These data demonstrate that the reversal potential and membrane currents and are altered in MI-Fb.

Figure 5. Membrane currents recorded from fibroblasts isolated from normal (Fb) and infarcted (MI-Fb) hearts.

A–B, Representative currents recorded with whole cell patch clamp techniques from a single Fb and MI-Fb, respectively. Membrane voltage (Vm) was clamped at −50 mV and stepped from −130 to 30 mV in 10 mV increments. C, Average membrane current density (Im) recorded from Fb (n=5) and MI-Fb (n=7). p<0.05 for MI-Fb compared to Fb for Vm greater than −70 mV.

Connexin expression and functional coupling

Cx43 distribution and expression levels i n F b a n d MI-Fb were assessed with immunocytochemistry and Western blotting techniques. Figure 6A–B shows immunostaining of Cx43 in heterocellular cultures of myocytes and Fb or MI-Fb. Cx43 signal was observed at cell contact areas between neighboring myocytes and fibroblasts in both Fb and MI-Fb cultures. Figure 6C shows a Western blot demonstrating an increase in Cx43 expression levels in cultured MI-Fb compared to Fb. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Figure 6D shows an immunoblot indicating increased Cx43 protein levels in freshly isolated MI-Fb compared to Fb. Quantifications of immunoblots are shown in Figure 6E–F. These data indicate that Cx43 expression levels are elevated in cultured (134%, p=0.008) and freshly isolated (35%, p=0.03) fibroblasts in response to cardiac injury.

Figure 6. Cx43 expression in fibroblasts isolated from normal (Fb) and infarcted (MIFb) hearts.

A–B, Immunostaining of Cx43 in heterocellular cultures of myocytes (m) and Fb or MI-Fb (f), respectively. Green is α-SMA, red is Cx43, arrowheads indicate Cx43 staining at cell contact areas. Scale bar is 20 μm. C, Representative immunoblot showing expression of Cx43 in cultured Fb and MI-Fb. GAPDH was used as a loading control. D, Representative immunoblot showing expression of Cx43 in freshly isolated Fb and MI-Fb. E, Quantification of immunoblots from a total of 6 Fb and 6 MI-Fb cultured samples. Cx43 expression levels were normalized to Fb. F, Quantification of immunoblots from a total of 10 Fb and 10 MI-Fb freshly isolated samples. Cx43 expression levels were normalized to Fb

Intercellular coupling between myocytes and fibroblasts was evaluated with gap-FRAP. For these experiments, myocytes were plated at a low density on top of confluent fibroblast monolayers. This plating configuration was selected to allow for bleaching and recording of fluorescence recovery in the myocytes. Figure 7A–F shows micrographs of calcein AM stained Fb and MI-Fb monolayers with myocytes plated on top. Single myocytes that were not in direct contact with other myocytes were bleached and the recovery of the fluorescence signal was tracked for up to 30 min. Figure 7G–H shows average recovery curves and permeability constants for myocytes plated on Fb and MI-Fb monolayers. The fluorescence of myocytes recovered after bleaching regardless of the fibroblast source; however the recovery was 81% faster when myocytes were plated on top of MI-Fb (0.56±0.07 min−1) compared to Fb (0.31±0.04 min−1, p=0.006). Addition of the gap junction uncoupler carbenoxolone decreased the permeability constant of myocytes plated onto Fb (0.06±0.04 min−1, p=0.0008) and MI-Fb (0.23±0.05 min−1, p=0.002), confirming the recovery of the fluorescence was mediated by gap junctions. The permeability constants of both groups recovered after washout. These functional data are consistent with the increase in Cx43 protein levels in MI-Fb and indicate intercellular coupling was significantly increased between myocytes and MI-Fb compared to Fb.

Figure 7. Intercellular coupling between myocytes and fibroblasts from normal (Fb) and infarcted (MI-Fb) hearts.

A, micrograph of an Fb monolayer with a myocyte plated on top. Myocyte is indicated by the dotted lines. Scale bar is 25 μm. B–C, heterocellular myocyte and Fb culture loaded with calcein-AM before and after myocyte photobleaching, respectively. Dotted line indicates the bleached area. D, Micrograph of an MI-Fb monolayer with a myocyte plated on top. E–F, heterocellular myocyte and MI-Fb culture loaded with calcein-AM before and after myocyte photobleaching. G, Average fluorescence recovery curves of myocytes plated on top of Fb and MI-Fb monolayers. H, Average permeability constants (k) from myocytes plated on top of Fb and MI-Fb monolayers under control conditions, with 200 μmol/L carbenoxolone (CBX) and after CBX washout. n = 20, 10 and 11 for Fb, n = 24, 14, and 13 for MI-Fb.

DISCUSSION

Fibroblasts play a major role in wound healing in response to many forms of cardiac injury. Previous studies have identified numerous phenotypic differences between fibroblasts isolated from healthy and diseased hearts. Squires et al.9 demonstrated proliferation rates of fibroblasts isolated from the infarct region were 182% higher compared those obtained from normal controls. Other investigators have shown fibroblasts isolated from normal and infarcted hearts have different natriuretic peptide receptor expression profiles and respond differently to cytokine treatment.10 Similar functional differences have also been observed in fibroblasts isolated from failing hearts.8 Finally, there is also evidence demonstrating differences in migration, adhesion properties, collagen synthesis, α-SMA expression and β1 integrin density.8–10 It is important to point out these differences have been shown to be maintained in culture through at least the first four passages. Although there is substantial evidence demonstrating important functional differences between fibroblasts isolated from normal and diseased hearts, the electrophysiological consequences of in vivo fibroblast activation have not been studied until now.

Electrical interactions between myocytes and fibroblasts were initially described in cells isolated from neonatal hearts.18 More recent studies have demonstrated similar interactions occur between isolated adult myocytes and fibroblasts.13 Both Cx43 and Cx45 have been found in contact areas between neighboring fibroblasts and myocytes in culture.7, 13, 18, 21 Gap junctional coupling between myocytes and fibroblasts in culture supports the electrical and mechanical synchronization of myocytes interconnected by fibroblasts.18 Experiments using optical mapping techniques have shown that fibroblasts serve as sinks for electrotonic current, thereby producing localized slow conduction and decreasing the maximum rate of change of the action potential in the surrounding myocytes.7, 19 This is the first study to demonstrate cardiac injury is associated with higher fibroblast Cx43 levels resulting in increased functional coupling between isolated myocytes and fibroblasts. The implications of these findings are that myofibroblasts have a significantly greater ability to modulate the electrophysiological substrate than fibroblasts.

Definitive proof of in vivo fibroblast-myocyte coupling in intact cardiac tissue has been difficult to obtain using standard electrophysiological techniques. However, empirical evidence suggests functional electrical coupling between fibroblasts and myocytes can occur.14, 15 In addition, it has been shown that ventricular myocytes and fibroblasts express Cx43 and Cx45.40 Cx43 has been shown to be localized at homocellular and heterocellular points of contact, while Cx45 is mainly present in fibroblasts and occasionally found between myocytes and fibroblasts. Research into in vivo fibroblast gap junction expression and coupling during pathological conditions has shown that fibroblasts in ventricular infarct scar tissue express Cx45 or Cx43 with spatially and temporally distinct patterns.17 Cx40 has not been identified in these cells. These data suggest that Cx45 expressing fibroblasts may be involved in electrical coupling between fibroblasts and myocytes during the acute remodeling process, while Cx43 expressing cells may perform this function at later stages. It is intriguing to speculate the Cx45 and Cx43 populations correspond to the fibroblast and myofibroblast phenotypes.

Fibroblasts can affect cardiac electrophysiology through a number of mechanisms including the release of chemical mediators, deposition of extracellular matrix and through direct electrical coupling with myocytes.41 The effects of chemical mediators have been studied by treating cultured myocytes with fibroblast conditioned media. LaFramboise et al., found that neonatal fibroblast chemical mediators affect the size, contractile capacity and phenotype plasticity of cardiac myocytes in culture.42 These factors include VEGF, GRO/KC, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, leptin, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor-α. Other studies have suggested the electrophysiological effects of fibroblast conditioned media treatment are minimal.43, 44 However, the methods used to condition the media are often unspecific with regard to seeding density and duration of treatment. A more recent systematic study of the effects of neonatal fibroblast conditioned media on myocyte electrophysiology demonstrated dose dependent effects on a variety of parameters including RMP, CV and APD.45 In the present study, treatment with media conditioned with fibroblasts isolated from normal hearts did not significantly affect CV or APD of myocyte monolayers. The lack of electrophysiological effects of conditioned media treatment could be due to a number of factors including the dose used, presence of serum or the fibroblast source (adult versus neonatal). On the other hand, treatment with conditioned media obtained from MI-Fb resulted in slower CVs and abbreviated APD compared to untreated myocyte cultures. These data demonstrate cardiac injury significantly alters the profile of paracrine factors released by fibroblasts which could potentially increase arrhythmogenesis in regions of the myocardium where myocytes and myofibroblasts are in close proximity such as the infarct border zone.

Plating fibroblasts on top of confluent myocyte monolayers also resulted in significant modulation of myocyte CV and APD. CV and APD modulation has been shown to be dependent on the plating configuration, seeding densities, fibroblast size, fibroblast RMP and coupling levels.7, 23, 24, 27, 29, 44 For the plating configuration used in this study, CV monotonically decreased in heterocellular cultures of myocytes and fibroblasts isolated from normal hearts with increasing fibroblast density. These data are consistent with several other studies using cultured neonatal fibroblasts at similar myocyte to fibroblast ratios.7, 20, 27 In heterocellular cultures of myocytes and fibroblasts isolated from infarcted hearts, CV increased at the lowest plating density compared to homocellular myocyte cultures. This increase in CV is due to partial depolarization of myocytes as a consequence of coupling to fibroblasts with a more positive reversal potential. A similar increase in CV was observed in heterocellular cultures of myocytes and neonatal fibroblasts; however this effect occurred at lower fibroblast plating densities. The difference in the density of fibroblasts required to increase CV is likely due to the more hyperpolarized reversal potential of fibroblasts isolated from infarcted hearts compared to those obtained from normal hearts. In heterocellular cultures with fibroblasts isolated from infarcted hearts, CV also monotonically decreased at higher plating densities. However, CV in these cultures was slower than similar cultures with fibroblasts from normal hearts.

In this study, APD modulation was shown to be dependent on the fibroblast density and source. At the lowest plating density, fibroblasts from infarcted hearts reduced APD compared to myocyte cultures. At higher densities, APD values were prolonged for both fibroblast sources compared to myocyte only cultures. Modeling studies have predicted that given sufficient levels of intercellular coupling and fibroblast numbers, increasing fibroblast density will prolong APD.27 At similar fibroblasts densities a more negative RMP is expected to shorten APD. At the lowest plating density, cultures with fibroblasts from infarcted hearts had shorter APD values compared to similar cultures with fibroblasts with normal hearts. These data suggest fibroblasts from infarcted hearts have a more negative RMP compared to fibroblasts from normal hearts. This is consistent with the measurements of reversal potentials in fibroblasts isolated from normal and infarcted hearts. In addition, the increased outward membrane currents in fibroblasts isolated from infarcted hearts could also contribute to myocyte APD shortening. Interestingly, this difference in APD values between the two fibroblast sources was not observed at higher plating densities. Modeling studies have predicted increases in coupling will result in longer APDs and that this effect is more pronounced at higher fibroblast densities. At the two higher plating densities used in this study, the APD prolonging effect due to increased coupling in the fibroblasts isolated from infarcted hearts dominates over the hyperpolarization induced shortening effect mentioned above. These opposing effects resulted in APD values that are not significantly different between the two fibroblast sources.

In summary, the effect of fibroblasts on conduction properties and myocyte APD are highly dependent on density. At low densities, APD decreases and CV is unaltered or slightly increased. As the density of fibroblasts is increased, there is a slight prolongation of APD and a significant CV slowing effect that is enhanced with cardiac injury. These changes have the potential to significantly alter the substrate for reentrant activation in regions with high myofibroblast densities and highlight the fibroblast activation process as a therapeutic target for the prevention of cardiac arrhythmias.

Study Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This study relied on in vitro methods. Isolated fibroblasts maintained under standard tissue culture conditions have been shown to undergo a differentiation process, increase in size and are removed from the mechanical and chemical environment that may regulate function. Culture conditions for all groups in this study were identical, however further studies would be required to determine whether there is a differential response to the in vitro environment depending on the fibroblast source. This study relied on neonatal myocytes to evaluate the ability of fibroblasts to modulate electrophysiological parameters. Further studies are needed to evaluate the interaction between fibroblasts from infarcted hearts and adult myocytes. Finally, we were not able to identify an appropriate loading control for the freshly isolated fibroblasts that was not significantly altered between fibroblast sources. Appropriate loading controls for ischemic cardiac tissue have not been systematically studied. Several loading controls were evaluated and all showed statistically significant differences between groups when loading the same amount of protein. This difference in loading controls was not observed in the cultured fibroblasts.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is known?

Cardiac fibrosis is associated with many forms of cardiovascular disease and is one of the mechanisms that contribute to the development of arrhythmias.

Fibroblasts can modulate myocyte electrophysiology through a number of mechanisms including the release of chemical mediators, deposition of extracellular matrix and direct coupling with myocytes.

Fibroblasts undergo a phenotypic change in response to cardiac injury resulting in numerous functional changes; however no information is available on the cellular electrophysiological effects of this process.

What new information does this article contribute?

Cardiac injury alters the profile of paracrine factors released by fibroblasts resulting in myocyte action potential abbreviation.

Fibroblasts from infarcted hearts have more hyperpolarized resting membrane potentials and increased outward currents compared with fibroblasts from normal hearts.

Fibroblast connexin43 levels and intercellular coupling to myocytes is greater in fibroblasts from infarcted hearts leading to increased electrotonic interactions and enhanced modulation of myocyte electrophysiology.

Summary

The underlying mechanisms behind sudden cardiac death remain poorly understood. Fibrosis is associated with many forms of cardiovascular disease including heart failure, hypertension, myocardial ischemia, atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis, and it could be one of the mechanisms that contribute to the development of arrhythmias. Cardiac research has mainly focused on understanding the electrophysiological changes that occur in myocytes, neglecting the potential contribution of changes in other, non-excitable cells in the heart. Traditionally, fibroblasts have been regarded as passive cells responsible for extracellular matrix production. However, increasing recent evidence suggest that these cells may be involved in the response of the myocardium to mechanical and chemical signals in health and disease. In this study, we investigated the electrophysiological consequences of fibroblast activation and the functional changes in fibroblast-myocyte interactions in response to cardiac injury. This study demonstrates for the first time that fibroblast activation is associated with important electrophysiological changes that may facilitate the stabilization of reentrant activation and contribute to the high incidence of arrhythmias observed in fibrotic hearts. These findings suggest new therapeutic approaches targeting the fibroblast activation process may be beneficial in the prevention of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Karen Maass for her contribution to the Western blot experiments.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants to GEM (HL76751), CV (1T32HL098129) and an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship award to CV (0725898T).

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- APD

Action potential duration

- APD70

Action potential duration at 70% repolarization

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin BrdU; Bromodeoxyuridine

- BrdU

Bromodeoxyuridine

- CBX

Carbenoxolone

- CM

Conditioned media

- CV

Conduction velocity

- C×43

Connexin43

- C×45

Connexin45

- Fb

Fibroblasts isolated from normal hearts

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Gap-FRAP

Gap fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- GRO/KC

Growth regulated oncogene/keratinocyte chemoattractant

- HBSS

Hank’s buffered salt solution

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- IL

Interleukin

- Im

Membrane current density

- LAD

Left anterior descending coronary artery

- MI-Fb

Fibroblasts isolated from infarcted hearts

- Myo

Homocellular myocyte cultures

- RMP

Resting membrane potential

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- Vm

Membrane voltage

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Presented in part at the 2009 Biophysical Society Annual Meeting (Biophysical Journal. 2009;96:562a-563a), 2009 Heart Rhythm Annual Scientific Sessions (Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:S458) and the 2010 Biophysical Society Annual Meeting (Biophysical Journal. 2010;98:95a).

References

- 1.Desmouliere A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sappino AP, Schurch W, Gabbiani G. Differentiation repertoire of fibroblastic cells: Expression of cytoskeletal proteins as marker of phenotypic modulations. Lab Invest. 1990;63:144–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powell DW, Mifflin RC, Valentich JD, Crowe SE, Saada JI, West AB. Myofibroblasts. I. Paracrine cells important in health and disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrov VV, Fagard RH, Lijnen PJ. Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth factor-beta1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Hypertension. 2002;39:258–263. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Chen H, Seth A, McCulloch CA. Mechanical force regulation of myofibroblast differentiation in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1871–1881. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00387.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miragoli M, Salvarani N, Rohr S. Myofibroblasts induce ectopic activity in cardiac tissue. Circ Res. 2007;101:755–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miragoli M, Gaudesius G, Rohr S. Electrotonic modulation of cardiac impulse conduction by myofibroblasts. Circulation Research. 2006;98:801–810. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000214537.44195.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flack EC, Lindsey ML, Squires CE, Kaplan BS, Stroud RE, Clark LL, Escobar PG, Yarbrough WM, Spinale FG. Alterations in cultured myocardial fibroblast function following the development of left ventricular failure. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2006;40:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squires CE, Escobar GP, Payne JF, Leonardi RA, Goshorn DK, Sheats NJ, Mains IM, Mingoia JT, Flack EC, Lindsey ML. Altered fibroblast function following myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarvis MD, Rademaker MT, Ellmers LJ, Currie MJ, McKenzie JL, Palmer BR, Frampton CM, Richards AM, Cameron VA. Comparison of infarct-derived and control ovine cardiac myofibroblasts in culture: Response to cytokines and natriuretic peptide receptor expression profiles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1952–1958. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00764.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner PI, Ursell PC, Fenoglio JJ, Jr, Wit AL. Electrophysiologic and anatomic basis for fractionated electrograms recorded from healed myocardial infarcts. Circulation. 1985;72:596–611. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camelliti P, Green CR, LeGrice I, Kohl P. Fibroblast network in rabbit sinoatrial node: Structural and functional identification of homogeneous and heterogeneous cell coupling. Circ Res. 2004;94:828–835. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122382.19400.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chilton L, Giles WR, Smith GL. Evidence of intercellular coupling between co-cultured adult rabbit ventricular myocytes and myofibroblasts. J Physiol. 2007;583:225–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman SA, Miller JM, Hsia HH, Buxton AE. Radiofrequency ablation of a supraventricular tachycardia due to interatrial conduction from the recipient to donor atria in an orthotopic heart transplant recipient. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1995;6:544–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1995.tb00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Nakajima H, Soonpaa MH, Nakajima HO, Field LJ. Physiological coupling of donor and host cardiomyocytes after cellular transplantation. Circ Res. 2003;92:1217–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000075089.39335.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Maziere AM, van Ginneken AC, Wilders R, Jongsma HJ, Bouman LN. Spatial and functional relationship between myocytes and fibroblasts in the rabbit sinoatrial node. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1992;24:567–578. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)91041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camelliti P, Devlin GP, Matthews KG, Kohl P, Green CR. Spatially and temporally distinct expression of fibroblast connexins after sheep ventricular infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rook MB, van Ginneken AC, de Jonge B, el Aoumari A, Gros D, Jongsma HJ. Differences in gap junction channels between cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, and heterologous pairs. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C959–977. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.5.C959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fast VG, Darrow BJ, Saffitz JE, Kleber AG. Anisotropic activation spread in heart cell monolayers assessed by high-resolution optical mapping. Role of tissue discontinuities. Circ Res. 1996;79:115–127. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feld Y, Melamed-Frank M, Kehat I, Tal D, Marom S, Gepstein L. Electrophysiological modulation of cardiomyocytic tissue by transfected fibroblasts expressing potassium channels: A novel strategy to manipulate excitability. Circulation. 2002;105:522–529. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudesius G, Miragoli M, Thomas SP, Rohr S. Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circulation Research. 2003;93:421–428. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089258.40661.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chilton L, Ohya S, Freed D, George E, Drobic V, Shibukawa Y, Maccannell KA, Imaizumi Y, Clark RB, Dixon IM, Giles WR. K+ currents regulat the resting membrane potential, proliferation, and contractile responses in ventricular fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2931–H2939. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01220.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacCannell KA, Bazzazi H, Chilton L, Shibukawa Y, Clark RB, Giles WR. A mathematical model of electrotonic interactions between ventricular myocytes and fibroblasts. Biophys J. 2007;92:4121–4132. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacquemet V, Henriquez CS. Modelling cardiac fibroblasts: Interactions with myocytes and their impact on impulse propagation. Europace. 2007;9(Suppl 6):vi29–37. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohl P. Heterogeneous cell coupling in the heart: An electrophysiological role for fibroblasts. Circ Res. 2003;93:381–383. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091364.90121.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachse FB, Moreno AP, Abildskov JA. Electrophysiological modeling of fibroblasts and their interaction with myocytes. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:41–56. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacquemet V, Henriquez CS. Loading effect of fibroblast-myocyte coupling on resting potential, impulse propagation, and repolarization: Insights from a microstructure model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2040–2052. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01298.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sachse FB, Moreno AP, Seemann G, Abildskov JA. A model of electrical conduction in cardiac tissue including fibroblasts. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37:874–889. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9667-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie Y, Garfinkel A, Camelliti P, Kohl P, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Effects of fibroblast-myocyte coupling on cardiac conduction and vulnerability to reentry: A computational study. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohr S, Fluckiger-Labrada R, Kucera JP. Photolithographically defined deposition of attachment factors as a versatile method for patterning the growth of different cell types in culture. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-1000-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeffer JM, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Influence of chronic captopril therapy on the infarcted left ventricle of the rat. Circ Res. 1985;57:84–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frangogiannis NG, Michael LH, Entman ML. Myofibroblasts in reperfused myocardial infarcts express the embryonic form of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (smemb) Cardiovasc Res. 2000;48:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleutjens JP, Kandala JC, Guarda E, Guntaka RV, Weber KT. Regulation of collagen degradation in the rat myocardium after infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(05)82390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleutjens JP, Verluyten MJ, Smiths JF, Daemen MJ. Collagen remodeling after myocardial infarction in the rat heart. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:325–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Y, Zhang JQ, Zhang J, Lamparter S. Cardiac remodeling by fibrous tissue after infarction in rats. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:316–323. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.105971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gustafsson AB, Brunton LL. Beta -adrenergic stimulation of rat cardiac fibroblasts enhances induction of nitric-oxide synthase by interleukin-1beta via message stabilization. Molecular Pharmacology. 2000;58:1470–1478. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morley GE, Vaidya D, Samie FH, Lo C, Delmar M, Jalife J. Characterization of conduction in the ventricles of normal and heterozygous cx43 knockout mice using optical mapping. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:1361–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leaf DE, Feig JE, Vasquez C, Riva PL, Yu C, Lader JM, Kontogeorgis A, Baron EL, Peters NS, Fisher EA, Gutstein DE, Morley GE. Connexin40 imparts conduction heterogeneity to atrial tissue. Circ Res. 2008;103:1001–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.168997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lampe PD, Cooper CD, King TJ, Burt JM. Analysis of connexin43 phosphorylated at s325, s328 and s330 in normoxic and ischemic heart. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3435–3442. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldsmith EC, Hoffman A, Morales MO, Potts JD, Price RL, McFadden A, Rice M, Borg TK. Organization of fibroblasts in the heart. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:787–794. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. The cardiac fibroblast: Therapeutic target in myocardial remodeling and failure. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2005;45:657–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaFramboise WA, Scalise D, Stoodley P, Graner SR, Guthrie RD, Magovern JA, Becich MJ. Cardiac fibroblasts influence cardiomyocyte phenotype in vitro. Am J Physiol Cel Physiol. 2007;292:C1799–1808. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00166.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fahrenbach JP, Mejia-Alvarez R, Banach K. The relevance of non-excitable cells for cardiac pacemaker function. J Physiol. 2007;585:565–578. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zlochiver S, Munoz V, Vikstrom KL, Taffet SM, Berenfeld O, Jalife J. Electrotonic myofibroblast-to-myocyte coupling increases propensity to reentrant arrhythmias in two-dimensional cardiac monolayers. Biophys J. 2008;95:4469–4480. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pedrotty DM, Klinger RY, Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Cardiac fibroblast paracrine factors alter impulse conduction and ion channel expression of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:688–697. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]