Abstract

Although research has been conducted on the course, consequences, and correlates of borderline personality disorder (BPD), little is known about its emergence in childhood, and no studies have examined the extent to which theoretical models of the pathogenesis of BPD in adults are applicable to the correlates of borderline personality symptoms in children. The goal of this study was to examine the interrelationships between two BPD-relevant personality traits (affective dysfunction and disinhibition), self- and emotion regulation deficits, and childhood borderline personality symptoms among 263 children aged 9 to 13. We predicted that affective dysfunction, disinhibition, and their interaction would be associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms, and that self- and emotion-regulation deficits would mediate these relationships. Results provided support for the roles of both affective dysfunction and disinhibition (in the form of sensation seeking) in childhood borderline personality symptoms, as well as their hypothesized interaction. Further, both self- and emotion-regulation deficits partially mediated the relationship between affective dysfunction and childhood borderline personality symptoms. Finally, results provided evidence of different gender-based pathways to childhood borderline personality symptoms, suggesting that models of BPD among adults are more relevant to understanding the factors associated with borderline personality symptoms among girls than boys.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, childhood disorders, emotion dysregulation, sensation seeking, emotional vulnerability

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious mental health problem with great public health significance. Although BPD is found at rates of 1–2% in the general population (Lenzenweger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007; Skodol et al., 2002), individuals with BPD represent approximately 15% of clinical populations (Skodol et al., 2002; Widiger & Weissman, 1991) and are major consumers of health care resources (Skodol et al., 2005; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Khera, & Bleichmar, 2001). Further, BPD is associated with severe functional impairment (Skodol et al., 2002, 2005), high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Skodol et al., 2002; Zanarini et al., 1998a, 1998b), and elevated risk for completed suicide (occurring at a rate of 10%; Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder, 2001).

Although research has been conducted on the prognosis, course, consequences, and correlates of BPD, little is known about the emergence and early manifestations of this disorder (Crick, Murray-Close, & Woods, 2005; Paris, 2005). However, given evidence that personality develops from an early age (Hartup & van Lieshout, 1995) and that adults with BPD report having experienced many borderline personality symptoms in childhood (Reich & Zanarini, 2001; Zanarini et al., 2006), early manifestations of borderline personality pathology can likely be observed in childhood and warrant empirical attention. Indeed, not only would research on the early manifestations of borderline pathology have important implications for the development of secondary prevention programs, studies examining the risk factors associated with the emergence of borderline pathology in childhood may increase our understanding of the pathogenesis of BPD per se.

Despite the obvious clinical relevance of this research, few studies have examined the factors associated with the emergence of borderline pathology in children. One likely reason for the paucity of research in this area is that the identification of personality disorders in youth was discouraged historically (due to concerns about the validity of personality disorder diagnoses prior to adulthood). Further, given that past research on childhood borderline pathology has been fraught with the use of inconsistent terms, differing conceptualizations and operationalizations of childhood borderline pathology, and a lack of empirically-validated measures, the progression of research in this area has been limited.

Conceptualizations of Childhood Borderline Pathology

The earliest descriptions of borderline pathology in children encompassed diverse clinical criteria (Ekstein & Wallerstein, 1954; Freud, 1969; Frijling-Schreuder, 1969). The term “borderline” was first used by Ekstein and Wallerstein (1954) to refer to a group of children characterized primarily by unpredictability and rapid fluctuations in ego functioning and interpersonal relationships. These children were considered to be on the border between neurosis and psychosis. The term borderline has also been used to refer to children on the border of receiving a diagnosis of an organic disorder (Kernberg, 1983). Other early conceptualizations of borderline children emphasized the role of micro-psychotic symptoms, loneliness, and intense anxiety (Frijling-Schreuder, 1969; Rosenfeld & Sprince, 1963). Extending this research, the early 1980's brought an interest in identifying specific criteria for the diagnosis of borderline disorders in childhood (Bemporad, Smith, Hanson, & Cicchetti, 1982; Pine, 1983; Vela, Gottlieb, & Gottlieb, 1983). Some of the first sets of diagnostic criteria were based on reviews of the extant clinical literature and/or clinical observations of “borderline children” and demonstrated considerable overlap with one another, including criteria pertaining to excessive and severe anxiety, impulse control problems, disturbed interpersonal relationships, disturbances in cognitive processes (including quasi-psychotic phenomena), and marked fluctuations in functioning (Bemporad et al., 1982, Vela et al., 1983; see also Pine, 1983).

These early conceptualizations of childhood borderline pathology describe a heterogeneous population (likely encompassing children with both borderline personality and schizotypal personality pathologies; Petti & Vela, 1990) and have been criticized for showing little resemblance to adult BPD (Gualtieri, Koriath, & Van Bourgondien, 1983; Palombo, 1982). Thus, it is unclear to what extent childhood borderline disorders (as defined above) reflect the emergence of adult BPD pathology. Indeed, more recently, this clinical presentation has been termed “multiple complex developmental disorder” (Towbin, Dykens, Pearson, & Cohen, 1993), “multidimensionally impaired disorder” (Kumra et al., 1998), and “emoto-cognitive dys-social disorder” (Ad-Dab'Bagh & Greenfield, 2001), in light of the apparent lack of continuity between these conceptualizations of childhood borderline disorder and adult BPD.

Bearing a stronger resemblance to adult BPD, more recent conceptualizations of childhood borderline pathology reflect efforts to adapt adult BPD criteria for use with children (e.g., Goldman, D'Angelo, DeMaso, & Mezzacappa, 1992; Goldman, D'Angelo, & DeMaso 1993; Guzder, Paris, Zelkowitz, & Marchessault, 1996; Guzder, Paris, Zelkowitz, & Feldman, 1999; Greenman, Gunderson, Cane, & Saltzman, 1986; Paris, Zelkowitz, Guzder, Joseph, & Feldman, 1999). These approaches use modified criteria corresponding to adult BPD diagnostic criteria to diagnose BPD in children. Nevertheless, despite the clearer overlap between these conceptualizations of childhood borderline pathology and adult BPD (as well as their greater reliability and predictive validity, compared to earlier conceptualizations), the practice of diagnosing BPD in childhood has been criticized for assuming a stability in functioning and developmental trajectory that likely vary (Coolidge, 2005; Crick et al., 2005).

In contrast to these approaches, developmental researchers emphasize the importance of assessing childhood borderline pathology dimensionally (vs. categorically) and within a developmental psychopathology framework. Such an approach allows for an examination of the full range of borderline personality symptom severity and dose-response relationships, and does not assume the presence of pathology (as problem behavior is conceptualized as falling on a continuum ranging from none to severe). Further, a developmental psychopathology perspective suggests the importance of examining the ways in which various biological, psychological, and social-contextual factors interact to predict normal and abnormal development across the life course (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009), emphasizing the likelihood of varying pathways to both adaptive and maladaptive outcomes. As such, the same constellation of symptoms in childhood may lead to a variety of outcomes (i.e., multifinality; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996, 2002), and one outcome may emerge as a result of different risk factors or developmental processes (i.e., equifinality; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996, 2002).

As applied here, a developmental psychopathology approach suggests that childhood borderline personality symptoms may have many different trajectories, and should not be considered indicative of an enduring disorder (as these symptoms will not necessarily evolve on one course to the development of BPD in adulthood). Rather, consistent with the concept of multifinality, children who display early signs and symptoms of borderline personality pathology are expected to take different pathways depending on the risk and protective factors they encounter (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993). For example, the presence of borderline personality symptoms in children may lead to a variety of outcomes, ranging from the development of personality disorders or other forms of pathology in adolescence and adulthood to more adaptive outcomes (reflecting the absence of any enduring pathology). Furthermore, the emergence of borderline pathology in childhood may, for some children, be indicative of risk for the later development of BPD (as it is likely that this disorder has its origins earlier in development). Of course, it is also important to note that the presence of borderline personality symptoms in childhood likely represent only one pathway through which BPD may develop, with other difficulties in childhood also potentially leading to BPD in adulthood. Nonetheless, given evidence of a connection between childhood and adulthood forms of other disorders (see Rutter, 1996), examining the presence of childhood borderline personality symptoms is a useful first step in examining the emergence of borderline personality pathology earlier in the lifespan.

Consistent with this approach, Crick et al. (2005) modified a dimensional measure of BPD features in adults for use with children aged 9 and older. This measure provides an assessment of childhood borderline personality features that represent developmentally-appropriate manifestations of the corresponding adult BPD features. The researchers argue that “although BPD is not clearly defined in childhood, some children do exhibit features characteristic of adult borderline pathology, reflecting the emergence of borderline pathology across development” (Crick et al., 2005, pg. 1052). Likewise, Coolidge (2005) argues for the importance of assessing age-appropriate manifestations of borderline personality symptoms dimensionally among children, suggesting that although it may be neither desirable nor possible to diagnose children with BPD, research on the emergence and early manifestations of borderline personality symptoms among children has important clinical and research implications.

It is this approach to the conceptualization and assessment of childhood borderline pathology that is used here. Specifically, this study examines the emergence of borderline personality pathology among children, referred to here as childhood borderline personality symptoms. According to the conceptualization used here, although borderline personality symptoms may be expressed differently in childhood than adulthood (e.g., with the BPD relationship instability criterion pertaining to friends in childhood and intimate relationships in adulthood, or the anger criterion corresponding to temper tantrums in childhood and physical violence in adulthood), the presence of these symptoms in childhood may reflect the emergence of borderline personality pathology. Thus, although childhood borderline personality symptoms are expected to take variable pathways into adulthood (ranging from resilience to pathology), these symptoms may be indicative of risk for later BPD, and, as such, warrant empirical attention. In particular, research on the factors associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms may provide important information regarding the development and pathogenesis of borderline pathology in general, as well as facilitate the identification of children at risk for the development of borderline personality symptoms (potentially paving the way for prevention efforts).

Theories of the Pathogenesis of Borderline Personality Pathology

Extant theoretical models of the pathogenesis of BPD suggest that this disorder is best accounted for within the context of a diathesis-stress model, resulting from the interaction of environmental stressors and trait vulnerabilities (Linehan, 1993; Paris, 1997; Zanarini & Frankenburg, 1997). With regard to the former, researchers have highlighted the role of adverse childhood experiences in the development of BPD, in particular childhood maltreatment (including sexual, physical, and emotional abuse [Bornovalova, Gratz, Delany-Brumsey, Paulson, & Lejuez, 2006; Gibb, Wheeler, Alloy, & Abramson, 2001; Trull, 2001; Zanarini et al., 1997; Zweig-Frank & Paris, 1991], and emotional and physical neglect [Gunderson & Englund, 1981; Johnson, Smailes, Cohen, Brown, & Bernstein, 2000; Zanarini et al., 1997]). These experiences alone are not sufficient to account for the development of BPD, however, and are thought to lead to BPD only in the context of an underlying vulnerability. Specifically, consistent with its categorization as a personality disorder, theories of BPD implicate certain personality traits in the vulnerability for this disorder, with affective dysfunction and disinhibition in particular identified as the “core” traits underlying BPD (Linehan, 1993; Livesley, Jang, & Vernon, 1998; Nigg, Silk, Stavro, & Miller, 2005; Siever & Davis, 1991; Skodol et al., 2002). Moreover, although these traits are not considered to be specific to BPD in and of themselves, researchers have suggested that it is the interaction of affective dysfunction and disinhibition that likely distinguishes BPD from other disorders (Depue & Lenzenweger, 2001; Nigg et al., 2005; Paris, 2005; Siever & Davis, 1991; Silverman et al., 1991; Trull, 2001).

Consistent with the emphasis on the roles of affective dysfunction (including emotional intensity, reactivity, and lability) and disinhibition (including impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and risk-taking) in BPD, these higher-order traits have received the most attention from researchers, and their relationship to BPD among adult patients is well-documented. For example, research provides evidence for a strong association between affective dysfunction and BPD. This affective dysfunction is thought to encompass several lower-order emotion-related traits, including anxiousness and affective lability (Livesley et al., 1998), emotional intensity, reactivity, and sensitivity (Linehan, 1993), and affective instability (i.e., marked, reactive shifts in mood; Siever & Davis, 1991; Skodol et al., 2002), all of which have been found to be heightened in adult patients with BPD. Specifically, research indicates that adult patients with BPD: (a) report heightened affective instability (Bornovalova et al., 2006; Henry et al., 2001; Koenigsberg et al., 2002) and affect intensity/reactivity (Henry et al., 2001; Koenigsberg et al., 2002); (b) evidence heightened sensitivity to emotional stimuli (Donegan et al., 2003; Herpertz et al., 2001); and (c) exhibit elevated symptoms of anxiety (Snyder & Pitts, 1988).

Research likewise provides evidence for a relationship between disinhibition and BPD. Specifically, behavioral dyscontrol or impulsiveness (in the form of deliberate self-harm, suicidal behaviors, substance use, and risky sexual behavior, among others) is one of the central defining features of BPD (see Paris, 2005; Skodol et al., 2002), and is thought to stem from one of several lower-order disinhibition-related traits, including sensation seeking, risk-taking, novelty seeking, and impulsivity (see Verheul, 2006). Indeed, research provides evidence for an association between each of these lower-order traits and BPD, with studies finding that adults with BPD report heightened levels of: (a) sensation seeking (Reist, Haier, DeMet, & Chicz-DeMet, 1990); (b) risk-taking (Dowson et al., 2004; Kilpatrick et al., 2007); (c) novelty seeking (Pukrop, 2002); and (d) impulsivity (Bornovalova et al., 2006; Henry et al., 2001; Hochhausen, Lorenz, & Newman, 2002). Further, Aluja, Cuevas, Garcia, and Garcia (2007) found that sensation seeking was one of the traits most strongly predictive of BPD pathology among adults.

Of course, the relationship between these personality traits (i.e., affective dysfunction and disinhibition) and BPD is not considered to be direct. Instead, researchers have suggested that these traits increase the risk for BPD through their relationship with deficits in self- and emotion-regulation, both of which are considered to be core mechanisms underlying the development of BPD (Linehan, 1993; Ryan, 2005). Self-regulation is broadly defined as the capacity to plan and execute control over one's experience (Baumeister, 1998), and refers to the ability to adaptively regulate all aspects of one's experience, particularly impulses and behaviors (represented by the construct of ego-control within the developmental literature; Block & Block, 1980). Although maladaptive self-regulation can take the form of both over-regulation (including inflexible responding and non-awareness of one's internal experience) and under-regulation (reflecting a lack of adequate regulatory capacities and including such difficulties as impulsive behaviors; Ryan, 2005), the deficits in self-regulation considered to be most relevant to BPD are those related to under-regulation. Indeed, studies of young adults have found that self-regulation is negatively associated with BPD-related pathology (r = −.65; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004).

More specifically, emotion regulation is considered to play an integral role in the development of BPD (Putnam & Silk, 2005) and to be one of the central defining features of this disorder (Linehan, 1993). Indeed, Linehan (1993) suggests that deficits in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between affective dysfunction and BPD. Unlike affective dysfunction, emotion regulation does not refer to the nature or quality of one's emotional responses. Instead, deficits in emotion regulation involve maladaptive ways of responding to one's emotions (regardless of their intensity, reactivity, or frequency), including difficulties modulating emotional arousal, difficulties controlling behaviors in the face of emotional distress, and deficits in the functional use of emotions as information. As such, emotion regulation deficits are distinguished from trait affective dysfunction, as the presence of this trait vulnerability (in and of itself) does not preclude adaptive regulation. Nonetheless, consistent with theories suggesting the mediating role of emotion regulation deficits in the relationship between trait affective dysfunction and BPD (Linehan, 1993), evidence suggests that affective dysfunction increases the risk for emotion regulation difficulties (Flett, Blankstein, & Obertynski, 1996; Gratz, Tull, Baruch, Bornovalova, & Lejuez, 2008), as intense/reactive emotions are more difficult to regulate (Flett et al., 1996). Consistent with the theoretical emphasis on the role of emotion regulation in BPD, research provides evidence for a relationship between emotion regulation deficits and BPD in adulthood (Bornovalova et al., 2008; Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez, & Gunderson, 2006; Levine, Marziali, & Hood, 1997). Further, recent evidence provides support for the mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between affective dysfunction and BPD among adults, with Gratz et al. (2008) finding that emotion dysregulation fully mediated the relationship between negative affect intensity/reactivity and BPD symptoms.

Unfortunately, despite the complexity of the theorized interrelationships of these traits and developmental processes in the development of BPD, no studies have examined the ways in which affective dysfunction and disinhibition interact to predict BPD, nor have studies examined the mediating role of self- and emotion-regulation deficits in the relationship between these traits and BPD. Furthermore, no research has examined if these personality traits and mediators are associated with the emergence of borderline personality pathology in childhood. However, findings that the environmental and neuropsychological factors associated with a BPD diagnosis in childhood are the same as those associated with BPD in adults (Goldman et al., 1992; Guzder et al., 1996, 1999; Paris et al., 1999; Zelkowitz, Paris, Gudzer & Feldman, 2001) suggest that the traits and mediators theorized to be central to the pathogenesis of BPD in adults may likewise be associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms. At the very least, examining the applicability of extant models of the pathogenesis of BPD among adults to the emergence of borderline pathology in childhood may be a useful starting point.

Factors Associated with Borderline Personality Pathology in Childhood

Although almost no research to date has examined the personality traits associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms, researchers have suggested that the trait vulnerabilities of affective dysfunction and disinhibition likely underlie the development of borderline personality pathology in children (Guzder et al., 1999). Further, studies of the likely behavioral manifestations of these traits provide suggestive evidence for the role of both affective dysfunction and disinhibition in childhood borderline personality pathology.

With regard to the relationship between affective dysfunction and childhood borderline personality pathology, Crick et al. (2005) found that one aspect of affective dysfunction (i.e., emotional sensitivity) uniquely predicted borderline personality features in a community sample of children over time. As for the potential manifestations of affective dysfunction, studies of primarily male psychiatric patients aged 6–12 have found higher levels of anxiety and depression among patients with a diagnosis of BPD (vs. those without a BPD diagnosis; Greenman, Gunderson, Cane, & Saltzman, 1986; Guzder et al., 1999). Although this use of BPD diagnoses differs from the dimensional approach to the conceptualization and operationalization of childhood borderline personality symptoms used here, these findings provide suggestive support for a relationship between affective dysfunction (or, more specifically, psychopathological manifestations of affective dysfunction) and childhood borderline personality pathology.

As for the relationship between disinhibition and childhood borderline personality pathology, Paris et al. (1999) found that the presence of a BPD diagnosis among a sample of primarily male psychiatric patients aged 6–12 was associated with heightened levels of disinhibition (in the form of impulsivity). However, as with the aforementioned research on affective dysfunction, most research on the relationship between disinhibition and childhood borderline personality pathology has focused on behavioral manifestations of disinhibition, particularly aggressive and delinquent behavior. These studies have found that a diagnosis of BPD among samples of primarily male psychiatric patients aged 6–12 is associated with heightened levels of aggressive and delinquent behavior (Greenman et al., 1986; Guzder et al., 1999). Further, utilizing a dimensional measure of borderline personality features in childhood, Crick et al. (2005) found that both physical and relational aggression predicted borderline personality features in children over time (with changes in relational aggression in particular being uniquely associated with changes in borderline personality features).

As was the case with the adult BPD literature, however, researchers have not examined explicitly the interaction of affective dysfunction and disinhibition in the risk for childhood borderline personality symptoms. Further, in regard to the potential mediating role of self- and emotion-regulation deficits in the relationship between these personality traits (and their interaction) and childhood borderline personality symptoms, no studies to date have examined the relationship between self- and emotion-regulation deficits and childhood borderline personality symptoms. However, researchers in the area of developmental psychology have long suggested that these capacities are integral to normative development (Block & Block, 1980; Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994; Fox, 1994), and research on the correlates of self- and emotion-regulation among children provides suggestive evidence for the importance of these phenomena to borderline personality symptoms in childhood (as deficits in each have been found to be associated with a range of negative borderline personality-relevant outcomes). For example, research indicates that ego-undercontrol is associated with socially-inappropriate behavior during late childhood (Eisenberg et al., 2003) and engagement in high-risk behaviors during adolescence (Block, Block, & Keyes, 1988). Moreover, prospective studies of the predictors of interpersonal difficulties during early adolescence have found that ego-undercontrol predicts aggressive behavior (Asendorpf & van Aken, 1999; Hart, Keller, Edelstein, & Hofmann, 1998). Finally, research indicates that emotion regulation deficits are associated with behavioral problems (Shields & Cicchetti, 1998).

As such, preliminary evidence suggests a potential relationship between deficits in self- and emotion-regulation and borderline personality-relevant pathology among children and adolescents, although the extent to which these deficits are associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms per se remains unclear. Further, the extent to which deficits in these capacities mediate the relationship between affective dysfunction and disinhibition and childhood borderline personality symptoms is unknown. Nonetheless, lending support to the conceptualization of self- and emotion-regulation deficits as mediators of the relationship between the traits of interest and childhood borderline personality symptoms, research suggests that both affective dysfunction and disinhibition interfere with the development of self- and emotion-regulation capacities throughout childhood (Calkins & Johnson, 1998; Carlson & Wang, 2007; Eisenberg et al., 1997; Santucci et al., 2008). For example, Eisenberg et al. (1997) found that parent and teacher ratings of children's negative emotionality (i.e., emotional intensity and reactivity) were negatively associated with ratings of children's ego-control, and Calkins and Johnson (1998) found that emotional reactivity to a frustrating task was negatively associated with the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies among toddlers. As such, these findings (in combination with the aforementioned findings that both the traits and proposed mediators predict borderline personality pathology and/or borderline personality-relevant outcomes) suggest that self- and emotion regulation deficits may mediate the relationship between these traits and borderline personality symptoms in childhood.

Gender-based Equifinality in the Development of Childhood Borderline Personality Symptoms

The principle of equifinality suggests that children may take different pathways to the development of borderline personality symptoms, with the risk factors for these symptoms differing across children. One factor that may arguably be of particular relevance to investigations of equifinality within developmental psychopathology is gender, with researchers proposing different gender-based pathways to psychopathology (e.g., depression; Gjerde & Block, 1996; see also Duggal, Carlson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2001). In general, research on gender-based pathways to psychopathology highlights the importance of examining the risk factors associated with various forms of psychopathology among females and males separately.

The concept of gender-based equifinality may be particularly relevant to an outcome such as borderline personality pathology, which has long been studied primarily among women. Yet, despite the long-held assumption that BPD is much more prevalent among women than men, a growing body of research within community samples indicates no significant gender differences in the rates of BPD among adolescents and adults (Bernstein et al., 1993; Lenzenweger et al., 2007; Torgersen, Kringlen, & Cramer, 2001). Further, research suggests that the clinical presentation of BPD may be similar across gender (Johnson et al., 2003). However, despite evidence that BPD may be just as relevant to men as women, the majority of the research on BPD has involved primarily female samples, and most theories of the pathogenesis of BPD are based on empirical and clinical literature on women. Thus, it is unclear to what extent these models are applicable to the emergence of borderline personality pathology among males.

Indeed, preliminary evidence suggests that there may be gender differences in the risk factors for borderline personality pathology, as research indicates that the factors associated with both BPD (Paris, Zweig-Frank, & Guzder, 1994a, 1994b) and specific BPD-related behaviors (e.g., deliberate self-harm; Gratz, 2006; Gratz & Chapman, 2007; Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002) differ across gender (with extant theoretical models generally having greater relevance for women; Gratz et al., 2002). Thus, findings suggest the importance of exploring the factors associated with borderline personality pathology across gender. Given that there is virtually no research on the role of gender in childhood borderline personality pathology (with no known studies exploring differences in the risk factors associated with childhood borderline personality pathology among girls and boys, and research on gender differences in levels/rates of borderline personality pathology producing mixed results [see Crick et al., 2005; Greenman et al 1986; Guzder et al. 1996; Paris, 2003]), studies exploring the factors associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms among girls and boys separately may be particularly important.

The Current Study

The goal of the current study was to examine the relationship between two core BPD-relevant personality traits, self- and emotion regulation deficits, and childhood borderline personality symptoms among a sample of children aged 9 to 13. In regard to the personality traits, we were interested in examining affective dysfunction and disinhibition (as well as their interaction). Consistent with the literature on affective dysfunction in BPD among adults, we defined affective dysfunction to include several lower-order BPD-relevant emotion-related traits, including anxiousness, affective lability, emotional intensity, and emotional reactivity. As for the particular dimensions of disinhibition of interest in this study, we focused on sensation-seeking and risk-taking, both of which have been shown to be more strongly related to borderline personality-relevant impulsive behaviors (including substance use, risky sexual behavior, and aggressive delinquent behaviors) among youth than trait impulsivity (see Lejuez, Aklin, Bornovalova, & Moolchan, 2005; Lejuez et al., 2007). Consistent with past findings (Goldman et al., 1992; Guzder et al., 1996, 1999; Paris et al., 1999), we hypothesized that models of the pathogenesis of BPD in adults would be applicable to the correlates of borderline personality symptoms in children, such that affective dysfunction, disinhibition, and their interaction would be associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms, and self- and emotion-regulation deficits would mediate these relationships. Further, to explore whether the factors associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms differ for girls and boys, post-hoc analyses examined the factors associated with borderline personality symptoms among girls and boys separately. Although this approach does not allow for a direct test of gender differences in the factors associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms, it was considered a useful first step in exploring the factors that emerge as most relevant for each gender.

Method

Participants

Participant dyads (children and their parents/legal guardians) were recruited through flyers, mailings, and media outreach in the greater Washington, DC metropolitan area, as well as study advertisements distributed to area schools, libraries, and Boys and Girls Clubs. Child-caregiver dyads were eligible for participation if the child was 9 to 13 years of age and both the primary caregiver and child were fluent in English. Data were collected from 263 children and their primary caregivers (87.3% mothers, 6.3% fathers, and 6.3% legal guardians). The child participants ranged in age from 9 to 13 (M = 11.29, SD = 1.04), and 45% (n = 118) were female. With regard to the children's racial/ethnic background, 49% were White, 35% were Black/African-American, 2% were Latino, 1% were Asian, and 13% were of another or unidentified racial/ethnic background. With regard to the educational background of the parents, 7% of the mothers and 14% of the fathers had completed high school or received a GED, 27% of the mothers and 24% of the fathers had attended at least some college or technical school, 30% of the mothers and 20% of the fathers had graduated college, and 32% of the mothers and 31% of the fathers had received an advanced degree. Median family income was $85,000 per year.

Measures

Caregiver-report measures

The Coolidge Personality and Neuropsychological Inventory for Children (CPNI; Coolidge, 2005) is a 200-item, caregiver-as-respondent measure of DSM-IV Axis I and II symptoms and related difficulties among children and adolescents. Caregivers are asked to rate the extent to which each item accurately describes their child on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 “This is strongly false for my child; My child is not at all like this.” to 4 “This is strongly true for my child; I would say this describes my child very well.”). The CPNI was normed on a sample of 780 ethnically diverse children ranging in age from 5 to 17 (Coolidge, 2005), and its psychometric properties are well-established (Coolidge, Segal, Stewart, & Ellett, 2000; Coolidge & Thede, 2000; Coolidge, Thede, & Jang, 2001; Coolidge, Thede, Stewart, & Segal, 2002). Of particular interest to the current study were the subscales assessing borderline personality symptoms and the personality trait of affective dysfunction.

The borderline personality subscale includes 9 items adapted from the DSM-IV criteria for adult BPD to be age-appropriate for children (Coolidge, 2005). To ensure that developmentally-appropriate behaviors are not erroneously considered indicative of the emergence of borderline personality pathology, the CPNI requires that parents compare their child's behavior to the behavior of other children of the same age. Further, parents are instructed to endorse only those behaviors that have been typical of their child over an extended period of time (i.e., for several months). Example items include, “My child tries very hard to avoid being alone or feeling abandoned,” “My child has threatened or tried to commit suicide or has hurt himself/herself on purpose,” and “My child makes friends quickly but soon after seems to hate them” (for a full copy of this measure, see: http://web.uccs.edu/fcoolidg/cpni/default.htm). Consistent with the conceptualization of childhood borderline personality symptoms used in this study, the CPNI takes a dimensional approach to the assessment of borderline personality symptoms among children.

The borderline personality subscale has been found to have good test-retest reliability across a 4–6 week period (r = .67; Coolidge et al., 2002), as well as good construct and concurrent validity (see Coolidge et al., 2000). Specifically, in support of the construct validity of the borderline personality subscale, children with elevated levels of borderline personality symptoms have been found to exhibit co-occurring difficulties commonly found among adults with BPD, including executive functioning deficits (Coolidge et al., 2000), impulsiveness (Kristensen & Torgersen, 2007), social anxiety (Kristensen & Torgersen, 2007), and ADHD (Coolidge et al., 2000). Further, in-line with evidence that BPD (as assessed by the SCID) is heritable among adults (with Torgersen et al. [2000] finding a heritability estimate of .69 for subthreshold BPD and .80 for definite BPD), Coolidge et al. (2001) found that elevated borderline personality symptoms as assessed by the CPNI had a heritability of .76 among 112 child twin pairs (70 monozygotic and 42 dizygotic) averaging 9 years of age. For the present study, items were summed to create a total borderline personality symptom score. Internal consistency in this sample was adequate (α = .78).

The affective dysfunction subscale of the CPNI was used to assess the trait of affective dysfunction. Although the original subscale consists of 10 items, one of these items overlaps with an item on the borderline personality subscale (i.e., the item used to assess the emotional lability criterion of borderline personality, “My child's moods change quickly.”). Therefore, this item was excluded from the affective dysfunction subscale, which was created by summing scores on the remaining 9 items (none of which overlapped with the borderline personality subscale). Sample items of this subscale include “My child's emotions seem to shift rapidly and seem to be shallow” and “My child is too touchy or easily annoyed.” The affective dysfunction subscale has been found to be have good test-retest reliability over a 4–6 week period (r = .86; Coolidge et al., 2002). Scores on the affective dysfunction items were summed to create an overall subscale score, with higher scores indicating greater affective dysfunction. Internal consistency in the current sample was good (α = .83).

The Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997) is a 24-item caregiver-report questionnaire that assesses children's abilities to regulate their emotions adaptively. Consistent with the conceptualization of emotion regulation used here, the ERC is based on the conceptual definition of emotion regulation as the ability to modulate emotional arousal so as to engage effectively with the environment (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). Caregivers use a 4-point Likert scale (1 = rarely/never; 4 = almost always) to indicate the frequency with which their child exhibits a variety of emotion regulation-related behaviors (e.g., “Can manage excitement” and “Shows the kinds of negative feelings you would expect (anger, fear, frustration, distress) when other kids are mean, aggressive or intrusive towards him/her”). The ERC has been found to be associated with other measures of childhood emotion regulation and problem behaviors among well-adjusted and maltreated samples of children aged 6 to 12 (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997, 1998).

Previous research has demonstrated that the ERC assesses two separate factors, Lability/Negativity and Emotion Regulation (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). Unlike the Lability/Negativity subscale (which assesses emotional arousal and reactivity; e.g., “Exhibits wide mood swings”), the Emotion Regulation subscale of the ERC assesses the ability to act effectively in the context of emotional arousal (including modulating emotional arousal and controlling behaviors) and emotional awareness/understanding (e.g., “Can say when s/he is feeling sad, angry or mad, fearful or afraid;” Shields & Cicchetti, 1997, 1998). Given the focus of this study on children's self- and emotion-regulation abilities, only the second factor pertaining to emotion regulation was used in this study. Items composing this factor were summed to create a total score of emotion regulation, with higher scores reflecting more adaptive emotion regulation. Internal consistency within this sample was adequate (α = .70).

The Ego-Control Measure (ECM; Eisenberg et al., 1997) is an 18-item questionnaire adapted from Block and Block's (1980) well-validated California Child Q-Sort to provide a faster caregiver-as-respondent measure of a child's level of self-regulation or ego-control. As measured here, ego-control is distinct from emotion regulation, being more closely related to the construct of reactive control (i.e., the capacity to inhibit or constrain impulsive behaviors and desires; Block & Block, 1980; Eisenberg et al., 2003). Example items include “My child starts to act immature when he/she faces difficult problems or is under stress” (reverse-coded) and “My child is inhibited and constricted (e.g., holds things in; has a hard time expressing himself/herself; is a little uptight).” Caregivers rate each item using a 9-point Likert scale reflecting the extent to which the item describes their child (1 = most undescriptive, 9 = most descriptive). This measure has been found to be associated with resiliency (Eisenberg et al., 1997, 2003) and social functioning (Eisenberg et al., 1997, 2003) among children aged 7 and older.

Consistent with past research, items on this scale were summed to create a total ego-control score, with high scores reflecting ego-overcontrol and low scores reflecting ego-undercontrol. Although this scoring procedure results in a variable for which both high and low scores represent maladjustment, studies using this measure have examined ego-control as a linear variable (Eisenberg et al., 1997, 2003), consistent with findings that the quadratic ego-control term is not significant when controlling for the linear ego-control term (Eisenberg et al., 1997, 2003). Internal consistency within this sample was adequate (α = .78).

Finally, caregivers completed a basic demographics questionnaire that asked for information regarding their educational background and annual family income, as well as their child's age, gender, and racial/ethnic background.

Child-report measures

As mentioned previously, we were interested in assessing two dimensions of trait disinhibition found to be associated with BPD-relevant impulsive behaviors among youth: risk-taking propensity and sensation seeking. With regard to the former, we used the Balloon Analogue Risk Task – Youth Version (BART-Y; Lejuez et al., 2007) to provide a behavioral assessment of risk-taking propensity. In this behavioral task, participants inflate a computer generated balloon that will explode at some point. Each pump of the balloon accrues one point in a temporary bank. Participants have the opportunity to stop pumping the balloon at any time prior to an explosion and allocate the accrued points to a permanent prize meter; if a balloon is pumped past its explosion point, then all points accrued for that balloon are lost. After a balloon explodes or points are allocated to the permanent prize meter, a new balloon appears. Upon completion of 30 balloon trials, the position of the prize meter determines the final prize, with markings indicating small, medium, large, and bonus prize.

Standardized instructions were given to each participant prior to beginning the task. These instructions included the total number of balloons and the fact that points in the prize meter would be exchangeable for prizes immediately following the task. Moreover, participants were informed that: “It is your choice to determine how much to pump up the balloon, but be aware that at some point the balloon will explode” and that “the explosion point varies across each of the thirty balloons, ranging from the first pump to enough pumps to make the balloon fill the entire computer screen.” Participants were given no other information about the probability underlying the explosion point for each balloon. Consistent with previous studies using the BART-Y (Lejuez et al., 2007), the average number of pumps on balloons that did not explode was used as an index of risk-taking propensity.

Second, we used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (BSSS; Hoyle, Stephenson, Palmgreen, Lorch, & Donohew, 2002) to assess sensation seeking. The BSSS is an 8-item self-report measure designed for use with child and adolescent samples. Example items include, “I would love to have new and exciting experiences, even if they are illegal” and “I like wild parties.” Participants are asked to rate the extent to which each item accurately describes their experience using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The BSSS has been found to be associated with other well-established measures of disinhibition (see Stephenson, Hoyle, Palmgreen, & Slater, 2003), and is predictive of impulsive behaviors such as substance use (Hoyle et al., 2002; Stephenson et al., 2003). Items were summed to create a total sensation seeking score. Internal consistency within this sample was adequate (α = .72).

The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita, Yim, Moffitt, Umemoto, & Francis, 2000) was used to assess symptoms of anxiety disorders and major depression. Participants are asked to rate the frequency with which they have experienced each item on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never; 3 = always). The RCADS has demonstrated convergent validity with other well-established measures of childhood anxiety and depression within both nonclinical (Chorpita et al., 2000) and clinical (Chorpita, Moffitt, & Gray, 2005) samples. Items were summed to create a total score, with higher scores reflecting greater depression and anxiety symptom severity. The RCADS was included in this study as a potential covariate to examine whether affective dysfunction, disinhibition, and self- and emotion regulation deficits are associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms above and beyond psychopathology in general (thereby enabling a more conservative test of the study's hypotheses). Internal consistency within this sample was good (α = .94).

A shortened version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (CDC, 2001) was used to assess delinquent behaviors (a form of externalizing psychopathology). Children were asked to indicate the past year frequency of seven different delinquent behaviors, including fighting, gambling, stealing, and carrying a weapon. Consistent with past research, items were summed to create a total delinquency score (Lejuez, Aklin, Zvolensky, & Pedulla, 2003; see also Feinberg, Greenberg, Osgood, Sartorius, & Bontempo, 2007). Like the RCADS, this measure was included as a potential covariate to examine whether the traits and proposed mediators of interest are associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms above and beyond psychopathology in general.

Procedure

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (IRB). Study advertisements instructed interested caregivers to call the University of Maryland for further details about the study. Upon calling, caregivers were informed that the purpose of the study was to examine youth risk-taking behaviors. Eligible participants (i.e., those who were fluent in English and whose children were 9–13 years of age) were scheduled for an assessment session at the University of Maryland. Participants' travel costs to and from the University were reimbursed.

Upon arrival at the assessment session, a more detailed description of the study procedures was provided and the caregivers and children signed informed consent/assent forms, respectively. The child and caregiver were then accompanied to separate rooms to complete the assessments. Standardized instructions for completing the self-report questionnaires were read aloud to each member of the dyad separately, and participants were encouraged to ask the researchers questions regarding the content or response format of the questionnaires. After completing the questionnaires, the children were provided with instructions for completing the BART-Y and encouraged to ask the researcher any questions they had about the behavioral task.

Once the participants had completed the assessments, they were debriefed and provided with their reimbursement. In particular, children were able to choose their prize (based upon their performance on the BART-Y), and parents were provided with $25 for their time.

Results

Identification of Covariates

Preliminary analyses were conducted to explore the impact of demographic factors (including age, ethnic/racial background, gender, and family income) and measures of general psychopathology (including depression and anxiety symptoms and delinquent behaviors) on the dependent variable and proposed mediators, in order to identify potential covariates for later analyses (see Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). Neither the dependent variable nor the proposed mediators were significantly associated with any of the demographic variables (rs ≤ .11; ps > .05). However, the composite measure of depression and anxiety symptom severity was significantly associated with both childhood borderline personality symptoms (r = .14; p < .05) and ego-control (r = −.21; p < .01), and the measure of delinquent behaviors was significantly associated with ego-control (r = −.17; p < .01). Thus, both of these measures of general psychopathology (representing both internalizing and externalizing symptoms) were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive data for the primary variables of interest, as well as the correlations between these variables. Results of the correlational analyses indicate that childhood borderline personality symptoms were significantly associated with the traits of affective dysfunction and sensation-seeking, and significantly negatively associated with the proposed mediators of emotion regulation and ego-control.1 Further, both emotion regulation and ego-control were significantly negatively associated with affective dysfunction, and ego-control was significantly negatively associated with sensation seeking. Given that scores on the BART-Y (i.e., average number of pumps on unexploded balloons) were not significantly associated with any of the other variables, this variable was excluded from subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for and Correlations between Primary Variables of Interest (N = 263)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BP symptoms | --- | .72** | −.02 | .22** | −.33** | −.52** | .14* | .11 | 15.06 | 4.24 |

| 2. Affective dysfunction | --- | −.06 | .13* | −.32** | −.34** | .09 | .08 | 14.64 | 4.28 | |

| 3. Risk-taking | --- | −.02 | −.00 | .04 | −.07 | −.03 | 31.49 | 13.86 | ||

| 4. Sensation seeking | --- | −.10 | −.21** | .24** | .42** | 12.79 | 5.38 | |||

| 5. Emotion regulation | --- | .04 | .10 | .01 | 27.79 | 3.29 | ||||

| 6. Ego-control | --- | −.21** | −.17** | 91.14 | 19.28 | |||||

| 7. Depression/anxiety | --- | .29** | 29.42 | 17.43 | ||||||

| 8. Delinquent behaviors | --- | 2.76 | 3.19 |

Note. BP = borderline personality.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Primary Analyses

A series of hierarchical regression analyses was conducted to test the proposed mediational model. According to Baron and Kenny (1986), support for the mediational model will be provided if: (a) the personality traits of interest (and/or their interaction) significantly predict childhood borderline personality symptoms, (b) the personality traits (and/or their interaction) significantly predict emotion regulation and ego-control, (c) emotion regulation and ego-control significantly predict childhood borderline personality symptoms, and (d) the personality traits (and their interaction) do not remain significant predictors of childhood borderline personality symptoms once emotion regulation and ego-control are entered into the equation as independent variables.

First, to examine if the personality traits (and/or their interaction) predict childhood borderline personality symptoms, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with childhood borderline personality symptoms as the dependent variable, the covariates of depression and anxiety symptom severity and delinquent behaviors entered in the first step of the equation, the traits of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking entered in the second step of the equation, and the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking entered in the third step of the equation. In line with Aiken and West (1991), predictor variables embedded within interaction terms were standardized prior to analyses. The overall model was significant, accounting for 54% of the variance in childhood borderline personality symptoms, F (5, 257) = 62.95, p < .01 (see Table 2). As predicted, the personality traits significantly predicted childhood borderline personality symptoms (above and beyond the covariates; FΔ[2, 258] = 145.11, p < .01). Further, both affective dysfunction and sensation seeking accounted for a significant amount of unique variance in childhood borderline personality symptoms (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Exploring the Roles of Sensation Seeking, Affective Dysfunction, and their Interaction in Childhood Borderline Personality Symptoms, Emotion Regulation, and Ego-Control, Controlling for Depression and Anxiety Symptom Severity and Delinquent Behaviors (N = 263)

| Borderline Personality Symptoms |

Emotion Regulation |

Ego-Control |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | b (SE) | Adj R2 | R2Δ | F | β | b (SE) | Adj R2 | R2Δ | F | β | b (SE) | Adj R2 | R2Δ | F | |

| Step 1 | .02 | .03* | 3.28* | .00 | .01 | 1.36 | .05 | .06** | 7.81** | ||||||

| Depression/anxiety | .11 | .03 (.02) | .11 | .02 (.01) | −.17** | −.19 (.07) | |||||||||

| Delinquent behaviors | .08 | .11 (.09) | −.02 | −.02 (.07) | −.12 | −.74 (.38) | |||||||||

| Step 2 | .53 | .52*** | 76.02*** | .11 | .12*** | 9.33*** | .16 | .11*** | 13.15*** | ||||||

| Sensation Seeking (SS) | .12** | .52 (.20) | −.12 | −.38 (.21) | −.11 | −2.17 (1.22) | |||||||||

| Affective dysfunction (AD) | .70*** | 2.99 (.18) | −.32*** | −1.04 (.19) | −.31*** | −6.02 (1.11) | |||||||||

| Step 3 | .54 | .01* | 62.95*** | .11 | .00 | 7.45*** | .16 | .01 | 11.17*** | ||||||

| SS × AD | .10* | .38 (.16) | .01 | .04 (.18) | −.10 | −1.71 (1.01) | |||||||||

Note. SS × AD = sensation seeking × affective dysfunction interaction.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

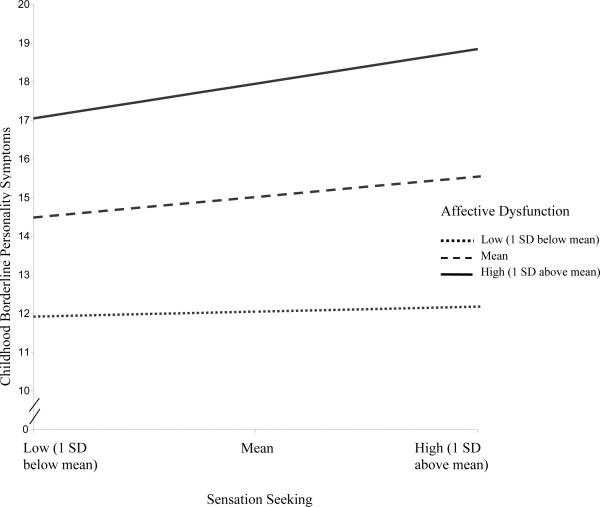

Moreover, the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking accounted for a significant amount of additional variance in borderline personality symptoms above and beyond the main effects of these traits (FΔ[1, 257] = 5.44, p < .05). This significant interaction was explored following methods outlined by Aiken and West (1991). First, the regression lines were plotted at high (one SD above the mean), medium (the mean) and low (one SD below the mean) levels of sensation seeking and affective dysfunction, and then follow-up tests were conducted to examine whether the slopes of the regression lines differed significantly from zero. These tests revealed that the relationship between sensation seeking and borderline personality symptoms increased in magnitude as affective dysfunction moved from low (b = .13, ns), to medium (b= .51, p < .05), to high (b = .90, p < .001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interactive effect of sensation seeking and affective dysfunction on childhood borderline personality symptoms among overall sample (N = 263).

Next, two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine if the personality traits (and/or their interaction) predict the proposed mediators (controlling for the same covariates described above). Results indicate that the personality traits significantly predicted both emotion regulation (R2Δ = .12, FΔ[2, 258] = 17.14, p < .001) and ego-control (R2Δ = .11, FΔ[2, 258] = 17.50, p < .001; see Table 2). However, only affective dysfunction accounted for a significant amount of unique variance in ego-control and emotion regulation (above and beyond the covariates and sensation seeking; see Table 2). Further, the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking did not account for a significant amount of additional variance in emotion regulation (FΔ[1, 257] = .05, p > .10) or ego-control (FΔ[1, 257] = 2.88, p > .05), above and beyond the main effects of these traits (see Table 2).

Next, to examine if emotion regulation and ego-control mediate the relationship between affective dysfunction (the only personality trait found to be uniquely associated with either mediator) and childhood borderline personality symptoms, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted with borderline personality symptoms as the dependent variable, the covariates entered in the first step of the equation, affective dysfunction and sensation seeking entered in the second step of the equation, the interaction of these traits entered in the third step of the equation, and emotion regulation and ego-control entered in the final step of the equation. Although emotion regulation and ego-control emerged as significant unique predictors of childhood borderline personality symptoms (accounting for an additional 8% of the variance in these symptoms; FΔ[2, 255] = 28.73, p < .001), affective dysfunction remained a significant predictor of borderline personality symptoms with the proposed mediators in the equation (see Table 3). Thus, results suggest that emotion regulation and ego-control do not fully mediate the relationship between affective dysfunction and childhood borderline personality symptoms. However, providing evidence for partial mediation, computation of Goodman (I) equations indicated that the indirect effect of affective dysfunction on childhood borderline personality symptoms through its effects on both emotion regulation (z = 2.52, p < .05) and ego-control (z = 4.51, p < .001) was significant. Thus, results suggest that two ways in which affective dysfunction may contribute to borderline personality symptoms in childhood is through its negative effects on emotion regulation and ego-control.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Examining the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation and Ego-Control in the Relationship between Sensation Seeking and Affective Dysfunction (and their Interaction) and Childhood Borderline Personality Symptoms (N = 263)

| β | b (SE) | R2(Adj) | R2Δ | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step1 | .03 (.02) | .03* | 3.28* | ||

| Depression/anxiety | .11 | .03 (.02) | |||

| Delinquent behaviors | .08 | .11 (.09) | |||

| Step 2 | .54 (.53) | .52*** | 76.02*** | ||

| Depression/anxiety | .05 | .01 (.01) | |||

| Delinquent behaviors | −.01 | −.01 (.06) | |||

| Sensation seeking | .12** | .52 (.20) | |||

| Affective dysfunction | .70*** | 2.99 (.18) | |||

| Step 3 | .55 (.54) | .01* | 62.95*** | ||

| Depression/anxiety | .06 | .01 (.01) | |||

| Delinquent behaviors | −.01 | −.01 (.06) | |||

| Sensation seeking | .12* | .51 (.20) | |||

| Affective dysfunction | .70*** | 2.95 (.18) | |||

| Sensation seeking × Affective dysfunction | .10* | .38 (.16) | |||

| Step 4 | .63 (.62) | .08*** | 62.87*** | ||

| Depression/anxiety | .04 | .01 (.01) | |||

| Delinquent behaviors | −.02 | −.03 (.06) | |||

| Sensation seeking | .07 | .31 (.18) | |||

| Affective dysfunction | .56*** | 2.39 (.18) | |||

| Sensation seeking × Affective dysfunction | .07 | .28 (.15) | |||

| Emotion regulation | −.13** | −.56 (.17) | |||

| Ego-control | −.30*** | −1.25 (.18) |

p < .05.

p < .001.

Finally, in order to examine if the synergistic influence of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking relates to borderline personality symptoms indirectly through deficits in emotion regulation and/or ego-control, we tested for the presence of mediated moderation (as outlined by Muller, Judd, and Yzerbyt, 2005). As described by Muller et al. (2005), the first condition for mediated moderation is the presence of a significant interaction between the independent variable and moderating variable in the prediction of the dependent variable. The second condition may be met in one of two ways (2a or 2b), with each way having two necessary subcomponents (i and ii). The 2a condition is met by the presence of a significant interaction effect between the independent variable and moderating variable on the mediator (i; see Table 4, equation 2 or 3) and a main effect of the mediating variable on the dependent variable (when controlling for the interactions between the moderating variable and independent variable and between the moderating variable and mediating variable; ii, see Table 4, equation 4). The 2b condition is met by the presence of an independent variable main effect on the mediating variable (i; see Table 4, equation 2 or 3) and a significant interaction between the moderating variable and mediating variable on the dependent variable (when controlling for the interaction between the moderating variable and independent variable on the dependent variable; ii, see Table 4, equation 4). Finally, the third condition for mediated moderation is met when the interaction effect of the independent variable and moderating variable on the dependent variable decreases in magnitude after entering the mediating variable into the equation.

Table 4.

Regression Analyses Examining Mediated Moderation among Overall Sample and Girls

| Criterion | Equation 1: BPS |

Equation 2: EGO |

Equation 3: EMOT |

Equation 4: BPS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sample (N = 263) |

||||||||

| Predictors | b | t | b | t | b | t | b | t |

| IV: Sensation Seeking | 0.51 | 2.59** | −0.11 | −1.75 | −0.12 | −1.80 | 0.29 | 1.58 |

| MO: Affective Dysfunction | 2.95 | 16.38*** | −0.30 | −5.30*** | −0.32 | −5.37*** | 2.24 | 11.72*** |

| IV × MO: Sensation seeking × Affective dysfunction | 0.38 | 2.33** | −0.09 | −1.69 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 1.34 |

| MED1: Ego-control | −1.24 | −6.92*** | ||||||

| MED2: Emotion regulation | −0.56 | −3.28*** | ||||||

| MED1 × MO: Ego-control × Affective dysfunction | −0.19 | −1.15 | ||||||

| MED2 × MO: Emotion regulation × Affective dysfunction | −0.28 | −1.89 | ||||||

| Girls (n = 118) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | b | t | b | t | b | t | b | t |

| IV: Sensation Seeking | 0.72 | 2.66** | −0.03 | −.37 | 0.06 | .61 | 0.66 | 2.68** |

| MO: Affective Dysfunction | 2.39 | 9.30*** | −0.32 | −3.62*** | −0.28 | −2.99** | 1.67 | 6.22*** |

| IV × MO: Sensation seeking × Affective dysfunction | 0.64 | 2.69** | −0.17 | −2.08* | −0.06 | −.66 | 0.33 | 1.43 |

| MED1: Ego-control | −0.97 | −3.87*** | ||||||

| MED2: Emotion regulation | −0.89 | −3.75*** | ||||||

| MED1 × MO: Ego-control × Affective dysfunction | −0.31 | −1.33 | ||||||

| MED2 × MO: Emotion regulation × Affective dysfunction | −0.19 | −.84 | ||||||

Note: IV = independent variable; MO = moderator; MED1 = first mediator; MED2 = second mediator; BPS = borderline personality symptoms; EGO = ego-control; EMOT = emotion regulation; b = unstandardized beta. Each regression analysis controlled for depression and anxiety symptoms and delinquent behaviors (parameters not shown).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

As shown in Table 4, findings provided no evidence of mediated moderation, suggesting that the effect of the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking on childhood borderline personality symptoms is not mediated by ego-control or emotion regulation deficits.

Post-hoc Analyses

To explore whether the factors associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms differ for girls and boys, the analyses described above were conducted again among girls and boys separately.

Girls

Results indicate that the personality traits significantly predicted borderline personality symptoms among girls, FΔ(2, 113) = 49.92, p < .001, with both affective dysfunction and sensation seeking accounting for a significant amount of unique variance in borderline personality symptoms (see Table 5). Moreover, the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking accounted for a significant amount of additional variance in borderline personality symptoms above and beyond the main effects of these traits (FΔ[1, 112] = 7.22, p < .01; see Table 5). Consistent with findings for the sample as a whole, analyses examining the nature of this interaction effect revealed that the relationship between sensation seeking and borderline personality symptoms increased in magnitude as affective dysfunction moved from low (b = .09, ns), to medium (b = .72, p < .05), to high (b = .1.36, p < .001).

Table 5.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Examining the Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation and Ego-Control in the Relationship between Sensation Seeking and Affective Dysfunction (and their Interaction) and Childhood Borderline Personality Symptoms for Girls and Boys Separately.

| Girls (n = 118) |

Boys (n = 145) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | b (SE) | R2 (Adj) | R2Δ | F | β | b (SE) | R2 (Adj) | R2Δ | F | |

| Step 1 | .06 (.05) | .06* | 3.79* | .01 (.00) | .01 | 1.03 | ||||

| Depression/anxiety | .13 | .03 (.02) | .12 | .03 (.02) | ||||||

| Delinquent behaviors | .17 | .23 (.13) | −.01 | −.02 (.12) | ||||||

| Step 2 | .50 (.48) | .44*** | 28.47*** | .60 (.59) | .58*** | 51.83*** | ||||

| Depression/anxiety | .00 | .00 (.02) | .10 | .03 (.02) | ||||||

| Delinquent behaviors | .01 | .01 (.10) | −.01 | −.02 (.09) | ||||||

| Sensation seeking | .19** | .74 (.28) | .08 | .37 (.28) | ||||||

| Affective dysfunction | .64*** | 2.45 (.26) | .75*** | 3.43 (.25) | ||||||

| Step 3 | .53 (.51) | .03** | 25.48*** | .60 (.58) | .00 | 41.24*** | ||||

| Depression/anxiety | .04 | .01 (.02) | .10 | .03 (.02) | ||||||

| Delinquent behaviors | −.01 | −.02 (.09) | −.01 | −.02 (.09) | ||||||

| Sensation seeking | .19** | .72 (.27) | .08 | .36 (.28) | ||||||

| Affective dysfunction | .63*** | 2.39 (.26) | .75*** | 3.42 (.25) | ||||||

| Sensation seeking × Affective dysfunction | .18** | .64 (.24) | .02 | .09 (.22) | ||||||

| Step 4 | .63 (.61) | .10*** | 27.21*** | .68 (.66) | .08*** | 40.69*** | ||||

| Depression/anxiety | .01 | .00 (.01) | .06 | .02 (.01) | ||||||

| Delinquent behaviors | −.03 | −.04 (.08) | .01 | .01 (.08) | ||||||

| Sensation seeking | .19** | .74 (.24) | .00 | .01 (.27) | ||||||

| Affective dysfunction | .48*** | 1.84 (.25) | .63*** | 2.89 (.26) | ||||||

| Sensation seeking × Affective dysfunction | .12 | .42 (.22) | .02 | .08 (.20) | ||||||

| Emotion regulation | −.21** | −.80 (.23) | −.09 | −.39 (.25) | ||||||

| Ego-control | −.27*** | −1.03 (.25) | −.31*** | −1.41 (.25) | ||||||

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

As for the relationships between the personality traits (and their interaction) and proposed mediators among girls, results indicate that the personality traits significantly predicted both emotion regulation (R2Δ = .08, FΔ[2, 113] = 4.74, p < .05) and ego-control (R2Δ = .11, FΔ[2, 113] = 7.32, p < .01), above and beyond the covariates. However, only affective dysfunction accounted for a significant amount of unique variance in emotion regulation and ego-control (βs = −.29 and −.33, respectively, ps < .01); sensation seeking was not uniquely associated with emotion regulation (β = .06, p > .10) or ego-control (β = −.04, p > .10). Moreover, contrary to the findings for the sample as a whole, the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking accounted for a significant amount of additional variance in ego-control among girls (R2Δ = .03, FΔ[1, 112] = 4.33, p < .05). The interaction term was not significantly associated with emotion regulation (R2Δ = .00, FΔ[1, 112] = .43, p > .10).

With regard to the mediating roles of emotion regulation and ego-control in borderline personality symptoms among girls, results of a hierarchical regression analysis indicate that both emotion regulation and ego-control emerged as unique predictors of borderline personality symptoms among girls (see Table 5, Step 4), accounting for an additional 10% of the variance in these symptoms (FΔ[2, 110] = 15.30, p < .001). Further, although affective dysfunction remained a significant predictor of borderline personality symptoms with the proposed mediators in the equation, findings that the indirect effects of affective dysfunction on childhood borderline personality symptoms through its effects on both emotion regulation (z = 2.23, p < .05) and ego-control (z = 2.98, p < .01) were significant provide evidence for partial mediation.

As described above, we also conducted a series of regression analyses to test for the presence of mediated moderation among girls. As shown in Table 4 (lower panel), findings provide support for the presence of mediated moderation among girls, indicating that the sensation seeking X affective dysfunction interaction on borderline personality symptoms is mediated by deficits in ego-control (but not by deficits in emotion regulation). Specifically, the 2ai condition for mediated moderation was met by the findings of a significant interaction between sensation seeking and affective dysfunction in the prediction of ego-control (see Table 4, lower panel, equation 2), with post-hoc analyses revealing that the relationship between sensation seeking and ego-control deficits (in the form of under-control) decreased in magnitude as affective dysfunction moved from high (b = −.20, p = .09), to medium (b = −.03, p > .10), to low (b = .13, p > .10). Further, the other conditions of mediated moderation were met by findings of a significant main effect of ego-control on borderline personality symptoms (when controlling for the interactions between affective dysfunction and sensation seeking and between affective dysfunction and ego-control; see Table 4, lower panel, equation 4), as well as findings that the sensation seeking X affective dysfunction interaction effect on borderline personality symptoms reduced in magnitude from equation 1 (b = .64) to equation 4 (b = .33), and was no longer significant in equation 4.

Boys

Results indicate that the personality traits significantly predicted borderline personality symptoms among boys, above and beyond the covariates, FΔ(2, 140) = 101.17, p < .001 (see Table 5). However, only affective dysfunction accounted for a significant amount of unique variance in borderline personality symptoms among boys (see Table 5, Step 2). Moreover, the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking did not account for a significant amount of additional variance in borderline personality symptoms above and beyond the main effects of these traits (FΔ[1, 139] = .16, p > .10; see Table 5, Step 3).

With regard to the relationships between the personality traits and proposed mediators among boys, results indicate that the personality traits significantly predicted both emotion regulation (R2Δ = .18, FΔ[2, 140] = 15.17, p < .001) and ego-control (R2Δ = .12, FΔ[2, 140] = 9.70, p < .001), above and beyond the covariates. Further, both affective dysfunction and sensation seeking accounted for a significant amount of unique variance in emotion regulation (βs = −.33 and −.26 for affective dysfunction and sensation seeking, respectively, ps < .01) and ego-control (βs = −.29 and −.18 for affective dysfunction and sensation seeking, respectively, ps < .05). However, as with the findings for borderline personality symptoms described above, the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking failed to account for additional variance in emotion regulation (R2Δ = .01, FΔ[1, 139] = 1.51, p > .10) or ego-control (R2Δ = .00, FΔ[1, 139] = .22, p > .10) among boys, above and beyond the main effects of these traits.

With regard to the mediating roles of emotion regulation and ego-control in childhood borderline personality symptoms among boys, results of a hierarchical regression analysis indicate that the proposed mediators accounted for an additional 8% of the variance in borderline personality symptoms when controlling for the personality traits (and their interaction) and the covariates (FΔ[2, 137] = 16.43, p < .001). However, only ego-control emerged as a unique predictor of borderline personality symptoms among boys (see Table 5, Step 4). Finally, findings indicate that ego-control partially mediates the relationship between affective dysfunction and borderline personality symptoms among boys. Specifically, although affective dysfunction remained a significant predictor of borderline personality symptoms with ego-control in the equation, computation of the Goodman (I) equation indicated that the indirect effect of affective dysfunction on childhood borderline personality symptoms through its effect on ego-control was significant (z = 3.25, p < .01). Given that the interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking was not significantly associated with borderline personality symptoms among boys, further analyses examining mediated moderation were not conducted for boys.

Discussion

Recent findings highlighting the early developmental origins of BPD have underscored the need to examine the emergence of borderline personality pathology in children (Crick et al., 2005; Paris, 2005). Although childhood borderline personality symptoms are expected to take variable pathways into adulthood (ranging from resilience to pathology), the presence of these symptoms may, for some children, be indicative of risk for later BPD. Therefore, studies examining the factors associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms may facilitate the identification of children at risk for the later development of borderline personality pathology, as well as provide a better understanding of the pathogenesis of BPD per se. The goal of the current study was to examine the relationships between two core BPD-relevant personality traits (affective dysfunction and disinhibition), self- and emotion- regulation deficits, and childhood borderline personality symptoms among a sample of children aged 9 to 13.

Consistent with past research (Goldman et al., 1992; Guzder et al., 1996; Zelkowitz et al., 2001), results provided support for the applicability of extant models of the pathogenesis of BPD among adults to the emergence of borderline personality pathology among children. In particular, findings suggest that the same traits and mediators theorized to be central to the pathogenesis of BPD in adulthood are likewise associated with childhood borderline personality symptoms. Specifically, evidence was provided for the unique roles of both sensation seeking (one dimension of the trait of disinhibition) and affective dysfunction in childhood borderline personality symptoms. Moreover, consistent with extant theoretical models of the development of BPD (e.g., Paris, 2005), results provided support for the hypothesized interaction of affective dysfunction and sensation seeking in childhood borderline personality symptoms. Specifically, although sensation seeking was related to borderline personality symptoms among children with at least average levels of trait affective dysfunction, it was not related to borderline personality symptoms among children with lower than normal levels of affective dysfunction.

Support was also provided for the role of both self- and emotion-regulation deficits in childhood borderline personality symptoms. Each of these proposed mediators was uniquely associated with borderline personality symptoms, suggesting that deficits in the ability to modulate emotional arousal and control impulsive behaviors (within and outside of the context of emotional distress) are associated with the emergence of borderline personality pathology in children. Further, results suggest that affective dysfunction may increase the risk for deficits in each of these areas, interfering with the development of self- and emotion-regulation capacities and partially accounting for the relationship between affective dysfunction and childhood borderline personality symptoms. Contrary to expectations, neither of these putative mediators explained the main effect of sensation seeking on borderline personality symptoms. As such, results suggest that the relationship between sensation seeking and childhood borderline personality symptoms may be less about the inability to control behaviors, inhibit impulses, and/or modulate emotional arousal, and more about a proclivity for or interest in novel or stimulating stimuli. For example, sensation seeking may increase the risk for borderline personality symptoms by creating an interest in novel sensory experiences (and thereby motivating exploratory behaviors; Collins, Litman, & Spielberger, 2004) or resulting in an underestimation of the risk associated with specific behaviors or activities (Rosenbloom, 2003). Future research is needed to continue to identify the potential mechanisms and developmental processes that may underlie the relationship between this aspect of disinhibition and childhood borderline personality symptoms.