Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effects of postnatal dexamethasone treatment (DEX) on aerobic fitness and physical activity levels in school-age children born with very low birth weight (VLBW)

Study design

Follow-up study of 65 VLBW infants who participated in a randomized controlled trial of DEX to reduce ventilator dependency. Aerobic fitness was determined from peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) with a cycle ergometer. Habitual physical activity was assessed by questionnaire.

Results

A trend for a treatment with chronic lung disease diagnosis (CLD) interaction was found with children in the Placebo group with CLD having the lowest VO2peak (p=.09). Fifty-three % of the DEX group and 48% of the Placebo group had reduced fitness. No group differences were found for physical activity. Parental reports suggested that nearly two-thirds of children participated in <1 hour per week of vigorous physical activity which was partially explained by decreased larger airway function (r=0.30, p=0.03).

Conclusions

We found no adverse effect of postnatal DEX on aerobic fitness or habitual physical activity at school-age. However, the reduced fitness and physical activity levels emphasize the need for closer follow-up and early interventions promoting physical activity to reduce risk of chronic disease in this at-risk population.

In the United States, 1.5 % of all births are very low birth weight (VLBW) (< 1501 grams).(1) These infants commonly require mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen to survive, and approximately 19-23% develop chronic lung disease (CLD).(2) In childhood and adolescence, prematurity and VLBW were associated with reduced pulmonary function(3, 4) and exercise tolerance (5, 6) with some evidence of greater reductions observed in those diagnosed with CLD.(3, 4, 7, 8) Postnatal treatment with corticosteroids in the first few weeks of life reduces the duration of ventilator and supplemental oxygen dependence, and the incidence of CLD during infancy(9). We reported less airway obstruction in school-age children born with VLBW who were treated postnatally with the corticosteroid, dexamethasone (DEX).(10) Despite these benefits, early exposure to corticosteroids also was associated with impaired growth and neurological outcomes in VLBW children,(9, 11) as well as alterations in skeletal muscle development (in a rat model),(12) all of which may affect aerobic fitness and physical activity participation, and consequently, long-term health.(13) Therefore, the primary aim of this follow-up study was to examine the effects of postnatal DEX exposure on aerobic fitness and physical activity in a cohort of school-aged children, born prematurely with VLBW, who participated in a randomized controlled trial DEX therapy as neonates. A second aim was to determine if the beneficial effects of DEX on pulmonary function were associated with better aerobic fitness and greater physical activity participation.

METHODS

Participants were 8-to-11 year-old children who were born prematurely between 1992 and 1995 and participated as neonates in a randomized controlled trial of a 42-day tapering course of DEX to reduce the duration of ventilator dependence.(14) Eligibility criteria for the neonatal trial included: 1) birth weight <1501g; 2) age, 15 to 25 days; 3) ventilator dependence without improvement; 4) absence of clinical signs of sepsis; and 5) absence of patent ductus arteriosus by echocardiography. The treatment group received DEX at an initial dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day that was tapered over 42 days, whereas the control group received a placebo. Additional details regarding the randomized trial are described in detail elsewhere. (14) The follow-up evaluation included testing of both cognitive and physical outcomes, the latter including pulmonary function and exercise testing for which the children had to be free of any health contraindications to exercise testing. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and Forsyth Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian, and written assent was obtained from the child.

The child was evaluated at the General Clinical Research Center at the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center. Height and weight were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, and age- and sex-specific percentiles and z-values were determined from the National Center for Health Statistics Centers for Disease Control 2000 reference values.(15)

The pulmonary function methods and results have been previously reported.(10) In view of our previous finding of group differences in the prevalence of larger airway obstruction, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) expressed as a percent of predicted was chosen to examine the association of pulmonary function with aerobic fitness and physical activity.

Aerobic fitness was assessed via a progressive, exercise test on an electronically-braked cycle ergometer (Corival). The work rate was set at “0” watts for the first minute and then increased according to the Godfrey Protocol by 10, 15, or 20 Watts each minute based on the height of the child (<125, 125-150, and >150 cm, respectively).(16) Expired gases were collected and analyzed using a CPX Med Graphics metabolic cart (St. Paul, MN). Aerobic fitness was determined from the highest 15-second average of oxygen uptake attained (VO2peak) and expressed relative to body weight (ml·kg-1·min-1) and as a percentage of age- and sex-specific reference values.(17) Subjects were verbally encouraged to give a maximal effort. Subject’s effort was considered to be maximal if: 1) peak heart rate was >195 beats per minute; 2) the peak respiratory exchange ratio was > 1.05; and/or 3) opinions of two experienced testers agreed that a maximal effort was given.

Habitual physical activity was assessed using Kriska’s Modifiable Activity Questionnaire(18), which was shown to be both valid and reliable in other pediatric populations.(18, 19) Because of the relatively young age of the children, the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire was administered to the parent with the child present. The parent was read a list of common leisure activities and asked to indicate the activities in which the child had engaged at least five times in the past year. Activities not included on the list could be added by the parent. For indicated activities, the parent was then asked to provide information on the number of months performed in the past year, average number of days per month, and the average duration for each day. The total hours of activity were summed and expressed as an average total hours of activity per week for the past year (TOT-hrs·wk-1). The activities with an estimated intensity > 6 METs(20) were summed and expressed as average hours per week spent in vigorous physical activity (VIG-hrs·wk-1).

Neonatal information was reported previously (10,24). A diagnosis of CLD was defined as the use of supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks post-menstrual age.(22) All testers, children, and their parents were blinded to treatment assignment.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0. Descriptive statistics were used to examine measures of central tendency and dispersion. Between-group comparisons were made using t-tests for data that were normally distributed, and Mann-Whitney U tests for data that were not. Power analysis indicated that with our sample size, we had 80% power to detect a significant (p=0.05) group difference in VO2peak of 14% (two-tailed). Chi-square analysis was used to compare proportions. Correlations among pulmonary function, aerobic fitness, and physical activity were determined using Spearman rank-order correlational analysis.

RESULTS

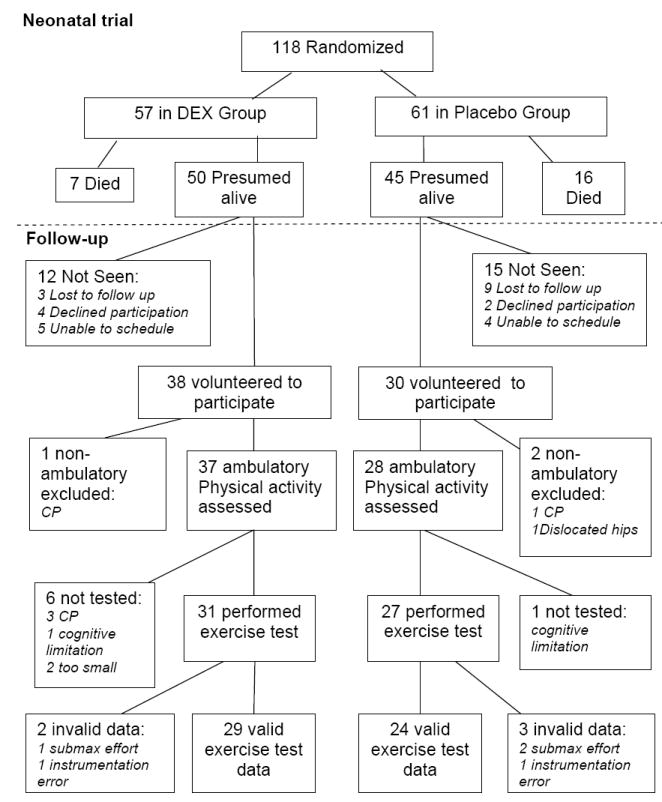

In the postnatal DEX trial, 118 infants were randomized and 95 survived to one year of age (Figure 1). Twelve of the presumed survivors (3 DEX, 9 placebo) could not be located. Sixty-eight of 95 survivors (38 DEX, 30 Placebo) volunteered to participate and were enrolled in the follow-up study of physical and cognitive outcomes at 8 -11 years of age.

Figure 1.

Follow-up details of postnatal randomized controlled trial of DEX.

Neonatal characteristics of the 68 volunteers did not differ significantly from the 27 children who were not evaluated at 8 -11 years of age. Data were excluded from analyses for three children (1 DEX, 2 Placebo) who were not ambulatory due to severe cerebral palsy (1 DEX and 1 Placebo) and one child with bilateral dislocated hips (Placebo) and for whom exercise testing was not possible and the physical activity questionnaire was deemed unsuitable. Characteristics for the remaining 65 children are presented in Table I. Fifty-two % of the DEX group and 49% of the Placebo group were male. Thirty-seven % of the DEX group and 58% of the Placebo group were non-white. Chi-square analysis revealed that a greater proportion of the Placebo group had chronic lung disease (CLD) during infancy as well as below normal larger airway function (FEV1 < 80% of predicted) at follow-up compared with the DEX group. No group differences were found for the other neonatal or anthropometric characteristics at follow-up.

Table 1.

Participants’ current and neonatal characteristics by postnatal treatment group. Values are median (5th, 95th percentile) or proportion.

| DEX n = 37 | Placebo n = 28 | |

|---|---|---|

| Current Characteristics | ||

| Age at follow-up, yrs | 9.3 (8.0,10.9) | 9.3 (8.2, 10.9) |

| Weight z-value | 0.310 (-1.933, 2.331) | -0.405 (-2.624, 3.051) |

| Height z-value | 0.050 (-2.450, 1.941) | -0.125 (-2.741, 2.684) |

| BMI percentile | 64 (8, 98) | 50 (1, 99) |

| FEV1, % predicted | 83 (48, 107) | 77 (52, 115) |

| FEV1 < 80% predicted, % | 40† | 60 |

| Neonatal Characteristics | ||

| Birth weight, g | 732 (527, 1182) | 789 (553, 1298) |

| Birth weight z-value | -0.138 (-1.155,1.063) | -0.214 (-1.481, 0.662) |

| Gestational age, wks | 25 (23, 28) | 26 (23, 30) |

| CLD+, % | 49* | 71 |

X2 = 4.137, p=0.042;

X2 = 3.406, p=0.065

Aerobic fitness

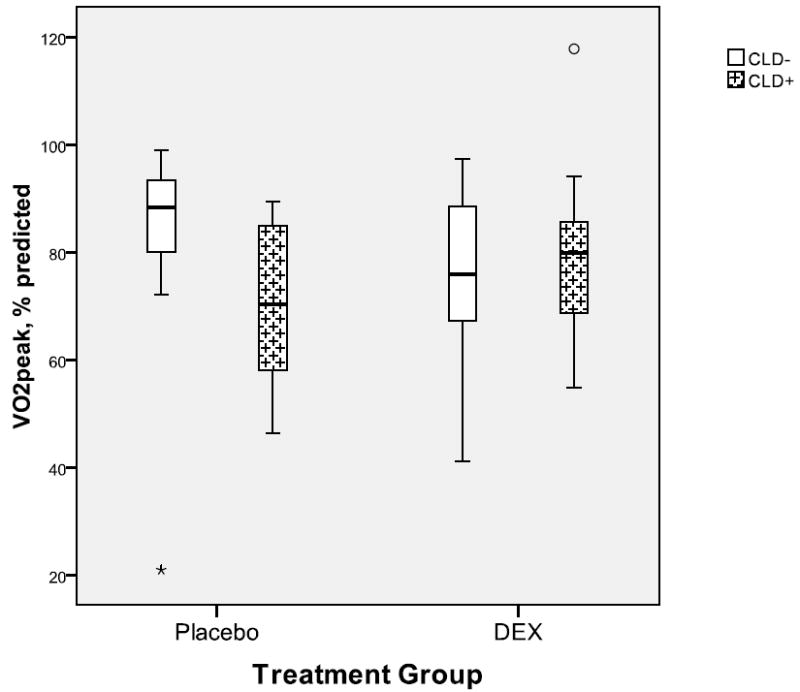

Seven children (6 DEX, 1 placebo) were not able to perform exercise testing due to cerebral palsy (3 DEX), cognitive impairments (1 DEX, 1 placebo), or because leg length was too short to reach the ergometer pedals (2 DEX). Of the 58 children who performed exercise tests, data of three subjects were excluded (1 DEX, 2 Placebo) for failing to meet criteria for a maximal effort, and data of two subjects (1 DEX, 1 Placebo) were excluded due to instrumentation errors. The exercise test results of the remaining 53 children are presented in Table II. Peak VO2 values were quite variable with some participants having values well above age- and sex-specific reference values. Approximately half of the participants in both groups had VO2peak values less than 80% of predicted, but no treatment group differences were found for VO2peak when expressed relative to body mass or as a percent of predicted. However, when treatment groups were stratified by CLD status (Figure 2), there was a trend (p=0.09) for a treatment with CLD group interaction. Peak VO2 tended to be lower in the CLD+ (72%) vs. CLD- (82%) in the Placebo group, whereas no differences were observed between CLD+ (81%) and CLD- (75%) groups in the DEX group.

Table 2.

Aerobic fitness and habitual physical activity levels by Treatment groups. Values are medians (5th, 95th percentiles).*

| DEX | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| VO2peak, ml·kg-1·min-1 | 38.1 (22.3, 52.8) | 39.1 (13.8, 52.3) |

| VO2peak, % predicted | 78 (43, 108) | 79 (27, 99) |

| VO2peak < 80% of predicted | 53% | 48% |

| Tot-hrs·wk-1 | 6.4 (1.0, 23.4) | 6.8 (0.3, 24.3) |

| Vig-hrs·wk-1 | 0.5 (0, 6.7) | 0.8 (0, 7.4) |

All between-group comparisons were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Boxplots showing aerobic fitness for treatments groups by CLD status. There was a trend (p=0.09) for an interaction with the participants who received Placebo and had CLD having the lowest fitness.

Physical activity

Habitual physical activity for the past year was assessed in 65 (37 DEX, 28 placebo) children who were all ambulatory without assistance. As shown in Table II, average Tot-hrs·wk-1 and VIG-hrs·wk-1 did not differ significantly between treatment groups. Based on parents’ reports, 61% of the Placebo group and 68% of the DEX group engaged in less than 1 hour of vigorous activity (>6 METs) per week, with no group differences in proportions. Stratification by CLD status revealed no significant differences between CLD- and CLD+ groups nor any interaction with treatment group for either Tot-hrs·wk-1 or Vig-hrs·wk-1 for the past year. The analyses were repeated excluding the data of the children who did not have exercise test results, and the lack of group differences remained.

Correlational analysis

In view of the group differences in larger airway function, Spearman correlational analysis was performed to examine the associations between FEV1 % predicted and measures of aerobic fitness and physical activity. No significant correlations were found between FEV1 % predicted and aerobic fitness or TOT·wk-1, however, FEV1 % predicted was significantly correlated with average hours spent per year participating in vigorous physical activity (r= 0.30, p=0.03).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated aerobic fitness and physical activity in children born prematurely with VLBW who participated in a postnatal randomized controlled trial of dexamethasone to reduce ventilator dependency. The study revealed no adverse effects of postnatal dexamethasone treatment on aerobic fitness or physical activity levels. Our findings are important in light of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Canadian Pediatric Society’s recommendation against “routine use of systemic DEX for the prevention or treatment of chronic lung disease,” and need for additional long-term follow-up of well designed, randomized, double-blind, controlled trials with no crossover or contamination of treatment.(23)

There was a trend for the children with a neonatal diagnosis of CLD who received placebo to have lower fitness which is consistent with some,(7, 8) but not all(5, 6, 24) of the previous studies comparing fitness in prematurely born children with and without a history of CLD. In contrast, there was no difference in fitness in children with and without CLD who were treated with DEX. A possible explanation for this finding is that DEX decreased the severity of CLD such that among DEX-treated children, most cases of CLD were so mild that fitness was not affected by lung function.(22) It is also possible that DEX may have adversely affected non-pulmonary determinants of aerobic fitness, such as skeletal muscle development and function. The lack of correlation between FEV1 % predicted and VO2peak suggests that fitness was not limited by larger airway obstruction in this sample. However, Mitchell and Teague(25) reported that despite no difference in FEV1, CLD survivors had significantly lower diffusion capacity and cardiac output during exercise than their preterm peers without CLD who in turn had reduced values compared with term-born peers. Consequently, the effects of CLD on fitness may be evident in cardiopulmonary measures not assessed in this study.

A disconcerting finding was that nearly half of the children in both groups had fitness levels below 80% of predicted based on sex- and age-specific reference values. Lower fitness may be attributed to several factors. Persons with lower birth weight was reported to have lower fat-free mass, and thus less muscle mass for exercise, when compared with their higher birth weight peers. (8, 26, 27) Based on previous research,(11) we expected growth to be impaired, particularly in the DEX-exposed children. Surprisingly, the mean weight z-score and BMI percentile of the DEX group were above average (weight z-score>0 and BMI.>50th percentile) although they did not differ significantly from the means of the Placebo group. Body composition was not assessed so it is not clear if the lower fitness can be attributed to less muscle mass in this sample.

Qualitative aspects of muscle mass are also important for aerobic fitness. Premature birth and undernutrition may alter normal skeletal muscle development with fiber diversification occurring in the last trimester of gestation and continuing into the postnatal period.(28) Reduced muscle high energy phosphate reserves at rest, and greater depletion with reflex-induced exercise, were observed in VLBW infants compared with infants with higher birth weights (>2000 g) using NMR spectroscopy;(29) however, it is not known if these differences persist beyond the neonatal period. Further qualitative and longitudinal examination of muscle fiber composition may provide explanations for the lower aerobic fitness levels and provide insight into the effects that early life exposures may have on developing skeletal muscle.

The results of this study also revealed no adverse effects of DEX exposure on physical activity levels. Although questionnaire data are subject to recall error and bias and, at best, moderately correlated to objective measures of physical activity, the parental reports suggest that approximately two-thirds of participants in both groups engaged in less than 1 hour of vigorous activity (>6 METs) per week) which is also concerning and may contribute to the lower fitness levels.(30) The lower fitness may in turn limit the child’s ability to engage in physical activities particularly vigorous activities associated with sports. Two studies(31, 32) comparing persons born with extremely low birth weight (ELBW) to their normal birth weight (NBW) peers revealed similar results. Saigal et al(32) found that young adults with ELBW were less likely to report regular participation in sports and strenuous activities (38% vs 59%; p=.001) compared with their NBW peers, and their scores for physical self-efficacy and perceived physical ability were also significantly lower. Likewise, Rogers et al(31) found that ELBW teens reported less frequent participation in physical activity than their NBW peers, and also reported being less coordinated. Other studies report motor dysfunction or impaired coordination in prematurely born children.(33) Our data also suggest that reduced participation in vigorous physical activity is associated with larger airway obstruction, and these children are also at greater risk for asthma,(34) exercise-induced bronchoconstriction(35) and visual problems,(33) all of which may affect their ability or confidence in their ability to participate in physical activities. Furthermore, parents may perceive their child as being vulnerable(36) and thus may discourage participation in physical activities. The importance of aerobic fitness and regular participation in physical activity is well-documented for the health benefits associated with lower blood pressure and insulin resistance in children,(37) as well as for decreasing risk for development of CVD, hypertension, and other chronic diseases in adulthood.(13) These findings are particularly important for children born prematurely with VLBW whose risk for developing cardiometabolic disease is already increased compared with their term-born, normal birth weight peers.(38-40)

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Ms. Alice Scott, RN, the GCRC staff, and the participants and their families for their dedication to the study.

Supported in part by the General Clinical Research Center of Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center (M01-RR07122), National Institutes of Health (P01HD047584), the Intramural Research Support Committee of Wake Forest Medical School, and the Brenner Center for Child and Adolescent Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- VLBW

Very low birth weight

- CLD

Chronic lung disease

- DEX

Dexamethasone

- VO2peak

Peak oxygen uptake

- TOT-hrs·wk-1

Average total hours per week of physical activity

- VIG-hrs·wk-1

Average hours per week of vigorous physical activity

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Report; Hyattsville, MD: 2009. Mar 18, Births: Preliminary data for 2007. Report No.: Web release; vol 57 no 12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, Stoll BJ, et al. Very low birth weight outcomes of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, January 1995 through December 1996. Pediatrics. 2001 Jan;107(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e1. art-e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle LW, Cheung MM, Ford GW, Olinsky A, Davis NM, Callanan C. Birth weight <1501 g and respiratory health at age 14. Arch Dis Child. 2001 Jan;84(1):40–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korhonen P, Laitinen J, Hyodynmaa E, Tammela O. Respiratory outcome in school-aged, very-low-birth-weight children in the surfactant era. Acta Paediatr. 2004 Mar;93(3):316–21. doi: 10.1080/08035250410023593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vrijlandt EJ, Gerritsen J, Boezen HM, Grevink RG, Duiverman EJ. Lung function and exercise capacity in young adults born prematurely. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Apr 15;173(8):890–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1140OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilbride HW, Gelatt MC, Sabath RJ. Pulmonary function and exercise capacity for ELBW survivors in preadolescence: effect of neonatal chronic lung disease. J Pediatr. 2003 Oct;143(4):488–93. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00413-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santuz P, Baraldi E, Zaramella P, Filippone M, Zacchello F. Factors Limiting Exercise Performance in Long-Term Survivors of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1995 Oct;152(4):1284–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.4.7551383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pianosi PT, Fisk M. Cardiopulmonary exercise performance in prematurely born children. Pediatr Res. 2000 May;47(5):653–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halliday HL, Ehrenkranz RA, Doyle LW. Late (>7 days) postnatal corticosteroids for chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001145.pub2. CD001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nixon PA, Washburn LK, Schechter MS, O’Shea TM. Follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial of postnatal dexamethasone therapy in very low birth weight infants: effects on pulmonary outcomes at age 8 to 11 years. J Pediatr. 2007 Apr;150(4):345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh TF, Lin YJ, Lin HC, Huang CC, Hsieh WS, Lin CH, et al. Outcomes at School Age after Postnatal Dexamethasone Therapy for Lung Disease of Prematurity. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar 25;350(13):1304–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiss JE, Wright JC, Cox NR. Effects of perinatal high dose dexamethasone on skeletal muscle development in rats. Can J Vet Res. 1989 Jan;53(1):17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair SN, Horton E, Leon AS, Lee IM, Drinkwater BL, Dishman RK, et al. Physical activity, nutrition, and chronic disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996 Mar;28(3):335–49. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kothadia JM, O’Shea TM, Roberts D, Auringer ST, Weaver RG, III, Dillard RG. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of a 42-Day tapering course of dexamethasone to reduce the duration of ventilator dependency in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1999 Jul;104(1 Pt 1):22–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000 Jun 8;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godfrey S. Exercise Testing in Children. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krahenbuhl GS, Skinner JS, Kohrt WM. Developmental aspects of maximal aerobic power in children. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1985;13:503–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aaron DJ, Kriska AM, Dearwater SR, Cauley JA, Metz KF, LaPorte RE. Reproducibility and validity of an epidemiologic questionnaire to assess past year physical activity in adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Jul 15;142(2):191–201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF. Habitual physical activity in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Jan;33(1):30–5. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000 Sep;32(9 Suppl):S498–S504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003 Jul 8;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shennan AT, Dunn MS, Ohlsson A, Lennox K, Hoskins EM. Abnormal pulmonary outcomes in premature infants: prediction from oxygen requirement in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1988 Oct;82(4):527–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Postnatal corticosteroids to treat or prevent chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2002 Feb;109(2):330–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker M, Merz U, Hertl MS, Helmann G. School-Age Lung Function and Exercise Capacity in Former Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2003;15:44–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell SH, Teague WG. Reduced gas transfer at rest and during exercise in school-age survivors of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 May;157(5 Pt 1):1406–12. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9605025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers I. The influence of birthweight and intrauterine environment on adiposity and fat distribution in later life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Jul;27(7):755–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Euser AM, Finken MJ, Keijzer-Veen MG, Hille ET, Wit JM, Dekker FW. Associations between prenatal and infancy weight gain and BMI, fat mass, and fat distribution in young adulthood: a prospective cohort study in males and females born very preterm. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):480–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colling-Saltin AS. Some quantitative biochemical evaluations of developing skeletal muscles in the human foetus. J Neurol Sci. 1978 Dec;39(2-3):187–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(78)90122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertocci LA, Mize CE, Uauy R. Muscle phosphorus energy state in very-low-birth-weight infants: effect of exercise. Am J Physiol. 1992 Mar;262(3 Pt 1):E289–E294. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.3.E289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kriemler S, Zahner L, Schindler C, Meyer U, Hartmann T, Hebestreit H, et al. Effect of school based physical activity programme (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in primary schoolchildren: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c785. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers M, Fay TB, Whitfield MF, Tomlinson J, Grunau RE. Aerobic capacity, strength, flexibility, and activity level in unimpaired extremely low birth weight (<or=800 g) survivors at 17 years of age compared with term-born control subjects. Pediatrics. 2005 Jul;116(1):e58–e65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Boyle M, Paneth N, Pinelli J, Streiner D, et al. Comparison of current health, functional limitations, and health care use of young adults who were born with extremely low birth weight and normal birth weight. Pediatrics. 2007 Mar;119(3):e562–e573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vohr BR, Msall ME. Neuropsychological and functional outcomes of very low birth weight infants. Semin Perinatol. 1997 Jun;21(3):202–20. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(97)80064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palta M, Sadek-Badawi M, Sheehy M, Albanese A, Weinstein M, McGuinness G, et al. Respiratory symptoms at age 8 years in a cohort of very low birth weight children. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Sep 15;154(6):521–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kriemler S, Keller H, Saigal S, Bar-Or O. Aerobic and lung performance in premature children with and without chronic lung disease of prematurity. Clin J Sport Med. 2005 Sep;15(5):349–55. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000180023.44889.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen EC, Manuel JC, Legault C, Naughton MJ, Pivor C, O’Shea TM. Perception of child vulnerability among mothers of former premature infants. Pediatrics. 2004 Feb;113(2):267–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr. 2005 Jun;146(6):732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonamy AK, Bendito A, Martin H, Andolf E, Sedin G, Norman M. Preterm birth contributes to increased vascular resistance and higher blood pressure in adolescent girls. Pediatr Res. 2005 Nov;58(5):845–9. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000181373.29290.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalziel SR, Parag V, Rodgers A, Harding JE. Cardiovascular risk factors at age 30 following pre-term birth. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Aug;36(4):907–15. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doyle LW. Cardiopulmonary outcomes of extreme prematurity. Semin Perinatol. 2008 Feb;32(1):28–34. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]