Abstract

In this perspective article, I outline my group’s research involving the chemical syntheses of medicinally important natural products, exploration of their bioactivity, and development of new asymmetric carbon-carbon bond forming reactions. The article also highlights our approach to molecular design and synthesis of conceptually novel inhibitors against target proteins involved in the pathogenesis human diseases, including AIDS and Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Synthesis, natural products, asymmetric synthesis, asymmetric catalysis, HIV-1 protease inhibitors, β-secretase inhibitors

Introduction

My long-standing interest has been to harness the power of organic synthesis and address the problems of today’s medicine. I envision a broad research program that involves diverse applications of organic synthesis with an emphasis on the exploration of chemistry and biology of natural products as well as development of conceptually novel molecular probes against target peptides and proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of human diseases. Our goal was a strong and vigorous synthetic program that would complement and fuel our hypotheses and molecular design capabilities. I have assembled a multidisciplinary collaboration involving organic chemistry, biology and medicine. This exciting interdisciplinary research endeavor has presented excellent learning opportunities and provided solid ground for teaching and training students in the laboratory.

Synthetic organic chemistry is indeed, an enabling science, particularly when dealing with critical issues of biology and medicine. The advent of sophisticated technologies and advances of molecular biology and techniques, brought unique perspectives to modern research in human health and medicine. For example, the molecular insights derived from our X-ray crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes have greatly advanced our design capabilities. This in turn, led to important new challenges and further opportunities for organic synthesis. The understanding of human diseases at the molecular level, their pathogenesis and mechanism of biological target, led to the possibilities that one could design and develop selective molecular therapeutics for novel treatments. Selectivity may well prove to be one of the most important factors in minimizing toxicity and side effects of treatments.

Bioactive natural products have had dramatic impact in medicine and society.2 They display a seemingly endless structural diversity and are often found only in miniscule quantities. Inspiration from natural products has also brought new perspective to organic synthesis. The last fifty years or so, have witnessed revolutionary progress in natural product isolation, structural elucidation, total syntheses, and biological studies. Many times, I have been asked how I choose my molecular targets. It seems often that it is the unique structural features of molecules such as hapalosin or madumycin that is of first attraction. Sometimes it is the unusual biological properties or mode of action as with laulimalide or pelorusides. Other times, it is the unknown that draws us, as with those compounds nature manufactures in only the tiniest amounts. The study of these rare natural products has motivated our development of new and efficient chemistry for synthesis. Organic synthesis is also at the epicenter of our medicinal research. The design of new molecular probes as well as improvements of selectivity and potency, require the synthesis of stereochemically defined novel structural motifs, scaffolds and functionalities. In this article, we would like to provide a brief overview of our research program which encompasses total syntheses and biological studies of a range of bioactive natural products, the development of new synthetic methodologies, and our perspectives in the design and synthesis of conceptually novel enzyme inhibitors for possible treatment of AIDS and Alzheimer’s disease. In light of our recent review,1 the later part will be reviewed only briefly. Also, it is beyond the scope of this article to include a comprehensive citation of all related natural product syntheses. Only selected references have been included in the context to highlight areas of particular biological or synthetic relevance.

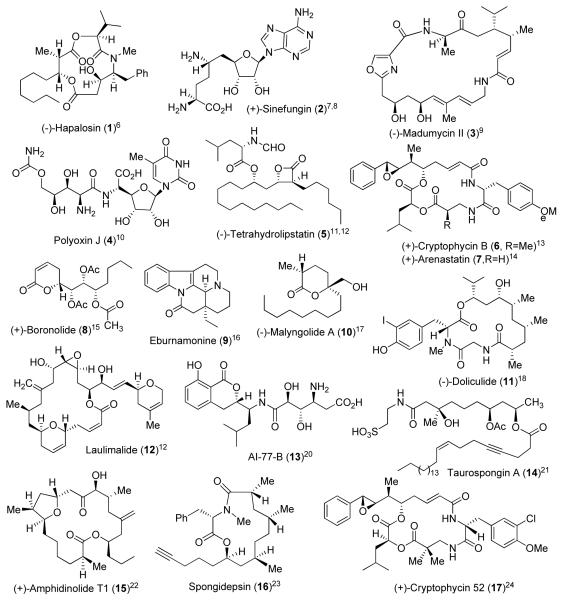

Natural products display an incredible range of structural diversity and often possess intriguing biological properties.2,3 In fact, many of today’s approved drugs are either natural product-derived or have been developed based upon natural product lead structures.4,5 One of our main research objectives is to carry out the synthesis of rare and scarce natural products of biological relevance, then investigate their mode of action to obtain insight. Since our first synthesis of hapalosin (1) in 1996, my laboratory has carried out the synthesis of a range of medicinally important and structurally diverse natural products shown in Figures 1 and 2.6-35

Figure 1.

Bioactive natural product targets synthesized by the Ghosh group, from 1996-2003

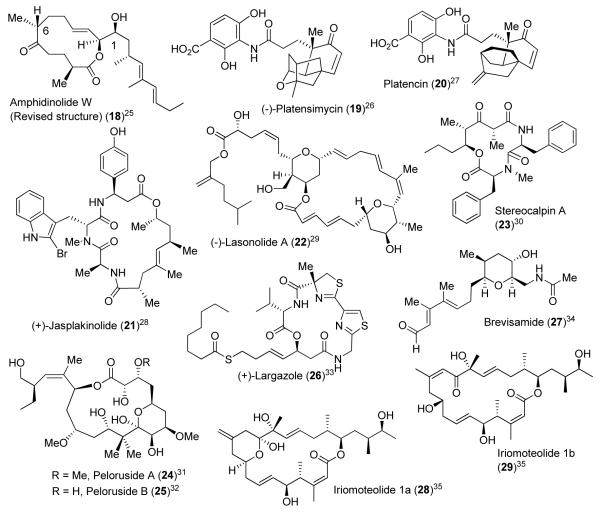

Figure 2.

Bioactive targets synthesized by the Ghosh group, from 2005 – to date

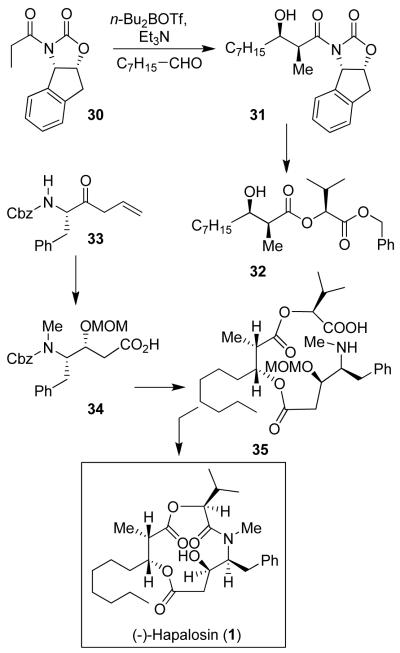

Hapalosin is a cyclodepsipeptide that displays intriguing multidrug-resistance reversing activity by inhibiting P-glycoprotein.36 Our synthesis featured Evans’s asymmetric syn-aldol reaction37 utilizing 1S, 2R-aminoindanol-derived oxazolidinone as the chiral auxiliary.6 As shown in Figure 3, the aldol reaction with chiral imide 30 and n-octanaldehyde provided aldol product 31 in 90% yield as a single diastereomer. A highly diastereoselective synthesis of the statine derivative was carried out by NaBH4 reduction of amino ketone 33 in propanol at 0 °C to provide the corresponding amino alcohol as a mixture (5:1) of diastereomers in 73% yield. This was converted to protected statine derivative 34. Assembly of fragments, cycloamidation, and removal of the protecting groups provided (−)-hapalosin. Other syntheses38 and detailed structure-activity studies of hapalosin were subsequently carried out.39

Figure 3.

Synthesis of (−)-hapalosin (1)

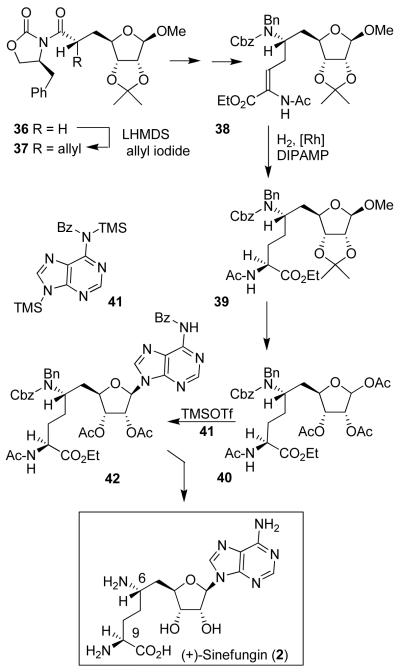

Sinefungin (2) is an interesting nucleoside, with structural similarities to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM).40 Sinefungin exhibits a range of biological activity including antifungal, antiviral, and antiparasitic properties. The biological mechanism of action is related to the inhibition of SAM-dependent methyltransferase enzymes. Despite the intriguing bioactivity, sinefungin could not be used clinically because of its in vivo toxicity, possibly due to its lack of selectivity against MTases.41 Structural modifications may lead to an improvement in selectivity. This has been an active area of investigation by many research groups.42

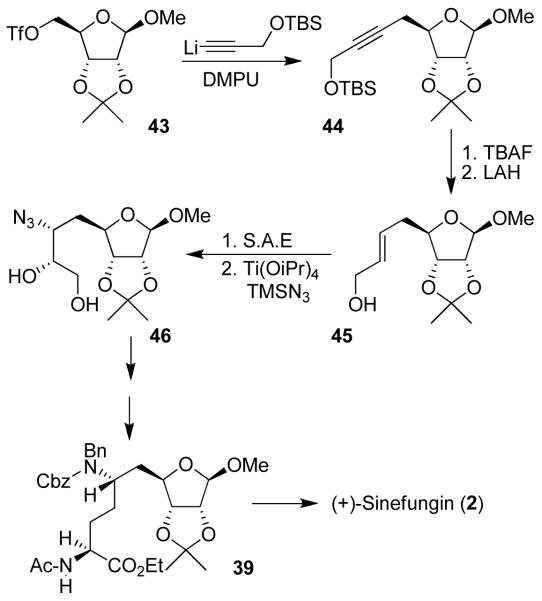

Our synthesis of sinefungin (Figure 4) features a highly diastereoselective alkylation of d-ribose and (1S, 2R)-aminoindanol-derived chiral oxazolidinone 36, to provide 37 in 78% yield as a single diastereomer.7 A Curtius rearrangement installed the C-6 amino stereochemistry. The C-9 amino acid stereochemistry was established by a chiral bis-phosphino-rhodium complex-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation43 of α-acylaminoacrylate derivative 38, providing 39 in 95% yield as a single isomer (98% de) by chiral HPLC analysis. Adenylation of acetate derivative 40 using Vorbruggen’s conditions44 TMSOTf with N6-benzoyladenine 41 provided β-nucleoside 42 in 93% yield. This was then converted to sinefungin after removal of the protecting groups. Additionally, the synthesis provided access to a variety of structural variants of sinefungin. We have also carried out a formal synthesis of sinefungin utilizing an efficient elongation of protected ribose derivative 43.8 As shown in Figure 5, reaction of triflate 43 with an alkylnyllithium reagent in the presence of 1,3-dimethylpropyleneurea (DMPU) provided alkyne derivative 44 in 86% yield. Removal of the TBS group and LAH reduction afforded E-allylic alcohol 45 exclusively. Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation45 followed by regioselective epoxide opening46 provided azidodiol 46, which was converted to sinefungin.

Figure 4.

Synthesis of (+)-sinefungin (2).

Figure 5.

Alternative synthesis of sinefungin (2).

Sinefungin is an inhibitor of MTase and recently a sinefungin-bound X-ray crystal structure of MTase has been determined by collaborators Drs. Dong and Li at the Wadsworth Center in New York.47 The structure provided important molecular insights for designing less toxic and more selective sinefungin-based novel inhibitors. Both syntheses of sinefungin are being utilized for the design and synthesis of the next generation of inhibitors in our laboratories.

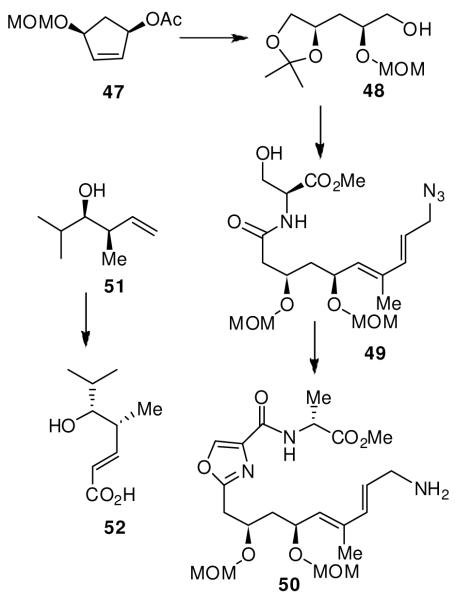

We became interested in madumycin synthesis because of its effectiveness against methicillin-resistant S. aureus or MRSA, a drug-resistant bacteria that is resistant to all current antibiotics except vancomycin. However, vancomycin is burdened with many serious side effects.48 A number of derivatives of madumycin II underwent clinical evaluation.49 We carried out an enantioselective synthesis for the possible preparation of structural analogs, which could not be derived from natural products.9 As shown in Figure 6, the synthesis is highlighted by the development of 1,3-syn-diol segment in enantiomerically pure form utilizing an enzymatic desymmetrization of a cyclopentane meso-diacetate as the key step. Optically active derivative 47 could be prepared in multigram quantities. Ozonolysis followed by NaBH4 reduction and protection of alcohols provided 48, which was conveniently elaborated to 49. Oxazole formation was accomplished using Burgess reagent followed by an oxidation to provide 50. Brown’s asymmetric crotylboration was employed to install the C2 and C3-stereocenters of madumycin.

Figure 6.

Synthesis of the syn-1,3-diol unit of madumycin II

As shown, syn-homoallyl alcohol 51 was obtained in 75% yield and high optical purity (>95% ee). It was converted to acid 52. Coupling of 50 and 52 followed by Yamaguchi macrolactonization of the resulting seco acid provided macrolactone 53. Deprotection of both MOM-protecting groups was carried out by using nBu4N+Br− and dichlorodimethylsilane to provide madumycin II (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Synthesis of madumycin II (3)

Our synthesis of polyoxin J (4) involved a stereoselective m-CPBA-promoted electrophilic epoxidation of ribose-derived allylic alcohol 54 (Figure 8), followed by the regioselective epoxide opening with diisopropoxytitanium diazide using Sharpless’ conditions.46 Azidodiol 56 was converted to polyoxin C (56). The synthesis of 5-O-carbamoyl polyoxamic acid 57 was stereoselectively prepared using Sharpless’ epoxidation45 of a L-tartrate-derived allylic alcohol and a regioselective epoxide-opening46 as the key steps. Coupling of polyoxin C and polyoxamic acid (57) provided polyoxin J (4).

Figure 8.

Synthesis of polyoxin J (4)

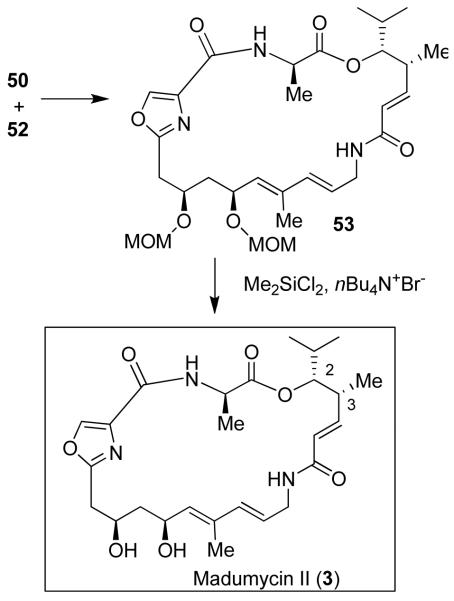

Tetrahydrolipstatin is a saturated derivative of lipstatin, which was isolated from Streptomyces toxytricini in 1987. It is an inhibitor of pancreatic and gastric lipases that are responsible for the digestion of fat from food. In 2003, it was approved by the FDA under the trade name Orlistat® for the treatment of morbid obesity.50 Furthermore, tetrahydrolipstatin is an inhibitor of fatty acid synthase (FAS), an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of fatty acids in many human carcinomas. FAS is required for tumor cell survival and therefore FAS inhibitors have been suggested for cancer chemotherapy.51 Thus, synthesis of tetrahydrolipstatin and analogs have become an important area of research. Our first synthesis of tetrahydrolipstatin (5) was accomplished using our ester-derived titanium enolate-based diastereoselective anti-aldol reaction as the key step.11

As shown in Figure 9, an ester-enolate aldol reaction of 58 with cinnamaldehyde provided aldol product 59 as the major diastereomer (6:1 mixture) in 60% yield which was subsequently converted to aldehyde 60.11 A nitro aldol reaction was employed to append the requisite carbon chain. Nitro alcohol 61 was converted to β-hydroxy ketone 62, which was subjected to an anti-selective reduction using Evans’ protocol52 to provide anti-1,3-diol (diastereoselectivity 22:1). It was then converted to tetrahydrolipstatin 5.

Figure 9.

Synthesis of (−)-tetrahydrolipstatin (5)

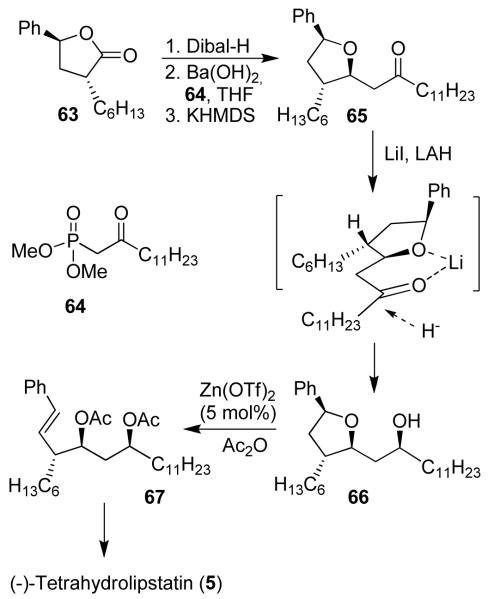

Our recent non-aldol route to anti-aldol segments provided important access to tetrahydrolipstatin and its derivatives.12(b) As shown in Figure 10, alkylated optically active lactone 63 was converted to ketone 65 by DIBAL-H reduction, Horner-Emmons reaction with 64 followed by oxo-Michael reaction to provide 65. A chelation-controlled reduction of 65 afforded syn-alcohol 66 diastereoselectively (17:1, 88% yield). An acyloxycarbenium ion-mediated ring opening reaction with 5 mol% Zn(OTf)2 and Ac2O provided styrene derivative 67, which was converted to tetrahydrolipstatin 5.

Figure 10.

A non-aldol route to (−)-tetrahydrolipstatin (5)

Cryptophycins are a group of compounds that exhibit potent antitumor properties. Cryptophycin B (6) and arenastatin A (7) exhibited IC50 values of 7 pg/mL and 5 pg/mL respectively against KB cell lines.53 Unfortunately, the clinical potential of cryptophycins has been limited due to their degradation in blood caused by the high susceptibility of the ester functionalities to hydrolysis. Therefore, the synthesis of cryptophycin analogs with better in vivo stability warranted significant efforts for the synthesis of cryptophycins and their derivatives. Cryptophycins exhibit antiproliferative and antimitotic activity through their interaction with microtubules.54 One of the synthetic analogs of the cryptophycin class is cryptophycin 52 (17), also known as LY355703, which was hydrolytically stable and very potent against numerous tumor cell lines, underwent clinical development.

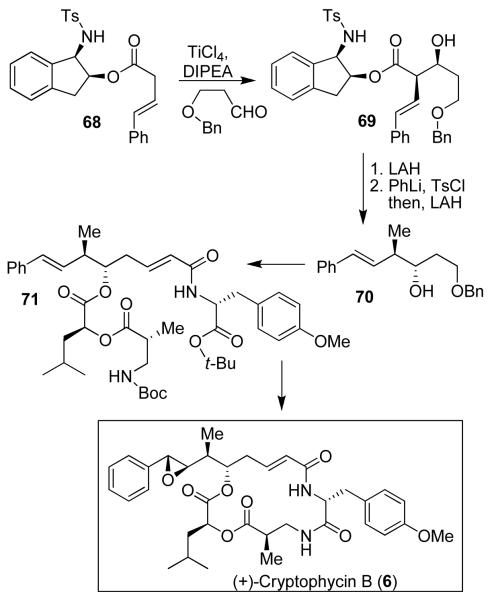

Our synthesis of cryptophycin B utilized a highly diastereoselective ester-derived titanium enolate-based syn-aldol reaction as the key step.13 As shown in Figure 11, aldol reaction of ester 68 with 3-(benzyloxy)propanal afforded syn-aldol product 69 as a single diastereomer in 98% yield. LAH reduction of 69 gave the corresponding alcohol, which was converted to methyl derivative 70 in a one-pot, two-step sequence involving tosylation with PhLi and p-TsCl followed by LAH reduction to provide 70 in 88% overall yield. This was converted to 71 and then to cryptophycin B (6) and arenastatin A (7).14

Figure 11.

Synthesis of (+)-cryptophycin B (6)

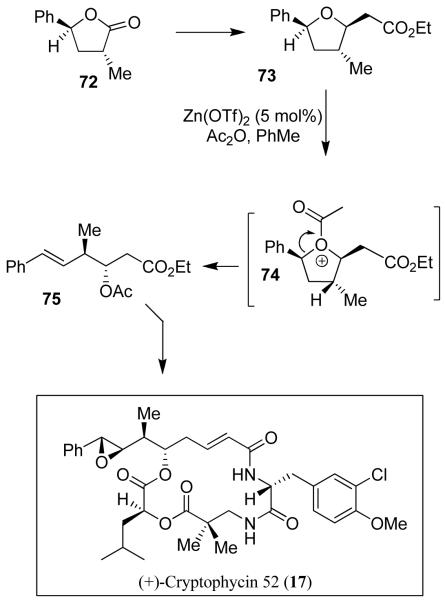

We have also accomplished the synthesis of cryptophycin 52 (17, LY355703) utilizing an asymmetric non-aldol process for anti-aldol variants developed in our laboratory.24 As shown in Figure 12, both stereogenic centers of the key epoxy-octenamide fragment in 17 were introduced by a diastereoselective alkylation of optically active 5-phenyl-γ-butyrolactone 72, prepared utilizing CBS-reduction as the key step.55 Reduction of 72, Horner-Emmons followed by oxo-Michael reactions provided 73 diastereoselectively. An acyloxycarbenium ion (74) mediated ring opening of 73 provided 75, which was converted to cryptophycin 52 (17).

Figure 12.

Synthesis of (+)-cryptophycin 52 (17)

Our subsequent synthetic targets were emetic agent boronolide (8)15, antihypertensive agent eburnamonine (9)16, and antibacterial agent (−)-malyngolide (10).17 These were synthesized to feature various synthetic methodologies developed in our laboratories.

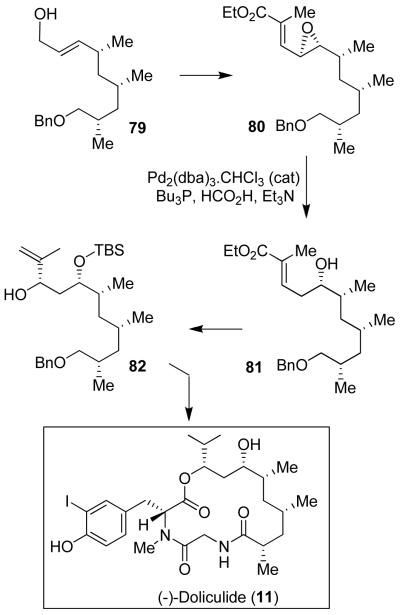

We became interested in the synthesis of doliculide (11) for a number of reasons. Doliculide exhibits exceedingly potent cytotoxicity against HeLa-S3 cells with an IC50 value of 1 ng/mL.56 Yamada and co-workers first reported the isolation, initial cytotoxic properties and synthesis of doliculide.57 However, its biological mechanism of action was not known. We carried out a new convergent synthesis of doliculide and investigated its biological mode of action in collaboration with Ernest Hamel at the National Cancer Institute.

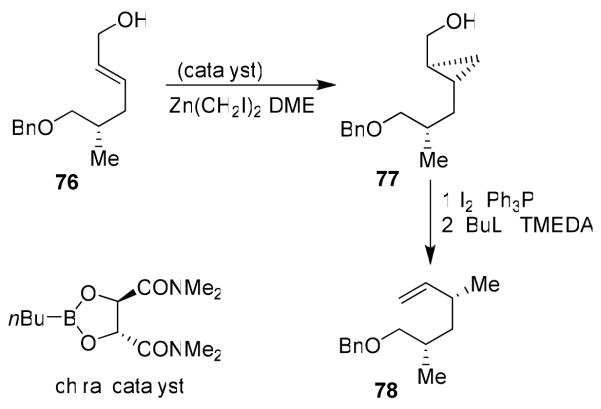

As shown in Figure 13, the synthesis of the 1,3,5-syn/syn trimethyl unit started with 4-benzyloxy-3(S)-methyl-butyronitrile, which was converted to allylic alcohol 76.18 Asymmetric cyclopropanation of 76 using a chiral catalyst provided 77 in excellent yield and high diastereoselectivity (91% de).58 Alcohol 77 was converted to iodide, which upon treatment with nBuLi/TMEDA afforded alkene 78. Iteration of the same protocol furnished allylic alcohol 79 (Figure 14). The 1,3-syn-diol functionality was introduced by Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation45 and regioselective opening of the epoxide as the key steps. The regioselective epoxide opening of 80 using a catalytic amount of Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3 provided anti-alcohol 81, which was further converted to polyketide unit 82 and then to doliculide (11).18

Figure 13.

Stereoselective synthesis of polyketide fragment 78.

Figure 14.

Synthesis of (−)-doliculide (11).

Using synthetic doliculide, we have investigated its biological mechanism of action. It was found that doliculide arrested cells at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle by interfering with normal actin assembly.59 Furthermore, we found that doliculide, like jasplakinolide (21), enhanced the assembly of purified actin and inhibited the binding of FITC2-labeled phalloidin to actin polymer. Treatment of cells with doliculide resulted in the arrest at cytokinesis and caused major rearrangement of intracellular F-actin.59 Structural similarities of doliculide and jasplakinolide led us to suggest that both compounds bind to the same site on F-actin. This finding prompted us to get involved in the synthesis of jasplakinolide (21)28 and provided us an opportunity to design novel doliculide and jasplakinolide-based molecular probes.

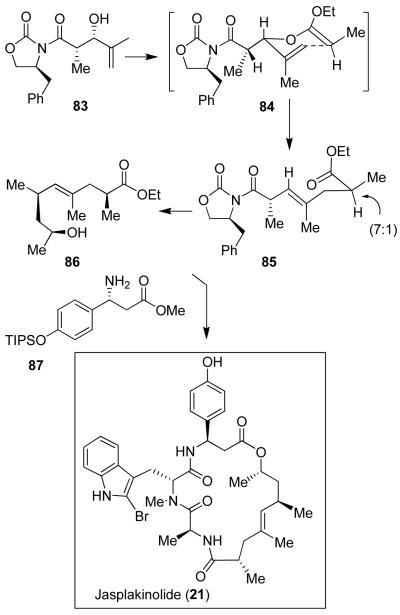

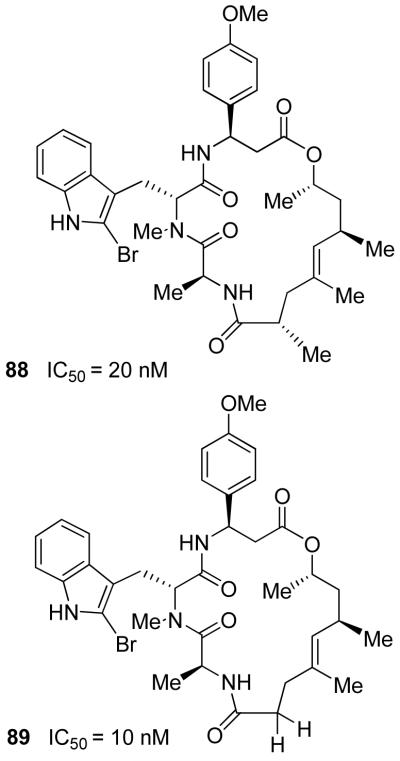

Jasplakinolide (21) has shown good potency against numerous human solid tumor types in cell culture assays. As mentioned, its mode of action involves stabilization of actin filaments by binding to F-actin similar to phalloidin.60 The clinical potential of jasplakinolide was further investigated by the National Cancer Institute. However, studies were terminated because of toxicity issues.61 Chemical and biological investigations of jasplakinolide, and its analogs, remain an extremely active area of research. We have devised a practical synthesis of jasplakinolide that has enabled us to prepare a number of structural variants.28 As shown in Figure 15, the polyketide segment of 21 was first constructed by a diastereoselective aldol reaction that provided 83, followed by an ortho-ester-promoted Claisen rearrangement to form the γ,δ-unsaturated ester 85 in a 7:1 mixture of diastereomers. It was then converted to alcohol 86. The β-amino acid segment 87 was synthesized using an asymmetric enolate addition to a chiral sulfinimine derivative developed by David and co-workers.62 Strategic assembly of the various segments led to the synthesis of jasplakinolide (21).28 This synthesis enabled us to probe the importance of various substituents, improve potency, and reduce complexity. As shown in Figure 16, two less complex jasplakinolide analogs have shown comparable potency (IC50) to jasplakinolide, when assayed against CA46 Burkitt lymphoma human cell lines.63 Analog 88 (IC50 = 20 nM) allowed us to replace the metabolically susceptible phenolic OH with OMe. In analog 89, we have eliminated the C2-methyl chiral center and the resulting analog maintained potency (IC50 = 10 nM).

Figure 15.

Synthesis of Jasplakinolide (21).

Figure 16.

Potent analogs of Jasplakinolide.

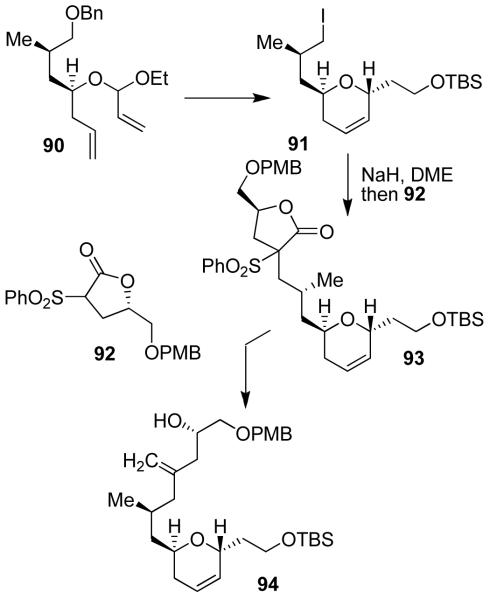

Our interest in the synthesis of laulimalide began in 1997, because of its intriguing structural features as well as its impressive cytotoxicity against KB cells (IC50 = 15 ng/mL) and many other NCI cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 10 to 50 ng/mL.64 The biological mechanism of action of laulimalide was not known until 1999, when Susan Mooberry and co-workers first reported that like taxol, laulimalide stabilizes microtubule assembly.65 Laulimalide’s natural abundance is limited, it is unstable and readily converts to significantly less potent isolaulimalide. Laulimalide contains nine chiral centers and appears to have similarities to the epothilones. Therefore, it was expected that, like epothilone, laulimalide may bind to a similar site as taxol on β-tubulin. The report of Mooberry and co-workers,65 motivated our work on this molecule and within a year we were able to complete the first total synthesis of laulimalide.19 Most importantly, our synthesis enabled us to carry out a number of important biological studies with synthetic laulimalide.

Our convergent synthesis utilized Grubb’s olefin metathesis to construct both dihydropyran rings of laulimalide. As shown in Figure 17, ring-closing olefin metathesis of 90 followed by a highly diastereoselective anomeric alkylation and further standard synthetic transformations provided iodide 91. The C13-methylene unit and C15-alcohol were introduced by a novel protocol developed by us.19 As shown, alkylation of 92 with iodide 91 provided sulfone 93. It was converted to 94 in a three-step sequence involving (1) reduction by Red-Al, (2) formation of the corresponding dibenzoate, and (3) Na-Hg reduction to provide 94 in 72% yield.

Figure 17.

Synthesis of C3-C16 segment of laulimalide.

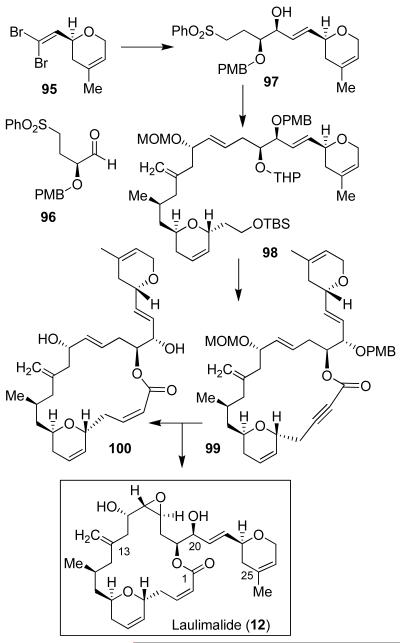

The C17-C28 fragment synthesis was accomplished by the reaction of 95-derived anion and aldehyde 96 to provide the corresponding alkyne derivative (Figure 18). The resulting product was converted to sulfone 97 (Figure 18). Julia olefination of 94-derived aldehyde and sulfone 97 furnished trans-olefin 98 as a major product (3.4:1 trans/cis mixture). It was initially converted to laulimalide (12) by a Horner-Emmons-mediated macrolactonization as the key step.19 An alternative synthesis of laulimalide was carried out in which the C2-C3 cis-olefin was installed selectively. As shown, alcohol 98 was converted to lactone 99, which upon hydrogenation over Lindlar’s catalyst, provided the corresponding cis-macrolactone as a single isomer. The cis-lactone was converted to laulimalide (12).19,66

Figure 18.

Synthesis of laulimalide (12).

Using our synthetic laulimalide, Dr. Hamel at the NCI has shown that laulimalide, while as active as paclitaxel in promoting the assembly of cold-stable microtubules, was unable to inhibit the binding of radiolabeled paclitaxel or a fluorescent paclitaxel derivative to tubulin. Laulimalide has shown potent activity against cell lines resistant to paclitaxel and epothilones A and B on the basis of mutations on M40 human-tubulin gene.67 Furthermore, laulimalide was able to enhance tubulin assembly synergistically with taxol.68 Taken together, laulimalide appeared to be the first example of a ligand for an unknown drug-binding site on tubulin. Our biological evaluation of synthetic intermediates and limited structural variants identified desoxylaulimalide (100, IC50 = 25 ± 5 μM; laulimalide (12), IC50 = 17 ± 3 μM) to be nearly as potent as laulimalide.67 Since our discovery that laulimalide stabilizes microtubules by binding to tubulin at a different site from taxol, further exploration of its chemistry and biology intensified.69 Unlike taxol, laulimalide is not a substrate for P-glycoprotein and also has shown potent activity against taxol resistant cell lines.67 Our synthesis and subsequent biological studies demonstrated the clinical potential of laulimalide. Since laulimalide’s natural abundance is extremely limited, the design of more potent and less complex laulimalide-based synthetic derivatives is warranted.

Interestingly, at about the same time, when we were concluding our synthesis of laulimalide, Northcote and co-workers reported the isolation and structure elucidation of peloruside A, a novel 16-membered macrolide isolated from a New Zealand marine sponge.70 It displayed potent cytotoxicity against P388 murine leukemia cells with an IC50 value of 10 ng/mL. Since its isolation, Miller and co-workers then reported very intriguing properties of peloruside A. It turned out peloruside A is a microtubule stabilizing agent that arrests cells in the G2-M phase of the cell cycle.71 Furthermore, peloruside A binds to a non-taxoid site on tubulin and has shown a synergistic effect with taxol.72 This became an attractive target for synthesis. Peloruside A too has very low natural abundance and its structural complexity and clinical potential attracted our attention to its synthesis and subsequent biological studies.

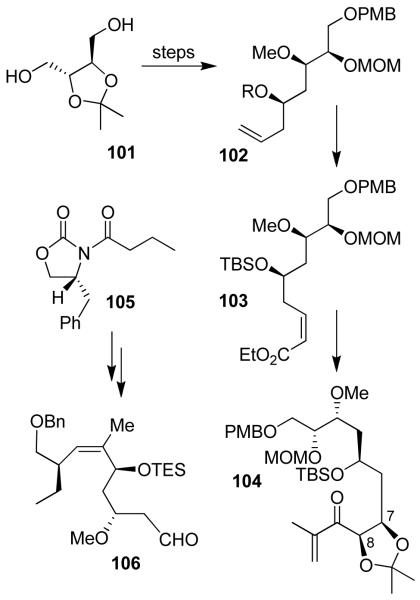

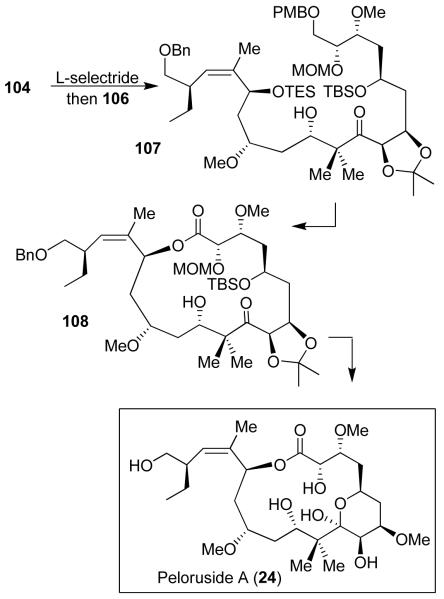

Our synthesis of peloruside A includes the development of a new diastereoselective reductive aldol reaction that assembled the C1-C10 and C11-C24 segments31. As shown in Figure 19, isopropylidene-d-threitol 101 was efficiently converted to homoallylic alcohol 102 using Brown’s asymmetric allylation73 as one of the key steps. Alcohol 102 was converted to α,β-unsaturated ester 103. Sharpless’ asymmetric dihydroxylation74 introduced the C7 and C8-diol stereochemistry. The resulting diol was converted to enone 104. The C11-C20 fragment 106 was synthesized from chiral imide 105. Asymmetric alkylation established C18 stereocenter and successive asymmetric allylboration introduced C13 and C15 stereocenters in 106. A one-pot L-selectride mediated reduction of 104 followed by aldol reaction with aldehyde 106 afforded 107 as a 4:1 mixture of diastereomers in 92% yield (Figure 20). Yamaguchi macrocyclization of the resulting seco acid furnished macrolactone 108, which was ultimately converted to peloruside A.31

Figure 19.

Synthesis of peloruside A subunits 104 and 106.

Figure 20.

Synthesis of peloruside A (24).

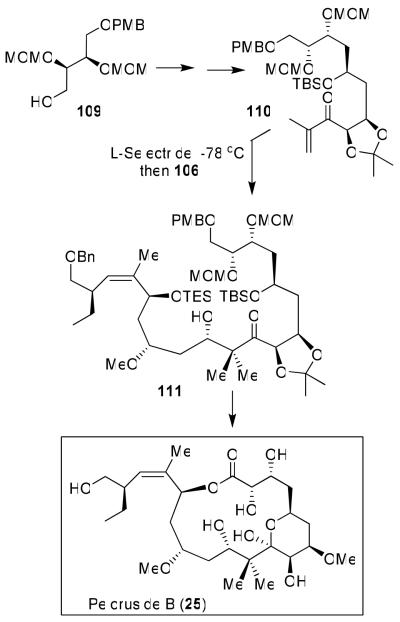

During the course of our synthesis of peloruside A, Northcote and co-workers isolated a compound from M. hentscheli, named peloruside B (25).32 It is the 3-des-O-methyl variant of peloruside A and was isolated in submilligram quantities. Peloruside B’s activity is comparable to that of peloruside A as it arrests cells in the G2/M phase of mitosis. The structure of peloruside B was confirmed with our total synthesis and comparison of its bioactivity in a trans-Pacific collaborative effort.32 Our synthesis of peloruside B followed a similar strategy as peloruside A.31 As shown in Figure 21, the synthesis started with diethyl-d-tartrate-derived bis-MOM derivative 109, which was converted to enone 110. A reductive aldol strategy described previously31 assembled the key fragments, providing 111 as the major diastereomer (6.5:1 mixture) in 66% yield. This was then converted to peloruside B.32 Natural peloruside B was confirmed by comparison of the 1D and 2D NMR data of synthetic and natural peloruside B. Furthermore, on the basis of comparison of the bioactivity of the synthetic and natural peloruside B, we were able to establish the absolute configuration of peloruside B. Following the synthesis of peloruside A and B, we have synthesized a number of structural variants of peloruside A and prepared tritiated peloruside A for mechanistic studies. As mentioned above, like laulimalide, peloruside A and B bind to tubulin at a different site than taxol. Our investigation, in collaboration with Dr. Ernest Hamel, on the drug-binding site of peloruside A will be reported in due course.75

Figure 21.

Synthesis and structural confirmation of Peloruside B (25).

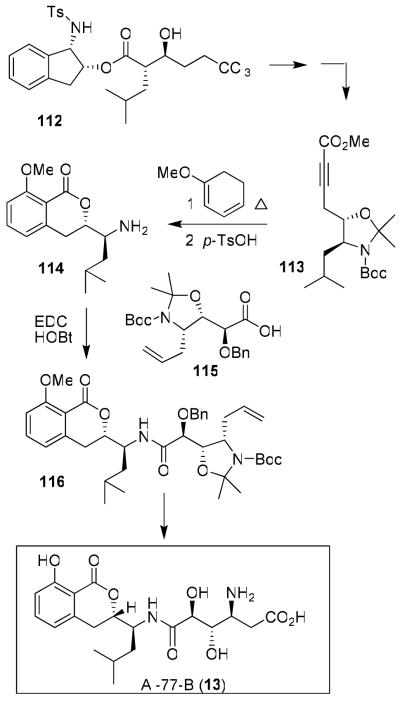

Our synthesis of Al-77-B (12)20 and amphidinolide T1 (15)22 demonstrated the scope and utility of our ester-derived titanium enolate-based asymmetric syn and anti-aldol reactions.76 Al-77-B is a medicinally significant target.77 It has exhibited important gastroprotective properties. Because of its clinical potential, it drew considerable interest in its synthesis and biological studies.78(a,b)

Our synthesis utilized a highly diastereoselective aldol reaction to install four of the five stereocenters of Al-77-B.20 The dihydroisocoumarin skeleton was constructed by a thermal Diels-Alder reaction as shown in Figure 22. Aldolate 112 was obtained in 90% yield as a 19:1 mixture (anti:syn).20 Curtius rearrangement, protection as an isopropylidene derivative followed by treatment with nBuLi/TMEDA and methyl chloroformate, provided 113. Diels-Alder reaction of 113 with methoxy cyclohexadiene proceeded smoothly and the resulting product was cyclized to isochromanone 114 in 74% yield over two steps. The hydroxy amino acid fragment 115 was also assembled by a syn-aldol reaction as the key step. Coupling of 114 and 115 provided amide 116, which was converted to Al-77-B.20

Figure 22.

Synthesis of AI-77-B (13)

Kobayashi and co-workers79 isolated a new class of natural products named the amphidinolides, which have shown significant antitumor properties against a variety of NCI tumor cell lines. Amphidinolides are extremely scarce and subsequent biological studies have been limited. In many cases, structural assignment was hampered due to a lack of natural abundance.79 We carried out the first syntheses of amphidinolide T1, amphidinolide W, and more recently, iriomoteolides 28 and 29 that were isolated from Amphidinium sp.

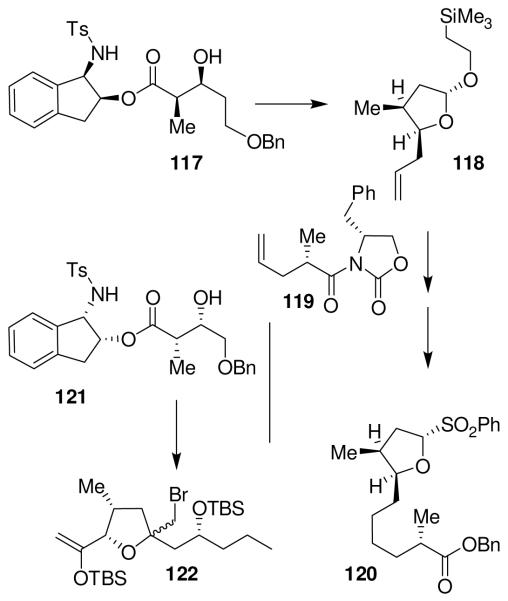

Our synthesis of amphidinolide T1 utilized a highly diastereoselective ester-derived Ti-enolate aldol reaction. As outlined in Figure 23, aldol product 117 was obtained as a single diastereomer in 90% yield. It was converted to tetrahydrofuran derivative 118. Cross-metathesis of 118 with oxazolidinone derivative 119 was carried out using Grubb’s second generation catalyst.80 The resulting product was converted to sulfone 120. Aldolate 121 was also obtained as a single product in 95% yield. It was transformed into bromotetrahydrofuran 122. A highly stereoselective oxocarbenium ion-mediated alkylation of 120 with 122 provided 123 as a single product in 73% yield (Figure 24). It was converted to macrolactone 124. A reductive opening of bromoether 124 with Zn/NH4Cl provided synthetic amphidinolide T1.

Figure 23.

Synthesis of sulfone 120 and bromoether 122

Figure 24.

Synthesis of amphidinolide T1 (14)

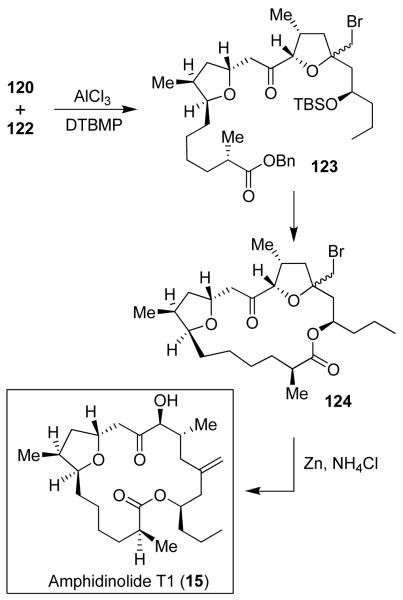

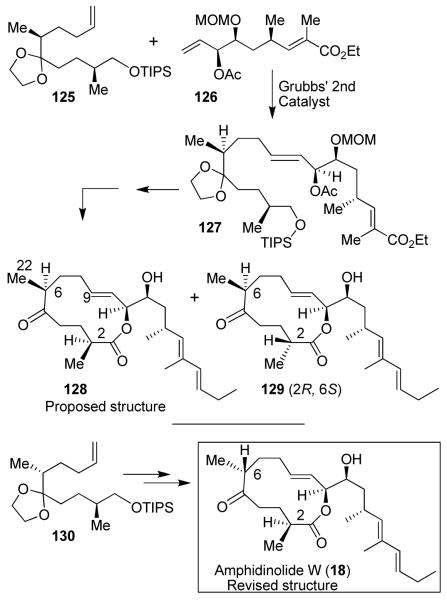

We have also carried out the first synthesis and revision of the structure of amphidinolide W.25 As depicted in Figure 25, the C1-C9 segment 125 was synthesized by asymmetric alkylation and Horner-Emmons reaction as the key steps. The C10-C20 segment 126 was prepared by asymmetric dihydroxylation as the key step. Cross-metathesis80 of 125 with 126 provided 127. Macrolactonization of the 127-derived seco acid provided a 3:1 mixture of macrolactones. These were converted to the proposed structure of amphidinolide 128 and its epimer 129. However, neither structure matched with the reported spectral data of the natural product. Our comparison of NMRs of the synthetic and natural amphidinolide W revealed discrepancies of chemical shifts at the C6 stereocenter. On the basis of this observation, we carried out synthesis of the C6 epimeric seco acid starting from the C1-C9, segment 130 which upon macrocyclization afforded the corresponding macrolactone as a 1:1 mixture. The removal of protecting groups from the C-6 epimer provided amphidinolide W (18), which was in complete agreement with the reported spectral data and optical rotation of natural amphidinolide W.25

Figure 25.

Synthesis and structural revision of amphidinolide W (18)

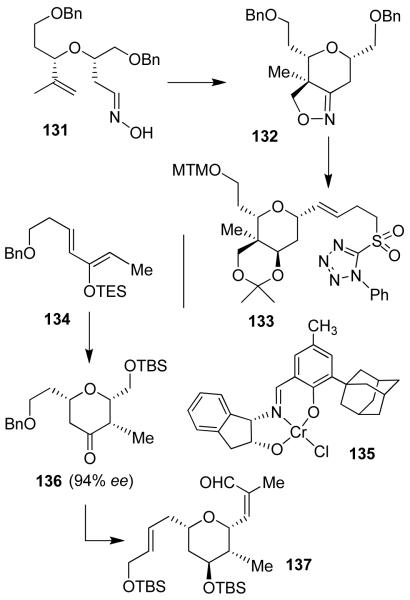

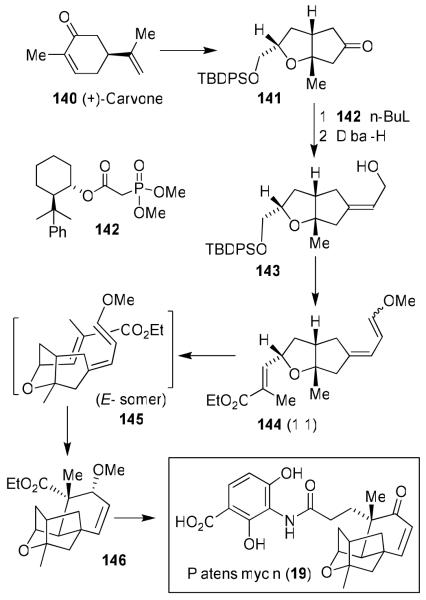

We embarked on the synthesis of (−)-lasonolide A due to its potent antitumor properties and a lack of knowledge of its biological mechanism of action. Lasonolide A’s natural abundance is low and no structure-activity studies have been reported. Lasonolides are a group of natural products isolated from a Caribbean marine sponge. Among this family, lasonolide A has shown the most potent cytotoxicity with IC50 values of 8.6 nM and 89 nM against A-549 human lung carcinoma, and panc-1 human pancreatic carcinoma, respectively. Lasonolide A contains nine chiral centers with two highly functionalized tetrahydropyran rings. As shown in Figure 26, both tetrahydropyran rings have been constructed stereoselectively. Intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of 131 provided bicyclic isooxazoline 132, which allowed for the construction of the pyran ring as well as the quaternary stereocenter in 22. It was converted to isopropylidene derivative 133.

Figure 26.

Synthesis of tetrahydropyran derivatives

An asymmetric hetero-Diels Alder reaction of diene 134 and silyoxyacetaldehyde using Jacobsen’s catalyst 135 afforded 136 with three chiral centers, in high optical purity (94% ee). This was converted to aldehyde 137. Julia olefination of 137 with sulfone 133 afforded E-olefin 138 (Figure 27). Macrolactone 139 was prepared by intramolecular Horner-Emmons reaction. This was converted to lasonolide A (22).29 Using synthetic lasonolide A, we have investigated the biological mechanism of action in collaboration with Dr. Yves Pommier of the National Cancer Institute. Our studies revealed that lasonolide A unusually induces premature chromosome condensation.81 This finding may lead to treatment of many disorders.81

Figure 27.

Synthesis of (−)-lasonolide A (22).

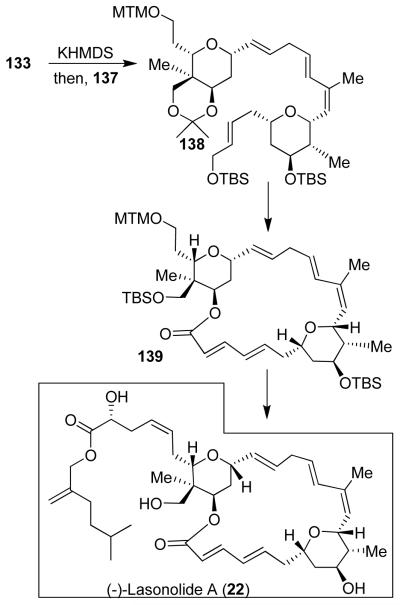

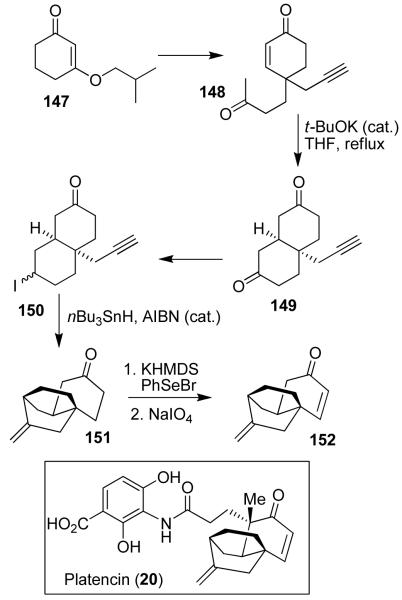

The discovery of platensimycin and platencin as inhibitors of bacterial β-ketoacyl synthase (FabF), by Merck researchers, grasped the attention of chemists and biologists around the world.82 Since the discovery of penicillins in the 1940’s, isolation and characterization of novel antibiotic natural products have been limited. Both platensimycin and platencin exhibited a broad range of activity against Gram-positive organisms, good in vivo efficacy, and no observed toxicity in mice.82 However, both these natural products showed very poor pharmacokinetic properties and could not be used as drugs.83 Therefore, structural changes are necessary for these natural product leads, which have become a subject of great synthetic interests.84

Our synthesis of the platensimycin core is unique in the sense that we planned to construct it using an intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction.26 As shown in Figure 28, (+)-carvone 140 was converted to bicyclic ketone 141. Horner-Emmons olefination of 141 with chiral phosphonoacetate 142 was utilized to obtain E-olefin 143 selectively (E/Z ratio 4.5:1). Triethyl phosphonoacetate in comparison provided 143 as a 1.5:1 E/Z olefin mixture. Olefin 143 was converted to triene 144, the Diels-Alder precursor. Thermal Diels-Alder reaction in a sealed tube in chlorobenzene in the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (BHT) as a radical inhibitor provided 146. Only the E-isomer 145 underwent cyclization and the Z-isomer was recovered and recycled after isomerization. Diels-Alder product 146 was obtained in 44% overall yield from 144. This was converted to platensimycin (19).26

Figure 28.

Synthesis of platensimycin (19)

We have carried out a concise formal synthesis of platencin using a symmetry-based approach.27 As shown in Figure 29, synthesis of enone 148 was achieved from commercial cyclohexenone 147. Michael reaction of 148 with catalytic t-BuOK in THF at reflux afforded symmetric diketone 149. Selective monoreduction of diketone by LiAl(Ot-Bu)3H provided the corresponding alcohol (7:1 mixture, 83% yield). This was converted to iodide 150. Radical cyclization of 150 with nBu3SnH in the presence of AlBN resulted in platencin core 151, which was converted to enone 152. This was previously converted to platencin.85 Our synthesis provided a quick and efficient access to the platencin core structure.27

Figure 29.

Formal synthesis of Platencin (20).

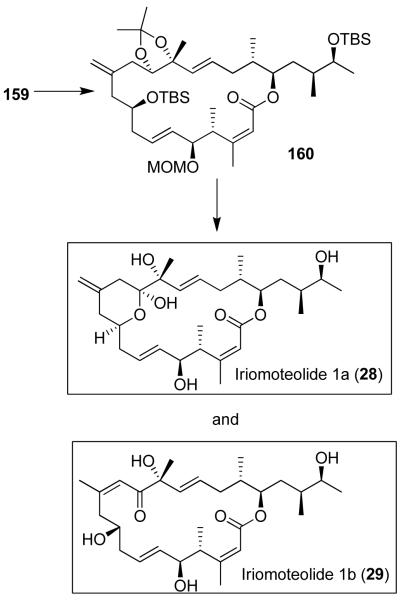

Iriomoteolide 1a (28) attracted our attention because of its structural resemblance to laulimalide (12) and peloruside A (24). Iriomoteolide 1a (28) has shown exceedingly potent cytotoxicity against human B lymphocyte DG-75 cells with IC50 values of 2 ng/mL.86 The biological mechanism of action of iriomoteolide 1a is presently unknown. Iriomoteolide 1a has been isolated in minute quantities and the structures of iriomoteolide 1a and 1b were elucidated by spectroscopic studies. Our preliminary work leading to the synthesis of the proposed structures of both iriomoteolide 1a (28) and iriomoteolide 1b (29) suggested that both structures were assigned incorrectly.35

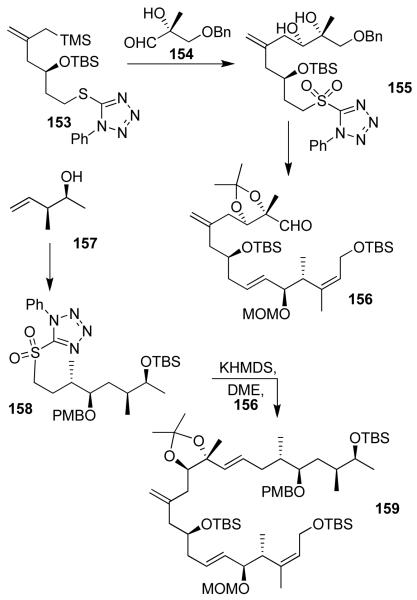

Our convergent synthesis of proposed structures of iriomoteolides is shown in Figure 30 and 31. A Sakurai reaction of allyl silane 153 with aldehyde 154 provided 155 after oxidation of the sulfide to sulfone. This was converted to aldehyde 156 utilizing a Julia-Kocienski olefination as the key step. Optically active alcohol 157 was prepared using Brown’s asymmetric crotylboration.87 This was converted to sulfone 158. The key Julia olefination of 156 with 158 provided 159 in 70% yield. Yamaguchi macrolactonization of 159-derived seco acid furnished macrolactone 160. It was further transformed into the proposed structures of iriomoteolide 1a (28) and iriomoteolide 1b (29).35 Our detailed spectroscopic studies of the structures of 28 and 29 provided a number of discrepancies at some specific carbon centers of the reported NMR spectra. This information is currently used for the structural assignment of these natural products. Our current investigation is focused on both structural and biological studies of iriomoteolides.

Figure 30.

Synthesis of 159 by double Julia olefinations.

Development of Asymmetric Methodologies

In the context of our synthesis of natural and unnatural bioactive molecules, we have developed a variety of asymmetric methodologies. These include asymmetric anti- and syn-aldol reactions, asymmetric multicomponent reactions, and asymmetric reductive aldol reactions. Asymmetric aldol reactions have been a significant development in organic synthesis.88 A number of practical and reliable technologies have evolved over the years, particularly for the asymmetric generation of syn-aldol products. These asymmetric processes have been extensively used in the synthesis of complex bioactive molecules with multiple stereocenters. This subject has been an active area of investigation for nearly three decades.88 While asymmetric syn-aldols, most notably Evans’ chiral oxazolidinone-based aldol additions,38 are widely used, the corresponding anti-aldol reactions are used less frequently due to a lack of practical asymmetric anti-aldol reactions.88

Development of an asymmetric anti-aldol reactions

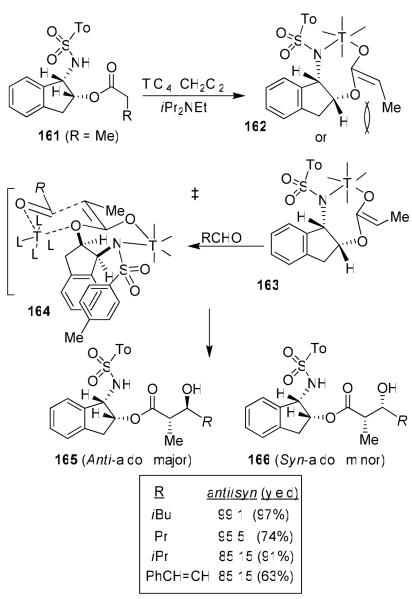

We have developed highly diastereoselective ester-derived titanium enolate-based anti-aldol reactions using conformationally constrained cyclic amino alcohol-derived chiral sulfonamide 161.89 Optically active (1S, 2R) and (1R, 2S)-1-amino-2-indanols are readily available commercially as well as through practical synthesis, enabling the synthesis of both enantiomer of the anti-aldol product. The propionate derivative 161 was readily prepared by tosylation of 1-amino-2-indanol followed by O-acylation with propionyl chloride (Figure 32). The titanium enolate of 161 was readily formed by treatment with TiCl4 and diisopropylethylamine at 0 °C in CH2Cl2 for 1 h.89 The alkyl ester alone can not be enolized effectively with TiCl4 and a base.91 However, smooth enolization of 161 was possible presumably due to internal chelation with the sulfonamide group as shown in 163. This type of enolate formation was first shown by Xiang et al.92

Figure 32.

Ti-enolate-based asymmetric anti-aldol reaction

The 1H NMR-analysis revealed the presence of a single enolate. The Z-enolate 163 is preferred over 162 due to minimization of the 1,3-allylic strain between the methyl group and the indanol auxiliary. Also, 1H NMR spectra showed the disappearance of the sulfonamide hydrogen which supported the formation of the cyclic enolate shown. Treatment of the resulting enolate directly with isovaleraldehyde provided no aldol addition product. However, reaction of the enolate with isovaleraldehyde precomplexed with TiCl4, provided the anti-aldol product 165 (R = iBu) as a single isomer (by HPLC and NMR analysis). Reactions with a variety of monodentate aldehydes also provided the anti-aldols with excellent diastereoselectivity and isolated yields. It should be noted that among four possible diastereomers, only one anti-aldol (165) and one syn-aldol (166) product were observed in this reaction.89

The stereochemical outcome of the anti-addition could be rationalized by using the Zimmerman-Traxler type transition state model 164.93 The model is based upon the assumptions that the titanium enolate geometry is Z, the titanium enolate is a seven-membered metallocycle with a pseudo chair-like conformation and a second Ti is chelated to the indanyloxy group as well as to the aldehyde carbonyl in a six-membered chair-like transition state. The model explains our observed diastereoselectivity.89 Our subsequent structure-selectivity studies revealed that ring, substitution, and stereochemistry all are critical to the observed high anti-aldol diastereoselectivity.88 The reaction of the corresponding N-mesylamine indanol with isovaleraldehyde provided a 70:30 mixture of anti/syn diastereomers. This result suggested that a possible π-stacking interaction between the two aromatic rings may have provided the stabilization of the enolate conformation shown in 164.

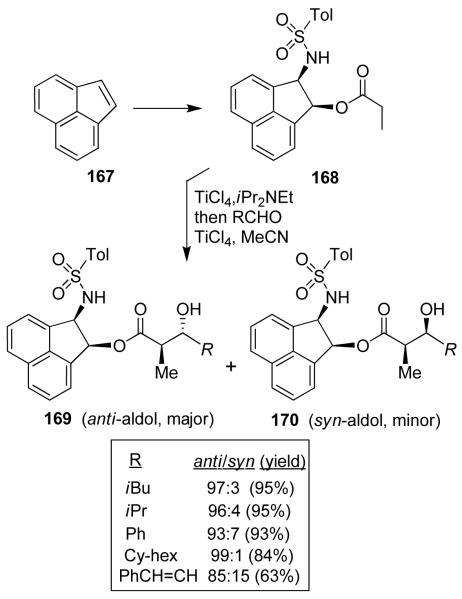

Based upon the results, we then speculated that the planarity of the acenaphthene ring may further enhance secondary-orbital interactions with the arylsulfonamide functionality. We have developed an effective syntheses of both enantiomers of cis-2-amino-1-acenaphthenol in high enantiomeric excess (>98% ee) employing lipase-catalyzed enzymatic resolution as a key step.94 The aldol reaction of propionate ester 168 (Figure 33) with isovaleraldehyde however, provided a significant reduction in anti-diastereoselectivity. The use of various chelating additives led to an improvement in diastereoselectivity for 169. It turned out 2.2 equivalents of acetonitrile provided a significant improvement of anti-diastereoselectivity as well as yield with a variety monodentate aldehydes.94

Figure 33.

Cis-2-amino-1-acenaphthenol-based anti-aldol reactions

We investigated the effects of a variety of other additives. Both acetonitrile and N-methylpyrrolidinone (NMP) showed the best results with respect to anti-diastereoselectivity and isolated yields. These conditions were employed in the asymmetric aldol reaction of chloroacetate with a range of monodentate aldehydes. Both NMP and acetonitrile as additives provided the best results, providing consistently excellent anti-diastereoselectivity and yields. The chloroacetate aldol reaction provided access to acetate aldol products in high ee.95

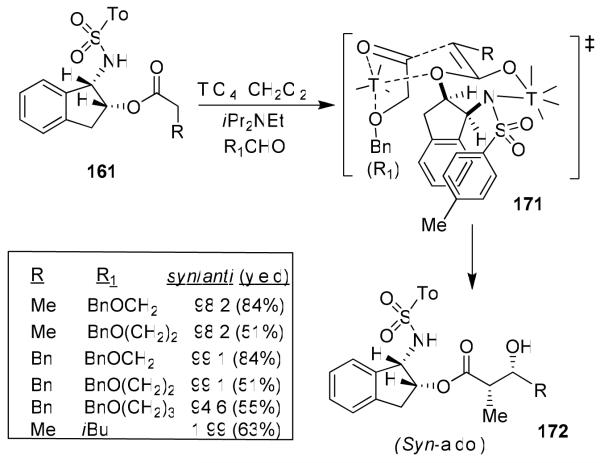

Development of asymmetric syn-aldol reactions

Based upon the proposed transition-state assembly for the anti-aldol reaction,89 we postulated that a bidentate alkoxyaldehyde would adopt a transition state like 171 (Figure 34) so that the ether oxygen could effectively donate its lone pair to the vacant d-orbital of titanium and the alkoxy aldehyde side chain will be oriented pseudo-axially, giving rise to syn-aldol product 172 selectively.96 Indeed, reaction of benzyloxyacetaldehyde and benzyloxypropionaldehyde proceeded with excellent diastereoselectivity. The aldol reaction with benzyloxybutyraldehyde provided slightly reduced syn-diastereoselectivity (dr 94:6). Aldol reactions of chloroacetate with the bidentate aldehydes provided aldol products with high syn-diastereoselectivity and yields.95

Figure 34.

Development of the asymmetric syn-aldol reaction

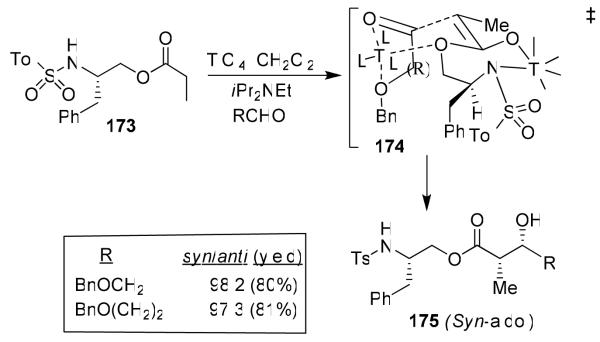

Based upon our proposed highly chelated transition state, we further speculated that a α-chiral center on the indane ring may not be required for syn-diastereoselectivity with bidentate aldehydes. We therefore investigated amino acid-derived chiral sulfonamides. As shown in Figure 35, phenylalaninol-derived auxiliary 173 provided aldol product 175 with excellent syn-diastereoselectivity (dr 98:2) with alkoxyaldehyde. We have also investigated double diastereodifferentiation using chiral bidentate aldehydes. In a matched case, (R)-2-benzyloxypropionaldehyde furnished the syn-diastereomer. However, the (S)-aldehyde provided an anti-aldol diastereomer.97 The (S)-benzyloxypropionaldehyde was recovered in 40% yield with 94% ee.97

Figure 35.

Phenylalaninol-based highly diastereoselective syn-aldol reactions.

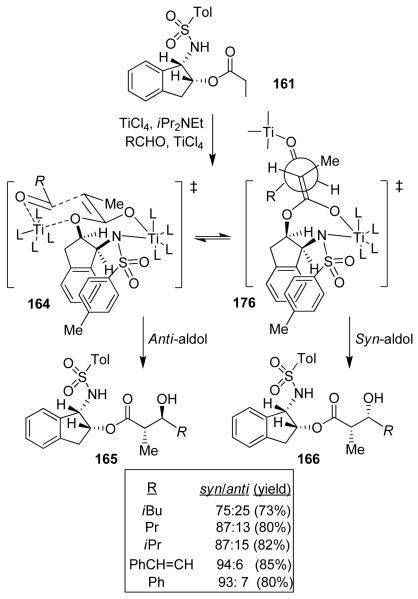

As mentioned earlier, activation of monodentate aldehydes with TiCl4 and other Lewis acids were necessary to observe anti-diastereoselectivity.89 We have subsequently investigated the effect of increasing quantities of TiCl4 on the syn:anti product ratio and reaction yields.22b,97 Interestingly, when cinnamaldehyde was complexed with 3 equiv of TiCl4, there was a dramatic reversal of diastereoselectivity. Reaction of 161 with 2 equiv of cinnamaldehyde, precomplexed with 5 equiv of TiCl4, provided excellent yield (95%) and excellent syn-diastereoselectivity (dr: 95:5). As shown in Figure 36, the generality of this reaction was examined with a variety of aldehydes. We rationalized the stereochemical outcome by using an open-chain transition state model 176, which is favored with excess equivalents of TiCl4 and provides syn-aldol product diastereoselectivity.

Figure 36.

Development syn-aldol with monodentate aldehydes

These mechanism-based ester-derived Ti-enolate aldol additions, developed in our laboratory, were extensively utilized in the synthesis of numerous bioactive natural products as well as in the synthesis of the bis-THF ligand for darunavir®,98 and peptidomimetic derivatives99 for medicinal chemistry. One of the interesting features of the current asymmetric aldol reaction is that either syn or anti-aldol product can be generated from the same chiral auxiliary with the appropriate choice of aldehyde and the stoichiometry of TiCl4 used. Furthermore, the ready availability of both enantiomers of the cis-aminoindanol90 provides an access to all possible syn and anti-aldols in optically active form.

Asymmetric Diels-Alder and hetero Diels-Alder reactions

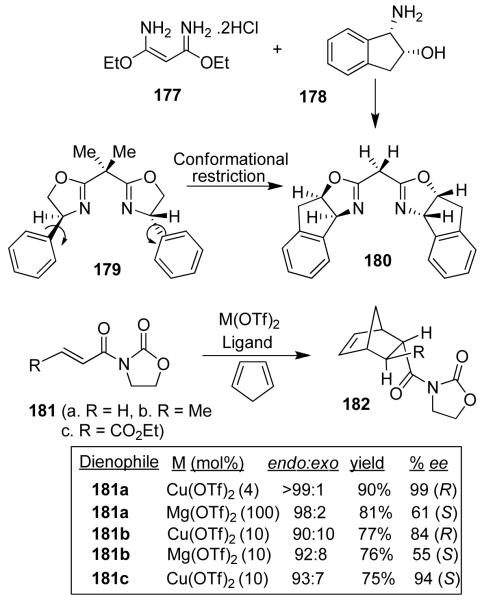

We have demonstrated the usefulness of the cis-aminoindanol as a chiral auxiliary in a variety of transformations including Diels-Alder reactions, aldol reactions, and asymmetric reductions.90 Subsequently, we have investigated cis-aminoindanol-derived bis(oxazoline)-metal-catalyzed asymmetric reactions.100 The C2-symmetric chiral bis(oxazoline) ligands have now been developed as privileged ligands for a variety of asymmetric transformations.101 Early investigation in this area involved bis(oxazoline)-Cu(II)-catalyzed asymmetric cyclopropanation by Masamune et al.,102 asymmetric Diels-Alder reactions with Phe-Box-Fe(III) and Phe-Box-Mg(II) by Corey103 and tert-Box-Cu(II)-catalyzed reactions by Evans.104 In an effort to improve Phe-Box-Cu(II)-catalyzed Diels-Alder reactions, we speculated that the cis-aminoindanol-derived bis(oxazoline) may well serve as a conformationally constrained alternative to the Phe-Box ligand. In this context, we first prepared aminoindanol-derived bis(oxazoline) ligands 180 and ent-180 by condensation of the imidate salt 177 with optically active aminoindanol 178 as shown in Figure 37.105 We have prepared a variety of metal-bis(oxazoline) complexes as catalysts for asymmetric Diels-Alder and hetero Diels-Alder reactions. As shown, Cu(II)-catalyzed reactions with acryloyl-N-oxazolidinone proceeded with excellent endo/exo selectivity as well as endo-enantioselectivity (up to 99% ee), in contrast to Phe-Box-Cu(II)-catalyzed reactions (30% ee).105 Based upon this result, a variety of N-acyl oxazolidinones were surveyed and INDA-Box-Cu(II) has shown consistently good to excellent enantioselectivity with 10 mol % ligand-metal complexes.105

Figure 37.

Chiral bis-oxazoline-metal-catalyzed Diels-Alder reactions

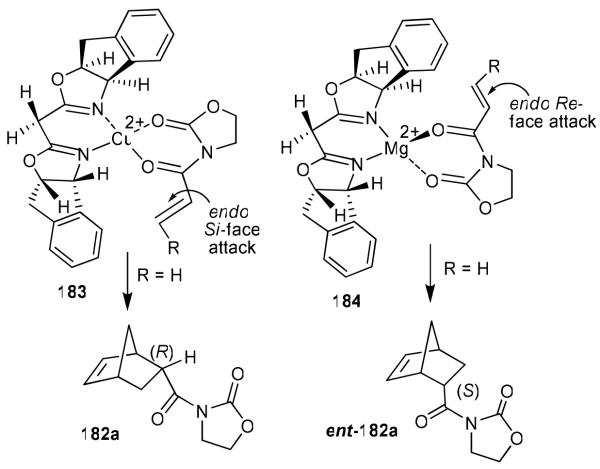

Furthermore, we have investigated cationic aqua complexes derived from INDA-Box and Cu(ClO4)2·6H2O and Ni(ClO4)2·6H2O, which provided excellent yield and enantioselectivity (up to 98% ee).106 Interestingly, we have observed a reversal of enantioselectivity with Mg(II)-catalyzed reactions (55-65% ee).105,106 These results were rationalized using a square planar model of the Cu(II)-ligand complex 183 and a S-cis conformation of the dienophile as shown in Figure 38. As can be seen, an endo-Si-face attack is favored. For the Mg(II)-catalyzed reaction, we assumed a tetrahedral Mg(II) geometry (184) as proposed by Corey and Ishihara.103 An endo-Re-face attack of cyclopentadiene explains the reversal of selectivity caused by Mg(II)-catalyzed reactions. Since 1996, bis(oxazoline) ligand 180 and its derivatives have been extensively used for a variety of other catalytic asymmetric syntheses.101

Figure 38.

Stereochemical models for Cu(II) and Mg (II)-bis-oxazoline catalyzed Diels-Alder

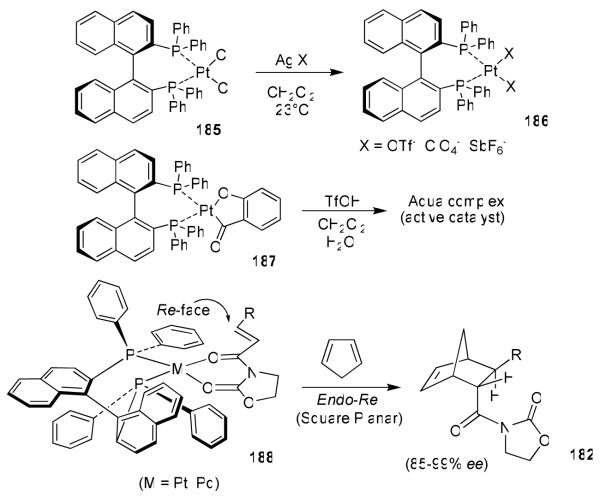

We have also developed cationic Pt(II- and Pd(II)-BINAP complexes (186) for asymmetric Diels-Alder reactions with bidentate acyloxazolidinones and cyclopentadiene.107 As shown in Figure 39, cationic complexes prepared by treatment of 187 with triflic acid and water provided a dramatic rate acceleration, and resulted in cycloadduct 182 (R = H) in 98% ee and 80% yield within 1 h. Pd(II)- and Pt(II)-BINAP-catalyzed reactions were rationalized by a postulated transition-state assembly as shown in 188. The endo-Re-face attack is favored over the Si-face attack because of developing non-bonding interactions in the transition-state.107

Figure 39.

Pt(II) and Pd(II)-BINAP complexes in Asymmetric Diels-Alder reactions

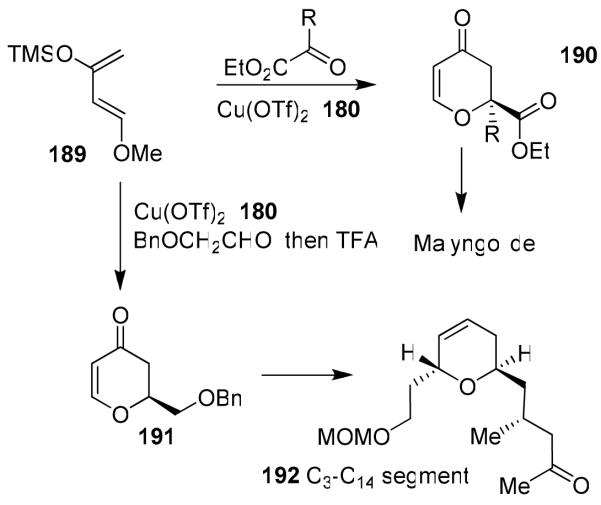

Development of asymmetric catalytic hetero-Diels-Alder reactions

We have investigated asymmetric hetero-Diels-Alder reactions using bis(oxazoline)-metal complexes with Danishefsky’s diene and bidentate aldehydes such as glyoxylate ester, 1,3-dithiane-2-carboxaldehyde and benzyloxyacetaldehyde. The reaction proceeded in a stepwise manner via a Mukaiyama aldol reaction followed by ring closing with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to provide dihydropyranone 190. We have isolated and characterized both the Mukaiyama aldol product and dihydropyranone 190 prior to complete cyclization to 190 with TFA. Reactions of benzyloxyacetaldehyde provided dihydropyranone 191 in 76% yield and 85% ee. This was converted to the C3-C14 segment 192 of laulimalide.108

Our investigation on α-keto esters with Danishefsky’s diene provided dihydropyranone derivatives 190 in good to excellent yield and high enantioselectivity (up to 99% ee).17 This methodology constructed a quaternary carbon center in the synthesis of marine natural product (−)-malyngolide.17

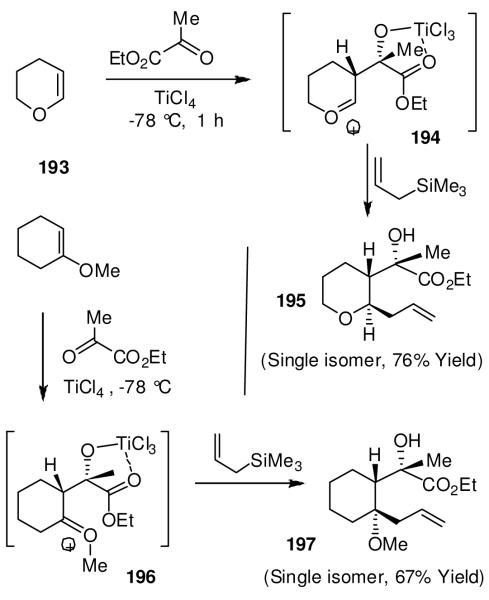

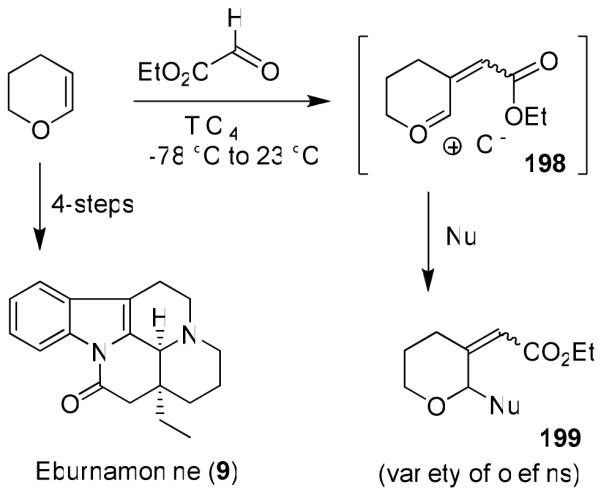

Asymmetric multicomponent reaction

We developed very efficient multicomponent reactions that provided multiple carbon-carbon bond formation leading to highly functionalized heterocycles in a one-pot operation.109 As shown in Figure 41, reactions of enol ethers 193 with bidentate aldehydes and ketones such as alkyl glyoxylate or pyruvates in the presence of TiCl4 presumably provided oxocarbenium ion intermediate 194. This was trapped with a variety of nucleophiles to provide functionalized tetrahydrofuran and tetrahydropyran derivatives, like 195, in good-to-excellent yields.109 The overall process results in two carbon-carbon bonds formation and generates three chiral centers as shown in 195. Interestingly, the reactions with pyruvates proceeded with excellent diastereoselectivity.110 Reaction with methoxycyclohexene presumably proceeded through an oxocarbenium ion 196 and resulted in a single multicomponent product 197 with three new contiguous centers. We further investigated the potential to form carbon-carbon double bonds via the formation of an alternative oxocarbenium ion 198 upon warming the reaction to room temperature. Indeed, the reaction provided an access to a variety of α,β-unsaturated esters 199 in a single operation.111 This reaction was utilized in a four step synthesis of (+)-eburnamonine (9)16 as shown in Figure 42.

Figure 41.

Development of new multicomponent reactions.

Figure 42.

Synthesis of eburnamonine (9) using multicomponent reaction.

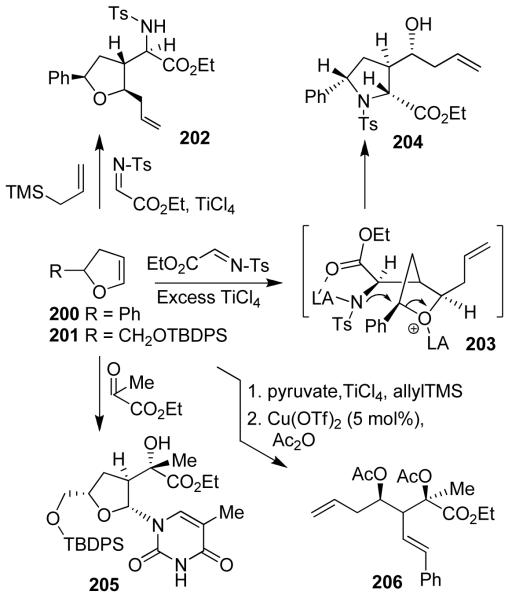

Asymmetric multicomponent reactions with optically active substituted dihydrofurans (200, 201) and N-tosyl imino ester or pyruvates also proceeded with good to excellent yields and excellent diastereoselectivity. Compound 202 was obtained as a single isomer (Figure 43).112 Removal of the N-tosyl group and ester hydrolysis provided access to a variety of cyclic unnatural amino acids with multiple stereocenters.112 We then investigated the possibility of an asymmetric multicomponent route to synthesize pyrrolidines and prolines. Multicomponent reactions with an imino ester in the presence excess Lewis acid provided highly functionalized pyrrolidine derivative 204 in high diastereoselectivity (dr 99:1).113 The pyrrolidine product presumably formed through the oxonium ion 203 due to the presence of excess Lewis acid. The SN2 nucleophilic attack of the sulfonamide nucleophile (NTs−) to the carbon center of a Lewis acid-activated oxonium ion leads to pyrrolidine 204. A variety of substituted pyrrolidines have been prepared in a one-pot operation.113 An asymmetric multicomponent reaction of optically active dihydrofuran 201 with ethyl pyruvate provided our presumed oxocarbenium ion which was reacted with purine and pyrimidine bases to provide modified nucleosides in high diastereoselectivity and good yields.114 Reaction with glyoxylate afforded a 1:1 mixture. The corresponding reaction with pyruvate provided 205 with excellent diastereoselectivity (dr: 99:1).114 Various asymmetric multicomponent reactions thus provided functionalized tetrahydrofurans with multiple stereogenic centers in a highly diastereoselective manner. To further broaden the scope and utility of the multicomponent reaction, we have investigated Lewis-acid-catalyzed cleavage of the tetrahydrofuran ring through an acyloxy carbenium ion intermediate to provide acyclic derivatives 206 with three contiguous stereogenic centers. Ring closing olefin metathesis of such an intermediate provided access to cyclopentene derivatives or other designed molecules.115

Figure 43.

Asymmetric multicomponent reactions.

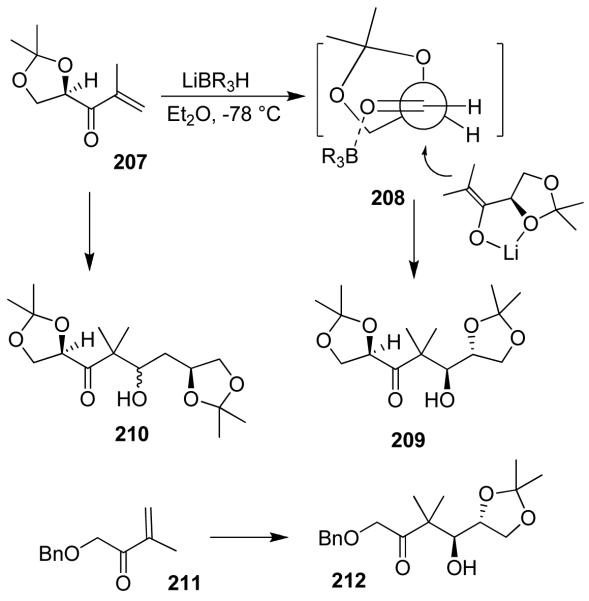

Asymmetric reductive aldol reaction

Recently, we have developed a highly diastereoselective asymmetric reductive aldol reaction.116 As shown in Figure 44, aldol reaction of the enolate generated by addition of l-selectride to enone 207 and isopropylidene-d-glyceraldehyde in ether at −78 °C provided only one single diastereomer 209, in 70% yield. Reaction with chiral isopropylidenebutyraldehyde however, provided a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers. The corresponding reaction with isovaleraldehyde provided a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers 210, suggesting that the α-chirality of the isopropylidene-d-glyceraldehyde is responsible for the diastereoselectivity as proposed in the stereochemical model 208.116 Indeed, reaction with an achiral enone 211 and isopropylidene-d-glyceraldehyde provided single isomer 212. This asymmetric reductive aldol reaction was utilized in the synthesis of peloruside A and B.31,32

Figure 44.

Highly diastereoselective asymmetric reductive aldol reaction

Nature inspired molecular design for today’s medicine

Our natural product syntheses have inspired our development of new synthetic methodologies. Such research endeavors, in general, have undeniably had a profound impact in medicine and society.117 The seemingly endless beauty, structural features, and associated bioactivity of natural products brought a unique perspective to our design and studies of diverse molecular probes relevant to today’s medicine. As I have pointed out earlier, the majority of our synthesized targets in Figures 1 and 2 do not contain any peptide-like features, however these molecules bind to their respective biosynthetic enzymes or target proteins or receptors with high affinity. In essence, they often compete against the natural peptide substrates to exhibit an inhibitory effect. Therefore, certain structural features, scaffolds, and templates must be involved in mimicking peptide bonds and side chain conformations. One of our molecular design objectives is to harness nature’s insight and design novel nonpeptidic molecular probes with natural-product derived templates. A particularly intriguing possibility has been the use of conformationally constrained cyclic ethers or sulfones as surrogates of peptide carbonyl bonds. The premise here is that suitably positioned ether oxygens or sulfone oxygens can form hydrogen bonds in the enzyme’s active site similar to a peptide carbonyl oxygen, while the cyclic structure would fill in the hydrophobic pocket effectively. Such a molecular design strategy may lead to molecules with enhanced pharmacological properties and metabolic stability compared to peptide-like compounds. These structural templates are inherent to numerous bioactive natural products such as monensin A,118 ginkgolides,119 and azadirachtin.120 Needless to mention, nature has been optimizing such templates for millions of years in various biological micro environments. Of course, we are cognizant that such a seemingly academic approach to medicinal chemistry may not be attractive in industry due to complexity of design, low probability of success, and challenges associated with the synthesis of such molecules. However, my students and postdoctoral colleagues are often quite motivated in this line of research dealing with stereochemical complexity, challenges in synthesis, and potential applications in human medicine. Our broad synthetic expertise has effectively served as a good complement to our molecular design capabilities.

Our initial focus has been in the area of structure-based design of aspartyl protease inhibitors against HIV-1 protease for the treatment of HIV-infection/AIDS.121 Our molecular design strategy for HIV protease inhibitors has been based upon X-ray structures of inhibitor-bound HIV-1 protease complexes. Of particular note, our critical analysis of the saquinavir 213-bound protease X-ray structure led us to design a potent cyclic sulfone-derived lead 214 (Figure 45).122,123

Figure 45.

Structure of Saquinavir (213) and cyclic sulfone 214 lead structure.

Subsequently, we designed stereochemically defined spiro ethers and spiro ketal-containing potent inhibitors. As shown in Figure 46, inhibitor 215 incorporated structural features of monensin A (216).3,124

Figure 46.

Structures of spiro ketal-derived inhibitor 215 and monensin A.

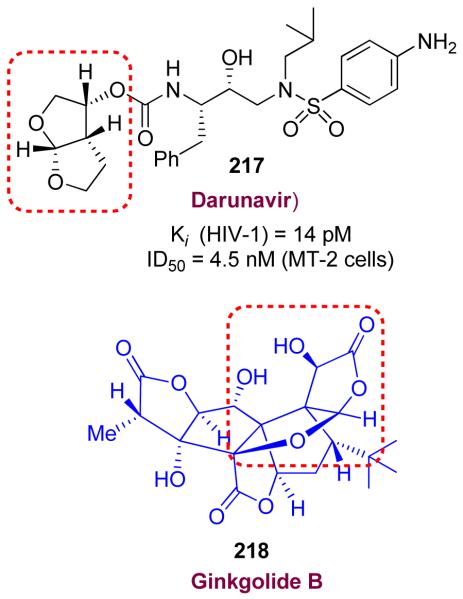

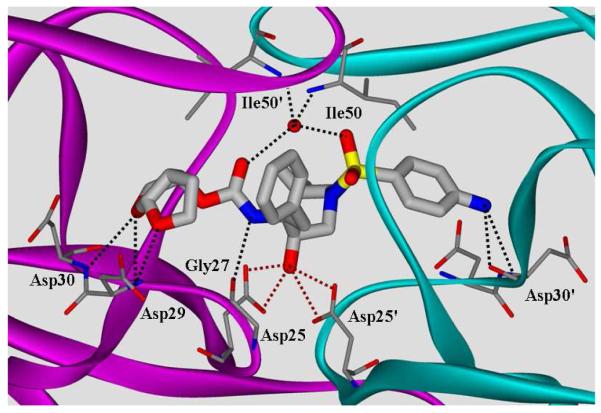

We have also designed a bicyclic fused tetrahydrofuran (bis-THF) as a high affinity ligand for the HIV-1 protease substrate binding site. Inhibitor 217 (UIC-94017 or TMC114) shown in Figure 47, has been exceedingly potent in enzyme inhibitory and antiviral assays.125,126 This class of inhibitors were designed to maximize interactions in the protease active site especially to form a network of hydrogen bonds with the protease backbone from the S2- to S2′-subsites. This basic ‘backbone binding’ design concept127 evolved from our observation of reported X-ray structures that the active site protease backbone conformation is minimally distorted among a wide variety of mutant proteases as compared to that of the wild-type HIV-1 protease. Therefore, we hypothesized that the inhibitors that form many hydrogen bonds with the protein backbone would retain their potency against mutant strains. Indeed, inhibitor 217 exhibited remarkable potency against multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants.128,129 Ultimately, clinical development of 217 culminated in darunavir, which was approved by the FDA in 2006 as the first treatment for patients harboring multidrug-resistant HIV strains.130,131 Since 2008, darunavir has been approved for all patients with HIV-infection and AIDS including pediatric patients.132 The bis-THF ligand design was inspired by the structure and biology of ginkgolide natural products (Figure 47). The X-ray structure of 217-bound HIV-1 protease was determined in collaboration with Dr. Irene Weber at Georgia State University.133 The structure revealed (Figure 48) extensive hydrogen bonding of bis-THF ligand with the backbone atoms of the HIV-1 protease. Also, the inhibitor makes robust interactions throughout the S2-S2′-subsites of the protease. These extensive ‘backbone binding’ interactions may be responsible for darunavir’s potency against multidrug-resistant HIV-variants.129

Figure 47.

Structures of Darunavir and ginkgolide B.

Figure 48.

Darunavir forms an important hydrogen bonding network with protein backbone, shown with black dotted lines

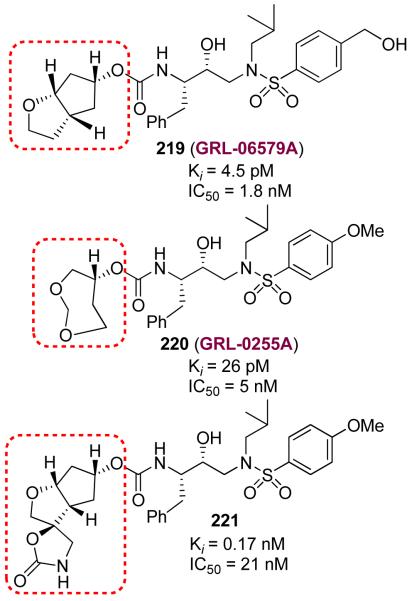

Our structure-based design strategy led to a number of other exceedingly potent inhibitors (219-221)134-136 with diverse stereochemically defined ligands shown in Figure 49. Our work has demonstrated that the design concept targeting the protein backbone may serve as an important guide to combat drug-resistance.

Figure 49.

Structure of inhibitors 219-221.

β-Secretase (memapsin 2) inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease

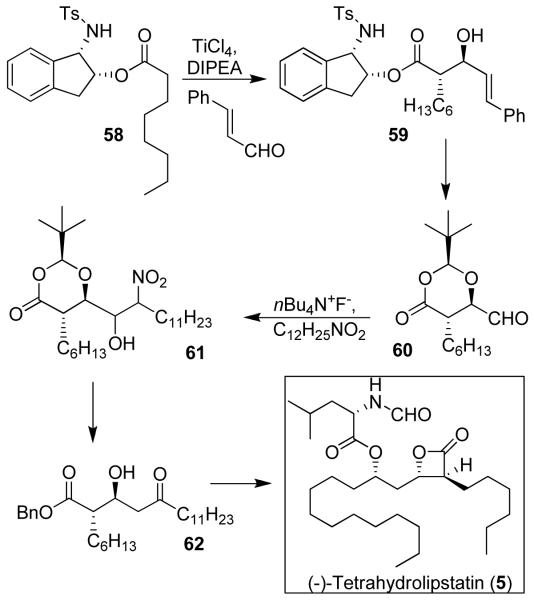

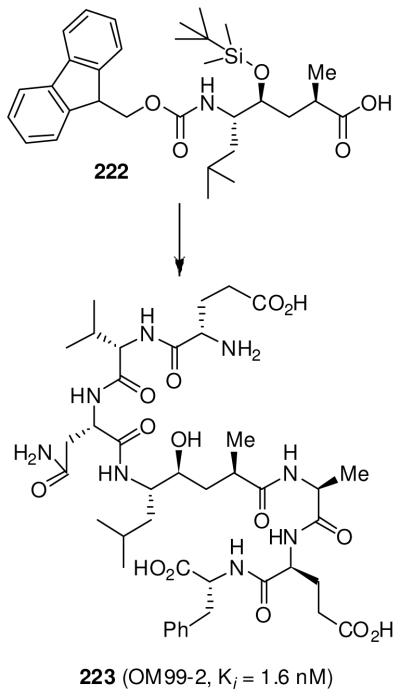

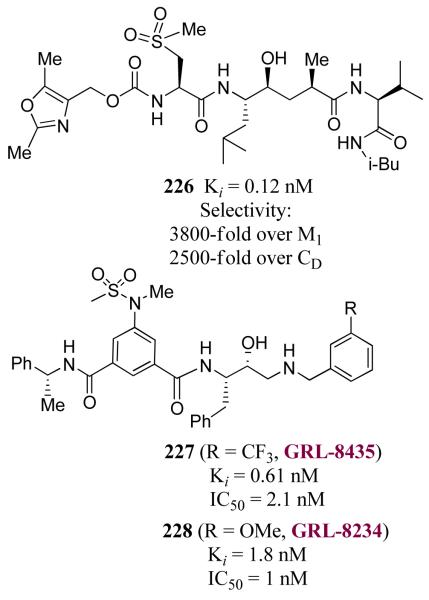

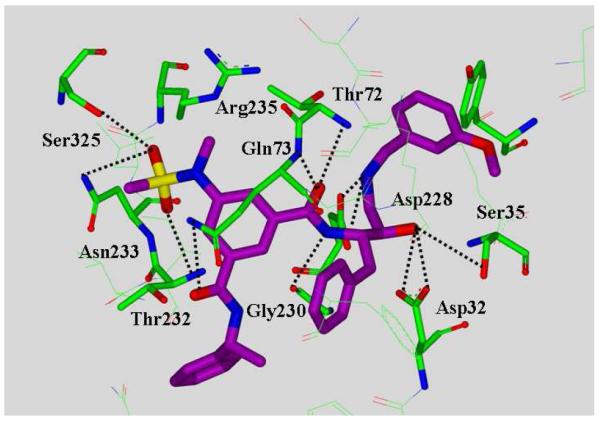

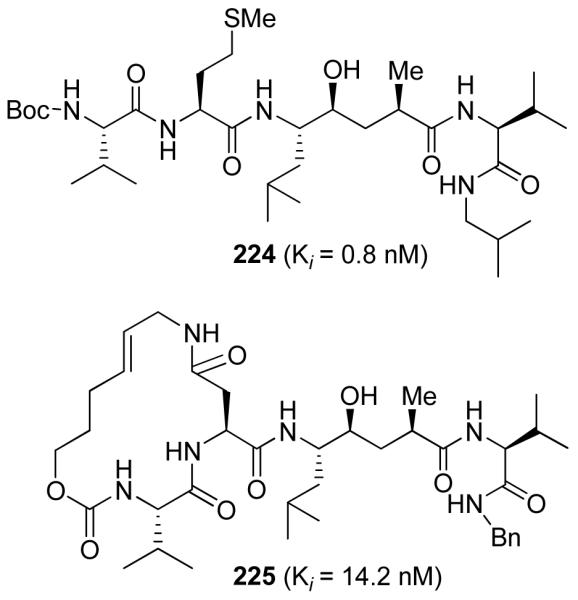

Another area of focus has been our design of β-secretase (memapsin 2) inhibitors for the possible treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Since late 1998, my laboratories have been involved in the design and synthesis of novel β-secretase inhibitors. β-Secretase is one of the two aspartyl proteases that cleave the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) to form a 40-42 amino acid amyloid-β-peptide (Aβ) in the human brain, a key event in the pathogenesis of AD.137 In collaboration with Dr. Jordan Tang at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, we have designed one of the first potent inhibitors of β-secretase based upon the specificity preference.138 Our design strategy was to first synthesize a Leu-Ala dipeptide isostere with the N-terminus being Fmoc protected and the hydroxyl group as a TBS-ether (222, Figure 50).138 This was used in solid-state peptide synthesis. Pseudopeptide 223 (OM 99-2) was identified by us as a very potent inhibitor of β-secretase.138 The X-ray structure of 223-bound β-secretase was then determined at 1.9 Å resolution by Jordan Tang and Lin Hong at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.139 This structure provided critical molecular insights into the β-secretase active site. Based upon this structure, we subsequently reduced the molecular size and designed a number of potent and selective β-secretase inhibitors. As shown, peptidic inhibitor 224 (Figure 51) has shown a Ki of 0.8 nM. We have also designed a series of macrocyclic amide-urethanes with varying ring sizes, a representative molecule is 225. Interestingly, however, none of these inhibitors have shown any selectivity against other human aspartic acid proteases, especially against memapsin 1 (BACE2) or Cathepsin D (CD).140 These proteases have specificity similarities with β-secretase and are involved in important physiological functions. Inhibition of these proteases would most likely lead to toxicity or consumption of inhibitor, necessitating large dose requirements. Our structure-based design efforts led to the synthesis of 226 (Figure 52), which is very potent against β-secretase and highly selective against β-secretase 2 (> 3800-fold) and Cathepsin D (> 2500-fold).141 An X-ray structure of the β-secretase-226 complex revealed a number of critical molecular interactions responsible for the observed selectivity.142 Subsequently, we designed and developed exceedingly potent small molecule inhibitors represented by 227 and 228. Inhibitor 228 inhibited Aβ production in animal models.143 An X-ray structure of 228-bound β-secretase (Figure 53) has shown ligand-binding site interactions in the β-secretase active site. A number of other lead structures identified in my laboratories have been further optimized for clinical development.144

Figure 50.

Structure of β-secretase inhibitor 223.

Figure 51.

Structure of β-secretase inhibitors 224 and 225

Figure 52.

Structure of β-secretase inhibitors 226-228

Figure 53.

An X-ray structure of 228-bound β-secretase

Conclusion

In the beginning of Fall 1994, I wanted to develop a strong research program that would harness the power of organic synthesis and address problems of today’s medicine. It all started with natural products. The structural complexity, specific stereochemistry, and unique beauty of natural products have always intrigued me. But more than just the synthesis of natural products, I have been interested in exploring their biology and medicinal potential. This crossover interest and focus led to some significant developments in my laboratories. Our synthesis of doliculide led us to define the biological mode of action of this exceedingly potent cytotoxic agent. In collaboration with Dr. Ernest Hamel at the National Cancer Institute, we determined that doliculide is an enhancer of actin assembly. This doliculide work led us to get involved with jasplakinolide synthesis and eventually persuaded us to pursue structural modification of jasplakinolide and design less complex structural variants. The synthesis of lasonolide enabled us to explore its biological mechanism of action with Dr. Yves Pommier of the NCI. As it turned out, lasonolide exerts its biological action via an unprecedented mechanism that promotes chromosome condensation. This work opened up many new possibilities of therapeutic applications. The exploration of the chemistry and biology of laulimalide, and peloruside A and B has been very intriguing on numerous counts. The synthesis of laulimalide led us to explore its biological potential. Our biological studies revealed that laulimalide is a microtubule stabilizing agent like paclitaxel. However, unlike many other natural products such as the epothilones, eleutherobin, or discodermolide, laulimalide does not bind to the taxoid site. It has a distinct drug-binding site that was hitherto unknown. We have further shown in collaboration with Drs. Ernest Hamel and Evi Giannakakou that laulimalide is potent against taxol and epothilone-resistant cell lines. In addition, we have shown that laulimalide is a rare microtubule stabilizing agent, which has shown synergistic effects with taxol. Our peloruside A and B syntheses also led us to explore their biological and medicinal potential. Incidentally, peloruside A and B bind to the same drug-binding site as laulimalide. This opened up an intriguing possibility of designing laulimalide- and peloruside A based novel microtubule stabilizing agents.

In conjunction with natural product syntheses, we have developed a number of new synthetic methodologies with the use of optically active cis-1-aminoindan-2-ol. These include asymmetric syn- and anti-aldol reactions and Diels-Alder, and hetero Diels-Alder reactions. Our ester-derived Ti-enolate-based anti- and syn-aldol processes are quite practical and the potential of these reactions has been demonstrated through the synthesis of numerous bioactive molecules. Our catalytic asymmetric reactions with amino-indanol-derived chiral bis-oxazoline ligands resulted in the development of effective Cu- and Mg-catalyzed Diels-Alder and hetero Diels-Alder reactions. This initial work laid the foundation for the development of many other asymmetric processes. The design and development of multicomponent reactions resulted in the generation of multiple stereocenters by carbon-carbon bond formation in a single operation. Our subsequent acyloxy carbenium ion-based ring opening reactions provided acyclic intermediates with multiple stereocenters and further expanded the synthetic potential of these multicomponent reactions.

The chemistry and biology of natural products brought a unique perspective and motivation toward the synthesis of natural product-derived templates, scaffolds, and ligands for aspartic acid proteases involved in the pathogenesis of many human diseases. It started out as a seemingly academic endeavor where we planned to mimic peptide and peptide-like bonds with stereochemically defined cyclic ethers inspired from natural products like the ginkgolides and monensin A. This turned out to be a very gratifying investigation. This endeavor led us to develop a series of exceptionally potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors incorporating conceptually new and unprecedented cyclic ether-based nonpeptidic ligands for the protease substrate binding site. Our analysis of X-ray structures of mutant proteases and molecular design strategy led us to develop and investigate the ‘backbone binding’ concept to combat drug-resistance. The design and development of darunavir as a first treatment of drug-resistant HIV is a truly humbling and gratifying experience. It is satisfying to know that darunavir may be helping many HIV/AIDS patients with few or no other possible treatment options.

Another significant development in my laboratories is our work in the design of β-secretase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. We designed the first substrate-based potent inhibitor for β-secretase. Our collaborative effort with Dr. Jordan Tang also led to determination of first X-ray structure of an inhibitor-bound β-secretase. This structure provided important drug-design templates for the structure-based design of β-secretase inhibitors. We then utilized our broad synthetic and molecular design experience to develop novel small molecule inhibitors exhibiting selectivity over other human aspartyl proteases. A number of inhibitors that evolved from my laboratories were further investigated for clinical development. Our broad synthetic experience complements our expanded design capabilities. This line of research also became a very motivating factor to graduate students and postdoctoral colleagues in my laboratories. We will continue to draw inspiration from nature and invoke the power of organic synthesis to address new challenges.

Figure 31.

Synthesis of the proposed structures of iriomoteolide 1a (28) and 1b (29).

Figure 40.

Chiral bis-oxazoline-Cu(OTf)2 catalyzed hetero-Diels-Alder reactions

Acknowledgement

I am very honored to receive the 2010 ACS Arthur C. Cope Scholar Award. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my many colleagues whose names appear on the cited publications. My sincere thanks and appreciation to Drs. Ernie Hamel, Hiroaki Mitsuya, Jordan Tang, and Irene Weber for our decade-long stimulating collaboration. Also, I would like thank my faculty colleagues and friends for their support. I want to express my gratitude and thanks to my family, wife Jody and three children for their love and support. They are my joy and spirit. Thanks to Heather Miller for her help with the preparation of this manuscript. The financial support by the National Institutes of Health (GM53386, GM55600, and AG18933) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- (1).Ghosh AK. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:2163–2176. doi: 10.1021/jm900064c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Danishefsky SL. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:1114–1116. doi: 10.1039/c003211p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lam KS. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gunatilaka AAL. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;69:509–526. doi: 10.1021/np058128n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Koehn FE, Carter GT. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrd1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Fenical W, Jensen PR. Nature Chem. Biol. 2006;2:666–673. doi: 10.1038/nchembio841. Wilson RM, Danishefsky SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8329–8351. doi: 10.1021/jo0610053. Paterson I, Anderson EA. Science. 2005;310:451–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1116364. Clardy J, Walsh C. Nature. 2004;432:829–837. doi: 10.1038/nature03194. and references cited therein.

- (4).(a) Newman DJ, Cragg GM. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Butler MS. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005;22:162–195. doi: 10.1039/b402985m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Haustedt LO, Mang C, Siems K, Schiewe H. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2006;9:445–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ghosh AK, Liu W-M, Xu Y, Chen Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996;35:74–76. doi: 10.1002/anie.199600741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ghosh AK, Liu W-M. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:6175–6182. doi: 10.1021/jo960670g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ghosh AK, Wang Y. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1999:3597–3601. doi: 10.1039/A907228D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ghosh AK, W M. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7908–7909. doi: 10.1021/jo971616i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ghosh AK, Wang Y. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:2789–2795. doi: 10.1021/jo9822378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ghosh AK, Fidanze S. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2405–2407. doi: 10.1021/ol000070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Ghosh AK, Liu C. Chem. Commun. 1999:1743–1744. doi: 10.1039/A904533C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Shurrush K, Kulkarni S. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4508–4518. doi: 10.1021/jo900642f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ghosh AK, Bischoff A. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1573–1575. doi: 10.1021/ol000058i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ghosh AK, Bischoff A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004;10:2131–2141. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ghosh AK, Bilcer G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)02246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ghosh AK, Kawahama R. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:5433–5435. doi: 10.1021/jo000507s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ghosh AK, Shirai M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6231–6233. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)01227-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ghosh AK, Liu C. Org. Lett. 2001;3:635–638. doi: 10.1021/ol0100069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Ghosh AK, Wang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:11027–11028. doi: 10.1021/ja0027416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Wang Y, Kim JT. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:8973–8982. doi: 10.1021/jo010854h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Ghosh AK, Bischoff A, Cappiello J. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2677–2681. doi: 10.1021/ol0101279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ghosh AK, Lei H. Tetrahedron: Asymm. 2003;14:629–634. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(03)00040-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Ghosh AK, Liu C. J. Am. Chem.Soc. 2003;125:2374–2375. doi: 10.1021/ja021385j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Liu C. In: Harmata M, editor. Vol. 5. Academic Press; 2004. p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ghosh AK, Xu X. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2055–2058. doi: 10.1021/ol049292p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ghosh AK, Swanson L. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:9823–9826. doi: 10.1021/jo035077v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Ghosh AK, Gong G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3704–3705. doi: 10.1021/ja049754u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Gong G. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:1085–1093. doi: 10.1021/jo052181z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ghosh AK, Xi K. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:1163–1170. doi: 10.1021/jo802261f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ghosh AK, Xi K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5372–5375. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ghosh AK, Moon DK. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2425–2427. doi: 10.1021/ol070855h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) Ghosh AK, Gong G. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1437–1440. doi: 10.1021/ol0701013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Gong G. Chem. Asian J. 2008;3:1811–1823. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ghosh AK, Xu C-X. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1963–1966. doi: 10.1021/ol900412u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ghosh AK, Xu X, Kim J-H, Xu C-X. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1001–1004. doi: 10.1021/ol703091b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Singh AJ, Xu C-X, Xu X, West LM, Wilmes A, Chan A, Hamel E, Miller JJ, Northcote PT, Ghosh AK. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2–10. doi: 10.1021/jo9021265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ghosh AK, Kulkarni S. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3907–3909. doi: 10.1021/ol8014623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ghosh AK, Li J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4164–4167. doi: 10.1021/ol901691d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ghosh AK, Yuan H. Org. Lett. 2010;12:3120–3123. doi: 10.1021/ol101105v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Stratmann K, Burgoyne DL, Moore RE, Patterson GML, Smith CD. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:7219–7226. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Evans DA. Asymmetric Synth. 1984;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Dai C-F, Cheng F, Xu H-C, Ruan Y-P, Huang P-Q. J. Comb. Chem. 2007;9:386–394. doi: 10.1021/cc060166h. and references cited therein.

- (39).O’Connell CE, Salvato KA, Meng Z, Littlefield BA, Schwartz EC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:1541–1546. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00243-7. and references cited therein.

- (40).Fuller RW, Nagarajan R. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1978;27:1981–1983. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(78)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Suhadolnik RJ. Nucleotides as Biological Probes. Wiley; New York: 1979. pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- (42).For synthesis of sinefungin analogs, see; Barton DHR, Gero SD, Lawrence F, Robert-Gero M, Quiclet-Sire B, Samadi M. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:63–67. doi: 10.1021/jm00079a007. Barton DHR, Gero SD, Negron G, Quiclet-Sire B, Samadi M, Vincent C. Nucleosides, Nucleotides. 1995;14:1619–1630. Peterli-Roth P, Maguire MP, Leon E, Rapoport H. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:4186–4193.

- (43).Knowles WS, Sabacky MJ, Vineyard BD, Weinkauff DJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:2567–2568. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Vorbruggen H, Krolikiewicz K, Bennua B. Chem. Ber. 1981;114:1234–1255. For recent application of this reaction, see Johnson CR, Esker JL, Van Zandt MC. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5854–5855.

- (45).Johnson RA, Sharpless KB. In: Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. Ojima I, editor. VCH Publishers; New York: pp. 103–158. 1193. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Caron M, Carlier PR, Sharpless KB. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:5185–5187. [Google Scholar]

- (47).(a) Dong H, Zhang B, Shi P-Y. Antiviral Res. 2008;86:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong H, Ren S, Zhang B, Ahou Y, Puig-Basagoiti F, Li H, Shi P-Y. J. Virology. 2008;82:4295–4307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02202-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).(a) Lodise TP, Patel N, Lomaestro BM, Rodvold KA, Drusano GL. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:507–514. doi: 10.1086/600884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rybak MJ, Lomaestro BM, Rotscahfer JC, Moellering RC, Jr., Craig WA, Billeter M, Dalovisio JR, Levine DP. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:325–327. doi: 10.1086/600877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Service RF. Science. 1995;270:724–727. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]