Abstract

Objective

Caregivers maintain critical roles in cancer patient care. Understanding cancer-related information effects both caregiver involvement and ability to have needs met. This study examines the mediating role caregiver’s clinic visit involvement has on the relationships between caregiver’s information competence and their need fulfillment and clinic visit satisfaction.

Methods

Secondary analysis of 112 advanced lung, breast, and prostate cancer caregivers participating in a large clinical trial. Caregiver information competence was assessed at pretest. Involvement, need fulfillment, and visit satisfaction were assessed immediately following the clinic appointment.

Results

Involvement correlated with information competence (r=.21,p<.05), need fulfillment (r=.48,p<.001), and satisfaction (r=.35,p<.001). The correlation between information competence and need fulfillment (r=.26,p<.01) decreased when controlling for involvement (r=.19,p=.049), demonstrating mediation, and accounted for 24.4% of the variance in need fulfillment. The correlation between information competence and satisfaction (r=.21,p=.04), decreased and was non-significant when controlling for involvement (r=.15,p=.11), demonstrating mediation, and accounted for 13% of variance in visit satisfaction.

Conclusion

Caregiver’s clinic visit involvement mediates the relationships between their information competence and their need fulfillment and visit satisfaction.

Practice Implications

Efforts to improve the caregiving experience, and potentially patient outcomes, should focus on system-wide approaches to facilitating caregivers’ involvement and assertiveness in clinical encounters.

1. Introduction

The diagnosis of advanced cancer often inflicts fear, despair, and hopelessness on patients and their families. Current medical and economic shifts have resulted in increased reliance on family caregivers throughout the continuum of cancer treatment and disease progression (1–7). Caregiving responsibilities include monitoring symptoms, dealing with unpleasant side effects, and providing emotional and instrumental support to the cancer patient. Caregivers also play an important role in information gathering and sharing, and the decision-making process (7,8). By providing assistance in the patient’s care, caregivers can also play an important role in the cancer patient’s ability to respond to and cope with the stress of living with the disease, its treatment, and progression (9). Accordingly, effective communication between not only patients and clinicians, but also including caregivers is critical in helping both patients and caregivers cope with the associated morbidity and mortality of advanced cancer.

To date, the research on caregivers of advanced cancer patients is limited, which is surprising since outcomes for both patient and caregiver are affected by how well the caregiver copes (10–16). Information seeking is one of the general coping strategies applied to address the changing needs of cancer (17). As such, information management can be a key factor in understanding the cancer diagnosis, making treatment decisions, and predicting the prognosis to better plan for future events (18). Eysenbach (19) summarizes findings that the provision of information to people facing cancer can promote a sense of control, self-care and participation, and the overall process of decision making, as well as lead to improved affect and quality of life. However, not all caregivers seek out health-related information and support. The extent to which one seeks information is dependent on many factors, including access to information sources, immediacy of information need, and personal characteristics of the information-seeker, such as self-efficacy to use information (20, 21).

Caregivers suffer from a lack of practical guidance, including poor information provision, inconsistent access to technical equipment and inadequate support from palliative care professionals (22). Such unmet needs are associated with increased caregiver burden (23–25). In one study 60–90% of patients and caregivers were found to need assistance in at least one area (26). Patients and their caregivers need clinical information, advice, and emotional support to respond to the rapidly changing physical, spiritual, and emotional burdens of advanced cancer. Our own research suggested high levels of informational need among caregivers, and the need for particular types of information differs significantly between specific cancer treatment experiences (27). For example, caregivers needed information about the disease itself more during treatment, whereas they sought more information about caregiving skills when discharging from a hospital stay to home. A key source of information for caregivers is undoubtedly the formal health care system that patients, and thus caregivers, encounter. Here the interpersonal exchange that patients and caregivers have with doctors and nurses is the standard mode of information transmission (28).

Many researchers agree that family members of cancer patients are often highly involved (29–33) however only a scant number of studies have examined these caregivers’ roles in the clinical interactions (32, 34–37). Such findings have demonstrated that caregivers are present at the majority of visits and that they ask more questions than the patients themselves. And while caregiver-specific research is limited, research has demonstrated that greater patient participation is associated with not only greater information exchanged between physicians and patients (e.g., references 38 and 39) but that the information is more patient-centered (37). Unfortunately, the information exchange among patients, caregivers and clinicians is frequently hindered by healthcare system-related factors and by the circumstances of the individuals in the patient-caregiver-clinician triad.

Research by Bowman (40) demonstrated that communicating with clinicians was a problem for more than 40% of caregivers. Often, patients and caregivers do not share physical and emotional concerns with the clinical team (41–49). When they do share their concerns, they often exclude psychosocial issues that are very important in cancer care (50, 51). However, sharing such concerns may be the only way for needs to get addressed in some cases. Broback and Bertero (52) illustrated that some caregivers believe they only received the necessary information to meet their needs because they had been proactive in requesting it.

Caregiver involvement in the clinic visit may be associated with an increased sense of feeling informed. Feeling informed has also been significantly associated with caregivers’ satisfaction with the clinician (53). However, it must be noted that many studies of caregivers’ satisfaction with information are conducted with bereaved caregivers, raising methodological questions of recall and the processing of information. Prospective studies, especially those that use observational techniques, may help to confirm these findings (28).

1.1 Study Overview and Hypotheses

This secondary analysis of previously obtained data aims to examine the relationship between caregivers’ information competence, their involvement within the patient’s oncology clinic visit, and their subsequent satisfaction with having care related needs met as well as with the clinic visit in general. It was hypothesized that greater information competence is associated with greater need fulfillment and greater visit satisfaction and that caregiver involvement would mediate this relationship, given those with greater competence are likely to be more involved and in turn have more needs met and concerns addressed by the clinical encounter.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

This study involves secondary analysis of data collected as part of two randomized clinical trials (RCT) that examined the effects of an online information and support resource, the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS) for caregivers of advanced lung, breast or prostate cancer. Caregivers were identified through patient nomination as the primary person who provides instrumental, emotional or financial support related to their cancer experience. Eligible caregivers were at least 18 years old and providing primary support for patients meeting the following disease criteria. Eligible lung cancer patients included those with non-small cell lung cancer at stage IIIA, IIIB, or IV. Breast cancer patients were eligible if they had a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer or of recurrent or metastatic inflammatory breast cancer, or those with a chest wall recurrence following mastectomy. Eligible prostate cancer patients had hormone refractory or metastatic prostate cancer. This study includes a subsample from those studies of 121 caregivers (72 lung, 16 breast, 24 prostate) who were audio taped and surveyed after accompanying the patient to a regularly scheduled clinic visit approximately one month after receiving either Internet control or the CHESS intervention for the main RCT.

2.2 Procedure

For the original RCT, patients were recruited from five major cancer centers in the Northeastern, Midwestern and Southwestern United States between September 2004 and April 2007. Having a caregiver was a study requirement. Patients appointed the caregiver they wished to include. Once consent was obtained, both patient and caregiver completed a pretest prior to randomization to treatment group. A subsample of participants completed in clinic visit assessments that included audio taping the clinic encounter and completing a post-visit survey at regularly scheduled visits occurring approximately one and three months post receiving access to the RCT study intervention. The focus of this study is the one month clinical encounter.

For audio taped clinic visit encounters, a study coordinator placed an audio cassette recorder in the exam room at the time the patient entered and started recording using voice-activated recording. At the end of the appointment, the coordinator collected the cassette recorder and asked the patient and caregiver (if present) to complete a brief survey. Most completed this survey while in the clinic, however participants were allowed to take it home and return by postage paid mail.

2.3 Measures

Information Competence collected at Pretest

A 5-item information competence scale assessed the caregiver’s perceived ability to obtain and use health care information (54). Items were scored from 0 to 4. A previous study reported reliability (Cronbach-alpha) from 0.75 to 0.79 (55). This sample demonstrated a Cronbach-alpha of .78. Mean score was used as the scale score, with higher scores indicating greater information competence.

Caregiver Involvement collected after clinic visit

A 6-item caregiver involvement scale was selected and modified from the Patient Involvement in Care scale (56) by altering appropriate point-of-reference wording. This scale assesses caregivers’ self-perception of their own level of involvement in the clinical encounter. Each item is scored 1 to 7. A “Does not apply” box can be checked if the caregiver thinks the item is not relevant to their situation. Mean score of all rated responses (excluding those marked “Does not apply”) was used as the scale score, with higher scores indicating greater involvement in the clinic visit. Cronbach-alpha for the modified instrument used with this sample was .81.

Caregiver Needs Fulfillment (CNF) collected after clinic visit

A 18-item need fulfillment scale was adapted based on modifications to the Family Inventory of Needs (57). While the original FIN required rating whether a need was met or unmet and then rating the level of importance of that need, our modification used the FIN items but changed the scaling to be a simple rating or the level to which the need was satisfied on a 1–7 scale. A “Does not apply” option was also available. Mean score of all rated responses (excluding those marked “Does not apply”) was used as the scale score, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction of needs being met. Cronbach-alpha for the modified instrument used with this sample was .88.

Caregiver Visit Satisfaction collected after clinic visit

A 7-item measure was developed addressing areas of satisfaction within the clinic visit. Items content included the clinical team addressing desired issues, meeting needs, treating with respect, and spending enough time, as well as the caregiver understanding information and the plan of care provided, and intention to carry out plan. Items are rated on a 1–7 scale. A “Does not apply” option was also available. Mean score of all rated responses (excluding those marked “Does not apply”) was used as the scale score, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction of needs being met. Cronbach-alpha for this study was .89.

2.4 Data Analysis

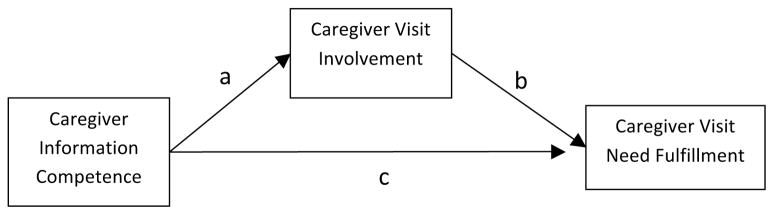

Data was analyzed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc; Chicago, IL: 2008). Descriptive analysis of demographic information and scale scores were reported for each cancer type. Assumptions of linearity, normality and homoscedascity were examined through scatter plots, histograms, and box-cox assessments and met for all scales except caregiver visit satisfaction, which had a negatively skewed and bimodal distribution. Statistical models and procedures (58) were employed to examine mediation effects of caregiver clinic visit involvement between information competence and either need fulfillment or visit satisfaction. This method has been applied in other caregiver literature (59). Based on similar methods, a mediation model was built (see Figure 1) and the following three conditions were examined in order to determine a mediation effect. The first condition requires that the correlation between independent variable (information competence) and mediator (caregiver involvement) must be significant (Path a). Second, the correlation between mediator (caregiver involvement) and dependent variable (need fulfillment or visit satisfaction) must be significant (Path b). Third, the partial correlation between independent variable and dependent variable controlling for the mediator must be significantly smaller than the simple correlation between these two variables (changes in Path c). Perfect mediation exists when the independent variable has no effect on the dependent variable when the mediator is controlled (58). Limitations of this method include low power and moderate risk of Type II error, inability to incorporate multiple intervening variables, and the exclusion of intervening variable models wherein the direct and indirect effects have opposite signs (MacKinnon, 2002). However, this method provides a suitable conservative means for exploratory analysis in this study which tests only a single mediating variable with both direct and indirect effects hypothesized as being positive. To test the need fulfillment model, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. However, in testing the visit satisfaction model, the non-normal distribution of the visit satisfaction scale required use of nonparametric statistics. Therefore, the Spearman correlation coefficient was utilized.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model

Separate regression analyses were conducted to show overall model performance. In the regression models, need fulfillment or visit satisfaction was entered as the dependent variable while information competence and caregiver involvement were entered as predictors. To address the non-normality issue of visit satisfaction, the rank transformed values were entered into regression model (61). Regression coefficients and adjusted power are reported.

3. Results

A total of 121 caregivers filled out after visit surveys. In the Caregiver Need Fulfillment and Caregiver Involvement Scales, caregivers may choose “Does not apply” as their answers. These answers were treated as valid rather than missing responses, however, they were not counted in scale mean calculation. Missingness criteria for scale calculation required at least 50% of all scale items to have valid responses in order to calculate a scale score. Three caregivers were excluded because of this rule. However, six other caregivers chose “does not apply” for all scale items and therefore their scale score is treated as missing given there is no value to calculate. In the end, 112 cases were kept for mediation analysis.

Demographic statistics are presented in Table 1. Average age of caregivers across cancer conditions is approximately 57 years. Generally, prostate cancer caregivers are older while breast cancer caregivers are younger. While all prostate and the majority of lung cancer caregivers are female, the majority of breast cancer caregivers are male. The majority of caregivers (81.3%) are patients’ spouse or partner, followed by adult child (16.8%). Descriptive statistics for model variables were reported in Table 2. There is no difference between cancer types for information competence, caregiver visit involvement, need fulfillment or visit satisfaction. Furthermore, none of the demographic variables correlated with need fulfillment or visit satisfaction.

Table 1.

|

Cancer Type |

All (N=112) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer (N=72) | Breast cancer (N=16) | Prostate Cancer (N=24) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean (S.D.) | 56.23 (12.8) | 52 (14.03) | 61.12(8.97) | 56.87(12.46) |

| Gender N(%) | ||||

| Male | 27 (37.5%) | 11 (68.8%) | 0 (0%) | 38 (33.9%) |

| Female | 45 (62.5%) | 5 (31.2%) | 24 (100%) | 76 (66.1%) |

| Total | 72 | 16 | 24 | 112 |

| Relation to Patients | ||||

| Spouse/Partner | 57 (79.1%) | 11 (68.7%) | 23 (95.8%) | 91 (81.3%) |

| Parent | 0 (0%) | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (4.2%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Adult Child | 12 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (10.7%) |

| Friend | 0 (0%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Other Family Member | 3 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| African American | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.2%) | 4 (3.6%) |

| Caucasian | 66 (94.3%) | 16 (100%) | 23 (95.8%) | 105 (95.5%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 70 (97.2%) | 16 (100%) | 24 (100%) | 110 (98.2%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.8%) |

Table 2.

Descriptive Analysis of Measure Scale Scores and Comparison by Cancer Type

|

Cancer Type |

F | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=112) | Lung (N=72) | Breast (N=16) | Prostate (N=24) | |||

| Caregiver Information Competence | ||||||

| Mean (S.D.) | 2.19 (0.73) | 2.06 (0.64) | 2.34 (0.93) | 2.46 (0.81) | 3.10 | 0.049 |

| Caregiver Visit Involvement | ||||||

| Mean (S.D.) | 4.87 (1.39) | 4.93 (1.36) | 4.21 (1.21) | 5.13 (1.49) | 2.38 | 0.097 |

| Caregiver Visit Need Fulfillment | ||||||

| Mean (S.D.) | 6.21 (0.54) | 6.22 (0.52) | 5.93 (0.53) | 6.35 (0.57) | 3.04 | 0.052 |

| Caregiver Visit Satisfaction | ||||||

| Mean (S.D.) | 6.45 (0.57) | 6.50 (0.51) | 6.14 (0.61) | 6.50 (0.69) | 2.71 | 0.071 |

3.1 Model Testing

While expected, it is noteworthy that the two dependent variables of interest, caregiver need fulfillment and visit satisfaction, are highly correlated (r=.82, p<.0001). Their co-linearity was prohibitive to testing these constructs within the same model, and rather suggested that these measures assessed overlapping or similar constructs. Therefore, we tested two separate models, using the same independent and mediator variables, for each dependent variable.

Model of Caregiver Need Fulfillment

The first and second conditions of mediation analysis are satisfied with significant correlations between information competence and caregiver visit involvement (r=0.21, p=.03), and between caregiver visit involvement and needs fulfillment (r=0.48, p<0.001). The partial correlation between caregiver information competence and need fulfillment controlling for caregiver involvement is r=0.19, p=0.049. This satisfies the third criteria for mediation in that the degree of relationship as well as the significance is reduced as compared to the simple correlation (r=0.26, p=0.006). The mediation effect of caregiver visit involvement exists as a partial rather than perfect mediation because, while much of the relationship is accounted for by the clinic visit involvement, some residual relationship remains. Regression coefficients for the two predictors are listed in Table 3. The regression analysis shows that the whole mediation model accounts for 24.4% variance of dependent variable, caregiver visit need fulfillment (P<0.001).

Table 3.

Regression Model of Caregiver Need Fulfillment

| Overall Model | Adjusted R2 = 0.244 |

|---|---|

| Beta | |

| Information Competence | 0.168 (p=0.049) |

| Caregiver Involvement | 0.445 (p<0.001) |

Model of Caregiver Visit Satisfaction

The first and second conditions of mediation analysis are satisfied with significant correlation between information competence and caregiver visit involvement (r=0.21, p=.03), and between caregiver visit involvement and visit satisfaction (r=.35, p<.001). The partial correlation between caregiver information competence and visit satisfaction controlling for caregiver involvement is r=0.15, p=.11. This satisfies the third criteria for mediation in that there is no longer a relationship between information competence and visit satisfaction when controlled for visit involvement (compared to the simple correlation: r=.19; p=0.04), therefore, reaching perfect mediation criteria. Regression coefficients for the two predictors are listed in Table 4. The regression analysis shows that the mediation model accounts for 13% variance of dependent variable, caregiver visit satisfaction (P<0.001).

Table 4.

Regression Model of Caregiver Visit Satisfaction

| Overall Model | Adjusted R2 = 0.130 |

|---|---|

| Beta | |

| Information Competence | 0.144 (p=0.113) |

| Caregiver Involvement | 0.326 (p<0.001) |

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

The results of this study supported hypotheses that caregiver clinic visit involvement mediates the relationship between caregiver health information competence and need fulfillment as well as visit satisfaction. Specifically, greater caregiver involvement was associated with increased need fulfillment, and for clinic visit satisfaction, this relationship existed regardless of caregiver information competence.

For caregivers, the ability to make use of health related information increases the likelihood of participation within the clinic visit. Such clinic visit participation may be a critical factor in caregivers getting their information needs met and being satisfied with the clinical encounter. Accordingly, interventions that facilitate caregiver information competence may help caregivers better navigate the cancer experience. However, information competence is not enough, and caregivers may benefit equally, if not more from, interventions that facilitate their active participation in the clinical encounter. As clinic visits likely serve as the main portal for care information and guidance, active engagement at these visits (by, for example, being prepared to ask questions, asserting their own or the patient’s needs or concerns, and being persistent in getting answers) may set the stage for other caregiving competencies. Future research examining the causal links in these relationships, that also include specific visit behaviors of caregivers and other key personnel (i.e., patients, physicians, nurses), could help clarify the necessary conditions for improved caregiver clinic visit participation and outcomes.

Furthermore, it is critical to examine the impact of caregiver involvement on patient outcomes, including not only visit outcomes like need fulfillment and visit satisfaction, but also broader issues of care experience, such as efficacy for managing patient symptoms at home, patient’s symptom burden, or caregiver’s burden. Research examining the dynamic nature of balancing patient and caregiver clinic visit behaviors and satisfaction outcomes would offer more insight regarding potential benefits and negative consequences of such caregiver involvement for all parties involved. The nature of this being a secondary analysis study also poses limitations in the data available for analysis. For example, comparable patient data was not available. To best understand the clinical encounter, similar mediation models should be tested using patient data, as well as models that combine patient and caregiver data. Similarly, clinician roles and perceptions of visit engagement are also critical factors in visit dynamics and outcomes. While this study serves as preliminary work in the foundation of caregiver roles in the clinic visit encounter, much more work is needed in evaluating these systems as a whole. For example, further research could test models of caregiver involvement on patient need fulfillment and visit satisfaction, potentially using both caregiver self measures as well as patient’s and clinician’s perceptions of caregiver’s involvement. Furthermore, more objective measures of caregiver involvement (i.e., third party ratings of clinic encounters) may offer additional insights. Such measures would minimize the potential for response bias where subjects rate all aspects of the visit highly based on a heuristic of their care experience rather than actual interactions at a single encounter.

As these models indicate that other factors are also involved in determining caregiver need fulfillment and satisfaction, further work is needed to test such potential factors. Although demographic variables were not associated with the outcomes in this sample, there may be some such variables that are important that could not be tested here, such as race/ethnicity, length of relationship with the clinician, and the type of visit or specific nature of content addressed (e.g., scan results, treatment follow-up, or treatment decision making).

One strength of this study was its use of prospective rather than retrospective data, whereas many caregiver studies rely on retrospective and often post-bereavement report which is increasingly susceptible to bias. Even so, as visit involvement and satisfaction measures were assessed at the same time, the potential exists for response bias such that those who generally perceived the visit as positive are likely to endorse all aspects of the visit as positive. While possible, this is less likely to be the case given the moderate relationships, whereas such a response bias might yield even stronger relationships.

The best fit of the model was for caregiver visit satisfaction, and to a lesser extent the model fit for need fulfillment. After controlling for caregiver involvement, the partial correlations for information competence and visit satisfaction were no longer significant, suggesting “perfect” mediation, whereas visit involvement was a partial mediator for need fulfillment. It must be noted that correlations were modest (r ranging from 0.19 – 0.48), suggesting other factors are also contributing to variance in these constructs, which is supported by regression analysis revealing these models address 13 and 24% of the variance in need fulfillment and visit satisfaction, respectively. The lack of perfect mediation in the need fulfillment model is typical of psychosocial phenomena which often have multiple causes. Accordingly, it is often unrealistic to assume the need to eliminate all levels of relation between the independent and dependent variables (58). The reduction in significance does demonstrate that caregiver involvement, while potent, is neither necessary nor sufficient for an effect in need fulfillment to occur. It is also noteworthy that while the methods utilized for this analysis have low power to detect actual effects (60), these mediation effects were still apparent, attesting to their strength.

4.2 Conclusion

Information competence facilitates caregiver participation in the clinic visit. Those who perceive greater self-efficacy to acquire and make sense of health information are more likely to ask questions and seek information from the clinician. However, it is the level of caregiver involvement in the clinical encounter that is a critical element in both having the caregiver’s needs met, as well as visit satisfaction. Those who are more highly involved in the visit are more likely to either be assertive in having the clinical team meet their needs, or to perceive the visit positively in terms of clinician interaction (e.g. addressed desired issues) and visit outcomes (i.e., agreement with treatment plan). The clinical system needs to recognize the caregiver’s role in patient care, and partner with the caregiver as well as the patient to deliver patient and family centered care. Designing a system that not only supports but fosters caregiver engagement can increase caregiver satisfaction and need fulfillment. While it remains to be tested how such interventions might impact patient outcomes, some evidence indicates that empowering caregivers can lead to better patient care (62).

4.3 Practice Implications

Clinical Practice needs to recognize the role of the caregiver in the clinical visit setting, and how their participation in the visit impacts caregiver need fulfillment and satisfaction, which sustain patient care. Accordingly, clinical settings need to consider how to facilitate caregiver involvement, through interventions targeted either at the caregivers or the clinical care system. While caregivers may learn skills such as coming prepared with questions or asserting their needs, they also need to be invited to do by a system that is prepared to respond to them effectively. Clinical settings need to evaluate the factors that serve as facilitators or barriers to the caregivers of the patients they serve, including the environment (i.e., is there adequate and functional seating for the caregiver in the exam room?), people (i.e., what are the perceptions of power in the relationship and communication style?), tasks being done (i.e., is the focus on collecting vitals and data on patient’s current presentation with less attention to soliciting input on caregiver’s perspective of what has been happening at home?), technologies (i.e. can interactive technologies bridge gaps in communication while at home?), and the organization (i.e., to what degree do privacy regulations form barriers to caregiver communication of patient care information?)(63).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Funding for this study was provided through grants from the National Cancer Institute (1 P50 CA095817-01A1) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (RO1 NR008260-01), with no involvement in study design, conduct, or manuscript preparation. NCI requested this special journal edition to highlight the work of their Centers of Excellence in Cancer Communication Research.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lori L. DuBenske, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies, 1513 University Dr, ME 4155A, Madison, WI 53726 USA

Ming-Yuan Chih, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies.

David H. Gustafson, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies

Susan Dinauer, University of Wisconsin – Madison, Center for Health Enhancement Systems Studies.

James F Cleary, University of Wisconsin–Madison, School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

- 1.Hileman JW, Lackey NR, Hassein RS. Identifying the needs of home caregivers of patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1992;19:771–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longman AJ, Atwood JR, Blank-Sherman J, Benedict J, Shang TC. Care needs of home-based cancer patients and their caregivers: Quantitative findings. Cancer Nurs. 1992;15:182–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stetz KM, Hanson WK. Alterations in perceptions of caregiving demands in advanced cancer during and after the experience. Hosp J. 1992;8:21–34. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1992.11882728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houts P, Nezu A, Nezum C, Bucher J. The prepared family caregiver: A problem-solving approach to family caregiver education. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barg F, Pasacreta J, Nuamah I, Robinson K. A description of a psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers of cancer patients. J Child Fam Nurs. 1998;4:394–413. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arno PS, Levine C, Memmott MM. The economic value of informal caregiving. Health Aff. 1999;18:182–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speice J, Harkness J, Laneri H, Frankel R, Roter D, Kornblith AB, et al. Involving family members in cancer care: Focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psychooncology. 2000;9:101–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<101::aid-pon435>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James N, Daniels H, Rahman R, McConkey C, Derry J, Young A. A study of information seeking by cancer patients and their carers. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19:356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardwick C, Lawson N. The information and learning needs of the caregiving family of the adult cancer patient. Eur J Cancer Care. 1995;4:118–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1995.tb00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith E, Redman R, Burns T, Sagert K. Perceptions of social support among patients with recently diagnosed breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer: An exploratory study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1985;3:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuling S, Winefield H. Social support and recovery after surgery for breast cancer: Frequency and correlates of supportive behaviors by family, friends and surgeon. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:385–92. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pistrang N, Barker C. The caregiver relationship in psychological response to breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:789–97. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00136-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northouse L, Peters-Golden H. Cancer and the family: Strategies to assist spouses. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1993;9:74–82. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(05)80102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters-Golden H. Varied perceptions of social support in the illness experience. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:463–91. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitaliano P. Psychological and physical concomitants of caregiving; Introduction to special issue. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:75–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02883322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz R, Beach S. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–19. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisman AD. Coping with Cancer. MacGraw Hill; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brashers DE, Goldsmith DJ, Hsieh E. Information seeking and avoiding in health contexts. Hum Commun Res. 2002;28:258–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eysenbach G. The impact of the Internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:356–71. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.6.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JD, Meischke H. Women’s preferences for cancer information from specific communication channels. Am Behav Sci. 1991;34:742. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Zuuren FJ, Wolfs HM. Styles of information seeking under threat: personal and situational aspects of monitoring and blunting. Pers Individ Dif. 1991;12:141–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bee PE, Barnes P, Luker KA. A systematic review of informal caregivers’ needs in providing home-based end-of-life care to people with cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1379–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharpe L, Butow P, Smith C, McConnell D, Clarke S. The relationship between available support, unmet needs and caregiver burden in patients with advanced cancer and their carers. Psychooncology. 2005;14:102–14. doi: 10.1002/pon.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O’Leary JR, Byers AL. Unmet Desire for Caregiver-Patient Communication and Increased Caregiver Burden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim Y, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Larson MR. Levels of depressive symptoms in spouses of people with lung cancer: Effects of personality, social support, and caregiving burden. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:123–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuBenske LL, Wen KY, Gustafson DH, Guarnaccia CA, Cleary JF, Dinauer SK, McTavish FM. Caregivers’ needs at key experiences of the advanced cancer disease trajectory. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris SM, Thomas C. The need to know: informal carers and information. Eur J Cancer Care. 2002;11:183–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2002.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albrecht TL, Blanchard C, Ruckdeschel JC, Coovert M, Strongbow R. Strategic physician communication and oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3324–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchard CG, Albrecht TL, Ruckdeschel JC. Patient-family communication with physicians. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, Kaplan De-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the family. Wiley; London: 2000. pp. 477–95. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doherty WJ. Family intervention in health care. Family Relations. 1985;34:129–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labrecque MS, Blanchard CG, Ruckdeschel JC, Blanchard EB. The impact of family presence on the physician–cancer patient interaction. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(11):1253–61. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90073-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lederberg MS. The family of the cancer patient. In: Holland J, editor. Psychooncology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 981–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beisecker AE, Moore AP. Oncologists’ perceptions of the effects of cancer patents’ companions on physician–patient interaction. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1994;12(1):23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delvaux N, Merckaert I, Marchal S, Libert Y, Conradt S, Boniver J, et al. Physicians’ communication with a cancer patient and a relative: A randomized study assessing the efficacy of consolidation workshops. Cancer. 2005;103:2397–411. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Street RL, Gordon HS. Companion participation in cancer consultations. Psychooncology. 2008;17:244–51. doi: 10.1002/pon.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eggly S, Penner LA, Greene M, Harper FWC, Ruckdeschel JC, Albrecht TL. Information seeking during “bad news” oncology interactions: Question asking by patients and their companions. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2974–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cegala DJ, McClure L, Marinelli TM, Post DM. The effects of communication skills training on patients’ participation during medical interviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;41:209–22. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Street RL. Information-giving in medical consultations: The influence of patients’ communication styles and personal characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:541–8. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90288-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman KF, Rose JH, Radziewicz RM, O’Toole EE, Berila RA. Family caregiver engagement in a coping and communication support intervention tailored to advanced cancer patients and families cancer. Nursing. 2009;32:73–81. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000343367.98623.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dar R, Beach CM, Barden PL, Cleeland CS. Cancer pain in the marital system: a study of patients and their spouses. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(92)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roter D, Hall JA. Doctors talking with patients/patients talking with doctors: improving communication in medical visits. Westport (CN): Auburn House; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Von Roenn JH, Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Pandya KJ. Physician attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: A survey from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:121–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-2-199307150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:285–94. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maguire P. Improving communication with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1415–22. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Street R., Jr . Active patients as powerful communicators: The linguistic foundation of participation in health care. In: Robinson WP, Giles H, editors. The new handbook of language and social psychology. 2. Chichester (England): Wiley; 2001. pp. 541–60. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cull A, Stewart M, Altman DG. Assessment of and intervention for psychosocial problems in routine oncology practice. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:229–35. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osoba D. Rationale for the timing of health-related quality-of-life (HQL) assessments in oncological palliative therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 1996;22(Suppl A):69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(96)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broback G, Bertero C. How next of kin experience palliative care of relatives at home. Eur J Cancer Care. 2003;12:339–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fakhoury WKH, McCarthy M, Addington-Hall JM. Determinants of informal caregivers’ satisfaction with services for dying cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:721–31. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ende-Murphy K. unpublished PhD thesis. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 1996. The relationship ofelf-directed learning,self-efficacy, and health value in young women with cancer using a computer health education program. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw BR, Han JY, Baker T, Witherly J, Hawkins RP, McTavish F, Gustafson DH. How women with breast cancer learn using interactive cancer communication systems. Health EducRes. 2007;22:108. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lerman CE, Brody DS, Caputo GC, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, Wolfson HG. Patients’ perceived involvement in care scale: Relationship to attitudes about illness and medical care. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:29–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02602306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kristjanson LJ, Atwood J, Degner LF. Validity and reliability of the Family Inventory of Needs (FIN): Measuring the care needs of families of advanced cancer patients. J Nurs Meas. 1995;3:109–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cameron JI, Franche RL, Cheung AM, Stewart DE. Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;94:521–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iman RL, Conover W. The use of rank transformation in regression. Technometrics. 1979;21:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schubart JR, Kinzie MB, Farace E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: Family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro Onco. 2008;10:61–72. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, Gurses AP, Alvarado CJ, Smith M, Flatley Brennan P. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(Suppl):i50–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]