Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our objective was to determine whether the pregnancy and high altitude long-term hypoxia (LTH)-mediated changes in uterine artery (UA) contractility were regulated by KATP and L-type Ca2+ channel activities.

STUDY DESIGN

UAs were isolated from nonpregnant (NPUA) and near-term pregnant (PUA) ewes that had been maintained at sea level (~300 m) or exposed to high altitude (3801 m) for 110 days. Isometric tension was measured in a tissue bath.

RESUTS

Pregnancy increased diazoxide- but not verapamil-induced relaxations. LTH attenuated diazoxide-induced relaxations in PUA, but enhanced verapamil-induced relaxations in NPUA. Diazoxide decreased the maximal response (Emax) of phenylephrine (PE)-induced contractions in PUA but not NPUA in normoxic sheep. In contrast, diazoxide had no effect on PE-induced Emax in PUA but decreased it in NPUA in LTH animals. Verapamil decreased the Emax and pD2 (−logEC50) of PE-induced contractions in both NPUA and PUA in normoxic and LTH animals, except NPUA of normoxic animals in which verapamil showed no effect on the pD2.

CONCLUSIONS

The results suggest that pregnancy selectively increases KATP, but not L-type Ca2+ channel activity. LTH decreases the KATP channel activity, which may contribute to the enhanced uterine vascular myogenic tone observed in pregnant sheep at high altitude hypoxia.

Keywords: high altitude hypoxia, pregnancy, ovine uterine artery contractility, KATP channel, L-type Ca2+ channel activity

Introduction

Vascular smooth muscle cells express a diverse array of ion channels that play an important role in the function of vessels in both health and disease. Potassium (K+) channels are the dominant ion channels expressed in the plasma membrane of arterial smooth muscle cells and contribute mainly to the regulation of smooth muscle tone.1–3 Activation of K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle leads to decreased vascular tone, with an increase in blood flow and a decrease in blood pressure. Inhibition of K+ channel activity leads to vasoconstriction. In vascular smooth muscle cells, four types of K+ channels (KV, KCa, KATP, and KIR channels) have been identified to regulate the membrane potential, which in turn controls the activity of L-type Ca2+ channels and vascular tone.2 K+ channels may be involved in the actions of a variety of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors, and their activities and functions may be altered in patho- and/or physiological conditions.3

Pregnancy is associated with a significant decrease in uterine vascular tone, with a striking increase in uterine blood flow. The adaptation of uterine vascular tone to pregnancy is complex, and the mechanisms that contribute to the profound changes during pregnancy are poorly understood. Potassium channels may be the targets and the key mediators responsible for these pregnant-mediated alterations. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that Ca2+-activated K channel (KCa) in sheep4 and ATP-sensitive K channel (KATP) in guinea pigs5 play important roles in the regulation of uterine blood flow during pregnancy. Previous studies also have indicated that enhanced K+ channel activity contributed to the vascular changes associated with normal pregnancy, e.g., the fall in systemic and local vascular resistances, and the attenuated pressor responses to several vasoconstrictors.4–7

Chronic hypoxia during the course of pregnancy is one of the most common insults to the maternal cardiovascular system and fetal development, and is thought to be associated with increased risk of preeclampsia and fetal intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).8, 9 However, in our high altitude sheep animal model, chronic hypoxia alters maternal and fetal cardiovascular systems without significant IUGR, suggesting a compensatory adaptation to high altitude hypoxia in sheep, which are similar to those observed in well-adapted human populations such as Tibetans and Andeans. Previous studies have demonstrated that long-term hypoxia (LTH) has profound effects on maternal uterine artery contractility.10–12 However, the mechanisms underlying LTH-mediated uterine contractility are poorly understood. Among the four types of K+ channels, the KATP channel has been demonstrated to be involved in the hypoxia-mediated contractility.13–15 Although the role of KATP channels in hypoxia-mediated contractility is well established at other tissues, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the relative roles of KATP channels in high-altitude long-term hypoxia (LTH)-mediated uterine artery contractility during pregnancy. Given that LTH enhances ovine uterine artery myogenic contractions during pregnancy,10 we tested the hypothesis that the LTH-associated enhanced uterine artery vascular tone is secondary to altered KATP channel function during pregnancy. In addition, we also determined the L-type Ca2+ channel activity to test whether LTH alters this channel activity in uterine artery smooth muscle cells during pregnancy. To test our hypothesis, we used sheep as the animal model. The sheep were divided into four groups: normoxic nonpregnant sheep, normoxic pregnant sheep, LTH nonpregnant sheep, and LTH pregnant sheep. The effects of KATP channel and L-type Ca2+ channel on uterine vascular contractility were determined among those four groups of animals.

Materials and Methods

Tissue preparation

As previously described,12 nonpregnant and time-dated pregnant sheep were obtained from the Nebeker Ranch in Lancaster, CA (altitude: ~300 m; arterial PaO2: 102 ± 2 Torr). For chronic hypoxic treatment, nonpregnant and pregnant (30 days of gestation) animals were transported to the Barcroft Laboratory, White Mountain Research Station, Bishop, CA (altitude, 3,801 m; maternal PaO2, 60 ± 2 Torr) and maintained there for ~110 days. Animals then were transported to the laboratory at Loma Linda University. Shortly after arrival, we placed a tracheal catheter in the ewe, through which N2 flowed at a rate to maintain PaO2 at ~60 Torr, and this was maintained until the time of the experimental study. Ewes were anesthetized with thiamylal (10 mg/kg) administered via the external left jugular vein. The animals then were intubated and anesthesia was maintained with 1.5% to 2.0% halothane in oxygen throughout surgery. An incision in the abdomen was made and the uterus exposed. The uterine arteries were isolated and removed without stretching and were placed in a modified Krebs’ solution (pH 7.4) of the following composition (in mM): 115.21 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.80 CaCl2, 1.16 MgSO4, 1.18 KH2PO4, 22.14 NaHCO3, 0.03 EDTA, and 7.88 dextrose, oxygenated with a mixture of 95% O2-5% CO2. After removal of the tissues, animals were killed with an overdose of the proprietary euthanasia solution, Euthasol (pentobarbital sodium 100 mg/kg and phenytoin sodium 10 mg/kg, Virbac, Ft Worth, TX). All procedures and experimental protocols were approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Contraction studies

The fourth generation branches (~0.8 mm in external diameter) of main uterine arteries were separated from the surrounding tissue, and cut into 2-mm ring segments. The small branches of uterine arteries were chosen, because they are much closer in characteristics to arterioles and play a substantial role in vascular resistance. Isometric tension was measured in the Krebs solution in a tissue bath at 37°C, as described previously.16 Briefly, each ring was equilibrated for 60 min and then gradually stretched to the optimal resting tension, as determined by the tension that developed in response to 120 mM KCl added at each stretch level. Tissues then were stimulated with cumulative additions of phenylephrine in approximate one-half log increments to generate a concentration-response curve, and contractile tensions were recorded with an online computer. After phenylephrine was washed away, tissues were relaxed to the baseline and were recovered at the resting tension for 30 min. The second concentration-response curves of phenylephrine-induced contractions then were repeated in the absence or presence of KATP channel blocker (glibenclamide, 10 μM; Research Biochemical International, Natick, MA, USA), or KATP channel opener (diazoxide, 10 μM; Research Biochemical International, Natick, MA, USA) or a L-type Ca2+ channel blocker (verapamil, 10 μM; Research Biochemical International, Natick, MA, USA) for 20 min. For relaxation studies, the tissues were pre-contracted with submaximal concentrations of phenylephrine, followed by diazoxide, and verapamil, respectively, added in a cumulative manner. EC50 values for the agonist in each experiment were taken as the molar concentration at which the contraction-response curve intersected 50% of the maximum response, and were expressed as pD2 (−logEC50) values.

Simultaneous measurement of [Ca2+]i and tension

Simultaneous recordings of contraction and [Ca2+]i (fura-2 signal Rf340/f380) in the same tissue were conducted as described previously.12 Briefly, the arterial ring was attached to an isometric force transducer in a 5-ml tissue bath mounted on a CAF-110 intracellular Ca2+ analyzer (model CAF-110, Jasco; Tokyo, Japan). The tissue was equilibrated in Krebs buffer under a resting tension of 0.5 g for 40 min. The ring was then loaded with 5 μM fura 2-AM for 3 h in the presence of 0.02% Cremophor EL at room temperature (25°C). After loading, the tissue was washed with Krebs solution at 37°C for 30 min to allow for hydrolysis of fura-2 ester groups by endogenous esterase. Contractile tension and fura-2 fluorescence were measured simultaneously at 37°C in the same tissue. The tissue was illuminated alternatively (125 Hz) at excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm, respectively, by means of two monochromators in the light path of a 75-w xenon lamp. Fluorescence emission from the tissue was measured at 510 nm by a photomultiplier tube. The fluorescence intensity at each excitation wavelength (F340 and F380, respectively) and the ratio of these two fluorescence values (Rf340/380) were recorded with a time constant of 250 ms and stored with the force signal on a computer.

Data analysis

Concentration-response curves were analyzed by computer-assisted nonlinear regression to fit the data using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Results were expressed as means ± SEM obtained from the number (n) of experimental animals given. Differences were evaluated for statistical significance (P < 0.05) by two-way ANOVA followed by the Newman-Keuls post hoc test.

Results

Effect of LTH on KATP-mediated relaxation in uterine arteries

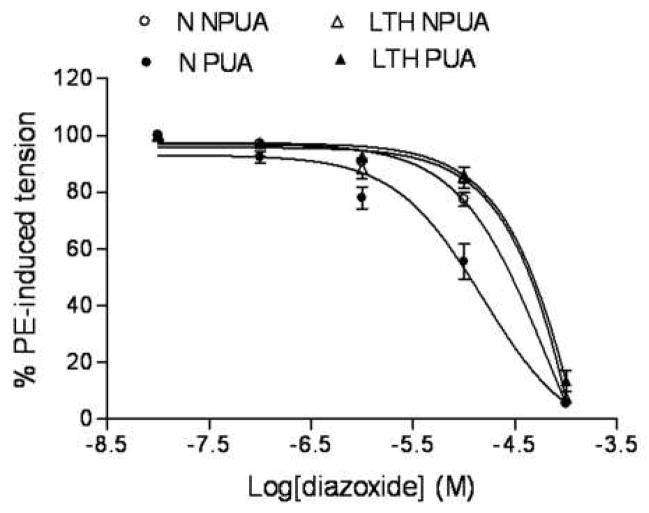

As shown in Figure 1, diazoxide, a KATP channel opener, produced dose-dependent relaxations of phenylephrine-pre-contracted uterine arteries in both normoxic and LTH sheep. In normoxic animals, diazoxide-induced vascular relaxations were more potent in pregnant than in nonpregnant uterine arteries (pD2 value: 4.8 ± 0.2 vs. 4.2 ± 0.2, P < 0.05). In hypoxic animals, LTH significantly decreased the potency of diazoxide-induced vascular relaxations in pregnant uterine arteries (pD2 value: 4.8 ± 0.2 vs. 3.6 ± 0.6, P < 0.05), but not in nonpregnant uterine arteries (pD2 value: 4.2 ± 0.2 vs. 3.5 ± 1.2, P > 0.05). Furthermore, LTH eliminated the difference of diazoxide-induced relaxations between pregnant and nonpregnant uterine arteries (pD2 value: 3.6 ± 0.6 vs. 3.5 ± 1.2, P > 0.05).

Figure 1. Diazoxide-mediated relaxation of uterine ateries.

Concentration-dependent relaxation induced by the KATP channel opener, diazoxide were obtained with phenylephrine (1 μM)-precontracted uterine arteries in normoxic nonpregnant (N NPUA), pregnant (N PUA), LTH nonpregnant (LTH NPUA) and LTH pregnant (LTH PUA) sheep. Concentration-response curves were analyzed by computer-assisted nonlinear regression to fit the data using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Data are means ± SEM of the tissues from 5 to 13 animals.

Effect of LTH on L-type Ca2+ channel activity in uterine arteries

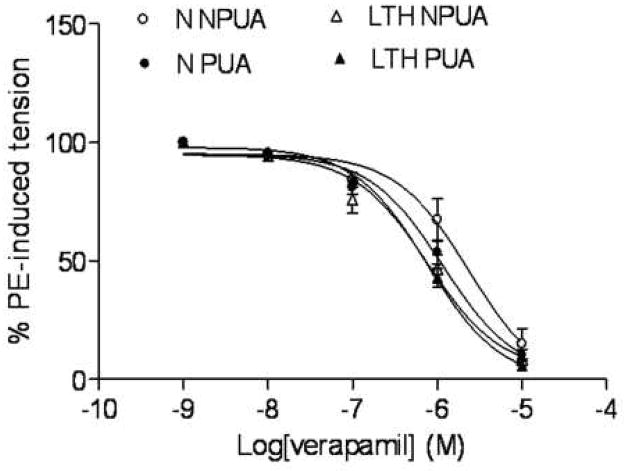

As shown in Figure 2, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, verapamil produced dose-dependent relaxations of phenylephrine-pre-contracted uterine arteries in both normoxic and LTH sheep. Verapamil-induced relaxations had no significant difference between nonpregnant and pregnant uterine arteries in either normoxic (pD2 value: 5.6 ± 0.2 vs. 5.9 ± 0.09, P > 0.05) or LTH (pD2 value: 6.1 ± 0.2 vs. 6.1 ± 0.05, P > 0.05) animals. However, LTH significantly enhanced verapamil-induced relaxations in nonpregnant (pD2 value: 5.6 ± 0.2 vs. 6.1 ± 0.2, P < 0.05) but not in pregnant (pD2 value: 5.9 ± 0.09 vs. 6.1 ± 0.05, P > 0.05) uterine arteries.

Figure 2. Verapamil-mediated relaxations of uterine ateries.

Concentration-dependent relaxation induced by the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, verapamil were obtained with phenylephrine (1 μM)-precontracted uterine arteries in normoxic nonpregnant (N NPUA), pregnant (N PUA), LTH nonpregnant (LTH NPUA) and LTH pregnant (LTH PUA) sheep. Concentration-response curves were analyzed by computer-assisted nonlinear regression to fit the data using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Data are means ± SEM of the tissues from 6 to 13 animals.

Role of KATP channel in α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contractions of uterine arteries

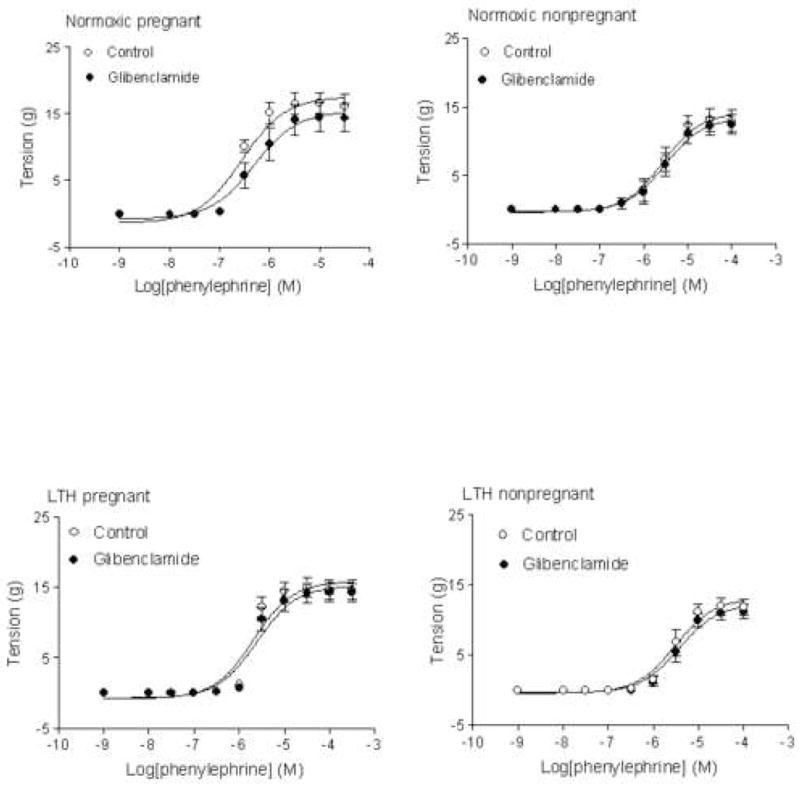

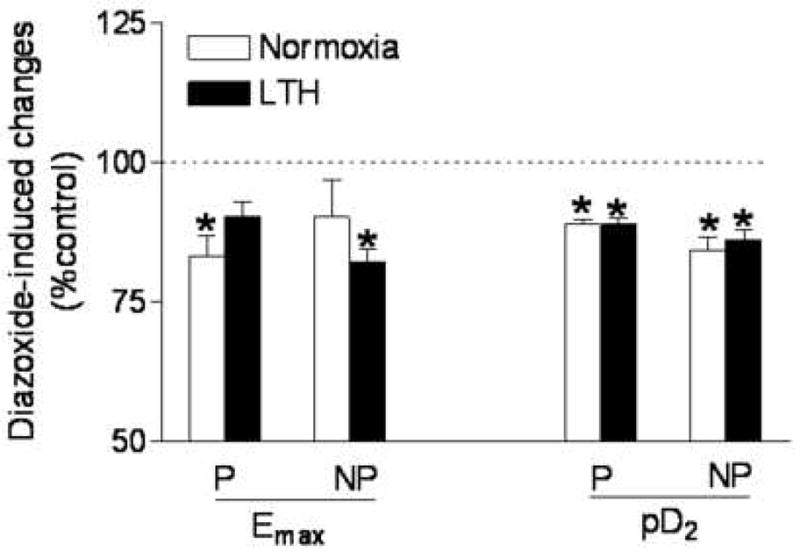

As shown in Figure 3, inhibition of KATP channel by glibenclamide showed no significant effect on α1-adrenoceptor agonist, phenylephrine-induced contractions in either pregnant or nonpregnant uterine arteries from either normoxic or LTH animals. However, activation of KATP channel by diazoxide differentially affected phenylephrine-induced contractions of both pregnant and nonprenant uterine arteries from normoxic and LTH animals (Figure 4). As show in Figure 4, pretreatment with diazoxide significantly inhibited the maximal responses (Emax) of phenylephrine-induced concentration-response curves in pregnant but not in nonpregnant uterine arteries from normoxic animals. In contrast to normoxic animals, diazoxide did not significantly inhibit the Emax in pregnant but inhibited it in nonpregnant uterine arteries from LTH animals. Figure 4 also shows the pD2 values of phenylephrine-induced concentration- response curves of uterine arteries in absence (control) and presence of diazoxide. Diazoxide significantly inhibited the pD2 values in both pregnant and nonpregnant uterine arteries from both normoxic and LTH animals.

Figure 3. Effect of glibenclamide on phenylephrine-induced contraction.

Arterial rings were pretreated in the absence or presence of 10 μM glibenclamide for 20 min, and then subjected to the cumulative addition of phenylephrine in the tissue bath. Data are means ± SEM of the tissues from 6 to 7 animals.

Figure 4. Effect of diazoxide on phenylephrine-induced Emax and pD2.

Arterial rings were pretreated in the absence or presence of 10 μM diazoxide for 20 min, and then subjected to the cumulative addition of phenylephrine in the tissue bath. The maximal response (Emax) and potency (pD2) values were determined from the phenylephrine concentration-response curve analyzed by computer-assisted nonlinear regression to fit the data using GraphPad Prism. P, pregnant; NP, nonpregnant. Data are expressed percentage of their own control and are means ± SEM of the tissues from 5 to 11 animals. *P < 0.05, control vs. diazoxide treated group.

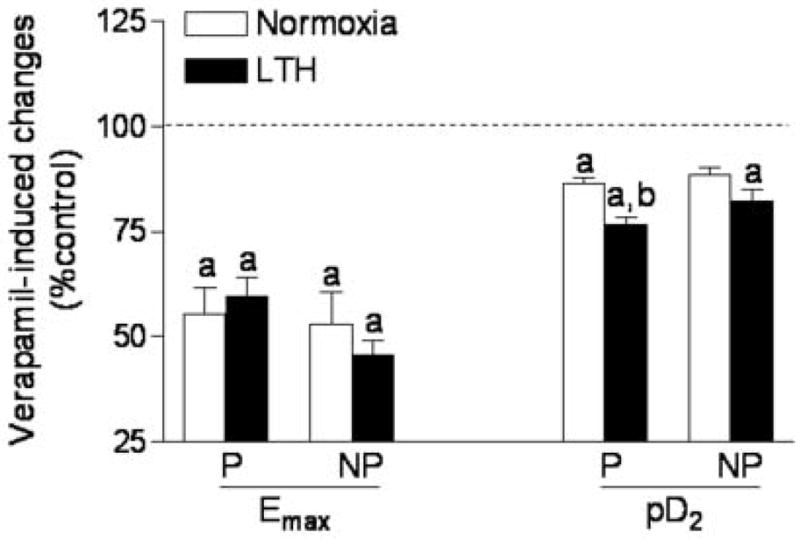

Role of L-type Ca2+ channel in α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contractions of uterine arteries

As shown in Figure 5, pretreatment with verapamil significantly inhibited the Emax of phenylephrine-induced concentration-response curves in both pregnant and nonpregnant uterine arteries from both normoxic and LTH animals. However, verapamil selectively inhibited the pD2 values in normoxic pregnant (pD2 value: 6.6 ± 0.1 vs. 5.9 ± 0.13, P < 0.05), LTH pregnant (pD2 value: 6.0 ± 0.1 vs. 4.7 ± 0.1, P < 0.05), and LTH nonpregnant (pD2 value: 5.7 ± 0.2 vs. 4.8 ± 0.1, P < 0.05), but not in normoxic nonpregnant (pD2 value: 6.0 ± 0.2 vs. 5.6 ± 0.3, P > 0.05) uterine arteries.

Figure 5. Effect of verapamil on phenylephrine-induced Emax and pD2.

Arterial rings were pretreated in the absence or presence of 10 μM verapamil for 20 min, and then subjected to the cumulative addition of phenylephrine in the tissue bath. Emax and pD2 values were determined from the phenylephrine concentration-response curve analyzed by computer-assisted nonlinear regression to fit the data using GraphPad Prism. P, pregnant; NP, nonpregnant. Data are expressed percentage of their own control and are means ± SEM of the tissues from 6 to 12 animals. aP < 0.05, control vs. verapamil; bP < 0.05, normoxia vs. LTH group.

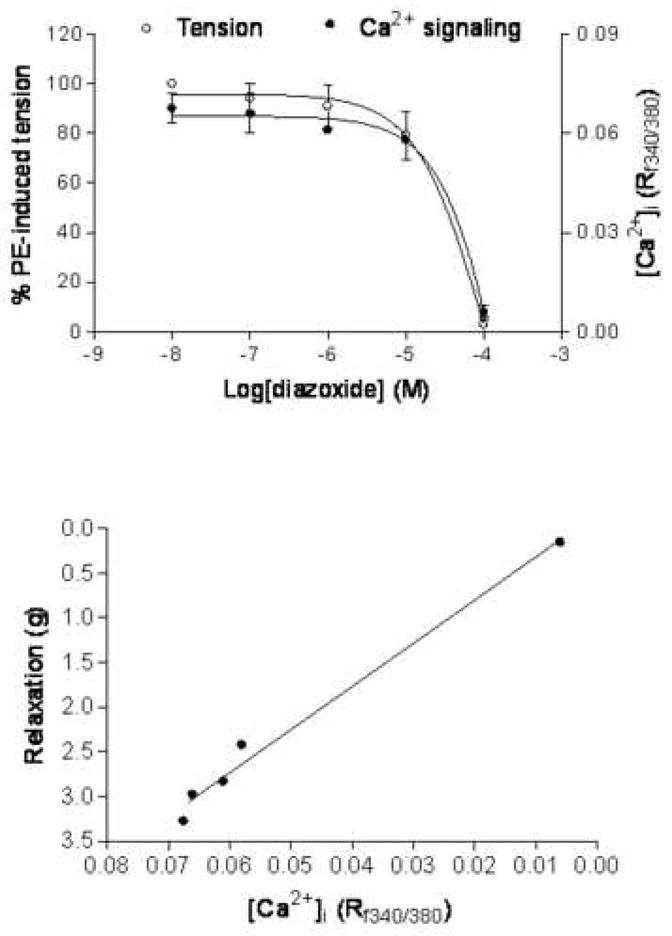

Relation of KATP-mediated relaxation and Ca2+ mobilization in pregnant uterine artery

Figure 6 shows the simultaneous measurement of intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) (Rf340/f380) and contractile tensions in response to diazoxide in the same phenylephrine-contracted pregnant uterine artery smooth muscle cells. As shown in Figure 6 (upper panel), diazoxide produced concentration dependent uterine vasorelaxation and decrease in Rf340/f380. The decreased Rf340/f380 was superimposed with the vasorelaxation. Figure 6 (lower panel) shows a positive correlation between vasorelaxation and [Ca2+]i decreased by cumulative additions of diazoxide in precontracted pregnant uterine arteries.

Figure 6. Diazoxide-induced reduction of [Ca2+]i and tension.

Smooth muscle [Ca2+]i and tension were measured simultaneously in the same tissue of normoxic pregnant uterine arterial rings loaded with fura 2. Upper panel: dose-response curves of the diazoxide-mediated reduction of [Ca2+]i (Rf340/380) and tension in the arterial rings precontracted with 10 μM of phenylephrine. Lower panel: Diazoxide-induced [Ca2+]i-tension relationships obtained with phenylephrine-precontracted arterial rings. Data are means ± SEM of the tissues from 4 animals.

Comment

The present study offers the following key observations: 1) although basal KATP channel activity may not play a great role in α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction in the uterine artery, KATP channel activation by diazoxide decreased uterine vascular tone by decreasing [Ca2+]i; 2) pregnancy enhanced KATP channel-mediated relaxation; 3) LTH decreased KATP channel activity and eliminated the pregnancy-mediated responses; 4) basal L-type Ca2+ channel activity plays a key role in regulating uterine vascular tone, and while this was not altered by pregnancy; 5) LTH enhanced the effect of L-type Ca2+ channel activity in α1-adrenoceptor mediated contractions of uterine artery in both pregnant and nonpregnant sheep.

It has been shown that KATP channel inhibition leads to vasoconstriction with increased vascular tone in vascular beds such as the coronary,17,18 mesenteric,19 and guinea pig uterine5 arteries both in vitro and in vivo. The present finding that glibenclamide had no significant effect on phenylphrine-induced contractions in ovine uterine arteries, is in agreement with previous studies that glibenclamide did not affect basal tone in the renal, cerebral and pulmonary arteries.20–24 It is likely that the role of KATP channels in the regulation of baseline vascular tone is tissues and/or animal species dependent. In the present studies, although the baseline vascular tone was not significantly affected by KATP channels, the KATP channel opener, diazoxide caused significant vasodilation and attenuated phenylphrine-induced contractions, suggesting a functional role of KATP channels in the ovine uterine artery. Similar studies have demonstrated that KATP channels are not involved in regulating basal tone in cerebral artery, but KATP channels play an important role in vasodilation caused by changes in metabolic state and by endogenous substances or synthetic KATP channel openers.3,25 Hypoxia, adenosine, and synthetic KATP channel openers have been shown to induce dilation in cerebral and pulmonary arteries.15,21 Taken together, our results support the idea that KATP channel activation is involved in uterine artery contractility. KATP channel activation plays a major role in modulating membrane potential, L-type Ca2+ channel activity, intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), and vascular tone.3 Simultaneous measurement of Rf340/f380 and contractile tensions in the same tissue of uterine artery smooth muscle shows the KATP channel opener, diazoxide, caused a positive relationship in decrements of Rf340/f380 and tension. This suggests that KATP channel activation leads to decreased vascular tone by decreasing [Ca2+]i.

In vascular smooth muscle cells, previous studies have demonstrated that KATP channel activation is closely regulated by several pathophysiological stimuli, and altered KATP channel function has been detected in various pathological conditions including hypertension, diabetes, and ischemia.2,26,27 In addition, the role of KATP channels also is dependent on physiologic and/or pathologic conditions. For example, in pulmonary arteries KATP channels are not involved in regulating basal tone in either normoxia or moderate hypoxia.24 However, KATP channels play an important role in pulmonary vasorelaxation in sustained and severe pulmonary hypoxia. In agreement with previous studies showing that pregnancy augments KATP channel activity in guinea pig uterine vascular bed,5 our current studies have shown that diazoxide-induced relaxations are significantly higher in pregnant than those in nonpregnant uterine arteries, and in pregnant but not nonpregnant uterine arteries, diazoxide pretreatment significantly inhibited the maximal responses of phenylephrine-induced contractions. These observations suggest that pregnancy up-regulates KATP channel activity, resulting in decreased uterine vascular resistance and reduced contractile efficacy of α1-adrenoceptor-mediated vasocontractile responses. This may contribute greatly to the increased uterine blood flow during normal pregnancy. In contrast to the potential effect of pregnancy on KATP channel activity in normoxic animals, the present studies indicated that LTH decreased diazoxide-induced relaxation in pregnant uterine arteries and eliminated pregnancy-mediated responses. Recently, we have shown that LTH increases uterine vascular tone during pregnancy.10 Thus, the present observations suggest that LTH-mediated enhanced uterine vascular tone may be attributed, in part, to a decrease in KATP channel activity. The inhibited patterns of pD2 value by diazoxide in phenylephrine-induced contractions were not affected by pregnancy and LTH, suggesting that pregnancy and LTH-mediated changes of α1-adrenoceptor-mediated sensitivity (pD2 value) of contractions may not be associated with this altered KATP channel activity.

In contrast to the potential effect of pregnancy on KATP channel activity, verapamil-induced relaxations of uterine arteries were not significant different between nonpregnant and pregnant animals. This suggests that L-type Ca2+ channel activity is not regulated by pregnancy, and is supported by previous studies showing KCl-induced uterine artery contractions are similar in nonpregnant and pregnant animals.12 We also examined the effect of L-type Ca2+ channel inhibition on α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction. Phenylephrine-induced Emax values of uterine artery smooth muscle cells were significantly inhibited by verapamil, suggesting an important role of L-type Ca2+ channel in the regulation of α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction. The finding that inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channel activity by verapamil significantly attenuated phenylephrine-induced pD2 values of uterine arteries in pregnant, but not in nonpregnant, animals, suggests enhanced coupling of L-type Ca2+ channel activity to α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction of uterine artery during pregnancy.

L-type Ca2+ channel regulation by O2 tension is a physiologically important and widespread phenomenon.28 In agreement with previous reports that hypoxia up-regulated L-type Ca2+ channel activity,29–31 our findings that verapamil-induced relaxations of uterine arteries were significantly enhanced in LTH nonpregnant, but not pregnant, animals compared to normoxic controls, suggest that LTH may up-regulate basal L-type Ca2+ channel activity in uterine arteries. Consistent with the effect of LTH on basal L-type Ca2+ channel activity, our findings that in both nonpregnant and pregnant uterine arteries, the inhibited patterns by verapamil in phenylephrine-induced contractions were enhanced by LTH, suggest that LTH altered the coupling of L-type Ca2+ channel to α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction. These results present a novel regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel activity under hypoxic conditions.

Although the present studies have demonstrated that pregnancy and LTH differentially regulate uterine artery KATP channel and L-type Ca2+ channel activities, the underlying mechanisms are not understood. Previous studies have demonstrated that KATP channels and L-type Ca2+ channels activities are regulated through a number of endogenous vasodilators and vasocontrictors,2,3,19 an important enzyme in this regard being protein kinase C (PKC). In vascular smooth muscle, several vasoconstricting hormones and neurotransmitters inhibit KATP channels function via PKC activation.2,32,33 Given the fact that uterine artery PKC activity is significantly attenuated by pregnancy34–36 and enhanced by chronic hypoxia,10 the pregnancy-mediated increase and LTH-mediated a decrease in KATP channel activity may be regulated through the alteration of PKC signaling system. Thus, it provides a new direction for us to study the role of PKC in regulation of KATP channel activity in our future studies. In addition, we will further explore whether pregnancy and chronic hypoxia directly regulate KATP channel gene expression which may contribute to the altered KATP channel activity in uterine vasculatures.

In conclusion, both KATP and L-type Ca2+ channels play key roles in the regulation of uterine artery contractility. Pregnancy selectively increases KATP channel activity, but has no significant effect on the L-type Ca2+ channel activity per se. This increased KATP channel activity is likely to contribute to the decreased uterine artery resistance and the increased uterine blood flow in pregnancy. High altitude long-term hypoxia decreases the KATP channel activity but increases the L-type Ca2+ channel activity, which may provide a underlying mechanism for the enhanced myogenic tone observed in uterine arteries of pregnant sheep acclimatized to high altitude long-term hypoxia. The potential role of the sex steroid hormones and other factors in regulating the channel activities in the adaptation of uterine artery contractility to pregnancy and chronic hypoxia remains to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support: This work was supported in part by NIH grants HD31226, HL89012 and by the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program Award 18KT-0024.

Acknowledgment

N/A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jackson WF. Potassium channels in the peripheral microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2005;12:13–127. doi: 10.1080/10739680590896072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko EA, Han J, Jung ID, Park WS. Physiological roles of K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2008;44:65–81. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.44.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenfeld CR, Cornfield DN, Roy T. Ca(2+)-activated K(+) channels modulate basal and E(2)beta-induced rises in uterine blood flow in ovine pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H422–H431. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keyes L, Rodman DM, Curran-Everett D, Morris K, Moore LG. Effect of K+ATP channel inhibition on total and regional vascular resistance in guinea pig pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H680–688. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadorette C, Sicotte B, Brochu M, St-Louis J. Effects of potassium channel modulators on myotropic responses of aortic rings of pregnant rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H567–H576. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer MC, Brayden JE, Mclaughlin MK. Characteristerics of vascular smooth muscle in the maternal resistance circulation during pregnancy in the rat. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1510–1516. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90427-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giussani DA, Phillips PS, Anstee S, Barker DJ. Effects of altitude versus economic status on birth weight and body shape at birth. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:490–494. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore LG, Hershey DW, Jahnigen D, Bowes W., Jr The incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension is increased among Colorado residents at high altitude. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:423–429. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang K, Xiao D, Huang X, Longo LD, Zhang L. Chronic hypoxia increases pressure-dependent myogenic tone of the uterine artery in pregnant sheep: role of ERK/PKC pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1840–1849. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00090.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao D, Bird IM, Magness RR, Longo LD, Zhang L. Upregulation of eNOS in pregnant ovine uterine arteries by chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiolo. 2001;280:H812–820. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao D, Zhang L. Calcium homeostasis and contractions of the uterine artery: Effect of pregnancy and chronic hypoxia. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1171–1177. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall JM, Thomas T, Turner L. A link between adenosine, ATP-sensitive K+ channels, potassium and muscle vasodilatation in the rat in systemic hypoxia. J Physiol. 1993;472:1–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quayle JM, Turner MR, Burrell HE, Kamishima T. Effects of hypoxia, anoxia, and metabolic inhibitors on KATP channels in rat femoral artery myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H71–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01107.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taguchi H, Heistad DD, Kitazono T, Faraci FM. ATP-sensitive K+ channels mediate dilatation of cerebral arterioles during hypoxia. Circ Res. 1994;74:1005–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao D, Zhang L. Adaptation of uterine artery thick- and thin- filament regulatory pathway to pregnancy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H142–H148. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00655.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imamura Y, Tomoike H, Narishige T, Takahashi T, Kasuya H. Glibenclamide decreases basal coronary blood flow in anesthetized dogs. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H3993–H404. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samaha FF, Heineman FW, Ince C, Fleming J, Balaban RS. ATP-sensitive potassium channel is essential to maintain basal coronary vascular tone in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C1220–1227. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C3–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brayden JE. Hyperpolarization and relaxation of resistance arteries in response to adenosine diphosphate, Distribution and mechanism of action. Circ Res. 1991;69:1415–1420. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the basilar artery. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H8–H13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.1.H8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long W, Zhang L, Longo LD. Fetal and adult cerebral artery K(ATP) and K(Ca) channel responses to long-term hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1692–16701. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01110.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Standen NB, Quayle JM, Davies NW, Brayden JE, Huang Y, Nelson MT. Hyperpolarizing vasodilators activate ATP-sensitive K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle. Science. 1989;245:177–180. doi: 10.1126/science.2501869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiener CM, Dunn A, Sylvester JT. ATP-dependent K+ channels modulate vasoconstrictor responses to severe hypoxia in isolated ferret lungs. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:500–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI115331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quayle JM, Standen NB. KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:797–804. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bari F, Louis TM, Meng W, Busijia DW. Global Ischemia impairs ATP-sensitive K+ channel function in cerebral arterioles in piglets. Stroke. 1996;27:1872–1889. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh M, Hanna ST, Wang R, McNeill JR. Altered vascular reactivity and KATP channel currents in vascular smooth muscle cells from deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:525–531. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Barneo J, Pardal R, Ortega-Saenz P. Cellular mechanism of oxygen sensing. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:259–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scragg JL, Fearon IM, Boyle JP, Ball SG, Varadi G, Peers C. Alzheimer’s amyloid peptides mediate hypoxic up-regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels. FASEB J. 2005;19:150–152. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2659fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soukhova-O’Hare GK, Ortines RV, Gu Y, Nozdrachev AD, Prabhu SD, Gozal D. Postnatal intermittent hypoxia and developmental programming of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats: the role of reactive oxygen species and L-Ca2+ channels. Hypertension. 2008;52:156–162. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summers BA, Overholt JL, Prabhakar NR. Augmentation of L-type calcium current by hypoxia in rabbit carotid body glomus cells: evidence for a PKC-sensitive pathway. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1636–1644. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park WS, Ko EA, Han J, Kim N, Earm YE. Endothelin-1 acts via protein kinase C to block KATP channels in rabbit coronary and pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;45:99–108. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000150442.49051.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Y, Cui N, Shi W, Jiang C. A short motif in Kir6.1 consisting of four phosphorylation repeats underlies the vascular KATP channel inhibition by protein kinase C. J Bio Chem. 2008;283:2488–2494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708769200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanashiro CA, Cockrell KL, Alexander BT, Granger JP, Khalil RA. Prenancy-associated reduction in vascular protein kinase C activity rebounds during inhibition of NO synthesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R295–R303. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magness RR, Rosenfeld CR, Carr BR. Protein kinase C in uterine and systemic arteries during ovarian cycle and pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:E464–470. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.3.E464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao D, Zhang L. ERK MAP kinases regulate smooth muscle contraction in ovine uterine artery: effect of pregnancy. Am J Physiolo Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H292–300. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]