Abstract

This research was conducted to examine the growth profile, growth kinetics, and insulin-secretory responsiveness of BRIN-BD11 cells grown in optimized medium on different types of microcarriers (MCs). Comparisons were made on modified polystyrene (Hillex® II) and crosslinked polystyrene Plastic Plus (PP) from Solohill Engineering. The cell line producing insulin was cultured in a 25 cm2 T-flask as control while MCs based culture was implemented in a stirred tank bioreactor with 1 L working volume. For each culture type, the viable cell number, glucose, lactate, glutamate, and insulin concentrations were measured and compared. Maximum viable cell number was obtained at 1.47 × 105 cell/mL for PP microcarrier (PPMCs) culture, 1.35 × 105 cell/mL Hillex® II (HIIMCs) culture and 0.95 × 105 cell/mL for T-flask culture, respectively. The highest insulin concentration has been produced in PPMCs culture (5.31 mg/L) compared to HIIMCs culture (2.01 mg/L) and T-flask culture (1.99 mg/L). Therefore overall observation suggested that PPMCs was likely preferred to be used for BRIN-BD11 cell culture as compared with Hillex® II MCs.

Keywords: Insulin, BRIN-BD11, Solohill, Microcarrier, Bioreactor

Introduction

The BRIN-BD11 cell line is a clonal glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cell line which is responsive to a range of pharmacological modulators of insulin secretion (Ball et al. 2000; McClenaghan and Flatt 1999a, b). In a recent study, it was demonstrated that BRIN-BD11 cells display insulin secretory responses to a wide range of secretogogues, including glucose, amino acids, hormones, neurotransmitters, sulfonylureas, and other insulinotropic drugs (Brennan et al. 2002).

During the past 20 years considerable effort has been devoted to the production of transplantable and inheritable insulinomas and insulin-secreting cell lines by means of study on rat pancreatic islets which has been helpful in learning the mechanisms involved in human islet transplantation (Amoli et al. 2005). Generally, most of these studies are initiated by the motivation of generating large quantities of functional beta cells for basic studies on the mechanisms of insulin secretion (McClenaghan and Flatt 1999a, b). The main problem encountered while scaling up the bulk production of functional pancreatic islet cell line consists in its anchorage-dependent property requiring microcarriers for supporting cell growth.

However, the MCs technique which was first introduced by van Wezel in 1976 has made it possible to grow anchorage-dependent cell lines in suspension culture. In MCs cell culture technology, anchorage-dependent animal cells are grown on the surface of small spheres which are maintained in stirred suspension culture (Grinnell et al. 1977; Groot 1995). MCs particles have been extensively used for amplifying various types of adherent cells which include the expansion of cells for large-scale production of growth factors, vaccines and antibodies (Phillips et al. 2008; Bluml 2007). In this research, the growth profile, growth kinetics, and insulin production of BRIN-BD11 cells cultured on HIIMCs and PPMCs were described. Comparisons have been made on the overall performance of these two MCs.

Materials and methods

Materials and medium preparation

BRIN-BD11 as an insulin-secreting cell line was used in this study. It had been obtained from Dr. Muhajir Hamid, Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry, University Putra Malaysia. RPMI-1640 tissue culture medium (without l-glutamine), fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics (100 U/mL) penicillin, 0.1 g/L streptomycin) were purchased from Gibco (USA). Trypsin, HEPES, sodium pyruvate, and l-glutamine (powder) were bought from Sigma–Aldrich (UK). Glucose and all other chemicals and reagents were obtained from BDH Chemicals Ltd while Hillex® and Plastic Plus MCs were purchased from SoloHill Engineering (USA).

BRIN-BD11 cell culture in T-flask

Aliquots of BRIN-BD11 cell (1 mL) was seeded at an initial concentration of 0.5 × 105 cell mL−1 into six 25 cm2 T-flasks containing 9 mL of culture medium which had been prepared according to the optimized formulation containing 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (v/v) antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin), and 11.1 mM glucose. Cells were cultured in sterile vented tissue culture flasks (Corning Glass Works, Corning, NY) and were incubated at 37 °C in an RS Biotech incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. 1 mL of the culture medium withdrawn from one flask at every 8 h interval was transferred into an Eppendorf tube and was centrifuged at 900 rpm for 5 min. Supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C for subsequent determination of glucose, lactate, glutamate, and insulin concentration. The remaining contents of culture medium including the monolayer BRIN-BD11 cells were then treated with 1 mL of trypsin and incubated for 5 min for cell counting as described by Butler (2004) while the remaining volume in the flasks was cryopreserved at −80 °C. These procedures were repeated for successive 48 h.

Kinetic study

Calculation of specific growth rate (μ) using the formula of Scheirer and Merten (1991) were used:

|

1 |

where X represents the viable cell density per mL, t the time points of sampling expressed in hours; n and n − 1 stand for two succeeding sampling points.

Doubling time (td) is given by the formula:

|

2 |

Yield coefficient (YP/S) was calculated by formula

|

3 |

where P represent insulin product per g, and S is glucose substrate per g.

Preparation of microcarrier culture

To prepare HIIMCs (H112-170) and PPMCs (PP102-915), manufacturer’s guide was followed. Dry MCs used at 14 and 20 g/L, respectively were suspended in deionised water and autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min. Autoclaved MCs were equilibrated by suspending them in 100 mL culture medium for 1 h in a 5% CO2 incubator prior to use.

Bioreactor operation

The implementation of MCs based culture was conducted in a two liters stirred tank Biostat® B–DCU bioreactor (B. Braun Biotech International, Germany) with one liter working volume as described by Rourou et al. (2007). The pH probe was calibrated before autoclaving the bioreactor in a vertical autoclave unit (Hirayama, Japan). Eight hundred millilitre of culture medium prepared according to the optimized formulation excluding phenol red and 100 mL prepared MCs suspension were filled into the vessel and brought to actual operating conditions before inoculation of the cells in the bioreactor by calibrating the pO2 probe and setting the operating temperature. Dissolved oxygen value was regulated by importing air mixture with different ratios of O2, N2, CO2 and air. The culture pH was controlled by the addition of NaOH and HCl and the bioreactor was inoculated with 0.5 × 105 viable cell/mL of inoculum (100 mL). Antifoam solution (Shin-Etsu Chemical, Japan) was used to avoid foaming problem in the vessel. The culture condition was 37 °C, initial pH 7.2, 0.1 vvm of aeration, and agitation was carried out at 70 rpm with marine type of impeller while the pO2 was adjusted to 40%. These controlled parameters were monitored and recorded on-line throughout the experiment.

Sampling of microcarrier culture

Ten millilitre sample containing MCs was collected for every 8 h and MCs were allowed to settle. The supernatant was carefully removed into another 15 mL centrifuge tube. Ten millimetre trypsin was added into the tube containing MCs and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Viable cell number was counted following the same cell counting procedure implemented for T-flask culture. Another tube which contained the supernatant was then centrifuged at 4 °C, 1,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C for subsequent determination of glucose, lactate, glutamate, and insulin concentration. For physical observation, a small amount of MCs were removed to observe the cell attachment using field emission scanning electron micrograph FESEM (Philip).

Glucose, lactate and glutamate analysis

For substrate and product analysis, YSI 2700 S single channel biochemistry analyzer with YSI 2710 turntable (YSI Inc, USA) were used to measure glucose, lactate, and glutamate in the growth media. Membrane YSI 2365, membrane YSI 2754, and membrane YSI 2329 were used for measurement of glucose, glutamate, and lactate, respectively. Standard calibration YSI 2776 was used for glucose and lactate while YSI 2755 was used for glutamate during the measurement. YSI 2357 was the system buffer used for all measurements. One mililitre supernatant was transferred into Eppendorf tube fitting on the sample wheel and sample was automatically measured by the sensor probe.

Insulin quantification

Reversed-phase HPLC technique was used to determine the insulin concentration. The components involved were HPLC system (Waters 2847 Alliance Milford, MA, USA) which consists of degasser, injector pumps, and UV detector; 5 μL syringe; and silica-based analytical column (Jupiter 5u C4 300A, 250 × 4.6 mm, particle size 5.32 μm) from Phenomenex (USA). The HPLC was connected to UV detector which UV wavelength was set at 214 nm. The analytical column and the gradient solvent system of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water as solvent A and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water (90:10) as solvent B were used to analyze the insulin concentration in each sample. The solvents were filtered to remove unwanted particles prior to use. The column was equilibrated for 30 min to zero the baseline. Five microlitre of the sample was injected and loaded into the HPLC with flow rate of 1 mL/min. The sample was run for 20 min and the resulting chromatographic separation was monitored and recorded.

Results

Growth profile and kinetic

Two types of commercial MCs selected for our purpose were HIIMCs and PPMCs. Figure 1 shows the growth profile of BRIN-BD11 cells on both types of MC. BRIN BD-11 cells were found to attach to the MC beads within the first 8 h after inoculation of cells in the bioreactor containing optimised culture medium and continued to proliferate for the following 48 h. The maximum concentration of 1.47 × 105 viable cell/mL was achieved with PPMCs and 1.35 × 105 viable cell/mL using HIIMCs as compared to conventional monolayer culture in T-flask which only gave 0.95 × 105 viable cell/mL after 48 h incubation. However, growth pattern of BRIN-BD11 on HIIMCs and PPMCs were almost similar in contrast to lower performance of cell growth in T-flask cultures as shown in Fig. 1. It was observed that cells reached confluence of about 80–90% after 48 h of incubation. However, in terms of growth kinetic aspects (Table 1) better results were obtained by BRIN-BD11 cells on HIIMCs which had a specific growth rate, μ and a doubling time, td of 0.52 day−1 and 1.3 day, respectively. This is followed by PPMCs with a μ of 0.49 day−1 and td of 1.4 day. Figure 2 shows the attachment of BRIN-BD11 cell on HIIMCs surface after 8 h of incubation and the cell still maintained its round shape at the beginning of adherence to MC surface.

Fig. 1.

Growth profiles of BRIN-BD11 in T-flask and on both microcarriers

Table 1.

Growth kinetics for different microcarrier cultures

| Specific growth rate, μ (day−1) | Doubling time, td (day) | Observed yield coefficient, YP/S (g/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-flask (as control) | 0.28 | 2.5 | 2.38 × 10−6 |

| Hillex® II microcarrier | 0.52 | 1.3 | 2.94 × 10−6 |

| Plastic plus microcarrier | 0.49 | 1.4 | 4.14 × 10−6 |

Fig. 2.

Cell attachment of BRIN-BD11 cells on Hillex® II microcarrier at first 8 h

Substrate consumption and by product

Figure 3a–c shows the concentration of glucose, lactate, and glutamate in BRIN-BD11 culture media for T-flask and MC cultures. Glucose, a macronutrient added as substrate for cell metabolism decreased over time from an initial concentration of 3.7 g/L while lactate and glutamate, among the major by-products released due to cell metabolic activity were found to increase with time. Glutamate was found to be at lower concentration in all culture conditions (T-flask and MC culture) as compared to lactate. Glucose uptake was similar for all conditions and the final concentration at 50 h was between 2.5–3.0 g/L.

Fig. 3.

Glucose, lactate, and glutamate rate in BRIN-BD11 culture for 48 h showing decreasing concentrations of glucose and increasing concentrations for both lactate and glutamate. (a) T-flask culture (b) Hillex® II microcarrier culture (c) Plastic Plus microcarrier culture

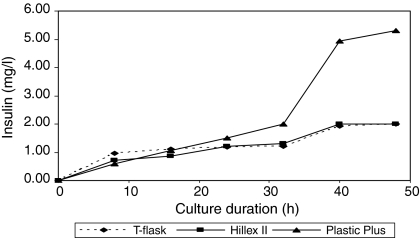

Insulin secretion

The comparison of insulin production between T-flask and MCs culture is shown by Fig. 4. Insulin concentration increased with time and viable cell number for both types of MC. However, insulin productivity increased rapidly after 30 h culture for PPMCs while HIIMCs and T-flask produced comparable amounts of insulin product. PPMCs outperformed T-flask and HIIMCs after 15 h culture in terms of insulin productivity where it produced 5.31 mg/L of insulin while HIIMCs and T-flask cultures produced 2.01 and 1.99 mg/L, respectively. The observed yield coefficient of PPMCs was calculated as 4.14 × 10−6 (g/g) while for HIIMCs and T-flask culture it was calculated as 2.94 × 10−6 (g/g) and 2.38 × 10−6 (g/g) (Table 1). This is relatively low because only several milligrams of insulin are produced for every one gram of glucose consumed.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of insulin secretion in culture media between T-flask and both microcarriers. After 15-h culture duration, Plastic Plus microcarrier starts to outperform Hillex® II microcarrier and T-flask cultures

Discussion

The highest viable cell number is achieved by using PPMCs due to the diameter of the MC beads which is smaller (125–212 microns) than that of HIIMCs (160–180 microns). A smaller diameter of an MC bead provides larger surface area in the culture allowing optimal cell growth (Varani et al. 1996; Markvicheva and Grandfils 2004). Comparing this to the limited surface area in T-flask, this suggests that high surface area provided by MCs allow better cell growth and proliferation as evident from the viable cell number in this study. Particle size also determines the requirement for a good exchange of nutrients and oxygen. However, the nature of the surface on which cells are cultured plays also an important role in their ability to attach, proliferate, migrate and function (Cooke et al. 2008).

Interestingly, it was observed that BRIN-BD11 on PPMCs were more insulin productive compared to modified polystyrene (HIIMCs) or T-flask. This is in contrast to the growth kinetics of the cells where HIIMCs showed high specific growth rate compared to PPMCs. High concentration of PPMCs (20 g/L) may have led to increased stress emanating from collisions between beads (Mendonca and Pereira 1998; Julien 2003). This stress may eventually cause cell death through apoptosis or reduce the ability of cells to attach. Surface charge of MCs was also reported to have an effect to cell attachment and proliferation (Smetana 1999). Although both MCs carried cationic surface charge, the introduction of cationic trimethyl ammonium on polystyrene core substrate surface can contribute to the low production of insulin compared to crosslinked polystyrene with an electrical charge incorporated in the beads (Solo Hill Engineering Inc 2007).

Furthermore, the recovery of trypsin-released cells from the polystyrene PPMCs was more difficult and complicated since lower specific gravity of PPMCs (1.02) compared to HIIMCs (1.11) made sedimentation of PPMCs fail to adequately separate the cell polystyrene mixtures (White and Ades 1990). Poor recovery of cells from the polystyrene may partially account for the reduced cell counts reported here. The resulting doubling time was found to be in agreement with many theories stating that doubling time for animal cells is higher than 24 h (Freshney 2006). In HIIMCs cultures, the cell growth was higher and the cells doubled their number in a shorter time when compared to the PPMCs. Hu and Wang (2004) reported that the kinetics of mammalian cell growth in a MC culture is affected by the distribution of cells on MCs. In addition, faster cell growth rate observed in HIIMCs is attributed to its surface charge that supports easy attachment of cells and easy detachment with trypsin (Varani et al. 1998).

Newsholme et al. (2007) reported that the major physiological regulator in insulin production is glucose. Based on the results in Fig. 3a–c, although glucose uptake rate was almost similar for all cultures, lactate concentration in T-flasks was doubled to that observed in MCs culture. Lactate is assumed to both inhibit and kill the cells (Batt and Kompala 1989) which might explain the low cell number and insulin production. In addition, BRIN-BD11 β-cells in vitro were reported to consume glutamine at high rates (Dixon et al. 2003). The presence of glutamate concentration proved the consumption of glutamine in BRIN-BD11 cells in T-flask and MC cultures. Newsholme et al. (2007) reported in their study that although glutamine was rapidly taken up and metabolized by the cells, it alone did not stimulate insulin secretion or enhanced glucose-induced insulin secretion. This observation is supported by the study done by Zahid et al. (2008) and Newsholme et al. (2007) that combination of D-glucose and l-glutamine promote good cell growth and insulin secretion of BRIN-BD11 cells as a step towards mass propagation of insulin production.

High toxic by-products such as lactate and glutamate released by the culture metabolic activities have detrimental effects for the cells at acidic pH (Altamirano et al. 2006). Lower amount of lactate and glutamate observed from MC cultures (in bioreactor) corresponds to the ability of the bioreactor to automatically control the pH via fed-back controller system as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

On-line controlled parameters monitoring for Hillex® II microcarrier experiment

McClenaghan (2007) reported that there were many factors including nutrients and biological molecules that may regulate the complex mechanism of insulin secretion. Therefore, the chemical composition of MC might also have effects on insulin secretion as evident from the study. To this end, selection of optimal MC may have an effect in view of achieving higher insulin production from mammalian cell culture.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) Research Centre under Project Number LT 28/IIUM. Thank you for all contributors for this project especially for the staff of Laboratory of Cell and Tissue Engineering, Biotechnology Engineering Department of IIUM.

References

- Altamirano C, Illanes A, Becerra S, Cairo JJ, Godia F. Considerations on the lactate consumption by CHO cells in the presence of galactose. J Biotech. 2006;125:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoli MM, Moosavizadeh R, Larijani B. Optimizing conditions for rat pancreatic islets isolation. Cytotechnology. 2005;48:75–78. doi: 10.1007/s10616-005-3586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball AJ, Flatt PR, McClenaghan NH. Stimulation of insulin secretion in clonal BRIN-BD11 cells by the imidazoline derivatives KU14r and RX801080. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42:575–579. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batt BC, Kompala DS. A structured kinetic modeling framework for the dynamics of hybridoma growth and monoclonal antibody production in continuous suspension cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1989;34:515–531. doi: 10.1002/bit.260340412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluml G. Microcarrier cell culture technology. In: Portner R, editor. Animal cell biotechnology: methods and protocols. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2007. pp. 149–179. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan L, Shine A, Hewage C, Malthouse JPG, Brindle KM, McClenaghan NH, Flatt PR, Newsholme P. A NMR based demonstration of substantial oxidative l-alanine metabolism and l-alanine enhanced glucose metabolism in a clonal pancreatic β cell line—metabolism of l-alanine is important to the regulation of insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51:1714–1721. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. Animal cell culture technology. London: BIOS Scientific Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. Animal cell cultures: recent achievements and perspectives in the production of biopharmaceuticals. App Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;68:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1980-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke MJ, Phillips SR, Shah DSH, Athey D, Lakey JH, Przyborski SA. Enhanced cell attachment using a novel cell culture surface presenting functional domains from extracellular matrix proteins. Cytotechnology. 2008;56:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s10616-007-9119-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon G, Nolan J, McClenaghan N, Flatt PR, Newsholme P. A comparative study of amino acid consumption by rat islet cells and the clonal beta-cell line BRIN-BD11—the functional significance of l-alanine. J Endocrinol. 2003;179:447–454. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1790447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finbarr PM, OHarte FPM, Hunter K, Gault VA, Irwin N, Green BD, Greer B, Harriott P, Bailey CJ, Flatt PR. Antagonistic effects of two novel GIP analogs, (Hyp3)GIP and (Hyp3)GIPLys16PAL, on the biological actions of GIP and longer-term effects in diabetic ob/ob mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1674–E1682. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00391.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freshney RI. Basic principles of cell culture. In: Novakovic GV, Freshney RI, editors. Culture of cells for tissue engineering. Scotland: Wiley; 2006. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F, Hays DG, Minter D. Cell adhesion and spreading factor partial purification and properties. Exp Cell Res. 1977;110:175–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot M. Microcarrier technology, present status and perspective. Cytotechnology. 1995;18:51–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00744319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WS, Wang DIC. Selection of microcarrier diameter for the cultivation of mammalian cells on microcarriers. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;30:548–557. doi: 10.1002/bit.260300412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien J. Hydrodynamics, mass transfer and rheological studies of Gibberellic acid production in a stirred tank Bioreactor. World J Microb Biot. 2003;23:615–662. [Google Scholar]

- Markvicheva E, Grandfils C. Microcarriers for animal cell culture. In: Nedovic VA, editor. Fundamentals of cell immobilisation biotechnology. The Netherlands: Kluwer; 2004. pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- McClenaghan NH. Physiological regulation of the pancreatic β-cell: functional insights for understanding and therapy of diabetes. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:481–496. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.034835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClenaghan NH, Flatt PR. Engineering cultured insulin-secreting pancreatic B-cell lines. J Mol Med. 1999;77:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s001090050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClenaghan NH, Flatt PR (1999b) Physiological and pharmacological regulation of insulin release: insights offered through exploitation of insulin-secreting cell lines. Diabetes Obes Metab 1: 1–14. PMID: 11220292 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mendonca RZ, Pereira CA. Cell metabolism and medium perfusion in Vero cell cultures on microcarriers in a bioreactor. Bioprocess Eng. 1998;18:213–228. doi: 10.1007/s004490050433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonca RZ, Arrozio SJ, Antoniazzi MM, Ferreira JMC, Jr, Pereira CA. Metabolic active-high density VERO cell cultures on microcarriers following apoptosis prevention by galactose/glutamine feeding. J Biotechnol. 2002;97:13–22. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(02)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme P, Bender K, Kiely A, Brennan L. Amino acid metabolism, insulin secretion and diabetes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1180–1186. doi: 10.1042/BST0351180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips BW, Horne R, Lay TS, Rust WL, Teck TT, Crook JM. Attachment and growth of human embryonic stem cells on microcarriers. J Biotechnol. 2008;138:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.07.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rourou S, Ark A, Velden T, Kallel H. A microcarrier cell culture process for propagating rabies virus in Vero cells grown in a stirred bioreactor under fully animal component free conditions. Vaccine. 2007;25:3879–3889. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer W, Merten OW. Instrumentation of animal cell culture reactors. In: Ho CS, Wang DIC, editors. Animal cell bioreactors. Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston; 1991. pp. 405–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana K. Cell biology of hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1999;14:1046–1050. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(93)90203-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solo Hill microcarrier beads. Michigan: Solohill Engineering Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel AL (1976) Growth of cell-strains and primary cells on micro-carriers in homogeneous culture. Nature 216:64–65 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Varani J, Josephs S, Hillegas W. Human diploid fibroblast growth on polystyrene microcarriers in aggregates. Cytotechnology. 1996;22:111–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00353930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani J, Piel F, Josephs S, Beals TF, Hillegas WJ. Attachment and growth of anchorage-dependent cells on a novel, charged-surface microcarrier under serum-free conditions. Cytotechnology. 1998;28:101–109. doi: 10.1023/A:1008029715765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LA, Ades EW (1990) Growth of Vero E-6 cells on microcarriers in a cell bioreactor. J Clin Microbiol 28: 283–286. PMCID: PMC269591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zahid MZA, Yusof F, Karim MIA. Effect of d-glucose and l-glutamine in BRIN-BD11 insulinoma cell culture growth and insulin production. 4th Kuala Lumpur Int Conf Biomed Eng. 2008;21:810–813. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69139-6_201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]