Abstract

Pyrazole, a neutral nitrogen ligand and an isomer of imidazole, has been used as a fifth ligand to prepare two new species, [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] (Hdmpz = 3,5-dimethylpyrazole), the first structurally characterized examples of five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates with a nonimidazole neutral ligand. Both complexes are characterized by X-ray crystallography, and structures show common features for five-coordinate iron(II) species, such as an expanded porphinato core, large equatorial Fe–Np bond distances and a significant out-of-plane displacement of the iron(II) atom. The Fe–N(pyrazole) and Fe–Np bond distances are similar to those in imidazole-ligated species. These suggest that the coordination abilities to iron(II) for imidazole and pyrazole are very similar even though pyrazole is less basic than imidazole. Mössbauer studies reveal that [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] has the same behavior as those of imidazole-ligated species, such as negative quadrupole splitting values and relative large asymmetry parameters. Both the structures and Mössbauer spectra suggest pyrazole-ligated five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates have the same electronic configuration as imidazole-ligated species.

Introduction

Five-coordinate high-spin iron(II) porphyrinates have been of interest as models of deoxyhemoglobin and deoxymyoglobin. In addition, high-spin five-coordinate states are also found in many other heme proteins, such as reduced cytochrome P450, chloroperoxidase, and horseradish peroxidase. Knowledge of both the electronic and geometric structure at iron appears to be the key to understanding the diverse and complicated functions of these hemoproteins. Indeed, the electronic ground states of models of these iron(II) species have been intensively investigated both experimentally and theoretically and yet are far from being known with certainty.

The difficulty in understanding the electronic structure of the five-coordinate high-spin hemes is reflected in both the relatively large amount published on the issue and some inconsistent interpretations for both experimental and theoretical studies.1–9 A number of recent density functional theory (DFT) studies for five-coordinate imidazole-ligated hemes have appeared.1–4 However, the conclusions reached about the electronic ground state are by no means uniform. Three of the four DFT calculations found that a triplet state was lower in energy than the experimentally observed quintet state. In all of these cases, a quintet state is predicted to be lowest in energy when the iron(II) atom is constrained to be further out of the porphyrin plane than the value obtained for the triplet state. In other words, DFT calculations suggest that large values of the displacement of Fe from the porphyrin plane stabilize higher spin multiplicities. The fourth study3 does predict a quintet ground state.

As part of a more general program of characterization of high-spin iron(II) porphyrinates, our previous studies10–13 show that there are two kinds of ligands on five-coordinate high-spin iron(II) porphyrinates: i) neutral ligands, such as imidazole and ii) anionic ligands, such as imidazolate, thiolate, halogenate, phenolate, alkoxide, acetate etc.10,14–17 Even though all have a high-spin state (S=2), there are significant differences in their molecular structures and Mössbauer data. The electronic structure implied by the Mössbauer results shows that all of these deoxymyoglobin models are distinctly different from those of high-spin iron(II) porphyrinates ligated by anionic ligands. For the anionic ligand coordinated species, the ground state has dxy as the doubly occupied orbital, whereas for the imidazole-ligated species the doubly occupied orbitals can best be described as a low-symmetry hybrid orbital comprised of a linear combination of the two axial dπ orbitals, along with a significant dxy contribution.

Surprisingly, although there are a large variety of anionic ligands that yield high-spin five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates, imidazoles are the only neutral ligand that has yielded this state. We are interested in the influence of axial ligands on the electronic configuration and structure of high-spin iron(II) porphyrinates. What is the electronic configuration for the five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates with other exogenous neutral ligands besides imidazole? Herein, pyrazole, an isomer of imidazole, has been studied as the fifth ligand. Two high-spin five-coordinate pyrazole-ligated iron(II) porphyrinates, [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)],18 have been synthesized. We report the molecular structures and further examine the electronic configuration of these complexes.

Experimental Section

General Information

All reactions and manipulations for the preparation of the iron(II) porphyrin derivatives (see below) were carried out under argon using a double-manifold vacuum line, Schlenkware, and cannula techniques. Toluene and hexanes were distilled over sodium benzophenone ketyl. Ethanethiol and 3,5-dimethylpyrazole was used as received. The free-base porphyrin H2Por (Por = TPP or Tp-OCH3PP) was prepared according to Adler et al.19 The metalation of the free-base porphyrin to give [Fe(Por)Cl] was done as previously described.20 [Fe(Por)]2O was prepared according to a modified Fleischer preparation.21 Mössbauer measurements were performed on a constant acceleration spectrometer from 4.2 K to 300 K with optional small field and in a 9 T superconducting magnet system (Knox College). Samples for Mössbauer spectroscopy were prepared by immobilization of the crystalline material in Apiezon M grease. Sample homogeneity was shown with zero field Mössbauer spectra. Figure S1 gives the spectrum of [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)].

Synthesis of [Fe(Por)(Hdmpz)]

(Por = TPP or Tp-OCH3PP) [Fe(II)(Por)] was prepared by reduction of [Fe(Por)]2O (0.05 mmol) with ethanethiol (1 mL) in toluene (7 mL). The toluene solution was stirred three days, then transferred into a Schlenk flask containing 3,5-dimethylpyrazole (0.6 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 30 min, then filtered. X-ray quality crystals were obtained in 8 mm × 250 mm sealed glass tubes by liquid diffusion using hexanes as nonsolvent.

X-ray Structure Determinations

Single-crystal experiments were carried out on a Bruker Apex system with graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα radiation (). The structure was solved by direct methods and refined against F2 using SHELXTL;22,23 subsequent difference Fourier syntheses led to the location of most of the remaining non-hydrogen atoms. For the structure refinement all data were used including negative intensities. All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically if not remarked otherwise below. Hydrogen atoms were added with the standard SHELXL-97 idealization methods. The program SADABS24 was applied for the absorption correction. Brief crystal data for both structures are listed in Table 1. Complete crystallographic details, atomic coordinates, anisotropic thermal parameters, and fixed hydrogen atom coordinates are given in the Supporting Information.

Table 1.

Brief Crystallographic Data and Data Collection Parameters for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)].

| [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] | [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] | |

|---|---|---|

| formula | C49H36FeN6 | C60H52FeN6O4 |

| FW, amu | 764.69 | 976.93 |

| a, Å | 11.3032(2) | 11.9585(3) |

| b, Å | 30.8656(6) | 35.4853(9) |

| c, Å | 11.7462(2) | 11.9857(3) |

| β, deg | 105.358(1) | 106.949(1) |

| V, Å3 | 3951.67(12) | 4865.2(2) |

| space group | P21/c | P21/c |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Dc, g/cm3 | 1.285 | 1.334 |

| F(000) | 1592 | 2048 |

| μ, mm−1 | 0.424 | 0.367 |

| crystal dimensions, mm | 0.44 × 0.44 × 0.22 | 0.52 × 0.46 × 0.20 |

| absorption correction | SADABS | |

| radiation, MoKα, | 0.71073 Å | |

| temperature, K | 299(2) | 100(2) |

| total data collected | 84805 | 86053 |

| unique data | 11989 (Rint = 0.024) | 12075 (Rint = 0.048) |

| unique observed data [I > 2σ(I)] | 8806 | 10028 |

| refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | |

| final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0421, wR2 = 0.1121 | R1 = 0.0428, wR2 = 0.1047 |

| final R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0645, wR2 = 0.1272 | R1 = 0.0554, wR2 = 0.1132 |

[Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)]

Three crystals from three distinct preparations were measured by X-ray diffraction. The first two crystals were measured at 100 K; attempts to refine the structure gave unsatisfactorily high R1/ wR2 values. A detailed examination of the diffraction data showed that the rocking curves of most diffraction maxima were broad with shoulders. Attempts to integrate the data as twins failed. The third crystal was measured first at room temperature and then at 100 K. The data at room temperature gave satisfactory results, while the data at 100 K gave the same unsatisfactory result as the previous two measurements. In this paper, only the room temperature result will be presented.

A red crystal with the dimensions 0.44 × 0.44 × 0.22 mm3 was used for the structure determination. The asymmetric unit contains one porphyrin molecule and one 3,5-dimethylpyrazole ligand. The 3,5-dimethylpyrazole was found to be disordered over two positions, a major and a minor position. The minor 3,5-dimethylpyrazole was refined as a rigid group, and ISOR was applied, together with SIMU, to restrain their thermal displacement parameters. After the final refinement the occupancy of the major pyrazole orientation was found to be 92%. Four carbon atoms of one phenyl group of the porphyrin was found to be disordered over two positions, they were refined as C(42a), C(43a), C(45a), C(46a) and C(42b), C(43b), C(45b), C(46b) with 53% and 47% occupancy, respectively.

[Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]

A red crystal with the dimensions 0.52 × 0.46 × 0.20 mm3 was used for the structure determination. It was placed in inert oil, mounted on a glass pin, and transferred to the cold gas stream of the diffractometer. Crystal data were collected at 100 K. The asymmetric unit contains one porphyrin molecule, one 3,5-dimethylpyrazole ligand and one fully occupied toluene solvate. The 3,5-dimethylpyrazole was found to be disordered over two positions, a major and a minor position. The minor 3,5-dimethylpyrazole was refined as a rigid group. ISOR was applied, together with SIMU, to restrain the thermal displacement parameters of atoms of the minor 3,5-dimethylpyrazole. After the final refinement the occupancy of the major pyrazole orientation was found to be 92%.

The pyrazole plane of the minor orientation is close to being coplanar to the major orientation in both complexes studied; the major and minor orientations are both shown in the supporting information Figure S2.

Results

The two new five-coordinate pyrazole-ligated iron(II) porphyrinates were synthesized starting from the corresponding iron(III) μ-oxo derivatives ([Fe(por)]2O). Ethanethiol reduction to give the iron(II) species [Fe(por)] was followed by reaction with a hindered pyrazole ligand. The structures of two derivatives have been obtained: [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]. The data for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] were collected at 100 K three times and at room temperature once. Data collections at 100 K had broadened peaks that were not adequately integrated, and larger than acceptable values of R1 and wR2 were obtained. Nonetheless, the structures from the three low temperature data sets were very similar. A satisfactory data set was only obtained at room temperature, but all data gave the same structure.

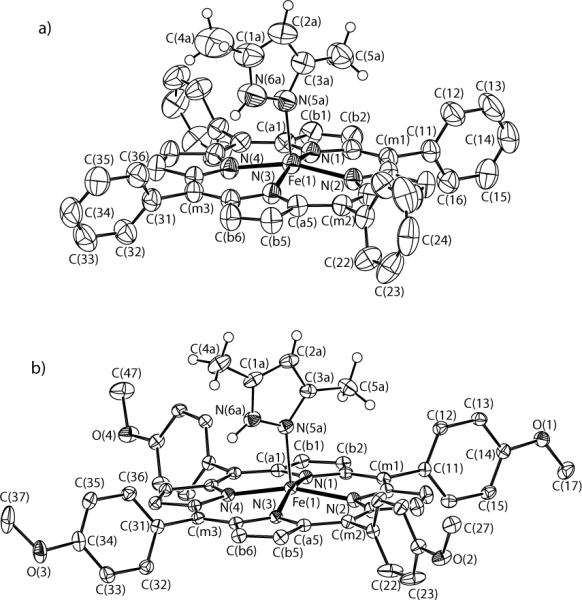

ORTEP diagrams for both new species are shown in Figure 1. Only the major 3,5-dimethylpyrazole orientation is given in this figure. The dihedral angles ϕ between the pyrazole plane and the plane defined by N(1), Fe(1), N(5a) are 36.8 and 45.4°, respectively. In each structure, the pyrazole plane is almost perpendicular to the porphyrin plane with a dihedral angle of 87.7 or 82.3°, respectively. ORTEP diagrams showing both orientations of pyrazole are provided in the Supporting Information (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagram of two pyrazole-ligated species. a) [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)]. The major orientation of the pyrazole (92%) and phenyl ring atoms (C(42a), C(43a), C(45a), C(46a) with 53% occupancy) are shown. b) [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]. The major orientation of the pyrazole (92%) is shown. The hydrogen atoms of the porphyrin ligand have been omitted for clarity. 50% probability ellipsoids are depicted.

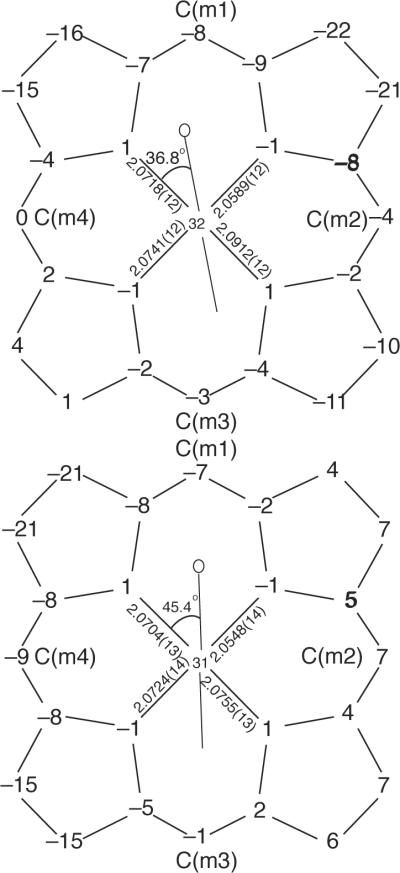

Figure 2 gives formal diagrams of the porphyrin cores and shows the displacements of each atom from the mean plane of the four pyrrole nitrogen atoms in units of 0.01 Å. The orientation of the pyrazole ligand with respect to the core atoms are shown by the line with the circle representing the methyl group bound at the α-position of the coordinated nitrogen. Also included on the diagrams of Figure 2 are the individual Fe–Np bond lengths. An analogous diagram showing atomic displacements from the mean plane of 24-atom porphyrin core is given in the supporting information (Figure S3). A complete listing of bond distances and angles is given in the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Formal diagrams of the porphyrinato cores. [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] (top) and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] (bottom). Illustrated are the displacements of each atom from the mean plane of the four pyrrole nitrogen in units of 0.01 Å. Positive values of displacement are toward the imidazole ligand. The diagrams also show the orientation of the pyrazole ligand with respect to the atoms of the porphyrin core. The location of the methyl group at the α-position of the coordinated nitrogen is represented by the circle.

Crystalline [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] was studied by variable-temperature Mössbauer spectroscopy at zero field and applied magnetic fields. Both the quadrupole splitting and isomer shift values show a strong temperature dependence. The quadrupole splitting for the crystalline species [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] at 4.2 K is 2.54 mm/s and at 298 K is 1.86 mm/s. The isomer shifts at these respective temperatures are 0.91 and 0.78 mm/s. The values of Mössbauer quadrupole doublets and isomer shifts at various temperatures are given in the Supporting Information.

Discussion

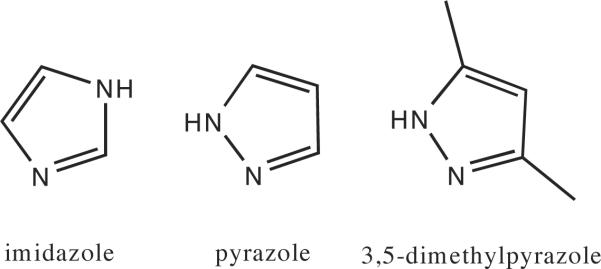

The goal of this study was to further examine the electronic configuration and structural differences caused by axial ligands in high-spin five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates. Pyrazole was used as fifth ligand in this paper; the difference between the imidazole and pyrazole rings is that a carbon and a nitrogen atom exchange positions (see Scheme 1). A sterically hindered pyrazole must be used in order to obtain five-coordinate species rather than a six-coordinate species.25 Because of the tautomeric forms possible for pyrazole, both the 3- and 5- positions must be methylated. Thus 3,5-dimethylpyrazole was chosen as the ligand, and two new five-coordinate iron(II) pyrazole-ligated porphyrinates were obtained. To the best of our knowledge, these derivatives are the first structurally characterized examples of five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates with a nonimidazole neutral ligand.

Scheme 1.

In addition to the atom position differences in the five-membered ring, pyrazole is less basic than imidazole; the pKa of protonated pyrazole (2.52) is much smaller that of protonated imidazole (6.95).26 Although the Lewis basicity of pyrazoles is also weaker than that of imidazoles,27 Sorrell has shown that two-coordinate pyrazole-ligated Cu(I) will react with CO to form an adduct whereas the two coordinate imidazole derivatives do not.28 How will this influence the coordination behavior in their five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinate derivatives?

Structural Studies

The structures of [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] both show that the overall features are as expected for a high-spin iron(II) complex,10,29 such as large equatorial Fe–Np bond distances, a significant out-of-plane displacement of the iron(II) atom and an expanded porphinato core.

The average Fe–Np bond length is 2.074(13) Å for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and 2.068(9) Å for [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)], and the Fe–Nax bond length is 2.1519(18) Å or 2.1414(18) Å, respectively. These values are similar to those of the imidazole-ligated porphyrinates as shown in Table 2. The comparison indicates that the coordination abilities to iron(II) for imidazole and pyrazole are very similar in the five-coordinate iron(II)porphyrinates even though pyrazole is less basic than imidazole.26

Table 2.

Selected Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)], [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] and Related Speciesa

| Complexb | Fe–Npc,d | Fe–NImd | ΔN4d,e | Δd,f | Ct⋯Nd | Fe–N–Cg,h | Fe–N–Xg,i | θg,j | ϕg,k | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] | 2.074(13) | 2.1519(18) | 0.32 | 0.38 | 2.049 | 139.38(16) | 116.14(14) | 7.1 | 36.8 | tw |

| [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] | 2.068(9) | 2.1414(18) | 0.31 | 0.34 | 2.045 | 136.21(16) | 118.99(13) | 9.8 | 45.4 | tw |

| [Fe(TPP)(2-MeHIm)]·1.5C6H5Cl | 2.073(9) | 2.127(3)l | 0.32 | 0.38 | 2.049 | 131.1(2) | 122.9(2) | 8.3 | 24.0 | 5 |

| [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(2-MeHIm)] | 2.087(7) | 2.155(2)l | 0.39 | 0.51 | 2.049 | 130.4(2) | 123.4(2) | 8.6 | 44.5 | 10 |

| [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | 2.077(6) | 2.137(4) | 0.35 | 0.38 | 2.046 | 131.9(3) | 122.7(3) | 6.1 | 20.7 | 10 |

| [Fe(TPP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | 2.079(8) | 2.158(2)l | 0.36 | 0.42 | 2.048 | 129.3(2) | 124.9(2) | 11.4 | 20.9 | 10 |

| [Fe(TTP)(2-MeHIm)] | 2.076(3) | 2.144(1) | 0.32 | 0.39 | 2.050 | 132.8(1) | 121.4(1) | 6.6 | 35.8 | 10 |

| [Fe(OEP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | 2.080(6) | 2.171(3) | 0.37 | 0.45 | 2.047 | 132.7(3) | 121.4(2) | 3.8 | 10.5 | 12 |

| [Fe(OEP)(2-MeHIm)] | 2.077(7)) | 2.135(3) | 0.34 | 0.46 | 2.049 | 131.3(3) | 122.4(3) | 6.9 | 19.5 | 12 |

| [Fe(TPP)(2-MeHIm)](2-fold) | 2.086(8) | 2.161(5) | 0.42 | 0.55 | 2.044 | 131.4(4) | 122.6(4) | 10.3 | 6.5 | 30 |

| average of the eight | 2.080(5) | 2.147(16) | 0.36(3) | 0.44(6) | 2.048(2) | 131.4(12) | 122.7(11) | 7.8(24) | ||

| [Fe(TpivPP)(2-MeHIm)] | 2.072(6) | 2.095(6) | 0.40 | 0.43 | 2.033 | 132.1(8) | 126.3(7) | 9.6 | 22.8 | 31 |

| [Fe(Piv2C8P)(1-MeIm)] | 2.075(20) | 2.13(2) | 0.31 | 0.34 | 2.051 | 126.5 | 120.4 | 5.0 | 34.1 | 32 |

| [K(222)][Fe(OEP)(2-MeIm−)] | 2.113(4) | 2.060(2) | 0.56 | 0.65 | 2.036 | 136.6(2) | 120.0(2) | 3.6 | 37.4 | 11 |

| [K(222)] [Fe(TPP)(2-MeIm−)] | 2.118(13) | 1.999(5) | 0.56 | 0.66 | 2.044 | 129.6(3) | 126.7(3) | 9.8 | 23.4 | 11 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(2-MeIm−)]− | 2.11(2) | 2.002(15) | 0.52 | 0.65 | 2.045 | NRm | NR | 5.1 | 14.7 | 17 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)Cl]− | 2.108(15) | 2.301(2)n | 0.53 | 0.59 | 2.040 | – | – | – | – | 14 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(O2CCH3)]− | 2.107(2) | 2.034(3)o | 0.55 | 0.64 | 2.033 | – | – | – | – | 15 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(OC6H5)]− | 2.114(2) | 1.937(4)o | 0.56 | 0.62 | 2.037 | – | – | – | – | 15 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(SC6HF4)]− | 2.076(20) | 2.370(3)p | 0.42 | NR | 2.033 | – | – | – | – | 14 |

| [Fe(TPP)(SC2H5)]− | 2.096(4) | 2.360(2)p | 0.52 | 0.62 | 2.030 | – | – | – | – | 16 |

Estimated standard deviations are given in parentheses.

All complexes are high spin.

Averaged value.

in Å.

Displacement of iron from the mean plane of the four pyrrole nitrogen atoms.

Displacement of iron from the 24-atom mean plane of the porphyrin core.

Value in degrees.

the α-carbon of the coordinated nitrogen.

Imidazole 4-carbon or pyrazole 1-nitrogen.

Off-axis tilt (deg) of the Fe–NIm bond from the normal to the porphyrin plane.

Dihedral angle between the plane defined by the closest Np –Fe–NIm and the imidazole plane in deg.

Major imidazole orientation.

Not reported.

Chloride.

Anionic oxygen donor.

Thiolate.

The structural similarities between pyrazole- and imidazole-ligated species are also shown in other aspects, such as iron displacement and core expansion. As shown in Table 2, the out-of-plane displacement of the iron atom from the mean 24-atom porphyrin core (Δ) and the plane defined by the four pyrrole atoms (ΔN4) are similar to those for imidazole-ligated porphyrinates. The iron displacements in the two species are 0.38 and 0.34 Å out of the 24-atom plane and 0.32 and 0.31 Å out of the four pyrrole nitrogen atom plane. The difference in the two values (note that Δ is always larger than ΔN4) is a measure of porphyrin core doming and is 0.06 Å for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and 0.03 Å for [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]. The porphyrin plane in [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] shows a conformation similar to doming, but with three rings down and one pyrrole ring slightly up, the effect may be better described as that of a tenting conformation.33 The porphyrin plane in [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] is folded along a pair of opposite methine carbons. Both of these conformations have been observed in imidazole-ligated species. The core conformations have also been analyzed by the normal structural decomposition (NSD) method provided by Shelnutt et al.34, 35 and are given in supporting information Table S15. The results show that the major conformations are doming; other conformation contributions, such as ruffling, saddling, are very small.

The large iron(II) ion is accommodated in the central hole of the porphyrin ring not only by the iron atom displacements and long Fe–Np bond distances but also by radial expansion of the core.36 The radii of the central hole (Ct⋯N in Table 2) for the two new species are 2.049 and 2.045 Å, which are similar to those for imidazole-ligated species.

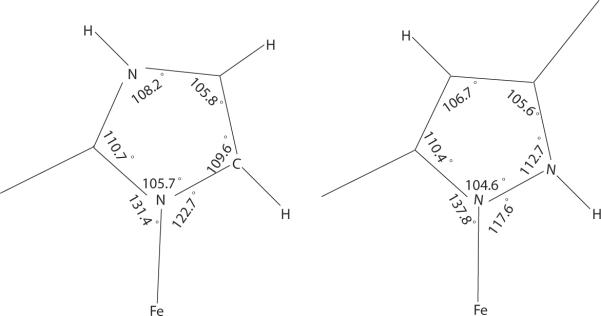

The steric bulk of the methyl group at the α-position of the coordinated nitrogen leads to, in all hindered imidazole and pyrazole derivatives examined to date, an off-axis tilt of the axial Fe–N bond and a rotation of the axial ligand that leads to unequal Fe–Nax–X (X = C or N) angles. The pyrazole ligand Fe–N bond vector is tilted off of the normal to the 24-atom porphyrin mean plane. The values of the tilt angle, given by θ in Table 2, are 7.1° for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and 9.8° for [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]. This tilting is the partial result of minimizing the interaction between the bulky imidazole methyl group and the porphyrin core.

One difference between pyrazole- and imidazole-ligated species is the Fe–Nax–X angles (Table 2). For the pyrazole-ligated species they are 139.38(16), 116.14(14) and 136.2, 119.0°, much different from the angles for imidazole-ligated species which have an average value of 131.4(12)° on the methyl side and 122.7(11)° on the other side. Considering the difference between imidazole and pyrazole, the unsubstituted α position of the coordinated nitrogen in pyrazole is a nitrogen as opposed to the carbon atom in imidazole. The corresponding N–H is about 0.1 Å shorter than C–H, which causes less interaction between that hydrogen and porphyrin core and allows the axial ligand to rotate more toward that direction. Figure 3 compares the differences.

Figure 3.

Diagram illustrating the differing average internal angles in imidazole-ligated (left) and pyrazoleligated (right) high-spin iron(II) derivatives.

Besides the difference of the Fe–Nax–X angles, another difference between pyrazole and imidazole isomers is the possibility of forming hydrogen bonds involving the N–H group. The N–H group faces toward the porphyrin plane when pyrazole is coordinated to iron; this orientation rules out the possibility of hydrogen bonding. However, the N–H group is away from the porphyrin plane when imidazole is coordinated to iron and this orientation allows the formation of hydrogen bonds. Indeed, the latter is common in biological systems.

Both pyrazole- and imidazole-ligated species have distinctly different structural features than porphyrins having coordinated anionic ligand species (Table 2). In the latter, the Fe–Np bond distances are much longer and the Fe–Nax distance is much shorter; further, the displacements of iron(II) are much larger (0.10–0.20 Å) than those of the imidazole- or pyrazole-ligated species. Thus the structural data show that the pyrazole-ligated species are much like the imidazole-ligated species and not the anionic ligated species. Does this hold true for the species's electronic structures?

Electronic Structure

Previous studies on imidazole- and imidazolate-ligated five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates have shown that these represent two distinct groups with different electronic configurations.10,11,13 Mössbauer spectra of the imidazolate-ligated and other anionic-ligated species show a large positive value of the quadrupole splitting with a small asymmetry parameter (η); they have the normal doubly occupied dxy ground state, (dxy)2(dxz)1(dyz)1−(dz2)1(dx2−y2)1. On the other hand, Mössbauer spectra of the imidazole-ligated species, including deoxymyoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin, show a negative value of the quadrupole splitting with large asymmetry parameters; the doubly-occupied d orbital can be best described as a hybrid orbital comprised of a linear combination of dxz, dyz orbitals, and a modest contribution from the dxy orbital that is consistent with the low symmetry.13

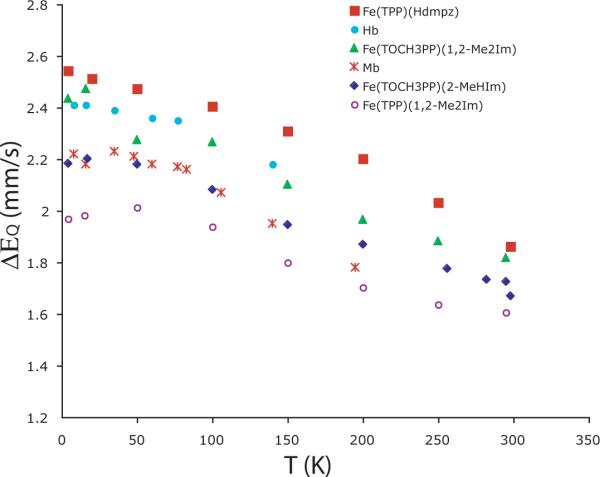

The Mössbauer data of [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] shows features similar to those of imidazole-ligated species. The value of quadrupole splitting (ΔEq) observed at 4.2 K is 2.54 mm/s, similar to those previously reported for high-spin iron(II) species as shown in Table 3.10,37 The large value of the isomer shift (δ~0.91 mm/s) is also consistent with high-spin iron(II).41 There is substantial temperature variation of the quadrupole splitting values; complete values of δ and ΔEq vs. T are tabulated in Table S13. A plot of the data for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and related species is given in Figure 4. The value of ΔEq decreases significantly as the temperature is increased. The observed temperature dependence of ΔEq is similar to the variation seen for imidazole-ligated samples.6,10,11,37,42–47 As discussed previously,10 the explanation for this temperature variation is that there are close-lying excited states. The excited states could have the same or differing spin multiplicity relative to the ground state. These data clearly suggest that the pyrazole-ligated species have the same electronic structure as those imidazole-ligated species, which is further confirmed by the Mössbauer data under applied magnetic fields.

Table 3.

Möossbauer Parameters for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and Related Five-Coordinate Imidazole-Ligated Iron(II) porphyrinates

| Complex | Δ EQa | δ Fea | Γ b | T, K | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] | −2.54 | 0.91 | 0.43 | 4.2 | tw |

| [Fe(TPP)(2-MeHIm)] | −2.40 | 0.92 | 0.50 | 4.2 | 5 |

| [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | −2.44 | 0.95 | 0.46 | 4.2 | 10 |

| [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(2-MeHIm)] | −2.18 | 0.94 | 0.58 | 4.2 | 10 |

| [Fe(TPP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | −1.93 | 0.92 | 0.44 | 4.2 | 10 |

| [Fe(TPP)(2-MeHIm)] | −1.96 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 4.2 | 10 |

| [Fe(TTP)(2-MeHIm)] | −1.95 | 0.85 | 0.42 | 4.2 | 10 |

| [Fe(TTP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | −2.06 | 0.86 | 0.43 | 4.2 | 10 |

| [Fe(OEP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | −2.23 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 4.2 | 12 |

| [Fe(OEP)(2-MeHIm)] | −1.96 | 0.90 | 0.41 | 4.2 | 12 |

| [Fe(TPP)(2-MeHIm)(2-fold) | −2.28 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 4.2 | 37 |

| [Fe(TPP)(1,2-Me2Im)] | −2.16 | 0.92 | 0.25 | 4.2 | 37 |

| [Fe((Piv2C8P)(1-MeIm)] | −2.3c | 0.88 | 0.40 | 4.2 | 32 |

| Hb | −2.40 | 0.92 | 0.30 | 4.2 | 37 |

| Mb | −2.22 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 4.2 | 37 |

| [K(222)][Fe(OEP)(2-MeIm−)] | +3.71 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 4.2 | 11 |

| [K(222)][Fe(TPP)(2-MeIm−)] | +3.60 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 4.2 | 11 |

| [Fe(TPpivP) (2-MeIm−)] − | +3.51d | 0.97 | 77 | 17 | |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(SC2H5)]− | +2.18 | 0.83 | 0.30 | 4.2 | 38 |

| [Fe(OC6H5)(TPP)]− | +4.01 | 1.03 | 4.2 | 39 | |

| [Fe(O2CCH3)(TpivPP)]− | +4.25 | 1.05 | 0.30 | 4.2 | 40 |

| [Fe(OCH3)(TpivPP)]− | +3.67d | 1.03 | 0.40 | 4.2 | 15 |

| [Fe(OC6H5)(TpivPP)]− | +3.90d | 1.06 | 0.38 | 4.2 | 15 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(SC6HF4)][NaC12H24O6] | +2.38d | 0.84 | 0.28 | 4.2 | 38 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)(SC6HF4)][Na(222)] | +2.38d | 0.83 | 0.32 | 4.2 | 38 |

| [Fe(TpivPP)Cl]− | +4.36d | 1.01 | 0.31 | 77 | 14 |

mm/s.

Line width, FWHM.

Sign not determined experimentally, presumed negative.

Sign not determined experimentally, presumed positive.

Figure 4.

Plot illustrating the temperature-dependent quadrupole splitting values in the Mössbauer data.

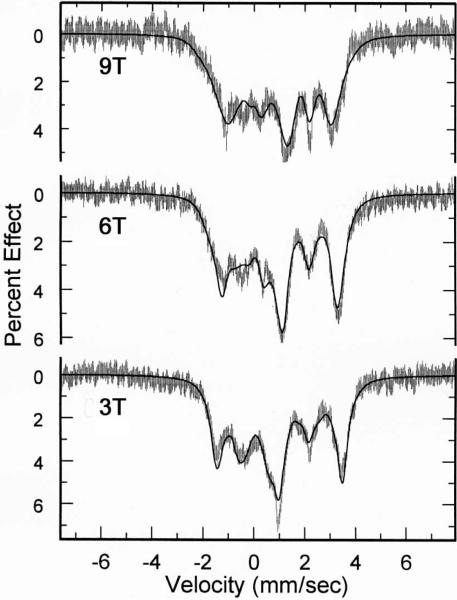

The application of applied magnetic field Mössbauer spectroscopy provides more detailed information concerning the electronic ground states. The Mössbauer data in strong magnetic fields shown in Figure 5 were fit with the spin Hamiltonian model used by Kent et al.37

where D and E are the axial and rhombic zero-field splitting parameters that describe the fine structure of the S = 2 multiplet, is the magnetic hyperfine tensor and HQ gives the nuclear quadrupole interaction:

Q is the quadrupole moment of the 57Fe nucleus and η = (Vxx − Vyy)/Vzz, where Vii are components of the electric field gradient. The quadrupole splitting and isomer shift were constrained to the values determined from the zero-field data.

Figure 5.

Mössbauer data and fits obtained for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] at 3 T, 6 T, 9 T applied magnetic fields. Fitting parameters were D =9.4 cm−1, E/D = 0.29 A/(gnβn) = (−6.8, −6.8, −2.2)T. Euler angles (D relative to Q)(α, β, γ) = (−58, 36, 31)°. Lorentzian FWHM = 0.43 mm/s. Simulations of 3, 6, and 9T spectra at 4.2K assume slow spin relaxation.

An analysis of the spectra shows the largest component of the electric field gradient, Vzz, has a negative value and hence the sign of the quadrupole splitting value is also negative. The asymmetry parameters for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] (0.74) is relatively large, which is consistent with those for imidazole-ligated species.10,37,42–47 The large asymmetry parameter indicates the low symmetry of the electric field gradient (EFG), which is also reflected in the solid-state structure. Our earlier study suggested that imidazole-ligated species are unique and have an unusual electronic configuration. Mössbauer study of [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] indicates that pyrazole, another neutral ligand, functions just as imidazole in the five-coordinate iron(II) porphyrinates.

Summary

We have synthesized two pyrazole-ligated five-coordinate high-spin iron(II) porphyrinates, [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]. Despite the structural and ligand basicity difference between pyrazole and imidazole, the X-ray crystallography suggests that these new pyrazole species have similar structural features as the imidazole-ligated species, which indicates that the new neutral ligand, pyrazole, has similar coordination ability as imidazole to the iron(II) porphyrinate. Consistent with the structural studies, Mössbauer spectra at variable temperature and applied magnetic fields for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] further confirm that the new species have the same electronic structure as the imidazole-ligated species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor N. Lehnert (Univ. of Michigan) for helpful discussions. We thank the National Institutes of Health for support of this research under Grant GM-38401 to WRS and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 20971093) to CH. We thank the NSF for X-ray instrumentation support through Grant CHE-0443233.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Figure S1 displays the zero field Mössbauer spectrum of [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)]. Figure S2 shows ORTEP diagrams of [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)] including all the disordered atoms. Figure S3 displays displacements from the 24-atom plane. Tables S1–S12 give complete crystallographic details, atomic coordinates, bond distances and angles, anisotropic temperature factors, and fixed hydrogen atom positions for [Fe(TPP)(Hdmpz)] and [Fe(Tp-OCH3PP)(Hdmpz)]. Tables S13 and S14 give full details on the observed Mössbauer data and the fits. Table S15 shows analysis results of the core conformations by the normal structural decomposition method. This information is available as a PDF file. The crystallographic information files (CIF) are also available. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- (1).Rovira C, Kunc K, Hutter J, Ballone P, Parrinello M. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1997;101:8914. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kozlowski PM, Spiro TG, Zgierski MZ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:10659. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Liao M-S, Scheiner S. J. Chem. Phys. 2002;116:3635. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ugalde JM, Dunietz B, Dreuw A, Head-Gordon M, Boyd RJ. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2004;108:4653. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ellison MK, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:2173. doi: 10.1021/ic020012g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kent TA, Spartalian K, Lang G. J. Chem. Phys. 1979;71:4899. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Nakano N, Otsuka J, Tasaki A. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1971;236:222. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(71)90169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nakano N, Otsuka J, Tasaki A. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1972;278:355. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(72)90240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Alpert A, Banerjee R. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1975;405:114. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hu C, Roth A, Ellison MK, An J, Ellis CM, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;1(27):5675. doi: 10.1021/ja044077p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hu C, Noll BC, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;1(27):15018. doi: 10.1021/ja055129t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hu C, An J, Noll BC, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:4177. doi: 10.1021/ic052194v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hu C, Sulok CD, Paulat F, Lehnert N, Twigg AI, Hendrich MP, Schulz CE, Scheidt WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3737. doi: 10.1021/ja907584x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Schappacher M, Ricard L, Weiss R, Montiel-Montoya R, Gonser U, Bill E, Trautwein AX. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1983;78:L9. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Nasri H, Fischer J, Weiss R, Bill E, Trautwein AX. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:2549. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Caron C, Mitschler A, Riviere G, Schappacher M, Weiss R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:7401. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Mandon D, Ott-Woelfel F, Fischer J, Weiss R, Bill E, Trautwein AX. Inorg. Chem. 1990;29:2442. [Google Scholar]

- (18).The following abbreviations are used in this paper: Hdmpz, 3,5-dimethylpyrazole; Por, dianion of general porphyrin; Tp-OCH3PP, dianion of meso-tetra-p-methoxyphenylporphyrin; TPP, dianion of meso-tetraphenylporphyrin; TTP, dianion of meso-tetratolylporphyrin; OEP, dianion of octaethylporphyrin; TpivPP, dianion of α,α,α,α-tetrakis(o-pivalamidophenyl)porphyrin; Piv2C8P, dianion of α,α,5,15-[2,2'-(octanediamido)diphenyl]-α,α,10–20-bis(o-pivalamidophenyl)porphyrin; Im, generalized imidazole; RIm, generalized hindered imidazole; HIm, imidazole; 1-MeIm, 1-methylimidazole; 2-MeHIm, 2-methylimidazole; 1,2-Me2Im, 1,2-dimethylimidazole; 2-MeIm−, 2-methylimidazolate; 222, Kryptofix 222; Np, porphyrinato nitrogen; Nax, nitrogen atom of axial ligand; Ct, the center of four porphyrinato nitrogen atoms.

- (19).Adler AD, Longo FR, Finarelli JD, Goldmacher J, Assour J, Korsakoff L. J. Org. Chem. 1967;32:476. [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Adler AD, Longo FR, Kampus F, Kim J. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1970;32:2443. [Google Scholar]; (b) Buchler JW. Chapter 5. In: Smith KM, editor. Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins. Elsevier Scientific Publishing; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Fleischer EB, Srivastava TS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:2403. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoffman AB, Collins DM, Day VW, Fleischer EB, Srivastava TS, Hoard JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:3620. doi: 10.1021/ja00765a060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A. 2008;A64:112. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).R1 = Σ || Fo| − |Fc || / Σ |Fo| and wR2 = {Σ [w (Fo2 − Fc2)2] / Σ [w(Fo2)2]}1/2. The conventional R-factors R1 are based on F, with F set to zero for negative F2. The criterion of F2 > 2σ(F2) was used only for calculating R1. R-factors based on F2 (wR2) are statistically about twice as large as those based on F, and R-factors based on ALL data will be even larger.

- (24).Sheldrick GM. SADABS. Universität Göttingen; Göttingen, Germany: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Collman JP, Reed CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2048. doi: 10.1021/ja00787a075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).a) Elguero E, Gonzalez E, Jacquier R. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1968:5009. [Google Scholar]; b) Catalán J, Elguero J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1983;12:1869. [Google Scholar]

- (27).El Ghomari MJ, Mokhlisse R, Laurence C, Le Questel J-Y, Berthelot M. J Phys. Org. Chem. 1997;10:669. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sorrell TN, Jameson DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:6013. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Scheidt WR, Reed CA. Chem. Rev. 1981;81:543. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Collman JP, Kim N, Hoard JL, Lang G, Radonovich LJ, Reed CA. Abstracts of Papers. 167th National Meeting of the American Chemical Society; Los Angeles, CA. April 1974; Washington, D. C.: American Chemical Society; INOR 29. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Jameson GB, Molinaro FS, Ibers JA, Collman JP, Brauman JI, Rose E, Suslick KS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:3224. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Momenteau M, Scheidt WR, Eigenbrot CW, Reed CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1207. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kirner JF, Reed CA, Scheidt WR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:2557. doi: 10.1021/ja00450a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Sun L, Shelnutt JA. Program is available via the internet at http://jasheln.unm.edu.

- (35).Jentzen W, Ma J-G, Shelnutt JA. Biophys. J. 1998;74:753. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74000-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Scheidt WR, Gouterman M. In: Iron Porphyrins, Part One. Lever ABP, Gray HB, editors. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1983. p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kent TA, Spartalian K, Lang G, Yonetani T, Reed CA, Collman JP. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1979;580:245. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(79)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Schappacher M, Ricard L, Fisher J, Weiss R, Montiel-Montoya R, Bill E. Inorg. Chem. 1989;28:4639. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Shaevitz BA, Lang G, Reed CA. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:4607. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bominaar EL, Ding X, Gismelseed A, Bill E, Winkler H, Trautwein AX, Nasri H, Fisher J, Weiss R. Inorg. Chem. 1992;3(1):1845. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Debrunner PG. Chapter 2. In: Lever ABP, Gray HB, editors. Iron Porphyrins Part 3. VCH Publishers Inc.; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kent TA, Spartalian K, Lang G, Yonetani T. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1977;490:331. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bade D, Parak F. Biophys. Struct. Mechanism. 1976;2:219. doi: 10.1007/BF00535368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Eicher H, Bade D, Parak F. J. Chem. Phys. 1976;64:1446. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Huynh BH, Paraefthymiou GC, Yen CS, Wu CS. J. Chem. Phys. 1974;61:3750. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Eicher H, Trautwein A. J. Chem. Phys. 1970;52:932. doi: 10.1063/1.1673077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Eicher H, Trautwein A. J. Chem. Phys. 1969;50:2540. doi: 10.1063/1.1671413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.