Abstract

Because abdominoplasty is associated with complications such as seroma and necrosis as well as epigastric bulging and a suprapubic scar located too high, the demand for this procedure is not as high as it otherwise might be. However, although these negative effects were common many years ago, their incidence has decreased dramatically with modern abdominoplastic techniques. One approach using a combination of abdominoplasty and liposuction or lipoabdominoplasty has resolved many of the problems faced with earlier techniques, offering aesthetically pleasing results and excellent reliability. The keys to successful lipoabdominoplasty, first developed as the high-superior-tension technique, are extensive liposuction, preservation of lymphatic trunks, preaponeurotic epigastric dissection, major muscle fascia plication, two high-tension paraumbilical sutures, hypogastric tension sutures, and closure of the dead spaces. The most recent updates to this technique are described in this article.

Keywords: Abdominoplasty, Lipoabdominoplasty, Body contouring, Miniabdominoplasty, Seroma

According to a 2010 report by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons [1], liposuction and abdominoplasty (“tummy tuck”) were the fourth and fifth most frequently performed cosmetic surgical procedures, respectively, in 2009. Although the report does not specify how many liposuctions and abdominoplasties were performed concurrently, there is increasing interest in this approach, termed “lipoabdominoplasty.” In this review article, we present a brief history and overview of liposuction, abdominoplasty, and lipoabdominoplasty; describe our technique of high-superior-tension abdominoplasty (HSTA); and comment on the work of others.

Historical Perspective

Although the first liposuction procedures for humans were performed in the early 1980s [2], abdominoplasty has been performed in Europe and the United States since the turn of the 20th century, when Demars and Marx [3] undertook an extensive fat resection in the abdominal wall, including the umbilical area, in 1890. In the United States in 1899, Kelly [4] used the term “abdominal lipectomy” to describe the transverse resection of a large pendulous abdominal wall. Gaudet and Morestin [5] published an article 15 years later on transverse closure of large umbilical hernias, resection of excess skin and fat, and, for the first time, preservation of the umbilicus. In Germany in 1909, Weinhold [6] reported his experience with a combination of vertical and transverse cloverleaf-shaped incisions. In 1911, Morestin [7] reported his series of five patients who underwent massive dermolipectomy using transverse incisions.

In the 1960s, attention turned to using abdominoplasty for body contouring, and two surgeons, Callia [8] and Pitanguy [9], developed procedures in which large underminings improved efficacy of the technique. Using a different approach, Illouz [2, 10] became the first to use liposuction to modify body contour, which was a great step forward.

Abdominoplasty and Liposuction

Despite these advancements, however, a significant complication rate still is associated with abdominoplasty including flap necrosis, seroma, hematoma, infections, fat necrosis, wound dehiscence, and delayed healing. Because this procedure involves extensive undermining, denervation occurs, and the skin flap loses vascularity. The flap, with its reduced blood flow and innervation, then is stretched maximally and sutured under tension, which results in ischemia and lack of sensation in the lower abdominal skin. Moreover, even with adequate drainage, there still is a high rate of postoperative seroma [11].

Another drawback to abdominoplasty has been its contraindication for obese patients due to the need for an ample supply of loose skin and rectus muscle diastasis as well as a limited amount of fat in the abdominal area [11]. Although many patients can lose weight to become eligible for surgery, many others are unsuccessful. For the latter group, a two-step process of abdominoplasty followed by liposuction 6 months later, or vice versa, has been advocated.

However, regardless which procedure is performed first, this approach has significant limitations. On the one hand, liposuction may induce fibrosis, hampering subsequent abdominoplasty. On the other hand, performing abdominoplasty first exposes obese patients to a high rate of complications while leaving behind a fatty abdominal wall, leading to skin laxity after subsequent liposuction [11].

Lipoabdominoplasty

The complications inherent in subjecting patients to two separate procedures, coupled with the ever-increasing rate of obesity worldwide, led to a search for a better approach. In 1987, Cardoso de Castro et al. [12] reported their experience combining limited-incision abdominoplasty with liposuction (lipoabdominoplasty) for 20 patients. With this technique, they were able to achieve a natural contour of the abdominal wall and umbilicus, maintenance of the mons pubis, and limited scarring. Dillerud [13], in a review of 487 patients undergoing lipoabdominoplasty, found that liposuction did not carry a significant additional risk when performed with abdominoplasty, although this study did not include control subjects. Ousterhout [14] safely combined suction-assisted lipectomy (liposuction), surgical lipectomy, and abdominoplasty, although that was not the case for most of the authors. All patients were pleased with the results, and only two relatively minor complications occurred.

In 1995, Matarasso [15] established a risk profile classification that has proved beneficial for selecting patients to undergo lipoabdominoplasty. This system classifies patients as type 1 (those who can be treated with liposuction alone), type 2 (those who require a miniabdominoplasty), type 3 (those who require a modified abdominoplasty in which the umbilicus must be closed separately after transposition), and type 4 (those who need a full abdominoplasty).

HSTA

To address the problem of seroma formation and other complications, we published several reports from 1992 to the present detailing our experience with HSTA [16–20]. Because this technique preserves the inguinal and axillary lymphatic trunks, it prevents seroma formation. Also, because this approach combines epigastric tunnel dissection and liposuction and uses two paraumbilical high-tension sutures, it eliminates epigastric bulging, suprapubic necrosis, and a scar located too high above the suprapubic area.

Because undermining in HSTA is limited, the nerves in the abdominal flap are largely preserved. Therefore, sensation in the abdominal wall is not lost as it often is with traditional abdominoplasty [21]. Furthermore, in a review of 161 patients who underwent lipoabdominoplasty (n = 93) or traditional abdominoplasty (n = 68), Samra et al. [22] found no statistically significant increase in perfusion-related complications between the two groups, although lipoabdominoplasty involves potential trauma to the vascularity of the elevated abdominoplasty flap.

Using a similar approach, Lockwood [23] in 1995 reported on 50 patients undergoing high-lateral-tension abdominoplasty with or without liposuction for moderate to severe abdominal skin and muscle laxity with or without truncal fat deposits. During a follow-up period of 4 to 16 months, complication rates were equal to or lower than those for historical controls and no higher than those for the patients who had liposuction. The key components of this procedure include direct undermining only in the paramedian area, discontinuous undermining to costal margins and flanks as needed, lateral placement of the highest-tension wound-closure suture, superficial fascial system repair with permanent sutures along the entire incision, and liberal adjunctive liposuction in the upper abdomen and lateral and posterior trunk. Because tension on the midline was low, a vertical suprapubic incision frequently was associated with the horizontal incision.

In 2008, Rangaswamy [11] also refined the procedure by incorporating key points of the HSTA technique, minimizing undermining, raising the abdominal flap just on the undersurface of Scarpa’s fascia, setting the new umbilicus 1 to 2 cm cranial to the upper border of the isolated umbilicus, and obliterating the dead space in the infraumbilical area with quilting sutures. In his experience performing lipoabdominoplasty for more than 120 mostly obese patients, he was able to extend the indications for this procedure to include even patients classified as type 3. In this series, 20 complications (all minor) occurred for 18 patients, and further analysis showed that only 4.8% of the complications were directly attributable to the procedure. There were no seromas, wound infections, or significant delays in healing and only two hematomas.

In other reports, Baroudi and Ferreira [24, 25] described their use of a handlebar incision that follows the natural inguinal curve and quilting sutures to close the dead space, which prevents seroma. In 2000, Pollock and Pollock [26] presented a retrospective review of 65 consecutive patients who underwent abdominoplasty with progressive tension sutures to close the dead space and lightly lower the abdominal flap. No tension suture was present near the umbilicus. The authors found the local complication rate to be very low compared with historical controls. During an average follow-up period of 18 months, no hematoma, seroma, or skin flap necrosis was reported.

As in previous reports of HSTA, Saldanha et al. [27] in 2003 described a lipoabdominoplasty with selective dissection (preservation of the inguinal and axillary lymphatic trunks and epigastric tunnel dissection) but with a too-high suprapubic scar resulting from the lack of paraumbilical high-tension sutures. No quilting sutures were used to close the dead space, and there were only two cases of seroma.

In 2009, Uebel [28] reported a revision of the superior pull-down abdominal flap described in 1975 by Sinder [29]. This revision added tunnel dissection, preservation of the inguinal and axillary lymphatic trunks, and paraumbilical high-tension sutures, as we describe in our reports of HSTA [16–20] and in this article.

HSTA Technique

Between 1991 and 2010, we treated 1,025 patients (912 women and 113 men) ages 29 to 74 years using HSTA. We describe our technique.

Anatomic Bases

Preservation of the Lymphatic Trunks

The main complication of abdominoplasty is seroma. The hypogastrium drains downward to the inguinal nodes, and the epigastrium drains upward to the axillary nodes. Thin lymphatic vessels connect these two territories at the umbilicus. Although a section of these thin vessels has no effect, a section of lymphatic trunks at the inguinal level, between Scarpa’s fascia and the muscle aponeurosis, may induce lymphatic leakage due to this low-pressure system. This accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the dissection plane is caused by dissection of large lymphatic trunks that drain the inguinal or axillary areas.

Other serious complications are effusion and hematoma, which may be avoided with precise coagulation, limited undermining, and closing of all the dead spaces as the body naturally tends to fill them up. Therefore, three rules (preserve the lymphatic trunks, limit undermining, and close all the dead spaces) reinforce one another and must be used simultaneously.

Paraumbilical High-Tension Sutures

Another anatomic point concerns the safety of the vasculature of the supraumbilical skin on which the high-tension suture and two paraumbilical sutures are placed. There is no risk of skin necrosis because the epigastric tunnel dissection preserves the intercostal blood supply. High-superior-tension abdominoplasty places maximum tension on the paraumbilical area, where vascularization is good, rather than on the suprapubic area, where vascularization is poor, as in standard abdominoplasty. We believe this is the best way to avoid skin necrosis and elevation of the suprapubic scar.

Surgical Technique

Patients are asked to wear a pair of their favorite underwear to determine the final lateral position of the scar. All demarcations are made while the patient is standing. The suprapubic horizontal mark usually is located 6 to 8 cm above the upper end of the vulvar cleft.

The abdominal region is infiltrated with 20 ml of ropivacaine hydrochloride and 1 mg of epinephrine per 1 l of saline. The dermis at the incision level also is infiltrated to reduce bleeding and the need for cauterization.

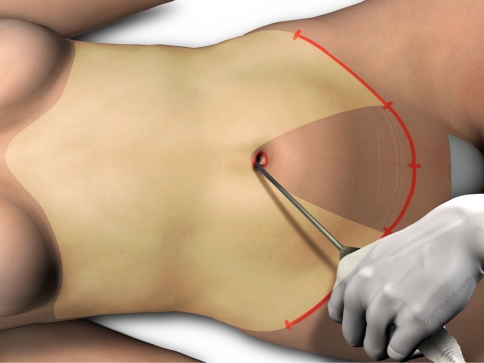

Hypogastric Liposuction

Liposuction is deep in the hypogastrium (Fig. 1), only beneath the superficialis fascia and mainly in the large trunks area, below Scarpa’s fascia. The goal is to remove fat volume without damaging the lymphatic network. Vessels are left intact through the gentle use of a 4-mm cannula, which transforms the fat layer into a thin fibrous spiderweb in which the normal physiology is left intact. Because the superficial layer is removed when the lower margin of the flap is excised, there is no need to debulk at this level.

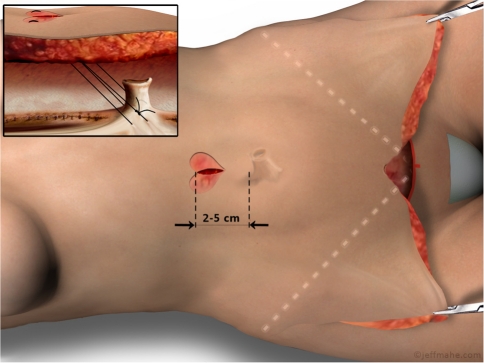

Fig. 1.

Liposuction is performed deep and laterally in the hypogastrium and deep and superficially in the epigastrium. No liposuction is performed below the umbilicus in the hypogastrium. This area is resected, and the lymphatic trunks are lateral

Epigastric Liposuction

Liposuction from the inframammary fold to the umbilicus is both deep and superficial. The goals are to reduce volume and mobilize tissues downward. However, to preserve vascularization of the flap, wide undermining to the costal margin is not done.

Incision

The incision follows the previously determined markings, staying superficial to preserve the lymphatic trunks beneath Scarpa’s fascia. A heart-shaped periumbilical incision is made with a no. 23 blade, and a vertical incision from the umbilicus to the pubis is added to facilitate dissection.

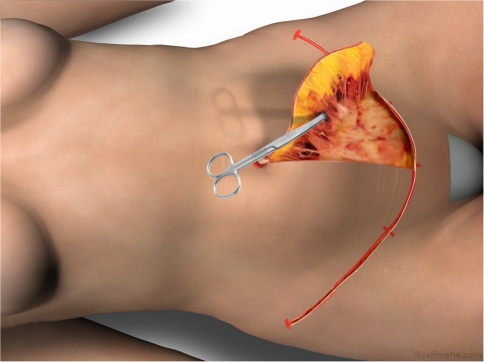

Undermining

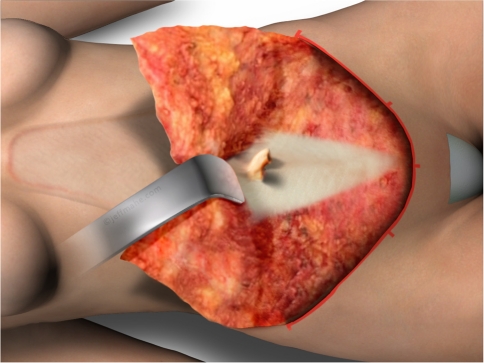

Dissection of the deep tissues is performed with electrocautery at a power sufficient to avoid blood loss and yet low enough to maintain tissue integrity. In the hypogastric area, the dissection enters the superficial part of the liposuctioned fibrous network just below the level of Scarpa’s fascia (Fig. 2). This dissection is avascular because the perforators are already divided. Immediately above the pubis, sectioning remains superficial to maintain a volume of fat and thereby avoid creation of a dead space after application of tension. Dissection of the tunnel is strictly preaponeurotic in the epigastric area and 10 cm wide as far as the xiphoid process allows the plication (Fig. 3). This level of dissection preserves the axillary lymphatic vessels that drain the upper abdominal flap.

Fig. 2.

Dissection in the iliac fossa performed at the upper part of the liposuctioned tissues, visible here on the scissors

Fig. 3.

Epigastric dissection staying deep on the muscular fascia to avoid damage to any part of the axillary lymphatic trunk

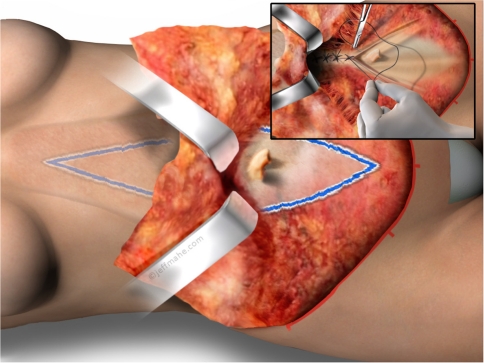

Parietal Repair

Aponeurotic plication with no. 2 Vicryl sutures in an interrupted figure eight pattern extends from the suprapubic area to the xiphoid process, involving only the aponeurosis without muscle fibers (Fig. 4). An 8- to 12-cm plication is possible. To join both sides of the aponeurosis, maximum horizontal tension is required. The maximum effect is achieved between the lowest costal margin and the iliac crest (i.e., at waist level). The concave shape at the level of the waist and the flatness at the level of the iliac crest form a new muscular foundation over which the skin will be tightened.

Fig. 4.

Aponeurotic plication at the maximum point between the lowest costal arch and the iliac crest. This major plication results in an aesthetically pleasing abdominal shape

As a result of this major aponeurotic plication, the umbilical stalk is invaginated. To repair this defect, two Vicryl 2-0 sutures are placed at 3 and 9 o’clock between the base of the umbilical stalk and the side of the plicated aponeurosis, causing the umbilicus to emerge 1 cm.

Positioning the New Umbilicus

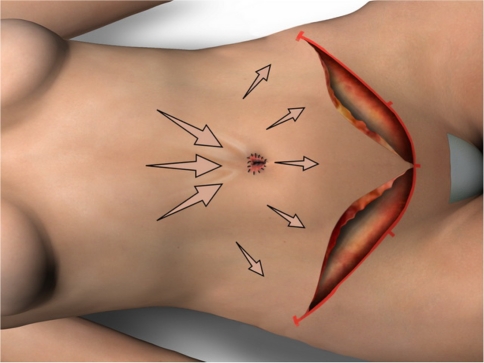

One of the keys to this operation is positioning the new umbilical site (Fig. 5). The operating table is flexed 30º to 40°. One or two high-tension sutures are placed in the upper tunnel on the midline to help move more epigastric skin downward and to quilt the epigastric dead space. The lower edge of the flap then is sutured to the pubis.

Fig. 5.

Heart-shaped deepithelialization performed to minimize the artificial appearance of the standard circular umbilicus. If two high-tension sutures are used on the midline in the epigastric area to lower the flap, the new umbilicus may be as close as 1 cm on a thin patient. Vicryl 2-0 sutures are placed, biting the upper half of the deepithelialization to leave the lower half with less tension, allowing the umbilical stalk to emerge more safely. Some fatty tissue is left along the umbilical stalk to ensure its vascularization

We use two rules to determine the site of the new umbilicus: (1) The site must be located 2 to 5 cm higher than the projection of the umbilicus stalk on the skin. This gap between the new umbilicus and the umbilical stalk allows the high superior tension. (2) The site must be located at least 11 cm above the pubic incision. The design of the new umbilicus is characterized by heart-shaped deepithelialization and a vertical transfixing incision to preserve the axial vessels and prevent necrosis of the area below.

Paraumbilical Sutures

The central point at the suprapubic level is cut, and the dermis of the new umbilicus is anchored to the aponeurosis lateral to the umbilical stalk with two Vicryl 2-0 sutures positioned at 3 and 9 o’clock. This technique has many advantages (Fig. 6), including

Improved tightening of the epigastric skin, avoiding otherwise permanent bulging

Decreased tension on the hypogastrium, with much lower risk of suprapubic necrosis

Absence of elevation and hypertrophy of the suprapubic scar

Increased distance between the umbilicus and the pubis, the opposite of what frequently is achieved using standard abdominoplasty, with lowering of the umbilicus and elevation of the pubic hairline

Epigastric tension load and major muscle sheet plication that allows excision of more skin. Consequently, the need for a miniabdominoplasty is rare, and quite frequently, the entire umbilicus-to-pubis skin can be removed. Nevertheless, the epigastrium pinch test must show at least 8 cm of excess skin. This technique of abdominoplasty usually allows closure without any vertical scarring because the excess skin is transferred to the hypogastrium.

Fig. 6.

High tension is applied in the epigastrium, medium tension in the hypogastrium, and nearly no tension on the lowest part of the abdominal flap. The risk of suprapubic necrosis is dramatically decreased, and the scar is not elevated

Traction Sutures

In the hypogastrium, the abdominal flap is sutured to the muscle fascia with moderate downward traction. Three staged traction sutures are placed on the midline to progressively advance the lower edge of the flap caudally and to minimize pubis elevation. Four traction sutures are placed in each iliac fossa, and three quilting sutures (meaning no vertical traction) are placed beneath each side of the scar. All dead spaces are obliterated.

Cutaneous Excision

Cutaneous excision is performed to achieve adequate tension and good symmetry of the scar position.

Suturing Technique

Over the past 2 years, our suturing technique has evolved into a distinctly different technique than what is traditionally performed. Our main goal is to eliminate trauma to the dermis. To achieve this, we follow two rules: (1) We do not cauterize the dermis during suturing, which is why we inject epinephrine before cutting. (2) We do not place knots in the dermis because every loop with a knot leads to necrosis of a small piece of dermis. The consequence is a high rate of external knots that may lead to infection, red spots at both sides of the scar resembling knots in the skin, local suture breaks, inflammation, and scarring.

In addition, subcuticular running sutures are a frequent cause of inflammation because of their very superficial location regardless of the type of suture material used [30]. Therefore, we propose a different way of suturing.

At the level of Scarpa’s fascia, we use standard interrupted no. 2 Vicryl sutures, engaging a substantial piece of fibrotic tissue and fat. The limited necrosis due to the knots at this level is negligible. We then use a running spiral suture at the superficial level rather than the two levels of suture used previously, namely, the dermal interrupted and subcuticular intradermal running sutures. The spiral sutures serve to join the subdermal fat to the dermis, as close as possible to the epidermis.

This technique dramatically changes the outcome of the healing process. Inflammation is diminished because the amount of suture in contact with the epidermis is reduced. Moreover, we have found the closure to be twice as fast and three times less expensive, and scar resolution to be much quicker.

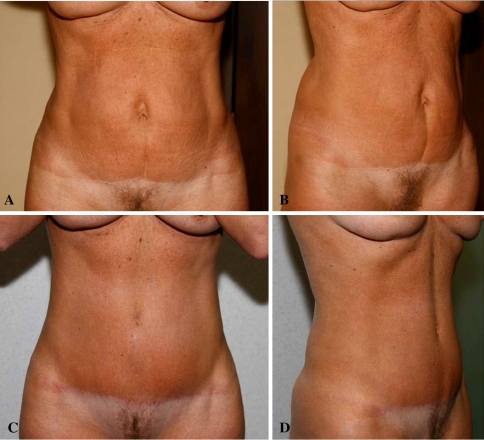

Case Reports

Our technique is illustrated by three cases: a standard case involving a woman who had given birth to two children (Fig. 7), a secondary case of a patient who had undergone a previous abdominoplasty (Fig. 8), and the case of a patient who had lost a great deal of weight because of gastric banding (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7.

a, b Preoperative aspect of a 45-year-old-patient who had two children. She had an excess of fat and skin and a stretched abdominal wall. c, d Postoperative aspect at 8 months showing a low suprapubic scar and a well-positioned umbilicus. The abdominal contour is improved

Fig. 8.

a, b Preoperative views of a 54-year-old patient with a previous abdominoplasty. The epigastric skin is not sufficiently tightened, and the distance from the umbilicus to the pubis has been shortened. c, d Postoperative views at 5 months. Using high-superior-tension abdominoplasty, the skin from the umbilicus to the pubis was resected and the suprapubic scar lowered. The umbilicus-to-pubis distance was lengthened and the waistline thinned

Fig. 9.

a, b Preoperative aspect of a 31-year-old patient who lost 40 kg from gastric banding surgery. c, d Results 6 months postoperatively. Body lifting removed 2.5 kg of tissue, and a 23-cm area above the pubic area was resected. High-superior-tension abdominoplasty was used to rebuild a central fold above the umbilicus, and the umbilicus-to-pubis distance was restored to its youthful appearance

Points for Further Discussion

In 1980, Guerrerosantos et al. [31] described a technique that avoids damage to the tissues of the inguinal area, although the goal is not to preserve the lymphatic trunks. According to the authors, this technique leaves a 2- to 3-cm fat layer attached to the skin, similar to that resulting from undermining in rhytidoplasty, which is very superficial for an abdominal dissection. Their main reasons for such a superficial plane are to prevent cutaneous anesthesia or paresthesia; to preserve the ilioinguinal nerve, the cutaneous branch of the obturator, and the anterior femoral cutaneous nerves; and to avoid residual lymphoedema from damaged vessels and lymphatics. They also believe this undermining prevents folding of the abdominal region caused by attaching a thick abdominal flap to nondetached skin on the upper thigh.

In their article, Guerrerosantos et al. [31] do not use the word “seroma,” but rather “residual lymphoedema from damaged vessels and lymphatics,” which is not the same thing. Lymphoedema induces swelling of the inferior border of the abdominal flap due to a decrease in drainage of the vessels and lymphatics. Seroma is a large and frequently long-lasting pocket of serous fluid due to a lymphatic trunk section. The authors summarize their technique as follows: “Problem: cutaneous anesthesia or paresthesia. Solution: superficial inguinal incision and superficial undermining in the lower lateral abdomen and upper thigh” [31]. They make no connection between this very superficial dissection plane and the prevention of seroma, which was the most frequent complication of abdominoplasty when their paper was published. After analyzing this interesting publication, one might conclude that a surgical technique that does not use the same plane of dissection or have the same goal as another surgical technique cannot reasonably be considered a precursor in any surgical field.

In a discussion about abdominoplasty, Uebel [28] wrote that the epigastric tunnel dissection was described by Sinder [29] in 1975. However, we could not find any mention of the tunnel dissection in this work. Tunnel dissection is logical only if it is combined with full epigastric liposuction, which leads to adequate release of tissues and allows lowering. However, liposuction was described later [2], which is why reports on tunnel dissection did not appear until Lockwood’s [32] article in 1996 and the senior author’s review [17] a few months later. In fact, Lockwood was enlarging his tunnel with scissors and a special cannula.

Quilting sutures were first described by Baroudi and Ferreira [24], also in 1996. This is a key point in surgery: closure of the dead space minimizes effusion and extension of hematoma. Nevertheless, the best way to prevent seroma due to cutting through a lymphatic trunk is to avoid this dissection.

As mentioned earlier, Pollock and Pollock [26] reported on their use of progressive tension sutures, but the moderate tension used to avoid creating dimples could not take advantage of high epigastric tension to decrease the overly high hypogastric tension. Moreover, no suture near the umbilicus was proposed.

One criticism of HSTA is the bent position patients must maintain during the first 10 days after surgery. However, this posture is necessary to allow the skin to stretch, and patients should be informed of this before agreeing to the surgery.

Conclusions

High-superior-tension abdominoplasty dramatically decreases or eliminates most complications of abdominoplasty and achieves more aesthetic results. This procedure is used in standard cases, for patients with massive weight loss, and for patients with very limited epigastric skin excess. For patients with massive weight loss, the risk of complications is greater, and those with very limited skin excess have low tolerance for even minor complications. However, in both instances, HSTA provides reliable and natural results.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Claude Le Louarn, Email: lelouarnclaude@orange.fr.

Jean Francois Pascal, Email: Jfpascal@wanadoo.fr.

References

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2010) 2010 report of the 2009 statistics. National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Statistics. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/Media/statistics/2009-US-cosmeticreconstructiveplasticsurgeryminimally-invasive-statistics.pdf. Accessed May 2010

- 2.Illouz YG (1980) A new technique for the localized lipodystrophies. Es Ver Chir Esth France 6

- 3.Demars and Marx: In: Voloir P (ed) (1960) Opérations Plastiques Aus-aponévrotiques sur la Paroi Abdominale Anterieure, vol 1. Thèse, Paris, p 25

- 4.Kelly HA. Report of gynecological cases. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1899;10:197. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudet F, Morestin H (1905) French congress of surgeons, vol 82. Paris, p 125

- 6.Weinhold S. Bauchdeckenplastik. Zentralbl F Gynak. 1909;38:1332. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morestin A (1911) La Restauration de la Paroi Abdominale Par Resection Entendue des Teguments et de la Graisse Souscutanee et le Plissement des Aponeuroses Superficielles Envisage Comme Complement de la Cure Radicale des Hernies Ombilicales, vol 15. These, Paris, p 18

- 8.Callia WEP (1965) Contribuiçào Para o Estudo da Correçào Cirurgica do Abdomen Pêndulo e Globoso: Técnica Original. Tese de Doutoramento Apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina da USP, Sao Paulo, Brazil

- 9.Pitanguy I. Abdominal lipectomy: an approach to it through analysis of 300 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40:384. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196710000-00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Illouz YG. Body contouring by lipolysis: A 5-year experience with over 3,000 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:591. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rangaswamy M. Lipoabdominoplasty: a versatile and safe technique for abdominal contouring. Indian J Plast Surg. 2008;41(Suppl):S48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso de Castro C, Cupello AM, Cintra H. Limited incisions in abdominoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;19:436. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillerud E. Abdominoplasty combined with suction lipoplasty. A study of complications, revisions, and risk factors in 487 cases. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:333. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ousterhout DK. Combined suction-assisted lipectomy, surgical lipectomy, and surgical abdominoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;24:126. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199002000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matarasso A. Liposuction as an adjunct to a full abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Louarn C. Partial subfascial abdominoplasty: Technical description based on thirty six cases (La plastie abdominale sous-fasciale partielle: Note technique à propos de trente-six cas) Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1992;37:547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Louarn C. Partial subfascial abdominoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20:123. doi: 10.1007/s002669900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Louarn C, Pascal JF. High-superior-tension abdominoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24:375. doi: 10.1007/s002660010061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Louarn C, Pascal JF, Levet Y, Searle A, Thion A. Abdominoplasty complications (in French) Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2004;49:601. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Louarn C, Pascal JF. High-superior-tension abdominoplasty: a safer technique. Aesthet Surg J. 2007;27:80. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castus P, Grandjean FX, Tourbach S, Heymans D. Sensibility of the abdomen after high-superior-tension abdominosplasty. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2009;54:545. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samra S, Sawh-Martinez R, Barry O, Persing JA. Complication rates of lipoabdominoplasty versus traditional abdominoplasty in high-risk patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:683. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c82fb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockwood T. High-lateral-tension abdominoplasty with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:603. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199509000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Contouring the hip and the abdomen. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18:439. doi: 10.1016/S1090-820X(98)70073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollock H, Pollock T. Progressive tension sutures: a technique to reduce local complications in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2583. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saldanha OR, De Souza Pinto EB, Mattos WN, Jr, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty with selective and safe undermining. Aesth Plast Surg. 2003;27:322. doi: 10.1007/s00266-003-3016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uebel C. Lipoabdominoplasty: revisiting the superior pull-down abdominal flap and new approaches. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009;33:3666. doi: 10.1007/s00266-009-9318-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinder R (1975) Abdominal plastic surgery: a personal technique. In: Sixth international congress of plastic and reconstructive surgery, vol 7. Paris, p 423

- 30.Holzheimer RG. Adverse events of sutures: possible interactions of biomaterials? Eur J Res. 2005;10:521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerrerosantos J, Spaillat L, Morales F, Dicksheet S. Some problems and solutions in abdominoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1980;4:227. doi: 10.1007/BF01575222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockwood T. The role of excisional lifting in body contour surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]