Abstract

Background and objectives: Lower rates of living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) among transplant candidates who are black or older may stem from lower likelihoods of (1) recruiting potential living donors or (2) potential donors actually donating (donor “conversion”).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A single-center, retrospective cohort study was performed to determine race, age, and gender differences in LDKT, donor recruitment, and donor conversion.

Results: Of 1617 kidney transplant candidates, 791 (48.9%) recruited at least one potential living donor, and 452 (28.0%) received LDKTs. Black transplant candidates, versus non-blacks, were less likely to receive LDKTs (20.5% versus 30.6%, relative risk [RR] = 0.67), recruit potential living donors (43.9% versus 50.7%, RR = 0.86), and receive LDKTs if they had potential donors (46.8% versus 60.3%, RR = 0.78). Transplant candidates ≥60 years, versus candidates 18 to <40 years old, were less likely to receive LDKTs (15.1% versus 43.2%, RR = 0.35), recruit potential living donors (34.0% versus 64.6%, RR = 0.53), and receive LDKTs if they had potential donors (44.5% versus 66.8%, RR = 0.67). LDKT and donor recruitment did not differ by gender. Race and age differences persisted in multivariable logistic regression models. Among 339 candidates who recruited potential donors but did not receive LDKTs, blacks (versus non-blacks) were more likely to have potential donors who failed to donate because of a donor-related reason (86.9% versus 72.5%).

Conclusions: Black or older kidney transplant candidates were less likely to receive LDKTs because of lower likelihoods of donor recruitment and donor conversion.

Living donor kidney transplant (LDKT) is usually the best treatment option for kidney failure (1) but occurs less frequently among persons who are black or older (2–4). In 2007, blacks comprised only 13.8% of LDKT recipients in the United States—a percentage that has remained unchanged for 10 years (1). In contrast, blacks make up 30% to 40% of the dialysis population (5), active deceased donor kidney transplant (DDKT) waiting list, and DDKT recipients (1). LDKTs also occur less frequently among older patients (2–4), whose anticipated waiting time for a DDKT often exceeds their life expectancy (6). In addition, several studies have reported decreased access to LDKTs among women (4,7–9), although other studies have found no gender differences (2,3).

Kidney transplant candidates who are black or older may receive fewer LDKTs because of barriers at two steps in the LDKT process. First, black or older candidates may be less likely to “recruit” potential living donors (10). Second, black or older candidates may be less likely to “convert” their potential donors into actual donors. Better knowledge of the relative importance of these two steps would enable targeted interventions to increase rates of LDKT.

Unfortunately, the relative importance of donor recruitment and donor “conversion” as barriers to LDKT remains unclear. Examination of these two steps requires a cohort of transplant candidates and recipients linked with their potential and actual living donors. One smaller study examined transplant candidates with their potential living donors and found that older age, but not race or gender, was associated with a lower likelihood of donor recruitment (3). Further studies are needed to determine whether donor recruitment impedes LDKT among certain subgroups.

Studies are also needed to determine whether donor conversion serves as a barrier to LDKT. Obesity and possibly hypertension exclude a higher proportion of black, versus non-black, potential donors (11–13), reflecting the higher prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension among blacks in general (14,15). However, the lower likelihood of donation by black potential donors does not necessarily demonstrate that the donor conversion step prevents LDKT among black transplant candidates. After all, transplant candidates whose initial potential donors fail to donate may later receive LDKTs from subsequent donors. Without information about the transplant candidates, prior studies of potential living donors (11–13) have been unable to fully characterize the donor conversion step.

Among kidney transplant candidates, we sought to determine (1) the barriers to receipt of LDKTs and (2) race, age, and gender differences in these barriers. We hypothesized that blacks were less likely than non-blacks to receive LDKTs because of a lower likelihood of donor recruitment and donor conversion.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

We performed a retrospective cohort study of adults evaluated for a kidney-alone transplant at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, New Jersey. We included persons who were ≥18 years old; evaluated between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2005; and deemed medically suitable for transplant. We excluded persons previously evaluated for kidney transplant, persons already listed for DDKT at another center, and recipients of prior kidney transplants. Study patients were followed until they died; were removed from our waiting list; transferred to another transplant center; received a LDKT; received a DDKT; or December 31, 2007, whichever came first.

The study protocol was approved by the human subjects Institutional Review Board at Saint Barnabas Medical Center.

Study Outcomes

Our main outcomes were (1) recruitment of potential living kidney donors, (2) receipt of LDKTs among all candidates, and (3) receipt of LDKTs among candidates who recruited potential donors (donor conversion).

Recruitment of a potential living donor occurred if a person contacted our center to express interest in donating to a specific transplant candidate and then appeared for education and evaluation (2000 to 2004) or completed the living donor referral form over the phone or via mail (2004 to 2007). Transplant candidates stop recruiting donors if an earlier donor actually donates, so the number of recruited, potential living donors may be misleading. Instead, we categorized donor recruitment dichotomously (any potential living donors versus none).

Receipt of a LDKT occurred only after the transplant candidate's potential donor successfully completed the living donor evaluation (16–18). Regarding criteria that may vary between centers, we excluded persons from living kidney donation for repeated creatinine clearance <80 ml/min per 1.73 m2; repeated proteinuria >300 mg/d; age >75 years or <18 years; diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose (glucose >100 mg/dl), or abnormal oral glucose tolerance test; and body mass index >35. We excluded persons with high blood pressure (BP), defined as use of any antihypertensive medications or BP >135/85 during the physician evaluation (usually confirmed by 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring). Donor nephrectomies were performed laparoscopically, with <0.5% requiring open donor nephrectomy.

Kidneys from live nondirected (i.e., altruistic) donors were transplanted into the next suitable candidates on the DDKT waiting list. We reclassified the six recipients of kidney transplants from live nondirected donors as recipients of DDKTs because these transplant candidates did not recruit their living donors.

Study Variables

Transplant candidates' demographic and medical data were abstracted from their medical records. The transplant candidate's zip code at the time of evaluation was linked to median household income for that zip code tabulation area, according to the 2000 U.S. Census Bureau.

Among potential living donors to transplant candidates who did not receive LDKTs, we determined the reasons for nondonation. The number of potential donors who were unable to donate for a given reason can be misleading, so we determined the number of transplant candidates who could not receive a LDKT because of each reason. For example, ten potential donors who could not donate because of blood group incompatibility may have intended to donate to only seven transplant candidates (several donors were recruited by the same candidate). Blood group incompatibility would be the reason for nondonation in ten donors but prevent LDKTs in only seven candidates. The transplant candidate, not the potential living donor, was the unit of all analyses, except where indicated.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using Stata software, version 9.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Categorical variables were expressed as proportions, and their values across groups (e.g., race) were compared using χ2 testing. Continuous variables were expressed as medians (with 25% to 75% interquartile ranges) and compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Our outcomes were common, so we calculated relative risks (RRs) and odds ratios.

We used logistic regression to model associations between covariates and our three outcomes (19). Candidate variables with P < 0.20 in the unadjusted analyses were eligible for the multivariable model. The multivariable model for each outcome was generated using a stepwise, backward elimination method. The significance of each variable in the nested models was assessed using the likelihood ratio test and the Wald statistic. Variables with adjusted P < 0.10 were retained in the final model. Goodness-of-fit was confirmed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test with ten deciles of risk.

We also used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate associations with time until LDKT and recruitment of the first potential living donor, calculated from the dates of initial evaluation and medical suitability for transplant. Given the similarity of the hazard and odds ratios, we present only the results of the logistic regression models.

Results

Study Cohort

The baseline characteristics of the 1617 kidney transplant candidates in our study differed according to race (Table 1) as well as sex and age. Compared with younger candidates, older transplant candidates were more likely to have Medicare as primary insurance (P < 0.001) and reside in a higher income zip code (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 1617 kidney transplant candidates

| Characteristic | Non-Black | Black | P | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1193 (73.8%) | 424 (26.2%) | 1617 | |

| Male | 749 (62.8%) | 242 (57.1%) | 0.04 | 991 (61.3%) |

| Age at evaluation | <0.001 | |||

| 18 to <40 years | 230 (19.3%) | 129 (30.4%) | 359 (22.2%) | |

| 40 to <50 years | 260 (21.8%) | 97 (22.9%) | 357 (22.1%) | |

| 50 to <60 years | 340 (28.5%) | 105 (24.8%) | 445 (27.5%) | |

| ≥60 years | 363 (30.4%) | 93 (21.9%) | 456 (28.2%) | |

| Age at evaluation, median (25% to 75%), in years | 53.4 (42.8 to 61.8) | 48.5 (38.3 to 58.9) | <0.001 | 52.5 (41.2 to 61.2) |

| Etiology of renal disease | <0.001 | |||

| diabetes | 478 (40.1%) | 136 (32.1%) | 614 (38.0%) | |

| hypertension | 155 (13.0%) | 146 (34.4%) | 301 (18.6%) | |

| cystic | 114 (9.6%) | 12 (2.8%) | 126 (7.8%) | |

| glomerulonephritis | 278 (23.3%) | 89 (21.0%) | 367 (22.7%) | |

| interstitial | 30 (2.5%) | 7 (1.7%) | 37 (2.3%) | |

| obstruction | 30 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (1.9%) | |

| unknown | 48 (4.0%) | 19 (4.5%) | 67 (4.1%) | |

| Married | 766 (64.2%) | 190 (44.8%) | <0.001 | 956 (59.1%) |

| Dialysis status | <0.001 | |||

| not on dialysis | 246 (20.6%) | 38 (9.0%) | 284 (17.6%) | |

| hemodialysis | 819 (68.7%) | 361 (85.1%) | 1180 (73.0%) | |

| peritoneal dialysis | 128 (10.7%) | 25 (5.9%) | 153 (9.5%) | |

| Medical insurance | 0.07 | |||

| private | 703 (58.9%) | 225 (53.1%) | 928 (57.4%) | |

| Medicare | 429 (36.0%) | 169 (40.0%) | 598 (37.0%) | |

| Medicaid and other public insurance | 61 (5.1%) | 30 (7.1%) | 91 (5.6%) | |

| Highest education level | <0.001 | |||

| up to high school diploma | 571 (47.9%) | 193 (45.5%) | 764 (47.3%) | |

| any college or technical school | 276 (23.1%) | 134 (31.6%) | 410 (25.4%) | |

| associate, bachelor, or higher degree | 296 (24.8%) | 68 (16.0%) | 364 (22.5%) | |

| unknown | 50 (4.2%) | 29 (6.8%) | 79 (4.9%) | |

| Median household income of zip code, in U.S. dollars | ||||

| median (25% to 75%) | $59,611 (43,850 to 72,839) | $41,566 (33,418 to 57,479) | <0.0001 | $53,375 (38,733 to 68,709) |

| median income of each quartile | <0.001 | |||

| quartile 1 | $32,569 (17.8%) | $31,269 (45.5%) | $31,949 (25.1%) | |

| quartile 2 | $46,646 (24.4%) | $47,308 (26.9%) | $46,833 (25.1%) | |

| quartile 3 | $61,433 (28.3%) | $60,748 (15.6%) | $61,321 (24.9%) | |

| quartile 4 | $87,121 (29.6%) | $79,438 (12.0%) | $86,151 (25.0%) | |

| Initial panel reactive antibody | 0.07 | |||

| 0% | 715 (59.9%) | 225 (53.1%) | 940 (58.1%) | |

| 1% to 19% | 27 (2.3%) | 14 (3.3%) | 41 (2.5%) | |

| 20% to 79% | 39 (3.3%) | 20 (4.7%) | 59 (3.7%) | |

| ≥80% | 29 (2.4%) | 9 (2.1%) | 38 (2.4%) | |

| missing | 383 (32.1%) | 156 (36.8%) | 539 (33.3%) | |

| ABO blood type | <0.001 | |||

| O | 543 (45.5%) | 229 (54.0%) | 772 (47.7%) | |

| A | 390 (32.7%) | 93 (21.9%) | 483 (29.9%) | |

| B | 184 (15.4%) | 81 (19.1%) | 265 (16.4%) | |

| AB | 76 (6.4%) | 21 (5.0%) | 97 (6.0%) |

Recruitment of Potential Living Donors and Receipt of LDKTs

Transplant candidates were followed for a median of 2.5 years after evaluation (25% to 75% range, 1.1 to 3.8 years). Overall, 791 (48.9%) kidney transplant candidates recruited at least one potential living donor (1194 total potential donors). By the end of follow-up, 452 transplant candidates received LDKTs, corresponding to 28.0% of the entire cohort and 57.1% of the candidates who recruited potential living donors.

Transplant candidates who were black or older were significantly less likely to receive LDKTs (Table 2). Compared with non-blacks, black transplant candidates were one third less likely to receive LDKTs. Compared with candidates <40 years old, candidates in older age categories were less likely to receive LDKTs (P < 0.001). Among the 96 candidates who were ≥70 years, the RR of receiving a LDKT was especially low (RR = 0.19, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.10 to 0.38, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Counts and unadjusted RRs of receipt of LDKT according to race, gender, and age category of kidney transplant candidates

| Transplant Candidate Characteristic | Received a LDKT |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Race | |||

| non-black | 365 (30.6) | Reference | |

| black | 87 (20.5) | 0.67 (0.55 to 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| male | 285 (28.8) | Reference | |

| female | 167 (26.7) | 0.93 (0.79 to 1.09) | 0.36 |

| Age | |||

| 18 to <40 years | 155 (43.2) | Reference | |

| 40 to <50 years | 115 (32.2) | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.90) | 0.003 |

| 50 to <60 years | 113 (25.4) | 0.59 (0.48 to 0.72) | <0.001 |

| ≥60 years | 69 (15.1) | 0.35 (0.27 to 0.45) | <0.001 |

Transplant candidates who were black or older were significantly less likely to (1) recruit at least one potential living donor and (2) receive LDKTs if they had potential living donors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Counts and unadjusted RRs of recruitment of potential living donors (donor recruitment) and receipt of a LDKT among candidates who recruited potential living donors (donor conversion) according to race, gender, and age category

| Transplant Candidate Characteristic | Recruited One or More Potential Living Donors |

Received LDKT, among Candidates Who Recruited Potential Living Donors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | N (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Race | ||||||

| non-black | 605 (50.7) | Reference | 365 (60.3) | Reference | ||

| Black | 186 (43.9) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.98) | 0.015 | 87 (46.8) | 0.78 (0.66 to 0.92) | 0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| male | 475 (47.9) | Reference | 285 (60.0) | Reference | ||

| female | 316 (50.5) | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.17) | 0.32 | 167 (52.9) | 0.88 (0.78 to 1.00) | 0.047 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18 to <40 years | 232 (64.6) | Reference | 155 (66.8) | Reference | ||

| 40 to <50 years | 190 (53.2) | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.93) | 0.002 | 115 (60.5) | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.05) | 0.19 |

| 50 to <60 years | 214 (48.1) | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.84) | <0.001 | 113 (52.8) | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.92) | 0.003 |

| ≥60 years | 155 (34.0) | 0.53 (0.45 to 0.61) | <0.001 | 69 (44.5) | 0.67 (0.55 to 0.81) | <0.001 |

There were no gender differences in the likelihoods of receiving LDKTs and recruiting potential living donors (Tables 2 and 3).

At the end of follow-up, 279 (17.3%) transplant candidates had received DDKTs, 258 (16.0%) had died or been removed from the waiting list because of medical reasons, 433 (26.8%) remained on the waiting list, and 195 (12.1%) had transferred their waiting time or received transplants elsewhere. The proportion of patients who received DDKTs was similar across race (P = 0.78), gender (P = 0.89), and age categories (P = 0.07).

Univariable and Multivariable Models

In univariable models, black race and older age were associated with lower odds of receipt of a LDKT, recruitment of potential living donors (donor recruitment), and receipt of a LDKT if the candidate had potential living donors (donor conversion). Diabetes, not being married, requiring maintenance dialysis, having nonprivate insurance, lower median zip code income, panel reactive antibodies ≥ 20%, and recipient blood type O were associated with lower odds of receipt of a LDKT (data not shown).

In a multivariable model, black race (P = 0.001) and older age (P < 0.001) remained associated with lower odds of receiving a LDKT (Table 4). Among candidates who were black and ≥60 years old, the adjusted odds ratio for receipt of a LDKT was 0.13 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.21).

Table 4.

Multivariable models of factors associated with receipt of LDKT, recruitment of potential living donors, and receipt of a LDKT among candidates who recruited potential living donors

| Transplant Candidate Characteristic | Receipt of LDKT |

Recruitment of Potential Living Donor(s) |

Receipt of a LDKT, among Candidates Who Recruited Potential Living Donor(s) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Black race (versus non-black) | 0.61 (0.45 to 0.81) | 0.001 | 0.78 (0.62 to 1.00) | 0.047 | 0.57 (0.40 to 0.82) | 0.002 |

| Female (versus male) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.21) | 0.64 | 1.16 (0.93 to 1.44) | 0.18 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.07) | 0.12 |

| Age (versus 18 to <40 years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 40 to <50 years | 0.52 (0.37 to 0.72) | 0.52 (0.38 to 0.72) | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.97) | |||

| 50 to <60 years | 0.34 (0.25 to 0.47) | 0.40 (0.29 to 0.54) | 0.47 (0.31 to 0.71) | |||

| ≥60 years | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.30) | 0.23 (0.17 to 0.32) | 0.37 (0.24 to 0.58) | |||

| Married (versus not married) | 1.38 (1.06 to 1.81) | 0.02 | 1.69 (1.33 to 2.13) | <0.001 | NS | — |

| Not on dialysis (versus already on dialysis) | 2.52 (1.89 to 3.36) | <0.001 | 2.16 (1.62 to 2.87) | <0.001 | 2.21 (1.53 to 3.22) | <0.001 |

| Insurance status (versus private insurance) | <0.001 | 0.002 | NS | — | ||

| Medicare | 0.66 (0.50 to 0.87) | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.92) | ||||

| Medicaid | 0.41 (0.22 to 0.77) | 0.49 (0.31 to 0.80) | ||||

| Initial panel reactive antibody (versus <20%) | 0.001 | NS | — | <0.001 | ||

| 20% to 100% | 0.35 (0.18 to 0.69) | 0.29 (0.14 to 0.62) | ||||

| missing | 1.22 (0.95 to 1.56) | 1.34 (0.97 to 1.85) | ||||

| Blood type (versus type O) | 0.04 | NS | — | 0.07 | ||

| A | 1.47 (1.12 to 1.92) | 1.52 (1.07 to 2.14) | ||||

| B | 1.35 (0.97 to 1.89) | 1.52 (0.99 to 2.34) | ||||

| AB | 1.11 (0.67 to 1.84) | 1.23 (0.64 to 2.35) | ||||

NS, not significant.

In separate multivariable models, black race and older age remained associated with lower odds of (1) donor recruitment and (2) donor conversion (Table 4). Among transplant candidates who were black and ≥60 years old, the adjusted odds ratio for donor recruitment was 0.18 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.28), and the adjusted odds ratio for donor conversion was 0.21 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.38).

In multivariable models, female sex was not associated with receipt of a LDKT, donor recruitment, or donor conversion. There were no interactions between race and the following: sex, age category, medical insurance type, or median income of the transplant candidate's zip code. There were no interactions between sex and age category.

Candidates Who Recruited Potential Living Donors but Did Not Receive LDKTs

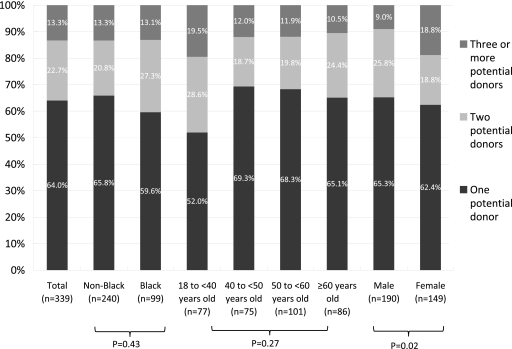

There were 339 transplant candidates who recruited at least one potential living donor (530 total donors) but did not receive LDKTs. Among these candidates, the number of recruited donors differed according to candidate gender (P = 0.02) but not according to candidate race (P = 0.43) or age category (P = 0.27) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of potential donors recruited by 339 transplant candidates who recruited donors but did not receive LDKTs, stratified by race, age, and gender of the transplant candidate.

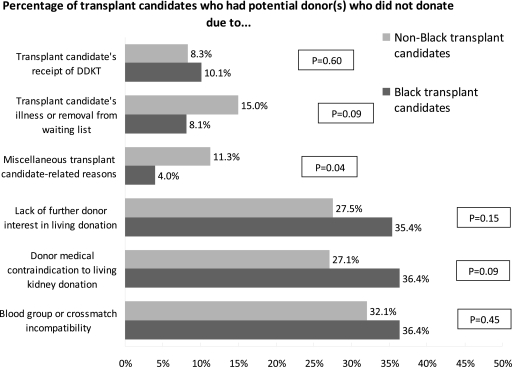

For 260 (76.7%) of these candidates, at least one potential donor did not donate because of one of the three donor-related reasons: blood group or crossmatch incompatibility (167 donors to 113 candidates), medical contraindication to donation (119 donors to 101 candidates), and lack of further donor interest in donation (117 donors to 101 candidates). More black (versus non-black) transplant candidates had at least one potential donor who failed to donate because of any of the three donor-related reasons (86.9% versus 72.5%, P = 0.004). However, racial differences in each of the three donor-related reasons were not statistically significant (Figure 2). Nondonation because of donor-related reasons was distributed evenly across transplant candidates' gender (P = 0.85) and age categories (P = 0.78).

Figure 2.

Transplant candidates who had potential living donors and did not receive LDKTs, categorized by reasons for nondonation and stratified by race of the transplant candidate.

For 103 (30.4%) of the 339 candidates, at least one potential donor did not donate because of one of the three recipient-related reasons: transplant candidate death or medical ineligibility for transplant (57 donors to 44 candidates), transplant candidate received a DDKT (37 donors to 30 candidates), and miscellaneous reasons (33 donors to 31 candidates). Nondonation because of recipient-related reasons was less common among black (versus non-black) candidates (22.2% versus 33.8%, P = 0.04) but was distributed evenly across transplant candidates' gender (P = 0.86) and age categories (P = 0.59).

Among these 530 potential donors to 339 transplant candidates who did not receive LDKTs, the specific reasons for nondonation are listed in Table 5. Among the 119 potential donors who had medical contraindications to donation, potential donors to black transplant candidates (versus to non-black candidates) were more likely to be excluded because of hypertension (43.6% versus 22.5%). However, overall the specific medical contraindications did not differ according to the race of the transplant candidate (P = 0.13) (Table 5). These 530 potential donors, versus the 452 actual living donors, were similar in age (median 40.9 versus 41.2 years old, P = 0.80) and sex (42.3% versus 37.2% male, P = 0.10) but more likely to be black (24.2% versus 16.4%, P = 0.003).

Table 5.

Reasons for nondonation by 530 potential living donors recruited by 339 transplant candidates who did not receive LDKTs

| Total Number of Potential Donors | Potential Donors to Non-Black Transplant Candidates | Potential Donors to Black Transplant Candidates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 530 | 376 | 154 |

| Donor-related reasons for nondonation | 403 | 276 | 127 |

| blood group and/or crossmatch incompatible | 167 (31.5%) | 120 (31.9%) | 47 (30.5%) |

| lack of further donor interest in donation | 117 (22.1%) | 76 (20.2%) | 41 (26.6%) |

| medical contraindication to kidney donation | 119 (22.5%) | 80 (21.3%) | 39 (25.3%) |

| hypertensiona | 35 (29.4%) | 18 (22.5%) | 17 (43.6%) |

| obesitya | 17 (14.3%) | 11 (13.8%) | 6 (15.4%) |

| diabetes mellitusa | 10 (8.4%) | 6 (7.5%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| low GFRa | 7 (5.9%) | 6 (7.5%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| proteinuriaa | 8 (6.7%) | 5 (6.3%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| hematuriaa | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| nephrolithiasisa | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| psychosociala | 10 (8.4%) | 7 (8.8%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| renal cystsa | 4 (3.4%) | 4 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| other anatomic (renal mass, vascular)a | 4 (3.4%) | 3 (3.8%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| hepatitis C or other hepatic abnormalitya | 7 (5.9%) | 3 (3.8%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| cardiaca | 6 (5.0%) | 6 (7.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| other medical contraindication (pulmonary, pregnancy, cancer, hypercoagulable state)a | 7 (5.9%) | 7 (8.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Recipient-related reasons for nondonation | 127 | 100 | 27 |

| transplant candidate death or medical ineligibility for transplant | 57 (10.8%) | 48 (12.8%) | 9 (5.8%) |

| transplant candidate received DDKT at our center | 37 (7.0%) | 24 (6.4%) | 13 (8.4%) |

| miscellaneous transplant candidate-related reasons | 33 (6.2%) | 28 (7.5%) | 5 (3.3%) |

| transplant candidate transferred time or transplanted elsewhereb | 15 (45.5%) | 12 (42.9%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| transplant candidate refused LDKTb | 13 (39.4%) | 12 (42.9%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| LDKT scheduled and pendingb | 5 (15.2%) | 4 (14.3%) | 1 (20.0%) |

The denominator for the calculation of these percentages is the number of potential donors who did not donate because of donor medical contraindications.

The denominator for the calculation of these percentages is the number of potential donors who did not donate because of miscellaneous transplant-candidate-related reasons.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of 1617 kidney transplant candidates, black or older transplant candidates had lower likelihoods of donor recruitment and donor conversion. Barriers at both of these steps in the LDKT process resulted in significantly lower likelihoods of LDKT in blacks (RR = 0.67, versus non-blacks) and in candidates ≥60 years (RR = 0.35, versus candidates 18 to <40 years old). These race- and age-based differences in LDKT, donor recruitment, and donor conversion persisted in multivariable models that adjusted for many potential confounders.

The lower likelihood of donor recruitment by black or older transplant candidates is potentially addressable. Educational and behavioral interventions can increase the proportion of transplant candidates who bring forth potential living donors (20–22). Such interventions have been especially effective among blacks (21,22).

To eliminate race- and age-based differences in LDKT, donor conversion by black or older transplant candidates also must improve. Otherwise, donor conversion may serve as the rate-limiting barrier to LDKT. Persistent differences in donor conversion would cause black or older transplant candidates to receive fewer LDKTs, even if differences in donor recruitment disappeared. Unfortunately, decreasing race- and age-based differences in donor conversion may prove to be difficult.

Many candidates did not receive LDKTs because their recruited donors had medical contraindications to living kidney donation. These medical contraindications are not easily amenable to interventions. Current medical criteria for living kidney donation are appropriately stringent given that donation has short-term (23,24) and possibly long-term (25,26) risks. Obesity, which occurs more commonly among black potential donors (11–13), has uncertain long-term risks for living donors (27,28). The medical criteria for accepting living donors should not be relaxed given the ethical imperative to protect the welfare of potential and actual donors (29).

Many candidates did not receive LDKTs because their recruited donors lacked further interest in living donation. Potential living donors who are black are more likely to be lost to follow-up and lose interest in living donation (12,13). Thus, efforts to decrease donor “dropout” may especially increase donor conversion and LDKT among black transplant candidates. However, transplant centers must tread carefully in any efforts to decrease living donor dropout. Potential donors should feel neither pressured nor coerced into donating given the risks (23,25,26) and voluntary nature (29) of living kidney donation.

Many transplant candidates did not receive LDKTs because they were blood group or crossmatch incompatible with their recruited donors. Desensitization and donor exchange programs now enable transplant candidates with immunologically incompatible living donors to receive LDKTs (30–32). However, in our study, incompatible potential donors occurred with equal frequency among black versus non-black candidates and among older versus younger candidates. Therefore, desensitization and donor exchange may increase overall rates of LDKT (33) but fail to reduce race- or age-based differences in LDKT rates (34). Future studies should determine the effect of desensitization and donor exchange (including chains and dominos that use nondirected donors) on demographic disparities in LDKT.

To examine the donor recruitment and conversion steps, we linked kidney transplant candidates with their potential, as well as actual, living donors. Prior studies could not examine these steps because they examined transplant candidates but lacked data on candidates' potential living donors (2,4,7), examined recipients of LDKTs but lacked data on candidates who did not receive LDKTs (2,7–9,35), or examined potential living donors but lacked data on donors' intended recipients (11–13,36). Several recent studies have reported reasons for nondonation by recruited, potential living donors (11–13,36). Although informative, these donor-based studies lacked information about donors' associated transplant candidates, preventing examination of donor recruitment and conversion. Compared with the steps in the DDKT process (37), the steps in the LDKT process remain poorly characterized (38).

Our study has important limitations. First, our results may not necessarily apply to other U.S. transplant centers. Other centers may select their transplant candidates and living donors using different criteria (39). Nevertheless, our results are likely generalizable. Demographically, our center's waiting list closely resembles the national waiting list. Furthermore, most centers evaluate and select their transplant candidates (40) and living donors (16,18) using similar, albeit not identical, criteria. In any case, studies of the barriers to LDKT are almost necessarily single-center studies because large registry data sets lack the granularity of information needed to examine donor recruitment and conversion.

Second, we did not collect and adjust for psychosocial and health services factors that may influence donor recruitment and conversion (3,41). These factors include poorly understood provider and system factors (42); candidates' self-efficacy, social support, and networks (43); and prior discussions of LDKT (44), timing of nephrology referral (45), and knowledge and attitudes regarding ESRD and LDKT (46). Future, prospective studies should collect and adjust for these factors to better determine the root causes of LDKT disparities (47). Subsequent interventions can then target these factors to increase rates of LDKT.

In conclusion, black or older kidney transplant candidates were less likely to receive LDKTs because of lower likelihoods of donor recruitment and donor conversion. These dual barriers to LDKT underscore the difficulty of increasing rates of LDKT in transplant candidates who are black or older. Decreasing race- and age-based differences in LDKT will require interventions to address both barriers in the LDKT process.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results were presented in part at the 2008 annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology; November 4 through 9, 2008; Philadelphia, PA, and at the American Transplant Congress; May 30 through June 3, 2009; Boston, MA. Dr. Reese is supported in part by grant K23-DK078688 from the National Institutes of Health and by a Junior Development Grant in Geriatric Nephrology sponsored jointly by the American Society of Nephrology, the Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation: 2008 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant data 1998-2007 Rockville, MD, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gore JL, Danovitch GM, Litwin MS, Pham PT, Singer JS: Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 9: 1124–1133, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reese PP, Shea JA, Bloom RD, Berns JS, Grossman R, Joffe M, Huverserian A, Feldman HI: Predictors of having a potential live donor: A prospective cohort study of kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant 9: 2792–2799, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Segev DL, Kucirka LM, Oberai PC, Parekh RS, Boulware LE, Powe NR, Montgomery RA: Age and comorbidities are effect modifiers of gender disparities in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 621–628, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2009 Annual data report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schold J, Srinivas TR, Sehgal AR, Meier-Kriesche HU: Half of kidney transplant candidates who are older than 60 years now placed on the waiting list will die before receiving a deceased-donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1239–1245, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bloembergen WE, Port FK, Mauger EA, Briggs JP, Leichtman AB: Gender discrepancies in living related renal transplant donors and recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1139–1144, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kayler LK, Meier-Kriesche HU, Punch JD, Campbell DA, Jr., Leichtman AB, Magee JC, Rudich SM, Arenas JD, Merion RM: Gender imbalance in living donor renal transplantation. Transplantation 73: 248–252, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kayler LK, Rasmussen CS, Dykstra DM, Ojo AO, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Merion RM: Gender imbalance and outcomes in living donor renal transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 3: 452–458, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tankersley M, Gaston RS, Curtis J, Julian B, Deierhoi M, Rhynes V, Zeigler S, Diethelm A: The living donor process in kidney transplantation: Influence of race and comorbidity. Transplant Proc 29: 3722–3723, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Norman SP, Song PX, Hu Y, Ojo AO: Transition from donor candidates to live kidney donors: The impact of race and undiagnosed medical disease states. Clin Transplant, 2009, Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reeves-Daniel A, Adams PL, Daniel K, Assimos D, Westcott C, Alcorn SG, Rogers J, Farney AC, Stratta RJ, Hartmann EL: Impact of race and gender on live kidney donation. Clin Transplant 23: 39–46, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lunsford SL, Simpson KS, Chavin KD, Menching KJ, Miles LG, Shilling LM, Smalls GR, Baliga PK: Racial disparities in living kidney donation: Is there a lack of willing donors or an excess of medically unsuitable candidates? Transplantation 82: 876–881, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, Saunders E: Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med 165: 2098–2104, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS: Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA 289: 76–79, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis CL, Delmonico FL: Living-donor kidney transplantation: A review of the current practices for the live donor. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2098–2110, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kasiske BL, Ravenscraft M, Ramos EL, Gaston RS, Bia MJ, Danovitch GM: The evaluation of living renal transplant donors: Clinical practice guidelines. Ad Hoc Clinical Practice Guidelines Subcommittee of the Patient Care and Education Committee of the American Society of Transplant Physicians. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2288–2313, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM, Johnson SR, Karp SJ, Khwaja K, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR: The medical evaluation of living kidney donors: A survey of US transplant centers. Am J Transplant 7: 2333–2343, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied logistic regression, 2nd ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Lin JK, Kaplan B, Howard RJ: Increasing live donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial of a home-based educational intervention. Am J Transplant 7: 394–401, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ: A randomized trial of a home-based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation: Effects in blacks and whites. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 663–670, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schweitzer EJ, Yoon S, Hart J, Anderson L, Barnes R, Evans D, Hartman K, Jaekels J, Johnson LB, Kuo PC, Hoehn-Saric E, Klassen DK, Weir MR, Bartlett ST: Increased living donor volunteer rates with a formal recipient family education program. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 739–745, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matas AJ, Bartlett ST, Leichtman AB, Delmonico FL: Morbidity and mortality after living kidney donation, 1999–2001: Survey of United States transplant centers. Am J Transplant 3: 830–834, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, Mehta SH, Singer AL, Taranto SE, McBride MA, Montgomery RA: Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA 303: 959–966, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boudville N, Prasad GV, Knoll G, Muirhead N, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Yang RC, Rosas-Arellano MP, Housawi A, Garg AX: Meta-analysis: Risk for hypertension in living kidney donors. Ann Intern Med 145: 185–196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garg AX, Muirhead N, Knoll G, Yang RC, Prasad GV, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Housawi A, Boudville N: Proteinuria and reduced kidney function in living kidney donors: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Kidney Int 70: 1801–1810, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tavakol MM, Vincenti FG, Assadi H, Frederick MJ, Tomlanovich SJ, Roberts JP, Posselt AM: Long-term renal function and cardiovascular disease risk in obese kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1230–1238, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Praga M, Hernandez E, Herrero JC, Morales E, Revilla Y, Diaz-Gonzalez R, Rodicio JL: Influence of obesity on the appearance of proteinuria and renal insufficiency after unilateral nephrectomy. Kidney Int 58: 2111–2118, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abecassis M, Adams M, Adams P, Arnold RM, Atkins CR, Barr ML, Bennett WM, Bia M, Briscoe DM, Burdick J, Corry RJ, Davis J, Delmonico FL, Gaston RS, Harmon W, Jacobs CL, Kahn J, Leichtman A, Miller C, Moss D, Newmann JM, Rosen LS, Siminoff L, Spital A, Starnes VA, Thomas C, Tyler LS, Williams L, Wright FH, Youngner S: Consensus statement on the live organ donor. JAMA 284: 2919–2926, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haririan A, Nogueira J, Kukuruga D, Schweitzer E, Hess J, Gurk-Turner C, Jacobs S, Drachenberg C, Bartlett S, Cooper M: Positive cross-match living donor kidney transplantation: Longer-term outcomes. Am J Transplant 9: 536–542, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Montgomery RA, Zachary AA, Ratner LE, Segev DL, Hiller JM, Houp J, Cooper M, Kavoussi L, Jarrett T, Burdick J, Maley WR, Melancon JK, Kozlowski T, Simpkins CE, Phillips M, Desai A, Collins V, Reeb B, Kraus E, Rabb H, Leffell MS, Warren DS: Clinical results from transplanting incompatible live kidney donor/recipient pairs using kidney paired donation. JAMA 294: 1655–1663, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Montgomery RA, Locke JE, King KE, Segev DL, Warren DS, Kraus ES, Cooper M, Simpkins CE, Singer AL, Stewart ZA, Melancon JK, Ratner L, Zachary AA, Haas M: ABO incompatible renal transplantation: A paradigm ready for broad implementation. Transplantation 87: 1246–1255, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roodnat JI, Kal-van Gestel JA, Zuidema W, van Noord MA, van de Wetering J, IJzermans JNM, Weimar W: Successful expansion of the living donor pool by alternative living donation programs. Am J Transplant 9: 2150–2156, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Segev DL, Kucirka LM, Gentry SE, Montgomery RA: Utilization and outcomes of kidney paired donation in the United States. Transplantation 86: 502–510, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zimmerman D, Donnelly S, Miller J, Stewart D, Albert SE: Gender disparity in living renal transplant donation. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 534–540, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tuohy KA, Johnson S, Khwaja K, Pavlakis M: Gender disparities in the live kidney donor evaluation process. Transplantation 82: 1402–1407, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280: 1148–1152, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gill JS, Johnston O: Access to kidney transplantation: The limitations of our current understanding. J Nephrol 20: 501–506, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reese PP, Feldman HI, McBride MA, Anderson K, Asch DA, Bloom RD: Substantial variation in the acceptance of medically complex live kidney donors across US renal transplant centers. Am J Transplant 8: 2062–2070, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kasiske BL, Cangro CB, Hariharan S, Hricik DE, Kerman RH, Roth D, Rush DN, Vazquez MA, Weir MR: The evaluation of renal transplantation candidates: Clinical practice guidelines. Am J Transplant 1[Suppl 2]: 1–95, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waterman AD, Rodrigue JR, Purnell TS, Ladin K, Boulware LE: Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: Priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol 30: 90–98, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Powe NR: Let's get serious about racial and ethnic disparities. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1271–1275, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ladin K, Hanto DW: Understanding disparities in transplantation: Do social networks provide the missing clue? Am J Transplant 10: 472–476, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boulware LE, Meoni LA, Fink NE, Parekh RS, Kao WH, Klag MJ, Powe NR: Preferences, knowledge, communication and patient-physician discussion of living kidney transplantation in African American families. Am J Transplant 5: 1503–1512, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Winkelmayer WC, Mehta J, Chandraker A, Owen WF, Jr, Avorn J: Predialysis nephrologist care and access to kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 7: 872–879, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL: Optimal transplant education for recipients to increase pursuit of living donation. Prog Transplant 18: 55–62, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Powe NR, Boulware LE: The uneven distribution of kidney transplants: Getting at the root causes and improving care. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 861–863, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]