Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore the influence of unit characteristics, staff characteristics and teamwork on job satisfaction with current position and occupation.

Background

Teamwork has been associated with a higher level of job satisfaction but few studies have focused on the acute care inpatient hospital nursing team.

Methods

This was a cross sectional study with a sample of 3,675 nursing staff from five hospitals and 80 patient care units. Participants completed the Nursing Teamwork Survey.

Results

Participants’ levels of job satisfaction with current position and satisfaction with occupation were both higher when they rated their teamwork higher (p < 0.001) and perceived their staffing as adequate more often (p < 0.001). Type of unit influenced both satisfaction variables (p < 0.05). Additionally, education, gender and job title influenced satisfaction with occupation (p < 0.05) but not with current position.

Conclusions

Results of this study demonstrate that within nursing teams on acute care patient units, a higher level of teamwork and perceptions of adequate staffing leads to greater job satisfaction with current position and occupation.

Implications for Nursing Management

Findings suggest that efforts to improve teamwork and ensure adequate staffing in acute care settings would have a major impact on staff satisfaction.

Keywords: nursing teamwork, job satisfaction, nurse staffing, registered nurse, nursing assistant

Nursing shortages are one of the vexing problems in healthcare. As the demand continues to rise, the current supply is unable to meet society’s needs. This is a world wide phenomenon. In the United States, according to the latest projections from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), more than one million new and replacement nurses will be needed by 2016 (BLS 2009). Additionally, more than 587,000 new nursing positions will be created (a 23.5% increase). Consequently, it is expected that nursing will be the nation’s top profession in terms of projected job growth (BLS 2009). Adding to this problem is that registered nurses (RNs) continue to leave their current positions and the profession at a high rate. It has been reported that up to 13% of new nurses consider leaving their jobs within one year (Kovner et al. 2007). Job dissatisfaction is reported to be strongly associated with nurse turnover (Hayes et al. 2006) and intent to leave (Brewer et al. 2009) thus highlighting the importance of understanding what promotes nursing staff job satisfaction.

Teamwork has been associated with a higher level of job staff satisfaction (Horak et al. 1991, Leppa 1996, Cox 2003, Rafferty et al. 2001, Gifford et al. 2002, Collette 2004). The relationship between teamwork and job satisfaction in the acute care inpatient hospital nursing team, defined as the Registered Nurses (RNs), Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs), nursing assistants (NAs) and unit secretaries (UAs) who work together on a patient care unit to provide nursing care to a group of inpatients, has received scant attention. Most recent research in healthcare on teamwork has been in perioperative and emergency settings and primarily focused on interdisciplinary teams (Morey et al. 2002, Silén-Lipponen et al. 2005, Salas et al. 2007, Mills et al. 2008).

Previous Studies

Original research and meta-analyses focusing on factors related to nurse job satisfaction have identified correlations with satisfaction to be decreased job stress (Blegen 1993, Zangaro & Soeken 2007), improved nurse-physician collaboration (Rosenstein 2002), greater job autonomy (Kovner et al. 2006, Zangaro & Soeken 2007), and adequate staffing (Aiken et al. 2002, Aiken et al. 2003, Cherry et al.. 2007). Additional studies found correlations between job satisfaction and friendships among staff members (Adams & Bond 2000, Kovner, et al. 2006), management support (Kovner et al. 2006, Chu et al. 2003), promotion opportunities (Kovner et al. 2006), communication with supervisors and peers, recognition, fairness, control over practice (Blegen 1993), professional commitment (Fang 2001), and collaboration with medical staff (Adams & Bond 2000, Chang et al. 2009).

Five research studies that specifically focused on the influence of teamwork on job satisfaction were uncovered (Cox 2003, Rafferty et al. 2001, Amos et al. 2005, DiMeglio et al. 2005, Chang et al. 2009). Rafferty and colleagues (2001) surveyed 10,022 nurses in England and found that nurses with higher interdisciplinary teamwork scores were significantly more likely to be satisfied with their jobs, planned to stay in them, and had lower burnout scores. Chang and colleagues (2009) found that collaborative interdisciplinary relationships were one of the most important predictors of job satisfaction for all healthcare providers. The relationship between group cohesion, a key process of teamwork, and nurse satisfaction before and after an intervention was studied by DiMeglio and colleagues (2005). The intervention increased both group cohesion and satisfaction among nurses. However they did not report whether there was a relationship between group cohesion and satisfaction. Using a six item survey instrument which measures quality of patient care, efficiency of nurses’ work, unit morale, spirit of teamwork, willingness to chip in, and job satisfaction, Cox found that team performance effectiveness had a significant positive influence on staff satisfaction (n=131) (2003). Because the measure included a variety of areas, not just teamwork, it is not possible to determine if teamwork per se predicted satisfaction. Finally, Amos and colleagues (2005) measured job satisfaction in 44 nursing staff members in one patient care unit where staff had undergone an intervention to improve teamwork. They found that the intervention did not result in greater satisfaction and they did not measure actual teamwork. Furthermore, the lack of a relationship could be attributed to a small sample size, which is another limitation of the study.

Studies of the job satisfaction of nursing assistants have shown dissatifiers to be excessive workload (Mather & Bakas 2002, Pennington et al. 2003, Crickmer 2005), not being recognized and valued for their contributions (Counsell & Rivers 2002, Mather & Bakas 2002, Spilsbury & Meyer 2004, Parsons et al. 2003, Crickmer 2005), pay (Parsons, et al. 2003, Decker et al. 2009), benefits (Parsons et al. 2003) and supervisor support (Decker et al. 2009). The only study that examined the relationship between teamwork and NA job satisfaction showed that lower levels of “hardiness” or coping skills of NAs was believed to contribute to higher psychological distress and decreased job satisfaction (Harrison et al. 2002). In contrast to several of the previous studies in this area, the current study focuses on teamwork within inpatient settings, uses a robust measure of nursing teamwork, employs a large sample size, and studies both nurses and NAs.

Conceptual Framework

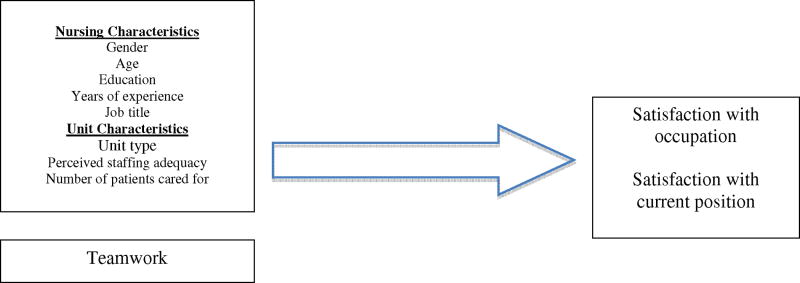

In this study, the independent variables were nurse and unit characteristics and teamwork and the dependent variables were staff satisfaction with current position and with occupation. The framework presented in Figure 1, hypothesizes that individual nursing staff characteristics (i.e., gender, experience, education, hours worked per week, shift worked, and role) and patient unit characteristics (i.e., type of unit, perceived staffing adequacy, and the number of patients cared for on previous shift) and teamwork influences the level of job satisfaction. Outside of healthcare research has shown significant positive relationships between age and job satisfaction (Rhodes 1983, Lee 1985, Schwoerer & May 1996), tenure (Clark 1997) and by gender (Clark 1997). Studies have also demonstrated that staffing levels are associated with nursing staff job satisfaction (Aiken et al. 2002, Aiken et al. 2003). Previous studies within nursing, as described above, and outside of nursing and healthcare have suggested that higher teamwork leads to greater job satisfaction (Griffin et al. 2001, Valle & Witt 2001, Mierlo et al. 2005).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework

Research Questions

The research questions for this study are:

Are individual and unit characteristics associated with satisfaction with current position and occupation?

Is teamwork associated with job satisfaction with current position and occupation?

Study Methods

Sample and setting

In this cross sectional study, 3,675 nursing staff members employed by four Midwestern hospitals, one Southern hospital and 80 different patient care units completed the Nursing Teamwork Survey (NTS) in 2009. This study focused on nursing teams on patient care units (as opposed to visitors to the units such as physicians, physical therapists, etc.). The return rate was 55.7%. The sample was made up of 71.3% nurses (RNs and LPNs), 16.5% assistive personnel, and 7.8% unit secretaries. LPNs were combined with RNs since there was only 1.4% (n=51) of the sample that identified themselves as LPNs.

Study Instrument

The survey instrument utilized in this study was the Nursing Teamwork Survey (NTS), a 33 item questionnaire with a Likert type scaling system from ‘Rarely (1)’ to ‘Always (5).’ The NTS is a survey designed specifically for inpatient nursing unit teams. The NTS was tested for its psychometric properties and are reported elsewhere (Kalisch et al. 2010). The survey items were generated with staff nurses and manager focus groups (Kalisch et al. 2009).

Psychometric testing of the NTS involved measures of acceptability, validity and reliability. Acceptability of the tool was high: 80.4% of the respondents answered all of the questions. Content validity index was 0.91, based on expert panels’ consistency among ratings of item relevance and clarity. The results from exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed good construct validity of the NTS with five factors as defined by Salas and Colleagues (2005) include: (a) Trust (i.e., shared perception that members will perform actions necessary to reach interdependent goals and act in the interest of the team), (b) Team orientation (i.e., cohesiveness, individuals see the team’s success as taking precedence over individual needs and performance), (c) Backup (i.e., helping one another with their tasks and responsibilities), (d) Shared mental model (i.e., mutual conceptualizations of the task, roles, strengths/weaknesses, and processes and strategy necessary to attain interdependent goals) and (e) Team leadership (i.e., structure, direction, and support), (χ2 = 12,860.195, df = 528, p < 0.001; Comparative fit index = 0.884, Root mean square error of approximation = 0.055, Standardized root mean residual = 0.045). The five factors explained 53.11% of the variance. The NTS also demonstrated concurrent, convergent and contrast validity. The overall test-retest reliability coefficient with 33 items was 0.92, and the coefficients on each subscale ranged from 0.77 to 0.87. The overall internal consistency of the survey was 0.94, and the alpha coefficients on each subscale ranged from 0.74 to 0.85. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) and index of agreement (rwg(j)) confirmed interrater agreement for each unit staff group.

The survey included questions about staff characteristics (education, experience, and gender), work schedules (shift, hours worked), perceptions about level of staffing, satisfaction with current position (referring to where the respondent is currently working) and satisfaction with being a nurse, a nurse assistant, or a unit secretary (occupation). Responses were made on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). These satisfaction items in the survey were tested for test-retest reliability; the coefficient for satisfaction with current position was 0.89 and for satisfaction with occupation was 0.66. Staffing adequacy was measured on a scale from 0% to 100% of the time. Respondents were asked to choose among five levels: staffing is adequate 100% of the time, 75%, 50%, 25% or 0% of the time. Nursing staff also indicated how many patients they cared for on the previous shift they worked. Other demographic data collected were education (highest degree earned), age, gender, years of experience in role, work schedule (shift worked, part or full time), and overtime (number of overtime hours in the past three months).

Procedures

After acquiring Institutional Review Board approvals at each facility, permission of the patient unit managers in the five facilities was obtained. All inpatient hospital units that met the inclusion criteria (i.e. inpatient units of all specialties) participated in the study. The surveys were distributed to the nursing staff members along with a cover letter containing consent information and instructions. All surveys were anonymous. The nursing staff were asked to place the completed survey in a sealed envelope and then into a locked box placed on each unit. Incentives to participate in the study included a candy bar with each survey and a pizza party if the unit reached at least a 50% return rate. Surveys were collected over a two to three week timeframe within each hospital in late 2008 and early 2009.

Data analysis

In this study, all bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted at the individual level with statistical software STATA 10. We estimated regression using the robust cluster estimation commands for all analyses to specify that the individual observations were independent across patient care units (clusters) but not within care units. Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) estimated by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) confirmed correlation of each unit member’s response to the group. Responses within each unit were significantly similar for the two satisfaction variables (F[79, 3569] = 4.85, p < 0.001, ICC = 0.078; F[79, 3563] = 1.88, p < 0.001, ICC = 0.019). Based on these ICCs, satisfaction levels of nursing staff within the same patient care unit were correlated.

Preliminary analyses using linear regression with the robust cluster estimation commands were completed to find significant independent variables associated with the two satisfaction variables. Then multivariate analyses using hierarchical linear multiple regressions with the robust cluster estimation commands was conducted for satisfaction with current position. Due to lack of data normality and linearity, the satisfaction with occupation variable was evaluated with a logistic regression model. For the purpose of logistic regression, the satisfaction variables were dichotomized into two groups—scores of 1–3 ‘dissatisfied’ and 4–5 ‘satisfied’. For teamwork, since strong correlations were found among five subscale scores, the overall mean score of 33 items was employed in the analysis. The level of all analyses was the individual nursing staff member.

Study Findings

Comparison was made between the study sample and the samples of RNs who reported in the 2004 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses in the study states (U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources HRSA 2006). In the current study sample, 62.3% of all of the nursing staff is over the age of 35 years, 55.7% had at least a baccalaureate degree in nursing, 83.8% worked full-time, and 8.3% were male (Table 1). Of the total RN population in 2004, the average age was 46.2years, 44.2% had a baccalaureate degree or higher, and 66.7% worked full-time (HRSA 2006). In comparison, these two samples were similar, but the study sample included more males, older nurses and more who worked full-time than the national survey sample. Since the latest data available in the National Sample Survey was actually collected in 2002, the larger number of men and nurses with baccalaureate degrees is expected with this passage of time. Also the Sample Survey collected data from all nurses, not just employed nurses, explaining the higher number working full time in the study sample. As can be seen in Table 1, NAs were less educated, less experienced, and younger than RNs while USs were similar to RNs on gender, age and experience.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n=3,675)

| Registered Nurse (RN) or Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) (n=2,620) | Nursing Assistant (NA) (n=605) | Unit Secretary (US) (n=286) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 217 (8.3%) | 107 (17.7%) | 15 (5.2%) |

| Female | 2329 (88.9%) | 490 (81.0%) | 261 (91.3%) |

| Age | |||

| Under 25 yrs old | 239 (9.1%) | 164 (27.1%) | 26 (9.1%) |

| 26 to 34 yrs old | 741 (28.3%) | 163 (26.9%) | 82 (28.7%) |

| 35 to 44 yrs old | 708 (27.0%) | 134 (22.1%) | 57 (19.9%) |

| 45 to 54 yrs old | 626 (23.9%) | 94 (15.5%) | 74 (25.9%) |

| 55 yrs old or older | 298 (11.4%) | 47 (7.8%) | 45 (15.7%) |

| Highest education Level | |||

| High school diploma or General Education Development | 46 (1.8%) | 366 (60.5%) | 167 (58.4%) |

| Associate degree | 1089 (41.6%) | 139 (23.0%) | 68 (23.8%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1356 (51.8%) | 78 (12.9%) | 41 (14.3%) |

| Graduate degree | 103 (3.9%) | 17 (2.8%) | 7 (2.4%) |

| Years of experience in the role | |||

| Up to 6 months | 94 (3.6%) | 39 (6.4%) | 19 (6.6%) |

| More than 6mth to 2 yrs | 483 (18.4%) | 155 (25.6%) | 55 (19.2%) |

| More than 2 yrs to 5 yrs | 449 (17.1%) | 160 (26.4%) | 59 (20.6%) |

| More than 5 yrs to 10 yrs | 447 (17.1%) | 107 (17.7%) | 60 (21.0%) |

| More than 10 yrs | 1122 (42.8%) | 139 (23.0%) | 91 (31.8%) |

| Years of experience on the unit | |||

| Up to 6 months | 176 (6.7%) | 73 (12.1%) | 24 (8.4%) |

| More than 6mth to 2 yrs | 689 (26.3%) | 212 (35.0%) | 76 (26.6%) |

| More than 2 yrs to 5 yrs | 623 (23.8%) | 152 (25.1%) | 68 (23.8%) |

| More than 5 yrs to 10 yrs | 503 (19.2%) | 89 (14.7%) | 49 (17.1%) |

| More than 10 yrs | 599 (22.9%) | 68 (11.2%) | 60 (21.0%) |

| Employment status | |||

| < 30 hrs/week | 422 (16.1%) | 145 (24.0%) | 79 (27.6%) |

| ≥ 30 hrs/week | 2196 (83.8%) | 456 (75.4%) | 297 (72.4%) |

| Shift worked | |||

| Days | 1171 (44.7%) | 274 (45.4%) | 158 (55.2%) |

| Evenings | 236 (9.0%) | 117 (19.3%) | 60 (21.0%) |

| Nights | 833 (31.8%) | 155 (25.6%) | 45 (15.7%) |

| Rotating | 376 (14.4%) | 58 (9.6%) | 22 (7.7%) |

| Type of working unit | |||

| Intensive care unit | 583 (22.3%) | 99 (16.4%) | 62 (21.7%) |

| Intermediate level unit | 283 (10.8%) | 83 (13.7%) | 22 (11.3%) |

| Medical surgical unit | 877 (33.5%) | 301 (49.8%) | 98 (34.3%) |

| Rehabilitation unit | 71 (2.7%) | 21 (3.5%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Pediatric/maternity unit | 211 (8.1%) | 18 (3.0%) | 29 (10.1%) |

| Pediatric intensive care or intermediate level unit | 244 (9.3%) | 23 (3.8%) | 27 (9.4%) |

| Psychiatric unit | 106 (4.0%) | 14 (2.4%) | 13 (4.5%) |

| Emergency department or transport team | 138 (5.3%) | 30 (5.0%) | 10 (3.5%) |

| Perioperative or operating room | 107 (4.1%) | 15 (2.5%) | 11 (3.8%) |

Significant independent variables associated with dependent variables

Preliminary bivariate linear regressions with the robust cluster estimation commands using STATA revealed significant relationships between satisfaction variables and independent variables. The satisfaction variables were significantly explained by teamwork and perceived staffing adequacy (all p < 0.001). For satisfaction with current position, participants’ levels of satisfaction were likely to be higher when they rated their teamwork higher (p < 0.001), perceived their staffing as adequate more often (p < 0.001), were older (p < 0.001) and more experienced (p < 0.01), were nurses (compared to NAs) (p < 0.01), cared for less numbers of patients (p < 0.05), and worked in maternity and pediatric areas (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001). For satisfaction with occupation, in addition to their higher levels of teamwork and perceiving their staffing as adequate more often (both p < 0.001), being a female (p < 0.001), a nurse (compared to NAs and USs, p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively), older (p < 0.05), more experienced (p < 0.05), more educated (p < 0.05), caring for less numbers of patients (p < 0.001), and working in psychiatric units and pediatric intensive care units (p < 0.05 to p < 0.01) were associated with a higher level of satisfaction.

Predictors of satisfaction with current position

Hierarchical linear multiple regression analysis with the robust cluster estimation commands was conducted at the individual level to determine predictors of the satisfaction variables. For satisfaction with current position, seven independent variables—teamwork, perceived staffing adequacy, age, job title, years of experience on the current working unit, number of patients they cared for on the last shift and type of unit—were included in the regression model based on preliminary descriptive statistics (Table 2). A dummy variable of study hospitals was included to control for organizational differences in the model, but each coefficient of the hospitals was not presented in Table 3 to avoid identification of the hospitals.

Table 2.

Summary of Hierarchical Multiple Regression for Variables Predicting Satisfaction with the Current Position (n=3,675)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Robust Std. Err. | Coefficient | Robust Std. Err. | Coefficient | Robust Std. Err. |

| Type of Unit | (p = 0.00) | (p = 0.00) | (p = 0.00) | |||

| Intensive care vs. Med-Surg. | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Intermediate level vs. Med-Surg. | −0.00 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Rehabilitation vs. Med-Surg. | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.05 |

| Pediatric/maternity vs. Med-Surg. | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.20* | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Ped. intensive or intermediate level vs. Med-Surg. | 0.29*** | 0.07 | 0.20** | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Psychiatric vs. Med-Surg. | 0.31** | 0.11 | 0.18* | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Emergency department vs. Med-Surg. | 0.26* | 0.13 | 0.24** | 0.07 | 0.21** | 0.05 |

| Perioperative vs. Med-Surg. | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Age | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Job title | (p = 0.39) | (p = 0.65) | (p = 0.57) | |||

| Nursing Assistant vs. Nurse | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Unit Secretary vs. Nurse | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.09 |

| Years of experience on the current working unit | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Number of patients cared for | −0.01* | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Hospital | (p = 0.00) | (p = 0.00) | (p = 0.00) | |||

| Staffing Adequacy | 0.36*** | 0.02 | 0.30*** | 0.02 | ||

| Teamwork | 0.50*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Complete Model R2 | 4.27 F (17, 79) = 6.0 p < 0.001 |

16.21 F (18, 79) = 33.88 p < 0.001 |

23.23 F (19, 79) = 47.90 p < 0.001 |

|||

Note:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Analysis included a dummy variable for study hospitals to control for its effect, but coefficients were not included in the table for the privacy of data (output suppressed).

Table 3.

Summary of Logistic Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Satisfaction with Occupation (n=3,675)

| Variable | Odds ratio | Robust Std. Err. | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork | 1.896 | 0.214 | 0.000 |

| Type of Unit | 0.023 | ||

| Intensive care vs. Medical-Surgical | 0.693 | 0.093 | 0.006 |

| Intermediate level vs. Medical-Surgical | 0.925 | 0.190 | 0.705 |

| Rehabilitation vs. Medical-Surgical | 1.243 | 0.240 | 0.260 |

| Pediatric/maternity vs. Medical-Surgical | 0.832 | 0.202 | 0.448 |

| Pediatric intensive care or intermediate level vs. Medical-Surgical | 1.049 | 0.244 | 0.839 |

| Psychiatric vs. Medical-Surgical | 1.388 | 0.300 | 0.129 |

| Emergency department vs. Medical-Surgical | 1.114 | 0.252 | 0.633 |

| Perioperative vs. Medical-Surgical | 0.807 | 0.207 | 0.403 |

| Age | 1.002 | 0.055 | 0.964 |

| Education | 0.839 | 0.061 | 0.016 |

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | 0.591 | 0.085 | 0.000 |

| Job title | 0.000 | ||

| Nursing Assistant vs. Nurse | 0.423 | 0.078 | 0.000 |

| Unit Secretary vs. Nurse | 0.463 | 0.141 | 0.011 |

| Years of experience on the current working unit | 1.055 | 0.073 | 0.441 |

| Staffing Adequacy | 1.553 | 0.091 | 0.000 |

| Number of patients cared for | 0.993 | 0.009 | 0.448 |

| Hospital | 0.013 |

Note:χ2 (21) = 330.57, p < 0.001

Analysis included a dummy variable for study hospitals to control for its effect, but coefficients were not included in the table for the privacy of data (output suppressed).

Table 2 summarizes procedure consisted of three stages to test partial R2 for both teamwork and perceived staffing adequacy. With significant unit and staff characteristic variables, Model 1 accounted for 4.3% of the variation in satisfaction with the current position (F (17, 79) = 6.0, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.043). For type of unit, those in pediatric intensive or intermediate level units, psychiatric units, and emergency departments had higher levels of satisfaction than medical and surgical unit staff (all p < 0.05). Also, nursing staff who cared for more patients reported a lower level of satisfaction (all p < 0.05). Once adding perceived staffing adequacy into the group of independent variables, Model 2 accounted for 16.2% of the variation in the satisfaction variable (F (18, 79) = 33.88, p < 0.001, R2 = 0. 162). The nursing staff holding perceptions that their staffing was adequate had a higher level of satisfaction with their current position (p < 0.001). The three types of units still appeared significant to explain satisfaction with the current position; in addition, nursing staff in pediatric or maternity units reported a higher level of satisfaction than medical surgical unit staff (all p < 0.05). The number of patients cared for was not a significant predictor any longer.

Finally, teamwork was added into the model; Model 3 accounted for 23.2% of the variation in the satisfaction variable (F (19, 79) = 47.90, p < 0.001, R2 = 0. 232). The nursing staff scoring higher teamwork as well as holding perceptions that their staffing was adequate had higher levels of satisfaction with their current position (both p < 0.001). For type of unit, those in emergency departments had higher levels of satisfaction than medical surgical unit staff (p < 0.01). There were no significant differences between staff in the remaining types of unit and staff in medical surgical units. Hospital site also appeared to predict the levels of satisfaction with nursing staffs’ current position (p < 0.001).

Predictors of satisfaction with occupation

Due to the lack of data normality and linearity, logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine predictors of satisfaction with occupation. As shown in Table 3, nine independent variables—teamwork, perceived staffing adequacy, gender, age, education, job title, years of experience on the current working unit, number of patients cared for in last shift, and type of unit—were included in the regression model based on preliminary descriptive statistics. A dummy variable of study hospitals was included again in order to control for hospitals in the model.

A significant model emerged for satisfaction with occupation (χ2 (21) = 330.57, p < 0.001). The nursing staff scoring higher teamwork and perceiving adequate staffing were more likely to be satisfied with their occupation (both p < 0.001). Males and the nursing staff with higher levels of education were less likely to be satisfied with their occupation (p < 0.001, p < 0.05, respectively). The direction of the relationship between level of education and satisfaction differed once we controlled for other significant variables. For job title, both NAs and USs were less likely to be satisfied with their occupation than nurses (p < 0.001, p < 0.05, respectively). Intensive care units’ nursing staff were less likely to be satisfied with their occupation than those in medical and surgical units (p < 0.01). Similar to the findings related to satisfaction with current position, hospital site appears to predict the levels of satisfaction with occupation (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Satisfaction with current position

The results of this study demonstrate that in nursing teams on acute care patient units, a higher level of teamwork and perceptions of higher levels of staffing adequacy leads to greater job satisfaction with current position. Another significant predictor of satisfaction with current position was type of unit: emergency departments were higher. There was significant variation in satisfaction variables found by hospital, which suggests that other variables not examined in this study may influence the levels of staff satisfaction with their current position. Further research including hospital- and unit-level variables with a larger sample size would need to be completed to demonstrate whether these findings are generalizable or if they are dependent on the particular patient care units studied. None of the other variables are shown to influence satisfaction with current position.

Satisfaction with occupation

Higher levels of teamwork and perceptions of staffing adequacy also lead to greater job satisfaction with occupation. NAs and USs are less satisfied than nurses; men are less satisfied than females; and ICU staff are less satisfied than medical-surgical staff members. The latter finding differs from what has been found in previous studies where intensive care staff are more satisfied at least when the unit culture was considered supportive (Kangas et al 1999) The greater satisfaction of nurses as opposed to NAs and USs may be accounted for by several factors. First nurses have a higher status and level of power, influence and autonomy than the USs and NAs. This finding is supported by an early and well-known theory in the job design field, the Job Design Theory by Hackman and Oldham (1975). This theory suggests that jobs that involve higher autonomy, task significance, task identity, and skill variety results in higher levels of satisfaction. Men may be less satisfied with their occupation because of their minority status within the field. Currently men comprise only 5.8% of the total RN population in the USA (HRSA 2006). Some research suggests that men may identify more with the male dominated physician profession, thus become dissatisfied with nursing’s lower pay and status (Williams 1995).

The findings of this study expands our understanding of what contributes to satisfaction of nursing staff working together on inpatient acute care hospital units. Besides a large sample size, this study utilized a measurement tool designed specifically for inpatient nursing teams and based on a theory of teamwork that explicates specific teamwork behaviors (i.e. shared mental models, trust, backup, team orientation, leadership etc.) that have been found to be characteristic of effective nursing teamwork (Kalisch et al. 2009). The tool also has demonstrated good psychometric properties for a new tool (Kalisch et al. 2010).

Teamwork clearly is an important contributor to satisfaction as are perceptions of staffing adequacy. One limitation of this study is that the data was collected in only five hospitals thus making it difficult to generalize the findings to the broader population. This is mitigated somewhat by the large sample size (much larger than previous studies on this subject) and by the selection of hospitals of a variety of sizes (120 to 913). A comparison of the respondents in this study with the RN National Survey showed that this study sample is similar to those data. Another limitation is that teamwork is based on self-report by staff as opposed to actual observations of nursing staff at work.

Implications

There are countless numbers of nursing teams working in inpatient care units in acute care hospitals across the world. Yet these teams have received little research attention. The findings of this study suggest that efforts to improve teamwork in these settings would have a positive impact on staff satisfaction. If nursing staff are not satisfied, like workers in general, they will be more likely to leave their position/occupation and/or to have a lower level of productivity (Hayes et al. 2006, Kovner et al. 2007). Increasing satisfaction would likely result in cost savings since high job satisfaction is linked to lower turnover (Hayes et al. 2006) and intent to leave (Brewer et al. 2009). On average nurse turnover costs hospitals at least $82,000–$88,000 per staff member (Jones 2008).

Moreover, increased teamwork would lead to safer and higher quality of care. The Institutes of Medicine report on To Err is Human (Kohn et al. 2000) study pointed out that higher teamwork is linked to safety. Salas et al. (2007) showed the close associations of patient safety with team effectiveness and shared mindset in healthcare.

Results of this study point to the need to enhance nursing teamwork on patient care units. Salas and colleagues (2009) recommended seven evidence-based strategies to develop, enhance and sustain successful team training. These include: (a) alignment of team training objectives and safety aims with organizational goals, (b) providing organizational support, (c) encourage participation of frontline leaders, (d) adequate preparation of environment and staff for team training, (e) determination of resources and required time commitments, (f) facilitation of application of acquired teamwork skills and (g) measurement of the effectiveness of the team training program. Kalisch et al (2007) found similar essential elements in interventions to improve teamwork. These elements include: (a) promotion of staff feedback, (b) identification of shared values, vision and goals, (c) enhanced communication, (d) coaching (i.e. leadership reinforcement) and (e) implementation of guiding teams (composed of leadership and staff). Furthermore, efforts to move all staff to 12-hours shifts instead of a mixture of 8-hour and 12-hours shifts as a as a means to decrease hand-offs between shifts and to decrease the number of different people they worked with also improved teamwork scores (Kalisch et al, 2007). The role of the nurse manager should be in supporting the application of the teamwork intervention afterwards, coaching and ongoing measurement of the effect of the teamwork training intervention.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by The Michigan Center for Health Intervention, University of Michigan School of Nursing, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (P30 NR009000).

Contributor Information

Beatrice J. Kalisch, Nursing Business and Health Systems, University of Michigan, School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Hyunhwa Lee, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research, Division of Intramural Research, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Monica Rochman, University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References

- Adams A, Bond S. Hospital nurses’ job satisfaction, individual and organizational charateristics. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;32(3):536–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Silber JH, Sloane D. Hospital nurse staffing, education, and patient mortality. LDI Issue Brief. 2003;9(2):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos M, Hu J, Herrick C. The impact of team building on communication and job satisfaction of nursing staff. Journals of Nursing Staff Development. 2005;21(1):10–16. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blegen M. Nurses’ job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of related variables. Nursing Research. 1993;42(1):36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer C, Kovner C, Green W, Cheng Y. Predictor’s of RNs’ intent to work and work decisions 1 year later in a U.S. national sample. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:940–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Registered nurses: Occupational outlook handbook. 2009 Retrieved April 1, 2009, from http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos083.htm.

- Chang W, Ma J, Chiu H, Lin K, Lee P. Job satisfaction and perceptions of quality of patient care, collaboration and teamwork in acute care hospitals. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(9):1946–1955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry B, Ashcraft A, Owen D. Perceptions of job satisfaction and the regulatory environment among nurse aides and charge nurses in long-term care. Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY) 2007;28(3):183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Hsu M, Price J, Lee J. Job satisfaction of hospital nurses: An empirical test of a causal model in taiwan. International Nursing Review. 2003;50:176–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2003.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. Job satisfaction and gender: Why are women so happy at work? Labour Economics. 1997;4(4):341. [Google Scholar]

- Collette J. Retention of staff: Team-based approach. Australian Health Review. 2004;28(3):349–356. doi: 10.1071/ah040349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counsell C, Rivers R. Consider this: Inspiring support staff employees. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2002;32(3):120–121. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox KB. The effects of intrapersonal, intragroup, and intergroup conflict on team performance effectiveness and work satisfaction. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2003;27(2):153–163. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crickmer A. Who wants to be a CNA? The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2005;35(9):380–381. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker FH, Harris-Kojetin LD, Bercovitz A. Intrinsic job satisfaction, overall satisfaction, and intention to leave the job among nursing assistants in nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(5):596–610. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio K, Padula C, Piatek C, Korber S, Barrett A, Ducharme M, et al. Group cohesion and nurse satisfaction: Examination of a team-building approach. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2005;35(3):110–120. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y. Turnover propensity and its causes in Singapore nurses: An empirical study. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2001;12(5):859–871. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford BD, Zammuto RF, Goodman EA. The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses’ quality of work life. Journal of Healthcare Management/American College of Healthcare Executives. 2002;47(1):13–25. discussion 25–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin Mark A, Patterson Malcolm G, West Michael A. Job satisfaction and teamwork: The role of supervisor support. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2001;22:537–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1975;60:159–70. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison M, Loiselle CG, Duquette A, Semenic SE. Hardiness, work support and psychological distress among nursing assistants and registered nurses in Quebec. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;38(6):584–591. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LJ, O’Brien-Pallas L, Duffield C, Shamian J, Buchan J, Hughes F, et al. Nurse turnover: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43(2):237–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak BJ, Guarino JH, Knight CC, et al. Building a team on a medical floor. Health Care Management Review. 1991;16(2):65–71. doi: 10.1097/00004010-199101620-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CB. Revisiting nurse turnover costs: Adjusting for inflation. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2008;38(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000295636.03216.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas S, Kee CC, McKee-Waddle R. Organizational factors, nurses’ job satisfaction, and patient satisfaction with nursing care. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 1999;29(1):32. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch BJ, Curley M, Stefanov S. An intervention to enhance nursing staff teamwork and engagement. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2007;37(2):77–84. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200702000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch BJ, Lee H, Salas E. The development and testing of the nursing teamwork survey. Nursing Research. 2010;59(1):42–50. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181c3bd42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch BJ, Weaver SJ, Salas E. What does nursing teamwork look like? A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2009;24(4):298–307. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3181a001c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovner C, Brewer C, Wu YW, Cheng Y, Suzuki M. Factors associated with work satisfaction of registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(1):71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovner C, Brewer C, Fairchild S, Poornima S, Kim H, Jadjukic A. A Better Understanding Of Newly Licensed RNs And Their Employment Patterns Is Crucial To Reducing Turnover Rates. American Journal of Nursing. 2007;107(9):58–70. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000287512.31006.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. Age, education, job tenure, salary, job characteristics, and job satisfaction: A multivariate analysis. Human Relations. 1985;38(8):781. [Google Scholar]

- Leppa CJ. Nurse relationships and work group disruption. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 1996;26(10):23–27. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather KF, Bakas T. Nursing assistants’ perceptions of their ability to provide continence care. Geriatric Nursing. 2002;23(2):76–81. doi: 10.1067/mgn.2002.123788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierlo H, Rutte C, Kompier M, Doorewaard H. Self-managing teamwork and psychological well-being. Organizational Research Methods. 2005;12(2):368–392. [Google Scholar]

- Mills P, Neily J, Dunn E. Teamwork and communication in surgical teams: Implications for patient safety. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2008;206(1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey JC, Simon R, Jay GD, Wears RL, Salisbury M, Dukes KA, et al. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: Evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health Services Research. 2002;37(6):1553–1581. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons SK, Simmons WP, Penn K, Furlough M. Determinants of satisfaction and turnover among nursing assistants. the results of a statewide survey. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2003;29(3):51–58. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20030301-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington K, Scott J, Magilvy K. The role of certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2003;33(11):578–584. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty AM, Ball J, Aiken LH. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Quality in Health Care. 2001;10(2):32–7. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100032... [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SR. Age-related differences in work attitudes and behavior: A review and conceptual analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;93(2):328–367. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein AH. Original research: Nurse-physician relationships: Impact on nurse satisfaction and retention. The American Journal of Nursing. 2002;102(6):26–34. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200206000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas E, Almeida S, Salisbury M, King H, Lazzara E, Lyons R, Wilson K, Almeida P, McQuillan R. What are the critical success factors for team training in health care? The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2009;35(8):398–405. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas E, Sims DE, Burke CS. Is there “big five” in teamwork? Small Group Research. 2005;36(5):555–599. [Google Scholar]

- Salas E, Rosen MA, King H. Managing teams managing crises: Principles of teamwork to improve patient safety in the emergency room and beyond. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics. 2007;8(5):381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Silén-Lipponen M, Tossavainen K, Turunen H, Smith A. Potential errors and their prevention in operating room teamwork as experienced by Finnish, British and American nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2005;11(1):21–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilsbury K, Meyer J. Use, misuse and non-use of health care assistants: Understanding the work of health care assistants in a hospital setting. Journal of Nursing Management. 2004;12(6):411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwoerer CE, May DR. Age and work outcomes: The moderating effects of self-efficacy and tool design effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1996;17(5):469. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources: Health Resources and Service Administration. The registered nurse population: Findings from the March 2004 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Valle M, Witt LA. The moderating effect of teamwork perceptions on the organizational politics--job satisfaction relationship. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;141(3):379–388. doi: 10.1080/00224540109600559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL. Hidden advantages for men in nursing. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 1995;19(2):63–70. doi: 10.1097/00006216-199501920-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangaro GA, Soeken KL. A meta-analysis of studies of nurses’ job satisfaction. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30(4):445–458. doi: 10.1002/nur.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]