Background

Approximately 13% to 14% of youth (ages 0–17) had special health care needs (SHCN) in 2001 and 2005/2006 (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2002, 2008). The U.S. Census Bureau also estimated in 2002 that 10% of youth between the ages of 15 and 24, or approximately 4.1 million youth, had a disability (Steinmetz, 2006). Youth with disabilities or SHCN are aging into adulthood because of improvements in socioeconomic conditions, hygiene, control of infectious diseases, and improvements in medicine (Guyer, Freedman, Strobino, & Sondik, 2000). For example, children with cystic fibrosis (CF) in 1955 were not expected to live to first grade, but by 2000 the predicted median age of survival for CF had risen to 32 years; in 2005, it was 36.5 years (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation).

One aspect of increasing life expectancy that has recently gained the attention of researchers, policy makers, and practitioners is the transition from pediatric to adult health systems among youth. Professional association policy statements describe the goals of transition as: “to maximize lifelong functioning and potential through the provision of high-quality, developmentally appropriate health care services that continue uninterrupted as the individual moves from adolescence to adulthood. It is patient centered, and its cornerstones are flexibility, responsiveness, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination” (American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, & American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine, 2002). Policy statements describe key transition principles that pertain to youth and families, such as: assuming responsibility for current care, care coordination, and future health care planning; enhancing autonomy, personal responsibility, and self-reliance; acquiring self management skills and condition-related knowledge; and acquiring referrals to postsecondary services systems. Other principles that apply to health care providers include: identifying the knowledge and skills required to provide transition services and make them part of training and certification requirements; creating with the young person and family a written health care transition plan by age 14; and maintaining flexibility to meet the needs of a wide range of young people and circumstances (American Academy of Pediatrics, et al., 2002; Rosen, Blum, Britto, Sawyer, & Siegel, 2003). This description of transition encompasses, but is not synonymous with the idea of transfer from pediatric health systems to adult health systems. Transfer is one component or an event-related phenomenon in contrast to transition which is a process. However, experts have described the movement toward adult-oriented systems as the “the normal, expected, and desired outcome of pediatric care” (Reiss & Gibson, 2002).

While all youth experience health care transition, the transition for youth with disabilities or SHCN may require particular attention because persons with disabilities or SHCN utilize health care at high rates, may require long term therapy, and often rate their health as fair to poor (Dejong, et al., 2002; Havercamp, Scandlin, & Roth, 2004; Okumura, McPheeters, & Davis, 2007). As youth with disabilities or SHCN age into adulthood, challenges with transitioning have begun to emerge. Only 41% of youth with SHCN ages 12 to 17 in 2005/2006 met the Maternal Child Health Bureau’s transition outcomes: doctors usually or always encourage increasing responsibility for self-care; and (when needed) doctors have discussed transitioning to adult health care, changing health care needs, and how to maintain insurance coverage (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2008). Use of pediatric facilities by individuals over the age of majority also suggests difficulties in health care transitions by youth with chronic health conditions. Among hospitalizations, young adults aged 18 years and over constituted almost 5% of discharges from 10 US pediatric hospitals (Goodman, Mendez, Throop, & Ogata, 2002). From 1992 to 2001, a children’s hospital in Australia experienced a significant increase in admissions of young adults, many with multiple complex condition. The authors note a “striking lack of evidence supporting transition to adult healthcare” (Lam, Fitzgerald, & Sawyer, 2005).

Identifying an appropriate framework for understanding transition among youth with disabilities or SHCN is important because of the increasing number of youth with disabilities or SHCN moving into adulthood. It is also important because a framework would address a criticism of the transition literature that studies have been primarily descriptive and atheoretical in design (Betz, 2004; Betz & Redcay, 2005; Stewart, Law, Rosenbaum, & Willms, 2001; Stewart, Stavness, King, Antle, & Law, 2006). A useful framework helps to organize findings from studies in a cohesive way and helps to show how concepts relate to one another. In turn, researchers, practitioners, and policy makers can utilize those conceptual relationships to plan and design studies, interventions, and outcomes. Further, an appropriate framework must acknowledge disability and SHCN as a product of the complex and multiple interactions between individuals and their environments. The World Health Organization states, “Disability is always an interaction between features of the person and features of the overall context in which the person lives, but some aspects of disability are almost entirely internal to the person, while another aspect is almost entirely external…” (World Health Organization, 2002).

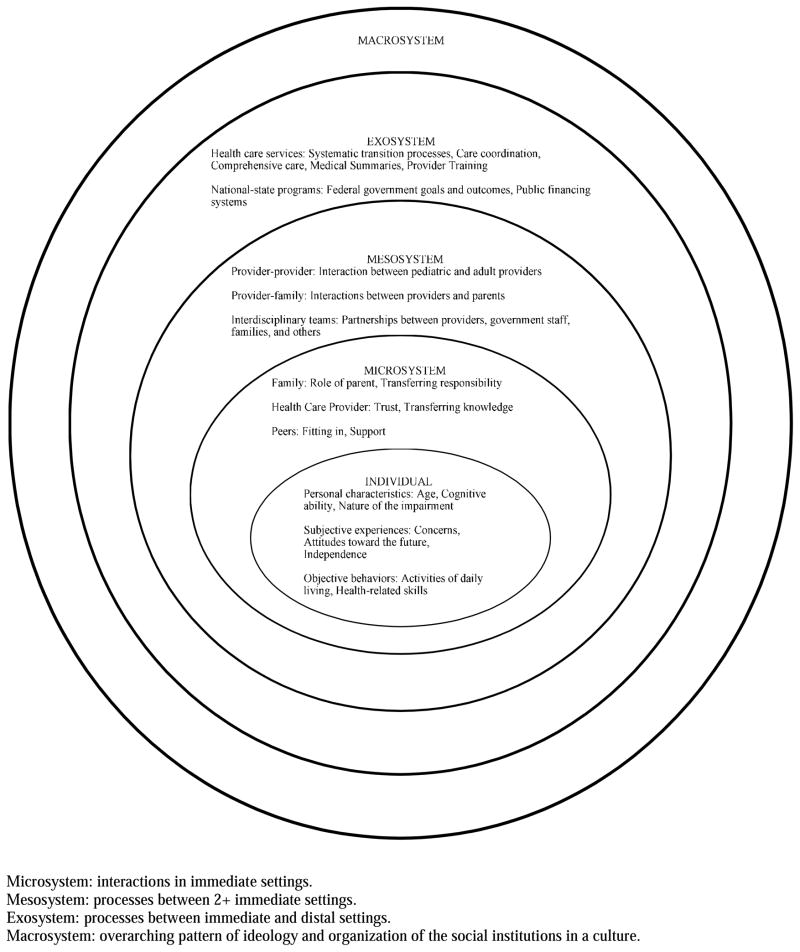

We propose the ecological model as an ideal theory to frame research and interventions of the health care transition experience given the internal/external duality of disability and SHCN and the multiple settings involved in transitions. To explore the application of the ecological model to transition, this literature review has three aims: 1) to describe the ecological model; 2) to use published literature to identify concepts and themes relevant to transition and to categorize them into the levels of the ecological model; and 3) to discuss how researchers, practitioners, and program planners can incorporate the multiple contexts of the ecological model in future work.

Overview of the ecological model

First proposed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, the ecological model describes a system with multiple environments that surround an individual. Features of environments relevant to an individual’s development include both its objective properties and the way a person subjectively experiences these properties. A person has increasingly complex, reciprocal interactions with environments, and environments beyond the immediate setting can indirectly influence an individual (Bronfenbrenner, 2005a).

There are four distinct environments surrounding the individual. The microsystem consists of interpersonal interactions between the individual and people in immediate settings. This may include an individual’s exchanges with family members in the home or with health care providers in health settings. The mesosystem describes connections between members of immediate environments and their influence on an individual. An example of the mesosytem is how a relationship between the individual’s family members and her health care provider affects her. Next, the model broadens into the exosystem. Aspects of the exosystem intersect with an individual’s immediate environment, thereby indirectly influencing an individual. However, the exosystem does not directly involve or come into contact with an individual. Here, an administrative decision within a payer system to cover certain services affects whether an individual receives services. Another example of an exosystem factor is the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and its effect on youth with disabilities or SHCN. Finally, the macrosystem is the larger social system and encompasses economic forces, cultural beliefs and values, and political actions (Bronfenbrenner, 2005b, 2005c; Sallis & Owen, 1997). An individual’s development and events in the multiple environments occur within the time in history that each person lives out her lifetime (Abrams & Theberge, 2005). Progression of time results in shifts in settings or roles, which “alter how people are treated, how they act, what they do, and thereby even what they think and feel” (Bronfenbrenner, 2005b).

Methods

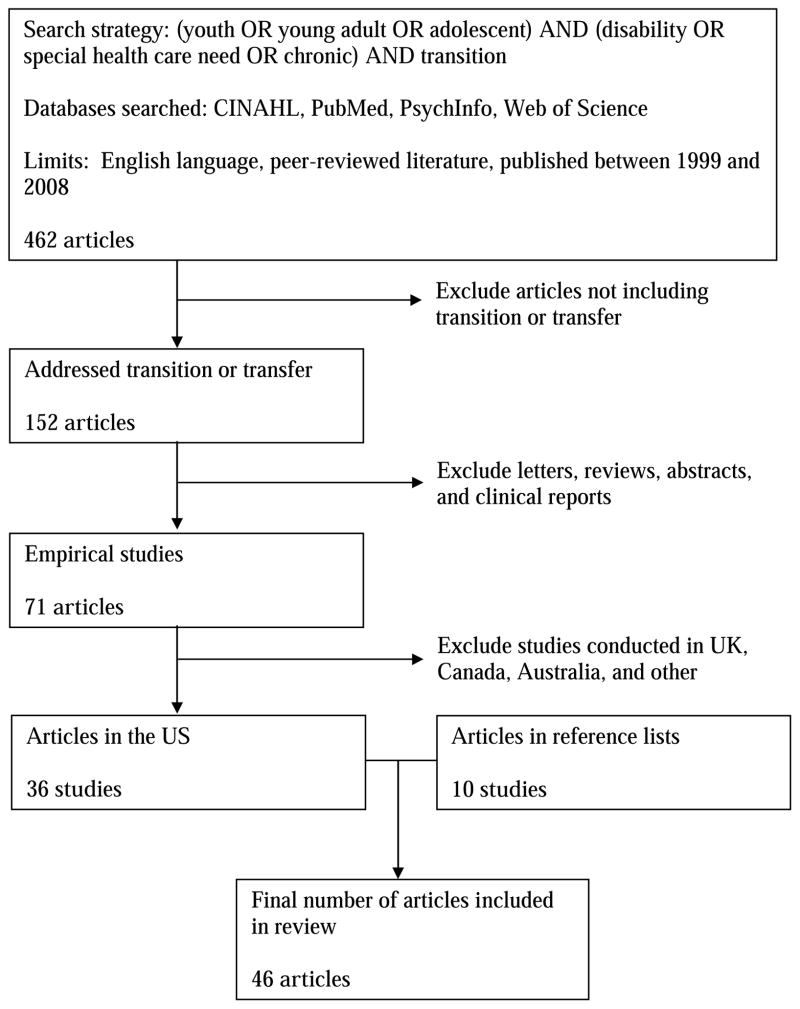

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, PsychInfo, and Web of Science using the search strategy: (youth OR young adult OR adolescent) AND (disability OR special health care need OR chronic) AND transition. Articles were restricted to English language articles published in peer-reviewed literature between 1999 and 2008. Abstracts were reviewed to identify articles addressing health care and transition during young adulthood or transfer from pediatric health care to adult health care. The search was refined to include only empirical studies. Finally, articles were further restricted to those conducted in the United States because of cross-national differences in cultures, health care delivery, and financing systems. The search yielded 462 articles. Of the 152 articles addressing transition, 71 articles reported on empirical studies. After omitting studies conducted outside the US, 36 articles remained.

We also hand searched the reference lists of included articles in order to collect references missed by the original search strategy. This search yielded 10 additional articles; the review includes a total of 46 articles. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Search strategy

We categorized major study findings into the ecological model based on the following criteria: 1) Individual – the findings were related to personal characteristics, subjective experiences, and objective behaviors of a youth. These studies focused heavily on perceptions, feelings, and actions. 2) Microsystem – the findings described or offered details about the interactions between a youth and other people. The observations about the interactions may have been from the perspective of the youth or from other members of the microsystem. 3) Mesosystem – the findings addressed the interactions between anyone involved in transition other than youth themselves. An example is parents working with health care providers. 4) Exosystem – the findings identified practices or models that were or could have been implemented at a systems level with implications for interactions within microsystems. 5) Macrosystem – the findings described broad socio-cultural or political events that may have influenced transition experiences or youth with disabilities or SHCN.

Ecological model, applied to transition (Table 1, Figure 2)

Table 1.

Empirical Studies Included in the Review

| Reference | Study Objective | Theoretical framework |

Sample | Study design |

Data source and/or data collection |

Analysis Methods | Key findings related to transition or transfer | Limitations | Model level and concept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Anderson, et al., 2002) | To report the opinions of adult cystic fibrosis (CF) patients regarding the transition process. | Not discussed | Survey sent to 1,288 CF patients on a mailing list provided by the International Association of Cystic Fibrosis Adults (IACFA). 334 surveys returned = 25.9% response rate. |

Des, Quant, Cross-section | CF Transition Survey: Patient Version. Questions addressed why patients do not receive care at CF centers, why they do not see internists, transition programs, concerns, transfer process, assuming responsibility for care, and the adult CF team’s ability to manage emotional and medical needs | Characteristics were compared using either chi-square statistics or Hotelling’s T2 test. Analysis of variance statistics to compare perceptions of patients’ concerns about transition as rated by CF program directors to concerns as rated by the patients. | 24% patients seen at a CF center received care from a pediatrician, while 76% were followed by an internist or family practitioner. The groups did not differ significantly in age, gender, employment, or parental status. Patients seen by a pediatrician were more likely to be full-time students and to live at home with parents than those seen by an internist. 76% of the 67 patients followed by pediatricians reported no available adult program. Of age, marital status, and pregnancy, the most frequently cited criterion for transfer was age. The transfer concept was introduced to 10% of patients prior to age 15 years. Most CF patients felt the list of concerns in the survey were either “not a problem” or only a “mild problem” Physicians perceived greater patient concerns than patients reported themselves; the pediatricians perceived greater concerns than did the internists, Patients rated importance of a transition program prior to transfer to an adult program as “moderate” |

Potential bias of population: motivated population that joined IACFA. 26% response rate: this group was perhaps more independent, more ready for transfer, older, past the age of recommended transfer. |

Indiv: Person char |

| (Betz & Redcay, 2005) | to describe transition-aged youth and young adults who were provided comprehensive health care transition services. To provide a descriptive profile of health related concerns, school and extracurricular activities, employment activities, social relationships, and future plans. | Not discussed | 25 youth between14 and 21 years who were provided transition services between 2/99 and 9/01 through the Creating Healthy Futures clinic. | Des, Retro, Quant, Cross-section | Data extracted from the clinic intake assessment forms on education; employment; living situation; and social, leisure, and community | Response frequencies determined for the sample and by personal characteristics. Response frequency comparisons performed using exact c2 tests. An alpha-level of 0.10 was utilized. | 60% had missed school due to their condition. 44% obtained health-related accommodations. 24% reported health care providers assisted them with obtaining school accommodations. 32% indicated the school nurse assisted with obtaining school accommodations. Respondents identified needs related to achieving self-sufficiency and/or competency with activities of daily living: managing money (40%), shopping (36%), preparing meals (32%), cooking (28%), and managing health condition (28%). |

Small number of respondents | Indiv: Obj behav |

| (Betz, et al., 2003) | To describe health care self-care needs and self-sufficiency of ASHCN. To demonstrate relationships among health care self-care needs, level of health care self-sufficiency, and demographics. To establish validity of the California Healthy and Ready to Work Transition Health Care Assessment (CA HRTW THCA) tool and to test the tool with a convenience sample of ASHCN. |

Not discussed | 25 transition-aged youth between 14 and 21 years with special health care needs who were seen in the Creating Healthy Futures transition clinic between February 1, 1999, and September 30, 2001 | Des, Retro, Quant, Cross-section | Information obtained from charts included demographics, diagnoses, years since diagnoses, living arrangements, family structure, education, and employment. Self-care items were from the California Healthy and Ready to Work Transition Health Care Assessment tool. 72 questions assessed: knowledge and skills related to condition, preventative and emergency health care measures, health-related accommodations, community resources, long term disability management, communication, health insurance, responsible sexual activity, legal protections, and transportation. | Domain-specific summary percent measures for positive and negative responses were obtained for each subject. Summary percents of positive (“yes”) and negative responses were calculated. Student t-tests were used to contrast domain-specific skills between diagnostic groups. | More than 90% of respondents answered yes to: current with immunizations and health care screenings, recognize when they are getting ill related to their SHCN, have a primary care physician, brush and floss their teeth, and recognize when they are getting sick with a cold or urinary tract infection. More than 75% of the respondents answered no to: have a MediAlert bracelet/necklace, applied for other public services, understand the ADA rights, and use Access Van Domains with highest percent yes responses were monitor health condition, track health records, obtain information and reproductive counseling, and responsible sexual activity. Domains with the lowest percent yes responses were knowledge of legal rights and protections, understanding of need for environmental modifications/accommodations, manage SHCN, and knowledge of health insurance concerns/issues. Domains with highest percent no responses were knowledge of legal rights and protections, engage in preventative health behaviors, access community resources, knowledge of health condition/management, and use transportation safely. Domains with lowest percentage of no responses were track health records, responsible sexual activity, monitor health condition, understanding of need for environmental modifications/accommodations, and knowledge of emergency measures |

All data were self- reported, which could have resulted in overestimation of self-care behaviors and socially desirable responses. Respondents may not have fully understood questions. Parents may have provided proxy responses. Findings cannot be generalized due to small sample and instrument limitations. Youth referred for transition services may have characteristics dissimilar from other youth with special health care needs. |

Indiv: Obj behav |

| (Blomquist, 2006a) | To look at the transition outcomes of graduates of pediatric systems of care for children with disabilities and chronic conditions | Not discussed | 456 youth 18 years and older who were discharged by a CSHCN program in KY and 194 youth discharged by a children’s hospital in KY. response rate = 51% | Des, Retro, Quant, Cross | mail survey focused on healthcare access and use, insurance, health behaviors and perceptions, education, work, and independent living. | Descriptive frequencies reported. No statistical tests conducted | 18% of respondents said they were referred to an adult-focused doctor by the Commission, Shriners, or a pediatrician. | Half of graduates responded, and their characteristics may have differed from non-respondents. Limited geographic region. Self-report data, and 30% of youth got help completing the survey. Survey may have measurement error/bias. Cross-sectional data, so no causation can be implied. |

Micro: Prov |

| (Blomquist, 2006b) | To describe the activities, outcomes, and lessons learned from Kentucky’s Healthy and Ready to Work initiatives | Not discussed | Kentucky’s Healthy and Ready to Work (HRTW) initiatives | Des, Retro, Qual, Case Study | Case study | Review of historical timeline of transition, overview of evaluation survey results, summary of program components and activities | This article describes the Kentucky Commission for Children with Special Health Care Needs partnership with Shriners Hospitals, families, state and community agencies to coordinate services and transition programs. | Not discussed | Meso Exo: Health services |

| (Boyle, et al., 2001) | To identify expectations and concerns of patients and families transitioning into an adult CF clinic | Not discussed | before transition survey administered to: Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Family Education Day attendees, patients at pediatric clinic scheduled to transition to adult care within 3 months. 52 patients and 38 parents completed questionnaires. Posttransition survey to patients previously cared for at pediatric clinic who transitioned to adult program |

Exp, Pros, Quant, Cross-section | the 22-question survey was based on review of previous studies on CF transition, discussion with adult and pediatric team members, and 4 adult patients | Mean scores and standard deviations were calculated. Paired and unpaired t- tests were performed. | For the pretransition survey, concerns for patients prior to transition were: potential exposure to infection, leaving previous physician, meeting new care team, and potential decrease in quality of medical care. Prior to transition, important expectations included: phone access to a nurse, education about adult CF issues, confidence that adult CF team could provide quality care. 60 patients completed the posttransition survey. Of the 52 patients who completed the pretransition survey, 30 had previously met the adult team and 22 had not. Patients who had not previously met the adult team had higher levels of concern in all areas. Patient concern about leaving previous caregivers increased once they had been in the pediatric clinic for 3+ years. 8 of 38 parents expressed fear that transition to adult program would prevent them from being as involved in their child’s CF care. |

Groups surveyed did not represent all undergoing transition. By surveying onlyparents who attended family day or who accompanied child to clinic visit, concerns of parents less active in their children’s care may have been excluded. Pre- and posttransition survey cohorts were not identical, thereby decreasing the strength of conclusions when comparing responses |

Indiv: Subj exp Micro: Fam, prov |

| (Burke, et al., 2008) | To determine the present state of the health care transition process for adolescents and young adults with and without special health care needs from the perspective of the primary care pediatrician. | Not discussed | Survey of 169 practicing primary care pediatricians in Rhode Island. 103 pediatricians responded (response rate = 60.9%). | Des, Retro, Quant, Cross-section | 13-question survey developed after discussion with primary care pediatricians, parents and patients. It addressed: policies and practices, timing, processes of adolescent transfer, barriers to transfer, role of health plans, practitioner experiences with transfer. | Descriptive frequencies were calculated. X2 test was used where applicable. SAS used for statistical analysis. | 87% indicated that their practices had not yet developed written practice policies on the transition and transfer of adolescents with and without special needs. 70% reported having no difficulty in finding adult providers for adolescents. Age out is the most common reason to leave pediatric care. Drop out and moved out occurred more frequently for adolescents without special needs than for those with special needs. More adolescents with special health care needs hung out compared with peers without special needs. |

Survey asked for a mix of factual responses, opinion, and estimations because quantitative data were not available from most practices. This limited statistical analysis. Not generalizable to other states or settings. |

Exo: Health services |

| (Callahan & Cooper, 2006) | To assess health insurance coverage and access of young adults with chronic disabling conditions | Not discussed | 1109 survey respondents with and 22,481 without disabling chronic conditions, aged 19 to 29 years. Nationally representative sample. | Des, Retro, Quant, Cross- section | National Health Interview Survey 1999–2002 | Bivariate analyses showing relationships between unmet health care needs and insurance. Multivariate analyses to estimate odds of reporting unmet health care needs. | Uninsured young adults with disabling chronic conditions had higher odds of delaying or missing needed care, having no health professional contact, or having no usual source of health care than insured young adults with disabling chronic conditions. | Self-report may be subject to recall or response error. Cross-sectional survey prevents conclusion that uninsurance resulted in unmet health care needs. Authors wanted to analyze differences in unmet needs among those with different health insurance types, but had insufficient sample size. |

Exo: Nat- state prog |

| (Callahan & Cooper, 2007) | to use longitudinal survey data to compare the continuity of health insurance coverage and the number of months of uninsurance reported by adolescents and young adults with and without disabilities during a 36-month period and to assess the continuity of health insurance for different age groups of young adults with disabilities. | Not discussed | 599 young adults with and 4571 young adults without disabilities, ages 16 to 25. Nationally representative sample | Des, Retro, Quant, Long | Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2001 | Descriptive statistics to characterize young adults with and without disabilities, differences in the characteriswere assessed using standard errors of the difference of sample estimates using formulae provided by the US Census Bureau | Young adults with disabilities were as likely as those without disabilities to report having a gap in health insurance coverage. 5% of 16- to 18-year-olds with disabilities were uninsured at the start of the study, and 46% reported a gap in coverage during the next 36 months. 30% of 19- to 21-year-olds with disabilities were uninsured at the start of the study, and 62% reported a gap in coverage during the study period. Similar rates were seen for 22- to 25-year-olds. |

Self-report may be subject to recall and nonresponse bias. Nonresponse and loss to follow-up may have made the study sample different from the population. Assessment for disability occurred at differing points during study follow- up; therefore, unknown how many young adults developed limitations after study onset or if limitations resolved during study. |

Exo: Nat- state prog |

| (Christian, et al., 1999) | To explore and describe adolescents’ perspectives of living with diabetes during adolescence | Discussion of adolescence and independen ce | Purposeful sampling: 2 females and two males between 15 and 17 years of age with diabetes for at least one year. Recruited from a university pediatric diabetes center in the Southeast. | Des, Retro, Qual | Semi-structured interviews began with the adolescent’s earliest memory of having diabetes and continued to the present. | Grounded theory | Gaining freedom was the central phenomenon that captured the process of gaining self-responsibility in diabetes management during adolescence. Three themes marked the process: a) making it fit; b) being ready and willing; and c) having a safety net of friends. These adolescents described a gradual transition from dependence to independence in learning to live with diabetes. One adolescent explained how he practiced making decisions and gaining independence from his parents and health care providers by creating a collaborative relationship with them. |

The pilot study gave preliminary data that cannot be generalized beyond participants. | Ind: Subj exp Micro: Fam, peers |

| (Davis, et al., 2006) | To describe how many transition service programs were available in child and adult state mental health systems across the United States. | Not discussed | Interviews conducted with Adult Services members and Child, Youth and Families Division members of a professional organization of state mental health administrators in 41 states and DC. | Des, Retro, Qual | Semi-structured interviews of child and adult services administrators. Interviews lasted from 15 to 90 minutes. | answers were coded into ten broad categories of service types and four geographic distributions | Each transition service type was available in less than 20 percent of states with the exceptions of special comprehensive services and housing services. Special comprehensive services included assertive community treatment or wraparound approaches in which a single entity provided or brokered a full array of needed services. When service types were available, they were rarely available at more than one site in the state. | Validity of questions and coding scheme reliability were unknown. Study provided no inferences on transition service capacities in decentralized mental health systems or in private Medicaid BHOs in 13 states. |

Exo: Health services |

| (Fishman, 2001) | To present previously unpublished data on young adults with disabilities and describe the insurance gaps among young adults with serious chronic illnesses. | Not discussed | Nationally representative sample of young adults ages 19 to 29 with varying levels of disability | Des, Quant, Cross- section | Survey on Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 1996 | Not discussed | In 1996, almost 22% of younger adults (ages 19–29) with disabilities are uninsured, a proportion much larger than is the case for similarly disabled children (age 18 and younger). About 36% have public coverage, and 42% have private insurance Article also discusses state programs for specidic health conditions and work programs |

Not discussed | Exo: Nat- state prog |

| (Flume, et al., 2001) | To assess the current status of transition programs in US CF centers. To determine problems, as perceived by CF center program directors, related to the transfer of CF patients to adult programs. | Not discussed | 154 program directors of CFF- certifed CF centers. 104 surveys returned = 67.5% response rate |

Des, Quant, Cross- section | CF Transition Survey: 35-item survey that has forced-choice and open- ended questions covering 1) type of transition and transfer program at that center; 2) perceptions of concerns of patients, parents, and pediatric and adult center staff about the transfer process; and 3) ratings of receptivity and success of the transfer program. | Perceptions of the program directors were evaluated using Hotelling’s T2 test, comparing the results of pediatric program directors to those of adult program directors. | Of the pediatric programs that responded, 35% had a CFF-approved adult program, 22% had an internist on the team, and 39% has no specific adult program. 22% cited lack of an available adult CF physician as an impediment to establishing an adult CF program. Age (82%) was frequently a criterion for transfer, but marriage (17.1%) and pregnancy (24.8%) were not. Issues that hindered transfer included patient/family resistance (51.4%), medical severity (50.5%), and developmental delay (46.7%). Transfer to the adult program was introduced to patients and families at average age of 15.9 years 52% of respondents reported that patients did not meet the adult team until the time of transfer. Pediatric directors expressed perceived concerns about adult team capacity to meet medical and emotional needs of patients and families. Pediatric directors also viewed patients as having concerns about severing relationships with the pediatric staff and reluctance to leave pediatrics. Ratings of success of transition programs were inversely correlated with concerns about adult staff meeting patients’ medical and emotional needs. |

Not discussed | Indiv: Person char Meso Exo: Health services |

| (Flume, et al., 2004) | to obtain CF team members’ unique perspectives regarding transition, and to compare these perspectives to those obtained from physicians and patients previously assessed using a similar methodology. | Not discussed | all CF centers across the country were asked to have their team members, excluding physicians, complete and submit the survey. 291 completed surveys = unknown response rate |

Des, Quant, Cross- section | CF Transition Survey: Team Member Version, internet based survey asking about asked about: 1) organization of CF care and team structure; 2) respondent’s role on the CF team; and 3) issues related to transfer of care, including perceptions about patient’s transition and success of established transition programs. | Results are reported as means and standard deviations | Respondents were: 135 nurses (46.4%), 49 social workers (16.8%), 46 nutritionists (15.8%), 34 respiratory therapists (11.7%), and 27 (9.3%) “other” (e.g., physical therapist, psychologist, or genetic counselor). 46% serviced on both pediatric and adult teams, while 34% served on the pediatric team only, and 20% on the adult team only. Patient age was the most commonly cited criterion that led to patient transfer. 86.2% endorsed CF patients being transitioned by the time they reach age 21 years. Patient/family resistance to transfer (45%), disease severity (34%), and developmental delay (31%) were the most common factors that would prevent transfer. Team members rated perceived patient concerns about transfer as “mild” to “moderate.” A majority of respondents reported feeling that their transition program was moderately successful. This did not depend on team role. Team members and internists held similar concerns regarding transition. These are greater than concerns endorsed by patients themselves. |

Not discussed | Meso |

| (Gee, et al., 2007) | To highlight the issues that confront urban, underserved minority young people with diabetes as they enter adulthood. | Not discussed | 23 young adults with diabetes between 19 and 26 years of age from the Chicago Childhood Diabetes Registry, the University of Chicago Adult Endocrinology Clinic, and the Fantus Clinic at John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County. | Des, Retro, Qual | Semi-structured interviews addressing themes Self- management, education, social life, employment and future | Transcribed interviews were coded and analyzed for common themes | Although attitudes toward disease evolved and became more sophisticated over time, negative emotions dominated. The financial demands of diabetes had a significant impact on life choices. As subjects aged out of pediatrics, many reported meager guidance toward establishing relationships with adult physicians. Two participants received referrals, but others received no help. Insurance requirements often drove transition to adult providers. Family members often handled medications, diet, and blood testing, but preteen and teen years were marked by more independence in diabetes care. Many subjects had ongoing support from family. Social support was significant, but disclosure to peers presented challenges. |

Participants did not represent a range of socioeconomic strata or educational levels because drawn from urban clinics serving underserved populations. Non-English speakers were excluded; their attitudes/concerns may have differed. Cannot comment on how youth with diabetes differed from healthy peers. Comfort level with the telephone format and/or understanding of questions may have influenced responses. |

Indiv: Subj exp Micro: Fam, peers |

| (Geenen, et al., 2003) | to clarify what the role of health care providers should be in assisting adolescents with disabilities or SHCNs during transition, from both the perspective of families as well as providers themselves. | Not discussed | Parents of children (13–21 year of age) identified through Oregon public school system and Title V program. A total of 753 parent surveys were returned, for a response rate of 31%. Providers from Oregon Pediatrics Society and Title V. One hundred forty-one provider surveys were returned for an overall response rate of 34%. |

Des, Quant, Cross- section | A survey was developed based on literature review and input from families, providers, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Healthy and Ready to Work Projects. Survey included: 13 transition activities that health providers may engage in. |

To investigate whether parents and providers shared views on provider involvement and responsibility, Student’s t-tests were calculated. Variation by disability of child assessed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) |

Activities identified as having the greatest importance to parents included: taking care of general health and disability, coordinating care, helping to get health insurance, finding an adult provider, teaching how to manage health, and working with the school to coordinate care. Areas with the greatest differences between parents and providers were: talking about drugs and alcohol; teaching how to manage health; and talking about sexual issues Barriers to transition reported by providers included: time, needing more training, financial reimbursement, needing more information from families before participating. Parents’ qualitative comments for improving transition: coordinated care, provider training in transition, a more holistic approach to health and well-being, working directly with adolescents. |

Parents’ and providers’ responses could not be matched. There was not a one-to-one correspondence between the providers referenced by parents and providers who completed the survey. Response bias and the nature of the sample prevented direct conclusive statements about parents and providers not participating in the study. Providers’ self-report may not have accurately reflected true behavior. |

Micro: Prov Meso Exo: Health services |

| (Giarelli, Bernhardt, Mack, et al., 2008) | To explain the socially complex process by which parents transfer, and children take on, the responsibility for managing a chronic genetic disorder. | lifelong surveillance symbolic interactionism |

young adults with MFS up to age 35; 39 Parents of individuals with MFS; 16 Providers experienced at treating or counseling people with MFS | Des, Qual | 1- or 2-hour-long, in-depth interviews by telephone using open-ended questions | grounded theory with in vivo coding. Level I coding produced concepts fundamental to the phenomenon. Level II coding produced concepts related to psychosocial processes. Level III coding linked concepts to show interrelatedness. Participants and parents verified model credibility. |

The core variable for the adolescent in TSM of a chronic geneticdisorder was becoming fit and fitting in. The continual and active integration of the facts of one’s chronic illness with the expectations for one’s life. It comprises physical and psychosocial domains. While becoming fit and fitting in, the adolescent shows illness-awareness, health-preservation, self-surveillance, and self-advocacy. TSM depended on how the person dealt with the imperative to be fit and fit in with one’s social group, by way of five psychosocial processes: shifting perceptions, shifting orientation, shifting ownership, shifting reasoning, and shifting sphere |

The racial and ethnic composition of the sample was homogeneous, and parents were predominantly female. The full spectrum of experiences might not have been captured. | Indiv Subj exp Micro peers:: |

| (Giarelli, Bernhardt, & Pyeritz, 2008) | to examine systemic factors that influence transition to self-management (TSM). | becoming fit and fitting in. developmental contextualism |

Stratified purposive sampling of: 53 Children and young adults with MFS up to age 35; 39 Parents of individuals with MFS; 16 Providers experienced at treating or counseling people with MFS. | Des, Qual | secondary analysis of narrative data | Interpretive content analysis | 3 major attitudes, or frames of mind, promoted TSM: belief in the diagnosis, wanting to understand the cause and effect of MFS, and willingness to share responsibility in problem solving. Parental fears presented obstacles to belief in the diagnosis, but the patient–parent–provider partnership was instrumental in facilitating belief. Incorporating knowledge of MFS into the child’s life by parents increased understanding about MFS. While mixed messages from parents hindered shared problem solving, knowledge about health histories helped with problem solving |

A sample size of 92 was relatively small for generalization to all families with MFS. 15 providers did not capture all experiences. Self-selection bias threatens generalizability. Sample was homogeneous for sociodemographic characteristics. The specific impact of particular medical problems and comorbidities were not explored. |

Indiv: Subj exp Micro: Fam |

| (Hagood, et al., 2005) | To report on a one-week course for medical students that focuses on the concept of transition to adulthood for youth with special needs. | Not discussed | Medical school course at the University of Alabama School of Medicine | Des, Qual | Case study | Description of course design and experience with implementation | Course design: he course uses cystic fibrosis as a model and includes both classroom and clinical components. Objectives are for the student to understand: 1) principal components of home and hospital medical management of young adults with CF; 2) influence of chronic illness on families, especially the impact on transition to independence; and 3) impact of debilitating complications of chronic illness on independent functioning. |

Not discussed | Exo: Health services |

| (Hartman, et al., 2000) | to examine the service and support needs of adolescents with special health care needs who are transitioning to adulthood. | Not discussed | Parents of 3 young adults with disabilities | Des, Qual | life histories were conducted to ascertain perspective of parents on longitudinal events and factors in the lives of adolescents with special health care needs that shaped or influenced health and adolescent transition to adulthood. | 3 researchers conducted thematic and taxonomic analysis | 6 themes identified: begetting a service system, pathology or not pathology, educational stability v interruption, role blurring, private life made public, independence and burden. Role blurring refers to the experience of parents having to relinquish duties and decisions that are typically made by parents to others outside of the family while having to function in a service provider role as well. Independence and Burden depicts the conflict between the desire for the adolescent’s independence and the sense of burden for the youth and his/her family. informants placed significant emphasis on “independence-building” opportunities to the future independence and confidence of their adolescents. Each parent described the adolescent’s independence unfolding in school, money management and socialization and other arenas of daily life. |

Findings were not intended to represent the experience of parents beyond those interviewed. Informants were parents reflecting on the lives of their children and families and thus the actual lived experience of the adolescents was not ascertained. |

Indiv: Subj exp, Obj behav Micro: Fam |

| (Hauser & Dorn, 1999) | To identify and understand the concerns, expectations, and preparation needs adolescents and parents have about transition; to describe the perceived differences between pediatric and adult care, barriers, experiences and common practices of practitioners; to identify the natural points of transition; and to generate a framework for transitioning. | Adolescents aged 13 through 21 years old with sickle cell disease receiving their care at one of the four pediatric sickle cell centers in a large Midwestern city; primary caretaker or parents; pediatric and adult clinicians. 9 focus groups: 4 with adolescents, 4 with parents, 1 with practitioners |

Des, Qual | Semi-structured focus groups centering on open-ended questions designed to lead groups through a common set of issues to obtain the participants’ perspectives. Open- ended questions were extrapolated from the literature and researchers’ experience. | Data were analyzed by content analysis whereby responses for each set of groups were categorized by research objectives and within each category common issues were identified. Common issues were identified by consensus. A transitioning advisory committee with 13 members from practitioner, adolescent, and parent focus groups, the adult health care consumer group, and the State Department of Rehabilitation confirmed findings and developed a framework. | Adolescents’ concerns: leaving familiar, trusted people and place; going to an adult doctor who was unfamiliar with treating SCD; and worrying that parents would not let them grow up, leave home, or visit the doctor alone. Adolescent expectations: doctors would speak to them rather than through parents and that they would go to the clinic alone; physical setting would be less child-like; and they would receive current info on SCD research Adolescent preparation needs: provide education on how to manage SCD and new research; orient them to new doctors and clinic; meet adults with SCD who go to the same doctor. Parent concerns: losing their own support system and anticipating role change. Practitioners’ perceived barriers: overly dependent families and youth; pediatric providers who foster dependency; lack of communication between pediatric and adult providers; and lacking insurance coverage. Practitioners’ reported factors that indicate readiness: age, educational level, emotional maturity, independent functioning, being able to keep appointments Practitioners said a transition program should be at a comprehensive center with a support structure for the family and separate educational components for the practitioners. The purpose should be: teach self-responsibility; educate patients and parents on the disease complications and treatment; prepare the adult team; prepare the child team to transfer the adolescent. |

Results cannot be generalized to a larger population due to small sample size and the fact that participants were not a random sample representative of the target population. This information was not obtained in the participant’s natural setting and, therefore, some uncertainty existed about the accuracy of what participants said. |

Indiv: Person char, Subj exp Micro: Fam, prov Meso Exo: Health services |

|

| (LoCasale-Crouch & Johnson, 2005) | To define issues in pediatric patients at the University of Virginia | Not discussed | 62 of 105 surveys were returned from the adult nephrology providers in Virginia. 6 pediatric patients and their families from the University of Virginia |

Des, Qual and Quant, Cross-section | Survey of adult nephrologists throughout Virginia asking about practices in relation to patients transitioned from pediatric nephrology care. interviews or focus groups with 6 pediatric patients and their families that focused on their transition to adult nephrology. |

Not discussed | Only 34% of adult providers have nurse practitioners working in their clinics, 66% have access to social workers, 69% have dietitians, and 71% employ registered nurses. 76% providers spent more than 30 minutes with a patient on the first office visit, and 51% found the interview with the patient to be the most helpful component in learning the patient’s medical history. 43% of providers found the entire medical record helpful when receiving a new patient, whereas 62% found a one-page medical summary more helpful. All patients and families were comfortable with their knowledge of their medical condition and appropriate treatment. Most of the young adults wanted more information about preventative health behaviors, specific coping strategies, adaptive measures in stressful situations, and use of community resources. Coordination of information across settings and role expectations of the medical system, schools, and communities in supporting transition needs were unclear. How information is relayed (in writing, over the phone) to the family by practitioners within the same practice followed no set protocol. Consequently, patients and families reported feeling that they often had to prompt providers to ensure that all needed communication occurred. Patients and families felt they would benefit from more consistent plans of care. Youth and families faced complex insurance systems. They felt overwhelmed by the issues surrounding their insurance coverage. |

Not discussed | Indiv: Subj exp Meso Exo: Health services |

| (Lotstein, et al., 2005) | To present findings on the planning for health care -transition services currently received by adolescents with special health care needs. To describe the transition- planning practices of health care providers nationwide for YSHCN from the perspective of parents and guardians. | Not discussed | 5533 youth with special health care needs (YSHCN) 13–17 years old. Nationally representative sample. | Des, Quant, Cross- section | 2001 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs | bivariate relationships among sociodemographic variables and each transition question and the overall outcome measure. multivariate logistic regression to assess independent predictors associated with meeting the transition- performance measure. |

50% of respondents reported discussing child’s changing health care needs in adulthood with providers Of respondents reporting changing needs, 59% also reported developing a plan with provider to address changing needs ~42% of those who reported having discussed changing needs discussed shifting care to an adult provider 15.3% of all youth met the MCHB core outcome measure of having received guidance and support in the transition to adulthood Older age and medical home were associated with meeting MCHB outcome |

The questions about future adult needs and transition planning were added after the survey had begun, so this analysis represented only 40% of all teens in the survey. No state level analyses because of the relatively small sample size. Study could not address whether the lower rates of transition discussion for Hispanic youth are due to language barriers; the primary spoken language was unknown for the respondents. |

Exo: Nat-state prog |

| (Luther, 2001) | to validate Blomquist’s transition recommendations and to explore successful strategies. | Discusses theories related to developme ntal tasks for young adults | Parents of children with special needs who were affiliated with the Shriners Hospital for Children, Intermountain and Utah Parents Center 22 parents were selected and self- assigned into two focus group sessions. |

Des, Qual | focus groups using an interview guide with open-ended questions was used to gather information from “parent experts” regarding strategies to facilitate transition to adulthood Parents were given a tool that listed age and age- appropriate transition activities as defined by Blomquist and were asked to measure their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). |

Not described | The activity with the highest positive agreement was “do not do for them what they can do for themselves.” This task was hard at the differing developmental stages. Health professionals influence parents’ hope for the future and the child’s ability to do for themselves. Nurses often instilled hope for a level of autonomy. Parents agreed with “helping children interact in a variety of settings.” This required involving the community and tailoring activities for child’s abilities. Parents highly agreed with “Assigning appropriate household chores.” 2 items that received the lowest scores “find out about school-to- work programs” and “encourage teen to contact Vocational Rehabilitation” targeted work identity. Many parents had never heard about school-to-work programs. The item with the lowest level of agreement was “see your pediatric provider and adult provider for one year prior to transition.” While some said this was a “wasteful, costly, and controlling activity,” one parent thought this would “encourage transition rather than just a transfer…” Parents felt that health professionals versus parents played a larger part in “help your children talk to their health care providers to aid the child taking responsibility for their own health care.” Parents recommended health professionals talk directly to the child, listen, and encourage them to talk and learn about their diagnosis and how it affects them. |

Small sample size limits generalizability of the data to a similar disability population. | Indiv: Person char, Obj behav Micro: Fam, prov Meso |

| (McLaughlin, et al., 2008) | To characterize in detail the transition experiences and practices of current US-based cystic fibrosis (US CF) programs using a structured survey of the multidisciplinary teams at CF programs nationwide. | conceptual model with transition activities at CF programs grouped into 7 domains: preparation, readiness assessment, coordination of services and benefits, information transfer, primary and preventive care, patient follow-up and program evaluation, self- evaluation. | US CF programs Responses (n = 448) were received from 87% (170 of 195) of CFF-accredited programs. |

Des, Quant, Cross- section | Closed and open-ended questions assessed presence of processes, the consistency of occurrance, and method of support. 10-point self-evaluation performance scale for clinical centers. Clinicians and researchers reviewed survey tool. final survey: 3 closed- ended demographics items, 96 closed-ended items grouped by domains of transition services, 3 closed-ended questions regarding CFF transition mandate and financial impact on centers, 3 open-ended questions for concerns |

Correlations coefficients and alpha statistics used to assess intracenter and intercenter variability. Descriptive statistics for transition processes were generated using frequency weighting to account for variable numbers of respondents across centers. Analysis of variance tests used to compare responses across respondent roles and program types. |

Patient Preparation: Initial discussion of transition occurred at median age of 17 yrs. Transfer occurred at median age of 19 yrs. Half of programs allow patients to delay or decline transition. Reason: end-stage disease, developmental delay, patient/physician unwillingness, lung transplantation. 28% of programs consistently offer transition visits.<25% of programs “usually” or “always” provide transition education materials.<50% provide a transition timeline. Readiness Assessment: 50% CF programs assess readiness, and <10% have a written list of self-management skills. readiness assessments were infrequently reported for identifying and contacting insurer (26%) or understanding insurance benefits (43%). Primary Care: 62% of programs reported that patients “usually” or “always” had a primary care provider (PCP). CF teams were “usually” or “always” aware of the PCP and informed them about a transfer of CF care at 68% of programs. Coordination of Services: Anticipated changes in insurance coverage were “usually” or “always” discussed at 76% of programs Information Transfer: >80% of programs discussed transition of individual patients at pediatric team meetings; however, only one third of programs reported that adult care providers were present at meetings. 46% of programs reported “never” or “rarely” preparing a medical summary before transfer. Patient Follow-up: Almost 60% of programs that transfer care reported a mechanism to confirm first visit with adult clinic. Self-Evaluation: On a scale from 1 to 10 (ideal), the mean self-rating was 5.8 (SD: 2.2). |

Not discussed | Indiv: Person char Meso Exo: Health services |

| (McPherson, et al., 2004) | To review the development of the monitoring strategy and describe the analytic approach and the data sources used for evaluating success. To present baseline results for the 6 core outcomes | Not discussed | 38,866 children with special health care needs (CSHCN). Nationally representative sample. | Des, Quant, Cross- section | 2001 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs | Calculated estimates of the proportion of children who met each goal | An estimated 15.3% of CSHCN who were 14 through 17 years of age received appropriate guidance and support in the medical aspects of the transition to adulthood. This estimate includes those teens whose doctors 1) have talked with them or their families about changing needs, 2) created a plan for addressing changing needs, and 3) discussed shifting to an adult health care professional. | Not discussed | Exo: Nat-state prog |

| (Morningstar, et al., 2001) | to gather information using longitudinal interview techniques regarding the experiences of family members and students supported by medical technology. | Not discussed | Purposive sampling family members or students supported by medical technology involved with transition planning. professionals who had been or were currently supporting the student’s transition. 8 mothers, 4 students, and 12 professionals participated. |

Des, Qual | longitudinal, in-depth, open-ended interviews to gather perspectives regarding transition planning experiences. Each participant was interviewed twice over a 2-year period to track changes in transition experiences over time. Questions addressed:

|

All data units were coded and sorted by category. Expansion of initial categories included additional themes that emerged from the second round of interviews. The researchers developed interpretive summary sheets for the categories. Then the research team met to review and reach consensus regarding the summaries. |

Future expectations of students and parents: Themes included a) future living expectations; b) future career and postsecondary education expectations; and c) the role that professionals and school programs play in supporting future expectations. Implementation of transition planning: a) school-based transition planning as is required by IDEA. b) whether participants had begun planning for the transfer of health care services from the pediatric to adult medical systems. Over half indicated no planning for transition of health care services had occurred because youth required continued services past 21 and the family expects Medicaid to continue to pay; mother anticipates the process of obtaining funding for health care coverage to be time-consuming and difficult; health care was provided by private insurance or settlement and will continue into adulthood; the mother provides all health care support and will continue to do so. Not planning led to youth’s concerns regarding changes in government policies related to medical services and funding. Participation and involvement in transition planning: parents and school personnel were always identified as participating. Students, medical personnel, vocational rehabilitation, and outside others were less consistently identified as having a role. |

Not discussed | Indiv: Subj exp Micro: Fam |

| (Oftedahl, et al., 2004) | To present the Wisconsin-specific data derived from analysis of the national survey and compare with the US as a whole | Not discussed | 750 children with special health care needs (CSHCN). State representative sample | Des, Quant, Cross- section | 2001 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs | The proportion of children who met goal | For the transition outcome, the Wisconsin data did not meet standards for reliability because of the small number of observations. | Data were most reliable in areas where all 750 respondents answered questions. Survey was limited to families with phones or to families willing to participate in a phone interview. Families with children with extreme needs may not have participated. |

Exo: Nat- state prog |

| (Osterlund, et al., 20) 05 | To examine how adolescents with spina bifida and their families interact with their medical records during the transition from pediatric to adult-oriented care. | Not discussed | Participants were drawn from a population base of 34 young adults aged 18–21 years receiving comprehensive care at a regional referral center for persons with spina bifida and spinal cord injury A convenience sample of 6 patients (4 men and 2 women), 6 family members (4 mothers and 2 fathers) and a private duty home nurse participated. |

Des, Qual | Focus groups and structured interviews | Grounded theory involving aggregating common or recurring themes followed by categorizing and coding interview transcripts | 3 groups emerged as central to patients’ medical record keeping: hospitals, subspecialty providers, and mothers. All patients regarded parents, esp mothers, as key to record keeping. Patients recognized the importance of managing healthcare information but delegated to parents. Patients remembered some pertinent healthcare events but not to the same degree as mothers. Medical records maintained by families were organized chronologically. Patients and parents reported that standard questions on medical forms failed to capture the complexity of spina bifida care. Providers asked the same generic questions again and again. Patients and parents felt that many healthcare providers deliberately did not want them to have access to their medical record. They perceived that their medical information belonged to them and not to providers and institutions. Patients and parents also expressed concern that healthcare institutions did not share medical information. Parents and patients supported online access to medical records. Medical emergencies highlighted the need for a complete and accessible medical record. |

Small sample and qualitative, exploratory, and descriptive nature limited findings. Participants represented motivated parents and well functioning patients. Specific needs of spina bifida patients seeing a large number of sub- specialties may have shaped responses. Some ideas and perspectives may have been left out given the flow of the focus group interviews. |

Micro: Fam Meso Exo: Health services |

| (Okumura, et al., 2008) | to assess general internists’ and general pediatricians’ comfort in providing care to adult patients with chronic illnesses of childhood origin and to identify factors associated with treatment comfort. | Conceptual framework on how comfortable physicians felt treating a specific disease | random sample of internists and pediatricians identified through the American Medical Association Masterfile who reported primary profession as general internal medicine or general pediatrics and reported providing “direct patient care.” 1288 responded, leading to an overall response rate of 53% |

Des, Quant, Cross- section | mailed survey with statements about primary care, beliefs, and comfort and a 6- point Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. Factors associated with comfort and resource availability also assessed |

compared characteristics and views of internists and pediatricians using bivariate statistics. two sets of multivariate logistic regression models stratified by specialty. First set of models examined factors associated with treatment comfort. Second set examined whether treatment comfort was associated with primary care physicians’ views on whether an adult- focused generalist provider was best suited to provide care for young adults with either CF or SCD |

Internists and pediatricians were similarly comfortable in being the PCP for 17–25 year old patients with SCD, but less comfortable being the PCP for patients with CF and congenital heart disease. Both were more comfortable treating patients with common diseases than treating patients CF and SCD. About half of general pediatricians reported that a pediatrician (generalist or specialist) should be delegated primary care responsibility for an 18-year-old young adult with CF or SCD Over 80–90% of internists thought an adult-focused provider (generalist or specialist) should take responsibility for the primary care needs of an 18-year-old young adult with CF or SCD. 24% of internists and 21% of pediatricians report insufficient training severely or significantly limited ability to provide care to young adults aged 17–25 with chronic illness. Pediatricians were more likely than internists to report barriers due to insufficient time, insufficient mental healthcare support, insufficient social work support. Experience treating a larger number of patients with CF and SCD in practice was associated with higher treatment comfort for both internists and pediatricians Higher treatment comfort among internists was, in turn, significantly associated with delegating to an internist primary care responsibility for patients aged 18 with CF and SCD. |

Study did not assess comfort level of other provider types. Results may have differed if study used an older age range in questions. Study did not assess comfort of internists in treating youth without chronic conditions, so lack of comfort cannot be attributed entirely to treating chronic conditions. Estimate of treatment comfort could be biased if there was systematic bias among non- respondents. Cross-section design did not show causality. Lack of association between ready access to subspecialists may be because most internists had subspecialty access. Focus on CF and SCD prevented generalizability to other diseases. |

Micro: Prov Exo: Health services |

| (Okumura, et al., 2007) | To profile the characteristics and health care utilization of ASHCN on state and national levels. To describe current patterns and state-to- state variations in insurance coverage for ASHCN. |

Not discussed | 102,353 children in the US. Nationally representative sample | Des, Quant, Cross- section | National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) 2003 | national and state-level prevalence estimates of insurance status, number of doctor visits, and unmet health care needs negative binomial regression adjusting for socioeconomic status and patient factors |

Based on data from 2003 to 2004, almost 900,000 ASHCN will reach the age of majority annually. ASHCN averaged about one more visit per year than their adolescent non-SHCN counterparts (2.3 vs. 1.4 visits) 16.5% or approximately one in six ASHCN are under public plans but in income brackets that would make them income ineligible for coverage at age of majority. |

Survey was based on caretaker proxy report, so inaccurate reporting and misclassification from recall bias were possible. Study could not predict adolescent’s future income. Insufficient information about specific medical conditions prevented estimation of effects on coverage in states with exemptions for particular conditions. |

Exo: Nat- state prog |

| (Palmer & Boisen, 2002) | To examine the transition from adolescence to adulthood for people with CF by taking an in-depth look at their perceptions of the process and experience of becoming an adult. | life stage or life cycle approach to human developme nt focusing on young adulthood and the transition from adolescence to adulthood | Convenience sample consisting of all CF patients between the ages of 20–28 who attended and lived near metropolitan CF Center. Participants were 2 males and 5 females with cystic fibrosis (CF), ages ranging from 20 to 26 years | Des, Qual | exploratory study using a qualitative in-depth interview design consisting of one- to-one semi-structured interviewing | Content analysis was used to identify themes and patterns after categorizing data by research question. The most frequent responses and similar themes were identified until reaching saturation. | Employment benefits, primarily health insurance, was also of primary concern for participants when considering a job. Stress. Most participants acknowledged the primary areas of stress were related to health insurance, finances and daily schedule, or the idea of needing to fit therapies and health care into a very busy time of life. 6 participants identified health coverage as a significant stress. Insurers refused to pay for equipment or medications. Having CF placed a significant stress on finances because of co-pays, deductibles, non-covered services, medications and nutritional requirements. Finances and insurance were not concerns until becoming an adult and assuming these responsibilities. All participants felt they were different from peers without CF in this aspect of transition. New Responsibilities. Most felt they had taken over responsibilities for health care such as scheduling clinic appointments, performing daily therapies and obtaining medications long before entering adulthood. None reported changing treatment regimens once they were on their own, but some described the need to take more initiative without a parent there reminding them to do therapies. |

Findings were exploratory and Could not be generalized to all young people with CF due to the small sample size and nonrandom sample. Life circumstances, health status, perceptions and experiences of participants may differ from non- participants. None had faced severe limitations, so their perceptions and experiences may not reflect those with advanced effects of CF. |

Indiv: Subj exp, Obj behav |

| (Patterson& Lanier, 1999) | To learn how a transition program could help adolescents and young adults make the transition from pediatric to adult health care by discerning adolescents’ transition experiences. | Not discussed | Providers sent introductory letters to: 1) adolescents age 18–22 with chronic illnesses or physical disabilities with cognitive ability who have thought of or are in the process of making the transition; and 2) young adults age 23–35 with chronic illnesses or physical isabilities with cognitive ability who believe they have made the transition 7 adolescents and young adults participated in focus groups |

Des, Qual | Focus group in 3 geographical areas of WA. The first focus group consisted of 3 female adolescents with chronic illnesses who received health care from pediatric providers. The second focus group consisted of 2 female young adults with chronic illnesses that began at birth. The third focus group included 2 male young adults with physical and developmental disabilities, which began at birth. | Content analysis methods were used in which the unit of analysis is a statement (or group of statements). A set of thematic categories was developed with a definition for each category; these were coded and three independent coders validated the codes. A grounded theory approach was used to develop themes and to organize the ideas that emerged. Data were analyzed by coding and constantly comparing codes. Segments of the text associated with a particular code or combination of codes were retrieved. Frequency tabulations for each category and code were computed across participants. | One overriding principle, that health care providers should feel comfortable caring for patients with disabilities, influenced all three themes.

|

The qualitative study results cannot be generalized to all teens and young adults with disabilities. | Indiv: Subj exp, Obj behav Micro: Fam, prov, peer Meso |

| (Powers, et al., 2007) | to obtain information directly from young people with disabilities about the importance of transition experiences considered effective and their opportunity to participate in them. To address study questions: from the perspective of youth with disabilities, how important for building a successful adult life are those transition practices identified as effective by professionals? How much do youth with disabilities participate in those practices that have been identified as effective? | participatory action reseach (PAR) empowerm ent approach | study was designed and conducted by 17 Governing Board members (GB) of the National Youth Leadership Network. GB members recruited youth with disabilities, aged 16 to 24, from local high schools, colleges, community organizations and programs, and their personal networks. Recruitment approaches emphasized administering the survey to a diverse cross-section of youth and youth who might typically not be invited to participate as research informants. 202 young people with disabilities living in 34 states and DC completed the survey |

Des, Quant, cross-section | survey tool was developed and piloted by the Research Committee, with support from researchers and federal agencies. 20 items included 17 important experiences for promoting, the transition from school to adult life. Experiences related to: self-determination, inclusive education, career development, postsecondary education, family support, accessing various services, ADA and IDEA, supports available to youth with disabilities, and transportation. The survey was piloted and revised | mean importance ratings and participation levels were calculated and rank ordered for each experience. Analysis of variance and Scheffe procedures were utilized to evaluate the impact of demographic variables on importance ratings and participation levels. Paired samples t tests were performed to compare youths’ importance ratings with their reported level of participation in each transition experience. Post hoc analyses were conducted using a Bonferroni procedure to control for multiple comparisons. | On a scale from 0 (not important) to 3 (very important), Have my family’s encouragement and help was the most important experience. learn how to stay healthy received a mean score of 2.64 and was 4th most important experience on the list. Get health insurance received a mean score of 2.55 and was the 8th most important experience. Get a good doctor who treats adults received a mean score of 2.5 and was the 10th most important experience. To examine level of participation, youth rated experiences on a scale from 0 (not much) to 3 (a lot). Have my family’s encouragement and help had the highest level of participation. Learn to stay healthy received a score of 2.22 and was 3rd on the list. Get a good doctor who treats adult received a rating of 1.67 and was 9th on the list. Get health insurance received a score of 1.66 and was 10th on the list. In comparison to older youth, participants aged 18 and younger reported that they had significantly less opportunity to get a good doctor who treats adults and learn how to stay healthy |

Methodological limitations include: response bias, use of a convenience sample, self-report, and instrumentation challenges. Response bias and the sample prevented generalizing to youth who did not participate in the study. The list of transition experiences did not include all validated effective practices |

Indiv: Obj behav |

| (Reiss, et al., 2005) | To describe transition experiences, promising practices that facilitate successful transition, obstacles that inhibit transition | Not discussed | Youth and young adults with disabilities or SHCNs, family members, and health care providers were recruited at children’s hospitals, outpatient clinics, treatment programs, community medical centers, and professional meetings. Inclusion criteria: 13–35 years, chronic disability or SHCN, treatment initiation before age 18. Family members were parents, guardians, grandparents, siblings, spouses. A total of 143 individuals participated in 34 focus groups held in 9 cities. |

Des, Qual | Focus groups and interviews (occasions when there was only 1 participant) were 60 to 90 minutes in length. Separate focus groups were held for youths and young adults, families, and providers. Focus groups were conducted with a standard protocol | After debriefing session and completing field notes, focus groups were transcribed verbatim. Content analysis of transcripts. A researcher coded transcripts and organized themes into 3 domains: stages of transition, health care systems, and transition narratives. Narrative analysis to understand the meanings of HCT and the beliefs held about the process was conducted on transition stories. |

2 factors had a significant effect on the process and outcomes of HCT: cognitive ability of the young adult and the progressive nature of the SHCN or disability. Participants viewed transition as a developmental process with 3 stages: 1. envisioning a future: Envisioning the child growing up to be an adult helped promote future planning. Plans changed as child’s abilities emerged over time. 2. age of responsibility: family members taught and gave responsibility to the child to carry out tasks of daily living and medical self-care. Examples included talking with providers, ordering and taking medications, and developing positive habits and routines. 3. age of transition: divided into 2 periods of adolescence and young adulthood. Maturity and experience were necessary to carry out successfully medical responsibilities. Participants noted differences in pediatric and adult-oriented systems that created barriers to transition. Four systems barrier are: 1. aging out; 2. insurance/funding; 3. availability of care: it was difficult to find A-OPs who matched pediatric providers in knowledge about, training in, and experience with disability or SHCN; 4. practice differences: organization of care, communication between pediatric providers and A-OPs, and family involvement |

Many disability/diagnoses were represented by the participants, but only a few individuals had experience with a given condition. Differences that exist in the transition experience of individuals who represent different conditions could not be identified or addressed. There was a preponderance of providers from pediatrics; thus, the perspective of adult providers was not well represented. |

Indiv: Person char, Subj exp, Obj behav Micro: Fam, prov Meso |

| (Scal, 2002) | To describe the range of approaches that represent transition services as they are undertaken in the offices of primary care physicians and to understand them in the context of the current proposed models. | Some survey questions based on social cognitive theory | Parents nominated primary care providers who facilitated the transition of medical care from the pediatric to the adult health care system. The Health Care Transition for Youth Digest electronic mailing list posted the nomination survey. 36 nominations, representing 35 unique health care providers, were received. Each nominee received an in-depth mail survey. 13 (37%) of the nominated health care providers completed surveys, but 3 were excluded. |