Abstract

Elective knee and hip joint replacements are cost-effective treatment options in the management of end-stage knee and hip osteoarthritis. Yet there are marked racial disparities in the utilization of this treatment even though the prevalence of knee and hip osteoarthritis does not vary greatly by race or ethnicity. This article briefly reviews the rationale for understanding this disparity, the evidence-base that supports the existence of racial or ethnic disparity as well as some known potential explanations. Also, briefly summarized here are the most recent original research articles that focus on race and ethnicity and total joint replacement in the management of chronic knee or hip pain and osteoarthritis. The article concludes with a call for more research, examining patient, provider and system-level factors that underlie this disparity and the design of evidence-based, targeted interventions to eliminate or reduce any inequities.

Keywords: joint replacement, variation, race, osteoarthritis, utilization

The Health Impact of Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis

Elective total knee or hip joint replacement is a treatment option for an important and high-impact clinical condition, end-stage osteoarthritis (OA). OA is the most prevalent form of arthritis and is among the most prevalent chronic conditions in the United States (US).1 It is estimated that nearly 70 million Americans, about one out of every three, are affected by arthritis or musculoskeletal diseases.2 The prevalence of lower extremity (knee or hip) OA increases with age. With the aging of the US population, the burden of OA is expected to increase. Data from the population-based Framingham Osteoarthritis study indicated that 33% of those over 65 had radiographic evidence of knee OA and 9.5% reported symptomatic OA.3 The rates of lower extremity OA among African-Americans is at least as high as those reported for whites.1, 4

IS JOINT REPLACEMENT AN EFFECTIVE TREATMENT OPTION FOR END-STAGE OSTEOARTHRITIS?

The evidence base for joint replacement as a treatment option for end-stage OA has been the subject of several National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus statements and evidence-based systematic reviews by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).5–8 The 2003 NIH consensus statement touted the effectiveness of knee joint replacement.5 The most recent AHRQ systematic review of more than 129 studies found that evidence supports the effectiveness of joint replacement as the primary surgical option for end-stage knee OA.7 The aforementioned substantial body of evidence pointing to the effectiveness and safety of joint replacement makes it one of the most commonly performed elective surgeries among the elderly. Because of the aging of the US population, joint replacement is expected to increase over the next few decades. By 2030, it is estimated that there will be an 85% increase in knee replacements alone.9 In fiscal year 2000, Medicare spent approximately $3.2 billion on joint replacements.7

THE EVIDENCE-BASE FOR RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN JOINT REPLACEMENT UTILIZATION

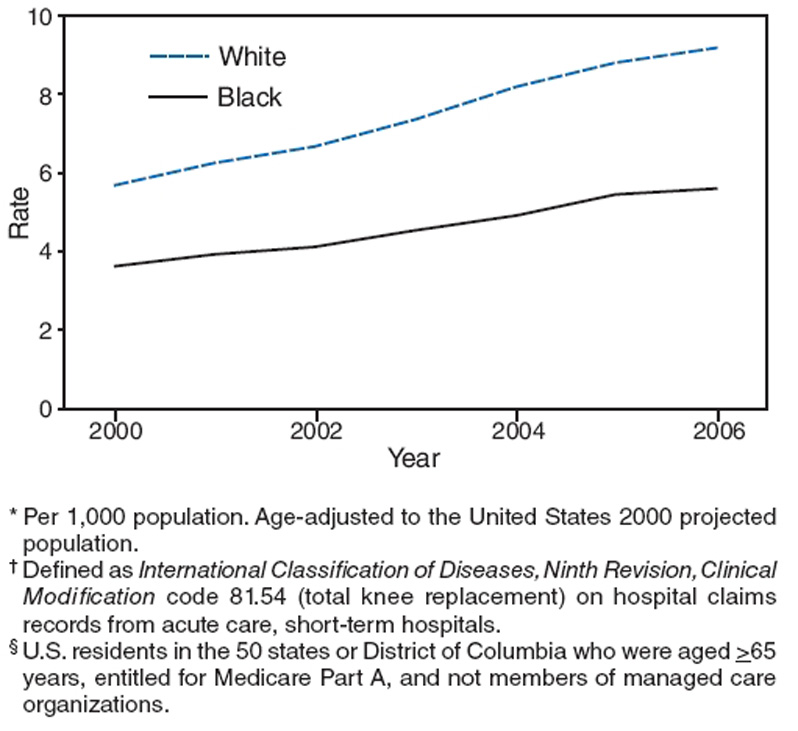

Numerous studies have documented the existence of racial or ethnic differences in knee and hip joint replacement over the past 10–15 years.10–17 Most recently, in the winter of 2009, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) released a report showing that racial disparity in knee replacement is not only persistent but potentially widening (Figure 1).18 Most of the studies that have documented this disparity have used Medicare data in which access to the procedure based on insurance status is not a significant issue. Wilson et al.13 studied Medicare hospital claims data from 1980 to 1988 and found that compared to African-American men, white men were 3.0 to 5.1 times more likely to undergo knee replacement.13 Escarce et al.10 examined 1989 Medicare data and found that whites compared with African-Americans were twice as likely to receive knee replacement.10 McBean and Gornick19 used the 1992 Medicare database to report an African-American to white odds ratio of 0.64 for undergoing knee replacement.

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted rates* of total knee replacement† among Medicare enrollees,§ by white or black race – United States, 2000–2006.

Reproduced with permission: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Racial disparities in total knee replacement among medicare enrollees - United States, 2000–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(6):133–138.

In a study published in 2003, Dunlop et al.20 reported that African-American and Hispanic individuals reported receiving joint replacement about two thirds less often than whites. They also found the odds of undergoing joint replacement among African-Americans and Hispanics to be 0.46 compared with whites after adjusting for access to insurance.20 These findings of racial or ethnic differences in joint replacement utilization have been replicated in studies using other databases including the National Health Interview Survey.10,12 Another in-depth examination of this disparity was published in the New England Journal of Medicine during the fall of 2003 by Skinner et al.21 Consistent with previous reports, they found African-American men to be markedly less likely than white men to undergo knee replacement even after adjusting for regional variations. Furthermore, studies have suggested that racial and ethnic disparities in the utilization of joint replacement are widening.6,11,22

REASONS FOR ETHNIC AND RACIAL DISPARITIES IN JOINT REPLACEMENT UTILIZATION

Disparities in joint replacement utilization represent one of many types of racial and ethnic disparities that exist across various health care conditions and settings.23–30 The reasons for these disparities are complex and involve patient-level, provider-level, and system-level factors. One potential etiologic mechanism for racial and ethnic disparity in health care is patient preferences, which should be addressed with educational intervention.31 Patient preferences have been reported to vary by race and ethnicity and to influence medical care utilization.32-34 A study funded by the Veteran’s Administration (VA) of African-American and white cultural beliefs and attitudes regarding knee and hip OA care and joint replacement as a treatment option found evidence that African-American patients are less willing to consider joint replacement.35,36 Figaro et al.37 used focus group methodology to examine African-American patients' attitudes and preferences regarding knee and hip arthritis care and joint replacement. They, too, found racial differences in attitudes and preferences regarding knee and hip OA and joint replacement.37 In a study that examined willingness to pay for knee replacement among a sample of patients in Houston, Texas, African-American and white participants differed significantly in their willingness to pay for knee replacement even after adjusting for age, income, educational level, and other factors.38

Patient preference also plays a role in joint replacement utilization even in less racially diverse settings. For instance, one study reported that variation in joint replacement utilization in two different geographic areas in Toronto, Canada could be explained in part by differences in patient preference.39 Overall, preferences for joint replacement among potential candidates with demonstrable indications was low (10%) in this population-based sample.40 This finding was also confirmed in another study conducted in England, which found lower preferences for joint replacement than would be expected among those who met criteria for surgery.41 These studies, though not designed to examine racial disparities, suggested that there is substantial underutilization of joint replacement based in part on patient preference.

DO EXPECTATIONS ON SURGICAL OUTCOME SHAPE PATIENT PREFERENCE?

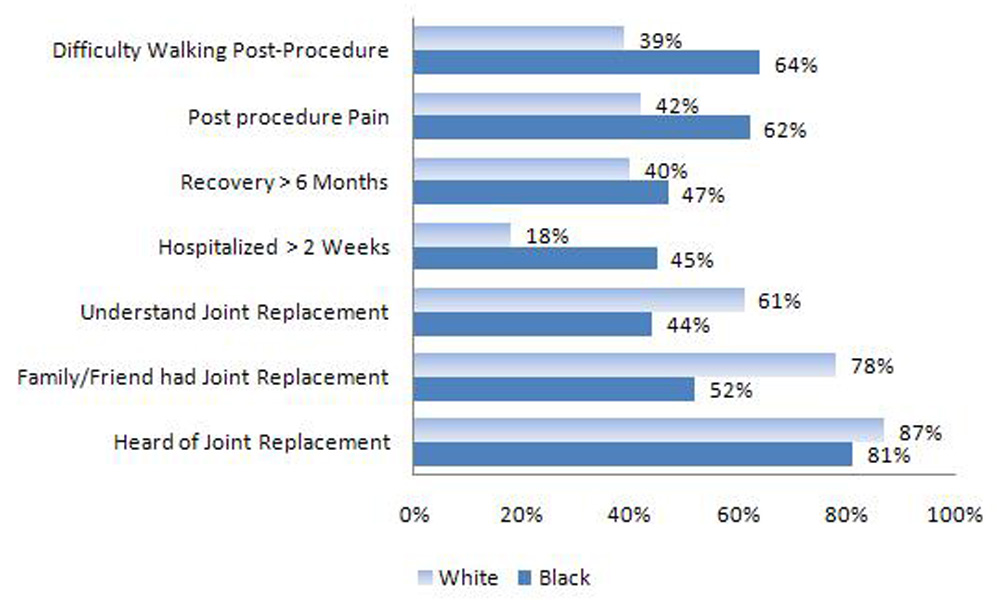

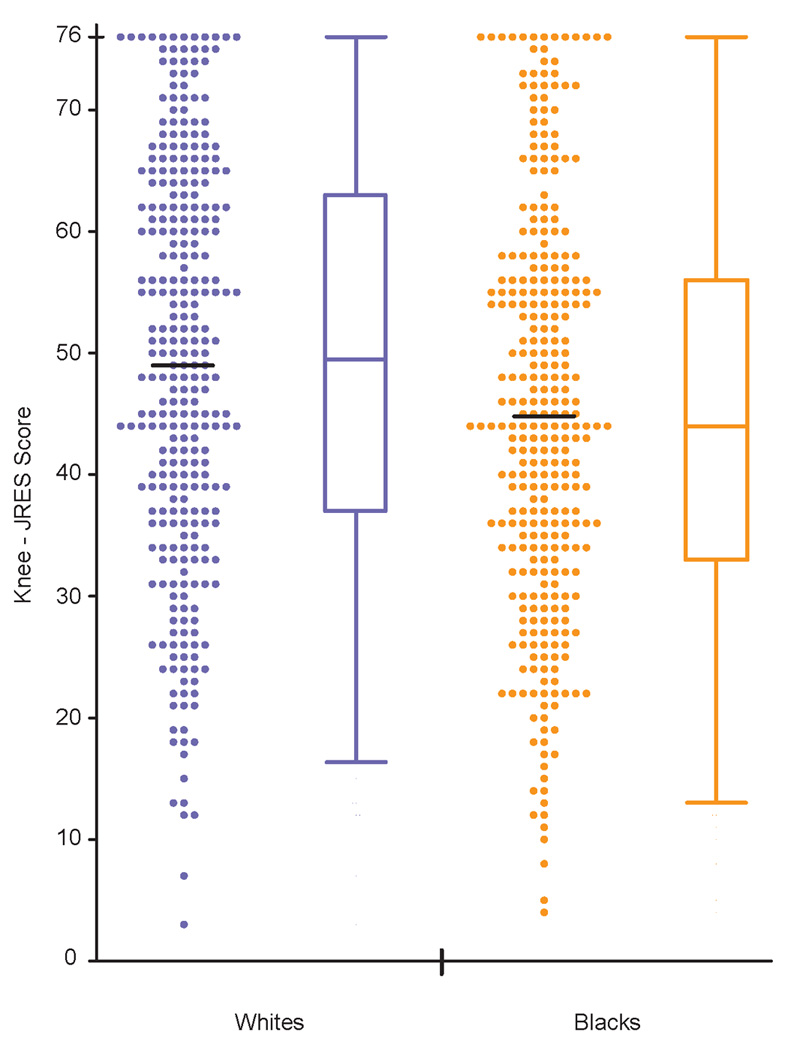

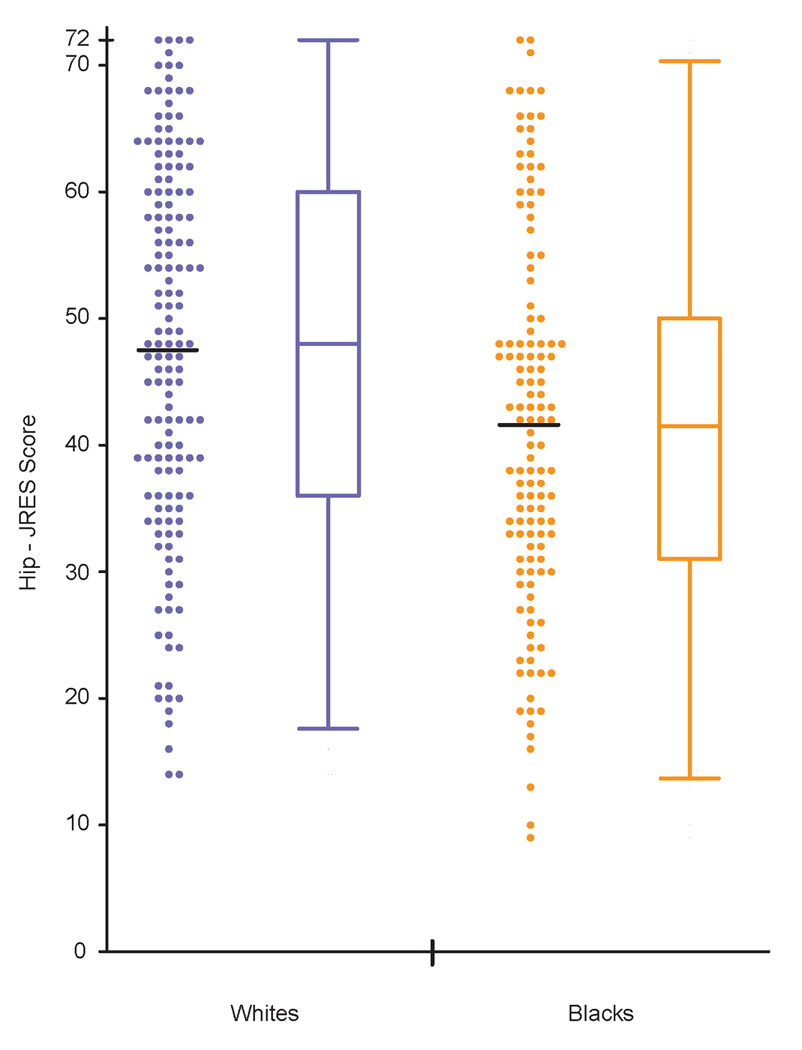

Patient preference is in part an attitudinal disposition. The Expectancy-Value Model42 is the most common conceptualization of attitude. According to this model, attitudes arise spontaneously and inevitably as we form beliefs about an object or goal.43 Beliefs associate objects or goals with certain attributes such that a person’s overall attitude toward that object or goal is determined by the subjective value of the object’s attributes in relation to the depth of the association.43 Shah and Higgins examined the interaction of expectancies and values, key concepts of attitude formation, and found that positive expectancies (i.e., joint replacement surgery will reduce pain and improve function) and values such as religiosity generally predict commitment toward an object or goal. In a study of African-American and white patients receiving primary care at the Veterans Administration Hospital (VA) who were potential candidates for joint replacement, racial variations in patient expectations regarding the risk and benefits of joint surgery were examined. African-American patients expressed more concerns about surgical outcomes compared with white patients (Figure 2)36 and were more concerned about walking and postoperative pain. They were more likely to think that the surgery involves extended hospitalization and recovery time. They also were less likely to have a good understanding of joint replacement or to have a friend or relative who had the treatment. However, more importantly, patient expectations regarding surgical outcomes explained a larger component of racial differences in patient preference regarding joint replacement.36 In a more recent and larger study of African-American and white primary care patients, Groenveld et al.48 examined patient expectations regarding joint replacement using the Hospital for Special Surgery Hospital Joint Replacement Expectations Survey (JRES), a validated measure of postsurgical expectations among patients with osteoarthritis who are contemplating surgery.45–47 They too found marked racial differences in patient expectations regarding joint replacement surgical outcomes (Figure 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Expectations and knowledge about joint replacement.

(Reproduced with permission: Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Understanding ethnic differences in the utilization of joint replacement for osteoarthritis: the role of patient-level factors. Med Care. 2002;40(1 Suppl):I44-I51.)

Figure 3.

Patient race and surgical outcome expectations regarding knee replacement.

(Reproduced with permission: Groeneveld PW, Kwoh CK, Mor MK, et al. Racial differences in expectations of joint replacement surgery outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. May 15 2008;59(5):730–737.)

Figure 4.

Patient race and surgical outcome expectations regarding hip replacement.

(Reproduced with permission: Groeneveld PW, Kwoh CK, Mor MK, et al. Racial differences in expectations of joint replacement surgery outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. May 15 2008;59(5):730–737.)

A REVIEW OF MOST RECENT LITERATURE

Summarized below are key findings from the most recent original research that discusses racial and ethnic variations in the utilization of total joint replacement and possible explanations. This is not a systematic review, but rather a focused sampling from Medline-indexed health care journals for all original research publications in this area between January 2008 and September 2009. The articles represent only original research and are presented in a chronological order.

Ang et al.49 conducted a cross-sectional, observational study of 684 patients who were potential candidates for total joint arthroplasty (TJA). The authors used a validated TJA appropriateness algorithm and other clinical measures of joint arthroplasty indications and contra-indications such as the WOMAC index score, Charlson comorbidity, age, and body mass index to examine the proportion of patients who are clinically appropriate for consideration of TJA. They compared African-American patients with white patients in the sample. This study found no racial differences in clinical appropriateness for TJA.

To monitor the progress of Healthy People 2010, which calls for the elimination of racial disparities in the rate of total knee replacement among persons ages 65 years or older, the Center for Disease Control18 analyzed national and state total knee replacement rates for Medicare enrollees for the period 2000 through 2006. This analysis stratified the sample by sex, age group and by race (black or white). The results of this analysis showed that from 2000 to 2006, the rate of TKA increased overall by 58%. The rate increases were similar for white and African-American patients. However, in 2000, the rates for African-American patients were 38% lower than the rates for white patients. In 2006, the African-American rates were 39% lower than white rates. Essentially, the utilization rate of this treatment is increasing nationally for all patients; however, the racial gap remains unchanged.

Jones et al.50 examined the relationship of the patient race and pain coping strategies in a sample of patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis. The study surveyed 939 VA patients (ages 50–79 years) who were receiving primary care. The study found racial differences in pain coping strategies. For instance, African-American patients compared with white patients were more likely to report believing and using prayer to self-treat knee or hip pain. The authors speculated, but did not directly assess, whether variations in pain coping strategies underlie the observed studies in the knee or hip the total joint arthroplasty utilization.

Ghandi et al.51 surveyed 1,609 patients undergoing primary total knee or hip joint arthroplasty. They assessed patients risk perception and found that patients of non-European descent had greater perception of surgical risk compared with those of European descent. However, they also had greater functional disability and pain prior to surgery.

Steel et al.52 used data from the US Health and Retirement Study to assess the need for total joint arthroplasty in a sample of 14,807 patients, ages 60 and older, from 1998, 2000 and 2002. The authors assessed prospectively the receipt of total joint arthroplasty over a 2-year period. They found that minority patients, such as African-Americans, were significantly less likely to receive needed TJA compared with white patients. Another important predictor of less utilization was educational level, with patients of lower education receiving fewer total joint arthroplasties.

Groenveld et al.53 examined patient expectations regarding knee or hip replacement using established means of expectation and compared African-American patients with white patients with similar disease severity level and clinical indications. The sample consisted of 909 VA primary care patients between the ages of 50 and 79 years. African-American patients were found to have significantly lower levels of expectations for surgical outcomes compared with similar white patients. These racial differences in expectations were not explained by differences in age, disease severity, educational level, income, trusts in the physician, or social support.

Soohoo et al.54 examined discharge data from patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty in California from 1991 to 2001. They examined the utilization of low, moderate or high-volume hospitals comparing minority patients with non-minority patients. They analyzed a total of 222,684 primary total knee arthroplasty cases. They found African-American, Hispanic and other minority patients to be significantly more likely to receive TKA at low volume centers or hospitals. They also found Medicaid insurance to be a predictor of receiving TKA at low-volume hospitals or centers.

Hanchate et al.55 used the US Longitudinal Health and Retirement Study database to examine the relationship between patient race or ethnicity and receipt of TKA. They found African-American men to be significantly less likely to undergo TKA even after adjusting for economic factors. They also found that being uninsured was a negative predictor of undergoing TKA compared to those with Medicaid insurance. The authors concluded that insurance coverage and financial constraints explain some of the racial or ethnic variations in total knee arthroplasty rates.

Levinson et al.56 examined the content and pattern of informed decision-making model (IDM) between orthopaedic surgeons and elderly white and African-American patients. They also assessed the relationship between patients' race and their satisfaction with surgeon communication. Eighty-nine orthopaedic surgeons and 886 patients ages 60 years or older participated in this observational study. This study found no significant racial differences in the content of the nine IDM elements. However, coder-rated responsiveness, respect and listening components of the communications were less frequent among African-American patients compared with white patients. Moreover, compared to white patients, African-American patients were less satisfied with their communication with the orthopaedic surgeon.

Dunlop et al.57 used the US Longitudinal Health and Retirement Study database to examine self-reported 2-year use of arthritis-related hip and knee surgery for a sample of 2,262 African-Americans, 1,292 Hispanics, and 15,159 whites ages 51 years and older. The study found lower rates of arthritis-related surgeries for African-American and Hispanic patients compared with white patients. However, these differences where less pronounced for patients younger than 65 years of age and access to care explained the lower utilization rates for Hispanic patients.

Conclusion

In summary, racial and ethnic variations in joint replacement for the management of end-stage knee or hip OA remain persistent. Growing research examines the potential reasons. The focus of this research ranges from patient level factors, such as preference or expectations of surgical outcomes, to system-level factors such as health insurance and access to care, to interpersonal factors such as doctor-patient communication style and pattern. More research that can take what has been learned about this disparity thus far and apply it in the designs of interventions that target not only the system, but also patient-level factors as well as doctor-patient communications and decision-making is needed.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Kimberly Hansen for editorial assistance.

Dr. Ibrahim is supported by grant number K24AR055259 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest published during the annual period of review have bee, noted as : * of special interest ** of outstanding interest.

- 1.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman RD, Hochberg MC, Moskowitz RW, Schnitzer TJ. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1905–1915. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1905::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felson DT. The epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham osteoarthritis study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1990;20:42–50. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(90)90046-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan J, Linder G, Renner J, Fryer J. The impact of arthritis in rural populations. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:242–250. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Eye Institute, National Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences. Health disparities in rheumatic, musculoskeletal and skin diseases. 2003 http://grants1.nih.gov//grants/guide/pa-files/PA-03-054.html.

- 6.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Trends in hospital procedures performed on black patients and white patients. 1980–1987: AHCPR. 1994 Publication No. #94-0003.

- 7.Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, et al. Total knee replacement. evidence report/technology assessment no. 86 (prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center, Minneapolis, MN) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003. AHRQ Publication No. 04-E0006-2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institutes of Health. NIH consensus conference: total hip replacement. NIH consensus development panel on total hip replacement. JAMA. 1995;273:1950–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mamlin LA, Melfi CA, Parchman ML, et al. Management of osteoarthritis of the knee by primary care physicians. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:563–567. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escarce JJ, Epstein KR, Colby DC, Schwartz RP. Racial difference in elderly's use of medical procedures and diagnostic tests. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:948–954. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.7.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron BJ, Barrett J, Katz JN, Liang MH. Total hip arthroplasty: use and select complications in the U.S. Medicare population. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:70–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharkness C, Hamburger S, Moore R, Kaczmarek R. Prevalence of artificial hip implants and use of health services by recipients. Public Health Rep. 1993;106:70–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson MG, May DS, Kelly JJ. Racial differences in the use of total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis among older Americans. Ethn Dis. 1994;4:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoagland FT, Oishi CS, Gialamas GG. Extreme variations in racial rates of total hip arthroplasty for primary coxarthrosis: a population-based study in San Francisco. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:107–110. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz BP, Freund DA, Heck DA, et al. Demographic variation in the rate of knee replacement: a multi-year analysis. Health Serv Res. 1996;31:125–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giacomini M. Gender and ethnic differences in hospital based procedure utilization in California. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1217–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escalante A, Espinosa-Morales R, Del Rincon I, Arroyo R, Older S. Recipients of hip replacement for arthritis are less likely to be Hispanic, independent of access to health care and socioeconomic status. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:390–399. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<390::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Racial disparities in total knee replacement among medicare enrollees - United States, 2000–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(6):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBean AM, Gornick M. Differences by race in the rates of procedures performed in hospitals for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 1994;15:77–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlop DD, Song J, Manheim LM, Chang RW. Racial disparities in joint replacement use among older adults. Med Care. 2003;41:288–298. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044908.25275.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, Wennberg JE. Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in rates of knee arthroplasty among medicare patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1350–1359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahomed N, Barrett J, Katz J, et al. Rates and outcomes of priimary and revision total hip replacement in the United States Medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85(A):27–32. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good CB, Lofgren RP. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical System. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:621–627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308263290907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson ED, Wright SM, Daley J, Thibault GE. Racial variation in cardiac procedure use and survival following acute myocardial infarction in the Department of Veterans Administration. JAMA. 1994;271:1175–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg KC, Hatz AJ, Jacobsen SJ, Krakauer H, Rimm AA. Racial and community factors influencing coronary artery bypass graft surgery for all 1986 medicare patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blendon RJ, Aiken LH, Freeman HE, Corey CR. Access to medical care for black and white Americans. a matter of continuing concern. JAMA. 1989;261:278–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayanian JZ, Udvarhelyi IS, Gastonis CA, Pashos CL, Epstein AM. Racial differences in the use of revascularization procedures after coronary angioplasty. JAMA. 1993;269:2642–2646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hannan E, Kilburn HJ, O'Donnell JF, Lukacik G, Shields EP. Interracial access to selected cardiac procedures for patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease in New York State. Med Care. 1991;29:430–441. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peterson ED, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, et al. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularization procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? N Engl J Med. 1997;336:480–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conigliaro J, Whittle J, Good BG, et al. Understanding racial variation in the use of coronary revascularization procedures: the role of clinical factors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1329–1335. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:146–152. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayanian J, Cleary P, Weissman J, Epstein A. The effect of patients' preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1661–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911253412206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannan E, van Ryn M, Burke JE, et al. Access to coronary artery bypass surgery by race/ethnicity and gender among patients who are appropriate for surgery. Med Care. 1999;37:68–77. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon HS, Paterniti DA, Wray NP. Impact of patient refusal on racial/ethnic variation in the use of invasive cardiac procedures. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17 (Suppl 1):159. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Siminoff LA, Kwoh CK. Variation in perceptions of treatment and self-care practices in elderly with osteoarthritis: a comparison between African-American and white patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:340–345. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<340::AID-ART346>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ibrahim SA, Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Kwoh CK. Understanding ethnic differences in the utilization of joint replacement for osteoarthritis: the role of patient-level factors. Med Care. 2002;40 (1 Suppl):I44–I51. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Figaro MK, Russo PW, Allegrante JP. Preferences for arthritis care among urban African Americans: "I don't want to be cut". Health Psychol. 2004;23:324–329. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrne MM, O'Malley KJ, Suarez-Almazor ME. Ethnic differences in health preferences: analysis using willingness-to-pay. J Rheum. 2004;31:1811–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Determining the need for hip and knee arthroplasty: the role of clinical severity and patients' preferences. Med Care. 2001;39(3):206–216. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1016–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juni P, Dieppe PA, Donovan J, et al. Population requirement for primary knee replacement surgery: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatology. 2003;42(2):516–521. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feather NT, editor. Expectations and actions: expectancy-value models in psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitudes and the attitude-behavior relation: reasoned and automatic processes. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European review of social psychology. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah J, Higgins ET. Expectancy x value effects: regulatory focus as determinant of magnitude and direction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:447–458. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mancuso CA, Salvati EA, Johanson NA, Peterson MGE, Charlson M. Patients' expectations and satisfaction with total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12(4):387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Salvati EA. Patients with poor preoperative functional status have high expectations of total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003 Oct;18(7):872–878. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Wickiewicz TL. Patients' expectations of knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83(A):1005–1012. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Groeneveld PW, Kwoh CK, Mor MK, et al. Racial differences in expectations of joint replacement surgery outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(5):730–737. doi: 10.1002/art.23565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ang DC, Tahir N, Hanif H, Tong Y, Ibrahim SA. African-Americans and whites are equally appropriate to be considered for total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2009 Sept;36(9):1971–1976. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones AC, Kwoh CK, Groeneveld PW, et al. Investigating racial differences in coping with chronic osteoarthritis pain. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2008 Dec;23(4):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gandhi R, Razak F, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Ethnicity and patient's perception of risk in joint replacement surgery. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(8):1664–1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steel N, Clark A, Lang IA, Wallace RB, Melzer D. Racial disparities in receipt of hip and knee joint replacements are not explained by need: The Health and Retirement Study 1998–2004. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(6):629–634. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groeneveld PW, Kwoh CK, Mor MK, et al. African-American patients have lower levels of surgical expectations compared to white patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(5):730–737. doi: 10.1002/art.23565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soohoo NF, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for total knee replacement. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(5):559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hanchate AD, Zhang Y, Felson DT, Ash AS. Exploring the determinants of racial and ethnic disparities in total knee arthroplasty. Health insurance, income, and assets. Med Care. 2008 May;46(5):481–488. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181621e9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levinson W, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, et al. "It is not what you say": Racial disparities in communication between orthopedic surgeons and patients. Med Care. 2008 Apr;46(4):410–416. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815f5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunlop DD, Manhim LM, Song J, et al. Age and racial/ethnic disparities in arthritis-related hip and knee surgeries. Med Care. 2008 Feb;46(2):200–208. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815cecd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]