Introduction

Angiomyomatous hamartoma (AMH) of the lymph node (LN) is a benign vascular disorder of unknown etiology, first described by Chan et al. in 1991, as a distinctive lesion of LN characterized by parenchymal replacement by blood vessels, smooth muscle and fibrous tissue in the absence of cellular fascicle formation.1 This rare disease particularly involves inguinal and femoral lymph nodes,1–6 however, one report of cervical LN involvement has been reported.7 A single case of popliteal LN involvement has also been reported.8 To the best of our knowledge, only 17 cases of AMH of LN have been reported in the literature.2 We present a case of AMH of the inguinal LN in an 82-year old male.

Case Report

An 82-year old male patient presented with a left inguinal mass and associated ipsilateral lower limb edema of two years duration. Computerized tomography (CT) revealed multiple enlarged lymph nodes throughout the abdomen. Macroscopically, the inguinal mass measured 3×2×1 cm. On cut section, it had a firm gray-white appearance. Microscopically, it represented a lymph node, the parenchyma of which was almost completely replaced from hilum to cortex by fibrous tissue containing numerous irregular blood vessels, interspersed spindle cells and few lobules comprised of benign adipocytes. These changes gradually extended from the hilum to the convex surface of the LN (Figure 1), leaving only a thin rim of cortical lymphoid tissue containing a few residual atrophic follicles (Figure 2). The capsule was thickened and no subcapsular or medullary sinuses were found. While the hilum contained thick-walled muscular vessels, the cortex was mainly rich in capillary like vessels. Towards the cortex, the vessels became more dispersed and associated with smooth muscle cells, eventually splaying into the sclerotic stroma. The fibrous tissue consisted of spindle shaped cells with regular elongated nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm, dispersed haphazardly around vascular structures (Figures 3, 4 and 5). A few interspersed islands of adipocytes were also seen (Figures 6 and 7). Cellular pleomorphism, conspicuous mitoses and necrosis were absent. Immunohistochemistry (Streptavidinbiotin- complex), showed a strong reactivity for alpha smooth muscle actin (ASMA) and Desmin in the spindle shaped cells dispersed throughout the fibrous tissue and highlighted the muscular nature of the blood vessels, especially present in the LN hilum (Figure 8). The blood vessels were decorated by CD 34 (Figure 9). The histological appearances, supported by immunohistochemistry, led to the diagnosis of AMH of LN. On account of the entirely benign nature of this condition extensive resection was not required and the patient is doing well six months after the surgery, although the lymphedema did not regress completely.

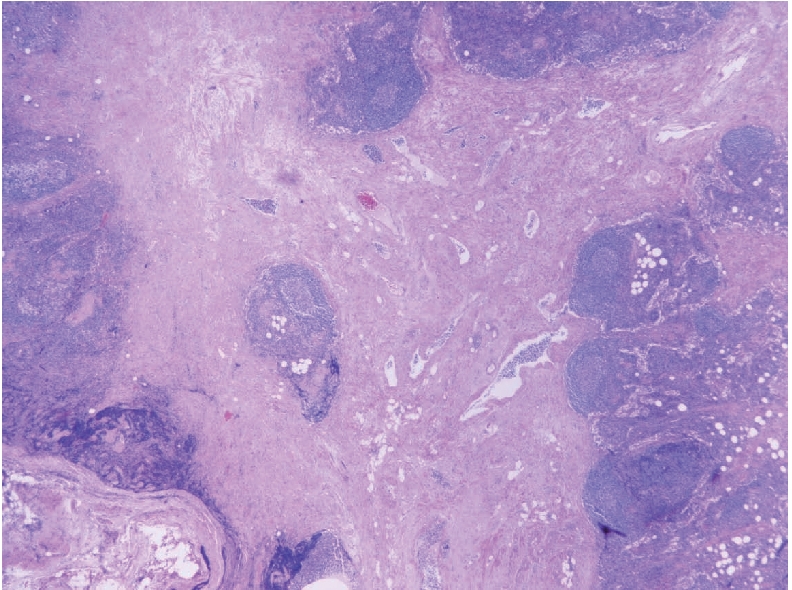

Figure 1.

Microphotograph showing low power view of angiomyomatous hamartoma, including smooth muscle bundles admixed with fibrous tissue and blood vessels, extending from the lymph node hilum (lower part) to cortical lymphoid follicles (upper and right side) (H&E ×40).

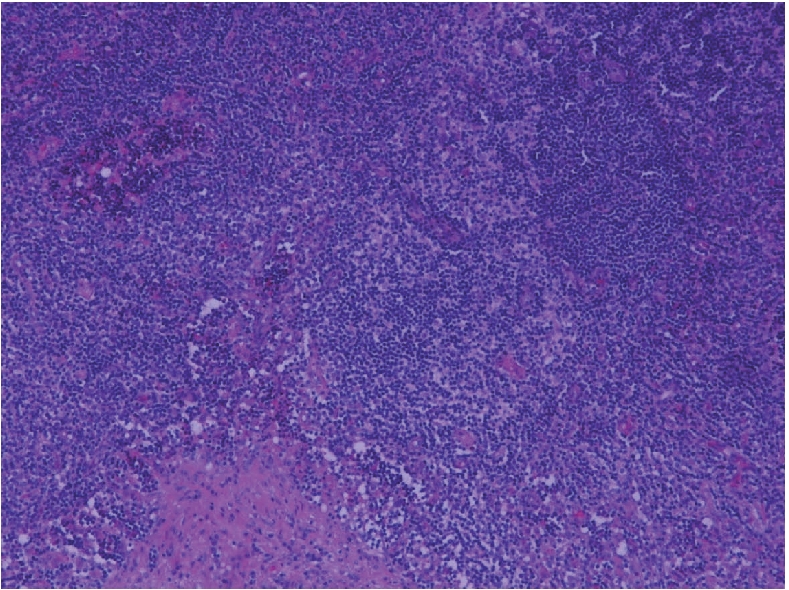

Figure 2.

Microphotograph showing a few residual lymphoid follicles (upper part) with underlying smooth muscle (lower part) (H&E ×200).

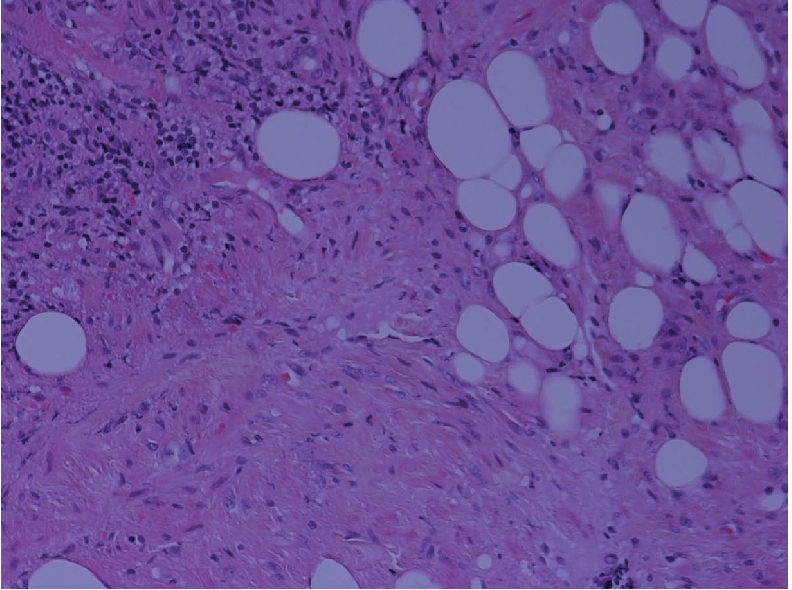

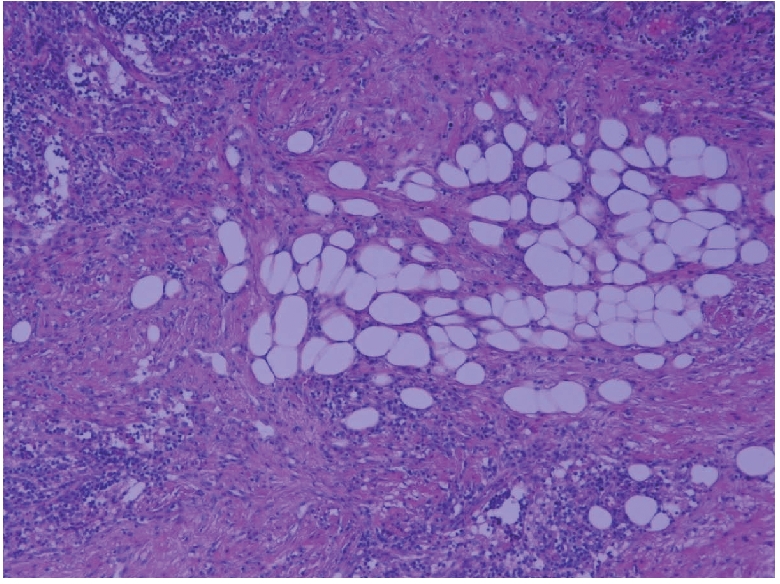

Figure 3.

Microphotograph showing all the elements of angiomyomatous hamartoma: smooth muscle, fibrous tissue, adipose tissue and blood vessels with a disorganised growth pattern (H&E ×200).

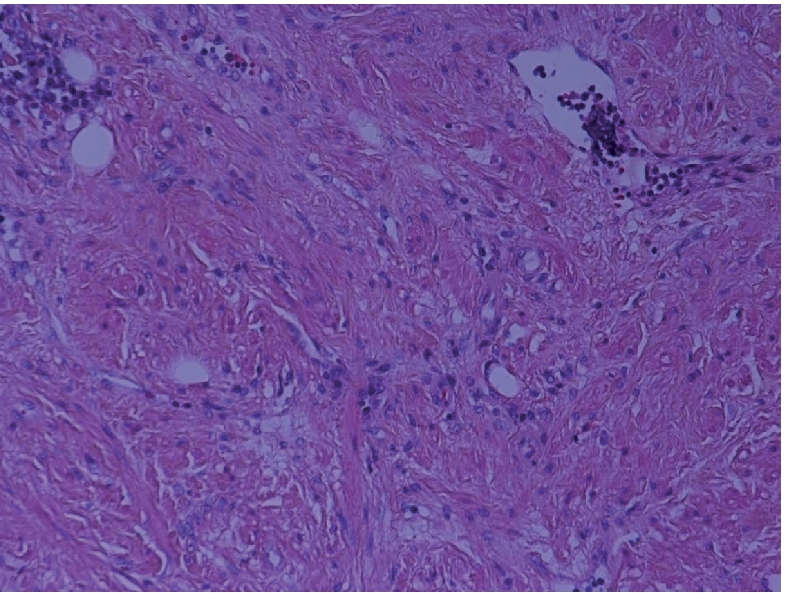

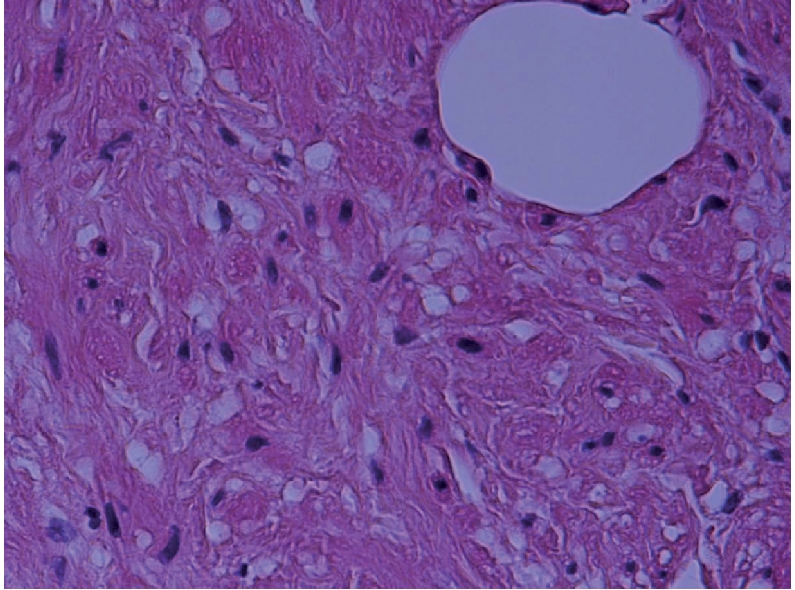

Figure 4.

Microphotograph showing smooth muscle fibres containing benign spindle cells, together with variably sized blood vessels in a background of fibrous tissue (H&E ×200).

Figure 5.

Microphotograph showing high power view of benign spindle cells in the smooth muscle, with a large benign adipocyte (upper right) (H&E ×400).

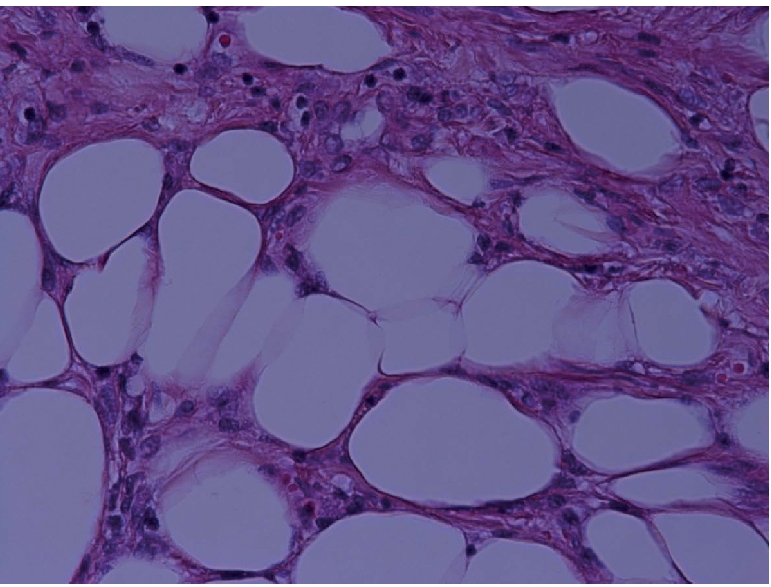

Figure 6.

Microphotograph showing benign adipocyte lobules amidst smooth muscle (H&E ×200).

Figure 7.

Microphotograph showing high power view of benign adipocyte lobules (H&E ×400).

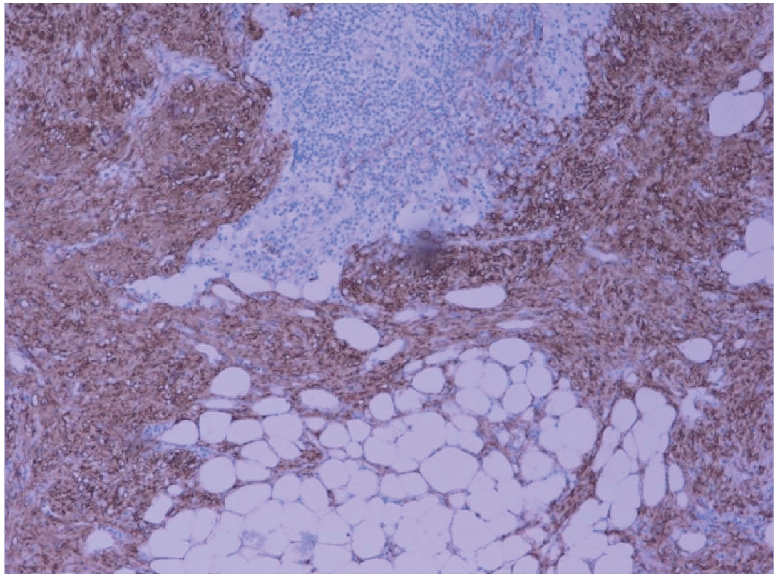

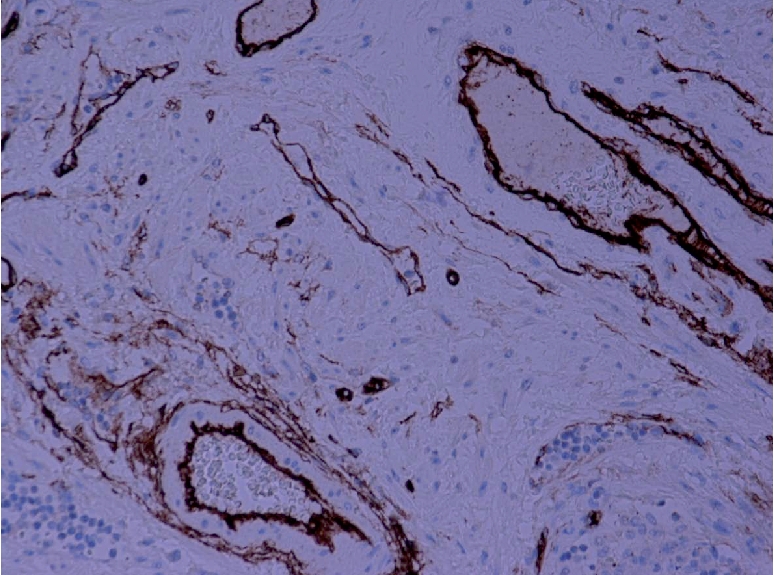

Figure 8.

Microphotograph showing positive immunostaining of smooth muscle by desmin (H&DAB ×200).

Figure 9.

Microphotograph showing positive immunostaining of blood vessels by CD34 (H&DAB ×200).

Discussion

In a study conducted to investigate the morphological and clinical findings of various primary vascular tumors of lymph nodes other than Kaposi's sarcoma, Chan et al. used the term “angiomyomatous hamartoma” to describe a distinctive clinico-pathological lesion occurring in lymph nodes.1 AMH seems to be a rare nodal condition as only 17 cases have been reported in the literature so far.1,5,7 There is a tendency for AMH to occur in inguinal lymph nodes, although a few cases have been reported in femoral lymph nodes.1–6 Isolated cases (one each) have also been reported in the cervical and popliteal lymph nodes.7,8 Laeng et al. were the first to report an angiomyomatous hamartoma with a hemangiomatoid component and vascular transformation of sinuses in the same LN.7 Their report of a cervical LN was also the first report of an AMH outside of the inguinal or femoral nodes. We report another case of AMH of the inguinal LN in an 82-year old male. We re-confirm the predilection of this lesion to occur in inguinal lymph nodes, which may be related to the fact that this is also the most frequent site of other nodal mesenchymal tumors.9,10 Histologically, it was characterized by an extensive replacement of nodal parenchyma, from hilum to cortex, by a haphazard mixture of smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue and blood vessels within a fibrous stroma. Differential diagnoses include nodal lymphangiomyomatosis, leiomyomatosis and angiomyolipoma of the LN.1,11 Nodal lymphangiomyomatosis occurs exclusively in women, involves thoracic and abdominal lymph nodes and is histologically characterized by the presence of smooth muscle cells forming fascicles and sheets around anastomosing ectatic vascular spaces, resulting in a pericytomatous pattern.11 Moreover, in nodal lymphangiomyomatosis, smooth muscle cells are plumper, with lighter/clear cytoplasm and sclerosis is absent.1 Nodal leiomyomatosis, which affects intra-abdominal lymph nodes morphologically resembles extensive leiomyoma and is composed of a proliferation of compact bundles of smooth muscle cells with an insignificant vascular component.11 An association with HIV/ immunodeficiency has also been reported.12 Angiomyolipoma of the LN usually affects retroperitoneal lymph nodes and is considered as being a manifestation of multicentricity of angiomyolipoma of the kidney.11 The smooth muscle cells of angiomyolipoma usually show an epithelioid appearance, hypercellularity, pleomorphism, prominent perivascular arrangement and positivity for melanoma associated antigen HMB-45.13 The histogenesis of AMH of LN is still unclear.3 In the original description, the hamartomatous nature was postulated on the basis of a disorganized growth pattern of smooth muscle cells and blood vessels.1 A significant adipose tissue component within a mixture of smooth muscle cells and blood vessels in AMH of LN may provide morphological evidence of the hamartomatous nature of the lesion. The close association of adipose tissue with smooth muscle cells and muscular blood vessels from the hilar region to the cortex indicates that adipose tissue may be a true component of hamartoma,5 further supported by the fact that AMH is a pathological condition starting in the hilum and extending towards the cortex.1 Adipose cells are known to occur as a significant component in a number of vaso-proliferative lesions, such as nodal hemangioma, intramuscular hemangioma (infiltrative angiolipoma) and angiolipomatous hamartoma associated with Castleman's disease.1,14,15 It has been suggested that all cases of AMH of the LN with a signficant adipose tissue component should be termed angiomyolipomatous hamartoma.3 However, the possibility that the lesion may represent a hemangioma with a prominent smooth muscle component or a reparative reaction to nodal inflammation cannot be ruled out.1 Some peculiar alterations of the lymph node vascular supply have been described, including increased numbers of small blood vessels with thickened walls and formation of plexiform or glomeruloid structures, such as in primary pulmonary hypertension and glioblastoma multiforme.6 Such similarities suggest that AMH of LN actually represents a disordered angiogenic process arising from hilar blood vessels, presumably the hilar vein and its branches.6 Further, the destruction of nodal sinuses by all these vascular and stromal alterations impairs the lymphatic circulation across the affected lymph node, explaining the occurrence of lymphedema in some patients.1,6 Sukarai et al. suggested that impairment of lymphatic flow may be one factor related to the pathogenesis of AMH.4 According to them, the process appears to start in the hilum and extends towards the cortex, causing normal lymphatic tissue to become displaced and atrophic. Recently, Piedimonte et al. described a third case in the literature in which a patient presented with a left sided inguinal mass, ipsilateral lymphedema of the leg and AMH.2 Our patient's lymphedema did not regress after excision of the AMH, similar to the case described by Piedimonte.2 Possible explanations for this discrepancy are that AMH may represent a localized malformation in a congenitally damaged lymphatic system. An alternative possibility is that chronic impairment of lymphatic flow results in the development of an AMH.2 The abnormal lymphatic flow has been revealed by examination of the radionuclide lymphoscintigram.6 There are speculations about whether the interference of lymph flow is the cause or the effect of AMH, which have to be determined.4 The unique features of our case are as follows: 1) to the best of our knowledge, this is only the eighteenth case of AMH reported so far in the literature;2 2) it is the fourth case in the literature in which the patient presented with a left inguinal mass, ipsilateral lymphedema of the leg and AMH; 3) all the previous 17 cases have been reported in the age range from 10–80 years (mean age, 47 years)1,3,4,7 whereas our patient is 82-years old. To conclude, although AMH of lymph node is very rare, its recognition is important for differential diagnoses from angiomatous benign and malignant tumors of lymph nodes. Recurrences and metastases of AMH have not been reported,1,3,5,7 except for a single occurrence of a secondary lesion after tumor resection, which was presumably due to impaired lymphatic transport.4 Hence, keeping in mind the hamartomatous nature of AMH, in our patient extensive resection was not needed. Our patient is doing well, six months after the LN excision.

Acknowledgement

we would like to thank Dr. Adu-Poku Kwame and Toni-Ann Robinson for their assistance.

References

- 1.Chan JKC, Frizzera G, Fletcher CDM, et al. Primary vascular tumours of lymph nodes other than Kaposi's sarcoma – analysis of 39 cases and delineation of two new entities. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:335–50. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piedimonte A, Nictolis MD, Lorenzini P, et al. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of inguinal lymph nodes. Plastic & Recon Surg. 2006;117:714–6. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000197912.09044.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magro G, Grasso S. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph node: Case report with adipose tissue component. Gen & Diagn Pathol. 1997;143:247–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakurai Y, Shoji M, Matsubara T, et al. Angiomyomatous hamartoma and associated stromal lesions in the right inguinal lymph node: A case report. Pathol Int. 2000;50:655–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen PW, Hoffman GJ. Fat in angiomyomatous hamartoma of lymph node. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:748–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199307000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dargent JL, Lespagnard L, Verdebout JM, et al. Glomeruloid microvascular proliferation in angiomyomatous hamartoma of the lymph node. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:320–2. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laeng RH, Hotz MA, Borisch B. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of a cervical lymph node combined with haemangiomatoids and vascular transformation of sinuses. Histopathol. 1996;29:80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauro CS, McGough RL, Rao UNM. Angiomyomatous hamartoma of a popliteal lymph node: an unusual cause of posterior knee pain. Ann of Diagn Pathol. 2008;12:372–4. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suster S, Rosai J. Intranodal haemorrhagic spindle-cell tumour with ‘amianthoid’ fibres: report of six cases of a distinctive mesenchymal neoplasm of the inguinal region that simulates Kaposi's sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:347–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss SW, Gnepp DR, Bratthauer GL. Palisaded myofibroblastoma: a benign mesenchymal tumour of lymph node. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warnke RA, Weiss LM, Chan JKC, et al. Atlas of Tumour Pathology. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Washington, USA: 1995. Tumours of the lymph nodes and spleen, 3rd series; pp. 437–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starasoler L, Vuitch F, Albores-Saavedra J. Intranodal leiomyoma. Another distinctive primary spindle cell neoplasm of lymph node. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;97:896–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/95.6.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullu Y, Gun S, Dabak N, et al. Angiomyomatous hamartoma in the inguinal lymph node: a case report. Turk J Pathol. 2006;22:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen PW, Enzinger FM. Haemangioma of skeletal muscle, an analysis of 89 cases. Cancer. 1972;29:8–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<8::aid-cncr2820290103>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madero S, Onate J, Garzon A. Giant lymph node hyperplasia in an angiolipomatous mediastinal mass. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:853–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]