Abstract

Studies report that women use as much or more physical intimate partner violence (IPV) as men. Most of these studies measure IPV by counting the number of IPV acts over a specified time period, but counting acts captures only one aspect of this complex phenomenon. To inform interventions, women’s motivations for using IPV must be understood. A systematic review therefore was conducted to summarize evidence regarding women’s motivations for the use of physical IPV in heterosexual relationships. Four published literature databases were searched, and. articles that met inclusion criteria were abstracted. This was supplemented with a bibliography search and expert consultation. Eligible studies included English-language publications that directly investigated heterosexual women’s motivations for perpetrating non-lethal, physical IPV. Of the 144 potentially eligible articles, 23 met inclusion criteria. Over two-thirds of studies enrolled participants from IPV shelters, courts, or batterers’ treatment programs. Women’s motivations were primarily assessed through interviews or administration of an author-created questionnaire. Anger and not being able to get a partner’s attention were pervasive themes. Self-defense and retaliation also were commonly cited motivations, but distinguishing the two was difficult in some studies. Control was mentioned, but not listed as a primary motivation. IPV prevention and treatment programs should explore ways to effectively address women’s relationship concerns and ability to manage anger, and should recognize that women commonly use IPV in response to their partner’s violence.

BACKGROUND

The concept of women using intimate partner violence (IPV) was discounted in the 1970s and 1980s because of limited data, concerns about shifting funding away from women’s victimization, and recognition that women are more likely than men to be injured from IPV (Steinmetz, 1980). Since this time, increasing numbers of women have been arrested for IPV due to new mandatory arrest policies (DeLeon-Granados, Wells, & Binsbacher, 2006; Miller, 2005). In part because of these arrests, attention has magnified, and a growing number of publications have explored women’s IPV.

In a meta-analysis of studies comparing men’s and women’s use of IPV, Archer (2000) concluded that women were significantly more likely to have ever used physical IPV and to have used IPV more frequently. The majority of studies included in Archer’s (2000) meta-analysis measured IPV as the number of IPV acts over a designated time period. However, counting the number of IPV acts does not provide information about why women used IPV.

Myriad theories explaining women’s motivations for physical IPV have been proposed. Feminist theory-based research emphasizes the importance of gender inequity, and posits that women use IPV in self-defense or in response to their partner’s pattern of abuse (Dasgupta, 2002; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Swan & Snow, 2006; Worcester, 2002). Family conflict research argues that men and women have similar motivations, which include anger and the desire to resolve disagreements (Straus, 2005). Still other research contends that, like men, women use physical IPV to exert power and control (Buttell & Carney, 2005). Michael Johnson (Johnson, 1995; Johnson, 2006) has attempted to integrate these theories, proposing that the underlying reasons for IPV differ depending on the type of IPV relationship (intimate terrorism, situational couple violence, violent resistance, or mutual violent control).

All of these theories, however, tend to depict women’s motivations as discrete and singular; the reality is likely more complex, with women having multiple concurrent motivations. But, an empirically-based, unified understanding of women’s motivations is lacking, thereby impacting the ability to design effective screening and intervention programs. For example, it is unclear when dual arrest in IPV cases is warranted, and what content should be included in batterers’ treatment programs for women. Some authors have published synopses of women’s IPV motivations (Buttell & Carney, 2005; Dasgupta, 2002; Hamberger, 2005; Worcester, 2002; Swan & Gambone, 2008), but none have systematically reviewed the literature, likely limiting their conclusions. We therefore conducted a systematic review of published research to summarize women’s motivations for the use of physical IPV in heterosexual relationships.

METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies included those that directly investigated women’s motivations for perpetrating non-lethal, physical IPV. For inclusion, studies also had to have: 1) involved primary data collection or existing dataset analysis; 2) enrolled participants who were predominantly heterosexual and who were on average ≥ 22 years old; 3) been written in English; and 4) been published in a peer-reviewed journal. Studies whose participants were primarily in same-sex relationships or who were >22 (and therefore likely involved in relationships with “dating violence”) were excluded given that the underlying dynamics, and hence motivations, of same-sex or dating relationships often differ from those of adult women in opposite-sex relationships.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Sociological Abstracts were searched from their start dates through July 2009 using the following terms searched in all fields: (intimate partner violence or domestic violence or spousal abuse or violence against women) and (mutuality or symmetry or women’s use or women’s violence or female perpetration or patterns or classes or typologies). This initial search was augmented with a bibliography review of included studies and related review articles. An author and senior IPV investigator was asked for any additional unfound studies.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

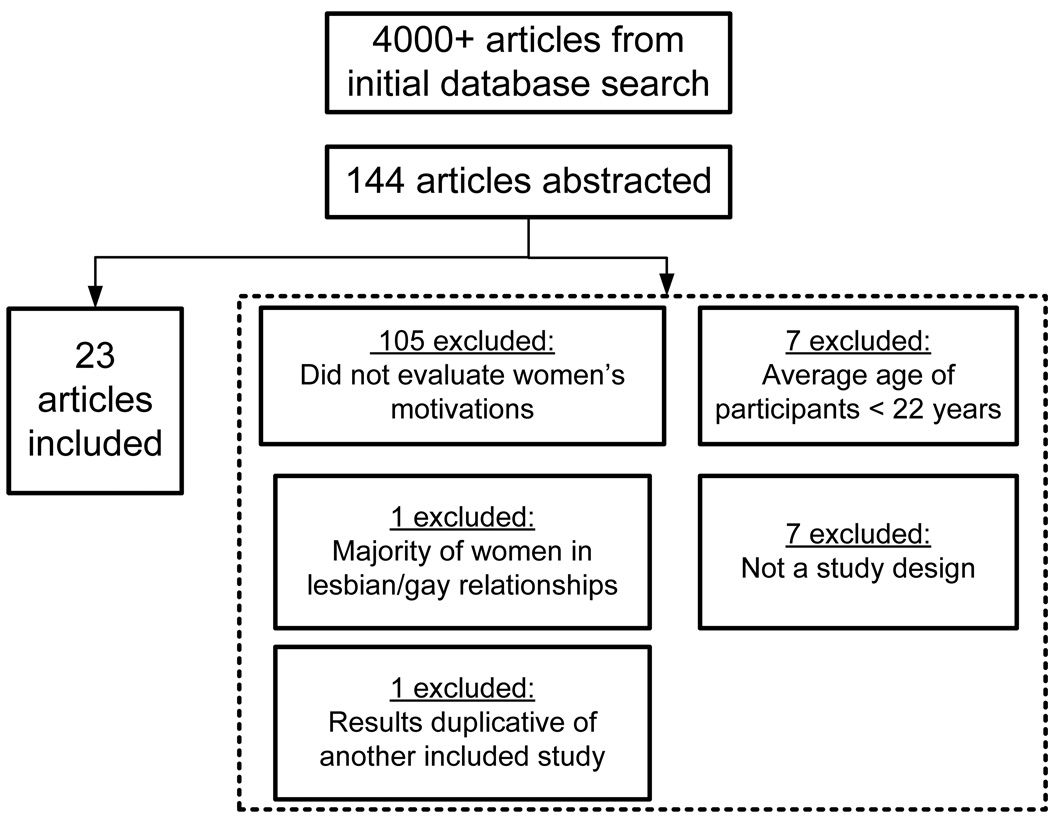

The initial search yielded over 4000 articles. The search terms were purposefully broad; as a result, many articles were not relevant and could be deemed non-eligible from the title. If an article’s eligibility was not evident from the title, the abstract was reviewed. Full text was retrieved for 144 studies that appeared eligible, or for which eligibility could not be determined from the title and abstract.

Two independent abstractors read these 144 articles to determine inclusion. If the two abstractors disagreed, inclusion was discussed with a third abstractor until consensus was reached. Final review narrowed the set of articles to 23 (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam, Jones, & Templar, 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; Miller & Meloy, 2006; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few, Daly, & Tritt, 2005; Sarantakos, 2004; Saunders, 1986; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth, Ramsey, & Kahler, 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007). Figure 1 reports reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study inclusion

Data from the 23 included articles were abstracted by one author using a pre-specified abstraction form that included information on study sample recruitment, size and demographics, methods (i.e. qualitative; survey-based including details about the survey instrument, etc) and results (i.e. themes from qualitative studies; motivations listed and percentage espousing each motivation from survey-based studies). Abstracted data were checked for accuracy by a second author.

RESULTS

Sample Composition

Table 1 presents details of the 23 included studies. Participants with diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds were recruited from the United States (20 studies), England (2), and Australia (1). Twelve (52%) studies (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Sarantakos, 2004) included both men and women, with five enrolling couples (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Sarantakos, 2004). Sixteen (70%) studies recruited women from IPV shelters, prisons, or batterers’ treatment programs (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; Miller & Meloy, 2006; Saunders, 1986; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007). Nine (39%) studies recruited from a health care-based or community-based sample (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Sarantakos, 2004; Swan & Snow, 2003; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007). In the community-based studies, subjects were located in myriad ways ranging from random-digit dialing to the authors inviting people to participate.

Table 1.

Studies of intimate partner violence (IPV) motivations

| Authors & Year | Sample Size and Recruitment | Sample Demographics | Measure of Motivations | Results of Main IPV Motivations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003 | 115 English women in shelters, male and female college students, and male prisoners | Mean age: 33 years | 22-item EXPAGG questionnaire | Associated with instrumental and not expressive beliefs |

| Barnett, Lee & Thelen, 1997 | 64 women and men from IPV shelters, shelter outreach groups, and court-mandated batterers’ programs | 100% Caucasian | Author-created 28-item Relationship Abuse Questionnaire based on items endorsed on Conflict Tactics Scale | Let out violence, get other’s attention, upset other emotionally, teach a lesson, show who is boss, self defense |

| Carrado, George, Loxam, Jones, & Templar, 1996 | 1978 English men and women recruited from a community based sample | No demographic data provided | Author-created 8-item measure with open-ended option | Get through to partner (53%), get back for something said or threatened (52%), make partner stop doing something (33%), get back for physical action (33%), make partner do something (26%), self defense (17%) |

| Cascardi & Vivian, 1995 | 62 couples (n=114) seeking marital therapy | Mean age: 31.12 years (women) 34.18 years (men) |

Semi-Structured Marital Interview |

Minor IPV anger/coercion (50%), anger (40%), stress (10%), self defense (5%) Severe IPV anger/coercion (40%), anger (52%), self-defense (20%) |

| Dobash & Dobash, 2004 | 95 couples (n=190) recruited from court cases involving male perpetrated IPV | No demographic data provided | Interviews | Self defense (75%), retaliation |

| Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson 2007 | 447 women from 7 domestic violence programs and 5 substance use disorder programs | Median age: 33.54 years 77.6% Caucasian 22% < high school 29.5% employed |

Interviews | Avoid abandonment and release anger (particularly substance abuse women), preemptive strike, self defense |

| Flemke & Allen, 2008 | 37 incarcerated women with addictions | Age range: 19–47 years 43% African American 41% Caucasian |

Interviews | Retaliation, jealousy, betrayal, abandonment, self defense (46%) |

| Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994 | 294 women and men court-referred for batterers’ treatment programs | Mean age: 29.5 years (women) 31.5 years (men) 72% Caucasian 64% ≥ high school 74% employed |

Interviews | Retribution, expression of negative emotions, negative instrumental control/coercive power, retaliation for emotional abuse, demanding attention, escape, self defense |

| Hamberger, 1997 | 52 women arrested for IPV | Mean age: 29.5 years 84% Caucasian 67.3%≥ high school 56.8% employed |

Interviews | Self defense (46%), express feeling/tension (19%), get partner to stop nagging/shut up (12%), get partner to talk, attend, or listen (10%), retaliate (10%), assert authority (4%) |

| Hamberger & Guse, 2005 | 125 women and men court-ordered for batterers’ treatment programs | Mean age: 34.8 (women) 33.5 (men) 74% Caucasian 73% ≥ high school 82% employed |

Interviews | Three clusters of participants: Cluster 1 6% women characterized by low fear and high anger; Cluster 2 52% women characterized by doing what partner wants and attempts to escape; Cluster 3 33% women characterized by use of force back and escape Cluster 1 control/dominate (67%), don’t know (12%), self defense/retaliation (10%) Cluster 2 self-defense/retaliation (37%), control/dominate (29%), don’t know (19%) Cluster 3 control/dominate (50%), don’t know (21%), self defense/retaliation (13%), emotional release (13%) |

| Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005 | 1426 men and women convicted of partner abuse | Mean age: 32.3 (women) 32.8 (men) 84% African American |

Author created 16-item measure | Self defense (65%), difficulty controlling anger (31%), problem with jealousy (25%), not willing to compromise (23%) |

| Kernsmith, 2005 | 125 men and women in a batterers’ treatment program | Mean age: 34 years 46.6% Chicano/Latino 33% Caucasian 42%≤high school |

Modified 19-item Perceived Behavioral Control Scale | Retaliation for emotional pain (42%), self defense (29%), expressing anger (29%); mean factor scores for control non-significantly higher for women than men |

| Miller & Meloy, 2006 | 95 women involved with a offenders’ treatment program | 61% White 31% African American |

Observation of offenders’ treatment groups | Women categorized as generally violent (5%), frustration response (30%) and defensive behavior (65%) Generally violent did not establish control with IPV Frustration response nothing would stop partner’s behavior, respond to emotional abuse, express frustration and outrage Defensive behavior escape from violence and protect themselves and their children |

| O’Leary & Slep, 2006 | 453 couples (n=906) recruited through random digit dialing | Mean age: 35.1 years (women) 37 years (men) 86% Caucasian 86% 95.6% (men) & 48.1% (women) employed |

Author-created Precipitants for Partner Aggression Scale with four motivations listed for acts of IPV reported by Conflict Tactics Scale |

Minor/Severe IPV: partner’s verbal abuse (37%/35%), partner’s physical aggression (11%/21%), something else about partner which commonly was being ignored (43%/34%), child and other (9%/10%) |

| Olson & Lloyd, 2005 | 25 women recruited personally by the first author | Age range: 26–35 years 92% Caucasian |

Interviews | Anger related to initiating aggression; psychological factors (46% of conflicts), rule violations (36%), gain attention and compliance (33%), restoration of face threat (23%) |

| Rosen, Stith, Few, Daly, & Tritt, 2005 | 15 couples (n=30) recruited through community-based advertisements | Mean age: 33 years (women) 36 years (men) 40% African American 33% White 67% with “higher education” |

Interviews | Couples categorized as common couple violence (11), mutual violent control (1), (pseudo) intimate terrorism (1) and violent resistance (2) Common couple violence: reactive anger, retaliation, communication/getting attention, and seeking to influence partner Mutual violent control: intimidation, anger Intimate terrorism: control partner, losing control Violent resistance: reactive when no other options |

| Sarantakos, 2004 | 68 Australian members of violent families recruited as part of a larger study from prior research and through referrals from current subjects and authors | Described as low to middle class | Interviews | Self defense (47%); women rescind self-defense when presented with family member’s view of argument |

| Saunders, 1986 | 52 battered women seeking help from shelters or counseling agency | Mean education: 12.2 years | Author-created 6 item measure |

Minor IPV: self defense (79%), fighting back (65%), initiating attack (27%) Severe IPV: self defense (71%), fighting back (60%) and initiating attack (12%) |

| Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007 | 13 women recruited from batterers’ treatment program | Mean age: 28 years 62% employed |

Interviews | Need to be heard/get attention (69%), self defense (62%), retaliate (62%), loss of control/anger (54%), control partner (15%) |

| Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth, Ramsey, & Kahler, 2006 | 87 women recruited from court-ordered batterers’ treatment program | Mean age: 31.2 years 76% White Mean education 12.1 years Mean income: $18,430 |

Author created 29-item Reasons for Violence Scale | Show anger (39.4%), self defense (38.7%), partner provoked IPV (38.9%), express feelings (38.0%), did not know what to do with feelings (35%), stress (35.2%), retaliate for emotional abuse (35.3%), feel powerful (26.1%), get attention (24.5%) |

| Swan & Snow, 2003 | 95 women recruited from court-ordered batterers’ treatment program, a DV shelter, a health clinic, and from a family court | 63% 25–40 years old 71% African American 72% ≤ high school education 76% unemployed |

Author-created 8-item Motivations for Violence Scale | Women categorized as victims, mixed-male coercive, mixed-female coercive and aggressors Women (all groups): self defense (75%), retribution (45%) and to control partner (38%); women in the abused aggressor group most used IPV to control; victim women used IPV most in self defense; anger a central theme across groups |

| Ward & Muldoon, 2007 | 43 women recruited from a state batterers’ intervention program | Mean age: 31.4 years 67% African American 33% < high school education |

Incident reports | Enforcement (51% of violent incidents)*, punish partner’s behavior (35%), self defense (33%), retaliation (33%); anger a central theme *Enforcement defined as either “to make their partner do something or to pursue, protect, or defend something.” |

| Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007 | 580 women drawn from a larger parent study that recruited through community-based advertisement | Mean age: 40.3 years 39.5% African American 29.9% White 30.6% Mexican American |

Author-created 125- item measure | Women categorized as no IPV, threats but no physical IPV perpetration, non-severe IPV perpetration, severe IPV perpetration: Seven general motives including partners’ negative behavior, increased intimacy/get partner’s attention, personal problems, retaliation/control, childhood experiences, situation/mood, partners’ personal problems; frequency of endorsement of each type of motive varied by group |

Measurement of Motivations

Common motivations are summarized in Table 2. Motivations were assessed primarily through interviews or a written questionnaire. Eleven (48%) studies conducted interviews (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Sarantakos, 2004; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007). Across the qualitative studies, a variety of methodologies was employed such as open coding (Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007), characterized by the identification of categories drawn directly from interview text; analytic induction (Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005), in which themes from the interview text are iteratively related to underlying hypotheses; and content analysis (Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007), which emphasizes how often specific themes occur in the data.Ten studies (39%) measured women’s motivations using a 4-to-125 item questionnaire (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Saunders, 1986; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007). In eight studies (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Saunders, 1986; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007), authors created a questionnaire which generally provided a list of motivations and asked participants to indicate whether a particular motivation matched their reasons for IPV. Two authors (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; O'Leary & Slep, 2006) modified the Conflict Tactics Scale to incorporate closed and open-ended questions about motivations for reported IPV. Six authors reported on the psychometric properties of the questionnaire including internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.47–0.82)(Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Swan & Snow, 2003), inter-rater reliability (kappa 0.60–0.90)(O'Leary & Slep, 2006) and discriminant validity (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997); Weston, Marshall, & Coker (2007) conducted exploratory factor analysis on 125-items and derived a seven factor solution.

Table 2.

Summary of common motivations for women’s use of intimate partner violence (IPV)

| Motivation | Studies supporting motivation | Sample | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anger |

Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997 Cascardi & Vivian, 1995 Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007 Flemke & Allen, 2008 Hamberger, 1997 Hamberger & Guse, 2005 Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994 Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005 Kernsmith, 2005 Miller & Meloy, 2006 Olson & Lloyd, 2005 Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005 Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007 Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006 Swan & Snow, 2003 Ward & Muldoon, 2007 |

IPV shelters & court Marital therapy group IPV/substance use programs Prison Arrested women Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Arrested women Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Community based Community based Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group/court/ clinic Batterers’ group |

Author-created survey Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview Author-created survey Perceived Behavioral Control Scale Observation of treatment groups Interview Interview Interview Author-created survey Author-created survey Reading incident reports |

| Desiring partner’s attention |

Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997 Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996 Hamberger, 1997 Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994 O'Leary & Slep, 2006 Olson & Lloyd, 2005 Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005 Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007 Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006 Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007 |

IPV shelters & court Community based Arrested women Batterers’ group Community based Community based Community based Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Community based |

Author-created survey Author-created survey Interview Interview Author-created survey Interview Interview Interview Author-created survey Author-created survey |

| Self-defense |

Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997 Carrado, George, Loxam, Jones, & Templar, 1996 Cascardi & Vivian, 1995 Dobash & Dobash, 2004 Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007 Flemke & Allen, 2008 Hamberger, 1997 Hamberger & Guse, 2005 Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994 Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005 Kernsmith, 2005 Miller & Meloy, 2006 O'Leary & Slep, 2006 Olson & Lloyd, 2005 Sarantakos, 2004 Saunders, 1986 Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007 Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth, Ramsey, & Kahler, 2006 Swan & Snow, 2003 Ward & Muldoon, 2007 |

IPV shelters & court Community based Marital therapy group Court IPV/substance use programs Prison Arrested women Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Arrested women Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Community based Community based Community based Shelter/IPV agency Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group/court/ clinic Batterers’ group |

Author-created survey Author-created survey Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview Author-created survey Perceived Behavioral Control Scale Observation of treatment groups Author-created survey Interview Interview Author-created survey Interview Author-created survey Author-created survey Reading incident reports |

| Retaliation |

Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996 Dobash & Dobash, 2004 Flemke & Allen, 2008 Hamberger, 1997 Hamberger & Guse, 2005 Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994 Kernsmith, 2005 Miller & Meloy, 2006 O'Leary & Slep, 2006 Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005 Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007 Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006 Swan & Snow, 2003 Ward & Muldoon, 2007 Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007 |

Community based Court Prison Arrested women Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Community based Community based Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group/court/health Batterers’ group Community based |

Author-created survey Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview Perceived Behavioral Control Scale Observation of treatment groups Author-created survey Interview Interview Author-created survey Author-created survey Reading incident reports Author-created survey |

| Coercive control |

Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997 Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996 Cascardi & Vivian, 1995 Hamberger, 1997 Hamberger & Guse, 2005 Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994 Kernsmith, 2005 Olson & Lloyd, 2005 Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005 Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007 Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006 Swan & Snow, 2003 Ward & Muldoon, 2007 Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007 |

IPV shelters & court Community based Marital therapy group Arrested women Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Community based Community based Batterers’ group Batterers’ group Batterers’ group/court/ clinic Batterers’ group Community based |

Author-created survey Author-created survey Interview Interview Interview Interview Perceived Behavioral Control Scale Interview Interview Interview Author-created survey Author-created survey Reading incident reports Author-created survey |

IPV Motivations

Anger

Anger was a common theme in 16 studies (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; Miller & Meloy, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007). Some of these studies listed anger as a primary motivation, while others described anger as it related to another motivation or emotion such as anger secondary to jealousy over a partner’s infidelity. One additional study grouped anger with other motivations, making its unique contribution difficult to disentangle (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003). Of 14 studies that ranked or compared motivations based on frequency of endorsement (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Saunders, 1986; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007), two found that anger/emotion release was the most common reason (39%) that women reported using IPV (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006), and one found that anger/coercion (50–52%) was the top-ranking motivation (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995). Olson & Lloyd (2005) documented that “psychological factors,” which grouped anger with other emotions, were the most common motivation for IPV.

One participant in Flemke & Allen’s (2008) study of rage stated “When he would be out for 3 days and wouldn’t come home, I would get full of rage just waiting for him…. When he finally came home,…. I became so enraged that I hit him with a bat” (p.68). Ward & Muldoon (2007) concurred that “anger emerges as a central theme….” (p.355).

Desiring Attention

Women in 10 studies stated that they used IPV to get their partner’s attention (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007) or get through to him (Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996). Archer & Graham-Kevan (2003) included an item about using IPV to get through to one’s partner, but did not report the percentage number of women endorsing this item. Getting attention/through to one’s partner was the most common motivation (53–69%) in two studies (Seamans, Rubin & Stabb, 2007; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996).

Seamans, Rubin & Stabb (2007) hypothesized that women interpreted being ignored as a message that they were unworthy. Olson & Lloyd (2005) also reported that women’s use of IPV to gain their partners attention was a “glaring pattern” (p. 615). Women stated that they had tried benign strategies to engage their partners, but resorted to IPV when their partners continually ignored them.

Self-defense and Retaliation

Self-defense was listed as a motivation for women’s use of IPV in all of the included articles, except three, one of which administered a questionnaire that did not ask about self-defense (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007). Of the 14 studies that ranked or compared motivations based on frequency of endorsement, (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Saunders, 1986; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007), four (Hamberger, 1997; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Saunders, 1986; Swan & Snow, 2003) found that self-defense was women’s primary motivation (46–79%) for using IPV, with one additional study reporting self-defense as the second most common motivation (39%) (Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006).

Self-defense was defined differently between studies. Most women described self-defense as using IPV to avert their partner’s physical injury (Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Miller & Meloy, 2006; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Ward & Muldoon, 2007); some used IPV after their partner had struck, while others initiated IPV because of fear of imminent danger. Other women reciprocated their partner’s physical abuse to protect their emotional health (Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007).

Two studies did not support that self-defense is a predominant impetus for women’s IPV (Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Sarantakos, 2004). Olson & Lloyd (2005) interviewed 25 women who described 69 episodes of IPV with only one mention of self-defense. Sarantakos (2004) concluded that 47% of women initially reported using IPV for self-defense, but this number decreased to 23% when women were told that other family members would be corroborating their attribution of self-defense. The reasons that women changed their statements were unclear, and could reflect initial social desirability bias or concerns about a violent partner’s response to their self-defense assertion.

Retaliation was a listed motivation in 15 studies (Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Dobash & Dobash, 2004; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Kernsmith, 2005; Miller & Meloy, 2006; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007) with one study documenting this as women’s primary motivation (Kernsmith, 2005). Women described using IPV to retaliate for both physical and emotional abuse (Miller & Meloy, 2006; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007). For example, a participant in Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb’s (2007) study was arrested after shooting her husband because he had been emotionally abusive over the course of a 19 year marriage.

Disentangling self-defense and retaliation was difficult in some studies. Hamberger & Guse (2005) grouped self-defense and retaliation as one motivation. O’Leary& Slep (2006) reported that women most frequently used IPV “in response to their partner’s aggression,” which could incorporate either. Weston, Marshall & Coker did not list self-defense as a motivation, but hypothesized that “women [may] perceive self-protective actions as more retaliatory than self-defensive” (p.1063).

Coercive Control

Women listed control as a motive in 14 studies (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Hamberger, Lohr, & Bonge, 1994; Kernsmith, 2005; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007); three of the questionnaire-based studies did not ask about coercive control as a motive (Archer & Graham-Kevan, 2003; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Saunders, 1986). None of the 14 studies that ranked or compared motivations based on frequency of endorsement (Barnett, Lee, & Thelen, 1997; Carrado, George, Loxam et al., 1996; Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Hamberger, 1997; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Kernsmith, 2005; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Olson & Lloyd, 2005; Saunders, 1986; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Stuart, Moore, Hellmuth et al., 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003; Ward & Muldoon, 2007) clearly documented that control was the primary IPV motivation. Hamberger (1997) cautioned that reports of coercive control may be miscoded in qualitative studies, describing one woman who used IPV to force her partner out of the house. Although she was attempting to control his behavior, her underlying reason was concern for personal safety.

Difference in Motivations by IPV Severity, Type of IPV Relationships or Personal Characteristics

Eight articles stratified motivations by IPV severity, type of IPV relationship or characteristics of the included women (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; Hamberger & Guse, 2005; Miller & Meloy, 2006; O'Leary & Slep, 2006; Rosen, Stith, Few et al., 2005; Saunders, 1986; Swan & Snow, 2003; Weston, Marshall, & Coker, 2007). These articles reported that motivations varied depending on the nature of the intimate relationship or qualities of the women. For example, three articles found that women were more likely to use IPV in response to their partner’s physical aggression or in self-defense if severe IPV were occurring or if women were in relationships in which they used less severe violence then their partner (Cascardi & Vivian, 1995; O’Leary & Slep, 2006; Swan & Snow, 2003). On the other hand, Saunders (1986) found that slightly fewer women in relationships with severe (71%) versus minor IPV (79%) used IPV in self-defense. Weston, Marshall & Coker (2007) reported that women perpetrating more severe IPV were more likely to view a variety of motivations as being important.

Rosen, Stith, Few, et al. (2005) used Michael Johnson’s (Johnson, 2006) typologies -- common couple violence, intimate terrorism, violent resistance, mutual violent control -- to categorize subjects, and found that motivations varied between classes. For example, members of the common couple violence class resorted to IPV because of reactive anger, while violent resisters used IPV when they did not feel that they had any alternatives. Miller & Meloy (2006) created three categories of aggressive women—generally violent, frustration response, and defensive behavior-- based in part on women’s prior criminal records, and examined motivations based on category. Generally violent women used IPV reactively, frustration response women used IPV if they felt there were no other options, and defensive women used IPV to protect themselves or their children. Hamberger & Guse (2005) similarly found that women who felt low fear and high anger in response to a partner’s abuse were more likely to use IPV to control a partner while women who felt the desire to escape their partner’s abuse were more likely to use IPV in self-defense.

DISCUSSION

This review reflects the complexity of women’s motivations for using IPV and reveals several important trends. Specifically, women’s motivations tended to be more closely related to expression of feelings and response to a partner’s abuse than to the desire for coercive control. This review also highlights methodological limitations of the current research, thereby emphasizing the need for further research.

Women’s motivations for IPV can be examined from the vantage-point of a nested ecological model (Archer, 2000; Dasgupta, 2002; Heise, 1998). This model proposes four interactive levels, each of which potentially affects women’s IPV motivations: 1) macro-system including pervasive beliefs like prescribed gender roles; 2) exo-system including societal structures like the neighborhood and workplace; 3) micro-system including relationship characteristics; and 4) individual including personal characteristics (Dasgupta, 2002).

In western societies, IPV occurs in a macro-and exo-system in which men generally have more physical and social power than women, and women are socialized to assume a more passive role than men (Dasgupta, 2002; Heise, 1998; Worcester, 2002). Women therefore are unlikely to be successful in controlling their partners, even with the use of physical IPV. It follows that the desire for coercive control was not endorsed in any study as the most frequent reason for IPV. However, control cannot be ignored as a motivation given that women listed it in two-thirds of included studies. This is concordant with Hamby’s (2009) report that men and women both use IPV for coercive control. Kernsmith (2005) hypothesized, however, that men and women may define and use control differently; women use control to gain autonomy in relationships, whereas men use control to demonstrate authority.

Women in the included studies discussed micro-system factors influencing their use of IPV. Specifically, women reported feeling angry after futile attempts to get their partner’s attention. In a review paper about women and anger, Thomas (2005) similarly found that women felt powerless when significant others ignored them, and that this powerlessness commonly provoked anger. Adhering to female gender expectations, some women may stifle this anger (Flemke & Allen, 2008; Thomas, 2005). Suppressed anger generally does not dissipate, and may eventually lead to overt aggression (Thomas, 2005).

In addition to anger, self-defense and retaliation were common motivations described by women in the included studies. However, this review demonstrates the difficulty in defining and measuring self-defense and retaliation. Many women discussed using physical aggression after their partner’s IPV to minimize personal injury (Downs, Rindels, & Atkinson, 2007; Flemke & Allen, 2008; Miller & Meloy, 2006; Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007; Ward & Muldoon, 2007). All would agree this is self-defense (Wimberly, 2007). Women also described using IPV because they did not want to internalize images of themselves as victims (Seamans, Rubin, & Stabb, 2007). Although these women were arguably using IPV to protect their emotional health, this does not meet the legal definition of self-defense (Wimberly, 2007). Whether this should fall into a more conceptual definition of self-defense or whether it is more consistent with retaliation is controversial. It is similarly conceptually unclear how to categorize women’s IPV in response to their partner’s verbal abuse which may include threats of physical harm.

Some women described initiating IPV as a pre-emptive strike because of concern that their partner would become violent. Saunders (1986) offered a criminal justice definition of self-defense which emphasized situations when a victim has been assaulted and when a victim believes she is in imminent danger. This definition includes the initiation of IPV, thereby allowing for the reasonable fear of imminent danger to take into account prior incidents. Despite these definitions, it is unclear how consistently researchers or participants viewed pre-emptive IPV as self-defense.

Women’s IPV may be related to individual factors which encompass childhood experiences and personality traits. Studies have documented the association between women’s IPV and personal histories of child abuse, violence exposure, and substance abuse (Field & Caetano, 2005; McKinney, Caetano, Ramisetty-Mikler, & Nelson, 2009; Swan & Snow, 2006). These studies were not included because they did not measure how these attributes directly affected women’s IPV motivations. Most included studies did measure socio-demographic characteristics, but women generally did not discuss them as primary IPV motivations.

Several methodological limitations of the included studies must be considered. The majority gathered data through interviews or written questionnaires. Both methods have potential biases. In interviews, women and men may remember and verbalize motivations differently, and both may be tempted to provide pro-social responses. Only two of the included studies measured social desirability bias (Henning, Jones, & Holdford, 2005; Saunders, 1986). Saunders (1986) found that IPV data and social desirability were not correlated, while Henning, Jones, & Holdford (2005) found that participants were more likely than normative samples to provide socially desirable responses. In a meta-analysis of IPV self-reporting and social desirability bias, Sugarman & Hotaling (1997) found that the correlation was stronger for perpetration than for victimization, but that there were no between-sex differences. Biases also may occur in qualitative data coding. Coders may identify different themes based on their own gender or theoretical vantage-point (Hamberger, Lohr, Bonge, & Tolin, 1997).

Questionnaires similarly have limitations. None of the questionnaires in the included studies had complete psychometric testing. Additionally, authors were only able to comment on the motivations about which they asked. Hence, some motivations may have been missed.

All of the included studies were located in industrialized, English-speaking countries. The role of women in developing or culturally dissimilar developed nations may be different, thereby affecting the motivations for IPV (Archer, 2000). Additionally, over two-thirds of the studies recruited women from IPV shelters, jails or batterers’ treatment programs. This group represents only a small proportion of women involved in violent relationships, and these relationships generally have severe and frequent IPV. Underlying motivations for these women likely differ from motivations for community-based women.

As the field of IPV research has grown, it has become increasingly clear that women use IPV. Documentation of this aggression has sparked intense controversy. In order to address these controversies and inform practice, research must move beyond counting acts of IPV and consider the broader context of why intimate partners resort to aggression.

Our review suggests important considerations for research, and for policy and intervention design. First, research should enroll women from diverse sites, and should consider assessing how motivations vary based upon the setting from which women were recruited, or the type or severity of women’s violent relationships. Second, all studies of IPV motivations should include a measure of social desirability bias. Third, coders in qualitative research should be blinded with regard to study participant sex. Finally, the difficulty defining self-defense and retaliation suggest that further research in this area is required. Specifically, focus groups of abused women from a diversity of backgrounds are needed to better understand how women define these constructs. Content from these focus groups, as well as input from IPV experts, could then be used to develop and test instrument items, including an exploration of their factor structure. Results from these studies could then contribute to the development of a broader, psychometrically sound measure of women’s motivations for using physical IPV.

Legal policies must recognize that women commonly use IPV in response to their partners’ violence. Such an acknowledgement is supported by Miller (2005) who contended that mandatory arrest policies fail to recognize that many women who use IPV are also victims, thus inappropriately subjecting a proportion of women to court-mandated batterer’s programs. Increased training for police may help them to accurately determine whether women’s use of IPV is primarily related to self-defense (Kernsmith, 2005).

Many existing IPV batterers’ treatment programs are based upon models of male-perpetration. These programs need to be adapted to meet the unique needs of women who use IPV. IPV treatment programs should explore ways to effectively address the inter-related triad of feeling ignored, powerless, and angry. Helping clients to verbalize and increase awareness of such emotional experiences, describe how these experiences may relate to other emotions, and link these emotions with behavior may be useful. Additionally, developing programs that empower women and bolster self-image, as well as programs that teach anger management strategies, may be useful in prevention of women’s use of IPV and in treatment programs for women who use IPV.

Key Points of the Research Review

Existing studies on women’s motivations for using intimate partner violence (IPV) have the following methodological limitations: 1) most recruit subjects from IPV shelters, jails or batterers’ treatment programs which represent only a small proportion of women involved in violent relationships; and 2) data come predominantly from small qualitative studies or from author-created questionnaires without comprehensive psychometric validation; social desirability bias was rarely measured.

Evidence suggests that women commonly use IPV in response to their partner’s violence either in self-defense or in retaliation. However, the definition of self-defense was inconsistent between studies.

Anger expression was a recurrent theme, and women frequently stated that they used IPV because they felt ignored.

Coercive control was mentioned by women as a reason for IPV, but was not endorsed in any of the included studies as women’s most frequent motivation.

Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research

Studies increasingly document that women use intimate partner violence (IPV). Most of these studies, however, count the number of acts of IPV over a specified time period and do not further investigate the context of the IPV. Consideration of women’s motivations for using IPV is essential to develop effective policies and interventions. Therefore:

Clinicians are encouraged to consider that women often use IPV for the purposes of self-defense and for retaliation, and because they feel angry, powerless and ignored. Empowering women and bolstering self-image, as well as teaching anger management strategies, may be useful in the treatment of women who use IPV.

When considering mandated arrest policies, policy makers should recognize that women commonly use IPV in response to their partner’s violence.

There is a relative dearth of research in this area. Therefore, there is a strong need for researchers to conduct rigorous, methodologically sound studies investigating why women use IPV. These studies should seek to enroll a representative community-based sample of women. Focus groups and subsequent development of a questionnaire measuring self-defense and retaliation are also needed; data from these studies could contribute to the development of a broader, psychometrically sound measure of motivations.

Acknowledgements

Dr Bair-Merritt is funded in part by a Career Development Award (K23HD057180) sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr Bair-Merritt has had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Graham-Kevan N. Do beliefs about aggression predict physical aggression to partners? Aggress Behav. 2003;29:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett O, Lee C, Thelen R. Gender differences in attributions of self-defense and control in interpartner aggression. Violence Against Women. 1997;4:462–481. doi: 10.1177/1077801297003005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttell F, Carney M. Women who perpetrate relationship violence: moving beyond political correctness. New York: Hawthorth Press; 2005. p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Carrado M, George M, Loxam E, Jones L, Templar D. Aggression in British heterosexual relationships: a descriptive analysis. Aggress Behav. 1996;22:410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, Vivian D. Context for specific episodes of marital violence: gender and severity of violence differences. J Fam Violence. 1995;10:265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta S. A framework for understanding women's use of nonlethal violence in intimate heterosexual relationships. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1364–1389. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon-Granados W, Wells W, Binsbacher R. Arresting developments: trends in female arrests for domestic violence and proposed explanations. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:355–371. doi: 10.1177/1077801206287315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobash R, Dobash R. Women's violence to men in intimate relationships. Br J Criminol. 2004;44:324–349. [Google Scholar]

- Downs W, Rindels B, Atkinson C. Women's use of physical and nonphysical self-defense strategies during incidents of partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13:28–45. doi: 10.1177/1077801206294807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C, Caetano R. Longitudinal model predicting mutual partner violence among white, black and Hispanic couples in the United States general population. Violence Vict. 2005;20:499–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemke K, Allen K. Women's experience of rage: a critical feminist analysis. J Marital Fam Ther. 2008;34:58–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L, Lohr J, Bonge D. The intended function of domestic violence is different for arrested male and female perpetrators. Family Violence and Sexual Assault Bulletin. 1994;10:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L. Female offenders in domestic violence: a look at actions in their context. J Aggress Maltr Trauma. 1997;1:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L, Lohr J, Bonge D, Tolin D. An empirical classification of motivations for domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 1997;3:401–423. doi: 10.1177/1077801297003004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L. Men's and women's use of intimate partner violence in clinical samples: toward a gender-sensitive analysis. Violence Vict. 2005;20:131–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger L, Guse C. Typology of reactions to intimate partner violence among men and women arrested for partner violence. Violence Vict. 2005;20:303–317. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S. The gender debate about intimate partner violence: solutions and dead ends. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy. 2009;1:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning K, Jones A, Holdford R. "I didn't do it, but if I did I had a good reason": minimization, denial, and attributions of blame among male and female domestic violence offenders. J Fam Violence. 2005;20:131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: two forms of violence against women. J Marriage Fam. 1995;57:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. Gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1003–1018. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernsmith P. Exerting power or striking back: a gendered comparison of motivations for domestic violence perpetration. Violence Vict. 2005;20:173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Nelson S. Childhood family violence and perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence: findings from a national population-based study of couples. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. Victims as Offenders: The Paradox of Women's Violence in Relationships. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Meloy M. Women's use of force: voices of women arrested for domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:89–115. doi: 10.1177/1077801205277356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary S, Slep A. Precipitants of partner aggression. J Fam Psych. 2006;20:344–347. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson L, Lloyd S. "It depends on what you mean by starting": an exploration of how women define initiation and aggression and their motives for being aggressive. Sex Roles. 2005;53:603–617. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen K, Stith S, Few A, Daly K, Tritt D. A qualitative investigation of Johnson's typology. Violence Vict. 2005;20:319–334. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantakos S. Deconstructing self-defense in wife-to-husband violence. J Mens Stud. 2004;12:277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders D. When battered women use violence: husband-abuse or self-defense. Violence Vict. 1986;1:47–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamans C, Rubin L, Stabb S. Women domestic violence offenders: lessons of violence and survival. J Trauma Dissociation. 2007;8:47–68. doi: 10.1300/J229v08n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz S. Women and violence: victims and perpetrators. Am J Psychother. 1980;34:334–350. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1980.34.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. Women's violence toward men is a serious social problem. In: Loseke D, Gelles R, Cavanaugh M, editors. Current Controversies on Family Violence. London: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G, Moore T, Hellmuth J, Ramsey S, Kahler C. Reasons for intimate partner violence perpetration among arrested women. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:609. doi: 10.1177/1077801206290173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman D, Hotaling G. Intimate violence and social desirability: a meta-analytic review. J Interpers Violence. 1997;12:275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Swan S, Gambone L, Caldwell J, Sullivan D, Snow D. A review of research on women's use of violence with male intimate partners. Viol Victims. 2008;23:301–314. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan S, Snow D. Behavioral and psychological differences among abused women who use violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:75–109. [Google Scholar]

- Swan S, Snow D. The development of a theory of women's use of violence in intimate relationships. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1026–1045. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. Women's anger, aggression and violence. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26:504–522. doi: 10.1080/07399330590962636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Muldoon J. Female tactics and strategies of intimate partner violence: a study of incident reports. Sociol Spectr. 2007;27:337–364. [Google Scholar]

- Weston R, Marshall L, Coker A. Women's motives for violent and nonviolent behaviors in conflicts. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22:1043–1065. doi: 10.1177/0886260507303191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly M. Defending victims of domestic violence who kill their batterers: using the trial expert to change social norms. American Bar Association. 2007:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Worcester N. Women's use of force: complexities and challenges of taking the issue seriously. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:1390–1415. [Google Scholar]