Abstract

WHO-Tropical Disease Research scheme highlighted the need for development of new anti-filarial drugs. Certain antibiotics have recently been found effective against Wolbachia, co-existing symbiotically with filarial parasites. Inflammatory response entails oxidative mechanism to educe direct anti-microbial effect. In the present study microfilariae were maintained in vitro in medium supplemented with varying concentrations of tetracycline, doxycycline (20–100 μg/ml) or ciprofloxacin (50–250 μg/ml) separately to find out any involvement of oxidative mechanism in the anti-filarial effect of these antibiotics. Loss of motility of the microfilariae was measured after 48 h and correlated with the levels of MDA, nitric oxide and protein-carbonylation. Significant loss of microfilarial motility was recorded with increasing concentration of tetracycline and doxycycline but with ciprofloxacin the effect was not marked. Agents with high antifilarial activity revealed significant association with oxidative parameters in a dose dependent manner. The result suggests that oxidative effect might be exploited to design novel antifilarial drug candidate.

Keywords: Antibiotics, B. malayi, Oxidative stress, Drug design

Introduction

The microbial diseases still loom large in vast majority of developing countries located in tropics and subtropics even in twenty first century. WHO has recognized this major health problem and rightly shown concern in declaring certain important tropical diseases in its Tropical Disease Research scheme and launched a global programme for elimination of filariasis (GPELF) (www.who.int/tdr/diseases). Popular drug DEC has been in use almost empirically since last four decades [1]. Advent of Mass Drug Administration (MDA) strategy raised hope for elimination of this disease, however, unfortunately this disorder is continuing due to the technical limitations of MDA strategy [2]. Moreover, recent evidence suggested some valid apprehensions of development of resistance and altered immune response towards this disease [3, 4]. This gloomy perspective demands, development of novel antifilarial drugs with precise rationale.

Wolbachia is a group of endosymbiotic bacteria belonging to the order Rickettsiales, had been detected in majority of filarial species studied so far [5]. The discovery of Wolbachia in filarial species has provided a new promising target for the chemotherapy of human filariasis [6]. Anti-rickettsials like Tetracyclines, Doxycycline, Rifampicin, Azithromycin, Chloramphenicol etc. are reported to be active against these bacteria resulting in growth retardation, infertility and reduced viability of the parasite [7]. Ciprofloxacin (DNA—Gyrase blocker) also showed promise in anti-filarial therapy [8]. A recent study has indicated that a 6-week course of doxycycline, either alone or in combination with diethylcarbamazine-albendazole, leads to a decrease in microfilaremia and reduces adverse reactions to antifilarial treatment in B. malayi infected persons [9]. Another evidence showed the combination therapy with doxycycline and ivermectin also remarkably reduced microfiladermia following reductions in Wolbachia in worms [6].

The most prescribed drug for lymphatic filariasis is Diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC). The exact mechanism of action of this drug is not known but experimental evidences suggest its involvement in the modification of host’s innate immunity [10] and influencing prostanoid metabolism linked to inflammatory response [11]. First line of defense against microbial invasion is mounted by host inflammatory response as a part of innate immunity. Interestingly such response depends on oxidative rationale, exerted by the inflammatory mediators elaborated by the immunocytes.

With this perspective, this study has been undertaken to explore the role of oxidative stress if any, in the direct antifilarial effect using certain selected antibiotics like Tetracycline, Doxycycline and Ciprofloxacin in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Antibiotics

Tetracycline, Doxycycline and Ciprofloxacin (Sigma) were dissolved in RPMI media and further diluted in different pre-optimized concentrations for in vitro experimentation against B. malayi microfilaria.

Parasites

The B. malayi life cycle was established and maintained in Jirds (Meriones unguiculatus) and Mastomys (Mastomys natelansis) using Mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti) as a vector by standard methods [12]. Microfilariae were obtained by lavage of the peritoneal cavities of Jirds with intraperitoneal filarial infection of 3 months or more duration. The mf were washed with RPMI 1640 medium (containing 20 μg/ml Gentamycin, 100 μg/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin) plated on sterile plastic petri-dishes and incubated at 37°C for 1 h to remove Jirds peritoneal exudate cells. The mf were collected from petri-dishes, washed with RPMI 1640 medium and used for in vitro experiments as per standard protocol [13].

In Vitro Screening for Antifilarial Activity

The procedure suggested by Sahare et al. [13] was followed for the in vitro screening of anti-biotics for anti-filarial activity. Briefly, Antibiotics were diluted in RPMI media to obtain the desired final concentration range (20–100 μg/ml for tetracycline and doxycycline and 50–250 μg/ml for Ciprofloxacin respectively) in sterile 24 well Culture plates (Nunc, Denmark) containing 900 μl of RPMI media per well. Wells without any extract but with suitable solvents in 900 μl of the media were kept as corresponding controls. Approximately 100 microfilariae in 100 μl were introduced into each well in triplicates for both test and control wells. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h in CO2 (5%) incubator. These experimental conditions were standardized in our lab set-up. Post incubation washing with RPMI media was carried out to rule out the reversal effect. Mf motility was assessed by microscopy after 48 h of exposure; the observations were recorded as the number of live and dead Mf in each well. Each experimental procedure was repeated thrice and the results were found to be reproducible.

Percentage (%) motility was calculated by formula below and further, the percentage loss of motility was calculated:

|

|

Estimation of MDA Levels

To 0.5 ml of culture supernatants of each antibiotics and MDA standards (2.5–40 nmol/ml) respectively, 2.5 ml of 20% TCA + 1 ml of 0.67% Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) were added and mixed by using vortex. Then the mixtures were boiled in hot water bath for 30 min. After cooling in cold-water bath, the resultant chromogen was extracted with 4 ml of n-butyl alcohol and separation of organic phase was done by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Absorbance of the butyl alcohol extracts of standards and samples was measured at 530 nm against butyl alcohol as blank. The standard curve was plotted and concentrations of total MDA in samples were calculated and expressed as nmol malondialdehyde/ml of culture supernatant [14].

Estimation of Carbonyl Content

The 48 h culture supernatants of antibiotics were estimated for their protein carbonylation by Levine method [15] with some modifications. The culture supernatants were treated with 500 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) reagent and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatants were discarded. The precipitated proteins so obtained were treated with 500 μl of 2, 4 di-nitrophenyl-hydrazine (DNPH) reagent and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with intermittent vigorous mixing at every 15 min interval.

Again 500 μl TCA (10%) was added to each sample and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 5 min. After discarding the supernatant, precipitates were washed thrice with 1 ml of ethanol/ethyl acetate (1:1), each time centrifuging out the supernatant to remove the free DNPH and lipid contaminants. The precipitates were dissolved in each 1.5 ml of protein dissolving solution and incubated at 37°C water bath for 10 min. The color intensity of supernatant was measured using spectrophotometer at 370 nm against 2 mol HCl as blank. Carbonyl content was calculated by using molar extinction-coefficient (21 × 103 mol−1 cm−1) and expressed as nM carbonyl content/mg of protein in the culture supernatant.

Estimation of Nitric Oxide levels

The amount of nitric oxide (NO) in the 48 h culture supernatants of antibiotics was estimated using Griess reagent (1% Sulfanilamide, 0.1% napthylenediamine hydrochloride and 2.5% Phosphoric acid). 100 μl of the Griess reagent was added to 100 μl of culture supernatant in 96 well microtitre plates. Absorbance was read at 542 nm after 10 min incubation. Standard curves were prepared with known concentrations of sodium nitrite ranging from (0.0515–0.2585). Results were expressed as μg/ml of culture supernatant [16].

Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SD for the triplicate observations made in each case. For comparison of means of different parameters between the test antibiotic drugs and respective controls, Student’s t test was used. P values of <0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Effects of Antibiotics on Mf Motility

Tetracycline, Doxycycline and Ciprofloxacin were tested for anti-filarial activity against B. malayi mf. Effects of these antibiotics on Mf motility are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effect of antibiotics 48 h on B. malayi micro-filarial motility. Results shown are mean + SEM of percent reduction in motility

| Varying concentrations of antibiotics (μg/ml)a | Percentage reduction in Mf motility by antibiotics after 48 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline | Doxycycline | Ciprofloxacin | |

| C1 | 99.96 ± 1.09* | 44.34 ± 2.905* | 11 + 2.645* |

| C2 | 98.99 ± 1.11* | 59 ± 1.154* | 10 ± 1.154* |

| C3 | 98.63 ± 1.154* | 71.34 ± 4.484* | 13.67 + 1.452* |

| C4 | 99.99 ± 1.476* | 96.53 ± 2.014* | 17 + 1.527* |

| C5 | 99.85 ± 1.039* | 99.63 ± 1.123* | 18 + 1.154* |

| Control | 3.15 ± 0.22 | 3.15 ± 0.22 | 3.15 ± 0.22 |

* Significant at the level of P < 0.05 when compared with respective control levels (RPMI with Mf)

aConcentrations of antibiotics in samples C1–C5. 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μg/ml respectively for tetracycline and doxycycline and 50, 100, 150, 200 and 250 μg/ml respectively for ciprofloxacin

The effect of Tetracycline and Doxycycline (20–100 μg/ml) on microfilarial (Mf) motility was observed after 48 h. After 48 h both Tetracycline and Doxycycline showed significant loss of Mf motility compared to controls. However, with Tetracycline all the Mf lost motility even at the minimum concentration of 20 μg/ml. With Doxycycline, complete loss of Mf motility was recorded at the concentration of 80 μg/ml. Ciprofloxacin showed less antifilarial activity compared to Tetracycline and Doxycycline. Ciprofloxacin failed to induce even 50% loss of motility.

Since Antibiotics viz., Tetracycline and Doxycycline showed significant anti-microfilarial effects, they were further checked for oxidative stress parameters.

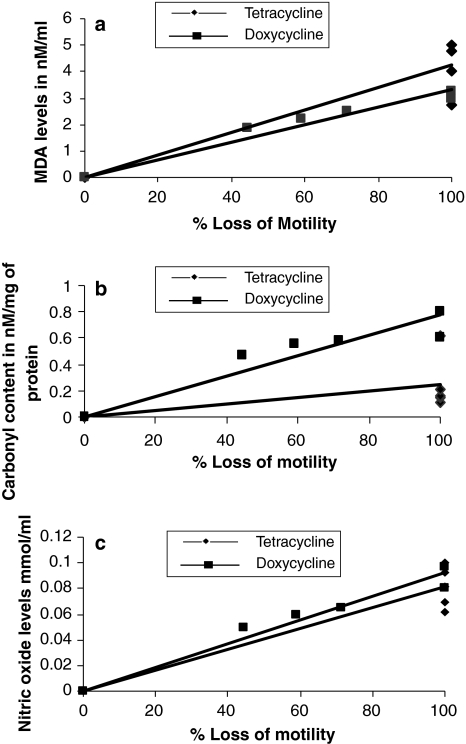

The culture supernatants of antibiotics obtained after 48 h were assessed for lipid peroxidation (by estimating the levels of malondialdehyde), carbonyl content and nitric oxide levels. Supernatants of Tetracycline and Doxycycline showed higher MDA, carbonyl content and nitric oxide levels as compared to supernatant of control (RPMI medium). The results of dose dependent correlation between loss of mf motility and stress parameters (MDA, Carbonyl content and Nitric oxide levels) are summarized in Fig. 1a, b and c.

Fig. 1.

a MDA levels of antibiotics (nM/ml) in culture supernatants obtained after 48 h incubation with each of the antibiotics. MDA levels in control (RPMI medium): 2.5 nM/ml (tetracycline: y = 0.0426x, R2 = 8153; doxycycline: y = 0.0333x, R2 = 0.9464). b Carbonyl content of antibiotics (nmol/mg of protein) in culture supernatants obtained after 48 h incubation with each of the antibiotics. Carbonyl content in control (RPMI medium): 0.0244 nM/mg of protein (tetracycline: y = 0.0077x, R2 = 0.8465; doxycycline: y = 0.0025x, R2 = 0.2349). c Nitric oxide levels of antibiotics (in mM/ml) in culture supernatants obtained after 48 h incubation with each of the antibiotics. Control value (RPMI): 0.0004 mM/ml (tetracycline: y = 0.0008x, R2 = 0.847; doxycycline: y = 0.0009x, R2 = 0.9477)

Discussion

The present study carried out with certain antibiotics like tetracycline and doxycycline showed significant antifilarial effect whereas the other drug used in this study namely ciprofloxacin failed to achieve similar level of efficacy. The first two macrolide derivative compounds are well known for their role against Wolbachia [17], while in the earlier report these compounds were shown to be effective in controlling mf release by the adult parasite affecting the reproduction process. In this study we found direct effect of these compounds on mf. This probably implies that apart from the usual antibiotic effect on the bacterial target, these agents might have a direct impact on the filarial parasites. The other antibiotic used in this study belongs to quinolone group that belongs to DNA-gyrase inhibitors and are well known broad spectrum antibiotics [18]. Macrolides are known to have better efficacy against Wolbachia, whereas the quinolone derivative failed to show any significant in vitro effect against wolbachia in Aedes albopictus cell line [19]. In this study, we also did not record any significant effect on mf motility with this agent.

In our study, the oxidative markers, MDA level and carbonyl content for macrolide antibiotics were found to be increasing in a dose dependent manner parallel to the loss of motility. Significant association between loss of mf motility and oxidative stress parameters points towards a putative role of oxidative rationale. In the present study, culture supernatants of both Tetracycline and Doxycycline also showed significantly higher nitric oxide levels compared to control and a significant positive association between this parameter and the anti-filarial effect was found. Similarity in the results obtained for both of these stress parameters indicate a close nexus of oxidative and nitrosative rationale in the direct antifilarial effect. NO appears to be of particular importance in host defense against intracellular pathogens [20]. An interaction between reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates brings forth synergy between the oxidative burst and NO mediated effects [21].

As discussed earlier that oxidant burst in the form of chemical mediators elaborated by the cells recruited to mount inflammatory response appears to play key role in mediation of direct antimicrobial effect [22]. Quite strikingly, DEC harnesses the innate inflammatory system in vivo to combat the filarial pathogen and the resultant effect is induced through possible oxidative mechanism. Moreover, it was also shown that nitric oxide is essential for the rapid sequestration of microfilariae by DEC [23]. With these evidential proofs coupled with our experimental results, the direct antifilarial effect might be envisaged as a function of oxidative and/or nitrosative rationale.

This small scale work unravels a novel mechanistic aspect of common macrolide antibiotic against filarial pathogen and hypothesizes that targeted oxidative and/or nitrosative stress may be utilized to formulate a new therapeutic strategy against this disorder.

Acknowledgments

Authors duly acknowledge the support from the repository project for filarial parasites and reagents, under the Research project grants from Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Govt. of India.

References

- 1.Fan PC. Diethylcarbamazine treatment of Bancroftian and Malayan filariasis with emphasis on side effects. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:399–405. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1992.11812684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burkot TR, Durrheim DN, Melrose WD, Speare R, Ichimori K. The argument for integrating vector control with multiple drug administration campaigns to ensure elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Filaria J. 2006;5:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King CL, Kumaraswami V, Poindexter RW, Kumari S, Jayaraman K, Alling DW, et al. Immunologic tolerance in lymphatic filariasis. Diminished parasite-specific T and B lymphocyte precursor frequency in the microfilaremic state. J Clin Investig. 1992;89(5):1403–1410. doi: 10.1172/JCI115729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nutman TB, Kumaraswami V. Regulation of the immune response in lymphatic filariasis: perspectives on acute and chronic infection with Wuchereria bancrofti in South India. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:389–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaren DJ, Worms M, Laurence B, Simpson M. Microorganisms in filarial larvae (Nematoda) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1975;69:509–514. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(75)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao RU. Endosymbiotic Wolbachia of parasitic filarial nematodes as drug targets. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoerauf A, Volkmann L, Nissen-Paehle K, Schmetz C, Autenrieth I, et al. Targeting of Wolbachia endobacteria in Litomosoides sigmodontis comparison of tetracyclines with chloramphenicol, macrolides and ciprofloxacin. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:275–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert J, Nfon CK, Makepeace BL, Njongmeta LM, Hastings IM, Pfarr KM, et al. Antibiotic chemotherapy of onchocerciasis: in a bovine model, killing of adult parasites requires a sustained depletion of endosymbiotic bacteria (Wolbachia species) J Infect Dis. 2005;192(8):1483–1493. doi: 10.1086/462426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Supali T, Djuardi Y, Pfarr KM, Wibowo H, Taylor MJ, Hoerauf A, et al. Doxycycline treatment of Brugia malayi-infected persons reduces microfilaremia and adverse reactions after diethylcarbamazine and albendazole treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1385–1393. doi: 10.1086/586753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maizels RM, Bundy DA, Selkirk ME, Smith DF, Anderson RM. Immunological modulation and evasion by helminth parasites in human populations. Nature. 1993;365(6449):797–805. doi: 10.1038/365797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanesa-Thasan N, Douglas JG, Kazura JW. Diethylcarbamazine inhibits endothelial and microfilarial prostanoid metabolism in vitro. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;49:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90125-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari YP, Krithika KN, Kulkarni S, Reddy MVR, Harinath BC. Detection of enzymes dehydrogenases and Proteases in Brugia malayi Filarial parasites. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2006;21(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02913060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahare KN, Anandhraman V, Meshram VG, Meshram SU, Gajalakshmi D, Goswami K, et al. In vitro effect of four herbal plants on the motility of Brugia malayi microfilariae. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satoh K. Serum lipoperoxidase in cerebrovascular disorders determined by new calorimetric method. Clin Chem Acta. 1978;90:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(78)90081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine RL, Garland D, Oliver CN, Amici A, Climent I, Lenz AG, et al. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:464–478. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waitumbi J, Warburg A. Phlebotomus papatasi saliva inhibits protein phosphatase activity and nitric oxide production by murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998;66(4):1534–1537. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1534-1537.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espey MG, Thomas DD, Miranda KM, Wink DA. Focusing of nitric oxide mediated nitrosation and oxidative nitrosylation as a consequence of reaction with superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(17):11127–11132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152157599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson J, Johnson BE. Clinical and laboratory studies of the photosensitizing potential of norfloxacin, a 4-quinolone broad-spectrum antibiotic. Br J Dermatol. 2006;128(3):285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermans PG, Hart CA, Trees AJ. In vitro activity of anti microbial agents against the endo symbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:659–663. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajan TV, Porte P, Yates JA, Keefer L, Shultz LD. Role of nitric oxide in host defense against an extracellular, metazoan parasite, Brugia malayi. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3351–3353. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3351-3353.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathan C. Specificity of a third kind: reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in cell signaling. J Clin Investig. 2003;111:769–778. doi: 10.1172/JCI18174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN. Acute and chronic inflammation. In: Robbins basic pathology, 8 ed. India: Elsevier; 2007. p. 31–58.

- 23.McGarry HF, Plant LD, Taylor MJ. Diethylcarbamazine activity against Brugia malayi microfilariae is dependent on inducible nitric-oxide synthase and the cyclooxygenase pathway. Filaria J. 2005;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]