Abstract

The present study was designed to compare the potential of turmeric and its active principle curcumin on T3-induced oxidative stress and hyperplasia. Adult male Wistar strain rats were rendered hyperthyroid by T3 treatment (10 μg · 100 g−1 · day−1 intraperitoneal for 15 days in 0.1 mM NaOH) to induce renal hyperplasia. Another two groups were treated similarly with T3 along with either turmeric or curcumin (30 mg kg−1 body weight day−1 orally for 15 days). The results indicate that T3 induces both hypertrophy and hyperplasia in rat kidney as evidenced by increase in cell number per unit area, increased protein content, tubular dilation and interstitial edema. These changes were accompanied by increased mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and superoxide dismutase activity without any change in catalase activity and glutathione content suggesting an oxidative predominance. Both turmeric and curcumin were able to restore the level of mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and superoxide dismutase activity in the present dose schedule. T3-induced histo-pathological changes were restored with turmeric treatment whereas curcumin administration caused hypoplasia. This may be due to lower concentration of curcumin in the whole turmeric. Thus it is hypothesized that regulation of cell cycle in rat kidney by T3 is via reactive oxygen species and curcumin reveres the changes by scavenging them. Although the response trends are comparable for both turmeric and curcumin, the magnitude of alteration is more in the later. Turmeric in the current dose schedule is a safer bet than curcumin in normalizing the T3-induced hyperplasia may be due to the lower concentration of the active principle in the whole spice.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, Kidney, Curcumin, Turmeric, Hyperplasia, Thyroid

Introduction

Turmeric powder is traditionally used in India as a coloring and flavoring spice in food as well as for medicinal purposes. Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) exhibits antitumor, anti-inflammatory and anti-infectious activities with low toxicity [1, 2]. The antioxidant or reactive oxygen scavenging properties have been associated with turmeric powder by itself and its individual lipid soluble component curcumin and the aqueous extract turmerin [3].

One of the most important effects of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) is the elevation of mitochondrial respiration, producing a hyper-metabolic state with excess generation of free radicals [4]. It has been shown that tissues in hyperthyroid rats exhibit low antioxidant capacity and high susceptibility to oxidative challenge [5, 6]. Oxidative stress from superoxide (O∙−2) and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) contributes to the development of renal insufficiency and in the pathogenesis of renal diseases, producing vascular, glomerular, tubular and interstitial injury [7]. Thyroxine has been reported to induce renal hypertrophy with a rise in the DNA content [8, 9]. However, there is a paucity of information on T3-induced oxidative damage to mammalian kidney in general and with respect to antioxidant treatment in particular. With this background the present investigation is designed to compare the effectiveness of turmeric and it active principle curcumin on T3-induced oxidative stress and hyperplasia in rat kidney.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatment

Two months old, young, healthy and sexually mature Wistar strain female rats (180–250 g) procured from National Facility for Laboratory Animals, National Institute of Nutrition (ICMR), Hyderabad, India were used in the present study. Animals were acclimatized to the laboratory conditions prior to experimentation. They were maintained in polypropylene cages under normal laboratory conditions with 12:12 h light:dark cycle and had free access to fresh food and tap water ad libitum [10].

Rats were randomly divided into five groups of 4 animals each according to the following treatment schedule, Group-I: (Control-I) No treatment, Group-II: (Control-II) administered 0.1 mM NaOH by intra-peritoneal injection (vehicle solution for T3), Group-III: (hyperthyroid) administered T3 at the rate of 10 μg × 100 g−1 body weight day−1 in 0.1 mM NaOH solution by intra-peritoneal injection for 15 days [11], Group-IV: administered with T3 as per above along with oral treatment of 30 mg turmeric powder kg−1 body weight in distilled water, Group-V: administered with T3 as per above along with oral treatment of 30 mg curcumin kg−1 in olive oil. Induction of hyperthyroidism was indicated by a loss in body weight by 15–30% [11]. Curcumin and T3 were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co, St Luise M.O., USA while turmeric rhizomes were collected from tribal farmers of Kandhamal district of Odisha (Eastern India), shed dried, pulverized and sieved before use.

Animal experiments were performed after approval of Institutional Ethical Committee in accordance with the ethical standards provided by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India.

Tissue Processing and Isolation of Mitochondria

Rats were killed by decapitation. Kidneys were dissected out quickly and were cleaned in ice-cold normal saline (0.9%, w/v) and pat dried on filter paper. The tissues were weighed and stored at −80°C until further processing. A 20% (w/v) homogenate of the kidney was prepared in phosphate buffer (50 mM pH 7.4) containing 0.25 M sucrose with the help of a motor driven glass Teflon homogenizer. The crude homogenate was filtered through two layers of cheesecloth and then the filtrate obtained was centrifuged at 600×g for 10 min at 4°C to precipitate nuclei and cellular debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 20 min at 4°C to separate mitochondrial pellet. The mitochondrial pellet obtained was washed three times in 1.15% KCl at 10,000×g for 5 min each at 4°C and dissolved in the same solution. The supernatant (postmitochondrial fraction) was taken directly for assay of catalase activity whereas after passing through Sephadex G-25 column it was used for assay of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. The mitochondrial fraction was used to measure lipid peroxidation (LPX). Protein content of all fractions was estimated by the method of Lowry et al. [12].

Assay of LPX

Lipid peroxidation was measured as thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) according to the method of Ohkawa et al. [13].

Assay of SOD and Catalase Activity

Superoxide dismutase activity was measured in the column passed supernatant according to the method of Das et al. [14]. Catalase activity was measured in the PMF by the method of Aebi [15] after treating with 0.17 M ethanol and 0.1% Triton X-100 for inhibition of complex-II formation and release of catalase from the peroxisomes [16]. Reduced glutathione (GSH) content was measured by Ellman’s reagent [17].

Histopathology

Thin slices of kidney tissue with cortex and medulla were fixed by immersion in sublimate formol (9 part formaldehyde:1 part saturated solution of mercury chloride), dehydrated in ascending series of ethanol, cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A minimum of 10 fields for each kidney slide were examined and assigned for severity of changes by an observer blinded to the treatments of the animals. Severity of changes were scored using the signs, namely none (+), mild (++) and severe (+++).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. The inter-group variation was measured by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s New Multiple Test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

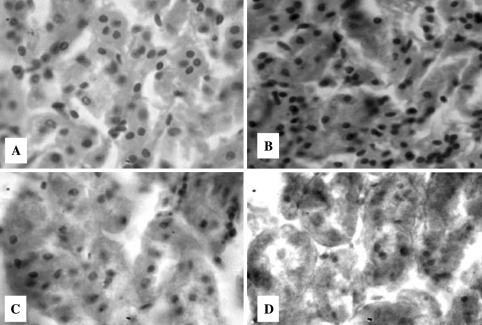

The results of the present investigation clearly suggest that hyperthyroidism condition induced by 15 days exposure of rats to T3 resulted in marked hypertrophy and hyperplasia in rat kidney (Table 2 and Fig. 1) as reported previously [8, 9, 18] with a rise in the mitochondrial and cytosolic protein content (Table 1). In fact, Bradley et al. [19] reported a rise in the renal mitotic index and Stephan et al. [8] reported an elevation in the DNA content of the kidney in response to thyroxin-induced renal hypertrophy. Similarly, Ohmura et al. [9] have demonstrated through BrdUrd immunohistochemistry that T3 activates cell proliferation in proximal tubular epithelial cells of the kidney, but not the glomeruli and opined that T3 evokes this response through genes that regulate cell proliferation in target cells through receptor-mediated path ways and initiate cellular DNA synthesis. Therefore, hyperthyroidism-induced renal hypertrophy is not only due to interstitial edema or tubular dilation but also due to the increase in number of tubular cells and glomeruli. The high level of LPX in kidney mitochondrial fraction of hyperthyroid rats (Table 1) clearly suggests induction of oxidative stress. This may be due to increase in respiration rate of the tissue. Thyroid hormones are known to play a pivotal role in mitochondrial respiration of cells. Increased rate of mitochondrial respiration as a consequence of hyperthyroidism may alter the mitochondrial respiratory chain activity and thereby, elevate the generation of superoxide radicals as a consequence of increase in cellular metabolism [20]. Superoxide dismutase dismutates superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxides, which is further, neutralized by catalase and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) enzymes of cells [21]. Therefore, the augmentation in superoxide release may be the causative factor for increased SOD activity in response to T3 treatment. However, our results are not in conformity with the previous report by Moreno et al. [22] who reported a decrease in the enzyme activity in response to T4-induced hyperthyroidism. The discrepancy in the results might be due to the nature of the hormone used for induction of hyperthyroidism. Increased SOD activity without induction of catalase in kidney in response to hyperthyroidism (Table 1) may account for the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in the kidney which is capable of generating highly reactive hydroxyl radical (∙OH), an initiator of LPX via Fenton reaction [21]. Although the activity of GPx is not measured in the present study, the unaltered level of its principal substrate GSH indirectly suggest that probably this enzyme is not induced in response to T3 treatment, thus, further eliminating the chance of neutralization of hydrogen peroxide and other organic peroxides.

Table 2.

Effect of turmeric and curcumin on T3-induced alterations in histological parameters in rat kidney

| Parameters | C-I | C-II | T3 | T3 + Turmeric | T3 + Curcumin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of tubules | + | + | +++ | + | − |

| Tubular dilation | + | + | +++ | +/++ | − |

| Interstitial oedema | + | + | +++ | +/++ | − |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4) taken in duplicates. Score: Changes with respect to control: none (+), mild increase (++), severe increase (+++), decrease (−). C-I Control-I (normal), C-II Control-II (vehicle treated)

Fig. 1.

Representative images of T.S. of rat kidney (×400) stained with hematoxylene and eosine showing the effects of T3, turmeric and curcumin. a Control-I, b T3 treated, c T3 + Turmeric, d T3 + Curcumin. Control-II is not given since no difference was observed between Control-I and II. C-I Control-I (normal), C-II Control-II (vehicle treated)

Table 1.

Effect of turmeric and curcumin on T3-induced alterations in biochemical parameters of rat kidney

| Parameters | Control-I | Control-II | T3 | T3 + Turmeric | T3 + Curcumin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | |||||

| Mito | 9.50 ± 0.71a | 9.86 ± 3.25a | 15.62 ± 1.51b | 12.58 ± 1.10a,b | 9.30 ± 1.99a |

| PMF | 92.70 ± 6.43a | 92.64 ± 3.29a | 125.12 ± 7.83b | 111.36 ± 7.96b | 94.32 ± 4.13a |

| LPX | 1.38 ± 0.15a | 1.32 ± 0.18a | 1.89 ± 0.09b | 1.33 ± 0.38a | 1.26 ± 0.31a |

| SOD | 10.56 ± 0.61a | 10.35 ± 0.52a | 15.10 ± 1.71b | 9.37 ± 0.56a | 8.84 ± 0.66a |

| CAT | 1.44 ± 0.23 | 1.30 ± 0.16 | 1.38 ± 0.23 | 1.29 ± 0.25 | 1.23 ± 0.21 |

| GSH | 0.74 ± 0.07 | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.65 ± 0.05 |

Mito Mitochrondrial fraction, PMF Post-1 mitochondrial fraction, LPX Lipid peroxidation (nmol mg protein), SOD Superoxide dismutase (Units.mg protein−1), CAT Catalase (μkat mg protein-1), GSH Reduced glutathione (μmol g tissue−1)

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 4) taken in duplicates; aSignificantly different from controls; bSignificantly different from T3

It has been opined that ROS production in cells leads to an intracellular tyrosine phosphorylation cascade by two district protein families—the Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) and the redox sensitive kinases [23]. The MAPK signaling pathways modulate gene expression, mitosis, proliferation, motility, metabolism, and programmed cell death [24]. Furthermore, curcumin is reported to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in T lymphocytes and Jurkat cells [25, 26]. Since in the present study, T3 administration had shown a 37% augmentation in mitochondrial LPX level indicating ROS predominance over antioxidants (Table 1), it is hypothesized that the increased ROS level as a consequence of T3-induced hyper-thyroidism may be responsible for the increased cell proliferation probably via MAPK and/or redox active kinases signaling pathways. Nevertheless, the trend reversal by extraneous administration of antioxidant (here curcumin and turmeric) administration implies the role of ROS in cell proliferation by T3. Further study on this signaling cascade may confirm the pathway.

Curcumin has been reported to show antioxidant properties by one or more of the following interactions: Scavenging or neutralizing free radicals by oxygen quenching and making it less available for oxidative reaction and/or inhibition of oxidative enzymes like cytochrome P450, interacting with oxidative cascade and preventing its outcome and chelating and disarming oxidative properties of metal ions such as iron [27–29]. Dietary curcumin is reported to inhibit superoxide anion generation and hydroxyl radical generation through preventing the oxidation of Fe2+ in Fenton’s reaction, which generates ∙OH radicals [30]. Therefore, the decrease in ROS threshold in the curcumin treated hyperthyroid animals could be the causative factor for reduction of T3-induced hyperplasia to below normal level by induction of apoptosis (Table 2) whereas, turmeric which is a mixture of many different compounds have lower concentration of curcuminoids which in turn, has a reduced apoptotic potential. Recently Gilani et al. [31] have reported that curcumin does not share all effects of turmeric in gastrointestinal and respiratory disorders. In conclusion it is suggested that turmeric and curcumin probably regulate cell proliferation and cell death by modulating cellular oxidant/antioxidant status induced by T3. And the profound effect observed in curcumin treated hyperthyroid rats in comparison to turmeric treated counterparts may be due to lower concentration of curcumin since in both the cases the response of the studied parameters followed similar pattern. Thus, use of turmeric as a regular food coloring and flavoring spice in food is safer than its pure active principle curcumin.

Acknowledgments

Financial assistance to the Departments from the Department of Biotechnology and University Grants Commission, Government of India is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Brouet I, Oshimima H. Curcumin, an antitumor promoter and anti-inflammatory agent, inhibits induction of nitric oxide synthase in activated macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;206:533–540. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duvoix A, Blassius R, Delhalle S, Schnekenburger M, Morceau F, Henry E, Dicato M, Diederich M. Chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of curcumin. Cancer Lett. 2005;233:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohly HHP, Taylor A, Angel MF, Saahudeen AK. Effect of turmeric, turmerin and curcumin on H2O2 induced renal epithelia (LLC-PK1) cell injury. FRBM. 1988;24:49–54. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mano T, Sinohara R, Sawai Y, Oda N, Nishida Y, Mokunu T, Kotake M, Hamada M, Masunaga R, Nakai A, Nagasaka A. Effects of thyroid hormne on coenzyme Q and other free radical scavengers in rat heart muscle. J Endocrinol. 1995;145:131–136. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1450131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahoo DK, Roy A, Bhanja S, Chainy GBN. Experimental hypothyroidism induced oxidative stress and impairment of antioxidant defence system in rat testis. Indian J Exp Biol. 2005;43:1058–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vendilti P, Balestrieri M, Dimeo S, Deleo T. Effect of thyroid state on lipid peroxidation, antioxidant defences and susceptibility to oxidative stress in rat tissues. J Endocrinol. 1997;155:151–157. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1550151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcox CS. Reactive oxygen species: roles in blood pressure and kidney function. Curr Hyperten Rep. 2002;4:160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11906-002-0041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephen F, Reville P, Laharpe F, Koll-Back MH. Impairment of renal hypertrophy by hypothyroidism in the rat. Life Sci. 1982;30:623–631. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohmura T, Katyal SL, Locker J, Ledda-Columbano GM, Columbano A, Shinozuka H. Induction of cellular DNA synthesis in the pancreas and kidneys of rats by peroxisome proliferators, 9-cis retinoic acid, and 3,3′,5-triiodo-lthyronine. Cancer Res. 1997;57:795–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samanta L, Chainy GBN. Comparison of hexachlorocyclohexane induced oxidative stress in testis of immature and adult rats. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1997;118C:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(97)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorothy APL, Reinhard LL. Heart mitochondrial function in acute and in chronic hyperthyroidism in rats. Circ Res. 1969;25:171–181. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowry OH, Rrosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okhawa H, Ohisi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissue by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anals Biochem. 1979;95:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das K, Samanta L, Chainy GBN. A modified spectrophotometric assay of superoxide dismutase using nitrite formation by superoxide radicals. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2000;37:201–204. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aebi H. Catalase, In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods in enzymatic analysis vol. 2 New York: Academic Press; 1974:673–8.

- 16.Cohen G, Dembiec D, Marcus J. Measurement of catalase activity in tissue extracts. Anals Biochem. 1970;34:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura RM, Miyada DSM, Cockett AT, Moyer DL. Thyroid and pituitary gland activity during compensatory renal hypertrophy. Experientia, 1964;20:694–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bradley SE, Stephen F, Coelho JB, Reville P. The thyroid and the kidney. Kidney Int. 1974;6:346–365. doi: 10.1038/ki.1974.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mori T, Cowley AW. Renal oxidative stress in medullary twick ascending limbs produced by elevated NaCl and glucose. Hypertension. 2004;43:341–346. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113295.31481.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno JM, Rodrigue-Gomez I, Wangensteen R, Osuna A, Bueno P, Vragas F. Cardiac and renal antioxidant enzymes and effects of tempol in hyperthyroid rats. Am J Physiol 2005;289:E776–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Behrend L, Henderson G, Zwacka RM. Reactive oxygen species in oncogenic transformation. Biochem Soc Transact. 2003;31:1441–1444. doi: 10.1042/BST0311441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress and signal transduction. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikora E, Bielak-Zmijewska A, Piwockq K, Skienski J, Radziszewska E. Inhibition of proliferation and apoptosis of human and rat T lymphocytes by curcumin, a curry pigment. Bio-chem Pharmacol. 1997;54:899–907. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Piwocka K, Jaruga EI, Skierski J, Gradzka I, Sikora E. Effect of glutathione depletion on caspase-3 independent apoptotic pathway induced by curcumin in Jurkat cells. FRBM. 2001;31:670–678. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soudamini KK, Unnikrishnan MC, Soni KB, Kuttan R. Inhibition of lipid peroxidation and cholesterol levels in mice by curcumin. Ind J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;36:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unnikrishnan MK, Rao MN. Inhibition of nitric oxide-induced oxidation of hemoglobin by curcuminoids. Pharmazie. 1995;50:490–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sreejayan Rao MN. Curcuminoids as potent inhibitors of lipid peroxidation. J Pharmacol. 1994;46:1013–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1994.tb03258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy ACP, Lokesh BR. Effect of dietary turmeric (Curcuma longa) on iron induced lipid peroxidaton in the rat liver. Food Chem Toxicol. 1994;32:279283. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(94)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilani AH, Shah AJ, Ghayur MN, Majeed K. Pharmacological basis for the use of turmeric in gastrointestinal and respiratory disorders. Life Sci. 2005;79:3089–3105. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]