Abstract

SR proteins are essential splicing factors whose function is controlled by multi-site phosphorylation of a C-terminal domain rich in arginine-serine repeats (RS domain). The protein kinase SRPK1 has been shown to polyphosphorylate the N-terminal portion of the RS domain (RS1) of the SR protein ASF/SF2, a modification that promotes nuclear entry of this splicing factor and engagement in splicing function. Later, dephosphorylation is required for maturation of the spliceosome and other RNA processing steps. While phosphates are attached to RS1 in a sequential manner by SRPK1, little is known about how they are removed. To investigate factors that control dephosphorylation, region-specific mapping of phosphorylation sites in ASF/SF2 was monitored as a function of the protein phosphatase PP1. We showed that ten phosphates added to the RS1 segment by SRPK1 are removed in a preferred N-to-C manner, directly opposing the C-to-N phosphorylation by SRPK1. Two N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) in ASF/SF2 control access to the RS domain and guide the directional mechanism. Binding of RNA to the RRMs protects against dephosphorylation suggesting that engagement of the SR protein with exonic splicing enhancers can regulate phosphoryl content in the RS domain. In addition to regulation by N-terminal domains, phosphorylation of the C-terminal portion of the RS domain (RS2) by the nuclear protein kinase Clk/Sty inhibits RS1 dephosphorylation and disrupts the directional mechanism. The data indicate that both RNA-protein interactions and phosphorylation in flanking sequences induce conformations of ASF/SF2 that increase the lifetime of phosphates in the RS domain.

Keywords: protein kinase, protein phosphatase, phosphorylation, splicing, SR protein

Long precursor mRNA is converted to shorter mRNA strands for protein translation at a macromolecular complex (spliceosome) composed of several snRNPs (U1, U2, U4, U5, & U6) and more than one hundred auxilliary proteins.1 Among the latter group, the SR proteins have emerged as an essential family of splicing factors that play important roles establishing the 5' and 3' splice sites, recruiting the U4/U6•U5 tri-snRNP and enhancing the second catalytic step in splicing.2; 3; 4; 5 Traditional SR proteins derive their name from a C-terminal domain rich in arginine-serine repeats (RS domains) that can vary in length between about 50 to 300 residues.6 They also contain one or two N-terminal RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) that bind to splicing enhancer sequences on mRNA and facilitate spliceosome assembly.7 The RS domains are thought to serve as critical protein-protein adaptors and undergo rounds of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation during spliceosome maturation. Two protein kinase families (SRPK and CLK) play vital roles in phosphorylating SR proteins and controlling function. Recent studies have shown that the phosphorylation of about 10 serines in the N-terminal region of the RS domain (RS1) by SRPK1 leads to translocation of ASF/SF2 from the cytoplasm to nuclear speckles8; 9 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, Clk/Sty, a member of the CLK family of nuclear protein kinases, phosphorylates additional serines in the C-terminal region of the RS domain (RS2) and causes ASF/SF2 to disperse within the nucleus.8 While this model explains the subcellular localization data, in vitro splicing studies have shown that both hypo- and hyper-phosphorylation can inhibit splicing activity suggesting that the link between phosphorylation and splicing function is complex and partial phosphorylation states may be important.10

Figure 1. Binding properties of PP1 and SRPK1 to ASF/SF2.

A) Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the RS1 segment in the RS domain of ASF/SF2 by SRPK1 and PP1. Filled circles represent phosphates. B) Steady-state kinetics for PP1 & SRPK1. PP1 (15 nM) is mixed with 0–1 μM His-tagged ASF/SF2, pre-phosphorylated by SRPK1 and initial velocities are measured and plotted as function of total p-ASF/SF2. SRPK1 (1 nM) is mixed with 0–1 μM His-tagged ASF/SF2 and the initial velocities are measured and plotted as function of total ASF/SF2. The data are fit to a Km of 1000 ± 300 nM and keat of 2 ± 0.6 min−1 for p-ASF/SF2 with PP1 and a Km of 190 ± 30 nM and kcat of 43 ± 2 min−1 for ASF/SF2 with SRPK1. C) Inhibition of SRPK1 by PP1. A complex of ASF/SF2 (0.2 μM) and SRPK1 (0.5 μM) is incubated with 0 (●), 0.5 (◯), 1 (▲), and 3 μM (△) PP1 before the reaction is started with 32P-ATP. The number of phosphorylated sites is plotted as a function of time. D) Pull-down Binding Assays. GST-ASF/SF2 is mixed with equal amounts of PP1 (left panel) or SRPK1 (right panel) and then pulled down with G-agarose resin. An asterisk designates an impurity in the GST-ASF/SF2 preparation that migrates below PP1.

Many protein kinases are capable of catalyzing multi-site phosphorylation. Src phosphorylates 10 or more tyrosines in the focal adhesion protein Cas in a nonsequential, processive manner.11 The budding yeast cyclin-CDK complex Pho80-Pho85 phosphorylates 5 serines in the transcription factor Pho4 in a preferred order, semiprocessive manner.12 The dual specific protein kinase MEK activates MAPK by sequentially phosphorylating Tyr185 prior to Thr183 in the activation loop of MAPK using a distributive mechanism.13; 14; 15 Interestingly, these two phosphates are removed in the same order as they are added by the dual specific phosphatase MKP3.16 Despite the high number of protein kinases capable of multi-site phosphorylation, there is still insufficient data on how these phosphates are added and how they are removed by the phosphatases. We showed previously that SRPK1 phosphorylates the RS1 segment of ASF/SF2 using a C-to-N directional mechanism17 and that several of these phosphates are added in a processive manner.18; 19; 20 Although the RRMs in ASF/SF2 help guide this sequential phosphorylation mechanism, local sequences in the RS domain are sufficient to direct RS1 phosphorylation. In fact, both the regiospecificity and efficiency of ASF/SF2 phosphorylation by SRPK1 has been shown to depend only on the Arg-Ser content with long repeats such as in RS1 being strongly favored over shorter ones in the RS2 segment.21 In this study, we investigated how these phosphates are removed by PP1 using protease footprinting techniques. We found that the RS1 segment is dephosphorylated by PP1 in the opposing N-to C-direction. Unlike SRPK1, the N-terminal RRMs and their engagement with exonic splicing enhancer sequences negatively regulate dephosphorylation. PP1 activity is further down-regulated by phosphorylation of the RS2 segment under the control of Clk/Sty. Since phosphorylation and dephosphorylation appear essential for splicing activity, these studies provide a means for better understanding the structural components that influence the lifetimes of phosphates on the RS domains of SR proteins.

Results

PP1 Interacts Dynamically With ASF/SF2

To investigate how PP1 interacts with ASF/SF2, we initially performed steady-state kinetic experiments. To attain pre-phosphorylated substrate for PP1, 1 μM ASF/SF2 was reacted with 0.1 μM SRPK1 and limiting ATP (16 μM) and then diluted to achieve a desired p-ASF/SF2 concentration for assay. This low level of ATP is sufficient to attach 10 phosphates onto the RS1 segment of the RS domain at the end of the reaction (Fig. 1A). While ASF/SF2 binds SRPK1 with high affinity in pull-down assays, incubation of the complex with ATP leads to dissociation (Fig. 1D, right panel), suggesting that the small amount of SRPK1 in the pre-phosphorylation reaction will not bind to PP1 and interfere with the subsequent PP1 reaction. Dephosphorylation in the presence of catalytic amounts of PP1 was then monitored and the initial velocities were plotted as a function of total p-ASF/SF2 (Fig. 1B). For comparison, the initial velocities for ASF/SF2 phosphorylation were measured as a function of total substrate concentration using SRPK1. We found that kcat/Km for SRPK1 is about 150-fold larger than that for PP1 (Fig. 1B). This difference is due to a 5-fold lower Km and 30-fold higher kcat for ASF/SF2 and SRPK1 compared to PP1 and p-ASF/SF2 (Fig. 1B). Since these steady-state kinetic studies suggest that PP1 may bind to its substrate with lower affinity than SRPK1 and its substrate, we then assessed whether PP1 could compete with SRPK1 for the RS domain of ASF/SF2. In single turnover analyses (0.5 μM SRPK1, 0.2 μM ASF/SF2), we found that PP1 did not significantly influence the progress curve up to 1 μM PP1 and inhibited the initial phase only at 3 μM PP1 (Fig. 1C). To further investigate the interaction of ASF/SF2 with PP1, pull-down assays were performed (Fig. 1D). Although GST-ASF/SF2 readily interacts with SRPK1 (right panel), very little PP1 is pulled down (left panel). An impurity in the GST-ASF/SF2 preparation migrates near the PP1 band but can be differentiated in the pull-down assay. Overall, the data imply that the interaction of ASF/SF2 with PP1 is weaker than that with SRPK1.

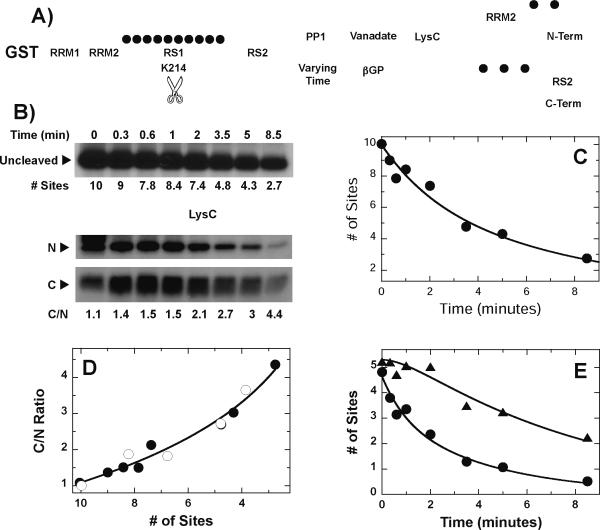

RS1 Dephosphorylation By PP1 Is Directional

We showed previously that SRPK1 phosphorylates the RS1 segment in ASF/SF2 in a C-to-N direction.17; 22 We would now like to address how these phosphates are removed. To accomplish this goal, we monitored the dephosphorylation of a cleavable His-tagged form of ASF/SF2 [clASF(214)].17; 20; 21 This substrate contains several Lys-to-Arg mutations in RRM2 and a single Arg-to-Lys mutation in the center of RS1 (R214K) so that upon proteolysis with LysC, clASF(214) can be separated into two fragments that are readily identifiable by molecular weight and represent the N- and C-terminal halves of RS1 (Fig. 2A) We showed previously that clASF(214) binds with high affinity to and is readily phosphorylated by SRPK1.17 Also, in steady-state kinetic experiments we showed that SRPK1-phosphorylated clASF(214) is an efficient substrate for PP1 displaying a 4-fold higher kcat/Km compared to wild-type ASF/SF2 (data not shown). To determine how the phosphates from RS1 are removed, cl-ASF(214), pre-phosphorylated at 10 sites by SRPK1 and limiting ATP, is treated with PP1 (250 nM) for varying times (0–8 min) before the reaction is stopped with SDS (Fig. 2B). To generate N- and C-terminal fragments as a function of dephosphorylation, we could not use SDS as a quenching agent as this would interfere with the subsequent LysC cleavage step. Instead, the PP1 reaction was stopped using vanadate and β glycerol phosphate [βGP] which are compatible with LysC. We found that the time-dependent dephosphorylation is the same regardless of quench method (Fig. 2C), implying that no further dephosphorylation occurs after vanadate/βGP treatment in the 2-hour delay period needed to cleave the substrate using LysC and that the small amounts of SRPK1 needed for pre-phosphorylation cannot use any residual ATP to further phosphorylate clASF(214). Prior to the addition of PP1, the ratio of 32P in the N- and C-terminal fragments from p-clASF(214) (C/N ratio) is 1.2, a value reflecting the relative number of phosphorylatable serines in the N- and C-terminal fragments of RS1.17 As PP1 lowers the phosphoryl content from 10 to 3, the C/N ratio increases by about 4-fold suggesting that the phosphates are preferentially removed from the N- rather than the C-terminus in RS1 (Fig. 2B,D).

Figure 2. RS1 Segment of ASF/SF2 is Sequentially Dephosphorylated by PP1.

A) Cleavage Strategy. The cleavage vector, clASF(214), phosphorylated at 10 sites by SRPK1, is treated with PP1 for varying time, the reaction is stopped using vanadate/βGP and the protein is cleaved into two large fragments using LysC. B) Time-Dependent Cleavage. Phosphorylated clASF(214) is reacted with PP1 (250 nM) for varying times and the reaction is stopped using SDS loading buffer. N- and C-terminal fragments derived from vanadate/βBP-quenched reactions and LysC treatment are resolved on SDS-PAGE. C) Dephosphorylation kinetics of clASF(214). Reaction is stopped using SDS (●) or vanadate/βBP (◯). The SDS-quenched time samples were fit to a single exponential function with a rate constant of 0.15 ± 0.0085 min−1 and an amplitude of 9.8 ± 0.15 sites. D) C/N Plot. The ratios of C- and N-terminal fragments resulting from LysC treatment and determined by autoradiography are plotted as a function of sites dephosphorylated by PP1. E) Time-dependent changes in the N- (●) and C-terminal (▲) fragments. The time-dependent changes in the N-terminal fragments were fit to a single exponential function with a rate constant and amplitude of 0.27 ± 0.02 min−1 and 4.3 ± 0.20 sites and those for the C-terminal fragments were fit to equation (1) to obtain values for kL and k1 of 0.64 ± 0.10 and 0.13 ± 0.04 min−1 with an amplitude of 5.4 ± 0.22 sites.

Using the time-dependent decline in total phosphoryl content and the C/N ratio we were able to calculate the phosphoryl contents of the two portions of RS1 as a function of time. The N-terminal region is rapidly dephosphorylated while the dephosphorylation of the C-terminal fragment of RS1 displays a noticeable lag phase (Fig. 2E). Although PP1 quickly removes about 2 phosphates from the N-terminal fragment in the first 2 minutes, the phosphoryl content of the C-terminal fragment is mostly unaffected during this time. These data are consistent with a two-step, sequential mechanism in which the dephosphorylation step of the C-terminus of RS1 is preceded by a noncatalytic step where no phosphates are removed. The data were fit to a sequential kinetic model using equation (1) with an initial rate constant for the first step (kL) of 0.64 min−1 followed by a second step rate constant of 0.13 min−1 (Fig. 2E). The dephosphorylation rate constant for the second step is only 2-fold slower than the rate constant for N-terminal dephosphorylation (0.27 min−1) indicating that the intrinsic rate of phosphate removal in the two fragments is not significantly different. Instead, C-terminal dephosphorylation appears much slower owing to the initial lag step. Taken together, the data indicate that dephosphorylation of SRPK1-phosphorylated RS1 occurs in an N-to-C-terminal sequential manner.

RS1 Dephosphorylation Order Is An Intrinsic Property of ASF/SF2

Since the dephosphorylation kinetics were determined using a C-terminal His-tagged construct that might interact with PP1 and impact regiospecificities, we generated a new cleavage vector lacking this tag. The new vector [clGST-ASF(214)] contains an N-terminal GST and the same mutations in RRM2 and the RS domain as clASF(214) and generates similar cleavage products upon LysC treatment (Fig. 3A,B). This new cleavage construct, pre-phosphorylated by SRPK1, is dephosphorylated by PP1 at a somewhat slower rate than clASF(214) so that a higher concentration of PP1 (1 μM) was used in these experiments to achieve a comparable dephosphorylation rate constant as clASF(214) (Fig. 3B,C). Treatment of clGST-ASF(214) with LysC after varying incubation times with PP1 generated N- and C-terminal fragments whose relative phosphoryl contents (C/N ratios) change in a manner similar to that for clASF(214) (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the disappearance of the N- and C-terminal fragments follows the same sequential pattern as that for clASF(214) with similar rates constants (Fig. 3E). While the N-terminus is readily dephosphorylated, the C-terminal fragment experiences a lag phase prior to dephosphorylation. We next wished to address whether any potential substrate-substrate interactions or the presence of small amounts of SRPK1 and ATP could affect the directional reaction. To accomplish this, we immobilized phosphorylated clGST-ASF(214) on glutathione agarose beads and washed extensively to remove any SRPK1 and residual 32P-ATP before dephosphorylating with PP1 and then generating the N- and C-terminal fragments using LysC. As shown in Fig. 3D, the C/N ratio rises in an identical manner during dephosphorylation as the non-immobilized substrate suggesting that a directional pathway is still observed. The combined data indicate that the N-to-C directional dephosphorylation mechanism for RS1 is not a result of the affinity tag, potential substrate-substrate interactions, SRPK1 or residual ATP but rather is an intrinsic property of the SR protein.

Figure 3. Dephosphorylation Order of ASF/SF2 is Construct Independent.

A) Cleavage Strategy for GST Construct. The cleavage vector, clGST-ASF(214), phosphorylated at 10 sites by SRK1, is treated with PP1 for varying time, the reaction is stopped using vanadate/bGP and the protein is cleaved into two large fragments using LysC. B) Time-Dependent Cleavage. Phosphorylated clGST-ASF(214) is reacted with PP1 for varying times and the reaction is stopped using SDS. N- and C-terminal fragments derived from vanadate/bGP-quenched reactions and LysC treatments are resolved on SDS-PAGE. C) Dephosphorylation kinetics of clGST-ASF(214). The SDS-quenched time samples were fit to a single exponential function with a rate constant and amplitude of 0.16 ± 0.018 min−1 and 10 ± 0.32 sites. D) C/N Plot. The ratios of C- and N-terminal fragments resulting from LysC treatment and determined by autoradiography are plotted as a function of sites dephosphorylated (●). The C/N values for SRPK1-phosphorylated clGST-ASF(214) immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads, washed, dephosphorylated using PP1 and then cleaved by LysC are also shown (◯). E) Time-dependent changes in N- (●) and C-terminal (▲) fragments. The disappearance of the N-terminal fragment was fit to a rate constant of 0.36 ± 0.040 min−1 with an amplitude of 4.7 ± 0.22 sites. The disappearance of the C-terminal fragment was fit to equation (1) to obtain values for kL and k1 of 1.0 ± 0.36 and 0.12 ± 0.037 min−1 with an amplitude of 5.2 ± 0.20 sites.

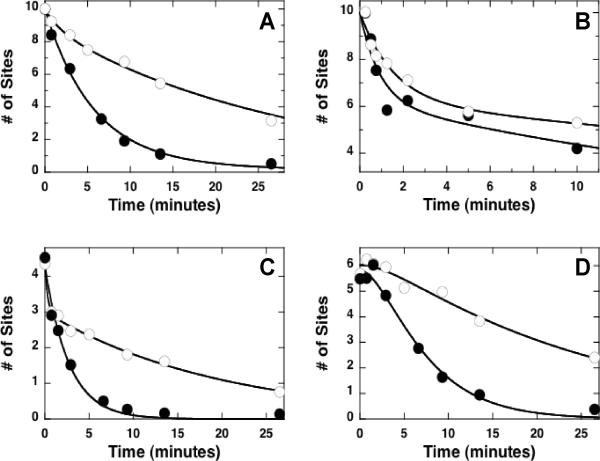

Dephosphorylation of the N- and C-Termini in RS1 Are Coupled

Having shown that PP1 directionally dephosphorylates RS1, we next wished to address whether phosphates in the N-terminus of RS1 guide C-terminal dephosphorylation. To accomplish this, we studied the dephosphorylation of RS1 as a function of initial N-terminal phosphorylation. Since SRPK1 adds phosphates onto RS1 in a C-to-N direction, we can generate a form of clASF(214) that is mostly phosphorylated in the C-terminus and sparsely phosphorylated in the N-terminus using ATP limitation experiments. To accomplish this, clASF(214) was phosphorylated using stoichiometric SRPK1 (500 nM) and limiting ATP (6 & 3 μM) which generates RS1 phosphorylated at either 10 or 5 sites (Fig 4A). Stoichiometric SRPK1 and limiting ATP are required for partial phosphorylation of RS1 as the enzyme does not readily dissociate until about 5–8 serines are modified.17; 21 Both the 10- and 5-site phosphoforms (10P & 5P) are rapidly dephosphorylated by PP1 at similar rate constants (Fig. 4B) and their C/N ratios increase in line with a directional mechanism (Fig. 4C). The N-terminal fragments disappear at the same rate constants whether 1 or 4 initial phosphates are present in this fragment (Fig. 4D). The dephosphorylation of the C-terminal fragment observes the expected lag phase although kL is about 4-fold faster when the N-terminal region is only weakly phosphorylated (0.65 vs. 2.9 min−1; Fig. 4E). The initial phosphoryl content of the C-terminal fragment of the 5P form is about 25% lower than that of the 10P form suggesting that SRPK1 dissociates occasionally and departs from a fully directional mechanism, a phenomenon observed in previous studies.21 Nonetheless, the lag period is much shorter when the N-terminus is weakly phosphorylated at only one site. This phenomenon is consistent with the longer time required to remove the N-terminal phosphates in 10P compared to 5P (Fig. 4D) before PP1 can act on the C-terminal phosphates. The dephosphorylation of the 10P form was performed under conditions where p-clASF(214) is 2-fold higher than PP1 which compares to conditions in Figures 2 & 3 where p-clASF(214) is 2.5-fold lower than PP1. Since we observe the same mechanism over a wide p-clASF(214):PP1 ratio (0.4–2) and the substrate and enzyme concentrations are 2-3-fold lower than the Km, the directional reaction is not the result of binding more than one phosphatase molecule per substrate. The data imply that the phosphoryl content of the N-terminal portion of RS1 affects the rate at which the C-terminus is dephosphorylated in line with a sequential N-to-C reaction.

Figure 4. Effects of N-terminal Phosphoryl Content on C-terminal Dephosphorylation Rates in RS1.

A) 10P and 5P forms of clASF(214). Reactions are conducted using stoichiometric SRPK1 and clASF(214) (500 nM) and 6 or 3 μM 32P-ATP for 10P and 5P forms. B) Dephosphorylation kinetics of the 10P (●) and 5P (◯) forms of clASF(214). Reactions are stopped using SDS and the data fit to single exponential functions with rate constants and amplitudes of 0.32 ± 0.028 min−1 and 10 ± 0.34 sites for the 10P form and 0.28 ± 0.025 min-1 and 5.3 ± 0.22 sites for the 5P form. C) C/N Plot. The ratios of C- and N-terminal fragments resulting from LysC treatment and determined by autoradiography are plotted as a function of sites dephosphorylated for the 10P (●) and 5P (◯) forms of clASF(214). D) Time-dependent changes in the N-terminal fragment for 10P (●) and 5P (△) forms of clASF(214). The data are fit to a single exponential function to obtain rate constants and amplitudes of 0.77 ± 0.039 min−1 and 3.8 ± 0.093 sites for the 10P form and 0.96 ± 0.093 min−1 and 0.84 ± 0.040 sites for the 5P form. E) Time-dependent changes in the C-terminal fragment for 10P (●) and 5P (△) forms of clASF(214). The time-dependent changes in C-terminal fragments were fit to a sequential dephosphorylation model using equation (1) to obtain values of kL, k1 and total amplitudes of 0.65 ± 0.070 min−1, 0.42 ± 0.043 min−1, and 6.4 ± 0.33 sites, respectively, for the 10P form and of 2.9 ± 0.85 min−1, 0.32 ± 0.040 min−1, and 4.7 ± 0.22 sites, respectively, for the 5P form.

RRMs Influence the Order of RS Domain Dephosphorylation

We next addressed whether the dephosphorylation preference in RS1 is guided by the RRMs or whether it is an innate function of the RS domain. To address this issue we studied the dephosphorylation mechanisms of two cleavage vectors [cl-ΔRRM1(214) & cl-RS-RRM2(214)] lacking either one or both N-terminal RRMs (Fig. 5A). It was shown previously that both constructs are good substrates for SRPK1 and can be cleaved into N- and C-terminal fragments by LysC with their respective phosphoryl contents reflecting the predicted number of RS repeats modified by SRPK1.21 Since we noticed that cl-RS-RRM2(214) was dephosphorylated very rapidly relative to clASF(214), we performed further dephosphorylation experiments at lower PP1 (125 nM). Removal of RRM1 in cl-ΔRRM1(214) did not significantly affect dephosphorylation relative to clASF(214) although the first phosphate appeared highly sensitive to PP1 treatment (Fig. 5B,C). Removal of both N-terminal RRMs in cl-RS-RRM2(214) led to increased phosphatase sensitivity relative to clASF(214) (Fig. 5B,C). These findings suggest that although the RRM pair shields the RS domain from dephosphorylation, RRM2 appears to play a larger role in this phenomenon. Unlike clASF(214), the C/N ratios of cl-ΔRRM1(214) & cl-RS-RRM2(214) do not change substantially as a function of dephosphorylation by PP1 (Fig. 5D). For cl-ΔRRM1(214), the disappearance of the N- and C-terminal fragments are distinct from those for cl-ASF(214). The C-terminal fragment for cl-ΔRRM1(214) does not appear to have a lag phase and although the first phosphate is quickly removed from the N-terminal fragment, the remaining phosphates are removed at about the same rate as that for the C-terminal phosphates. For cl-RS-RRM2(214), the first phosphate in both the N- and C-terminal fragments is rapidly removed while the remaining phosphates are removed more slowly and at similar rate constants. Overall, the data imply that RRMs play an important role in controlling the N-to-C dephosphorylation mechanism of ASF/SF2 and serve a protective role against the actions of PP1.

Figure 5. RRMs Influence the Dephosphorylation Order of the RS Domain of ASF/SF2.

A) Cleavage Constructs. B) Time-Dependent Cleavage. SRPK1-phosphorylated cl-ΔRRM1(214) and cl-RS-RRM2(214) are reacted with PP1 (125 nM) for varying times and the reaction is stopped using SDS. N- and C-terminal fragments derived from vanadate/βBP-quenched reactions and LysC treatments are resolved on SDS-PAGE. C) Dephosphorylation kinetics. The SDS-quenched time samples were fit to rate constants of 0.14 ± 0.003 min−1 for clASF(214) (□) and 0.15 ± 0.005 min−1 for cl-RATA(214) (△). For cl-RS-RRM2(214) (▲), double exponential fitting provides rate constants of 1.0 ± 0.29 and 0.12 ± 0.06 min−1 and amplitudes of 4.6 ± 2.7 and 5.4 ± 2.7 sites. For cl-ΔRRM1(214) (●), double exponential fitting provides rate constants of >10 and 0.14 ± 0.017 min−1 and amplitudes of 1.1 ± 0.29 and 8.9 ± 0.29 sites. D) C/N Plot. The ratios of C- and N-terminal fragments resulting from LysC treatment and determined by autoradiography for cl-ΔRRM1(214) (●), cl-RS-RRM2(214) (▲) and cl-RATA(214) (△) are plotted as a function of sites dephosphorylated. The dotted line shows the data for clASF(214) from Fig. 2D. E) Time-dependent changes in N- (●) and C-terminal (▲) fragments for cl-ΔRRM1(214). The disappearance of the N-terminal fragment was fit to a double exponential function with rate constants of 6 ± 3 and 0.17 ± 0.05 min−1 and amplitudes of 1.1 ± 0.32 and 8.9 ± 0.32 sites. The disappearance of the C-terminal fragment was fit to a single exponential function with rate constant of 0.11 ± 0.017 min−1 and an amplitude of 5.0 ± 0.14 sites. F) Time-dependent changes in N- (●) and C-terminal (▲) fragments for cl-RS-RRM2(214). The disappearance of the N-terminal fragment was fit to a double exponential function with rate constants of 3.2 ± 0.63 and 0.14 ± 0.010 min−1 and amplitudes of 1.0 ± 0.090 and 4.2 ± 0.09 sites. The disappearance of the C-terminal fragment was fit to a double exponential function with rate constants of 1.0 ± 0.30 and 0.24 ± 0.19 min−1 and amplitudes of 2.5 ± 1.0 and 2.3 ± 0.80 sites.

Directional Dephosphorylation of RS1 Is Not Dependent on PP1 Docking Elements

Since removal of the N-terminal RRMs affected the dephosphorylation mechanism for RS1, we investigated whether contacts between PP1 and the RRMs could be the source of this mechanism shift. Previous studies indicate that PP1 recognizes a related sequence (RVDF) in the single RRM of Tra2β, an SR-like protein.23 Mutation of this motif to RATA was shown to disrupt interactions of Tra2β with PP1 in pull down assays. Since ASF/SF2 possesses a related docking motif in RRM1 (RVEF), we wished to test whether this sequence could potentially guide directional dephosphorylation. Given this precedence, we made the RATA mutations in the clASF(214) construct (Fig. 5A). This new construct, clASF(RATA), is dephosphorylated by PP1 at the same rate constant as clASF(214) suggesting that any potential docking to RRM1 does not affect PP1 activity towards the RS domain (Fig. 5C). We were not able to measure accurately whether the docking mutations weakened binding to PP1 since the Km is, at least, as high as that for clASF(214) (Km = 1 μM; Fig. 1B) and we cannot go above 1 μM phospho-substrate owing to limited solubility. Nonetheless, we found that mutations in the docking sequence had no affect on the directional mechanism in RS1 as the C/N ratio of the LysC fragments was found to increase in a manner similar to that for clASF(214) as a function of PP1 dephosphorylation (Fig. 5D). These data show that sequences in RRM1 thought to interact with PP1 do not regulate the directional dephosphorylation mechanism.

Sequestering Effects of the RRMs on RS Domain Dephosphorylation

To better define how the RRMs control PP1 activity, we measured the dephosphorylation of a substrate form lacking both RRMs [cl-RS(214)] (Fig.6A). The R214K mutation in this construct was maintained for direct comparison to the other cleavage constructs. We found that SRPK1-phosphorylated cl-RS(214) was dephosphorylated about 12-fold faster than clASF(214) (Fig. 6B). However, while 8 phosphates are highly sensitive, the last 2 phosphates are more resistant to dephosphorylation by PP1 and are removed at the same, slow rate constant as that for clASF(214). These data suggest that the RRMs might interact with the phosphorylated RS domain, thereby, protecting against PP1. If this is so, we should be able to sequester the phosphorylated RS domain using additional RRMs and reduce dephosphorylation rates. To test this, we dephosphorylated SRPK1-phosphorylated clASF(214) using PP1 in the absence and presence of four RRM constructs (Fig. 6A). We found that His- and GST-tagged forms of ASF/SF2 lacking the RS domain [ASF(ΔRS) & GST-ASF(ΔRS)] significantly impeded the dephosphorylation of the RS1 segment in clASF(214) (Fig. 6C). This effect is mostly due to a large decrease in the amplitude of the first phase. Interestingly, both RRMs are required for this protective phenomenon as the separate RRMs did not have the same effect. To demonstrate that these inhibitory effects are due to RS-RRM interactions and not to RRM-RRM interactions between clASF(214) and ASF(ΔRS), we performed dephosphorylation experiments using cl-RS(214) (Fig. 6D). We found that ASF(ΔRS) and GST-ASF(ΔRS) inhibited dephosphorylation in a similar manner as that for clASF(214). These findings indicate that the RRM1–RRM2 pair is likely to interact with the RS domain and protect some of the phosphates from removal by PP1.

Figure 6. Effects of Additional RRMs on RS Domain Dephosphorylation.

A) ASF/SF2 constructs. B) Dephosphorylation kinetics of cl-RS(214) (◯) and clASF(214) (●). Reactions using 250 nM PP1 are quenched using SDS and fit to double exponential functions with rate constants and amplitudes of 0.32 ± 0.08 and 0.044 ± 0.032 min−1 and 7.8 ± 1.7 and 2.2 ± 1.7 sites for clASF(214) and rate constants and amplitudes of 3.7 ± 0.32 and 0.043 ± 0.010 min−1 and 7.4 ± 0.20 and 2.6 ± 0.20 sites for cl-RS(214). C–D) Dephosphorylation kinetics of clASF(214) (C) and cl-RS(214) (D) in the absence (●) and presence of 1 μM RRM1 (▲), RRM2 (△), ASF(ΔRS) (□) and GST- ASF(ΔRS) (◯). For reactions with clASF(214), 250 nM PP1 was used while for reactions with cl-RS(214), 125 nM PP1 was used. For clASF(214), data are fit to double exponential functions with rate constants and amplitudes of 0.30 ± 0.10 and 0.022 ± 0.029 min−1 and 8.4 ± 1.2 and 1.6 ± 1.2 sites with no RRMs, rate constants and amplitudes of 0.20 ± 0.016 and 0.031 ± 0.011 min−1 and 8.0 ± 1.0 and 2.0 ± 1.0 sites in the presence of RRM1, rate constants and amplitudes of 0.42 ± 0.13 and 0.030 ± 0.019 min−1 and 7.7 ± 1.4 and 2.3 ± 1.4 sites in the presence of RRM2, rate constants and amplitudes of 0.29 ± 0.11 and 0.016 ± 0.0084 min−1 and 4.1 ± 1.0 and 5.9 ± 1.0 sites in the presence of ASF(ΔRS) and, rate constants and amplitudes of 0.20 ± 0.027 and 0.013 ± 0.0058 min−1 and 5.6 ± 0.90 and 4.4 ± 0.90 sites in the presence of GST-ASF(ΔRS). For cl-RS(214), data are fit to double exponential functions with rate constants and amplitudes of 2.1 ± 0.15 and 0.043 ± 0.0053 min−1 and 6.5 ± 0.11 and 3.6 ± 0.11 sites with no RRMs, rate constants and amplitudes of 1.0 ± 0.17 and 0.030 ± 0.025 min−1 and 6.5 ± 0.72 and 3.5 ± 0.72 sites in the presence of RRM1, rate constants and amplitudes of 1.4 ± 0.15 and 0.045 ± 0.015 min−1 and 6.2 ± 0.37 and 3.8 ± 0.37 sites in the presence of RRM2, rate constants and amplitudes of 1.5 ± 0.29 and 0.069 ± 0.011 min−1 and 3.6 ± 0.43 and 6.4 ± 0.43 sites in the presence of ASF(ΔRS) and, rate constants and amplitudes of 1.1 ± 0.30 and 0.058 ± 0.018 min−1 and 4.2 ± 0.71 and 5.8 ± 0.72 sites in the presence of GST-ASF(ΔRS).

Binding of the Ron ESE Sequence Inhibits ASF/SF2 Dephosphorylation

ASF/SF2 regulates the splicing of the Ron proto-oncogene by binding to the ESE sequence AGGCGGAGGAAGC.24 To determine whether interaction with the Ron ESE impacts the structure of ASF/SF2 and affects phosphate removal, we investigated the dephosphorylation of clASF(214) in the presence of this sequence. We found that PP1-catalyzed dephosphorylation of SRPK1-phosphorylated clASF(214) is inhibited by Ron ESE (Fig. 7A). The inhibition is the result of a sizable decrease in the amplitude of the initial, fast phase and an extension of the second slow phase from about 1 to almost 9 sites. To address whether this inhibitory phenomenon is largely the result of RNA binding to the RRMs or direct interactions with the RS domain, we investigated the dephosphorylation of a construct lacking both RRM1 and RRM2 [cl-RS(214)]. Since this RS domain is rapidly dephosphorylated (Fig. 6B), we used a 4-fold lower amount of PP1 for these experiments. Overall, the Ron ESE had no significant effect on dephosphorylation rate constants or amplitudes for cl-RS(214) (Fig. 7B) suggesting that the inhibitory effects are not the result of specific RNA-RS interactions or due to potential contacts between PP1 and the RNA.

Figure 7. Effects of Ron ESE Binding on RS Domain Dephosphorylation.

(A–B) Dephosphorylation kinetics of clASF(214) (A) and cl-RS(214) (B) in the absence (●) and presence (◯) of 1 μM Ron ESE. For clASF(214), the data are fit to double exponential functions with rate constants and amplitudes of 0.19 ± 0.014 and 0.050 ± 0.028 min−1 and 8.9 ± 0.20 and 1.1 ± 0.20 sites in the absence of Ron ESE and rate constants and amplitudes of 0.36 ± 0.16 and 0.036 ± 0.020 min−1 and 1.0 ± 0.29 and 8.9 ± 0.17 sites in the presence of Ron ESE. For cl-RS(214), the data are fit to double exponential functions with rate constants and amplitudes of 1.5 ± 0.45 and 0.035 ± 0.022 min−1 and 3.8 ± 0.70 and 6.2 ± 0.70 sites in the absence of Ron ESE and rate constants and amplitudes of 0.65 ± 0.13 and 0.017 ± 0.011 min−1 and 3.8 ± 0.32 and 6.2 ± 0.32 sites in the presence of Ron ESE. PP1 concentrations of 250 nM were used for clASF(214) whereas 60 nM was used for cl-RS(214). (C–D) Time-dependent change in N- (C) and C-terminal fragments (D) for clASF(214) in the absence (●) and presence (◯) of 1 μM Ron ESE. Samples from (A), quenched in vanadate/βGP, are treated with LysC, separated on SDS-PAGE and the relative counts are used to establish the time-dependent changes in the N- and C-terminal fragments. For the N-terminal fragments in panel (C) the data are fit to a single exponential function with a rate constant and amplitude of 0.37 ± 0.037 min−1 and 4.3 ± 0.18 sites in the absence of RNA and with a double exponential function with rate constants and amplitudes of 3.1 ± 1.4 and 0.050 ± 0.0043 min−1 and 1.3 ± 0.14 and 3.0 ± 0.10 sites, respectively, in the presence of RNA. For the C-terminal fragments in panel (D), the data are fit to equation (1) to obtain values of 0.34 ± 0.070 and 0.20 ± 0.030 min−1 for kL and k1 in the absence of RNA and values of 0.040 ± 0.0089 and 0.32 ± 0.068 min−1 for kL and k1 in the presence of RNA.

To better understand how RNA inhibits dephosphorylation of the full-length protein, the N- and C-terminal fragments of clASF(214) were analyzed as a function of PP1 dephosphorylation in the absence and presence of Ron ESE. While RNA does not affect the dephosphorylation of the first phosphate from the N-terminal fragment, the remaining three phosphates in this fragment are slowly removed (Fig. 7C). Thus, while all 4 phosphates in the N-terminal fragment are quickly removed by PP1 in the absence of RNA, only one is quickly removed in the presence of RNA. Also, RNA binding greatly slows the dephosphorylation of the C-terminal fragment by reducing the rate of the lag phase (kL) by about 8-fold without significantly affecting the subsequent dephosphorylation step (k1) (Fig. 7D). This protracted lag period is likely the result of the slower removal of N-terminal phosphates which function as a linchpin for the removal of the C-terminal phosphates, a finding consistent with the sequential, coupled nature of the RS1 dephosphorylation reaction (Figs. 2–4). Overall, these findings suggest that RNA binding to the RRMs inhibits ASF/SF2 dephosphorylation by inducing a conformation change in the SR protein that protects a larger portion of RS1.

Clk/Sty Randomly Phosphorylates the RS Domain of ASF/SF2

In previous studies we showed that SRPK1 strongly favors phosphorylation of RS1 in ASF/SF2.21 To understand how RS2 is phosphorylated and then probe how this might impact RS1 dephosphorylation, we first investigated the regiospecific phosphorylation of two cleavage constructs- clASF(224) & clASF(214)- by Clk/Sty, an enzyme capable of phosphorylating both RS1 and RS2 (Fig. 8A). By adjusting the total concentration of ATP and letting the reaction proceed to completion (30 min) in ATP limitation experiments, the total phosphoryl content of clASF(224) in the presence of Clk/Sty can be accurately controlled (Fig. 8B). In kinetic progress curves where the total ATP is not limiting and kept constant (100 μM), Clk/Sty readily phosphorylates the RS domain of clASF(224) in several minutes (Fig. 8D). Previous studies showed that while SRPK1 mostly phosphorylates RS1 (10–12 serines), Clk/Sty can modify the full RS domain (18–20 serines).19 Using either ATP limitation or kinetic progress curves, we were able to generate N- and C-terminal halves of clASF(224) using LysC that reflect approximately the RS1 and RS2 segments of the RS domain and then plot the ratios of these fragments as a function of reaction progress (Fig. 8C, E). In both cases, Clk/Sty readily adds phosphates to both RS1 and RS2 with similar efficiency (i.e.- N/C ratios are close to 1 at the lowest phosphoryl contents). For both the ATP limitation and kinetic assays, the final N/C ratios are about 2 at the highest phosphoryl content consistent with the available number of serines for phosphorylation in both N- and C-terminal fragments of clASF(224) (Fig. 8A,C,E). Unlike Clk/Sty, we showed previously that SRPK1 has a strong preference for modifying the N-terminal half of clASF(224) (dotted line, Fig. 8C). The overall data indicate that Clk/Sty shows no regiospecific preference for phosphorylating RS1 or RS2 in the RS domain of ASF/SF2.

Figure 8. Regiospecificity of ASF/SF2 Phosphorylation by Clk/Sty.

A) clASF(214) & clASF(224) cleavage constructs. B) ATP limitation assay for the phosphorylation of clASF(224) by Clk/Sty. C) N/C Ratio for clASF(224) as a function of Clk/Sty phosphorylation by ATP limitation. Dotted line represents the N/C ratio for clASF(224) using SRPK1 taken from Ma et. al.21 D) Single turnover phosphorylation of clASF(224) by Clk/Sty. The data were fit to a single exponential function with a rate constant 1 ± 0.1 min−1. E) N/C ratio for clASF(224) as a function of phosphoryl content derived from the time-dependent assay. F) ATP limitation assay for the phosphorylation of clASF(214) by Clk/Sty. G) N/C Ratio for clASF(214) as a function of Clk/Sty phosphorylation by ATP limitation. Dotted line represents the N/C ratio for clASF(214) using SRPK1 taken from Hagopian et. al.20

Although the above cleavage experiments suggest that Clk/Sty is not regiospecific for RS1 or RS2, we wished to determine whether this kinase performs directional phosphorylation within the RS1 segment of ASF/SF2. To investigate this possibility, we studied the phosphorylation specificity of clASF(214) which contains a single cleavage site in the middle of the RS1 segment of the RS domain. In ATP limitation experiments, the phosphoryl content of the RS domain of clASF(214) could be carefully controlled as a function of total ATP concentration (Fig. 8F). By inserting a LysC step we were able to show that the N/C ratio does not change as a function of reaction progress (Fig. 8G). The slight preference for C-terminal modification at low phosphoryl content (N/C ratio = 0.4) may reflect the relative distribution of serines in both fragments (6 in N, 13 in C) and, thus, may not signify a true specificity for either segment. At high phosphoryl content, the experimental N/C ratio is consistent with the theoretical number of phosphorylatable serines available in both fragments. These findings starkly compare with the N/C plot for clASF(214) published previously (dotted line; Fig. 8G) where SRPK1 prefers initial C-terminal phosphorylation (i.e.- the C-terminal half of RS1) by about 100-fold.17; 20 Clk/Sty is capable of phosphorylating RS1 and RS2 with similar efficiencies, but, unlike SRPK1, the absence of any variance in N/C ratio as a function of phosphorylation suggests that Clk/Sty does not display any directional phosphorylation within the RS1 segment. Thus, Clk/Sty appears to phosphorylate all serines in the RS domain of ASF/SF2 using a mechanism that lacks both regiospecificity and directionality.

Clk/Sty Phosphorylation of RS2 Alters RS1 Dephosphorylation

Since Clk/Sty can phosphorylate the entire RS domain, the potential role of RS2 phosphorylation in controlling RS1 dephosphorylation by PP1 can be assessed. To accomplish this goal, we monitored the regiospecific dephosphorylation of the two cleavage vectors clASF(224) and clASF(214), pre-phosphorylated by Clk/Sty. We found that, unlike the SRPK1 reaction that can use limiting ATP, high 32P- ATP concentrations were required to phosphorylate completely these cleavage vectors using Clk/Sty. Since the dephosphorylation of Clk/Sty-phosphorylated cleavage substrates was slow and incomplete under these conditions owing to re-phosphorylation in the presence of excess ATP (data not shown), we treated the reaction with a Clk/Sty-specific inhibitor (TG003) before the addition of PP1. We showed in control assays that TG003 fully inhibited Clk/Sty beyond the time-frame of the PP1 reaction (Fig. 9C). Under these conditions, we obtained efficient and quantitative dephosphorylation of both substrates (Fig. 9C). To determine whether PP1 shows RS1 or RS2 preferences, Clk/Sty-phosphorylated clASF(224) was treated with LysC at various stages of dephosphorylation to generate fragments approximating these segments (Fig. 9A). We found that the N/C ratio for clASF(224) did not vary as a function of dephosphorylation (Fig. 9D). Phosphates from both N- and C-terminal portions of the RS domain were removed at approximately the same rate (Fig. 9E), indicating that PP1 displays no dominant preference for RS1 or RS2. To determine whether RS2 modifications could affect the mechanism of RS1 dephosphorylation, we evaluated the dephosphorylation of clASF(214). Likewise, we found that there was no preference for dephosphorylating the N- and C-terminal portions of the RS domain (Fig. 9B,D,E). If PP1 showed some directionality in RS1 we would anticipate a significant change in the N/C ratio and the amount of N- and C-terminal fragments as a function of dephosphorylation time. These studies indicate that RS2 phosphorylation disrupts the directional dephosphorylation mechanism in RS2.

Figure 9. PP1 Randomly Dephosphorylates the RS domain of ASF/SF2.

Time-dependent dephosphorylation of Clk/Sty-phosphorylated clASF(224) (A) and clASF(214) (B). Both constructs are reacted with PP1 for varying times and the reactions are stopped using SDS. N- and C-terminal fragments derived from vanadate/βGP-quenched reactions and LysC treatments are resolved on SDS-PAGE. C) Dephosphorylation kinetics. The SDS-quenched time samples for clASF(224) (●) were fit to a rate constant of 0.054 ± 0.0072 min−1 and an amplitude of 20 ± 1.2 sites. The data for clASF(214) (◯) observed a similar time-dependent decrease. The phosphorylation of clASF(214) (100 nM) by Clk/Sty (20 nM) was also monitored in the presence of 100 μM TG003 (△). D) N/C Plot. The ratios of C- and N-terminal fragments resulting from LysC treatment and determined by autoradiography for clASF(224) (●) and clASF(214) (◯) are plotted as a function of sites dephosphorylated. E) Time-dependent changes in N- and C-terminal fragments for clASF(224) and clASF(214). The data for cl-ASF(224) are fit to single exponential functions to attain rate constants and amplitudes of 0.063 ± 0.0066 min−1 and 10 ± 0.48 sites for the N-terminal fragment (◯) and 0.047 ± 0.010 min−1 and 10 ± 0.86 sites for the C-terminal fragment (●). The data for clASF(214) are fit to single exponential functions to attain rate constants and amplitudes of 0.035 ± 0.0056 min−1 and 5.8 ± 0.35 sites for the N-terminal fragment (△) and 0.055 ± 0.0060 min−1 and 14 ± 0.58 sites for the C-terminal fragment (▲). F) Dephosphorylation kinetics for N-clASF(214) (●) and N-clASF(ΔRS2) (◯). The data for N-clASF(214) are fit to a double exponential function to attain rate constants of 0.10 ± 0.01 and 0.040 ± 0.012 min−1 and amplitudes of 7.5 ± 0.50 and 2.5 ± 0.50 sites. The data for N-clASF(ΔRS2) are fit to a double exponential function to attain rate constants of 0.16 ± 0.034 and 0.010 ± 0.005 min−1 and amplitudes of 8.4 ± 1.2 and 1.6 ± 1.2 sites.

In addition to effects on PP1 directionality, RS2 phosphorylation appears to alter the dephosphorylation rate of N-terminal serines in RS1. By comparing substrates pre-phosphorylated by SRPK1 and Clk/Sty, we found that the N-terminal fragment in clASF(214), which encompasses the N-terminal region of RS1, is dephosphorylated about 8-fold slower when RS2 is initially phosphorylated (0.27 vs. 0.035 min−1; Figs 2E & Figs. 9E). To address whether this result is purely phosphorylation-dependent, we studied a truncated form of ASF/SF2 lacking RS2 residues (228–248). Since we did not want the C-terminal His tag to potentially replace RS2 and interfere with PP1, the new truncation mutant [N-clASF(ΔRS2)] was made from an N-terminal His-tagged cleavage vector, N-clASF(214), which retained the mutations in RRM2 and the RS domain from clASF(214). This new construct, pre-phosphorylated by SRPK1, was dephosphorylated at a similar rate constant as N-clASF(214) (Fig. 9F) suggesting that the RS2 segment does not impact the ability of PP1 to removes phosphates from RS1. Also, the rates and amplitudes for N-clASF(214) are similar to those for clASF(214) (Fig. 2) indicating that moving the His tag from the C- to the N-terminal position did not affect PP1 activity. Since treatment of N-clASF(ΔRS2) with LysC does not generate an observable C-terminal fragment on SDS-PAGE, most likely owing to its small size (13 aa), we could not address any possible role of RS2 in controlling directional dephosphorylation. Nonetheless, a comparison of the dephosphorylation of N-clASF(ΔRS2) and N-clASF(214) indicates that the RS2 segment does not affect the rate of RS1 dephosphorylation by PP1. These findings suggest that the inhibitory effects of Clk/Sty phosphorylation of RS2 on RS1 dephosphorylation are solely the result of modifications in RS2 and not to the RS2 segment itself.

Discussion

Although SRPK1 and PP1 control phosphate balance in SR proteins, they use very distinctive strategies for engaging the RS domain of ASF/SF2. SRPK1 forms a high affinity complex with ASF/SF2, quickly phosphorylating 10 serines in the RS1 portion of the RS domain, whereas PP1 binds with lower affinity and removes these phosphates with considerably less efficiency (Fig 1). We showed that this phenomenon is partly due to the protective effects of the N-terminal RRMs on the RS1 dephosphorylation reaction as opposed to the phosphorylation reaction. While removal of the RRMs in ASF/SF2 enhances PP1 activity toward the RS domain by about an order of magnitude (Fig. 6B), removal of these domains does not enhance SRPK1 phosphorylation activity.25 Crystallographic and deletion analyses show that the sufficiency of the RS domain for SRPK1 phosphorylation is due to a well-contoured, extensive binding pocket that tightly recognizes the RS1 segment.21; 22 Thus, while SRPK1 accommodates multiple Arg-Ser repeats and phosphorylates in a C-to-N direction owing to a lengthy binding channel, PP1 which lacks such a channel26 relies on the conformation of the SR protein and the differential accessibility of the N- and C-terminal ends of RS1. In this model (Fig. 10), the C-terminal sequences in RS1 are poorly accessible due to contacts with the RRMs so that dephosphorylation initially begins at the more exposed N-terminal end. This model is supported by three independent observations. First, time-dependent mapping data define a sequential and coupled removal of phosphates starting at the N-terminus (Figs. 2–4). Second, the amplitude of the slow dephosphorylation phase of the RS domain is greatly increased by the addition of the truncated RRM1–RRM2 protein, consistent with C-terminal protection of RS1 by these domains (Fig. 6D). Third, removal of putative docking sequences in RRM1 does not impact the directionality of dephosphorylation suggesting that differential exposure of RS1 rather than enzyme-substrate geometry is the cause of directional dephosphorylation (Fig. 4). Overall, the data suggest that conformational factors in the full-length SR protein control the efficiency and order of phosphate removal by PP1 whereas local sequence determinants in the RS domain direct phosphorylation by SRPK1.

Figure 10. Model for Directionality Control of ASF/SF2 Dephosphorylation by PP1.

RRM1-bound PP1 initially dephosphorylates N-terminal phosphates in RS1 owing to greater exposure. The binding of RNA to the RRMs (lower left) further buries C-terminal phosphates in RS1 whereas RS2 phosphorylation by Clk/Sty (lower right) causes larger conformational changes that equivalently expose phosphates in the RS domain.

While the RRMs impose a constitutive layer of control over ASF/SF2 dephosphorylation, reversible factors also appear to regulate the phosphoryl content of the SR protein. One of these regulatory modes operates through an RNA-induced change in RRM-RS1 interactions. We showed that the binding of the Ron ESE to the RRMs selectively down-regulates the dephosphorylation of ASF/SF2 (Fig. 7). This phenomenon most likely occurs by RNA-dependent changes in ASF/SF2 conformation that further protects RS1 without altering the N-to-C directionality of PP1. This effect could be due to sliding of the RS1 segment along the RRM1–RRM2 pair (Fig. 10), a phenomenon that protects phosphates in the N-terminal portion of the segment and prolongs the removal of phosphates in the C-terminal regions (Fig. 7C&D). The net result of ESE engagement then is an increase in the overall lifetime of phosphates on RS1. Furthermore, we found that phosphorylation of the RS2 segment by the nuclear protein kinase Clk/Sty also had an inhibitory effect on RS1. While RNA binding did not alter the N-to-C preference of PP1, RS2 phosphorylation abrogated the directional mechanism suggesting that Clk/Sty initiates further conformational changes in ASF/SF2 beyond those induced by RRM engagement. Overall, while RNA binding and RS2 phosphorylation serve to reduce the rate of RS1 dephosphorylation, the mechanisms underlying these phenomena appear very distinctive and likely hint to considerable differences in the conformation of SRPK1- and Clk/Sty-phosphorylated ASF/SF2 (Fig.10).

Converging studies now support a vital role for SRPK and CLK family kinases in controlling the cytoplasmic-nuclear distribution and splicing function of SR proteins through regiospecific phosphorylation.8; 9; 27; 28; 29; 30 Despite these insights, the phosphorylation status of SR proteins in the cell and its impact on conformation are still poorly understood. In the present study we used PP1 as a probe for understanding how sequences flanking the RS1 segment control SR protein structure. Indeed, the ability to fine-tune this structure through both phosphorylation (by Clk/Sty) and RNA binding hints to a potential regulatory mechanism. As both SR protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are essential for splicing, the inhibitory effects of Ron ESE binding or Clk/Sty phosphorylation may provide a means for increasing the lifetimes of some RS domain phosphates for splice-site selection. For example, the inhibitory effects may permit adequate time for initial splice-site selection, a process known to be strengthened by RS domain phosphorylation,2; 3 before PP1 removes these phosphates, a process known to facilitate splicesome maturation.31; 32 These inhibitory effects can lengthen the gap between SR protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation and potentially help regulate splicing reactions. Furthermore, the opposing directional activities of SRPK1 and PP1 along with modulation through reversible mechanisms (RNA, Clk/Sty) could concentrate phosphates into specific areas of the RS domain that may adjust specific interactions in the spliceosome. Under conditions where the working activities of SRPK1 and PP1 are more closely matched, phosphates would be expected to concentrate toward the C-terminal end of RS1 leaving the N-terminal end disproportionately unphosphorylated. Engagement of ASF/SF2 with an ESE or up-regulation of Clk/Sty in the nucleus could slow PP1 action and shift the phosphate distribution toward more N-terminal serines.

Materials & Methods

Materials

Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C (LysC), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulphonic acid (Mops), Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), imidazole, sodium vanadate, β-glycerolphosphate (βGP), Tween 20, MgCl2, NaCl, EDTA, EGTA, glycerol, acetic acid, Kodak imaging film (Biomax MR), TFA, BSA, acetonitrile, and liquid scintillant were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Clk-specific inhibitor TG003 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Instant Blue stain was obtained from Expedeon Protein Solutions. [γ-32P] ATP was obtained from NEN Products, a division of Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

Constructs with alternative cleavage sites were generated by single or sequential polymerase chain reactions using the QuikChange™ mutagenesis kit and relevant primers, described in previous publications.17 N-terminal deletion constructs were generated by PCR amplification and sub-cloning into pET28a, and the domain swap mutant cl-RS-RRM2(214) was generated by sequential sub-cloning into pET15b, both described in a previous publication.21 GST-tagged cleavage vector was generated by PCR amplification and sub-cloning into pGEX4T2. His-tagged protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit gamma isoform (PP1) was a gift from Dr. Anna DePaoli-Roach.33 The plasmid for PP1 was transformed into the BL21 (DE3) E. coli strain and the cells were then grown at 37°C in LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 0.5 mM MnCl2. When OD reached 0.35, protein expression was induced with 0.25 mM IPTG at room temperature overnight. Cells were lysed by sonication in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylfulonyl fluoride, and 15% glycerol. The soluble fraction was loaded onto a Ni2+-Sepharose column, with addition of 5 mM imidazole and 60 mM NaCl. The column was washed thoroughly with the same buffer containing 20 mM imidazole, and eluted with increasing amount of imidazole (60, 120, and finally 200 mM). The eluted protein was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 60 mM NaCl, 2 mM MnCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol, concentrated to less than 5 ml with Amicon 30-kDA MWCO spin columns, and stored at −80 °C. All His-tagged ASF/SF2 constructs were refolded and purified using a published protocol.17 GST-tagged ASF/SF2 cleavage construct was purified by glutathione-resin affinity chromatography using a published procedure.25 SRPK1 and Clk/Sty were purified by Ni-resin affinity chromatography using a published procedure.18; 19

Generation of Phosphorylated ASF/SF2

Generation of all phosphorylated ASF/SF2 constructs for dephosphorylation by PP1 was conducted in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 0.025% Tween 20, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MnCl2, and 100 mM NaCl. To generate RS1-phosphorylated cleavage substrates (10 sites) using SRPK1 for proteolytic studies, a 5:1 ratio of ASF/SF2 (100 nM) to SRPK1 (20 nM) was allowed to react for 1.5–2 hrs in the presence of 2 or 16 μM 32P-ATP. To generate partially (5 sites) and fully phosphorylated RS1 (10 sites), equal amounts (500 nM) of SRPK1 and clASF(214) were reacted with 3 and 6 μM ATP. For steady-state kinetic studies of dephosphorylation, a 10:1 ratio of wt-ASF/SF2 and SRPK1 was reacted with 16 μM 32P-ATP for 1.5–2 hrs and then diluted in the presence of PP1 to achieve varying initial concentrations of p-ASF/SF2. To generate both RS1- and RS2-phosphorylated cleavage substrates (20 sites) for proteolytic studies, a 5:1 ratio of ASF/SF2 (100 nM) and Clk/Sty (20 nM) was allowed to react for 2 hrs in the presence of 100 μM 32P-ATP. The extent and regiospecificity of phosphorylation in both RS1 and RS2 was confirmed by autoradiographic analyses of full-length and LysC-digested proteins.

Dephosphorylation Reactions & LysC Proteolysis

Dephosphorylation of pre-phosphorylated substrates was then initiated with the addition of 250 nM PP1 [1 μM PP1 for clGST-ASF(214)] at 37 °C in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 0.025% Tween 20, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MnCl2, and 100 mM NaCl. In RNA and RRM binding experiments, ASF(ΔRS) or Ron RNA was incubated with pre-phosphorylated ASF/SF2 for 5 minutes before initiation of the dephosphorylation reaction using PP1. Since a large excess of 32P-ATP was needed to prephosphorylate substrates using Clk/Sty as opposed to SRPK1 where a limiting amount was used, 100 μM of a Clk-specific inhibitor (TG003) was added to terminate any additional kinase activity. To monitor the dephosphorylation of the full-length substrates, the reactions were stopped at various incubation times using an equal volume of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. For LysC protease footprinting experiments, the quench buffer contained 33 mM sodium vanadate, 20 mM β-glycerolphosphate [βGP] and 2 mM EDTA in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.5). Proteolysis with LysC (100 ng) was then carried out for 3 hours at 37 °C, or overnight for certain Clk-phosphorylated substrates. The fragments were then separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and the dried gels were exposed with Kodak imaging film (Biomax MR). The protein bands corresponding to phosphorylated ASF/SF2 were excised and counted on the 32P channel in liquid scintillant. Control experiments, specific activity determination and time-dependent product concentrations were determined as previously described.18

Regiospecific Clk/Sty Phosphorylation Studies

The phosphorylation of ASF/SF2 constructs by Clk/Sty was carried out in a buffer containing 50 mM Mops (pH 7.4), 10 mM free Mg2+, and [γ-32P]ATP (1000 cpm pmol−1) at 23 °C. Reactions were typically initiated with the addition of 32PATP (100 mM) in a total reaction volume of 10 mL and then were quenched with 10 μL SDS-PAGE loading buffer. For protease footprinting of samples phosphorylated using limiting ATP (ATP limitation experiments), 1 μM enzyme was pre-equilibrated with 0.2 μM ASF/SF2, and 0.2 to 100 μM [γ-32P]ATP was added to initiate a 20-minute reaction. After this period, the reaction was then cold-chased with 4 mM ATP for, at least, 30 minutes, and proteolyzed with LysC (100 ng) overnight at 37 °C. For kinetic protease footprinting (pulse-chase experiments), reactions were initiated with [32P]ATP (100 μM) and then were cold-chased at various time points up to 30 minutes with 4 mM ATP. Proteolysis with LysC (100 ng) was then carried out overnight at 37 °C.

GST-Pull Down Assay

For PP1 pull-down experiments, GST-ASF/SF2 (20 μM) was incubated with His-PP1 (2.5 μM) for 30 minutes in the binding buffer (0.1% NP40, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl) at 4 °C. For SRPK1 pull-down experiments, GST-ASF/SF2 (10 μM) was incubated with His-SRPK1 (2.5 μM) for 30 minutes in the binding buffer (0.1% NP40, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl) at 4 °C in the absence and presence of ATP. The mixtures were then incubated with 15 μl glutathione modified agarose resin for 30 minutes at 4 °C. The resin was washed 3 times with 500 μl binding buffer and the bound proteins were eluted by treating with SDS quench buffer for 5 minutes at 90°C. Bound protein was resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized by Instant Blue Coomasie stain.

Data Analyses

All initial velocity data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain values for Vmax and Km. The total SRPK1 and PP1 concentrations were used to convert Vmax to kcat. Progress curve data for ASF/SF2 phosphorylation and dephosphorylation were plotted as ratios of incorporated phosphate and the total substrate concentration (# of sites) as a function of time. The plots of phosphoryl content as a function of dephosphorylation by PP1 were fit to either single or double exponential functions. The time-dependent disappearance of the C-terminal fragments for clASF(214) and GST-ASF(214) generated by LysC cleavage were fit to equation (1):

| (1) |

where C is the number of sites phosphorylated in the C-terminus at any time t, Co is the initial number prior to phosphatase treatment, and kL and k1 are the rate constants controlling the disappearance of the C-terminal fragment. This equation adapted from Gutfreund34 describes a sequential, two-step mechanism where kL is the first step and is noncatalytic and k1 is the second step and represents dephosphorylation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jurica MS, Moore MJ. Pre-mRNA splicing: awash in a sea of proteins. Mol Cell. 2003;12:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohtz JD, Jamison SF, Will CL, Zuo P, Luhrmann R, Garcia-Blanco MA, Manley JL. Protein-protein interactions and 5'-splice-site recognition in mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature. 1994;368:119–24. doi: 10.1038/368119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JY, Maniatis T. Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell. 1993;75:1061–70. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90316-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roscigno RF, Garcia-Blanco MA. SR proteins escort the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP to the spliceosome. Rna. 1995;1:692–706. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chew SL, Liu HX, Mayeda A, Krainer AR. Evidence for the function of an exonic splicing enhancer after the first catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10655–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stojdl DF, Bell JC. SR protein kinases: the splice of life. Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;77:293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blencowe BJ. Exonic splicing enhancers: mechanism of action, diversity and role in human genetic diseases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:106–10. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngo JC, Chakrabarti S, Ding JH, Velazquez-Dones A, Nolen B, Aubol BE, Adams JA, Fu XD, Ghosh G. Interplay between SRPK and Clk/Sty Kinases in Phosphorylation of the Splicing Factor ASF/SF2 Is Regulated by a Docking Motif in ASF/SF2. Mol Cell. 2005;20:77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koizumi J, Okamoto Y, Onogi H, Mayeda A, Krainer AR, Hagiwara M. The subcellular localization of SF2/ASF is regulated by direct interaction with SR protein kinases (SRPKs) J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11125–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad J, Colwill K, Pawson T, Manley JL. The protein kinase Clk/Sty directly modulates SR protein activity: both hyper- and hypophosphorylation inhibit splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6991–7000. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patwardhan P, Shen Y, Goldberg GS, Miller WT. Individual Cas phosphorylation sites are dispensable for processive phosphorylation by Src and anchorage-independent cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20689–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602311200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeffery DA, Springer M, King DS, O'Shea EK. Multi-site phosphorylation of Pho4 by the cyclin-CDK Pho80-Pho85 is semi-processive with site preference. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:997–1010. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrell JE, Jr., Bhatt RR. Mechanistic studies of the dual phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19008–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.19008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins DJ, Cobb MH. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 2 autophosphorylates on a subset of peptides phosphorylated in intact cells in response to insulin and nerve growth factor: analysis by peptide mapping. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:299–308. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haystead TA, Dent P, Wu J, Haystead CM, Sturgill TW. Ordered phosphorylation of p42mapk by MAP kinase kinase. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:17–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80828-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, Zhang ZY. The mechanism of dephosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 by mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32382–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma CT, Velazquez-Dones A, Hagopian JC, Ghosh G, Fu XD, Adams JA. Ordered multi-site phosphorylation of the splicing factor ASF/SF2 by SRPK1. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aubol BE, Chakrabarti S, Ngo J, Shaffer J, Nolen B, Fu XD, Ghosh G, Adams JA. Processive phosphorylation of alternative splicing factor/splicing factor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12601–12606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635129100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velazquez-Dones A, Hagopian JC, Ma CT, Zhong XY, Zhou H, Ghosh G, Fu XD, Adams JA. Mass spectrometric and kinetic analysis of ASF/SF2 phosphorylation by SRPK1 and Clk/Sty. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41761–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagopian JC, Ma CT, Meade BR, Albuquerque CP, Ngo JC, Ghosh G, Jennings PA, Fu XD, Adams JA. Adaptable Molecular Interactions Guide Phosphorylation of the SR Protein ASF/SF2 by SRPK1. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:894–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma CT, Hagopian JC, Ghosh G, Fu XD, Adams JA. Regiospecific phosphorylation control of the SR protein ASF/SF2 by SRPK1. J Mol Biol. 2009;390:618–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngo JC, Giang K, Chakrabarti S, Ma CT, Huynh N, Hagopian JC, Dorrestein PC, Fu XD, Adams JA, Ghosh G. A Sliding Docking Interaction Is Essential for Sequential and Processive Phosphorylation of an SR Protein by SRPK1. Mol Cell. 2008;29:563–76. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novoyatleva T, Heinrich B, Tang Y, Benderska N, Butchbach ME, Lorson CL, Lorson MA, Ben-Dov C, Fehlbaum P, Bracco L, Burghes AH, Bollen M, Stamm S. Protein phosphatase 1 binds to the RNA recognition motif of several splicing factors and regulates alternative pre-mRNA processing. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:52–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghigna C, Giordano S, Shen H, Benvenuto F, Castiglioni F, Comoglio PM, Green MR, Riva S, Biamonti G. Cell motility is controlled by SF2/ASF through alternative splicing of the Ron protooncogene. Mol Cell. 2005;20:881–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huynh N, Ma CT, Giang N, Hagopian J, Ngo J, Adams J, Ghosh G. Allosteric interactions direct binding and phosphorylation of ASF/SF2 by SRPK1. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11432–40. doi: 10.1021/bi901107q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egloff MP, Cohen PT, Reinemer P, Barford D. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of human protein phosphatase 1 and its complex with tungstate. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:942–59. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan PI, Stojdl DF, Marius RM, Scheit KH, Bell JC. The Clk2 and Clk3 dual-specificity protein kinases regulate the intranuclear distribution of SR proteins and influence pre-mRNA splicing. Exp Cell Res. 1998;241:300–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cazalla D, Zhu J, Manche L, Huber E, Krainer AR, Caceres JF. Nuclear export and retention signals in the RS domain of SR proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6871–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6871-6882.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colwill K, Pawson T, Andrews B, Prasad J, Manley JL, Bell JC, Duncan PI. The Clk/Sty protein kinase phosphorylates SR splicing factors and regulates their intranuclear distribution. Embo J. 1996;15:265–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeakley JM, Tronchere H, Olesen J, Dyck JA, Wang HY, Fu XD. Phosphorylation regulates in vivo interaction and molecular targeting of serine/arginine-rich pre-mRNA splicing factors. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:447–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mermoud JE, Cohen P, Lamond AI. Ser/Thr-specific protein phosphatases are required for both catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5263–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mermoud JE, Cohen PT, Lamond AI. Regulation of mammalian spliceosome assembly by a protein phosphorylation mechanism. Embo J. 1994;13:5679–88. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurley TD, Yang J, Zhang L, Goodwin KD, Zou Q, Cortese M, Dunker AK, DePaoli-Roach AA. Structural basis for regulation of protein phosphatase 1 by inhibitor-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28874–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutfreund H. Kinetics for the life sciences: receptors, transmitters and catalysts. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1995. [Google Scholar]