Abstract

Several acculturation theories note the importance of surrounding context, but few studies describe neighborhood influences on immigrant adaptation. The purpose of this study was to examine relationships among neighborhood immigrant concentration, acculturation, and alienation for 151 women aged 44–80 from the former Soviet Union who lived in the US fewer than 13 years. Participants resided in 65 census tracts in the Chicago area with varying concentrations of Russian-speaking and diverse immigrants. Results from self-report questionnaires suggest that the effect of acculturation on alienation varies depending on neighborhood characteristics. The study also demonstrates the complexity of individual and contextual influences on immigrant adoption. Understanding these relationships is important for developing community-based and neighborhood-level interventions to enhance the mental health of immigrants.

Although several prominent acculturation theories note the importance of the surrounding context (Birman, Trickett, & Buchanan, 2005; Oppedal, Roysamb, & Sam, 2004), few empirical studies have examined neighborhood contextual influences on acculturation and adaptation of immigrants. The people who comprise a neighborhood create a collective milieu that shapes social interactions, and therefore neighborhood of residence may be a determinant of the way immigrants learn to master the challenges of living in a new country. Immigrants who reside in neighborhoods with different ethnic concentrations experience different social environments (Birman et al., 2005). In addition, the ethnic backgrounds of nonimmigrant neighbors may also have an effect on acculturation. Thus, a neighborhood’s ethnic mix may lead to different trajectories of acculturation and adaptation, and consequently different mental health outcomes (Bhugra & Arya, 2005).

A common pattern of immigrant residential mobility is initial settlement in an urban ethnic enclave “gateway” community—usually a lower income neighborhood where large numbers of people from the same ethnic background reside (Bartel, 1989; Chiswick & Miller, 2005; Chow, Jaffee, & Snowden, 2003). This is followed by movement to residential areas of greater diversity and higher income over time, believed to correspond to increasing acculturation (Funkhouser, 2000). Recent trends indicate, however, that immigrants are increasingly bypassing ethnic enclaves and settling in neighborhoods with diverse immigrant and nonimmigrant populations (Clark & Patel, 2004). This may be particularly true for smaller immigrant groups that do not have the numbers to form a large homogeneous ethnic enclave, such as those from the former Soviet Union who entered the United States as immigrants and refugees during the 1990s.

Immigrants who lack access to familiar cultural items and social networks are at high risk for acculturative stress and isolation (Litwin, 1997; Weine et al., 1998). Ethnic enclaves provide an opportunity to be connected to familiar aspects of preimmigration life while developing new ties and identities (Mazumdar, Mazumdar, Docuyanan, & McLaughlin, 2000). Living in such neighborhoods may provide easy access to special foods, ethnic social networks, and other resources that contribute to immigrants’ positive mental health through shared culture and language (Chun & Akutsu, 2003; Finch & Vega, 2003; Sam & Berry, 2005). High same-ethnic immigrant concentration might also provide a critical mass of individuals that warrants specific community resource allocation such as language interpreters (Dunn, 1998; Valtonen, 2002). Another benefit of living in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of foreign-born population appears to be a greater number of grocery stores and pharmacies (Small & McDermott, 2006).

On the other hand, living in residentially segregated neighborhoods with primarily same-ethnic immigrant neighbors and restricted exposure to majority culture may limit opportunities for acculturation to a new language, identity, and behavior. Relatively few studies, however, have examined the effects of living in urban neighborhoods with high or low concentrations of foreign-born residents from diverse countries of origin (Clark & Patel, 2004; Yu & Myers, 2007).

People who immigrate as midlife and older adults acculturate more slowly than adolescents and young adults, and have more difficulty learning a new language and mastering cultural or social conventions (Schwartz, Pantin, Sullivan, Prado, & Szapocznik, 2006; Stevens, 1999). Neighborhood environment is particularly important for elderly immigrants, who tend to have less social and geographic mobility and fewer opportunities than younger people to interact with the majority population (Robert & Li, 2001). Indeed, although adults who work outside their neighborhood boundaries may have a great deal of contact with the majority population, many midlife and older immigrants are unable to obtain jobs—in part because of their slower mastery of language or lack of transferability of skills. As a result, they may be underemployed or unemployed at an earlier age than they might have been in their native countries (Remennick, 2004). Limited or restricted social interactions, inability to comprehend and navigate mainstream society, and delayed sense of belonging can lead to cultural alienation (Nicassio, 1983). Prior studies suggest that alienation can be an important mediator of the relationship between acculturation and mental health for immigrants, highlighting the importance of this construct as a measure of adaptation for immigrants (Miller, Sorokin, Wang, Choi, Feetham, & Wilbur, 2006).

Understanding the differential effects of neighborhood immigrant concentration on the acculturation process in relation to cultural alienation can provide insights for targeting individual and community-level interventions. Little attention has been paid to the experience of immigrants living in diverse neighborhoods with significant numbers of immigrants from other countries and cultures, particularly with regards to benefits or barriers to adaptation that may derive from high or low neighborhood diversity. The purpose of this study is to examine relationships among selected characteristics of neighborhood immigrant concentration, acculturation, and cultural alienation for recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union residing in metropolitan Chicago.

BACKGROUND

Acculturation and Immigrant Adaptation

Acculturation is a term used broadly to include selective adoption and retention of language, identity, behavior, and values as they are maintained or transformed by the experience of coming into contact with another culture (Gordon, 1964). It is a complex cognitive and emotional process of conflict and negotiation between two cultures and includes changes that occur as one accommodates to a host culture (Teske & Nelson, 1992). The most commonly measured dimensions are language fluency, identity, and behavior (Hazuda, Stern, & Haffner, 1988; Magana et al., 1996; Phinney, 1990). Identity involves the unique integration of two or more ethnicities, and implies a sense of belonging as well as commitment to a cultural group that becomes part of one’s self-concept. Behavioral acculturation is related to adoption of observable aspects of the dominant culture, including lifestyle.

Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of considering host and heritage cultural dimensions independently, as well as measuring language, identity, and behavior as separate components to predict behavior and mental health, as they may have different developmental trajectories (Birman & Trickett, 2001; Miller, Wang, Szalacha, & Sorokin, in review; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). Furthermore, recent research has highlighted the importance of understanding acculturation as a transactional variable between individuals and their environment. Studies of immigrant acculturation have yielded contradictory findings with respect to whether acculturation to majority culture has positive or negative effects (Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian, Morales, & Bautista, 2005; Miller, Chandler, Wilbur, & Sorokin, 2004), leading some to question the construct itself. In response to these critiques, the importance of local context for acculturation has been highlighted. In particular, research suggests that the link between acculturation and adaptation may be moderated by local community contexts (Birman et al., 2005). In other words, consistent with an ecological perspective (Trickett, 2002), whether acculturation is adaptive or not depends in part on the demands of the surrounding context. Few studies have examined the effects of neighborhood same-ethnic immigrant concentration, and fewer have examined the impact of living in neighborhoods with immigrants from diverse countries of origin.

Neighborhood Concentration, Acculturation, and Adaptation

The immigrant concentration of neighborhoods has been found to predict acculturation even when accounting for differences in socioeconomic status (SES). Living in neighborhoods with a higher same-ethnic immigrant concentration may be a disadvantage insofar as it is related to a lower probability of language fluency in the host language and retention of native language (Portes & Schauffler, 1994). Birman et al. (2005) found that Russian behavioral acculturation was higher for adolescents who lived in a community with high same-ethnic density compared to those in a low ethnic density community, and the opposite effects for American behavioral acculturation. In addition, although there was no difference between the communities for Russian identity, those living in communities with lower Russian ethnic density had higher American identity. Moreover, the relationship between acculturation and adaptation was found to be moderated by the neighborhood context. Higher American identity predicted higher grades and fewer school absences for Russian adolescents in the community with a high density of same-ethnic, Russian residents, but higher American behavioral acculturation predicted those outcomes in the lower density community.

Schnittker (2002) demonstrated that neighborhood ethnic concentration had moderating effects on the relationship between acculturation and Chinese immigrants’ self-esteem. In neighborhoods with low concentration of Chinese residents, English language use was related to higher self-esteem, but in predominately Chinese neighborhoods, Chinese cultural participation predicted higher self-esteem. In summary, neighborhood immigrant concentration may have important implications for immigrant adaptation. We know relatively little, however, about the ways in which neighborhood immigrant concentration interacts with acculturation to predict adaptation, particularly for midlife and older adults.

Cultural Alienation

Several studies have examined the impact of acculturation on various indices of adaptation for immigrants including anxiety, depressed mood, somatic symptoms, and family dysfunction (McCubbin, Thompson, & McCubbin, 1996; Miller, Sorokin, Wilbur, & Chandler, 2004; Oh, Koeske, & Sales, 2002). Relatively few researchers have examined alienation as a measure of psychological adaptation in immigrants. Cultural alienation refers to a person’s rejection or sense of dissociation and detachment from prevailing social norms and values (Cozzarelli & Karafa, 1998; Schacht, 1970). It is characterized by estrangement and absence of a sense of belonging (Bernard, Gebauer, & Maio; 2006; Nicassio, 1983). Although the concept of alienation has been defined in several ways, Seeman’s (1959) original conceptualization included five characteristics: powerlessness, meaninglessness, “normlessness,” isolation, and self-estrangement, and referred to a more general sense of alienation from the values of mainstream society.

Although some immigrants may consciously reject aspects of the dominant or traditional values and beliefs, they also may not have the personal or social resources to master or feel part of their new society. Negative outcomes of this sense of separation between individuals and their environment include feelings of despair, hopelessness, stress, anxiety, anguish, tension, or demoralization (Clarke, 2002; Schacht, 1970). Most studies of cultural alienation in immigrants are limited to high school and college students (Klomegah, 2006; Suarez, Fowers, Garwood, & Szapocznik, 1997). Fewer studies have examined cultural alienation in immigrant adults.

Nicassio (1983) developed an instrument to assess alienation as an outcome measure of postimmigration adjustment in Southeast Asian immigrants. He found that alienation was significantly, negatively correlated to SES, English language proficiency, media use, and social relationships with Americans. Significant differences on alienation were found by ethnicity, with individuals of Hmong background reporting highest scores for alienation, followed by Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese refugees.

Using a Russian version of Nicassio’s scale (Birman & Tyler, 1994), Vinokurov, Birman, and Trickett (2000) found that age at arrival was significantly correlated, but time in the United States was negatively correlated, with alienation. In addition, higher alienation scores were found for women from the former Soviet Union (FSU) who retained their Russian identities compared to men, and higher alienation was predicted by Russian behavior. This scale was also used by Miller et al. (2006) in midlife and older women from the FSU. In that study, the effects of acculturation on depressed mood were mediated by alienation, and higher acculturation levels promoted mental health by reducing alienation, family, and personal stress. These findings suggest the importance of cultural alienation as a measure of adjustment among adult immigrants in general, and those from the FSU in particular.

The purpose of this study was to examine the contribution of neighborhood immigrant concentration and acculturation to cultural alienation for recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union. The study was guided by an ecological perspective, which takes into account the interaction between individuals and their context and is characterized by the “nature of the environment and person–environment transaction (Trickett, 2002, p. 160).” From this perspective, acculturation of individuals is seen as embedded within a local community context that influences the ways in which acculturation of individuals unfolds as well as which styles of acculturation may be adaptive (Birman et al., 2005). For these reasons indicators of ethnic composition of the local community were central to this study. In addition to examining an indicator of Russian immigrant concentration (i.e., proportion of Russian speaking population), we also examined the proportion of noncitizen residents as an indicator of diverse immigrant concentration. Because a higher rate of poverty has been associated with higher immigrant concentration in neighborhoods (Chow et al., 2003), we controlled for it in these analyses.

Based on the literature review, we expected that older immigrants would experience more alienation, whereas length of time in the United States would be related to decreased alienation (Vinokurov et al., 2000). We also expected that American acculturation variables would be related to lower alienation, and Russian acculturation to higher alienation (Miller et al., 2006; Nicassio, 1983). Finally, consistent with ecological theory (Trickett, 2002), we anticipated that neighborhood concentration of both same-ethnic and diverse immigrants would moderate the relationship between acculturation and alienation. Based on prior research with adolescents (Birman et al., 2005), we expected that American acculturation would have a greater impact on reducing alienation in neighborhoods with a lower concentration of Russian immigrants. Because prior research has not used measures of acculturation that differentiated among language, identity, or behavior in studies pertaining to neighborhoods with diverse concentrations of immigrants, we considered this aspect of the analyses as exploratory.

METHOD

Participants

This study uses a cross-sectional, descriptive design to examine relationships among neighborhood immigrant concentration, acculturation, and cultural alienation for midlife and older immigrant women from the FSU. The women in the cohort were participants in a recently completed, larger study of acculturation and health (Miller, Chandler, et al., 2004; Miller, Sorokin, et al., 2004). For this follow-up study, new information regarding neighborhood context was collected, as well as updated data on demographic characteristics, acculturation, and alienation.

Women in the existing cohort were eligible for the original study if they were 40–70 years old, immigrated to the United States from the FSU during the previous 8 years, were married, and had at least one child living in the United States. The latter two criteria were included because the original study examined family adaptation variables that are not included in the present analysis. Recruitment strategies included flyers and posters in businesses and health clinics, Russian language radio and newspaper advertisements, and network sampling. The women reside in urban and suburban neighborhoods of metropolitan Chicago. The original study initially enrolled 226 women. Attrition for this study over 4 years was only 4%, resulting in an extremely stable and committed cohort of 216 women who completed all four rounds of data collection. Of these, 197 women lived in Cook and Lake Counties of Illinois, and 151 (77%) of them returned completed questionnaires for this follow-up study.

In this study, the mean age of the participants was 62.50 (SD = 8.79); their ages ranged from 44.00 to 79.81 years old. The mean number of years in the United States was 8.39 (SD = 2.17), with a range of 4.30–13.00 years. Consistent with immigration patterns from the FSU, virtually all of the women (143; 94.70%) were married, and the majority came from the former Soviet Republics of Ukraine and Russia. Jewish ethnicity was reported by 96 (63.50%) of the women. Nevertheless, for all participants, Russian was their primary language while living in the FSU, and they were comfortable and not opposed to completing questionnaires in that language. The women were highly educated in their former country, with approximately three quarters of the sample having at least some post-high school education.

Procedures

Questionnaire packets were sent to the women in the existing cohort with letters inviting them to participate in a follow-up study to examine neighborhood influences on their health. Packets that were returned without forwarding addresses were followed up by telephone calls and use of backup contacts provided in the original study. Women were offered $15 as incentive, which was mailed after receipt of their questionnaires. The institutional review board of the investigators’ university approved the study.

Measures

Census tracts served as proxies of women’s neighborhoods. Using geographic information system (GIS) software (ArcGIS 9.1), each participant’s current address was address-matched (geocoded) to identify the census tract in which she lived. Participants lived in 65 different census tracts. We examined two aspects of neighborhood immigrant concentration: proportion of Russian immigrants and diverse immigrants. Russian immigrant concentration was measured by the percentage of the population for whom Russian is the primary language at home (median = 3.40%, range = 0–18.00%). We used percentage speaking Russian as their primary language at home rather than percentage born in the FSU or those of Russian descent because Russian descent alone is not a specific measure of the proportion of recent immigrants from the FSU. Many people of Eastern European Jewish backgrounds consider themselves to be of Russian descent, even if they were born in the United States. Those who are not first generation immigrants or children of recent immigrants, however, do not use Russian as their primary home language. In addition, those born in other former republics consider themselves Russian in the United States (Persky & Birman, 2005). Because immigrants are not eligible for citizenship until they live in the United States for at least 5 years, percentage of the population who are noncitizens was chosen as an indicator of the diverse immigrant concentration of the neighborhood (Mdn = 15.93%, range = 1.89–44.22%). Percentage of residents with family incomes below the federal poverty line was used to reflect the neighborhood poverty rate; this variable was added to control for differences in neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics. Census data were obtained from the Summary File 3 of the 2000 U.S. Decennial Census.

Self-report questionnaires were used to assess acculturation and cultural alienation. All questionnaires were translated into Russian using backtranslation and modified committee methods (Brislin, 1980; Garyfallos et al., 1991; Harkness & Schoua-Glusberg, 1998). Five components of acculturation were measured by subscales of the Language, Identity and Behavior (LIB) Acculturation Scale (Birman & Trickett, 2001). The English Language subscale includes nine items related to the use of English in selected situations. (Because all women were fluent in Russian, we did not measure Russian language acculturation.) Two identity subscales with four items each examine American and Russian identity and two 15-item behavior subscales examine American and Russian lifestyle behaviors. Items were rated on a Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = very much), and mean scores were calculated for each subscale. For this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93 for the English language subscale; 0.87 and 0.86 for American and Russian identity subscales, respectively; and 0.87 and 0.80 for the American and Russian behavior subscales, respectively.

Alienation was measured by the Russian version (Birman & Tyler, 1994) of the Alienation Scale originally developed by Nicassio (1983). The Alienation Scale is a 10-item instrument that was developed to measure the degree of social and cultural estrangement experienced by immigrants in the United States. This scale includes such items as “It is difficult for me to understand the American way of life” and “I feel all alone in America.” Items are rated on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree), and mean scores were calculated after several items were reversecoded. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.82.

RESULTS

Means, standard deviations, and ranges of the self-report demographic, neighborhood, acculturation, and alienation variables are presented in Table 1. Results of bivariate correlations among all continuous variables are presented in Table 2. Length of the time in United States was related positively to both American identity (r = .24, p<.01) and English language (r = .22, p<.01), with both of these acculturation variables increasing with longer time in the United States. Age was negatively related to American behavioral acculturation (r = −.40, p<.01) and English language (r = −.44, p<.01), with older participants having lower acculturation scores on these variables. In contrast, age was positively related to Russian behavioral acculturation (r = .48, p<.01), with older participants reporting more Russian behavior.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Demographic, Acculturation, Neighborhood, and Alienation

| Variable | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 62.70 | 8.50 | 44.10–79.80 |

| Time in U.S. (years) | 8.40 | 2.20 | 4.30–13.00 |

| Acculturation | |||

| English language | 2.18 | .57 | 1.00–4.00 |

| American identity | 2.04 | .75 | 1.00–4.00 |

| Russian identity | 2.95 | .80 | 1.00–4.00 |

| American behavior | 2.10 | .50 | 1.00–3.53 |

| Russian behavior | 3.17 | .46 | 1.75–4.00 |

| Neighborhood | |||

| Diverse immigrant concentration | 19.15 | 11.08 | 1.89–44.22 |

| Russian immigrant concentration | 5.79 | 3.74 | .00–18.00 |

| % Below poverty level | 12.58 | 11.16 | .79–44.17 |

| Alienation | 2.44 | .50 | 1.00–3.70 |

Table 2.

Correlations Among Demographic, Acculturation, Neighborhood, and Alienation

| Age | Time in U.S. |

EL | AI | RI | AB | RB | Russian immigrants |

Diverse immigrants |

% Below poverty |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in U.S. | .251** | |||||||||

| English (EL) | −.439** | .221** | ||||||||

| American identity (AI) | −.032 | .244** | .300** | |||||||

| Russian identity (RI) | .093 | −.058 | −.169* | −.448** | ||||||

| American behavior (AB) | −.401** | .128 | .606** | .502** | −.271** | |||||

| Russian behavior (RB) | .483** | .103 | −.351** | −.297** | .320** | −.581** | ||||

| Russian immigrants | −.032 | .016 | .129 | −.118 | .225** | −.153 | .189* | |||

| Diverse immigrants | .133 | −.155 | −.192** | −.105 | .006 | −.208** | .111 | .239** | ||

| % Below poverty level | .457** | .109 | −.214** | −.033 | .014 | −.189* | .346** | −.051 | .328** | |

| Alienation | .216** | −.102 | −.448** | −.517** | .175* | −.535* | .442** | .161 | .068 | .108 |

p < .05;

p < .01.

The two neighborhood immigrant concentration indicators were modestly, but positively correlated (r = .24, p<.01), indicating that neighborhoods with higher Russian concentration also had proportionately more diverse immigrant concentration. In addition, having a higher percentage of residents below the poverty line in the neighborhood was significantly and positively associated with a higher percentage of diverse immigrant concentration (r = .33, p<.05), but not with Russian immigrant concentration (r = −.05, p = ns). The higher the Russian immigrant concentration, the higher the Russian identity (r =.23, p<.01) and Russian behavior (r = .19, p<.05), and participants living in neighborhoods with higher diverse immigrant concentration reported lower English language (r = −.19, p<.01) and American behavior (r = −.21, p<.01).

To test the impact of neighborhood immigrant concentration and acculturation on alienation, a hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis was conducted. To account for the impact of individual demographic characteristics (age and time in the United States), these variables were entered in the first step of the hierarchical regression. The five acculturation variables were added in step 2, and the neighborhood immigrant concentration and poverty variables were added in step 3. Interactions between the two neighborhood (Russian immigrant concentration and diverse immigrant concentration) and five acculturation variables were computed after centering the variables, resulting in five interaction terms for Russian immigrant concentration by acculturation and five terms for diverse immigrant concentration by acculturation. In step 4, the regression was run twice. In the first regression, only the interactions terms involving Russian immigrant concentration were added, and in the second regression, only the interaction terms involving diverse immigrant concentration were added. To interpret significant interactions, the relationships of the acculturation variables to alienation for participants living in neighborhoods with higher versus lower immigrant concentrations were plotted (Figs. 1, 2, 3). For the purpose of illustration, the neighborhoods were divided using one standard deviation and above the centered mean to represent high immigrant concentration, and one standard deviation and below the median to represent lower immigrant concentration (Holmbeck, Li, Schurman, Friedman, & Coakley, 2002).

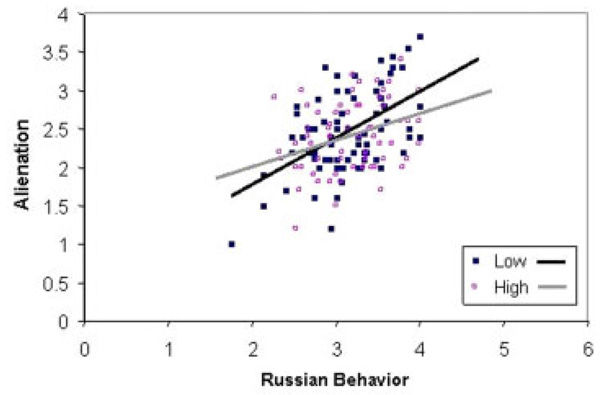

Figure 1.

Russian behavior by alienation within neighborhoods with low and high diverse immigrant concentration.

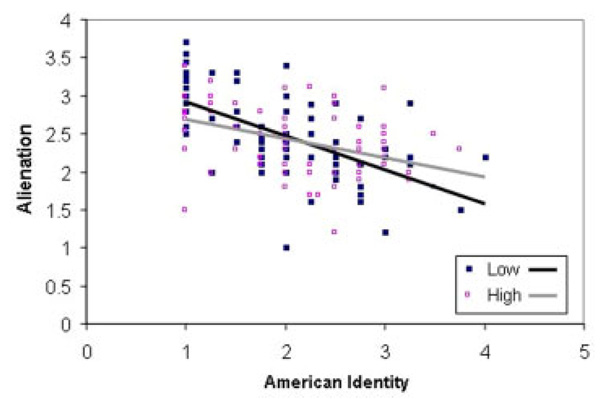

Figure 2.

American identity by alienation within neighborhoods of low and high diverse immigrant concentration.

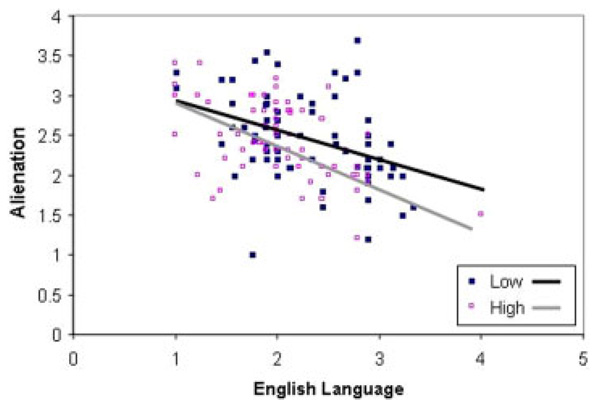

Figure 3.

English language by alienation within neighborhoods of low and high diverse immigrant concentration.

Main Effects

In the multivariate hierarchical regression analysis, age was significant in step 1 (Table 3), so that older age was related to greater alienation. However, with the addition of acculturation variables in step 2 this relationship was rendered nonsignificant. Length of time in the United States was not significantly associated with alienation. In step 2, four of the five acculturation variables significantly contributed to alienation. Specifically, Russian behavioral acculturation was related to increased alienation, whereas English language, American identity, and Russian identity were associated with decreased alienation. Given significant correlations for age, alienation, and Russian behavioral acculturation (see Table 2), we can conclude that the effect of age on alienation was mediated through Russian behavioral acculturation (Baron & Kenney, 1986).

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression of Alienation on Demographic, Acculturation, and Neighborhood Variables

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | p | b | p | b | p | b | p |

| Demographic (block 1) | ||||||||

| Age | .25 | .004 | −.09 | .268 | −.06 | .467 | .01 | .953 |

| Time in U.S. | −.15 | .074 | .05 | .536 | .04 | .623 | .06 | .400 |

| Acculturation (block 2) | ||||||||

| Russian identity | −.19 | .013 | −.23 | .003 | −.20 | .009 | ||

| Russian behavior | .28 | .002 | .26 | .005 | .12 | .186 | ||

| American identity | −.40 | <.001 | −.40 | <.001 | −.45 | .000 | ||

| American behavior | −.13 | .198 | −.10 | .323 | −.21 | .049 | ||

| English language | −.20 | .026 | −.26 | .005 | −.21 | .022 | ||

| Neighborhood (block 3) | ||||||||

| Russian immigrant concentration | .16 | .034 | .17 | .017 | ||||

| Diverse immigrant concentration | −.13 | .100 | −.24 | .003 | ||||

| % below poverty level | .01 | .866 | .10 | .256 | ||||

| Interactions (block 4) | ||||||||

| Diverse immigrants × Russian identity | .14 | .065 | ||||||

| Diverse immigrants × Russian behavior | −.28 | .002 | ||||||

| Diverse immigrants × American identity | .23 | .004 | ||||||

| Diverse immigrants × American behavior | −.11 | .325 | ||||||

| Diverse immigrants × English language | −.22 | .012 | ||||||

| R2 | .07 | .45 | .47 | .55 | ||||

| R2 change | .07** | .38*** | .03* | .07** | ||||

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

The four relationships between acculturation and alienation remained significant in step 3 with the addition of neighborhood variables. In step 3, neighborhood Russian immigrant concentration was positively associated with alienation, with those living in neighborhoods with proportionately more Russian residents reporting greater alienation, although the change in variance accounted for by this step was only marginally significant. Diverse immigrant concentration and neighborhood poverty were not significantly associated with alienation.

Interactions

None of the interactions between Russian immigrant concentration and acculturation variables was significant; therefore, only the second model that included interactions between diverse immigrant concentration and acculturation is presented in Table 3. Three of the five interaction terms between diverse immigrant concentration and acculturation variables were significant; specifically, the interactions with Russian behavior, American identity, and English language. This suggests that diverse immigrant concentration of the neighborhood moderates the effects of acculturation on alienation. The effect of Russian behavioral acculturation on alienation (with higher levels of Russian behavior associated with higher alienation) is greater for women living in neighborhoods with low immigrant concentration (Fig. 1). The effect of American identity on alienation (with higher levels of American identity being associated with reduced alienation) was also greater in low immigrant concentration neighborhoods (Fig. 2). The association between higher English language proficiency and reduced alienation, however, was greater in neighborhoods with high immigrant concentration (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The study findings demonstrate that population characteristics of neighborhoods where immigrant women reside are associated with acculturation and alienation. The effects of neighborhood characteristics in our study corroborate some findings with other immigrant populations, and highlight the distinctiveness of this particular immigrant group. Consistent with prior research (Chow et al., 2003; Eschbach, Ostir, Patel, Markides, & Goodwin, 2004), neighborhoods with a higher concentration of diverse immigrants had a higher concentration of residents below the poverty level, as is expected of traditional “gateway” immigrant neighborhoods. Although there is often an association between SES and ethnic concentration, however, in this study it is the latter that most directly predicts acculturation. Neighborhood poverty was not associated with higher concentration of Russian immigrants, suggesting that overall, Russian immigrants live in relatively higher socioeconomic neighborhoods. Nevertheless, older participants were more likely to live in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty. Taken together, these findings highlight the particularly precarious situation of elderly immigrants who have limited incomes and do not experience the upward mobility of the younger members of their immigrant group.

Length of time in the United States was not associated with any of the three neighborhood indicators. This suggests that FSU immigrants do not follow the traditional model of urban migration, or may leave higher density Russian neighborhoods relatively sooner than other immigrant groups did in the past. This finding is consistent with the observations of Clark and Patel (2004), who note a trend in which recent immigrants are now less likely than in the past to reside in neighborhoods with high same-ethnic immigrant concentration. This phenomenon may be due to better communication methods that support ethnic networking by telephone or Internet, better transportation to access cultural goods and services, or high motivation for upward mobility at the expense of maintaining ethnic enclave communities.

Neighborhoods that had more Russian residents were also more likely to be populated by other immigrants from diverse backgrounds. This suggests that new Russian immigrants, who do not have enclaves of significant size compared to others such as Hispanics in Chicago, settle in what might be termed diverse immigrant enclaves. This could make their acculturation and adaptation experiences different from those from larger immigrant groups who constitute a neighborhood majority. We do not know the “tipping point” for the concentration of immigrants at which a neighborhood becomes an ethnic enclave. It is possible that for a relatively small group like Russian immigrants in Chicago, neighborhoods with only 18% Russians— the highest reported in this group—function essentially as enclaves.

Contrary to the implications suggested by Portes and Schauffler (1994), we did not find a significant negative relationship between neighborhood Russian immigrant concentration and American acculturation (English language, American behavior, American identity). There are several possible explanations for this. This group of midlife and older immigrants, many of whom came to this country as refugees, often lives in government subsidized apartments and thus may not freely choose their neighborhoods. Therefore, some recent arrivals with low levels of American acculturation may be resettled in predominantly American neighborhoods. However, their social lives may be limited primarily to their own building and they may not interact with the rest of the geographic neighborhood. It is also possible that some people with higher levels of American acculturation choose to live in Russian neighborhoods that may not be enclaves per se, but are more diverse neighborhoods with enough Russian cultural presence to support cultural activities and identity.

American identity and behavior acculturation were not significantly correlated with neighborhood Russian immigrant concentration, contrary to the findings of Vinokurov et al. (2000) who found that those living in communities with higher Russian concentration reported significantly lower American behavioral acculturation. In our study, both American identity and behavior were positively associated with diverse immigrant concentration, however. This suggests that residence in neighborhoods with proportionately more Russian immigrants and more diverse immigrants are associated with different acculturation profiles, but the cross-sectional design of this study precludes determination of causality. Women in neighborhoods with higher Russian immigrant concentrations reported higher Russian behavior and Russian identity. This is probably due to the fact that residence in Russian neighborhoods provides more opportunities for Russian cultural engagement. It is also possible that those who feel more connection to Russian culture choose to live in Russian immigrant neighborhoods. Further, residing in these neighborhoods may lead to development of stronger Russian social networks and perpetuate loyalty to Russian culture.

The central findings of the study relate to the impact of demographic, neighborhood, and acculturation characteristics on alienation. Age was significant in step 1 of the multivariate hierarchical regression analysis (Table 3), so that as expected, older age was related to greater alienation (Vinokurov et al., 2000). The addition of acculturation variables in step 2, however, rendered this relationship nonsignificant. Russian behavioral acculturation played a mediating role between age and alienation. This suggests that it is not age per se, but rather the fact that older people retain and exhibit more Russian behavior and feel less connected with American culture that predicts higher alienation. Contrary to expectations, length of time in the United States was not significantly associated with alienation.

American identity and English language competence were related to lower alienation, as expected (Miller et al., 2006; Nicassio, 1983; Vinokurov et al., 2000). American behavioral acculturation was not related to alienation. However, considering that American behavior was significantly related to reduced alienation in bivariate correlations, and the multicolinearity among the three American acculturation variables, these findings may merely suggest that identity and language are relatively stronger predictors of reduced alienation for this sample than behavior. Interestingly, Russian acculturation variables had both a positive and a negative relationship with alienation. Whereas Russian behavioral acculturation was associated with increased alienation, higher Russian identity was associated with lower alienation. It is possible that because both Russian and American identity predicted reduced alienation, these results indicate the advantage of Russian-American biculturalism. In addition, a sense of belonging and identification with either culture may keep a person from feeling marginalized and alienated. This finding suggests the importance and benefits of strong ethnic identity for immigrants, and the distinctiveness of the identity component of acculturation from language and behavior.

Residence in neighborhoods with greater Russian immigrant concentration was positively associated with alienation, adjusting for acculturation, age, time in the United States, and neighborhood diverse immigrant concentration. Most important, neighborhood diverse immigrant concentration moderated the effects of three of the five acculturation variables (American identity, English language, and Russian behavior). The effect of American identity in reducing alienation was stronger in low concentration diverse immigrant neighborhoods than high diverse immigrant neighborhoods, suggesting that internalizing ties with American culture is more important for those who reside in low immigrant concentration neighborhoods, possibly because it makes them feel a better fit for their cultural environment. These findings are consistent with prior research by Birman et al. (2005).

On the other hand, English language proficiency was a more important factor in reducing alienation for those residing in higher immigrant neighborhoods. This finding underscores the impact of living in diverse immigrant neighborhoods. Because neighborhoods populated by recent immigrants are often located in urban areas, they may provide more daily opportunities for social engagement than less densely populated suburbs; knowing English, often the only common language of diverse immigrant neighborhoods, may improve communication and help negotiate everyday life, thus helping people feel less alienated.

Finally, the association between Russian behavior and alienation was particularly strong in neighborhoods with low diverse immigrant concentrations, perhaps because there are few other immigrants whose cultural differences may buffer the contrast between Russian immigrants and their American neighbors. Neighborhoods with low immigrant concentration have fewer or no sources of ethnic goods, such as ethnic grocery stores and non-English language movie rentals. For those living in neighborhoods with high immigrant concentration, engaging in one’s own ethnic cultural activities may be part of local routine, and ethnic behavior may be less dependent on people’s comfort with mainstream culture.

There are several limitations to this study. First, there are no generally accepted indicators of diversity and concentration for immigrant neighborhoods that have been used to examine acculturation and alienation. Additional research is recommended that examines more carefully the specific ethnicities that comprise diverse immigrant neighborhoods, as well as developing or testing more complex measures of neighborhood diversity. Second, because the study was limited to a cohort of women who recently completed a 4-year longitudinal study, the sample did not include very recent immigrants (i.e., those in the United States fewer than 4 years). This is not a random sample of women, nor a random sample of neighborhoods. Different sampling methods are recommended to clarify relationships among neighborhood immigrant concentration, acculturation, and alienation. Third, this study was cross-sectional, which does not allow establishment of the time sequence of events and thus causality.

Another limitation, as noted frequently in the literature, is that census tracts were used as proxies for participants’ neighborhoods because of the availability of census data to measure immigrant concentration. However, census tracts do not necessarily capture neighborhoods that are meaningful for social interactions or resources. For immigrants who have limited mobility, perceived neighborhoods may be limited to one or two blocks and high ethnic concentrations on those blocks would not necessarily emerge from the census tract statistics. In addition, because 15 variables were included in each of the regression analyses, the ratio of variables to participants in the OLS regressions is somewhat less than optimal. Some of the findings, such as the final effect for American behavioral acculturation and the trend in the final interaction effect for diverse immigrants by Russian identity, should be interpreted with caution. Finally, results are not generalizable to immigrants from other ethnic backgrounds. We do not know whether these findings would hold for immigrants from countries with much higher representation in the United States, such as Mexican Americans.

This study demonstrates the complexity of the effects of acculturation on alienation. These effects are not static, but take place within unique neighborhood community contexts. Intervention goals, therefore, may be different in neighborhoods with high versus low diverse immigrant concentration. This complexity should be taken into consideration especially for designing interventions to promote healthy immigrant adaptation for older adults. For example, where there is high diverse immigrant concentration, neighborhood-level interventions that bring disparate ethnic groups together may help reduce alienation. Because better English language proficiency is associated with lower alienation in those neighborhoods, support services might be directed toward increasing interaction with neighbors and emphasizing shared resources across ethnic groups. This might be accomplished by holding combined English language classes, multilingual legal clinics, or other services offered to immigrants in convenient neighborhood locations. English language conversation clubs could be established that are not restricted to same-ethnic participants.

In neighborhoods with low immigrant concentration, where alienation is greater with higher Russian behavior and lower American identity, reducing alienation might be supported by facilitating exposure to the mainstream while supporting biculturalism. Older adults who live in subsidized housing located within neighborhoods that have few other immigrants may benefit from programs that are aimed toward decreasing the residential social isolation that perpetuates exclusively Russian behavior. This might include opportunities to experience mainstream culture while supporting access to ethnic cultural activities and networks within and outside geographic boundaries. For example, providing transportation to organized events in ethnically concentrated neighborhoods and facilitating contact with the extended ethnic community through Internet-based native language media can help reduce alienation for those living in low ethnic diversity neighborhoods.

Local policymakers and social service program planners in predominantly nonimmigrant, nonenclave neighborhoods should demonstrate flexibility and recognize the presence of smaller immigrant populations. More resources for them should be provided within mainstream activities. For example, translation services can be readily available at all health care settings through telephone translation services. American movies with foreign language subtitles can help immigrants to be exposed to American life despite the language barrier, which for older immigrants may never be overcome.

In summary, the study demonstrates the complexity of individual and contextual influences on immigrant adaptation. Without taking context into account, research provides an incomplete description of the impact of acculturation after immigration. Understanding these relationships is of foremost importance for developing community-based interventions for individuals and neighborhood-level programs to reduce alienation and enhance mental health of immigrants.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grants # R01 HD38101, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Arlene M. Miller, PhD, Principal Investigator, and # P30 NR009014 Center for Reducing Risks in Vulnerable Populations (CRRVP) from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Bartel AP. Where do the new U.S. immigrants live? Journal of Labor Economics. 1989;7:371–391. doi: 10.1086/298213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard MM, Gebauer JE, Maio GR. Cultural estrangement: The role of personal and societal value discrepancies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:78–92. doi: 10.1177/0146167205279908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D, Arya P. Ethnic density, cultural congruity and mental illness in migrants. International Review of Psychiatry. 2005;17:133–137. doi: 10.1080/09540260500049984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett E. Cultural transitions in first-generation immigrants: Acculturation of Soviet Jewish refugee adolescents and parents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2001;32:456–477. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett E, Buchanan RM. A tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35:83–101. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-1891-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Tyler FB. Acculturation and alienation of Soviet Jewish refugees in the United States. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1994;120:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of cross-cultural psychology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1980. pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick BR, Miller PW. Do enclaves matter in immigrant adjustment? City and Community. 2005;4:5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun KM, Akutsu PD. Acculturation among ethnic minority families. In: Chun KM, Balls-Organista P, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WAV, Patel S. Residential choices of the newly arrived foreign born: Spatial patterns and the implications for assimilation. Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research; 2004. Retrieved October 1, 2007, from http://computing.ccpr.ucla.edu/ccprwpseries/ccpr_026_04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. Demoralization: Its phenomenology and importants. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;36:733–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzarelli C, Karafa JA. Cultural estrangement and terror management theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KM. Rethinking ethnic concentration: The case of Cabramatta, Sydney. Urban Studies. 1998;35:503–527. [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach K, Ostir GV, Patel KV, Markides S, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: Is there a barrio advantage? American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1807–1812. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5(3):109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkhouser E. Changes in the geographic concentration and location of residence of immigrants. International Migration Review. 2000;34:489–510. [Google Scholar]

- Garyfallos G, Karastergiou A, Adamopoulou A, Moutzoukis C, Alagiozidou E, Mala D, et al. Greek version of the general health questionnaire: Accuracy of translation and validity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1991;84:371–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness JA, Schoua-Glusberg AS. Questionnaires in translation. ZUMA-Nachrichten Spezial. 1998 January;3:87–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda HP, Stern MP, Haffner SM. Acculturation and assimilation among Mexican Americans: Scales and population-based data. Social Science Quarterly. 1988;69:687–706. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN, Li ST, Schurman JV, Friedman D, Coakley RM. Collecting and managing multisource and multimethod data in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:5–18. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomegah R. Social factors relating to alienation experienced by international students in the United States. College Student Journal. 2006;40:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian M, Morales L, Bautista DEH. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H. The network shifts of elderly immigrants: The case of Soviet Jews in Israel. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1997;12:45–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1006593025061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magana JR, de la Rocha O, Amsel J, Magana HA, Fernandez MI, Rulnick S. Revisiting the dimensions of acculturation: Cultural theory and psychometric practice. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:444–468. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar S, Mazumdar S, Docuyanan F, McLaughlin C. Creating a sense of place: The Vietnamese Americans and Little Saigon. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2000;20:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Sorokin O, Wang E, Choi M, Feetham S, Wilbur J. Acculturation, social alienation, and depressed mood in midlife women from the former Soviet Union. Research in Nursing and Health. 2006;29:134–146. doi: 10.1002/nur.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Chandler P, Wilbur J, Sorokin O. Acculturation and cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife immigrant women from the former Soviet Union. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19(2):47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2004.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Sorokin O, Wilbur J, Chandler PJ. Demographic characteristics, menopausal status, and depression in midlife immigrant women. Women’s Health Issues. 2004;14:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM, Wang E, Szalacha L, Sorokin O. Longitudinal changes in acculturation for immigrant women from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. doi: 10.1177/0022022108330987. (Accepted for publication). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicassio PM. Psychosocial correlates of alienation: Study of a sample of Indochinese refugees. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1983;14:337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, Koeske GF, Sales E. Acculturation, stress and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in the United States. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;142:511–526. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppedal B, Roysamb E, Sam DL. The effect of acculturation and social support on change in mental health among young immigrants. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Persky I, Birman D. Ethnic identity in acculturation research: A study of multiple identities of Jewish refugees from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2005;36:557–572. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Schauffler R. Language and the second generation: Bilingualism yesterday and today. International Migration Review. 1994;28:640–661. [Google Scholar]

- Remennick L. Language acquisition, ethnicity, and social integration among former Soviet immigrants of the 1990s in Israel. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2004;27:431–454. [Google Scholar]

- Robert SA, Li LW. Age variation in the relationship between community socioeconomic status and adult health. Research on Aging. 2001;23:234–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam D, Berry J, editors. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. London: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht R. Alienation. New York: Doubleday; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J. Acculturation in context: The self-esteem of Chinese immigrants. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65:56–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Pantin H, Sullivan S, Prado G, Szapocznik J. Nativity and years in the receiving culture as markers of acculturation in ethnic enclaves. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:345–353. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman M. On the meaning of alienation. American Sociological Review. 1959;24:783–791. [Google Scholar]

- Small ML, McDermott M. The presence of organizational resources in poor urban neighborhoods: An analysis of average and contextual effects. Social Forces. 2006;84:1698–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G. Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults. Language in Society. 1999;28:555–578. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez SA, Fowers BJ, Garwood CS, Szapocznik J. Biculturalism, differentness, loneliness, and alienation in Hispanic college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1997;19:489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Teske RH, Nelson BH. Acculturation and assimilation: A clarification. American Ethnologist. 1992;1:351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ. Context, culture, and collaboration in AIDS interventions: Ecological ideas for enhancing community impact. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;23:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Valtonen K. The ethnic neighbourhood: A locus of empowerment for elderly immigrants. International Social Work. 2002;45:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurov A, Birman D, Trickett EJ. Psychological and acculturation correlates of work status among Soviet Jewish refugees in the U.S. International Migration Review. 2000;34:538–559. [Google Scholar]

- Weine S, Vojvoda D, Becker DF, McGlashan TH, Hodzic E, Lamb D, et al. PTSD symptoms in Bosnian refugees one year after resettlement in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:562–564. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Myers D. Convergence or divergence in Los Angeles: Three distinctive ethnic patterns of immigrant residential assimilation. Social Science Research. 2007;36:254–285. [Google Scholar]