Abstract

Background

Giant cystic lymphangiomas of the liver are rare malformations of the lymphatic system usually found in children.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old man presenting with right upper quadrant abdominal pain for 7 months visited our clinic. Ultrasound, CT, and MRI examination demonstrated a giant cystic mass in the right trisegment of the liver. The patient underwent surgical resection and histological results of the resected specimen confirmed the diagnosis of giant cystic lymphangioma. The right upper quadrant abdominal pain subsided after the surgical resection and the patient recovered well.

Conclusion

Surgical resection is an effective therapy in treating giant cystic lymphangioma.

Keywords: Hepatic, Lymphangioma, Abdominal pain, Surgical treatment

Introduction

Lymphangiomas are rare benign tumors occurring most often in young children extra-abdominally, where the loose connective tissue allows for easy expansion of lymphatic channels. Intraabdominal lymphangiomas account for less than 5% of all lymphangiomas cases and are mostly encountered in the pediatric population [1–3]. Lymphangiomas of the liver are extremely rare in adult patients. With this report, we would like to share our experience in managing a male adult with giant cystic lymphangioma in the liver complicated with right upper abdominal pain.

Case report

A 35-year-old male presenting with a 7-month abdominal pain of the right upper quadrant visited our department. He was diagnosed with asymptomatic gallstones 3 years ago. He had no history of abdominal surgery or other medical history, and he has been healthy otherwise.

Due to the right upper quadrant pain, the patient had undergone hepatic puncture drainage at a local hospital 6 months before he visited our hospital. Computed tomography (CT) showed a well-defined, giant, heterogeneous mass (199 × 155 mm) in the right trisegment (Couinaud IV, V, VI, VII, VIII). Around 4,000 ml fluid containing blood was drained out from the mass over a period of 3 days. Erythrocytes and fibrin were present in the fluid, but malignant cells were not. Cytology and clinical examinations at the local hospital led to an initial diagnosis of subacute hematoma. However, the abdominal pain of the right upper quadrant was not resolved after drainage.

The patient was then sent to our hospital with a chief complaint of right upper quadrant abdominal pain. On examination, there were no significant abnormalities except for a palpable liver in the right upper quadrant.

Hematology and biochemistry results showed normal white blood cell count of 2.69 × 109/L (reference range 4.0–10.0 × 109/L), low hemoglobin of 102.0 g/L (reference range 120–160 g/L), and abnormal blood platelets count of 58u109/L (reference range 100–300 × 109/L). Hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb), Hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb), and Hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) were all positive. Examination of liver function, kidney function, electrolytes, alpha-fetoprotein(s-FP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen19-9(CA19-9) was all normal.

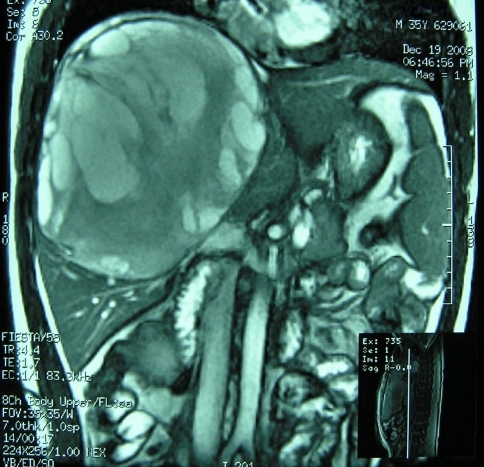

The thoracic cavity and lungs were normal on the chest film. Ultrasound scan revealed a giant non-echoic mixed cystic mass (138 × 179 mm) in the right hepatic lobe. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a giant cystic hepatic lesion (Fig. 1). Percutaneous biopsy was not performed considering the risk of bleeding and the possibility of malignant seeding in case that the lesion was neoplastic. Preoperative diagnosis could not be made solely based on imaging. The differential diagnoses included cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, and hepatic cyst with bleeding.

Fig. 1.

Coronal cover of T-2 weight MRI showing a giant cystic mass involving segment IV, V, VI, VII, VIII of the liver

The patient later discharged himself from hospital due to the financial reasons. However, he returned 2 months later for another enhanced CT scan, which showed no significant changes in the size and character of the lesion; the laboratories studies also showed no noticeable changes. CT scan discovered a huge mass causing a great pain in the right upper quadrant. The laboratory and image findings were not sufficient to differentiate the benign or malignant nature of the mass, but it had a well-defined border with the liver tissues, so we decided that the tumor should be completely removed without further laparoscopic assessment/surgery.

During surgery, a giant, cystic, and smooth mass was found at the right trisegment of the liver (Couinaud IV, V, VI, VII, VIII). The falciform ligament and the left lateral lobe were extruded. Right trisegment resection of the liver combined with a cholecystectomy was therefore performed. There were no intra- or extra-hepatic duct dilatations, and the postoperative course was uneventful.

Histology

Histology of the resected specimen revealed a huge cystic mass about 250 × 230 mm in size. The mass was cystic and multilocular. Macroscopically, it was yellow-white in color, with a gel-like consistency, and formed into a massive blood clot (Fig. 2). The specimen consisted of multiple thin-walled cysts, filled with clear serous fluid containing red blood cells. On microscopic examination, the specimen consisted of multiple cystic spaces lined by a layer of cells, morphologically consistent with mature differentiated endothelium (Fig. 3). Based on these histological findings, a diagnosis of lymphangioma originating from the liver was rendered.

Fig. 2.

The resected tumor and gallbladder (see arrow). The gallbladder contained gallstones

Fig. 3.

Microscopically the lesion consisting of multiple cystic spaces lined by a layer of cells, morphologically consistent with mature differentiation endothelium. (H&E, ×200)

Follow-up

The recovery was uneventful and the patient has been followed up for 17 months. He was symptom-free postoperatively, with no evidence of recurrence on subsequent abdominal imaging.

Discussion

Lymphangiomas are a group of benign tumors which are of lymphatic origin and are usually found in the neck (75%) and the axilla (20%) [1]. Abdominal lymphangioma account for less than 5% of all lymphangiomas cases, with the locations reportedly including the omentum, mesocolon, colon, mesentery, retroperitoneum, liver, gallbladder, and falciform ligament; and they are most commonly found in the pediatric population [2–4]. Abdominal lymphangiomas are a group of benign cystic tumors, which are extremely rare in the adult population, with reported frequencies of less than 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 250,000 hospital admissions [1, 5].

The exact etiology of lymphangioma remains unknown, with most authors favoring either the inflammatory and fibrotic processes or genetic predisposition. Other factors discussed include mechanical pressure and retention, traumatic factors, degeneration of lymph nodes as well as the disorders of endothelial lymphatic vascular secretion or endothelial permeability. Early onset and the frequent development in areas, where the primitive lymph sacs occur, suggest that these lymphangiomas are malformations arising from sequestrations of lymphatic tissue that fails to communicate normally with the lymphatic systems [6].

Abdominal lymphangiomas result from the developmental failure of the lymphatic system. These malformations have the typical characteristics of not only the lymphatic system, but also the smooth muscle cells in their walls, which makes them easily differentiated from mesenteric cysts originating from the mesothelial tissue. Lymphangiomas present either as unicystic or multicystic tumors whose cavities are covered with a layer of endothelium and filled with chylous or serous contents. Based on their histological appearance, lymphangiomas can be divided into three groups: (1) lymphangioma simplex or capillary lymphangioma, (2) cavernous lymphangioma, and (3) cystic lymphangioma or cystic hygroma [6]. Hepatic lymphangiomatosis is characterized by cystic dilatation of the lymphatic vessels in the liver parenchyma [7].

Usually abdominal lymphangiomas have non-specific signs or symptoms. About 40% abdominal lymphangiomas are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally on imaging [8]. The enlarging cyst displaces and compresses the surrounding structures, which can subsequently cause symptoms. In this case, the main complaint of patient is right upper quadrant pain, which we believe is related to the enlargement of the huge cystic lesion and the subsequent stretching of the hepatic capsule. Other symptoms may include nausea and vomiting due to the intestinal obstruction, ascites, displacement of the medial colic artery, and intermittent fever. Rarely, bleeding or rupture of the tumor will cause signs and symptoms of an acute abdomen [9].

An exact preoperative diagnosis is difficult and the diagnosis is usually made via laparotomy and autopsy. Laboratory results are of no use for the diagnosis of lymphangioma.

Ultrasound report reveals a simple or multiloculated, anechoic mass with internal septations [2]. CT typically shows a simple or multiloculated cystic lesion with a similar density to water. The wall of the cyst can be enhanced with an intravenous contrast injection. Similarly, with MRI, simple or multiloculated cystic lesions are seen. MRI typically demonstrates varying signal intensities on T-1 and T-2 weighted images depending on the different contents in the cystic fluid [2]. Neither CT nor MRI can provide a clear diagnosis, even though one of the major features of lymphangiomas is water density on CT or MRI [10]. The differential diagnoses in our case included hepatic cystic masses such as biliary cystadenoma, cystadenocarcinoma, and internal bleeding from cysts. Due to its rarity, the exact diagnosis was unable to be made intraoperatively.

The treatment of choice for lymphangioma is total resection. Outcomes following complete resection of abdominal lymphangiomas are generally good. Resection is often required for symptom control or diagnosis. Incomplete removal often leads to the recurrence of the cyst and related symptoms [11]. The conservative treatment, as initially attempted in our patient at the local hospital, needs to be fully evaluated. Alternative therapies for patients who are not suitable for surgical treatment include injection of sclerosants such as alcohol and OK432 into lymphangiomas [12]. However, indurations of the cyst and infection often complicate these procedures [13].

Conclusion

We report a rare case of giant hepatic lymphangioma in a 35-year-old man with right upper quadrant abdominal pain for more than 7 months; a total excision of the lesion results in complete resolution of his symptoms.

References

- 1.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, El-Sherif A, Rider KD, Jones JW. Mesenteric cystic lymphangioma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:598–603. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohba K, Sugauchi F, Orito E, et al. Cystic lymphangioma of the gall-bladder: a case report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10:693–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1995.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stavropoulos M, Vagianos C, Scopa CD, et al. Solitary hepatic lymphangioma a rare benign tumour: a case report. HPB Surg. 1994;8:33–36. doi: 10.1155/1994/63638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan K, Ricketts RR. Lymphangioma of the falciform ligament—a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1276–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takiff H, Calabria R, Yin L, Stabile BE. Mesenteric cysts and intraabdominal cystic lymphangiomas. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1266–1269. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390350048010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft Tissue Tumour. 3. Mosby: St. Louis; 1995. pp. 679–700. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlon KC, Rusch VW, Gillern S. Laparoscopy: an important tool in the staging of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:489–494. doi: 10.1007/BF02305768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen JG, Riall TS, Cameron JL, Askin FB, Hruban RH, Campbell KA. Abdominal lymphangiomas in adults. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:746–751. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser H, Mischinger HJ, Beham A, et al. Cystic retroperitoneal lymphangiomas in adults. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:322–326. doi: 10.1016/S0748-7983(97)90777-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breidahl WH, Mendelson RM. Retroperitoneal lymphangioma. Australas Radiol. 1995;39:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1995.tb00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roisman I, Manny J, Fields S, et al. Intra-abdominal lymphangioma. Br J Surg. 1989;76:485–489. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banieghbal B, Davies MR. Guidelines for the successful treatment of lymphangioma with OK-432. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:103–107. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherk M, Nikfarjam M, Christophi C. Retroperitoneal lymphangioma. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:51–54. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]