Abstract

Purpose

Pegylated interferon (Peg-IFN)-based therapy is effective in treating chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and C (CHC) but frequently induces adverse events (AEs). This study was conducted to compare the incidence of Peg-IFN-based therapy-associated AEs in Taiwanese patients with CHB and CHC.

Methods

Fifty-six patients with CHB and 103 age-, sex- and treatment duration-matched patients with CHC were enrolled. Patients with CHB were treated with Peg-IFN-α-2a 180 μg/week for 24 weeks (HBeAg+, n = 31) or 48 weeks (HBeAg−, n = 25); patients with CHC were treated with Peg-IFN-α-2a 180 μg/week plus ribavirin 1,000–1,200 mg/day for 24 weeks (genotype 2/3, n = 57) or 48 weeks (genotype 1, n = 46).

Results

Significantly higher incidences of Peg-IFN-related AEs, especially neuropsychiatric symptoms, and ribavirin-associated skin manifestations were observed in patients with CHC compared with those with CHB, with either the 24- or 48-week regimen. Frequencies of laboratory abnormalities, except for anemia, were comparable in both groups. Neither group showed overt hepatic decompensation. Frequency of dose reduction was similar between the groups. Substantially higher rates of early termination and severe AEs were observed in patients with CHC.

Conclusions

Patients with CHB treated with Peg-IFN had fewer AEs than patients with CHC treated with Peg-IFN/ribavirin. All patients were treated safely.

Keywords: Adverse events (AEs), Safety profile, Peg-IFN-based therapy, CHB, CHC

Introduction

Infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) are two clinically distinct but related diseases and chronic infection with HBV and HCV is a major global health issue. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and chronic hepatitis C (CHC) are the leading causes of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide [1]. The current standard therapy for patients with CHC, treatment with interferon (IFN)-based therapy, is associated with varying degrees of early and late adverse events (AEs) such as fatigue, myalgia, flulike symptoms, or dermatologic, hematologic, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and thyroid dysfunction, and alternations in mood [2–5].

AEs associated with treatment are critical factors in the decision to initiate and maintain therapy, and premature discontinuation of therapy may reflect the impact of treatment-related AEs on therapy. Once-weekly treatment with pegylated IFN (Peg-IFN) has been associated with a significantly reduced incidence of AEs compared with conventional IFN for patients with CHC [2].

Approved agents for the treatment of CHB fall into two categories: (1) immunomodulatory therapies, i.e., based on IFN, and (2) antiviral agents (nucleoside analogs). Based on the results of the extensive clinical development programs of Peg-IFN in patients with CHB [6–8], this drug is now approved for the treatment of both HBeAg-seropositive and HBeAg-seronegative forms of CHB.

A comparison of the safety data from the clinical study of Peg-IFN-based therapy in CHB and CHC provides a unique opportunity to investigate the effects of this treatment in patient populations with two distinct but related diseases and to better understand whether differences exist in how this regimen affects the incidence of AEs. Comparison of AEs in patients with CHB or CHC treated with Peg-IFN-α-2a has been reported in pooled data from different racial groups (North American compared with Asian patients) [9].

In Taiwan, HBV and HCV infections are endemic and are the most important agents of chronic liver disease [10, 11]. Whether the intensity and frequency of AEs are similar between Taiwanese patients with CHB and CHC who receive Peg-IFN-based therapy remain unclear. In this prospective study, we aimed to evaluate the incidence and intensity of AEs in Taiwanese patients with CHB treated with Peg-IFN and compare with Taiwanese patients with CHC patients treated with Peg-IFN plus ribavirin combination therapy.

Methods

Eligible Taiwanese patients, aged 18–65 years, were treatment-naïve, with biopsy-proven CHB or CHC. Patients were (1) seropositive for hepatitis B surface antigen (enzyme immunoassay, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and HBV DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ≥100,000 copies/mL for patients positive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) or ≥10,000 copies/mL for those negative for HBeAg; or (2) seropositive for HCV antibodies (third-generation, enzyme immunoassay, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and HCV RNA by PCR (Cobas Amplicor Hepatitis C Virus Test, version 2.0; Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ; detection limit: 50 IU/mL). Patients with HIV infection, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, Wilson disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, decompensated cirrhosis, overt hepatic failure, a current or past history of alcohol abuse, psychiatric conditions, previous liver transplantation, or evidence of hepatocellular carcinoma were excluded. Other eligibility criteria included neutrophil count ≥ 1,500 mm−3, platelet count ≥ 90,000 mm−3, hemoglobin level ≥ 12 g/dL for men and 11 g/dL for women, serum creatinine level < 1.5 mg/dL, no pregnancy or lactation, and the use of a reliable method of contraception. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital.

Patients with CHB who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were assigned a treatment protocol of Peg-IFN-α-2a 180 μg/week (Pegasys, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 24 weeks for HBeAg+ patients (n = 31) or 48 weeks for HBeAg− patients (n = 25). Patients with CHC who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were assigned a treatment protocol of Peg-IFN-α-2a 180 μg/week plus oral ribavirin 1,000 mg/day for body weight ≤ 75 kg and 1,200 mg/day for body weight > 75 kg for 24 weeks for genotype 2/3 patients (n = 57) or 48 weeks for genotype 1 patients (n = 46). All patients were monitored for further 24 weeks after termination of treatment. They had biweekly outpatient visits during the first month and monthly visits during the rest of the treatment period and the 24-week follow-up period. At each visit, a complete physical examination was performed and AEs were recorded.

An AE was defined as any change from the patient’s pretreatment baseline condition, including an intercurrent illness that occurred during the clinical course of this study after treatment had started and up to 24 weeks after the end of treatment, regardless of whether or not the investigator considered it related to Peg-IFN-α-2a treatment. A serious AE (SAE) was defined as any event that was fatal or life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalization or prolonged hospitalization, resulted in persistent or significant disability, or was a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

Values are expressed as mean ± SD and group means were compared using the Student’s t test. Frequency was compared between groups using the χ2 test with the Yates correction or Fisher exact test. All of the statistical tests were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All procedures were performed using the SPSS for Windows version 12 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

The baseline characteristics were similar between patients with CHB and patients with CHC, including body weight, histopathology, and baseline viral load (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic demographic, virologic, and clinical features of the patients

| CHB | CHC | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 56 | 103 | |

| Age (years) | 36.23 ± 10.33 | 37.43 ± 9.84 | 0.473 |

| Male sex, n | 37 (66.07%) | 70 (67.96%) | 0.810 |

| Body weight (kg) | 64.88 ± 11.24 | 67.50 ± 12.01 | 0.182 |

| Liver histopathology | |||

| HAI (total score) | 4.39 ± 2.68 | 4.01 ± 2.42 | 0.425 |

| Fibrosis, n | 0.131 | ||

| F 0–2 | 36 (87.80%) | 68 (76.40%) | |

| F 3–4 | 5 (12.20%) | 21 (23.60%) | |

| Baseline viral load (log IU/mL) | 7.65 ± 1.88 | 5.43 ± 0.99 | |

Values are mean ± SD

HAI hepatitis activity index

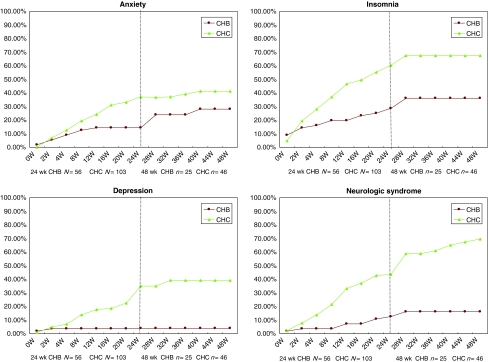

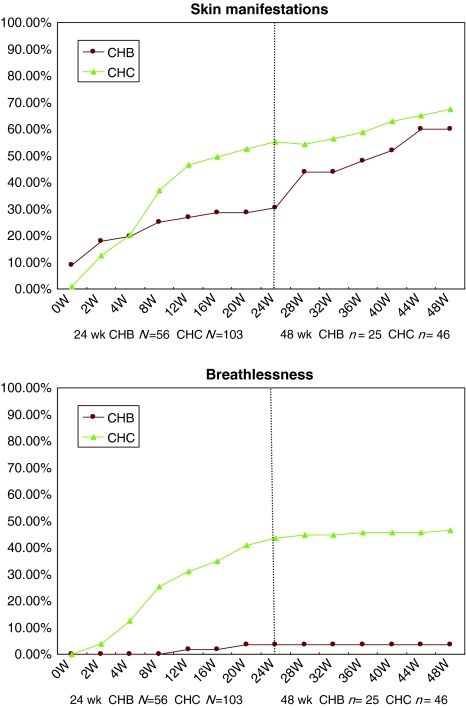

Most of our patients experienced constitutional reactions (Table 2), including fever and flulike syndrome, which mainly developed during the early stage of treatment. During the first 24 weeks of treatment, compared with CHB patients, the CHC patients had significantly higher rates of oral symptoms (including oral ulcers/dry mouth), gastrointestinal symptoms (including nausea/vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhea/constipation), visual disturbances (blurred vision), neuropsychiatric syndrome (including anxiety, depression, insomnia, and neurologic syndrome), alopecia, palpitations, skin manifestations (including skin erythematous change, skin itching and dry sensation), and breathlessness. For patients receiving 48 weeks of treatment, compared with CHB patients, the CHC patients had significantly higher rates of visual disturbances with blurred vision, neuropsychiatric syndrome, alopecia, palpitations, and breathlessness (Table 2). Most of the patients experienced gastrointestinal symptoms after fourth week of treatment. Visual disturbances, alopecia, and neuropsychiatric symptoms including anxiety, depression, insomnia, and neurologic syndrome were observed mainly in the middle or late period of treatment (Fig. 1). Ribavirin-associated skin manifestations and breathlessness were more apparent after the fourth week of therapy (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Frequencies of AEs in patients with CHB and CHC after Peg-IFN-based therapy

| AEs | Frequencies of AEs, n/N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 weeks | 48 weeks | |||||

| CHB | CHC | P | CHB | CHC | P | |

| Pyrexia | 12/56 (21.4%) | 18/103 (17.5%) | 0.543 | 7/25 (28.0%) | 11/46 (23.9%) | 0.705 |

| Flulike syndrome | 39/56 (69.6%) | 78/103 (75.7%) | 0.406 | 22/25 (88.0%) | 34/46 (73.9%) | 0.228 |

| Oral symptoms | 20/56 (35.7%) | 63/103 (61.2%) | 0.002* | 16/25 (64.0%) | 32/46 (69.6%) | 0.632 |

| Diarrhea | 8/56 (14.3%) | 19/103 (18.5%) | 0.504 | 5/25 (20.0%) | 11/46 (23.9%) | 0.706 |

| Gastrointestinal upset | 18/56 (32.1%) | 53/103 (51.5%) | 0.019* | 11/25 (44.0%) | 24/46 (52.2%) | 0.511 |

| Injection site inflammation | 2/56 (3.56%) | 10/103 (9.7%) | 0.217 | 1/25 (4.0%) | 5/46 (10.9%) | 0.414 |

| Blurred vision | 2/56 (3.6%) | 19/103 (18.5%) | 0.012* | 3/25 (12.0%) | 16/46 (34.8%) | 0.050* |

| Hearing impairment | 1/56 (1.8%) | 3/103 (2.9%) | 1.000 | 2/25 (8.0%) | 3/46 (6.5%) | 1.000 |

| Anxiety | 8/56 (14.3%) | 38/103 (36.9%) | 0.003* | 7/25 (28.0%) | 19/46 (41.3%) | 0.266 |

| Depression | 1/56 (1.8%) | 27/103 (26.2%) | <0.0001* | 0/25 (0.0%) | 18/46 (39.1%) | <0.0001* |

| Insomnia | 16/56 (28.6%) | 62/103 (60.2%) | <0.0001* | 9/25 (36.0%) | 31/46 (67.4%) | 0.011* |

| Neurologic syndrome | 7/56 (12.5%) | 45/103 (43.7%) | <0.0001* | 4/25 (16.0%) | 32/46 (69.6%) | <0.0001* |

| Alopecia | 20/56 (35.7%) | 69/103 (67.0%) | <0.0001* | 11/25 (44.0%) | 34/46 (73.9%) | 0.012* |

| Palpitations | 2/56 (3.6%) | 34/103 (33.0%) | <0.0001* | 1/25 (4.0%) | 15/46 (32.6%) | 0.006* |

| Skin manifestations | 15/56 (26.8%) | 57/103 (55.3%) | 0.001* | 14/25 (56.0%) | 31/46 (67.4%) | 0.341 |

| Breathlessness | 2/56 (3.6%) | 45/103 (43.7%) | <0.0001* | 0/25 (0.0%) | 21/46 (45.7%) | <0.0001* |

* Statistically significant

Fig. 1.

Cumulative rates of neuropsychiatric events in patients with CHB and CHC with either the 24- or 48-week regimen

Fig. 2.

Cumulative rates of skin manifestations and breathlessness in patients with CHB and CHC with either the 24- or 48-week regimen

During the first 24 weeks of treatment, CHC patients had a significant drop in body weight (P < 0.0001), hemoglobin concentration (P < 0.0001), white blood cell counts (P = 0.011), and platelet counts (P = 0.002) compared to CHB patients (Table 3). In patient groups with 48 weeks of treatment, CHC patients had significant drops in body weight and hemoglobin concentration compared with CHB patients (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, respectively; Table 3).

Table 3.

Change between baseline and nadir of body weight and blood cells counts between CHB and CHC patients with Peg-IFN-based therapy

| 24 weeks | 48 weeks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHB | CHC | P | CHB | CHC | P | |

| Peg-IFN and ribavirin associated | ||||||

| BW (kg) | −1.99 ± 1.79 (−3 ± 3%) | −4.4 ± 2.9 (−6 ± 4%) | <0.0001* | −3.28 ± 2.11 (−5 ± 3%) | −6.46 ± 3.23 (−9 ± 4%) | <0.0001* |

| Hb (g/dL) | −1.8 ± 0.84 (−12 ± 5%) | −3.8 ± 1.7 (−25 ± 11%) | <0.0001* | −2.59 ± 0.84 (−17 ± 5%) | −4.26 ± 1.65 (−28 ± 10%) | <0.0001* |

| Peg-IFN associated | ||||||

| WBC (μL) | −2,896.79 ± 1,362.05 (−46 ± 15%) | −3,508.71 ± 1,464.69 (−56 ± 13%) | 0.011* | −3,337.2 ± 1,166.71 (−54 ± 10%) | −3,529.06 ± 1,112.69 (−6 ± 12%) | 0.497 |

| PLT (1,000 μL−1) | −84.23 ± 41.55 (−43 ± 17%) | −64.27 ± 35.91 (−33 ± 17%) | 0.002* | −83.32 ± 35.4 (−46 ± 15%) | −69.82 ± 43.42 (−37 ± 19%) | 0.188 |

| ANC (μL) | −1,881.89 ± 936.77 (−57 ± 19%) | −2,054.75 ± 983.86 (−65 ± 14%) | 0.303 | −2,044.12 ± 814.89 (−61 ± 14%) | −1,992.91 ± 659.02 (−67 ± 11%) | 0.777 |

BW body weight, Hb hemoglobin, WBC white blood cell, PLT platelet, ANC absolute neutrophil count

* Statistically significant

As shown in Table 4, Peg-IFN-associated laboratory abnormalities were comparable in the two patient groups, with either 24 or 48 weeks of treatment. However, CHC patients, after either 24 or 48 weeks of treatment, had a significantly higher rate of anemia (P < 0.0001, P = 0.001, respectively). No overt hepatic decompensation developed among either group of patients during treatment and follow-up period.

Table 4.

Frequencies of laboratory abnormalities

| 24-week group, n/N | P | 48-week group, n/N | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHB | CHC | CHB | CHC | |||

| Peg-IFN associated | ||||||

| Leukopenia (<1,500 μL−1) | 0/56 (0%) | 5/103 (4.9%) | 0.163 | 1/25 (4.0%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 0.650 |

| Neutropenia (<750 μL−1) | 9/56 (16.1%) | 23/103 (22.3%) | 0.347 | 3/25 (12.0%) | 11/46 (23.9%) | 0.351 |

| Thrombocytopenia (<50 × 1,000 μL−1) | 3/56 (5.4%) | 2/103 (1.9%) | 0.346 | 2/25 (8.0%) | 3/46 (6.5%) | 1.000 |

| ALT flare | 2/56 (3.6%) | 0/103 (0.0%) | 0.123 | 1/25 (4.0%) | 1/46 (2.2%) | 1.000 |

| PT prolonged > 3 s | 0/56 (0.0%) | 0/103 (0.0%) | 1.000 | 0/25 (0.0%) | 0/46 (0.0%) | 1.000 |

| Thyroid dysfunction | 6/56 (10.7%) | 12/103 (11.7%) | 0.859 | 2/25 (8.0%) | 7/46 (15.2%) | 0.478 |

| Ribavirin (major) or Peg associated | ||||||

| Anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL) | 1/56 (1.8%) | 33/103 (32.0%) | <0.0001* | 0/25 (0.0%) | 14/46 (30.4%) | 0.001* |

| Total bilirubin (>2 mg/dL) | 1/56 (1.8%) | 9/103 (8.7%) | 0.100 | 0/25 (0.0%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 0.290 |

| Creatinine (>2 mg/dL) | 2/56 (3.6%) | 1/103 (1.0%) | 0.283 | 2/25 (8.0%) | 1/46 (2.2%) | 0.282 |

PT prothrombin time, Hb hemoglobin

* Statistically significant

The frequency of dose reduction was similar between the two groups. CHC patients tended to have a substantially higher rate of early termination and SAEs than did CHB patients with either 24 or 48 weeks of treatment. However, the difference did not reach significance (Table 5). Eight patients in the CHB group had a dose reduction or early termination, five due to AEs and three due to laboratory abnormalities. Thirteen patients in the CHC group had a dose reduction or early termination, all due to AEs. The only SAE found in the CHB group was ileus, whereas seven patients in the CHC group had SAEs due to a traffic accident, breathlessness, severe gastrointestinal bleeding, cellulitis (n = 2), syncope, and gallbladder stones complicating cholecystitis.

Table 5.

Comparison of frequency of dose reduction of Peg-IFN, early termination, and SAEs in patients with CHB versus CHC

| 24-week group, n/N | P | 48-week group, n/N | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHB | CHC | CHB | CHC | |||

| Dose reduction and early termination | 3/31 (9.7%) | 7/57 (12.3%) | 1.000 | 5/25 (20.0%) | 6/46 (13.0%) | 0.501 |

| Early termination | 0/31 (0.0%) | 2/57 (3.5%) | 0.538 | 1/25 (4.0%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 0.650 |

| SAEs | 0/31 (0.0%) | 3/57 (5.3%) | 0.549 | 1/25 (4.0%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 0.650 |

SAEs severe adverse events

Discussion

Peg-IFN and ribavirin combination therapy for CHC led to considerable side effects that were dominated by constitutional symptoms (headache, myalgia, fever, and flulike symptoms), hematologic abnormalities, and neuropsychiatric symptoms [12–16]; Peg-IFN therapy for CHB yielded an AE profile similar to that for CHC [17–19]. These recent studies in patients with HBeAg− and HBeAg+ CHB demonstrated that Peg-IFN-α-2a was well tolerated in these patients, with no unexpected AEs [8, 20].

An analysis of pooled data for comparison of AEs in patients with CHB versus CHC treated with IFN-based therapy in different ethnic groups (Northern Americans vs Asian patients) suggests that Peg-IFN-α-2a may be better tolerated in patients with CHB compared with those with CHC [9]. But this comparative analysis is purely observational and has several limitations, such as the ethnic differences. In Taiwan, HBV and HCV are endemic and are acquired via different modes of transmission. Most patients with CHB tend to acquire the infection early in life, usually perinatally, whereas many patients with CHC acquire the infection as young adults [10, 11]. The comparison of the safety data from the clinical practice of Peg-IFN-based therapy in CHB and CHC provides a unique opportunity to investigate the effects of this treatment in a Taiwanese patient population with two distinct but related diseases.

Most of our patients with CHB and CHC experienced constitutional reactions, starting early in the therapy. The incidences of fever and flulike syndrome were similar to those reported previously [8, 16, 20–22]. The severity of these symptoms is mild and dose-related and tends to diminish over the first weeks of therapy after appropriate management.

Oral symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, alopecia, and neuropsychiatric events occurred more frequently in CHC patients treated with Peg-IFN/ribavirin than in CHB patients treated with Peg-IFN therapy during the first 24 weeks of therapy. Skin manifestations and breathlessness were also significantly more frequent in patients with CHC than in those with CHB during the first 24 weeks of treatment. In the patients treated for 48 weeks, those with CHC had significantly more AEs, including palpitations, blurred visions, neuropsychiatric events, alopecia, and breathlessness, than patients with CHB. In all cases of our study, gastrointestinal symptoms appeared within 3 months of initiation of therapy and resolved rapidly with cessation of therapy.

Our analysis was consistent with the report by Marcellin and colleagues [9]: the frequency of depression-related events was lower in CHB patients than CHC patients (4 vs. 22%, P < 0.001). In our study, an apparently lower rate of neuropsychiatric-related AEs was also observed in CHB patients (P < 0.0001 ~ P = 0.003). Neuropsychiatric events including suicide, depression, relapse of drug addiction, and aggressive behavior have been reported in patients with and without previous psychiatric disorders during Peg-IFN therapy [23]. The etiology of IFN-induced depression may derive, at least in part, from the antiserotonergic effects of IFN. Increased depressive symptomatology during IFN therapy has been related to the depletion of serotonin. Discontinuation of therapy is recommended for those with severe depression, suicidal ideation or aggressive behavior [24]. In our patients’ groups, most of the neuropsychiatric events were mild and could be relieved with a serotonin uptake inhibitor and nursing or psychiatric consultations. The reasons for the lower rate of depression-related events in patients with CHB are unknown but may include host susceptibility factors or viral factors, such as the ability of HCV to infect the nervous system. There is enough evidence showing that culture and ethnic background are associated with health disparities. In the study of Marcellin and colleagues [9], a higher incidence of depression-related events was reported in Caucasian patients compared with Asian patients in both CHB and CHC studies, which is consistent with research that shows depression to be sensitive to cultural influences [25], and it is also conceivable that ethnic origin may also affect how well a drug is tolerated [9]. Evidence from psychometric studies and magnetic resonance spectroscopy suggests that central nervous system involvement of HCV infection might explain some of the fatigue, depression/anxiety and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with CHC [25, 26].

Depression is known to play an important role in the impaired HRQL of CHC patients and is a known side effect of antiviral CHC treatment [26]. In addition, mood disorders such as anxiety and depression are thought to contribute to other cognitive impairments commonly reported during interferon-based treatment, such as difficulty in thinking and concentration [27]. The contribution of non-liver, co-morbid factors (substance abuse, depression, interferon treatment) to the prevalence and magnitude of impaired cognitive function in patients with CHC may be substantial [26]. A recent study in patients with CHC has suggested a direct role of interferon response genes in generating depression during therapy [28]. Evidences from these studies may explain, at least in part, why AEs were more common in patients with CHC.

Compared with patients with CHB receiving Peg-IFN therapy, body weight loss was more severe in patients with CHC treated with Peg-IFN/ribavirin combination therapy (6 vs. 3% body weight loss). This may due to more frequent incidences of gastrointestinal symptoms, neuropsychiatric syndrome, and ribavirin-associated skin manifestations, and breathlessness in patients with CHC.

The amplitudes of decreases in hemoglobin and white blood cell and thrombocyte counts were significantly greater in CHC patients than in CHB patients with the 24-week treatment regimen. The frequencies of development of anemia were also significantly higher in CHC patients than in CHB patients with either 24 or 48 weeks of treatment. Peg-IFN causes mild bone marrow depression with a temporary decrease in neutrophil, leukocyte, and platelet counts in Peg-IFN-based treatment in both CHB and CHC patients [17]. The development of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia did not differ after Peg-IFN therapy among CHB and CHC patients. Rapid decreases in neutrophil counts may be seen in the first 2 weeks of initiation of therapy and usually stabilize over the next 4 weeks as steady-state concentrations of Peg-IFN are achieved. Neutrophil counts rapidly return to baseline after cessation of therapy. Neutropenia (<1.5 × 109 L−1) is reported to be the most common reason for dose reduction of Peg-IFN. The incidence of dose reduction for neutropenia was 18% in the Peg-IFN group and 8% in the standard IFN group [2]. However, as in our previous report, neutropenia was not associated with bacterial infection. With closely monitoring, patients could be treated safely [29].

In previous studies, during combination therapy, hemoglobin levels decreased in the first 2–4 weeks of therapy, with a mean maximal decrease of ~3 g/dL [12, 30, 31]. In our analysis, the incidence of anemia showed the greatest difference between CHB and CHC patients treated with Peg-IFN-based therapy (1.8 vs. 31.1%, respectively) and the hemoglobin concentration decreased markedly by 4.26 g/dL in the CHC group. The main reason for anemia may be associated with ribavirin combination therapy. Ribavirin causes a dose-dependent and reversible hemolytic anemia. The bone marrow-suppressive effect of IFN also contributes to the anemia [32].

The rates of thyroid dysfunction (hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism) were comparable in both CHB and CHC patients with either the 24- or 48-week regimen (Table 4). The incidence of thyroid dysfunction in our study (8.0–15.2%) seemed to be higher than the mean incidence (~6%; hyperthyroidism in 1%, hypothyroidism in 5%) indicated in a previous report [33]. Asian descent, female gender, positive pretreatment test for the presence of thyroid microsomal antibody, and age older than 60 are associated with an increased risk of thyroid dysfunction in patients with chronic HCV who receive IFN treatment [34, 35].

In our analysis, ALT flares [>10 × upper limit of normal (ULN)] were similar in both groups of patients with CHB and CHC. As in previous reports [36, 37], wherein flares in ALT are uncommon in CHC patients, they are more frequent in patients with CHB and this is reflected in the higher frequency of dose modifications in CHB. Dose modification was recommended if the ALT levels were >10 × ULN and approximately half of all CHB patients with ALT > 10 × ULN were managed by dose modification. ALT flares in other studies on CHB were associated with hepatic decompensation [38], but this did not happen in our patients. No overt hepatic decompensation occurred in either the CHB or CHC group, demonstrating that Peg-IFN-based therapy is safe for treating patients with either disease.

Although the incidences of dose reduction, early termination, and SAEs were similar in patients with CHB and CHC, Peg-IFN-based therapy tended to cause a higher frequency of early termination and SAEs in CHC patients compared with CHB patients. In a study for evaluating clinical practice data on safety and efficacy of HCV treatment with Peg-IFN in combination with ribavirin over 24 and 48 weeks, the safety profile was similar and showed the highest incidence of AEs in the first 12 weeks of treatment [39]. In another randomized controlled trial [22] comparing the efficacy and safety of Peg-IFN-α-2a 135 μg/week, Peg-IFN-α-2a 180 μg/week, and IFN-α-2a in patients with CHC, the overall safety profiles were similar for the three different treatments. According to our analysis, we agree with these previous reports [22, 39] that the dosage and duration of IFN therapy seem to have no significant effect on the safety profile.

The combination with ribavirin might be responsible for the additive incidences of AEs, at least in part. Although the Peg-IFNs are the primary drugs used to treat CHC, ribavirin may be effective in treating CHC by affecting the virus or the host, e.g., by inducing viral mutations, blocking cellular enzymes, or affecting the host immune response [40]. A combination with ribavirin is more effective than Peg-IFN alone. Ribavirin-associated AEs may be decreased, reducing the ribavirin dose and maintaining the hematocrit level.

In conclusion, Peg-IFN for Taiwanese patients with CHB caused fewer and less intense AEs than Peg-IFN/ribavirin combination therapy for Taiwanese patients with CHC, even for common Peg-IFN-related AEs. The overall lower rate of common Peg-IFN-related AEs, and especially, the significantly lower rate of neuropsychiatric-related AEs, may be an important consideration for physicians when selecting the most appropriate treatment regimen for their patients with CHB. Combination with ribavirin may contribute to the increased incidences of Peg-IFN-based therapy-associated AEs. However, most AEs occurring with combination therapy can be anticipated and managed appropriately; therefore, premature discontinuation of therapy because of the development of AEs is not required in most patients. Combination with ribavirin is more effective than Peg-IFN alone. Treatment of patients with CHC and CHB should be tailored to individual patients with considerations of Peg-IFN-related and ribavirin-associated AEs. With close monitoring, Peg-IFN-based therapy is safe for treating patients with either CHB or CHC.

Footnotes

J.-F. Yang and Y.-H. Kao contributed equally to the work.

References

- 1.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobson IM, Brown RS, Jr, Freilich B, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based or flat-dose ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2007;46:971–981. doi: 10.1002/hep.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marco V, Almasio PL, Ferraro D, et al. Peg-interferon alone or combined with ribavirin in HCV cirrhosis with portal hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2007;47:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abergel A, Hezode C, Leroy V, et al. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C with severe fibrosis: a multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing two doses of peginterferon alpha-2b. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:811–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooksley G. The treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B with pegylated interferon. J Hepatol. 2003;39(Suppl 1):S143–S145. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(03)00327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcellin P, Lau GK, Zeuzem S, et al. Comparing the safety, tolerability and quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis B vs chronic hepatitis C treated with peginterferon alpha-2a. Liver Int. 2008;28:477–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CH, Yang PM, Huang GT, Lee HS, Sung JL, Sheu JC. Estimation of seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in Taiwan from a large-scale survey of free hepatitis screening participants. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:148–155. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60231-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai CY, Chuang WL, Ho CK, et al. Associations between hepatitis C viremia and low serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels: a community-based study. J Hepatol. 2008;49:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried MW. Side effects of therapy of hepatitis C and their management. Hepatology. 2002;36:S237–S244. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840360730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aspinall RJ, Pockros PJ. The management of side-effects during therapy for hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:917–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Heintges T, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing pegylated interferon alfa-2b to interferon alfa-2b as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;34:395–403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zonneveld M, Flink HJ, Verhey E, et al. The safety of pegylated interferon alpha-2b in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B: predictive factors for dose reduction and treatment discontinuation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1163–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooksley WG, Piratvisuth T, Lee SD, et al. Peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kDa): an advance in the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:298–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen HL, Gerken G, Carreno V, et al. Interferon alfa for chronic hepatitis B infection: increased efficacy of prolonged treatment. The European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (EUROHEP) Hepatology. 1999;30:238–243. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2682–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy KR, Wright TL, Pockros PJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of pegylated (40-kDa) interferon alpha-2a compared with interferon alpha-2a in noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;33:433–438. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pockros PJ, Carithers R, Desmond P, et al. Efficacy and safety of two-dose regimens of peginterferon alpha-2a compared with interferon alpha-2a in chronic hepatitis C: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1298–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaefer M, Engelbrecht MA, Gut O, et al. Interferon alpha (IFNalpha) and psychiatric syndromes: a review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:731–746. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raison CL, Borisov AS, Broadwell SD, et al. Depression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and prediction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:41–48. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinman A. Culture and depression. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:951–953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissenborn K, Krause J, Bokemeyer M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection affects the brain—evidence from psychometric studies and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Hepatol. 2004;41:845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAndrews MP, Farcnik K, Carlen P, et al. Prevalence and significance of neurocognitive dysfunction in hepatitis C in the absence of correlated risk factors. Hepatology. 2005;41:801–808. doi: 10.1002/hep.20635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trippler M, Erim Y, Bein S, Gerken G, Schlaak JF. Identification of candidate genes for IFN-mediated depression in HCV patients. J Hepatol. 2007;46(Suppl 1):S244. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(07)62244-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JF, Hsieh MY, Hou NJ, et al. Bacterial infection and neutropenia during peginterferon plus ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C with and without baseline neutropenia in clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1000–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried MW. Side effects of therapy of hepatitis C and their management. Hepatology. 2002;36:S237–S244. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840360730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balan V, Schwartz D, Wu GY, et al. Erythropoietic response to anemia in chronic hepatitis C patients receiving combination pegylated interferon/ribavirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowdley KV. Hematologic side effects of interferon and ribavirin therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S3–S8. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000145494.76305.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prummel MF, Laurberg P. Interferon-alpha and autoimmune thyroid disease. Thyroid. 2003;13:547–551. doi: 10.1089/105072503322238809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deutsch M, Dourakis S, Manesis EK, et al. Thyroid abnormalities in chronic viral hepatitis and their relationship to interferon alfa therapy. Hepatology. 1997;26:206–210. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalgard O, Bjoro K, Hellum K, et al. Thyroid dysfunction during treatment of chronic hepatitis C with interferon alpha: no association with either interferon dosage or efficacy of therapy. J Intern Med. 2002;251:400–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayoub WS, Keeffe EB. Review article: current antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craxi A, Cooksley WG. Pegylated interferons for chronic hepatitis B. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:87–89. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan R. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection using interferon. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60(Suppl B):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Witthoft T, Moller B, Wiedmann KH, et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of peginterferon alpha-2a and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C in clinical practice: The German Open Safety Trial. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:788–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin P, Jensen DM. Ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:844–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]