Abstract

Background and aim

Transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection occurs in up to 87.5% of HBsAg-negative recipients of anti-HBc-positive donor livers in the absence of HBV prophylaxis. There is no standardized prophylactic regimen to prevent HBV infection in this setting. The aim of this study was to determine the long-term efficacy of nucleoside analogue to prevent HBV infection in this setting.

Methods

A retrospective study of HBsAg-negative patients receiving liver transplantation (LT) from anti-HBc-positive donors during a 10-year period.

Results

Twenty patients were studied, mean age was 50.2 ± 8.3 years, 40% were men, and 90% were Caucasian. The median MELD score at the time of LT was 18 (12–40). None of the patients received hepatitis B immune globulin. Eighteen patients received nucleoside analogue monotherapy: 10 received lamivudine and 8 received entecavir. None of these 18 patients developed HBV infection after a median follow up of 32 (1–75) months. One patient received a second course of hepatitis B vaccine 50 months after LT with anti-HBs titer above 1,000 mIU/mL. Lamivudine was discontinued and the patient remained HBsAg negative 18 months after withdrawal of lamivudine. Two patients who were anti-HBs positive before LT were not started on HBV prophylaxis after LT; both developed HBV infection after LT.

Conclusions

Nucleoside monotherapy is sufficient in preventing HBV infection in HBsAg-negative recipients of anti-HBc-positive donor livers. HBV prophylaxis is necessary in anti-HBs-positive recipients of anti-HBc-positive donor livers.

Keywords: Lamivudine, Entecavir, Hepatitis B immune globulin, HBV vaccine, HBV infection

Introduction

The number of patients waiting for liver transplantation (LT) far exceeds the number of donors. One approach to overcoming this problem is to expand the selection criteria for organ donors such as transplantation of livers from donors who are hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) positive and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) negative, hereafter referred as anti-HBc-positive donors. An important reason for the expansion of donor selection to include persons who are anti-HBc positive is the high prevalence of anti-HBc among the general population varying from 2% to 9% in low endemic countries such as the United States [1–4], to 53–57% in high endemic countries such as Taiwan and Singapore [5, 6]. However, transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection from anti-HBc-positive donors may occur particularly if the recipients are not immune to HBV. The incidence of HBV infection in LT recipients of anti-HBc-positive donor organs that did not receive prophylactic therapy had been reported to be 33–87.5% [1–4, 7, 8].

Currently, there is no standardized prophylactic regimen for HBsAg-negative recipients of LT from anti-HBc-positive donors. Several prophylactic regimens had been used including combination of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) and nucleos(t)ide analogue, nucleoside monotherapy, and HBIG monotherapy [6, 9–14]. HBIG is expensive and must be administered parenterally. Moreover, the vast majority of anti-HBc-positive donors have low or undetectable serum HBV DNA. Therefore, it is not clear if HBIG is needed in this setting. Several studies have shown that lamivudine monotherapy is effective in preventing HBV infection in HBsAg-negative recipients who received LT from anti-HBc-positive donors but these studies included a limited number of patients with short duration of follow up [6, 14–18].

Use of livers from anti-HBc-positive donors was first introduced at our center approximately 10 years ago. During the early years, these livers were only transplanted to recipients who were HBsAg positive. With increasing availability of safe and potent nucleos(t)ide analogues for hepatitis B, a higher percent of livers from anti-HBc-positive donors have been transplanted to HBsAg-negative recipients. The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of nucleoside monotherapy in preventing HBV transmission from anti-HBc-positive donors to HBsAg-negative LT recipients.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective study of HBsAg-negative patients who received LT from anti-HBc-positive deceased donors. Medical records of patients older than 18 years of age, who were HBsAg negative prior to LT, who received a first liver transplant from an anti-HBc-positive donor at our center during a 10-year period between January 1999 and December 2008, and who had been followed for at least 1 month post-LT were reviewed. HBsAg and anti-HBc were tested in every transplant donors. Since December 2006, single donor screening for HBV DNA was also performed. The study protocol was approved by our institutional review board.

HBV vaccination was recommended to all patients on the liver transplant waiting list, who were seronegative for HBV prior to LT. Standard doses of HBV vaccine were administered at months 0, 1, and 6. Protective response to HBV vaccine was defined as a hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) titer above 10 mIU/mL.

The recommended HBV prophylactic regimen at our hospital for HBsAg-negative patients receiving LT from anti-HBc-positive donors was nucleoside monotherapy beginning on day 1 post-LT. Patients transplanted before 31/12/2006 received lamivudine while those transplanted after 1/1/2007 received entecavir. None of the patients received HBIG. HBsAg and HBV DNA were monitored every 3 months during the first year post-LT and every 6 months thereafter. Liver panel was tested at least once a month during the first year post-LT and at least every 2–3 months during subsequent years.

The standard immunosuppressive protocol consisted of prednisone and either tacrolimus or cyclosporine, with either azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. Initiation of tacrolimus or cyclosporine was delayed and interleukin-2 inhibitor (basiliximab) was administered for the first 4 days post-LT in patients with renal insufficiency pre-LT. Prednisone and azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil were discontinued after the first year except in patients who were transplanted for autoimmune liver disease or who experienced recurrent acute rejection.

Descriptive statistics were performed. Data were expressed as mean ± SD or median and range. The duration of follow up was defined as the interval between the time of LT and the most recent HBsAg or HBV DNA test.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

Between January 1999 and December 2008, a total of 679 patients underwent LT at our hospital. Twenty-five received LT from anti-HBc-positive donors; of these, 20 were eligible for this study and 5 patients were excluded: 4 were transplanted for HBV-related end stage liver disease and 1 survived less than 1 month post-LT due to massive postoperative bleeding. All 20 donors were HBsAg negative and anti-HBc positive and all nine donors tested for HBV DNA had undetectable HBV DNA.

The mean age of the 20 patients in this study was 50.2 ± 8.3 years. Eight patients (40%) were men and 18 (90%) were Caucasian (Table 1). Seventeen patients were transplanted for end stage liver disease and three for hepatocellular carcinoma. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection was the most common cause of the underlying liver disease followed by primary sclerosing cholangitis. The mean model for end stage liver disease (MELD) score at the time of LT was 19.3 ± 7.3, and the median score was 18 (range 12–40).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who received liver transplantation from anti-HBc-positive donors

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 20 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 50.2 ± 8.3 |

| Median (range) | 52 (27–62) |

| Gender (male) | 8 (40) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 18 (90) |

| Hispanic | 2 (10) |

| Indication | |

| HCC | 3 (15) |

| End stage liver disease | 17 (85) |

| Cause of end stage liver disease | |

| Hepatitis C | 8 (40) |

| PSC | 4 (20) |

| PBC | 2 (10) |

| NASH | 2 (10) |

| Other | 4 (20) |

| MELD at LT | |

| Mean | 19.3 ± 7.3 |

| Median (range) | 18 (12–40) |

Data expressed as number (%) unless specified otherwise

No number, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, PSC primary sclerosing cholangitis, PBC primary biliary cirrhosis, NASH non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, MELD model for end stage liver disease, LT liver transplantation

Twelve patients (60%) received at least one dose of HBV vaccine before LT; of these nine completed all three doses (Table 2). Seven (58.3%) of these 12 patients developed a protective anti-HBs response after vaccination. The median interval between the last dose of HBV vaccine and LT was 24 (range 1–48) months. The median interval between the last anti-HBs test pre-LT and the time of LT was 6 (range 0–60) months.

Table 2.

HBV serology and HBV vaccination pre-transplant

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| HBV vaccination before LT | |

| Yes | 12 (60) |

| Unknown | 6 (30) |

| Anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive before LT | 2 (10) |

| Doses of HBV vaccine received | |

| 3 doses | 9 (75) |

| 2 doses | 1 (8.3) |

| 1 dose | 1 (8.3) |

| Unknown | 1 (8.3) |

| Anti-HBs titer >10 mIU/mL after vaccination | 7/12 |

| 3 doses | 6/9 (66.7) |

| 2 doses | 0/1 (0) |

| 1 dose | 1/1 (100) |

| Unknown | 0/1 (0) |

| Interval between last dose of vaccine and LT (months), median (range) | 24 (1–48) |

| Hepatitis B serology before LT | |

| Anti-HBs neg, Anti-HBc neg | 9 (45) |

| Anti-HBs pos, Anti-HBc neg | 7 (35) |

| Anti-HBs pos, Anti-HBc pos | 2 (10) |

| Anti-HBs neg, Anti-HBc pos | 1 (5) |

| Anti-HBs unknown, Anti-HBc unknown | 1 (5) |

Data expressed as number (%) unless specified otherwise

HBV hepatitis B virus, LT liver transplantation, Anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody, Anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody, pos positive, neg negative

Table 2 shows that at the time of LT, nine (45%) patients were anti-HBs and anti-HBc negative, nine were anti-HBs ± anti-HBc positive, one was anti-HBc alone positive, and one had unknown anti-HBs/anti-HBc status.

Immunosuppressive regimen and rejection treatment

Post-LT, two patients received a two-drug regimen that consisted of tacrolimus and prednisone. Eighteen patients received three-drug regimens: 13 received tacrolimus-based therapy and 5 received cyclosporine-based therapy. Nine patients received basiliximab the first 4 days post-LT. Four patients had impaired renal function during the immediate post-LT period and received renally dosed nucleoside analog during that period: two patients received renally dosed lamivudine for 7 and 12 days post-LT, and two patients received renally dose entecavir for 22 and 51 days post-LT. The mean duration of maintenance prednisone therapy was 19.4 ± 22.1 months and median was 10 (range 3–75) months. Six patients continued prednisone for more than 1 year.

Three patients (15%) underwent treatment for acute cellular rejection; one received pulse methyl prednisone only, while two received pulse methyl prednisone followed by thymoglobulin.

HBV prophylaxis and outcome of patients

None of the patients received HBIG and 18 received nucleoside monotherapy beginning on the day of LT: ten patients received lamivudine and eight received entecavir. Seventeen patients remained on nucleoside monotherapy while one discontinued nucleoside analog after completing a second course of HBV vaccine (patient A, see below). Sixteen of these 18 patients remained HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA after a mean post-LT follow up of 33.9 ± 22.9 months. The median duration of follow up was 32 (range 1–75) months. Three patients had been followed for more than 60 months and seven for more than 36 months (Table 3). Two patients died at months 5 and 6, respectively (one patient died of recurrent hepatitis C and another from chronic graft rejection) before any post-LT testing for HBsAg or HBV DNA. None of the 18 patients developed evidence of unexplained metabolic acidosis, myopathy, neuropathy or other adverse events attributable to lamivudine or entecavir during post-LT follow up.

Table 3.

HBV prophylaxis and outcome of patients receiving Anti-HBc-positive donors livers

| Received NUC | Not received NUC | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 18 | 2 | 20 |

| Lamivudine | 10 (1 switched to ETV) | N/A | 10 |

| Entecavir | 8 | N/A | 8 |

| Post-LT HBV infection | 0/16a | 2/2 | 2/18 |

| Outcome | |||

| Alive | 13 | 2 | 15 |

| Dead | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Loss to follow up | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Duration of follow up (months) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 33.9 ± 22.9 | 24 ± 2.8 | 32.8 ± 21.8 |

| Median (range) | 32 (1–75) | 24 (22–26) | 27.5 (1–75) |

| Follow up ≥ 12 months | 14 | 2 | 16 |

| Follow up ≥ 36 months | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Follow up ≥ 60 months | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Data expressed as number unless specified otherwise

HBV hepatitis B virus, NUC nucleos(t)ide analog, ETV entecavir, N/A not applicable

aTwo patients died before HBV markers were tested

Two patients were not started on HBV prophylaxis immediately after LT. One patient developed HBV infection 15 months after LT. Another patient underwent anti-HBc seroconversion at month 12 post-LT. Details of these two patients and the patient who discontinued nucleoside monotherapy are described below.

Case reports

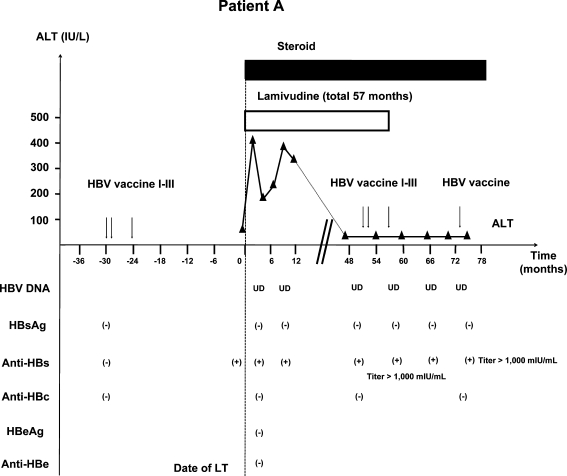

Patient A (Fig. 1) was a 45-year-old Caucasian woman with end stage cirrhosis due to hepatitis C. She completed a course of HBV vaccine 24 months before LT and was HBsAg negative, anti-HBs positive and anti-HBc negative. Anti-HBs remained detectable 1 day before LT. Her MELD score at the time of LT was 17. She was started on lamivudine monotherapy on day 1 post-LT. She did not receive HBIG. Immunosuppression initially consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone and was tapered to tacrolimus and prednisone by month 3. She was maintained on prednisone 3 mg/day for Crohn’s disease. She was never treated for acute rejection.

Fig. 1.

Patient A: 45-year-old Caucasian female received three doses of HBV vaccine with anti-HBs response pre-LT. Post-LT, patient received lamivudine monotherapy. At month 50 post-LT, she received a second course of HBV vaccine. Lamivudine was withdrawn at month 57 when her anti-HBs titer was >1,000 mIU/mL. She remained HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA 18 months after lamivudine withdrawal. However, anti-HBs titer had dropped to 83 mIU/mL 16 months after completion of the second course of HBV vaccine. One double dose of HBV DNA vaccine was administered and anti-HBs titer retested 1 month later increased to more than 1,000 mIU/mL. HBV hepatitis B virus, LT liver transplantation, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, Anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody, Anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody, HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen, Anti-HBe hepatitis B e antibody, ALT alanine aminotransferase; UD, undetectable

Anti-HBs remained detectable on three occasions post-LT; however, anti-HBs titer was not checked. At month 50 post-LT, a second (three doses) series of HBV vaccine was administered, following which her anti-HBs titer exceeded 1,000 mIU/mL. Lamivudine was stopped at month 57 post-LT. This patient remained HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA at the most recent visit, 18 months after lamivudine was discontinued. Anti-HBs remained positive but titer had dropped to 83.4 mIU/mL 16 months after completing the second course of HBV vaccination. One double dose of HBV vaccine was administered and anti-HBs titer retested 1 month later increased to more than 1,000 mIU/mL.

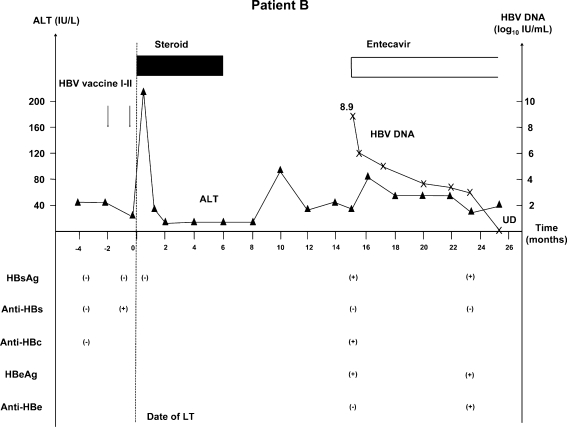

Patient B (Fig. 2) was a 27-year-old Caucasian woman with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Initially, she was negative for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc. Following a single dose of HBV vaccine, she became anti-HBs positive. She was transplanted shortly after the first dose of vaccine with a MELD score of 24 at the time of LT. After LT, she did not receive HBIG or nucleoside analogs for HBV prophylaxis. Her initial immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. She also received basiliximab during the first 4 days post-LT. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued at month 2 and prednisone at month 6 post-LT. She remained well with normal to minimally elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT). At month 15 post-LT, HBV markers were tested and she was found to be HBsAg positive, anti-HBs negative, anti-HBc positive. She was hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive with HBV DNA level of 8.9 log10 IU/mL. She was asymptomatic at that time and her ALT was 50 U/L. Entecavir 0.5 mg/day was started and serum HBV DNA rapidly decreased to <100 IU/mL after 10 months.

Fig. 2.

Patient B: 27-year-old Caucasian female received two doses of HBV vaccine with anti-HBs response before LT. Post-LT, she did not receive any HBV prophylaxis. HBV infection was diagnosed 15 months post-LT. Patient was asymptomatic and had mildly elevated ALT. Entecavir was started and HBV DNA decreased from 8.9 log10 IU/mL to <100 IU/mL within 10 months. HBV hepatitis B virus, LT liver transplantation, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, Anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody, Anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody, HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen, Anti-HBe hepatitis B e antibody, ALT alanine aminotransferase, UD undetectable

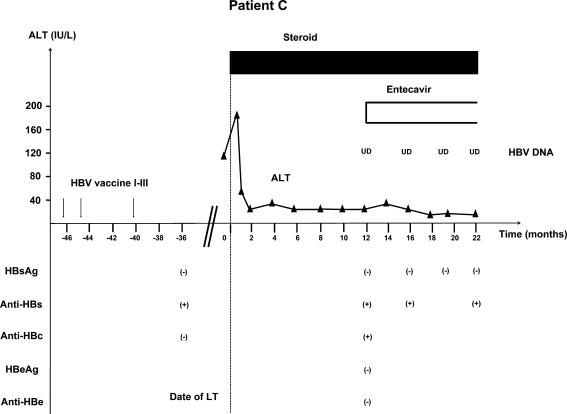

Patient C (Fig. 3) was a 61-year-old Caucasian woman who had primary biliary cirrhosis. She was seronegative for HBV markers at presentation. She completed three doses of HBV vaccine and became anti-HBs positive before LT. She did not receive HBIG or nucleoside analogs post-LT. Her immunosuppressive regimen consisted of tacrolimus and prednisone. She also received basiliximab during the first 4 days post-LT. She remained on prednisone 2 mg/day at the most recent visit. She had not received any treatment for acute cellular rejection. At month 12 post-LT, she was found to be HBsAg negative, anti-HBs positive, and anti-HBc positive (previously negative). She was HBeAg and hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe) negative with undetectable serum HBV DNA (<6 IU/mL) and had normal ALT. Entecavir was started and patient remained HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA at the most recent visit, 22 months post-LT.

Fig. 3.

Patient C: 61-year-old Caucasian female received three doses of HBV vaccine and was anti-HBs positive and anti-HBc negative before LT. She did not receive any HBV prophylaxis regimen after LT. At 12 months post-LT, she was found to be HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA, but anti-HBc positive. Entecavir was started and patient remained HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA. HBV hepatitis B virus, LT liver transplantation, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, Anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody, Anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody, HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen, Anti-HBe hepatitis B e antibody, UD undetectable

Discussion

In this study, we showed that nucleoside monotherapy (without HBIG) is sufficient in preventing HBV infection in HBsAg-negative recipients of LT from anti-HBc-positive donors. A review of the literature found six published reports of nucleoside monotherapy as HBV prophylaxis in this setting [6, 14–18]. Only 2 (2.7%) of 74 patients studied developed HBV infection; in both instances, HBV medication non-compliance was thought to be the reason for HBV infection. However, these two patients were not tested for lamivudine resistance. It should be noted that all studies included small numbers of patients (9–16 patients in each study) and the duration of post-LT follow up was short—median 19 (range 1–69) months (Table 4). Only 14 patients in these studies had been followed for more than 3 years and only 1 patient had been followed for more than 5 years post-LT [6, 14–18]. Therefore, data regarding the long-term efficacy of nucleoside monotherapy are limited. In this study, seven patients had been followed for longer than 3 years (six receiving lamivudine and one receiving entecavir); of these, three patients (all receiving lamivudine) had been followed for longer than 5 years. Our data confirmed the long-term safety and efficacy of nucleoside monotherapy in preventing HBV infection in HBsAg-negative recipients of anti-HBc-positive donor livers, including recipients who were seronegative for HBV before LT.

Table 4.

Published studies using nucleos(t)ide analog monotherapy in HBsAg-negative recipients receiving liver transplants from anti-HBc-positive donors

| Author | Number of patients | Medication | HBV vaccination, pre-LT | Hepatitis B virus serology before LT | Median follow up (months) | HBV infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HBs+ Anti-HBc+ |

Anti-HBs+ Anti-HBc– |

Anti-HBs– Anti-HBc+ |

Anti-HBs– Anti-HBc– |

||||||

| Yu [14] | 9 | LAM | N/A | 1/9 (11.1) | 1/9 (11.1) | 2/9 (22.2) | 5/9 (55.6) | 21 (2–36) | 0 (0) |

| Nery [18] | 7 | LAM | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19a | 0 (0) |

| Chen [6] | 16 | LAM | 16/16 | 2/16 (12.5) | 13/16 (81.2) | 1/16 (6.3) | 0/16 (0) | 23.5 (14–40) | 0 (0) |

| Nery [16] | 16 | LAM | N/A | 7/16 (43.8) | 0/16 (0) | 5/16 (31.2) | 4/16 (25) | 19 (1–69) | 2/16 (12.5) |

| Prakoso [15] | 10 | LAM | N/A | 3/10 (30) | 6/10 (60) | 0/10 | 1/10 (10) | 27 (2–54) | 0 (0) |

| Kobak [17] | 16 | LAM | 5/16 (31.3) | 3/16 (18.8) | 5/16 (31.2) | 4/16 (25) | 4/16 (25) | 17.5 (6–48) | 0 (0) |

| Present study | 10 | LAM | 5 (50) | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | 1 (10) | 4 (40) | 43 (8–75) | 0 (0) |

| 8 | ETV | 5 (62.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 0 (0) | 5 (62.5) | 17 (1–29) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 92 | 20.5 (1–75) | 2/92 (2.2) | ||||||

Data expressed as number (%)

No number, HBV hepatitis B virus, LT liver transplantation, Anti-HBs hepatitis B surface antibody, Anti-HBc hepatitis B core antibody, LAM lamivudine, ETV entecavir, N/A not applicable

aRange not provided

A major concern with nucleoside monotherapy in LT recipients is the risk of antiviral drug resistance. This is particularly true with lamivudine monotherapy because the incidence of lamivudine resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B has been reported to be as high as 70% after 4–5 years of treatment [19]. The risk of lamivudine resistance may be lower in patients receiving lamivudine monotherapy to prevent HBV infection from anti-HBc-positive liver donors because of lower levels of HBV replication in the donor livers and the presence of anti-HBs in some of the recipients. In this study, of the ten patients who were receiving lamivudine monotherapy, six had been followed for more than 3 years and three for more than 5 years, and six of these ten were anti-HBs negative pre-LT. These data indicate that lamivudine may be appropriate in this setting particularly in countries where lamivudine is the first-line HBV medication. Nevertheless, it should be noted that lamivudine resistance had been reported in three patients who received lamivudine to prevent HBV infection from anti-HBc-positive donors [9, 20]. One of these three patients was anti-HBs positive, anti-HBc negative before LT and lamivudine resistance was detected 3 years post-LT, while details on the other two patients were not available. Therefore, new drugs with higher genetic barrier to resistance such as entecavir and tenofovir are preferred.

The optimal duration of HBV prophylaxis is unclear. Most transplant centers recommend life-long prophylaxis [21]. To determine if antiviral therapy can be withdrawn in patients who remained anti-HBs positive post-LT, one of the patients in this study who was persistently anti-HBs positive post-LT was given a second course of HBV vaccine at month 50 post-LT. After boostering the anti-HBs titer to more than 1,000 mIU/mL, lamivudine was withdrawn. This patient remained HBsAg negative with undetectable HBV DNA 18 months after lamivudine was discontinued. This finding suggests that antiviral therapy may be withdrawn in patients who have high anti-HBs titer. However, anti-HBs titer dropped to 83 mIU/mL 16 months after completing the second course of HBV vaccine indicating that repeated booster doses of HBV vaccine or resumption of antiviral therapy is needed for continued prophylaxis against HBV infection. Attempts to replace HBIG or antiviral prophylaxis with HBV vaccination in patients transplanted for HBV-related liver failure were largely unsuccessful [22–24]. This is not surprising because these patients were unable to mount an immune response to clear HBV before LT and would be less likely to do so while receiving immunosuppressive therapy post-LT.

Two patients in this study did not receive any HBV prophylaxis post-LT. Both patients received HBV vaccine and became anti-HBs positive before LT; however, both patients showed evidence of HBV infection post-LT. These findings confirm previous reports [1, 6, 25, 26] that presence of anti-HBs alone prior to LT was not sufficient to prevent HBV infection. One study patient progressed to chronic infection with positive HBsAg and HBeAg and very high HBV DNA. She was asymptomatic and had mildly elevated ALT and HBV markers were not monitored according to protocol. She did not have any adverse outcome and HBV DNA became undetectable within 10 months of starting entecavir. The other patient underwent anti-HBc seroconversion and remained HBsAg negative with undetectable serum HBV DNA. Entecavir was started as a precautionary measure although the need for antiviral therapy in this patient was unclear.

In contrary to a recent report of entecavir-associated lactic acidosis in patients with decompensated liver disease [27], adverse events attributable to lamivudine or entecavir were not observed in any of our patients who began treatment post-transplant.

In summary, our study showed that nucleoside monotherapy (without HBIG) is sufficient in preventing HBV infection in HBsAg-negative recipients of anti-HBc-positive donor livers. Either lamivudine or entecavir monotherapy can be safely used in this setting provided the patients are adherent to their medications. HBV prophylaxis is necessary even in patients who are anti-HBs positive before LT. Further studies are needed to determine whether antiviral prophylaxis can be withdrawn in patients with high titer anti-HBs post-LT.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the Tuktawa Foundation (ASL) and the Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University Foundation, Bangkok, Thailand (WC).

Abbreviations

- LT

Liver transplantation

- Anti-HBc

Hepatitis B core antibody

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HBIG

Hepatitis B immune globulin

- Anti-HBs

Hepatitis B surface antibody

- MELD

Model for end stage liver disease

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- HBeAg

Hepatitis B e antigen

- Anti-HBe

Hepatitis B e antibody

References

- 1.Dickson RC, Everhart JE, Lake JR, Wei Y, Seaberg EC, Wiesner RH, et al. Transmission of hepatitis B by transplantation of livers from donors positive for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Liver Transplantation Database. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1668–1674. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wachs ME, Amend WJ, Ascher NL, Bretan PN, Emond J, Lake JR, et al. The risk of transmission of hepatitis B from HBsAg(–), HBcAb(+), HBIgM(–) organ donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodson SF, Issa S, Araya V, Gayowski T, Pinna A, Eghtesad B, et al. Infectivity of hepatic allografts with antibodies to hepatitis B virus. Transplantation. 1997;64:1582–1584. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas DD, Rakela J, Wright TL, Krom RA, Wiesner RH. The clinical course of transplantation-associated de novo hepatitis B infection in the liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:105–111. doi: 10.1002/lt.500030202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KH, Wai CT, Lim SG, Manjit K, Lee HL, Da Costa M, et al. Risk for de novo hepatitis B from antibody to hepatitis B core antigen-positive donors in liver transplantation in Singapore. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:469–470. doi: 10.1002/lt.500070514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YS, Wang CC, Villa VH, Wang SH, Cheng YF, Huang TL, et al. Prevention of de novo hepatitis B virus infection in living donor liver transplantation using hepatitis B core antibody positive donors. Clin Transpl. 2002;16:405–409. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donataccio D, Roggen F, Reyck C, Verbaandert C, Bodeus M, Lerut J. Use of anti-HBc positive allografts in adult liver transplantation: toward a safer way to expand the donor pool. Transpl Int. 2006;19:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prieto M, Gomez MD, Berenguer M, Cordoba J, Rayon JM, Pastor M, et al. De novo hepatitis B after liver transplantation from hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors in an area with high prevalence of anti-HBc positivity in the donor population. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:51–58. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.20786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain A, Orloff M, Abt P, Kashyap R, Mohanka R, Lansing K, et al. Use of hepatitis B core antibody-positive liver allograft in hepatitis C virus-positive and -negative recipients with use of short course of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and lamivudine. Transpl Proc. 2005;37:3187–3189. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabrega E, Garcia-Suarez C, Guerra A, Orive A, Casafont F, Crespo J, et al. Liver transplantation with allografts from hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors: a new approach. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:916–920. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodson SF, Bonham CA, Geller DA, Cacciarelli TV, Rakela J, Fung JJ. Prevention of de novo hepatitis B infection in recipients of hepatic allografts from anti-HBc positive donors. Transplantation. 1999;68:1058–1061. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199910150-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suehiro T, Shimada M, Kishikawa K, Shimura T, Soejima Y, Yoshizumi T, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection from hepatitis B core antibody-positive donor graft using hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2005;25:1169–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt D, Thomas R, Thiel D, Brems JJ. Use of hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors in orthotopic liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2002;137:572–575. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu AS, Vierling JM, Colquhoun SD, Arnaout WS, Chan CK, Khanafshar E, et al. Transmission of hepatitis B infection from hepatitis B core antibody–positive liver allografts is prevented by lamivudine therapy. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:513–517. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.23911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prakoso E, Strasser SI, Koorey DJ, Verran D, McCaughan GW. Long-term lamivudine monotherapy prevents development of hepatitis B virus infection in hepatitis B surface-antigen negative liver transplant recipients from hepatitis B core-antibody-positive donors. Clin Transpl. 2006;20:369–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nery JR, Nery-Avila C, Reddy KR, Cirocco R, Weppler D, Levi DM, et al. Use of liver grafts from donors positive for antihepatitis B-core antibody (anti-HBc) in the era of prophylaxis with hepatitis-B immunoglobulin and lamivudine. Transplantation. 2003;75:1179–1186. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000065283.98275.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celebi Kobak A, Karasu Z, Kilic M, Ozacar T, Tekin F, Gunsar F, et al. Living donor liver transplantation from hepatitis B core antibody positive donors. Transpl Proc. 2007;39:1488–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nery JR, Gedaly R, Vianna R, Berho M, Weppler D, Levi D, et al. Are liver grafts from hepatitis B surface antigen negative/anti-hepatitis B core antibody positive donors suitable for transplantation? Transpl Proc. 2001;33:1521–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(00)02580-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, Yao GB, Cui ZY, Schiff ER, et al. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714–1722. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen RD, Bonatti H, Mendez J, Aranda-Michel J, Satyanarayana R, Dickson RC. Case report of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus infection post liver transplantation from a hepatitis B core antibody donor. Am J Transpl. 2006;6:1077–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrillo R. Hepatitis B virus prevention strategies for antibody to hepatitis B core antigen-positive liver donation: a survey of North American, European, and Asian-Pacific transplant programs. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:223–232. doi: 10.1002/lt.21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenau J, Hooman N, Hadem J, Rifai K, Bahr MJ, Philipp G, et al. Failure of hepatitis B vaccination with conventional HBsAg vaccine in patients with continuous HBIG prophylaxis after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:367–373. doi: 10.1002/lt.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo CM, Liu CL, Chan SC, Lau GK, Fan ST. Failure of hepatitis B vaccination in patients receiving lamivudine prophylaxis after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2005;43:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angelico M, Di Paolo D, Trinito MO, Petrolati A, Araco A, Zazza S, et al. Failure of a reinforced triple course of hepatitis B vaccination in patients transplanted for HBV-related cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35:176–181. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barcena R, Moraleda G, Moreno J, Martin MD, Vicente E, Nuno J, et al. Prevention of de novo HBV infection by the presence of anti-HBs in transplanted patients receiving core antibody-positive livers. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2070–2074. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i13.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manzarbeitia C, Reich DJ, Ortiz JA, Rothstein KD, Araya VR, Munoz SJ. Safe use of livers from donors with positive hepatitis B core antibody. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:556–561. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.33451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange CM, Bojunga J, Hofmann WP, Wunder K, Mihm U, Zeuzem S, et al. Severe lactic acidosis during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with entecavir in patients with impaired liver function. Hepatology. 2009;50:2001–2006. doi: 10.1002/hep.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]