Abstract

Purpose

Although advanced liver fibrosis is crucial in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) for patients with chronic hepatitis B, whether it is associated with the recurrence of HCC after resection remains obscure. This study was aimed to compare the outcomes for patients with minimal or advanced fibrosis in solitary small hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related HCC.

Methods

This study enrolled 76 patients with small (<5 cm) solitary HBV-related HCC who underwent resection. The outcomes of patients with minimal and advanced fibrosis in non-tumor areas were compared. Serum markers were tested to assess the stage of hepatic fibrosis and to predict prognosis.

Results

Fourteen patients with an Ishak fibrosis score of 0 or 1 were defined as having minimal fibrosis; the remaining 62 patients were defined as having advanced fibrosis. During a follow-up period of 77.0 ± 50.7 months, 41 patients died. The overall survival rate was significantly higher (P = 0.018) and recurrence rate was lower (P = 0.018) for patients in the minimal fibrosis group. Aspartate aminotransferase–platelet ratio index (APRI) exhibited the most reliable discriminative ability for predicting advanced fibrosis. The overall survival rate was significantly higher (P = 0.003) and recurrence rate was lower (P = 0.005) for patients with an APRI of 0.47 or less.

Conclusions

For patients with solitary small HBV-related HCC who underwent resection, minimal fibrosis is associated with a lower incidence of recurrence and with better survival. APRI could serve as a reliable marker for assessing hepatic fibrosis and predicting survival.

Keywords: Aspartate aminotransferase–platelet ratio index, Fibrosis, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Recurrence

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer mortality in the world [1, 2]. In Taiwan, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common etiological factor in the development of HCC [3, 4]. Currently, surgical resection is the best treatment modality for long-term cancer-free survival [5, 6]. However, the long-term outcome after resection is still not satisfactory [1, 5]. Post-operative recurrence is common and accounts for the main cause of mortality for HCC patients who underwent resection surgery. Several factors, including tumor size, the number of tumors, presence of venous invasion and degree of liver functional reserve were demonstrated to determine post-operative tumor recurrence [1, 2, 7–10]. Advanced liver fibrosis is one of the most important factors in the development of HCC for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) [11]. Nevertheless, whether the stage of fibrosis would also be associated with the recurrence of HCC after resection has not been well addressed. As large tumor size and multinodularity might confound the impact of background fibrosis on tumor recurrence, we deduced that the stage of fibrosis might play an important role in recurrence for small and solitary HCC patients who underwent resection surgery.

Currently, there are two widely applied tests for the evaluation of liver reserve for HCC patients before surgery: measuring the hepatic venous pressure gradient for the assessment of the degree of portal hypertension, or testing for indocyanine green (ICG) retention rate at 15 min (ICG-15R) [2]. However, these tests are either too invasive or too expensive for daily practice. How to choose an easy, reliable and inexpensive method as a surrogate for pre-operative evaluation of liver reserve is crucial in a clinical setting.

Recently, several noninvasive tools have been introduced to assess the degree of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis; these include using serum biochemical markers and transient elastography [12–16]. Among them, the aspartate aminotransferase–platelet ratio index (APRI) appears to be a reliable, simple test that is easy to interpret [16–18]. It has been validated in assessing the stage of fibrosis, evaluating the reserve of liver function, as well as predicting prognosis. However, this test has seldom been applied for the evaluation of liver reserve before surgery and for prediction of prognosis for HCC patients. The aim of this study was to compare the outcomes of patients with minimal or advanced fibrosis in small and solitary HBV-related HCC. We also aimed to validate APRI as a surrogate marker in assessing the stage of hepatic fibrosis, as well as in predicting recurrence and prognosis.

Materials and methods

Patients and follow-up

This study is the subsequent cohort analysis from one prospectively conducted, retrospectively analyzed study, which enrolled 193 HBV-related HCC patients who underwent tumor resection in Taipei Veterans General Hospital from 1990 to 2002 [19]. We further analyzed a total of 76 patients with small and solitary HCC in this cohort. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) Child’s classification of liver function of A or B; (b) patients with solitary small tumors (<5 cm in size) without portal vein main trunk involvement or distant metastasis; (c) the absence of other major diseases, which may complicate surgery; (d) available post-operative pathology-verified HCC samples and adjacent non-tumor liver specimens for analysis. Patients with concurrent infection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) were excluded from this study. As nucleoside/nucleotide analogs had not yet been approved for the treatment of CHB by National Health Insurance in Taiwan before 2003, none of the cases in this cohort received anti-viral therapy before surgery. The latest laboratory data before surgery was recorded for analysis. They were all within 1 week of surgery. The grade of hepatic inflammation and stage of fibrosis in non-tumor parts of the specimen was graded according to the Ishak scoring system by a single pathologist (Lai CR) who was blind to clinical information [20]. Serum samples were collected from each subject with informed consent prior to operation and stored at −70°C. The study complies with the standards of Declaration of Helsinki and current ethical guideline. This protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board.

All patients were followed regularly every 3 months after surgery. Tumor recurrences were suspected if elevation of serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level was noted or new lesions were found by surveillance ultrasonography. Recurrences were confirmed with dynamic computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies showing contrast enhancement during arterial phase and washout in venous phase.

Biochemical and serological markers

Serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and antibody against HBeAg (anti-HBe Ab) were tested using a radioimmunoassay kit (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). Anti-HCV was measured by means of a second-generation enzyme immunoassay kit (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). Serum biochemistries including albumin, bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (Alk-P), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine and glucose were measured by a systemic multiautoanalyser (Technicon SMAC, Technicon Instruments Corp., Tarrytown, NY, USA). APRI was calculated as the ratio of [(AST/upper limit of normal value: 45 IU/L)/platelet counts (109/L)] × 100. Serum AFP level was measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (Serono Diagnostic SA, Coinsin/VD, Switzerland).

Detection and quantification of HBV DNA and genotyping and sequencing of HBV

Serum HBV DNA was detected by semi-nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as previously described and HBV DNA levels were measured by a Cobas Amplicor HBV monitor (Roche Diagnostic System, Basel, Switzerland) [19, 21]. The detection limit of this assay was 300 copies/mL. Genotyping of HBV was performed by PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism of the surface gene of HBV and further verified by sequencing [19, 21].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 17.0 for Windows, SPSS. Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The baseline characteristics to be evaluated with outcomes were selected according to the 2001 EASL guidelines [22]. Pearson chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test were used for the comparison of categorical variables, while continuous variables were compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. The accuracy of noninvasive markers for advanced fibrosis was determined by calculating the area under the curve from corresponding receiver operating curves (AUROC). The AUROC was expressed as plots of the test sensitivity versus 1-specificity. The cutoff value of AUROC was determined by MedCalc (version 4.20, MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Cumulative recurrence rates and overall survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test or Cox’s proportional hazards model. Variables with statistical significance (P < 0.05) or close to it (P < 0.1) in univariate analysis were submitted to multivariate analysis using a forward stepwise logistic regression model. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all tests.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics of all patients

The baseline demographic data are shown in Table 1. Among the 76 patients included in this study, there were 64 males and 12 females. The median age at surgery was 57.0 (range 29–82) years. The majority (90.8%) of patients was in Child grade A, and only seven (9.2%) patients were in grade B. Most patients had negative HBeAg in serum at enrollment. The median serum HBV DNA levels was 453,500 (range: undetectable to 2 × 109) copies/mL. Aside from the three patients with undetectable serum HBV DNA, 38 patients were infected with genotype B HBV and 35 patients with genotype C.

Table 1.

Clinical demographics of HCC patients and comparison of the characteristics of patients with minimal or advanced fibrosis

| All patients (n = 76) | Minimal fibrosis (n = 14) | Advanced fibrosis (n = 62) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient demographics | ||||

| Age (y/o) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 57.0; 46.3–68.0 | 53.0; 34.8–68.8 | 58.0; 46.8–68.0 | 0.348 |

| Sex (M:F) | 64:12 | 13:1 | 51:11 | 0.447 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 23.3; 21.0–25.6 | 22.1, 21.2–24.9 | 23.5; 20.9–26.3 | 0.440 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 4.0; 3.7–4.2 | 4.2; 4.1–4.4 | 3.9; 3.7–4.2 | 0.011 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 1.0; 0.8–1.3 | 0.9; 0.7–1.1 | 1.0; 0.8–1.4 | 0.079 |

| ALT (U/L) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 51.0; 29.0–81.8 | 27.0; 18.3–40.5 | 58.0; 36.0–112.3 | 0.001 |

| AST (U/L) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 43.0; 29.3–71.5 | 25.0; 19.5–29.5 | 50.5; 34.0–76.3 | <0.001 |

| ICG-15R (%) (retention rate) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 12; 9–20 | 5; 3–9 | 13; 10–21 | <0.001 |

| PT INR (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 1.02; 1.00–1.20 | 1.01; 0.94–1.14 | 1.02; 1.00–1.20 | 0.282 |

| Platelet (mm−3) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 140,000; 93,000–183,750 | 178,000; 138,250–226,500 | 132,000; 86,750–176,500 | 0.005 |

| APRI (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 0.81; 0.40–1.53 | 0.31; 0.18–0.43 | 0.97; 0.56–1.73 | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh A/B (%) | 69/7 (90.8/9.2) | 14/0 (100/0) | 55/7 (88.7/11.3) | 0.337 |

| Viral factors | ||||

| HBeAg (positive/negative) | 9/56 | 0/12 | 9/44 | 0.191 |

| HBV DNA (copies/mL) (median; 25 and 75 percentiles) | 453,500; 37,100–1.64 × 107 | 150,000; 17,950–2.13 × 106 | 2,170,000; 405,00–3.45 × 107 | 0.163 |

| Genotype B/C | 38/35 | 6/8 | 32/27 | 0.639 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||

| Tumor size (cm) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 2.5; 2.0–3.2 | 3.0; 1.9–4.0 | 2.5; 2.0–3.1 | 0.427 |

| AFP (ng/ml) (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 38.5; 8.5–638.3 | 72.0; 4.8–1151.3 | 35.0; 9.5–480.0 | 0.888 |

| Macroscopic venous invasion (%) | 5 (6.6%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (8.1%) | 0.577 |

| Cut margin ≤1 cm/>1 cm | 39 (61.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | 31 (63.3%) | 0.917 |

| Histo-pathological findings | ||||

| Edmondson grading (I/II/III/IV) | 6/48/14/1 | 1/9/3/0 | 5/39/11/1 | 0.958 |

| Microscopic venous invasion (%) | 58 (76.3%) | 11 (78.6%) | 47 (75.8%) | 1.000 |

| Capsule formation | 15 (25.4%) | 1 (10%) | 14 (28.6%) | 0.426 |

| Satellite lesions (%) | 31 (56.4%) | 8 (72.7%) | 23 (52.3%) | 0.314 |

| Ishak score-inflammation (median 25 and 75 percentiles) | 6.3 ± 3.3 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 7.1 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

ICG-15R indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min, PT prothrombin time, INR international normalized ratio, APRI aspartate aminotransferase–platelet ratio index

* P value: comparison between minimal and advanced fibrosis

Comparison of clinical demographic data between HCC patients with minimal and advanced fibrosis in non-tumor parts

The distribution of the scores of Ishak fibrosis in non-tumor parts was as follows: 0, 6 patients; 1, 8 patients; 2, 6 patients; 3, 6 patients; 4, 4 patients; 5, 11 patients; and 6, 35 patients. Fourteen patients with an Ishak fibrosis score of 0 or 1 were placed into the minimal fibrosis group; the remaining 62 patients were in the advanced fibrosis group. In comparison to those in the advanced fibrosis group, patients in the minimal fibrosis group had significantly higher serum albumin levels and platelet counts, and lower ALT, AST, APRI and ICG-15R levels and inflammation scores (Table 1). With regard to tumor factors, these two groups were similar in the incidence of macroscopic venous invasion (detected by image study), microscopic venous invasion (confirmed by histological examination), cell differentiation by Edmondson grading, capsule formation and satellite lesions. Similarly, the baseline viral factors, including the status of HBeAg, genotype and serum HBV DNA levels were also comparable between these two groups.

Validation of serum markers for predicting the stage of hepatic fibrosis in non-tumor parts

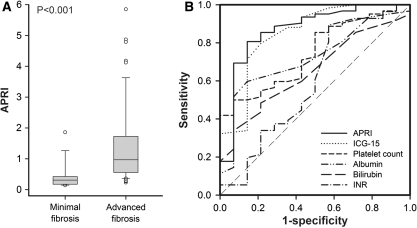

We further assessed the correlation between serum markers and the stage of fibrosis. The levels of APRI and ICG-15R were significantly higher, while platelet count and albumin were lower for patients in the advanced fibrosis group (Table 1; Fig. 1a). Receiver operating curves of the serum markers used for predicting advanced fibrosis are shown in Fig. 1b and Table 2. APRI, ICG-15R, platelet count and albumin levels all exhibited reliable discriminative ability for predicting advanced fibrosis. Indeed, the APRI yielded the highest AUROC with a level of 0.867 at a cutoff value of 0.47.

Fig. 1.

aBox and whisker graph shows the relationship between the stage of fibrosis and the APRI. The middle horizontal line inside each box depicts the median, and the width of each box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles. Vertical lines represent the 10th and 90th percentiles. b Receiver operating curves (ROCs) of APRI, ICG-15R, albumin, bilirubin, platelet count and prothrombin time INR for the prediction of advanced fibrosis in patients with small and solitary HCC

Table 2.

Comparison of area under receiver operating curves for APRI, ICG-15R, platelet count, albumin, bilirubin and prothrombin time INR for advanced fibrosis

| Cutoff | AUROC | 95% CI | Standard error | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APRI | 0.47 | 0.867 | 0.769–0.934 | 0.043 | <0.001* |

| ICG-15R (%) | 9 | 0.848 | 0.745–0.921 | 0.048 | <0.001* |

| Platelet count (mm−3) | 131,000 | 0.743 | 0.630–0.836 | 0.081 | 0.005* |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 | 0.718 | 0.603–0.816 | 0.083 | 0.011* |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.0 | 0.650 | 0.532–0.756 | 0.076 | 0.080 |

| PT INR | 0.9 | 0.577 | 0.453–0.694 | 0.083 | 0.284 |

AUROC area under receiver operating curve, CI confidence interval, APRI aspartate aminotransferase–platelet ratio index, ICG-15R indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min, PT prothrombin time, INR international normalized ratio

* P < 0.05 versus AUROC 0.5

Factors associated with overall survival in univariate and multivariate analyses

During a median follow-up period of 77.0 ± 50.7 (range 4.7–226.6) months, 41 patients died and 35 remained alive at the last visit. In addition, 45 patients had tumor recurrence after surgery. The median time of recurrence was 23.0 ± 38.4 (range 2–225) months.

As shown in Table 3, univariate analysis demonstrated that older age (P = 0.017), higher serum AST levels (P = 0.019), higher APRI values (P = 0.003), lower platelet counts (P = 0.042), higher serum AFP levels (P = 0.040), higher Ishak inflammation scores (P = 0.028) and advanced fibrosis in non-tumor parts (P = 0.018) were associated with poor overall survival.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with poor overall survival after resection surgery for small solitary HCC

| Variable | Case no. | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval CI) | P | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval CI) | P | ||

| Age > 65/ ≤ 65 y/o | 23/53 | 2.227 (1.157–4.290) | 0.017 | 2.374 (1.233–4.570) | 0.010 |

| Sex (Male/female) | 64/12 | 1.456 (0.570–3.717) | 0.432 | ||

| Albumin ≤4/>4 g/dL | 39/37 | 1.531 (0.819–2.857) | 0.182 | ||

| Bilirubin >1.5/≤1.5 mg/dL | 11/65 | 0.993 (0.416–2.369) | 0.987 | ||

| ALT >40/≤40 U/L | 45/31 | 1.214 (0.642–2.294) | 0.551 | ||

| AST >45/≤45 U/L | 35/41 | 2.125 (1.131–3.992) | 0.019 | ||

| APRI >0.47/≤0.47 | 52/24 | 3.472 (1.454–8.286) | 0.003 | 3.639 (1.524–8.691) | 0.004 |

| Platelet ≤105/>105/mm3 | 23/53 | 1.938 (1.025–3.663) | 0.042 | ||

| PT INR >1.2/≤1.2 | 15/55 | 1.621 (0.791–3.325) | 0.187 | ||

| HBeAg positive/negative | 9/56 | 1.602 (0.614–4.176) | 0.335 | ||

| HBVDNA >105/≤105 copies/mL | 48/27 | 0.471 (0.420–1.493) | 0.792 | ||

| AFP >20/≤20 ng/mL | 46/30 | 2.069 (1.034–4.143) | 0.040 | ||

| Tumor size >2 cm/≤2 cm | 48/28 | 0.831 (0.448–1.542) | 0.556 | ||

| Macroscopic venous invasion (yes/no) | 5/71 | 1.558 (0.475–5.102) | 0.464 | ||

| Microscopic venous invasion (yes/no) | 58/18 | 1.685 (0.843–3.371) | 0.140 | ||

| Cut margin ≤1 cm/1 cm | 39/24 | 1.754 (0.831–3.704) | 0.140 | ||

| Ishak inflammation >6/≤6 | 34/42 | 2.013 (1.078–3.757) | 0.028 | ||

| Advanced fibrosis/minimal fibrosis | 62/14 | 3.226 (1.144–9.096) | 0.018 | ||

If APRI was not enrolled in the multivariate analysis, age >65 years [hazard ratio (HR) 2.177, 95% CI: 1.131–4.478, P = 0.020], AFP >20 ng/mL (HR 2.233, 95% CI: 1.113–4.478, P = 0.024) and advanced fibrosis (HR 3.004, 95% CI: 1.059–8.521, P = 0.039) were the independent risk factors associated with poor overall survival

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, APRI aspartate aminotransferase–platelet ratio index, PT prothrombin time, INR international normalized ratio, AFP alpha-fetoprotein

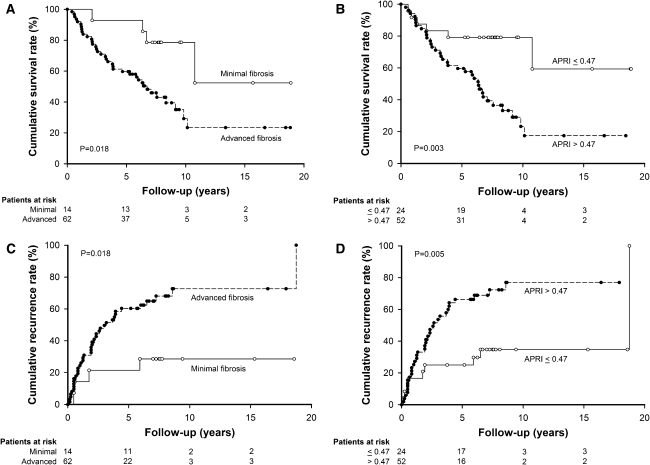

Figure 2a illustrated the overall survival rate stratified by the stage of fibrosis. The overall survival rate was significantly higher for patients in the minimal fibrosis group than their counterparts in the advanced fibrosis group. The cumulative survival rates at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 100, 92.9, 92.9 and 78.6% for patients in the minimal fibrosis group, and 91.9, 71.0, 59.7 and 29.2% for patients in the advanced fibrosis group, respectively (P = 0.018).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative overall survival and recurrences stratified by the stage of fibrosis and serum APRI level at the time of surgery. The cumulative curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by a log-rank test. Patients with advanced fibrosis had poorer overall survival (a, P = 0.018), as well as a significantly higher incidence of recurrence (c, P = 0.018) than those with minimal fibrosis in non-tumor parts. Patients with serum APRI levels of more than 0.47 at the time of surgery had poorer overall survival (b, P = 0.003), and a higher incidence of recurrence (d, P = 0.005) than their counterparts with serum APRI levels of <0.47

The overall survival rate was also significantly higher for patients with an APRI of 0.47 or less (Fig. 2b). The cumulative survival rates at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 91.7, 83.3, 79.2 and 79.2% for patients with an APRI of 0.47 or less, and 94.2, 71.2, 59.6 and 23.3% for those with an APRI more than 0.47, respectively (P = 0.003). In multivariate analysis (Table 3), age more than 65 years [hazard ratio (HR) 2.374, P = 0.010] and APRI larger than 0.47 (HR 3.639, P = 0.004) were the independent risk factors associated with poor overall survival. If APRI was not enrolled in the multivariate analysis, age more than 65 years (HR 2.177, P = 0.020), AFP larger than 20 ng/mL (HR 2.233, P = 0.024) and advanced liver fibrosis (HR 3.004, P = 0.039) were the independent risk factors to predict poor overall survival.

Predictive value of hepatic fibrosis and APRI for tumor recurrence after resection surgery

With regard to recurrence, patients in the minimal fibrosis group had lower incidences of tumor recurrence after surgery for small and solitary HCC patients (Fig. 2c). The cumulative recurrence rates at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 7.1, 21.4, 21.4 and 28.6% for patients in the minimal fibrosis group, and 24.4, 49.6, 60.3 and 72.6% for patients in the advanced fibrosis group, respectively (P = 0.018).

Figure 2d also shows that patients with an APRI of 0.47 or less had a lower incidence of developing tumor recurrence after resection surgery. The cumulative recurrence rates at 1, 3, 5 and 10 years were 16.7, 25.0, 25.0 and 34.7% for patients with an APRI of 0.47 or less, and 25.2, 53.6, 66.3 and 76.9% for patients with an APRI more than 0.47, respectively (P = 0.005).

Discussion

For patients with HCC who underwent resection surgery, tumor factors, viral factors and the degree of liver functional reserve were associated with recurrence [7–10, 23]. We recently found that tumor factors were predictive of early recurrence within 2 years after surgery, while viral factors and “field factors” in non-tumor parts influenced late recurrence [19]. The impact of field factors may be overwhelmed by the tumor factors in advanced HCC. From the current study, univariate analysis revealed that age, serum AST, APRI, AFP levels, platelet counts, as well as Ishak inflammation scores and the degree of fibrosis in non-tumor part were associated with overall survival. Additionally, age and APRI levels were the independent risk factors by multivariate analysis. It demonstrated that the confounding effect of tumor factors was minimized, and background liver fibrosis played a more important role in the prognosis for patients with small and solitary HCC. Consequently, it is implied that treatment to attenuate fibrosis might help to decrease recurrence for such patients. It may be a target for adjuvant therapy after surgery.

Adachi et al. [24] found that serum albumin and ALT levels were independent risk factors associated with recurrence in patients with small HCC who underwent resection surgery. Tumor factors, such as size, histological grade and AFP levels, were not significant in their study. It was demonstrated that liver reserve, but not tumor factors, was the predominant factor for predicting recurrence of small HCC. However, platelet count, ICG-15R and cirrhosis were not significant in predicting recurrence. This could be due to the fact that the majority of patients in their cohort were cirrhotic in non-tumor areas. The mean values of platelet count were lower (91,000 vs. 146,315/mm3) and ICG-15R values were higher (17.7 vs. 14.7%) than in our patients. This would imply that the stages of fibrosis in their patients were more advanced. Consequently, the effect of fibrosis on tumor recurrence might be diminished in the statistical analysis due to the limited number of patients with early stage fibrosis in their study. Moreover, they did not provide data for patients with minimal fibrosis; therefore, we could not evaluate the role of minimal fibrosis in recurrence from their study. Additionally, only 20.6% of patients in their cohort had chronic hepatitis B. The diversity between etiologies, stages of fibrosis and degree of liver reserve in these two studies might account for the discrepancies. However, both our group and Adachi demonstrated that “field factors” play an important role in determining tumor recurrence in patients with small HCC who underwent resection surgery.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the assessment of liver fibrosis for patients with chronic hepatitis. However, it is costly and carries risks of complications such as pain, bleeding, hemothorax, bile duct injury or penetration of abdominal viscera. Also, sampling errors and inter-observer variation decrease the reliability of liver biopsy [25]. Recently, several noninvasive serum markers were used as surrogates for evaluating the stage of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis patients. However, these markers are less widely used for patients with HCC. Previous studies demonstrated that the presence of cirrhosis or portal hypertension was not an independent risk factor of mortality or developing recurrence after surgery for small HCC [24, 26, 27]. However, they only evaluated the impact of cirrhosis and advanced fibrosis on the post-operative prognosis. The novelty of the current study is that we assessed the role of minimal fibrosis in the prognosis of patients with small solitary HCC who underwent resection surgery. Additionally, we provide an easy and feasible tool, APRI, which not only exhibits greater discriminative ability for the stage of liver fibrosis than other serum markers, but also predicts recurrence and survival for patients with small HCC. We expect it would help clinical physicians to predict outcomes before resection and to arrange adequate antiviral therapy after surgery for such patients.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, the patients enrolled in this study were all infected with HBV. For HCC patients from other etiologies, both the impact of fibrosis and the application of APRI for assessing the stage of fibrosis and predicting outcomes need further prospective study with more patients to be elucidated. Second, the number of patients enrolled in our cohort is relatively small. Although minimal fibrosis is closely related to better overall survival for patients with small and solitary HCC by univariate analysis, it failed to predict outcomes in multivariate analysis. However, APRI was an independent risk factor to be associated with overall survival. If APRI was not enrolled in the multivariate analysis, the degree of hepatic fibrosis was still an independent risk factor to predict survival. It may be attributed to the following: APRI not only serves as a surrogate for assessing the degree of hepatic fibrosis, but also reflects liver functional reserve [28] causing minimal fibrosis, which was excluded by multivariate analysis. Accordingly, APRI is a simple and powerful predictor of prognosis for patients with small HCC who underwent resection surgery.

Several newly developed noninvasive serum models, such as FibroTest, the European liver fibrosis test, FIBROSpect, Hepascore and FibroMeter, have been introduced for assessing the stage of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis patients [17]. As this is a retrospective study, another limitation of our study is that we could not compare the APRI to these new models. However, these models combine several non-routine tests, including hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1, alpha-2 globulin, alpha-2 microglobulin and apolipoprotein A. They are not readily applicable in daily practice and require additional costs. Besides, they often need complicated formula. We think that APRI still has an important role in the evaluation of liver fibrosis status because it is clinically available and easy to compute. Nevertheless, further prospective studies to evaluate the application of these newly developed serum markers for predicting prognosis of patients with small HCC are still needed.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that for small and solitary HBV-related HCC patients who underwent resection surgery, the degree of liver fibrosis is associated with tumor recurrence as well as with overall survival. APRI could serve as a surrogate for the evaluation of liver functional reserve, assessment of hepatic fibrosis and prediction of survival for such patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical support provided by the Sequencing Core Facility of the National Yang-Ming University Genome Research Center (YMGC). The Sequencing Core Facility is supported by National Research Program for Genome Medicine (NRPGM), National Science Council, Taiwan. This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC93-2321-B-010-012, NSC94-2321-B-010-010, NSC95-2321-B-010-005), and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V95C1-014, V97ER2-016, V97B1-015, Center of Excellence for Cancer Research at TVGH DOH99-TD-C-111-007), Taipei, Taiwan.

Footnotes

The authors H.-H. Hung and C.-W. Su have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hung-Hsu Hung, Email: seasonson@yahoo.com.tw.

Chien-Wei Su, Email: cwsu2@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Chiung-Ru Lai, Email: crlai@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Gar-Yang Chau, Email: gychau@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Che-Chang Chan, Email: ccchan@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Yi-Hsiang Huang, Email: yhhuang@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Teh-Ia Huo, Email: tihuo@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Pui-Ching Lee, Email: pclee@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Wei-Yu Kao, Email: wykao@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Shou-Dong Lee, Email: sdlee@vghtpe.gov.tw.

Jaw-Ching Wu, Phone: +886-2-28712121, FAX: +886-2-28745074, Email: jcwu@vghtpe.gov.tw.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Marrero JA, Rudolph L, Reddy KR. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1752–1763. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Novel advancements in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in 2008. J Hepatol. 2008;48(Suppl 1):S20–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huo TI, Lin HC, Hsia CY, Wu JC, Lee PC, Chi CW, Lee SD. The model for end-stage liver disease based cancer staging systems are better prognostic models for hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective sequential survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1920–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee LT, Huang HY, Huang KC, Chen CY, Lee WC. Age–period-cohort analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma mortality in Taiwan, 1976–2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang YH, Chen CH, Chang TT, Chen SC, Wang SY, Lee PC, Lee HS, Lin PW, Huang GT, Sheu JC, Tsai HM, Chau GY, Chiang JH, Lui WY, Lee SD, Wu JC. The role of transcatheter arterial embolization in patients with resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a nation-wide, multicenter study. Liver Int. 2004;24:419–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa K, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kokudo N, Arii S, Okazaki M, Okita K, Omata M, Kudo M, Kojiro M, Nakanuma Y, Takayasu K, Monden M, Matsuyama Y, Ikai I. Surgical resection vs. percutaneous ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a preliminary report of the Japanese nationwide survey. J Hepatol. 2008;49:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, Ohkubo T, Hasegawa K, Miyagawa S, Sugawara Y, Minagawa M, Takayama T, Kawasaki S, Makuuchi M. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:200–207. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Kosuge T. A long-term follow-up and management study of hepatocellular carcinoma patients surviving for 10 years or longer after curative hepatectomy. Cancer. 2005;104:1939–1947. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishizawa T, Hasegawa K, Aoki T, Takahashi M, Inoue Y, Sano K, Imamura H, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M. Neither multiple tumors nor portal hypertension are surgical contraindications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1908–1916. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, Peix J, Chiang DY, Camargo A, Gupta S, Moore J, Wrobel MJ, Lerner J, Reich M, Chan JA, Glickman JN, Ikeda K, Hashimoto M, Watanabe G, Daidone MG, Roayaie S, Schwartz M, Thung S, Salvesen HB, Gabriel S, Mazzaferro V, Bruix J, Friedman SL, Kumada H, Llovet JM, Golub TR. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1995–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pohl A, Behling C, Oliver D, Kilani M, Monson P, Hassanein T. Serum aminotransferase levels and platelet counts as predictors of degree of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis c virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3142–3146. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, Becka M, Burt A, Schuppan D, Hubscher S, Roskams T, Pinzani M, Arthur MJ. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704–1713. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Martens S, Sarrazin C, Bojunga J, Zeuzem S, Herrmann E. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:960–974. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su CW, Chan CC, Hung HH, Huo TI, Huang YH, Li CP, Lin HC, Tsay SH, Lee PC, Lee SD, Wu JC. Predictive value of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio for hepatic fibrosis and clinical adverse outcomes in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:876–883. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31818980ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SU, Ahn SH, Park JY, Kang W, Kim do Y, Park YN, Chon CY, Han KH. Liver stiffness measurement in combination with noninvasive markers for the improved diagnosis of B-viral liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:267–271. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31816f212e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiha G, Sarin SK, Ibrahim AE, Omata M, Kumar A, Lesmana LA, Leung N, Tozun N, Hamid S, Jafri W, Maruyama H, Bedossa P, Pinzani M, Chawla Y, Esmat G, Doss W, Elzanaty T, Sakhuja P, Nasr AM, Omar A, Wai CT, Abdallah A, Salama M, Hamed A, Yousry A, Waked I, Elsahar M, Fateen A, Mogawer S, Hamdy H, Elwakil R. Liver fibrosis: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) Hepatol Int. 2009;3:323–333. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheung RC, Currie S, Shen H, Bini EJ, Ho SB, Anand BS, Hu KQ, Wright TL, Morgan TR. Can we predict the degree of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients using routine blood tests in our daily practice? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:827–834. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318046ea9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu JC, Huang YH, Chau GY, Su CW, Lai CR, Lee PC, Huo TI, Sheen IJ, Lee SD, Lui WY. Risk factors for early and late recurrence in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2009;51:890–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang YH, Wu JC, Chang TT, Sheen IJ, Lee PC, Huo TI, Su CW, Wang YJ, Chang FY, Lee SD. Analysis of clinical, biochemical and viral factors associated with early relapse after lamivudine treatment for hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients in Taiwan. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:277–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodes J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL Conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421–430. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung IF, Poon RT, Lai CL, Fung J, Fan ST, Yuen MF. Recurrence of hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with high viral load at the time of resection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1663–1673. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adachi E, Maeda T, Matsumata T, Shirabe K, Kinukawa N, Sugimachi K, Tsuneyoshi M. Risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence in human small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:768–775. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bedossa P. Assessment of hepatitis C: non-invasive fibrosis markers and/or liver biopsy. Liver Int. 2009;29(Suppl 1):19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosaka T, Ikeda K, Kobayashi M, Hirakawa M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, Akuta N, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Kumada H. Predictive factors of advanced recurrence after curative resection of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2009;29:736–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kikuchi LOO, Paranagua-Vezozzo DC, Chagas AL, Mello ES, Alves VAF, Farias AQ, Pietrobon R, Carrilho FJ. Nodules less than 20 mm and vascular invasion are predictors of survival in small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:191–195. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31817ff199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunes D, Fleming C, Offner G, Craven D, Fix O, Heeren T, Koziel MJ, Graham C, Tumilty S, Skolnik P, Stuver S, Horsburgh CR, Cotton D. Noninvasive markers of liver fibrosis are highly predictive of liver-related death in a cohort of HCV-infected individuals with and without HIV infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1346–1353 [DOI] [PubMed]