Abstract

Background

Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) can assess liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). We evaluated whether LSM can be used to assess changes in liver fibrosis during antiviral treatment using nucleos(t)ide analogs in patients with CHB.

Methods

We recruited 41 patients with CHB who had significant liver fibrosis, normal or slightly elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (≤2 × upper limit of normal), and detectable serum hepatitis B virus DNA before antiviral treatment. Patients in Group 1 (n = 23) and Group 2 (n = 18) underwent follow-up LSM after antiviral treatment for 1 and 2 years, respectively.

Results

The mean age, ALT and LSM value of all patients (34 men and 7 women) before antiviral treatment were 46.6 ± 9.5 years, 40.6 ± 17.2 IU/L and 12.9 ± 8.6 kPa, respectively. Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) was detected in 31 patients (75.6%). Fibrosis stage was F2 in 12 (29.3%), F3 in 6 (14.6%) and F4 in 23 (56.1%) patients. After antiviral treatment, LSM values and DNA positivity decreased significantly as compared to baseline (P = 0.018 and P < 0.001 in Group 1; P = 0.017 and P < 0.001 in Group 2, respectively), whereas ALT levels were unchanged (P = 0.063 in Group 1; P = 0.082 in Group 2).

Conclusions

Our preliminary data suggest that LSM can be used to assess liver fibrosis regression after antiviral treatment using nucleos(t)ide analogs in patients with CHB.

Keywords: Alanine aminotransferase, Chronic hepatitis B, Liver fibrosis, Liver stiffness measurement, Nucleos(t)ide analog, Transient elastography

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a chronic inflammatory condition that results in the formation of fibrous tissue and may lead to architectural distortion and persistent damage of the liver. Until recently, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis were generally considered to be irreversible [1, 2]. However, several studies using serial liver biopsies (LBs) have reported that several therapeutic interventions can produce histological improvement, including liver fibrosis regression [3–7]. Among these therapeutic interventions, nucleos(t)ide analogs that suppress hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication eliminated HBV DNA in 30–70% of cases and were significantly associated with liver fibrosis regression by reducing liver inflammation and cellular damage [8–11].

Because the prognosis and management of patients with CHB, as well as other chronic liver diseases (CLDs), depend strongly on the degree of liver fibrosis, the assessment of liver fibrosis regression is helpful to clinicians [12]. However, follow-up LB for confirming liver fibrosis regression during or after antiviral treatment is troublesome except consenting subjects. Therefore, a non-invasive method to assess liver fibrosis regression in patients with CHB who have undergone antiviral treatment would be highly useful.

Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) using FibroScan® allows the accurate assessment of liver fibrosis in patients with CHB and chronic hepatitis C (CHC) [13–15]. Although there have been several longitudinal investigations of patients with CHC [16–18], no longitudinal follow-up study has examined patients with CHB receiving antiviral treatment. Therefore, aims of our study were to evaluate whether LSM, rather than LB, can be used to assess changes in liver fibrosis during antiviral treatment using nucleos(t)ide analogs in patients with CHB and to compare the performance of LSM and other non-invasive methods in assessing liver fibrosis regression.

Patients and methods

Patients

In this retrospective cohort study, all data were collected from the database of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. Between January and August 2007, we recruited 41 patients with CHB who showed significant liver fibrosis (≥stage F2 according to the METAVIR scoring system) on LB, normal or slightly elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels [<2 × upper limit of normal (ULN)], detectable serum HBV DNA by hybridization capture assay before antiviral treatment [19], and no ALT fluctuation (≥2 × ULN) during antiviral treatment. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki declaration and was approved by our independent institutional review board.

Patients with other CLDs, such as liver cancer, co-infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), or human immunodeficiency virus and those with co-morbidities associated with HBV, such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or primary biliary cirrhosis, were excluded. Patients with a history of alcohol ingestion over 40 g/day for more than 5 years, previous liver resection surgery, liver transplantation, or evidence of cardiac or renal failure (defined as a serum creatinine levels ≥1.5 mg/dL) were also excluded. Patients with an unreliable LSM [<10 successful acquisitions, a success rate <60%, an interquartile range (IQR) over median ratio lower than 30%, or measurement on a different day from LB; n = 4] or an unsuitable LB for fibrosis staging (<15 mm or 6 portal tracts; n = 2) were also excluded.

From the medical records, we collected data on age, gender, body mass index, liver histology and LSM values. The following laboratory parameters were also examined in all patients at the time of LB and LSM: ALT, total bilirubin, serum albumin, platelet count and prothrombin time (international normalized ratio). Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HBeAg and antibodies were measured using standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA). HBV DNA levels were measured using a hybridization capture assay (Digene Diagnostics, Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Patients in Group 1 (n = 23) and Group 2 (n = 18) underwent follow-up LSM and LB (optional) after antiviral treatment for 1 and 2 years, respectively. The mean interval from the starting day of antiviral treatment to follow-up LSM and LB was 12.2 ± 1.2 months in Group 1 and 24.4 ± 0.8 months in Group 2. Nucleos(t)ide analogs used for antiviral treatment included lamivudine (n = 16; 11 patients in Group 1 and 5 in Group 2), adefovir (n = 10; 5 in each group) and entecavir (n = 15; 7 in Group 1 and 8 in Group 2). The selection of a nucleos(t)ide analog was made after considering the availability of national insurance coverage for the antiviral agent, patient demand, or the decision of the attending clinician. The mean duration from the day of baseline LSM to the start of antiviral treatment was 5.7 ± 2.4 days.

Liver stiffness measurement

Liver stiffness measurement using FibroScan® was performed according to previously described methods [20, 21]. Briefly, an ultrasound transducer probe is mounted on the axis of a vibrator. Vibrations of mild amplitude (1 mm) and low frequency (50 Hz) are transmitted by the transducer, inducing an elastic shear wave that propagates through underlying tissues. Pulse-echo ultrasound acquisitions are used to follow the propagation of the shear wave and to measure its velocity, which is directly related to tissue stiffness (the elastic modulus): the stiffer the tissue, the faster the shear wave propagates. LSM measures liver stiffness in a volume that approximates a cylinder of 1-cm wide and 4-cm long, 25–65 mm below the skin surface. This volume is at least 100 times larger than that of a biopsy sample and is, therefore, far more representative of the hepatic parenchyma.

Ten valid measurements were performed on each patient. The success rate was calculated as the number of valid measurements divided by the total number of measurements. The results were expressed in kilopascals (kPa). IQR was defined as an index of intrinsic variability of LSM corresponding to the interval around LSM result containing 50% of the valid measurements between the 25th and 75th percentiles. The median value was considered representative of the elastic modulus of the liver. Only procedures with ten valid measurements, a success rate of at least 60% and an IQR over median ratio lower than 30% were considered reliable.

Other non-invasive methods of assessing liver fibrosis

The age–platelet index (API), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI) and age–spleen–platelet ratio index (ASPRI) were also evaluated for comparison with LSM results. The API, ARPI and ASPRI were calculated according to Poynard, Wai and Kim et al., respectively (Table 1) [22–24]. ALT level was measured using an automated chemistry analyzer (Hitachii 7600, Tokyo, Japan). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the ULN for ALT was determined to be 40 IU/L.

Table 1.

Calculation method of noninvasive model

| Models | Calculation method |

|---|---|

| API | Age (years): <30 = 0, 30–39 = 1, 40–49 = 2, 50–59 = 3, 60–69 = 4, ≥70 = 5 |

| Platelet count (109 L−1): ≥225 = 0, 200–224 = 1, 175–199 = 2, 150–174 = 3;125–149 = 4, <125 = 5 | |

| API is the sum of the above (possible value 0–10) | |

| APRI | [(AST/ULN)/platelet count (109 L−1)] × 100 |

| SPRI | Spleen size (cm)/platelet count (109 L−1) × 100 |

| ASPRI | Age (years): <30 = 0, 30–39 = 1, 40–49 = 2, 50–59 = 3, 60–69 = 4, ≥70 = 5 |

| ASPRI is the sum of age and SPRI |

Evaluation of liver histology

The indications for LB included an assessment of the severity of liver fibrosis and inflammation before antiviral treatment. LB was performed twice using 16-gauze gun biopsy sheathed cutting needle (spring loaded) (TSK Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan) on the right lobe of the liver under local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance. LB specimens were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. 4-μm-thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome. All liver tissue samples were evaluated by an experienced hepatopathologist (YN Park) who was blinded to the patients’ clinical histories.

Liver histology was evaluated according to the METAVIR scoring system [25]. Fibrosis was staged on the following scale of 0–4: F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis without septa; F2, portal fibrosis and a few septa; F3, numerous septa without cirrhosis; and F4, cirrhosis. The mean length of the liver samples before antiviral treatment was 18.5 ± 1.6 mm.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The independent t test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the baseline characteristics of Groups 1 and 2. The paired sample t test and McNemar test were used to compare the values pre- and post-antiviral treatment in each patient and to identify variables that showed a significant change during antiviral treatment. Two-way analysis of variance test was performed to identify the effects of each antiviral agent on the changes in LSM value during the antiviral treatment. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline clinical and histological characteristics of all patients at the time of LSM and LB are shown in Table 2. The mean age, ALT level and LSM value of all patients (34 men and 7 women) before antiviral treatment were 46.6 ± 9.5 years, 40.6 ± 17.2 IU/L and 12.9 ± 8.6 kPa, respectively. HBV DNA was detectable in all patients using a hybridization capture assay, and HBeAg was detected in 31 patients (75.6%) before antiviral treatment. The fibrosis stage was F2 in 12 (29.3%), F3 in 6 (14.6%) and F4 in 23 (56.1%) patients. There were no significantly different variables between Groups 1 and 2. Among variables, only fibrosis stage was significantly correlated to LSM values before antiviral treatment (Spearman correlation coefficient, r = 0.576 and P = 0.041, data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics at the time of LSM and LB

| Variables | Total | Group 1 | Group 2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 41) | (n = 23) | (n = 18) | ||

| Male gender | 34 (82.9) | 19 (82.6) | 15 (83.3) | NS |

| Age (years) | 46.6 ± 9.5 | 45.9 ± 11.4 | 47.6 ± 6.5 | NS |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 2.5 | 23.7 ± 2.3 | 23.6 ± 2.8 | NS |

| Platelet count (109 L−1) | 171 ± 52 | 170 ± 55 | 172 ± 51 | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 0.072 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 40.6 ± 17.2 | 39.7 ± 15.0 | 41.9 ± 20.2 | NS |

| HBeAg positivity | 31 (75.6) | 15 (65.2) | 16 (88.9) | NS |

| HBV DNA positivity | 41 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | NS |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.02 ± 0.09 | 1.03 ± 0.08 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | NS |

| Fibrosis at initial biopsy | ||||

| F2 | 12 (29.3) | 5 (21.7) | 7 (38.9) | NS |

| F3 | 6 (14.6) | 3 (13.1) | 3 (16.7) | |

| F4 | 23 (56.1) | 15 (65.2) | 8 (44.4) | |

| LSM value (kPa) | 12.9 ± 8.6 | 13.7 ± 8.0 | 12.1 ± 9.6 | NS |

| Interquartile range (kPa) | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | NS |

| Success rate (%) | 97.4 ± 6.7 | 97.0 ± 8.4 | 98 ± 3.9 | NS |

Comparison between the values at pre- and post-antiviral treatment

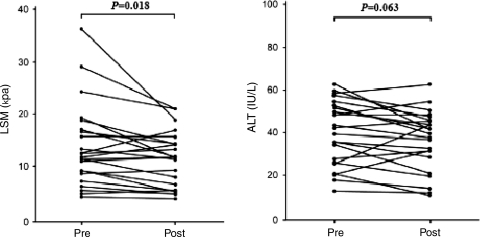

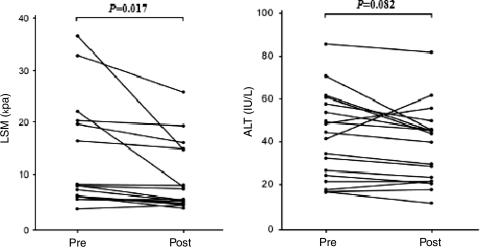

Pre- and post-antiviral treatment laboratory findings, LSM values and several non-invasive models for assessing liver fibrosis are summarized in Table 3. LSM values and HBV DNA positivity decreased significantly after antiviral treatment compared to baseline (P = 0.018 and P < 0.001 in Group 1; P = 0.017 and P < 0.001 in Group 2, respectively), whereas ALT levels were unchanged (P = 0.063 in Group 1, P = 0.082 in Group 2, respectively). The API, APRI and ASPRI also failed to show a significant difference between pre- and post-antiviral treatment values. Variations in LSM value and ALT level are shown in Figs. 1 (Group 1) and 2 (Group 2).

Table 3.

Comparison between pre- and post-antiviral treatment

| Group 1 (n = 23) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | P value | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 2.3 | 23.5 ± 2.2 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 39.6 ± 15.0 | 35.9 ± 14.0 | 0.063 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.85 ± 0.3 | NS |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 1.03 ± 0.06 | NS |

| Platelet count (109 L−1) | 171 ± 20 | 173 ± 24 | NS |

| LSM value (kPa) | 13.7 ± 7.9 | 11.3 ± 5.3 | 0.018 |

| 11.7 (4.1–36.3) | 11.8 (3.8–20.9) | ||

| HBV DNA positivity | 23 (100) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| HBeAg positivity | 15 (65.2) | 15 (65.2) | NS |

| API | 4.69 ± 2.26 | 4.55 ± 1.89 | NS |

| APRI | 0.85 ± 0.73 | 0.83 ± 0.80 | NS |

| ASPRI | 8.82 ± 3.74 | 8.80 ± 2.96 | NS |

Fig. 1.

Variation in LSM values and ALT levels between pre- and post-antiviral treatment in patients with CHB who underwent follow-up LSM after 1 year of antiviral treatment using nucleos(t)ide analogs (Group 1). LSM liver stiffness measurement, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LB liver biopsy

Fig. 2.

Variation in LSM values and ALT levels between pre- and post-antiviral treatment in patients with CHB who underwent follow-up LSM after 2 year of antiviral treatment using nucleos(t)ide analogs (Group 2). LSM liver stiffness measurement, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LB liver biopsy

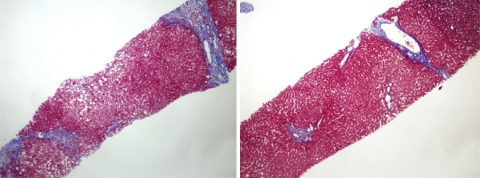

Details of Group 2 patients who underwent follow-up LB

Follow-up LB was performed in four patients (nos. 8, 10, 12 and 13) in Group 2 (Table 4). ALT levels and LSM values tended to decrease, all patients were HBV DNA negative and one patient (no. 12) showed HBeAg seroconversion after antiviral treatment. Three patients (nos. 8, 10 and 13) showed liver fibrosis regression from F3 to F2 or from F2 to F1, whereas one patient (no. 12) showed no change in fibrosis stage. However, patient no. 12 showed slightly decreased portal fibrosis within the same fibrosis stage (F2) as compared to baseline LB. Figure 3 shows histological changes of patient no. 8 after 2 years of antiviral treatment.

Table 4.

Laboratory and histologic findings of four patients in Group 2 who underwent follow-up liver biopsy

| Patient #8 | Patient #10 | Patient #12 | Patient #13 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Antiviral agent | Entecavir | Entecavir | Entecavir | Lamivudine | ||||

| ALT (IU/L) | 32 | 17 | 57 | 65 | 26 | 25 | 60 | 56 |

| HBV DNA (pg/mL) | 3.2 | <0.5 | 13.3 | <0.5 | 3.4 | <0.5 | 23.3 | <0.5 |

| HBeAg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | Pos |

| Platelet count (109 L−1) | 187 | 190 | 236 | 220 | 221 | 200 | 231 | 220 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.92 |

| API | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| APRI | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.48 |

| ASPRI | 8.42 | 9.40 | 6.39 | 6.30 | 6.85 | 6.80 | 5.68 | 6.48 |

| LSM value (kPa) | 7.9 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 6.2 |

| Fibrosis grade | F3 | F2 | F2 | F1 | F2 | F2 | F2 | F1 |

Fig. 3.

Regression of liver fibrosis from stage F3–F2 in patient no. 8. Left septal collagenous fibrosis of moderate thickness is present before antiviral treatment. Right almost all of the portal tracts reveal periportal fibrosis with occasional long slender fibrosis only (incipient septa) after 2 years of antiviral treatment (elastic trichrome, original magnification ×40)

Discussion

Because the degree of liver fibrosis determines prognosis and treatment strategy for patients with CHB and CHC [12], liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment can provide additional information.

Liver biopsy has been the ‘gold standard’ for assessing liver fibrosis, and is frequently performed as a baseline evaluation of liver fibrosis before antiviral treatment [26]. However, LB is rarely performed to confirm liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment, except in a few studies that investigated liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment using serial LBs [27, 28]. Therefore, a non-invasive method to assess liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment would enable clinicians to re-evaluate prognoses and treatment strategies or to conduct comparative studies on the efficacy of antiviral agents.

Currently, several simple non-invasive serologic models for predicting liver fibrosis are available [22–24]. However, the ability of these models to predict liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment has not been investigated. According to our results, the available simple non-invasive serologic markers do not appear to be useful in detecting liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment when compared with LSM. This result can be explained in part by the confounding effects of extra-hepatic conditions and the superior performance to predict liver fibrosis of LSM has been confirmed in previous studies [20, 29]. Because other markers, such as hyaluronic acid and type IV collagen were not available in this retrospective study, further studies with theses markers will be needed.

Recently, LSM has been accepted as a non-invasive tool for assessing liver fibrosis. However, most investigations of LSM conducted a one-time analysis using demographic and laboratory data obtained at the time of LB. Therefore, there is a chance that the dynamic changes in the biochemical tests before and after LB, especially ALT level, were not incorporated in the analysis. Several recent studies addressed this limitation by acquiring serial LSM values and concluded that ALT level has a significant impact on LSM [30–33]. Therefore, it has become more evident that LSM can be influenced by high ALT levels. Accordingly, a more recent study conducted in Hong Kong suggested that ALT level should be incorporated into the algorithms for diagnostic and treatment strategies in patients with CHB [34]. Therefore, failure to consider ALT levels may lead to less reliable or confusing results.

Among those who showed detectable HBV DNA in the hybridization capture assay and persistently normal or slightly elevated serum ALT levels (<2 × ULN), a large proportion had significant histology on LB examination, which is an indication for antiviral treatment in South Korea [29, 35]. Recruiting these patients enabled us to exclude the confounding effects of high ALT levels and specifically examine the performance of LSM in assessing liver fibrosis regression during antiviral treatment [30–33].

Several teams have investigated dynamic changes in LSM values during antiviral treatment in patients with CHC who had achieved SVR. However, there is no published longitudinal study for patients with CHB. De Ledinghen et al. [16] evaluated liver fibrosis regression using LSM and FibroTest in a very long-term follow-up of HCV responders and concluded that LSM and FibroTest are useful tools for the non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis and monitoring the histological response after antiviral treatment in HCV patients. Hezoda et al. [17] reported that LSM value was significantly, but modestly, reduced at the end of follow-up in patients with CHC who achieved SVR in response to peginterferon and alpha-ribavirin combination treatment. Colletao et al. [18] also investigated liver fibrosis among long-term responders (patients with CHC and CHB) to antiviral treatment, and concluded that LSM may reliably substitute for LB to confirm liver fibrosis regression. More recent study investigated the changes of LSM values during HCV treatment and concluded that irrespective of the virological response, treatment for HCV infection is associated with an improvement of LSM values [36].

In this study, we controlled the confounding effects of high ALT levels by recruiting patients with CHB showing persistently normal or minimally elevated ALT levels before antiviral treatment and persistent viral suppression after antiviral treatment. The reduction in ALT levels after antiviral treatment failed to show statistical significance (P = 0.063 in Group 1 and P = 0.082 in Group 2), whereas the reduction in LSM values predicted liver fibrosis regression significantly. These results were consistent when our study population was analyzed altogether considering small sample size (ALT, P = 0.068 and LSM, P = 0.010, data not shown). Furthermore, three patients (nos. 8, 10 and 13) in the 2 years of antiviral treatment group (Group 2) underwent optional LB; data from these procedures were used to confirm the performance of LSM in predicting liver fibrosis regression. A previous study reported that cirrhotic nodules appear to enlarge by expansion against septa as well as by lysis of septa and nodules surrounded by thin septa coalesce first, giving rise to macronodules or large regenerative nodules [3]. Accordingly, decreased LSM value after antiviral treatment in our current study implied fibrosis regression by virtue of lowered volume of total fibrosis in liver after long-term antiviral treatment.

Extrapolating our results, we might be able to consider LSM value at the time at which ALT level falls below 2 × ULN after antiviral treatment as a baseline and use this value to predict subsequent liver fibrosis regression in patients with high ALT levels (≥2 × ULN) before antiviral treatment. We previously showed that LSM values required additional time to normalize even after ALT levels had normalized in patients with acute hepatitis [37]. Therefore, if the interval between the decline in ALT level (to <2 × ULN) and the stabilization of LSM value can be validated in future investigations [38], LSM could also be used to predict liver fibrosis regression in patients with high ALT levels (≥2 × ULN) before antiviral treatment.

An additional analysis to investigate the changes in ALT levels and LSM values according to each antiviral agent showed that ALT level did not change significantly in responses to any of the examined antiviral agents (P = 0.186 for lamivudine, P = 0.129 for adefovir and P = 0.260 for entecavir), whereas LSM decreased significantly in patients receiving adefovir and entecavir, but not lamivudine (P = 0.026, P = 0.014 and P = 0.101, respectively; data not shown). In addition, no significant difference was observed regarding the effects of each antiviral agent and HBeAg status on LSM value after antiviral treatment (all not significant; data not shown).

We are aware of several limitations in our study. First, sample size was small and there is no control group (i.e. no antiviral treatment), which is required to compare the change in LSM values from baseline to follow-up. Second, follow-up LB data are necessary for an exact comparison with follow-up LSM and original LB. However, follow-up LB was optional in this retrospective study and data were finally obtained for only four patients from Group 2. Third, we only recruited patients showing normal or slightly elevated ALT before antiviral treatment and no ALT fluctuation during antiviral treatment. Therefore, the clinical usefulness of LSM should be validated by further investigations which enroll patients with high ALT before antiviral treatment and those with fluctuating ALT during antiviral treatment and perform paired LB after long-term antiviral treatment.

In conclusion, our preliminary data showed that antiviral treatment in patients with CHB was associated with a decrease in LSM values and suggest that LSM might be used to assess liver fibrosis regression after antiviral treatment using nucleos(t)ide analogs in patients with CHB who demonstrate ALT levels <2 × ULN before antiviral treatment and persistent viral suppression during the course of antiviral treatment. However, large-scaled randomized prospective study with full paired LB and long-term follow-up will be needed in the near future to validate our conclusions.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Grant of the Good Health R&D Project from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A050021), and in part by Brain Korea 21 Project for Medical Science. The authors wish to thank Joon Seong Kim, Ji Won Kim and Jeong Min Cho for their critical comments and support.

Abbreviations

- LB

Liver biopsy

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- CHB

Chronic hepatitis B

- CHC

Chronic hepatitis C

- CLD

Chronic liver disease

- LSM

Liver stiffness measurement

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ULN

Upper limit of normal

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBeAg

Hepatitis B e antigen

- kPa

Kilopascals

- IQR

Interquartile range

- API

Age–platelet count index

- APRI

Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index

- ASPRI

Age–spleen–platelet ratio index

- SVR

Sustained viral response

References

- 1.Benyon RC, Iredale JP. Is liver fibrosis reversible? Gut. 2000;46:443–446. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonis PA, Friedman SL, Kaplan MM. Is liver fibrosis reversible? N Engl J Med. 2000;344:452–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wanless IR, Nakashima E, Sherman M. Regression of human cirrhosis. Morphologic features and the genesis of incomplete septal cirrhosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1599–1607. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1599-ROHC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan MM, DeLellis RA, Wolfe HJ. Sustained biochemical and histologic remission of primary biliary cirrhosis in response to medical treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:981–985. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-9-199705010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammel P, Couvelard A, O’Toole D, Ratouis A, Sauvanet A, Flejou JF, et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med. 2000;344:418–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiratori Y, Lmazeki F, Moriyama M, Yano M, Arakawa Y, Yokosuka O, et al. Histologic improvement of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C who have sustained response to interferon treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:517–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, Trepo C, Lindsay K, Goodman Z, et al. Impact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1303–1313. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NWY, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, Perrillo RP, Hann HWL, Goodman Z, et al. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1256–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schalm SW, Heathcote J, Cianciara J, Farrell G, Sherman M, Willems B, et al. Lamivudine and alpha-interferon combination treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: a randomised trial. Gut. 2000;46:562–568. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dienstag JL, Goldin RD, Heathcote EJ, Hann HW, Woessner M, Stephenson SL, et al. Histological outcome during long-term lamivudine treatment. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:105–117. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright TL. Introduction to chronic hepatitis B infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(Suppl 1):S1–S6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraquelli M, Rigamonti C, Casazza G, Conte D, Donato MF, Ronchi G, et al. Reproducibility of transient elastography in the evaluation of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 2007;56:968–973. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganne-Carrié N, Ziol M, Ledinghen V, Douvin C, Marcellin P, Castera L, et al. Accuracy of liver stiffness measurement for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with chronic liver diseases. Hepatology. 2006;44:1511–1517. doi: 10.1002/hep.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, et al. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledinghen V, Foucher J, Castera L, Bernard PH, Salzmann M, Moisset G, et al. Evaluation of fibrosis regression using non-invasive methods in very long-term follow-up of HCV responder patients. Hepatology. 2006;44(Suppl 1):317A. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hezoda C, Castera L, Rosa I, Roulot D, Leroy V, Bouvier-Alias M, et al. Dynamics of liver stiffness during peginterferon alpha-ribavirin treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46(Suppl 1):366–367. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colleta C, Smirne C, Fabris C, Foscolo AM, Toniutto P, Rapetti R, et al. Regression of fibrosis among long-term responders to antiviral treatment for chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 2007;46(Suppl 1):300–301. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DY, Kim SU, Ahn SH, Park JY, Lee JM, Park YN, et al. Usefulness of FibroScan for detection of early compensated liver cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1758–1763. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SU, Ahn SH, Park JY, Kang W, Kim DY, Park YN, et al. Liver stiffness measurement in combination with non-invasive markers for the improved diagnosis of B-viral liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:267–271. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31816f212e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poynard T, Bedossa P. Age and platelet count: a simple index for predicting the presence of histological lesions in patients with antibodies to hepatitis C virus. METAVIR and CLINIVIR Cooperative Study Groups. J Viral Hepat. 1997;4:199–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim BK, Kim SA, Park YN, Cheong JY, Kim HS, Park JY, et al. Noninvasive models to predict liver cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2007;27:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349:825–832. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiff E, Simsek H, Lee WM, Chao YC, Sette H, Jr, Janssen HL, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2776–2783. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kweon YO, Goodman ZD, Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Brown NA, Burchardt E, et al. Decreasing fibrogenesis: an immunohistochemical study of paired liver biopsies following lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2001;35:749–755. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(01)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers RP, Tainturier MH, Ratziu V, Piton A, Thibault V, Imbert-Bismut F, et al. Prediction of liver histological lesions with biochemical markers in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2003;39:222–230. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(03)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arena U, Vizzutti F, Corti G, Ambu S, Stasi C, Bresci S, et al. Acute viral hepatitis increases liver stiffness values measured by transient elastography. Hepatology. 2007;47:380–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coco B, Oliveri F, Maina AM, Ciccorossi P, Sacco R, Colombatto P, et al. Transient elastography: a new surrogate marker of liver fibrosis influenced by major changes of transaminases. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:360–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sagir A, Erhardt A, Schmitt M, Häussinger D. Transient elastography is unreliable for detection of cirrhosis in patients with acute liver damage. Hepatology. 2008;47:592–595. doi: 10.1002/hep.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SU, Kim DY, Park JY, Lee JH, Ahn SH, Kim JK, et al. How can we enhance the performance of liver stiffness measurement using FibroScan® in diagnosing liver cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Chan HL, Wong GL, Choi PC, Chan AW, Chim AM, Yiu KK, et al. Alanine aminotransferase-based algorithms of liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography (Fibroscan) for liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park JY, Park YN, Kim DY, Paik YH, Lee KS, Moon BS, et al. High prevalence of significant histology in asymptomatic chronic hepatitis B patients with genotype C and high serum HBV DNA levels. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:615–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vergniol J, Foucher J, Castéra L, Bernard PH, Tournan R, Terrebonne E, et al. Changes of non-invasive markers and FibroScan values during HCV treatment. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han Kim SU, KH Park JY, Ahn SH, Chung MJ, Chon CY, et al. Liver stiffness measurement using FibroScan is influenced by serum total bilirubin in acute hepatitis. Liver Int. 2009;29:810–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong GL, Wong VW, Choi PC, Chan AW, Chim AM, Yiu KK, et al. Increased liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography in severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1002–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]