Abstract

The Cu(I) chaperone Cox11 is required for the insertion of CuB into cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) of mitochondria and many bacteria, including Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Exploration of the copper binding stoichiometry of R. sphaeroides Cox11 led to the finding that an apparent tetramer of both mitochondrial and bacterial Cox11 binds more copper than the sum of the dimers, providing another example of the flexibility of copper binding by Cu(I)-S clusters. Site-directed mutagenesis has been used to identify components of Cox11 that are not required for copper binding but are absolutely required for the assembly of CuB, including conserved Cys-35 and Lys-123. In contrast to earlier proposals, Cys-35 is not required for dimerization of Cox11 or for copper binding. These findings, plus the location of Cys-35 at the C terminus of the predicted transmembrane helix and thereby close to the surface of the membrane, allows a proposal that Cys-35 is involved in the transfer of copper from the Cu(I) cluster of Cox11 to the CuB ligands His-333/334 during the folding of CcO subunit I. Lys-123 is located near the Cu(I) cluster of Cox11, in an area otherwise devoid of charged residues. From the analysis of several Cox11 mutants, including K123E, L and R, we conclude that a previous proposal that Lys-123 provides charge balance for the stabilization of the Cu(I) cluster is unlikely to account for its absolute requirement for Cox11 function. Rather, consideration of the properties of Lys-123 and the apparent specificity of Cox11 suggests that Lys-123 plays a role in the interaction of Cox11 with its target.

The aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is the terminal member of the respiratory electron transfer system in mitochondria and many aerobic bacteria (1, 2). The CcO complex contains two separate copper centers, CuA in subunit II and CuB in subunit I. The CuA center contains two copper ions, liganded by two bridging cysteines plus two histidines, one carboxyl side chain and one backbone carbonyl oxygen (3-5). CuB is a component of the O2 reduction site in subunit I, along with heme a3 and a cross-linked His-Tyr cofactor (4-6). The single copper of CuB is liganded by three histidines of subunit I, two of which are adjacent (His-333 and His-334). The third ligand is the histidine of the His-Tyr cofactor. The structure of the CuB center is highly conserved throughout the large heme-Cu oxidase superfamily (7). The structure of the CuA center is also conserved, but this center is only present in certain groups of the heme-Cu oxidases.

In bacteria, a CcO subcomplex containing only subunits I and II is readily produced (8, 9). In this fully-folded and active I-II oxidase form, all of the redox centers, CuA, heme a and the heme a3-CuB center, are buried within the protein and inaccessible to solvent (10). The structure and stability of this complex predicts that all of the redox centers are assembled during the folding of these subunits in the membrane and prior to the association of subunit II with subunit I.

The α-proteobacter Rhodobacter sphaeroides expresses a CcO with high similarity to the catalytic core of mitochondrial CcO, including subunits I and II (11, 12). As an extant relative of the bacterium from which mitochondria arose, R. sphaeroides also expresses homologs of several proteins that function to assemble CcO metal centers in mitochondria. R. sphaeroides has proved useful in elucidating the function of two of these assembly factors, Cox11 and Surf1, due to the ability of the bacterial cell to accumulate partially assembled CcO forms suitable for biochemical analysis (13, 14).

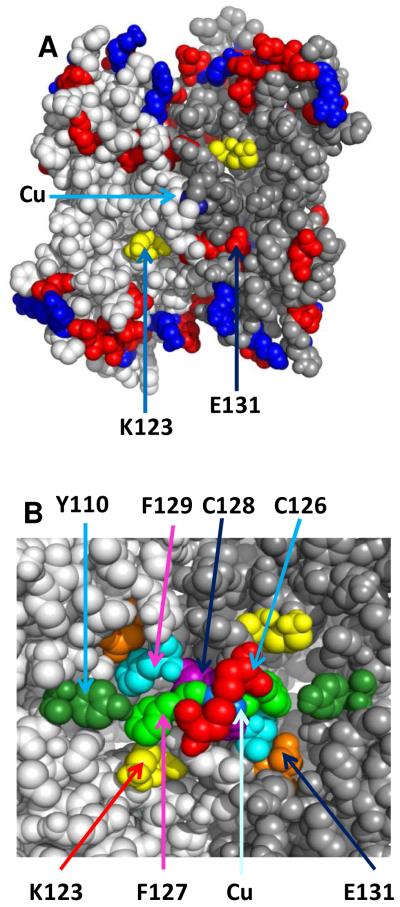

Cox11 was originally identified as necessary for CcO assembly in yeast mitochondria (15) and shown to be required for the assembly of CuB by the production of a CcO complex lacking CuB in a strain of R. sphaeroides where the gene for Cox11 was deleted (13). Subsequently, mitochondrial Cox11 was shown to bind Cu(I) (16) and the solution structure of the extramembrane domain of a bacterial Cox11 was obtained (17). Each monomer of Cox11 is anchored in the membrane by a single transmembrane helix, while the extramembrane domain containing the copper-binding residues is located in the inter-membrane space of mitochondria or the periplasmic space of bacteria (18). X-ray spectroscopy of mitochondrial and bacterial Cox11, plus other analyses, led to the finding that a dimer of Cox11 binds two Cu(I) in a cluster where each copper makes three Cu-S bonds (16, 17). In the currently accepted model of the Cu(I) cluster (17) each monomer contributes two cysteines from a CFCF sequence conserved throughout the Cox11 family. In order to produce structural models of the Cox11 dimer that include the Cu(I) cluster, van Dijk et al (19) used computer protein docking methods. Successful models of the dimer require the two monomers to lie anti-parallel to each other, a condition that points the Cu(I) cluster toward the surface of the membrane. Another structural feature of the dimer, which can also be seen in the monomer, is a marked asymmetry in the polarity of the protein surface (Fig. 1). A neutral belt lacking charged residues, and ~17Å wide, runs around the equator of the dimer. The 4 Cys – 2 Cu(I) cluster is located in the center of this belt. The only charged groups located in this region is a pair of conserved lysine residues, Lys-123 of each monomer (R. sphaeroides numbering). Each end of the Cox11 dimer contains numerous charged groups on the surface, as typical for aqueous, globular proteins.

Figure 1.

Predicted structure of the dimer form of the Cox11p extramembrane domain from Model 5, Cluster 2 of van Dijk et al (19). Panel A. The antiparallel monomers of the dimer are shown in light gray and dark gray. Basic residues are colored blue and acidic residues red. Within the wide neutral zone lie the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster (coppers in cyan) and the two Lys-123 residues of the dimer (yellow). Conserved Glu-131 lies on the border of the neutral band. Panel B. Residues that are the focus of this study are shown, except for Cys-35 which lies in an unresolved N-terminal region of Cox11 (17), close to the C-terminal end of the transmembrane helix of Cox11.

The process of copper transfer from Cox11 to the CuB site in subunit I is difficult to study directly since the event likely occurs during the folding of subunit I (20, 21). Two studies in yeast have used site-directed mutagenesis to deduce aspects of Cox11 function in vivo. Carr and Winge (16) showed that the cysteines of the CFCF motif were, in fact, required for copper binding and for Cox11 function in vivo. A third conserved cysteine, Cys-35 in R. sphaeroides Cox11, was also implicated in copper binding and found to be required for Cox11 function in vivo. Banting and Glerum (22) performed more extensive mutagenic analysis of yeast Cox11, including the demonstration that substituting glutamates for the conserved lysines in the neutral zone close to the Cu(I) cluster eliminated Cox11 function. These lysines have been proposed to provide charge balance for the formation of the Cu(I) cluster (17, 19). However, the effect of the Lys-123 mutations on the binding of copper by Cox11 has remained undetermined.

Here, we have used site-directed mutagenesis to alter the CFCF motif, Cys-35 and residues of the neutral zone of Cox11, including Lys-123, in R. sphaeroides. The same set of mutations has been introduced into a soluble form of Cox11 to assess their effect on copper binding and into native Cox11 in R. sphaeroides to assess their effect on CuB assembly. Purification of the soluble form of Cox11 has been designed to minimize adventitious copper but avoid the loss of specifically-bound copper by over-purification. The experiments are the first to identify components of Cox11 that are not required for copper binding but are required for the assembly of CuB, including Cys-35 and Lys-123. The new results lead us to propose a role for Cys-35 in copper transfer and a role for Lys-123 in target recognition.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression of a soluble form of Cox11

The expression plasmid for a fusion of the extramembrane domain of R. sphaeroides Cox11 and E. coli thioredoxin (Cox11-Trx) was constructed as follows A fragment of R. sphaeroides cox11 encoding residues 32 through 191 was amplified from R. sphaeroides genomic DNA by PCR. Restriction sites for Bam HI and Xho I were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends during the amplification. The resulting 480-bp fragment was sub-cloned in pET32a (Novagen), thereby creating pHC100 for the expression of a soluble protein with a predicted molecular weight of 35.3 kD. Starting from the N-terminus, the expressed protein contains E. coli thioredoxin (trxA; 109 amino acids), a 56 amino acid linker region that includes a six-histidine tag and residues 32-191 of R. sphaeroides Cox11, its entire extramembrane domain. Mutagenesis of Cox11-Trx was performed in pHC100 using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis system (Stratagene).

Mutagenesis of the gene expressing full-length, native Cox11 in R. sphaeroides was performed using pRKpAH1H32, a plasmid that contains the genes for his-tagged subunit I (coxI6Xhis), subunit II (coxII), Heme O synthase (cox10), Cox11 (cox11) and subunit III (coxIII) (23). Mutagenesis was performed by the QuikChange system. The altered versions of pRKpAH1H32 were sequenced to verify that there were no other mutations elsewhere in the vector and the modified plasmids were conjugated into YZ200, a strain of R. sphaeroides in which the coxII/III operon that contains cox11 has been deleted (24). In this way, the only gene for Cox11 in the cell is that in the expression plasmid.

Expression and Purification of Cox11-Trx

Two liter flasks containing 600 ml of LB media plus 100 μg/ml ampicillin were inoculated with 1 mL of an overnight culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pHC100 or variants of pHC100 encoding mutant Cox11-Trx. The flasks were shaken at 250 rpm at 37°C until an OD600 of 0.6-0.9 was achieved, whereupon Cox11-Trx expression was induced by adding IPTG to 0.3 mM and the incubation temperature was decreased to 30°C. Thirty minutes after IPTG induction, CuSO4 was added to a final concentration of 1.4 mM and shaking was continued for a further 2.5 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000 X g for 15 min at 4°C and the cell pellets were stored at −80°C.

For purification of Cox11-Trx, cell pellets were re-suspended in 25mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, 1 mM DTT, 300 mM KCl, 0.1% β-D-dodecyl maltoside, 50 μg/ml DNase I, 1 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1X Bacterial ProteaseArrest (G Biosciences). Cells were broken by two passages through a French pressure cell at 16,000 psi and the lysate was centrifuged at 100,000g for 45 minutes to pellet cell debris and membranes. The supernatant containing the cytoplasm was mixed with PrepEase Purification Resin (USB-Affymetrix) at an empirically determined ratio of 1 g of dry resin per 7 L of initial cell culture. The mixture was rotated end-over-end at 4°C for 30 min and then packed as a gravity flow column (~3 ml swollen resin) and washed with 10 column volumes of 25 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, 1 mM DTT, 300 mM KCl, 0.1% β-D-dodecyl maltoside. The fusion protein was eluted with 200 mM histidine in the same buffer, but with 50 mM KCl. Fractions containing protein by A280 were washed free of histidine and concentrated to a volume of 0.5 ml using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filtration device (10 kD cutoff; Millipore) in a buffer of 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, 1 mM DTT and 50 mM KCl.

The 0.5 ml sample was loaded onto a Superdex 200 10/300 GL size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl and 0.5 mM DTT on a BioLogic DuoFlow chromatography system (BioRad) and developed at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The column was calibrated with blue dextran (2000 kD), ferritin (669 kD), aldolase (158 kD), conalbumin (75 kD), ovalbumin (43 kD), carbonic anhydrase (29 kD), ribonuclease A (13.7 kD) and aprotinin (6.5 kD) using the same buffer and flow rate. Kav values (the pseudo partition coefficient) were calculated for the standards using the equation Kav = Ve – Vo/Vc – Vo where Ve is the elution volume at the peak maximum, Vo is the column void volume, and Vc is the geometric column volume (24 ml). A curve of Kav versus log molecular weight was used to determine the Mr values of Cox11-Trx forms.

Samples collected from the size exclusion column were prepared for elemental analysis by adding EDTA to 1 mM and then washing the samples in a centrifugal filtration device (10 kD cutoff) with 20 mM KH2PO4 or 20 mM Tris, pH 7.6 until the DTT and EDTA concentrations were calculated to be 0.01 μM or lower. The aqueous protein samples were injected into a Spectro Genesis inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) to simultaneously measure the concentrations of copper at 324.754 nm and sulfur at 180.731 nm. Each concentration was the average of three successive determinations. The element standards used to develop the regression lines were purchased from Inorganic Ventures. The concentration of Cox11-Trx was obtained by dividing the sulfur concentration by sum of cysteines and methionines in Cox11-Trx (14 for the wild-type protein). This method of using sulfur to measure protein concentration has been used for mitochondrial CcO to resolve difficult questions of copper content (25). We have proven the method by finding that it accurately measures the copper and iron content of R. sphaeroides CcO as well as the iron content of horse cytochrome c. Proteolytic cleavage of soluble Cox11 from E. coli thioredoxin was performed using biotinylated thrombin (Novagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following the removal of biotinylated thrombin with streptavidin agarose, the mixture containing thioredoxin plus soluble Cox11 was washed into 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl and 1 mM DTT using a centrifugal filtration device. PrepEase Resin was added to bind the thioredoxin domain by its histidine tag and after mixing the resin was packed into a small gravity column and washed with the same buffer. The column flow-through containing the Cox11 domain was treated a second time with PrepEase Resin to remove residual thioredoxin and then the Cox11 in the flow-through was concentrated using a centrifugal filtration device (10 kD).

CcO methods

The purification of normal and mutants forms of R. sphaeroides CcO was performed using established protocols (24), as was the examination of CcO by optical spectroscopy (26) and measurements of CcO activity by O2 consumption (23).

RESULTS

Purification of a soluble form of R. sphaeroides Cox11

Determination of the copper binding characteristics of wild-type and mutant forms of Cox11 by elemental analysis requires the production of milligram quantities of each protein. Our attempts to purify native Cox11 from the cytoplasmic membrane of R. sphaeroides by a histidine tag yielded only small amounts of protein and work by another group to express the extramembrane domain of R. sphaeroides Cox11 as an independent soluble protein in E. coli was likewise unsuccessful (17). On the other hand, a fusion protein of the extramembrane domain of yeast Cox11 with E. coli thioredoxin expresses to reasonable levels in the cytoplasm of E. coli and binds copper (16). Therefore, we prepared an equivalent fusion protein (Cox11-Trx) of the extramembrane domain of R. sphaeroides Cox11. The Cox11 domain of the fusion protein begins at residue 32 of Cox11, immediately after the predicted transmembrane helix of the native protein, and therefore contains the entire extramembrane domain normally present in the periplasm.

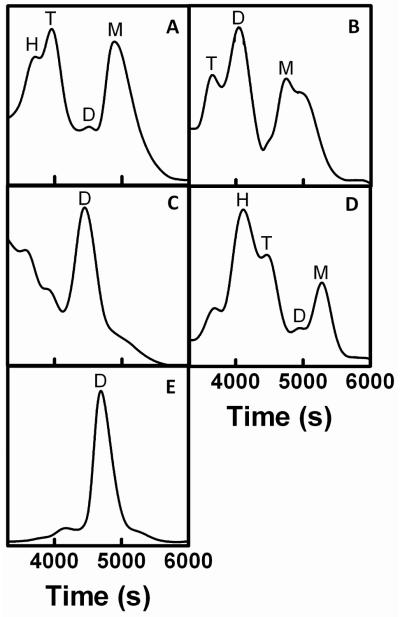

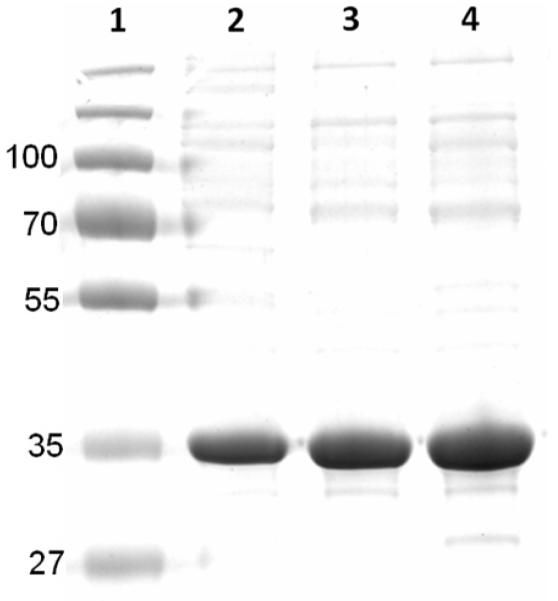

R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx is first purified via its six-histidine tag (Methods) with a yield of approximately 2 mg Cox11-Trx per L of cell culture and a purity ~ 75% based on Coomassie-stained protein gels (not shown). It has previously been established that the dimer of Cox11 binds copper (see Introduction) while the monomer binds little metal (16, 17). In order to obtain a copper-binding oligomer for metal analysis, the second purification step for R. sphaeroides Cox11 is size exclusion chromatography on Superdex 200 (Methods). SEC in the presence of DTT shows a variety of apparent oligomers (Fig 2A). Forms corresponding in size to monomer and tetramer are prominent, while the dimer peak is less populated (Fig. 2A). The tetramer peak represents about 10% of the total protein loaded onto the SEC column, therefore the yield of tetrameric Cox11-Trx is roughly 0.2 mg per L of cell culture. The Cox11-Trx present in the tetramer peak appears ~90% pure, based upon the analysis of over-loaded, Coomassie-stained protein gels (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Size-exclusion chromatography elution profiles of (A) wild-type Cox11-Trx, (B) yeast Cox11-Trx, (C) K123L-E131K Cox11-Trx, (D) the Cox11 domain after cleavage from Trx, and (E) the Trx domain alone. Chromatography on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column was performed as described in Methods. Peaks corresponding in mobility to monomer (M), dimer (D), tetramer (T) and hexamer (H) of the various proteins are labeled as necessary.

Figure 3.

A protein gel of soluble R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx from SEC fractions such as those shown in Fig. 3A. Protein from fractions corresponding in mobility to tetramer (lane 4), hexamer (lane 3) and higher order oligomers (lane 2) was electrophoresed on a 2% SDS-12% polyacrylamide reducing gel and stained with Coomassie Blue. Protein standards of the indicated sizes (kD) are in lane 1. The calculated size of R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx is 35.3 kD.

The thioredoxin domain alone, purified by the same methods, forms a dimer rather than a tetramer (Fig. 2E), suggesting that the formation of tetrameric Cox11-Trx is not solely driven by the self-association of the thioredoxin domain. In fact, removal of the thioredoxin domain by proteolytic cleavage before SEC shows that the Cox11 domain, independent of Trx, presents as a series of oligomers (Fig. 2D) similar in order to those of the entire fusion protein, including an apparent tetramer. This finding argues against the possibility that the peaks of Cox11-Trx with Mr values of tetramer and dimer arise from different conformers of a dimer with different hydrodynamic radii, e.g. linear Cox11-Trx with widely-separated Cox11 and Trx domains vs. a compact form where the two domains lie close together.

Because the similar Cox11-Trx fusion of yeast Cox11 was reported to purify mostly as a dimer (16), we explored the question of whether the presentation of R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx as mostly apparent tetramer was due to our purification method or to structural differences between yeast and R. sphaeroides Cox11. Purification of yeast Cox11-Trx by our methods shows that most of the yeast protein chromatographs with the size of a dimer, as shown previously (16), although a form corresponding in size to a tetramer is also present (Fig. 2B).

The R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx peak that elutes with the mobility of a tetramer was analyzed by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation in the presence of DTT to prevent aggregation through disulfides. Rather than showing a single species, analytical ultracentrifugation shows a heterogeneous mixture from 2-6 S indicating an array of Cox11-Trx oligomers. This experiment and others suggests that reduced, soluble Cox11-Trx tends to dissociate in relatively dilute solutions. In the absence of independent verification of the size of the protein in the tetramer and hexamer peaks of SEC, these forms will be denoted as ‘apparent’ tetramer and ‘apparent’ hexamer. The SEC peaks with the Mr values predicted for dimer and monomer are confirmed as these oligomers by their previously defined copper binding stoichiometries (see below). It should be noted that the goal of our Cox11-Trx purification is to obtain sufficient quantities of a single Cox11-Trx form suitable for determining if mutant versions of Cox11 bind copper. The principal conclusions of this study remain valid whether the Cox11-Trx form with the Mr of a tetramer actually is tetramer or whether it is a different oligomer with the mobility of tetramer on SEC.

Copper binding by wild-type Cox11 of R. sphaeroides and yeast

We have measured the copper concentration in various SEC peaks (Fig. 2A) of wild-type R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx and mutant forms using inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy. The concentration of protein is determined from the sulfur content in the same sample that is used to measure copper, and the copper content is expressed as the number of coppers per monomer. The monomer form of wild-type R. sphaeroides Cox11 binds only substoichiometric amounts of copper, from 0.2 to 0.5 copper per monomer in different preparations. Likewise, the monomer of Sinorhizobium meliotti Cox11 was found to bind little copper (17).

Previous analyses of the dimers of yeast Cox11-Trx (16) and Sinorhizobium Cox11 (17) showed a copper per monomer stoichiometry ~1. Independently, we have measured a stoichiometry of 1.12 copper per monomer for the dimer of yeast Cox11 (Fig. 2B), in agreement with the published values. Analysis of SEC fractions containing the apparent dimer of wild-type R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx (Fig. 2A) yields a value of 1.15 ± 0.11 copper per monomer (n=4). However, the fractions containing the apparent dimer form also contain significant amounts of tetramer or monomer due to the relatively low population of dimer (Fig. 2A). Hence, the most accurate statement of this analysis is that the copper per monomer stoichiometry of the dimer peak is less than that of the apparent tetramer form (1.6; see below) but more than the monomer form, i.e. the dimer stoichiometry appears to be ~1. In agreement with this, samples of apparent dimer that were produced upon further SEC of dilute tetramer bound 0.92 copper per monomer, essentially the same as that reported for the dimer of yeast Cox11 (16).

The relatively abundant apparent tetramer of R. sphaeroides Cox11 binds ~1.6 copper per monomer (Table 1), or 50% more copper than the dimers of R. sphaeroides and yeast Cox11-Trx. Since the tetramer of Cox11 appears ~90% pure (Fig. 3), the copper per monomer value is likely underestimated by approximately 10%. However, we have not subtracted the small amount of copper that can be bound by the thioredoxin domain of Cox11-Trx from the other measurements in Table 1, leading to a slight inflation of the copper per monomer value. For wild-type Cox11 and many of the other Cox11 forms these two factors roughly cancel. Hence, the apparent tetramer of wild-type Cox11-Trx contains at least two copper ions in addition to the four copper ions predicted to be present in the two Cu(I) clusters of the dimers.

Table 1.

Copper content of the apparent tetramer of soluble Cox11 forms

| Cox11-Trx tetramer form | Cu(I) per monomer |

|---|---|

| WT | 1.58 ± 0.09 (n=5) |

| Yeast | 1.59 ± 0.04 (n=2) |

| Thioredoxin domain alone | 0.18 ± 0.08 (n=3) |

| C126A | 0.16 |

| C128A | 0.22 ± 0.03 (n=4) |

| C126A-C128A | 0.14 |

| C35S-C126A-C128A | 0.10 |

| C35S | 1.53 ± 0.16 (n=4) |

| F127I | 1.63 ± 0.04 (n=3) |

| F127Y | 1.60 ± 0.05 (n=2) |

| F129Y | 1.12 ± 0.02 (n=3) |

| K123E | 1.39 ± 0.08(n=2) |

| K123R | 1.32 ± 0.16 (n=2) |

| K123L | 1.13 ± 0.05 (n=2) |

| K123L-E131K | 1.04 ± 0.04 (n=2) |

| E131K | 1.46 ± 0.07 (n=2) |

| Y110R | 1.65 ± 0.05 (n=2) |

| Y110E | 1.63 ± 0.15 (n=2) |

The apparent hexamer form binds approximately 20-30% less copper than tetramer, with an average stoichiometry of 1.3 copper per monomer. This value is consistent with a putative hexamer form composed of one tetramer binding six Cu(I) plus one dimer binding two Cu(I).

Because the apparent tetramer from of R. sphaeroides Cox11 binds the most copper and can be obtained in a reasonably pure form without over-purification (in contrast to the dimer form) it is the obvious choice for comparative analyses of the copper content of mutant Cox11 forms (Table 1). In order to confirm this choice further characterizations were performed. As detailed above, the apparent tetramer of R. sphaeroides Cox11 binds ~50% more copper than that previously reported for the dimers of yeast Cox11 or S. mellioti Cox11. This leads to the question of whether R. sphaeroides Cox11 exhibits fundamentally different copper binding than mitochondrial and Sinorhizobium Cox11 or if the differences are due to the analysis of dimer rather than tetramer in the previous studies. The latter appears to be the case since our preparations of the apparent tetramer of yeast Cox11-Trx also bind more copper (Table 1). The apparent tetramers of yeast and R. sphaeroides Cox11 each bind ~50% more copper than their corresponding dimer forms. We conclude that the copper binding characteristics of yeast and bacterial Cox11 are similar if not identical.

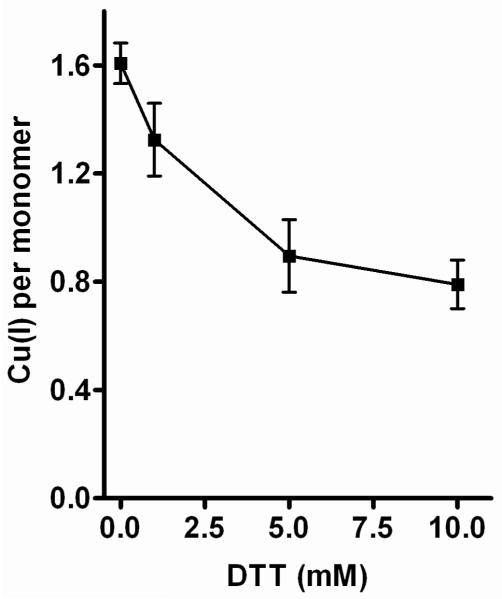

Our purifications of Cox11-Trx contain 0.5-1.0 mM DTT throughout to prevent aggregation via disulfide bonds and the weak binding of Cu(I) on the protein surface. However, DTT can remove Cu(I) from chaperones (27) and the affinity by which Cox11 binds copper is yet to be rigorously explored. In order to determine if our purification procedures were removing significant amounts of copper from Cox11, samples of the apparent tetramer were dialyzed against increasing concentrations of DTT in the absence of O2 and at high molar ratios of DTT to Cox11 (5.6 × 104 at 10 mM DTT) (Fig. 4). The dialysis experiments reveal the presence of two populations of bound Cu(I), one which can be removed with high DTT concentrations and one that cannot (Fig. 4). The copper removed by DTT is bound with an affinity similar to that of copper in mitochondrial Cu4Cox17 (KCu =10−14 M; (27)), while the remainder is bound more tightly. The data do not identify the molecular origins of these two populations. Some copper is released upon extensive dialysis against 1 mM DTT, but at a much higher molar ratio of DTT to Cox11 than occurs during Cox11 purification. It seems unlikely that DTT is removing significant amounts of bound Cu(I) during the purification of Cox11-Trx.

Figure 4.

Removal of Cu(I) from Cox11 by equilibrium dialysis against DTT. One ml samples of 4 to 8 μM wild-type Cox11 were placed in 3,500 Da molecular weight cut-off Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (Pierce) and each was dialyzed against one liter of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.5 M NaCl, 20% glycerol and 1, 5 or 10 mM DTT for 8-12 hours at 4°C. The dialysis buffer was purged with argon before use and dialysis was carried out under an argon atmosphere. Following dialysis, the samples were washed and prepared for copper and sulfur determinations by ICP-OES as described in Methods.

Mutagenic analysis of Cox11

In order to explore the mechanism by which Cox11 effects CuB assembly, we have mutagenized a set of amino acid residues, conserved from Rhodobacter to humans, in two forms of Cox11. The mutations were introduced into soluble Cox11-Trx to determine their effect on copper binding and into full-length, membrane-bound Cox11 in R. sphaeroides to determine their effect on CuB assembly. This approach allows us to identify Cox11 alterations that 1) eliminate or alter copper binding, 2) allow copper binding and CuB assembly, or 3) allow copper binding but eliminate CuB assembly. This last category is of particular interest in terms of inferring mechanism. Three classes of mutants were created to gain insight into the roles of 1) the CFCF motif of each monomer that come together in the Cox11 dimer to create the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster, 2) a third completely conserved cysteine, Cys-35, known to be required for Cox11 function, and 3) a large uncharged region surrounding the Cu(I) cluster, which contains a completely conserved lysine, Lys-123, as the only charged residue (Fig. 1).

The CFCF copper binding site

The cysteines of the CFCF motif were modified to serines and alanines in single mutations, and to alanines in a double mutant. The mutants C126A, C128A and the double mutant C126A-C128A bind only trace amounts of Cu(I), approximately the same amount as that bound by the thioredoxin domain alone (Table 1). Therefore, all copper binding by R. sphaeroides Cox11, including the additional copper of the tetramer, requires both C126 and C128, in agreement with the previous analysis of yeast Cox11 (16). When these mutations, along with C126S and C128S, are placed in native Cox11 the resulting CcOs show no activity (Table 2), consistent with the absence of CuB.

Table 2.

Steady-state activities and optical peak maxima of CcO assembled by different Cox11 forms

| Cox11 form used to assemble CcO |

CcO TNmax (e− s−1) |

Position of the α-band of purified CcO (nm) |

Position of the Soret band of purified CcO (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1850 ± 57a | 606.0 | 444.4 |

| ΔCuB b | Inactive | 602.5 | 441.6 |

| C126S | Inactive | 603.6 | 442.4 |

| C128A | Inactive | 602.8 | 441.6 |

| C128S | Inactive | 602.5 | 442.0 |

| C35S | Inactive | 603.0 | 442.0 |

| F127I | 1627 ± 23 | 605.2 | 444.8 |

| F127W | 1676 ± 6 | 605.0 | 444.5 |

| F127Y | 1657 ± 14 | 605.6 | 444.8 |

| F129Y | 1767 ± 37 | 606.0 | 444.0 |

| K123E | Inactive | 603.8 | 442.8 |

| K123R | Inactive | 603.5 | 442.0 |

| K123L | Inactive | 603.4 | 442.4 |

| K123L-E131K | Inactive | 603.5 | 442.0 |

| E131K | 1591 ± 79 | 605.8 | 444.4 |

| Y110R | 710 ± 6 | 604.6 | 443.0 |

| Y110E | Inactive | 603.5 | 442.2 |

Error is standard deviation from two or more determinations. Given the range exhibited numerous preparations of CcO assembled with wild-type Cox11, values ~1600 s−1 and above are considered normal.

Purified CcO assembled in the absence of Cox11 (13)

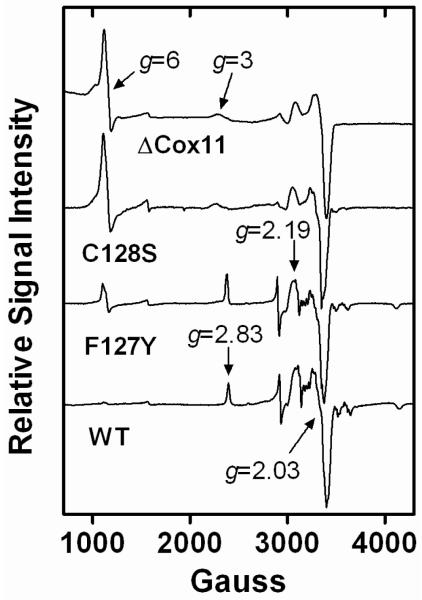

As a representative example of a CcO form that lacks activity due to assembly in the presence of an altered form of Cox11, CcO isolated from the R. sphaeroides strain expressing C128S Cox11 (‘C128S’ CcO) was examined in detail. As expected from its inactivity, ‘C128S’ CcO appears in all respects identical to the CcO form termed ΔCox11, which lacks CuB due to assembly in the complete absence of Cox11 (13). Figure 5 shows that the EPR spectrum of purified ‘C128S’ CcO is essentially identical to that previously published for ΔCox11 (13). A signal for high-spin heme a3 appears at g=6 indicating the absence of CuB; heme a3 normally spin couples with CuB such that both metal centers are EPR silent. (The g=6 signal of heme-Cu oxidases lacking CuB is not as intense as an equimolar high spin heme standard (13, 28, 29) possibly because much of the heme becomes low-spin (30).) Also, as previously seen and interpreted for ΔCox11, the environment of low-spin heme a is altered in the absence of CuB (13). The signal for heme a at g=2.83 is broadened and shifted to g=3 in the spectra of ‘C128S’ CcO and ΔCox11 (Fig. 5). Regardless of changes in the environments of the hemes, pyridine hemochrome spectra (not shown) show that both hemes a and a3 are present in ‘C128S’ CcO and ΔCox11. The amplitude of the signals in the g=2 region of the ‘C128S’ CcO EPR spectrum indicates the presence of normal levels of the di-copper CuA center, as occurs in ΔCox11 (13). The assembly of CuA is independent of the assembly of CuB. Metal analysis by ICP-OES shows that ‘C128S’ CcO contains only two rather than three copper atoms (Table 3), consistent with the presence of CuA and the absence of CuB. In sum, the various spectroscopic analyses of ‘C128S’ CcO show the complete absence of CuB but retention of CuA, heme a and heme a3.

Figure 5.

EPR spectra of purified CcO assembled in the presence of no Cox11 (ΔCox11), C128S Cox11, F127Y Cox11 and wild-type (WT) Cox11. The latter three spectra were recorded at X-band using a Bruker (Billerica MA) EMX spectrometer. The spectra are an average of 5 scans taken at 10K using 10-25 μM CcO. The spectra were obtained using 2 mW microwave power at 9.38 GHz. The sweep time was 160 sec and the time constant was 83 ms. The spectrum of ΔCox11 CcO is taken from Hiser et al (13) and the slight shifts in signal positions are due to the use of a different spectrophotometer in that study.

Table 3.

Metal analysis of selected CcO forms isolated from R. sphaeroides strains expressing normal and mutant versions of Cox11

| CcO form assembled in the presence of: |

[Cu]a | [Fe]a | Cu/Feb | Cu content per CcOc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Cox11, prep 1 | 6.96 | 5.09 | 1.37 | 3.0 |

| Normal Cox11, prep 2 | 7.16 | 5.18 | 1.38 | 3.0 |

| F127Y Cox11 | 9.72 | 6.86 | 1.42 | 3.1 |

| F129Y Cox11 | 9.44 | 6.39 | 1.48 | 3.2 |

| C128S Cox11 | 7.37 | 9.42 | 0.78 | 1.7 |

| K123E Cox11 | 5.89 | 6.31 | 0.93 | 2.0 |

micromolar

The CcO forms measured here were isolated by Ni-affinity chromatography. Without further purification, variable amounts of contaminating iron-containing proteins lower the Cu/Fe value up to 10%.

Calculated by normalizing the Cu/Fe value of 1.37 to 1.5, based on the presence of three Cu and two Fe in normally assembled, highly active CcO

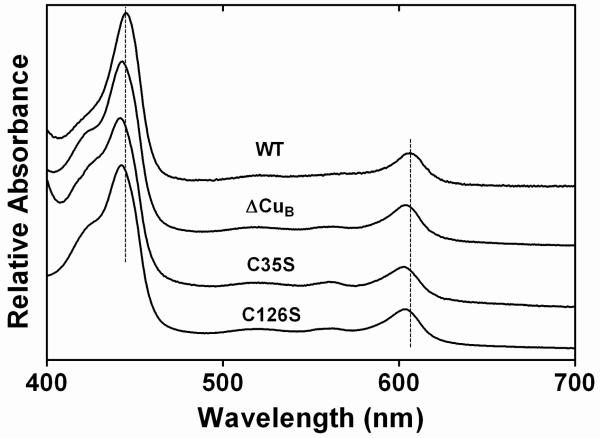

We have previously shown that the absence of CuB leads to a significant blue-shift in the α and γ bands of the electronic spectrum of reduced CcO ((13)and Fig. 6). The spectra of C126S, C128S and all of the CcO forms that are inactive due to assembly in the presence of an altered Cox11 also show these shifts (Fig. 6; Table 2). Hence, the blue-shifted optical spectra also provide physical evidence for the absence of CuB, as has been noted by Banting and Glerum (22) in their mutagenic analysis of yeast Cox11.

Figure 6.

Absolute reduced optical spectra of purified CcO assembled in the presence of wild-type Cox11, C126S Cox11, C35S Cox11 or no Cox11 (ΔCuB). Samples were reduced in a buffer of 50 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2, 0.1% dodecyl maltoside by adding solid sodium dithionite to a final concentration ~10 mM. The dashed lines emphasize the blue shifts of the α and Soret peaks.

In all sequences of Cox11, the phenylalanines of the CFCF motif are completely conserved. In the model of the Cox11 dimer proposed by van Dijk et al (19) (Fig. 1) all four of the CFCF phenylalanines of the dimer orient with their side chains extending into the protein, essentially creating a system of piers that elevates the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster above the plane of the protein surface. The ring of Phe-129 is more buried than that of Phe-127, and therefore less likely to tolerate a substitution. In yeast Cox11, the alteration of the equivalent of Phe-127 to alanine had no effect on CuB assembly (based upon growth of the yeast mutant on a respirable substrate) while a Phe-129→Ala alteration eliminated CcO activity (22). The effect of this mutation on copper binding has not been assessed. Given the more buried nature of the Phe-129 side chain, it is possible that the alanine variant destabilized copper binding by allowing this region of the protein to fold in around the smaller side chain of alanine. Here, we have tested the apparent evolutionary requirement for phenylalanine in the CFCF motif by altering these residues to larger hydrophobic residues side chains, including tyrosine, tryptophan and isoleucine. The mutation of Phe-127 to isoleucine or tyrosine has no obvious effect on copper binding, since these mutant Cox11-Trx forms bind the same amount of copper as wild-type Cox11-Trx (Table 1). The activities of CcO assembled in the presence of F127I, F127Y and F127W Cox11 are near normal (Table 2) indicating that these Cox11 forms are functional. CcO assembled by F127Y Cox11 was more thoroughly examined by EPR spectroscopy. The EPR spectrum of F127Y shows a small signal for high spin heme a3 plus a slight signal at g=3 (Fig. 5), the combination of which suggests the presence of a small amount of the CcO lacking CuB in the CcO population purified from cells expressing F127Y Cox11. However, the level of expression of the CcO complex in the cytoplasmic membranes of these cells is normal and the isolated enzyme contains a normal amount of copper (Table 3), consistent with only small amounts of defective CcO. Interestingly, the alteration of Phe-129 to tyrosine resulted in a loss of copper nearly equivalent to the amount of the ‘additional’ copper bound by the apparent tetramer form of normal soluble Cox11 (Table 1). Nonetheless, the CcO expressed in the presence of R. sphaeroides F129Y Cox11 is highly active (Table 2) indicating that this mutant Cox11 assembles CuB. The presence of CuB is confirmed by the presence of normal amounts of copper in the isolated oxidase (Table 3). Together, these data suggest that the additional copper bound by the apparent tetramer is not required for Cox11 function and that copper transfer is efficient as long as hydrophobic supports for the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster are maintained.

Cys-35

The third cysteine of Cox11, Cys-35, is also completely conserved. The equivalent of Cys-35 in yeast Cox11 has been proposed to participate in copper binding in the dimer (17). Cys-35 of R. sphaeroides Cox11 was altered to serine in a single mutation and also included in a triple mutant that removes all three of the cysteines of Cox11. The copper-binding stoichiometry of the apparent tetramer of C35S Cox11-Trx (Table 1) indicates that Cys-35 is not required for binding the copper of the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster of the dimer or for binding the ‘additional’ copper of the tetramer. Several of the C35S Cox11-Trx preparations contained less monomer than wild-type Cox11, allowing somewhat more reliable estimation of the copper binding stoichiometry of the dimer form from the first SEC separation than was possible for wild-type Cox11. The copper stoichiometry obtained from the trailing edge of the dimer peak (i.e. dimer plus some monomer) averaged 0.87 ± 0.12 (n=3), confirming that the dimer of C35S Cox11-Trx binds a normal level of copper.

Regardless of normal copper binding, Cys-35 is required for CuB assembly. An alanine variant of the equivalent of Cys-35 in yeast Cox11 eliminates the accumulation and activity of yeast CcO (16, 22). In R. sphaeroides, where CcO will accumulate without CuB, the optical spectrum (Fig. 6) and inactivity of the CcO complex expressed in the presence of C35S Cox11 (Table 2) confirms that this mutation eliminates the ability of Cox11 to insert CuB.

It has also been proposed that Cys-35 forms an intermolecular disulfide bond that stabilizes the dimer form of Cox11 (17). However, SEC of C35S Cox11-Trx shows that Cys-35 is not required for the dimerization of soluble Cox11 (data not shown).

Lys-123 in the neutral region surrounding the Cu(I) cluster

The structural model of dimeric Cox11 (Fig. 1) shows only hydrophobic or neutral residues in a wide belt surrounding the Cu(I) cluster. A notable exception is the completely conserved Lys-123 within this neutral region. The two Lys-123 residues of the Cox11 dimer flank the Cu(I) cluster at a distance of approximately 11Ǻ (Fig. 1). Alteration of the equivalent of Lys-123 to glutamate in yeast Cox11 eliminates the accumulation of mitochondrial CcO, consistent with inability of the altered chaperone to insert CuB (22). Conserved lysine residues are located close to the Cu(I) binding sites of other chaperones, including Cox17 of mitochondria (31) and Atx1 of the eukaryotic cytoplasm (32, 33). For these chaperones and for Cox11 it has been proposed that the conserved lysines stabilize the binding of the Cu(I) cation by charge balance, e.g. in Cox11 the two Lys-123 residues would equalize the −2 charge imbalance created by the 4 thiolate (−4) – 2 Cu(I) (+2) cluster of the dimer (17). Therefore, the loss of Cox11 function seen for K123E of yeast could result from an inability of the mutant Cox11 to bind copper.

Our analysis of Lys-123 involved the creation of five mutant Cox11 forms. K123E duplicates the yeast mutant and reverses charge at position 123. K123L eliminates charge at this position. K123R maintains positive charge at position 123, but removes the longer side chain of lysine. Alteration of conserved Glu-131 to lysine (E131K) creates a ring of four lysines around the Cu(I) cluster (see Fig. 1). Finally, the double mutant K123L-E131K essentially rotates these two lysines that are close to the Cu(I) cluster by approximately 90° while retaining their proximity to the Cu(I) center. None of the Cox11 mutants that eliminate Lys-123, even the conservative mutant K123R, assemble CuB, based upon the finding that the resulting CcO complexes show no activity and their optical spectra exhibit the blue-shifts of the α and γ bands indicative of the absence of CuB (Table 2). As a representative of this group, the metal content of CcO assembled in the presence of K123E Cox11 was determined. The analysis shows the loss of one copper (Table 3) consistent with the complete absence of CuB. Importantly, all of these Cox11-Trx mutants that lack Lys-123 bind copper (Table 1), arguing that destabilization of the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster by charge imbalance cannot account for their lack of function.

We noted that the Lys-123 mutants containing leucine at this position, K123L and K123L-E131K, showed Cu(I) binding stoichiometries consistent with the loss of the ‘additional’ copper bound by the apparent tetramer form. It was further noted that both of these mutants accumulated greater amounts of the dimer form (Fig. 2C) perhaps because interprotein interactions that stabilize a tetramer are weakened. The copper binding stoichiometries of the dimer forms were also measured and found to be similar to that of the dimer form of wild-type Cox11-Trx, 0.80±0.05 copper per monomer for the dimer of K123L and 0.91±0.06 for the dimer of K123L-E131K.

The extendable side chain of lysine appears absolutely required for Cox11 to insert CuB; the shorter side chain of arginine does not suffice. Further, the position of the lysines appears critical, since the 90° shift afforded by K123L-E131K Cox11 does not allow CuB assembly. In contrast, the results obtained for the E131K mutant indicate that the presence of two additional lysines near the Cu(I) cluster has no effect on the ability of Cox11 to bind copper or assemble CuB (Tables 1 & 2). The structure of Cox11 shows no neutralizing carboxylic side chain close to Lys-131 of this mutant, therefore all four of the lysines surrounding the Cu(I) cluster should be charged.

Introduction of charge into the neutral region

Tyr-110 is a highly conserved residue whose phenol ring extends from the surface of Cox11 within the neutral zone surrounding the Cu(I) cluster; the side chain of each Tyr-110 residue is within 9-10Å of the nearest copper ion (Fig. 1). Tyr-110 was altered to glutamate and arginine to determine how the introduction of negative or positive charge in the neutral region close to the Cu(I) cluster would affect copper binding and Cox11 function. Both Y110E and Y110R Cox11 bind the normal amount of copper for the apparent tetramer form (Table 1), showing that the presence of negative or positive charge close to the CFCF motif does not preclude formation of the Cox11 copper center. However, the Tyr-110→Glu variant of Cox11 does not insert CuB, while the Tyr-110→Arg variant does, albeit with lower efficiency based on the lower activity of the isolated complex (Table 2). The latter result differs from that obtained earlier with the alteration of the equivalent of Tyr-110 of yeast to arginine; in yeast, the arginine mutant showed no CcO accumulation or activity (22). Along with the alterations of Lys-123, discussed above, the results obtained with Tyr-110 imply that the introduction of positive charge into the neutral region allows Cox11 function while the introduction of negative charge does not.

DISCUSSION

Copper binding by soluble Cox11

Previous studies have concluded that soluble Cox11 binds copper in a 4 cysteine-2 Cu(I) cluster that forms at the interface of two monomers (16, 17). Each copper of the cluster is bound by three sulfur ligands. X-ray spectroscopy (EXAFS) of the dimer of yeast Cox11-Trx showed three Cu-S bonds at 2.25 Å and one Cu-Cu bond at 2.71 Å (16). The dimer form of R. sphaeroides Cox11 binds two coppers, in agreement with previous studies of yeast and Sinorhizobium Cox11 (16, 17). However, this report shows that the apparent tetramers of soluble Cox11 from both R. sphaeroides and yeast bind additional copper, at least two more than can be accounted for by the two coppers bound by each dimer. Metal analysis of the mutant forms of soluble Cox11 shows that all of the copper in the apparent tetramers appears to be bound using the cysteines of the CFCF motifs of each monomer. Cys-35 is not required. EXAFS analysis of the wild-type form of the apparent tetramer of R. sphaeroides Cox11-Trx (M. J. Pushie and G. George, Univ. of Saskatchewan, unpublished results) shows the presence of a polycopper cluster with trigonal sulfur ligation and bond distances as described above for the Cu(I)-S cluster of the yeast Cox11 dimer. The data are consistent with a cluster formed from a merger of the 4 Cys-2 Cu(I) clusters from two dimers; one possibility is a hexacopper cluster (34) that would match the stoichiometry of copper binding measured for the apparent tetramer. Further study is required.

It remains unclear if oligomers of Cox11 larger than dimer play any role in vivo. The studies of Leary et al (35) show that the primary form of Cox11 isolated from human mitochondrial membranes with detergent exhibits a Mr corresponding to dimer, but significant amounts of Cox11 with a Mr values corresponding to higher order oligomers are also present. If the dimer of Cox11 is positioned above the membrane with the Cu(I) cluster facing the surface of the membrane, an orientation predicted by the dimer model of van Dijk et al (19), it becomes difficult to envision a role for an oligomer such as tetramer in copper delivery. However, a tetramer could be involved in functions other than copper transfer to subunit I of CcO, such as the storage of Cu(I) or the re-metallation of Cox11. Of primary significance for this study is that the ability of the apparent tetramer of soluble Cox11 to form a copper cluster larger than that of the dimer demonstrates the inherent flexibility of Cu(I) binding by the cysteines of Cox11, as has been shown for other Cu(I)-S centers (33, 36-38). This becomes important as we consider a possible role of Cys-35 in copper transfer (below).

The role of Cys-35 and implications for the mechanism of CuB insertion

Previous mutagenic analysis of Cox11 in yeast has established that Cys-35 (Cys-111 in yeast Cox11) is required for Cox11 function (16, 22). Here, we have confirmed this absolute requirement by showing that Cox11 appears completely inactive if the thiol of Cys-35 is altered to a hydroxyl group. However, in contrast to previous work (16), we find that this loss of function is not due to an inability of Cox11 lacking Cys-35 to bind copper. The stoichiometries of copper binding by C35S Cox11 indicates that Cys-35 is necessary neither for the formation of the 4-Cys-2 Cu(I) cluster of the dimer nor for binding the additional copper in the tetramer. Another proposal for Cys-35 function has been that it forms an intermolecular cross-link necessary to stabilize the dimer form of Cox11 (17). However, our experiments indicate that Cox11 forms dimer and higher order oligomers in the absence of Cys-35. This finding does not exclude the possibility that a Cys-35 disulfide could help stabilize the dimer form in the membrane, but it does indicate that such a function is unlikely to present as an absolute requirement for CuB assembly. Therefore, what is the role of Cys-35? Based upon the chemistry of cysteine and the function of Cox11, the two most likely possibilities are 1) participation of Cys-35 in a disulfide bond with the target(s) of Cox11, or 2) transient Cu(I) binding by Cys-35 during copper transfer to the nascent CuB binding site.

A disulfide bond could link Cox11 and its target in order to facilitate copper transfer, as has been proposed to occur during the transfer of copper from the copper chaperone CCS to apo-SOD (39). However, the possibility of a disulfide bond between Cox11 and CcO subunit I appears excluded by the finding that all of the cysteines of R sphaeroides CcO can be eliminated, except for the two cysteines that bind CuA, without altering the activity of the enzyme (R. Gennis, personal communication). In R. sphaeroides, Cox11 may also interact with three other proteins that function in the assembly of the metal centers of subunit I. In yeast, Cox11 interacts with the homolog of bacterial Surf1 (40), a membrane protein that increases the efficiency of insertion of heme a3 (14) and has recently been shown to bind heme A (41). Cox11 may also interact with the complex of Cox 10 (heme O synthase) and Cox 15 (heme A synthase), which likely function in the insertion as well as the synthesis of heme A (42). In R. sphaeroides, neither Cox10, Cox15 nor Surf1 contain cysteine, which strongly argues against a conserved mechanism in which Cox11 forms a disulfide with any of these assembly proteins.

In contrast, a role for Cys-35 as a transient Cu(I) ligand during copper transfer would be consistent with the results presented here, with the position of Cys-35 in Cox11 and with the position of the nascent CuB center within subunit I. Cys-35 is adjacent to the C-terminal phenylalanine of the predicted transmembrane helix of R. sphaeroides Cox11, which places the residue close to the surface of the membrane. The modeling of van Dijk et al (19) predicts that the dimer of Cox11 is positioned above the membrane surface with the copper cluster facing the membrane; the copper-binding dimer is connected to two TM helices by flexible linkers. As newly translated CcO subunit I is inserted into the membrane and its regions of α helix form, one of the three CuB ligands, His-284, will be constrained to the middle of the bilayer in helix 6. In contrast, the other two CuB ligands, His-333 and His-334 (two of the five completely conserved residues in heme-Cu oxidases), are located in a less ordered structure leading into the loop between transmembrane helices 7 and 8. In loosely-folded subunit I, the peptide span containing His-333/334 may move up toward the surface of the membrane, toward the Cys-35 residues of the Cox11 dimer. We propose that the two Cys-35 thiolates mediate copper transfer by participating in a short series of copper binding structures with both the Cu(I) cluster of Cox11 and His-333/334 of subunit I. For example, the side chains of Cys-35 may first interact with the Cys-126/Cys-128 ligands of the Cu(I) cluster to form a transient (Cys-35)2/(Cys-126)2/Cu(I) structure, and then with His-333/334 to create a transient (Cys-35)2/His-333/334/Cu(I) cluster. The final formation of CuB would be driven by the concomitant insertion of heme a3 into subunit I, the completion of subunit I folding and the recession of His333/334 plus Cu(I) into the protein interior. Heme a3 insertion is assigned as the driving force in this scenario because heme a3 insertion and subunit I folding can proceed without the insertion of CuB, while CuB insertion does not appear to occur in the absence of heme a3 insertion (13, 14).

The scheme presented above elaborates that proposed by Khalimonchuk et al (20), in which copper transfer occurs during translation and the insertion of subunit I into the membrane, although we do not envision that helix 7 or the loop containing His-333/334 moves out of the bilayer into the periplasm. Rather, we interpret the requirement for Cys-35 as an indication that copper transfer takes place at the surface of the membrane. The scheme differs from ones proposing the delivery of copper via a cavity leading from the top of subunit I to the region of His-334 (21) in that it proposes that 1) CuB insertion occurs at an earlier point, i.e. before tertiary structure creates the cavity, and 2) the Cu(I) cluster approaches the surface of the membrane rather than the upper surface of largely folded subunit I. Indeed, if Cox11 were to deliver copper by docking on the upper surface of subunit I it would be difficult to explain the requirement for Cys-35, which cannot move to the upper surface of the protein due to its proximity to the transmembrane helix of Cox11.

The role of Lys-123 and the requirement for Cox11

The Cu(I) cluster of the dimer of Cox11 lies within a region where the surface of the protein lacks charged residues. This situation is common to several other Cu(I) chaperones, perhaps to prevent electrostatic interference during copper transfer. A pair of lysines, Lys-123 of each monomer, is present within the neutral zone of the Cox11 dimer, close to the Cu(I) cluster. The presence of conserved lysines near Cu(I) binding sites is also a common structural feature of Cu(I) chaperones (31-33). We have confirmed the previous finding in yeast Cox11 (22) that Lys-123 is absolutely required for the assembly of CuB.

For Cox11, it has been proposed that the role of Lys-123 is to balance the overall negative charge (−2) of the Cu(I) cluster of the dimer (17). This role could account for the loss of Cox11 function if the Cu(I) cluster could not form in the absence of the charge balance provided by Lys-123. However, this study shows that alterations of Lys-123 to neutral or negatively charged residues still allow copper binding by Cox11. This does not rule out a charge balance role for Lys-123 in normal Cox11 but such a role cannot explain its absolute requirement for Cox11 function.

Molecular dynamics simulations of the copper chaperone Atox1 (Hah1) show that its conserved lysine interacts electrostatically with the two copper binding cysteines of the target protein (ATP7B; (43)), apparently to stabilize their deprotonated, copper-binding forms. Such a mechanism for Lys-123 of Cox11 is possible, i.e. the positively charged amines of the Lys-123 pair could stabilize the neutral imidazoles and the cysteine thiolates of our proposed Cys-35-His-333/334 Cu(I) copper transfer intermediate. It would not be expected, however, that the lack of electrostatic stabilization (e.g. K123L Cox11) would completely prevent Cu(I) transfer by Cox11, given that the alteration of the conserved lysine of Atox1 to alanine diminishes but does not eliminate copper transfer (43). Also at odds with this proposal is that even with the retention of positive charge at position 123 of Cox11 (K123R) the removal of Lys-123 completely prevents CuB insertion.

Lysine contains the most extendable and flexible side chain of the common amino acids, and as such it often plays a role in protein-protein interactions. Hence, Lys-123 may be required for a protein-protein contact with a specific geometry. Clearly, Lys-123 is not required for the self-association of Cox11 even though the leucine variant (K123L) accumulates more dimer than tetramer. An obligatory role for Lys-123 in recognizing the chaperone that metallates Cox11 also seems unlikely based upon the following. Cox17, the proposed Cu(I) donor to Cox11 in mitochondria (44), has no structural cognate in bacteria. Possible Cu(I) donors to Cox11 in periplasm of R. sphaeroides include bacterial Sco1 (known as PrrC in R. sphaeroides) and a widespread bacterial Cu(I) chaperone first termed DR1885 (45-47). In experiments to be published elsewhere we have determined that neither Sco1 nor DR1885 of R. sphaeroides are required for the metallation of Cox11 in vivo. Further, DR1885 has no cognate in mitochondria. Since Cox11 in mitochondria and in bacteria are likely metallated by structurally unrelated proteins, it seems unlikely that their common absolute requirement for Lys-123 arises from the metallation interaction.

In contrast, the transfer of copper from Cox11 into the nascent CuB center is likely to require a specific interaction. In the superfamily of heme-Cu terminal oxidases the structure of subunit I is conserved and the structure of the CuB center is highly conserved. However, the analysis of bacterial genomes shows that many bacteria synthesizing a heme-Cu oxidase do not require Cox11 for the insertion of CuB. For example, the cbb3-type CcO of R. sphaeroides assembles CuB without Cox11 (13). Within the large group of α, β and γ proteobacters, from which mitochondria arose, only those species synthesizing a CcO that contains the CuA center, in addition to the CuB center, require Cox11 for the insertion of CuB. We propose that the appearance of Cox11 results from a need for an assembly protein with high selectivity for the nascent CuB center, i.e. a Cu(I) chaperone designed to metallate CuB and not CuA. Our previous studies of CcO assembly demonstrate that subunit II with a normal CuA center will assemble onto the top of subunit I even when CuB is missing (13). This ΔCuB CcO complex is almost certainly a terminal product since the completed folding of subunit I plus the addition of subunits II and III preclude any further assembly of the buried heme a3-CuB center. Since ΔCuB CcO has no activity, its production will negatively impact the cellular energy budget. One solution to improving the efficiency of active CcO production, then, is to prevent the binding of subunit II with CuA until heme a3 and CuB have been inserted into subunit I. This logic predicts that Cox11 delivers Cu(I) to subunit I while the subunit is partially unfolded and cannot bind subunit II, and that Cox11 shows a strong preference for metallating the CuB site and not the CuA site. These conditions require efficient (specific) recognition of the nascent CuB center by Cox11. The Cu(I) cluster itself is unlikely to provide such specificity; in fact, our proposed copper transfer intermediate has greater similarity to CuA than it does to CuB. Although we cannot yet propose a specific target for Lys-123, we suggest that its absolute requirement and its proximity to the Cu(I) cluster strongly imply a role for target recognition and binding.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Dr. John J. Correia, Daniel Lyons and Dr. Neal Robinson for assistance with analytical ultracentrifugation and Drs. M. Jake Pushie and Graham George for EXAFS analysis of Cox11-Trx. The authors also thank Dr. Jim Hemp, the group of Prof. Bernd Ludwig (particularly Dr. Peter Greiner) and Dr. Shelagh Ferguson-Miller for valuable discussions.

Supported by NIH GM56824 to J.P.H, NSF MCB-0843537 to A.L. and NIH ES03817 to D.R.W.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CcO

the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase

- ΔCuB

CcO assembled in R. sphaeroides in the absence of Cox11

- ICP-OES

inductively-coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

- Trx

E. coli thioredoxin

REFERENCES

- 1.Hosler JP, Ferguson-Miller S, Mills DA. Energy Transduction: Proton Transfer Through the Respiratory Complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:165–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.062003.101730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter OM, Ludwig B. Cytochrome c oxidase--structure, function, and physiology of a redox-driven molecular machine. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;147:47–74. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. Structures of metal sites of oxidized bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 Å. Science. 1995;269:1069–1074. doi: 10.1126/science.7652554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostermeier C, Harrenga A, Ermler U, Michel H. Structure at 2.7 Å resolution of the Paracoccus denitrificans two-subunit cytochrome c oxidase complexed with an antibody Fv fragment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10547–10553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin L, Hiser C, Mulichak A, Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Identification of conserved lipid/detergent-binding sites in a high-resolution structure of the membrane protein cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:16117–16122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yamashita E, Inoue N, Yao M, Fei MJ, Libeu CP, Mizushima T, Yamaguchi H, Tomizaki T, Tsukihara T. Redox-coupled crystal structural changes in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Science. 1998;280:1723–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5370.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemp J, Gennis RB. Diversity of the heme-copper superfamily in archaea: insights from genomics and structural modeling. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 2008;45:1–31. doi: 10.1007/400_2007_046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haltia T, Semo N, Arrondo JL, Goni FM, Freire E. Thermodynamic and structural stability of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9731–9740. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bratton MR, Hiser L, Antholine WE, Hoganson C, Hosler JP. Identification of the structural subunits required for formation of the metal centers in subunit I of cytochrome c oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12989–12995. doi: 10.1021/bi0003083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin L, Sharpe MA, Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Conserved lipid-binding sites in membrane proteins: a focus on cytochrome c oxidase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao J, Hosler J, Shapleigh J, Revzin A, Ferguson-Miller S. Cytochrome aa3 of Rhodobacter sphaeroides as a model for mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. The coxII/coxIII operon codes for structural and assembly proteins homologous to those in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:24273–24278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosler JP, Fetter J, Tecklenburg MM, Espe M, Lerma C, Ferguson-Miller S. Cytochrome aa3 of Rhodobacter sphaeroides as a model for mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Purification, kinetics, proton pumping, and spectral analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:24264–24272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiser L, Di Valentin M, Hamer AG, Hosler JP. Cox11p is required for stable formation of the CuB and magnesium centers of cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:619–623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith D, Gray J, Mitchell L, Antholine WE, Hosler JP. Assembly of cytochrome c oxidase in the absence of assembly protein Surf1p leads to loss of the active site heme. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:17652–17656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzagoloff A, Nobrega M, Gorman N, Sinclair P. On the function of yeast COX10 and COX11 gene products. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1993;31:593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carr HS, George GN, Winge DR. Yeast Cox11, a protein essential for cytochrome c oxidase assembly, is a Cu(I) binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:31237–31242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banci L, Bertini I, Cantini F, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Gonnelli L, Mangani S. Solution structure of Cox11, a novel type of beta-immunoglobulin-like fold involved in CuB site formation of cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:34833–34839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr HS, Maxfield AB, Horng YC, Winge DR. Functional analysis of the domains in Cox11. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:22664–22669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Dijk AD, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Banci L, Bertini I, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. Modeling protein-protein complexes involved in the cytochrome c oxidase copper delivery pathway. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1530–1539. doi: 10.1021/pr060651f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalimonchuk O, Ostermann K, Rodel G. Evidence for the association of yeast mitochondrial ribosomes with Cox11p, a protein required for the CuB site formation of cytochrome c oxidase. Curr. Genet. 2005;47:223–233. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greiner P, Hannappel A, Werner C, Ludwig B. Biogenesis of cytochrome c oxidase--in vitro approaches to study cofactor insertion into a bacterial subunit I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:904–911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banting GS, Glerum DM. Mutational analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytochrome c oxidase assembly protein Cox11p. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:568–578. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.3.568-578.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills DA, Hosler JP. Slow proton transfer through the pathways for pumped protons in cytochrome c oxidase induces suicide inactivation of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4656–4566. doi: 10.1021/bi0475774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhen Y, Qian J, Follmann K, Hayward T, Nilsson T, Dahn M, Hilmi Y, Hamer AG, Hosler JP, Ferguson-Miller S. Overexpression and purification of cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Prot. Express. Purif. 1998;13:326–336. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steffens GC, Soulimane T, Wolff G, Buse G. Stoichiometry and redox behaviour of metals in cytochrome c oxidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;213:1149–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bratton MR, Pressler MA, Hosler JP. Suicide inactivation of cytochrome c oxidase: catalytic turnover in the absence of subunit III alters the active site. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16236–16245. doi: 10.1021/bi9914107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palumaa P, Kangur L, Voronova A, Sillard R. Metal-binding mechanism of Cox17, a copper chaperone for cytochrome c oxidase. Biochem. J. 2004;382:307–314. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aasa R, Albracht PJ, Falk KE, Lanne B, Vanngard T. EPR signals from cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1976;422:260–272. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(76)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunter DJ, Moody AJ, Rich PR, Ingledew WJ. EPR spectroscopy of Escherichia coli cytochrome bo which lacks CuB. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:43–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egawa T, Lee HJ, Gennis RB, Yeh SR, Rousseau DL. Critical structural role of R481 in cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:1272–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Janicka A, Martinelli M, Kozlowski H, Palumaa P. A structural-dynamical characterization of human Cox17. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:7912–7920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portnoy ME, Rosenzweig AC, Rae T, Huffman DL, O’Halloran TV, Culotta VC. Structure-function analyses of the ATX1 metallochaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15041–15045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.15041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wernimont AK, Huffman DL, Lamb AL, O’Halloran TV, Rosenzweig AC. Structural basis for copper transfer by the metallochaperone for the Menkes/Wilson disease proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:766–771. doi: 10.1038/78999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heaton DN, George GN, Garrison G, Winge DR. The mitochondrial copper metallochaperone Cox17 exists as an oligomeric, polycopper complex. Biochemistry. 2001;40:743–751. doi: 10.1021/bi002315x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leary SC, Kaufman BA, Pellecchia G, Guercin GH, Mattman A, Jaksch M, Shoubridge EA. Human SCO1 and SCO2 have independent, cooperative functions in copper delivery to cytochrome c oxidase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:1839–1848. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Hadjiloi T, Martinelli M, Palumaa P. Mitochondrial copper(I) transfer from Cox17 to Sco1 is coupled to electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6803–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800019105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stasser JP, Siluvai GS, Barry AN, Blackburn NJ. A multinuclear copper(I) cluster forms the dimerization interface in copper-loaded human copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11845–11856. doi: 10.1021/bi700566h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnesano F, Balatri E, Banci L, Bertini I, Winge DR. Folding studies of Cox17 reveal an important interplay of cysteine oxidation and copper binding. Structure (Camb) 2005;13:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamb AL, Torres AS, O’Halloran TV, Rosenzweig AC. Heterodimeric structure of superoxide dismutase in complex with its metallochaperone. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:751–755. doi: 10.1038/nsb0901-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalimonchuk O, Bestwick M, Meunier B, Watts TC, Winge DR. Formation of the redox cofactor centers during Cox1 maturation in yeast cytochrome oxidase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:1004–1017. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00640-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bundschuh FA, Hannappel A, Anderka O, Ludwig B. Surf1, associated with Leigh syndrome in humans, is a heme-binding protein in bacterial oxidase biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:25735–25741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown BM, Wang Z, Brown KR, Cricco JA, Hegg EL. Heme O synthase and heme A synthase from Bacillus subtilis and Rhodobacter sphaeroides interact in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13541–13548. doi: 10.1021/bi048469k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hussain F, Rodriguez-Granillo A, Wittung-Stafshede P. Lysine-60 in copper chaperone Atox1 plays an essential role in adduct formation with a target Wilson disease domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16371–16373. doi: 10.1021/ja9058266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horng YC, Cobine PA, Maxfield AB, Carr HS, Winge DR. Specific copper transfer from the Cox17 metallochaperone to both Sco1 and Cox11 in the assembly of yeast cytochrome c oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:35334–35340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Badrick AC, Hamilton AJ, Bernhardt PV, Jones CE, Kappler U, Jennings MP, McEwan AG. PrrC, a Sco homologue from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, possesses thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase activity. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4663–4667. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Katsari E, Katsaros N, Kubicek K, Mangani S. A copper(I) protein possibly involved in the assembly of CuA center of bacterial cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3994–3999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406150102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abriata LA, Banci L, Bertini I, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Gkazonis P, Spyroulias GA, Vila AJ, Wang S. Mechanism of CuA assembly. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:599–601. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]