Abstract

Problem

Depression is associated with a higher risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications and mortality in diabetes, but whether depression is linked to an increased risk of incident amputations is unknown. We examined the association between diagnosed depression and incident non-traumatic lower limb amputations in veterans with diabetes.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study from 2000-2004 that included 531,973 veterans from the Diabetes Epidemiology Cohorts, a national Veterans Affairs (VA) registry with VA and Medicare data. Depression was defined by diagnostic codes or antidepressant prescriptions. Amputations were defined by diagnostic and procedural codes. We determined the HR and 95% CI for incident non-traumatic lower limb amputation by major (transtibial and above) and minor (ankle and below) subtypes, comparing veterans with and without diagnosed depression and adjusting for demographics, health care utilization, diabetes severity, and comorbid medical and mental health conditions.

Results

Over a mean 4.1 years of follow up, there were 1,289 major and 2,541 minor amputations. Diagnosed depression was associated with an adjusted HR of 1.33 (95% CI: 1.15, 1.55) for major amputations. There was no statistically significant association between depression and minor amputations (adjusted HR 1.01, 95% CI: 0.90, 1.13).

Conclusions

Diagnosed depression is associated with a 33% higher risk of incident major lower limb amputation in veterans with diabetes. Further study is needed to understand this relationship and to determine whether depression screening and treatment in patients with diabetes could decrease amputation rates.

Keywords: depression, diabetes, veterans, amputation, foot ulcer

Introduction

Depression is twice as common in patients with diabetes compared to patients without diabetes (Ali, S. et al. 2006; Anderson, R. J. et al. 2001) and is associated with the development of diabetes complications, including macrovascular disease (Black, S. A. et al. 2003), microvascular disease (Black, S. A. et al. 2003; Roy, M. S. et al. 2007b; Roy, M. S. et al. 2007a), and death (Black, S. A. et al. 2003; Katon, W. J. et al. 2005; Katon, W. et al. 2008). It is unknown whether depression is associated with incident diabetic lower limb amputations. In one study, decreased mental health functioning in diabetes patients was associated with increased odds of major amputation in the following year, but depression was not specifically examined (Tseng, C. L. et al. 2007). In 253 persons with their first diabetic foot ulcer, depressive symptoms were associated with increased mortality (Ismail, K. et al. 2007), but amputation risk was not increased (Winkley, K. et al. 2007). The goal of this study was to determine whether depression is associated with incident diabetic non-traumatic lower limb amputations.

Methods

Study Population

This study was conducted in veterans from the Veterans Health Administration (VA) in fiscal year (FY) 2000. We used the Diabetes Epidemiology Cohorts (DEpiC), a registry of virtually all VA patients with diabetes since FY1998 with patient-level information from both VA and Medicare sources (Miller, D. R. et al. 2004). We used the following inclusion criteria: 1) diabetes [dispensed any diabetes medication in FY 2000 or had two or more International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for diabetes in FY 1999-2000], 2) no prior ICD-9-CM or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for lower limb amputation, 3) no ICD-9-CM codes for bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in FY 1998-2000, 4) and continued use of VA care after study entry (Table 1). The institutional review board at VA Medical Center, Bedford, MA, approved the study and waived informed consent.

Table 1. ICD-9-CM and CPT codes used to define diabetes, depression, amputations, and other conditions.

| Diabetes | ICD-9-CM 250.x |

| Depression | ICD-9-CM 296.2, 296.3, 311, 300.4, 309.0, 293.83, 296.9, 309.1, 296.99, or 301.12 |

| Major amputations | ICD-9-CM 84.15-84.19 |

| CPT 27880-2, 27886, 27598, 27590-2, 27596, or 27295 | |

| Minor amputations | ICD-9-CM 84.11-84.14 |

| CPT 28820, 28825, 28800, 28805, 28810, 27888, or 27889 | |

| Amputation exclusions | |

| Cancer | ICD-9-CM 170.7, 170.8, 172.7, or 173.7 |

| Trauma | ICD-9-CM 895.x-897.x |

| Fracture | ICD-9-CM 905.4 |

| Dislocation | ICD-9-CM 835–838 |

| Crush injury | ICD-9-CM 928–929 |

| Bipolar disorder | ICD-9-CM 296.0-296.1, 296.4-296.8 |

| Schizophrenia | ICD-9-CM 295.x |

| Anxiety disorder | ICD-9-CM 300.0x |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | ICD-9-CM 309.81 |

Depression Groups

Subjects were divided into two groups, those with and without diagnosed depression. Depression was defined by either of the following: 1) at least one inpatient or outpatient ICD-9-CM code for depression (Valenstein, M. et al. 2004) in FY2000 or 2) at least one prescription for selected antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, mirtazapine, venlafaxine, or bupropion) in FY 2000, in the absence of codes for anxiety disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Table 1). Patients using antidepressants without a depression code were included because many patients in primary care do not have a recorded diagnosis of depression, even if their depression is recognized and treated (Liu, C. F. et al. 2006). Tricyclic antidepressants were excluded since they may have been used for painful diabetic neuropathy. Patients with anxiety or PTSD who were prescribed antidepressants without a depression code were considered non-depressed because we assumed the antidepressant was prescribed for anxiety or PTSD.

The date of depression diagnosis in FY2000 was one of the following: 1) the date of the first outpatient depression code, 2) the hospital admission date for a stay with a depression code, or 3) the date the first antidepressant was dispensed. For depressed patients, the index date, or study entry date, was defined as ninety days after the depression diagnosis. This allowed patients a reasonable window of opportunity to receive an antidepressant prescription so we could classify the depression as treated or untreated for a sensitivity analysis (see Statistical Analysis). Non-depressed patients were randomly assigned index dates within the year for a similar distribution of index dates in the depressed and non-depressed groups (“frequency matching” by date).

Outcome

Incident lower limb amputation was defined by codes, excluding amputations associated with cancer or trauma, and classified by amputation subtype, major (transtibial or above) or minor (ankle or below) (Table 1). The highest level of amputation from a single hospitalization was considered the incident amputation (Mayfield, J. A. et al. 2004).

Covariates

Covariates were chosen a priori and based on information collected prior to the index date. Covariates were grouped as follows: demographics (age at study entry, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, homelessness, and VA eligibility status), utilization in the prior year (numbers of outpatient visits, outpatient mental health visits, and hospitalizations), diabetes severity (HbA1c and insulin use in the prior year), other medical conditions (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome), mental health conditions (PTSD, anxiety, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and dementia), cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension and hyperlipidemia), microvascular complications (diabetic eye disease, blindness/low vision, nephropathy, and dialysis), macrovascular complications (ischemic heart disease, prior myocardial infarction, stable angina, prior coronary artery revascularization, congestive heart failure, prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, prior cerebral artery revascularization, other types of atherosclerosis except lower limb, and prior revascularization of other arteries except lower limb), and foot-specific complications (peripheral arterial disease, prior lower limb artery revascularization, peripheral neuropathy, and foot deformity). Diagnoses were defined by at least two ICD-9-CM codes in the two years before the index date, except for prior myocardial infarction and stroke, which were defined by the presence of any prior code. Prior procedures were defined by the presence of any CPT code before the index date. Patients were classified into four categories of VA eligibility: severe disability, moderate disability, poverty, or has co-pay. Veterans without compensable service-related disabilities and incomes below a varying threshold are eligible for care without co-pays, but those without disabilities and incomes above that threshold are charged co-pays. The most recent marital status, living situation, eligibility status, and HbA1c in the year prior to the index date were used. Because of missing data, HbA1c was not included in the final models (see Statistical Analysis).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Surveillance for incident amputations began at the index date and ended on the date of any of the following: 1) death, 2) last VA care or Medicare service use, or 3) December 31, 2004, the last day of the study. Unadjusted amputation incidence rates were calculated by dividing the number of incident amputations by the total person-years of risk. Results are presented for any incident amputation as well as for major and minor subtypes.

We used a Cox regression model to determine the HR and 95% CI for incident non-traumatic lower limb amputation, comparing patients with and without diagnosed depression. Time-on-study was the time scale. We constructed several models in a hierarchical fashion, adding groups of covariates sequentially to examine their potential confounding and mediating effects. The groups were added in the following order: demographics, health care utilization, insulin use, medical conditions, mental health conditions, cardiovascular risk factors, microvascular complications, macrovascular complications, and foot-specific complications. Because the HR changed very little after the addition of the second group of variables (health care utilization), we present only the following three adjusted analyses: adjusted for demographics, adjusted for demographics and utilization, and fully adjusted. Age at study entry and number of visits were modeled as continuous variables. Tested multiplicative interaction terms, including depression*PTSD, depression*age, depression*gender, and depression*race/ethnicity, were not significant and not included in the final models. The proportional hazards assumption was verified for depression using a log-log survival plot. Because amputation practices vary regionally (Wrobel, J. S. et al. 2001), we used robust sandwich covariance matrix estimates to account for possible clustering of outcome observations by site. A Kaplan Meier curve was generated for any amputation by depressed status.

Because approximately 50% of the patients did not have HbA1c values in the year prior to the index date (50.3% in the depressed group and 52.9% in the non-depressed group), this variable was not included in the final models. We did not use multiple imputation because of uncertainty about a model with such a high proportion of imputed values (Fox-Wasylyshyn, S. M. and El-Masri, M. M. 2005). It was reassuring that the baseline distribution of HbA1c was nearly identical between the depressed and non-depressed groups (Table 2) and that the results were unchanged when we performed a complete case analysis using only patients with non-missing values for HbA1c.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics by depression status.

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample n=531,973 |

Diagnosed depression n=84,984 |

No diagnosed depression n=446,989 |

|

| Age, years, mean(sd) | 66.8(10.9) | 64.3(11.7) | 67.2(10.7) |

| Male | 518,207 (97.4) | 81,471 (95.9) | 436,736 (97.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 393,388 (73.9) | 66,848 (78.7) | 326,540 (73.1) |

| Black | 79,385 (14.9) | 9,854 (11.6) | 69,531 (15.6) |

| Hispanic | 28,404 (5.3) | 4,220 (5.0) | 24,184 (5.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5,773 (1.1) | 639 (0.8) | 5,134 (1.1) |

| Native American | 7,247 (1.4) | 1,444 (1.7) | 5,803 (1.3) |

| Unknown | 17,776 (3.3) | 1,979 (2.3) | 15,797 (3.5) |

| Married/living together | 346,405 (65.1) | 52,207 (61.4) | 294,198 (65.8) |

| Homeless | 2,689 (0.5) | 1,060 (1.3) | 1,629 (0.4) |

| VA eligibility status | |||

| Severe disability | 124,330 (23.4) | 28,054 (33.8) | 96,276 (21.5) |

| Moderate disability | 108,017 (20.3) | 16,509 (19.9) | 91,508 (20.5) |

| Poverty | 232,520 (43.7) | 33,724 (40.6) | 198,778 (44.5) |

| Has co-pay | 67,106 (12.6) | 6,679 (8.0) | 60,427 (13.5) |

| Health care utilization | |||

| No. of outpatient visits, mean(sd) | 20.6(21.3) | 28.9(27.7) | 19.0(19.5) |

| No. of outpatient mental health visits, mean(sd) | 0.22(1.68) | 1.32(4.01) | 0.01(0.20) |

| No. of hospitalizations, mean(sd) | 0.46(1.13) | 0.86(1.65) | 0.39(0.99) |

| HbA1c, %, mean(sd) | 7.67(1.76) | 7.70(1.82) | 7.67(1.74) |

| Diabetes treatment | |||

| Insulin | 132,348 (24.9) | 26,102 (30.7) | 106,246 (23.8) |

| Oral medications | 311,958 (58.6) | 50,860 (59.8) | 261,098 (58.4) |

| Other medical conditions | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 65,980 (12.4) | 14,870 (17.5) | 51,110 (11.4) |

| Cancer | 61,910 (11.6) | 10,358 (12.2) | 51,552 (11.5) |

| Acquired immune deficiency syndrome | 1,154 (0.2) | 296 (0.3) | 858 (0.2) |

| Mental health conditions | |||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 16,319 (3.1) | 7,656 (9.0) | 8,663 (1.9) |

| Anxiety | 16,643 (3.1) | 8,481 (10.0) | 8,162 (1.8) |

| Alcohol abuse | 13,105 (2.5) | 4,901 (5.8) | 8,204 (1.8) |

| Substance abuse | 3,848 (0.7) | 1,739 (2.0) | 2,109 (0.5) |

| Dementia | 7,909 (1.5) | 2,967 (3.5) | 4,942 (1.1) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 320,609 (60.3) | 53,765 (63.3) | 266,844 (59.7) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 176,936 (33.3) | 29,919 (35.2) | 147,017 (32.9) |

| Microvascular complications | |||

| Diabetic eye disease | 53,831 (10.1) | 9,106 (10.7) | 44,725 (10.0) |

| Blindness/low vision | 6,568 (1.2) | 1,426 (1.7) | 5,142 (1.2) |

| Nephropathy | 55,890 (10.5) | 10,080 (11.9) | 45,810 (10.2) |

| Dialysis | 4,149 (0.8) | 954 (1.1) | 3,195 (0.7) |

| Macrovascular complications | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | 157,966 (29.7) | 29,426 (34.6) | 128,540 (28.8) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 101,018 (19.0) | 20,090 (23.6) | 80,928 (18.1) |

| Angina | 45,809 (8.6) | 9,758 (11.5) | 36,051 (8.1) |

| Prior coronary revascularization | 38,256 (7.2) | 7,346 (8.6) | 30,910 (6.9) |

| Congestive heart failure | 61,350 (11.5) | 12,855 (15.1) | 48,495 (10.8) |

| Prior stroke | 39,580 (7.4) | 10,432 (12.3) | 29,148 (6.5) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 10,077 (1.9) | 2,348 (2.8) | 7,729 (1.7) |

| Prior cerebral revascularization | 6,122 (1.2) | 1,048 (1.2) | 5,074 (1.1) |

| Atherosclerosis, other | 4,839 (0.9) | 936 (1.1) | 3,903 (0.9) |

| Prior revascularization, other | 5,608 (1.1) | 1,162 (1.4) | 4,446 (1.0) |

| Foot-specific complications | |||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 53,707 (10.1) | 10,165 (12.0) | 43,542 (9.7) |

| Prior lower limb revascularization | 5,163 (1.0) | 984 (1.2) | 4,179 (0.9) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 16,737 (3.1) | 4,290 (5.0) | 12,447 (2.8) |

| Foot deformity | 10,742 (2.0) | 8,690 (1.9) | 2,052 (2.4) |

Numbers are n (%), unless otherwise indicated. Totals may vary slightly due to missing data.

In other analyses we examined the following: 1) whether the results differed if depression was defined using ICD-9-CM codes alone, 2) whether the risk of amputation differed between depressed patients with and without antidepressant treatment (defined as at least two antidepressant prescriptions dispensed within ninety days after the depression diagnosis), and 3) whether the results differed if veterans with depression, anxiety, or PTSD were compared to veterans with none of these three mental health disorders.

Results

We identified 624,968 veterans with diabetes in FY 2000. Veterans were excluded for prior lower limb amputations (25,660, 4.1%), bipolar disorder (24,660, 3.9%), schizophrenia (20,160, 3.2%), death prior to the index date (14,327, 2.3%), and no visits after the index date (22,549, 3.6%) (not mutually exclusive groups), leaving 531,973 eligible patients. Of these, 84,984 (16.0%) met our definition of depression, 63,615 (12.0%) by ICD-9-CM codes and 21,369 (4.0%) by antidepressant use. There were 10,194 veterans using antidepressants with diagnoses of anxiety or PTSD but not depression whom we considered non-depressed. Among 63,615 veterans with depression codes, the most common diagnoses were depressive disorder, not otherwise specified (43,242, 68.0%); major depressive disorder, recurrent episode (14,406, 22.6%); dysthymia (13,124, 20.6%); and major depressive disorder, single episode (10,430, 16.4%).

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the cohort by depression status are shown in Table 2. On average, the sample was elderly and mostly male. Compared to the non-depressed group, the depressed group was younger and had slightly more female, Caucasian, Native American, unmarried, homeless, and disabled veterans. The depressed group had more insulin use and diabetes complications, but HbA1c was equivalent between the groups (although there was a high proportion of missing data for this variable) (see Methods). The depressed group also had more hospitalizations, more outpatient visits, and higher medical and mental health comorbidity.

There were 3,830 incident lower limb amputations (1,289 major and 2,541 minor) over a mean of 4.1 years of follow up. The depressed group had 643 amputations (252 major and 391 minor), and the non-depressed group had 3,187 amputations (1,037 major and 2,150 minor). Table 3 shows unadjusted amputation incidence rates by depression status.

Table 3. Unadjusted incidence rates for non-traumatic lower limb amputation by depressed status.

| Per 1000 person-years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any amputation n=3830 |

Major amputation n=1289 |

Minor amputation n=2541 |

|

| Total | 1.91 | 0.64 | 1.27 |

| Depressed | 2.13 | 0.84 | 1.30 |

| Not depressed | 1.87 | 0.61 | 1.26 |

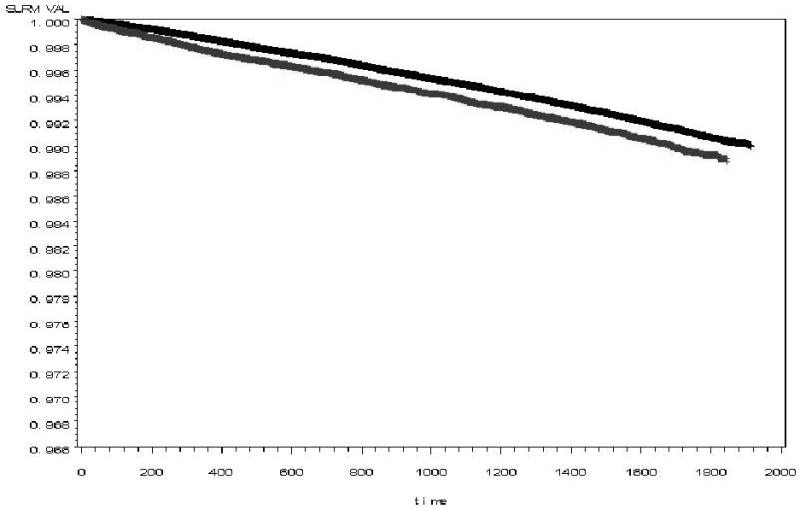

Table 4 shows the HR for lower limb amputations, comparing veterans with and without diagnosed depression. In unadjusted models, veterans with diabetes and diagnosed depression had a 15% higher risk of any lower limb amputation (HR 1.15, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.25) and a 38% higher risk of major amputation (HR 1.38, 95% CI: 1.21, 1.59), compared to those without diagnosed depression. This effect remained statistically significant after adjusting for all covariates (HR 1.12, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.22 for any amputation and HR 1.33, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.55 for major amputation). There were no significant multiplicative interactions between depression and age, gender, race/ethnicity, or PTSD. There was not an increased risk of minor amputations associated with diagnosed depression in any model. See Figure for Kaplan Meier curve for any amputation by depressed status.

Table 4. Cox regression models for non-traumatic lower limb amputation, comparing patients with diagnosed depression to patients without diagnosed depression.

| Models* | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any amputation | Major amputation | Minor amputation | |

| Model 1: Unadjusted | 1.15 (1.05, 1.25) | 1.38 (1.21, 1.59) | 1.03 (0.93, 1.15) |

| Model 2: Adjusted for demographics | 1.24 (1.14, 1.35) | 1.57 (1.36, 1.81) | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) |

| Model 3: Adjusted for demographics and utilization | 1.13 (1.03, 1.24) | 1.36 (1.17, 1.58) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) |

| Model 4: Fully adjusted | 1.12 (1.02, 1.22) | 1.33 (1.15, 1.55) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) |

Covariate groups were added to the model one at a time in the following order: demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, homelessness, and VA eligibility status); utilization (number of outpatient visits, number of outpatient mental health visits, and number of hospitalizations); insulin use; other medical conditions (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome); mental health conditions (posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and dementia); cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension and hyperlipidemia); microvascular complications (diabetic eye disease, blindness/low vision, nephropathy, and dialysis); macrovascular complications (ischemic heart disease, prior myocardial infarction, angina, prior coronary artery revascularization, congestive heart failure, prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, prior cerebral artery revascularization, other types of atherosclerosis except lower limb, and prior revascularization of other arteries except lower limb); and foot-specific complications (peripheral arterial disease, prior lower limb artery revascularization, peripheral neuropathy, and foot deformity). There were no substantial changes to the HR with the additions of the variable groups between Models 3 and 4.

Figure. Kaplan Meier curve for any amputation by depressed status (black=non-depressed, gray=depressed).

We performed several fully adjusted sensitivity analyses. The results were similar to the primary analysis if depression was defined only by codes (HR 1.10, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.22 for any amputation and HR 1.29, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.53 for major amputation). The primary analysis did not include HbA1c, but a complete case analysis including only patients with non-missing values for HbA1c gave similar results to the primary analysis (HR 1.20, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.38 for any amputation and HR 1.37, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.73 for major amputation). We also examined the potential effect of antidepressant treatment in the year following depression diagnosis, and there was also no substantial difference in major amputation risk associated with depression between treated patients (HR 1.11, 95% CI: 0.99, 1.24 for any amputation and HR 1.30, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.57 for major amputation) and untreated patients (HR 1.12, 95% CI: 0.97, 1.29 for any amputation and HR 1.40, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.74 for major amputation). The results were also similar when the risk of amputation was compared between veterans with depression, anxiety, or PTSD and veterans with none of these mental health disorders (HR 1.10, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.20 for any amputation and HR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.52 for major amputation).

Conclusions

We found that depression by ICD-9-CM codes or antidepressant prescriptions was associated with a 33% increased risk of incident non-traumatic major lower limb amputations but no increased risk of minor amputations. Our findings are consistent with another study in veterans with diabetes that found an association between decreased mental health functioning by SF-36 and the development of major but not minor amputations (Tseng, C. L. et al. 2007). There are several reasons depression could be associated with major but not minor amputations. Although there are regional variations in surgical practice (Wrobel, J. S. et al. 2001), minor amputations are generally reserved for less severe foot pathology. Patients with depression may present with more advanced foot complications that are felt to require major amputation (e.g., deeper foot ulcers, more extensive infection, or more severe arterial ischemia). Indeed, patients with major or minor depression present with larger and deeper foot ulcers than patients without depression (Ismail, K. et al. 2007). Patients with a depressive condition, compared to those without a depressive condition, also present more often with diabetic foot ulcers that penetrated into the joint or bone or were seriously infected (with an abscess or cellulitis) (Monami, M. et al. 2008).

Mediators of the relationship between depression and major amputations likely include key amputation risk factors like peripheral arterial disease, peripheral neuropathy, foot ulcers, and foot infection (Pecoraro, R. E. et al. 1990). In longitudinal studies of patients with and without diabetes, depression has been linked to the development of peripheral arterial disease (Wattanakit, K. et al. 2005), in addition to decreased patency and recurrent symptoms of arterial insufficiency after lower limb revascularization (Cherr, G. S. et al. 2007). Cross-sectional studies have shown that depression is associated with peripheral neuropathy (de Groot, M. et al. 2001; Vileikyte, L. et al. 2005). In elderly patients with diabetic foot ulcers, depressive symptoms were associated with a two-fold increased risk of a non-healing foot ulcer and five-fold increased risk of foot ulcer recurrence (Monami, M. et al. 2008). Other studies have shown that depressive symptoms are associated with impaired healing of acute mucosal wounds (Bosch, J. A. et al. 2007) and chronic venous and arterial leg ulcers (Cole-King, A. and Harding, K. G. 2001). Animal models suggest that chronic stress increases susceptibility to bacterial infections (Kiank, C. et al. 2007; Kiank, C. et al. 2008), including bacterial superinfection of cutaneous wounds (Rojas, I.-G. et al. 2002).

Poor self-care or adverse physiologic factors may be more proximal mediators of the relationship between diagnosed depression and incident major amputations. Self-care could be especially important in the setting of an active foot ulcer where adherence to offloading (Armstrong, D. G. et al. 2003) and attending wound care appointments are likely important for healing. Interestingly, although depression has been associated with several indicators of poor diabetes self-care like smoking, medication nonadherence, lower physical activity, unhealthy diet (Lin, E. H. et al. 2004), and missed primary care appointments (Ciechanowski, P. et al. 2006), a relationship between depression and foot-specific self-care has not been seen (Ismail, K. et al. 2007; Johnston, M. V. et al. 2006; Lin, E. H. et al. 2004).

Physiologic factors such as activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, autonomic dysfunction, systemic and localized inflammation, and hypercoagulability are thought to mediate the well-known relationship between depression and cardiovascular disease (Joynt, K. E. et al. 2003) and could explain the link between depression and major amputations. Peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease share risk factors with cardiovascular disease (D'Agostino, R. B., Sr. et al. 2008; Tesfaye, S. et al. 2005) and could be affected by these physiologic changes. Several of these physiologic factors could also be important in the relationship between depression and major amputations through impaired wound healing (Cole-King, A. and Harding, K. G. 2001) or promotion of the metabolic syndrome (Brunner, E. J. et al. 2002; Raikkonen, K. et al. 2007).

Similar to the relationship between depression and diabetes (Golden, S. H. et al. 2008), the relationship between depression and diabetic foot complications is likely bidirectional. It seems reasonable to assume that patients with diabetic foot ulcers are more likely to develop depression, although there have been no prospective studies of this association, and cross-sectional studies have had conflicting results (Carrington, A. L. et al. 1996; Vileikyte, L. et al. 2005; Willrich, A. et al. 2005). Symptoms of unsteadiness, pain, and reduced feeling in the feet have been associated with depression in a cross-sectional study of patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (Vileikyte, L. et al. 2005). We did not measure foot ulcers, because ICD-9-CM codes are quite unreliable for diabetic foot ulcer diagnosis (Reiber, G. E. et al. 2007). We attempted to control for possible confounding by pre-existing peripheral neuropathy, although ICD-9-CM codes are likely insensitive.

Whether screening for and treatment of depression in patients with diabetes could prevent amputations is unknown. Collaborative care approaches to treating depression in the setting of diabetes have been shown to improve depression and functional outcomes (Ell, K. et al. 2010) and save medical costs (Katon W. J. et al. 2008). A study to determine whether nurse-led case management of depression and diabetes care can improve diabetes outcomes is currently underway (Katon, W. et al. 2010), and its findings could be helpful in planning future evaluations of depression treatment for the prevention of amputations in persons with diabetes.

Our study has several strengths. We used a validated diabetes database that maximized the accuracy of the diabetes diagnosis. Having both VA and Medicare data greatly increased the sensitivity of our outcome measurement, since 40% more amputations are detected in dual-user veterans when VA data are supplemented with Medicare data (Tseng, C. L. et al. 2004). The large size of the study sample also provided adequate power to detect differences in the risk of amputation, a relatively rare event.

There are also limitations of our study. Although we studied amputation incidence following a diagnosis of depression, we could not fully establish that the amputations resulted from depression and not an unmeasured confounding factor. Our use of prescribed antidepressants in the definition of diagnosed depression could have led to some misclassification, since antidepressants are prescribed for other indications like neuropathic pain and anxiety, although the results were similar when the depression was defined by codes only. Depressed veterans could have been misclassified as not depressed if they did not receive a depression diagnosis or if they received a depression diagnosis before or after 2000, but such misclassification is likely to have attenuated the association we found. We were also not able to measure depression severity or change in depression status with time or treatment. There is some potential for bias from missing HbA1c values, although the results of our complete case analysis were similar to the primary analysis. There may be misclassification of covariates measured by ICD-9-CM codes. Unfortunately, we did not have information on smoking status but it is unlikely to have affected our results, as smoking was not an independent risk factor for amputations in many studies (Adler, A. I. et al. 1999; Reiber, G. E. et al. 1992; Selby, J. V. and Zhang, D. 1995). We did not include body mass index, physical activity, or medication adherence as potential confounders or mediators. We may have missed amputation cases if patients sought care outside of VA and Medicare coverage. Lastly, because our sample was nearly all male, these results may not be generalizable to women.

Summary

Diagnosed depression is associated with a 33% increased risk of incident non-traumatic major lower limb amputations in veterans with diabetes. Further study is needed to explore the directionality of this relationship, identify possible mediators, and determine whether screening for and treatment of depression would decrease amputation rates.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Qing Shao, Madhuri Palnati, and Sae Jong Byun for assistance with data analysis and Doug Smith, MD, for his thoughtful comments. This project was supported by a VA Epidemiology Merit Review Proposal (Dr. Miller). Dr. Williams was supported by F32AR-056380 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/American Skin Association and a Dermatology Foundation Dermatologist Investigator Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Disclosure. Dr. Miller has received grant funding from Sanofi Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck within the last three years. The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Parts of this study were presented at the 5th International Dermato-Epidemiology Association Congress in Nottingham, England, on 9/8/08, and at the 2009 Annual Health Services Research and Development National Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland, on 2/11/09.

An abstract from this study was published in Williams LH, Miller DR, Raugi GJ, Etzioni R, Maynard C, Reiber GE. Depression and incident lower limb amputation in veterans with diabetes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2008 128:2553. Abstract 24.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler AI, Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, Smith DG. Lower-extremity amputation in diabetes. The independent effects of peripheral vascular disease, sensory neuropathy, and foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1029–35. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, Davies MJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1165–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–78. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Kimbriel HR, Nixon BP, Boulton AJ. Activity patterns of patients with diabetic foot ulceration: Patients with active ulceration may not adhere to a standard pressure off-loading regimen. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2595–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older mexican americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2822–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch JA, Engeland CG, Cacioppo JT, Marucha PT. Depressive symptoms predict mucosal wound healing. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:597–605. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318148c682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner EJ, Hemingway H, Walker BR, Page M, Clarke P, Juneja M, Shipley MJ, Kumari M, Andrew R, Seckl JR, Papadopoulos A, Checkley S, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG. Adrenocortical, autonomic, and inflammatory causes of the metabolic syndrome: Nested case-control study. Circulation. 2002;106:2659–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038364.26310.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington AL, Mawdsley SK, Morley M, Kincey J, Boulton AJ. Psychological status of diabetic people with or without lower limb disability. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1996;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(96)01198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherr GS, Wang J, Zimmerman PM, Dosluoglu HH. Depression is associated with worse patency and recurrent leg symptoms after lower extremity revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:744–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, Simon G, Ludman E, Von Korff M, Young B, Lin E. Where is the patient? The association of psychosocial factors and missed primary care appointments in patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-King A, Harding KG. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:216–20. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. Association of depression and diabetes complications: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:619–30. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, Lee PJ, Kapetanovic S, Guterman J, Chou CP. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:706–13. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Wasylyshyn SM, El-Masri MM. Handling missing data in self-report measures. Res Nurs Health. 2005;28:488–95. doi: 10.1002/nur.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, Bertoni AG, Schreiner PJ, Roux AV, Lee HB, Lyketsos C. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. Jama. 2008;299:2751–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail K, Winkley K, Stahl D, Chalder T, Edmonds M. A cohort study of people with diabetes and their first foot ulcer: The role of depression on mortality. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1473–9. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston MV, Pogach L, Rajan M, Mitchinson A, Krein SL, Bonacker K, Reiber G. Personal and treatment factors associated with foot self-care among veterans with diabetes. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43:227–38. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.06.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joynt KE, Whellan DJ, O'Connor CM. Depression and cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms of interaction. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:248–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Fan MY, Unutzer J, Taylor J, Pincus H, Schoenbaum M. Depression and diabetes: A potentially lethal combination. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1571–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0731-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Lin EH, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, Young B, Rutter C, Oliver M, McGregor M. Integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: The design of the TEAMcare study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.03.009. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1155–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski P, Kinder L, Young B, Von Korff M. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2668–72. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiank C, Daeschlein G, Schuett C. Pneumonia as a long-term consequence of chronic psychological stress in balb/c mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiank C, Entleutner M, Furll B, Westerholt A, Heidecke CD, Schutt C. Stress-induced immune conditioning affects the course of experimental peritonitis. Shock. 2007;27:305–11. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239754.82711.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, Rutter C, Simon GE, Oliver M, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Bush T, Young B. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CF, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, Li YF, McDonell M, Fihn SD. Depression diagnosis and antidepressant treatment among depressed va primary care patients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:331–41. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki J, Sangeorzan B. The epidemiology of lower-extremity disease in veterans with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 2:B39–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the department of veterans affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 2:B10–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.suppl_2.b10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monami M, Longo R, Desideri CM, Masotti G, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. The diabetic person beyond a foot ulcer: Healing, recurrence, and depressive symptoms. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:130–6. doi: 10.7547/0980130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro RE, Reiber GE, Burgess EM. Pathways to diabetic limb amputation. Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:513–21. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikkonen K, Matthews KA, Kuller LH. Depressive symptoms and stressful life events predict metabolic syndrome among middle-aged women: A comparison of world health organization, adult treatment panel iii, and international diabetes foundation definitions. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:872–7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiber GE, Pecoraro RE, Koepsell TD. Risk factors for amputation in patients with diabetes mellitus. A case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:97–105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-2-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiber GE, Raugi GJ, Rowberg D. The process of implementing a rural va wound care program for diabetic foot ulcer patients. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas IG, Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Marucha PT. Stress-induced susceptibility to bacterial infection during cutaneous wound healing. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2002;16:74–84. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MS, Affouf M, Roy A. Six-year incidence of proteinuria in type 1 diabetic african americans. Diabetes Care. 2007a;30:1807–12. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MS, Roy A, Affouf M. Depression is a risk factor for poor glycemic control and retinopathy in african-americans with type 1 diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2007b;69:537–42. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180df84e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby JV, Zhang D. Risk factors for lower extremity amputation in persons with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:509–16. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye S, Chaturvedi N, Eaton SE, Ward JD, Manes C, Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Witte DR, Fuller JH. Vascular risk factors and diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:341–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CL, Sambamoorthi U, Helmer D, Tiwari A, Rosen AK, Rajan M, Pogach L. The association between mental health functioning and nontraumatic lower extremity amputations in veterans with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:537–46. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CL, Greenberg JD, Helmer D, Rajan M, Tiwari A, Miller D, Crystal S, Hawley G, Pogach L. Dual-system utilization affects regional variation in prevention quality indicators: The case of amputations among veterans with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:886–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein M, Taylor KK, Austin K, Kales HC, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use among depressed patients treated in mental health settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:654–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vileikyte L, Leventhal H, Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Ulbrecht JS, Garrow A, Waterman C, Cavanagh PR, Boulton AJ. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy and depressive symptoms: The association revisited. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2378–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattanakit K, Williams JE, Schreiner PJ, Hirsch AT, Folsom AR. Association of anger proneness, depression and low social support with peripheral arterial disease: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Vasc Med. 2005;10:199–206. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm622oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willrich A, Pinzur M, McNeil M, Juknelis D, Lavery L. Health related quality of life, cognitive function, and depression in diabetic patients with foot ulcer or amputation. A preliminary study. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:128–34. doi: 10.1177/107110070502600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkley K, Stahl D, Chalder T, Edmonds ME, Ismail K. Risk factors associated with adverse outcomes in a population-based prospective cohort study of people with their first diabetic foot ulcer. J Diabetes Complications. 2007;21:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel JS, Mayfield JA, Reiber GE. Geographic variation of lower-extremity major amputation in individuals with and without diabetes in the medicare population. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:860–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]